Abstract

Objectives: Traffic accidents cause severe social and economic impacts, demanding fast and reliable detection to minimize secondary collisions and improve emergency response. However, existing cloud-dependent detection systems often suffer from high latency and limited scalability, motivating the need for an edge-centric and consensus-free accident detection framework in IoV environments. Methods: This study presents a real-time accident detection framework tailored for Internet of Vehicles (IoV) environments. The proposed system forms an integrated IoV architecture combining on-vehicle inference, RSU-based validation, and asynchronous cloud reporting. The system integrates a lightweight ensemble of Vision Transformer (ViT) and EfficientNet models deployed on vehicle nodes to classify video frames. Accident alerts are generated only when both models agree (vehicle-level ensemble consensus), ensuring high precision. These alerts are transmitted to nearby Road Side Units (RSUs), which validate the events and broadcast safety messages without requiring inter-vehicle or inter-RSU consensus. Structured reports are also forwarded asynchronously to the cloud for long-term model retraining and risk analysis. Results: Evaluated on the CarCrash and CADP datasets, the framework achieves an F1-score of 0.96 with average decision latency below 60 ms, corresponding to an overall accuracy of 98.65% and demonstrating measurable improvement over single-model baselines. Conclusions: By combining on-vehicle inference, edge-based validation, and optional cloud integration, the proposed architecture offers both immediate responsiveness and adaptability, contrasting with traditional cloud-dependent approaches.

1. Introduction

Traffic accidents remain a major global challenge, causing approximately 1.19 million fatalities each year, alongside millions of injuries and significant economic losses [1]. Beyond their human toll, accidents disrupt mobility, worsen congestion, and place heavy demands on emergency response systems. Rapid accident detection and timely dissemination of alerts are therefore critical to improving survival rates and reducing secondary collisions [2]. Conventional approaches rely on manual reporting, operator surveillance, or cloud-based video analysis, all of which suffer from latency, scalability issues, and dependence on reliable backhaul connectivity [3,4]. In particular, cloud-centered systems are prone to bottlenecks that undermine real-time responsiveness, especially in regions with limited network infrastructure [4].

Recent advances in edge computing and intelligent transportation systems (ITS) have enabled decentralized accident detection, where vehicles perform onboard inference and Road Side Units (RSUs) act as edge processors to validate and broadcast alerts [5,6]. This architecture reduces reliance on cloud resources and lowers communication latency. However, previous studies have already demonstrated the feasibility of edge-based inference and V2X communication [5,6], yet few provide an integrated framework that combines vehicle-level detection, RSU-based dissemination, and cloud-supported retraining.

The Internet of Vehicles (IoV) establishes a distributed environment where vehicles, RSUs, and edge nodes continuously exchange sensing and perception information to enable real-time safety applications. Accident detection within this ecosystem must satisfy strict latency constraints, support lightweight on-vehicle inference, and ensure reliable validation before alerts are propagated to nearby vehicles. However, many existing systems still depend on centralized cloud processing or rely on single-model inference pipelines, which can introduce delays or instability under diverse environmental conditions. Therefore, the central problem addressed in this work is enabling real-time, high-precision accident detection directly on vehicles, while ensuring fast and trustworthy RSU confirmation without relying on inter-vehicle consensus.

Although substantial progress has been made in deep-learning-based accident detection, a clear research gap remains: current studies do not simultaneously integrate (1) a hybrid CNN–Transformer ensemble on vehicles, (2) a lightweight RSU confirmation mechanism that operates without inter-vehicle or inter-RSU consensus, reducing validation latency. (3) an asynchronous cloud reporting pipeline for long-term retraining and regional accident-risk modeling. Moreover, few existing approaches evaluate the feasibility of deploying such models under real IoV latency constraints. Addressing this gap forms the foundation of the proposed contribution. To fill this gap, we propose a three-stage accident detection framework that operates across the vehicle, RSU, and cloud layers. At the vehicle level, a lightweight ViT–EfficientNet ensemble classifies each incoming frame and triggers an alert only when both models agree. The nearest RSU then performs rapid validation and immediately broadcasts safety messages to nearby vehicles without requiring inter-vehicle or inter-RSU consensus. Finally, structured alerts are asynchronously sent to the cloud, enabling long-term model retraining and spatiotemporal accident-risk analysis. The framework minimizes cloud dependence and reduces communication overhead, providing a practical and scalable solution for safety-critical transportation environments.

Furthermore, to highlight the practical relevance of the proposed method, we now include a brief preview of the experimental results. The ViT–EfficientNet ensemble achieves an F1-score of 0.96 on both the CarCrash and CADP datasets, with an end-to-end decision latency below 60 ms, demonstrating its ability to meet strict real-time constraints in IoV environments. These results show that the framework is not only accurate but also computationally efficient for deployment on vehicle nodes and RSUs. This level of performance underscores the significance of the proposed design, enabling reliable accident detection and rapid alert dissemination without relying on cloud connectivity, making it highly suitable for real-world intelligent transportation systems. The contributions of this work can be summarized as follows:

- A hybrid ViT–EfficientNet ensemble for accurate vehicle-level accident detection.

- A consensus-free RSU validation mechanism that minimizes latency.

- A real-time edge-first architecture evaluated on the CADP and CarCrash datasets.

- An asynchronous cloud interface enabling model retraining and spatiotemporal risk forecasting.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows. Section 2 reviews the related work in traffic accident detection and real-time IoV systems. Section 3 introduces the proposed system architecture, detailing the vehicle-level detection strategy, RSU validation mechanism, and cloud integration. Section 4 presents the experimental setup, including dataset descriptions, training details, evaluation metrics, and both quantitative and qualitative results. Section 5 provides a detailed discussion of the findings, highlighting strengths, limitations, and comparisons with existing methods. Finally, Section 6 concludes the paper and outlines potential directions for future research.

2. Background

Traffic accident detection within the Internet of Vehicles (IoV) ecosystem draws on several foundational concepts in intelligent transportation systems, edge computing, and computer vision. This section introduces the core technical principles that underpin modern accident-detection frameworks.

2.1. Intelligent Transportation Systems and the Internet of Vehicles

Intelligent Transportation Systems (ITS) integrate sensing, communication, and computation technologies to improve road safety, mobility, and traffic efficiency. Within ITS, the Internet of Vehicles (IoV) extends these capabilities by enabling continuous information exchange between vehicles, Road Side Units (RSUs), and cloud services. IoV applications—such as collision warnings, cooperative perception, and automated decision-making—require extremely low latency and high reliability. These constraints motivate the use of distributed, edge-centric architectures where processing occurs near the data source rather than exclusively in the cloud.

2.2. Edge Computing in IoV

Edge computing places computational resources at or near RSUs and vehicles, reducing dependence on backhaul networks and enabling real-time decision-making. By processing sensor data at the network edge, IoV systems minimize communication delays and improve robustness in areas with limited connectivity. Typical edge-based safety pipelines include on-vehicle inference for rapid perception, RSU-assisted event validation for trustworthy dissemination, and cloud-supported analytics for long-term model refinement. This hierarchical arrangement forms the architectural foundation for modern IoV accident-detection systems.

2.3. Computer Vision for Accident Detection

Computer vision has become central to traffic accident detection due to its ability to extract semantic and spatiotemporal cues from video streams. Traditional pipelines relied on motion modeling, trajectory patterns, or handcrafted features; however, deep learning–based approaches now dominate, offering substantial gains in accuracy and robustness. Vision-based systems typically operate on dashcam, surveillance, or drone footage and must handle diverse environments, object scales, lighting conditions, and occlusions. These challenges motivate the use of high-capacity neural networks capable of learning discriminative representations from large video datasets.

