Abstract

Background: Many everyday electronic devices incorporate embedded computers, allowing them to offer advanced functions such as Internet connectivity or the execution of artificial intelligence algorithms, giving rise to Tiny Machine Learning (TinyML) and Edge AI applications. In these contexts, models must be both efficient and explainable, especially when they are intended for systems that must be understood, interpreted, validated, or certified by humans in contrast to other approaches that are less interpretable. Among these algorithms, linguistic fuzzy systems have traditionally been valued for their interpretability and their ability to represent uncertainty with low computational cost, making them a relevant choice for embedded intelligence. However, in dynamic and changing environments, it is essential that these models can continuously adapt. While there are fuzzy approaches capable of adapting to changing conditions, few studies explicitly address their adaptation and optimization in resource-constrained devices. Methods: This paper focuses on this challenge and presents a lightweight evolutionary strategy, based on a micro genetic algorithm, adapted for constrained hardware online on-device tuning of linguistic (Mamdani-type) fuzzy models, while preserving their interpretability. Results: A prototype implementation on an embedded platform demonstrates the feasibility of the approach and highlights its potential to bring explainable self-adaptation to TinyML and Edge AI scenarios. Conclusions: The main contribution lies in showing how an appropriate integration of carefully chosen tuning mechanisms and model structure enables efficient on-device adaptation under severe resource constraints, making continuous linguistic adjustment feasible within TinyML systems.

1. Introduction

In recent years, connected devices have proliferated, driving the development of new solutions based on the Internet of Things (IoT). These systems, in addition to collecting information from their surroundings, enable intelligent services in a wide range of contexts, from industry and agriculture to the smart home.

In this regard, it is important to consider that IoT applications typically run their processes on devices with limited resources, while data analysis, processing and potential learning are primarily performed on cloud servers, leveraging Cloud Computing. This setup can lead to two types of challenges: those related to high latency and those associated with the mobility of devices, which must remain continuously connected to the network [1].

To address these issues, the paradigm of Edge Computing (EC) emerged [2]. This paradigm essentially eliminates the need to send large amounts of data to the cloud. Instead, data is processed either on devices close to the data sources (known as Edge devices) or even on the devices themselves (known as Embedded devices). This approach offers several advantages:

- Data Security and Privacy: Certain applications require data privacy. In these cases, sending data to cloud systems poses a significant risk of attacks. EC addresses this by processing data locally, eliminating the need to transmit it off the device.

- Real-Time Response: Applications like traffic control and monitoring require real-time responsiveness. In cloud-based systems, this can be problematic, as an increase in the number of devices leads to higher data volumes, greater network traffic and higher bandwidth consumption. EC avoids this issue by processing data directly on the device, ensuring minimal or zero latency.

- Energy Efficiency: The rising number of IoT devices has significantly increased energy consumption in cloud servers. EC enables local or near-local data processing, eliminating the growing centralized energy demands.

IoT solutions [3], and consequently those based on EC [4], often operate in highly dynamic environments. The specific characteristics of these environments and suitable learning models for such conditions are detailed in [5]. In these scenarios, data are frequently volatile and imprecise, making response time critical. In this context, Fuzzy Rule-Based Systems (FRBSs) are a particularly appealing option due to their inference speed [6].

Another important aspect within the scope of EC is the increasing use of Microcontroller Unit (MCU)-based devices in recent years. These units typically feature limited resources, with constrained computational and storage capacities. However, they are characterized by extremely low power consumption, allowing them to operate efficiently even with small batteries [7].

Tiny Machine Learning (TinyML) [7,8,9,10] is an area where traditional Machine Learning (ML) models are adapted for deployment in MCU-based devices. Initially, these models were trained or fine-tuned externally, either through software environments or cloud services, so that the resource-constrained device was solely responsible for inference based on specific input data. The model is trained once, compressed, and subsequently deployed onto the device [8]. A further advancement occurs when the training (or part of it) is conducted directly on the device, giving rise to what is known as On-Device Learning (ODL) [11]. In this case, not only the trained model, but also the learning algorithm must be computationally efficient.

In the approaches described so far, the use of ML models can be considered static, as the model is trained once and remains unchanged over time. However, when the environment or application conditions evolve, the model may become outdated, underperform, or even become obsolete. To address this issue, the concept of training or fine-tuning the model on the device in real-time emerges. This is referred to as TinyML with Online Learning (TinyOL) [12], where the trained models are dynamic and capable of evolving over time as conditions demand. This new paradigm enables models to be trained (or partially adjusted) on the device itself, while simultaneously performing inference based on input data.

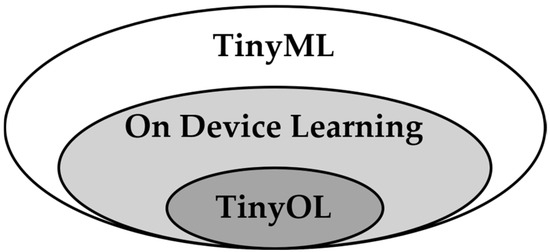

Figure 1 schematically represents the various ML paradigms discussed, as applied to resource-constrained or MCU-based devices.

Figure 1.

Diagram of TinyML, ODL and TinyOL paradigms.

FRBSs [13] have been employed in numerous devices since their inception. Historically, they have been used to address a wide range of problems, including control, regression and classification tasks. These systems share a common approach: modelling knowledge through a descriptive language based on fuzzy logic predicates, where a set of rules defines the system’s behavior in response to specific inputs.

The advantages of such systems lie in several key aspects, including the following [14]:

- Fuzzy logic provides the most “natural” way to express information ambiguity. As a result, generated models are able to effectively represent environmental uncertainty.

- These systems are easily interpretable, as they represent knowledge extracted from data in a manner closely aligned with human reasoning, using rules and linguistic terms. This type of interpretability is currently referred to as by design, inherently interpretable models, model-based interpretability, transparent models and intrinsically interpretable [15,16,17,18,19,20,21], as opposed to interpretability achieved through external techniques, that is, post hoc interpretability or explainability.

- They are highly flexible systems, meaning they can be readily adapted. Both their knowledge base and inference engine can be parameterized, allowing them to evolve online with minimal computational effort.

These advantages make FRBSs highly appealing for use in IoT devices [22,23,24].

Within this context, the key scientific contributions delivered by this work are detailed as follows:

- A comprehensive discussion on the TinyML concept and the potentially feasible models.

- Insights of the feasible implementation requirements for FRBSs in such environments.

- A solution based on an online tuning mechanism for FRBSs, specifically a TinyOL Linguistic Fuzzy model for real-world scenarios. This model has been implemented in a specific case study to illustrate its functionality.

It is therefore important to emphasize that this proposal aims to enable classical linguistic FRBS, whose main characteristic is the use of human interpretable rules, to operate in EC scenarios where dynamic, on-device adaptation is required.

This paper is organized as follows: Section 2 reviews the TinyML philosophy, describing its foundations, models and emerging challenges. Section 3 outlines the requirements for designing FRBSs in TinyOL environments and presents the proposed TinyOL Linguistic Fuzzy model. Section 4 introduces the case study developed using this model and analyses the results obtained. Finally, Section 5 provides the main conclusions derived from this work.

2. Technical Background on TinyML, On-Device Learning and Tiny Fuzzy Systems

This section delves deeper into the TinyML paradigm, discussing the principles of this philosophy and the types of ML models implemented in the literature. Additionally, it describes the main challenges associated with TinyML as well as the TinyOL paradigm, which is the focus of this work. Finally, it addresses existing FRBS adaptation techniques. These foundational elements serve as the basis for outlining the characteristics that FRBSs developed within this paradigm should possess.

2.1. Principles of TinyML

As previously introduced, TinyML is the paradigm that enables the execution of ML models on resource-constrained devices.

Considering the requirements of devices for TinyML systems [25], the constraints for developing this paradigm are as follows:

- Energy Constraint: Embedded devices in EC require a minimum battery capacity of 10–100 mAh to operate autonomously. This implies that ML algorithms must incorporate specific techniques aimed at minimizing energy consumption.

- Processor Capacity Constraint: Tiny devices typically have clock speeds ranging from 10–1000 MHz. This imposes efficiency constraints on the selected ML models, particularly on highly complex ones.

- Memory Constraint: Tiny devices have significantly less than 1 MB of SRAM, with values often below 100 kB. This implies the use of models whose characteristics align with these MCU limitations.

- Cost Constraint: Devices must be as inexpensive as possible. While individual devices may be low-cost, deploying thousands of them can lead to substantial expenses as the system scales.

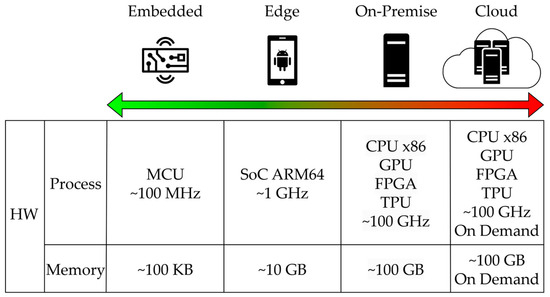

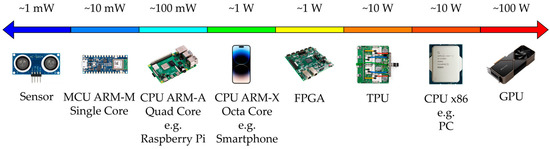

Figure 2 and Figure 3 illustrate these constraints. Figure 2 provides a comparative overview of processor and memory limitations across Embedded (TinyML), Edge, On-Premise and Cloud devices. Figure 3 shows the energy consumption of various IoT-compatible devices, highlighting the distinction between those suitable for TinyML (MCUs) and those that are not.

