Abstract

Collisions with fallen pedestrians pose a lethal challenge to current advanced driver-assistance systems. This paper introduces and quantitatively validates the Advanced Falling Object Detection System (AFODS), a novel safety framework designed to mitigate this risk. AFODS architecturally integrates long-wave infrared, near-infrared stereo and ultrasonic sensors, processed through a novel artificial intelligence pipeline that combines YOLOv7-Tiny for object detection with a recurrent neural network for proactive threat assessment, thereby enabling the system to predict falls before they are complete. In a rigorous controlled study using simulated adverse conditions, AFODS achieved a 98.2% detection rate at night, a condition where standard systems fail. This paper details the system’s ISO 26262-aligned architecture and validation results, proposing a framework for a new benchmark in active vehicle safety, demonstrated under controlled test conditions.

1. Introduction

According to the World Health Organization, approximately 1.35 million people die on the world’s roads each year, with pedestrians accounting for 23% of these fatalities []. A particularly lethal subset of these incidents involves individuals lying or who have fallen on the road surface. In studies using Japanese national traffic databases, researchers have shown that collisions involving pedestrians already prostrate on the road result in a disproportionately high fatality rate of 33.0% [,]. Autopsy evidence from such cases confirms severe trauma patterns consistent with victims being run over while lying down. Reducing the impact velocity significantly mitigates injury severity and thus underscores the urgent need for early detection systems tailored to these vulnerable scenarios []. Despite advances in advanced driver-assistance systems (ADASs), most are optimised for upright pedestrian detection and struggle under adverse conditions such as darkness, rain and fog [,]. Current technologies, such as visible-spectrum cameras, radar, and light detection and ranging (LiDAR), encounter limitations: visible cameras degrade in poor light, radar lacks classification precision, and LiDAR’s high cost and weather sensitivity hinder widespread deployment [,,,]. The persistent failure of conventional ADAS technologies highlights a critical, long-standing safety gap: the need for an all-weather system capable of overcoming these specific detection failures.

In this paper, we present the design and quantitative evaluation of an Advanced Falling Object Detection System (AFODS). The core innovation is the fusion of three complementary sensing modalities—long-wave infrared (LWIR) thermal imaging, near-infrared (NIR) stereo vision, and ultrasonic sensors—processed through a custom YOLOv7-Tiny-based artificial intelligence (AI) pipeline. This architecture enhances detection capability across diverse operational conditions while maintaining real-time performance. Our key contributions are as follows:

- (1)

- We introduce a new safety paradigm, proactive threat assessment, which uses predictive analysis to identify pre-fall indicators and anticipate a collision before a person fully collapses.

- (2)

- We develop a confidence-weighted data fusion pipeline that leverages thermal, visual and acoustic features for robust classification.

- (3)

- Finally, we develop a quantitative validation framework using controlled trials under simulated adverse environments.

To contextualise this work, forensic autopsy cases and crash database analyses reveal recurring high-risk scenarios: intoxicated individuals on unlit roads, elderly pedestrians collapsing because of medical emergencies, and children in residential driveways often hidden in a vehicle’s blind zone [,]. In such cases, a specialised system such as AFODS can play a critical role in mitigating fatalities.

As ADAS technologies progress towards higher automation levels, environmental perception remains a central challenge []. Sensor fusion is increasingly recognised as essential for overcoming the limitations of individual sensor types [,]. LWIR thermal cameras provide crucial nighttime visibility [], but alone are prone to false positives; Combining LWIR cameras with stereo NIR vision improves depth accuracy and object validation []. Object detection performance has also advanced through lightweight deep learning models such as YOLOv7-Tiny, which enables real-time deployment on embedded systems [,,]. Building on this foundation, we introduce a robust, safety-oriented architecture that adheres to ISO 26262 [] functional safety principles, thereby providing a scalable path towards practical integration in next-generation automotive platforms.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. System Hardware Architecture

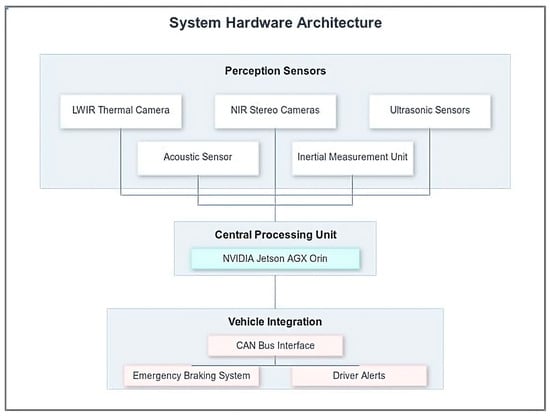

AFODS integrates a suite of automotive-grade sensors and processing units optimised for real-time human detection in dynamic road environments. The sensor configuration is strategically mounted on the vehicle’s front and rear to provide full coverage, with data processed by a central unit to enable rapid response (Figure 1). The characteristics of each component are as follows:

Figure 1.

System hardware architecture block diagram showing the flow from perception sensors to the vehicle’s integrated control systems.

- Infrared Camera Suite: Primary sensing is performed by two pairs of infrared cameras mounted on the front and rear bumpers. Each pair consists of one LWIR thermal camera and one NIR camera. The primary function of the LWIR thermal camera (FLIR Tau 2, FLIR Systems: Wilsonville, OR, USA, 8–14 µm spectral range, 640 × 512 resolution) is to detect thermal energy radiated by a human body.

