Abstract

Climate-induced flooding is a major issue throughout the globe, resulting in damage to infrastructure, loss of life, and the economy. Therefore, there is an urgent need for sustainable flood risk management. This paper assesses the effectiveness of the hybrid defense system using advanced artificial intelligence (AI) techniques. A data series of energy dissipation (ΔE), flow conditions, roughness, and vegetation density was collected from literature and laboratory experiments. Out of the selected 136 data points, 80 points were collected from literature and 56 from a laboratory experiment. Advanced AI models like Random Forest (RF), Extreme Boosting Gradient (XGBoost) with Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO), Support Vector Regression (SVR) with PSO, and artificial neural network (ANN) with PSO were trained on the collected data series for predicting floodwater energy dissipation. The predictive capability of each model was evaluated through performance indicators, including the coefficient of determination (R2) and root mean square error (RMSE). Further, the relationship between input and output parameters was evaluated using a correlation heatmap, scatter pair plot, and HEC-contour maps. The results demonstrated the superior performance of the Random Forest (RF) model, with a high coefficient of determination (R2 = 0.96) and a low RMSE of 3.03 during training. This superiority was further supported by statistical analyses, where ANOVA and t-tests confirmed the significant performance differences among the models, and Taylor’s diagram showed closer agreement between RF predictions and observed energy dissipation. Further, scatter pair plot and HEC-contour maps also supported the result of SHAP analysis, demonstrating greater impact of the roughness condition followed by vegetation density in reducing floodwater energy dissipation under diverse flow conditions. The findings of this study concluded that RF has the capability of modeling flood risk management, indicating the role of AI models in combination with a hybrid defense system for enhanced flood risk management.

1. Introduction

Flooding is one of the most catastrophic natural hazards, resulting in extensive loss of land, human life, and infrastructure. On a global scale, annual flood events have an impact on millions of people, disrupting roads, damaging infrastructure, and leading to displacement [1,2]. Compared to other natural disasters, flood events happened 40% more frequently across the world. The major impact of the flood events on communities is as follows: (1) food shortage, (2) loss of life, (3) waterborne diseases, and (4) economic impacts for the very long term [3,4,5]. Flood occurrences have increased significantly due to rapid urbanization and climate change [1,5]. As a result of climate change, the developing world often observes catastrophic flood events [6]. For example, Pakistan ranked in the top 10 countries of the world affected by climate change; as a result, the country faced severe flooding in 2010 and 2022 [7,8]. A recent 2025 flood event in Pakistan demolished a village in the city of Buner province of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. However, the damages reported by the National Disaster Management Authority stated that in the 2022 flood, almost one-third of the country was affected by flood, which was about thirty-three million people [9,10]. This event alone caused almost forty billion US dollars in the form of damages. Besides this, the 2022 flood of Pakistan damaged agriculture, a larger area of farmland, standing crops, and houses [7,11]. These damages were caused by the overflow from the Indus River during the monsoon season, flooding across a larger part of the country. Therefore, with increasing intensity of the flood event, it is essential to develop a sustainable and effective flood risk management approach on an urgent basis [12,13].

For this purpose, researchers across the globe attempted to reduce the intensity of the flood events through a defense system [14,15]. However, a single defense system comprising either a dike/embankment, or moat, or vegetation cannot stand alone against the catastrophic flood event [16]. Therefore, a combination of these structural measures, like dikes and moats, along with nature-based solutions (vegetation), has been widely explored by researchers to understand their effectiveness in flood risk management [17,18]. The hybrid defense system proposed by the researchers has the capability of adaptation and sustainability [19,20]. For example, a combined effect of dike and vegetation has widely been investigated by researcher, and their results show greater resistance of such measures against flooding, hence providing resilience as well as absorbing floodwater [21,22]. A laboratory study revealed that the combined impact of dike and vegetation shows a significant result in flood risk management compared to the performance of only dike or vegetation [23]. The presence of vegetation at the downstream side of the dike results in lowering floodwater velocity and improving the performance of the dike [24]. Further, researchers investigated the combined impact of dike and moat on the reduction in hydraulic force generated by floodwater [25]. This approach was extended by the researcher, who combined dike, moat, and vegetation in a controlled laboratory setting and found that the hybrid defense system reduced floodwater energy up to 58% [17].

Moreover, an optimal arrangement of the hybrid defense system was tested in a controlled laboratory setting to assess its effectiveness in reducing various hydraulic forces behind the defense system [16]. A hybrid defense system reduced floodwater delay time by 55% as reported by [18]. The efficacy of the moat in a hybrid defense system was evaluated by investigating various hydrodynamic phenomena under varying flow conditions [26]. Previous research reported that a moat within a hybrid defense system acts as a water storage structure, reducing floodwater intensity and dissipating the energy of floodwater by hydraulic jump within a body of a moat [27,28]. Therefore, the integration of the soft (vegetation) and hard solutions (dike and moat) has the potential to provide a more resilient framework for effective flood risk management [29,30]. However, a precise prediction of flood risk management is essential through the utilization of advanced artificial intelligence techniques.

Previously, researchers have evaluated the performance of the advanced artificial intelligence (AI) models in predicting flood risk management [31,32,33]. However, the development of an AI-driven framework for flood protection most of the time depends on data series collected from hydrological stations, satellites, and sensors for a real-time assessment of flood prediction [34,35]. AI models have the capability of predicting various hydrodynamic phenomena and flow characteristics [36]. AI-driven evaluation of flood risk management provides a significant contribution to proposing an effective flood management approach.

However, a previous study utilized AI models on historical data points of flooding to understand the complex and nonlinear interaction of flow with flood resilience infrastructures [37]. Particularly, AI models like artificial neural network (ANN), Support Vector Regression (SVR), and Random Forest (RF) can capture the nonlinear interaction of flow with flood risk management elements [38]. These AI models assess how flood risk management elements impact flood behavior based on input parameters like rainfall intensity, land use changes, and soil conditions [39]. However, the accuracy and prediction capability of the ANN, SVR, and RF depend on the nature of the data series in predicting flood risk management [40]. Upon comparison to traditional approaches, researchers recommended that AI models can easily capture flood behavior and damage under diverse conditions [41]. The incorporation of AI models equipped flood risk management systems with higher flexibility, adaptability, and precision, enabling better flood forecasting and better preparedness.

A detailed comparison to prior studies has been conducted to present progress and application of artificial intelligence modeling in flood risk and management analysis. The literature reported in this study is recently published and is within the scope of the present study to highlight the novelty addressed. For instance, a study conducted by Chapi et al. [42] focused on the utilization of ensemble and tree-based modeling, like the Bagging-Logistic Model Tree framework for flood susceptibility mapping, demonstrating significant performance over traditional approaches. A subsequent study reported real-time flood forecasting and debris flow detection using the integration of computational intelligence and an early warning system [43]. Another study was conducted by the integration of deep learning frameworks such as Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) and attention-based approaches for the analysis of temporal dependencies in flood risk, indicating higher predictive capability and minimizing quantification of uncertainty [44]. A short-term flood forecasting and inundation mapping was studied by the utilization of a deep learning approach for handling nonlinear hydrodynamics phenomena and large datasets [45]. Furthermore, flood risk prediction was improved by the integration of a two-dimensional hidden-layer neural architecture for analyzing spatiotemporal features of hydrological phenomena, improving adaptability across lead times, decision support for mitigation, and enhancing model accuracy [46]. Besides AI models, a previous study also reported the importance of a SWAT-based approach for predicting the increasing risk of flooding under diverse climate conditions, linking land-use change, vegetation dynamics, and runoff extremes for adaptation planning supporting long-term policy [47].

Conventional neural networks and hybrid AI models were adopted for regional and climatic adaptability, specifically in urban and tropical environments [48,49,50]. A recently published study introduces LSTM with a Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) optimizer and other metaheuristic algorithms to enhance stability and robustness under diverse hydrological scenarios [51]. Moreover, the black-box nature of AI models and their explainable tools, such as SHAP analysis, enhances stakeholder confidence and interpretability in the assessment of flood susceptibility [52]. Although significant literature has reported on the effectiveness of AI models, numerous researchers have raised challenges in such modeling related to bias in datasets, transferability, and limited generalization across various regions [53,54,55]. Further reviews of the comprehensive literature on flood risk management highlight the need for adaptable, data-efficient, and interpretable AI-based modeling [54,55]. Notably, although most of the earlier studies have focused on the relationships between rainfall and runoff as well as flood inundation mapping and susceptibility analysis, few have examined the relationship between floodwater and physical mitigation infrastructure, especially hybrid systems involving gray and green mitigation measures [56]. This gap demonstrates the need for data-driven models that explicitly consider flow-structure interactions, thereby justifying the focus of the current study on AI-based modeling of hybrid defense systems to mitigate the flood risk.

Although previous studies have widely adopted gray (dike and moat) and green (vegetation) infrastructures for flood risk management. However, modeling a hybrid defense system through conventional or analytical techniques is difficult to understand the complex interaction between flow and these infrastructures. For this purpose, the current study utilizes advanced ensemble learning models to understand complex relationships between the parameters involved in this interaction from the data series and generalize them to new hydraulic conditions. The architecture to model the hybrid defense system with RF, SVR-PSO, XGBoost-PSO, and ANN-PSO allows realizing a more detailed view of the combined role of these systems in the flood mitigation process, as summarized in Table 1, which should be used to develop an effective and flexible flood-specific solution. Modeling is therefore required to (i) evaluate the magnitude of flow reduction and energy dissipation for different design configurations, (ii) explore non-linear interactions that cannot be isolated in laboratory tests alone, (iii) assess a large number of scenarios that would be impractical or too costly to test physically, and (iv) provide a framework that can be extended in future studies using field or regional hydrological data for flood-risk assessment. Table 2 summarizes the importance of modeling in addition to physical experiments.

