Abstract

The integration of artificial intelligence (AI) into intelligent control systems has advanced significantly, enabling improved adaptability, robustness, and performance in nonlinear and uncertain environments. This study conducts a PRISMA-2020-compliant systematic mapping of 188 peer-reviewed articles published between 2000 and 15 January 2025, identified through fully documented Boolean queries across IEEE Xplore, ScienceDirect, SpringerLink, Wiley, and Google Scholar. The screening process applied predefined inclusion–exclusion criteria, deduplication rules, and dual independent review, yielding an inter-rater agreement of κ = 0.87. The resulting synthesis reveals three dominant research directions: (i) control model strategies (36.2%), (ii) parameter optimization methods (45.2%), and (iii) adaptability mechanisms (18.6%). The most frequently adopted approaches include fuzzy logic structures, hybrid neuro-fuzzy controllers, artificial neural networks, evolutionary and swarm-based metaheuristics, model predictive control, and emerging deep reinforcement learning frameworks. Although many studies report enhanced accuracy, disturbance rejection, and energy efficiency, the analysis identifies persistent limitations, including overreliance on simulations, inconsistent reporting of hyperparameters, limited real-world validation, and heterogeneous evaluation criteria. This review consolidates current AI-enabled control technologies, compares methodological trade-offs, and highlights application-specific outcomes across renewable energy, robotics, agriculture, and industrial processes. It also delineates key research gaps related to reproducibility, scalability, computational constraints, and the need for standardized experimental benchmarks. The results aim to provide a rigorous and reproducible foundation for guiding future research and the development of next-generation intelligent control systems.

1. Introduction

Intelligent control systems have evolved substantially in recent decades as industrial processes have become increasingly complex, nonlinear, and subject to uncertainty. Traditional control techniques, while effective in well-defined operating conditions, often struggle in environments characterized by rapid variability, incomplete models, and multivariable interactions. In parallel, advances in artificial intelligence (AI), including fuzzy logic, neural networks, evolutionary computation, and machine learning, have led to new approaches capable of learning from data, adapting to disturbances, and handling complexity beyond the reach of conventional controllers.

Historical developments show a progressive convergence between AI and control theory. Initial AI-inspired methods such as fuzzy inference and early neural models complemented classical PID and state-space control. More recent approaches incorporate hybrid neuro-fuzzy systems, metaheuristic optimization, predictive control architectures, and deep reinforcement learning, significantly expanding the toolbox available for intelligent control design. As a result, the integration of AI-based techniques has become a central research direction for improving robustness, adaptability, fault tolerance, and performance in applications such as renewable energy systems, industrial automation, robotics, power grids, and autonomous systems.

Despite the growing volume of publications in this domain, the existing literature reviews exhibit several limitations. Most lack reproducible methodologies, do not explicitly report Boolean search strategies, and rarely follow PRISMA-2020 guidelines. Many analyses focus on specific techniques—such as fuzzy systems, optimization algorithms, or predictive control—without offering a unified classification or mapping of the field. Furthermore, prior reviews generally do not compare methodological trade-offs among AI-enabled controllers, nor do they assess practical implications such as computational cost, scalability, real-time feasibility, or robustness under industrial conditions. Emerging contributions, including deep reinforcement learning, hybrid metaheuristics, or adaptive neuro-fuzzy architectures, are inconsistently integrated into broader trends.

Research Gap:

The current literature lacks the following:

(1) A standardized, PRISMA-2020-aligned synthesis of intelligent control systems.

(2) A unified taxonomy covering control models, optimization strategies, and adaptive mechanisms.

(3) Comparative analyses addressing real-world trade-offs, scalability, computational constraints, and industrial feasibility.

(4) Integration of emerging hybrid and deep learning-based controllers within the evolution of the field.

(5) Discussion of reproducibility challenges, including incomplete hyperparameter reporting and limited experimental validation.

Objective of This Review:

This study addresses these gaps by providing a systematic mapping of 188 peer-reviewed articles published between 2000 and 15 January 2025. This review employs explicit Boolean queries across multiple databases, dual screening with inter-rater agreement, deduplication procedures, and PRISMA-2020-aligned documentation of the study-selection flow and checklist. It offers a structured classification of intelligent control systems into three main contribution areas, i.e., control model strategies, optimization techniques, and adaptability mechanisms, while integrating emerging approaches such as deep reinforcement learning and hybrid metaheuristics. The analysis provides methodological comparisons, domain-specific insights, and a consolidated overview of challenges and future research directions.

The remainder of this article is organized as follows. Section 2 describes the PRISMA-2020 methodology and search protocol. Section 3 presents systematic mapping results, taxonomy, and comparative analysis. Section 4 discusses trends, practical implications, research opportunities, and limitations. Section 5 concludes with key findings and recommendations for advancing intelligent control systems.

2. Methodology

2.1. Review Design and Reproducibility

This work is designed as a systematic mapping study of AI-based intelligent control systems and follows the PRISMA-2020 recommendations for transparent reporting of systematic mapping. The review process included database selection, construction of Boolean search queries, deduplication, screening by two independent reviewers, eligibility assessment, extraction using a structured form, and synthesis and classification, with a cut-off date of 15 January 2025 for all database searches.

All papers included were published between 2000 and 2025, including early-access and online-first articles. Their status is explicitly indicated in the reference list, Table 1.

Table 1.

Databases and full Boolean search strings used in this review.

2.2. Databases and Full Boolean Search Strings

2.3. Search Execution, Deduplication, and Screening Process

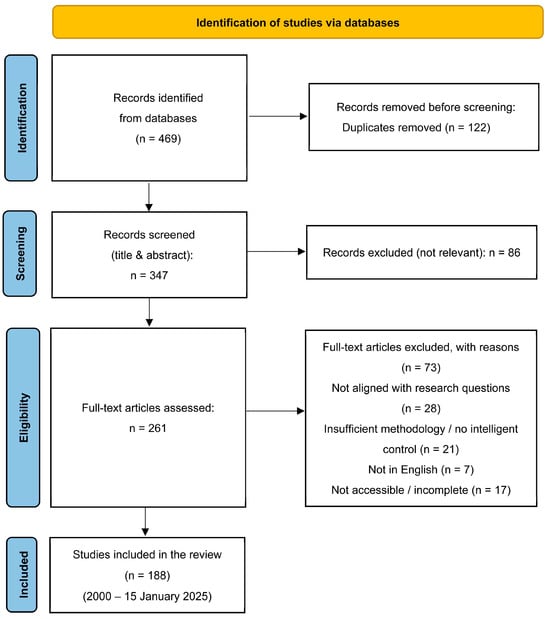

The initial search returned 469 records. Deduplication was performed using Zotero automatic duplicate detection, manual verification of title/DOI, and independent screening by two reviewers. After deduplication, 347 unique records remained. Two independent screeners (Author 1 and Author 2) evaluated all records; conflicts were resolved by discussion, and, when disagreement persisted, a third reviewer resolved the case. The inter-rater agreement was κ = 0.87, indicating strong agreement.

2.4. Inclusion, Exclusion, and Selection Criteria (Standardized Labels)

Inclusion Criteria (ICs):

IC-1: Terms related to intelligent control appear in title or abstract.

IC-2: Publication year between 2000 and 15 January 2025.

IC-3: The study addresses control problems aligned with research questions.

IC-4: The study includes control engineering implementation.

IC-5: Focus on intelligent strategies: fuzzy, ANN, ML, metaheuristics, MPC-hybrid, and hybrid.

IC-6: The study includes evaluation (case study, experiment, simulation, review, survey).

Exclusion Criteria (ECs):

EC-1: Published before 2000.

EC-2: High-level general control discussions with no intelligent methods.

EC-3: Non-research formats (editorials, patents, letters).

EC-4: Studies not written in English.

EC-5: Not related to intelligent controllers.

Selection Criteria (SCs):

SC-1: Apply IC/EC to title and abstract.

SC-2: Read introduction and conclusion to verify alignment.

SC-3: Full-text reading of remaining articles.

SC-4: Classification into one dominant contribution category (mutually exclusive).

SC-5: Papers may map to multiple structures, but classification uses the main contribution only.

2.5. PRISMA-2020 Flow Diagram

The study selection process was documented using the PRISMA-2020 flow diagram. Figure 1 summarizes the flow from 469 identified records to the final set of 188 included studies.

Figure 1.

PRISMA-2020 flow diagram for study selection (source: own elaboration based on systematic mapping).

2.6. Data Extraction

A structured extraction form captured the following:

- Year, authors, and publication type.

