An Adaptative Wavelet Time–Frequency Transform with Mamba Network for OFDM Automatic Modulation Classification

Abstract

1. Introduction

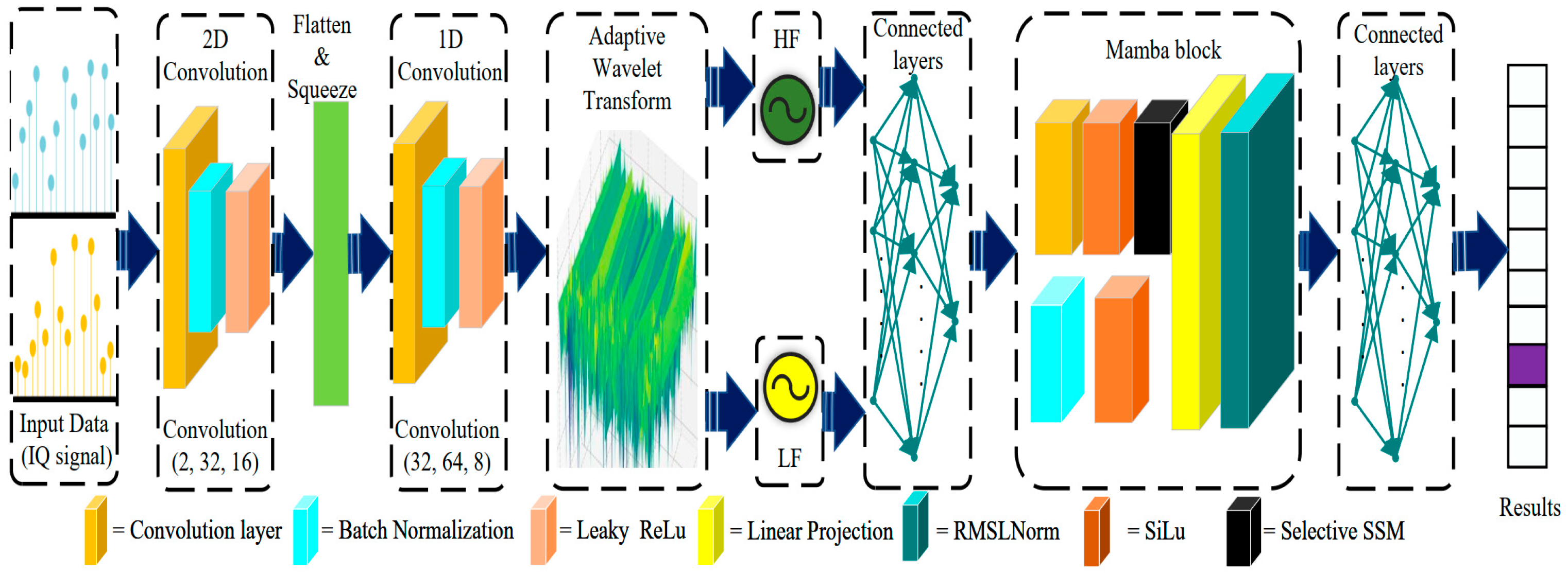

- This paper designs a network that combines traditional signal processing algorithms with deep learning networks to meet the requirements of future 5G and 6G for high-efficiency and low-latency scenarios in OFDM communication systems. To this end, adaptive wavelet transform is used for time–frequency domain feature extraction of signals, which is combined with an efficient Mamba network. Additionally, Gaussian white noise is utilized under low signal-to-noise ratios to improve performance with a smaller parameter scale.

- The algorithm proposed in this paper is based on adaptive wavelet transform and the Mamba network (AWMN). It extracts periodic frequency and time series features from the received OFDM IQ signals by means of adaptive wavelet transform and verifies them through the publicly available RML2016.10a and RML2016.10b datasets, proving that the overall model is more effective in AMC.

