Abstract

The prospect of repair, regeneration, and remineralisation of the tooth tissue is currently transitioning from the exploratory stages to successful clinical applications with materials such as dentine substitutes that offer bioactive stimulation. Glass-ionomer or polyalkenoate cements are widely used in oral healthcare, especially due to their ability to adhere to the tooth structure and fluoride-releasing capacity. Since glass-ionomer cements exhibit an inherent ability to adhere to tooth tissue, they have been the subject of modifications to enhance bioactivity, biomineralisation, and their physical properties. The scope of this review is to assess systematically the modifications of glass-ionomer cements towards bioactive stimulation such as remineralisation, integration with tissues, and enhancement of antibacterial properties.

1. Introduction

Glass-ionomer cement (GIC) is a long-established restorative dental material with several clinical applications that have remained relevant because of the chemical adhesive bond it forms at the tooth-restoration interface and its fluoride-releasing and recharging properties. It was invented by Wilson and Kent in 1969 and successfully introduced into clinical practice in 1972 [1,2,3,4,5]. Chemically activated GICs, commonly referred to as conventional GICs, typically consist of ion-leachable glasses based on calcium or strontium alumino-fluorosilicate and weak polymeric water-soluble acids of polyacrylic acid (PAA) homopolymer, or acrylic acid, maleic/itaconic acid copolymer [3]. They set by an acid-base reaction, and the setting reaction is initiated by mixing glass powder and polymeric acids. The acid attacks and degrades the glass, which leaches out ions, commonly Ca2+ and Al3+ ions, into the aqueous medium [1,3]. This results in a self-hardening process, an acid-base neutralisation reaction, which forms ionically cross-linked acidic polymer chains with the multivalent counterions (Ca2+ and Al3+) [3]. The self-hardening process typically occurs within 2–5 min after mixing the components of the cement mix. During the cement hardening, silica and phosphate ions are also released from the glass condensate to form an inorganic network within the matrix formed [3,6].

GICs at the initial setting stage are susceptible to water exchange across their outer surface either by absorption or via desiccation [1,7,8]. The drying out leads to a chalky appearance due to the formation of a network of micro-cracks on the cement surface [1,7], which compromise the aesthetic appearance. On the other hand, the water absorption of the early-set GIC leads to swelling, which may also cause the development of micro-cracks and a possible loss of network-forming ions [1]. To prevent these water movements, it is recommended that newly set GICs be protected with a layer of either petroleum jelly or varnish after their placement [1,7]. The coating of the GIC surface has been reported to improve flexural strength, which is beneficial in clinical applications [9]. Further reactions occur as the cement continues to mature, which include an increase in ionic cross-linking, a greater binding of water to co-ordination sites of the ions, and around neutralised polyanion molecules, which leads to an increase in the proportion of bound water within the cement and a change in the co-ordination number of aluminum, from 4- to 6-co-ordination state [1,10,11]. Other additional reactions that occur are the formation of silanol groups on the GIC surface, inorganic network formation from the ion-depleted glass, a reduction in the size of the pores trapped within the cement, and the development of ion exchange bonding to the tooth surface with time [1,10]. All these reactions during GIC maturation enhance both the mechanical and optical properties [1,10,11].

GICs are used clinically in restorative dentistry as long-term temporary restorations, definitive restorations for deciduous and permanent teeth, core build-ups, liners and bases, pulp capping agents, root surface and root end fillings, endodontic sealers, luting agents, fissure sealants, and adhesives in orthodontic brackets [12,13,14,15,16,17,18]. In addition, high-viscosity GIC (HVGIC) is the adhesive material of choice for the atraumatic restorative treatment (ART) technique [3,13,19]. The wide array of restorative and preventive applications of GICs in clinical practice is attributed to their biocompatibility, low pulp irritation, similar coefficient of thermal expansion as dentine, adhesion to tooth tissue (by micromechanical interlocking and, more importantly, chemical bonding), bioactivity, low microleakage at the interfaces, long-term fluoride release, and fluoride rechargeability following its depletion [3,8,12,20]. Despite these advantageous properties, GICs have some limitations, such as susceptibility to dehydration and inadequate mechanical properties, which limit their use as a dental restorative [3,8,20].

2. Search Methodology

An electronic search was conducted on the PubMed and Science Direct databases with different combinations of the following search terms: “glass-ionomer cement”, “addition”, “incorporation”, “improvement”, “enhancement”, “modification”, “adhesion”, “bioactivity”, “remineralisation”, “mechanical properties”, “antibiofilm activity”, and “antibacterial activity”. The search was restricted to articles written in English related to the modification of glass-ionomer cements. Only articles published in peer-reviewed journals were included. The search included literature reviews and in vitro and in vivo studies. Articles written in other languages without available abstracts and those related to other fields were excluded.

3. Adhesion

Glass-ionomer cements are water-based cements that facilitate their placement on intrinsically moist hard tissues in the oral environment. Thus, one of the clinical advantages is that elaborate isolation of the affected tooth tissue is not required, especially in the wet oral environment. The acid-base reaction that takes place between the water-soluble acidic polymeric phase and the basic glass causes the cement to form, and they bond particularly well with the mineral phase of the tooth, which has an abundance of calcium ions. There is evidence to support the formation of direct chemical bonds with the polymeric acid [1], which is mainly responsible for the effective adhesion of GICs to the tooth substrates.

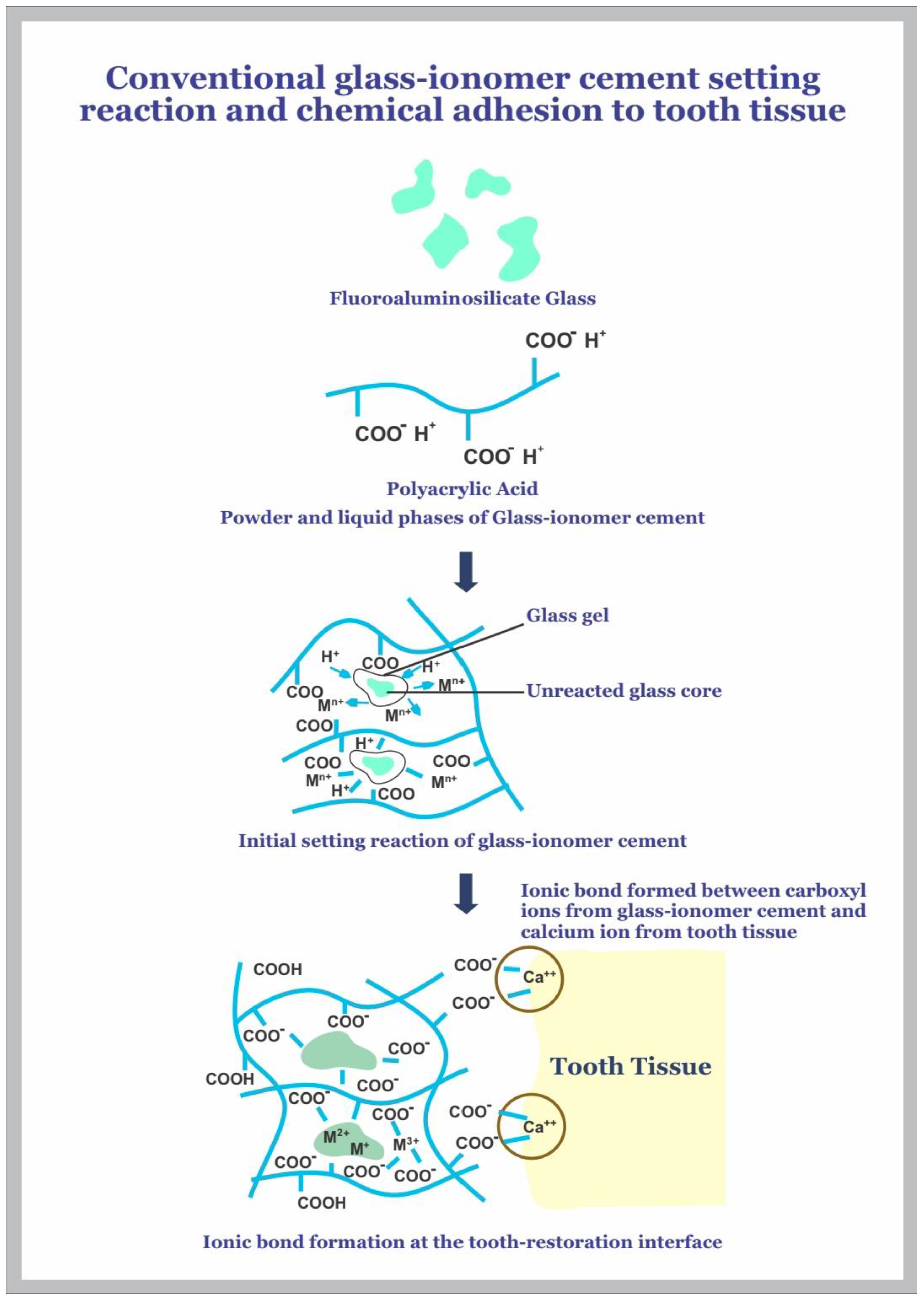

The chemical bond GIC forms with tooth tissue, as shown in Figure 1, reduces the incidence of adhesive failures, which in turn increases clinical survival when used in different clinical applications such as tooth repair, preventive, and adhesive measures [1,8].