Table 1.

Rationale for modeling moat, dike, and hybrid systems using AI techniques.

Table 2.

Need for modeling in addition to physical experiments.

Prior studies have not quantified a hybrid defense system comprising dike, moat, and vegetation using a data-driven framework; thus, the scientific novelty of this study lies beyond the comparative analysis of standard AI models tested. In contrast, the primary objective of this study is the development of data-driven models of a flood risk management defense system comprising multiple structural measures, such as dike, moat, and nature-based solution (vegetation). Although prior studies analyzed conventional laboratory-based analysis of the hybrid defense system, this study introduced a new paradigm of data-driven predictive models for understanding the complex interaction between flow and the hybrid defense system. The present study also uses the hyperparameter optimization method driven by PSO uniquely fitted to this hydraulic setup so that the models can be able to illustrate the intricate flow-structure relationships that cannot be understood through the existing trial and error techniques. The study also validated flow-structure interaction by developing a relationship between input and output parameters along with models’ interpretability (SHAP) analysis.

However, despite the significant contribution of the researchers in the field of flood risk management, there is still a gap in the previous research. While literature has extensively investigated the efficiency of the multiple structures for flood risk management under controlled laboratory settings. However, the long-term assessment of the hybrid defense system is still limited by the utilization of advanced AI models. The evaluation of the hybrid defense system by the integration of AI models remains underexplored. Addressing this gap is critical for developing a sustainable, adaptive, and comprehensive flood defense system that has the capability of withstanding climate-induced floods. Therefore, this research aims to explore the effectiveness of the hybrid defense system through an advanced AI model for predicting energy dissipation. The objectives of the current research paper are the following: (1) to evaluate the relationship between flow, roughness, vegetation conditions, and energy dissipation using correlation heatmap, scatter pair plot, and HEC-contour map, (2) to predict floodwater energy dissipation using advanced AI models for assessing the effectiveness of the hybrid defense system, (3) to evaluate the performance and predictive capability of the AI models using various performance indicators, and (4) to evaluate the performance of the AI models using statistical analysis such as ANOVA, t-test, Taylor’s diagram, and Violin plots.

The objectives of the present study closely align with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) defined by the United Nations, especially Sustainable Cities and Communities (SDG-11) and Climate Action (SDG-13). The research paper attempted to develop AI-based modeling of a hybrid defense system consisting of dikes, moats, and vegetation for sustainable and flood-resilient infrastructure. Additionally, the utilization of the nature-based solution (vegetation) promotes an ecosystem-based adaptation approach by targeting SDG-15 (life on land). The predictive capability of the AI-modeling evaluates the structural resilience of the hybrid defense system; however, the current research also helps in the development of the early warning system that should be incorporated in future research for communities and critical infrastructure safety.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Hybrid Defense System

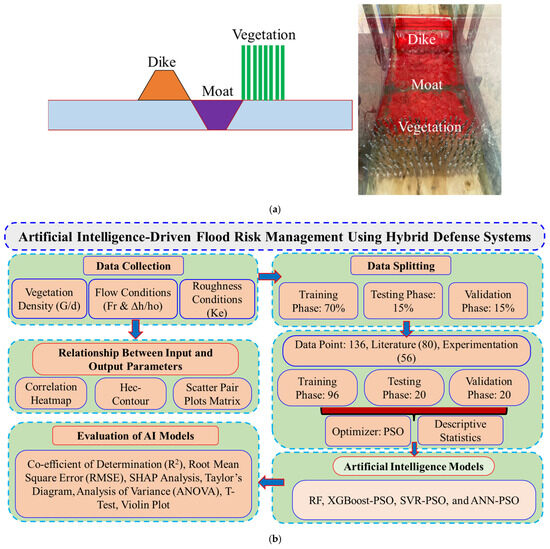

A hybrid defense system refers to a framework comprising two or more structural measures for flood risk management. The multiple structural measures integrated in the hybrid defense system include dike, moat, and vegetation, or a combination of these (Figure 1a). Table 3 summarizes the definition of the dike, moat, and vegetation, and their significance in this study. The main purpose of this framework is that a single structural measure may not effectively withstand catastrophic flood events, but the combined impact of these measures may reduce the synergy and intensity of flood events [16]. The main defense against rising water is dikes [57]; the main storage and diversion measures are moats, which slow down and spread flood waves [58], and lastly, vegetation, which resists floodwater, decreases velocity, and provides riverbank stabilization [59]. Dike–moat–vegetation or vegetation–moat–dike combinations also increase the resilience by energy dissipation, and risk spreading across layers, as well as reduced maintenance requirements versus stand-alone “gray” structures [16,17]. Such a solution has been receiving more and more attention as a viable solution to climate variability.

Figure 1.

Detail of hybrid defense system comprising dike, moat, and vegetation and data collection integrated in this study using different parameters, including energy dissipation, flow, vegetation, and roughness conditions (a) definition of hybrid defense system consisting dike, moat, and vegetation (b) flowchart of methodology adopted in this study depicting data collection, relationship between Fr, Ke, G/d, Δh/ho, and energy dissipation, data splitting, and evaluation of different models.

Table 3.

Definitions of the dike, moat, and vegetation, and their significance in this study.

There are multiple examples of hybrid defense in various countries. A similar situation with the experimental foreshore vegetation in front of dikes in the Netherlands under the Building with Nature program has been proven, which showed that marshes and willow belts help to diminish wave loads and enhance the security of the levees [60]. When combined with green belts and canals, the rehabilitation of old urban moats in China has notably increased the capacity to store and discharge floodwaters, especially those densely growing urban areas [61,62]. Routine Indus floods in Pakistan have an embankment with a combination of vegetated floodplain, which can only achieve a protective effect on the settlements in rural areas, in addition to aiding in agriculture [63]. These cases combined touch on the fact that hybrid defense systems are technically efficient and flexible in different geographies.

2.2. Laboratory Setup and Physical Modeling

The data points collected from the experimental setup align with the approach of the laboratory setting adopted in the literature. For conducting the experimental phase, all experiments were conducted in an open channel operating electronically with a length of 10 m, a width of 0.31 m, and a height of 0.5 m. The channel used in this research has a flowmeter and a flow speed controller at the inlet section. A flowmeter was used to measure flow velocity/discharge supplied, while a flow speed controller was used to control the inlet flow supply toward the body of the channel. The laboratory channel used in this study was divided into three different sections, including the inlet, testing, and outlet. The inlet section supplied flow discharge into the body of the channel for testing, and the outlet section was used to calculate energy dissipation through the hybrid defense system under different conditions. In the testing section, a hybrid defense system was placed at 4 m. The outlet section was used to supply water from the body of the channel to a storage tank installed at the end of the channel. The channel operated under a recirculation system, where water entered through the inlet section and exited through the outlet section. This cycle was repeated for analyzing the influence of the hybrid defense system on floodwater energy dissipation. A point gauge was used to measure the water surface profile in a channel to calculate energy dissipation under diverse flow conditions. The hybrid defense system comprising dike, moat, and vegetation was adopted from the scaling used by previous literature (used for data collection) and the real-world scenario of structural measures for flood risk management in Pakistan.

For physical modeling of the dike, moat, and vegetation, a concept of hydraulic similitude (geometric and Froude similarity) was used. For replicating the dike and moat in a controlled laboratory setting, an existing condition of embankment located on the Indus River was considered. The existing embankment located on the Indus River has a height range between 4 and 7 m, and a similar trend was adopted in previous studies [17]. For replicating the existing embankment of the Indus River in a laboratory setting, a scale of 1:100 was used. Therefore, considering the scaling criteria used, the dike model replicated in this study has a height of 6 cm (0.06 m), bottom width of 40 cm, and top width of 4.5 cm. In contrast, a moat represents an inverted shape of the dike; thus, a similar dimension was considered for replicating the physical model of the moat. Furthermore, for replicating the vegetation model in the laboratory setting, an Eucalyptus tree of diameter and height equal to 0.11–0.33 m and 7.6–14.6 m, respectively. The Eucalyptus tree was considered because of its greater water absorption capability. Prior studies reported three types of vegetation based on the density (G/d, where G: spacing between two consecutive vegetation cylinders and d: diameter of the vegetation cylinder), namely, dense, intermediate, and sparse vegetation [64]. However, in the real-world scenario, it is difficult to utilize dense or intermediate conditions; thus, prior studies recommended the utilization of sparse vegetation. Thus, considering these limitations, the experimental phase conducted in this study selected a sparse vegetation configuration with a vegetation cylinder of diameter = 0.003 m. Once a component of the hybrid defense system was selected, the flow condition was considered from the historical flood events reported in Pakistan. The data series of the flood event was obtained from the published report of the Federal Flood Commission (FFC) Pakistan by visiting their official website (https://ffc.gov.pk (accessed on 23 October 2025)). Prior studies and a report published by FFC reported that historical flood events have a Froude number ranging between 0.17 and 3.1. Therefore, in the experimental phase, a concept of the Froude similarity was used to select the values of the Froude number tested. In the present research, the condition selected in the experimental phase was conducted by considering the above limitations and those reported in the literature, from which data points have been collected.