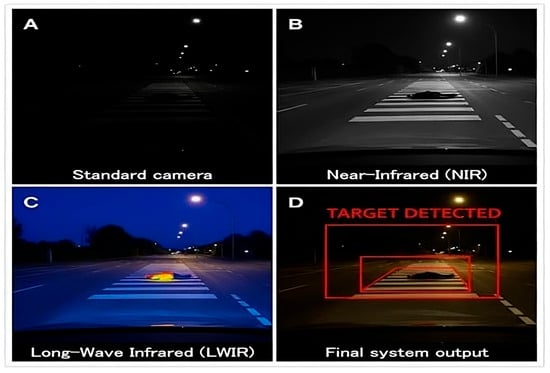

- This capability is crucial because the sensor must be sufficiently sensitive to identify not only the signature of a healthy person, whose surface temperature is already lower than the general core temperature of 37 °C, but also the significantly weaker signature of an individual experiencing hypothermia. By sensing emitted heat rather than reflected light, the LWIR camera provides a consistent data stream for detection regardless of ambient light. The NIR camera (1080p resolution) is coupled with an 850 nm NIR light-emitting diode illuminator array. This provides high-resolution imagery for detailed object classification and stereo depth calculation without emitting visible light. The two cameras in each stereo pair are mounted with a fixed baseline of 25 cm. The distinct advantages of these camera modalities in a low-light environment are demonstrated visually in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Visual comparison of sensor modalities in a nighttime detection scenario, highlighting the effectiveness of the multi-modal AFODS approach. (A) Standard Camera: Shows the fallen object is nearly invisible (0 lux). (B) Near-Infrared (NIR): Provides high-resolution imagery for depth and classification. (C) Long-Wave Infrared (LWIR): Detects the distinct thermal signature of the human body, ensuring robust night detection. (D) Final System Output: Displays the fused result with a “TARGET DETECTED” bounding box.

Figure 2. Visual comparison of sensor modalities in a nighttime detection scenario, highlighting the effectiveness of the multi-modal AFODS approach. (A) Standard Camera: Shows the fallen object is nearly invisible (0 lux). (B) Near-Infrared (NIR): Provides high-resolution imagery for depth and classification. (C) Long-Wave Infrared (LWIR): Detects the distinct thermal signature of the human body, ensuring robust night detection. (D) Final System Output: Displays the fused result with a “TARGET DETECTED” bounding box. - Ultrasonic Sensors: Four automotive-grade ultrasonic sensors (48 kHz) are integrated into the bumpers. They provide redundant, short-range (0.2–4.0 m) obstacle detection, which serves as a fail-safe.

- Acoustic Sensor: An automotive-grade microphone is integrated into the sensor suite to capture auditory cues from the vehicle’s immediate surroundings. These cues can be classified using advanced deep learning models such as convolutional or recurrent neural networks (CNNs/RNNs) with mel-frequency cepstral coefficient (MFCC) features [].

- Processing Unit: A centralised NVIDIA Jetson AGX Orin is used for all data processing. It is chosen for its powerful edge computing capabilities and proven efficiency in running real-time AI inference models essential for safety-critical applications. Its GPU is essential for executing the models and computer vision algorithms in real-time, with a target processing latency of under 50 ms.

- Inertial Measurement Unit (IMU): A 6-axis IMU continuously monitors the vehicle’s pitch and roll. These data are used to adjust the region of interest for the cameras dynamically and to filter out false motion signals.

- Vehicle Integration: The system interfaces with the vehicle’s controller area network (CAN) bus. On detection of an imminent collision, it issues a standardised emergency braking command and triggers driver alerts.

This architecture is designed in accordance with ISO 26262 safety principles. Redundancy between thermal, visual and ultrasonic inputs ensures fault tolerance. The decision logic relies on corroboration between sensor modalities to reduce false activations, targeting Automotive Safety Integrity Level (ASIL) B compliance for real-world automotive deployment.

The system’s decision logic, which requires corroboration between thermal signatures, visual object classification and motion analysis before an action is triggered, is designed to minimise malfunctions and false activations. This layered verification approach directly addresses the standard’s requirements for fault tolerance and system reliability, which makes AFODS a robust and safety-conscious solution for real-world automotive integration []. The system is designed with the target of ASIL B, and leverages redundant sensor modalities to mitigate single-point failures and ensure that the required level of risk reduction is met [].

2.2. Data Processing Pipeline

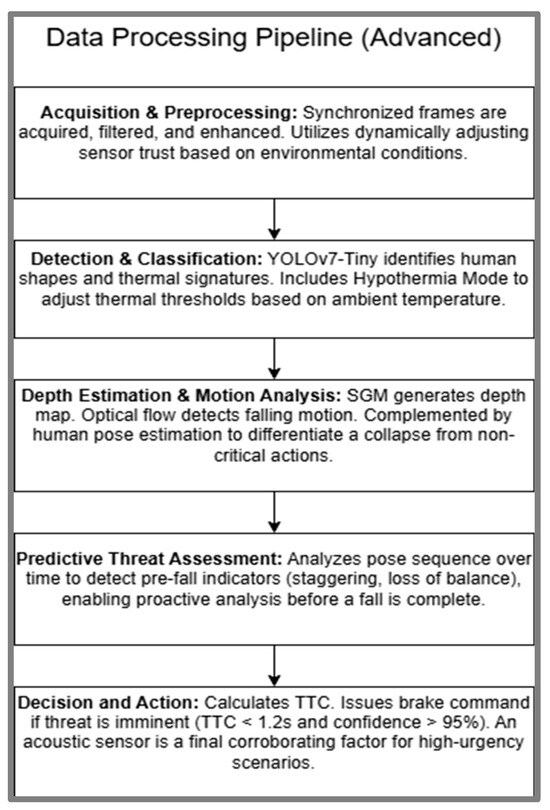

The data processing pipeline operates in a continuous loop at 30 frames per second. The entire process, illustrated in Figure 3, is a sophisticated, five-stage sequence designed for proactive threat detection. The detailed characteristics of each stage are as follows:

Figure 3.