2.4. Convolutional Neural Networks

Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) are widely used in accident detection because of their efficiency and effectiveness in extracting hierarchical spatial features. Their translation-invariant filters make them particularly suitable for road scenes, where camera perspectives and object positions vary dynamically. Architectures such as EfficientNet introduce compound scaling strategies that balance depth, width, and resolution to achieve strong accuracy under limited computational budgets—an important consideration for on-vehicle deployment.

2.5. Vision Transformers

Vision Transformers (ViTs) extend the Transformer framework to image analysis by dividing an image into fixed-size patches and modeling long-range context through self-attention mechanisms. Unlike CNNs, which rely on local receptive fields, ViTs explicitly capture global relationships between visual elements, enabling improved scene understanding and robustness to clutter. Although ViTs often require larger datasets for optimal performance, they offer powerful representational capacity for complex road environments, where accident cues may depend on holistic scene context.

2.6. Combining CNNs and Transformers

Hybrid architectures that fuse CNNs and Transformers have gained increasing attention in computer vision. CNN components effectively capture fine-grained spatial details, while Transformer layers model global dependencies and contextual interactions. This complementary behavior makes hybrid models suitable for tasks such as accident detection, where both local object features (e.g., vehicle damage, collision points) and broader scene dynamics (e.g., traffic flow, spatial layout) influence prediction. Hybrid CNN-Transformer designs, therefore, offer a promising foundation for real-time perception in IoV environments.

3. Related Work

3.1. Vision-Based Accident Detection

Recent advances in computer vision have enabled significant progress in real-time traffic accident detection. Ijjina et al. [3] proposed a Mask R-CNN-based framework combined with centroid tracking to detect accidents from surveillance videos by analyzing speed and trajectory anomalies, achieving robust performance under diverse conditions. Jiansheng [7] introduced a Gaussian Mixture Model (GMM)-based method with mean-shift tracking, capable of detecting collisions from motion changes in real-time. Ji et al. [8] developed a system for detecting truck-lifting accidents in container terminals using a modified YOLOv5 with keypoint tracking, achieving 100% recall with only 0.42% false alarms. Sai et al. [9] addressed data scarcity with a diffusion model-based augmentation technique (DMDAT), improving MobileNet accident detection accuracy by 3%. Qiu et al. [10] modified YOLOv5s with a CBAMC3 module and GELU activation, enhancing small-object detection in autonomous driving scenarios. Fang et al. [2] provided a comprehensive survey of vision-based accident detection and anticipation, highlighting challenges such as out-of-distribution accidents, long-tail event distributions, and real-time inference constraints. While these methods demonstrate strong results, they rely primarily on surveillance video and centralized processing, which limits their applicability to Internet of Vehicles (IoV) environments.

3.2. Transformer and Hybrid Architectures

Vision Transformers (ViTs) have been applied to traffic accident analysis, offering advantages in modeling long-range dependencies. Kang et al. [11] introduced a transformer-based approach for detecting critical pre-accident situations, achieving significant accuracy improvements on the Dashcam Accident Dataset (DAD). Dalwai et al. [12] proposed ViT-CD, a ViT-based framework for collision detection in CCTV traffic footage, effectively handling complex spatial and contextual conditions. Kang et al. [11] later refined transformer models for functional scenario classification in dashcam footage, improving interpretability. Saleh et al. [13] presented a contextual vision transformer for accident risk forecasting, integrating spatial and temporal features. Kumamoto et al. [14] developed an Accident Anticipation Transformer (AAT-DA) that incorporates driver attention, achieving strong results on dashcam datasets. Dilek and Dener [15] provided a broader overview of transformers for video anomaly detection, confirming their capability for rare crash events.

Despite these successes, ViTs are computationally expensive and data-hungry, often requiring large-scale training sets and resources [16]. Studies such as Koay et al. [17] show CNNs sometimes outperform ViTs when data is limited. To address these issues, hybrid CNN–Transformer models have been developed. Zhang and Sung [18] proposed a hybrid traffic accident classification model that integrated background subtraction, a CNN encoder, and a transformer decoder, achieving 96% accuracy on the CarCrash dataset. Hajri and Fradi [19] also demonstrated the benefits of CNN–Transformer fusion for dashboard camera accident detection, outperforming RNN-based baselines. These works confirm the promise of hybrids but focus largely on accuracy, with limited attention to deployment feasibility in latency-constrained IoV environments. Unlike these previous hybrid approaches, the proposed framework integrates the CNN–Transformer fusion into a complete multi-layer IoV architecture designed explicitly for real-time deployment. While earlier studies focus primarily on improving classification accuracy in offline environments, our system combines (1) a lightweight ViT–EfficientNet ensemble executed directly on vehicle nodes, (2) a consensus-free RSU-level validation mechanism that minimizes end-to-end latency, and (3) an asynchronous cloud reporting pipeline for long-term model retraining. This integration of hybrid deep learning with decentralized edge-first processing distinguishes the proposed method from prior CNN–Transformer fusion models and addresses key practical constraints of IoV environments.

3.3. Real-Time Systems and IoV Integration

Intelligent Transportation Systems research increasingly emphasizes edge-first architectures. Emara et al. [20] showed that Multi-Access Edge Computing (MEC) can reduce latency in V2X safety communications compared to cloud-based systems. Ke et al. [4] proposed a lightweight, edge-deployed near-crash detection system using dashcam feeds, reducing bandwidth and storage costs. BaniSalman et al. [5] developed VRDeepSafety, a VR-based simulation platform with V2X communication, achieving 85% accuracy at a 2 s horizon. Wei [21] introduced a spatio-temporal Conv-LSTM Autoencoder for large-scale IoV accident prediction, reaching AUROC = 0.94 in real deployments.

A unified framework that combines hybrid deep learning models, RSU-based validation, and cloud-supported retraining remains lacking. Addressing this gap is the focus of the proposed ViT–EfficientNet-based system.

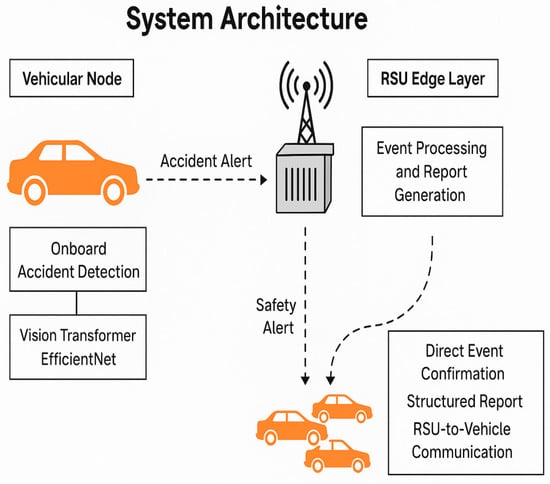

4. The Proposed ViT/EfficientNet-Based Accident Detection System

The architecture of the proposed accident detection system is designed to support real-time responsiveness, low latency, and decentralized edge-based decision-making. It follows a vehicle-to-edge (V2E) communication paradigm, where smart vehicles perform initial accident detection and Road Side Units (RSUs) validate and broadcast safety alerts locally. Structured reports are then asynchronously forwarded to the cloud for long-term learning and analytics. The system thus comprises three primary components—vehicular nodes, RSUs, and cloud integration—as illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

System architecture.