For selecting roughness conditions of the dike and moat, in this study, bed roughness of the Indus River and those reported in the literature have been examined. A study conducted by Cornwell and Hamid-Ullah [65] reported that the Indus River has varying bed roughness conditions with boulder size ranging between 0.5 and 4.3 m, depending upon the width of the Indus River. Thus, for selecting bed roughness in a controlled laboratory setting, a scale of 1:100 was used to select the roughness condition of the dike and moat using the concept of geometric similarity. Based on the geometrical similarity, roughness conditions of 7.22, 14.32, and 24.47 mm were selected on the body of the dike and moat, and a similar approach was adopted in previous studies [66,67]. The roughness was induced on the body of the dike and moat using a layer of hot bitumen. This was performed to ensure capturing real scenarios of flow–structure interaction. Further, the roughness was induced at both ends (upstream and downstream) of the dike and moat to avoid the incident of the generation of a jet within the body of a moat.

In this study, the energy dissipation phenomenon was calculated through a hybrid defense system of varying roughness and flow conditions. For calculating the energy dissipation phenomenon, a total specific energy was calculated at the upstream and downstream ends of the hybrid defense system. A total specific energy was calculated using Equation (1).

where in Equation (1), E: total specific energy, z: elevation of the channel bed, h: water depth, V: flow velocity, g: acceleration due to gravity, and α: velocity coefficient. After calculating total specific energy on the upstream and downstream ends of the hybrid defense system, the following Equation (2) was used to calculate energy dissipation.

In Equation (2), E1: total specific energy on the upstream end, E2: total specific energy on the downstream end, and ΔE: energy dissipation of floodwater.

2.3. Data Collection

In this study, a data series was collected in two different phases, i.e., the literature and experimentation. In the first phase, a data series of flow regimes, roughness, and vegetation conditions was collected from the recently published work. There were 136 data points, including 80 that were gathered from the published work of Ahmed & Ghumman [17] and Murtaza et al. [18]. Within the data collected, the following parameters were considered: relative backwater rise (Δh/ho), Froude’s number (Fr), roughness conditions (Ke), and vegetation density (G/d) as active or input parameters, while energy dissipation (ΔE) was an output parameter. For backwater rise and Froude’s number, a data series of both subcritical and supercritical flow conditions was considered to develop a robust framework under diverse flood conditions. Similarly, for vegetation density, two different types of densities were considered, reported by the literature from which the data points have been collected. The two types of vegetation densities include sparse and intermediate vegetation, which have been tested in combination with the dike and moat. In the second phase, experiments were performed in a controlled laboratory setting using a hybrid defense system to calculate the energy dissipation of floodwater. The experiments were performed in accordance with the methodological constraints and parameter ranges reported in the previous literature used for data collection. The range of the Froude number was selected considering the limitation of the Froude number adopted by the previous studies [17,18] based on the real-world scenarios of Pakistan. Based on the flow, roughness, and vegetation conditions, a total of 56 experiments were performed in a controlled laboratory setting. By combining the data series of the published work and experiments performed, AI models were developed in this study. The reliability of the data series was tested by performing descriptive statistics (see Section 2.4). Once the data series was compiled from both phases, four different AI models were tested, namely RF, ANN-PSO, SVR-PSO, and XGBoost-PSO. For developing AI models, 136 data points were split into three different phases: training, testing, and validation. A data series of 70% was assigned for training, 15% for testing, and 15% for the validation phase of each model. Considering this data splitting, out of 136 data points, 95 points were assigned to training, 41 points to testing/validation phases of the model. However, the description of each model is explained in the subsequent section. Figure 1b depicts the flowchart of the methodology adopted in this study.

2.4. Descriptive Statistics

Previously published research was a source to acquire 136 data points where experiments were conducted for various input parameters like Fr, Ke, G/d, and Δh/ho, while (ΔE) was set as the output parameter. Statistics of each input and output parameter are reported to understand the reliability of the data series. The range of the Froude number demonstrates a moderate variation in flow regimes, with mean and standard deviation values of 1.01 and 0.49. In the case of vegetation density, a smaller value of standard deviation (0.377) and a mean value of 1.969 demonstrate a narrow distribution where most of the values are around 2.13. Further, in the case of relative backwater rise, the mean and standard deviation values of 1.61 and 1.00, respectively, indicate a wider distribution ranging from 0.13 to 3.26. The result of descriptive statistics shows a higher variability in the relative backwater rise. Similarly, the mean and standard deviation values of roughness condition were 4.74 and 8.13 (Table 4), demonstrating a higher difference in the defense system resistance conditions. In the case of energy dissipation, the mean value of 48.48 and the standard deviation of 15.02 indicate a clear difference in the energy dissipation of floodwater across diverse scenarios of flow regimes, vegetation conditions, and roughness data collected from literature and experimentation. However, the total range of energy dissipation was between 13.30 and 81.64 (Table 4). Energy dissipation of the floodwater falls between 36.48 and 59.25 in the case of quartile analysis, demonstrating the central tendency of the data series. The findings from the descriptive statistics provide a critical insight into the parametric analysis of input and output variables for investigating the effectiveness of the hybrid defense system in flood risk management.

Table 4.

Statistical description of input/output variables used in this research.

2.5. Artificial Intelligence Techniques

2.5.1. Artificial Neural Network (ANN) with Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO)

Artificial neural networks (ANNs) are an advanced architecture of AI working under a similar mechanism to the human brain, where signals are passed from the input to the output layer with the help of a hidden layer. However, the ANN model often faces the problem of overfitting, which needs to be addressed. Therefore, in the current research, the issue of overfitting was avoided by the utilization of an optimizer like PSO to model the nonlinear relation between flow, roughness, and vegetation conditions and energy dissipation of floodwater.

Previous research reported that ANNs work in a similar way to the human brain by simulating signals through input, hidden, and output layers [28,68]. The architecture of the ANN model developed in this study comprises two hidden layers with epochs and learning rate as summarized in Table 5. However, conventional ANN models find it difficult to provide a precise prediction of the hydrodynamics phenomenon. Therefore, to optimize the predictive capability of the conventional ANN model, PSO was employed in combination with the ANN model. PSO, inspired by the flocking behavior of birds, optimizes ANN weights and biases to minimize prediction error. PSO has been employed with 10 particles, 10 iterations, and parameters were c1 = 0.5, c2 = 0.3, and inertia weight w = 0.9. After identifying the best solution, the final ANN was trained on Adam as the optimizer and as well as the mean squared error. Using PSO, the ANN was provided with the advantage of both robustness and adaptability and has proven to be useful in modeling nonlinear and complex relationships within hydrodynamic processes. Furthermore, PSO is considered a population-based global optimizer that helps in reducing local minima and is greatly recommended for the optimization of ANN, SVR, and other AI models under nonlinear hydraulic applications, as studied by [69,70]. In the present research paper, the architecture of the ANN model was fixed before the training phase, and PSO was utilized for hyperparameter optimization, including weight initialization seeds, learning rate, and other parameters. Therefore, in this study, PSO was used to improve the convergence of the model and stabilize the predictive capability of the ANN model. Therefore, these advantages of the PSO in comparison to the Adam optimizer, in this study, PSO-based optimization was utilized to enhance the predictive capability of the tested model for different scenarios of flood risk management. Moreover, the complex and nonlinear hydraulic interaction without an issue of overfitting, prior studies reported that the ANN model with more than one hidden layer provides robust results under medium data points [71,72]. In this study, a two-hidden-layer ANN model was selected to understand the complex hydraulic phenomenon and the balance between model generalization.

Table 5.

Model configurations and PSO-tuned hyperparameters used in this study.

2.5.2. Support Vector Regression (SVR) with PSO

Support Vector Regression (SVR) is a machine learning-based regression algorithm utilized for performing a task that allows error margins up to certain limits by best fitting the data series. However, a standard SVR model struggles in prediction through a large data series of high complexity and noise. This model also needs careful consideration of parameter tuning and may be expensive in computation to train a large data series. Therefore, in this study, a hybrid SVR-PSO model was developed by mapping a relationship between input and output parameters as summarized in Table 5. For this purpose, to develop an SVR model with a radial basis function (RBF) kernel was utilized because of its significance in capturing the complex dependency of the output variable on input variables. The optimization of key hyperparameters such as the regularization parameter (C), epsilon (epsilon), and the kernel coefficient (gamma) was achieved using PSO. C between 0.1 and 1000, epsilon between 0.01 and 0.1, and gamma between 0.01 and 1 were defined as the search space. A potential set of parameters was encoded into each particle, and its fitness was measured by training the SVR model on the training set and computing the test MSE. The swarm size was 10 particles, and its iterations were 10, c1 = 0.5, c2 = 0.3, and w = 0.9 in balancing exploration and exploitation. Upon receiving optimal parameters, the final SVR model was trained and tested in groundwork on train, test, and validation partitions. The model performance was evaluated in terms of R2 and MSE.