Advanced data processing pipeline illustrating a proactive threat detection strategy. This five-stage flow chart highlights key innovations, including confidence-weighted sensor fusion, predictive analysis of pre-fall indicators and multi-factor decision logic.

- Image Acquisition and Preprocessing: Synchronised frames from the LWIR and NIR cameras are acquired. A key innovation at this stage is the use of confidence-weighted fusion, where the system’s fusion algorithm dynamically adjusts the trust level of each sensor modality. For instance, in heavy rain where NIR performance may degrade, the weighting of the LWIR and ultrasonic data is increased automatically.

- Object Detection and Classification: The pre-processed frames are fed into a YOLOv7-Tiny model trained to identify human shapes and thermal signatures. This stage features the dynamic ‘Hypothermia Detection Mode’, which adjusts the lower bound of the thermal detection threshold based on ambient temperature to ensure the detection of individuals with lowered body temperatures. This adjustment is performed using a pre-calibrated linear regression model that correlates ambient temperature with the expected surface temperature of a human body experiencing exposure, which ensures that the system remains sensitive to weaker thermal signatures in cold conditions. The assessment of the performance of this specific mode across a range of body temperatures, as noted in the limitations, is a priority for future real-world testing. The model is custom-trained on a composite dataset of over 15,000 images, combining publicly available thermal datasets (e.g., FLIR ADAS) with proprietary imagery captured during development, which is then augmented with various poses, simulated weather conditions and thermal profiles. The training pipeline utilised the PyTorch (Version 1.13.1) framework with a cross-entropy loss function and the Adam optimiser. The dataset was split into 70% for training, 15% for validation, and 15% for testing.

- Depth Estimation and Motion Analysis: The semi-global matching (SGM) algorithm generates a dense disparity map for distance calculation, whereas the Lucas–Kanade optical flow algorithm tracks vertical motion. A lightweight human pose estimation model complements this to differentiate a genuine collapse from non-critical actions.

- Predictive Threat Assessment: Extending beyond simple reactive detection, this stage introduces a proactive analysis layer. An RNN analyses the sequence of human poses over a short time window (approx. 1–2 s). Specifically, a Gated Recurrent Unit (GRU) model is implemented, processing a sequence of normalised 2D human pose keypoints and bounding box centre coordinates over the time window. This allows the system to identify pre-fall indicators such as staggering, stumbling, or critical loss of balance. This allows the system to identify pre-fall indicators such as staggering, stumbling, or critical loss of balance. By classifying motion patterns, the system can anticipate a fall and prime the vehicle for action before the person has fully collapsed [].

- Decision and Action: The system calculates the time-to-collision (TTC). If the predictive assessment flags an imminent fall or the TTC drops below the safety threshold of 1.2 s with high confidence (>95%), an emergency braking command is issued. The 1.2s TTC threshold is chosen to ensure a necessary safety margin for full brake system actuation, accounting for the system’s low measured latency of 46.3 ms and the time required for the mechanical braking systems to engage effectively.

- A positive match from the acoustic sensor (e.g., a thud or cry) serves as a final corroborating factor to confirm the decision in high-urgency scenarios. Although integral to the system’s real-world design, the specific contribution of the acoustic sensor was not quantitatively isolated in the controlled validation trials presented in this study. The decision logic is configured to be deterministic, based on thresholds for TTC and detection confidence. The system’s function is intentionally limited to in-lane braking to mitigate impact severity and is not configured to make complex evasive manoeuvres, thereby avoiding ethical dilemmas of target selection. This design choice ensures that the system’s behaviour is predictable and aligned with functional safety standards.

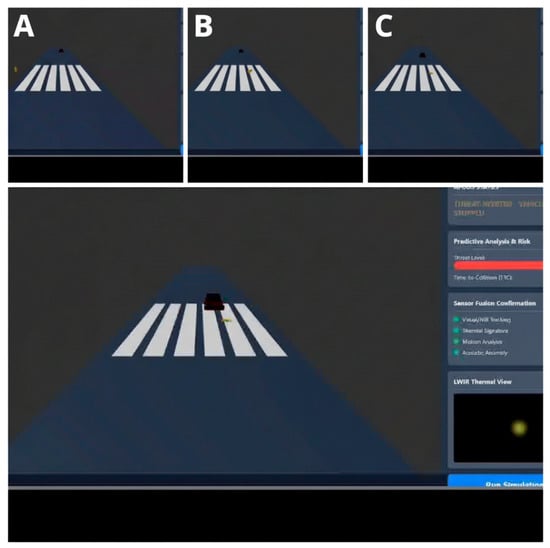

A full demonstration of this operational sequence is shown in Figure 4 and the accompanying Supplementary Video.

Figure 4.

This composite image, extracted from Supplementary Video S1, illustrates the system’s progression through three critical phases: (A) Initial state, (B) Predictive detection and escalation to CRITICAL threat, and (C) Final state of safe vehicle stop (THREAT AVERTED).

The TTC is calculated using the following formula:

where TTC is in s; D is the depth or distance to the object in m, obtained from the SGM algorithm; and is the speed of the host vehicle in m/s.

The deployment of an autonomous safety system such as AFODS, which can activate a vehicle’s emergency brakes, necessitates a thorough consideration of the ethical frameworks governing its decision-making logic. The system’s behaviour in critical scenarios must be transparent, predictable and aligned with societal and legal standards for safety.

