Abstract

Passenger transport companies have often been affected by fires in their vehicles, causing considerable damage. As a result, it is important to study the causes and effects of these fires, as well as to define the maintenance policies and strategies to be implemented to minimize the probability of this type of accident occurring. The support for this paper was based on the study of an accident that occurred in Portugal involving a passenger bus that suffered a fire in the engine compartment, which spread to the passenger compartment and caused the destruction of the vehicle, with no personal injuries. This study used infrared image analysis technology, oil ignition temperature analysis, maintenance history, accident history and operator interviews to determine the possible cause of the ignition. It was found that the cause was due to oil leaks from the engine compartment cooling system. The present communication will share a set of explanatory elements of the circumstances in which the accident occurred. In addition to identifying the causes of the accident, the study warns of the importance of more effective and efficient maintenance, particularly when using Condition Based Maintenance (CBM), including periodic visual inspections of the various mechanical and electrical components that make up the vehicles. The conclusions presented in the study also show that these events are not unrelated to the poor or even non-existent maintenance policy for the entire fleet, including the applicable standards.

1. Introduction

The main objective of this paper is to study the causes and effects of passenger transport vehicle fires, as well as to define the maintenance policies and strategies to be implemented to minimize the probability of this type of accident occurring.

Until the early 1970s, most industrial units performed maintenance reactively, after a breakdown shutdown—so-called corrective maintenance.

The advent of computers led many companies to implement systematic preventive maintenance strategies. This approach, still prevalent today, typically uses maintenance planning programmes to control calendar-based maintenance activities and automatically trigger work orders.

In the late 1970s, the concept of Reliability Centred Maintenance (RCM) emerged to reduce the growing volume of work orders resulting from computerized planning. The first RCM procedures were heavily influenced by safety factors, having originated in the aircraft industry. Around the same time, a maintenance philosophy called Total Productive Maintenance (TPM) was gaining traction among Japanese manufacturers. TPM advocates a partnership between production and maintenance, so that basic maintenance operations (cleaning and inspections) are performed by machine operators.

In the mid-1980s, technological advances in instrumentation and the emergence of the personal computer enabled the ability to predict machine problems by measuring their condition through vibration, temperature, and ultrasound sensors. This technology is often referred to as Predictive Maintenance (PdM) based on condition control. Another more advanced maintenance strategy, called Proactive Maintenance, allows machine failure cycles to be extended by systematically removing failure sources.

In the early 1990s, the Reliability-Based Maintenance approach was introduced, effectively combining the strengths of all these strategies and philosophies into a single maintenance system.

As we review the history of maintenance, it is interesting to note that from the industrial era until the 1970s, the maintenance function had evolved very little, as there were no improvement strategies. The term Condition Based Maintenance (CBM) emerged in the 1970s and 1980s to designate a new approach to preventive maintenance, based on knowledge of the actual condition of machines through the implementation of a condition monitoring system.

This involves deciding when to intervene in equipment based on knowledge of its actual condition. That is, instead of performing planned maintenance work at fixed intervals, as in systematic way, it is performed at variable intervals, determined by the condition of the equipment. CBM, therefore, focuses on individual equipment, replacing inspections at fixed intervals with inspections at fixed intervals. The economic advantages of CBM arise from gains in reduced production losses due to increased equipment availability and gains in reduced maintenance costs.

CBM can lead to the following benefits:

- Increased bus operator safety;

- Increased bus availability;

- Reduced maintenance costs;

- Greater efficiency in operating facilities and equipment, allowing production volume to be adjusted to the conditions of the facilities and equipment and achieving an appropriate level of quality;

- Greater capacity for dialogue with equipment manufacturers and/or repairers, based on knowledge gained from condition control;

- Better customer relations due to reduced unforeseen production downtime;

- Possibilities for improving the specifications and design of future facilities and equipment.

There are several asset condition control techniques (with application in maintenance), including the following:

- Vibration analysis;

- Thermography;

- Performance parameter analysis;

- Visual inspection;

- Ultrasonic measurements;

- Oil analysis.

Among the various maintenance techniques, visual inspection, thermography, and oil analysis stand out, as they are used in this case study.

Thus, considering the EN 13306:2021 standard [1], maintenance is defined as “the combination of all technical, administrative and management actions, during the life cycle of an asset, aimed at maintaining or restoring it to a state in which it can fulfil its required function.”

According to standard EN 13306:2021 [1], Condition Based Maintenance (CBM) or conditioned maintenance is defined as follows: “Preventive maintenance includes physical condition assessment, analysis and possible resulting maintenance actions. Condition assessment can be carried out by operator observation, and/or inspection, and/or testing, and/or condition monitoring of system parameters, etc., conducted according to a programmed, on-demand or continuously.” Regarding CBM, and specifically oil analysis, a number of studies have been carried out, which are referenced by the following authors: [2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12].

Other studies dealing with maintenance have been carried out related to the importance of public bus transport, emphasizing the relevance of carrying out life cycle assessment and maintenance management based on key performance indicators [13,14].

Millions of people travel safely by bus every day to and from work, school and leisure activities. Buses are thought to be among the safest forms of public transportation, but a fire caused by a collision or component failure endangers lives and affects both operational expenses and customer trust [15]. The public’s concern over transit bus fires has grown globally, mostly due to the significant loss of life and property they are linked to [16].

Several other studies have been carried out concerning the reasons related to buses catching on fire in different countries worldwide [17,18,19,20,21,22]. The authors agree that improving maintenance and inspections can reduce drastically the number of fires.

Other studies were presented to build systems that would detect fires and extinguish them; some authors emphasize that this is even happening in newer buses [23,24,25,26].

Raposo et al. [10] presented a study on urban bus engine oils, in which the evolution of their degradation was monitored to assess the potential impact of a CBM policy on urban bus fleet management companies [10,11]. By analyzing the lubricants in use, valuable information can be gathered about the operating conditions of the engines, which is essential for preventing this type of accident (fires). Based on this information, it is possible to assess the condition of the engines, determine the most appropriate time to replace them and, in addition, obtain a diagnosis of the state of the equipment and its progress. This monitoring of the degradation of lubricating oils also increases the safe operation of vehicles (buses), reduces faults and their costs and improves the efficiency of the vehicle, thus preventing the occurrence of vehicle fires, which often result in the total loss of the vehicle [27].

So, on 27 September, at 11:35 a.m., a bus on route X, with 20 passengers on board, was travelling, just before reaching stop “Y”, when an anomaly occurred that led the driver to stop the vehicle and get out to find out what had happened.

According to the testimony, the driver heard a bang coming from the rear of the vehicle, which he thought might have been due to a tyre bursting. Although he did not see any sign of an anomaly on the dashboard, he stopped the vehicle next to the bus stop, opened the front door and went out towards the back, leaving the engine running. Before leaving, or while travelling, he heard a passenger say that she smelled something burning. He inspected the rear wheels on both sides, finding no signs of damage to the tyres, and was returning to continue his journey when, as he was passing on the right-hand side next to the air passage grille for the engine cooling system, intercooler and hydraulic system, he noticed smoke coming from the front of the grille. Peering round, he saw a flame in the area behind the hydraulic motor of the cooling fan further forward in the vehicle. He then went to his seat, opened the exit doors for the passengers and told them to get out. The passengers all got out without a hitch. As far as we could tell, the passengers got out before there was any smoke or flames in their compartment.

The driver switched off the engine, collected the fire extinguisher and went to the back of the vehicle to try to fight the fire. Although he had used the extinguisher completely, he was unable to put out the fire, which grew to large proportions. At the back of the vehicle, on the right-hand side, a pool of oil was forming, which was being fed in gulps from the reservoir and hydraulic system mentioned above. The oil was on fire.

At the scene of the accident, the road had a positive gradient, i.e., it was travelling uphill. As a result, the oil and other liquids spilt onto the ground because of the fire, flowing out of the perimeter occupied by the vehicle and, particularly, out of the engine area. Even so, the fire inside the engine compartment—possibly fuelled by the combustion of combustible liquids spread on the ground—developed to such an extent that it completely destroyed all of the vehicle’s mechanical components in that area.

At the same time, the smoke and then the flames entered the passenger compartment, which was empty in the meantime, through a cable routing duct and air conditioning ducts and, in a few minutes, consumed all the combustible materials inside along its entire length.

Even considering the high calorific power developed by the combustion in the engine compartment, the ease with which the fire spread to the passenger compartment and the degree of destruction of the plastic material of the seats and decorative or functional elements of the vehicle’s interior is striking (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Exterior view of the engine compartment of the bus.

Coimbra Fire Brigade, whose station is less than 400 metres from the scene of the accident—on the opposite road—intervened a few minutes after the fire started but could do nothing to save the vehicle, which was rendered unusable (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Photos of the damaged vehicle.

