Abstract

Industrial robotic workstations contribute substantially to the total energy demand of modern manufacturing, yet most existing energy-saving approaches focus on modifying robot trajectories, motion parameters, or the position of the robot’s base. This paper proposes a novel methodology for the automatic optimization of the spatial placement of a fixed technological trajectory within the robot workspace, without altering the task itself. The method combines pre-simulation filtering of infeasible configurations, large-scale energy simulation in ABB RobotStudio, and real measurement using a dual acquisition system consisting of the robot’s controller and an external power meter. A digital twin of the workstation is used to systematically evaluate thousands of candidate positions of a standardized trajectory. Experimental validation on an ABB IRB 1600–10/1.2 confirms a 23.4% difference in total energy consumption between two workspace configurations selected from the simulation study. The non-optimal configuration exhibits higher current draw, greater power variability, and a more intensive warm-up phase, indicating increased mechanical loading arising purely from geometric placement. By providing a scalable, trajectory-preserving approach grounded in digital-twin analysis and IoT-based measurement, this work establishes a data foundation for future AI-driven predictive and adaptive energy optimization in smart manufacturing environments.

1. Introduction

The increasing integration of automation within industrial settings has been paralleled by a heightened awareness of the substantial energy demands associated with robotic systems. As factories evolve towards smart manufacturing paradigms, the significance of energy consumption has come to the forefront of operational concerns, especially concerning sustainability and carbon footprint reduction. Research indicates that industrial sectors are responsible for nearly 37% of global energy consumption and approximately one-third of greenhouse gas emissions, reflecting the critical need for sustainability initiatives [1]. Consequently, the optimization of energy use in automated systems is essential for achieving operational efficiency while addressing the global imperatives of climate change and resource conservation [2]. Robotic workstations, as critical components of automated manufacturing, play a vital role in enabling streamlined operations, yet they also contribute significantly to overall energy consumption within factories [3].

Despite advancements in automation and the proliferation of various energy optimization strategies, existing approaches to enhancing energy efficiency in robotic systems frequently fall short when faced with the complexity of dynamic manufacturing environments. Many current methods rely on manual adjustments and human oversight, which are not only inefficient but also prone to variability and inconsistency across varied operational contexts. Such limitations highlight a pressing research gap: the need for fully automatic and scalable energy optimization techniques that can autonomously adapt to the demands of multi-robot configurations in real time [4]. This paper addresses this gap by proposing a comprehensive framework for optimization of energy consumption in robotic workstations, which includes the application of advanced algorithmic strategies such as artificial intelligence and machine learning [5].

The significance of adopting automatic optimization methods cannot be overstated, particularly in light of the increasing pressures on industries to reduce operational costs and environmental impacts simultaneously. Automatic systems can lead to remarkable efficiencies by minimizing wasted energy, enhancing productivity, and ensuring greater compliance with emerging sustainability standards associated with Industry 4.0 initiatives [6]. Furthermore, the implementation of such methodologies holds the potential to lower operational costs significantly while aligning manufacturing processes with the principles of a green economy [6]. The proposed methodology is fully compatible with emerging AI-driven decision frameworks and IoT-based sensing architectures widely adopted in next-generation manufacturing systems. Related geometry-aware learning has also been demonstrated in robotic 3D perception [7]. By leveraging dual-source, real-time measurement and a digital-twin simulation workflow, the method establishes a data foundation suitable for machine-learning–based prediction and optimization of robotic energy consumption.

A crucial prerequisite for any optimization effort is the accurate measurement and monitoring of energy consumption in robotic workstations in real time. Recent years have witnessed the development of various methods and technologies that enable a detailed understanding of how specific robot functions impact energy use. For example, Heredia et al. introduced an energy consumption disaggregation pipeline (ECDP) for lightweight robots, which allows for precise analysis of consumption patterns and supports more effective energy management [8]. Similarly, Torayev et al. demonstrated that modular online systems can be employed to track and dynamically adjust energy use in real time across multiple industrial settings with FANUC robots, thereby enhancing efficiency while reducing costs [9].

Another important aspect lies in the spatial configuration of robotic cells. Studies by Ružarovský et al. highlight how optimized robot placement within the workspace can significantly reduce overall energy demands [10,11]. Other research has shown that genetic algorithm-based optimization methods are effective in minimizing robot travel distances and, consequently, overall energy consumption [12]. In addition, predictive models and simulations have emerged as key tools for tracking and forecasting energy patterns, offering scientifically grounded insights that guide the design and operation of robotic systems [13].

Trajectory optimization has also been shown to play a decisive role in lowering energy consumption. Research by Zhou et al. and Peta et al. demonstrates that tailoring robot motion trajectories to account for dynamic, kinematic, and task-specific parameters can yield substantial energy savings [14,15]. Together, these monitoring, modeling, and optimization strategies lay the foundation for advancing automatic energy-efficient solutions aligned with the principles of Industry 4.0 and the green economy.

In this context, the objective of this paper is to present a novel methodology for the automatic optimization of energy consumption in robotic workstations. Through rigorous validation and real-world simulations, this research aims to illuminate the pathways for integrating sustainable energy practices into the operational fabric of smart manufacturing.

2. Materials and Methods

The methodological framework of this study addresses the issue of energy efficiency in industrial robotic workstations. Not only when designing a workspace can an industrial robot be placed in a configuration that is not optimal from an energy perspective, even though it performs an identical technological task. At the same time, there may exist an alternative placement in which the same task is executed with reduced energy consumption. Therefore, the goal of this research is not to modify the trajectory of the task but to determine its most energy-efficient spatial configuration within the robot’s workspace.