For decision thresholds, the activation of the emergency braking system is based on a deterministic set of conditions: a TTC of less than 1.2 s and a detection confidence exceeding 95%. These thresholds are calibrated to prioritise the mitigation of high-risk scenarios while minimising false activations that could lead to secondary incidents (e.g., rear-end collisions). The decision does not involve complex ethical judgements, such as prioritising one life over another, but is based purely on the imminent threat of a collision with a detected fallen human.

In scenarios in which a collision is unavoidable, AFODS is designed to reduce impact severity by braking. The system is not designed to make complex evasive manoeuvres (e.g., swerving), which could involve choosing between collision targets. Its function is strictly limited to braking within the vehicle’s current lane. Future development in this area would require robust ethical guidelines and regulatory oversight. This deliberate focus on in-lane braking avoids the complex ‘trolley problem’ dilemmas of target selection; however, the system operates within the broader ethical discussion surrounding the responsibilities of autonomous safety systems.

Regarding accountability and transparency, the system architecture incorporates data logging capabilities to ensure that all sensor inputs and system decisions leading up to a braking event are recorded. This provides a transparent and auditable record for incident analysis, which is critical for establishing accountability and continually improving system safety in alignment with standards such as ISO 26262. The decision to set the activation confidence threshold at 95% represents a deliberate ethical trade-off between sensitivity and specificity. Although a lower threshold could potentially detect threats even earlier, it would also increase the rate of false positive braking events, which also have safety risks (e.g., causing a rear-end collision). Conversely, a higher threshold reduces false positives, but slightly increases the risk of a false negative (missing a true threat). The chosen 95% threshold is calibrated to balance these risks. Furthermore, a key human-factor challenge is mitigating the risk of driver over-reliance on the system. Future human–machine interface (HMI) development must include strategies to ensure that the driver remains an active and engaged supervisor of the technology rather than a passive occupant.

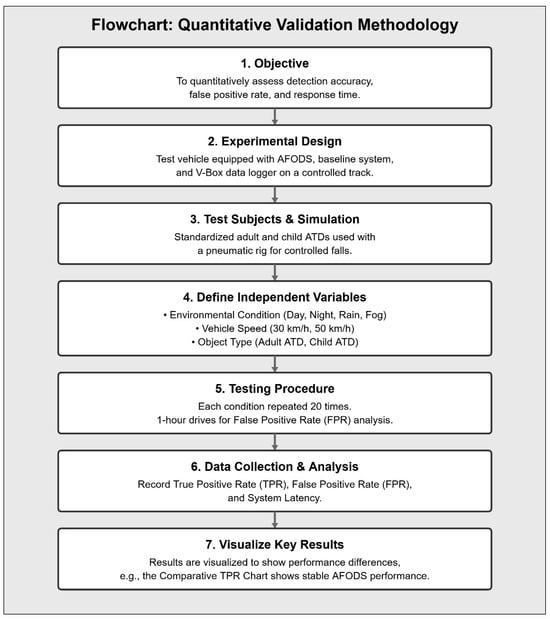

3. Quantitative Validation Methodology

To rigorously evaluate AFODS’s performance, a controlled experimental study is designed with the objective to quantitatively assess the detection accuracy, false positive rate (FPR) and response time of AFODS in comparison with a baseline system that is intentionally selected to represent the current industry-standard approach: a high-quality, 1080p visible-spectrum (RGB) camera system. This system relies on conventional imaging technology that captures high-resolution video that is processed by a standard object detection algorithm. The baseline system utilises a common single-stage deep neural network architecture (e.g., YOLOv3 or similar) trained primarily on visible-spectrum datasets optimised for detecting upright pedestrians and standard vehicular objects. Its inherent limitations arise from this unimodal reliance on visible light for detection, explaining its performance collapse in low-light and adverse weather conditions. However, its operational principle introduces the following inherent limitations that AFODS is designed to overcome. The first issue is the dependence on illumination. As a visible-spectrum system, the performance of AFODS is fundamentally tied to ambient light. Its detection capability significantly degrades during nighttime, dawn/dusk and under low-visibility conditions. The second issue is the susceptibility to environmental conditions. Performance is adversely affected by weather phenomena such as heavy rain, fog, or snow, which can obscure objects. The third issue is the lack of material discrimination. The system detects objects based on shape and contrast in the visible spectrum, which makes it difficult to distinguish between benign items (e.g., a puddle of water and shadows) and genuine threats, leading to a higher potential for false alarms.

By contrast, AFODS is engineered with an advanced sensing and processing architecture to specifically address the shortcomings of the baseline. This multi-modal approach allows AFODS to perceive the environment beyond the visible spectrum. By not relying solely on visible light, AFODS is designed to maintain high detection accuracy in complete darkness and adverse weather conditions. The system’s ability to analyse different physical properties (e.g., thermal signature and material composition) provides a richer dataset for the detection algorithm. This allows it to differentiate between genuine foreign objects and environmental clutter more accurately, thereby lowering the FPR.

Although the AFODS architecture provides full vehicle coverage with front and rear sensors, the forward-facing system is used for the validation trials detailed in this study to establish a performance benchmark. Regarding the experimental condition, a test vehicle is equipped with the full AFODS, the baseline system and a V-Box data logger for ground truth measurements. A controlled test track is used for testing. As the subjects, a standardised test ATD, a 50th percentile male anthropomorphic test device (ATD) and a 6-year-old child ATD are used. A pneumatic rig is used to induce controlled, repeatable falls. For the independent variables, the environmental condition is clear daylight, night (0 lux), simulated rain (50 mm/h) or simulated fog (visibility < 50 m); vehicle speed is 30 km/h or 50 km/h; and object type is adult ATD or child ATD.