It should be noted that on the day of the accident, the air temperature was 21 °C and there was practically no wind at the site. The road on which the accident occurred was a wide avenue, with no buildings near the carriageway and no large numbers of people on the pavements. We cannot help but wonder about the possible scale and consequences of an accident of this nature if the following circumstances were to occur:

- A road in an area with high-rise residential buildings close to the carriageway;

- A carriageway with high pedestrian traffic near the accident site;

- A carriageway with other vehicles in circulation, particularly public passenger transport vehicles or vehicles carrying dangerous loads;

- A vehicle with a larger number of passengers, some of whom may have mobility limitations;

- Driving in a sensitive area, such as next to an industrial site, next to a petrol station or inside an airport.

Although some of the above scenarios are not plausible in Coimbra, they can occur relatively easily in other cities where these vehicles are used. The possibility of their occurrence, either separately or together, should be a matter for reflection and caution on the part of the responsible authorities and, by itself, justifies carrying out a study such as this one, aimed at finding the causes of the accident and proposing procedures to be taken to avoid it.

2. Methodology

The above-mentioned investigation focused on the problem and analyzed the data provided by the transport company and the data that was researched. The first step was to gather as much information as possible about the accident and the vehicle, including the occurrence of similar accidents in vehicles of the same brand and model.

Visits were made to the transport company’s premises for a meeting with the people in charge of Transport Services and to inspect the vehicle that had been involved in the accident, as well as another of the same brand and model that had caught fire before the vehicle under study. Temperature measurement tests were carried out on an identical vehicle using an infrared camera. The driver of the accident vehicle was also interviewed.

Bearing in mind that there are at least two other major urban transport operators that use Brand A, Model X vehicles, Carris Bus and Porto Public Transport Services (STCP), following contacts with these two organizations, a meeting was held to discuss their experience of using these vehicles and the circumstances in which accidents of the same type had occurred.

To ascertain whether the oil in the hydraulic motors of the engine cooling system, intercooler and hydraulic system was ignited or self-ignited, a sample of the oil used was requested from the services for laboratory tests.

3. Case Study Discussion

The Municipalized Urban Transport Services of Coimbra (SMTUC), a public transportation company that recently celebrated its centennial anniversary, has consistently provided its users with improved transportation conditions (air-conditioned, less polluting buses, equipped with access ramps for citizens with reduced mobility, etc.), aiming to provide greater convenience and comfort to its passengers.

However, despite the implementation of these measures, it is essential to keep in mind that the quality of the services provided depends, in large part, on efficient maintenance management, based on innovative policies that contribute to increased user satisfaction.

It is in this context that this case study originated. Although its primary objective was to analyze, study, and audit a fire involving a bus in the SMTUC fleet, this fire clearly went beyond the boundaries of Coimbra’s urban transportation sector, and thus has the potential to be generalized to any national and international company. Therefore, for decades, many organizations focused much of their attention on offering products and services, often ignoring the maintenance function, which was seen as a necessary evil. In recent years, there has been a gradual shift in attitude, with managers also viewing the maintenance function as a fundamental necessity for service quality. One of the most important factors driving this shift has been the fact that maintenance departments have become significant cost centres within organizations.

With overall operating costs rising at high annual rates, the potential for achieving significant savings in the maintenance department has emerged through the implementation of advanced maintenance management practices, which have led to significant savings strategies being outlined.

Over the years, various models and methods of good maintenance practices have been developed to assess and support fleet performance, including unplanned maintenance, CBM and Predictive Maintenance (PdM). Recently, major operators in vast urban areas have introduced several added benefits, such as vehicle self-diagnostic systems, Reliability Centred Maintenance (RCM), online data transmission, driver operating condition monitoring, and cost control.

Urban transportation companies always have a certain bus reservation rate, which varies from company to company. A low reservation rate is synonymous with high reliability, based essentially on the implementation of an efficient planned maintenance plan, which results in the application of regular inspection methodologies that lead to the evaluation and replacement of parts in a continuous and timely overhaul programme.

Managers have confirmed that the useful life of each component of a piece of equipment or system varies significantly, meaning that, over its life cycle, a bus may require, for example, two engines, four transmissions, and body painting every three years. Lifespan also varies by vehicle type and geographic location of the network operated. In response to new fleet management challenges, many companies have been introducing new practices that are resulting in cost reductions. This has allowed them to increase efficiency, allowing them to manage within established guidelines for reserve rates. Many of them have introduced strategies that have improved reliability and reduced bus maintenance time.

Other companies are actively seeking new techniques and processes to improve their fleet management, opting to send their personnel to other companies where new strategies are already implemented. The model is based on a maintenance information system that provides the history of each bus, by brand, model, and individual vehicle. This information enables rapid problem-solving across the entire fleet by identifying anomalies detected in individual vehicles. Many of the best practices also involve having better training programmes that prepare maintenance personnel to become autonomous and skilled mechanics.