- Control structure.

- Intelligent techniques (fuzzy, ANN, ML, MPC, evolutionary, hybrid).

- Optimization method.

- Application domain.

- Type of evaluation (simulation, experiment).

- Reported metrics.

2.7. Research Questions

The research questions guiding this systematic mapping were reorganized into three conceptual categories to improve clarity and better reflect the analytical structure of the study. Each category addresses a specific dimension of intelligent control systems and supports the objectives of systematic mapping.

Category 1: Publication Sources

This category identifies where the scientific community is publishing intelligent control research and helps determine the concentration of knowledge in journals, conferences, and publishers.

Q1. What are the primary publication sources reporting advances in intelligent control systems?

Category 2: Technologies, Methods, and Architectures

This group focuses on the technical core of the review and examines how intelligent control systems are designed, implemented, and optimized. These questions explore the engineering contributions, computational techniques, and the structural features of controllers.

Q2. What types of engineering contributions and applications are reported in the development of intelligent control systems?

Q3. What research approaches and study types characterize intelligent controller designs?

Q4. What control structures and techniques define intelligent control systems in the recent literature?

Q5. Which computational tools and algorithms are most frequently used for the development of intelligent control systems?

Category 3: Trends, Challenges, and Future Directions

This category provides a forward-looking analysis by assessing emerging patterns, unresolved issues, and research opportunities in the field.

Q6. What are the current research trends in intelligent control?

Q7. What challenges and research opportunities remain open for the advancement of intelligent control systems?

Motivation for Research Questions

These seven questions were designed to achieve the following:

- Map the scientific landscape (Q1), identifying dominant publishers, journals, and dissemination channels.

- Characterize the technical evolution of intelligent control (Q2, Q3, Q4, Q5) by examining control structures, AI-driven algorithms, and hybrid architectures.

- Identify trends and gaps in intelligent control research (Q6, Q7), drawing insights into emerging techniques, scalability issues, reproducibility challenges, and future research needs in academic and industrial contexts.

Together, these research questions establish a comprehensive framework for analyzing the state of AI-based intelligent control and ensuring that the systematic mapping captures both technical and methodological perspectives.

2.8. Classification Rules

Classification rules were defined as follows: Tables within Section 3.5.1–Section 3.5.3 include per-node counts (n). Multi-label assignments are allowed at the node level; however, each article is assigned to one dominant contribution category when computing global percentages.

3. Results

From identifying sources of publications on intelligent controllers to assessing research trends and methodological approaches used in this field, this comprehensive analysis provides a detailed view of the current landscape. We analyze the most reported computational tools and algorithms in the literature for the design of these controllers.

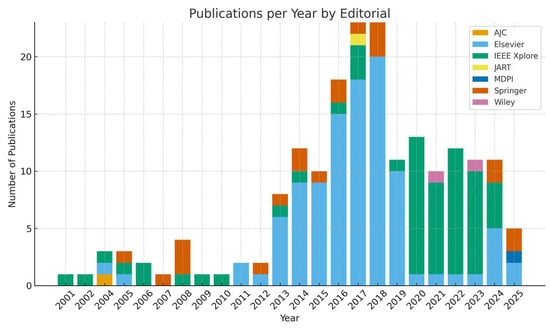

3.1. Publication Sources

To complement the global distribution of publishers, Figure 2 shows the temporal evolution of the publication venues where AI-based intelligent control systems have been reported between 2001 and 2025. The stacked bars represent, for each year, the number of articles and conference papers indexed by the main editorial ecosystems, including Elsevier, IEEE Xplore, Springer, Wiley, AJC, JART, and MDPI. This view highlights not only the dominance of Elsevier and IEEE Xplore over the entire period, but also the progressive diversification of publication outlets in recent years, with an increasing presence of Springer proceedings and isolated yet relevant contributions in Wiley, AJC, JART, and MDPI journals and conferences. Overall, the figure confirms that research on AI-enabled intelligent control has intensified and broadened its editorial base, particularly after 2010, following the consolidation of hybrid, learning-based, and optimization-driven control strategies.

Figure 2.

Number of publications per year is grouped by publisher (source: own elaboration based on systematic mapping).

Table A4 in Appendix D summarizes the main journals and conference proceedings where the included studies were published, ordered by the number of contributions per venue. IFAC and Applied Soft Computing appear as the most frequent outlets, followed by ISA Transactions, Neurocomputing, and Energy Procedia, confirming the strong presence of AI-based intelligent control research in both control engineering and soft computing communities.

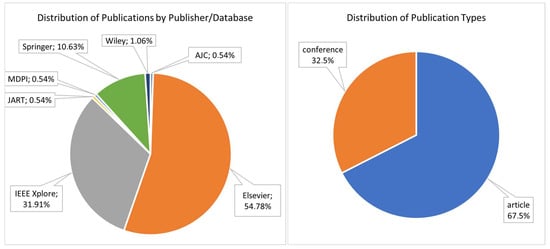

The sources of intelligent controller publications reveal a marked predominance of a small group of publishers. Elsevier is the most prominent, representing 54.78% of the 188 articles included in this review, followed by IEEE with 31.91% and Springer with 10.63%. Wiley accounts for 1.06% of the total. MDPI, AJC, and JART each contribute a single article, i.e., 0.54% per venue, together representing about 1.62% of all publications. Percentages are computed over the full set of 188 peer-reviewed articles, each assigned to a single publisher, pooling journal, and conference contributions. This distribution indicates that research on AI-based intelligent controllers is strongly concentrated within a limited set of editorial ecosystems, with Elsevier and IEEE playing a central role in disseminating advances in this area.

We found that the journals published 67.5% of the reviewed articles. Specialized intelligent controller conferences presented the remaining 32.5%. These figures highlight publishers’ significant role in disseminating scientific articles in this domain. Figure 3 summarizes these values.

Figure 3.

Distribution of 188 included articles across publisher’s databases and type of publication (source: own elaboration based on systematic mapping).

3.2. Engineering Contributions and Applications in Intelligent Controllers

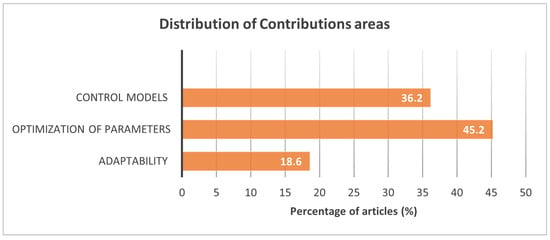

The review of research types has enabled us to identify and distill three primary areas of contributions in the field of engineering. Firstly, the contribution related to control model strategies stands out, representing 36.2% of the total, which encompasses the development and improvement of new intelligent algorithms for controllers, whether intelligent or conventional, as well as the introduction of new control structures with intelligent algorithms. The category of optimization models constitutes 45.2%, distinguishing itself through the presentation of new intelligent optimization models and the integration of artificial intelligence techniques with other conventional or intelligent ones.

Finally, the contribution of adaptability, with 18.6%, focuses on developing intelligent controllers that exhibit adaptability in their structure to provide control with high-speed response, robustness, and other qualities. These results provide a comprehensive overview of the various engineering contributions and applications in the field of intelligent controllers. Figure 4 presents a summary of the total number of articles according to the contribution made to intelligent controllers.

Figure 4.

Distribution of contribution areas in the reviewed studies (source: own elaboration based on systematic mapping).

3.3. Structures and Techniques in Intelligent Controllers

Intelligent controllers use diverse control structures and techniques to optimize efficiency and adaptability across various systems. Artificial neural networks are among the most common structures; they excel at modeling nonlinear behaviors and learning complex patterns. Fuzzy logic and its ability to handle uncertainty offer a crucial option in dynamic environments.

Many specific techniques use meta-heuristics such as particle swarm optimization (PSO) and genetic algorithms (GAs) to fine-tune controller parameters for better performance. Predictive control is particularly good at anticipating and managing changes in a system’s dynamics. Multilayer neural networks (MNNs) have adaptable structures that can model complex systems and learn from data. The adaptive fuzzy tracking algorithm-based control adaptive fuzzy tracking algorithm-based control and fuzzy MIMO control prove how fuzzy logic can adapt to many inputs and outputs in complex systems. In e-learning, dynamic parameter adjustment and grammatical evolution are effective strategies. These techniques show how control engineering is moving toward more adaptable solutions, combining fundamental principles with AI strategies to tackle modern system complexities.