Figure 2.

Embedded device hardware constraints. The gradient arrow illustrates the spectrum from resource-constrained embedded devices (green: low power consumption) to resource-rich cloud servers (red: high power consumption on-demand).

Figure 3.

Embedded device energy consumption constraints.

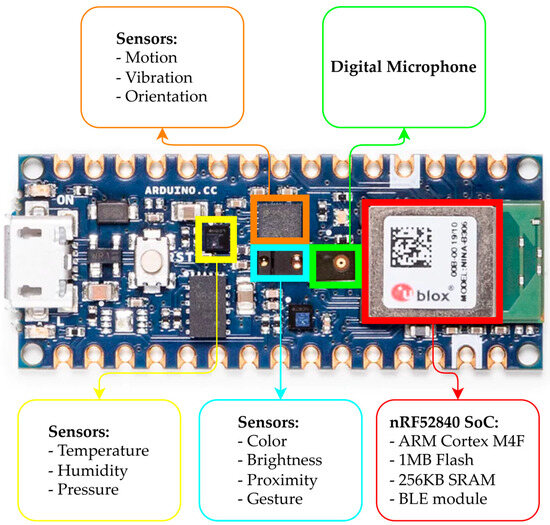

Most small IoT hardware platforms available on the market operate below 100 MHz processor speed, with less than 1 MB of flash memory and less than 1 MB of SRAM. Regarding connectivity, Bluetooth and Wi-Fi are the most commonly used standards. Additionally, many devices include sensors such as accelerometers, gyroscopes, temperature, humidity and atmospheric pressure sensors, as well as microphones and cameras. The energy consumption of these devices typically falls within the milliwatt range. The most popular microcontroller cores used in devices for TinyML applications are from the ARM Cortex-M family, with the Cortex-M4 being particularly notable [8]. This microcontroller will be used in the application presented in this work, an nRF52840, which also forms the basis of the well-known Arduino Nano 33. Its tiny dimensions, low cost and energy efficiency, which have made it a component in tens of billions of consumer devices, should not overshadow the fact that it is a 32-bit RISC device with noteworthy computational capabilities.

2.2. TinyML Models and Use Cases

In this subsection, a selection of relevant TinyML models and use cases, drawn from the specialized literature, is presented.

There are studies aimed at describing the types of models that can be implemented in TinyML [26], but most contributions do not perform on-device model tuning [8].

The main contributions in TinyML found in the state-of-the-art literature have been organized according to the taxonomy of traditional ML algorithms in Table 1. Specifically, it highlights which works propose training or tuning the model directly on the device (ODL) and those that suggest using static models solely for inference (Infer).

Simpler classical ML models, such as Decision Trees or Linear Regression, are particularly suitable for more limited hardware. However, due to the remarkable results and advancements offered by Deep Learning models, Neural Networks have become the most widely adapted models for low-resource devices. To address memory and computational time constraints, several techniques have been developed to enable these resource-intensive models to function as inference engines directly on the devices where data is collected. These techniques include Hyperdimensional Computing [27], Swapping [28], Attention Condensers [29], Constrained Neural Architecture Search [30], Quantization [31] and the Once-For-All Network [32].

Based on this review, we can conclude that on-device inference methodologies have reached a mature stage. However, the development of on-device learning methodologies, particularly for MCU-based systems, is still in its early stages.

Table 1.

TinyML state-of-the-art taxonomy. (DT: Decision Tree; KNN: k-Nearest Neighbors; ANN: Artificial Neuronal Network; RF: Random Forest; SVM: Support Vector Machine; LR: Logistic Regression; NB: Naive Bayes).

Table 1.

TinyML state-of-the-art taxonomy. (DT: Decision Tree; KNN: k-Nearest Neighbors; ANN: Artificial Neuronal Network; RF: Random Forest; SVM: Support Vector Machine; LR: Logistic Regression; NB: Naive Bayes).

| References | Taxonomy | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Infer/ODL | Algorithm | Purpose | Learning Type | |

| [9,33] | Infer | DT | Classification | Supervised Learning |

| [27,34,35] | Infer | KNN | ||

| [36,37] | ODL | |||

| [9,28,29,30,31,32,33,35,38,39,40,41,42,43] | Infer | ANN | ||

| [12,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56] | ODL | |||

| [9,33,35,57,58] | Infer | RF | ||

| [9,33,34,35] | Infer | SVM | ||

| [33,34] | Infer | LR | ||

| [33,34] | Infer | NB | ||

| [59,60,61] | Infer | RF | Regression | |

| [60] | Infer | LR | ||

| [60,61] | Infer | SVM | ||

| [61,62,63] | Infer | ANN | ||

| [64] | ODL | K-Means | Clustering | Non-Supervised Learning |

| [65] | ODL | DBSCAN | ||

| [66,67,68] | ODL | TEDA | Anomaly Detection | |

| [69] | Infer | BERT | LLM | |

| [70] | ODL | |||

| [71] | Infer | Reinforcement Learning | ||

| [72] | Infer | Self-Supervised Learning | ||

2.3. TinyML Challenges

Despite the growing accessibility of ML tools and frameworks, the development of ML applications for resource-constrained environments remains a significant challenge. Most existing models are designed without consideration for the computational and memory limitations typical of embedded IoT devices [26]. As a result, deploying these models in such environments requires additional optimization techniques such as quantization and pruning [8].

A fundamental limitation of many TinyML solutions is their reliance on static models: trained once offline, optimized, and then deployed. This static approach is ill-suited for dynamic environments, where changes over time can render pre-trained models ineffective. Online and continual learning paradigms, such as ODL, have been proposed to overcome this limitation by enabling models to adapt in real-time directly on the device.

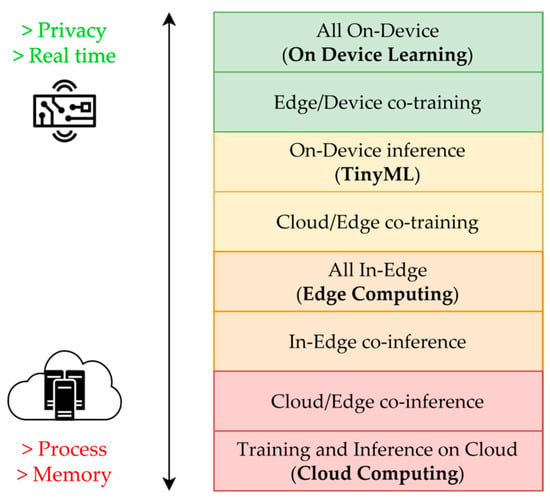

Based on the 6 G White Paper on Edge Intelligence [73], Figure 4 illustrates the balance through the processing tasks that are performed locally on the device and those done on remote servers, as well as the availability of resources for algorithms, data privacy and response speed.

Figure 4.

Level rating of Edge Intelligence. Colors indicate the trade-off between on-device learning (green), offering maximum privacy and real-time response, and cloud computing (red), providing higher processing power and larger memory capacity.

However, achieving effective ODL in TinyML contexts is non-trivial. While ODL enhances privacy and responsiveness by eliminating the need for cloud-based retraining, it introduces challenges related to energy efficiency and computational overhead. Optimizing algorithms to operate within the strict resource budgets of embedded devices is a key research area. Complementary techniques like Federated Learning offer potential solutions by enabling collaborative model training across distributed devices [74,75]. Yet, issues such as device heterogeneity and unreliable network connectivity pose additional hurdles.

TinyOL further complicates the scenario, as it emphasizes real-time, continual adaptation with minimal or no persistent data storage. This necessitates efficient incremental learning strategies that can operate on small data buffers while maintaining model accuracy and minimizing latency. Moreover, the speed of learning must be balanced with inference performance to ensure that the system remains responsive.

Overall, the development of adaptive TinyML systems calls for innovations across algorithm design, optimization strategies, and deployment frameworks, with special attention to maintaining a balance between accuracy and efficiency.

2.4. Fuzzy Systems in Tiny Computing

Fuzzy logic has played an essential role as a technological precursor to the current paradigm known as Tiny Computing, understood as the design of intelligent systems for embedded environments and devices with limited resources [76]. Since the 1970s, and on a massive scale during the 1980s and 1990s, fuzzy logic enabled the implementation of efficient control and decision-making systems in hardware with reduced computational capabilities [77,78,79] long before the popularization of AI based on ML.

Currently, fuzzy systems continue to evolve and coexist to enhance TinyML systems in hybrid architectures that combine fuzzy logic with lightweight ML models to perform intelligent and robust inferences in multiple applications. These include, among others, anomaly detection [80], energy optimization of smart buildings [81] and remote monitoring of healthcare environments [82]. The aim of these hybrid approaches is to improve the accuracy, energy efficiency, and adaptability of models by leveraging the interpretable reasoning of fuzzy logic together with Tiny Computing methodologies.

In summary, fuzzy logic not only anticipated the technological challenges that are now being addressed in Tiny Computing, but continues to evolve as part of hybrid solutions, serving as a key tool for the development of intelligent, low-power, high-performance applications in devices with limited resources.