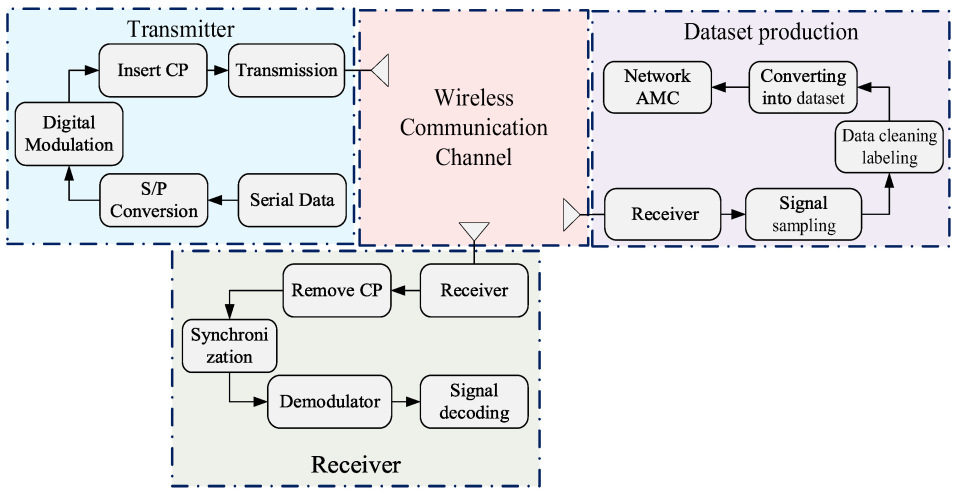

- This paper conducts real-time signal simulation experiments based on the NI LabVIEW 2020 and NI USRP 2944 software-defined radio simulation platforms, generating OFDM signals containing multiple digital modulation types. By using the KSW platform for channel simulation, we construct a real-time OFDM communication signal dataset with Doppler frequency shift and multipath effect.

2. System Models

2.1. Signal Model

2.2. Lifting Wavelet

3. Proposed Model

3.1. Adaptive Wavelet

3.2. Mamba Block

3.3. Loss Function

3.4. Adaptive Wavelet Mamba Network

4. Experiment Results and Discussion

4.1. Dataset and Experiment Settings

4.1.1. RML Dataset

4.1.2. EVAS Dataset Description

4.1.3. Training Configuration

4.2. Model Performance Ablation Comparison Analysis and Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Khoshafa, M.H.; Maraqa, O.; Moualeu, J.M. RIS-Assisted Physical Layer Security in Emerging RF and Optical Wireless Communications Systems: A Comprehensive Survey. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2025, 27, 2156–2203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doha, S.R.; Abdelhadi, A. Deep Learning in Wireless Communication Receivers: A Survey. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 113586–113605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhou, F.; Du, H.; Wu, Q.; Yuen, C. Revolution of Wireless Signal Recognition for 6G: Recent Advances, Challenges and Future Directions. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2025; Early Access. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satapathy, J.R.; Bodade, R.M.; Ayeelyan, J. CNN based Modulation classifier and Radio Fingerprinting for Electronic Warfare Systems. In Proceedings of the 2024 4th International Conference on Advance Computing and Innovative Technologies in Engineering (ICACITE), Greater Noida, India, 14–15 May 2024; pp. 1880–1885. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, A.; Quoitin, B.; Gros, A.; Moeyaert, V. A comprehensive survey on deep learning-based lora radio frequency fingerprinting identification. Sensors 2024, 24, 4411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chennagiri, R.; Sehgal, S.; Ravinder, Y. A Survey on Automatic Modulation Classification Techniques. In Proceedings of the 2024 Intelligent Systems and Machine Learning Conference (ISML), Hyderabad, India, 4–5 May 2024; pp. 94–100. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, J.L.; Su, W.; Zhou, M. Software-Defined Radio Equipped with Rapid Modulation Recognition. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2010, 59, 1659–1667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hameed, F.; Dobre, O.A.; Popescu, D.C. On the likelihood-based approach to modulation classification. IEEE Trans. Wirel. Commun. 2021, 116, 301–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kharbech, S.; Simon, E.P.; Belazi, A.; Xiang, W. Denoising Higher-Order Moments for Blind Digital Modulation Identification in Multiple-Antenna Systems. IEEE Wirel. Commun. Lett. 2020, 9, 765–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Chen, Y.; He, J.; Chang, S.; Feng, Z. Channel-Robust Automatic Modulation Classification Using Companding Spectral Quotient Cumulants. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2024, 73, 17749–17753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J. Automatic modulation classification using support vector machines and error correcting output codes. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE 2nd Information Technology, Networking, Electronic and Automation Control Conference (ITNEC), Chengdu, China, 15–17 December 2017; pp. 60–63. [Google Scholar]