2.5.3. Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost) with PSO

The XGBoost model often faces the issue of nonlinear and inefficient hyperparameters tuning, which need to be addressed. Therefore, this paper utilized a PSO optimizer in combination with an XGBoost model to obtain the advantage of an ensemble learning algorithm in the prediction of energy dissipation. XGBoost uses sequential trees, and hence it reduces both bias and variance. Three important hyperparameters, including the maximum depth of the tree, the learning rate, and the number of estimators, were tuned through PSO. The specified ranges were max_depth [2, 10], learning_rate [0.01, 0.3], and n_estimators [50, 300]. The PSO particles were configured, and fitness would be calculated as test MSE. In the swarm optimization, 10 particles and 10 iterations were utilized, considering the parameters c1 = 0.5, c2 = 0.3, and w = 0.9. Optimal hyperparameters were then considered to train the final XGBoost model, and the performance of the model was tested on training, testing, and validation sets in terms of R2 and MSE. The nature of regularization, subsampling, and shrinkage allowed XGBoost to be robust to overfitting, whereas the determination of hyperparameter values was automated and efficiently performed by PSO. This hybrid technique was used to search systematically through parameter space, in contrast to a complex trial-and-error grid search. Consequently, XGBoost-PSO could offer effective predictive performance and explainability, which makes it an efficient solution in constructing nonlinear hydrodynamic relations and one of the best methodologies conducted in this study.

2.5.4. Random Forest (RF)

An ensemble-based model, Random Forest (RF), was used to display the model as a baseline to compare with the models optimized using the PSO algorithm. RF constructs numerous decision trees based on bootstrap samples of the training data and uses ensemble averaging to reduce overfitting and variance as compared with a single decision tree. In this research paper, RandomForestRegressor used 200 estimators (trees), and other parameters were set by default. The training was performed on 70 percent of the data, with 15 percent used to test the model and another 15 percent used to validate the model. The prediction results on every split of the whole dataset were compared, and the measures of the results were performance using R2 and mean squared error (MSE). RF produced consistent predictions because ensemble averaging overcame the impact of noise and data variability. RF has shown an adequate baseline performance with relatively low computational cost and quick training durations, although it was not tuned by applying the metaheuristic optimization tool, such as PSO-driven models. It had the primary drawback of low flexibility in terms of capturing highly complex nonlinearities as compared to SVR-PSO, ANN-PSO, and XGBoost-PSO. Nevertheless, RF has provided a competent benchmark model that is interpretable, efficient, and has predictive power compared to PSO-based optimization models.

2.6. Optimization and Step-by-Step Procedure of AI Models

For enhancing predictive capability and reducing hyperparameter tuning, in this study, Particle Swarm Optimization was used to optimize different AI models (ANN, SVR, and XGBoost) tested in the study. For the optimization of the ANN, SVR, and XGBoost models, the PSO-based optimizer used is as follows: particles = 10, number iterations = 10, c1 = 0.5, c2 = 0.3, and w = 0.9. However, the optimization approach used in this study for each model has the following step-by-step procedure.

ANN-PSO

- Initialize PSO swarms where each particle encodes ANN hyperparameters and/or initial weight seeds.

- For each particle, construct an ANN with the particle’s hyperparameters and initialize weights accordingly.

- Train the ANN on the training subset using the Adam optimizer and compute validation loss (MSE).

- Update each particle’s personal best and the global best according to validation of MSE.

- Update particle velocities and positions using PSO update rules (c1, c2, and w).

- Repeat for the specified number of iterations and select the ANN corresponding to the global best particle.

- Retrain the selected ANN on combined training + validation and evaluate the test set.

SVR-PSO

- Encode SVR hyperparameters (C, ε, γ, or kernel choices) into PSO particles.

- For each particle, train SVR (RBF kernel) on the training set and compute the validation of MSE.

- Update personal/global bests and particle velocities/positions using PSO.

- After convergence, select the best hyperparameter set and retrain SVR on combined training + validation; evaluate on test set.

XGBoost-PSO

- Encode XGBoost hyperparameters (learning_rate, max_depth, n_estimators, subsample, colsample_bytree) into particles.

- For each particle, train XGBoost and record the validation of MSE.

- Update PSO bests and particle states; iterate until termination.

- Select the best hyperparameters from the global best, retrain the final model on combined training + validation, and evaluate.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Correlation Heatmap

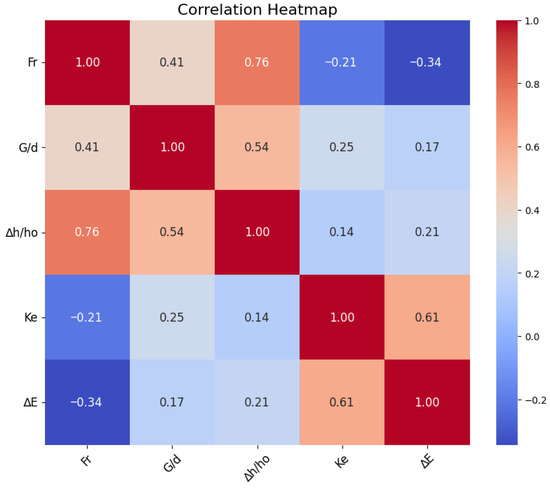

In the context of flood risk management, a correlation heatmap is an effective framework because of its capability to show the relationship between different input parameters contributing to floodwater energy dissipation. This map helps in allowing a precise prediction of flood risk by knowing the strong correlation of key parameters influencing flood events. Thus, a systematic framework for flood risk management can be proposed concerning key drivers. Figure 2 depicts the result of a correlation heatmap plotted to understand the response of the output variable with the input variables utilized in this study. The map plotted in this paper shows different colors, which indicate the relationship of each input parameter with floodwater energy dissipation. In this section, the relationship of each input parameter with floodwater energy dissipation is separately explained. Out of the tested input parameters, roughness conditions (Ke) indicate a strong positive correlation with energy dissipation of floodwater, with an R-value of 0.61. The findings indicate a significant contribution of the roughness conditions in mitigating flood risk by reducing the energy carried by the floodwater. As a result of greater roughness conditions, turbulence generated is intensified by improving floodwater energy dissipation and attenuation, aligning with the findings of [73,74,75]. The roughness conditions of the defense system indicate greater frictional resistance of structural and natural barriers to the flowing water, demonstrating its effectiveness in flood risk management.

Figure 2.

Visual direction and strength of relationship between input (Fr: Froude number, G/d: vegetation density, Ke: roughness, and Δh/ho: relative backwater rise) and output (ΔE: energy dissipation) parameters using correlation heatmap.

The vegetation density (G/d) is positively related to floodwater energy dissipation with an R-value of 0.17. Although the correlation is moderate, there is an indication that vegetation provides some contribution towards localized flow resistance and the generation of turbulence, which contributes to an increase in energy loss to some extent. Similarly, [76] reported close observations showing that vegetation-induced drag contributes to energy dissipation of flows, especially at moderate density conditions. However, in this paper, a data series of vegetation density collected from the literature and experimentation mainly comprises sparse and intermediate vegetation, which provides smaller resistance to the flow compared to dense vegetation. There is also a very weak positive relation between the relative backwater rise (Δh/ho) and ΔE (an R = 0.21). It implies that backwater effects are a measure of hydraulic adaptations in the channel, not considered to contribute significantly to energy dissipation. In addition, roughness and vegetation, Δh/ho could increase losses in energy, as Iqbal et al. [77] emphasized the interactive effect of variations in flow depth and drag induced by vegetation. Interestingly, Fr shows a negative correlation with ΔE (R = −0.34), which states that greater intensities of flows can decrease the performance of energy dissipation. This may be explained by the flow bypass phenomena and the corresponding smaller influence of roughness factors under high-velocity conditions. Therefore, it is necessary to optimize the flood defense system considering the contribution of the input parameters utilized in this study.

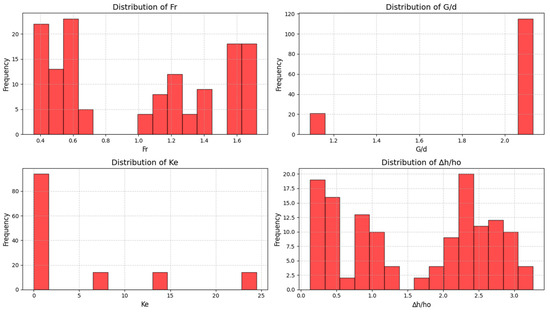

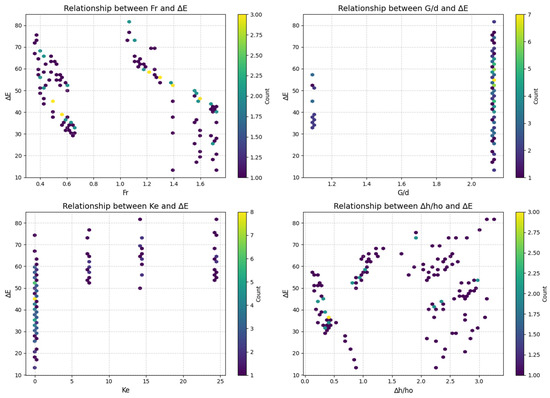

3.2. Direct and Indirect Relationship Between Parameters

The distribution of direct and indirect relationships of input variables, including Fr, G/d, Δh/ho, and Ke, with the floodwater energy dissipation is depicted in Figure 3. The study uses the distribution histogram to analyze the influence of specific input parameters on floodwater energy dissipation, and therefore does not account for directional interactions between these parameters. In this context, the direct effect refers to the influence of a single parameter, while the indirect effect describes the combined influence of multiple parameters. A histogram of the findings is presented in Figure 3 to understand the associations between input and output parameters, concerning frequency, representing the impact on floodwater energy dissipation. The Froude number distribution visualized in Figure 3 depicts two different trends: a greater value of frequency was observed in the range of Fr = 0.4 to 0.6. At higher Fr values (1.4 to 1.6), indicating flow regimes ranged from subcritical to supercritical flow conditions, the effectiveness of the hybrid defense system in dissipating floodwater energy was reduced. Such a bimodal distribution indicates the variability of flow regimes reflected in the dataset. Regarding vegetation density, in this study, two types of densities (sparse and intermediate) were selected to assess their influence on the energy dissipation of floodwater.

