Abstract

Background: Artificial intelligence (AI) is increasingly shaping medical education through adaptive learning systems, simulations, and large language models. These tools can enhance knowledge retention, clinical reasoning, and feedback, while raising concerns related to equity, bias, and institutional readiness. Methods: This narrative review examined AI applications in medical and health-profession education. A structured search of PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science (2010–October 2025), supplemented by grey literature, identified empirical studies, reviews, and policy documents addressing AI-supported instruction, simulation, communication, procedural skills, assessment, or faculty development. Non-educational clinical AI studies were excluded. Results: AI facilitates personalized and interactive learning, improving clinical reasoning, communication practice, and simulation-based training. However, linguistic bias in Natural language processing (NLP) tools may disadvantage non-native English speakers, and limited digital infrastructure hinders adoption in rural or low-resource settings. When designed inclusively, AI can amplify accessibility for learners with disabilities. Faculty and students commonly report low confidence and infrequent use of AI tools, yet most support structured training to build competence. Conclusions: AI can shift medical education toward more adaptive, learner-centered models. Effective adoption requires addressing bias, ensuring equitable access, strengthening infrastructure, and supporting faculty development. Clear governance policies are essential for safe and ethical integration.

1. Introduction

Artificial Intelligence (AI) has begun to significantly influence various fields, with medical education being a notable example. At its core, AI involves the replication of human cognitive functions such as learning, reasoning, and adapting by computer systems. Kaplan and Haenlein describe AI as the capacity to analyze external information and learn from it to accomplish particular objectives and actions [1]. The concept of applying AI in medicine dates to the 1970s, originally aimed at improving diagnostic and therapeutic processes. In recent years, rapid progress in AI technology has resulted in the creation of sophisticated systems capable of delivering diagnostic accuracy comparable to that of medical experts [2]. In the context of medical education, AI includes a wide array of tools and techniques such as machine learning (ML), natural language processing (NLP), deep learning, and more recently, generative AI models like large language models (LLMs), which are now being integrated into daily educational use [3].

Although AI has existed for decades, the recent emergence of ML and LLMs particularly those powering AI-driven chat tools like OpenAI’s ChatGPT has significantly increased the accessibility and usability of this technology. This shift has been described as so transformative that it may mark a clear distinction between the eras before and after the advent of ChatGPT [4]. Historically, medical education has relied on classroom instruction, cadaver-based anatomy learning, clinical rotations, and direct patient interactions as its foundational methods. The integration of AI into medical curricula introduces the capability for immediate assessment and feedback on student performance, enhancing the learning process in real time. AI also supports the creation of flexible, personalized, and interactive educational environments [5].

Unlike traditional learning tools such as textbooks and lectures, which often promote passive knowledge acquisition, AI technologies including virtual simulations, interactive clinical scenarios, and augmented reality (AR) foster active learning by immersing students in realistic yet safe training situations [6]. Recent developments in LLMs have further expanded these opportunities by enabling low-pressure, repeatable communication practice for history taking, empathy, and patient-centered dialogue [7]. Immersive AI-driven virtual patient systems have also been shown to improve learners’ clinical reasoning and communication performance, with students reporting increased confidence and skill in patient interactions [8]. Table 1 presents descriptions of simulation tools with educational use and evidence. Though this review focuses primarily on language-based, adaptive, and simulation-driven educational applications, emerging computer-vision approaches for procedural skill assessment are also briefly discussed.

Table 1.

Immersive AI-driven simulation tools and their educational impact in medical training.

Literature on AI in medical education is expanding; most existing reviews focus on isolated technologies such as virtual patients, simulation platforms, or LLM-generated feedback rather than offering a unified synthesis across modalities. Many earlier reviews were published before the rapid emergence of modern LLMs and therefore do not reflect their current educational impact. Others overlook crucial dimensions such as institutional preparedness, governance structures, and the broader pedagogical, ethical, and equity implications of AI adoption. In light of the rapid pace of technological change and the growing reliance on AI by both students and educators, an updated, integrative review is needed.

In response to this gap, the present review consolidates contemporary evidence on AI in medical education and examines its implications for learning, assessment, and equitable implementation. Specifically, we explore the following questions:

- Which AI technologies demonstrate solid evidence for enhancing knowledge acquisition, clinical reasoning, communication skills, and procedural performance?

- What challenges related to equity, accessibility, and language arise when AI tools are used by diverse learner populations?

- To what extent are faculty and institutions prepared to implement AI within medical curricula, and where do gaps in infrastructure or training remain?

- What ethical principles, governance structures, and policy frameworks are required to support safe, transparent, and responsible use of AI in medical education?

Although procedural-skill assessment is an important and expanding area of AI in medical education, it was not the primary focus of this review and is therefore discussed only briefly.

2. Materials and Methods

This paper presents a narrative review that compiles and interprets findings from peer-reviewed research, systematic reviews, and policy literature addressing the use of AI in medical education. The purpose of this work was to summarize and evaluate the available evidence on how AI technologies are transforming teaching, learning, and assessment practices across different levels of medical training.

A targeted search was conducted to identify publications available up to October 2025, capturing both early developments and the most recent applications of AI in educational contexts. The databases searched included PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science. To broaden coverage, Google Scholar was also queried to locate grey literature, including institutional guidelines, educational frameworks, and policy reports from professional bodies.

Search terms combined indexed vocabulary and free-text keywords linked with Boolean operators. Representative examples of search strings included:

(“artificial intelligence” OR “machine learning” OR “deep learning” OR “large language model*”).

AND (“medical education” OR “health professions education” OR “clinical training” OR “simulation” OR “virtual patient” OR “augmented reality” OR “virtual reality”).

AND (“medical student*” OR “resident*” OR “faculty development” OR “adaptive learning” OR “intelligent tutoring system*” OR “AI feedback”).

Only studies written in English were reviewed to ensure consistent interpretation. Reference lists from influential papers and recent reviews were also screened manually to locate any additional relevant literature. Grey literature, defined as information disseminated outside conventional peer-reviewed channels (e.g., policy papers, institutional reports, professional guidelines, and technical documents), was included when it contributed meaningful perspectives on ethical, institutional, or educational dimensions of AI implementation. In contrast, non-grey literature encompasses peer-reviewed journal articles, scholarly monographs, and other formally published academic sources, which constituted the primary evidentiary foundation of this review.

Studies were considered eligible for inclusion if they comprised empirical quantitative, qualitative, or mixed-methods research; systematic or narrative reviews; or official institutional and policy reports that examined AI in the context of medical or health-professions education. Eligible populations included undergraduate and postgraduate medical students, residents, and faculty members participating in AI-assisted learning or teaching. Studies were required to address at least one educational outcome, such as knowledge acquisition, diagnostic reasoning, communication, accessibility, ethical awareness, or faculty preparedness. Only publications written in English and released between 2010 and 2025 were reviewed, although seminal earlier works were retained when historically relevant. In contrast, studies were excluded if they focused solely on clinical or diagnostic AI applications without an educational component, lacked analytical depth (e.g., opinion pieces or commentaries), or duplicated material already discussed in more comprehensive reviews.

The reviewed material covered a broad spectrum of AI uses, including simulation-based training, intelligent tutoring systems, NLP, augmented and virtual reality (AR/VR), automated assessment tools, and faculty development programs (Table 2 provides a summary of selected AI-enabled educational tools and feedback models). These AI-supported learning strategies were contrasted with traditional teaching methods to evaluate their influence on knowledge gain, diagnostic reasoning, communication ability, accessibility, and ethical awareness.

Table 2.

Educational benefits of AI-driven virtual patients, feedback systems, and LLMs.