- Luan, S.; Gao, Y.; Chen, W.; Yu, N.; Zhang, Z. Automatic Modulation Classification: Decision Tree Based on Error Entropy and Global-Local Feature-Coupling Network Under Mixed Noise and Fading Channels. IEEE Wirel. Commun. Lett. 2022, 11, 1703–1707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobre, O.A.; Abdi, A.; Bar-Ness, Y.; Su, W. Survey of automatic modulation classification techniques: Classical approaches and new trends. IET Commun. 2007, 1, 137–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Li, L.; Yang, S.; Li, S. Robust automated vhf modulation recognition based on deep convolutional neural networks. IEEE Wirel. Commun. Lett. 2018, 22, 946–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, S.; Jiang, H.; Wang, H.; Alwageed, H.; Zhou, Y.; Sebdani, M.M.; Yao, Y.-D. Modulation Classification Based on Signal Constellation Diagrams and Deep Learning. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2019, 30, 718–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huynh-The, T.; Hua, C.-H.; Pham, Q.-V.; Kim, D.-S. Mcnet: An efficient cnn architecture for robust automatic modulation classification. IEEE Commun. Lett. 2020, 24, 811–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, J.; Gan, F.; Cao, X.; Liu, W. Signal Modulation Classification Based on the Transformer Network. IEEE Trans. Cogn. Commun. Netw. 2022, 8, 1348–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, A.; Dao, T. Mamba: Linear-time sequence modeling with selective state spaces. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2312.00752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Cao, Y.; Li, G.; Li, X. MAMC—Optimal on Accuracy and Efficiency for Automatic Modulation Classification with Extended Signal Length. IEEE Commun. Lett. 2024, 28, 2864–2868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, L.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, J.; Yang, Z.; Xiao, X. Fast and Lightweight Automatic Modulation Recognition using Spiking Neural Network. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Symposium on Circuits and Systems (ISCAS), Singapore, 19–22 May 2024; pp. 718–727. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, J.; Luo, C.; Parr, G.; Luo, Y. A spatiotemporal multi-channel learning framework for automatic modulation recognition. IEEE Wirel. Commun. Lett. 2020, 9, 1629–1632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, W.; Cai, Z.; Wang, C. A Transformer and Convolution-Based Learning Framework for Automatic Modulation Classification. IEEE Commun. Lett. 2024, 28, 1392–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Zhou, N.; Wang, Z.; Liang, J.; Wang, Z. MSGNet: A Multi-Feature Lightweight Learning Network for Automatic Modulation Recognition. IEEE Commun. Lett. 2024, 28, 2553–2557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Yan, X.; Hao, X.; Yi, G.; Huang, D. Automatic Modulation Recognition of Radiation Source Signals Based on Data Rearrangement and the 2D FFT. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wang, T.; Feng, Z.; Yang, S. Toward the Automatic Modulation Classification with Adaptive Wavelet Network. IEEE Trans. Cogn. Commun. Netw. 2023, 9, 549–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huynh-The, T.; Nguyen, T.-V.; Pham, Q.-V.; da Costa, D.B.; Kwon, G.-H.; Kim, D.-S. Efficient Convolutional Networks for Robust Automatic Modulation Classification in OFDM-Based Wireless Systems. IEEE Syst. J. 2023, 17, 964–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Chaudhari, M.S.; Majhi, S. Automatic modulation classification for ofdm systems using bi-stream and attention-based cnnlstm model. IEEE Commun. Lett. 2024, 28, 552–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, G.; Jang, M.; Yoon, D. Automatic Modulation Classification for OFDM Signals Based on CNN with α-Softmax Loss Function. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 2024, 60, 7491–7497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daubechies, I.; Sweldens, W. Factoring wavelet transforms into lifting steps. In Wavelets in the Geosciences; Lecture Notes in Earth Sciences; Klees, R., Haagmans, R., Eds.; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2000; Volume 90, pp. 131–157. [Google Scholar]

- O’Shea, T.J.; Corgan, J.; Clancy, T.C. Convolutional Radio Modulation Recognition Networks. In Engineering Applications of Neural Networks (EANN 2016); Communications in Computer and Information Science; Jayne, C., Iliadis, L., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; Volume 629, pp. 213–226. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, C.; Tang, A.; Gao, F.; Liu, J.; Wang, X. Channel modeling framework for both communications and bistatic sensing under 3gpp standard. IEEE J. Sel. Areas Sens. 2024, 1, 166–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, A.; Lin, Y.; Hou, C.; Mao, S. Complex-valued networks for automatic modulation classification. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2020, 69, 10085–10089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| AWMN for OFDM Automatic Modulation Classification |