Figure 1.

Chemical adhesion of glass-ionomer cement to tooth tissue.

The adhesion process begins with the wetting of the hydrophilic tooth surface following the placement of freshly mixed cement paste. The cement forms an intimate contact with the tooth, and this leads to adhesion through hydrogen bond formation between the free carboxyl groups of GIC and the bound water on the tooth surface [1,8]. These bonds are gradually replaced by true ionic bonds formed between calcium ions in the tooth and the anionic carboxylate functional groups of the polyacid molecules of the cement. This results in the slow formation of an interfacial zone of ion exchange, which leads to the formation of a strong adhesion of the cement with the tooth tissue, and the strength continues to increase over several days [1,8,10,18,21]. Adhesion of GIC to the tooth can be further improved by using conditioners, commonly 10–20% polyacrylic acid, on the tooth surface prior to the cement placement [1,8,22]. This surface treatment leads to self-etching that helps remove the smear layer, opening the dentinal tubules and partially demineralizing the tooth surface, which results in a thin hybrid layer between hydroxyapatite-coated collagen fibrils at the tooth and the cement surface [1,8]. This self-etching process increases the adhesion through micromechanical interlocking by the formation of short cement tags within the dentine surface, thereby increasing the surface area for retention [1,8].The increased clinical survival of GIC is attributed to the adhesion process as discussed, which contributes to its retention to the tooth and reduces the marginal leakage, which in turn lowers the incidence of secondary caries since micro-organisms are unable to enter the space under restorations [1,8,21].

4. Bioactivity

Bioactive materials are those that possess the ability to leach specific ions at the bonding interface, which usually results in a therapeutic effect and possible biomineralisation [8,23]. In relation to this, GICs are considered ‘bioactive’ or ‘smart’ materials because they release biologically active ions such as fluoride, calcium, strontium, sodium, phosphate, and silicate into the surrounding environment at therapeutic levels under acidic conditions that result in adhesive bonding [8,23]. Although fluoride ions do not participate in cement formation or adhesion, their release is generally considered to have clinical benefits, even though the reports supporting this are not fully convincing and are debatable [8]. Fluoride ions are reported to inhibit the formation of secondary caries, encourage the remineralisation process via the formation of fluorapatites, which resist demineralisation due to their low solubility, disrupt ionic bonding to the tooth surface during pellicle and plaque formation, reduce the acidogenicity of bacteria, and slow down bacterial metabolic activities [24,25,26,27,28,29]. However, other studies suggest that the antibacterial activity of GICs is most likely due to the low pH of the GIC setting reaction and that the fluoride ions have minimal antibacterial effects [30]. This is plausible since the effect may be mainly due to the reduction in acidogenicity of the bacteria and disruption of plaque and pellicle formation. Since fluoride ions are not a part of the setting reaction but essentially remain present in the cement matrix, it is possible to recharge them, enabling both release and recharge at high concentrations of fluoride. In the long term, the fluoride re-released after recharging may be much more important than the initial ‘burst’, which is short-lasting [31]. In addition to the leaching of fluoride, other caries inhibitory species such as strontium, zinc, calcium, and aluminum have been suggested to play a role in the antibacterial activity of GICs [24,25,32]. Calcium and phosphate are the main component ions of hydroxyapatite (HA), and they encourage tooth remineralisation when present in a mildly acidic medium [8]. GICs also take up calcium and phosphate ions present in saliva, and this leads to a harder surface [8,33]. Silicate can be incorporated into the hydroxyapatite of the tooth without having a negative impact on the crystal geometry, although it remains unclear whether this occurs under clinical conditions [8,34]. In essence, the ability of GICs to exchange ions with their surroundings leads to the formation of an ion-rich layer over time that is resistant to acid attack. This in turn results in a low incidence of secondary caries at the tooth-restoration interface when GIC is used as a restorative material [8].

The focus of recent glass-ionomer research has been on bioactivation, with the aim of improving the mechanical properties [35,36,37,38]. The term ‘bioactivity’ has several meanings depending on context, but recent research has referenced the following definitions when investigating the bioactivity of GICs: Firstly, bioactivity can be defined, based on adhesion, as the ability of a material to be biologically active and form a bond with living tissue without the formation of a fibrous layer in vivo [35,39]. With reference to this definition, GIC is regarded as bioactive since its polyalkenoic acid component forms a chemical bond with the apatite component of enamel, dentine, and bone [35].

On the other hand, GIC is not yet typically regarded as bioactive based on other definitions focused on the biomineralisation induction capacity of materials. Such definitions describe a material as bioactive when it can form a layer of material, such as apatite, that is inherent to and integrates with the body [23,35,40,41]. In this context, materials are commonly referred to as bioactive if they can interact with living tissues and prompt a cellular response to stimulate HA formation [42]. A material’s bioactivity is therefore commonly defined as the ability of a material to induce apatite formation on its surface in vitro after immersion in a simulated body fluid (SBF) solution [23,39,43,44] and in vivo likewise [23,39,44]. Therefore, the bioactivity of dental materials commonly relates to their potential to induce specific and intentionally desired mineral attachment to the dentine substrate at the material-tooth tissue interface. It is important that these bioactive materials convert to HA in a controlled manner and time [39]. The bioactivity of glass-ionomers, as conducted in several in vitro studies, is predicated on its HA formation ability on the material surface upon immersion in a physiological fluid, commonly SBF [35,36,42,45,46,47]. This method has the drawback of reporting false positive and false negative results; therefore, it is recommended that, in addition to in vitro cell tests, in vivo studies be performed to validate the bioactivity results that are obtained when tested in simulated body fluid (SBF) [35,48].

Several factors, such as the concentration of calcium and phosphate ions, pH, the presence or addition of bioactive particles, and the GIC composition (the ions present in the glass phase, PAA, monomers, primers, and the size and volume of particles) have been suggested to account for HA nucleation and growth [46,49,50]. It has been reported that PAA inhibits HA formation because of the intermediate compound formed by the reaction of anions from the PAA with calcium cations, and this compound delays the interaction of the calcium and phosphate ions to form HA precursors [43,46,51,52]. However, it has also been reported that this intermediate compound serves either as nucleators or inhibitors of HA to regulate the deposition of minerals [46,53].

Incorporation of bioactive particles into GIC has been of concern due to reports on the detrimental effects it has on the mechanical properties despite its promotion of bioactivity [54,55]. However, more recent literature suggests that attempts to promote bioactivity while optimising or even enhancing the mechanical properties are viable [35,36,46,56]. The promotion of remineralisation potential of GICs would broaden its clinical applications, particularly when used in long-term ART restorations, since apatite integration within the tooth structures would lead to proliferation of dental cells and further enhance adhesion, which in turn would improve the physical properties and retention within demineralised dentine tissue [35].

5. Remineralisation Properties of GIC

Calcium and phosphate ions play an important role in the balance of the HA mineral phase of dental hard tissues, and under mildly acidic conditions, they can promote tooth remineralisation [8]. Due to the ability of GIC to exchange ions with the surroundings, which is also applicable to tooth tissue, an ion-rich layer is formed over time at the GIC-tooth interface, which is resistant to acid attack, therefore reducing the incidence of secondary caries [8].

The mineralisation potential of GIC is a desirable property, which has prompted researchers to explore different ways to enhance the bioactivity of GIC by exploring the chemistry and developing new routes to glass synthesis and, more commonly, modification of the GIC-matrix by incorporating bioactive glasses (BAG), hydroxyapatite (HA), beta-tricalcium phosphate (β-TCP), casein phosphopeptide–amorphous calcium phosphate, and other bioactive materials into the glass-ionomer powder and/or the liquid phases [5,12,14,15,35,36,45,46,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68].