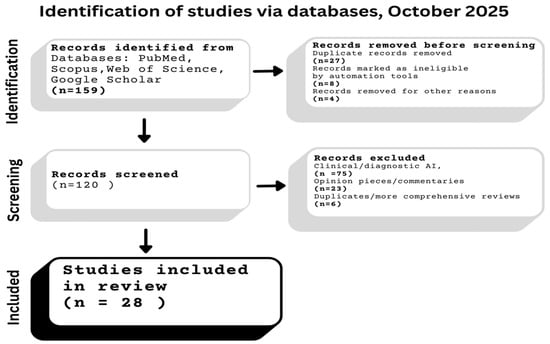

A thematic synthesis approach was employed to integrate both quantitative and qualitative evidence, highlighting recurring topics, strengths, and areas requiring further investigation. No formal risk-of-bias or quality assessment was conducted, as this review aimed to provide a broad synthesis of the available evidence rather than a quantitative evaluation; however, emphasis was placed on high-quality, peer-reviewed studies, large-scale reviews, and credible institutional reports to maintain reliability, relevance, and academic rigor. A PRISMA-style flow diagram (Figure 1) summarizes the identification, screening, eligibility assessment, and final inclusion of studies in this narrative review.

Figure 1.

PRISMA-style flow diagram of the study identification, screening, eligibility, and inclusion process.

3. Historical Background

The incorporation of computers into medical education began in the early 1970s. While computer-assisted learning offered notable benefits, its early adoption was gradual. Over time analysis was conducted for the initial phases of this transition and highlighted several barriers to its widespread use, including insufficient and inadequate technological infrastructure, resistance from educators, and doubts regarding its educational value. Over time, computer-assisted learning gained acceptance and is now an integral part of medical education, illustrating how new technologies often encounter initial skepticism before becoming standard practice [25]. Advancements such as simulation and VR further expanded instructional possibilities. Today, computer-assisted instruction, online learning platforms, simulation tools, and VR technologies are commonly used to enhance postgraduate medical training [26] (Figure 1 provides an overview of the evolution of AI technologies across decades).

A comparable pattern is emerging with the introduction of AI in medical education. Much like the early reception of computer-assisted learning, AI’s integration has been cautious, despite its clear potential. Factors such as concerns over accuracy, ethical considerations, educator readiness, and institutional capability have contributed to this hesitancy. Nonetheless, AI is steadily gaining momentum, driven by increased familiarity, advancements in AI capabilities, and growing empirical support. As medical institutions come to appreciate AI’s role in enabling personalized learning, improving assessment efficiency, and enhancing clinical reasoning, its adoption is expected to mirror the trajectory of earlier technologies from initial resistance to widespread use.

AI began to find its place in medicine during the early 21st century and has since experienced rapid growth. Its integration into medical education is prompting substantial changes in traditional curricula, particularly through the incorporation of computer-based decision support systems that are reshaping how clinical reasoning is taught [27].

In parallel, emerging technologies such as VR and AR are becoming more prevalent in educational settings. These tools ranging from virtual patient encounters and surgical simulations to interactive anatomy platforms provide immersive, hands-on learning experiences that enhance the quality of education and bridge the gap between theoretical instruction and real-world clinical applications [28].

VR is consistently associated with improved knowledge retention, procedural mastery, and student engagement due to its immersive design. It also facilitates safe clinical simulation for high-risk scenarios, often with dynamic feedback powered by AI. By contrast, AR provides real-time overlays of digital content onto clinical or educational contexts, which supports contextual learning and spatial understanding, particularly in anatomy and procedural guidance [29,30]. While AR increases engagement, its measurable educational outcomes are less consistent, with some studies showing modest or non-significant gains compared to traditional teaching [31]. Both VR and AR face limitations in terms of hardware, cost, and implementation complexity, but the evidence base suggests that VR currently demonstrates stronger outcomes for learning effectiveness, while AR offers practical advantages in contextual, real-world integration [32] (see Table 3. For a detailed comparison between VR and AR features, applications and limitations).

Table 3.

Comparison of VR vs. AR.

The role of AI in medical education is particularly transformative, moving learners away from passive instructional models like lectures and observational rotations toward more interactive and adaptive learning environments. A comprehensive review underscores that AI-powered adaptive platforms can tailor educational content based on continuous performance analysis, enabling real-time adjustments in difficulty to better support knowledge acquisition and clinical competency compared to uniform teaching approaches [5].

Moreover, generative AI technologies now facilitate active learning strategies such as pretesting and spaced retrieval. For instance, AI chatbots like ChatGPT allow students to engage with clinical questions by generating responses and receiving immediate feedback enhancing both memory retention and metacognitive development [33].

Taken together, these AI-driven advancements combine elements of active recall, adaptive learning structures, and simulation-based experiences to support a personalized, learner-centered educational model that aligns with the evolving requirements of contemporary medical practice.

4. Fundamentals of Artificial Intelligence

To make the most of ML technologies, students need to grasp both their capabilities and their boundaries. With AI tools becoming more integrated into everyday life, it is crucial to examine their current applications in medical education and identify the medical domains where these technologies could be effectively implemented. AI is fundamentally built on algorithms structured mathematical procedures that analyze data to generate useful results and training data, which consist of labeled or unlabeled datasets that enable these algorithms to learn patterns and make informed decisions. The success of ML in clinical and educational environments relies heavily on access to high-quality, accurately annotated data for training robust models, as well as a solid foundational knowledge of how these models operate [34].

Supervised learning depends on datasets where each input such as clinical images, diagnostic metrics, or student answers is linked to a corresponding known output, like a diagnosis or test score. Through this pairing, the algorithm learns to associate inputs with outputs, enabling it to make predictions or classifications on new, unfamiliar data. As highlighted in a foundational overview of supervised ML, this approach is designed with the intention to predict or classify an objective and remains the most widely applied technique in clinical contexts, particularly for diagnostics and prognosis. This capability holds promise for advancing diagnostic education tools [35].

Unlike supervised learning, unsupervised learning operates without predetermined output labels. Its primary aim is to uncover hidden patterns or groupings within the dataset. Evaluating the effectiveness of this method can be challenging, as its value is typically judged by how well the identified structures contribute to subsequent supervised learning tasks [36].

AI can influence medical education in three main roles: as a direct instructor providing educational content, as a supportive learning companion throughout the student’s academic progression, and as a facilitator that encourages peer interaction and problem-solving through guided feedback. Prominent examples of AI applications in this setting include chatbots, intelligent tutoring systems (ITSs), virtual patient simulations, and adaptive learning technologies [37].

Chatbots are AI-powered tools that utilize NLP to understand, interpret, and produce human language. Trained on extensive datasets, they are capable of accurately handling a wide range of user questions and retrieving relevant information efficiently [38]. Within medical education, chatbots are gaining traction as virtual tutors, aiding students in reviewing material, engaging in simulated patient dialogues, and accessing current clinical knowledge in real time.

Intelligent Tutoring Systems (ITS) are gaining attention for their capacity to revolutionize medical education by delivering adaptive and individualized learning experiences that closely resemble personalized instruction. These AI-based platforms are designed to replicate the advantages of a well-trained human tutor by understanding student responses and giving suitable feedback to prompt further explanation [39]. This adaptive interaction fosters deeper cognitive processing, enhances critical thinking, and delivers customized feedback aligned with each learner’s needs. Recent advancements, particularly those incorporating generative AI, demonstrate the potential of ITS to simulate authentic clinical environments and guide students through intricate diagnostic and problem-solving scenarios in real time [40]. In the context of medical education, these systems can support the development of clinical skills, diagnostic acumen, and ethical reasoning, all while adjusting to the learner’s progress.

Lastly, virtual patients are computer-based tools designed to simulate clinical encounters for the purposes of education, skill development, and evaluation [41]. They replicate key aspects of patient interactions such as medical history-taking, diagnostic processes, and treatment planning offering learners a robust environment to refine their clinical competencies. These simulations promote decision-making skills, expose students to a wide variety of clinical scenarios, and ensure consistent access to training regardless of patient availability. By delivering scalable, reproducible, and standardized experiences, virtual patients serve as a valuable complement to traditional bedside teaching, especially in situations where direct clinical exposure is constrained [42].