4.1. Vehicular Nodes: Onboard Accident Detection

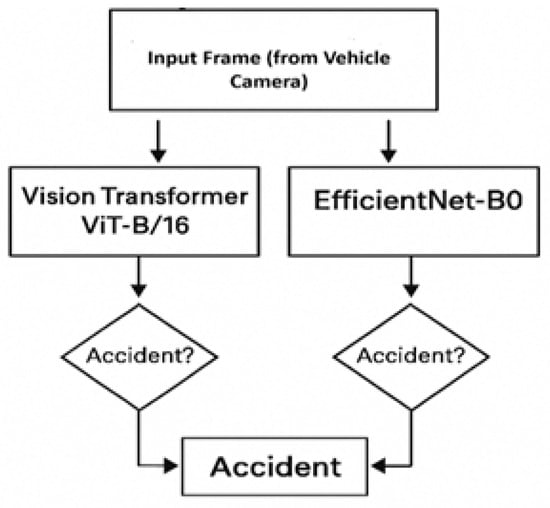

The vehicle nodes perform inference on each frame using two distinct classifiers: Vision Transformer (ViT-B/16) [3], and EfficientNet-B0. The selection of ViT-B/16 and EfficientNet-B0 is motivated by their complementary strengths in visual feature extraction under real-world driving conditions. ViT-B/16 offers strong global attention modeling, enabling it to capture long-range spatial dependencies that are critical for interpreting complex accident scenes. EfficientNet-B0, on the other hand, provides a highly efficient convolutional architecture with excellent accuracy-to-computation trade-offs, making it well-suited for deployment on resource-constrained vehicular hardware such as ARM-based edge processors. Although ViT-B/16 and EfficientNet-B0 provide a strong balance between accuracy and efficiency, lightweight transformer–CNN hybrids such as MobileNeXt, MobileViT, or EdgeFormer represent promising alternatives for future on-vehicle deployment under stricter latency or power constraints. By combining these models in a logical-AND ensemble, the system benefits from both contextual reasoning and fast, lightweight feature extraction, resulting in improved robustness and reduced false positives. To reduce false positives and improve robustness under varying conditions, a logical-AND ensemble strategy is employed. A frame is classified as an accident only if both models independently predict the ‘Accident’ class.

Let c_ViT and c_EffNet represent predicted classes from ViT and EfficientNet, respectively. A frame is labeled as an accident only if both models independently predict the ‘Accident’ class as defined in Equation (1):

The term consensus-free refers to the system’s decision logic that bypasses inter-vehicle or RSU-to-RSU coordination. Instead, a single high-confidence alert from an individual vehicle is considered sufficient to trigger validation and broadcasting by the RSU, thereby minimizing communication delays and simplifying the overall architecture.

The logical-AND ensemble rule issues an alert only when both classifiers agree. Although the logical-AND rule is simple, we explicitly present it through text, an equation, and a schematic to highlight its importance in reducing false positives and ensuring consistent ensemble behavior during deployment.

Figure 2 provides a simple schematic representation of the logical-AND ensemble used for vehicle-level accident detection.

Figure 2.

Logical-AND ensemble rule for accident detection.

This constitutes a vehicle-level ensemble consensus rule (ViT ∧ EfficientNet), which minimizes false positives and ensures robustness against model variance. While dual-model inference introduces a slight computational overhead, it provides more stable and precise decisions than threshold-based or single-model approaches.

Once an accident is detected, the vehicle generates an alert that includes: vehicle ID and timestamp, GPS location, model predictions and associated confidence scores, and a representative RGB frame or its compressed version (e.g., JPEG or low-bitrate video segment). This alert is immediately transmitted to the nearest RSU via V2I communication technologies such as DSRC or C-V2X [2]. By conducting accident detection locally, the system reduces reliance on network infrastructure, minimizes transmission latency, and enhances scalability across large vehicular fleets.

4.2. RSU Edge Layer: Alert Validation and Broadcasting

Each RSU maintains a buffer of incoming alerts and accepts a single vehicle-generated alert as sufficient for confirmation, thereby reducing response delay. Unlike consensus-based approaches, our framework adopts a consensus-free RSU design, where no inter-vehicle or inter-RSU agreement is required. This further minimizes latency. Once confirmed, the RSU generates a structured report that includes RSU ID, timestamp, GPS location, event label, vehicle-level evidence (e.g., image, predictions, confidence scores), and environmental context (such as weather, lighting, and traffic density). This report is locally cached and sent asynchronously to the cloud for storage and model retraining.

The RSU communication follows standard V2I protocols such as DSRC and C-V2X, ensuring reliable coverage within urban and highway environments [22]. In parallel, the RSU broadcasts a V2I safety message containing accident location, estimated severity, and timestamp, enabling nearby vehicles to reroute or slow down in order to prevent secondary collisions.

4.3. Cloud Interface: Asynchronous Reporting and Model Retraining

The cloud interface serves as the third component of the proposed system. Its role is not to participate in real-time decision-making, but to store structured RSU reports for long-term analysis. These reports support periodic model retraining, accident risk forecasting, and regional safety analytics. By decoupling cloud operations from real-time inference, the system ensures immediate responsiveness at the vehicle and RSU layers while maintaining adaptability through continuous cloud-based learning.

4.4. Security and Trust Considerations

The proposed architecture relies on vehicle-originated reports and RSU confirmation for rapid dissemination. To mitigate spoofing and replay attacks, we recommend standard V2X message authentication and certificate-based schemes (for example, IEEE 1609.2 style message signing and X.509-like certificates). Each vehicle alert should include a digital signature and a short-lived credential issued by a trusted authority; RSUs must verify signatures and check timestamps/nonces to prevent replay. Transport-layer encryption (e.g., TLS over cellular links or secure DSRC profiles) should be used for cloud-bound transfers. Finally, we note an important limitation: the present work does not implement or experimentally evaluate adversarial or Byzantine attack defenses (e.g., compromised vehicle nodes). We recommend future work to (1) integrate and evaluate certificate-based authentication in live deployments and (2) consider lightweight anomaly detection at RSUs to filter suspicious single-report patterns.

To strengthen the security discussion, we additionally analyze potential attack scenarios relevant to IoV environments. First, in the case of malicious or compromised vehicle nodes, the use of digital signatures and short-lived certificates restricts unauthorized entities from injecting fabricated alerts, while RSUs validate timestamps and nonces to prevent replay attempts. Second, tampered or partially corrupted alert packets are rejected unless both signature verification and basic metadata checks (position, time, event type) remain consistent with expected physical constraints. Third, although adversarial image perturbations may influence deep model predictions, hybrid or heterogeneous ensembles such as the ViT–EfficientNet combination tend to reduce adversarial transferability between backbones, offering moderate robustness improvements [23]. Nonetheless, the threat remains non-negligible. As an additional safeguard, we outline a lightweight RSU-side spatiotemporal consistency check that compares incoming alerts with recent observations (traffic flow, environmental context, or reports from nearby vehicles). Such cross-validation can help identify suspicious single-source alerts and mitigate both malicious-node attacks and adversarially perturbed image inputs [24].

5. Performance Evaluation and Results

This section presents the evaluation of the proposed accident detection framework using two benchmark datasets: CarCrash and CADP. The system is assessed for classification performance, latency, and deployment feasibility in edge-based IoV environments.

5.1. Dataset

The CarCrash dataset [25] (CCD) was preprocessed into 83,999 training frames (15,372 accidents, 68,627 no accidents) and 21,001 testing frames (3844 accidents, 17,157 no accidents), obtained by extracting annotated frames from crash and normal driving videos. The CADP dataset [26] was organized by parsing official annotations to locate accident onset times, labeling frames before the accident start as no accident and subsequent frames as accident. The resulting splits contained 22,256 training frames (13,448 accident, 8808 no accident) and 5564 testing frames (3294 accident, 2270 no accident). In both datasets, frames were resized to 224 × 224 pixels and converted to RGB tensors.

The CarCrash and CADP datasets do not include structured metadata such as vehicle speed, weather conditions, or traffic density, which limits the ability to perform condition-specific performance analysis. We identify this as a dataset-related limitation.

5.2. Implementation and Training Details

Two backbone architectures were employed in the proposed framework: Vision Transformer (ViT-B/16) and EfficientNet-B0. Both models were initialized with pretrained ImageNet-1K weights, and their classification heads were adapted to two output classes (Accident, No_Accident). Training was performed separately on the CarCrash and CADP datasets.