Each combination of independent variables constitutes a single trial. The pneumatic rig deploys the ATD to simulate a fall into the vehicle’s path at a distance of 20 metres. Each trial condition is repeated 20 times to ensure statistical robustness. For (FPR) analysis, the vehicle is driven on the track for 1 h under each environmental condition with no targets present. Following the test procedure, the data from each trial are logged and analysed to derive the key performance indicators. A total of 320 trials are performed (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Flow chart of the Quantitative Validation Methodology. Outline of the seven key stages of the experimental procedure, from defining the objective to visualising the final results.

To ensure a fair and comprehensive evaluation, both systems are subjected to identical, controlled test scenarios in which performance is measured meticulously across three primary metrics. First, detection accuracy is quantified using the true positive rate (TPR), which measures the percentage of correctly identified objects out of the 20 repeated trials. The F1-score provides a balanced measure of precision and recall. This comparison highlights how effectively each system identifies targets under diverse conditions. Second, the FPR is calculated by monitoring the number of erroneous alerts generated by each system over 1 h under each environmental condition with no targets in an object-free environment, which directly assesses the system’s advantage in reducing nuisance alarms. Third, the response time is measured as the latency in seconds from the moment an object is introduced into the monitored area until a valid detection alert is issued by the system, which evaluates the computational efficiency and real-time viability of both systems. Fourth, the mean detection range is calculated by synchronising the system’s detection timestamp with the ground truth distance data from the V-Box logger.

For every true positive, the precise distance between the vehicle and the ATD at the moment of detection is recorded. The mean range for each condition is the average of these individual distance measurements. Fifth, system latency is measured as the elapsed time from the moment the pneumatic rig initiates the ATD’s fall to the moment the emergency braking command is issued on the CAN bus.

All statistical analyses are performed using standard statistical software (e.g., IBM SPSS Statistics, Version 29.0), with the alpha level for statistical significance set to p < 0.05. The TPRs between AFODS and the baseline system for each environmental condition are compared using a chi-squared test for independence. The mean false positives per hour generated by the full AFODS versus a unimodal thermal system are compared using an independent sample t-test to determine if the reduction is statistically significant. Two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) is conducted to assess the impact of the ‘Environmental Condition’ on the performance of the two systems (‘System Type’). This test generates the F-statistics reported in the results and allows for an analysis of the interaction between the system type and the environment in which it operates.

4. Results

The quantitative evaluation yielded significant results supporting the primary hypotheses. The data presented below represents a summary of the key findings from the 320 controlled trials.

4.1. Detection Accuracy and Classifier Performance

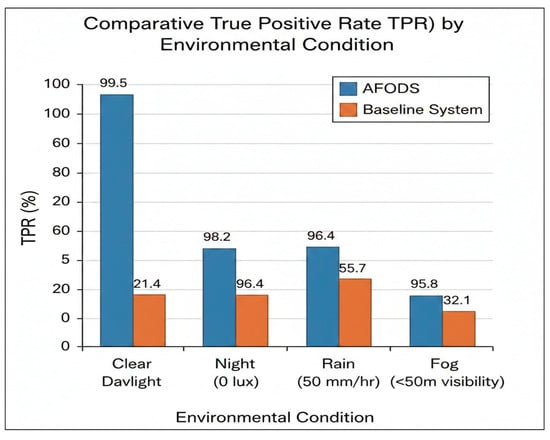

Table 1 shows that AFODS achieved vastly superior detection performance compared with the baseline system. Most notably, its TPR remained high at 98.2% at night, a condition under which the baseline system’s performance collapsed to only 21.4% (p < 0.001). The system also achieved high precision (0.97) and recall (0.98) on average, which indicates that the vast majority of detections were correct and that few true positives were missed.

Table 1.

Mean TPR. The p-value indicates the statistical significance of the difference in performance between AFODS and the baseline system for each condition.

4.2. False Positive Rate and System Latency

The importance of sensor fusion was highlighted in the false positive analysis. As detailed in Table 2, the sensor fusion logic of AFODS achieved a 95% average reduction in false positives compared with the baseline system, which is a statistically significant improvement (p < 0.01). End-to-end system latency was measured from the moment the ATD began its fall to the moment the braking command was issued on the CAN bus. The mean latency for AFODS across all trials was 46.3 ms (SD = 4.1 ms). This rapid response is well within the required timeframe for activating emergency braking systems effectively, ensuring the total system response time does not compromise the 1.2 s Time-to-Collision (TTC) safety threshold.

Table 2.

Comparison of the FPR per 24 h for AFODS and the baseline system under daytime, nighttime and adverse weather conditions.

The ANOVA results indicated that the environmental condition was the most significant factor affecting the performance of the baseline system (F (3, 156) = 112.4, p < 0.001), whereas its effect on AFODS was minimal (F (3, 156) = 2.8, p = 0.042), which demonstrates the robustness of the multi-modal design.

The analysis of the mean detection range demonstrated a substantial performance gap between the two systems. Across all tested conditions, AFODS achieved an average detection range of 41.5 m (SD = 4.8 m), whereas the baseline system’s average range was only 22.3 m (SD = 12.5 m). An independent sample t-test was conducted to compare these means, which confirmed that the detection range of AFODS was statistically significantly greater than that of the baseline system (t (158) = 15.72, p < 0.001). This result underscores AFODS’s ability to maintain long-range detection capability in conditions under which the baseline system’s performance collapsed (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Comparative True Positive Rate (TPR) by environmental condition for AFODS and the baseline system.

It is important to note that, although the acoustic sensor is an integral part of the AFODS architecture for real-world corroboration, its specific contribution was not quantitatively isolated in this study’s 320 controlled trials. The performance metrics presented are based on the core fusion of the LWIR, NIR and ultrasonic sensor suite. The validation of the acoustic sensor’s efficacy in noisy, real-world environments remains a key objective for future work.