5. AI-Enhanced Teaching Techniques

AI is revolutionizing education by enhancing instructional methodologies, optimizing feedback mechanisms, and personalizing learning trajectories. From realistic patient simulations to adaptive tutoring systems and immersive training environments, AI-integrated platforms are significantly improving learning outcomes. This integration is not just transforming how students absorb content but also how educators assess performance and tailor instruction.

AI-enhanced simulation platforms, including intelligent mannequins and virtual patients, replicate complex human pathophysiology and respond dynamically to clinical interventions (examples of such adaptive tools are presented in Table 1). These tools go beyond static simulation by integrating sensors, machine learning algorithms, and predictive modeling to simulate patient deterioration, drug responses, or surgical complications. For example, AI-driven mannequins can alter cardiovascular or respiratory parameters based on trainee inputs, mimicking real-time patient reactions. This kind of immersive, experiential learning is invaluable for medical trainees, as it allows for repeated practice in a risk-free environment while cultivating clinical decision-making under pressure. In a study utilizing ChatGPT-assisted problem-based learning, students demonstrated significantly higher exam scores and clinical skills compared to peers in traditional training, suggesting that AI-enhanced learning not only improves knowledge retention but also practical competencies [43].

AR and VR systems offer immersive environments for procedural training, particularly in high-stakes disciplines such as surgery, emergency medicine, and anesthesiology. When augmented with AI, these platforms can assess learner behavior such as hand positioning, tool trajectory, or timing precision and adjust the complexity of scenarios accordingly. For instance, a VR simulation for laparoscopic surgery can introduce complications mid-procedure based on learner decisions, mimicking real-world unpredictability. AI also facilitates detailed performance analytics by identifying micro-errors (e.g., excessive tissue force or delayed reaction times) and summarizing them into actionable feedback. Although large-scale validation studies are still ongoing, early findings suggest such AI-AR/VR systems significantly improve procedural accuracy and long-term skill retention.

Generative AI tools are now being deployed to automate not just the grading of assessments but also the creation of exam content tailored to course objectives and student proficiency levels. These systems can generate multiple-choice questions, case studies, and even objective structured clinical examination (OSCE) scenarios. A recent review found that generative AI models, when guided by well-crafted prompts, could identify inconsistencies or ambiguities in test items and provide error-free alternatives, thus improving the overall validity of assessment [44]. AI can also personalize assessments by adapting question difficulty in real time based on student responses, supporting formative evaluation rather than merely summative testing.

NLP, particularly through advanced LLMs, is enabling highly scalable yet individualized feedback systems in medical education. These models can interpret student-written case analyses, histories, or reflections and generate nuanced, criterion-based feedback nearly indistinguishable from that of experienced educators. In a practical study conducted during a bioinformatics course at the University of Ljubljana, students rated AI-generated feedback delivered blindly alongside human feedback as equivalent in quality and usefulness. The LLMs also enabled faster turnaround times and reduced the workload for teaching staff, particularly in large-enrollment courses [45]. Notably, the success of these systems depends on robust prompt engineering and periodic validation against educational standards to prevent factual inaccuracies.

6. Integrative Analysis: Effectiveness of AI-Enhanced Learning Approaches

AI is reshaping medical education by combining simulation, adaptive feedback, and natural language interaction into cohesive learning environments. Across different fields, AI-based approaches generally outperform traditional teaching in short-term knowledge gain, confidence, and engagement, although questions remain about their long-term impact and generalizability. Current evidence suggests that the effectiveness of AI depends less on the type of technology used and more on instructional design, quality of feedback, and integration within the curriculum.

Simulation-based and metaverse-driven environments have demonstrated measurable improvements in procedural accuracy and clinical decision-making [46,47]. Studies incorporating real-time feedback and dynamic physiological responses report stronger learning outcomes than static modules, indicating that adaptive responsiveness rather than visual realism is the key driver of educational benefit. Nonetheless, most trials remain single-institutional and limited in sample size, which restricts the generalizability of findings. These results correspond with other high-fidelity simulations showing that contextual realism, timing of feedback, and structured debriefing are key determinants of educational value.

AI-supported communication training extends this principle to interpersonal skill development. Virtual patients and conversational agents can reproduce emotionally challenging scenarios such as breaking bad news or managing patient anxiety [48]. Compared with standardized patient sessions, they offer greater scalability and consistency but are less effective in reproducing emotional nuance and spontaneous empathy. Learners frequently report improved confidence and reduced anxiety when practicing with AI-based tools, yet faculty evaluations emphasize that genuine affective communication still requires guided reflection and human mentorship. Thus, AI serves best as a complement to traditional training, providing opportunities for repetition and exposure rather than replacing interpersonal feedback.

Adaptive learning and remediation systems powered by machine learning further illustrate this balance between automation and supervision. By continuously tracking learner performance, diagnostic accuracy, and decision-making trends, these platforms can identify knowledge gaps and deliver targeted remediation content [49]. However, without faculty involvement, automated feedback risks reinforcing superficial understanding or encouraging overreliance on algorithmic assessment. Studies consistently demonstrate that blended approaches, combining AI-generated analytics with expert debriefing, yield the most durable improvements in both competence and confidence.

Comparative analyses with traditional teaching reinforce these findings. A systematic review including nearly ten thousand participants, concluded that blended digital learning incorporating AI or simulation resulted in significantly higher knowledge outcomes than classroom-based instruction alone [50]. Virtual patient-based learning improved data gathering and diagnostic reasoning, though the effect on general problem-solving was smaller [48].

Several studies emphasize that AI-based digital tools encourage active learning, which enhances both retention and transfer of skills. Simulation-based VP learning fosters structured practice of case-specific reasoning tasks like data gathering and diagnostic formulation. A BMC review concluded that virtual patient tools notably improved clinical reasoning in areas such as diagnosis and information collection, though general problem-solving showed less consistent gains [13]. Meanwhile, a study comparing VP-based learning to recorded lectures in spinal trauma showed that virtual patients matched or exceeded lecture formats in both short-term and long-term retention, and learners reported higher engagement and understanding [51]. Together, these findings indicate that AI-enabled simulations can support durable knowledge retention and effective transferability, especially for clinical reasoning tasks where contextual decision-making matters.

AI-supported learning modalities generally promote higher student engagement and satisfaction than traditional methods. A systematic review of simulation-based learning reported that approximately 71% of students were satisfied or very satisfied, highlighting perceived value for skill implementation despite accessibility and resource constraints [52]. Students often describe AI-assisted learning as more engaging and accessible, while educators emphasize advantages in standardization, feedback, and cost efficiency. At the same time, the educational effect size of virtual patient tools varies depending on interactivity and reflective design, underscoring that thoughtful pedagogical integration and reliable digital infrastructure remain more important than the novelty of the technology itself [13]. In contrast, traditional SPs are effective for communication and empathy training but are resource- and labor-intensive. In summary, AI-assisted platforms support greater accessibility and scalability than traditional formats, though quality depends on thoughtful design and infrastructure.

Beyond communication, diagnostic reasoning, and adaptive learning, artificial intelligence is increasingly applied to the assessment of procedural and psychomotor skills.

It is important to note that although procedural-skill assessment represents a significant and rapidly expanding area of AI in medical education, it was not the primary focus of this review and is therefore discussed only briefly within the broader synthesis.