All frames were resized to 224 × 224 and normalized (mean = std = 0.5). To improve generalization, extensive data augmentation was applied during training, and these augmentation parameters—along with optimizer and scheduler settings—were refined through controlled experiments on the validation split. For ViT fine-tuning, additional random resized cropping was used. Validation and testing were performed with deterministic resizing and normalization only.

ViT-B/16: Training was conducted in two stages. The base training stage ran for 8 epochs with AdamW. A subsequent fine-tuning stage of 10 epochs was performed with a WeightedRandomSampler to mitigate class imbalance and a StepLR scheduler.

EfficientNet-B0: Models were trained for 5 epochs (CADP) and 8 epochs (CarCrash) using AdamW. A batch size of 16 was used for CADP and 32 for CarCrash.

Dataset splits were created using an 80/20 ratio with a fixed random seed (42) to ensure reproducibility.

The selection of hyperparameters was performed through iterative experimentation using the validation set. Learning rates were explored in the range of 1 × 10−4 to 5 × 10−5, with AdamW chosen due to its stability when fine-tuning transformer-based architectures. Weight decay values between 1 × 10−4 and 1 × 10−5 were tested to reduce overfitting. The final values reported in Table 1 correspond to the configuration that yielded the highest validation F1-score. Different epoch counts were adopted for the CarCrash and CADP datasets due to their differing levels of visual diversity and class balance: CarCrash required additional fine-tuning cycles, while CADP converged earlier. The use of WeightedRandomSampler was motivated by the class imbalance present in both datasets, ensuring that the Accident class was sufficiently represented during each training batch.

Table 1.

Hyperparameter settings for EfficientNet-B0 and ViT-B/16 models.

Table 1 summarizes the hyperparameter configurations used to train the EfficientNet-B0 and ViT-B/16 models on the Car-Crash and CADP datasets. For the Car-Crash dataset, ViT-B/16 is trained in a two-stage setup with 8 initial epochs followed by 10 fine-tuning epochs, while EfficientNet-B0 is trained for 8 epochs. Both models use the AdamW optimizer with a learning rate of 5 × 10−5 and weight decay of 1 × 10−4. For ViT-B/16, a StepLR scheduler (step = 3, γ = 0.5) is applied, whereas EfficientNet-B0 is trained without a scheduler. For the CADP dataset, ViT-B/16 is again trained for 8 epochs with the same optimizer and learning rate settings, while EfficientNet-B0 is trained for 5 epochs with a slightly higher learning rate of 1 × 10−4. Data augmentation strategies vary across models and datasets but generally include resizing, random flipping, rotation, color jitter, affine transformations, and grayscale conversion. These settings ensure consistent training conditions while allowing for dataset-specific adjustments.

5.3. Evaluation Metrics

The following metrics were used to evaluate performance: Accuracy (proportion of correctly classified frames), Precision and Recall for the Accident class, F1-Score, and Latency (time between vehicle-level detection and RSU-level report broadcast).

5.4. Quantitative Results

- (A)

- CarCrash Dataset:

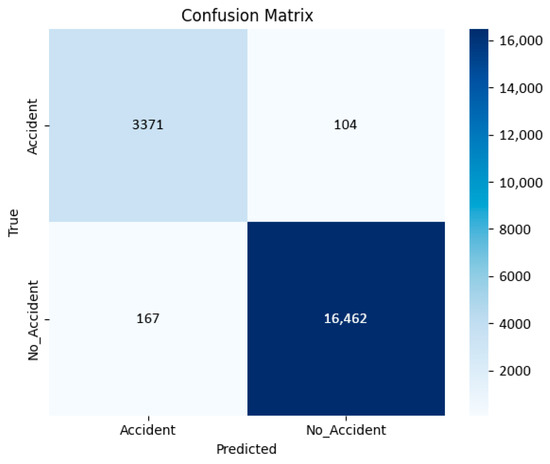

On the CarCrash dataset, the proposed ensemble achieved 98.65% accuracy, 0.96 F1-score, and an average latency of 53 ms. These results are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Performance of the proposed system on the CarCrash dataset.

The ensemble achieved strong intra-domain performance, as shown in the confusion matrix in Figure 3, where the dominance of diagonal entries indicates accurate classification of both accident and non-accident frames with limited misclassification.

Figure 3.

Confusion matrix of frame-level predictions on the CarCrash dataset. Values indicate the number of samples per class, with strong diagonal dominance indicating accurate classification.

Due to class imbalance in the CarCrash dataset, raw counts are reported to preserve the absolute distribution of predictions.

- (B)

- CADP Dataset:

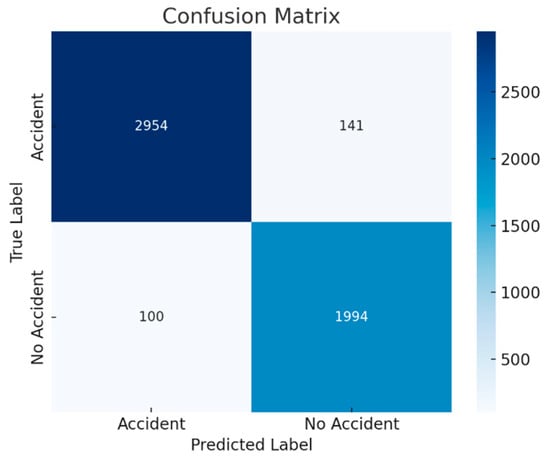

On the CADP dataset, the framework achieved 95.36% accuracy, 0.96 F1-score, and an average latency of 55 ms. These results are reported in Table 3.

Table 3.

System performance on the CADP dataset.

Performance remained robust when trained and tested on the CADP dataset, although a slight accuracy reduction compared to CarCrash suggests increased variability and limited dataset diversity. The confusion matrix in Figure 4 shows strong diagonal dominance, indicating accurate classification of both accident and non-accident frames, with relatively few false positives and false negatives.

Figure 4.

Confusion matrix of frame-level predictions on the CADP dataset. Values represent the number of samples per class. The dominant diagonal entries indicate reliable classification performance, while the off-diagonal entries correspond to limited misclassifications.

5.5. Ablation Study: ViT vs. EfficientNet vs. Ensemble

Table 4 reports an ablation comparison of ViT-only, EfficientNet-only, and the ensemble. EfficientNet outperforms ViT in both accuracy and latency, while the ensemble achieves the highest F1-score, validating the consensus strategy.

Table 4.

Comparison of ViT-only, EfficientNet-only, and ensemble models.

EfficientNet outperformed ViT in both accuracy and latency, while the ensemble achieved the highest F1-score, validating the consensus strategy. The ensemble improves the F1-score by reducing false positives through agreement-based filtering: both classifiers must independently detect an accident, which suppresses inconsistent or low-confidence predictions from individual models. Despite a slight latency overhead, the combined model offered the best trade-off for real-time deployment. The latency values reported in the ablation study correspond to the inference time of each individual model (ViT or EfficientNet) in isolation. In contrast, the ensemble latency includes sequential execution of both models, alert packaging, and RSU-side validation, which explains the higher end-to-end value of approximately 55 ms.

5.6. Edge Deployment Feasibility Analysis

To evaluate the practicality of running the proposed ViT–EfficientNet ensemble on in-vehicle embedded hardware, we provide a deployment feasibility assessment based on model complexity and published benchmarking results for representative platforms such as NVIDIA Jetson Nano and ARM Cortex-A72 systems (e.g., Raspberry Pi 4). This complements the latency measurements obtained on workstation hardware and clarifies the system’s expected operational behavior in real vehicular environments.

Model Computational Characteristics

The Vision Transformer ViT-B/16 contains approximately 86 million parameters and requires ~17.6 GFLOPs per 224 × 224 input, as reported in the original specification [27], EfficientNet-B0 contains 5.3 million parameters with ~0.39 GFLOPs [28]. These differences reflect the higher inference cost of transformer-based models and explain the latency disparity observed in Table 4.