Two alternative strategies can be considered: optimizing the location of the robot relative to the task trajectory or, conversely, optimizing the location of the task path relative to a fixed robot base. In this work, the second approach was adopted. By shifting the predefined path within the workspace, the influence of spatial placement on total energy consumption can be systematically evaluated. Since the number of possible trajectory placements in space is theoretically infinite, the search domain is discretized into a uniform three-dimensional grid, where each cell represents one potential configuration of the task trajectory.

A major challenge of this process arises from the large number of infeasible configurations that violate kinematic or reachability constraints. In conventional simulation environments, such as ABB RobotStudio 2025.2 [16], these invalid cases typically cause the simulation to stop, complicating data acquisition and increasing the total computation time. To address this issue, a pre-simulation filtering stage was developed to automatically detect and remove infeasible configurations before launching the simulations. The pre-simulation filtering significantly reduces the number of required simulation runs and accelerates the overall evaluation process.

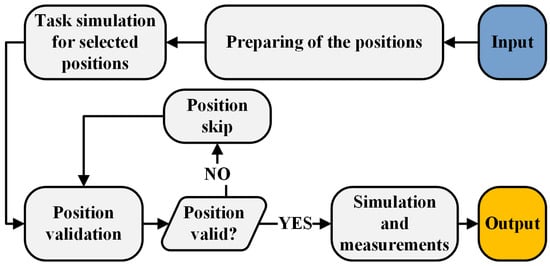

The proposed workflow Figure 1 consists of several stages. First, the spatial grid of candidate configurations is generated based on the robot’s kinematic limits and the predefined task trajectory. In the second stage, all infeasible configurations are filtered out using the developed validation algorithm. The remaining feasible configurations are then imported into RobotStudio, where each one is simulated to obtain the corresponding energy data. The instantaneous power and total energy consumption are recorded using the built-in Signal Analyzer tool and exported for further processing and comparison.

Figure 1.

Block diagram of the experimental workflow showing the sequence of position preparation, validation, simulation, and data export.

This procedure is particularly suitable for applications where the trajectory is technologically fixed, such as robotic deburring, gluing, sealing, or surface finishing. For these processes, the proposed method enables an automatic assessment of energy efficiency without modifying the production task itself, thereby supporting the design of more sustainable robotic workstations.

2.1. Robot Selection

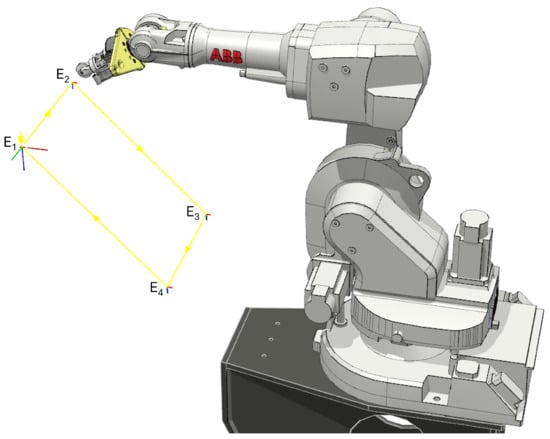

The experiments were conducted using the ABB IRB 1600-10/1.2 industrial manipulator (ABB Robotics, Västerås, Sweden) [17], see Figure 2. This six-axis serial robot provides a nominal reach of 1.2 m and a maximum payload of 10 kg. The mechanical structure weighs 250 kg, with a base footprint of 484 × 648 mm and a total height of 1.07 m. The robots positioning repeatability is 0.02 mm and a path repeatability is 0.06 mm. Joint motion limits are for axis 1, to for axis 2, to for axis 3, for axis 4, for axis 5, and for axis 6. Maximum joint velocities reach up to 460°/s. The workspace corresponds to a hemispherical volume with a maximum radial reach of 1.225 m and a minimum reach of 0.45 m, which enables efficient execution of mid-sized manipulation tasks. Nominal electrical input ranges from 200 to 600 V at 50/60 Hz, with an average operational power consumption of about 0.6 kW. During experiments, the manipulator was controlled using the IRC5 controller [18], which allowed for synchronized acquisition of joint motion and power data for analysis. A custom-designed end-effector with a total mass of 2.8 kg was mounted to the tool flange, corresponding to approximately 28% of the nominal payload capacity.

Figure 2.

ABB IRB 1600–10/1.2 industrial robot used for simulation and experimental validation.

2.2. Trajectory

In this study, the robot motion was based on a standardized reference trajectory defined by the ISO 9283:1998 standard [19], commonly referred to as the ISO cube trajectory. This trajectory is widely used in robotics research and by industrial robot manufacturers, such as ABB, for benchmarking motion performance and dynamic behavior. The use of this trajectory ensures that the robot executes a well-defined and reproducible motion pattern, allowing for a consistent evaluation of the proposed optimization approach.

The trajectory connects the cube vertices E1–E2–E3–E4 and forms a closed planar loop lying in a diagonal plane of the ISO test cube. In this study, the trajectory was implemented in the ABB RobotStudio environment using a WorkObject that defined the local coordinate system of the task. The four trajectory targets (E1–E4) were specified relative to this WorkObject, ensuring a fixed geometric relationship between them. The WorkObject is located at the target E1, allowing the entire trajectory to be positioned within the robot’s workspace while preserving its geometry, as illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Implementation of the ISO 9283 trajectory in ABB RobotStudio for the ABB IRB 1600-10/1.2 robot. The trajectory targets were defined relative to a WorkObject, which specifies the local coordinate system of the task and is located at point E1.