|---|

| Input: IQ signal sequence x (shape: [B, C, T]) Output: Modulation predictions logit (shape: [B, num_classes]) Initialize parameters: Adaptive Wavelet blocks, Mamba block, Conv layers, Linear layers Hyperparameters: num_wavelet_levels, num_classes, λd = 0.01, λa = 0.01 1. Adaptive Wavelet time-frequency feature extraction: a. Conv projection: x = Conv2d(x, kernel = (2,7), out_channels = 64) → [B, 64, T] b. Multi-level wavelet decomposition: for i in 0 to num_wavelet_levels-1: xeven = x[:, :, ::2], xodd = x[:, :, 1::2] H = xodd − P(xeven) L = xeven + U(H) Regularization regu_details = λd × mean (abs(H)) regu_approx = λa × dist (mean(L), mean(x), p = 2) regu_sum.append (regu_details + regu_approx) x = concatenate ([H, L], dim = 1) 2. Mamba long-term sequence modeling: a. Dynamic Δ prediction: Δ = Softplus(W_Δ · SiLU(Conv1d(x, kernel = 4))) b. Discrete SSM: A− = exp(Δ·A), B− = (exp(Δ·A)-I)/(Δ·A)·Δ·B c. Parallel scan: x = PScan(A−, B−·x) d. Output projection: x = C·x + D·x_input 3. Classification: x = AdaptiveAvgPool1d(x, 1) → flatten → Linear → Dropout → logit = Linear(x, num_classes) Return logit, regu_sum (for total loss: L_total = L_CE + sum(regu_sum)) |

| Type of Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| FFT Length | 256 |

| CP Length | 64 |

| Frame Length | 320 |

| Bit Block Size | 125 |

| 1st Message start | 53 |

| 2nd Message start | 129 |

| Sample per symbol | 16 |

| Sampling points | 1024 |

| Carrier frequency | 4G Hz |

| Doppler shift | 800 Hz |

| Modulation Type | BPSK, QPSK, 8PSK, 16PSK, 4PAM, 16QAM, 32QAM, 64QAM, 128QAM, 256QAM and 512QAM |