Benchmarks on representative embedded platforms. Because the experiments in this work were performed on workstation hardware, we did not directly measure CPU/GPU utilization or power draw on embedded boards. To provide realistic deployment guidance, we summarize literature and vendor-reported benchmarks:

- NVIDIA Jetson Nano (embedded GPU). Empirical studies and benchmarking suites report that optimized CNNs comparable to EfficientNet-B0 achieve low single-frame inference times on Jetson Nano when using FP16/TensorRT conversions; measured per-frame latencies for lightweight CNNs are commonly in the single-digit to low-two-digit milliseconds range [29,30]. Transformer models are more compute-intensive; full ViT-B/16 is substantially heavier, but edge-oriented transformer variants and well-optimized runtimes can achieve real-time performance on GPU-equipped Jetson modules [29,30,31]. Official Jetson documentation and developer guidance also describe power modes and typical operating envelopes that make GPU-accelerated inference feasible within a ~5–10 W power budget, depending on configuration and nvpmodel settings [31].

- ARM Cortex-A72 (CPU-only; e.g., Raspberry Pi 4). Benchmark studies show that CPU-only platforms achieve reasonable inference times for small CNNs (e.g., EfficientNet-B0 scaled or MobileNet variants) typically in the tens of milliseconds per frame using optimized frameworks such as TensorFlow Lite or ONNX Runtime [29,32]. Transformer models without hardware acceleration incur substantially higher latency on CPU-only systems and often require model compression or replacement by lightweight variants for practical real-time use on such devices [29,32]. Official Raspberry Pi documentation provides power and thermal characteristics useful for deployment planning [33].

Projected ensemble behavior (conservative). If both backbones are executed sequentially on an embedded device, a conservative projection based on published latency ranges suggests: Jetson Nano (GPU)—ensemble latency on the order of tens of ms (e.g., roughly ~25–50 ms in well-optimized FP16 runtimes); ARM Cortex-A72 (CPU-only)—ensemble latency can reach tens to hundreds of ms depending on runtime and optimizations (e.g., ~75–150 ms). These are projections based on the cited benchmarks and vendor specs, not direct measurements from our system. See [29,30] for detailed per-model results and measurement methodology.

Optimization strategies. Standard methods to reduce memory, power and latency include FP16/INT8 quantization, pruning, knowledge distillation (e.g., training small student models), and selecting edge-oriented transformer variants (or replacing ViT-B/16 with smaller ViT variants or CNN alternatives). See [34,35] for canonical references on these techniques.

Scope and limitations. The embedded device numbers above are literature-derived and vendor-reported; we explicitly note that direct on-device profiling (CPU/GPU utilization, power draw, thermal behavior) is future work. We will perform and report those measurements in a hardware-focused extension to this manuscript.

5.7. Qualitative Observations

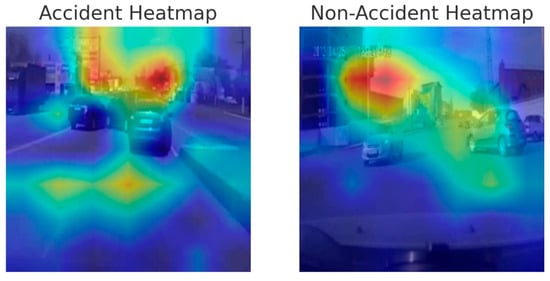

The system performed reliably across varied lighting and weather conditions, with no false positives observed when both ViT and EfficientNet produced high-confidence predictions. To support qualitative interpretability, Gradient-CAM visualizations were generated for the EfficientNet-B0 classifier. The activation maps were computed at the feature-map resolution of the network and resized to the input image resolution (224 × 224) using bilinear interpolation before overlaying on the original frames, ensuring correct spatial alignment.

Representative examples for accident and non-accident scenarios are shown in Figure 5. In accident frames, the model focuses strongly on collision regions and interacting vehicles, while in non-accident frames, the activation is more distributed across moving vehicles and lane geometry, with minimal emphasis on background areas. These observations indicate that the model relies on semantically meaningful spatial cues when producing its predictions. Following confirmation, RSUs broadcast V2I safety alerts within milliseconds.

Figure 5.

Gradient-CAM heatmaps generated from the EfficientNet-B0 classifier. Left: accident frame highlighting strong activation over the collision region. Right: non-accident frame showing distributed activation over vehicles and lane geometry.

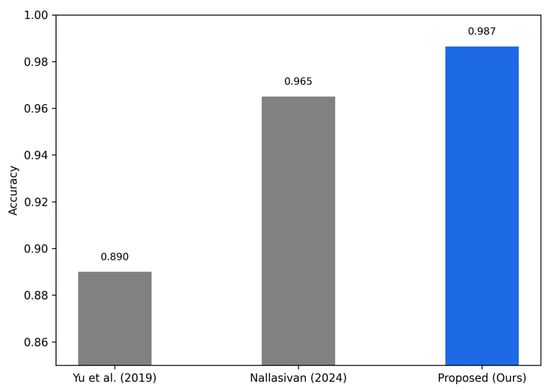

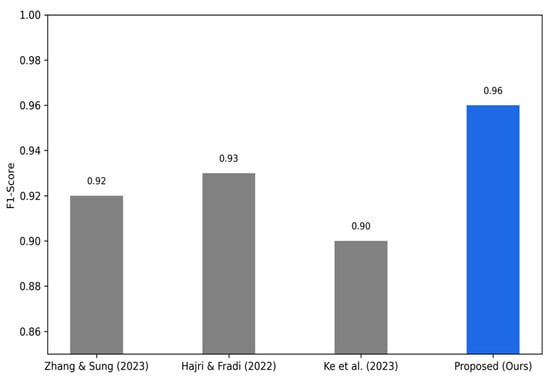

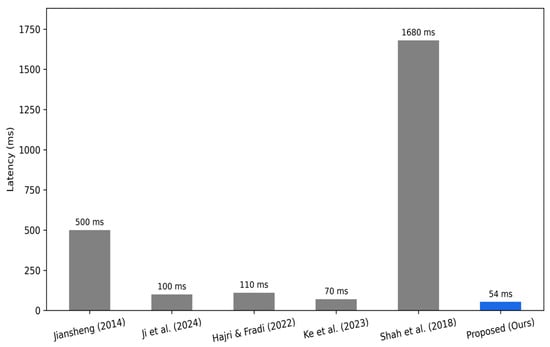

5.8. Comparative Evaluation with Existing Methods

Table 5 compares the proposed method with recent state-of-the-art techniques across accuracy, F1-score, latency/TTA, and edge deployability. As shown in the table, the proposed system achieves superior accuracy and F1-score while maintaining edge-level latency under 60 ms. Unlike many prior works, it eliminates consensus overhead by delegating confirmation to the RSU. Figure 5, Figure 6 and Figure 7 illustrate the comparative results in terms of accuracy, F1-score, and latency, respectively. Overall, these results confirm that the proposed framework delivers high-performance accident detection tailored for real-time vehicular networks. With strong accuracy, low latency, and a scalable edge-based design, it is well-suited for large-scale IoV deployments. Ensemble modeling and comparative results further validate its advantage over state-of-the-art baselines.

Figure 6.

Comparison of accuracy with state-of-the-art accident detection methods [36,37]. Only studies that explicitly report accuracy are included, due to heterogeneous evaluation protocols across the literature.

Figure 7.

Comparison of F1-score with recent accident-detection approaches [4,18,19]. The figure includes only methods that publish F1-score values, ensuring a transparent metric-specific comparison.

Table 5.

Comparison with state-of-the-art accident detection methods across accuracy, F1-score, latency, and edge deployability.

Table 5.