The length of the cube side is set to , which corresponds to the configuration specified by ABB for the IRB 1600 series. However, the choice of this trajectory does not limit the proposed optimization framework, as the developed methodology can be applied to any predefined trajectory geometry. The ISO cube trajectory was selected for its standardized definition, reproducibility, and broad acceptance in robotics research and industrial benchmarking.

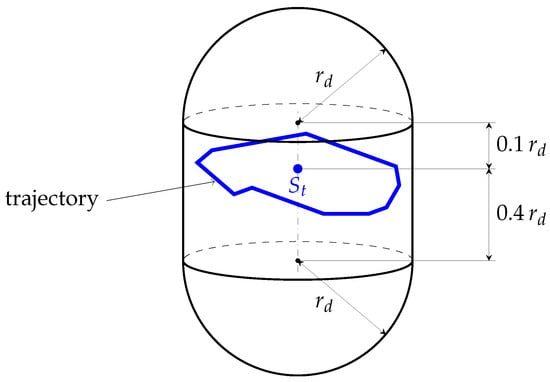

2.3. Pre-Simulation Filtering Stage

As mentioned earlier, this step is performed to reduce the large number of possible discrete trajectory positions relative to the robot by eliminating those in which the robot cannot execute the trajectory. The candidate poses are generated on a regular grid that fills the entire workspace. The first very coarse filtering criterion removes grid points that the robot cannot reach due to its geometric limitations. Only points that are inside a capsule-shaped volume (Figure 4) are retained. The capsule has a radius equal to the robot’s reach (a parameter available on the datasheet) and a height of . The capsule shape is chosen to reflect the typically greater vertical reach of industrial robots.

Figure 4.

Bounding volume for feasible trajectory locations relative to the robot.

The trajectory positions lying inside the capsule are then validated using the following procedure:

- The trajectory is translated to a particular position.

- A quick initial validation is performed by checking whether the robot is able to reach 10 selected points distributed evenly along the entire trajectory. The inverse kinematics solution and potential collisions are evaluated. This step speeds up the overall process by quickly eliminating trajectories that are partially out of reach.

- If the previous check passes, the entire trajectory is validated in detail. The inverse kinematics, collisions, and joint speed limits are evaluated. The calculation terminates as soon as an invalid point on the trajectory is found.

- If all checks pass, the trajectory location is considered valid and is included in the main simulation.

For the purpose of validation, the trajectory is divided into discrete points at distances determined by a defined , for example s. At each point on the trajectory, the inverse kinematics is computed to verify whether the robot can physically reach the target. Inverse kinematics provides joint angles at each trajectory point, and those are used to approximate joint velocities around each trajectory point using the central difference approximation. Joint velocities are compared to velocity limits provided in the data sheet.

Collision checking is necessary not only to exclude collisions between the robot and obstacles in the workspace but also to detect self-collisions between individual robot links. The check is first performed in a coarse manner using oriented bounding boxes (OBBs)—each robot link has its own OBB. This method is very fast but significantly pessimistic. If no collision is detected, no further verification is needed. If a collision is detected, a detailed check follows, using a simplified full 3D model of the robot links.

The entire procedure is executed within a custom application developed specifically for this task. The application is written in C++ and uses Direct3D 11 for visualization. The computations are performed in parallel across multiple threads. The application is capable of evaluating a large number of poses in a short time. However, since we do not have access to a dynamic model of the robot, the tool is suitable only for coarse filtering of trajectory poses.

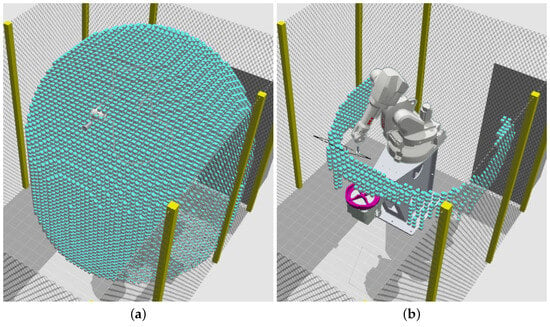

An example of the visualization produced by the application, showing the full grid of candidate positions and the corresponding set remaining after coarse filtering, is provided in Figure 5. In total, 66,873 candidate positions were initially generated, of which 794 remained after applying the coarse filtering stage, which required approximately 1.36 s of computation in the presented case study.

Figure 5.

Visualization of the candidate trajectory positions processed by the custom filtering tool. (a) Complete set of grid-sampled trajectory positions within the workspace. (b) Remaining subset after applying the coarse filtering stage. Cyan points represent grid-sampled candidate positions.

2.4. Simulation

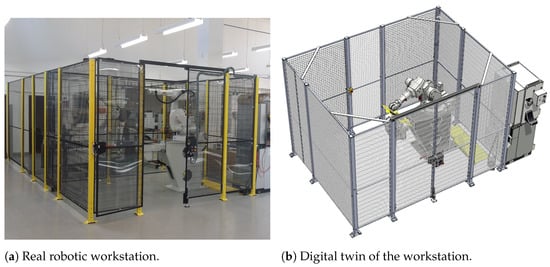

The experimental evaluation was carried out in a virtual environment created in ABB RobotStudio, which was designed as an exact digital twin of the real robotic workstation (see Figure 6). Layout, tool geometry, fixtures, and environmental constraints were modeled on a 1:1 scale, ensuring that the simulated conditions fully corresponded to those of the physical setup.