Since its introduction in 1969 by Larry Hench [69], BAG has widely been used in dental materials such as gutta percha, dental adhesives, GIC and composite resins, pulp protective dressings, endodontic sealants, and orthodontic cements [46]. The combination of BAG and GIC has benefits, with a significant increase in remineralisation capacity; however, the effect of BAG on the mechanical properties and setting kinetics of GIC are often contradictory [34,35,45,49,52,53,59,60,61,62,63,64,70,71,72,73,74]. This is in agreement with other studies reporting that higher amounts of BAG additives in GIC cements compromise the mechanical properties, which are attributed to the partial replacement of the fluoro-alumino silicate glass powder phase. This results in a decrease in the amount of Al3+ in the glass, resulting from its replacement of Na+ in BAG, and a reduction in the bond strength between PAA and the ions released [3,35,54]. The addition of Al3+ to the BAG composition has been reported to be beneficial in improving the strength of BAG-GIC composites, but this decreases bioactivity [3,35,54]. The inclusion of nano-sized particles of BAG into glass-ionomers is also believed to at least reduce the likelihood of the extent of compromise in mechanical properties. The BAG nanoparticles may occupy the voids between the larger glass-ionomer particles and act as additional PAA bonding sites, thereby improving the mechanical properties [61]. The reactivity of the BAG nanoparticles with the GI matrix is higher, and the pH rapidly increases, which could further develop the silica gel and apatite layer formed [35,75]. The incorporation of BAG nanoparticles into GICs can enhance their odontogenic and osteogenic properties for clinical applications such as root surface fillings and bone regeneration [61].

β-TCP contains a significant amount of calcium and phosphate, which can promote remineralisation of enamel when incorporated into the glass phase of GIC [76]. A recent report has shown that the addition of fortilin (which is also referred to as ‘translationally controlled tumour protein’) to β-TCP as a GIC additive further promotes odontogenic differentiation and mineral deposition in human dental pulp stem cells (hDPSCs) [68]. HA nanoparticles are widely used in dentistry because they are biocompatible bio-ceramics that promote enamel remineralisation and have superior osseointegration properties [77,78]. Numerous studies have revealed that the incorporation of hydroxyapatite nanoparticles into GIC can significantly improve the interfacial bond strength, improve marginal adaptation to tooth tissue, enhance the mechanical properties, reduce cytotoxicity, and leave the sustained release of fluoride unaffected [77,79,80,81]. Forsterite (Mg2SiO4) has been reported to be more effective as nanoparticles in promoting bioactivity and enhancing the mechanical properties of GIC. This is attributed to the higher surface energy and increased reactivity [63,66]. Wollastonite (also known as calcium silicate) is another material known to promote bioactivity. It is available in nature or can be synthesised from mine-silica and limestone. Its inclusion into the powder phase of GIC reinforces the mechanical properties, reduces cracks, and decreases shrinkage, due to its acicular nature [3,82]. Wollastonite has been reported to promote the formation of an apatite layer on the surface of powder in simulated body fluid [83]. Published data related to the combination of wollastonite with GICs are limited, but it has been reported that the incorporation of wollastonite into GIC promotes the bioactivity without compromising compressive strength [56]. Casein phosphopeptide-amorphous calcium phosphate (CPP-ACP) nanocomplexes have been shown to prevent enamel demineralisation and promote the remineralisation of carious enamel [66,84]. The incorporation of CPP-ACP into the glass phase has been found to enhance the anticariogenic properties of GIC. This is because of the localisation of casein phosphopeptide to amorphous calcium phosphate at the tooth surface, which results in a prolonged state of supersaturation of the tooth mineral [38,84]. CPP-ACP as GIC additives has shown to increase the release of calcium, phosphate, and fluoride ions from the cement, and this leads to increased protection of the adjacent dentine from acid demineralisation [85]. In addition, CPP-ACP interacts with fluoride ions released from GIC to form a stabilised amorphous calcium fluoride phosphate complex, and this further augments its anticariogenic potential [38,84,85]. The various strategies that have been used so far in promoting the remineralisation of GICs are summarised in Table 1 [5,15,16,35,36,37,38,55,56,57,58,59,62,63,64,65,68,76,86].

Table 1.

Modification of GIC using various additives for the promotion of bioactivity [5,15,16,35,36,37,38,55,56,57,58,59,62,63,64,65,68,76,86].

6. Antibacterial Properties

With an increasing clinical demand for tooth-coloured materials with superior mechanical properties, wear resistance, remineralisation, and antibacterial effects, improvements to these properties in GIC have gained the interest of researchers. The low pH during the initial setting of GIC, the fluoride-releasing properties of GIC, as well as its ability to leach other therapeutic ions such as strontium and zinc, have all been suggested to play a role in the antibacterial property of GIC; however, these effects are minimal [2,24,25,32,87,88].

The slight antimicrobial properties displayed by unmodified GIC are attributed to the fluoride ions that are released, which have therapeutic benefits against bacteria remnants at the restoration-dentine interface following excavation of infected dentine [89]. The fluoride release has been shown to encourage the remineralisation process in addition to the formation of low-soluble fluorapatite (FAp), which is more resistant to demineralisation [2,24,25,26,27,28,29,90]. FAp formation disrupts ionic bonding to the tooth surface during pellicle and plaque formation, reduces the bacteria’s acidogenicity, and slows down bacterial metabolic activities [2,24,25,26,27,28,29,90]. However, it has been reported that fluoride release most likely has minimal antibacterial effects and that this antibacterial property ceases after the GIC hardens since it is attributed to the low pH of the GIC setting reaction [30,87,88,91].

In addition to its mechanical, remineralising, and adhesive properties, improvements in GIC’s antibacterial properties would be highly beneficial in treating residual cariogenic bacteria and preventing the recurrence of caries. This ultimately is expected to increase the clinical survival rates when used as restorative dental material and improve its efficacy as a lining material by serving as an antibacterial seal under restorations and as a fissure sealant over the occlusal surfaces of teeth highly susceptible to caries [92,93]. Enhancing antibacterial activity would be particularly useful in ART, which involves the removal of carious lesions and placement of HVGIC with the use of manual instruments only. ART is usually performed in constrained environments where functional dental equipment is lacking or in cases of uncooperative patients, such as special needs patients, where it is difficult to manage the patient and when it is unlikely to completely remove infected caries [92,93,94].

The limited antibacterial activity of GICs has led to studies to augment this property by the addition of a range of antimicrobial agents to the powder or liquid phase of GIC that can interfere with metabolic activity and inhibit biofilm formation and the adherence of cariogenic bacteria [3,12,87,89,95,96]. Enhancement of the antibacterial activity of GIC is largely dependent on the concentration and type of antimicrobial agent used as an additive and its release rate from the cement surface layer [3,12,87]. However, it is of utmost importance that if the inclusion of these antimicrobial additives into glass-ionomer fillers or liquids does not improve the physical properties, fluoride release, and adhesive properties of the cement, it should at least not compromise these properties for it to remain clinically relevant [3,12,87]. So far, the incorporation of these antibacterial modifiers into conventional GICs has led to promising results, with the potential for these modified GICs to be more clinically beneficial [3,12,87,89,95,96,97].

Some of the additives that have been explored are natural products such as graphene, chitosan, propolis, turmeric, and epigallocatechin-3-gallate; antibiotics such as metronidazole, ciprofloxacin, and minocycline; antiseptics such as chlorhexidine (CHX) [CHX diacetate and CHX digluconate], triclosan, quaternary ammonium salts such as cetrimide, benzalkonium chloride, and cetyl pyridinium chloride; and metallic dopants such as silver, zinc, magnesium, and titanium [3,12,87,89,95,96,97].