Figure 3.

Distribution histograms of the direct and indirect influence of inputs (Fr, G/d, Ke, and Δh/ho) on outputs (ΔE) parameters collected from the literature review and experimental setting for different AI models.

The result demonstrates that in the case of sparse vegetation, a limited drag and wake turbulence is generated, resulting in lower energy dissipation of the floodwater. However, in the case of intermediate vegetation, the spacing between vegetation elements is close to one another, resulting in the generation of intense wake interaction and vortex shedding, which further improves the turbulence, signifying energy dissipation more effectively. Further, it can be seen in the surface roughness (Ke) distribution that most values are concentrated around zero, and only a few results go to higher roughness values (up to 25). This is an asymmetric dispersion that reveals that smooth or moderately rough conditions are the predominant conditions, with highly rough scenarios being less prevalent. Relative backwater rise has a broader distribution with maxima at 0.5 and 2.5, corresponding to a considerable variety in the hydraulic behavior related to different flow and structure conditions.

These distributions demonstrate that vegetation density and roughness are the major factors that determine the results of energy dissipation. Highest values of G/d, indicating the clear importance of vegetative resistance in flow regulation, which is consistent with [78], who pointed out drag and the generation of turbulence by different configurations of vegetation. Similarly, the Ke values imply that minimal and moderate roughness may contribute to the turbulence and energy loss to a great extent, in line with Zhang et al. [79]. Bimodal distribution of Fr substantiates that variable flow regimes have a direct impact on backwater effects and on turbulence. The distribution of Δh/ho shows that the hydraulic response is not homogeneous, thus proving again the necessity of hybrid defenses to have the benefits of both vegetation and roughness factors. These results confirm that artificial intelligence models have promised to identify nonlinear trends and optimize the strategies of dealing with flood risks by taking into consideration various interactions between parameters.

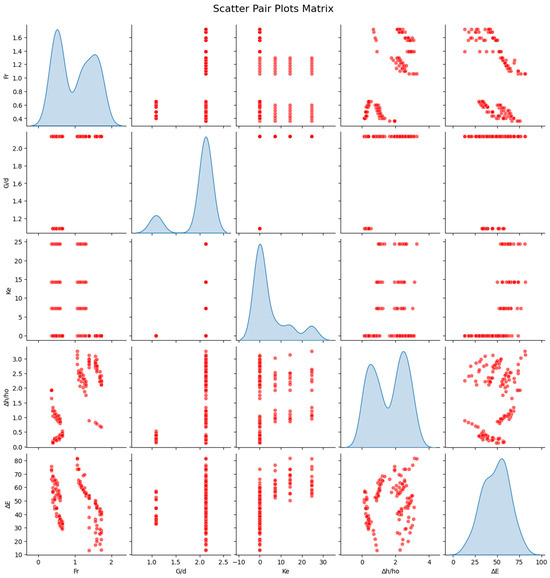

3.3. Pairwise Scatter Plot

The hydrodynamic interactions between flood and hybrid defense system-related variables are visualized by a scatter pair plot, as shown in Figure 4. In this section, a detailed assessment of this relationship is explained. A relationship between Fr and ΔE demonstrates that intense flow conditions minimize the effectiveness of hybrid defense to reduce floodwater energy dissipation. At higher values of Fr, the impact of the hybrid defense system on floodwater is reduced by the dominant flow momentum. Hydrodynamically, this is attributed to the bypassing of vortical structures and minimization of the exchange of energy with boundary elements to resulting reduced amount of turbulence-induced dissipation [80,81]. The weak scatter relationship of vegetation density (G/d) with ΔE depicted in the scatter pair plot indicates a lower influence of the G/d on floodwater energy dissipation. This may be due to the selected vegetation conditions, i.e., sparse and intermediate arrangement, which provides lower resistance to the flow compared to a dense arrangement of the vegetation. However, the sparse and intermediate vegetation arrangement also dissipates floodwater energy by the impact of drag, localized turbulence, and formation of a wake, improving the energy dissipation capability of the vegetation. The non-linear distribution, however, is representative of the multidimensional interactions that include vegetation density and reorganization of flow. At low to moderate G/d, there is increased turbulence due to wake interactions, vortex shedding, and greater density can lead to flow channelization; hence, there is less energy dissipation.

Figure 4.

Pairwise relationships among studied parameters indicate the linear and nonlinear relationship between pairs of (input–input and input–output) parameters, including Fr: Froude number, G/d: vegetation density, Ke: roughness, Δh/ho: roughness, and ΔE: energy dissipation.

Compared to Fr and G/d, the roughness conditions (Ke) have the strongest correlation with floodwater energy dissipation. A greater roughness condition of the defense system improves the creation of vortex, momentum diffusion, and boundary shear stress, as these factors increase turbulence intensity of flow and energy dissipation. Hydrodynamically, rough surfaces disrupt boundary layers, generate secondary currents, and enhance eddy formation, thus leading to great loss of energy. Further, the relative backwater rise has a weak positive relation with floodwater energy dissipation, demonstrating the capability of the hybrid defense system in water storage and promotion of hydraulic adjustment. However, the role of relative backwater rise is limited in understanding direct turbulence generation. Additionally. Kumar and Sharma [82] reported that greater turbulence was generated by the depth-induced drag interaction with a defense system of roughness and vegetation. Flood risk management can be improved with the combination of hydrodynamic studies and AI-based models; in this way, the nonlinear dependencies between the flow intensity, vegetation, surface roughness of dike and moat, and backwater effects will be better characterized. Optimized hybrid defense systems using AI have the potential to take advantage of turbulence generation and momentum exchanges to maximize energy dissipation and resiliency to extreme floods.

3.4. HEC-Contour Map

The spatial interaction among inputs (Fr, Ke, G/d, and Δh/ho) and the output variable (ΔE) is obvious from Figure 5. In this section, a detailed assessment of each input parameter is evaluated sequence-wise for a clear understanding of their influence on the energy dissipation of floodwater. The result demonstrates a significant impact of the Fr on the energy dissipation of floodwater. This shows that flow dynamics are significantly influenced by intense flow velocity, resulting in higher energy dissipation of floodwater, which aligns with the result of a previous study [64]. A previous study conducted by Pasha and Tanaka [83] reported that vegetation density has a significant influence on the floodwater energy dissipation because resistance to the flowing water in an open channel. In this study, the plot of the HEC contour map indicates considerable influence on mitigating floodwater energy. The findings of the current study align with work conducted by Elbagoury et al. [84], who reported that vegetation significantly altered flow by resisting the floodwater movement, thus increasing the energy dissipation phenomenon. The correlation between the energy dissipation with the upstream water level indicates that with a greater water level on the upstream, the energy dissipation tends to increase more. The trend is consistent with the observations of Dykstra and Dzwonkowski [85], who noted that high backwater rise by the defense system leads to considerable slowing down of the floodwater velocity, thus leading to a significant increase in field energy dissipation.

Figure 5.

HEC-contour map demonstrating a spatial relationship between input (Fr: Froude number, G/d: vegetation density, Ke: roughness, and Δh/ho: relative backwater rise) and output (ΔE: energy dissipation) parameters.

Roughness of the defense system plays a critical role in influencing floodwater energy dissipation. The higher values of the defense system roughness resulted in greater energy dissipation of floodwater. The roughness parameter in the model represents the case in the real world where rough surfaces decrease flood velocity and result in increased energy dissipation. The analysis provides insight into the need to have a hybrid defense system incorporated into flood risk management systems, including dikes, moats, and vegetation. The HEC-contour map gives a clear graphical representation on the way these parameters interact to influence the optimum design of the hybrid defense systems that can be made both environmentally sustainable and structurally friendly.