Computer-vision-based systems can analyze components such as body posture, instrument-handling movements , and instrument trajectories to generate objective, real-time feedback on technical performance [53]. In basic life-support training, AI-driven CPR feedback platforms record compression depth, rate, and hand placement, helping learners achieve guideline-consistent technique and improved retention compared with traditional instructor evaluation [54]. Similar machine learning models have been implemented in laparoscopic and robotic surgery, where they automatically detect errors, quantify motion efficiency, and classify operator skills with high sensitivity [55]. These systems complement traditional faculty assessment by reducing subjectivity and providing standardized, data-driven feedback [56]. Collectively, such applications extend the role of AI beyond cognitive training and simulation, bridging technical-skill education with measurable clinical performance.

7. Challenges, Limitations, and Risk Management

Despite its transformative potential, the integration of AI into medical education is accompanied by significant limitations and challenges. Key concerns include infrastructural and technical barriers, particularly in low-resource settings where limited access to digital tools and stable internet hinders equitable AI adoption [57,58]. Another key challenge is the lack of real life interpersonal and communication skills crucial in-patient care, which would be present in a typical clinical setting. Figure 2 illustrates student and resident perceptions of AI’s current role and limitations in medical education. Faculty resistance and lack of institutional readiness remain prominent issues, with many educators requiring substantial training to effectively incorporate AI into curricula. According to Naseer et al. [59], at one institution, most of the respondents in the study want to learn more about AI incorporation in learning, as well as teaching; however, most of the study participants are not convinced about their abilities in implementing AI into those two processes. Additionally, as using AI in learning is relatively new to both educators and students, it is complicated to assess the reliability of it in all cases, and the potential differences in the students’ academic performance before the implementation of AI compared to prior learning [58].

Figure 2.

Timeline of AI evolution throughout the years.

Ethical and legal concerns, such as breaches of data privacy, lack of informed consent, and inherent algorithmic bias affecting its decision making, also highlight the critical challenges to the responsible implementation of AI in medical education [5]. Excessive dependence on AI tools in educational contexts can hinder the development of essential cognitive skills. Students may be inclined to accept AI-generated outputs without critically assessing their accuracy or relevance, particularly when they find it difficult to evaluate the reliability of the information. This tendency to rely on automated responses as a shortcut may ultimately diminish important abilities such as analytical thinking, independent judgment, and effective decision making [60].

Although numerous studies indicate that AI-assisted learning approaches can boost short-term educational outcomes such as exam scores, immediate retention of knowledge, and learner engagement, the evidence regarding their long-term effects is scarce. Only a handful of studies have investigated whether the advantages gained from AI-supported instruction persist over time or translate into measurable clinical competence. A recent systematic review examining AI in health-profession education found that nearly all studies focused on short-term outcomes, with none following participants beyond six months or evaluating performance in real-world clinical settings [61]. Similarly, a meta-analysis of virtual patient simulations reported clear improvements in short-term diagnostic reasoning but lacked data linking these interventions to subsequent clinical practice or patient outcomes [11].

Some emerging longitudinal data from adjacent areas suggest that repeated exposure to adaptive or simulation-based technologies may improve knowledge retention and procedural confidence compared with traditional teaching methods. For instance, Ansquer et al. [62] showed that while the benefits of simulation-based procedural training for emergency physicians gradually declined, they remained significantly above baseline several months after the intervention. Although these results are not specific to AI, they offer insight into how sustained engagement with technology-assisted learning could affect long-term competence. Nonetheless, direct evidence connecting AI-driven education to patient safety, clinical decision-making quality, or reduction in errors is still lacking. Most existing studies are descriptive, small in scale, and do not employ standardized evaluation frameworks.

The scarcity of rigorous longitudinal research underscores a significant gap in the literature. Future studies should incorporate follow-up periods of at least 12 months and apply validated performance and safety metrics to evaluate the durability of AI-enhanced learning outcomes. Building such evidence is crucial for determining whether AI-based educational interventions can not only improve immediate knowledge acquisition but also foster lasting clinical proficiency and enhance healthcare safety.

7.1. Limitations of This Review

Although this review aimed to provide a comprehensive synthesis of contemporary literature, several limitations should be acknowledged. The database search was restricted to English-language, peer-reviewed sources, which may have introduced language and publication bias. Relevant non-English or grey-literature studies might therefore be underrepresented. Owing to substantial heterogeneity in study design and outcome reporting, a formal quantitative synthesis was not feasible, although a PRISMA-style flow diagram was incorporated to improve transparency, a structured methodological quality appraisal (e.g., MMAT) could not be performed. As a result, findings may disproportionately reflect studies with positive results. Furthermore, most available investigations were conducted in single-institution contexts with short follow-up periods, which limits the generalisability of conclusions and may overstate the effectiveness of AI-enhanced educational interventions.

7.2. Research Agenda

To guide future investigations and support evidence-based advancement of AI in medical education, the following research priorities are proposed:

- Longitudinal evaluation of clinical competence: Determine whether improvements achieved through AI-supported learning persist over time and translate into measurable gains in clinical reasoning and patient outcomes.

- Validation of AI literacy curricula: Design and test structured curricula for students and faculty that standardize the teaching of algorithmic reasoning, ethical awareness, and data interpretation.

- Development of frameworks for AI competence assessment: Establish reliable metrics for evaluating diagnostic reasoning, decision-making, and responsible use of AI systems in educational settings.

- Faculty development and readiness studies: Identify effective models for training educators to integrate AI tools confidently while maintaining pedagogical rigour.

- Institutional and policy research: Explore governance structures, transparency standards, and ethical regulations for the responsible use of LLMs and data-driven educational platforms.

7.3. Practical Recommendations

The successful use of AI in medical education depends on thoughtful planning, clear policies, and long-term institutional commitment [5,59]. The points below outline practical steps that universities and teaching hospitals can take to make AI integration both effective and responsible:

- Integrate AI literacy across the curriculum. Include clear learning outcomes on topics such as algorithmic reasoning, data interpretation, and bias awareness at every stage of training.

- Create transparent institutional policies. Define how generative and analytical AI tools may be used in teaching, assessment, and research to maintain fairness and academic integrity.

- Invest in reliable digital infrastructure. Provide secure data storage, stable internet access, and interoperable platforms capable of supporting adaptive AI-based learning.

- Support faculty development. Offer ongoing workshops, mentoring, and ethics-focused seminars that help educators gain confidence in using AI tools and integrating them into teaching.

- Encourage interdisciplinary collaboration. Foster cooperation among clinicians, educators, computer scientists, and ethicists to design and evaluate AI-driven educational initiatives.

- Evaluate progress regularly. Monitor learning outcomes, data-security standards, and equity impacts to ensure that AI adoption continues to improve training quality and remains aligned with institutional goals.

8. Special Populations and Equity Considerations

The deployment of AI in medical education raises critical equity concerns across diverse learner groups. For students from underrepresented backgrounds, there is a delicate balance to maintain, while AI offers the potential for personalized learning and additional academic support. Improperly trained algorithms can further reinforce existing disparities [63]. The research conducted by Haider et al., [64] has shown that the use of AI can unintentionally contribute to widening racial disparities in healthcare, particularly affecting minority groups such as Black and Hispanic populations. The factors contributing to this issue include the use of biased datasets and flaws in algorithmic development (and additionally the inadequate use of such algorithms), as well as simply the influence of longstanding structural inequalities [65]. According to Celi et al., 2022 [63], U.S. and Chinese datasets and authors were disproportionately overrepresented in clinical AI; 40.8% of databases came from the US, followed by 13.8% from China, 24.0% of authors were Chinese and 18.4% constituted American authors. Additionally, almost all of the top 10 databases and author nationalities were from high-income countries. AI techniques were most commonly employed for image-rich specialties, and authors were predominantly male.