Chlorhexidine (CHX) has a wide spectrum of activity against Gram-positive bacteria, especially mutans streptococci, Gram-negative, aerobic and facultative anaerobic bacteria, and fungi. Whilst some studies have reported that the incorporation of CHX salts into GIC increases their antimicrobial activity without compromising their physical properties, other studies have reported that CHX additives negatively impart mechanical properties, fluoride release, and biocompatibility at high doses. Following extensive research, it has been suggested that an addition of not more than 1% of CHX into GIC provides optimal antibacterial activity without compromising the physical properties [92,98,99,100,101]. A higher concentration of CHX is not contributory to the formation of the glass-ionomer network and would weaken the scaffold, thereby affecting the physical properties of GICs [3,102]. CHX has also been reported to have long-term antibacterial properties because of its substantivity effect by binding to hydroxyapatite. This leads to a gradual release of CHX over an extended period [98,103,104]. The addition of quaternary ammonium salts as well as antibiotics have also been reported to be dose-dependent in order to be effective without compromising physical properties [30,94,103,105,106,107,108,109]. Polyhexamethylene biguanide (PHMB) is another broad-spectrum bactericidal agent that has recently been explored as a glass-ionomer additive. It has been widely used in trauma treatment, ophthalmic disinfection, and many other biomedical fields. PHMB eliminates bacteria by binding protonated groups to the anionic membrane of bacteria, which results in a leak in the cytoplasm. Unlike chlorhexidine and quaternary ammonium compounds, PHMB not only has superior antibacterial activity but has also been reported to be biocompatible at high concentrations [77,110].

Chitosan is a natural biopolymer that is relevant in the dental (or biomedical) field due to its biocompatibility, natural adhesive properties, and antibacterial properties [36,64]. It acts as a physical or chemical binder between the glass filler and matrix in GIC, thereby improving the mechanical properties [36]. Epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG) is another antibacterial agent that is worth exploring as an additive. It is a major polyphenol present in green tea, and it has been reported to be effective against both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria [3,111]. It destroys the cellular structures, inhibits cellular enzymes, and causes intracellular oxidative stress in the bacteria [112,113]. A study has shown that the inclusion of EGCG into GICs at low concentration improved the antibacterial activity and some mechanical properties of GICs [114]. The strength enhancement is attributed to an increase in crosslinking and a high degree of poly-salt bridging [3,115,116]. Another natural product that can serve as an antibacterial additive is propolis. It is a natural resin sourced from honeybees. Ethanolic extracts of propolis (EEP) are the most used form for antibacterial activity [117]. The mechanism of its antibacterial property is associated with its activity against cariogenic bacteria and inhibition of glucosyltransferase activity [118]. Despite its well-known antimicrobial activity against oral microorganisms, only a few studies have investigated the effect on the physical properties of GIC when EEP is used as an additive [119,120]. The paucity of data investigating the effect of EGCG and EEP on GIC properties shows that more in vitro studies still need to be carried out before it can be used for clinical applications.

Ionic dopants such as magnesium, zinc, silver, copper, and titanium are of interest for use in biomaterials due to their antimicrobial properties against bacteria, spores, and viruses [121,122]. Most nano-metallic dopants such as these have been reported to be cytotoxic as the concentration increases. Despite the mechanical reinforcement observed when nano-metallic dopants such as zinc, silver, copper, and titanium oxides are incorporated into GIC, there have been reports of cytotoxicity, discolouration, poor marginal adaptation, and decreased interfacial bonding following an increase in concentration [2,67,77,123,124,125,126,127,128]. On the other hand, magnesium nanoparticles have been reported to be biocompatible and thermally stable; however, they compromise the physical properties of GIC when added in high concentrations [96,129,130]. Little research has been performed on investigating the effects of fluorinated graphene (FG) (a derivative of graphene). FG can serve as an antibacterial material since graphene has been reported to be effective against bacteria [2]. FG has been reported to be a biocompatible material because it enhances the proliferation and polarisation of mesenchymal stem cells and the neuro-induction of stem cells [2,131,132]. The inclusion of FG in GIC has been reported to be highly beneficial for the property enhancement of GIC. Studies have shown that it significantly improves the mechanical and antibacterial properties of GIC without interfering with fluoride release [2,133]. A summary of attempts made by various researchers to improve the antibacterial activity alongside other properties is shown in Table 2 below [2,4,30,77,87,91,92,93,94,96,97,98,99,101,103,105,106,107,108,109,114,119,120,123,127,129,133,134,135,136,137,138,139,140,141,142,143,144,145,146].

Table 2.

Modification of GIC using various additives for enhancing antibacterial activity [2,4,30,77,87,91,92,93,94,96,97,98,99,101,103,105,106,107,108,109,114,119,120,123,127,129,133,134,135,136,137,138,139,140,141,142,143,144,145,146].

Even though GIC modification using these various additives has shown promising findings, more studies are required to elucidate the effect of these additives on the setting characteristics of GIC and its physical properties in conjunction with the efficacy of its antibacterial activity and biocompatibility [3,12,88].

7. Conclusions

The inherent properties of the formation of a chemical bond at the tooth-restoration interface and the fluoride releasing and recharging abilities of GIC have caused this material to remain clinically important in dentistry. The area of bioactivity of GICs remains a topic of interest because of the promising results reported regarding their potential to further enhance the remineralisation and regenerative properties, adhesion by integration with tissues, and antibacterial activity. Improvement of these desirable properties of GICs is expected to be beneficial in preventing secondary caries and failures when used as cements and restorations. The enhancement of these properties will, in turn, improve the clinical survival rate when GIC is used to repair and replace lost and diseased dental tissues.

Several studies have aimed to promote the bioactivity of GICs using innovative strategies of modifying either or both the glass and liquid phases of this biomaterial using various additives. It is important that the incorporation of these modifiers into the GIC matrix does not compromise the physico-chemical properties. According to the literature summarised in this paper, several types of organic and inorganic materials can be added to GICs to enhance these desired properties, but they are dose-dependent. Conflicting reports regarding the use of bioactive glass and antimicrobial additives in promoting bioactivity and its effect on mechanical properties exist. Therefore, greater efforts are still required to optimise this glass modification to ensure bioactivity enhancement does not compromise mechanical properties. Clinical studies are needed following successful in vitro research on GIC modification for this improved material to be considered a clinically acceptable bioactive restorative material.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.D.; methodology, J.M. and S.D.; validation, J.M. and S.D.; investigation, J.M. and S.D.; resources, J.M. and S.D.; writing—original draft preparation, J.M.; writing—review, S.D.; writing—editing, J.M. and S.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Nicholson, J.W. Adhesion of glass-ionomer cements to teeth: A review. Int. J. Adhes. Adhes. 2016, 69, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Yan, Z.; Duan, Y.; Zhang, J.; Liu, B. Improvement of the mechanical, tribological and antibacterial properties of glass ionomer cements by fluorinated graphene. Dent. Mater. 2018, 34, e115–e127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ching, H.S.; Luddin, N.; Kannan, T.P.; Ab Rahman, I.; Ghani, N.R.N.A. Modification of glass ionomer cements on their physical-mechanical and antimicrobial properties. J. Esthet. Restor. Dent. 2018, 30, 557–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alatawi, R.A.; Elsayed, N.H.; Mohamed, W.S. Influence of hydroxyapatite nanoparticles on the properties of glass ionomer cement. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2019, 8, 344–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.-J.; Bae, H.E.; Lee, J.-E.; Park, I.-S.; Kim, H.-G.; Kwon, J.; Kim, D.-S. Effects of bioactive glass incorporation into glass ionomer cement on demineralized dentin. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 7016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griffin, S.; Hill, R. Influence of glass composition on the properties of glass polyalkenoate cements. Part II: Influence of phosphate content. Biomaterials 2000, 21, 399–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davidson, C.L. Advances in glass-ionomer cements. J. Appl. Oral Sci. 2006, 14, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidhu, S.K.; Nicholson, J.W. A Review of Glass-Ionomer Cements for Clinical Dentistry. J. Funct. Biomater. 2016, 7, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorseta, K.; Glavina, D.; Skrinjaric, T.; Czarnecka, B.; Nicholson, J.W. The effect of petroleum jelly, light-cured varnish and different storage media on the flexural strength of glass ionomer dental cements. Acta Biomater. Odontol. Scand. 2016, 2, 55–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholson, J.W. Maturation processes in glass-ionomer dental cements. Acta Biomater. Odontol. Scand. 2018, 4, 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholson, J.W. Chemistry of glass-ionomer cements: A review. Biomaterials 1998, 19, 485–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholson, J.W.; Sidhu, S.K.; Czarnecka, B. Enhancing the Mechanical Properties of Glass-Ionomer Dental Cements: A Review. Materials 2020, 13, 2510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borges, H.; Bandeca, M.C.; Guedes, O.A.; Nakatani, M.K.; Estrela, C.R.D.A.; De Alencar, A.H.G.; Estrela, C. Chemical and Structural Characterization of Glass Ionomer Cements indicated for Atraumatic Restorative Treatment. J. Contemp. Dent. Pract. 2015, 16, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, D.; Zhao, J.; Weng, Y.; Park, J.-G.; Jiang, H.; Platt, J.A. Bioactive glass-ionomer cement with potential therapeutic function to dentin capping mineralization. Eur. J. Oral Sci. 2008, 116, 479–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawashima, N.; Hashimoto, K.; Kuramoto, M.; Bakhit, A.; Wakabayashi, Y.; Okiji, T. A Novel Bioactive Endodontic Sealer Containing Surface-Reaction-Type Prereacted Glass-Ionomer Filler Induces Osteoblast Differentiation. Materials 2020, 13, 4477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyaji, H.; Mayumi, K.; Miyata, S.; Nishida, E.; Shitomi, K.; Hamamoto, A.; Tanaka, S.; Akasaka, T. Comparative biological assessments of endodontic root canal sealer containing surface pre-reacted glass-ionomer (S-PRG) filler or silica filler. Dent. Mater. J. 2020, 39, 287–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shirazi, M.; Sadeghi, M. The evaluation of shear bond strength of resin-modified glass ionomer cement with the addition of 45S5 bioactive glass using two conventional methods. J. Oral Res. 2020, 9, 250–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholson, J.W.; Coleman, N.J.; Sidhu, S.K. Kinetics of ion release from a conventional glass-ionomer cement. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 2021, 32, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvo, A.F.B.; Kicuti, A.; Tedesco, T.K.; Braga, M.M.; Raggio, D.P. Evaluation of the relationship between the cost and properties of glass ionomer cements indicated for atraumatic restorative treatment. Braz. Oral Res. 2016, 30, e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kutuk, Z.B.; Vural, U.K.; Cakir, F.Y.; Miletic, I.; Gurgan, S. Mechanical properties and water sorption of two experimental glass ionomer cements with hydroxyapatite or calcium fluorapatite formulation. Dent. Mater. J. 2019, 38, 471–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, A. The Role of Glass-Ionomer Cements in Minimum Intervention (MI) Caries Management. In Glass-Ionomers in Dentistry; Sidhu, S., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 81–96. [Google Scholar]