3.4. Most Reported Computational Tools and Algorithms

The results of this study offer information on preferences and trends in algorithms and control structures. This comes from an analysis of scientific articles published from 2000 to early 2025. The most common classifications found are as follows:

- Artificial neural networks: 9.7%;

- Evolutionary or optimization algorithms: 15.0%;

- Fuzzy logic: 19.4%;

- Hybrid methods: 26.6%;

- Iterative learning control: 4.1%;

- Internal model control: 3.1%;

- Machine learning: 1.8%;

- Metaheuristic optimization: 11.4%;

- Model predictive control: 6.0%;

- Others: 2.9%.

Artificial neural networks (ANNs) are widely used in intelligent control due to their ability to approximate nonlinear system dynamics and adapt their internal weights based on error signals. Their layered structure enables learning-based modeling and control without requiring explicit analytical equations, making them effective for processes with significant uncertainty or nonlinearities. ANNs are commonly applied for system identification, predictive modeling, and adaptive control in complex industrial environments [1,2,3].

Evolutionary algorithms (EAs) provide a robust global search mechanism for tuning controller parameters, optimizing rule bases, and solving high-dimensional nonlinear optimization problems. By relying on population-based operators such as selection, crossover, mutation, and survival strategies, EAs efficiently explore complex search spaces where gradient-based methods fail. Common variants such as genetic algorithms, evolution strategies, and genetic programming are widely used for controller tuning, hybrid fuzzy–neural design, and multi-objective optimization in intelligent control [4,5,6].

Fuzzy logic (FL) enables the incorporation of expert knowledge into control systems through rule-based reasoning, handling nonlinear behaviors and uncertainty without requiring mathematical plant models. Its use of graded membership functions and linguistic rules allows smooth decision making in noisy or imprecise environments. FL is widely applied in industrial control, pattern recognition, decision systems, and medical diagnostics due to its interpretability and robustness [7,8,9].

Hybrid methods combine complementary intelligent techniques such as FL with neural networks or evolutionary algorithms to enhance robustness, accuracy, and adaptability. These architectures exploit the strengths of each component, such as neural learning with fuzzy interpretability or evolutionary global search with local refinement. Hybrid solutions are effective in complex control applications, including robotics, mechatronics, economic forecasting, and large-scale optimization [10,11,12].

Iterative learning control (ILC) improves control performance in repetitive operations by refining control actions based on previous execution errors. Through trial-by-trial updates, ILC enhances trajectory tracking and accuracy, making it suitable for robotics, automated manufacturing, additive manufacturing, and precision motion systems. Its learning mechanism allows continuous improvement without requiring explicit model updates [13,14,15].

Internal model control (IMC) employs a model of the plant to predict disturbances and generate corrective actions, resulting in a control strategy that is robust to model uncertainty and external perturbations. IMC’s predictive capability is particularly suitable for chemical processes, thermal systems, and manufacturing environments where disturbances are frequent, and constraints must be respected [16,17,18].

Machine learning (ML) enhances intelligent control by enabling systems to extract patterns from operational data, adapt to changing conditions, and support predictive decision making. ML techniques, i.e., supervised, unsupervised, and reinforcement learning, are used for fault detection, anomaly identification, controller parameter tuning, and modeling complex nonlinear systems in finance, healthcare, autonomous systems, and industrial automation [1,19,20,21].

Metaheuristic optimization (MO) offers a flexible framework for approximating solutions to nonlinear, multidimensional optimization problems where analytical approaches fail. Algorithms inspired by biological and physical processes such as PSO, GWO, ACO, DE, and simulated annealing are widely applied for controller tuning, membership-function optimization, and parameter identification. Their exploration–exploitation balance provides improved global performance in engineering, logistics, bioinformatics, and industrial control [10,22,23,24].

Model predictive control (MPC) optimizes control actions by predicting system behavior over a finite horizon and enforcing constraints in real time. MPC is particularly effective for multivariable and constraint-bound industrial processes, including energy systems, autonomous vehicles, and chemical production. Its integration with ANN or FL models further improves performance under nonlinear or time-varying conditions [25,26,27,28].

3.5. Outcomes of Studies

Appendix A, Appendix B and Appendix C presents a classification of the analyzed 188 articles, specifying the type and focus of research that categorizes them into one of these three topics: the control model, the implementation of techniques for parameter optimization, and adaptive controllers. In addition, the classification is based on the type of contribution, exploring various contributions and engineering applications derived from advances in intelligent controllers, including contributions related to control, optimization, and adaptability models. In addition, the structures and control techniques used to specify and design intelligent controllers are analyzed, encompassing both classical and modern control structures, as well as the artificial intelligence techniques employed, such as neural networks, fuzzy logic, and evolutionary algorithms. Finally, the most widely used computational algorithms in the literature are those for designing and implementing controllers that enhance the efficiency and performance of intelligent controllers in various applications and scenarios.

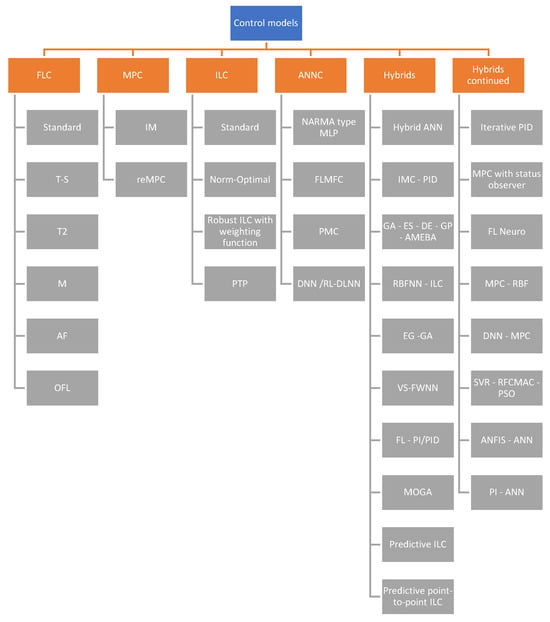

3.5.1. Result of Contributions: Control Models

The integration of AI techniques into intelligent controllers represents a significant advance in the field of control systems. These new control models combine conventional methods with AI approaches to improve adaptability, accuracy, and efficiency in complex and variable environments. This combination enables the handling of challenges ranging from variability in operating conditions to unforeseen disturbances, opening opportunities to optimize and continuously improve system performance. The reviewed articles present relevant contributions across several categories of intelligent control models, including hybrid controllers, fuzzy logic controllers, predictive controllers, iterative learning controllers, and neural controllers.

Hybrid controllers combine two or more control techniques or algorithms to leverage their strengths and compensate for their weaknesses. They are increasingly popular in industrial, energy, and complex system applications, particularly in contexts involving AI, optimization, and classical control. The reviewed literature reveals advanced control and optimization strategies applied to dynamic, nonlinear, and complex systems. Several works propose hybrid methods that merge techniques such as artificial neural networks (ANNs) and fuzzy logic (FL), often supported by evolutionary algorithms (EAs) for improved model identification, controller design, tuning, and robustness against uncertainties and perturbations. Various architectures integrate ANNs with type-1, type-2, or fractional fuzzy logic for control and compensation tasks in nonlinear and uncertain environments ([29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39]). Additionally, numerous studies employ genetic algorithms, differential evolution, evolutionary strategies, particle swarm optimization, harmony search, cuckoo search, and related heuristics to optimize strategies, parameters, and rule sets in hybrid controllers ([37,38,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49]). Other papers incorporate model predictive control (MPC), frequently combined with ANNs or fuzzy logic to accelerate computations or enhance tracking and robustness ([50,51,52,53,54,55,56]). Hybrid schemes that integrate classical control techniques (PI, PID, H∞, deadbeat, sliding mode control) with intelligent components (ANN, FL) demonstrate improved accuracy, adaptability, and robustness, even in systems with incomplete models or operating under changing conditions ([45,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64]). These approaches are validated in real or simulated systems—including power plants, turbines, robots, chemical processes, hybrid energy systems, irrigation systems, and autonomous vehicles—showing enhanced performance, reduced error, increased robustness, and improved energy efficiency compared to traditional controllers ([45,48,49,52,59,63]).