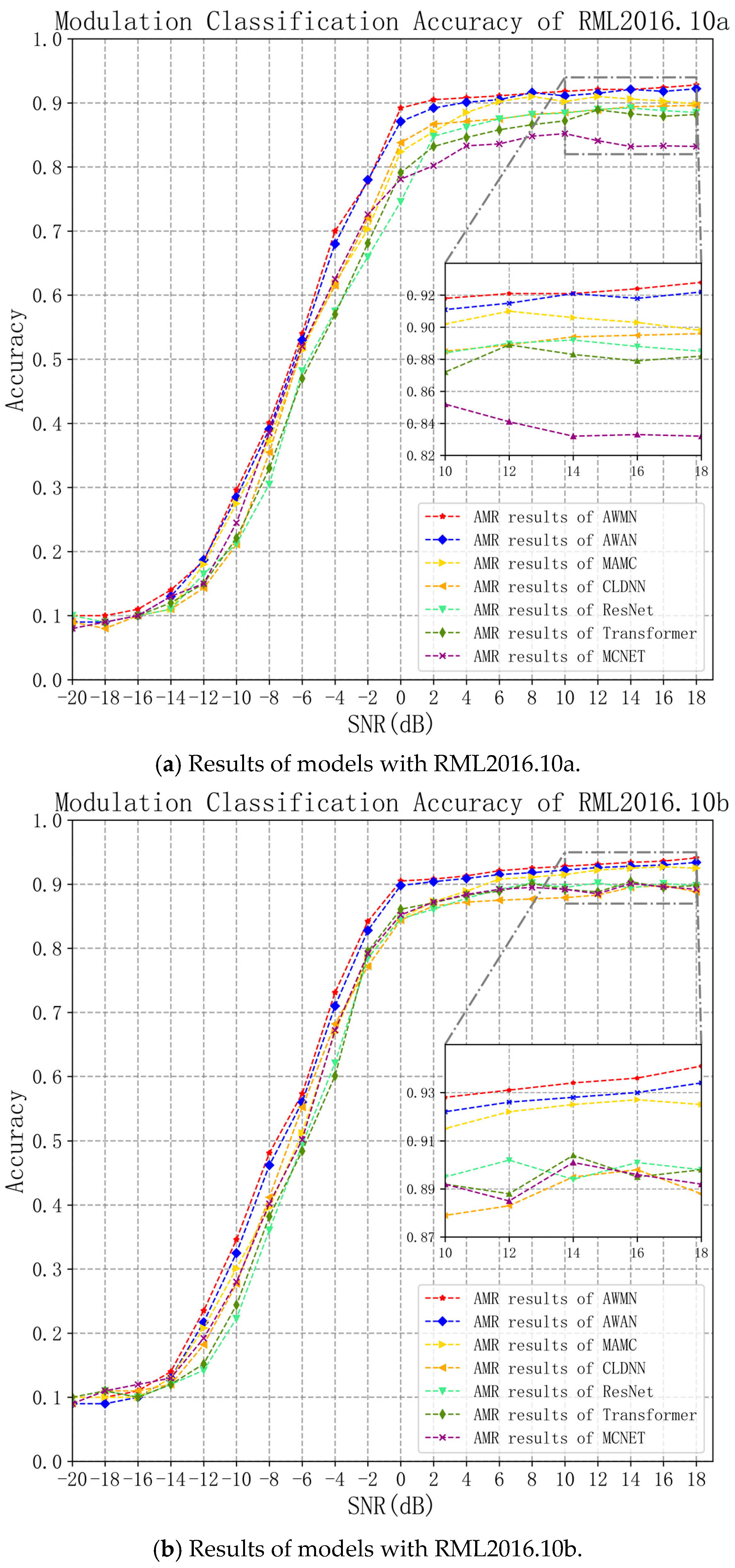

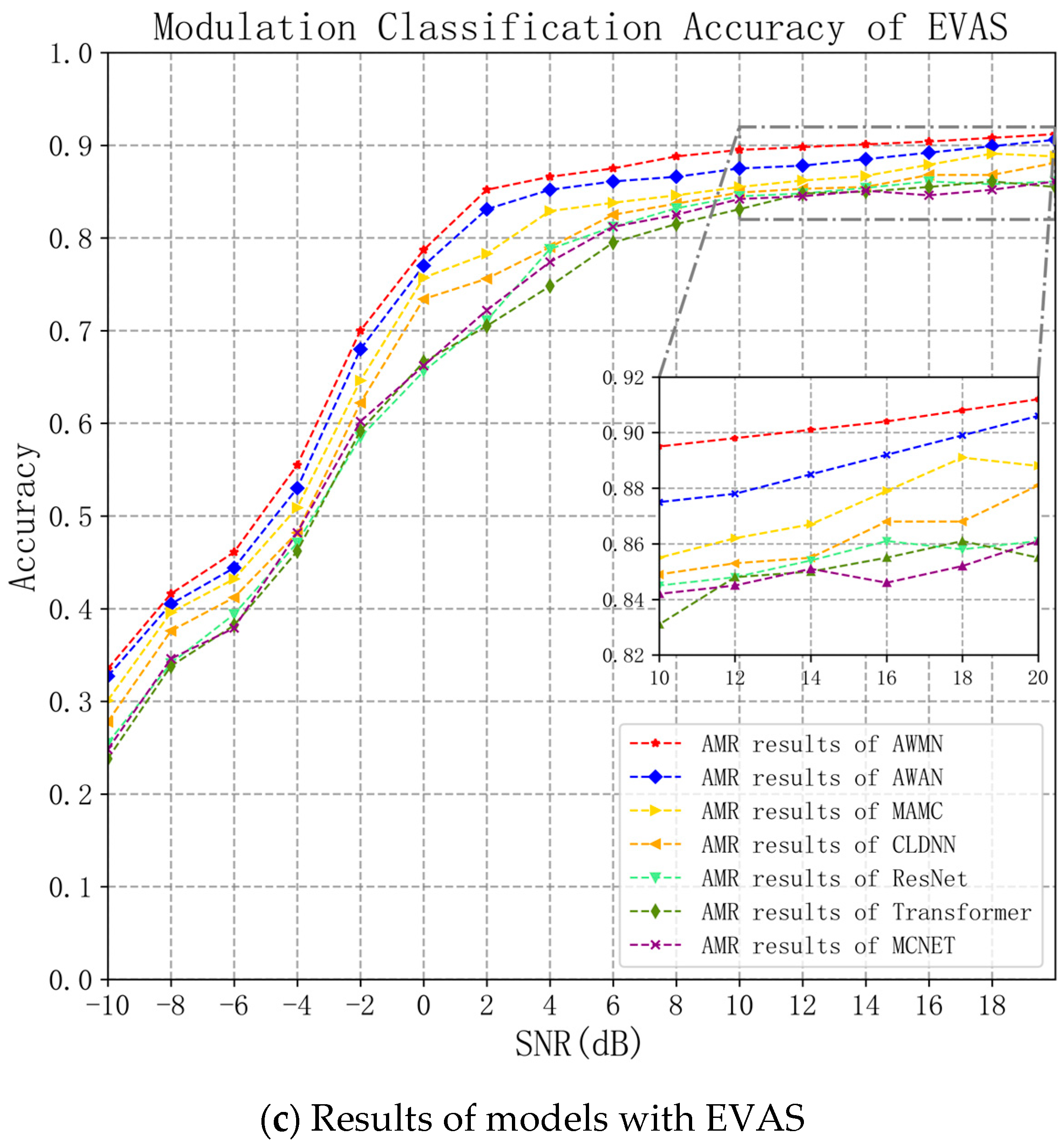

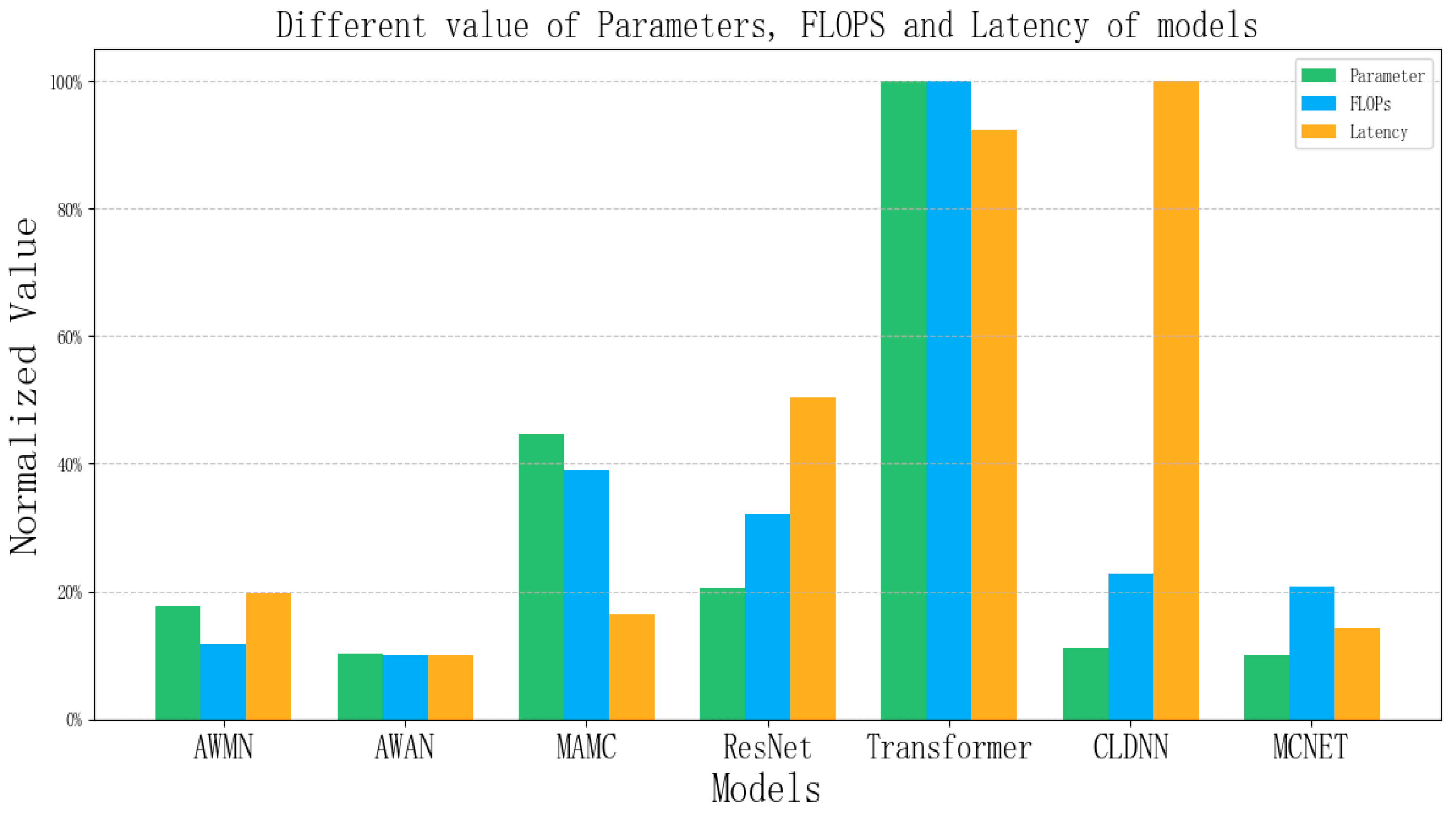

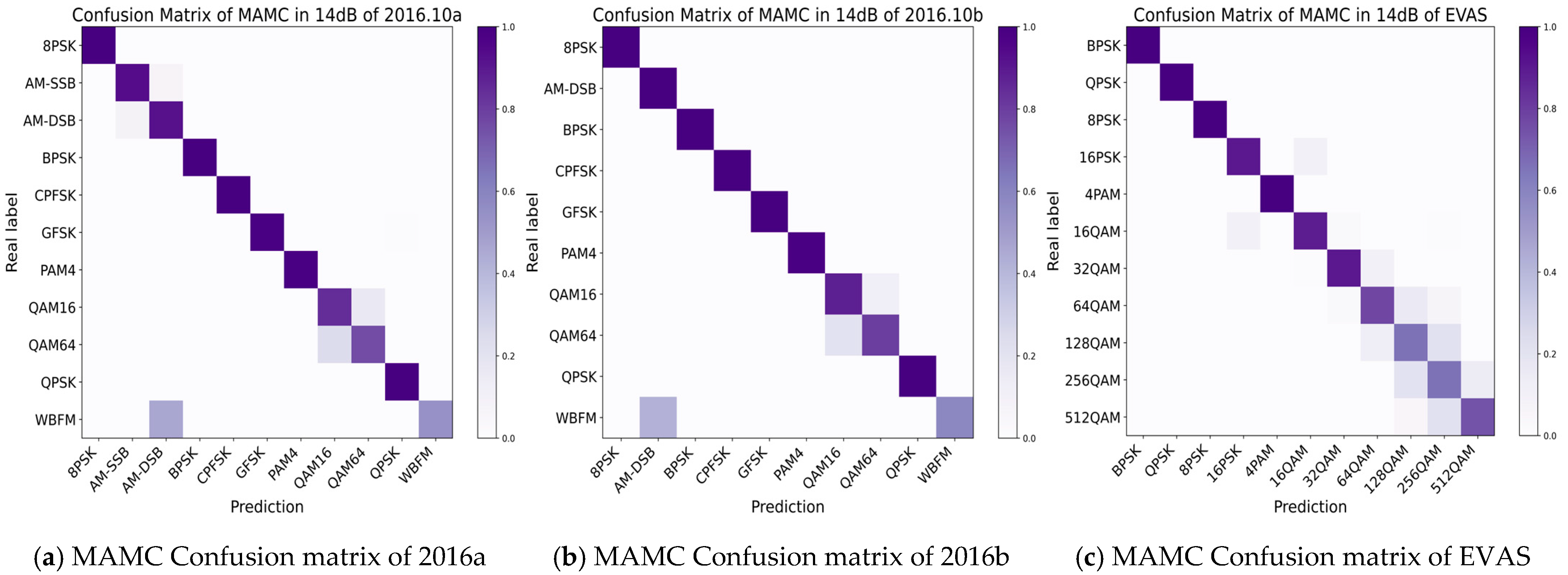

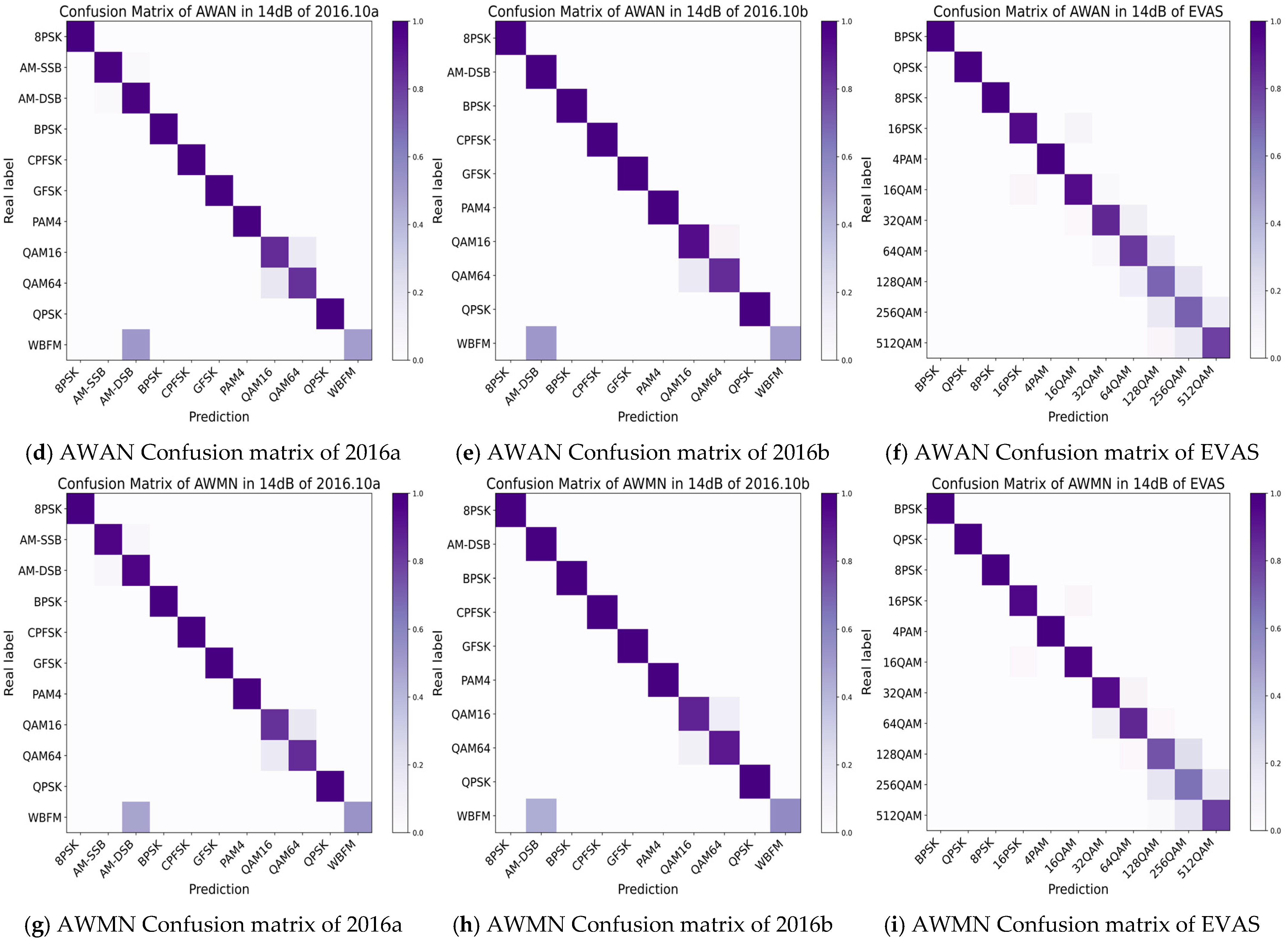

| Models | Maximum Accuracy (a) | Average Accuracy (a) | Maximum Accuracy (b) | Average Accuracy (b) | Average Accuracy (EVAS) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AWMN | 92.8% | 62.39% | 94.1% | 64.50% | 75.95% |