- Poggio, C.; Beltrami, R.; Scribante, A.; Colombo, M.; Lombardini, M. Effects of dentin surface treatments on shear bond strength of glass-ionomer cements. Ann. Stomatol. 2014, 5, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toledano, M.; Osorio, R.; Vallecillo-Rivas, M.; Osorio, E.; Lynch, C.D.; Aguilera, F.S.; Toledano, R.; Sauro, S. Zn-doping of silicate and hydroxyapatite-based cements: Dentin mechanobiology and bioactivity. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2020, 114, 104232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sidhu, S.K. Glass-ionomer cement restorative materials: A sticky subject? Aust. Dent. J. 2011, 56, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobh, E.; Hamama, H.; Palamara, J.; Mahmoud, S.; Burrow, M. Effect of CPP-ACP modified-GIC on prevention of demineralization in comparison to other fluoride-containing restorative materials. Aust. Dent. J. 2022, 67, 220–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Caluwé, T.; Vercruysse, C.W.J.; Fraeyman, S.; Verbeeck, R.M.H. The influence of particle size and fluorine content of aluminosilicate glass on the glass ionomer cement properties. Dent. Mater. 2014, 30, 1029–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmons, J.O.; Meyers, E.J.; Lien, W.; Banfield, R.L.; Roberts, H.W.; Vandewalle, K.S. Effect of surface treatments on the mechanical properties and antimicrobial activity of desiccated glass ionomers. Dent. Mater. 2016, 32, 1343–1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farrugia, C.; Camilleri, J. Antimicrobial properties of conventional restorative filling materials and advances in antimicrobial properties of composite resins and glass ionomer cements—A literature review. Dent. Mater. 2015, 31, e89–e99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafshejani, T.M.; Zamanian, A.; Venugopal, J.R.; Rezvani, Z.; Sefat, F.; Saeb, M.R.; Vahabi, H.; Zarrintaj, P.; Mozafari, M. Antibacterial glass-ionomer cement restorative materials: A critical review on the current status of extended release formulations. J. Control. Release 2017, 262, 317–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yesilyurt, C.; Er, K.; Tasdemir, T.; Buruk, K.; Celik, D. Antibacterial Activity and Physical Properties of Glass-ionomer Cements Containing Antibiotics. Oper. Dent. 2009, 34, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCabe, J.F.; Yan, Z.; Al Naimi, O.T.; Mahmoud, G.; Rolland, S.L. Smart materials in dentistry. Aust. Dent. J. 2011, 56, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guida, A.; Towler, M.R.; Wall, J.G.; Hill, R.; Eramo, S. Preliminary work on the antibacterial effect of strontium in glass ionomer cements. J. Mater. Sci. Lett. 2003, 22, 1401–1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okada, K.; Tosaki, S.; Hirota, K.; Hume, W. Surface hardness change of restorative filling materials stored in saliva. Dent. Mater. 2000, 17, 34–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Z.-Y.; Noh, I.-S.; Zhang, S.-M. Silicate-doped hydroxyapatite and its promotive effect on bone mineralization. Front. Mater. Sci. 2013, 7, 40–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Caluwé, T.; Vercruysse, C.W.J.; Ladik, I.; Convents, R.; Declercq, H.; Martens, L.C.; Verbeeck, R.M.H. Addition of bioactive glass to glass ionomer cements: Effect on the physico-chemical properties and biocompatibility. Dent. Mater. 2017, 33, e186–e203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.-A.; Lee, J.-H.; Jun, S.-K.; Kim, H.-W.; Eltohamy, M.; Lee, H.-H. Sol–gel-derived bioactive glass nanoparticle-incorporated glass ionomer cement with or without chitosan for enhanced mechanical and biomineralization properties. Dent. Mater. 2017, 33, 805–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, I.S.; Mei, M.L.; Zhou, Z.L.; Burrow, M.F.; Lo, E.C.-M.; Chu, C.-H. Shear Bond Strength and Remineralisation Effect of a Casein Phosphopeptide-Amorphous Calcium Phosphate-Modified Glass Ionomer Cement on Artificial “Caries-Affected” Dentine. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 1723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirthika, N.; Vidhya, S.; Sujatha, V.; Mahalaxmi, S.; Kumar, R.S. Comparative evaluation of compressive and flexural strength, fluoride release and bacterial adhesion of GIC modified with CPP-ACP, bioactive glass, chitosan and MDPB. J. Dent. Res. Dent. Clin. Dent. Prospect. 2021, 15, 16–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vallittu, P.K.; Boccaccini, A.R.; Hupa, L.; Watts, D.C. Bioactive dental materials—Do they exist and what does bioactivity mean? Dent. Mater. 2018, 34, 693–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, J.R. Review of bioactive glass: From Hench to hybrids. Acta Biomater. 2013, 9, 4457–4486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hench, L.L.; Xynos, I.D.; Polak, J.M. Bioactive glasses for in situ tissue regeneration. J. Biomater. Sci. Polym. Ed. 2004, 15, 543–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamdy, T.M. Bioactivity: A New Buzz in Dental Materials. EC Dent. Sci. 2018, 17, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Kokubo, T.; Takadama, H. How useful is SBF in predicting in vivo bone bioactivity? Biomaterials 2006, 27, 2907–2915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hench, L.L. Bioceramics: From Concept to Clinic. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 1991, 74, 1487–1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makanjuola, J.O.; Essien, E.R.; Bolasodun, B.O.; Umesi, D.C.; Oderinu, O.H.; Adams, L.A.; Adeyemo, W.L. A new hydrolytic route to an experimental glass for use in bioactive glass-ionomer cement. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2022, 18, 2013–2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moraes, J.F.; de Moraes, T.G.; Nunes, F.R.S.; Carvalho, E.M.; Nunes, G.S.; Carvalho, C.N.; Ardenghi, D.M.; Bauer, J. Formation of hydroxyapatite nanoprecursors by the addition of bioactive particles in resin-modified glass ionomer cements. Int. J. Adhes. Adhes. 2021, 110, 102933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ana, I.D.; Anggraeni, R. Development of bioactive resin modified glass ionomer cement for dental biomedical applications. Heliyon 2021, 7, e05944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bohner, M.; Lemaitre, J. Can bioactivity be tested in vitro with SBF solution? Biomaterials 2009, 30, 2175–2179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proença, M.A.M.; Carvalho, E.M.; e Silva, A.S.; Ribeiro, G.A.C.; Ferreira, P.V.C.; Carvalho, C.N.; Bauer, J. Orthodontic resin containing bioactive glass: Preparation, physicochemical characterization, antimicrobial activity, bioactivity and bonding to enamel. Int. J. Adhes. Adhes. 2020, 99, 102575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Shen, Y.; Haapasalo, M.; Wang, J.; Jiang, T.; Wang, Y.; Watson, T.F.; Sauro, S. Polycarboxylated microfillers incorporated into light-curable resin-based dental adhesives evoke remineralization at the mineral-depleted dentin. J. Biomater. Sci. Polym. Ed. 2014, 25, 679–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamitakahara, M.; Kamitakahara, M.; Kawashita, M.; Kokubo, T.; Nakamura, T. Effect of polyacrylic acid on the apatite formation of a bioactive ceramic in a simulated body fluid: Fundamental examination of the possibility of obtaining bioactive glass-ionomer cements for orthopaedic use. Biomaterials 2001, 22, 3191–3196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liou, S.C.; Chen, S.Y.; Liu, D.M. Synthesis and characterization of needlelike apatitic nanocomposite with controlled aspect ratios. Biomaterials 2003, 24, 3981–3988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Q.; Wang, X.M.; Tian, L.L.; Cheng, Z.J.; Cui, F.Z. In situ remineralizaiton of partially demineralized human dentine mediated by a biomimetic non-collagen peptide. Soft Matter 2011, 7, 9673–9680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ana, I.D.; Matsuya, S.; Ohta, M.; Ishikawa, K. Effects of added bioactive glass on the setting and mechanical properties of resin-modified glass ionomer cement. Biomaterials 2003, 24, 3061–3067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yli-Urpo, H.; Lassila, L.V.; Närhi, T.; Vallittu, P.K. Compressive strength and surface characterization of glass ionomer cements modified by particles of bioactive glass. Dent. Mater. 2005, 21, 201–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Cai, Y.; Engqvist, H.; Xia, W. Enhanced bioactivity of glass ionomer cement by incorporating calcium silicates. Biomatter 2016, 6, e1123842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alaohali, A.; Brauer, D.S.; Gentleman, E.; Sharpe, P.T. A modified glass ionomer cement to mediate dentine repair. Dent. Mater. 2021, 37, 1307–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, F.O.; Pires, R.A.; Reis, R.L. Aluminum-free glass-ionomer bone cements with enhanced bioactivity and biodegradability. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2013, 33, 1361–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaghani, M.; Alizadeh, S.; Doostmohammadi, A. Influence of Incorporating Fluoroapatite Nanobioceramic on the Compressive Strength and Bioactivity of Glass Ionomer Cement. J. Dent. Biomater. 2016, 3, 276. [Google Scholar]

