Abstract

As typical dynamic loads, electric vehicles (EVs) introduce significant uncertainty into distribution network operations due to the randomness of their travel behavior and charging demand. To achieve precise spatiotemporal forecasting of charging loads, this paper constructs a multi-dimensional transportation network model that accounts for dynamic road impedance factors and introduces a unit-distance energy consumption calculation method based on road impedance. By integrating the division of urban multifunctional zones and differentiated state-of-charge (SOC) threshold distributions across various EV types, a mapping model between travel chains and charging behaviors is established. Subsequently, large-scale travel and charging events are generated using an origin–destination (OD) probability matrix and Monte Carlo sampling to derive the spatiotemporal distribution of regional EV charging loads. Simulation results for a representative city in southwest China show that the predicted charging loads exhibit a dual-peak pattern, with significant differences across regions and vehicle types, and align well with observed load trends, validating the effectiveness and engineering applicability of the proposed method.

1. Introduction

Benefiting from multiple advantages such as environmental friendliness, low noise, and cost-effectiveness, electric vehicles (EVs) have become the fastest-growing dynamic component on the load side of power grids in recent years. To address the conflict between the stochastic charging demand of EVs and the orderly coordination of grid supply, as well as enhance the operational stability of distribution networks, rational and scientific planning and operation of charging facilities constitute a crucial factor in sustaining the healthy growth of the EV industry. To tackle this challenge, this study focuses on exploring the relationship between EV behavior and charging demand and derives the fundamental problems of charging load forecasting in charging station planning and operation. By accurately predicting the spatiotemporal distribution of charging loads, this study enhances the scientific basis of distribution network planning and operation by accounting for dynamic EV load variations.

As a special form of dynamic load, EVs exhibit attributes of both transportation means and mobile loads. Their driving behavior influences road traffic flow, and their travel behavior characteristics result in intricate charging requirements. In EV charging load forecasting research, prediction approaches are generally divided into two major categories. The first involves analyzing or applying deep learning to historical statistical data on EV charging loads to predict future load distributions. For example, Reference [1] evaluates charging demand by selecting parking locations based on the spatiotemporal travel distribution data of electric ride-hailing vehicles in Changsha, China. Reference [2] uses three months of spatiotemporal trajectory data from a subset of EVs in Beijing, China, to summarize travel characteristics from multiple perspectives and predict the spatiotemporal distribution of charging demand. Such methods require massive amounts of historical statistical data for analysis and are generally considered to lack timeliness. Another category involves trip-chain simulation and prediction based on user travel behavior. For instance, Reference [3] analyzes the travel behavior differences between private cars and taxis using partial trajectory data from private vehicles, providing insights for further forecasting of travel demand. Reference [4] analyzes taxi driving paths and predicts user travel routes by integrating external influences and driver preferences. Reference [5] applies a macroscopic travel demand model combined with a fleet or technology diffusion model to predict vehicle usage based on vehicle types. Reference [6] proposes an integrated time-series approach based on deep learning theory to analyze the travel demand and trip distance of shared vehicles. This method systematically analyzes users’ travel patterns to obtain a complete trip-chain structure and establishes a more accurate charging demand prediction model by integrating key variables such as trip origin, travel distance, departure time, and destination. Its advantages include low data dependence, high model accuracy, and flexibility to adapt to transportation networks in different regions, making it widely adopted.

Despite extensive studies on EV trip-chain modeling and load forecasting, several limitations remain. First, many existing trip-chain simulation models rely primarily on road segment length, without sufficiently incorporating static impedance factors such as traffic-signal control, intersection delay, and road hierarchy. This omission restricts the accuracy with which real traffic conditions influence energy consumption and travel time. Second, the dynamic characteristics of transportation networks—such as time-varying traffic flow, congestion levels, and period-dependent impedance—are often oversimplified or ignored, resulting in limited capability to capture temporal variations in traffic conditions. Third, most EV load forecasting approaches focus predominantly on the temporal dimension and provide limited representation of spatial heterogeneity across urban functional zones or behavioral differences among vehicle types, reducing their effectiveness in spatial load prediction.