Fuzzy logic controllers (FLCs) have proven highly effective due to their ability to handle uncertainty and their adaptability to variable operating conditions. Based on IF–THEN rules and fuzzy sets, these controllers are well suited for environments with frequent disturbances or dynamically changing parameters. A Takagi–Sugeno incremental fuzzy state model improves stability and error rejection by integrating an FLC–LQR structure with an optimal observer [65]. In automotive applications, comparisons between PID and fuzzy logic controllers for vehicle stability show that fuzzy logic offers superior robustness, though PID remains easier to implement [66]. In power electronics, a type-2 fuzzy neural controller (T2FNS) outperforms a conventional PI controller in terms of speed, overshoot, and power quality for converter control [67], while a fuzzy controller for DC–DC converters achieve faster responses and better disturbance rejection than traditional PI controllers [68]. In water treatment, a Mamdani FLC achieves greater pH stability and contaminant reduction where classical PIDs fail [39], and in electric motor applications, a Mamdani FLC provides improved tracking and robustness under disturbances compared to PID [69]. In renewable energy, an adaptive FLC enhances wind energy extraction with better dynamic performance than PI control [70], while in agriculture, an efficient FLC regulates greenhouse temperature and humidity with high accuracy under real conditions [71]. For photovoltaic systems, an optimized MPPT fuzzy controller offers faster convergence, improved accuracy, and reduced steady-state oscillations. References [72,73] present the design and experimental validation of a Mamdani-type fuzzy PI controller for liquid-level regulation in an industrial training plant (Festo Didactic MPS® PA Compact Workstation), and the plant is first identified in MATLAB R2022 using the System Identification toolbox, achieving a transfer function model with 98.45% fit and a fuzzy PI controller with five membership functions per input, and a rule base derived from operator knowledge is designed and compared against two PID controllers: one tuned automatically with MATLAB’s PID Tuner and another tuned manually by an experienced operator; simulation results under reference changes and disturbances show that the fuzzy PI achieves faster settling time and better disturbance rejection than both PID configurations, the controller is then implemented on the real plant and tested with different reference profiles (step, ramp, sinusoidal, sawtooth, and square inputs), and quantitative performance indices (mean error, mean absolute error, mean square error, and root mean square error) confirm that the fuzzy PI consistently attains slightly lower tracking errors than the PID controller while preserving stability and robustness. Finally, [74] presents the design and implementation of a fuzzy–Smith compensator for speed control of an induction motor driven by a frequency converter in a networked control system architecture based on Siemens S7-1200 PLCs and PROFINET communication, the plant is first identified in MATLAB, obtaining a first-order model with 96% fit, and a Mamdani fuzzy controller is designed using error and error derivative as inputs, with seven triangular membership functions and 49 rules, to adapt the gain of the Smith predictor and compensate modeling errors and network-induced delays; in simulation, the fuzzy–Smith compensator is compared against two PI/PID controllers (one auto-tuned in MATLAB and one tuned by an experienced operator), showing similar or faster responses with reduced overshoot. Experimental tests on a 1 HP induction motor training kit confirm that the MATLAB-tuned PID becomes oscillatory, while the operator-tuned PID and the fuzzy–Smith compensator remain stable; the fuzzy compensator halves the rise time (2 s vs. 4 s) and maintains overshoot below 5%, achieving the lowest mean, absolute, and root-mean-square tracking errors among all controllers.

Model-based predictive controllers (MPCs) estimate future system outputs through internal models and continuously adjust control actions, making them ideal for scenarios requiring anticipatory behavior. A detailed review of MPC applications in agriculture covers classical, robust, nonlinear, distributed, and stochastic variants, with successful implementations in irrigation, machinery, production, and greenhouse climate control [75]. This review highlights MPC’s superiority over traditional and AI-based controllers in managing multivariable, time-delayed, and nonlinear systems, while acknowledging existing challenges in real-world agricultural applications. A Robust Economic Predictive Control (reMPC) method incorporates stochastic perturbation information for time-invariant linear systems using a tube-based formulation to maintain feasibility and robustness [76]. This method leverages known fault distributions to optimize performance and terminal costs, and its validation in a CSTR reactor demonstrates its advantages over conventional robust MPC approaches.

Iterative learning controllers (ILCs) are effective in applications involving repetitive tasks requiring high precision. These controllers refine the control input based on error information from previous iterations, progressively improving tracking accuracy. A comparison of three Norm-Optimal ILC schemes—standard quadratic ILC (QILC), integrated-estimation ILC (E-QILC), and iteration-domain Kalman ILC (K-ILC)—reveals that while the methods are equivalent under certain conditions, the K-ILC approach offers superior convergence speed and robustness to noise [77], validated through simulations on a mass–spring–damper system. Another robust ILC formulation incorporates performance weighting functions to ensure convergence under plant uncertainty, also validated through simulation studies [78].

Neural controllers (ANNCs) leverage artificial neural networks to learn and adapt to varying conditions by adjusting their internal weights, making them suitable for nonlinear and complex systems. A comprehensive review highlights that data-driven models can replace or complement classical elements within control loops [55], supported by a case study showing that a deep neural network improves autonomous surface vehicle performance and resilience to modeling errors compared to conventional linearizing controllers. Another contribution proposes a robust predictive control scheme using ANNCs in a dual-stage structure—one for plant modeling and one for residual uncertainty—achieving stability and improved robustness in a pneumatic servomechanism validated experimentally [79]. The learning feedback linearization (LFL) approach employs a NARMA-type MLP neural network to learn nonlinear system inverse dynamics, enabling subsequent PI control with successful simulation results [80]. Another controller based on a modified fuzzy cerebellar model combined with a functional link network and sliding mode control demonstrates high robustness in chaotic system synchronization and inverted pendulum control [81]. In motor control applications, an ANNC for three-phase induction motors achieves superior speed tracking and disturbance rejection compared to a fuzzy controller [82]. For electric vehicle-charging systems, an ANN-PMC-based intelligent adaptive controller improves energy management by reducing overshoot and DC bus settling time [72]. Reinforcement learning combined with deep neural networks (RL-DLNN) has been applied to chiller-type HVAC systems, achieving superior adaptation, stability, and tracking performance compared to PID and MPC controllers, especially in highly nonlinear and disturbed MIMO environments [83]. Finally, [84] proposes an adaptive neural network controller for pressure regulation in industrial processes, implemented on a Festo MPS® PA Compact Workstation and compared against conventional PID control, and the controller uses a simple feedforward neural network with sigmoid activation and online weight adaptation based on the Brandt–Lin algorithm from the adaptive interaction theory, which allows learning directly from the pressure error without an explicit training phase or prior plant model. After identifying the plant in MATLAB (67% fit) to build the simulation model, the authors compare the adaptive neural controller with two PIDs (one auto-tuned by MATLAB and one tuned by an experienced operator) in simulation and then implement both the neural controller and the operator-tuned PID on the real plant via a PLC–OPC–Simulink architecture. Experimental tests with step, ramp, square, sinusoidal, sawtooth references, and disturbance inputs show that the adaptive neural controller achieves faster response and better tracking than the PID, with lower mean error (1.28% vs. 5.13%), mean absolute error (4.77% vs. 9.59%), mean square error, and RMSE, demonstrating superior robustness and accuracy for pressure control under varying operating conditions.

Table A1 in Appendix A presents the articles that contributed to control models in control systems-based AI.

The integration of AI techniques into intelligent controllers has led to a diverse set of control-model structures. Based on the 68 studies classified in this category, fuzzy-logic-based controllers constitute the largest group with 28 contributions, confirming their central role in AI-enabled control. Within this family, 12 works employ generic FLC structures without specifying the inference type, while seven studies explicitly implement Mamdani-type controllers, typically in level, flow, or drive-control applications. Two studies adopt Takagi–Sugeno (T–S) models to handle nonlinearities via local linear models, and one work focuses on type-2 fuzzy logic, addressing membership uncertainty in highly disturbed environments. In addition, six contributions fall into the adaptive fuzzy category, including ANFIS-based schemes and self-learning fuzzy controllers capable of updating rules or scaling factors online to cope with changing operating conditions.

Beyond fuzzy controllers, five articles are primarily based on model predictive control (MPC), covering classical, robust, and economic MPC formulations for multivariable processes with constraints. Three studies belong to iterative learning control (ILC), where trajectory tracking is improved across repetitions via norm-optimal or predictive ILC structures. Ten contributions employ artificial neural networks (ANNs) as the core control mechanism, either through direct neural controllers, neural feedback linearization, or dual-network architectures for plant modeling and residual compensation. Finally, 22 studies are categorized as hybrid controllers, in which two or more paradigms (e.g., fuzzy–ANN, fuzzy–PID, ANN–PID, fuzzy–MPC, type-2 FLC + PID, H∞/H2 combined with evolutionary algorithms, or RFCMAC-based schemes) are tightly integrated into a single control law. These hybrid architectures consistently seek to exploit complementary strengths—such as fuzzy interpretability, neural learning capability, and model-based prediction—while mitigating individual limitations. This can be observed in the synthesis of node quantities in Table 2 below.