Comparison with state-of-the-art accident detection methods across accuracy, F1-score, latency, and edge deployability.

| Method (Year) | Model Type | Dataset(s) | Accuracy ↑ | F1-Score ↑ | Latency/TTA ↓ | Edge-Based |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ijjina et al. (2019) [3] | Mask R-CNN + Centroid Tracking | Surveillance Footage | – | – | – | No |

| Jiansheng (2014) [7] | GMM + Mean Shift | Traffic Videos | – | – | ~500 ms | No |

| Ji et al. (2024) [8] | YOLOv5 + Keypoint Tracker | Custom (Trucks) | – | 1.00 (Recall) | <100 ms | No |

| Sai et al. (2024) [9] | MobileNet + Diffusion Augmentation | Synthetic Accidents | ↑ 3% (vs. baseline) | – | – | No |

| Qiu et al. (2024) [10] | YOLOv5s + CBAMC3 Module | Self-driving Scenarios | – | – | – | Yes (Vehicle-Mounted) |

| Yu et al. (2019) [36] | Sparse Coding + WELM | CADP | ~89% (AP) | – | – | No |

| Xia et al. (2015) [38] | Matrix Approx. + Velocity Segmentation | CADP | – | – | – | No |

| Zhang & Sung (2023) [18] | CNN + Transformer | CarCrash | ~96% | ~0.92 | – | No |

| Hajri & Fradi (2022) [19] | CNN + ViT Hybrid | DAD, CCD | – | 0.93 | >100 ms | Partial |

| Ke et al. (2023) [4] | Lightweight CNN | Real-world Dashcams | – | ~0.90 | ~70 ms | Yes |

| Shah et al. (2018) [26] | Faster R-CNN + LSTM | CADP | – | AP ≈ 0.47 | TTA ≈ 1.68 s | No |

| Anjana& Nallasivan (2024) [37] | CNN + Trajectory Influence Maps | CADP | 96.5% | – | – | No |

| Proposed Method (ours) | ViT + EfficientNet + RSU (Edge-Based) | CADP, CarCrash | 98.65% | 0.96 | ~54 ms | Yes |

↑ indicates higher is better, ↓ indicates lower is better.

The comparative results presented in Table 5 are taken directly from the original publications, as most prior works do not release publicly available code or trained models. Therefore, these methods could not be retested under identical dataset splits or hardware conditions, and the comparison should be interpreted as a cross-study reference rather than a uniform benchmark.

Another challenge is the lack of standardized evaluation protocols in the accident detection literature. Different studies report different subsets of metrics (e.g., accuracy, recall, F1-score, latency) and use diverse datasets, train/test splits, and hardware setups. To ensure transparency, only metrics explicitly reported in each study were included, and Figure 5, Figure 6 and Figure 7 compare each metric using only the subset of works that provide that specific value. This prevents any misleading appearance of selective comparison.

Finally, we note that the field currently lacks a unified benchmarking standard. As future work, we propose the development of consistent comparative protocols—including shared datasets, common evaluation metrics, and uniform hardware settings—to enable more rigorous cross-method evaluation in IoV accident detection.

6. Discussion

The proposed accident detection framework demonstrates how combining onboard intelligence with edge-level validation can enable reliable and scalable deployment in intelligent transportation systems. By leveraging a ViT–EfficientNet ensemble at the vehicle layer, the system delivers high detection accuracy, while RSUs provide immediate validation and broadcasting without requiring inter-vehicle or inter-RSU consensus. This dual design—ensemble consensus at the vehicle layer and consensus-free operation at the RSU layer—balances robustness and latency, making the system both precise and responsive.

The consensus-free RSU mechanism is designed to minimize latency by avoiding inter-vehicle communication rounds; however, relying on a single vehicle alert may reduce robustness in the presence of noise or malicious behavior. Although our dual-model ensemble significantly reduces false positives at the vehicle layer, future enhancements will equip RSUs with a lightweight validation model or multi-source temporal consistency checks to further increase reliability without sacrificing responsiveness. Compared to cloud-dependent approaches, the edge-centric architecture ensures robust operation even in areas with degraded connectivity. Experimental results confirm that average decision latency remains below 60 ms, meeting strict real-time requirements. The present study does not perform cross-dataset evaluation; therefore, no claims regarding strong generalization can be made. Future work will train the model on one dataset and evaluate it on another to measure robustness to unseen environments and driving conditions. The asynchronous cloud layer extends system adaptability by enabling continuous model retraining and regional risk forecasting. This separation of real-time inference from long-term analytics allows the system to evolve over time while maintaining immediate responsiveness. Although ViT-B/16 and EfficientNet-B0 provide a strong balance between accuracy and computational efficiency, future research may explore lightweight transformer-integrated architectures such as MobileNeXt, MobileViT, or EdgeFormer. These models embed transformer blocks within highly optimized convolutional backbones and may offer additional latency reductions for real-time IoV deployment. Incorporating such lightweight hybrids could further enhance on-vehicle inference performance, particularly in low-power or high-traffic environments.

Despite the strong performance of the proposed framework, we emphasize that the lack of standardized benchmarks across the literature limits direct comparability. Future research should aim to establish unified evaluation protocols, enabling more rigorous end-to-end comparison of accident detection systems. Despite its strengths, certain limitations remain. Performance may degrade under low-light or adverse weather conditions, suggesting the value of sensor fusion (e.g., thermal cameras or LiDAR). Another important limitation of the current framework is its reliance on RGB vision alone. Although vision-based accident detection achieves strong performance under normal lighting conditions, its reliability may degrade in low-light scenarios, nighttime environments, adverse weather (fog, rain, snow), or when camera sensors are partially obstructed. Multimodal sensor fusion—combining visual information with LiDAR depth maps, radar reflections, or thermal infrared imaging—has been shown in prior ITS and IoV studies to significantly increase perception robustness in challenging environments. Integrating such modalities into the proposed architecture represents a promising direction for future work. In particular, RSUs or vehicles equipped with LiDAR or radar could provide complementary geometric cues that remain reliable when RGB quality deteriorates, while thermal imaging could enhance nighttime detection capabilities. Expanding the framework toward lightweight multimodal fusion would therefore strengthen real-world applicability and improve resilience across diverse environmental conditions. A further limitation of the proposed framework is its reliance on frame-level classification, where each image is analyzed independently without modeling temporal continuity. Although this design enables millisecond-level inference on resource-constrained vehicle hardware, it does not capture motion dynamics, trajectory evolution, or pre-crash cues that unfold across multiple frames. Incorporating lightweight temporal models—such as LSTMs, ConvLSTMs, 3D CNNs, or video transformers—could provide richer contextual understanding and improve robustness when single-frame cues are ambiguous. Extending the framework with temporal aggregation mechanisms represents an important direction for future work, particularly for earlier and more reliable accident anticipation. Additional limitations concern large-scale deployment, network variability, and uncertainty modeling. The current evaluation does not assess scalability across large fleets of vehicles or multiple concurrently active RSUs, and latency measurements were conducted under stable network conditions without simulating congestion, packet loss, or increased V2X traffic. Future work will include large-scale IoV simulations to quantify how end-to-end latency evolves under high message volumes or multi-RSU coordination. Furthermore, the robustness of the proposed framework to adverse environmental conditions—such as nighttime scenes, fog, rain, or low-visibility scenarios—has not yet been evaluated. Synthetic augmentation, weather-condition datasets, or multimodal sensing could be used to analyze performance under challenging conditions. Finally, the present system does not incorporate uncertainty quantification or calibration; integrating confidence-aware mechanisms (e.g., calibrated softmax scores, Monte Carlo dropout, or ensemble-based reliability estimation) would provide more reliable decision thresholds for safety-critical deployment. The RSU reports currently provide deterministic alerts; incorporating uncertainty estimates or anomaly flags could improve reliability. Future extensions may also include predictive models for early warning, enabling proactive interventions before collisions occur. Finally, ethical and security considerations are essential. Video-based processing raises privacy concerns, which can be mitigated through anonymization of faces and license plates. Encrypted V2I communication and redundancy checks are also necessary to guard against spoofed alerts or adversarial attacks.