2.5. Dynamic On-Device Fuzzy Systems Adaptation

Fuzzy systems offer a compelling alternative to neural networks in the context of EC, where models must operate under strict constraints in energy, memory, and interpretability. Unlike neural networks, which typically function as black-box models requiring significant computational resources for inference and online adaptation, fuzzy systems employ transparent rule-based logic that is both interpretable and computationally lightweight.

In environments with continuously evolving data, Evolving Fuzzy Systems (EFSs) [83] are valued for their ability to handle uncertainty, while continuously adapting their Rule Base (RB) and parameters without storing historical data, what makes them well-suited for real-time tasks [84,85]. To maintain their accuracy over time, EFSs apply structural adaptations such as rule adding (to handle concept drift), rule merging (to reduce redundancy), and rule pruning (to improve interpretability and prevent overfitting).

While EFSs are well-studied in terms of adaptability and learning performance, their designs generally rely on TSK-type models and numerical update mechanism, and relatively little attention has been given to their suitability for resource-constrained environments. Many existing implementations assume the availability of sufficient memory and processing power, which can limit their applicability in embedded systems, low-power devices, or edge computing scenarios.

The gap addressed by our proposal is enabling robust and adaptive linguistic fuzzy learning, preserving interpretability, while maintaining the computational efficiency required for real-time, resource-limited TinyML platforms.

3. Design of TinyOL Fuzzy Models

This section first describes, from a general perspective, the key requirements and design considerations necessary to implement FRBSs for TinyML and TinyOL environments. Then, a specific proposal is illustrated: a TinyOL Linguistic Fuzzy model based on a linguistic (Mamdani-type) fuzzy system for real-world scenarios.

3.1. FRBSs in Edge Computing, TinyML and TinyOL Environments

FRBSs are suitable techniques for EC environments due to their relatively low computational requirements in terms of CPU, memory and storage capacity. In fact, this concept has been widely applied for decades in various embedded control systems across numerous real-world devices [86,87]. Moreover, current IoT devices can also integrate FRBSs as part of their internal components [88,89]. In these cases, FRBSs are designed, tested and refined by engineers and then embedded into low cost, resource-constrained devices for deployment in real-world applications.

Additionally, FRBSs are also viable for TinyML environments. Many well-established learning and tuning mechanisms for FRBSs can be adapted, with relatively minor modifications, for use on resource-constrained devices, either during the design phase or even in deployment. In the latter case, FRBSs can operate within TinyML environments with online learning capabilities, known as TinyOL. Here, the system must support online learning or tuning of the model through an algorithm executed directly on the device autonomously, i.e., learning or tuning itself within its operational environment. This is the core novelty of the proposal presented in this work.

The following considerations must be addressed when designing or adapting an FRBS capable of on-device learning or tuning within TinyOL environments:

- Model Compactness: The FRBS designed should be as compact as possible. A reduced set of variables and rules is preferable, not so much due to the computational load during inference, which is light with a well-chosen set of inference and defuzzification operators, but primarily to minimize computational effort during the learning or tuning phase. In this phase, the volume of calculations, and consequently the time and energy required, can become excessive in less compact models. Low-granularity partitions for fuzzy variables are recommended, as these lead to fewer rules and fewer parameters to adjust subsequently.

- Learning or Tuning Mechanism Characteristics: Similarly, among the wide range of learning and tuning models proposed in the literature over the decades, those with lower computational overhead and higher efficiency should be selected for online execution on the device. In this regard, we can distinguish between learning models and tuning models [90] for elements of the Knowledge Base (KB). Learning models typically learn the RB using a fixed Data Base (DB), making them computationally heavier. Tuning models, which focus on fine-tuning the DB while assuming a fixed, unmodifiable RB, are more computationally efficient and therefore preferable. This work adopts the latter approach and describes its implementation in detail in the following Section 3.2. Additionally, adaptive inference operators [91,92] can also be adjusted or learned.

- Model Evaluation Mechanism: An autonomous evaluation mechanism may not always be feasible or straightforward in all real-world applications. To design an FRBS capable of online adaptation and improvement, it must evaluate its own accuracy to decide whether to trigger the adaptation process when necessary and to guide that process. Traditional FRBS learning or tuning processes often involve a search mechanism, frequently evolutionary [93], that generates alternative changes to the current KB (e.g., to the RB or DB) and an evaluation mechanism to assess these alternatives. An appropriate metric and evaluation strategy should be defined based on the application, including the following options:

- -

- Evaluation in the Real Environment: This strategy evaluates alternative KBs directly within the application. Challenges include its infeasibility in critical applications where worse-than-current alternatives cannot be tested and the amount of time required to quantify each alternative. Consequently, this strategy is generally not preferred if other evaluation strategies are feasible.

- -

- Evaluation via Exact Simulation: For some applications, exact simulation is possible, allowing the system to predict the output for alternative KBs based on recent real-world input data. If this option is available, it is preferred due to its precision and speed.

- -

- Evaluation via Surrogate Model: When evaluation in the real environment is not feasible and exact simulation is unavailable, a surrogate model can be constructed using past application data. While this approach is faster once the model is built, it depends on the accuracy of the surrogate model, which may not always reflect the evolving real application.

- The choice among the three evaluation strategies depends on the constraints and requirements of the application. For safety-critical or latency-sensitive scenarios (e.g., autonomous systems), real-environment evaluation is generally avoided due to the risk of performance degradation. In such cases, exact simulation is preferred. When neither direct testing nor accurate simulation is available, such as in complex, dynamic environments, a surrogate model offers a practical trade-off. However, this requires sufficient historical data and ongoing updates to maintain fidelity. Resource availability, criticality of decisions, and system observability should guide strategy selection.

- For strategies other than real-environment evaluation, the device must store some data in a buffer for evaluation purposes. This requires policies for buffer sizing and data replacement, etc., which will depend on the specific application.

- Regardless of the strategy, evaluation processes should be efficient and lightweight to enable execution directly on the device while it operates.

- Synchronization: A strategy must be established to determine when the model is actively operating online and when it can engage in learning or tuning routines.

3.2. A TinyOL Linguistic Fuzzy Model

To illustrate the design concepts introduced in the previous subsection, we present a possible linguistic FRBS (Mamdani-type) model designed specifically for TinyOL, developed in accordance with the previously established guidelines and general considerations. Specifically, we opt for an adaptive system based on tuning the DB. This model will later be employed in the real-world scenario presented in Section 4.

In many real-world applications where linguistic FRBS are used for control, the operating conditions may evolve gradually over time due to smooth, non-abrupt changes in the environment. In such scenarios, and as long as these changes affect only the meaning of the linguistic terms rather than the structure of the RB, the system can be effectively updated through tuning of the linguistic terms, that is, by adjusting their associated membership functions. This form of adaptation, also known as DB tuning of linguistic FRBS, has traditionally been employed to improve accuracy under static conditions [94], but it has never been explored as a mechanism for online adaptation in dynamic environments where the semantics of the linguistic terms themselves evolve.

Classical approaches to DB tuning can be broadly categorized into two main families:

- Free-form tuning, in which the shape of each membership function is adjusted without explicit semantic constraints.

- Structured tuning, of one of the two following:

- 2-tuple linguistic tuning, where only the central position of each term is modified, preserving the original shape and width alternatives [95]

- 3-tuple linguistic tuning, which adjusts both the position and the width of the membership functions [96]

The 2-tuple and 3-tuple approaches rely on a reduced number of parameters, thus preserving the interpretability and semantic coherence of the linguistic terms more effectively than free-form tuning. Although they offer fewer degrees of freedom, they are generally preferable when interpretability is a requirement, and particularly well suited to TinyML scenarios, where computational and memory resources are constrained.

Note that if the evolution of the operating conditions were to imply changes that affect the RB rather than only the linguistic terms (stored in the DB), a different class of adaptive strategies would be required. Addressing this scenario lies beyond the scope of the present work and is outlined in the future work of the Section 5.

The illustrative model proposed consists, in summary, of a compact highly interpretable linguistic FRBS for control or regression capable of adapting its DB online, i.e., autonomously adjusting the linguistic partitions of its variables. The model also includes a synchronization mechanism that employs a short time period for the fuzzy system inference and a longer period for DB tuning. The remainder of this section provides a detailed description of this proposal.

To achieve model compactness, the following techniques are employed:

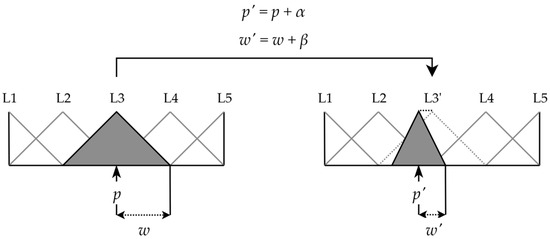

- Symmetrical triangular linguistic labels: These labels are defined using only two parameters by employing the 3-tuple linguistic model [96], which reduces complexity while preserving sufficient degrees of freedom, unlike a single-parameter model. The 3-tuple model minimizes computational requirements and storage needs, making it suitable for IoT devices. Exceptions are the two extreme labels, which are asymmetric for expressiveness. Figure 5 illustrates how the label L3 shifts both its position () and width (). The newly introduced label L3′ is denoted as the 3-tuple (L3, α, β), where α is the lateral displacement and β is the amplitude variation.

- Pointwise fuzzification [97] to simplify computations during the inference phase.