Figure 6.

Comparison between the real robotic workstation (a) and its digital twin in ABB RobotStudio (b).

After determining the most suitable WorkObject positions using custom software (see Section 2.3), the resulting configurations were imported into the RobotStudio environment for validation. Each candidate position was simulated using the ABB IRB 1600-10/1.2 robot controlled by the IRC5 controller and programmed to follow the trajectory of the ISO cube.

To verify the robot’s ability to reach and execute operations throughout the workspace, a custom reachability and trajectory validation routine was implemented in the RAPID programming language (see Algorithm 1). The algorithm systematically iterates through a predefined set of Cartesian positions generated by the optimization software and transforms each into a local coordinate system of the work object. For each position, the corresponding joint configuration is computed using inverse kinematics (CalcJointT), and the solution validity is stored in an array of reachability flags.

| Algorithm 1 Reachability and ISO Cube Evaluation Procedure |

|

If the configuration is feasible, the robot executes a predefined ISO cube trajectory at that location to evaluate the corresponding motion and energy consumption profile. Positions that cannot be reached are automatically flagged for later analysis. The procedure is executed in a fully automated loop, starting and ending from the robot’s home position, ensuring repeatability and minimizing operator intervention. As a result, infeasible configurations are detected programmatically and skipped during RAPID execution, allowing the validation to proceed continuously without simulation interruption or manual intervention.

The energy consumption data were recorded using the ABB Signal Analyzer tool integrated within the RobotStudio environment. This module captures instantaneous power and torque signals from all robot axes during trajectory execution. The recorded measurements were subsequently exported in CSV format, providing time-synchronized datasets suitable for post-processing and quantitative evaluation of total energy consumption, peak power, and trajectory efficiency in external analytical software.

For the selected motion speed v1000, the execution and energy evaluation of a single ISO Cube trajectory in RobotStudio required on average approximately 2.2 s per workspace position.

2.5. Real Workplace Verification

The experimental validation was carried out on the same ABB IRB 1600–10/1.2 industrial manipulator that was used in the simulations. The robot was equipped with a 2.8 kg custom end-effector and operated within a fully enclosed workstation.

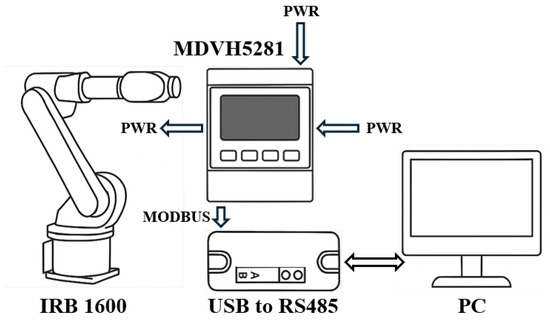

To ensure the accuracy of the energy measurements, two independent data acquisition systems were employed. Again, the Signal Analyzer was used to record data from the IRC5 controller. Second, a custom external measurement device was developed to verify and complement the controller-based data.

The external measurement system functions as an IoT-enabled sensing node, continuously streaming real-time electrical data via Modbus RTU. This device consisted of a three-phase multifunctional power analyzer Acean MDVH5281 (ACEAN SBE FRANCE, Saint-Martin-Boulogne, France) [20] connected to the robot’s power input and a Waveshare industrial USB-to-RS485 [21] converter that provides communication with a computer. The analyzer continuously transmitted measured electrical quantities (voltage, current, active power, and cumulative energy) via the Modbus RTU protocol. The acquisition software was implemented in Python 3.8 using the pymodbus library (see Algorithm 2). The sampling rate was approximately 1.8 Hz, and all data were stored in CSV format for post-processing. The measurement configuration is illustrated schematically in Figure 7. Each experiment was executed under identical trajectory and payload conditions as in the simulation.

| Algorithm 2 Energy Measurement and Data Logging Procedure |

|

Figure 7.

Configuration of the energy measurement setup showing power flow from the supply through the Acea MDVH5281 analyzer to the ABB IRB 1600 robot, and data flow to the host PC via RS485 communication.

3. Results

3.1. Simulation Results

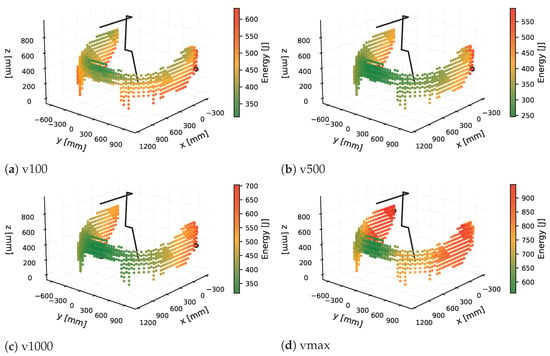

The simulation study was conducted to quantify how the spatial placement of a fixed ISO Cube trajectory influences the robot’s energy consumption. Four programmed speeds (v100, v500, v1000, and vmax) were evaluated, and each simulation measured the total motor energy required to complete a single ISO Cube cycle. The resulting values were visualized as three-dimensional energy distribution maps, enabling a direct comparison of energy demand across the evaluated workspace region.