Table 2.

Control model contribution type groups.

Note: Node counts reflect multi-label assignments within the control-model dimension (68 contributions). Global percentages in Section 3.2 are computed over 188 articles, each assigned to a single dominant category.

In summary, Figure 5 presents a classification of the groups of control models that contribute to the application of AI in control systems.

Figure 5.

Control model contribution type groups (source: own elaboration based on systematic mapping).

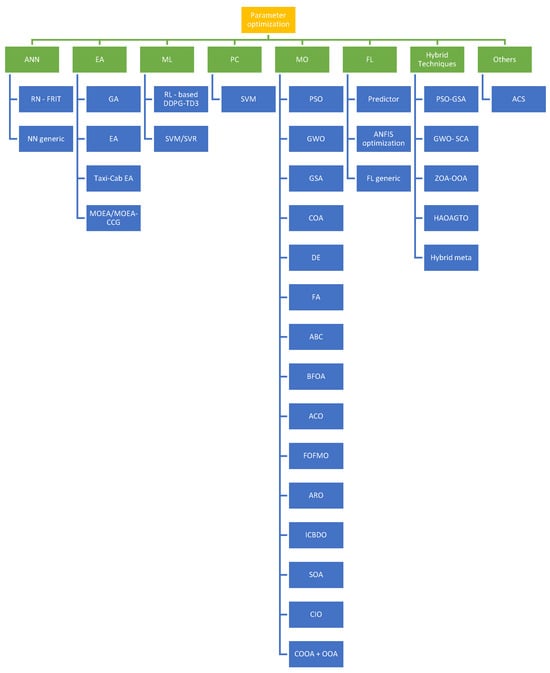

3.5.2. Result of Contributions: Optimization of Parameters

New AI optimization methods have led to significant improvements in performance, adaptability, and efficiency in the design and implementation of intelligent controllers for control systems. The following articles present contributions to optimization-based control models, grouped by their predominant technique.

Researchers employ artificial neural networks to enhance optimization and learning within controllers, as machine learning facilitates parameter tuning and improves the accuracy of control models in complex systems. ANNs effectively manage nonlinearities, increasing the accuracy and robustness of controllers in diverse environments. They have been applied to the design of PID controllers, offering an advanced method to enhance system response [85]. Support vector machines have been used for excitation control to improve system stability through supervised learning [86], and supervised learning neural networks have been utilized for learning and verification in feedback control systems [87]. Machine learning and predictive control techniques have also been applied in the design of adaptive PID controllers [88].

Evolutionary algorithms, particularly genetic algorithms, play a significant role in optimizing control parameters, especially for systems with uncertainties or nonlinear characteristics. By simulating natural evolutionary processes, these algorithms search for optimal solutions. GAs have been used to refine the rule base of Mamdani fuzzy logic controllers [89], improve modified PID controller performance [90], and enhance the adaptability of self-adjusting PID controllers [91]. Multi-objective GAs are essential for improving controller performance under competing objectives [92], including in fractional-order PID controllers for multivariable systems [93]. GAs have also been used to optimize control structures with a focus on structural adaptation [94], to fine-tune fuzzy controllers for vibration suppression [95], to develop hybrid controllers using Hydra structures optimized with GA-based strategies [96], and to support multi-objective optimization in control systems using the taxi-cab evolutionary algorithm [97].

Metaheuristic optimization algorithms such as particle swarm optimization, gray wolf optimization, gravitational search, and cuckoo optimization are widely employed to adjust parameters in complex controllers, effectively exploring large search spaces to identify optimal solutions. PSO has been applied to tune PID controllers [98], design fuzzy PID controllers for Quasi-Z-Source converters [99], optimize fuzzy-PDC controllers [100], and improve fuzzy controllers for distillation processes [101]. Gray wolf optimization has been used to optimize fuzzy PID controllers for power system frequency regulation [102], while gravitational search algorithms have improved the dynamic response of PID controllers [103]. The cuckoo optimization algorithm has been applied to energy management within fuzzy controllers [104]. Differential evolution algorithms have been used to design fuzzy controllers for wireless sensor networks [105], the Firefly Algorithm has been applied to develop optimized fuzzy PID drivers [106], and the bee colony algorithm has proven effective for designing fuzzy controllers [107].

Several articles focus on fuzzy controllers designed to manage uncertainty and variability in complex systems through fuzzy logic. Fuzzy PID controllers have shown improvements in continuous industrial processes [108], performed effectively as multivariable controllers [109], and have been applied to control underactuated manipulators [110]. A low-cost servo system based on fuzzy control is introduced in [111], while a fuzzy PID controller for BLDC motor control is proposed in [112].

Hybrid techniques combine two or more methods such as fuzzy logic and metaheuristic optimization to capitalize on their strengths and improve controller performance and adaptability. Integrated fuzzy control and optimization approaches have been employed for frequency regulation in electrical networks [113]. Hybrid GWO–SCA structures have been deployed in type-II fuzzy controllers for multi-area frequency control [114], while combinations of harmony search and cuckoo optimization have been applied in fuzzy PID drivers [115]. A hybrid PSO–GSA strategy has also been used in fuzzy sliding-mode controllers for wind power systems [116],

Predictive control techniques, which anticipate system changes and adjust control actions based on future predictions, further enhance controller adaptability and performance in systems with high variability. In this category, SVMs have been integrated into nonlinear predictive controllers to anticipate and correct system behavior multiple steps ahead [117].

Several works explore additional or unique optimization techniques that fall outside the conventional categories. These include optimized PID controllers developed using multi-objective techniques, providing effective methods to manage multiple performance criteria in control systems [118].

Finally, reference [119] presents a generic identification methodology for liquid-level systems in industrial processes based on time-series artificial neural networks, validated on a Festo MPS® PA Compact Workstation. The authors design two identifiers: a nonlinear NARX network trained with Levenberg–Marquardt and a simplified GADALINE network trained with an LMS-based algorithm including normalization and momentum, both implemented for online and offline operation. Experimental tests with different excitation signals (step, pulse train, sinusoidal, and sawtooth) show that both neural identifiers reproduce the real tank dynamics more accurately than a conventional first-order Laplace model, especially under disturbances, with GADALINE achieving the best compromise between accuracy, numerical simplicity, and availability of an explicit discrete transfer function. Using the GADALINE-based model to tune a PI controller yields improved control performance, reducing level-control settling time from 29 s to 25 s (≈13.8%) and slightly decreasing dispersion by 0.9% compared with the PI tuned from the classical identification. This section concludes that NARX and GADALINE time-series neural networks are promising tools for practical system identification in industrial processes, enabling more efficient controller design while keeping implementation complexity moderate

The analysis of optimization-focused contributions shows that metaheuristic algorithms clearly dominate the landscape, with 37 out of 85 studies (43.5%) relying primarily on population-based heuristic methods. This group encompasses a wide variety of nature-inspired optimizers, including PSO, GWO, GSA, DE, ACO, ABC, FA, HS, WOA, BFOA, FOFMO, ICDBO, SOA, and several recent variants. These algorithms are predominantly used to tune PID and fractional-order PID gains, adjust fuzzy membership functions and rule bases, or optimize hybrid controller structures under nonlinear, constrained, or highly coupled dynamics. Their prevalence confirms that global, stochastic search methods have become the default choice for parameter optimization in intelligent control systems.

Evolutionary algorithms represent the second largest family, with 16 studies (18.8%). This category includes classical genetic algorithms, multi-objective evolutionary schemes (MOEA, MOEA-CCG), and problem-specific evolutionary formulations such as taxi-cab evolutionary algorithms. In these works, evolutionary methods are commonly applied to refine controller structures, optimize multi-objective performance indices, or perform structural and parametric tuning of PID and fuzzy controllers. Together, metaheuristics and evolutionary algorithms account for more than 60% of all optimization contributions, underscoring the central role of population-based search strategies in intelligent controller design.

A smaller but relevant subset of works exploits hybrid optimization strategies, where two or more metaheuristics are combined in a single tuning framework. This group comprises 11 studies (12.9%), including, for example, GWO–SCA, PSO–GSA, ZOA–OOA, and hybrid arithmetic–gorilla optimization algorithms. These approaches aim to exploit complementary strengths—such as exploration capability from one algorithm and exploitation/refinement from another—to improve convergence speed, robustness, and solution diversity relative to single-heuristic designs.