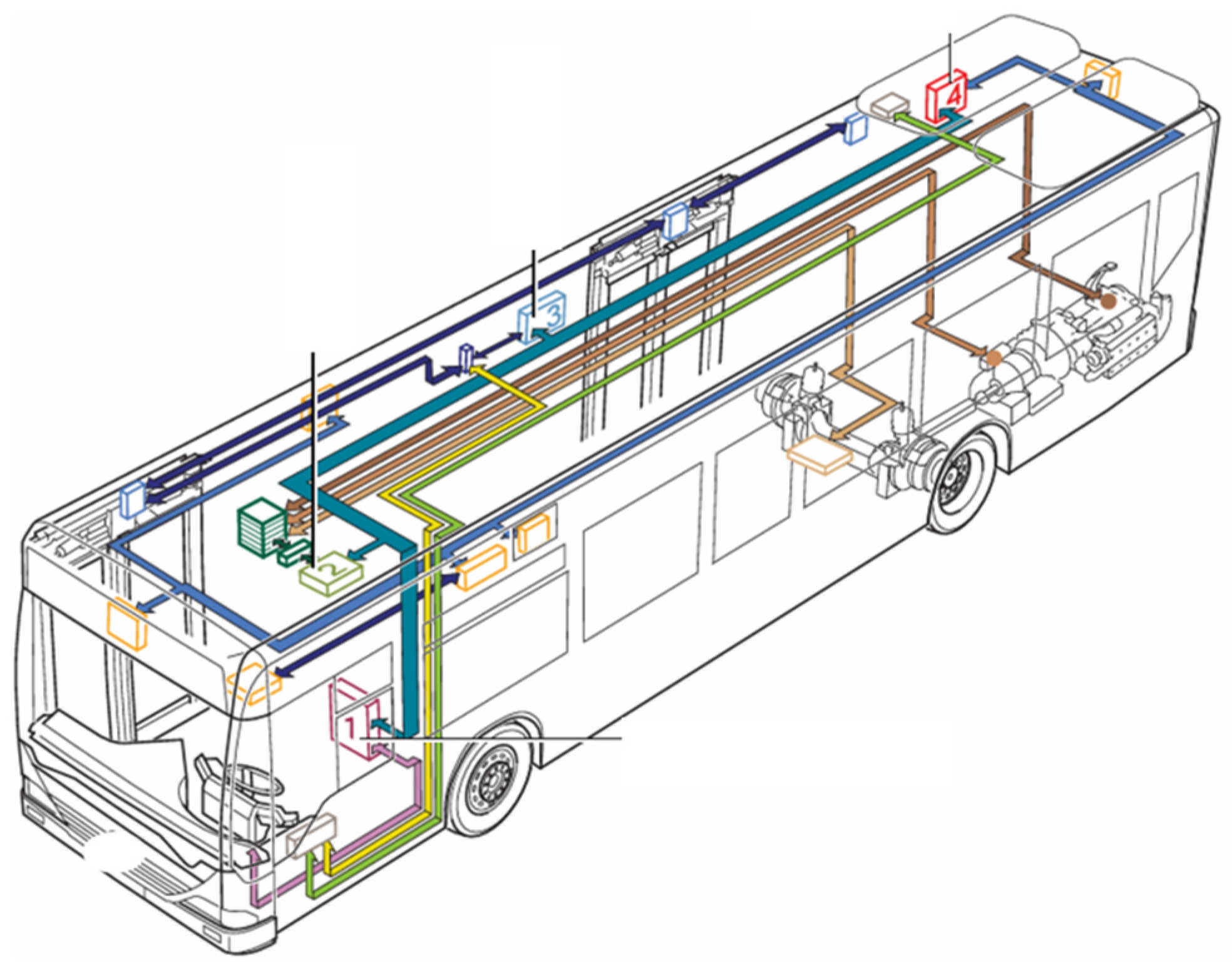

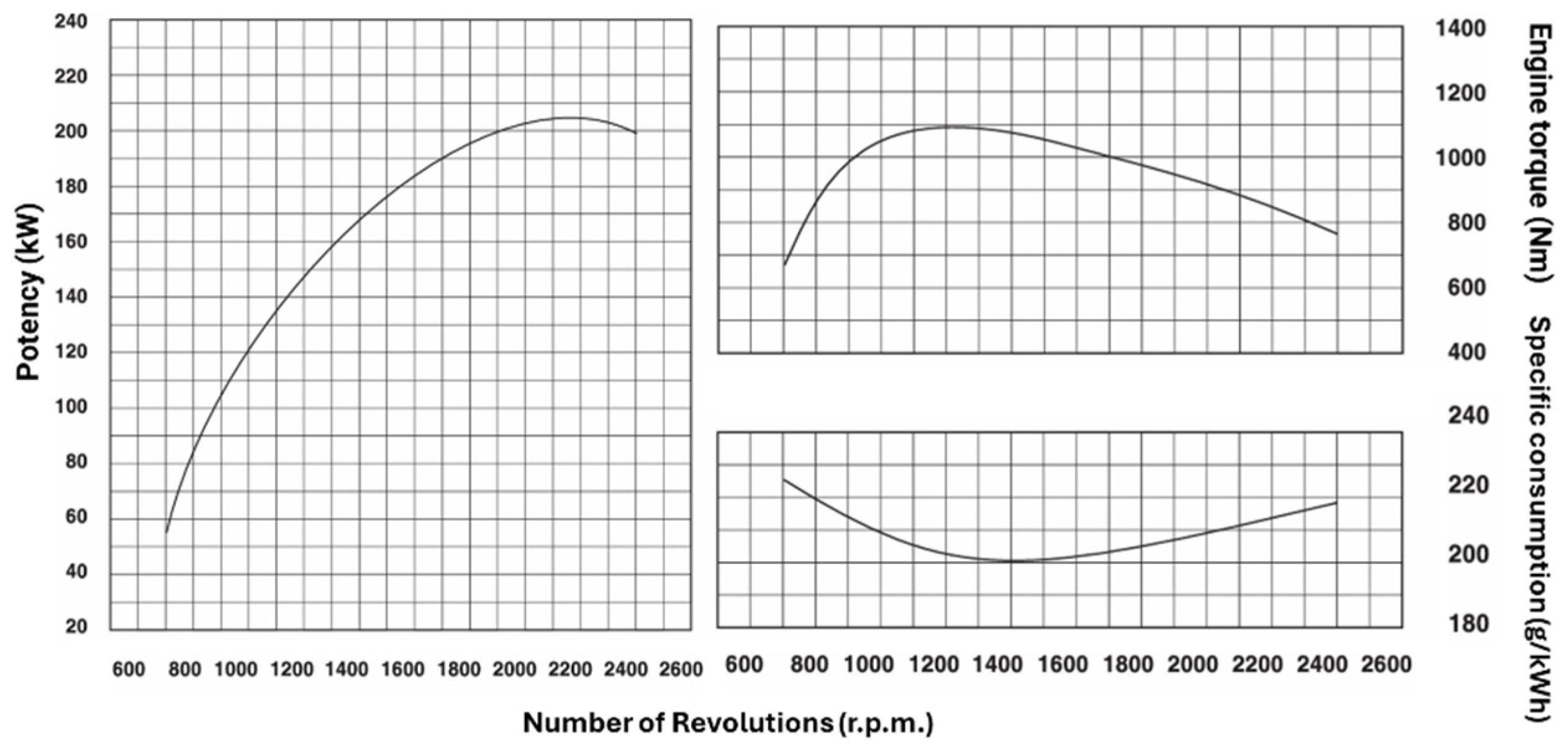

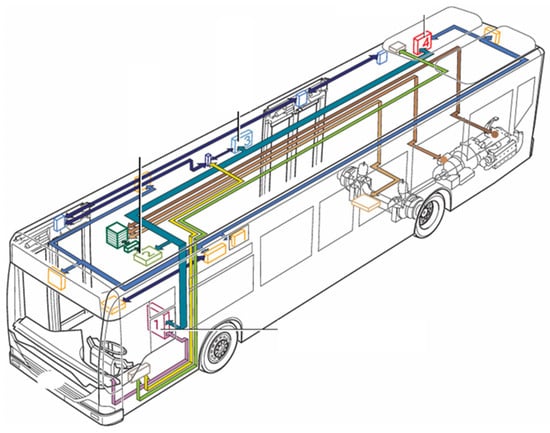

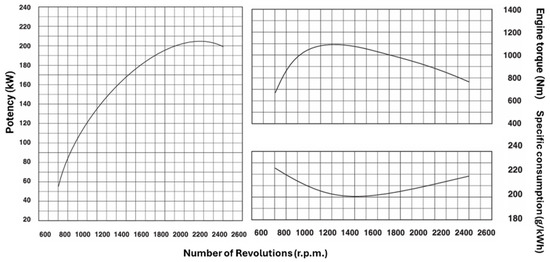

In this chapter we present a case study of an urban passenger transport company in Coimbra, using several research techniques, as well as a discussion of the results obtained. Below, we present the characteristics of the case study vehicle (Figure 3 and Figure 4):

Figure 3.

Vehicle structure (source: manufacturer’s manual).

Figure 4.

Engine power, torque and consumption diagrams (source: manufacturer’s manual).

Fleet number no. 003268

Year: 2004

Brand: A

Model: X

Registration: 72-12-UN

Chassis number: VS96280432A172050

Gross weight: 19,000 kg

Fuel: Diesel

Cylinder capacity: 6373 cm3

Number of cylinders: 6

Compression ratio: 17.4:1

Nominal speed: 2300 rpm

Engine power: 205/280 kW/hp

Maximum torque: 1100 Nm

Lubrication: Lubrication by forced circulation

Oil filter: Long-lasting oil filter, vertical arrangement

Capacity: 33 Sitting + 62 Standing + Mot

Capacity total: 95 passengers

The company uses preventive and corrective maintenance strategies. Table 1 shows the regular maintenance intervals for the vehicle that suffered the fire.

Table 1.

Periodic preventive maintenance interval—bus.