- Prabhakar, A.R.; Paul, M.J.; Basappa, N. Comparative Evaluation of the Remineralizing Effects and Surface Microhardness of Glass Ionomer Cements Containing Bioactive Glass (S53P4): An in vitro Study. Int. J. Clin. Pediatr. Dent. 2010, 3, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valanezhad, A.; Odatsu, T.; Udoh, K.; Shiraishi, T.; Sawase, T.; Watanabe, I. Modification of resin modified glass ionomer cement by addition of bioactive glass nanoparticles. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 2015, 27, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.-Y.; Lee, H.-H.; Kim, H.-W. Bioactive sol–gel glass added ionomer cement for the regeneration of tooth structure. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 2008, 19, 3287–3294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sayyedan, F.S.; Fathi, M.; Edris, H.; Doostmohammadi, A.; Mortazavi, V.; Shirani, F. Fluoride release and bioactivity evaluation of glass ionomer: Forsterite nanocomposite. Dent. Res. J. 2013, 10, 452–459. [Google Scholar]

- Ranjani, M.S.; Kavitha, M.; Venkatesh, S. Comparative evaluation of osteogenic potential of conventional glass-ionomer cement with chitosan-modified glass-ionomer and bioactive glass-modified glass-ionomer cement—An In vitro study. Contemp. Clin. Dent. 2021, 12, 32–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zandi Karimi, A.; Rezabeigi, E.; Drew, R.A.L. Aluminum-free glass ionomer cements containing 45S5 Bioglass® and its bioglass-ceramic. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 2021, 32, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakar, W.Z.W.; Sajjad, A.; Mohamad, D.; Kannan, T. Various recent reinforcement phase incorporations and modifications in glass ionomer powder compositions: A comprehensive review. J. Int. Oral Health 2018, 10, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam Moheet, I.; Luddin, N.; Ab Rahman, I.; Kannan, T.P.; Ghani, N.R.N.A.; Masudi, S.M. Modifications of Glass Ionomer Cement Powder by Addition of Recently Fabricated Nano-Fillers and Their Effect on the Properties: A Review. Eur. J. Dent. 2019, 13, 470–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangsuwan, P.; Tannukit, S.; Chotigeat, W.; Kedjarune-Leggat, U. Biological Activities of Glass Ionomer Cement Supplemented with Fortilin on Human Dental Pulp Stem Cells. J. Funct. Biomater. 2022, 13, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hench, L.L. The story of Bioglass®. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 2006, 17, 967–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousavinasab, S.M.; Khoroushi, M.; Keshani, F.; Hashemi, S. Flexural strength and morphological characteristics of resin-modified glass-ionomer containing bioactive glass. J. Contemp. Dent. Pract. 2011, 12, 41–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Yang, T.; Zhao, S.; Huang, C.; Du, X. Anti-biofilm effect of glass ionomer cements incorporated with chlorhexidine and bioactive glass. J. Wuhan Univ. Technol.-Mater. Sci. Ed. 2012, 27, 270–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasaki, J.-I.; Kiba, W.; Abe, G.L.; Katata, C.; Hashimoto, M.; Kitagawa, H.; Imazato, S. Fabrication of strontium-releasable inorganic cement by incorporation of bioactive glass. Dent. Mater. 2019, 35, 780–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martins, R.A.; Marti, L.M.; Mendes, A.C.B.; Fragelli, C.; Cilense, M.; Zuanon, A.C.C. Brushing Effect on the Properties of Glass Ionomer Cement Modified by Hydroxyapatite Nanoparticles or by Bioactive Glasses. Int. J. Dent. 2022, 2022, 1641041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osorio, E.; Fagundes, T.; Navarro, M.F.; Zanotto, E.D.; Peitl, O.; Osorio, R.; Toledano-Osorio, M.; Toledano, M. A novel bioactive agent improves adhesion of resin-modified glass-ionomer to dentin. J. Adhes. Sci. Technol. 2015, 29, 1543–1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lusvardi, G.; Malavasi, G.; Menabue, L.; Aina, V.; Morterra, C. Fluoride-containing bioactive glasses: Surface reactivity in simulated body fluids solutions. Acta Biomater. 2009, 5, 3548–3562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, Y.; Kim, J.; Lee, B.; Lee, Y.K.; Choi, B.; Lee, J.H.; Choi, H. The Effect of Nano-Sized β-Tricalcium Phosphate on Remineralization in Glass Ionomer Dental Luting Cement. Key Eng. Mater. 2007, 361, 861–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, K.; Zheng, L.; Xing, J.; Chen, S.; Chen, R.; Ren, L. Mechanical, antibacterial, biocompatible and microleakage evaluation of glass ionomer cement modified by nanohydroxyapatite/polyhexamethylene biguanide. Dent. Mater. J. 2022, 41, 197–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farooq, I.; Alam Moheet, I.; AlShwaimi, E. In vitro dentin tubule occlusion and remineralization competence of various toothpastes. Arch. Oral Biol. 2015, 60, 1246–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luddin, N.; Hii, S.; Kannan, T.; Ab Rahman, I.; Ghani, N.R.N.A. The biological evaluation of conventional and nano-hydroxyapatite-silica glass ionomer cement on dental pulp stem cells: A comparative study. Contemp. Clin. Dent. 2019, 10, 324–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kheur, M.; Kantharia, N.; Iakha, T.; Kheur, S.; Husain, N.A.-H.; Özcan, M. Evaluation of mechanical and adhesion properties of glass ionomer cement incorporating nano-sized hydroxyapatite particles. Odontology 2019, 108, 66–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharafeddin, F.; Feizi, N. Evaluation of the effect of adding micro-hydroxyapatite and nano-hydroxyapatite on the microleakage of conventional and resin-modified Glass-ionomer Cl V restorations. J. Clin. Exp. Dent. 2017, 9, e242–e248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greish, Y.E.; Brown, P.W. Characterization of wollastonite-reinforced HAp-Ca polycarboxylate composites. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 2001, 55, 618–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wan, X.; Chang, C.; Mao, D.; Jiang, L.; Li, M. Preparation and in vitro bioactivities of calcium silicate nanophase materials. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2005, 25, 455–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzaoui, S.A.; Burrow, M.F.; Tyas, M.; Dashper, S.; Eakins, D.; Reynolds, E. Incorporation of Casein Phosphopeptide-Amorphous Calcium Phosphate into a Glass-ionomer Cement. J. Dent. Res. 2003, 82, 914–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moshaverinia, A.; Roohpour, N.; Chee, W.W.L.; Schricker, S.R. A review of powder modifications in conventional glass-ionomer dental cements. J. Mater. Chem. 2011, 21, 1319–1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zandi Karimi, A.; Rezabeigi, E.; Drew, R.A.L. Glass ionomer cements with enhanced mechanical and remineralizing properties containing 45S5 bioglass-ceramic particles. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2019, 97, 396–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ibrahim, M.A.; Neo, J.; Esguerra, R.J.; Fawzy, A.S. Characterization of antibacterial and adhesion properties of chitosan-modified glass ionomer cement. J. Biomater. Appl. 2015, 30, 409–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermeersch, G.; Leloup, G.; Delmee, M.; Vreven, J. Antibacterial activity of glass-ionomer cements, compomers and resin composites: Relationship between acidity and material setting phase. J. Oral Rehabil. 