- Minimum T-norm for matching and inference and weighted average method (also known as the weighted mean of maxima or the height method) for defuzzification in FITA (First Infer, Then Aggregate, or Mode B) [97]. Its formula is:

Figure 5.

Symmetrical linguistic labels defined by position () and width () parameters based on the 3-tuple model. Dotted lines illustrate label variations: the gray line shows the original label, while the black line indicates the applied displacement α.

The computational complexity associated with the design of FRBSs lies primarily in the generation and tuning of the Knowledge Base. Literature offers several strategies to tackle this challenge, which can broadly be classified into:

- Gradient-based Learning Approaches (Neuro-Fuzzy Systems—NFS): These models have demonstrated significant performance in the literature [98]. By leveraging gradient-descent-based algorithms to optimize parameters in an online or offline fashion, they often provide faster convergence. Nevertheless, their reliance on local gradient information can lead to suboptimal solutions when trapped in local minimum.

- Evolutionary Approaches (Genetic Fuzzy Systems—GFS): These methods have also been extensively studied [90]. They employ bio-inspired algorithms to perform parameter search, offering strong exploratory capabilities that help avoid local optima. However, this advantage typically comes at the cost of sometimes increased computational time.

Considering these aspects, both families of methods can be employed to build FRBSs. However, the evolutionary strategy is particularly suitable in this case. This choice is supported by several facts:

- Evolutionary algorithms offer a strong advantage due to their population-based search and stochastic operators enable effective exploration of complex and poorly structured search spaces, reducing the likelihood of becoming trapped in local minimum. The literature consistently highlights this exploratory capability as a key reason for their success in optimization-driven learning tasks [90,99].

- Genetic algorithms do not depend strongly on the initial search point, unlike gradient-based methods, which are highly sensitive to initialization and can easily converge to suboptimal solutions. This robustness is well documented in the classical evolutionary computation literature [100,101].

- Linguistic (Mamdani-type) fuzzy systems are not easily differentiable, unlike TSK fuzzy models [102], where gradient-based learning is feasible because consequents are linear functions, the output is differentiable, and the error surface is smooth [103]. In contrast, linguistic fuzzy systems often involve non-differentiable inference mechanisms, such as triangular membership functions and in our case Minimum T-norm, making gradient-based tuning unsuitable [104,105].

- They allow straightforward implementation on low-resource devices, as genetic algorithms can operate efficiently under severe computational and memory constraints when the parameter space is compact, making them well suited for TinyML-oriented on-device adaptation.

Given the objective of enabling the FRBS to update its KB to maintain or improve accuracy in response to changes in the application environment, the proposed online learning or tuning mechanism focuses on DB tuning, a well-known and effective strategy [90]. This involves starting with an initial DB, which evolves as the system operates, and a predefined RB that remains fixed. This predefined RB can be learned beforehand, either from examples or via expert knowledge.

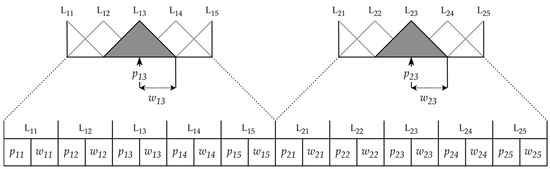

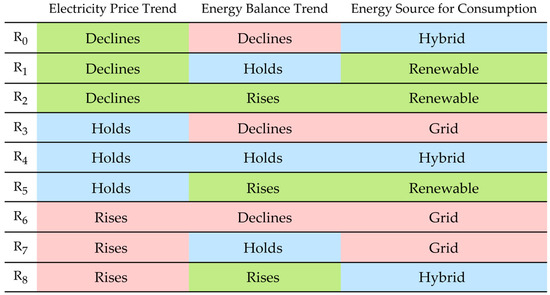

The tuning mechanism uses an evolutionary metaheuristic search [90], whose chromosome structure is illustrated in Figure 6. The parameters being adjusted correspond to the position () and width () of each linguistic label () associated with each variable () and label (), following the recommendations in Section 3.1 for using models with fewer parameters.

Figure 6.

Chromosome encoding of a 3-tuple DB with three variables.

To make the search and evaluation mechanism efficient and suitable for resource-constrained devices, the following resources are utilized:

- Parameter discretization: The search space is reduced by discretizing parameters instead of using continuous values. For instance, linguistic labels can shift or change width in discrete steps.

- Range constraints: Parameter ranges are bounded. Specifically, labels can have limited lateral shifts and constrained width changes.

- Universe of discourse reduction: The range of each variable is restricted to relevant values, minimizing unnecessary extremes.

- Micro Genetic Algorithms (μGAs) [106] strategies: Populations composed of few individuals, periodic restarts, and high selective pressure practices to favor rapid convergence.

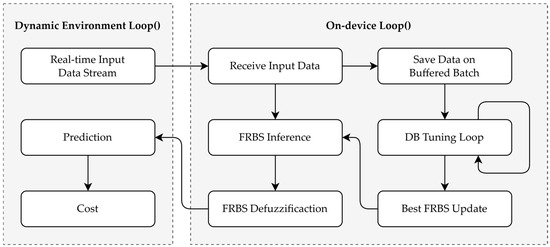

The evaluation and synchronization mechanisms depend more on the specific application than on the model itself. The proposed TinyOL Linguistic Fuzzy model can employ any of the three evaluation strategies (real environment, exact simulation or surrogate model) described in Section 3.1, depending on the application’s requirements. Similarly, strategies for updating the DB, including periodicity, must align with the application’s characteristics. In general, for evaluation using exact simulation or a surrogate model, DB tuning is performed incrementally online over time. Evaluation during the tuning phase uses a finite, recent window of data stored in a continuously updated buffer.

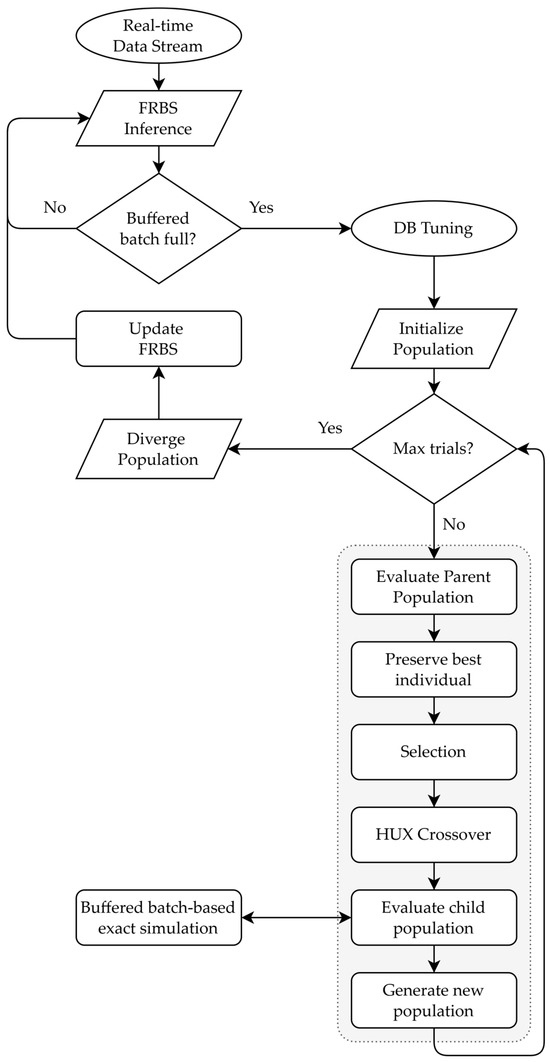

Figure 7 illustrates the functional components of the proposed TinyOL Linguistic Fuzzy model, the interactions among them, and their role within the online-learning pipeline. Two synchronous main loops operate in parallel. The dynamic-environment loop continuously generates input data, sends it to the device, receives the model’s prediction, and evaluates the decision cost. Concurrently, each time the device acquires a new data element, the FRBS processes it to produce a response to the environment. The same data element is also stored in a buffered batch that triggers the DB tuning procedure once the buffer is full, updating the FRBS parameters with the newly optimized values.

Figure 7.

Flow diagram of the proposed TinyOL Linguistic Fuzzy model.

Figure 8 illustrates the workflow of the proposed TinyOL Linguistic Fuzzy model. Incoming data streams are continuously monitored, with a sliding window used to buffer recent observations. During normal operation, the system performs real-time inference on new data using the current model, producing immediate results. Simultaneously, buffered data are periodically used in the evaluation of the learning algorithm. In this phase, the system finetunes the DB parameters encoded in chromosomes () to optimize performance. During the tuning phase, the RB remains fixed. The RB consists of fuzzy rules of the form , where denotes the -th input variable used in rule , is its associated linguistic term, and represents the linguistic output label of the rule. Keeping the RB structure static, as is standard in linguistic fuzzy system tuning, preserves interpretability and constrains the number of parameters, while allowing the DB parameters to be efficiently optimized during adaptation. Once the tuning is complete, the updated model resumes real-time inference, incorporating the learned adjustments into its predictions. This cycle enables the system to maintain accurate predictions in dynamic conditions while minimizing computational overhead.

Figure 8.

Diagram of the proposed TinyOL Linguistic Fuzzy model.