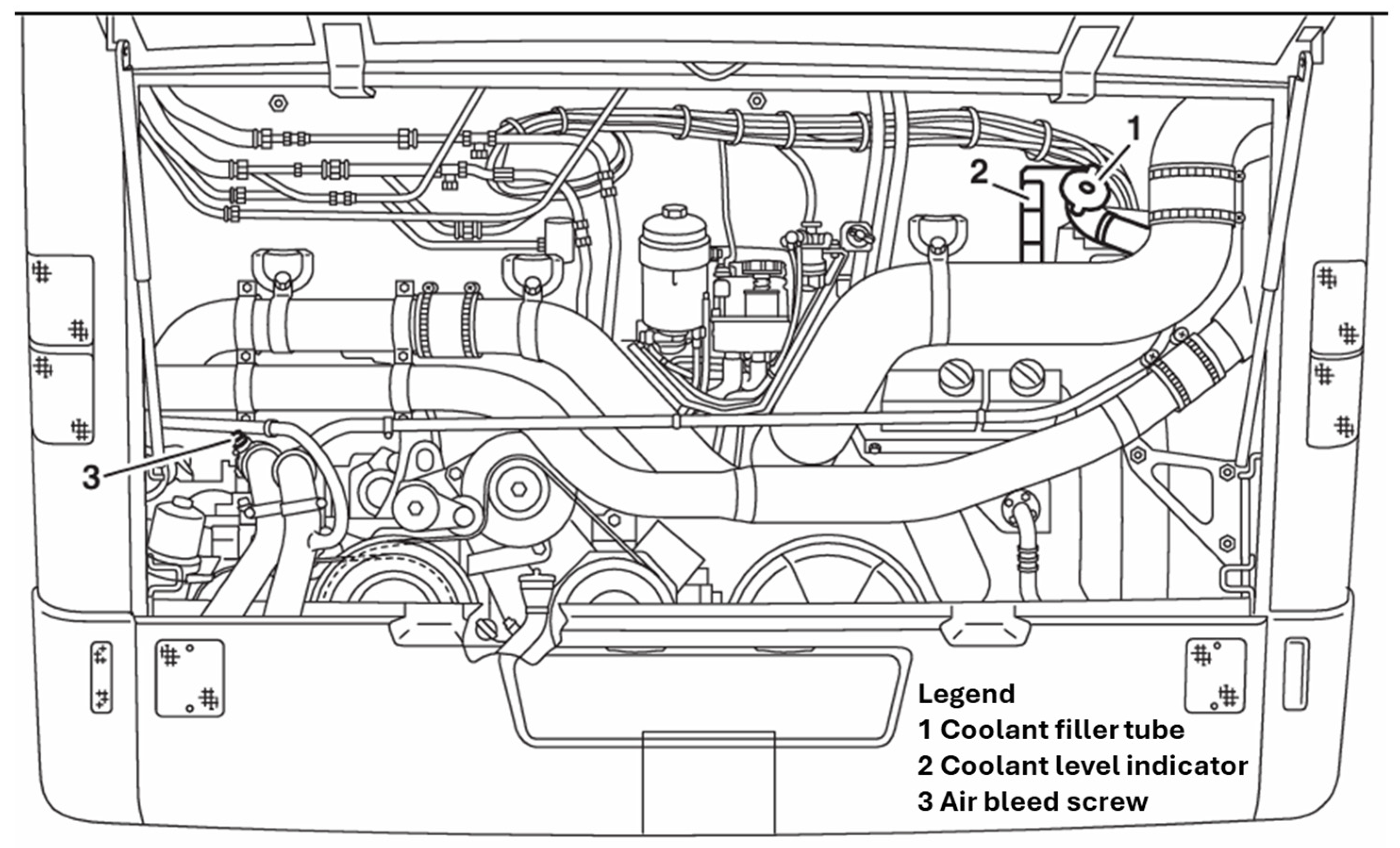

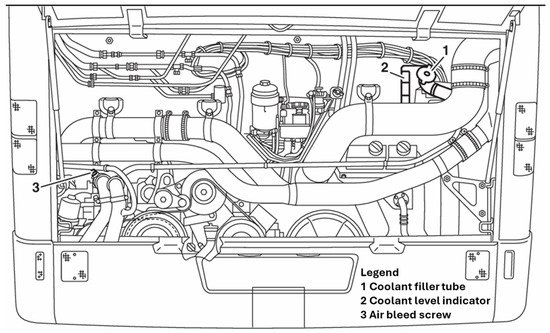

On the basis of the driver’s testimony and the observation made by the investigation team, we are inclined to believe at this stage that the fire was caused by the bursting of a flexible hydraulic engine oil supply pipe that drives the front cooling fan for the intercooler air exchangers, the engine cooling water and also the hydraulic system oil (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Engine compartment and oil system (source: manufacturer’s manual).

The bursting of this hose is consistent with the popping noise heard by the driver, given the high pressure at which the oil circulates in these pipes. It is also consistent with the driver’s testimony that the oil came out “in gulps”, fuelling the combustion of the liquid that was spilt on the ground at the rear of the vehicle. According to the bus manufacturer, the maximum working pressure of the oil in the hydraulic circuit that incorporates these pipes is 210 bar. The pressure and flow rate in these pipes depends on the speed at which the hydraulic fan motor works. The speed of the fan is adjusted according to the atmospheric conditions in which the bus operates so that the temperature of the engine coolant at the outlet of its radiator is in the 83–89 °C range and the temperature of the charge air coming from the engine’s turbocharger at the outlet of the intercooler is in the 45–65 °C range. The maximum working speed of the fan is 2100 rev/min. According to the bus manufacturer, the capacity of the hydraulic circuit that drives the fan is 11 litres of oil.

This hypothesis is also compatible with the area of the vehicle where the driver said he saw some white smoke and, a little later, the first flames.

This hypothesis is also put forward to the exclusion of other possibilities that would be compatible with the facts and evidence we have been able to ascertain.

The process by which the oil in the hydraulic system ignited remains to be explained, since, although it circulates at a high pressure and temperature in the circuit, its exposure to the environment—even a relatively heated one—in the engine compartment is not likely to cause a self-ignite, i.e., to start burning without the help of other agents, such as a heat source or an electric spark.

3.1. Failure Analysis

The analysis developed in this study was based on the history of incidental failures recorded in the vehicle. The main objective was to identify, understand, and characterize the failure modes that impact the performance and availability of this equipment and lead to this type of accident.

In this context, the process began with the development of an FMECA (Failure Modes, Effects, and Criticality Analysis) analysis, with the main objective of analyzing possible failures and their causes. To achieve this, the analysis and study of the history of this type of vehicle were initiated, as well as consultations with the most experienced technicians to construct Table 2 of the FMECA analysis.

Table 2.

FMECA analysis—bus fire.

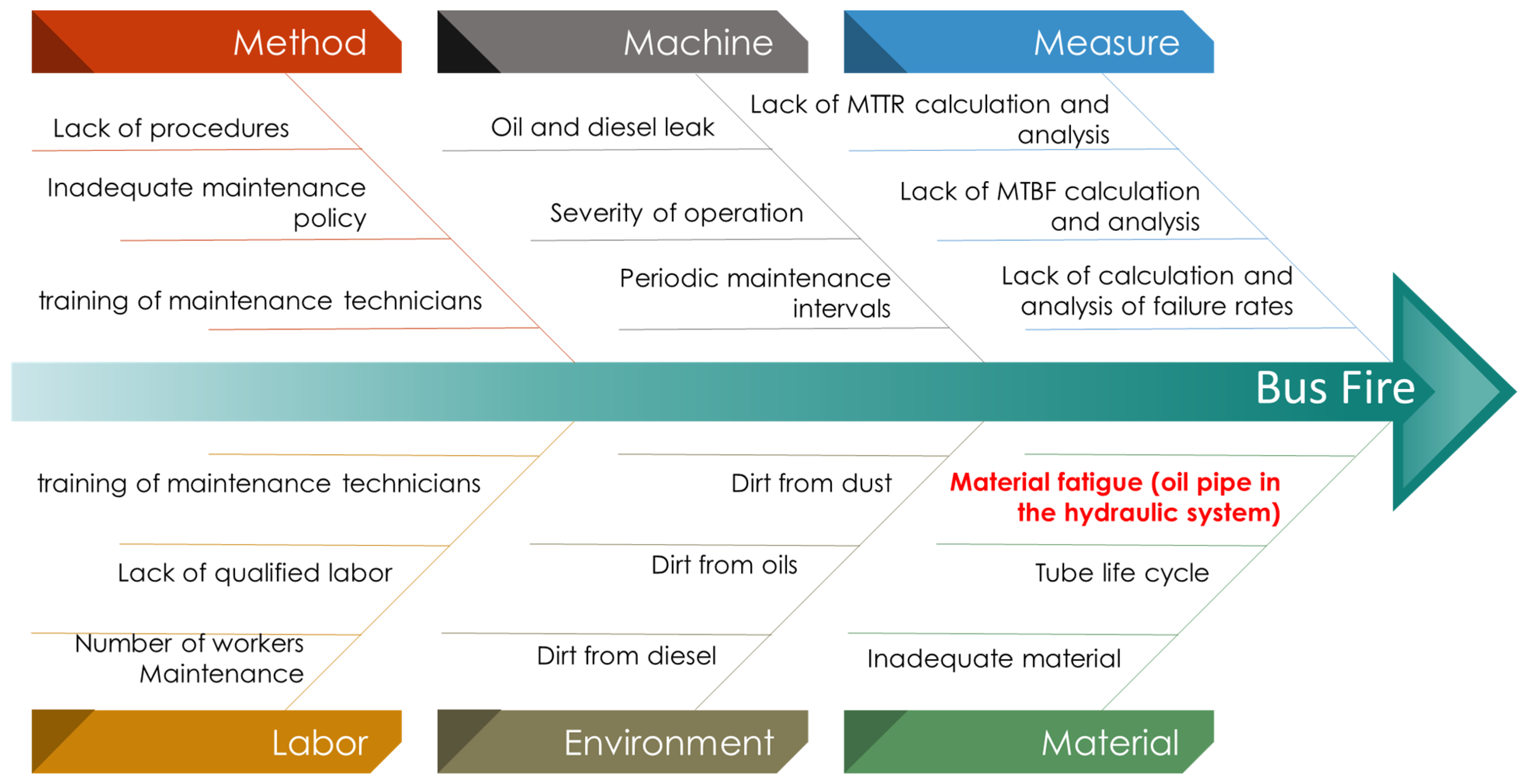

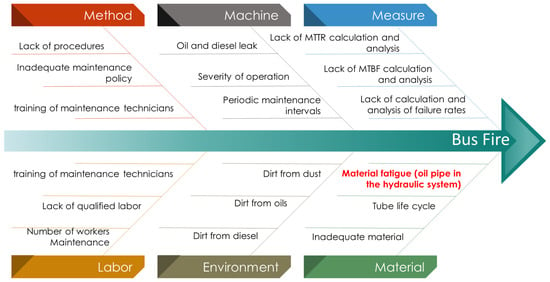

After identifying the failure modes related to the bus fire, the failure mode “rupture of an oil pipe in the hydraulic system” stood out. This identification involved the creation of an Ishikawa diagram, also known as a fishbone diagram.

This method allows for the structured organization of the factors that may be causing the failure, grouping them into categories such as method, labour, machine, maintenance, measurement, and materials. The goal is to identify the possible causes contributing to this failure mode.

The diagram resulting from this analysis (Figure 6) clearly shows the possible root causes associated with the failure mode, serving as support for defining more effective corrective, preventive, and on-condition preventive actions.

Figure 6.

Failure Modes—Ishikawa Diagram.

After identifying the cause of the failure using the Ishikawa diagram, namely a ruptured hydraulic system oil pipe, we studied the hydraulic system oil ignition next.

3.2. Ignition of Hydraulic System Oil

Aiming to determine the physical properties of the hydraulic system oil used in this type of vehicle, namely its flammability characteristics, samples of new and used oil with the reference Brand XX, XHP 10W40, supplied by the transport company, were analyzed.