| AWAN | 92.2% | 61.66% | 93.4% | 63.48% | 74.38% |

| MAMC | 91.4% | 59.89% | 92.7% | 61.79% | 72.36% |

| ResNet | 89.2% | 57.11% | 90.8% | 59.52% | 68.57% |

| Transformer | 88.9% | 57.05% | 90.4% | 59.85% | 67.75% |

| CLDNN | 89.6% | 58.67% | 89.8% | 60.42% | 70.53% |

| MCNET | 87.1% | 56.70% | 90.1% | 60.75% | 68.43% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xing, H.; Tang, X.; Wang, L.; Zhang, B.; Li, Y. An Adaptative Wavelet Time–Frequency Transform with Mamba Network for OFDM Automatic Modulation Classification. AI 2025, 6, 323. https://doi.org/10.3390/ai6120323

Xing H, Tang X, Wang L, Zhang B, Li Y. An Adaptative Wavelet Time–Frequency Transform with Mamba Network for OFDM Automatic Modulation Classification. AI. 2025; 6(12):323. https://doi.org/10.3390/ai6120323

Chicago/Turabian StyleXing, Hongji, Xiaogang Tang, Lu Wang, Binquan Zhang, and Yuepeng Li. 2025. "An Adaptative Wavelet Time–Frequency Transform with Mamba Network for OFDM Automatic Modulation Classification" AI 6, no. 12: 323. https://doi.org/10.3390/ai6120323

APA StyleXing, H., Tang, X., Wang, L., Zhang, B., & Li, Y. (2025). An Adaptative Wavelet Time–Frequency Transform with Mamba Network for OFDM Automatic Modulation Classification. AI, 6(12), 323. https://doi.org/10.3390/ai6120323