The simulation dataset was constructed from the candidate workspace positions generated by the optimization software described in Section 2.3. In the first step, a pre-simulation filtering procedure (see Figure 5) removed most configurations that violated basic kinematic or reachability constraints, reducing the initial set to 794 positions. Although the robot kinematic parameters and collision volumes are defined in the custom software, this coarse filtering stage is intentionally conservative (i.e., tuned to avoid discarding potentially feasible configurations) and does not capture all robot and controller-specific execution constraints; therefore, a small subset of the filtered work object positions may still be infeasible for the real robot. The remaining positions were then validated in RobotStudio using the RAPID-based reachability and trajectory-check routine presented in Section 2.4 (Algorithm 1). Accordingly, 29 of the 794 filtered positions were rejected during this validation, and 765 positions were confirmed as feasible. Only positions for which the robot successfully completed the ISO Cube trajectory were included in the final dataset, all others were discarded. Each valid position therefore corresponds to one executed ISO Cube cycle and its associated energy value.

Energy measurements were obtained directly in ABB RobotStudio using the built-in Signal Analyzer tool. The TotalMotorEnergy [J] signal was used as the measure of energy consumption and represents the cumulative mechanical energy drawn by all robot joints during the executed motion. Only the part of the motion corresponding to the ISO Cube trajectory was evaluated; this segment was isolated using a dedicated digital marker to ensure consistent extraction of the relevant energy window across all simulated positions.

To assess whether the spatial energy distribution exhibits systematic differences across different motion conditions, the simulations were executed at four programmed speeds. The resulting three-dimensional energy maps for v100, v500, v1000, and vmax are shown in Figure 8. For each speed, the workspace position with the lowest energy and the position with the highest energy are marked using black circular indicators.

Figure 8.

3D energy distribution maps for the four programmed speeds (v100, v500, v1000, vmax). For each speed, the lowest-energy and highest-energy positions identified in the simulation dataset are marked with black circular indicators. A simplified wireframe representation of the ABB IRB 1600 robot is shown for reference to indicate the location of the evaluated positions within the workspace. The energy values correspond to the TotalMotorEnergy signal recorded over a single ISO Cube trajectory cycle.

A numerical summary of the simulation results is provided in Table 1. For each programmed speed, the table lists the best and worst workspace positions, the corresponding minimum and maximum TotalMotorEnergy values, and the relative difference between them.

Table 1.

Summary of simulation results for all programmed speeds.

The simulation results show distinct variations in energy consumption across different workspace positions for all tested speeds. Across all tested speeds, the energy maps show well-defined minimum and maximum values within the evaluated workspace region. The observed differences range from approximately 41% (vmax) to 58% (v500). Based on these findings, the speed v1000 was selected for the subsequent experimental verification as a practical compromise between sufficiently dynamic motion to reveal measurable configuration-dependent energy differences and a reasonable experiment duration given the limited availability of the industrial workstation.

3.2. Experimental Verification Results

Based on the simulation results presented in Section 3.1, two representative workspace configurations were selected for experimental verification: the position with the lowest simulated energy and the position with the highest simulated energy at speed v1000. These two configurations were used to assess whether the differences predicted by the simulation model persist under real operating conditions.

Importantly, absolute energy differences obtained in simulation and in real measurements are not expected to match quantitatively in all cases. This is primarily due to effects that are difficult to capture with high fidelity in an offline digital twin, including controller-dependent motion execution, drive and transmission losses, friction and temperature-dependent behavior, and energy recovery/regeneration. Consequently, simulation is used in this work to identify relative trends and candidate energy-efficient regions, whereas experimental validation is required to confirm practically achievable savings under real operating conditions.

Each configuration was tested in a sequence of 10,000 standardized trajectory cycles performed by the ABB IRB 1600–10/1.2 robot under identical operational conditions.

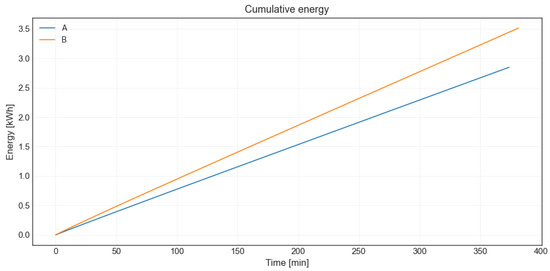

The experimental measurements confirmed the correctness and reliability of the optimization and data acquisition framework developed, as illustrated in the cumulative energy profiles shown in Figure 9.

Figure 9.

Cumulative energy consumption of the ABB IRB 1600–10/1.2 robot for the optimal (A) and non-optimal (B) workspace configurations.

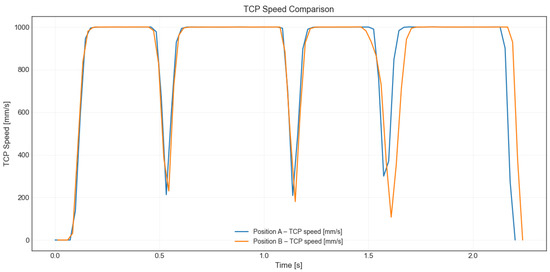

To clarify the difference in total measurement duration observed in Figure 9, the TCP speed profiles were analyzed for both configurations. As shown in Figure 10, the same programmed trajectory was executed in both cases; however, the robot temporarily reduced its TCP speed at several trajectory transitions in one of the configurations. These brief slowdowns reflect geometric effects along the trajectory, where some transitions are traversed slightly more slowly due to less favorable joint postures.