In addition, nine studies (10.6%) fall under Fuzzy Optimization, where fuzzy mechanisms themselves (fuzzy predictors, fuzzy adaptation rules, ANFIS-based optimization, or fuzzy coefficient adjustment) are used as the core optimization engine rather than as the structure being optimized. Neural Networks Optimization accounts for six articles (7.1%), in which neural models are explicitly employed to support tuning—either as surrogate models to approximate the cost landscape or as direct learning schemes for controller parameters (e.g., neural network-based FRIT PID tuning). ML-based Optimization contributes five studies (5.9%), including SVM/SVR-based optimizers and reinforcement learning-driven tuning (e.g., DDPG, TD3) that adapt controller gains from performance data.

Finally, only one study (1.2%) remains in the Others/Miscellaneous category, corresponding to a problem-specific tunable-model formulation that does not fit neatly into the previous groups. Overall, these results confirm that parameter optimization in intelligent control is overwhelmingly dominated by metaheuristic and evolutionary methods, while hybrid, fuzzy-based, and machine learning-driven optimization provide complementary alternatives in scenarios where interpretability, online adaptation, or surrogate modeling are particularly important. This can be observed in the synthesis of node quantities in Table 3 below.

Table 3.

Optimization of parameters contribution type groups.

Note: Node counts reflect multi-label assignments within the optimization of parameters dimension (85 contributions). Global percentages in Section 3.2 are computed over 188 articles, each assigned to a single dominant category.

Table A2 in Appendix B presents the articles that have contributed to the optimization of artificial intelligence in control systems.

Figure 6 also presents a classification of the groups of optimization strategies that contribute to the application of AI in control systems.

Figure 6.

Optimization contribution groups (source: own elaboration based on systematic mapping).

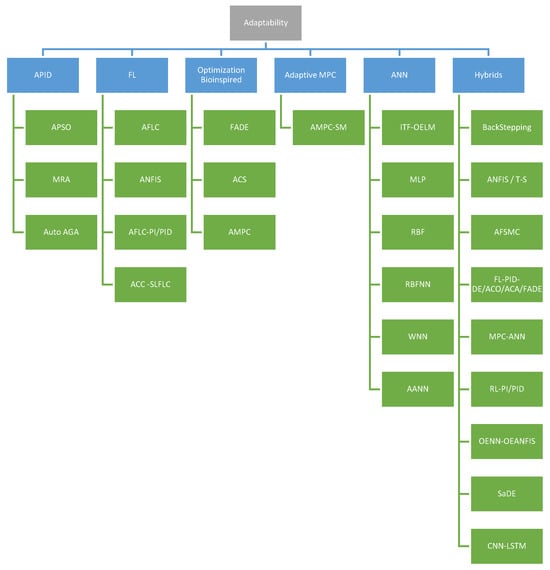

3.5.3. Result of Contributions: Adaptability

The development of adaptive control strategies has gained significant attention in recent decades due to the increasing complexity of dynamic systems, the presence of nonlinearities, time delays, parametric uncertainties, and external disturbances. In this context, several approaches have been proposed that combine classical control structures such as PID controllers, fuzzy models, and neural networks with modern techniques of adaptation, optimization, and machine learning. The reviewed literature has been organized into different categories according to the predominant control technique, allowing for a clear comparison of the strengths, limitations, and applications of each approach. The main categories include adaptive PID-based controllers, in which the classical PID structure is enhanced through optimization, fuzzy logic, or machine learning; adaptive fuzzy-based controllers (Fuzzy/ANFIS/T–S), which employ fuzzy inference to support decision making and online parameter tuning; adaptive neural network-based controllers, where neural models act as universal approximators to handle uncertain nonlinear dynamics; hybrid adaptive controllers, which synergistically combine fuzzy, neural, robust, or bio-inspired approaches; and optimization and adaptive optimal controllers, where evolutionary algorithms, heuristics, and predictive methods are used to tune parameters of classical or advanced controllers.

Within the domain of adaptive PID-based controllers, numerous studies have introduced significant improvements through optimization and learning techniques. Key contributions include the use of Adaptive Particle Swarm Optimization to tune linear and nonlinear PID controllers, improving stability and convergence speed compared to classical methods [120]; a fuzzy predictor-based adaptive PID controller that enhances online adjustment and tracking accuracy in nonlinear processes [121]; a Model Reference Adaptive System used to tune PID gains for launch vehicles under parameter variations [122]; and a self-adaptive genetic algorithm that optimizes both gains and performance indices for smoother and faster PI/PID responses [123]. Additional contributions include a PLC-implemented fuzzy PID controller for oil pipeline flow regulation [124]; a Kalman-enhanced fuzzy PID controller for liquid-level control in conical tanks, where fuzzy logic adjusts PID gains and Kalman filtering increases robustness against noise [125]; a hybrid OENN–OEANFIS structure to adapt PID parameters through endocrine-inspired neural modeling combined with neuro-fuzzy inference [126]; the use of Self-Adaptive Differential Evolution for dynamic PID tuning [127]; a deep learning-based intelligent PID (CNN–LSTM) for UAVs, predicting parameter adjustments to improve stability and energy efficiency [128]; an AIEM-DDPG algorithm to adapt PI gains in PEM fuel cells, reducing overshoot and enhancing stability [129]; and a TD3-based tuner that adaptively adjusts parameters of PI and lead controllers under uncertainty [130].

In the area of adaptive controllers based on fuzzy logic (Fuzzy/ANFIS/T–S), these methods are widely employed due to their ability to manage uncertainty and variability under changing operating conditions without requiring an exact mathematical model of the system. Notable examples include an adaptive fuzzy controller for MPPT in photovoltaic systems, which adjusts the output scaling factor online to track the maximum power point under varying irradiance and temperature [131]; an ANFIS controller for a PFC boost converter trained online using data from a conventional fuzzy controller to improve voltage regulation [132]; an adaptive fuzzy PI controller for coupled tanks, where Mamdani rules dynamically tune Kp and Ki gains to manage nonlinearities [133]; a T–S adaptive controller with a state observer for nonlinear systems with unknown dead zones, avoiding traditional backstepping complexity [134]; an ANFIS controller with hybrid learning (least squares + backpropagation) for autonomous mobile robot trajectory tracking [135]; a self-learning fuzzy controller based on Autonomous Adaptive Control that generates and updates fuzzy rules online without external supervision [136]; an ANFIS optimized with genetic algorithms for greenhouse climate control, where the GA tunes membership functions and rules to improve robustness and reduce ISE [137]; and a two-level adaptive fuzzy controller for DC motors combining a Mamdani fuzzy controller with an inverse T–S model updated in real time [138].

Regarding adaptive controllers based on bio-inspired or optimal optimization techniques, the literature presents several noteworthy implementations. These include an adaptive fuzzy controller optimized with Adaptive Differential Evolution for synthetic inertia in power systems, where DE dynamically tunes fuzzy membership functions to reduce frequency nadir and enhance stability [139]; an LQR controller optimized with Adaptive Cuckoo Search for vehicle active suspension systems, adjusting Q and R weighting matrices to reduce vertical acceleration and improve ride comfort [140]; and an Adaptive Model Predictive Control scheme employing set-membership identification and tube-based predictions to guarantee constraint satisfaction under parametric uncertainty and disturbances [141].

In the domain of adaptive controllers based on neural networks, several high-impact contributions exist. These include an Initial-Training-Free Online Extreme Learning Machine for adaptive control of nonlinear discrete-time systems with rapidly varying parameters, enabling online identification without prior training data [142]; a multilayer perceptron integrated with integral sliding mode control to compensate for residual and approximation errors in systems with dead-zone nonlinearities [143]; an adaptive Radial Basis Function Neural Network for nonlinear systems with unknown time delays, acting as a universal approximator with Lyapunov-based weight adaptation laws [144]; an adaptive RBFNN combined with second-order sliding mode control to estimate unknown dynamics while eliminating chattering [145]; an RBFNN integrated with backstepping and barrier Lyapunov functions for vibration suppression in flexible string systems with dead-zone effects and output constraints [146]; an RBFNN-based adaptive controller with a neuro-inspired Incentive Actuator Preventor (IAP) mechanism for robotic manipulators under switching constraints [147]; a wavelet neural network observer embedded in an adaptive fuzzy sliding mode stabilizer for multimachine power systems, estimating uncertainties and improving low-frequency oscillation damping [148]; and an adaptive neural network controller for DC–DC converters using online learning to compensate for model uncertainties and improve voltage regulation under dynamic loads [149].