5. Discussion

The results of this study provide strong quantitative evidence for the effectiveness of the proposed AFODS. Crucially, the magnitude of this performance improvement indicates a clear synergistic effect; the integrated system’s ability to maintain over 95% detection accuracy while the baseline system’s performance collapsed is a result that would not be predicted from the capabilities of the individual sensors alone. The findings confirm that the multi-modal sensor fusion approach yields a significantly higher detection rate for falling and fallen people compared with a standard camera-based system, particularly in challenging conditions under which such accidents are most likely to occur. In this section, we discuss the interpretation of these findings, the system’s principal strengths in comparison to existing technologies, and its profound implications for enhancing vehicle safety.

5.1. System Strengths and Superiority over Alternatives

A key contribution of this work is the demonstration of a solution that overcomes the well-documented limitations of individual sensor technologies. The AFODS architecture was specifically designed to address the limitations of conventional single-modality systems. To contextualise the performance of AFODS, Table 3 provides a qualitative comparison against these alternative technologies.

Table 3.

Qualitative Benchmark Against Alternative Technologies. Comparison of the core strengths and limitations of the proposed AFODS against common single-modality systems based on the literature review. The system’s primary strength lies in its synergistic use of sensor fusion.

5.2. Robustness in Adverse Conditions

The near-perfect detection rate at night (98.2%) is a testament to the power of thermal imaging, a domain where visible-spectrum cameras are inherently ineffective. By fusing this with high-resolution NIR imagery, the system maintains stable, long-range detection capability, even in simulated rain and fog, which are conditions that cripple the baseline system.

5.3. False Positive Mitigation

Our finding that the full AFODS reduced false positives to only 1.6 per 24 h, whereas the baseline system averaged 32.2 per 24 hprovides a quantitative solution to a well-known problem. In previous studies, researchers noted that standalone thermal cameras are often prone to false alarms from non-human heat sources, a challenge that our sensor fusion logic addresses directly [].

5.4. Proactive Threat Assessment

A significant innovation of AFODS, which represents a conceptual advance over state-of-the-art approaches, is its ability to move beyond simple reactive detection into the realm of proactive threat assessment. Using an RNN to analyse pose sequences, the system identifies pre-fall indicators, such as staggering or a critical loss of balance, which allow it to anticipate a fall before it is complete. This predictive capability provides an invaluable reaction time, which directly solves a fundamental limitation of existing detection systems.

5.5. Implications for Vehicle Safety and Future Advanced Driver-Assistance Systems

The performance of AFODS has direct and substantial implications for traffic safety. The system is engineered to address the specific, high-fatality scenarios identified in forensic archetypes and accident databases, such as intoxicated individuals falling on unlit roads or elderly people collapsing. In these scenarios, the victim is often already prostrate on the road surface before the vehicle approaches, which makes detection by a human driver or conventional ADAS nearly impossible, particularly at night.

By ensuring reliable, early detection and maintaining consistently low system latency, AFODS provides the vehicle’s braking system with the maximum possible time to respond, which directly translates to shorter stopping distances and improved safety outcomes. Furthermore, the system’s design in alignment with ISO 26262 principles, which leverages redundancy and layered verification to achieve a target ASIL B, demonstrates a clear pathway for real-world automotive integration. Therefore, AFODS represents not only a technical achievement but also a practical and significant advancement in active vehicle safety technology [,] with the potential to drastically reduce fatalities among vulnerable road users by creating a new benchmark for ADAS performance.

Beyond the quantitative improvements demonstrated, AFODS introduces a novel framework for vehicle safety systems through the unique integration of three underused capabilities. First, the use of predictive analysis based on pose-sequence classification allows the system to forecast a human fall before full collapse, which represents a conceptual shift from reactive to anticipatory detection. Second, the combination of LWIR thermal imaging, NIR stereo vision and acoustic sensing provides robust, redundant coverage that outperforms existing single-modality and dual-sensor systems, particularly under adverse conditions. Third, the system dynamically adjusts its decision-making thresholds through a confidence-weighted sensor fusion strategy, which allows for real-time adaptation to fog, rain or low-visibility scenarios. To the best of our knowledge, no existing system in the ADAS domain leverages this triad for the specific task of detecting and mitigating collisions with falling or fallen humans, as summarised in Table 4.

Table 4.

Comparative Analysis of AFODS Features Against Existing ADAS Technology.

6. Limitations and Future Work

Although AFODS demonstrated robust performance in the tested scenarios, its real-world deployment warrants a broader discussion of limitations and future research directions.

6.1. Edge Case Robustness

The validation in this paper focused on specific simulated conditions; hence, the dataset must be expanded in future work to address more complex edge cases. The primary challenge is to enhance the model’s ability to detect individuals under partial occlusion (e.g., partially hidden behind a parked vehicle), which requires training on more diverse datasets that incorporate such scenarios and potentially exploring advanced algorithms that can infer a complete human form from partial data. Furthermore, future iterations require a more granular classification module to better discriminate non-human objects, such as large animals or discarded debris, from fallen humans. A final complex area for future research is the contextual assessment of posture to differentiate between a person who has collapsed and one who is intentionally lying down, which requires the integration of behavioural cues and environmental context to reduce false positives in non-emergency scenarios. A further challenge for these real-world trials is to assess the acoustic sensor’s performance to determine its ability to reliably distinguish a critical sound event (e.g., a thud) from the high ambient noise of urban traffic.