Finally, it should be noted that in a practical IoT deployment, several external factors may influence the behavior of the system, such as sensor noise, temporary communication interruptions, or fluctuations in available power. Linguistic FRBSs have the ability to mitigate the impact of noisy or unstable measurements due to their tolerance to imprecision and smooth membership functions. Moreover, because the TinyOL model operates entirely on-device, it can continue to provide decisions autonomously even when communication is unavailable, with the only possible drawback being the lack of updates of remote data that it may need, depending on the application, but it will still continue to operate with the latest data received. Lastly, because both inference and online tuning have very low computational and energy requirements, the adaptive mechanism can be executed reliably even under constrained power conditions. The tuning step is lightweight enough to run without affecting the normal operation of the device or exceeding the energy budget typically available in TinyML platforms. Although power consumption during the adjustment phase can be kept very low if the system remains compact, as indicated in Section 3.1, it might be considered that it should only be executed when sufficient power resources are available, i.e., that it could be postponed.

The following section illustrates how this TinyOL Linguistic Fuzzy model can be applied in practice.

4. Case Study: TinyOL Linguistic Fuzzy Model for Energy Management

A TinyOL Linguistic Fuzzy model, suitable for EC and IoT devices, could be relevant for a wide range of domains. In this work, we present as an example an energy source management system for renewable energy installations in homes equipped with photovoltaic systems (composed of solar panels and energy storage through batteries) that are not isolated, i.e., connected to the power grid. The purpose of this example is therefore to illustrate, through a potential real-world scenario, an online adaptive TinyOL Linguistic Fuzzy model, such as the previously presented in Section 3, in comparison with the same model using TinyML (with static tuning).

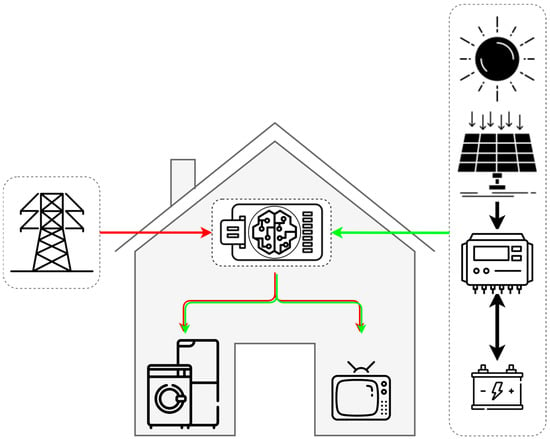

The aim of the system is to determine the optimal proportion of renewable energy and conventional energy from the grid to be consumed at any given time to optimize the electricity bill cost for the household user in countries such as Spain, where electricity prices fluctuate by day and hour, and are determined the day before. Figure 9 depicts the simulated experimental setup, where the device that contains the model receives input on the available energy sources and decides which one to use in order to meet the current consumption demands.

Figure 9.

Simulated experimental setup. Arrows indicate energy sources for consumption: green represents renewable energy, and red represents conventional energy drawn from the grid.

This application is particularly interesting, as it intentionally focuses on sustainability by employing a small set of batteries rather than a large-capacity setup. Batteries are not only the most expensive component of the installation but also occupy considerable space, weigh heavily (requiring specific structural considerations in the home) and are subject to wear, necessitating periodic replacement. Moreover, replacing them generates chemical waste that requires costly processing. On the other hand, while the computational system in this specific application does not impose stringent energy consumption constraints, it is deliberately implemented on a resource-limited device for EC environments to demonstrate feasibility.

This type of energy management application aligns with a growing body of research on intelligent energy management in residential settings. Recent studies have explored optimization frameworks for smart homes that integrate photovoltaic storage, electric vehicle charging, and demand response to enhance efficiency and reduce costs [107,108]. Artificial intelligence and adaptive control strategies have also been applied to optimize energy consumption and system reliability in both on-grid renewable energy systems and smart buildings [109,110,111]. These works underline the practical relevance of lightweight, adaptive models like the TinyOL Linguistic Fuzzy approach presented here, demonstrating that resource-constrained devices can effectively contribute to sustainable, cost-efficient energy management.

4.1. Proposed Model Description

In the proposed system, decisions regarding the proportion of the sources of consumed energy (renewable through solar panels and batteries or from the grid) are made based on the following data: the expected energy consumption in the household over the next 24 h, the renewable energy available in the batteries, the expected solar radiation based on weather forecasts, and the cost of grid electricity, which can fluctuate hourly according to a day-ahead auction, as observed in countries like Spain. For example, if sufficient renewable energy is available from the solar panels at a given time, the expected household consumption is low, and the grid electricity cost is high for that time slot, it would be preferable to use renewable energy.

The decision-making mechanism is implemented via an FRBS, which makes new decisions every hour of the day. This time interval was chosen mainly because, as shown in Table 2, while shorter intervals allow finer control and responsiveness, the one-hour interval offers a practical trade-off aligned with electricity tariff stability and computational efficiency.

Table 2.

Decision time and computational cost trade-off.

The aforementioned data is merged into the following two input variables for the FRBS to ensure a compact system:

- Electricity Price Trend (EPT): This variable allows the system to predict whether the price will rise, hold steady or decline over the next 24 h. It is calculated as the slope of the linear regression line that best fits the price data recorded over the preceding 24-h window.

- Energy Balance Trend (EBT): This variable merges the data corresponding to the expected energy consumption, the expected solar radiation and the amount of renewable energy stored in the batteries. In this way, the energy balance, normalized between −1 and 1, indicates whether the current energy demand can be met using renewable energy. A value of −1 represents a scenario in which no renewable energy is available, either stored or from solar radiation, meaning that the total energy demand must be covered by the conventional power grid. A value of 0 indicates that the renewable energy available at a given moment is exactly equal to the current household consumption. Conversely, values closer to 1 indicate an excess of renewable energy after meeting consumption needs. To account for the temporal evolution of this variable, the EBT is defined as the slope of the linear regression that best fits the energy balance values recorded over the previous 24-h period. This allows the system to predict whether the EBT will rise, hold steady or decline within a normalized range from 0 to 100. In this scale, a value of 0 represents a future scenario with lower energy balance values, indicating a decrease in the proportion of renewable energy relative to consumption. A value of 50 implies that the balance between renewable energy availability and expected energy consumption will remain stable. Finally, values approaching 100 suggest an increase in the availability of renewable energy to meet consumption, thereby reducing dependence on the conventional power grid.

Finally, the fuzzy system’s output will be denoted as the Energy Source for Consumption (ESC), which is defined as the proportion of renewable and grid energy to be used for covering the expected consumption. Its discourse universe is defined between 0 and 100, where 0 indicates covering 100% of consumption with renewable energy, 50 indicates splitting the consumption equally between renewable and grid energy, and 100 indicates covering 100% of consumption with grid energy.

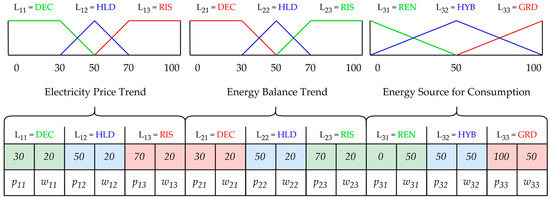

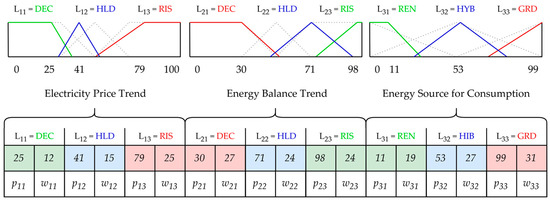

Regarding the KB of the FRBS, the structure is deliberately compact: each of the two input variables and the output variable is represented using three linguistic labels, yielding a total of nine possible rules. The universes of discourse for all variables are normalized and discretized over the interval [0–100] to regulate and structure the optimization search space. Rather than permitting unconstrained continuous variation, the linguistic labels are allowed to modify their position and width only through discrete steps within this range. This approach improves interpretability and aligns with the way domain specialists conventionally describe these variables in percentage terms rather than as absolute quantities. For the input variables, the labels “DEC”, “HLD”, and “RIS” denote if the values tend to “decline”, “hold”, and “rise”, respectively. For the output variable, the labels “REN,” “HYB,” and “GRD” correspond to “renewable”, “hybrid”, and “grid” energy source for consumption. Figure 10 illustrates these linguistic terms constituting the DB of the FRBS, together with the chromosome representation determined by the position and width of each label. The initial parameter values were established using expert knowledge.

Figure 10.

Diagram of the DB of the FRBS, where Electricity Price Trend and Energy Balance Trend represent the fuzzy input variables, and Energy Source for Consumption represent the fuzzy output variable. Colors indicate the correspondence between each linguistic label () of variable and label , and the position () and width () parameters that define it in the chromosome encoding.

The RB consist of rules defined by an expert, such as: “If the Electricity Price Trend for the upcoming hours is estimated to decline (indicating that the current price is higher than the upcoming hours price) and the Energy Balance Trend is estimated to rise (suggesting an increase in future renewable energy availability), then, the decision will favor maximizing renewable as Energy Source for Consumption (since the electricity price will decline and the renewable energy will rise)”. Figure 11 illustrates the nine rules that define the RB, ensuring complete coverage of the universe of discourse.

Figure 11.

Table of the RB of the FRBS, constructed to provide complete coverage of the universe of discourse. Colors indicate the efficiency level of each linguistic label: green for the most favorable in minimizing consumption costs, blue for intermediate efficiency, and red for the least desirable situation for cost optimization.