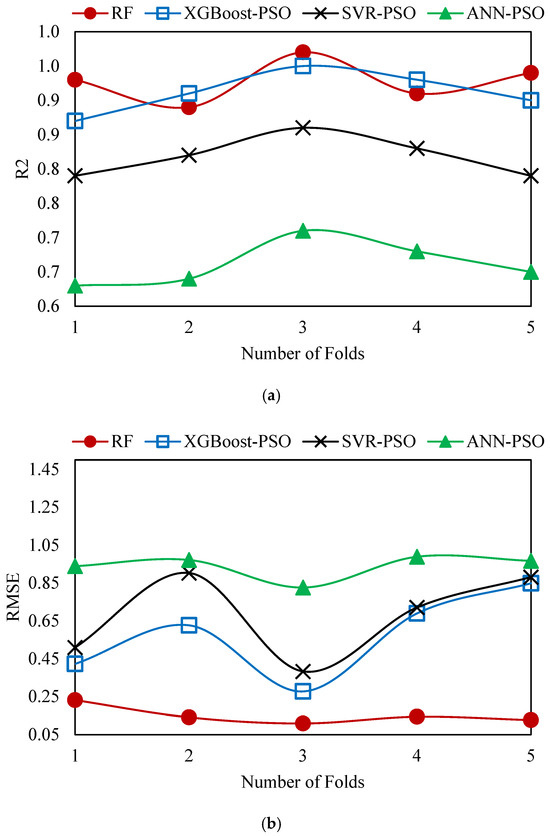

3.5. 5-Fold Cross Validation

In this study, for predicting floodwater energy dissipation, a detailed analysis of the optimizing model parameters through a five-fold cross-validation technique was performed utilizing four different ensembled learning models, demonstrating limitations and robustness of each model, as shown in Figure 6a,b. Among the tested models, RF demonstrated significant predictive performance with R2 and RMSE values ranging from 0.89 to 0.97 and 0.10 to 0.23, respectively. The high R2 and low RMSE suggest that the model effectively captures nonlinear hydraulic interaction while reducing overfitting through ensemble averaging. Such performance indicates the ability of the RF model to capture nonlinear hydraulic processes and reduce overfitting through ensemble averaging. XGBoost-PSO was also competitive with the highest single-fold accuracy (R2 = 0.95) but with greater variability in RMSE (0.277–0.849), which suggests that it is sensitive to data partitioning. The high RMSE values of some folds indicate that XGBoost-PSO is capable of capturing complicated patterns of the flows; however, its boosted tree operator might enhance the error of a fold with slightly different flow patterns or energy dissipation states. In SVR-PSO, moderate predictive power was found with a range of R2 values (0.79 to 0.86), although the relatively large RMSE (0.38 to 0.90) indicated that it had challenges in capturing nonlinear interactions of turbulence, velocity, and depth in dissipating energy. Among the tested models, the ANN-PSO showed comparatively lower performance, whose R2 values only going up to 0.71, and RMSE values remained consistently high (0.82–0.98). This pattern is likely due to limited data density, as neural networks generally require large datasets for reliable generalization. A known limitation of ANN models is their reduced performance when trained on small datasets, which is often the case in hydraulic laboratory experiments and field measurements.

Figure 6.

Model Optimization through 5-fold cross-validation: (a) coefficient of determination (R2) and (b) root mean square error (RMSE).

All the comparative analyses indicate that tree-based ensemble models (RF and XGBoost-PSO) are more suitable to predict energy dissipation of floodwater because of their flexibility to nonhomogeneous hydraulic conditions and their capability in predicting nonlinearities with multiple scales. The results have a great importance in hydraulic engineering, where the correct quantification of energy dissipation is vital in the design of flood control structures with resistance to erosion. Predictive models can enhance the assessment of hydrodynamic actions, minimize uncertainties during structure design, and improve the overall performance of flood-control infrastructure under multiple flow regimes. Moreover, the strong performance of RF suggests a practical and computationally efficient option for integrating machine learning into hydraulic design procedures, supporting more resilient and information-based decision-making in flood risk management.

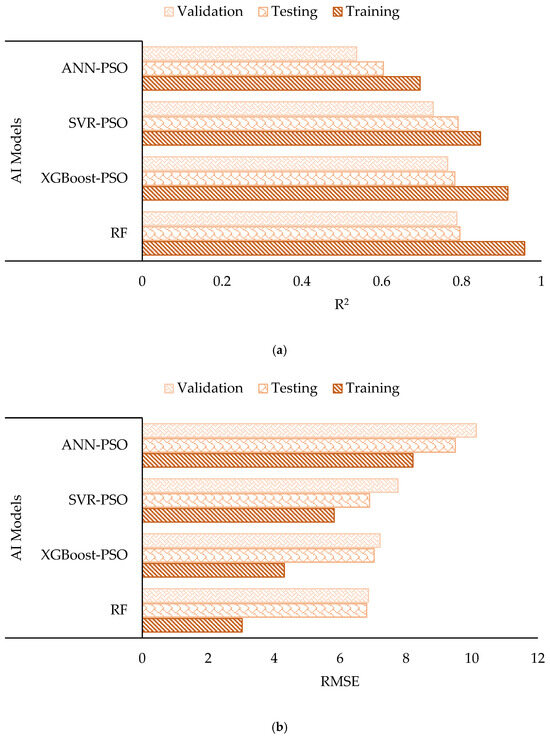

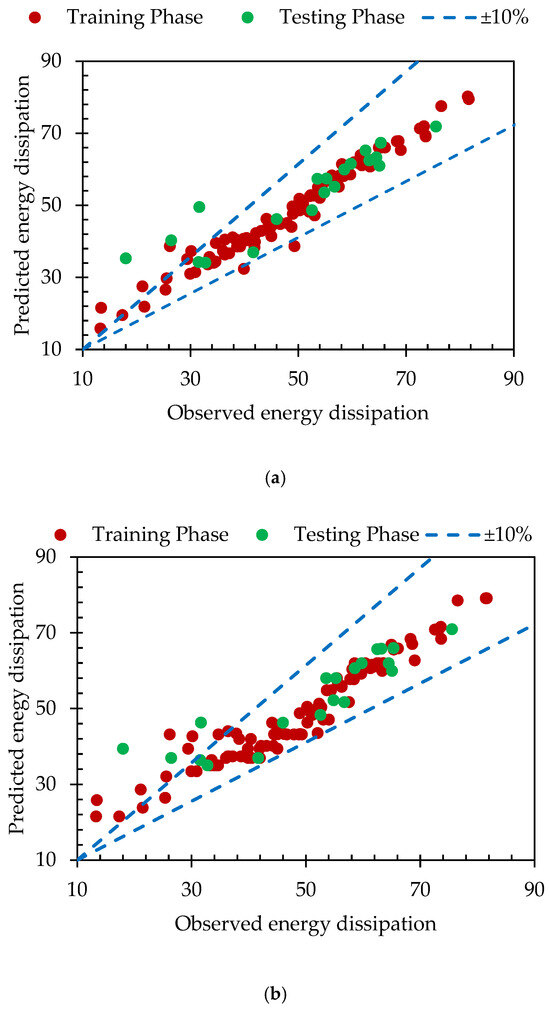

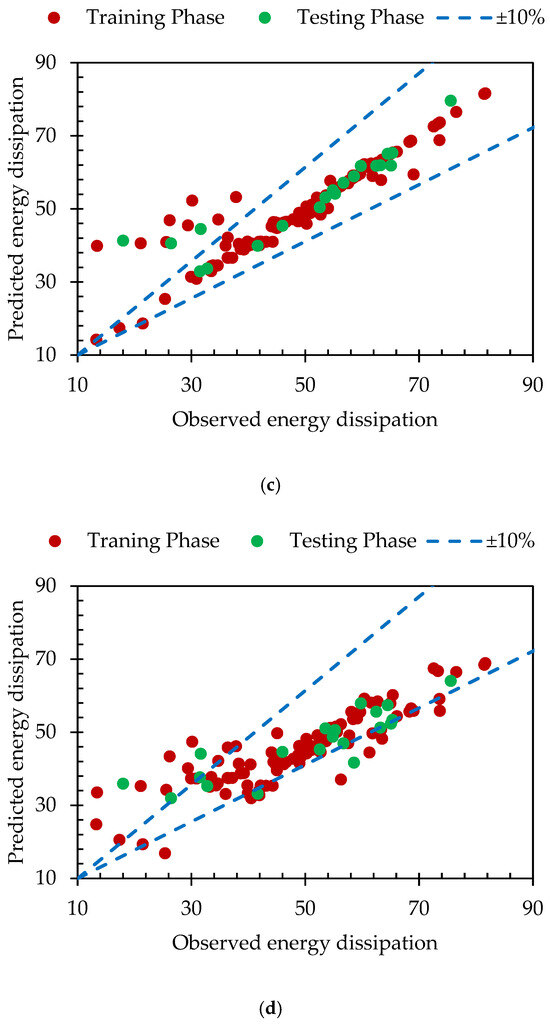

3.6. Evaluation of AI Models

Under this heading, a detailed evaluation of the four different tested models is conducted to understand the predictive capability of each model in flood risk management using a hybrid defense system, as shown in Figure 7a,b. The evaluation of each AI model was assessed through the coefficient of determination (R2) and root mean square error (RMSE). However, in this section, the performance of each model is explained one by one for a clear understanding. The performance of each model was assessed by considering R2 and RMSE values in the training phase. Out of the four models, the RF outperformed because of the greater R2 and lower RMSE values of 0.958 and 3.03 (Figure 7a,b). The result demonstrated 96% of variance in the data series in the training phase of the model. However, the R2 and RMSE values of the RF models drop in the testing and validation phases to 0.796, 0.788, 6.81, and 6.86. The higher values of R2 and RMSE in the training phase indicate better performance of the RF model compared to the testing and validation phases. The RF model struggles with unseen data series for generalization, reflected in the RMSE values in the testing and validation phases. Despite this, the RF model provides a good prediction of floodwater energy dissipation across different phases.

Figure 7.

Result of model performance evaluation across different phases, such as training, testing, and validation: (a) coefficient of determination (R2) and (b) root mean square error (RMSE).