2005, 32, 368–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tüzüner, T.; Dimkov, A.; Nicholson, J.W. The effect of antimicrobial additives on the properties of dental glass-ionomer cements: A review. Acta Biomater. Odontol. Scand. 2019, 5, 9–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Taee, L.; Banerjee, A.; Deb, S. In-vitro adhesive and interfacial analysis of a phosphorylated resin polyalkenoate cement bonded to dental hard tissues. J. Dent. 2022, 118, 104050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsaka, S.E.; Hamouda, I.M.; Swain, M.V. Titanium dioxide nanoparticles addition to a conventional glass-ionomer restorative: Influence on physical and antibacterial properties. J. Dent. 2011, 39, 589–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, Y.; Imazato, S.; Kaneshiro, A.V.; Ebisu, S.; Frencken, J.E.; Tay, F.R. Antibacterial effects and physical properties of glass-ionomer cements containing chlorhexidine for the ART approach. Dent. Mater. 2006, 22, 647–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hook, E.R.; Owen, O.J.; Bellis, C.A.; Holder, J.A.; O’Sullivan, D.J.; Barbour, M.E. Development of a novel antimicrobial-releasing glass ionomer cement functionalized with chlorhexidine hexametaphosphate nanoparticles. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2014, 12, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tüzüner, T.; Kuşgöz, A.; Er, K.; Taşdemir, T.; Buruk, K.; Kemer, B. Antibacterial Activity and Physical Properties of Conventional Glass-ionomer Cements Containing Chlorhexidine Diacetate/Cetrimide Mixtures. J. Esthet. Restor. Dent. 2011, 23, 46–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, D.; Weng, Y.; Guo, X.; Zhao, J.; Gregory, R.L.; Zheng, C. Preparation and evaluation of a novel glass-ionomer cement with antibacterial functions. Dent. Mater. 2011, 27, 487–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noori, A.J.; Kareem, F.A. The effect of magnesium oxide nanoparticles on the antibacterial and antibiofilm properties of glass-ionomer cement. Heliyon 2019, 5, e02568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ibrahim, M.A.; Priyadarshini, B.M.; Neo, J.; Fawzy, A.S. Characterization of Chitosan/TiO2 Nano-Powder Modified Glass-Ionomer Cement for Restorative Dental Applications. J. Esthet. Restor. Dent. 2017, 29, 146–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duque, C.; Aida, K.L.; Pereira, J.A.; Teixeira, G.S.; Caldo-Teixeira, A.S.; Perrone, L.R.; Caiaffa, K.S.; Negrini, T.D.C.; Castilho, A.; Costa, C.A.D.S. In vitro and in vivo evaluations of glass-ionomer cement containing chlorhexidine for Atraumatic Restorative Treatment. J. Appl. Oral Sci. 2017, 25, 541–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marti, L.M.; Da Mata, M.; Ferraz-Santos, B.; Azevedo, E.R.; Giro, E.M.A.; Zuanon, A.C.C. Addition of Chlorhexidine Gluconate to a Glass Ionomer Cement: A Study on Mechanical, Physical and Antibacterial Properties. Braz. Dent. J. 2014, 25, 33–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoszek, A.; Ericson, D. In Vitro Fluoride Release and the Antibacterial Effect of Glass Ionomers Containing Chlorhexidine Gluconate. Oper. Dent. 2008, 33, 696–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Türkün, L.S.; Türkün, M.; Ertuğrul, F.; Ates¸, M.; Brugger, S. Long-Term Antibacterial Effects and Physical Properties of a Chlorhexidine-Containing Glass Ionomer Cement. J. Esthet. Restor. Dent. 2008, 20, 29–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, B.J.; Gregory, R.L.; Moore, K.; Avery, D.R. Antibacterial and physical properties of resin modified glass-ionomers combined with chlorhexidine. J. Oral Rehabil. 2002, 29, 553–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deepalakshmi, M.; Poorni, S.; Miglani, R.; Rajamani, I.; Ramachandran, S. Evaluation of the antibacterial and physical properties of glass ionomer cements containing chlorhexidine and cetrimide: An in-vitro study. Indian J. Dent. Res. 2010, 21, 552–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duque, C.; Negrini, T.D.C.; Hebling, J.; Spolidorio, D.M.P. Inhibitory activity of glass-ionomer cements on cariogenic bacteria. Oper. Dent. 2005, 30, 636–640. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Korkmaz, F.M.; Tüzüner, T.; Baygin, O.; Buruk, C.K.; Durkan, R.; Bagis, B. Antibacterial activity, surface roughness, flexural strength, and solubility of conventional luting cements containing chlorhexidine diacetate/cetrimide mixtures. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2013, 110, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botelho, M.G. Inhibitory Effects on Selected Oral Bacteria of Antibacterial Agents Incorporated in a Glass Ionomer Cement. Caries Res. 2003, 37, 108–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Botelho, M.G. Compressive strength of glass ionomer cements with dental antibacterial agents. S. Afr. Dent. J. 2004, 59, 51–53. [Google Scholar]

- Dimkov, A.G.; Nicholson, J.W.; Gjorgievska, E.S. Physical and mechanical properties of conventional glass ionomer cement incorporated with cationic substances. Acta Stomatol. Naissi 2021, 37, 2125–2135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittal, S.; Soni, H.; Sharma, D.K.; Mittal, K.; Pathania, V.; Sharma, S. Comparative evaluation of the antibacterial and physical properties of conventional glass ionomer cement containing chlorhexidine and antibiotics. J. Int. Soc. Prev. Community Dent. 2015, 5, 268–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celik, E.U.; Tunac, A.T.; Ates, M.; Sen, B.H. Antimicrobial activity of different disinfectants against cariogenic microorganisms. Braz. Oral Res. 2016, 30, e125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrazzano, G.F.; Amato, I.; Ingenito, A.; Zarrelli, A.; Pinto, G.; Pollio, A. Plant Polyphenols and Their Anti-Cariogenic Properties: A Review. Molecules 2011, 16, 1486–1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinmann, J.; Buer, J.; Pietschmann, T.; Steinmann, E. Anti-infective properties of epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG), a component of green tea. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2013, 168, 1059–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reygaert, W.C. The antimicrobial possibilities of green tea. Front. Microbiol. 2014, 5, 434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, J.; Du, X.; Huang, C.; Fu, D.; Ouyang, X.; Wang, Y. Antibacterial and physical properties of EGCG-containing glass ionomer cements. J. Dent. 2013, 41, 927–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prentice, L.; Tyas, M.; Burrow, M. The effect of particle size distribution on an experimental glass-ionomer cement. Dent. Mater. 2005, 21, 505–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lucas, M.E.; Arita, K.; Nishino, M. Toughness, bonding and fluoride-release properties of hydroxyapatite-added glass ionomer cement. Biomaterials 2003, 24, 3787–3794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, M.A.; Costa, L.R. Clinical performance of CTZ pulpotomies in deciduous molars: A retrospective study. Rev. Odontol. Bras. Cent. 2006, 15, 37–45. [Google Scholar]