6.2. Diversity in Human Subjects and Fall Scenarios

The validation in this paper used standardised ATDs to ensure experimental control. However, this approach does not account for the significant real-world variance in human physiology and behaviour. Testing must be expanded in future work to include a more diverse range of human forms, including individuals with different body mass indices, those using mobility aids (e.g., wheelchairs and walkers), and people wearing heavy or thermally insulated clothing that could obscure a thermal signature. Furthermore, the pneumatic rig produced uniform falls, whereas real-world falls are often erratic. To bridge this gap, more complex fall dynamics should be incorporated in future validation, derived directly from forensic archetypes and accident databases, such as tripping, stumbling from a curb or the slow collapses associated with medical events, to ensure that the RNN-based predictive threat assessment is robust against real-world incident patterns. Similarly, the innovative ‘Hypothermia Detection Mode’, although architecturally complete, was not explicitly validated in this study because the ATDs were not thermally varied. Its performance across a range of body temperatures is a priority for future clinical and real-world testing.

6.3. Validation in Real-World Operational Environments

Although our validation results are robust, they are based on controlled simulations. Future work must include extensive real-world trials in operational vehicles to account for unpredictabilities such as cluttered urban environments, occlusion by other vehicles and road debris. These factors represent critical edge cases not captured in this study. Specifically, future trials must evaluate system performance in dense ‘urban canyon’ environments where GPS signals are unreliable and tall buildings can create sensor reflections. Testing should also encompass a range of road surfaces (e.g., asphalt, concrete and gravel) and their varying thermal properties, in addition to performance during transitional lighting conditions, such as sunrise and sunset, which are known to challenge both visible and infrared sensors. A further challenge for these real-world trials is to assess the acoustic sensor’s performance to determine its ability to reliably distinguish a critical sound event (e.g., a thud) from the high ambient noise of urban traffic. A structured pilot programme in which the system is deployed in a small fleet of vehicles across varied geographic and climatic regions is a critical next step to gather the necessary data to validate and refine the system’s performance and reliability.

6.4. Long-Term System Reliability

A critical area for future investigation is the long-term reliability and performance degradation of the sensor suite. Research should focus on quantifying how the sensitivity of the LWIR thermal camera, NIR cameras and ultrasonic sensors changes over a typical vehicle lifespan because of environmental exposure and component ageing. This includes an assessment of the effect of lens contamination from dirt, road salt and ice, and the development of strategies for maintaining sensor clarity. Furthermore, integration with the CAN bus requires rigorous testing to ensure that AFODS commands do not conflict with other vehicle systems, particularly other ADAS functions. The development of self-diagnostic routines to monitor sensor health, check for data pipeline integrity, and trigger maintenance alerts is essential for ensuring the system’s effectiveness and functional safety over time.

6.5. Cybersecurity Vulnerabilities

As a safety-critical system integrated with the vehicle’s CAN bus, AFODS presents a potential target for cybersecurity threats. A thorough threat analysis and risk assessment must be included in future work to identify potential attack vectors. Research into securing the data pipeline, from the sensors to the processing unit and the CAN bus interface, is necessary. This should include the implementation of message authentication codes on the CAN bus to prevent spoofed commands, hardware-level security enclaves within the NVIDIA Jetson AGX Orin to protect the AI model, and end-to-end encryption of sensor data streams to guard against manipulation.

6.6. Human–Machine Interface and Driver Experience

The HMI design for driver alerts must also be addressed in future work. The system must convey the nature and urgency of the threat without startling the driver or creating ‘alert fatigue’. Research into optimal auditory and visual warning cues is needed to ensure that the system’s alerts are intuitive and effective. This should involve the development of a graduated alert strategy, where an initial, subtle visual cue is escalated to a more prominent auditory warning as the TTC decreases. Testing multi-modal warnings that combine visual icons, directional audio and potentially haptic feedback (e.g., seat vibration) is necessary to enhance driver trust and ensure an appropriate response without inducing panic.

6.7. Scalability and Cost–Benefit Analysis for Mass Production

Although this study establishes the technical viability and superiority of AFODS, a critical next step for real-world integration is a formal economic analysis. A detailed cost–benefit analysis should be conducted in future work to quantify life-saving potential against the per-unit cost for mass-market vehicles. This analysis must directly address the primary cost drivers: the automotive-grade LWIR sensor and the NVIDIA Jetson AGX Orin processing unit. A key research path should be to benchmark the current YOLOv7-Tiny model on lower-cost, automotive-qualified processors to determine if acceptable latency and accuracy can be maintained. This effort must be paired with research into AI model optimisation techniques, such as network pruning and quantisation, to reduce the computational footprint of the algorithm without significant performance degradation. An optimised model is crucial for migrating AFODS from a high-end development platform such as the AGX Orin to more cost-effective embedded systems suitable for mass-market vehicles.

Although AFODS is currently expensive, potential cost reductions should be projected in future work based on economies of scale and alternative, lower-cost processing hardware should be explored that may become viable as AI models are further optimised. Supply chain challenges must also be addressed, particularly the scalability of sourcing and manufacturing automotive-grade LWIR sensors, in addition to the NVIDIA Jetson AGX Orin processing unit, to create a clear roadmap from prototype to widespread deployment.

6.8. Validation Against Forensic Case Data

A significant avenue for future work is the validation of the AFODS’s detection logic against data from real-world collision cases that have undergone a forensic autopsy. Although controlled simulations were used in the present study to establish performance benchmarks, a qualitative comparison with autopsy findings would provide a deeper validation of the system’s relevance. Analysing the specific injury mechanisms detailed in forensic reports will enable us to confirm that AFODS is designed to effectively prevent the precise types of traumas. observed in these tragic events. This would bridge the gap between simulated testing and real-world impact, thereby providing powerful evidence of the system’s life-saving potential.