The XGBoost-PSO model has slightly less prediction capability compared to the RF model, with an R2 value of 0.916 in the training phase, demonstrating 91.6% of variance in the data series. Like the RF model, the R2 value of the XGBoost-PSO model drops to 0.783 and 0.765 in the testing and validation phases. Further, the XGBoost-PSO model exhibits higher values of RMSE in the case training (4.31), testing (7.04), and validation (7.21) phases (Figure 6a,b). The XGBoost-PSO model performed worse than the RF model in terms of the R2, and its RMSE scores indicate that the average error is high, particularly during the validation process. This makes an XGBoost-PSO a good predictive model, but not as robust as RF in generalizing new data. The SVR-PSO model has an R2 value of 0.847 in training, which means that it captures 84.7 percent of the variations. Its performance decreases considerably under testing (0.791) and validation (0.729) conditions, with the lowest R2 in all models. RMSE values also have a higher value in SVR-PSO, beginning with 5.82 in training, followed by 6.90 in testing, and 7.76 in validation. Although its performance remains high, the SVR-PSO model still has more errors than RF and XGBoost-PSO, which means it has more difficulty in fitting the data and generalizing their performance to unseen data points. The ANN-PSO model indicates the lowest R2, which is 0.696 (training), meaning that it only explains 69.6% of the variance. This performance drops significantly in testing (0.604) and validation (0.537) sets, thus confirming that the ANN-PSO model should be generalized. Additional evidence can be found in the RMSEs, which are 8.21 during the training, 9.49 during testing, and 10.13 during validation. The values of errors are maximum, which implies low predictive ability of this model, at least on previously unseen data. Figure 8a–d depicts the predictive capability of the tested AI model in predicting floodwater energy dissipation.

Figure 8.

Model validation scatter plots of predicted values in the training and testing phases of the various models: (a) RF, (b) XGBoost-PSO, (c) SVR-PSO, and (d) ANN-PSO.

For developing complex and nonlinear AI models such as ANN-PSO, SVR-PSO, XGBoost-PSO, and RF with 136 data points, out of which 95 (70%) were used in the training phase. This distribution of the data points used in the present study can influence generalizability of the model and promotes the chance of overfitting issue as noticed in the case of RF model with R2 = 0.958 (training phase) drop to R2 = 0.79 (testing/validation phase) indicate that the model has not captured the complete complex and nonlinear interaction between diverse flow and hybrid defense system. However, to overcome this issue, the current research attempt has been made to utilize PSO-based optimization techniques for hyperparameter tuning to reduce the issue of overfitting in the case of other AI models like ANN, SVR, and XGBoost. Therefore, the present research recommends the utilization of larger data series in future research to capture a full understanding of the tested AI models for assessing the effectiveness of the hybrid defense system in flood risk management. The performance of the AI models for the hybrid defense system in flood risk management can be improved by the integration of physics-ensembled modeling. Furthermore, the future may integrate native modeling approaches, such as regression and decision trees, that perform better under limited data points. Lastly, the present study recommended that for enhancing the performance of the RF, the model should be optimized with PSO/Adam for better performance compared to the values achieved in this study.

The data used in the study were obtained from laboratory experiments and published literature. Although the datasets are diverse, their overall size is relatively small, which limits the generalization of developed models. Nevertheless, advanced ensembled approaches, including Random Forest and PSO architectures, showed better performance for the hydraulic conditions used in this study. These results indicate that the models are effective for the tested scenarios; however, their application to other flood events should be treated with caution. This is mainly because the study relies on controlled laboratory datasets that represent specific roughness, flow regimes, and vegetation conditions characteristic of a single flood-affected region, namely the Indus River floodplains.

Flood characteristics vary considerably between regions due to differences in soil properties, vegetation types, configuration, geometrical variation in the channel, sediment load, and hydrodynamic stress. As a result, models trained on limited experimental conditions may not directly capture the complexity of flood behavior elsewhere. Therefore, for the broader regional applicability, the models proposed in this study should be trained and validated using field data such as hydrological, catchment, mountainous rivers, arid floodplains, urban floodways, deltaic systems, vegetation types and configurations, and geometrical variation in the dike and moat. Expanding the dataset in this way would improve model robustness, transferability, and minimize the risk of overfitting by considering diverse climatic and geomorphological scenarios. Overall, the combined study of the hybrid flood defense system and ensembled learning framework demonstrated significant performance in the reduction in floodwater energy; however, future research should focus on the large-scale and site-specific data series to enhance its prediction capability for a wider range of flood-prone regions.

Numerous works have discussed the effectiveness of the Random Forest model in prediction applications, especially in the way it deals with non-linear data with great accuracy [86]. RF has been characterized by resistance to overfitting and is capable of handling large and complex datasets, which is in line with the present findings. The XGBoost is also a powerful model often recommended due to its computational effectiveness and performance, but it may also experience overfitting unless carefully adjusted [87]. SVR has been extensively applied to regression tasks, although proper tuning of hyperparameters is usually required. As it occurs in this research, it performed worse in generalization. The ANN model, being a powerful model, can be set up to either demand much data and special regularization to avoid the overfitting issue [88]. The results are important in stressing the significance of the model choice in consideration of the characteristics of the dataset and the requirements of careful tuning to enhance generalization. Comparatively, the RF model appears to produce the most impressive results with the highest R2 during training and similarly consistent results in testing and validation. The XGBoost-PSO performs nearly equally well, except that its RMSEs are slightly higher. The SVR-PSO and ANN-PSO models are less effective with lower R2 and higher RMSE values, which shows that they are less effective in capturing data variance and are worse at generalization. The findings of the AI models demonstrated that the RF model has strong predictive capability in assessing the floodwater energy dissipation capability of the hybrid defense system in flood risk mitigation under diverse flow, vegetation, and roughness conditions. This was because of the RF model’s capability of handling the overfitting issue comparatively better than the ANN-PSO and SVR-PSO on the prediction accuracy and the error levels. Although the XGBoost-PSO provides competitive results, the corresponding larger RMSE values indicate that the model might not be as consistent as the RF model.

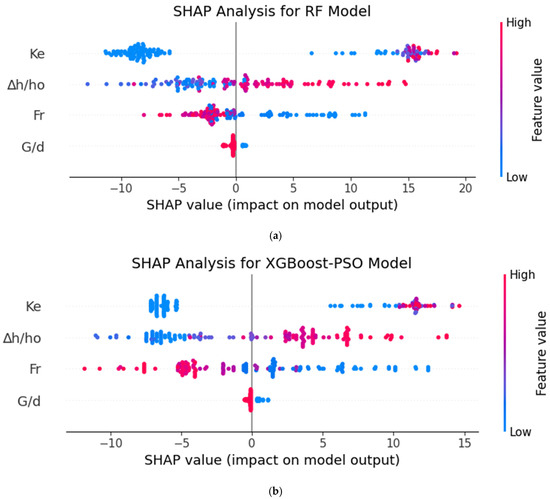

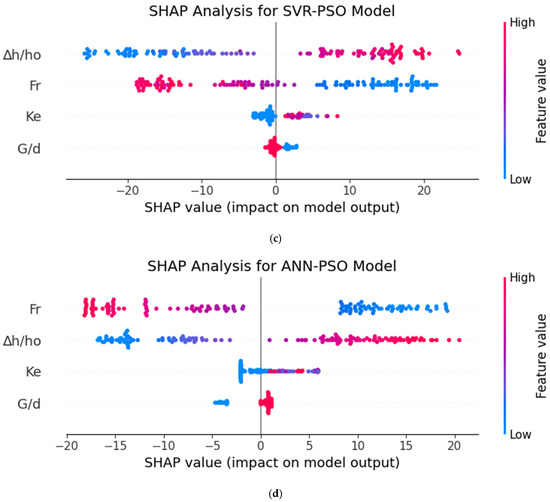

3.7. SHAP Analysis

SHAP analysis is an emerging technique usually used for understanding the contribution of individual inputs in the prediction of output parameters. In this study, SHAP analysis was performed to understand the effectiveness of driving parameters in flood risk management. By the utilization of the SHAP analysis values to input parameters like Froude number, vegetation density, relative backwater rise, and roughness of defense system, the analysis signifies the contribution of these input parameters in the flood risk management. In this study, the SHAP analysis performed for four different tested AI models is depicted in Figure 9a–d. In the SHAP analysis plot for the RF model, roughness conditions of the defense system have a significant influence on floodwater energy dissipation, with SHAP values ranging from −13 to 20. However, the SHAP value ranged from −15 to 15, which decreased in the case of relative backwater rise. This indicates that roughness conditions are critical parameters influencing flood risk management compared to relative backwater rise. Further, in the case of Fr and G/d, the SHAP values reduced significantly compared to roughness and relative backwater rise. The SHAP ranges observed for Fr and G/d in the case of the RF model are −8 to 12 and −2 to 1, respectively.

Figure 9.

Result of SHAP analysis for different AI models, indicating influence of input (Fr: Froude number, G/d: vegetation density, Ke: roughness, and Δh/ho: relative backwater rise) and output (ΔE: energy dissipation) parameters: (a) RF, (b) XGBoost-PSO, (c) SVR-PSO, and (d) ANN-PSO.

Moreover, in the case of the XGBoost-PSO, the SHAP analysis shows the dominating influence of the roughness variation on floodwater energy dissipation. The SHAP analysis demonstrated a greater positive value of 15 for roughness conditions, which reduced to 13 in the case of relative backwater rise. However, the feature value of the SHAP analysis ranged up to 12, in the case of the Froude number, and 1.5 for vegetation density. The result of the XGBoost-PSO followed a similar trend that was observed for RF models with lower feature values, as shown in Figure 8a,b. Following RF and XGBoost-PSO models, it was observed that the relative backwater rise has a greater impact on the floodwater energy dissipation in the case of SVR-PSO with a feature value of 23. Further, for Froude number, roughness, and vegetation density, the feature value of the SHAP analysis reduced up to 22, 10, and 3, respectively. Lastly, the result of the SHAP analysis, in the case of the ANN-PSO model, demonstrated a significant contribution of the Froude number in dissipating floodwater energy, with feature values ranging from −20 to 20. This value ranged from −17 to 21, which was reduced in the case of a relative backwater rise. The feature values reported in the SHAP analysis for roughness and vegetation conditions ranged from −2 to 6 and −5 to 1, respectively. The SHAP analysis results indicate that the effects of the input parameters on the output in the different models are different. Roughness exhibits the maximum effect in the RF and XGBoost-PSO models. It aligns with the literature, implying that the parameter of roughness is one of the important parameters affecting the energy dissipation within river channels since it directly affects the resistance to flow [89].