In accordance with the scheme outlined in Section 3.2, the system alternates between inference phases using the FRBS, during which decisions are made, and real-time DB tuning phases to address changes in the environment, such as variability among the potential household consumption patterns between weekdays and weekends. BD’s parameters fine-tuning is performed, for example, using an evolutionary algorithm implemented directly on the device. The aim of this process is to optimize the FRBS’s responses so that, given specific environmental conditions as input, the system produces the most appropriate decision to minimize energy costs.

The aforementioned tuning process has been designed using a bio-inspired metaheuristic that allows for real-time FRBS updates in a lightweight manner. Specifically, the CHC genetic algorithm has been selected, as it provides an effective balance between exploration and exploitation of the search space; moreover, it also provides a good basis to be complemented with μGAs strategies. To simplify the number of parameters to tune, a gene encoding based on the 3-tuple representation [96] of the fuzzy system has been adopted. This representation uses one parameter for the label position and another for its width, thereby maintaining symmetry. Consequently, the chromosome comprises only 18 genes for the three variables of the system. The search space for these 18 parameters is limited, as the discourse universe has been normalized between 0 and 100. Additionally, possible values have been discretized, significantly reducing the search space.

The evolutionary algorithm’s population consists of only 10 chromosomes, which undergo crossover and evolve until just 100 trials are completed in each evolutionary run. To prevent premature convergence of the population, the model implements an incest prevention mechanism, with a crossover threshold set to a quarter of the number of genes. That is, at least 25% of the genes between two chromosomes must differ for crossover to occur. The HUX crossover operator is used, which exchanges genes between two parents to generate two offspring. Each offspring randomly inherits a gene from each parent with equal probability.

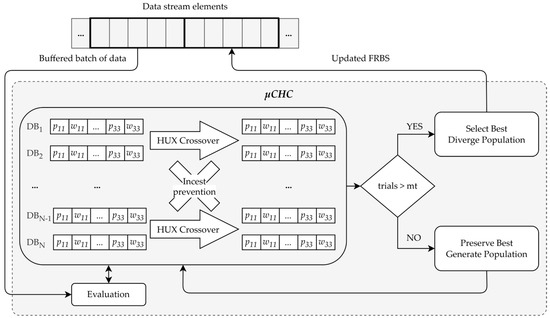

The real-time adaptation phase of the FRBS typically requires an incremental tuning mechanism, as resource-constrained devices are not capable of storing the entire growing dataset (which increases daily as new data is generated). To address this issue, a novel variant of the CHC genetic algorithm tailored for on-device online learning environments (μCHC) is proposed. This variant introduces two main modifications:

- Iteratively Partial Executions on Buffered Data Batches: Since it is not feasible to execute the full algorithm on the entire dataset due to memory constraints, the algorithm is applied iteratively on smaller, buffered batches of data generated in real time. These batches temporarily store data generated during the previous 24 h in the device’s memory. The data window shifts daily, forming a new buffered batch to update the model in the next partial execution of the evolutionary algorithm.

- Incremental Tuning through Implicit Restart: In order to make the tuning process incremental, the traditional restart mechanism of the CHC algorithm, which is triggered when chromosome similarity exceeds a predefined threshold, is replaced by an implicit restart. In this approach, each partial execution of the evolutionary algorithm begins by selecting the best-performing chromosome from the previous execution. This chromosome serves as the seed for the next run, enabling the model to adjust incrementally over time. Although the partial executions are not extensive enough to converge, they are sufficient to enhance accuracy as the model adapts to new data. To prevent the algorithm from converging after several partial executions, the rest of the initial population in each execution is initialized with random values consistent with each gene, thereby introducing diversity into the search process.

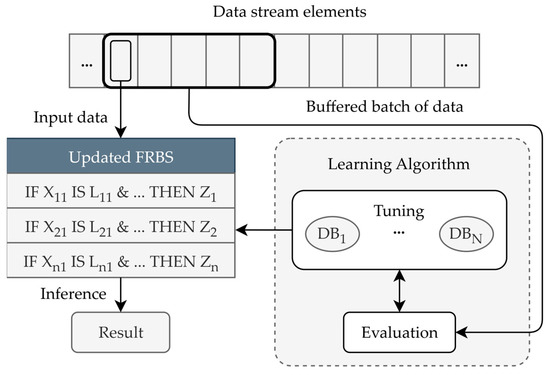

Figure 12 provides a detailed diagram of the novel incremental online tuning mechanism proposed: Data streams continuously into the device. Every 24 h, data instances form a buffered data batch, which is used to evaluate various models during each partial execution of the evolutionary tuning process. The model corresponding to the best chromosome is selected to infer decisions for the next 24-h data window while also serving as the seed for the tuning process on the new buffered batch in the subsequent execution.

Figure 12.

Diagram of the proposed μCHC.

The pseudocode of the μCHC algorithm is expressed in Algorithm 1.

| Algorithm 1. μCHC |

Input: L: chromosome length; p: population size; d: difference threshold; mt: max. trials

|

The continuous tuning of the FRBS is made possible through the rapid evaluation of chromosomes, enabled by an exact simulation of the experimental environment (a concept introduced in Section 3.1) specifically designed for this purpose. This simulator allows the tuning algorithm to optimize the FRBS decisions in real time.

Figure 13 presents the flow diagram of the proposed incremental evolutionary DB tuning method within the overall model framework. The diagram depicts the continuous on-device operational cycle, which alternates between performing inference on each incoming instance and executing tuning procedures on buffered batches of data.

Figure 13.

Flow diagram of the model including μCHC.

4.2. Hardware Implementation of the Proposed Model

To demonstrate the functionality of the proposed system under real-world conditions on a current resource-constrained device, a study was conducted on a subset of affordable IoT devices suitable for such applications, including some of the most well-known options. Table 3 presents the specifications of the most representative devices.

Table 3.

IoT devices specifications.

From these, the Arduino Nano 33 BLE Sense was chosen due to its compatibility with the widely known Arduino development environment. Although it is one of the most modest devices in terms of main memory and CPU frequency, it is still capable of implementing the entire system described. This Arduino model is equipped with a Nordic Semiconductor nRF52840 microcontroller, featuring a 32-bit ARM Cortex-M4F core. Figure 14 illustrates its main components.

Figure 14.

Arduino Nano 33 BLE Sense.

4.3. Experimental Platform Configuration

During the tuning phase, an exact simulation mechanism was implemented to evaluate the cost associated with each DB. This mechanism does not rely on external simulation software; instead, it is executed directly on the device to assess the decisions produced by each chromosome over the buffered batch of real data. The simulation mechanism continuously updates the levels of renewable energy stored in the battery system, considering both consumed and generated energy based on solar radiation. Each day, the cost of conventional energy, solar radiation forecast data, the amount of renewable energy available, and the expected consumption are obtained.

From these inputs, the model evaluates the cost of decisions based on consumption. This enables the system to infer real-time decisions while continuously adjusting to environmental changes on the device itself, optimizing the cost of its decisions.

For validation on the device, no simulation software was employed. Instead, Python 3.10 scripts running on a host computer replayed real datasets as a chronological input stream to the Arduino Nano 33 BLE Sense, allowing the device to operate under realistic conditions. The TinyOL Linguistic Fuzzy system was fully implemented in C and executed on the microcontroller, ensuring that all membership-function computations, DB evaluation and decisions occurred physically on the device.

In real time, the device receives continuous updates from the following data sources: the electricity price, expressed in euros per kWh, is retrieved through the ESIOS API (https://api.esios.ree.es/ (accessed on 8 December 2025)), while household energy consumption data, expressed in kWh, is provided by the electricity distribution company (https://cecsa.oficinavirtual.sercide.com/followup-supply (accessed on 8 December 2025)). Additionally, average annual solar radiation data, expressed in Wh/m2 is periodically updated from the Andalusian Energy Agency service (https://www.agenciaandaluzadelaenergia.es/ (accessed on 8 December 2025)). These streams enable the system to maintain online learning on the device by incrementally updating its internal parameters as new observations arrive.

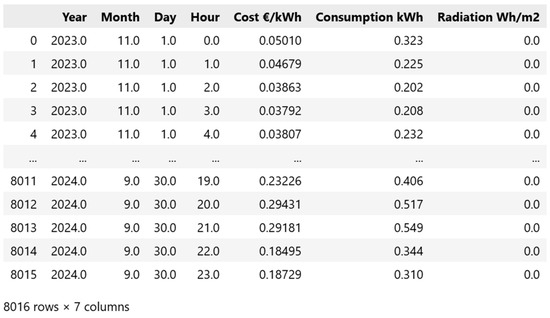

During the experimentation period, all data was collected coherently, ensuring consistency in terms of date and geolocation, which facilitates integration. The data collection period ranged from 1 November 2023 to 30 September 2024, resulting in a dataset of 8016 records defined by seven columns: hour, day, month, year, electricity cost (in €/kWh), household consumption (in kWh), and solar radiation (in Wh/m2). These records correspond to the province of Huelva, located in southwestern Spain.