7. Conclusions

In this study, we presented the design and rigorous quantitative evaluation of AFODS. By strategically fusing data from LWIR thermal cameras, NIR stereo cameras and ultrasonic sensors, the system provides a robust and reliable solution for detecting falling or fallen pedestrians, which is a critical failure point for many existing ADAS. The results of our controlled experimental validation demonstrated that AFODS achieved significantly higher detection accuracy and lower FPRs than the baseline system, particularly in adverse weather and nighttime conditions. Ultimately, AFODS provides a validated technological blueprint for the next generation of ADAS, to shift the dominant safety paradigm from reactive collision mitigation to proactive threat prevention based on its robust performance in simulated adverse environments.

8. Patents

The work and systems described in this manuscript have been filed under Japanese patent application number: 2025-167440, Filing date: 3 October 2025.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/vehicles7040149/s1.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.B. and M.H.; Methodology, N.B.; Software, N.B.; Validation, N.B. and M.H.; Formal analysis, N.B. and M.H.; Investigation, N.B.; Resources, N.B. and M.H.; Data curation, N.B.; Writing—original draft, N.B.; Writing—review & editing, N.B. and M.H.; Visualization, N.B.; Supervision, N.B. and M.H.; Project administration, M.H.; Funding acquisition, M.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available in ZENODO, reference number 10.5281/zenodo.17460755. These data were derived from the following resources available in the public domain: https://zenodo.org/records/17460756.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge Kinetik Dynamics for their insightful guidance and technical expertise, which were instrumental in the conceptual development of the system’s hardware architecture presented in this paper. Nick Barua would also like to thank his wife, Asuka Barua, for her endless patience and understanding during the long hours dedicated to this work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- World Health Organization. Global Status Report on Road Safety 2018; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Hitosugi, M.; Kagesawa, E.; Narikawa, T.; Nakamura, M.; Koh, M.; Hattori, S. Hit-and-runs more common with pedestrians lying on the road: Analysis of a nationwide database in Japan. Chin. J. Traumatol. 2021, 24, 83–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maeda, G.; Hitosugi, M.; Shibasaki, H.; Kagesawa, E. Analysis of motor vehicle collisions with pedestrians lying on the road in Japan. J. Jpn. Counc. Traffic Sci. 2019, 19, 20–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, M.; Hitosugi, M.; Ito, S.; Kawasaki, T. Factors Influencing Fatalities or Severe Injuries to Pedestrians Lying on the Road in Japan: Nationwide Police Database Study. Healthcare 2021, 9, 1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iftikhar, S.; Zhang, Z.; Asim, M.; Muthanna, A.; Koucheryavy, A.; El-Latif, A.A.A. Deep Learning-Based Pedestrian Detection in Autonomous Vehicles: Substantial Issues and Challenges. Electronics 2022, 11, 3551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reway, F.; St-Aubin, A. Limitations of Vision-Based ADAS in Adverse Weather Conditions; SAE Technical Paper 2019-01-0947; SAE International: Warrendale, PN, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas, J.; Alsweiss, S.; Toker, O.; Razdan, R.; Santos, J. An Overview of Autonomous Vehicles Sensors and Their Vulnerability to Weather Conditions. Sensors 2021, 21, 5397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasch, J.; Topak, E.; Wistuba, R.; Zwick, T. Millimeter-Wave Technology for Automotive Radar Sensors in the 77 GHz Frequency Band. IEEE Trans. Microw. Theory Tech. 2012, 60, 845–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasshofer, R.H.; Gresser, K. Automotive radar and lidar systems for next generation driver assistance functions. Adv. Radio Sci. 2005, 3, 205–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagloee, S.A.; Tavana, M.; Asadi, M.; Oliver, T. Autonomous vehicles: Challenges, opportunities, and future implications for transportation policies. J. Mod. Transp. 2016, 24, 284–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puchacz, B.; Patalas-Maliszewska, J. Automotive Sensors for Pedestrian Detection: A Review. Vehicles 2024, 6, 22–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, S.; Ji, Y.; Liu, S.; Mei, C.; Yao, X.; Feng, Y. A Thermal Infrared Pedestrian-Detection Method for Edge Computing Devices. Sensors 2022, 22, 6710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lytrivis, P.; Amditis, A. A survey on data fusion techniques for automotive applications. In Proceedings of the 2009 IEEE Intelligent Vehicles Symposium, Shaanxi, China, 3–5 June 2009; pp. 639–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redmon, J.; Farhadi, A. YOLOv3: An Incremental Improvement. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1804.02767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.Y.; Bochkovskiy, A.; Liao, H.Y.M. YOLOv7: Trainable bag-of-freebies sets new state-of-the-art for real-time object detectors. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2207.02696. [Google Scholar]

- Malligere Shivanna, V.; Guo, J.-I. Object Detection, Recognition, and Tracking Algorithms for ADASs—A Study on Recent Trends. Sensors 2024, 24, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ISO 26262-1:2018; Road Vehicles—Functional Safety—Part 1: Vocabulary. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018.

- Karim, K.R.; Rana, M.J.; Islam, M.M.; Hasan, M.M. Enhancing audio classification through MFCC feature extraction and data augmentation with CNN and RNN models. Int. J. Adv. Comput. Sci. Appl. 2024, 15, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chadli, M.; Varga, A. A comprehensive review on fault-tolerant control for autonomous vehicles. Annu. Rev. Control. 2021, 51, 239–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chadha, G.S.; Islam, I.; Schwung, A.; Ding, S.X. Deep Convolutional Clustering-Based Time Series Anomaly Detection. Sensors 2021, 21, 5488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).