The SHAP analysis conducted in this study provides a critical bridge between hydraulic phenomena, such as floodwater energy dissipation by a hybrid flood defense system and ensemble learning-based prediction. A detailed analysis of the SHAP values reported for various models demonstrates a significant contribution of the roughness, indicating that surface irregularity of the dike and moat within the hybrid flood defense system improves energy dissipation. The result from the SHAP analysis aligns with the intensity of stress developed, turbulence generation, and secondary circulation through the rough dike and surface of the moat. The roughness induced on the body of the dike and moat enhances diffusion of momentum by promoting kinetic energy dissipation. Furthermore, the vegetation considered in this study demonstrates a nonlinear contribution pattern with moderate SHAP values. Higher vegetation density (intermediate) results in enhanced SHAP values by the combined influence of stem-generated drag, vortex shedding, and wake interactions, causing the mixing of turbulence. In contrast, the higher Froude number demonstrated intense flow conditions, resulting in negative SHAP values. The negative SHAP values demonstrate physical limitations of the hybrid flood defense system under extreme flow conditions, where the maximum energy of the floodwater is dissipated through the rough dike and moat, as well as vegetation predicted by ensembled learning models. The results of the SHAP show that a hybrid defense system is most effective at moderate flow intensities when roughness-induced turbulence and vegetation drag are combined. Therefore, the tested models for predicting energy dissipation through rough dike and moat, along with vegetation located downstream of the moat, provide significant applicability of an AI-based framework under limited conditions; however, future studies should explore the contribution of these models under diverse flow regimes and vegetation conditions.

The relative backwater rise is very influential in the SVR-PSO modeling according to its central role in floodplain inundation and flow patterns. In the ANN-PSO and RF, the Froude number Fr also exerts significant relevance, as studies indicate the impact of the Froude number on the flow regime as well as the channel stability. The lower effect of vegetation density tends to be consistent across all the models, and this could imply that although vegetation has those important roles to play, it has less controlling effect in flood risk modeling relative to the hydrodynamic parameters such as Ke and Δh/ho. This SHAP analysis offers critical knowledge on the relative relevance of different parameters to the prediction of flood behaviors. The superiority of roughness conditions in models implies that the roughness of the defense system should be considered to manage the flood using suitable vegetation and structural measures. The impact of relative backwater rise implies that the concept of controlling backwater effects and water levels may be critical in controlling flood risk. Through the utilization of these results, flood management organizations can focus on the parameters that have the greatest effect in modeling and mitigation interventions in their flood-vulnerable regions, thus leading to more effective interventions in areas vulnerable to floods.

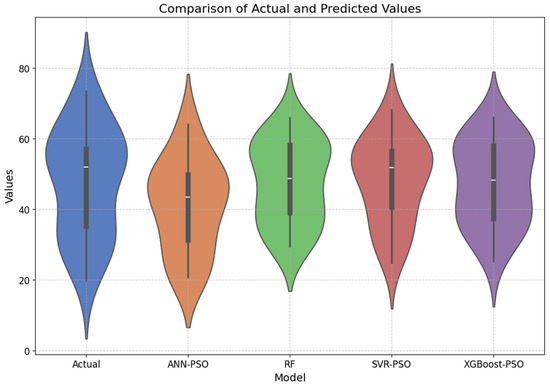

3.8. Violin Plot

Figure 10 depicts the result of a violin plot for predicting floodwater energy dissipation in comparison to actual energy dissipation using different AI models. The outcome of the violin plot in Figure 10 compares the predictions of five models, such as XGBoost-PSO, ANN-PSO, SVR-PSO, RF, and the Actual values. The violin plot suggests that XGBoost-PSO, the mode of spread of the dataset of predictions, is the narrowest in the middle, which means that its predictions are relatively consistent with the actual values. ANN-PSO demonstrates a similar but wider distribution after XGBoost-PSO, indicating a relatively high consistency in the predictions, yet the variation is a bit higher. SVR-PSO has a broader distribution of predictions, which means that, although it remains fairly accurate, it is less predictive in nature than the first two models. RF shows the greatest dispersion, indicating that the model can capture many variations in data, but the results are much more dispersed. However, the trend of the model performance based on R2 and RMSE shows different results. Based on the R2 and RMSE values of the models, the result demonstrated that RF exhibits higher accuracy in predicting floodwater energy dissipation, reducing the error between predicted and observed energy dissipation effectively compared to the rest of the models.

Figure 10.

Comparison of the prediction of the four AI models against actual values of energy dissipation using a violin plot depicting the visualization of data distribution.

The difference between the violin plot and the rest of the evaluation metrics is explained by the characteristics of each of the methods. The violin plot highlights the distribution of predicted values, and it prefers a model using closely clustered predictions such as XG Boost-PSO. In the present research paper, the findings from the violin plot demonstrate consistent performance in the case of XGBoost-PSO, while being accurate in the case of the RF model. The consistency reported for the XGBoost-PSO model represents (low-variance predictions) how closely the value of the predictions was, because of sequentially boosted trees. Furthermore, the present study reported a narrow distribution, which indicates higher consistency and lower systematic bias. In contrast, the RF model demonstrated greater accuracy with a lower value of mean square error and a higher coefficient of determination, resulting in a wider spread. Random Forest takes averages of numerous independent trees, which minimizes errors in diverse conditions, leading to more accurate results but with a greater range of predictions. Therefore, XGBoost focuses more on stability, whereas RF can obtain more accurate, complex nonlinear patterns. Nevertheless, R2 and RMSE evaluate the fit of the models to the data and error reduction. These metrics show that RF works better because it captures the complex relationship and describes it in such a way that generates the results with accurate prediction on average, despite a more dispersed prediction. Therefore, although XGBoost-PSO provides consistent accuracy, RF is highly accurate in the complexity of capturing the data and is less prone to errors, and hence, RF is the best-performing model based on a broader assessment.

3.9. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses like ANOVA and the t-test were adopted to confirm the performance of various models used in this study. The purpose of the ANOVA test was to compare four different models utilized in this study, while the t-test compared the best performance model (RF) evaluated through performance metrics like R2 and RMSE, individually with other models. Previous research reported that statistical analyses like ANOVA and t-test determine the significance of the model [90,91]; hence, in this study, a detailed assessment of the RF model in comparison to other models was evaluated through the p-value. The threshold of p-value for ANOVA and t-test is reported to be less than or equal to 0.05; otherwise, the model would not be significant. Therefore, the ANOVA and t-test conducted in this study show different trends of p-values for different AI models, as shown in Figure 11. In this study, ANOVA and t-tests were applied to evaluate whether differences in model performance were statistically significant. A p-value of ≤0.05 was considered the threshold for statistical significance. The RF model met this criterion, with p-values of 0.031 (ANOVA) and 0.039 (t-test), indicating that its superior performance is statistically supported. The XGBoost-PSO model produced p-values close to the significance threshold (0.047 for ANOVA and 0.045 for t-test), suggesting marginal significance. In contrast, the SVR-PSO and ANN-PSO models yielded p-values above 0.05, indicating that their performance differences relative to RF are not statistically significant, even though they may still show acceptable predictive behavior in practical terms according to the RMSE and R2 values. These results confirm that RF is the only model demonstrating statistically significant superiority among the four tested methods. The results of the statistical analysis determined that the Random Forest model has greater predictive power in assessing the effectiveness of the hybrid defense system for flood risk management. The precise prediction, predictive capability, and performance of the RF model help engineers and planners to optimize flood mitigation approaches through the combined influence of dike, moat, and vegetation, resulting in lowering uncertainties and improving flood resilience of the regions predominantly affected, for enhancing communities and infrastructure protection.

Figure 11.

Evaluation of AI models using statistical analysis (ANOVA and t-test), considering the p-value of each model for comparing the results of different AI models studied in this research.

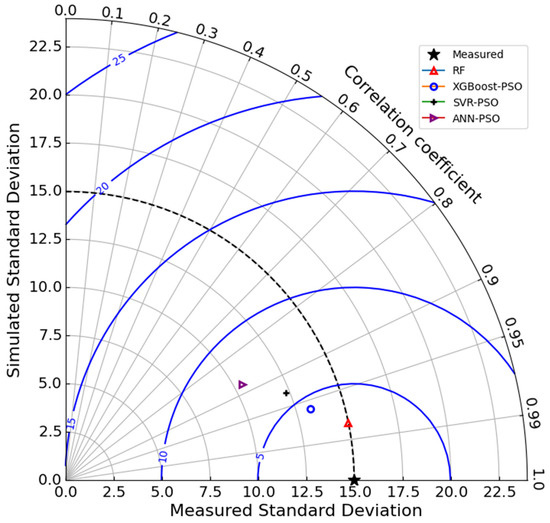

3.10. Taylor’s Diagram