- Hayacibara, M.F.; Koo, H.; Rosalen, P.L.; Duarte, S.; Franco, E.M.; Bowen, W.H.; Ikegaki, M.; Cury, J.A. In vitro and in vivo effects of isolated fractions of Brazilian propolis on caries development. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2005, 101, 110–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topcuoglu, N.; Ozan, F.; Ozyurt, M.; Kulekci, G. In vitro antibacterial effects of glassionomer cement containing ethanolic extract of propolis on Streptococcus mutans. Eur. J. Dent. 2012, 6, 428–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altunsoy, M.; Tanrıver, M.; Türkan, U.; Uslu, M.E.; Silici, S. In Vitro Evaluation of Microleakage and Microhardness of Ethanolic Extracts of Propolis in Different Proportions Added to Glass Ionomer Cement. J. Clin. Pediatr. Dent. 2016, 40, 136–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanić, V.; Tanasković, S.B. Antibacterial activity of metal oxide nanoparticles. In Nanotoxicity; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 241–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khezerlou, A.; Alizadeh-Sani, M.; Azizi-Lalabadi, M.; Ehsani, A. Nanoparticles and their antimicrobial properties against pathogens including bacteria, fungi, parasites and viruses. Microb. Pathog. 2018, 123, 505–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paiva, L.; Fidalgo, T.K.S.; da Costa, L.P.; Maia, L.C.; Balan, L.; Anselme, K.; Ploux, L.; Thiré, R.M.S.M. Antibacterial properties and compressive strength of new one-step preparation silver nanoparticles in glass ionomer cements (NanoAg-GIC). J. Dent. 2018, 69, 102–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kantovitz, K.R.; Fernandes, F.P.; Feitosa, I.V.; Lazzarini, M.O.; Denucci, G.C.; Gomes, O.P.; Giovani, P.A.; Moreira, K.M.S.; Pecorari, V.G.A.; Borges, A.F.S.; et al. TiO2 nanotubes improve physico-mechanical properties of glass ionomer cement. Dent. Mater. 2020, 36, e85–e92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aguilar-Perez, D.; Vargas-Coronado, R.; Cervantes-Uc, J.M.; Rodriguez-Fuentes, N.; Aparicio, C.; Covarrubias, C.; Alvarez-Perez, M.; Garcia-Perez, V.; Martinez-Hernandez, M.; Cauich-Rodriguez, J.V. Antibacterial activity of a glass ionomer cement doped with copper nanoparticles. Dent. Mater. J. 2020, 39, 389–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malekhoseini, Z.; Rezvani, M.B.; Niakan, M.; Atai, M.; Mohammadi Bassir, M.; Alizade, H.S.; Siabani, S. Effect of zinc oxide nanoparticles on physical and antimicrobial properties of resin-modified glass ionomer cement. Dent. Res. J. 2021, 18, 73. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia, P.P.N.S.; Cardia, M.F.B.; Francisconi, R.S.; Dovigo, L.N.; Spolidório, D.M.P.; Rastelli, A.N.D.S.; Botta, A.C. Antibacterial activity of glass ionomer cement modified by zinc oxide nanoparticles. Microsc. Res. Tech. 2016, 80, 456–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jowkar, Z.; Fattah, Z.; Ghanbarian, S.; Shafiei, F. The Effects of Silver, Zinc Oxide, and Titanium Dioxide Nanoparticles Used as Dentin Pretreatments on the Microshear Bond Strength of a Conventional Glass Ionomer Cement to Dentin. Int. J. Nanomed. 2020, 15, 4755–4762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noori, A.J.; Kareem, F.A. Setting time, mechanical and adhesive properties of magnesium oxide nanoparticles modified glass-ionomer cement. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2019, 9, 1809–1818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dizaj, S.M.; Lotfipour, F.; Barzegar-Jalali, M.; Zarrintan, M.H.; Adibkia, K. Antimicrobial activity of the metals and metal oxide nanoparticles. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2014, 44, 278–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, H.; Sun, H.; Qu, X. Antibacterial applications of graphene-based nanomaterials: Recent achievements and challenges. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2016, 105, 176–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Lee, W.C.; Manga, K.K.; Ang, P.K.; Lu, J.; Liu, Y.P.; Lim, C.T.; Loh, K.P. Fluorinated graphene for promoting neuro-induction of stem cells. Adv. Mater. 2012, 24, 4285–4290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Wang, E.; Guo, Y.; Zhou, Q.; Zheng, Y.; Zhai, J.; Zhang, K.; Zhang, B. Enhanced antibacterial properties and promoted cell proliferation in glass ionomer cement by modified with fluorinated graphene-doped. J. Appl. Biomater. Funct. Mater. 2021, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, X.; Huang, X.; Huang, C.; Frencken, J.; Yang, T. Inhibition of early biofilm formation by glass-ionomer incorporated with chlorhexidine in vivo: A pilot study. Aust. Dent. J. 2012, 57, 58–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sainulabdeen, S.; Neelakantan, P.; Ramesh, S.; Subbarao, C. Antibacterial Activity of Triclosan Incorporated Glass Ionomer Cements—An in vitro Pilot Study. J. Clin. Pediatr. Dent. 2010, 35, 157–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Somani, R.; Jaidka, S.; Jawa, D.; Mishra, S. Comparative evaluation of microleakage in conventional glass ionomer cements and triclosan incorporated glass ionomer cements. Contemp. Clin. Dent. 2014, 5, 85–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somani, R.; Jaidka, S.; Singh, D.J.; Sibal, G.K. Comparative Evaluation of Shear Bond Strength of Conventional Type II Glass Ionomer Cement and Triclosan Incorporated Type II Glass Ionomer Cement: An In Vitro Study. Adv. Hum. Biol. 2015, 5, 88–92. [Google Scholar]

- Prabhakar, A.R.; Prahlad, D.; Kumar, S.R. Antibacterial Activity, Fluoride Release, and Physical Properties of an Antibiotic- modified Glass Ionomer Cement. Pediatr. Dent. 2013, 35, 411–415. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Debnath, A.; Kesavappa, S.B.; Singh, G.P.; Eshwar, S.; Jain, V.; Swamy, M.; Shetty, P. Comparative evaluation of antibacterial and adhesive properties of chitosan modified glass ionomer cement and conventional glass ionomer cement: An in vitro study. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2017, 11, ZC75–ZC78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, R.K.; Mishra, A.; Manickam, N. Antibacterial effect and physical properties of chitosan and chlorhexidine-cetrimide-modified glass ionomer cements. J. Indian Soc. Pedod. Prev. Dent. 2017, 35, 28–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Li, Z.; Liu, G.; He, H. Long-term antibacterial properties and bond strength of experimental nano silver-containing orthodontic cements. J. Wuhan Univ. Technol. Sci. Ed. 2013, 28, 849–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Zhao, Q.; Peng, J.; Yang, X.; Yu, D.; Zhao, W. Antibacterial and mechanical properties of reduced graphene-silver nanoparticle nanocomposite modified glass ionomer cements. J. Dent. 2020, 96, 103332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Contreras, R.; Scougall-Vilchis, R.J.; Contreras-Bulnes, R.; Sakagami, H.; Morales-Luckie, R.A.; Nakajima, H. Mechanical, antibacterial and bond strength properties of nano-titanium-enriched glass ionomer cement. J. Appl. Oral Sci. 2015, 23, 321–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Xu, Y.; Zhu, B.; Gao, G.; Ren, J.; Wang, H.; Lin, Y.; Cao, B. Synergistic effects of titanium dioxide and cellulose on the properties of glassionomer cement. Dent. Mater. J. 2019, 38, 41–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vanajassun, P.P.; Nivedhitha, M.S.; Nishad, N.T.; Soman, D. Effects of zinc oxide nanoparticles in combination with conventional glass ionomer cement: In vitro study. Adv. Hum. Biol. 2014, 4, 31–36. [Google Scholar]

- Hosida, T.Y.; Delbem, A.C.B.; Morais, L.A.; Moraes, J.C.S.; Duque, C.; Souza, J.A.S.; Pedrini, D. Ion release, antimicrobial and physio-mechanical properties of glass ionomer cement containing micro or nanosized hexametaphosphate, and their effect on enamel demineralization. Clin. Oral Investig. 2018, 23, 2345–2354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).