In addition to these general considerations, we highlight specific security limitations related to malicious nodes and adversarial perturbations. Although digital signatures and anti-replay timestamps prevent unauthorized message injection, a compromised but still-valid vehicle node may issue forged accident reports. To address this risk, we propose lightweight RSU-side spatiotemporal consistency checks that compare incoming alerts with recent observations, enabling detection of anomalous single-source messages. Furthermore, adversarial image perturbations remain a potential vulnerability for onboard deep models. While heterogeneous ensembles such as ViT–EfficientNet tend to reduce adversarial transferability across backbones [23], their robustness is not absolute. This motivates the integration of adversarial-training strategies, perturbation detectors, or multi-modal sensing pipelines as future enhancements [24,39].

Beyond security considerations, an additional limitation concerns cross-city and cross-cultural generalization. Although the model performs strongly on the CarCrash and CADP datasets, these benchmarks primarily represent North American and East-Asian road conditions and do not fully capture global variability in driving behavior. Differences in traffic density, road design, signage conventions, driver aggressiveness, and pedestrian interaction may introduce domain shifts that affect real-world deployment. To address this, future work will include cross-dataset evaluation using more diverse benchmarks such as DADA-2000, DoTA, and A3D, along with domain-generalization techniques such as style augmentation, feature-level alignment, and semi-supervised self-training. These strategies will help improve robustness under unseen geographic, environmental, and cultural conditions. To provide clearer guidance for future research, each of these limitations suggests a concrete extension of the framework. First, the challenges posed by low-light and adverse-weather conditions motivate the integration of multimodal sensor fusion, where LiDAR, radar, or thermal imaging can complement RGB input to maintain reliable perception under visibility degradation. Second, the security limitations identified earlier highlight the need for empirical robustness evaluation, including authentication stress tests, detection of spoofed or replayed messages, and adversarial-robustness analysis for the ViT–EfficientNet ensemble. Third, the absence of proactive early warning mechanisms indicates an opportunity to incorporate temporal prediction models—such as LSTMs, ConvLSTMs, trajectory-forecasting networks, or video transformers—for accident anticipation before impact. Fourth, addressing scalability and network variability will require large-scale IoV simulations capable of modeling multi-RSU coordination, network congestion, and high message volumes. Together, these directions establish a structured research roadmap that transforms the limitations of the current study into actionable opportunities for advancing real-time safety systems in the Internet of Vehicles.

To clearly position our method relative to prior work, Table 5 provides a comparative analysis of recent accident detection approaches across model type, dataset usage, latency, and edge deployability. This comparison highlights the unique contribution of our system, which integrates hybrid deep learning, RSU-level validation, and cloud-assisted retraining in a unified IoV framework.

We acknowledge that accident detection studies differ considerably in datasets, evaluation metrics, and experimental settings. Because not all prior works report accuracy, F1-score, and latency simultaneously, Figure 6, Figure 7 and Figure 8 necessarily compare different subsets of studies based on the availability of each metric. This may give the impression of selective reporting; therefore, we have revised the figure captions and explanatory text to explicitly state that each metric comparison includes only the works that reported that specific measure. A unified benchmarking protocol remains an open challenge in this domain and represents an important direction for future work.

Figure 8.

Latency comparison between the proposed system and existing methods [4,7,8,19,26]. Because only a subset of prior works report latency or time-to-alert (TTA), the figure shows results only for studies providing these values.

7. Conclusions

This paper presented a real-time accident detection framework for intelligent transportation systems, combining on-vehicle deep learning inference with RSU-based validation and broadcasting. The proposed ensemble of Vision Transformer (ViT-B/16) and EfficientNet-B0 achieved an F1-score of 0.96 with decision latency below 60 ms on the CarCrash and CADP datasets, confirming its suitability for real-world edge deployment. Key innovations include an RSU validation strategy that avoids multi-node agreement, reducing system complexity and response time, and an asynchronous cloud layer that supports continuous model retraining and spatiotemporal risk forecasting. Together, these components enable both immediate responsiveness and long-term adaptability, addressing the limitations of cloud-dependent systems. Future work will focus on several concrete directions derived from our experimental findings. First, we observed reduced robustness in low-light, nighttime, and adverse-weather conditions; therefore, we plan to incorporate illumination-invariant feature learning, enhanced nighttime data augmentation, and exposure-normalization modules to mitigate these effects. Second, because accident dynamics often involve rapid temporal evolution, we will integrate temporal modeling components—such as transformer-based video encoders or motion-aware cross-frame attention—into the framework to improve early anticipation accuracy. Third, lightweight multimodal fusion will be explored using complementary sensing sources such as LiDAR, radar, or event cameras to maintain reliability when RGB quality is degraded. Finally, we will evaluate the system under cross-city and cross-cultural domain shifts and apply domain-adaptation strategies to improve generalization to unseen environments. Another promising direction is to extend the role of the RSU beyond cryptographic verification and forwarding. Future RSUs may host lightweight neural validation models—such as compact CNNs, MobileNet, or MobileViT variants—that perform secondary checks on incoming alerts. These models can exploit multi-vehicle consistency, verifying whether independent vehicles report compatible accident evidence within the same spatiotemporal window, thereby reducing false positives caused by sensor noise, corrupted packets, or malicious nodes. RSUs may also incorporate contextual features such as local traffic density or historical alert statistics. Exploring the trade-off between added computational load, validation latency, and robustness gains represents an important avenue for future research. Overall, the proposed framework offers a practical and scalable solution for real-time accident detection within connected vehicular networks.

Author Contributions

Z.S., L.G. and K.B. were involved in conceptualization, collection of data, writing the paper, and designing the figures. D.E.B., H.T.-C. and R.M.-P. supervised the content and structure of the paper and contributed to editing and revisions. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets analyzed in this study are publicly available. The CarCrash dataset is available at https://github.com/Cogito2012/CarCrashDataset (accessed on 10 November 2025), and the CADP dataset at: https://ankitshah009.github.io/accident_forecasting_traffic_camera (accessed on 10 November 2025).

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the support of the Autonomous University of the State of Quintana Roo (UQROO), Universidad Católica del Norte (UCN), and the Universidad Politécnica de Sinaloa (UPSIN) in this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| IoV | Internet of Vehicles |

| ITS | Intelligent Transportation Systems |

| RSU | Roadside Unit |

| V2I | Vehicle-to-Infrastructure |

| V2V | Vehicle-to-Vehicle |

| ViT | Vision Transformer |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

| TTA | Time-to-Accident |

| GPU | Graphics Processing Unit |

| ARM | Advanced RISC Machine |

| DSRC | Dedicated Short-Range Communications |

| C-V2X | Cellular Vehicle-to-Everything |

| RGB | Red Green Blue |

| AP | Average Precision |

| WELM | Weighted Extreme Learning Machine |

| GMM | Gaussian Mixture Model |

References

- World Health Organization. Global Status Report on Road Safety. 2023. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications (accessed on 16 September 2025).