Figure 10.

TCP speed profiles recorded during one ISO Cube trajectory cycle for the two tested workspace configurations.

The measurement was conducted using the setup described in Section 2.5, which simultaneously recorded power data from the IRC5 controller and the external power analyzer. Table 2 summarizes the statistical parameters obtained from both datasets.

Table 2.

Summary of experimental results for the two workspace configurations.

It should be noted that the reported statistics are computed from the sampled long-term measurement series and are used for comparative energy assessment across configurations. The external measurement is intended to quantify long-term energy consumption and aggregate metrics.

The results clearly show a significant difference in the total energy consumption between the two configurations. The optimized (A) configuration consumed 2.849 kWh, while the non-optimal (B) configuration required 3.516 kWh for the same number of motion cycles, representing an increase of approximately 23.4%. Similarly, the mean electrical power increased from 457 W to 553 W and the mean current from 15.1 A to 17.3 A.

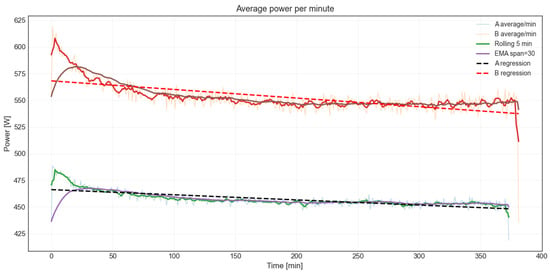

In addition to the differences in mean performance values, the detailed analysis of the time series revealed further distinctions in the operating behavior of the robot across the two configurations. Although the overall duration of both experiments was comparable, the robot remained in an active and energy-intensive state for a shorter proportion of time in configuration B (66%) than in configuration A (79%). This indicates that despite executing the same programmed trajectory for the same number of cycles, the motion in configuration B contained longer low-power intervals or less continuous execution. Nevertheless, during the periods in which the robot was actively moving, the configuration B consistently exhibited a higher electrical load, resulting in substantially elevated average power and cumulative energy (see Figure 11).

Figure 11.

Average power per minute for configurations A and B. Configuration B operates at a higher load throughout the entire experiment, while both measurements show a gradual decline in power due to thermal stabilization.

The higher current draw and power peaks—ranging from a maximum of 772 W in configuration A to 1055 W in configuration B—suggest that the robot experienced more dynamic or mechanically demanding motion when the trajectory was executed in the non-optimal region of the workspace. This interpretation is supported by the nearly threefold increase in the standard deviation of instantaneous power, indicating stronger oscillations and a more variable torque profile during movement.

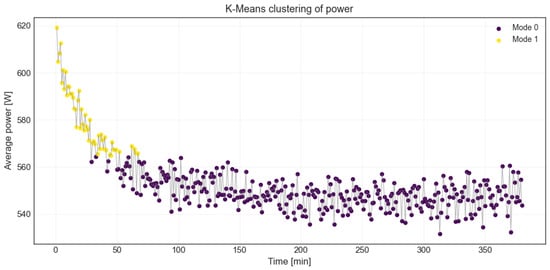

Long-term temporal trends were also consistent with this observation. Both measurements exhibited a mild negative power drift over time, commonly associated with thermal stabilization of the mechanical structure and drivetrain. However, Configuration B showed a more pronounced decline, reflecting its initial higher load and a more intensive warm-up phase (see Figure 12). Clustering of the power signal into operational regimes further confirmed these differences: while both configurations contained distinct warm-up and steady-state phases, configuration B reached its stable regime more rapidly but at considerably higher power levels, remaining energetically less efficient throughout the majority of the experiment.

Figure 12.

K-Means clustering of the average power signal for configuration B. Two distinct operating modes were identified: an initial high-power warm-up phase (Mode 1) followed by a lower and more stable operating regime (Mode 0).

Taken together, these results demonstrate that the spatial arrangement of the task within the robot’s workspace has a measurable influence on its energy behavior—not only in terms of total consumption but also with respect to instantaneous loading, dynamic variability, and the characteristics of individual operating phases. The experimentally observed differences between configurations A and B align closely with the simulation-based predictions, thus validating the effectiveness of the proposed automatic optimization method in identifying energy-efficient task placements in industrial robotic workstations.

4. Discussion

Q1: How does the proposed workspace optimization approach differ from traditional robot energy-saving methods?

Conventional approaches to robot energy optimization rely primarily on modifying trajectory parameters, reducing cycle time, or altering velocity and acceleration profiles. In contrast, the method proposed in this work preserves the technological trajectory entirely and instead optimizes only its spatial placement within the robot workspace. This separation between “what the robot does” and “where the robot performs the task” avoids unintended changes to the production process and demonstrates that significant energy savings can be achieved solely by geometric relocation. The experimental results confirm that identical trajectories executed at different positions may differ in energy consumption by more than 23%, highlighting the importance of spatial configuration as an independent optimization variable.

Q2: Why does shifting the trajectory within the workspace affect the robot’s electrical power consumption?

The electrical load of an industrial robot is directly linked to the joint torques required to compensate for gravity, inertia, friction, and dynamic coupling between axes. When the same trajectory is executed in different workspace locations, the robot may operate closer to joint limits, rely more heavily on stronger joints, or adopt less mechanically advantageous poses. This leads to increased motor currents and higher instantaneous power. The measured data support this: configuration B required higher mean current and higher peak power and exhibited nearly triple the power variance compared to configuration A. These findings confirm that even small spatial shifts of the task can substantially change torque demands and energy behavior.