The characteristics and operating conditions of the lubricants used (Supplier/Brand) are summarized below:

- Multigrade synthetic lubricant of exceptional quality, of the EHPDO (Extra High Performance Diesel Oil) type, especially recommended for the lubrication of high-powered, naturally aspirated or turbocharged heavy-duty vehicle Diesel engines, operating in the most severe conditions of use, namely when subjected to very wide oil change intervals, possessing the properties shown in Table 3.

Table 3. Main characteristics of the oil (lubricant).

Table 3. Main characteristics of the oil (lubricant).

3.3. Analysis and Test Oil (Lubricant)

Viegas et al. [28] presented a study on a metal disc made of 6082-T6 Aluminum alloy, with a diameter of 180.0 mm and a thickness of 45.0 mm. It was instrumented with a K-type thermocouple with a 1.5 mm diameter stainless steel sheath, which was inserted into a 1.5 mm diameter and 11 mm deep hole in the disc to measure the disc’s temperature. The disc was heated evenly and drops of oil were dropped on the disc, according to Table 4, and their evolution was recorded.

Table 4.

Hot metal disc analysis results.

Tests were carried out in which two or three drops of oil were dropped on the disc with the disc at a temperature of 275 ± 2 °C and using new oil and used oil, and in both tests, the oil did not ignite thermally within a time interval of 10 min.

Next, a test was carried out in which two to three drops of used oil were dropped on the disc with the disc at a temperature of 380 ± 2 °C, and the oil did not ignite thermally within a time interval of 10 min.

A test was then carried out in which two to three drops of new oil were dropped on the disc at a temperature of 390 ± 2 °C, and the oil did not ignite thermally within 10 min (Table 4).

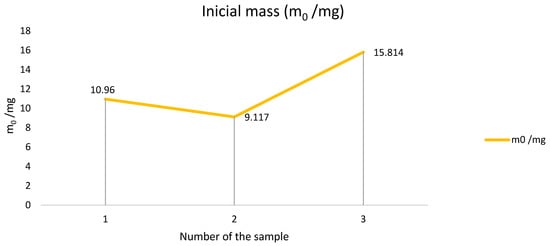

Simultaneous Thermogravimetric Analysis and Differential Thermal Analysis tests were also carried out on samples of new and used oil. These analyses were carried out on a Rheometrics Scientific Simultaneous Thermal Analyser 1500 (STA-1500) (TA Instruments, New Castle, DE, USA).