Finally, hybrid adaptive controllers that integrate fuzzy logic, neural networks, robust control, and optimization methods represent some of the most advanced solutions. Representative contributions include a neuro-fuzzy backstepping adaptive controller applied to induction motors with unified nonlinear friction and unknown dynamics, where ANFIS is embedded within a robust backstepping framework to ensure tracking accuracy [150]; a robust adaptive fuzzy neural T–S controller for interconnected nonlinear systems, combining T–S models and neural networks to approximate unknown interconnections while a compensator handles errors [151]; a hybrid adaptive fuzzy navigation controller for mobile manipulators, combining adaptive parameter estimation with T–S fuzzy logic for obstacle avoidance and trajectory tracking in dynamic environments [152]; a robust adaptive controller based on Lyapunov/backstepping to manage strong nonlinearities and uncertainties, ensuring global stability through adaptive update laws [153]; and a fuzzy PID controller hybridized with Ant Colony Optimization for UAV path planning, where fuzzy logic adjusts PID gains in real time and ACO optimizes pheromone updating to generate shorter, smoother trajectories [154].

The adaptability-focused contributions reveal that fuzzy-based adaptive strategies clearly dominate this group. Out of the 35 studies classified under adaptability, 14 articles (40.0%) fall into the Adaptive Fuzzy/ANFIS category. These works rely on Mamdani or Takagi–Sugeno fuzzy controllers, ANFIS architectures, or self-learning fuzzy schemes that adjust rules, membership functions, or scaling factors online. Their primary goal is to handle nonlinearities, parametric uncertainty, and operating-point variations without requiring an exact plant model. Typical applications include coupled-tank processes, greenhouse climate control, photovoltaic MPPT, DC motor drives, and mobile robot trajectory tracking, where fuzzy or neuro-fuzzy controllers continuously retune gains and inference parameters to maintain performance under changing conditions.

Hybrid adaptive controllers constitute the second-largest group, with 11 studies (31.4%). These contributions integrate two or more paradigms such as fuzzy logic with sliding-mode control, fuzzy PID with metaheuristic tuning, neuro-fuzzy backstepping, or PI controllers adjusted by deep reinforcement learning (e.g., DDPG, TD3) into a single adaptive framework. In these architectures, adaptation laws are often derived from Lyapunov-based designs, optimization-driven update rules, or RL policies that update controller parameters online. Hybrid adaptive controllers are particularly prominent in complex nonlinear systems, multi-area power systems, and motion-control problems, where robustness, disturbance rejection, and constraint handling must be addressed simultaneously.

Adaptive neural networks account for five studies (14.3%), in which neural models (e.g., RBFNN, wavelet neural networks, multilayer perceptrons) are used as universal approximators of unknown nonlinear dynamics or time-varying parameters. These controllers typically incorporate adaptive weight-update laws derived from Lyapunov stability analysis, barrier functions, or sliding-mode frameworks, and are applied to systems with dead zones, time delays, flexible structures, or robotic manipulators. Adaptive PID controllers represent three studies (8.6%), where classical PI/PID structures are augmented with online tuning rules—often based on reference-model adaptation, fuzzy predictors, or self-adaptive search strategies—to maintain desired transient and steady-state performance under varying operating conditions.

Only one article (2.9%) is categorized as adaptive MPC, implementing an MPC scheme with adaptive model or constraint updates to cope with parametric uncertainty and disturbances while preserving constraint satisfaction. Another single study (2.9%) is classified as Bio-inspired Adaptive Control, where the adaptation of a model-based controller LQR is governed directly by a bio-inspired optimizer—in this case, an Adaptive Cuckoo Search algorithm—rather than relying solely on analytical update laws. Overall, these results show that adaptability in intelligent control is predominantly addressed through fuzzy/ANFIS architectures and hybrid adaptive schemes, with neural controllers providing additional flexibility in highly nonlinear settings, and with bio-inspired and adaptive MPC approaches emerging as complementary but less frequently explored directions. This can be observed in the synthesis of node quantities in Table 4 below.

Table 4.

Adaptability contribution type groups.

Note: Node counts reflect multi-label assignments within the Adaptability dimension (35 contributions). Global percentages in Section 3.2 are computed over 188 articles, each assigned to a single dominant category.

Table A3 in Appendix C presents a detailed table of the articles that contributed to the adaptability of artificial intelligence in control systems.

In summary, Figure 7 also presents a classification of the groups of adaptability strategies that contribute to the application of AI in control systems.

Figure 7.

Adaptability contribution type groups (source: own elaboration based on systematic mapping).

4. Discussion

The systematic mapping reveals a rapidly evolving landscape in AI-enabled control systems, characterized by the emergence of hybrid controllers, metaheuristic optimization frameworks, and advanced adaptive strategies. The analysis consolidates methodological patterns, evaluates practical trade-offs, and highlights critical gaps that must be addressed to translate academic contributions into industrial solutions.

4.1. Comparative Analysis of Control Strategies

Hybrid controllers, particularly neuro-fuzzy systems and ANN-enhanced PID or MPC structures, stand out for their ability to combine interpretability, learning capability, and robustness. They consistently outperform single-technique controllers in nonlinear and highly uncertain environments. Fuzzy controllers provide strong performance in systems where interpretability and tolerance to uncertainty are essential, but they often require rule base optimization to prevent scalability issues. Neural network controllers offer superior adaptability and modeling power but face challenges in explainability, training data dependence, and stability guarantees. Model predictive control remains highly effective for constrained and multivariable systems, yet computational cost limits its deployment in fast real-time applications unless combined with learning-based surrogate models. Metaheuristic approaches, especially PSO, GWO, DE, and hybrid GWO-SCA/PSO-GSA algorithms, demonstrate strong global search efficiency and robustness in tuning controller parameters, but their computational load varies widely and their hyperparameter choices remains inconsistently reported.

Additional experimental evidence from four real-plant studies reinforces these comparative observations. The Mamdani fuzzy PI controller implemented for liquid-level regulation demonstrated a faster settling time and a greater disturbance rejection than both operator-tuned and auto-tuned PID controllers. Likewise, the fuzzy–Smith compensator applied to induction motor control in a networked environment outperformed classical PID under time-delay and packet-latency conditions. Adaptive neural control using the Brandt–Lin algorithm further showed superior transient response and steady-state accuracy compared with PID benchmarking. Together, these results confirm that intelligent controllers offer measurable advantages in robustness, adaptability, and performance when compared directly to conventional techniques.

4.2. Limitations and Threats to Validity

This review presents several limitations and threats to validity that should be considered when interpreting its findings. First, the search strategy relied on a specific set of digital libraries and indexing services; relevant contributions indexed exclusively in other databases or domain-specific repositories may have been omitted. Second, only articles written in English were considered, which introduces a potential language bias and may underrepresent research produced by non-English-speaking communities.

Third, the search queries were formulated around specific combinations of terms related to intelligent controllers, artificial intelligence, adaptation, and optimization. Although the Boolean strings were iteratively refined and piloted, studies that employ substantially different terminology might not have been captured. Fourth, study selection and data extraction, while conducted through double screening with a substantial inter-rater agreement (κ = 0.87), inevitably involve a degree of subjectivity, particularly when assigning each paper to a dominant category within the proposed taxonomy and when handling multi-label cases.

Finally, the review is restricted to peer-reviewed literature and includes four experimental studies authored by the present research group, which may introduce mild publication and self-citation bias. These limitations do not invalidate the overall trends and gaps identified in this work, but they indicate that the results should be interpreted as a structured yet inherently partial view of the rapidly evolving field of AI-based intelligent control systems.

4.3. Validation Gap and Domain-Specific Practical Outcomes

Although AI-based controllers frequently report improvements in accuracy, overshoot reduction, stability, and disturbance rejection, the present mapping shows that the evidence base is still heavily dominated by simulation studies. This imbalance limits the generalizability of results to industrial environments, where measurement noise, actuator nonlinearities, sensor degradation, saturation, and dynamic disturbances are pervasive. For instance, fuzzy-based MPPT controllers routinely achieve faster convergence under irradiance changes in simulation, yet only a small subset of works extends the analysis to real-field variability or environmental noise in grid-connected photovoltaic plants. Similar patterns appear in other domains, where promising control strategies are often validated only under idealized operating conditions.

The mapping also highlights meaningful differences across application domains:

- Renewable energy systems: AI-based controllers improve MPPT tracking, generator stability, and pitch control, but scalability to utility scale plants remains insufficiently validated, and long-term field campaigns are scarce.

- Robotics and autonomous systems: hybrid and learning-based controllers enhance trajectory tracking and disturbance rejection, yet real-time feasibility is often constrained by computational cost and hardware limitations.