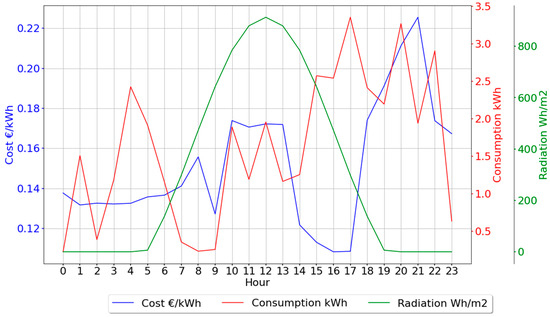

Figure 15 presents the pre-processed data in tabular format, indexed by date and time, ready for use in the simulation and training process. Figure 16 graphically represents a sample of the data used, corresponding to 24 h on 25 July 2024. The graph displays the variation in energy prices (blue), household consumption (red), and solar radiation intensity (green).

Figure 15.

Data used in the experimentation.

Figure 16.

Visualization of a data sample for a 24-h interval on 25 July 2024.

Based on the household consumption data shown in Table 4, analyzed hourly and daily, the simulator was found to work best with the following configuration: two solar panels with a total generation capacity of 1 kWh (500 Wh each) and a battery system with a total storage capacity of 5 kWh.

Table 4.

Consumption exploratory data analysis.

4.4. Result Analysis

To evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed approach, we compared the FRBS under both deployment paradigms: a static TinyML configuration and an adaptive TinyOL configuration that enables lightweight on-device updates. This distinction allows us to assess the behavior of the model when its parameters remain fixed versus when they evolve in response to incoming data. For contextual comparison, we also include the FRBS baseline, initialized as shown in Figure 10 and Figure 11. The performance results in terms of cost optimization and computational resource usage are presented and discussed throughout the remainder of this subsection.

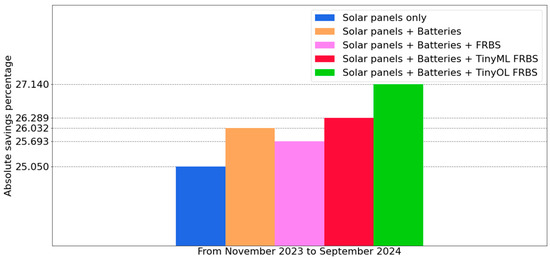

First, the total cost savings percentage was compared for the same household energy consumption using different systems. The results, depicted in Figure 17, show that, initially, incorporating solar panels into the household achieves a cost saving of 25% (represented in blue) compared to using only grid energy. Secondly, when a battery storage system is added, the savings slightly increase to 26% (represented in brown). Using a decision-making process managed by the initial static FRBS, cost savings reach 25.7% (represented in violet), which surpasses the system with panels but does not outperform the system with batteries. Fourth, the red bar represents the statically adjusted fuzzy model (TinyML-based), meaning it is adjusted only once at the beginning. Finally, managing renewable energy usage through the proposed online tuning mechanism (TinyOL-based) achieves a 27% cost saving (represented in green). The TinyOL model demonstrates better results than the static TinyML model, as the former adapts to changes occurring throughout the testing period.

Figure 17.

Total cost savings percentage.

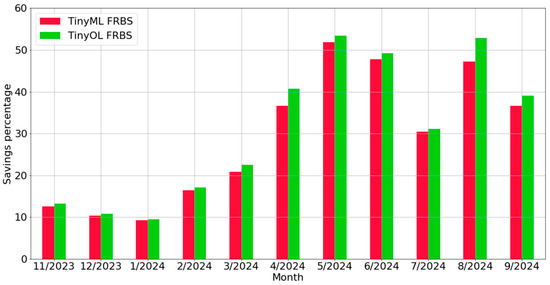

The impact of online tuning was further analyzed by comparing the monthly cost savings percentage between the static TinyML-based FRBS (represented in red) and the online adaptive TinyOL-based FRBS (represented in green) in Figure 18, month by month during the experimentation period. Notably, the improvement observed in month 8 is significant, as it includes a partial vacation period with a markedly different consumption profile due to sudden changes on two specific occasions. The adaptive model achieves significantly better results compared to the static system.

Figure 18.

Monthly cost savings percentage.

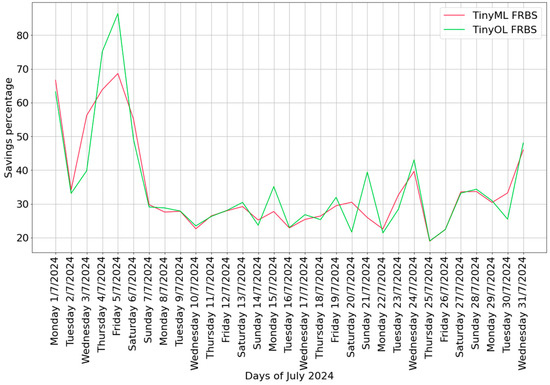

Focusing on a specific month, July 2024, Figure 19 illustrates that the system with the online adaptive FRBS, which adjusts daily using data from the previous day, achieves notable savings peaks on certain days (shown in green) compared to the static system (shown in red). For instance, this is evident on Friday, 5 July 2024. Moreover, variations were identified between high-consumption days, such as non-working days and working days. These behavioral changes influence the savings percentage achieved, with minimal peaks observed on Saturdays.

Figure 19.

Daily cost savings percentage during July 2024.

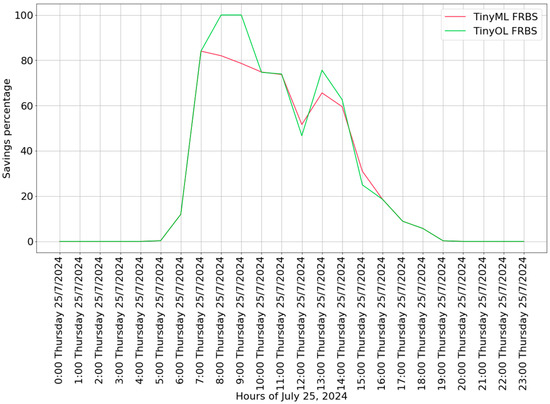

Finally, Figure 20 shows the impact of decisions made at each hour (the minimum unit available to evaluate the model’s performance). In this case, the online adaptive FRBS achieves better results during periods of high consumption and renewable energy availability (from 7 to 10 a.m. and 12 to 2 p.m.), where the FRBS’s decisions have greater weight.

Figure 20.

Hourly cost savings percentage.

Overall, accumulated gains of TinyOL FRBS compared to Tiny ML FRBS in terms of cost savings percentage is 1.17% from 1 November 2023 to 30 September 2024. Table 5 shows monthly cost savings percentage of TinyOL compared to TinyML, supplementing Figure 18. Similarly, Table 6 shows daily cost savings percentage, supplementing Figure 19, and Table 7 shows hourly cost savings percentage, supplementing Figure 20.

Table 5.

Monthly gains of TinyOL FRBS compared to Tiny ML FRBS in terms of cost savings percentage.

Table 6.

Daily gains of TinyOL FRBS compared to Tiny ML FRBS in terms of cost savings percentage in July 2024.

Table 7.

Hourly gains of TinyOL FRBS compared to Tiny ML FRBS in terms of cost savings percentage on Thursday 25 July 2024.

The proposed μCHC operates under a fixed number of trials. Let denote the number of fitness evaluations performed during one buffered batch. Since all selection and crossover operations are constant-time for a fixed population size, the total runtime is linear in the number of trials. Therefore, the time complexity is . In our implementation, each buffered batch uses trials.

The memory footprint is constant because both the population size (10 chromosomes) and the FRBS parameter dimensionality (17 parameters per chromosome) are fixed. The algorithm therefore requires storage for integer parameters, yielding a constant-space design. Formally, space complexity is .

Regarding the computational resource consumption of the model, global variables utilize 45,760 bytes out of the 262,144 bytes available in RAM, equivalent to only 17% of the total. Of this, 180 bytes are used to maintain the FRBS in memory (DB: 3 variables × 3 labels × 2 parameters × 4 bytes (int) + RB: 9 rules × 3 labels identifier × 4 bytes (int)), 288 bytes to store the daily buffered data batch (24 examples × 3 variables × 4 bytes (float)), and 680 bytes for the μCHC evolutionary algorithm’s population (10 chromosomes × 17 parameters × 4 bytes (int)).

In terms of processing speed, the time required for a partial tuning using the proposed evolutionary algorithm is 217 milliseconds. Specifically, the time taken to evaluate each chromosome on the buffered data batch is only 2 milliseconds, while inferring a decision using the FRBS each hour takes 0.03 milliseconds. To quantify the energy consumption of the model, a base power consumption of 0.125 W (5 V × 0.025 A) was considered. Therefore, the estimated energy required per inference is 3.75 μJ (0.03 ms × 0.125 W), whereas each partial tuning consumes approximately 27.1 mJ (217 ms × 0.125 W). These results demonstrate that an economic processor suitable for IoT tasks can efficiently implement the proposed compact model, supporting both low-energy inference and occasional tuning operations, and could even accommodate more frequent intervention intervals without significant energy overhead.

It is important to clarify that the purpose of this case study is to validate the behavior of the proposed adaptive mechanism under evolving operating conditions rather than to characterize long-term energy consumption patterns. The available dataset includes several phases where the underlying conditions change, providing controlled forms of concept drift that are sufficient for evaluating whether the system can adapt effectively. Accordingly, the experimental analysis focuses on the stability and responsiveness of the online tuning process, rather than on modelling extended temporal dynamics of energy consumption.