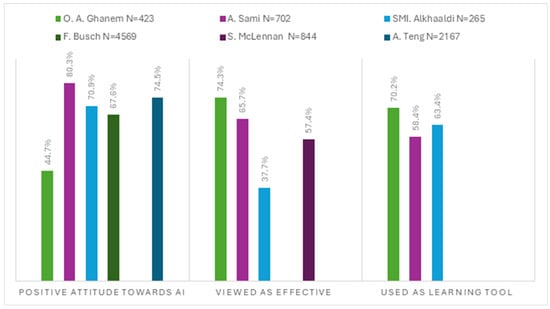

Figure 3 summarizes findings from six empirical studies assessing attitudes toward the integration of artificial intelligence in medical education. Across the included studies, students and residents expressed generally favorable views, particularly regarding AI’s perceived usefulness, educational value, and potential to improve learning. Despite differences in methodology and sample size, the collective evidence indicates broad support for incorporating AI-based tools into medical education (Sami et al. [65]; Ghanem et al. [66]; Teng et al. [67]; Busch et al. [68]; McLennan et al. [69]; Alkhaadli et al. [70]).

Figure 3.

Student and Resident perception of AI reported across six published studies. Sample size (N), Color coding: light green—Ghanem et al. [66]; violet—Sami et al. [65]; turquoise—Alkhaadli et al. [70]; dark green—Busch et al. [68]; dark violet—McLennan et al. [69]; dark blue—Teng et al. [67].

NLP tools, increasingly used to support comprehension and communication, may unintentionally disadvantage non-native English speakers. This is largely due to linguistic bias embedded in many LLMs, which often fail to adequately represent diverse accents, dialects, or sentence structures. Having a few thousand languages currently spoken worldwide, each one plays a crucial role in facilitating communication and preserving cultural identity within its community. English, unsurprisingly, dominates many NLP applications, largely due to its global reach and the concentration of researchers focused on it. The availability of resources for a given language is heavily influenced by both the number of its speakers and the extent of academic or technical attention it receives, resulting in notable disparities across the field of NLP [71]. The study by Liang et al. [72] uncovered a notable disparity in the performance of GPT detection tools, particularly in how they assess writing by non-native English users. A substantial portion of these texts were wrongly flagged as machine-generated, whereas native English samples were accurately classified in nearly all cases. The investigation showed that the detectors appear to favor more elaborate or stylistically rich language, often equating linguistic complexity with human authorship. When non-native texts were revised with more refined vocabulary, misclassification rates declined. Conversely, simplifying the language in native-written texts increased the likelihood of false AI identification. These patterns point to an inherent bias within detection systems that may unfairly impact individuals with limited proficiency in academic or literary English [71]. Such limitations of these models can result in miscommunication or misunderstanding, placing additional cognitive and emotional strain on learners whose first language is not English.

AI holds considerable promise for advancing medical education in rural areas by extending access to high-quality training. The use of tools such as virtual patient simulations, intelligent tutoring systems, and automated evaluation technologies can help deliver standardized instruction across geographically dispersed learning environments. Nonetheless, the effectiveness of these innovations is closely tied to the presence of stable internet connectivity and sufficient digital literacy, both of which remain inconsistent across rural regions to achieve meaningful impact, AI solutions must be adapted to rural settings and rigorously tested for equity and reliability. When applied thoughtfully, these technologies can help prepare a skilled and community-engaged rural medical workforce, while addressing long-standing disparities in healthcare access [73].

Another population that could benefit substantially from AI-enabled accessibility features are disabled students. Recent research by El Morr et al. [74] highlights the use of AI-powered tools such as voice assistants, natural language models, and real-time adaptation systems to support learners with diverse needs. For instance, AI has been employed to assist students with physical impairments through hands-free interfaces and to support visually impaired learners in mathematics through tailored language processing applications. For children with autism spectrum disorder, AI leverages technologies like adaptive learning and speech recognition to personalize instruction and track progress in real time [75]. These tools complement traditional assessments by capturing more nuanced learning patterns. These technologies not only promote greater autonomy and access but also create dynamic learning experiences that adjust to individual preferences and capabilities. However, in this case for the effective implementation of AI systems it is crucial to obtain feedback directly from the users, in order to maximize the relevance and usability [74]. Therefore, inclusive for a variety of disabilities, user-centered design practices, coupled with continuous validation and evaluation, are essential to realizing AI’s full potential in making education more accessible and equitable for students.

9. Training, Curriculum Integration, and Faculty Development

As previously stated, effective integration of AI within medical education hinges on faculty readiness. According to a study conducted by Naseer et al. [59] even though most of the respondents are keen on exploring more about the use of AI in teaching and learning, only 45.7% of faculty and 45.1% of students reported to be confident while using AI-based tools in their teaching and learning practices. Another recent study at a U.S. medical school revealed that both faculty and students largely rated themselves as novices or advanced beginners in AI proficiency. Usage of AI tools was infrequent in both groups, with 56% of faculty and 59% of students reporting only occasional use. Key barriers in the usage of AI included lack of knowledge as well as limited time to explore the tools, nonetheless both groups emphasized the need for training [76]. Therefore, to address this gap, structured professional development programs, including hands on workshops, peer led tutorials, and ethics-focused seminars are crucial in building educator competence and trust in leveraging AI in teaching [77] (see Table 4 for comparative data on student and faculty confidence, awareness, and AI usage trends).

Table 4.

Confidence, Awareness, and Use of AI Tools Among Students and Faculty.

Both learners and instructors face a steep learning curve with AI technologies. According to a study by Wood et al. [78] only 30% of students and 50% of faculty reported awareness of AI in medicine, and most had learned about it through media sources (72% of students and 59% of faculty). Despite differences in focus, with students being more interested in clinical uses and faculty in educational applications, both groups shared concerns about limited knowledge and time constraints. Preparation requires dedicated instructional time and scaffolded exposure, with introductory AI concepts introduced early and reinforced through practical use in clinical education.

Institutional readiness remains a critical prerequisite for effective AI deployment in medical education. Rural institutions often face unreliable internet infrastructure [58], whereas urban medical schools more commonly report inadequate digital systems, limited administrative engagement, and a lack of clear strategies for AI integration [79].

To support effective implementation, institutions must invest in secure cloud platforms, robust data management frameworks, and allocate sufficient time and personnel to collaboratively develop AI-informed teaching approaches.

Despite growing interest in AI in undergraduate medical education, there remains little consensus on appropriate content and instructional methods. Studies from 2017 to 2020 highlight recurring themes, yet reveal inconsistent teaching strategies, limited application of educational frameworks, and minimal evaluation of learning outcomes [80]. In the short term, AI integration should focus on developing digital literacy, critical thinking, and the ability to assess information reliability. Structured use of tools like ChatGPT can help students engage with emerging technologies while learning to distinguish credible sources from generic content. Long-term implementation requires a more comprehensive approach, embedding AI concepts throughout the curriculum, promoting interdisciplinary competencies, and ensuring institutional support for ethical and inclusive practices [81]. Incorporating AI within existing courses, such as clinical ethics, biostatistics, and case-based learning, offers a practical and efficient way to foster real world skills without overburdening the curriculum.

As previously demonstrated, AI holds substantial promise in medical education; however, the challenge of appropriate assessment of AI competence remains a critical concern. A study by Rezigalla et al., 2024 [82] evaluated the use of ChatPdf.com to generate MCQs for medical education. Experts rated most questions as good to excellent. Fifty percent of the items showed excellent discrimination between high and low performing students, while 30% were rated as good. Only one item performed poorly, and another showed no discrimination. Most distractors were effective (87%), with 60% of items rated excellent and 40% good based on distractor analysis. The findings confirm that AI-generated questions generally meet quality standards, yet the role of educators remains critical in reviewing these items to detect and correct any technical issues, ensuring their appropriateness and reliability for educational use. Another study, which compared AI and human generated MCQs, found that AI-created questions were easier but had similar discriminatory power. Although AI significantly reduced development time, experts noted more inaccuracies and a tendency to assess lower-order skills [83]. These results again highlight AI’s efficiency in test creation, but also the continued need for expert oversight to ensure quality. When used strategically and with sufficient faculty review, AI-generated items can support formative assessments and enhance modern curriculum design.