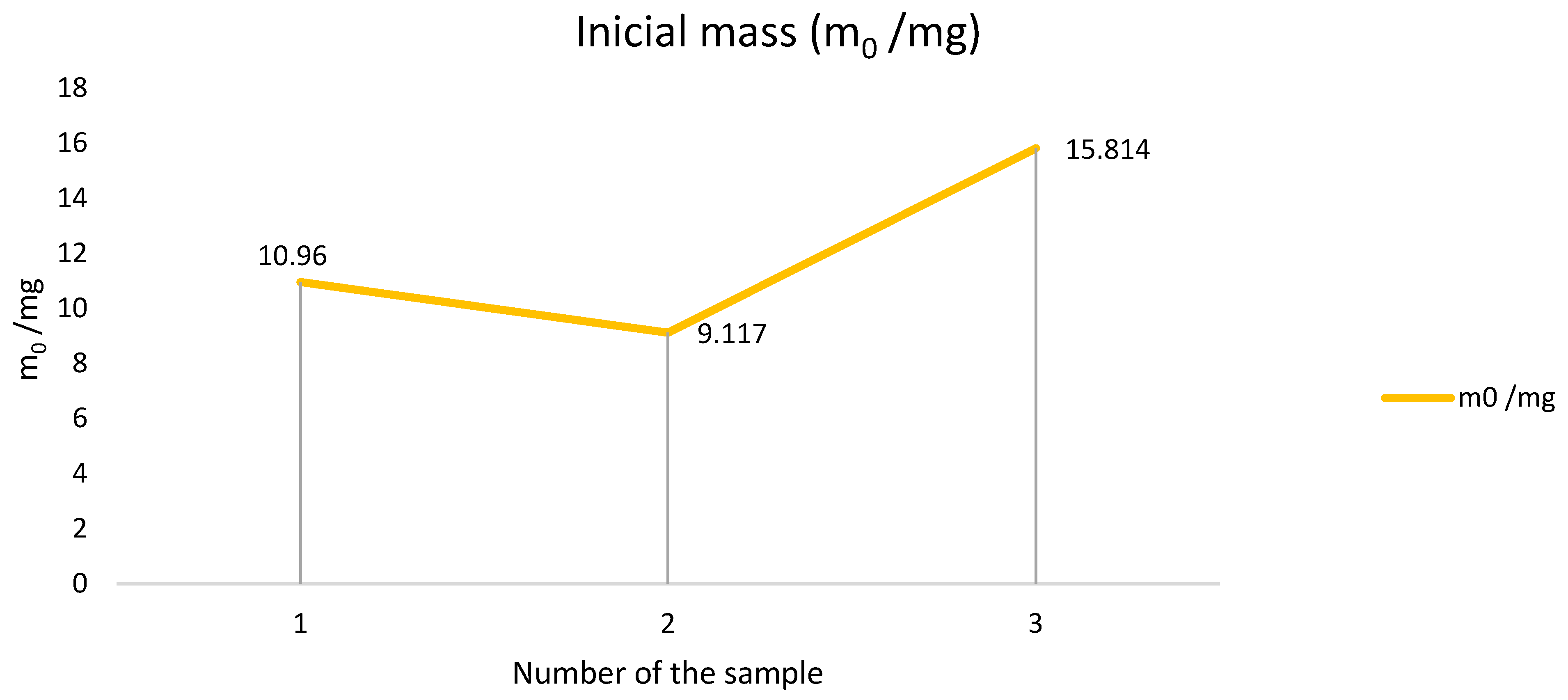

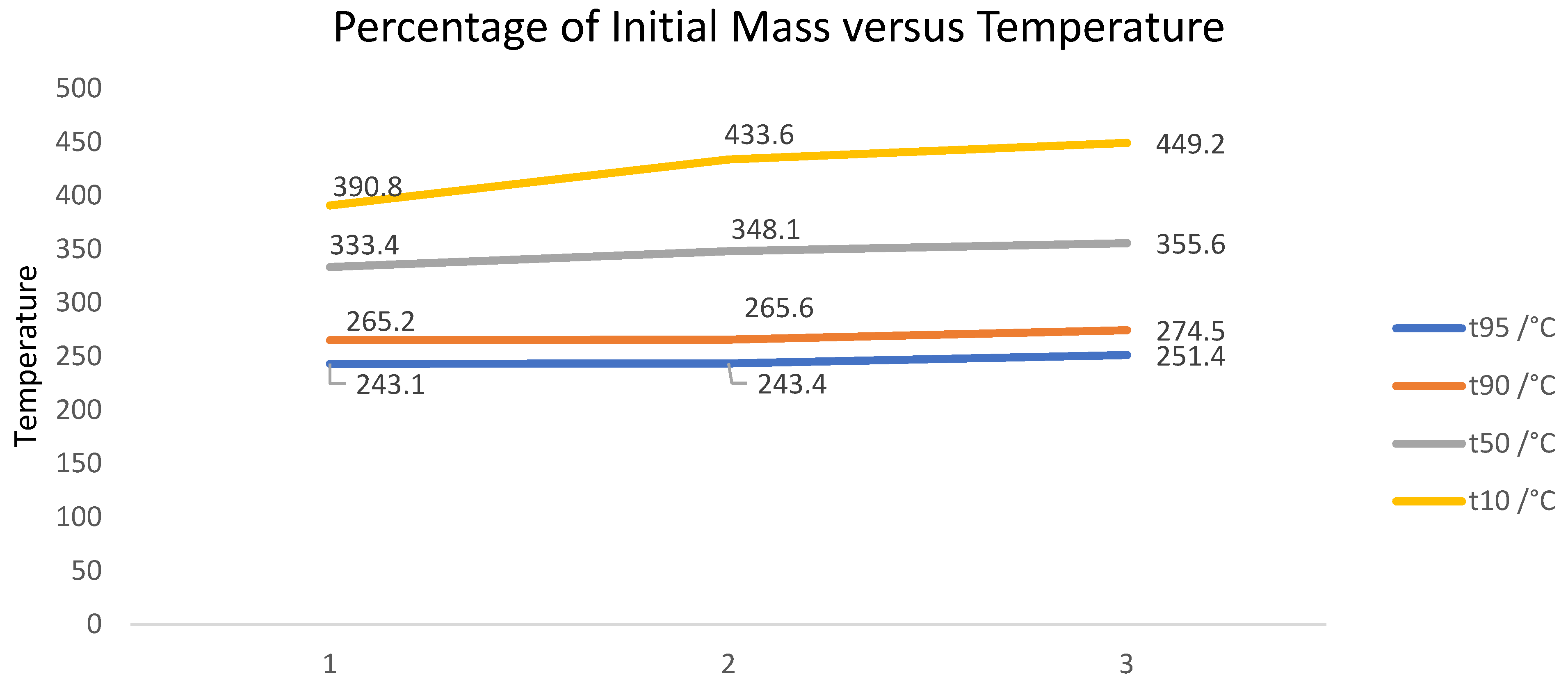

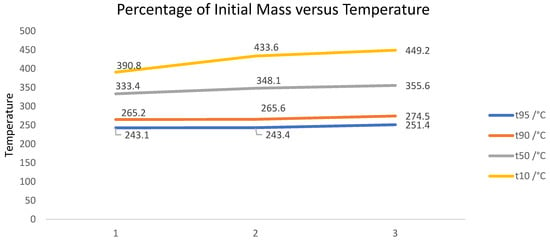

The results of these tests are summarized in Table 5, which shows the initial mass of each sample and whether it was new or used oil (Figure 7 and Figure 8). The tests began at room temperature, which, depending on the test, was between 20 °C and 31 °C, and all ended at 1200 °C. These tests were carried out at a heating rate of 10 °C/min in a synthetic air atmosphere consisting of 20% by volume of O2 (oxygen) and 80% by volume of N2 (nitrogen), which closely represents an air atmosphere. These tests show the temperatures at which the samples have 95%, 90%, 50% and 10% of their initial mass, which gives a good idea of the temperature range at which the combustion reaction of the oil samples with the air takes place [28].

Table 5.

Results of the simultaneous TG/DTA analysis of the new and used oil samples.

Figure 7.

Mass of each sample in m0/mg.

Figure 8.

Temperature as function of mass of each sample in m0/mg.

The surface temperature of the pipe between the turbocharger and the intercooler has not yet been measured experimentally, but it should be lower than 250 °C as a result of calculations carried out, and also due to the fact that the materials that can withstand higher temperatures used in the manufacture of the hoses that connect the metal pipe after the turbocharger with the metal pipe before the intercooler can only withstand a maximum continuous working temperature of 250 °C [29]. TG/DTA tests indicate that the thermal ignition temperature of Brand XX, XHP oil should be above 300 °C. A published study [30] indicates that the thermal ignition temperature depends on the apparatus used to measure it. Colwell & Reza [30] carried out a study in which they measured the thermal ignition temperature of a gas turbine lubricating oil that complies with MIL-L-7808, using various methods. The lubricating oil considered was Royco 808. This lubricating oil has an ignition temperature (Flash Point) of 232 °C. Using the procedure described in the ASTM E659-78(2000) standard [31], which creates an isothermal environment for the ignition of a drop of liquid and therefore makes it possible to obtain the lowest thermal ignition temperature, these researchers obtained a thermal ignition temperature of 365 °C. Using an experimental set-up similar to the one we used, in which a drop of liquid was dropped onto an electrically heated AISI 304 stainless steel test surface, with dimensions 48 cm × 38 cm × 4.8 cm (L × W × H), which obtained thermal ignition temperatures in the range of 535–635 °C. Strasser et al. [32] measured the thermal ignition temperature of a gas turbine lubricating oil complying with the MIL-L-7808 standard on the surface of a steel tube with an outside diameter of 101.6 mm (4”) and a length of 304.8 mm (12”) in an air atmosphere at 27 °C (80 °F) with zero air flow velocity over the surface and obtained a thermal ignition temperature of 543 °C (1010 °F). They also carried out tests to measure the thermal ignition temperature of the same lubricating oil for the air flow velocity over the surface of the tube parallel to the tube axis in the range 0.30 m/s to 2.6 m/s (1 to 8.5 ft/s) and found that the thermal ignition temperature of the oil increases monotonously with the flow velocity and is equal to 649 °C (1200 °F) for a flow velocity over the surface of 2.6 m/s (8.5 ft/s).

These researchers also carried out tests to measure the thermal ignition temperature of the same oil on the surface of a 4” (101.6 mm) outer diameter steel pipe in an air atmosphere at 177 °C (350 °F) for the flow velocity over the pipe surface parallel to the pipe axis in the range 1.1 to 8, 5 ft/s and found that the thermal ignition temperature of the oil increases monotonously with the flow velocity, being equal to 516 °C (960 °F) for a flow velocity over the surface of 0.34 m/s (1.1 ft/s) and being equal to 610 °C (1130 °F) for a flow velocity over the surface of 2.6 m/s (8.5 ft/s).

The results of the tests carried out by Colwell & Reza (2005) [30] and Strasser et al. (1971) [32] with lubricating oils that comply with the MIL-L-7808 standard lead to the following conclusions:

- The thermal ignition temperature obtained by the ASTM E659 standard [31] (365 °C) is considerably lower than that obtained by tests on an electrically heated flat surface (535–635 °C);

- The minimum thermal ignition temperature, measured by tests on a flat surface of AISI 304 stainless steel at zero flow velocity, 535 °C, is similar to that measured in tests on the surface of a steel pipe with an outside diameter of 4” (101.6 mm) at zero flow velocity, 543 °C;

- The thermal ignition temperature measured by tests on the surface of a steel pipe with an outside diameter of 4” (101.6 mm) with a non-zero air flow velocity parallel to the pipe axis increases with the air flow velocity;

- The thermal ignition temperature measured by tests on the surface of a steel pipe with an outside diameter of 4” (101.6 mm) with zero or non-zero air flow velocity parallel to the tube axis decreases with increasing the temperature of the air atmosphere surrounding the tube. For zero air flow velocity, the thermal ignition temperature decreased from 543 °C (1010 °F) for an air temperature of 27 °C (80 °F) to an estimated thermal ignition temperature of 499 °C (930 °F) for an air temperature of 177 °C (350 °F). For an air flow velocity parallel to the tube axis of 2.6 m/s (8.5 ft/s), there was a decrease in the thermal ignition temperature from 649 °C (1200 °F) for an air temperature of 27 °C (80 °F) to a thermal ignition temperature of 610 °C (1130 °F) for an air temperature of 177 °C (350 °F).

By comparing the results obtained by Colwell & Reza [30] and Strasser et al. [32] with the results obtained in the experimental measurements we carried out with Brand XX, XHP 10W40 oil and the data we have, the following was concluded:

- The self-ignition temperature (Flash Point) of Brand XX, XHP 10W40 oil is 197 °C;

- The Royco 808 oil, which complies with the MIL-L-7808 standard tested by Colwell & Reza [30], has a Flash Point temperature of 232 °C, a thermal ignition temperature obtained from the ASTM E659 standard [31] of 365 °C and a minimum thermal ignition temperature on a heated flat plate of 535 °C.

Assuming that the observed difference in self-ignition temperature between Royco 808 oil and Brand XX, XHP 10W40 oil Δt = 232 °C − 197 °C = 35 °C is maintained for the thermal ignition temperature obtained by the ASTM E659 standard and for the minimum thermal ignition temperature on a heated flat plate, the thermal ignition temperature obtained by the ASTM E659 standard estimated for Brand XX, XHP 10W40 oil is 330 °C and the minimum thermal ignition temperature on a heated flat plate estimated for Brand XX, XHP 10W40 oil is 500 °C. The ASTM E659 thermal ignition temperature estimated for Brand XX, XHP 10W40 oil, 330 °C, correlates well with the temperature at which the new oil sample shows 50% of its initial mass for the Thermogravimetric Analysis and Simultaneous Differential Thermal Analysis we carried out, 333.4 °C [28].