Q3: Why was a constant robot velocity assumed, and how does this affect the applicability of the proposed method?

In industrial robotic applications such as gluing or sealing, a constant TCP velocity is commonly prescribed to ensure uniform process quality. The use of a constant programmed speed in this study therefore reflects standard industrial practice and enables a controlled comparison of different workspace configurations.

The proposed methodology is not inherently limited to constant-speed motions, as energy consumption is evaluated based on the actual executed motion in simulation or measurement. As a potential extension, future studies may investigate the combined optimization of workspace placement and robot speed, particularly with respect to the trade-off between energy consumption and the required workstation cycle time.

Q4: What is the significance of the observed warm-up and steady-state phases in the experimental data?

Both configurations exhibit a distinct high-power warm-up period followed by a lower and stable steady-state regime. This pattern reflects the thermal behavior of the robot’s actuators and drivetrain components, which require time to reach thermal equilibrium. Configuration B shows a shorter but more energy-intensive warm-up stage, indicating increased mechanical resistance at the beginning of the experiment. In addition, its steady-state power remains significantly higher throughout the measurement period. This behavior demonstrates that the energy penalty of non-optimal placement is not limited to transient operation but persists during continuous, long-duration tasks.

Q5: To what extent are the experimental findings generalizable across different robot models and manufacturing tasks?

Although the study is based on the ABB IRB 1600–10/1.2 executing the ISO 9283 trajectory, the underlying phenomenon is universal to serial manipulators: joint torques—and therefore electrical energy consumption—are strongly dependent on the geometric configuration. Any robotic cell in which the task trajectory is fixed but can be spatially repositioned (e.g., gluing, sealing, deburring, polishing, assembly) can benefit from the proposed method. The approach can be transferred to other robots by adapting only the kinematic model and workspace grid. The strong agreement between simulation and experiment also suggests that the method is suitable for integration into digital twin pipelines.

Q6: What do the results imply for energy-aware planning and smart manufacturing?

The demonstrated consistency between simulated and measured energy consumption confirms the validity of using virtual commissioning tools for predicting energy-optimal configurations. This capability is highly relevant in Industry 4.0 environments, where planning, optimization, and sustainability are increasingly integrated into automated workflows. By automatically identifying the most energy-efficient placement of a fixed trajectory, the proposed framework reduces operational costs, decreases thermal loading on actuators, and contributes to more sustainable manufacturing practices. These results also open the door to future extensions toward online, self-adaptive systems that adjust spatial configurations based on real-time energy measurements.

Q7: How can the presented framework support AI-based predictive or adaptive control?

The continuous measurement pipeline and structured simulation dataset provide a foundation for supervised learning models that can predict energy consumption for unseen workspace configurations. This data set can further support reinforcement learning or model-predictive schemes in which the robot autonomously adapts its spatial configuration to minimize energy use under varying production conditions.

Q8: How can energy-efficient workspace configurations be identified in industrial practice without exhaustive simulation?

The presented methodology should currently be understood primarily as a conceptual, research-level framework that demonstrates the influence of spatial configuration on robot energy consumption. Exhaustive simulation of all possible workspace placements would therefore be impractical in real industrial environments.

In practical deployments, such optimization would require automation through software support, for example in the form of an optimization add-on integrated into robot programming environments or as a standalone application. By combining kinematic pre-filtering with automated simulation or data-driven surrogate models, energy-efficient workspace regions could be identified without evaluating every configuration individually. The results of this study provide a quantitative basis for the future development of such industrial optimization tools.

5. Conclusions

This paper introduced an automatic optimization framework to reduce energy consumption in industrial robotic workstations by identifying the most energy-efficient spatial placement of a fixed trajectory within the robot’s workspace. Unlike conventional energy optimization techniques that modify the robot’s motion parameters or trajectory geometry, the proposed method preserves the original technological path and optimizes only its position relative to the robot base. This conceptually simple yet powerful approach enables significant energy savings without compromising task integrity or process repeatability.

The developed workflow integrates pre-simulation filtering of infeasible configurations, large-scale digital twin simulations in ABB RobotStudio, and experimental validation using a dual acquisition system combining controller-based and external measurements. The simulation study demonstrates that workspace placement can substantially affect the energy demand of a fixed industrial robot trajectory and provides a systematic way to identify energy-efficient regions within the evaluated workspace. The experimental verification confirms that relocating the same trajectory can yield a 23.4% reduction in total energy consumption under real operating conditions, supporting the practical relevance of the proposed approach. The results clearly demonstrate that even small spatial changes in the same trajectory can lead to substantial changes in energy demand. Both simulations and real measurements on the ABB IRB 1600–10/1.2 robot confirmed a difference that exceeded 23% in total energy consumption between optimal and non-optimal workspace configurations. The non-optimal configuration exhibited higher mean current, increased peak power, and a more intensive warm-up phase, confirming that geometric placement alone has a measurable and repeatable impact on energy performance.