10. Current Frameworks

As artificial intelligence becomes increasingly relevant in healthcare, major accrediting organizations have begun to adapt their standards to reflect its growing importance in medical education. For instance, the Association of American Medical Colleges has introduced guiding principles that encourage equitable access, patient-centered applications, and the incorporation of AI-related competencies throughout all levels of training [84]. These measures aim to equip future healthcare professionals with the necessary skills to interact safely and ethically with AI technologies. In a similar effort, the General Medical Council has revised its graduate outcome expectations to emphasize digital fluency and data literacy as fundamental components of clinical preparedness [85]. By embedding these priorities into accreditation standards, institutions are encouraged to adopt a more structured and forward-looking approach to AI integration in both academic and clinical settings.

The use of AI systems in medical education often relies on large datasets generated through student engagement with digital platforms. Consequently, regulatory guidance is essential to govern the ethical use of this information. Policies must align with data protection standards such as HIPAA in the United States and the General Data Protection Regulation in Europe. We believe that student data used to train or improve AI tools should be anonymized, securely stored, and only accessible for educational enhancement with appropriate safeguards in place.

To support responsible AI use in medical training, institutions like the University of California, San Francisco have introduced clear guidelines. These frameworks allow students to use approved, HIPAA-compliant platforms, such as Versa Chat for educational and clinical activities, while restricting the use of commercial tools like ChatGPT when patient data is involved. Students are expected to critically evaluate AI-generated outputs and must not rely on these tools for graded assignments unless explicitly authorized. Any inappropriate use is treated as a breach of academic conduct, underscoring the importance of integrity, subject mastery, and adherence to professional standards [86]. In another university, students also must refrain from using AI tools to generate clinical documentation involving patient data unless the platform is HIPAA-compliant. Additionally, AI use in assignments must be transparently acknowledged and remain consistent with institutional honor codes [87]. These policies not only aim to protect academic standards but also to guide ethical student behavior in an evolving digital environment. Establishing clear boundaries for AI use ensures that learners engage with the technology responsibly and maintain ownership of their academic work.

11. Future Perspectives

Advanced LLMs, such as ChatGPT, are enabling the creation of autonomous virtual tutors capable of simulating realistic patient dialogues, generating customized case-based questions. These AI-driven teaching agents significantly expand opportunities for deliberate practice, allowing students to engage repetitively and independently while reducing demands on faculty time. Rather than solely delivering content, educators are now expected to guide students in navigating digital information ethically, critically, and responsibly as well as to ensure that empathy and academic integrity still remain central. LLMs have transformative potential for medical education, specifically including enhancing personalized learning [88].

Explainable AI (XAI) refers to AI systems designed to make their decision-making processes transparent and interpretable. In medical education, this interpretability fosters trust among students and educators, enabling them to critically assess AI-generated recommendations and ensure ethical, informed application in both clinical and academic contexts. XAI is especially vital in high-stakes domains like healthcare, where accountability and transparency are paramount. Among the most widely used XAI techniques are SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations), LIME (Local Interpretable Model-Agnostic Explanations), and DeepLIFT (Deep Learning Important FeaTures). SHAP applies principles from cooperative game theory to assign each feature a consistent contribution score, offering a global view of model predictions. LIME provides localized explanations by training an interpretable surrogate model, often linear, around individual predictions to approximate complex behaviors in an understandable format. DeepLIFT complements these approaches by comparing neuron activations to a reference input, helping reveal the internal workings of deep learning models. Together, these tools support transparency, mitigate bias, and facilitate compliance with ethical and regulatory standards in AI-assisted medical education [89].

Multimodal AI marks a significant advancement by integrating text, images, voice, and structured data into cohesive learning experiences. In medical education, this enables realistic simulations, such as combining a patient’s spoken symptoms, lab results, and imaging, for more immersive and clinically relevant training. These models, including GPT-4 and Med-PaLM 2, have shown improved diagnostic accuracy and decision-making support. While their applications in radiology and disease prediction offer substantial promise, they also raise ethical, legal, and environmental concerns, particularly regarding data privacy and carbon emissions. As such, thoughtful implementation is essential to balance innovation with responsibility [90].

Federated learning offers a privacy-preserving solution for developing AI systems across institutions by allowing models to be trained locally while sharing only model updates, not raw data. This decentralized approach maintains data confidentiality and enables collaboration without compromising sensitive student or patient information. Studies have shown that federated models can achieve better performance than locally trained ones, particularly when they incorporate a broader range of examples, including rare or underrepresented cases. While concerns about privacy remain, ongoing advancements in security protocols are reducing risks of data leakage. In both education and healthcare, this technique presents a promising strategy for building robust, generalizable AI tools while upholding ethical data standards [91].

Virtual patients provide a reliable and scalable way to help medical students build empathy, especially where traditional teaching methods fall short due to inconsistency, limited standardization, or high resource needs. These digital tools offer a safe, adaptable setting where students can repeatedly practice engaging with patient cases, refining essential communication skills such as active listening, emotional awareness, and compassion. They are particularly valuable when face-to-face training is limited, such as during public health crises. Beyond short-term solutions, virtual patients have long-term potential in medical education by encouraging empathetic behavior, reinforcing professionalism, and supporting better patient interactions, all of which can improve care quality and help prevent burnout in future clinicians [92].

12. Overview of Current Evidence

This review synthesizes findings from over 28 peer-reviewed sources, including systematic reviews, meta-analyses, randomized controlled trials, and pilot studies examining the role of AI in medical education (Kononowicz et al., 2019 [11]; Plackett et al., 2022 [13]; Çiçek et al., 2025 [18]). Across these studies, the evidence consistently suggests that AI-enhanced learning supports improvements in knowledge acquisition, diagnostic reasoning, and learner engagement.

However, the current evidence base remains limited in several ways. Much of the literature consists of single-institution studies, small sample exploratory surveys, and early-stage feasibility projects, with relatively few large, multi-center randomized trials or longitudinal evaluations (Rajpurkar et al., 2022 [2]). Considerable variability in study design, outcome metrics, and operational definitions of AI interventions further complicates cross-study comparison and reduces the generalizability of findings.

Collectively, these limitations highlight the need for coordinated multi-institutional research, standardized frameworks for evaluating AI-based educational tools, and extended follow-up periods to determine whether short-term learning gains translate into sustained clinical competence, improved decision-making, and ultimately, better patient outcomes.

To provide an overview of the current evidence base supporting these approaches, a summary of representative empirical studies including their populations, designs, AI modalities, and methodological quality is presented in Table 5.

Table 5.

Summary table of empirical studies.

13. Conclusions

AI is beginning to influence not just the tools used in medical training but the broader educational environment itself. As adaptive platforms, simulation technologies, and generative systems become more widespread, they invite a rethinking of how teaching and learning are organized. Educators increasingly serve as guides who help students interpret questions, and responsibly apply AI outputs, rather than simply transmitting information. In this sense, AI adoption represents a curricular and institutional shift, not merely the introduction of new software.

Most published work still focuses on immediate improvements following AI-enhanced instruction, offering little insight into whether these gains persist over time or translate into better decision making in clinical settings. There is still no robust evidence that AI-supported education improves patient level outcomes such as diagnostic accuracy, error reduction, or clinical safety. Research rarely examines the experiences of learners from different linguistic, cultural, or socioeconomic groups, leaving uncertainty about how bias, language barriers, or unequal access to technology may shape outcomes. The field therefore requires long-term, high-quality studies that include diverse participants and clinically meaningful measures.

To address the first guiding question, current evidence suggests that adaptive learning systems, virtual patients, generative tools, and emerging computer vision platforms can enhance knowledge acquisition, diagnostic reasoning, communication skills, and selected procedural competencies.