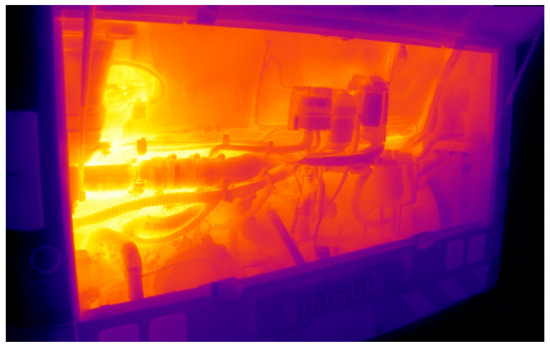

3.4. Analysis of Engine Compartment Temperatures

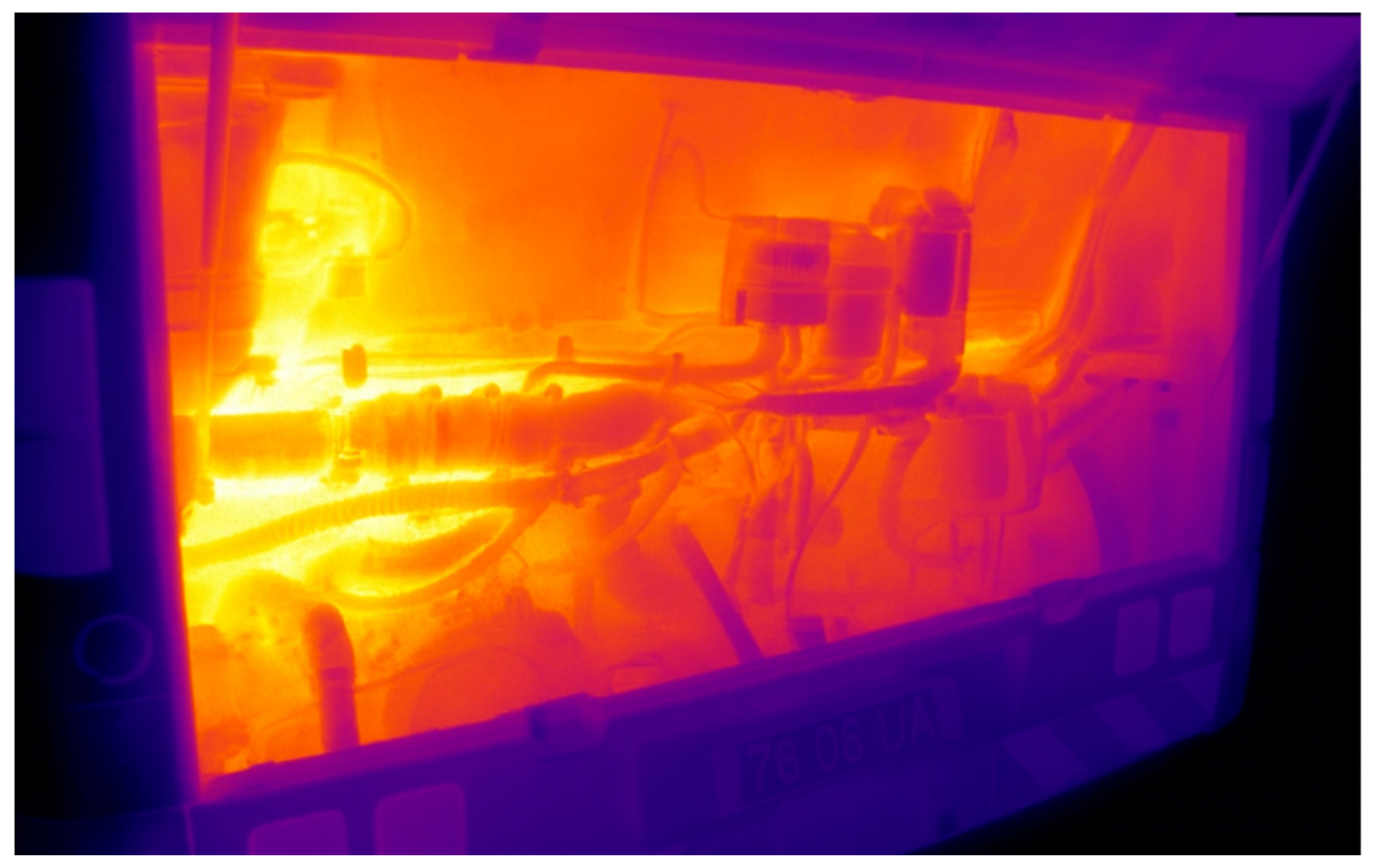

Temperature measurement tests were also carried out in the engine compartment of an identical vehicle, using an infrared camera, namely: FLIR SC660 IR Camera, which allows analysis of equipment temperature profiles, enabling fault detection.

The FLIR SC660 (Figure 9) has a high-resolution 640 × 480 pixel detector for greater accuracy and higher resolution. It has an integrated 3.2-megapixel visual camera to generate sharp visual images in all conditions.

Figure 9.

FLIR SC660 IR camera.

The camera technical characteristics are the following:

| Brand | FLIR Systems |

| Manufacturer | FLIR Systems |

| Category | CCTV > CCTV cameras |

| Model code | SC660 |

| Resolution TVL | 640 × 480 |

| Digital (DSP) | Yes |

| Specialist Types | Thermal |

| Electrical Specifications | Voltage: 12 VDC |

| Signal Mode | PAL, NTSC |

| Zoom | Yes |

| Physical Specifications Dimension mm: | 299 × 144 × 147 |

| Weight g: | 1800 |

| Environmental Specifications | Operating Temperature °C: −15~+50 |

| Operating Humidity %: | 0~95 |

Several tests were carried out with the vehicle’s engine running, reproducing and simulating the actual operating conditions of the engine at the time of the accident. We found that the surfaces in the engine compartment with temperatures above the ignition value (value ≥ 500 °C) are the exhaust collector, the exhaust pipe next to the exhaust manifold (exhaust collector) and the turbocharger turbine body. The components that, due to their position, are most likely to be hit by oil droplets from the burst hydraulic pipe are the exhaust manifold and the exhaust pipe next to the exhaust manifold, as shown in Figure 10.

Figure 10.

Thermal image of the engine compartment.

Based on the data, it can be stated that the reasoning presented and assuming that the fire originated from the bursting of the flexible hydraulic oil pipe that feeds the hydraulic motor that drives the front cooling fan of the engine radiator and the engine intercooler can be concluded that the fire may have originated from the following:

- Thermal ignition of the oil coming from the bursting of the hydraulic oil pipe feeding the hydraulic fan drive motor, in contact with a surface with a temperature of over 500 °C. The surfaces in the engine compartment with a temperature above this value are the exhaust manifold, the exhaust pipe next to the exhaust manifold and the turbine housing of the turbocharger. The components that, due to their position, are most likely to be hit by oil spills from the burst hydraulic pipe are the exhaust manifold and the exhaust pipe next to the exhaust manifold. The fire then must have spread into the engine compartment via the oil that soaked these and the other components in the engine compartment, and to the ground via the oil that fell to the ground from these components in the engine compartment. Another phenomenon that may have contributed to the spread of the fire are the flammable vapours released from the oil coming from the burst hydraulic hose when it came into contact with surfaces at a temperature higher than the Flash Point of the oil, 197 °C, such as the aforementioned components with a temperature higher than 500 °C, the compressor housing on the turbocharger, most likely the metal tube between the turbocharger and the intercooler (its surface temperature will still have to be measured to be sure of this), the exhaust manifold, and the compressor filter housing of the bus’s pneumatic system.

- Ignition by sparks produced in the engine compartment of flammable vapours released from the oil coming from the burst hydraulic pipe by its contact with surfaces at a temperature higher than the Flash Point of the oil, 197 °C, as is the case with the aforementioned components with a temperature higher than 500 °C, the compressor housing in the turbocharger, most likely the metal tube between the turbocharger and the intercooler, the exhaust manifold and the compressor filter of the bus’s pneumatic system. So far, no source of sparks in the engine compartment has been unequivocally identified. An example of a component that could have started a fire would be the alternator, but this was not the cause of this fire. The alternator was tested and dismantled to analyze its condition; it was not detected as an anomaly, or as a cause that could lead to a faulty ignition that could cause a road fire (bus). Although less likely, two other scenarios that could have caused the fire cannot be ruled out:

- There was a fracture in the engine block, in the compressor block of the bus’s pneumatic system, or in the turbocharger that caused a leak of engine oil that has caused thermal ignition in contact with components already listed in the engine compartment with a surface temperature of over 500 °C. Screening for this hypothesis involves dismantling the bus engine and carefully inspecting it to see if it has any fractures in the engine block, the compressor block of the bus’s pneumatic system or the turbocharger that has caused an engine oil leak.

- An electrical short circuit in the engine compartment.

3.5. Experience of Other Operators

At the meeting with representatives of Carris Bus and STCP, we learned that these two operators use Brand A, Model X vehicles of various versions and years of manufacturing. Carris has a fleet of 39 Brand A, Model X vehicles from 2000, which are leased to mm, which uses them to transport passengers within Lisbon’s Portela Airport. STCP has 75 Brand A, Model X vehicles.

It was mentioned that the evolution of European standards for this type of vehicle (Euro 2, Euro 3 and Euro 4 codes) has made ever-greater demands on propulsion systems. These measures mean that propulsion systems are made up of additional systems designed to increase their energy efficiency and reduce emissions of polluting gases, which increases their complexity and reduces the space available to carry out the heat exchanges that some processes require.

At Carris, a fire broke out in a Brand A, Model X vehicle. STCP has reported accidents, not all of them involving vehicles of this model.

The main causes of the reported fire accidents were broken engine components, such as the connecting rod, and the poor state of electrical wiring, which was losing its insulation.

During the preparation of this report, we learned of an accident caused by a fire in a Brand A, Model X vehicle in Germany, which resulted in the vehicle being destroyed.

4. Conclusions

This paper suggests that the cause of the fire in the transport vehicle studied was the bursting of an oil pipe in the hydraulic system of the cooling fans of the vehicle’s heat exchangers and offer the following consideration: this is a cause of fire that has not occurred in previous cases of accidents involving vehicles of the same model. Manufacturing defect in oil pipe, non-compliance of the part used with the manufacturer’s recommendations, defects in the threaded joints connecting the pipes to the hydraulic motor, the formation of cracks in the pipe due to material fatigue caused by the system’s pressurization and depressurization cycles and the condition of these pipes must be checked during routine inspections to ensure that they do not show any of the signs mentioned in the previous point.