The strong correlation between simulation and experimental results validates the effectiveness of the proposed approach and its suitability for integration into digital twin environments. The presented methodology provides a practical and scalable tool for improving the sustainability of industrial robotics. By embedding this optimization routine into robot cell design and planning workflows, manufacturers can systematically identify energy-efficient configurations, reduce operating costs, and align robotic automation with the principles of Industry 4.0 and sustainable manufacturing.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.W. and J.K.; methodology, R.W.; software, J.K. and T.K.; validation, R.W., J.K. and J.B.; formal analysis, J.B.; investigation, T.K.; resources, R.W. and J.K.; data curation, R.W. and J.K.; writing—original draft preparation, R.W. and J.K.; writing—review and editing, R.W. and J.K.; visualization, R.W., J.K., and T.K.; supervision, R.W.; project administration, V.K.; funding acquisition, Z.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded in part by by the European Union under the REFRESH—Research Excellence For REgion Sustainability and High-tech Industries project number CZ.10.03.01/00/22_003/0000048 via the Operational Programme Just Transition. This article was also supported by specific research project SP2025/042 and financed by the state budget of the Czech Republic.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data that supports the findings of this article is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this work the authors used ChatGPT 5.1 and DeepL (free version) in order to improve language and readability. After using this tool/service, the authors reviewed and edited the content as needed and take full responsibility for the content of the publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| CSV | Comma-Separated Values |

| Hz | Hertz |

| IoT | Internet of Things |

| ISO | International Organization for Standardization |

| kWh | Kilowatt-Hour |

| PC | Personal Computer |

| RNN | Recurrent Neural Network |

| RTU | Remote Terminal Unit |

References

- Verma, N.; Sharma, V.; Badar, M.A. Entropy-based lean, energy and six sigma approach to achieve sustainability in manufacturing system. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 2021, 46, 8105–8117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dinçer, I.; Acar, C. A review on clean energy solutions for better sustainability. Int. J. Energy Res. 2015, 39, 585–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rachuri, S.; Jain, S. Maturity Model Concepts for Sustainable Manufacturing; National Institute of Standards and Technology: Gaithersburg, MA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madan, J.; Mani, M.; Lyons, K.W. Characterizing energy consumption of the injection molding process. In Proceedings of the 2013 International Manufacturing Science and Engineering Conference, Madison, WI, USA, 10–14 June 2013; Volume 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.B.; Shao, G.; Brodsky, A.; Consylman, R. Sustainable process analytics formalism: A case study of book binding system for energy optimization. In Proceedings of the ASME 2013 International Design Engineering Technical Conferences and Computers and Information in Engineering Conference, Portland, OR, USA, 4–7 August 2013; Volume 2A. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chun, Y.; Bidanda, B. Sustainable manufacturing and the role of theinternational journal of production research. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2013, 51, 7448–7455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zhang, G.; Cao, H.; Hu, K.; Wang, Q.; Deng, Y.; Gao, J.; Tang, Y. Geometry-Aware 3D Point Cloud Learning for Precise Cutting-Point Detection in Unstructured Field Environments. J. Field Robot. 2025, 42, 3063–3076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heredia, J.; Kirschner, R.J.; Schlette, C.; Abdolshah, S.; Haddadin, S.; Kjægaard, M.B. Ecdp: Energy consumption disaggregation pipeline for energy optimization in lightweight robots. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2023, 8, 6107–6114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torayev, A.; Martínez-Arellano, G.; Chaplin, J.C.; Sanderson, D.; Ratchev, S. Online and modular energy consumption optimization of industrial robots. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2024, 20, 1198–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ružarovský, R.; Horák, T.; Bočák, R.; Csekei, M.; Zelník, R. Integrating energy and time efficiency in robotic manufacturing cell design: A methodology for optimizing workplace layout. Machines 2025, 13, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ružarovský, R.; Horák, T.; Bočák, R. Evaluating energy efficiency and optimal positioning of industrial robots in sustainable manufacturing. J. Manuf. Mater. Process. 2024, 8, 276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Sosa, R.; Chavero-Navarrete, E. Robotic cell layout optimization using a genetic algorithm. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 8605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muru, J.; Rassõlkin, A. A scoping review of energy consumption in industrial robotics. Machines 2025, 13, 542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Han, G.; Wei, Z.; Huang, Z.; Chen, X.; Wu, J. Optimal trajectory planning of robot energy consumption based on improved sparrow search algorithm. Meas. Control 2024, 57, 1014–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peta, K.; Suszyński, M.; Wiśniewski, M.; Mitek, M. Analysis of energy consumption of robotic welding stations. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ABB Robotics. RobotStudio—Offline Programming and Simulation Software, 2025. Available online: https://new.abb.com/products/robotics/software-a-digital/robotstudio (accessed on 4 November 2025).

- ABB Robotics. ABB IRB 1600 Industrial Robot, 2025. Available online: https://www.abb.com/global/en/areas/robotics/products/robots/articulated-robots/medium-robots/irb-1600 (accessed on 7 October 2025).

- ABB Robotics. IRC5 Single Controller, 2025. Available online: https://www.abb.com/global/en/areas/robotics#tabbedcontainer-8bb3cc5e3f-item-47f0f37e25-tab (accessed on 4 November 2025).

- ISO 9283; Manipulating Industrial Robots—Performance Criteria and Related Test Methods. ISO (International Organization for Standardization): Geneva, Switzerland, 1998.

- INEPRO Metering BV. MDVH5281—M-Bus elektroměr: Quick Start Guide (CZ). INEPRO Metering BV, 2021. Available online: https://www.elektromery.com/files/prod_files/mdvh5281_qs_cz_mbus.pdf (accessed on 4 November 2025).

- Waveshare Electronics. USB to RS485 Converter, 2025. Available online: https://www.waveshare.com/usb-to-rs485.htm (accessed on 4 November 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.