In relation to the second question, the review highlights substantial equity challenges: linguistic bias in language models, uneven digital infrastructure, and underrepresentation of minority groups can limit accessibility and produce disparate learning experiences for different student populations.

With regard to institutional and faculty readiness (the third question), existing studies show that while interest in AI is high, confidence, training, and technical capacity remain limited. Many educators report uncertainty about how to integrate AI into their teaching, and institutional strategies or governance structures often lag behind pedagogical needs.

Finally, answering the fourth question, responsible use of AI requires clear ethical principles, transparent governance, secure data management practices, and well-defined policies that outline acceptable and prohibited uses of AI in educational and clinical contexts. Without such safeguards, overreliance on automated systems may weaken essential clinical and communicative competencies.

For academic institutions, the task ahead involves integrating AI in a way that is methodical, equitable, and guided by ethical principles. Successful implementation depends on aligning curriculum goals, staff expertise, governance structures, and technical capacity. At the same time, institutions must ensure that AI enhances rather than replaces reflective and interpersonal aspects of clinical education.

When incorporated thoughtfully and governed responsibly, AI can enhance rather than diminish the human elements of medical training. Institutions that adopt a strategic, ethics-centered approach will be better positioned to prepare future clinicians for a healthcare environment in which human judgment and algorithmic tools increasingly intersect.

Author Contributions

Project leader, M.M.; Data acquisition, M.M., W.Z. and J.M.; writing—original draft preparation, M.M., W.Z., J.M. and A.N.; manuscript preparation, M.M., W.Z., J.M. and A.Ż.; visualization, A.Ż.; editing, A.Ż.; supervision, T.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available in PubMed at [https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov, https://www.scopus.com, https://www.webofscience.com], reference number [reference number-all included in study]. These data were derived from the following resources available in the public domain: PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science.

Acknowledgments

The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| ML | Machine learning |

| NLP | Natural Language Processing |

| LLM | Large Language models (LLM) |

| AR | Augmented reality |

| VR | Virtual reality |

| SP | Standardized patient |

References

- Schwalbe, N.; Wahl, B. Artificial intelligence and the future of global health. Lancet 2020, 395, 1579–1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajpurkar, P.; Chen, E.; Banerjee, O.; Topol, E.J. AI in health and medicine. Nat. Med. 2022, 28, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davenport, T.; Kalakota, R. The potential for artificial intelligence in healthcare. Future Healthc. J. 2019, 6, 94–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masters, K. Ethical use of artificial intelligence in health professions education: AMEE Guide No. 158. Med. Teach. 2023, 45, 574–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sriram, A.; Ramachandran, K.; Krishnamoorthy, S. Artificial intelligence in medical education: Transforming learning and practice. Cureus 2025, 17, e80852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatha, W.A. From scalpel to simulation: Reviewing the future of cadaveric dissection in the upcoming era of virtual and augmented reality and artificial intelligence. Cureus 2024, 16, e71578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holderried, F.; Stegemann-Philipps, C.; Herschbach, L.; Moldt, J.A.; Nevins, A.; Griewatz, J.; Holderried, M.; Herrmann-Werner, A.; Festl-Wietek, T.; Mahling, M. A generative pretrained transformer (GPT)-powered chatbot as a simulated patient to practice history taking: Prospective, mixed methods study. JMIR Med. Educ. 2024, 10, e53961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleinert, R.; Heiermann, N.; Plum, P.S.; Wahba, R.; Chang, D.H.; Maus, M.; Chon, S.-H.; Hoelscher, A.H.; Stippel, D.L. Web-based immersive virtual patient simulators: Positive effect on clinical reasoning in medical education. J. Med. Internet Res. 2015, 17, e263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kassutto, S.; Clancy, C.; Bennett, N.; Tsao, S. Virtual simulations to enhance medical student exposure to management of critically ill patients. ATS Sch. 2024, 5. Epub ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watari, T.; Tokuda, Y.; Owada, M.; Onigata, K. The utility of virtual patient simulations for clinical reasoning education. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kononowicz, A.; Woodham, L.; Edelbring, S.; Stathakarou, N.; Davies, D.; Saxena, N.; Car, L.T.; Carlstedt-Duke, J.; Car, J.; Zary, N. Virtual patient simulations in health professions education: Systematic review and meta-analysis by the Digital Health Education Collaboration. J. Med. Internet Res. 2019, 21, e14676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edelbring, S.; Dastmalchi, M.; Hult, H.; Lundberg, I.E.; Dahlgren, L.O. Experiencing virtual patients in clinical learning: A phenomenological study. Adv. Health Sci. Educ. Theory Pr. 2011, 16, 331–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plackett, R.; Kassianos, A.P.; Mylan, S.; Kambouri, M.; Raine, R.; Sheringham, J. The effectiveness of using virtual patient educational tools to improve medical students’ clinical reasoning skills: A systematic review. BMC Med. Educ. 2022, 22, 365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, E.; Hadadgar, A.; Masiello, I.; Zary, N. Augmented reality in healthcare education: An integrative review. PeerJ 2014, 2, e469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamphuis, C.; Barsom, E.; Schijven, M.; Christoph, N. Augmented reality in medical education? Perspect. Med. Educ. 2014, 3, 300–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bork, F.; Stratmann, L.; Enssle, S.; Eck, U.; Navab, N.; Waschke, J.; Kugelmann, D. The benefits of an augmented reality magic mirror system for integrated radiology teaching in gross anatomy. Anat. Sci. Educ. 2019, 12, 585–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, D.; Overgaard, J.; Pankratz, V.; Del Fiol, G.; Aakre, C. Virtual patients using large language models: Scalable, contextualized simulation of clinician-patient dialogue with feedback. J. Med. Internet Res. 2025, 27, e68486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Çiçek, F.E.; Ülker, M.; Özer, M.; Kıyak, Y.S. ChatGPT versus expert feedback on clinical reasoning questions and their effect on learning: A randomized controlled trial. Postgrad. Med. J. 2025, 101, 458–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiu, J.; Castro, B.; Ballard, I.; Nelson, K.; Zarutskie, P.; Olaiya, O.; Song, D.; Zhao, Y. Exploration of the role of ChatGPT in teaching communication skills for medical students: A pilot study. Med. Sci. Educ. 2025. Epub ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aster, A.; Ragaller, S.V.; Raupach, T.; Marx, A. ChatGPT as a virtual patient: Written empathic expressions during medical history taking. Med. Sci. Educ. 2025, 35, 1513–1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borg, A.; Georg, C.; Jobs, B.; Huss, V.; Waldenlind, K.; Ruiz, M.; Edelbring, S.; Skantze, G.; Parodis, I. Virtual patient simulations using social robotics combined with large language models for clinical reasoning training in medical education: Mixed methods study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2025, 27, e63312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarz, P.; Hellmers, S.; Spanknebel, S.; Hurlemann, R.; Hein, A. Humanoid patient robot for diagnostic training in medical and psychiatric education. Front. Robot. AI 2024, 11, 1424845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holderried, F.; Stegemann-Philipps, C.; Herrmann-Werner, A.; Festl-Wietek, T.; Holderried, M.; Eickhoff, C.; Mahling, M. A language model-powered simulated patient with automated feedback for history taking: Prospective study. JMIR Med. Educ. 2024, 10, e59213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vrdoljak, J.; Boban, Z.; Vilović, M.; Kumrić, M.; Božić, J. A review of large language models in medical education, clinical decision support, and healthcare administration. Healthcare 2025, 13, 603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dev, P.; Hoffer, E.P.; Barnett, G.O. Computers in medical education. In Biomedical Informatics; Shortliffe, E., Cimino, J.J., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2006; pp. 737–762. [Google Scholar]