Therefore, we suggest replacing these pipes after certain periods of use, in accordance with the manufacturer’s recommendations, or more demanding ones if the risk of this type of accident warrants it. It should be noted that the use of these vehicles in the high temperatures experienced in Portugal—compared to the countries of origin of these vehicles—may force to reduce preventive maintenance periods or even the replacement of critical components.

In conclusion, a Condition Based Maintenance policy is recommended for this type of fleet, using various condition maintenance techniques, namely visual inspections, oil analysis, thermography and vibration analysis. We also recommend that the company change the periodic systematic maintenance intervals, notably reducing the intervals from 50,000 km to 25,000 km; it is recommended to replace the oil pipe during inspection after 100,000 km.

Additionally, from the study presented, we suggest the following to the vehicle manufacturer: include fire detection and suppression systems in the engine bay; improve compartmentalization to prevent flame propagation; implement better routing of electrical and hydraulic lines; introduce enhanced materials with higher fire resistance. These conclusions align with trends in newer buses, as is referred in the paper.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.R. and J.R.; methodology, H.R. and J.R.; formal analysis, H.R. and J.R.; investigation, H.R. and J.R.; resources, H.R. and J.R.; writing—original draft preparation, H.R. and J.R.; writing—review and editing, J.T.F., H.R., J.R. and J.E.d.-A.-e.-P.; project administration, J.R. and H.R.; funding acquisition, J.T.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This article was supported by RCM2+ Research Centre in Asset Management and System Engineering. The authors acknowledge the Forest Fire Research Laboratory (LEIF) of the Forest Fire Research Center (CEIF) of ADAI, University of Coimbra (UC), for their support required for the development of the tests.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- EN 13306:2021; Maintenance—Maintenance Terminology. European Standard: Brussels, Belgium, 2021.

- Farinha, J.T. Asset Maintenance Engineering Methodologies, 1st ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macián, V.; Tormos, B.; Gomez Estrada, Y.A.; Bermúdez, V. Revisión del proceso de la degradación en los aceites lubricantes en motores de gas natural comprimido y diesel. Dyna Ing. Ind. 2013, 88, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macian, V.; Tormos, B.; Ruiz, S.; Ramirez Roa, L.; Diego, J. In-Use Comparison Test to Evaluate the Effect of Low Viscosity Oils on Fuel Consumption of Diesel and CNG Public Buses. In Proceedings of the SAE 2014 International Powertrain, Fuels & Lubricants Meeting, Birmingham, UK, 20–23 October 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macián, V.; Tormos, B.; Ruiz, S.; Ramirez, L. Potential of low viscosity oils to reduce CO2 emissions and fuel consumption of urban buses fleets. Transp. Res. Part D 2015, 39, 76–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macián, V.; Tormos, B.; Miró, G.; Pérez, T. Assessment of low-viscosity oil performance and degradation in a heavy-duty engine real-world fleet test. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part J J. Eng. Tribol. 2016, 230, 729–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raposo, H.D.N.; Farinha, J.T.; Oliveira, R.; Ferreira, L.A.; André, J. Time Replacement Optimization Models for Urban Transportation Buses with Indexation to Fleet Reserve. In Proceedings of the MPMM—Maintenance Performance Measurement and Management 2014, Coimbra, Portugal, 4–5 September 2014; pp. 41–48. [Google Scholar]

- Raposo, H.; Farinha, J.T.; Ferreira, L.; Galar, D. An integrated econometric model for bus replacement and determination of reserve fleet size based on predictive maintenance. Maint. Reliab. 2017, 19, 358–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raposo, H.; Farinha, J.T.; Ferreira, L.; Didelet, F. Economic life cycle of the bus fleet: A case study. Int. J. Heavy Veh. Syst. 2018, 24, 31–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raposo, H.; Farinha, J.T.; Fonseca, I.; Ferreira, L.F. Predictive Maintenance Based on Condition of Oil Engines in Urban Buses—A Case Study. Actuators 2019, 8, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raposo, H.; Farinha, J.T.; Fonseca, I.; Galar, D. Predicting condition based on oil analysis—A case study. Tribol. Int. 2019, 135, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syed, S. Enhancing School Bus Engine Performance: Predictive Maintenance and Analytics for Sustainable Fleet Operations. Libr. Prog.-Libr. Sci. Inf. Technol. Comput. 2024, 44, 17765–17775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macián, V.; Tormos, B.; Herrero, J. Maintenance management balanced scorecard approach for urban transport fleets. Maint. Reliab. 2019, 21, 226–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folęga, P.; Burchart, D.; Kubik, A.; Turoń, K. Application of the life cycle assessment method in public bus transport. Maint. Reliab. 2025, 27, 204539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundström, B.; Rosen, F. Bus Fire Safety Research for Reducing the Risk of Fires. RISE Research Institutes of Sweden, Division Transport and Safety. Newsletter n.13. 2017. Available online: https://polymerandfire.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/polyflame-n13.pdf (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Feng, S.; Li, Z.; Sun, X. Analysis of bus fires using interpretative structural modeling. J. Public Transp. 2016, 19, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Office of Transport Safety Investigations. Bus Fire, Sydney Harbour Bridge, Milsons Point. Bus Safety Investigation Report. Office of Transport Safety Investigations. 2017. Available online: https://www.otsi.nsw.gov.au/sites/default/files/2022-06/bus_safety_report_bus_fires_nsw_2017.pdf (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Meltzer, N.R.; Ayres, G.; Truong, M.; John, A. Motorcoach Fire Safety Analysis: The Causes, Frequency, and Severity of Motorcoach Fires in the United States. 2012. Available online: https://rosap.ntl.bts.gov/view/dot/9670 (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Meltzer, N.; Beaven, L.; Canas, N.; Istfan, N.; Phillips, B.; John, A. Motorcoach and School Bus Fire Safety Analysis (No. FMCSA-RRR-16-016; DOT-VNTSC-FMCSA-16-02). United States. Department of Transportation. Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration. Office of Analysis, Research, and Technology. 2016. Available online: https://rosap.ntl.bts.gov/view/dot/12392 (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Hammarström, R.; Axelsson, J.; Försth, M.; Johansson, P.; Sundström, B. Bus Fire Safety; SP Report; SP Technical Research Institute of Sweden: Borås, Sweden, 2008; Volume 41, Available online: https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:962472/FULLTEXT01.pdf (accessed on 2 January 2026).

- Smyth, S.; Dillon, S. Common Causes of Bus Fires. In Proceedings of the SAE 2012 World Congress & Exhibition, Detroit, MI, USA, 24–26 April 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, A.T. Maintenance performance evaluation of bus fleet garages using a hybrid approach. Int. J. Ind. Syst. Eng. 2022, 41, 472–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredrik, R.M.H.; Erlandsson, U.; Sjöberg, F. Buses as Fire Hazards: A Swedish Problem Only? Suggestions for Fire-Prevention Measures. J. Burn. Care Rehabil. 2004, 25, 377–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodges, S. Effective Fire Protection Systems for Vehicles. In Proceedings of the SAE 2006 World Congress & Exhibition, Detroit, MI, USA, 3–6 April 2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohilla, M.; Saxena, A.; Tyagi, Y.K. Condensed Aerosol Based Fire Extinguishing System Covering Versatile Applications: A Review. Fire Technol. 2022, 58, 327–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Ou, Z.; Xue, Y.; Wang, C.; Wu, H. Design of OFDM-based two-wire bus communication system for fire safety. Int. J. Commun. Syst. 2024, 37, e5811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macián, V.; Tormos, B.; Bastidas, S.; Pérez, T. Improved fleet operation and maintenance through the use of low viscosity engine oils: Fuel economy and oil performance. Maint. Reliab. 2020, 22, 201–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viegas, D.X.; Figueiredo, A.R.; Góis, J.C.; Mendes, R.; Carvalheira, P.; Raposo, J. Relatório Preliminar da Investigação: Análise do Acidente Ocorrido com uma Viatura Mercedes Benz Citaro dos SMTUC; ADAI-LAETA, DEMUC, Universidade de Coimbra: Coimbra, Portugal, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Samco Sport Hoses. Available online: https://samcosport.com/race-parts/straight-coupling-hose/ (accessed on 7 August 2023).

- Colwell, J.D.; Reza, A. Hot Surface Ignition of Automotive and Aviation Fuels. Fire Technol. 2005, 41, 105–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM E659-78(2000); Standard Test Method for Autoignition Temperature of Liquid Chemicals. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2000.

- Strasser, A.; Waters, N.C.; Kuchta, J.M. Ignition of Aircraft Fluids by Hot Surfaces Under Dynamic Conditions, Bureau of Mines PMSRC; Report no. 4162, Technical Report AFAPL-TR-71-86; Air Force Aero Propulsion Laboratory, Air Force Systems Command, Wright-Patterson Air Force Base: Fairborn, OH, USA, 1971. Available online: https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/219340 (accessed on 2 January 2026).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.