- Agriculture and environmental systems: fuzzy and ANFIS controllers provide robust performance under uncertainty; however, few studies quantify energy efficiency, reliability, or maintenance gains with respect to PID baselines in real operating conditions.

- Industrial process control: MPC and hybrid neural controllers demonstrate strong improvements in setpoint tracking and constraint handling, but deployment still requires lightweight implementations and hardware-friendly computation strategies.

By contrast, the relatively small set of experimentally validated studies including adaptive fuzzy PID controllers in oil pipelines, neuro-fuzzy drives for induction motors, adaptive MPC in CSTR reactors, and the four implementations on Festo MPS PA Compact Workstations reviewed here provides valuable evidence that simulation-to-hardware transfer is feasible when robustness to modeling errors, network-induced delays, and actuator limitations is explicitly addressed in the controller design. These works cover level and pressure regulation, motor speed control, and system identification in industrial training plants, and consistently report faster stabilization, lower tracking error, and improved disturbance rejection compared with operator-tuned or auto-tuned PID controllers. They further show that fuzzy PI controllers and ANN-based identification pipelines can enhance robustness in liquid-level processes, adaptive neural controllers can shorten recovery times in pressure regulation, and fuzzy–Smith compensators can effectively mitigate time-delay effects in networked induction-motor drives.

Taken together, the domain-specific analysis and the limited but positive experimental evidence highlight an urgent need for standardized benchmarks and reporting practices that link simulations, hardware-in-the-loop tests, and full plant trials. Future research should systematically document operating conditions, disturbance profiles, implementation details, and computational budgets, enable meaningful cross-domain comparisons, and accelerate the transition of AI-based intelligent controllers from laboratory prototypes to reliable industrial solutions.

4.4. Optimization and Reproducibility Challenges

A critical limitation identified across optimization-based controllers is the absence of reproducible hyperparameter specifications. Many primary studies do not report population sizes, inertia weights, crossover probabilities, search agent counts, or termination criteria for algorithms such as PSO, GA, DE, and GWO. This omission hinders replicability, prevents fair comparisons between optimization strategies, and restricts industrial adoption. While recent hybrid optimizers (OOA, ZOA, ARO, hGWO-CS, NewBAT, MPA) address some limitations of earlier algorithms through improved convergence and exploration–exploitation balance, their performance cannot be independently verified without standardized reporting of hyperparameter settings and computational budget.

The identification results using NARX and GADALINE neural networks highlight additional reproducibility concerns in system identification. The NARX network required careful configuration of time delays and neuron architecture, while the GADALINE estimator depended on learning-rate tuning and momentum scheduling. Although both methods surpassed classical Laplace identification, neither study reports exhaustive hyperparameter settings, training iterations, or computational budgets reflecting a broader reproducibility gap also noted in optimization-based controllers. These observations support the need for standardized reporting protocols that document learning parameters, model complexity, and convergence metrics.

4.5. Integration of Emerging Techniques

Recent contributions increasingly explore DRL, including TD3-, DDPG-, and CNN–LSTM-based adaptive controllers. These techniques significantly enhance adaptability and real-time decision making, offering clear advantages in highly nonlinear or time-varying environments such as HVAC MIMO systems and autonomous vehicles. However, DRL methods introduce new challenges, including sample inefficiency, training instability, safety constraints, and substantial computational requirements factors often overlooked in simulation-based studies. Integrating DRL with classical and fuzzy control structures may help mitigate these issues by leveraging prior knowledge and constraint-aware control laws.

Recent contributions show increasing convergence between intelligent identification and intelligent control. The combination of ANN-based system identification (NARX and GADALINE) with PI control tuning, as demonstrated in one of the reviewed studies, exemplifies the emerging trend of tightly coupling modeling and control. This integration enables data-driven prediction, online learning, and improved adaptation in a unified pipeline. Similarly, adaptive neural controllers leveraging the Brandt–Lin algorithm represent an intermediate step between classical adaptive schemes and deep reinforcement learning, enabling real-time learning without pretraining.

4.6. Reproducibility Issues in Parameter Optimization Methodologies

A critical issue identified across the analyzed literature is the lack of reproducible detail regarding the configuration of meta-heuristic algorithms used for controller parameter optimization. Although numerous studies report the use of optimization techniques such as PSO, GA, GWO, GSA/CGSA, ABC, DE, WOA, GOA, and others, the vast majority do not provide the essential hyperparameter settings required to replicate their optimization processes.

In most cases, the articles mentioned only the algorithm name but omitted key configuration parameters, including population size or number of agents, which fundamentally determines the exploration capability of the algorithm.

Total number of iterations or generations directly affects convergence behaviors.

Internal coefficients are as follows:

- PSO inertia weight and cognitive/social parameters (w, c1, c2);

- GA crossover and mutation probabilities and elite size;

- GWO coefficients (a, A, C);

- GSA/CGSA gravitational constants, decay factors, and chaotic maps;

- ABC abandonment limits and employed/onlooker bee counts;

- GOA adaptive coefficient c.

Parameter search bounds for controller gains (Kp, Ki, Kd), fractional orders, or fuzzy scaling factors.

Additionally, only a small subset of studies specify the following:

- Whether a random seed was used to ensure experimental reproducibility;

- The software platform and version (e.g., MATLAB/Simulink, toolboxes, hardware);

- Stopping criteria, constraint-handling strategies, or performance thresholds;

- Any sensitivity analysis that assesses how hyperparameter changes influence the outcome.

This lack of methodological transparency makes it difficult to achieve the following:

- Replicate published tuning results;

- Compare the effectiveness of different optimization algorithms under consistent conditions;

- Validate the robustness of the control strategies reported in the literature.

Consequently, two studies may claim to use the “same algorithm” (e.g., PSO or GA), while their actual optimization processes and therefore their results differ substantially.

It is therefore recommended that future research adopt more rigorous reporting practices, including detailed hyperparameter tables, explicit description of performance indices and stopping criteria, and, where appropriate, pseudocode or supplementary reproducibility checklists, in line with current international best-practice standards for reproducible computational research.

4.7. Synthesis of Findings

Overall, intelligent control research demonstrates significant progress in addressing nonlinearities, uncertainties, and multi-objective requirements. However, simulation-heavy evaluations, incomplete reporting, high computational burden, and a lack of standardized experimental protocols limit the field’s reproducibility and industrial applicability. Emerging approaches including hybrid learning–optimization frameworks, DRL-based adaptive controllers, and real-time surrogate modeling show promise but require further benchmarking under operational constraints.

Synthesizing across the four experimental contributions, several consistent patterns emerge, i.e., (1) fuzzy-based controllers tend to outperform PID in disturbance-rich nonlinear processes; (2) adaptive neural controllers provide superior transient performance and accuracy, particularly when online learning is enabled; (3) ANN-based identification pipelines significantly enhance controller performance compared with classical identification; and (4) Smith-predictor-based structures benefit substantially from fuzzy compensation to handle time delays. These findings align with the broader literature indicating that hybrid AI-based controllers combine interpretability, learning, and robustness in ways unattainable for traditional methods.

4.8. Implications and Recommendations

To accelerate practical adoption, future research should prioritize the following:

(1) Standardized reporting of optimization hyperparameters and computational budgets.

(2) Experimental validation under diverse and realistic industrial conditions.

(3) Development of lightweight and embedded-oriented AI controllers.

(4) Systematic comparison of controllers across common datasets, benchmarks, and disturbance profiles.

(5) Scalable hybrid architectures combining interpretability and learning efficiency.

(6) Safety-aware DRL and constraint-integrated learning methods.

Building on these priorities, the results of the four reviewed studies suggest that future intelligent controllers should integrate real-time learning mechanisms, simplified and lightweight ANN architectures, and hybrid compensatory structures capable of handling modeling errors, disturbances, and network-induced delays. Models such as GADALINE provide a promising path for embedded implementation due to their low computational demand, while delay-aware intelligent architecture such as fuzzy–Smith compensators demonstrate the need for controllers that combine fuzzy reasoning with predictive capabilities. To maximize reproducibility and industrial applicability, future publications should standardize hyperparameter reporting, dataset availability, tuning methodology, and computational specifications. This consolidated perspective provides a coherent basis for guiding the development of next-generation intelligent control systems capable of achieving robustness, transparency, adaptability, and real-time performance in modern industrial environments.

This review provides a consolidated basis for identifying promising research directions and guiding the development of next-generation intelligent control systems capable of fulfilling industrial requirements for robustness, transparency, and real-time performance.

5. Conclusions

5.1. Main Findings