- Jwayyed, S.; Stiffler, K.A.; Wilber, S.T.; Southern, A.; Weigand, J.; Bare, R.; Gerson, L.W. Technology-assisted education in graduate medical education: A review of the literature. Int. J. Emerg. Med. 2011, 4, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farooq, M.; Usmani, A. Artificial intelligence in medical education. J. Coll. Physicians Surg. Pak. 2025, 35, 503–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, D.A.; Hatala, R.; Brydges, R.; Zendejas, B.; Szostek, J.H.; Wang, A.T.; Erwin, P.J.; Hamstra, S.J. Technology-enhanced simulation for health professions education: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 2011, 306, 978–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tene, T.; Vique López, D.F.; Valverde Aguirre, P.E.; Orna Puente, L.M.; Vacacela Gomez, C. Virtual reality and augmented reality in medical education: An umbrella review. Front. Digit. Health 2024, 6, 1365345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moro, C.; Birt, J.; Stromberga, Z.; Phelps, C.; Clark, J.; Glasziou, P.; Scott, A.M. Virtual and augmented reality enhancements to medical and science student physiology and anatomy test performance: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Anat. Sci. Educ. 2021, 14, 368–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Robles, P.; Cortés-Pérez, I.; Nieto-Escámez, F.A.; García-López, H.; Obrero-Gaitán, E.; Osuna-Pérez, M.C. Immersive virtual reality and augmented reality in anatomy education: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Anat. Sci. Educ. 2024, 17, 514–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Shin, H.J.; Kwak, H.; Lee, H.J. Effects of immersive technology-based education for undergraduate nursing students: Systematic review and meta-analysis using the GRADE approach. J. Med. Internet Res. 2024, 26, e57566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arango-Ibanez, J.P.; Posso-Nuñez, J.A.; Díaz-Solórzano, J.P.; Cruz-Suárez, G. Evidence-based learning strategies in medicine using AI. JMIR Med. Educ. 2024, 10, e54507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolachalama, V.B.; Garg, P.S. Machine learning and medical education. NPJ Digit. Med. 2018, 1, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, T.; Gradus, J.L.; Rosellini, A.J. Supervised machine learning: A brief primer. Behav. Ther. 2020, 51, 675–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deo, R.C. Machine learning in medicine. Circulation 2015, 132, 1920–1930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Narayanan, S.; Ramakrishnan, R.; Durairaj, E.; Das, A. Artificial intelligence revolutionizing the field of medical education. Cureus 2023, 15, e49604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghorashi, N.; Ismail, A.; Ghosh, P.; Sidawy, A.; Javan, R. AI-powered chatbots in medical education: Potential applications and implications. Cureus 2023, 15, e43271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolfe, C.R.; Widmer, C.L.; Reyna, V.F.; Hu, X.; Cedillos, E.M.; Fisher, C.R.; Brust-Renck, P.G.; Williams, T.C.; Vannucchi, I.D.; Weil, A.M. The development and analysis of tutorial dialogues in AutoTutor Lite. Behav. Res. Methods 2013, 45, 623–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- As’ad, M. Intelligent tutoring systems, generative artificial intelligence (AI), and healthcare agents: A proof of concept and dual-layer approach. Cureus 2024, 16, e69710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ellaway, R.H. Virtual patients as activities: Exploring the research implications of an activity theoretical stance. Perspect. Med. Educ. 2014, 3, 266–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Danforth, D.; Procter, M.; Chen, R.; Johnson, M.; Heller, B. Development of virtual patient simulations for medical education. J. Virtual Worlds Res. 2009. Available online: https://jvwr-ojs-utexas.tdl.org/jvwr/article/view/707 (accessed on 25 September 2025). [CrossRef]

- Hui, Z.; Zewu, Z.; Jiao, H.; Yu, C. Application of ChatGPT-assisted problem-based learning teaching method in clinical medical education. BMC Med. Educ. 2025, 25, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiu, Y.; Liu, C. Capable exam-taker and question-generator: The dual role of generative AI in medical education assessment. Glob. Med. Educ. 2025. Epub ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlin GPoličar Špendl, M.; Curk, T.; Zupan, B. Automated assignment grading with large language models: Insights from a bioinformatics course. Bioinformatics 2025, 41 (Suppl. 1), i21–i29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Popov, V.; Mateju, N.; Jeske, C.; Lewis, K.O. Metaverse-based simulation: A scoping review of charting medical education over the last two decades in the lens of the ‘marvelous medical education machine’. Ann. Med. 2024, 56, 2424450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cangiarella, J.; Rosenfeld, M.; Poles, M.; Webster, T.; Schaye, V.; Ruggles, K.; Dinsell, V.; Triola, M.M.; Gillespie, C.; Grossman, R.I.; et al. Implementing an accelerated three-year MD curriculum at NYU Grossman School of Medicine. Med. Teach. 2024, 46, 1575–1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stamer, T.; Steinhäuser, J.; Flägel, K. Artificial intelligence supporting the training of communication skills in the education of health care professions: Scoping review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2023, 25, e43311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gligorea, I.; Cioca, M.; Oancea, R.; Gorski, A.-T.; Gorski, H.; Tudorache, P. Adaptive learning using artificial intelligence in e-learning: A literature review. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallée, A.; Blacher, J.; Cariou, A.; Sorbets, E. Blended learning compared to traditional learning in medical education: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e16504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Courteille, O.; Fahlstedt, M.; Ho, J.; Hedman, L.; Fors, U.; von Holst, H.; Felländer-Tsai, L.; Möller, H. Learning through a virtual patient vs. recorded lecture: A comparison of knowledge retention in a trauma case. Int. J. Med. Educ. 2018, 9, 86–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mujamammi, A.H.; Alqahtani, S.A.; Alqaidi, F.A.; Alharbi, B.A.; Alsubaie, K.M.; Alhaisoni, F.E.; Sabi, E.M. Evaluation of medical students’ satisfaction with using a simulation-based learning program as a method for clinical teaching. Cureus 2024, 16, e59364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Weng, Y.; Wang, B. CWT-ViT: A time–frequency representation and vision transformer-based framework for automated robotic surgical skill assessment. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 258, 125064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constable, M.D.; Zhang, F.X.; Conner, T.; Monk, D.; Rajsic, J.; Ford, C.; Park, L.J.; Platt, A.; Porteous, D.; Grierson, L.; et al. Advancing healthcare practice and education via data sharing: Demonstrating the utility of open data by training an artificial intelligence model to assess cardiopulmonary resuscitation skills. Adv. Health Sci. Educ. 2025, 30, 15–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zia, A.; Essa, I. Automated surgical skill assessment in RMIS training. Int. J. Comput. Assist. Radiol. Surg. 2018, 13, 731–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grantcharov, T.P.; Bardram, L.; Funch-Jensen, P.; Rosenberg, J. Assessment of technical surgical skills. Eur. J. Surg. 2002, 168, 139–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goh, P.S.; Sandars, J. A vision of the use of technology in medical education after the COVID-19 pandemic. MedEdPublish 2020, 9, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rincón, E.H.H.; Jimenez, D.; Aguilar, L.A.C.; Flórez, J.M.P.; Tapia, Á.E.R.; Peñuela, C.L.J. Mapping the use of artificial intelligence in medical education: A scoping review. BMC Med. Educ. 2025, 25, 526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naseer, M.A.; Saeed, S.; Afzal, A.; Ali, S.; Malik, M.G.R. Navigating the integration of artificial intelligence in the medical education curriculum: A mixed-methods study exploring the perspectives of medical students and faculty in Pakistan. BMC Med. Educ. 2025, 25, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, C.; Wibowo, S.; Li, L.D. The effects of over-reliance on AI dialogue systems on students’ cognitive abilities: A systematic review. Smart Learn. Environ. 2024, 11, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feigerlova, E.; Hani, H.; Hothersall-Davies, E. A systematic review of the impact of artificial intelligence on educational outcomes in health professions education. BMC Med. Educ. 2025, 25, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]