The results demonstrate that the proposed model for designing fuzzy systems at the edge with online tuning not only significantly improves cost savings by adjusting in real-time to changing environmental conditions, but also operates efficiently on low-resource IoT devices. The compact implementation of the selected evolutionary model, optimized for online learning environments, strikes an appropriate balance between accuracy and computational resource consumption, enabling continuous adjustment without compromising the device’s processing or memory capacity. Furthermore, the evaluation model based on a real-time exact simulator facilitates the rapid assessment of chromosomes, ensuring that the system can adapt efficiently within the required time frame.

The analysis using different measurement units (annual, monthly, daily and hourly) highlights that the online adaptive FRBS achieves greater cost savings in the selected application compared to a model that employs a static FRBS, adjusted only once during the design phase.

The resulting fuzzy DB as of 30 September 2024 is shown in Figure 21. For comparison, the initial FRBS, depicted in Figure 10, is overlaid using dotted gray lines.

Figure 21.

Diagram of the resulting DB of the FRBS on 30 September 2024. Colors indicate the correspondence between each linguistic label () of variable and label , and the position () and width () parameters that define it in the chromosome encoding.

Following the notion that rule-based models constitute transparent and intrinsically interpretable model systems [15,16,17,18,19,20,21], we quantify the interpretability of our fuzzy model using standard structural and semantic indicators commonly employed in interpretable FRBS design. First, the Rule-Base Complexity (RBC) [112] remains extremely compact, with only 9 rules and 2 antecedents per rule, which lies at the lower end of typical FRBS structures and enhances cognitive accessibility. Second, the Linguistic Label Compactness Index (LLCI) [113], based on the 18 parameters of the symmetric triangular labels, reflects the reduced parametric burden characteristic of highly interpretable fuzzy models. Third, the Membership Function Overlap Index (MFOI) [113] remains low (0.25 initially and 0.08 after online adaptation), indicating controlled overlap and low ambiguity between terms, values consistent with the range of high interpretability reported in the literature. Finally, to address the requirement that trustworthy AI systems maintain interpretability over time and avoid semantic drift, we compute a Semantic Stability Index (SSI) [114] of 0.87, showing that the linguistic meaning of the labels remains largely preserved after online tuning. Together, these indicators demonstrate that the proposed FRBS retains both structural transparency and semantic consistency throughout the learning process.

Overall, these results support the viability of the proposed model as an effective solution for online adjustment of the FRBS at the edge, laying the groundwork for future research on integrating adaptive learning techniques into IoT devices.

Beyond the specific scenario evaluated in this section, the proposed online-adaptive linguistic fuzzy approach presented in Section 3 exhibits strong potential for scalability across a wide range of application domains. Because the mechanism relies on incremental adaptation of interpretable fuzzy DB, it can be transferred to any context where systems must operate under non-stationary conditions using limited computational resources. This includes online calibration of embedded controllers, adaptive decision-making in autonomous robots, real-time sensor fusion in IoT monitoring networks, and evolving quality-assessment or anomaly-detection modules in industrial settings. The fact that the adaptation process only requires compact data buffers and lightweight evolutionary updates facilitates deployment in heterogeneous platforms, from microcontrollers to edge devices. These characteristics demonstrate that the proposed method is not restricted to the use case presented, but constitutes a general framework with broad universality and expansion potential.

5. Conclusions

Recent technological advances have enabled the incorporation of increasing levels of intelligence into resource-constrained devices, endowing them with the ability to learn and dynamically adapt to their surroundings. In this context and considering that fuzzy systems have historically been a key tool in such devices, particularly in applications such as control systems, due to their ability to provide a good balance between interpretability and precision, and low computational requirements, this work proposes an approach to extend fuzzy systems by adapting them to the Tiny Online Learning philosophy. Specifically, this approach allows linguistic fuzzy systems to learn online, adapting a part of their knowledge base in environments where conditions may change dynamically. To illustrate the feasibility of this idea, an online tuning mechanism that enables a linguistic fuzzy system to evolve continuously rather than remain static is proposed. This is achieved by dynamically adapting the definitions of its linguistic labels using optimized evolutionary metaheuristics, a micro genetic algorithm, to align with new environmental conditions without requiring complete retraining, and maintaining good semantic stability, as the data buffer used helps to avoid destroying previous knowledge or responding to changes that may only be temporary very quickly. Such an approach broadens the applicability of linguistic fuzzy systems to current TinyML and Edge AI scenarios, especially where high interpretability is required and only a low-power device is available.

Finally, as a practical application of a fuzzy system in a dynamic environment, a system aimed at optimizing the costs associated with energy consumption in households equipped with hybrid photovoltaic installations is proposed. The system manages the proportions of various energy sources to optimize profitability. The results demonstrate that the proposed model increases savings compared to the same model without online adaptation. Furthermore, the system has been shown to operate efficiently on low-resource hardware, using only 17% of the available RAM and achieving minimal processing times, close to real-time performance.

The limitation of this illustrative model, proposed to demonstrate that linguistic FRBSs can be used for online adaptation directly on a resource-constrained device, would arise when changing environmental conditions exceed what can be accommodated solely through the adjustment of linguistic terms. In such cases, a model capable of modifying its RB would be required. Moreover, a general limitation of this and any other online adaptive linguistic fuzzy system is that the knowledge base needed for proper operation in a given application may grow beyond what a resource-constrained device can support in terms of memory or computational performance, although such large knowledge bases would only be expected in very complex, and likely uncommon, applications.

Overall, the proposed approach contributes to the development of explainable and adaptive intelligence for resource-constrained devices, advancing the integration of fuzzy logic and evolutionary learning within the TinyML domain.

As a direction for future research, we plan to extend this study both by studying data buffer update policies to achieve a compromise between computational consumption and adaptive capacity, taking into account the past, but avoiding abrupt changes due to noise or other circumstances, and by supporting major changes in the environment that require adaptation not only of the linguistic concepts but also of the rule base itself.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.M.-M., F.A.M. and A.P.; methodology, J.M.-M.; software, J.M.-M.; validation, F.A.M.; formal analysis, J.M.-M.; investigation, J.M.-M.; resources, A.P.; data curation, J.M.-M.; writing—original draft preparation, J.M.-M. and F.A.M.; writing—review and editing, A.P. and A.M.R.; visualization, A.M.R.; supervision, A.P.; project administration, A.M.R.; funding acquisition, A.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities of Spain, grant number PID2023-150070NB-I00.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to privacy reasons.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations and notations are used in this manuscript:

| Abbreviations | |

| TinyML | Tiny Machine Learning |

| IoT | Internet of Things |

| EC | Edge Computing |

| FRBS | Fuzzy Rule-Based System |

| MCU | Microcontroller |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| ODL | On-Device Learning |

| TinyOL | TinyML with Online Learning |

| HW | Hardware |

| SoC | System-on-a-Chip |

| CPU | Central Processing Unit |

| GPU | Graphics Processing Unit |

| TPU | Tensor Processing Unit |

| FPGA | Field-Programmable Gate Array |

| EFS | Evolving Fuzzy System |

| RB | Rule Base |

| KB | Knowledge Base |

| DB | Data Base |

| NFS | Neuro-Fuzzy System |

| GFS | Genetic Fuzzy System |

| μGA | Micro Genetic Algorithm |

| EPT | Electricity Price Trend |

| EBT | Energy Balance Trend |

| ESC | Energy Source for Consumption |

| DEC | Linguistic input label representing a “decline” trend |

| HLD | Linguistic input label representing a “hold” trend |

| RIS | Linguistic input label representing a “rise” trend |

| REN | Linguistic output label representing a “renewable” energy source |

| HYB | Linguistic output label representing a “hybrid” energy source |

| GRD | Linguistic output label representing a “grid” energy source |

| Notations | |

| Linguistic label of variable | |

| Position of linguistic label | |

| Width of linguistic label | |

| Lateral displacement of the position of linguistic label | |

| Amplitude variation of the width of linguistic label | |

| Predicted output of the model | |

| Matching degree of the rule | |

| Maximum value of consequent linguistic label from rule | |

| Fuzzy Data Base encoding as chromosome | |

| Difference threshold between two parent chromosomes | |

| Number of trials evaluated in the current partial execution of the genetic algorithm | |

| Maximum number of trials evaluated in each partial execution of the genetic algorithm | |

| Chromosome length of the genetic algorithm | |

| Population size of the genetic algorithm | |

| Current population of chromosomes of the genetic algorithm | |

| Current population of parent chromosomes of the genetic algorithm | |

| Current population of child chromosomes of the genetic algorithm | |

References

- Khan, T.; Tian, W.; Zhou, G.; Ilager, S.; Gong, M.; Buyya, R. Machine learning (ML)-centric resource management in cloud computing: A review and future directions. J. Netw. Comput. Appl. 2022, 204, 103405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, T.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, W.; Li, S.; Zhang, H. Edge computing for IoT: Novel insights from a comparative analysis of access control models. Comput. Netw. 2025, 270, 111468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Shami, A. IoT data analytics in dynamic environments: From an automated machine learning perspective. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2022, 116, 105366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malazi, H.T.; Chaudhry, S.R.; Kazmi, A.; Palade, A.; Cabrera, C.; White, G.; Clarke, S. Dynamic service placement in multi-access edge computing: A systematic literature review. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 32639–32688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srikanth, K.; Ungureanu, T. Organizational adaptation in dynamic environments: Disentangling the effects of how much to explore versus where to explore. Strat. Manag. J. 2025, 46, 19–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]