- Fang, J.; Wu, Y.; Tian, Y.; Xiang, Y. Vision-Based Traffic Accident Detection and Anticipation: A Survey. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2023, 33, 1983–1999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ijjina, E.P.; Chand, D.; Gupta, S.; Goutham, K. Computer Vision-Based Accident Detection in Traffic Surveillance. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computing, Communication and Networking Technologies (ICCCNT), Kanpur, India, 6–8 July 2019; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, R.; Cui, Z.; Chen, Y.; Zhu, M.; Yang, H.; Zhuang, Y.; Wang, Y. Near-Crash Detection Using Vehicle-Mounted Dashcams on Edge Devices. IEEE Trans. Intell. Veh. 2023, 8, 2737–2747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BaniSalman, M.; Aljaidi, M.; Elgeberi, N.; Alsarhan, A.; Al Mamlook, R.E. VRDeepSafety: A Scalable VR-V2X Simulation Platform. World Electr. Veh. J. 2025, 16, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandeeswari, S.T.; Prasheeba, B.; Suguneswari, K. Real-Time Highway Accident Detection and Edge Caching. In Computing, Communication and Learning; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiansheng, F. Vision-based real-time traffic accident detection. In Proceedings of the 11th World Congress on Intelligent Control and Automation, Shenyang, China, 29 June–4 July 2014; pp. 1035–1038. [Google Scholar]

- Ji, Z.; Zhao, K.; Liu, Z.; Hu, H.; Sun, Z.; Lian, S. A novel vision-based truck-lifting accident detection method for truck-lifting prevention system in container terminals. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 42401–42410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sai, S.; Mittal, U.; Chamola, V. DMDAT: Diffusion model-based data augmentation technique for vision-based accident detection in vehicular networks. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2024, 74, 2241–2250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, C.; Tang, H.; Yang, Y.; Wan, X.; Xu, X.; Lin, S.; Lin, Z.; Meng, M.; Zha, C. Machine vision-based autonomous road hazard avoidance system for self-driving vehicles. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 12178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, M.; Lee, W.; Hwang, K.; Yoon, Y. Vision transformer for detecting critical situations and extracting functional scenarios for automated vehicle safety assessment. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalwai, F.S.; Kumar, G.S.; Sharief, Z.S.A.; Narayanan, S.J. ViT-CD: A vision transformer approach to vehicle collision detection. In Proceedings of the 2023 Global Conference on Information Technologies and Communications (GCITC), Bengaluru, India, 1–3 December 2023; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Saleh, K.; Grigorev, A.; Mihaita, A.S. Traffic accident risk forecasting using contextual vision transformers. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE 25th International Conference on Intelligent Transportation Systems (ITSC), Macau, China, 8–12 October 2022; pp. 2086–2092. [Google Scholar]

- Kumamoto, Y.; Ohtani, K.; Suzuki, D.; Yamataka, M.; Takeda, K. AAT-DA: Accident anticipation transformer with driver attention. In Proceedings of the Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision, Tucson, AZ, USA, 28 February–4 March 2025; pp. 1142–1151. [Google Scholar]

- Dilek, E.; Dener, M. An overview of transformers for video anomaly detection. Neural Comput. Appl. 2025, 37, 17825–17857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Z.; Liu, H.; Le, Q.V.; Tan, M. CoAtNet: Marrying convolution and attention for all data sizes. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2021, 34, 3965–3977. [Google Scholar]

- Koay, H.V.; Chuah, J.H.; Chow, C.O. Convolutional neural network or vision transformer? Benchmarking models for distracted driver detection. In Proceedings of the TENCON 2021 IEEE Region 10 Conference, Auckland, New Zealand, 7–10 December 2021; pp. 417–422. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Sung, Y. Hybrid traffic accident classification models. Mathematics 2023, 11, 1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajri, F.; Fradi, H. Vision transformers for road accident detection from dashboard cameras. In Proceedings of the 2022 18th IEEE International Conference on Advanced Video and Signal Based Surveillance (AVSS), Madrid, Spain, 29 November–2 December 2022; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Emara, M.; Filippou, M.C.; Sabella, D. MEC-assisted end-to-end latency evaluations for C-V2X communications. In Proceedings of the 2018 European Conference on Networks and Communications (EuCNC), Ljubljana, Slovenia, 18–21 June 2018; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, X. Enhancing road safety in Internet of Vehicles using deep learning for real-time accident prediction and prevention. Int. J. Intell. Netw. 2024, 5, 212–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ETSI. Intelligent Transport Systems (ITS); Access Layer Specification for Intelligent Transport Systems Operating in the 5 GHz Frequency Band; ETSI TS 102 724 V1.1.1; ETSI: Sophia Antipolis, France, 2012; Available online: https://www.etsi.org/deliver/etsi_ts/102700_102799/102724/01.01.01_60/ts_102724v010101p.pdf (accessed on 16 September 2025).

- Tramèr, N.; Kurakin, A.; Goodfellow, I.; Papernot, N.; Boneh, D.; McDaniel, P. Ensemble Adversarial Training: Attacks and Defenses. In Proceedings of the ICLR 2018 Conference, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 30 April–3 May 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Carlini, N.; Wagner, D. Towards Evaluating the Robustness of Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy, San Jose, CA, USA, 22–26 May 2017; pp. 39–57. [Google Scholar]

- Bao, W.; Yu, Q. Car Crash Dataset (CCD) for Traffic Accident Anticipation. GitHub Repository. 2020. Available online: https://github.com/Cogito2012/CarCrashDataset (accessed on 16 September 2025).

- Shah, A.; Lamare, J.B.; Anh, T.N.; Hauptmann, A. CADP: A Novel Dataset for CCTV Traffic Camera Based Accident Analysis. 2018. Available online: https://ankitshah009.github.io/accident_forecasting_traffic_camera (accessed on 16 September 2025).

- Dosovitskiy, A.; Beyer, L.; Kolesnikov, A.; Weissenborn, D.; Zhai, X.; Unterthiner, T.; Dehghani, M.; Minderer, M.; Heigold, G.; Gelly, S.; et al. An Image is Worth 16 × 16 Words: Transformers for Image Recognition at Scale. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2010.11929. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, M.; Le, Q. EfficientNet: Rethinking Model Scaling for Convolutional Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the 36th International Conference on Machine Learning, Long Beach, CA, USA, 9–15 June 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Baller, S.P.; Jindal, A.; Chadha, M.; Gerndt, M. DeepEdgeBench: Benchmarking Deep Neural Networks on Edge Devices. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2108.09457. [Google Scholar]

- Swaminathan, T.P.; Silver, C.; Akilan, T. Benchmarking Deep Learning Models on NVIDIA Jetson Nano for Real-Time Systems: An Empirical Investigation. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2406.17749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NVIDIA Developer Blog. Power Optimization with NVIDIA Jetson. (Developer NVIDIA Blog, 5 October 2023). Available online: https://developer.nvidia.com/blog/power-optimization-with-nvidia-jetson/ (accessed on 16 September 2025).

- Ameen, S.; Siriwardana, K.; Theodoridi, T. Optimizing Deep Learning Models for Raspberry Pi. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2304.13039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raspberry Pi Foundation. Raspberry Pi 4 Model B Product Brief/Datasheet. 2021. Available online: https://datasheets.raspberrypi.com/rpi4/raspberry-pi-4-product-brief.pdf (accessed on 16 September 2025).

- Jacob, B.; Kligys, S.; Chen, B.; Zhu, M.; Tang, M.; Howard, A.; Adam, H.; Kalenichenko, D. Quantization and Training of Neural Networks for Efficient Integer-Arithmetic-Only Inference. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–23 June 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Molchanov, P.; Mallya, A.; Tyree, S.; Frosio, I.; Kautz, J. Importance Estimation for Neural Network Pruning. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Long Beach, CA, USA, 15–20 June 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Y.; Xu, M.; Gu, J. Vision-based traffic accident detection using sparse spatio-temporal features and weighted extreme learning machine. IET Intell. Transp. Syst. 2019, 13, 1417–1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anjana, P.; Nallasivan, G. A Vision-Based Traffic Accident Analysis and Tracking System from Traffic Surveillance Video. In Proceedings of the 2024 Third International Conference on Intelligent Techniques in Control, Optimization and Signal Processing (INCOS); IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, S.; Xiong, J.; Liu, Y.; Li, G. Vision-based traffic accident detection using matrix approximation. In Proceedings of the 2015 10th Asian Control Conference (ASCC), Kota Kinabalu, Malaysia, 31 May–3 June 2015; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodfellow, I.; Shlens, J.; Szegedy, C. Explaining and Harnessing Adversarial Examples. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1412.6572. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.