To address these limitations, this study developed an integrated framework that incorporates both static and dynamic traffic impedance, functional zone characteristics, and heterogeneous EV behavior. By introducing signal cycle parameters, road hierarchy, and time-varying traffic flow into the impedance model, and by modeling differentiated trip patterns and SOC threshold distributions for various vehicle types, the proposed framework substantially enhances the accuracy of spatiotemporal EV charging load forecasting.

To address the above issues, the innovations of this study are as follows:

- Dynamic road impedance modeling with temporal resolution: We developed a parameterized dynamic impedance model that explicitly incorporates signal control settings (cycle length and green ratio), road hierarchy free-flow speed, and time-varying traffic flow/saturation. A mapping from impedance to travel time and unit-distance energy consumption is established to more faithfully capture time-dependent traffic conditions.

- A multi-type behavior-driven OD and Monte Carlo-based spatiotemporal forecasting framework: We constructed a full pipeline comprising behavior-driven OD generation, shortest path trip-chain construction, dynamic energy update, SOC threshold-based charging triggering, and time node load formation. Functional zone preferences and vehicle type characteristics are embedded into OD matrices, and a multi-stage Monte Carlo process produces a high-resolution spatiotemporal charging demand distribution.

To further clarify the research gap and position the proposed framework relative to existing studies, Table 1 provides a comparative summary of representative methods in EV charging load forecasting.

Table 1.

Comparative summary of representative studies on EV charging load prediction.

Based on the above research motivations, the overall framework of this study is as follows:

Section 2 systematically analyzes dynamic road impedance factors and establishes a multi-dimensional descriptive model that includes sets of nodes, road segments, time intervals, and impedance weights. On this basis, by combining the speed–flow relationship and the road impedance model, the expression for vehicle energy consumption per unit distance under given traffic conditions is derived, laying the physical foundation for subsequent SOC evolution and charging determination.

Section 3 focuses on the analysis of EV travel behavior and charging characteristics. First, a transportation network topology is constructed under multiple urban functional zones, along with a multi-scenario trip-chain analysis model. The OD probability matrix is generated based on the probability distribution of starting and ending functional zones for different EV types (PDOSE); daily trip origins and destinations are then obtained via random sampling, and travel paths are generated using the Floyd algorithm. Second, according to the operational characteristics of different EV types (private cars, taxis, and other vehicles), the probabilistic distributions of the SOC threshold and charging characteristics are defined. Finally, a charging load forecasting process that integrates the OD matrix, trip-chain simulation, and Monte Carlo sampling is proposed to obtain the spatiotemporal probability distribution of charging demand across vehicle groups.

Section 4 focuses on a transportation network model based on a typical distribution network area in a city in southwest China. Based on the trip chains and charging decisions of different EV types, the spatiotemporal characteristics of the charging load distribution within the region are simulated. Comparative analysis with load data verifies the feasibility and effectiveness of the proposed method in rationally describing EV travel behavior and accurately predicting charging loads.

2. Analysis of EV Energy Consumption Characteristics

To accurately analyze the travel behavior characteristics of urban EVs and predict the spatiotemporal distribution of charging demand, it is first necessary to precisely quantify the energy consumption of each EV during its travel behavior and movement within the transportation network. Vehicle energy consumption serves as a fundamental variable for determining subsequent charging demand and as a crucial link connecting traffic flow dynamics to the formation of power system loads. In other words, only by determining a vehicle’s energy consumption level under a given traffic environment can the dynamic variation in its SOC be further derived, thus determining whether a charging event will be triggered. This section models vehicle travel paths and performs energy consumption calculations based on transportation network modeling, dynamic and static road impedance models, and the multi-dimensional transportation network description model. By incorporating road length, travel time, and impedance characteristics from the multi-dimensional transportation network model, an energy consumption expression can be derived for a vehicle completing a single trip chain. The results of this section provide input conditions for the analysis of EV travel behavior and charging characteristics in Section 3, ensuring that subsequent charging demand determination and load forecasting are based on an energy consumption foundation that is both physically plausible and consistent with traffic flow principles.

2.1. Dynamic Road Impedance Model

The transportation network is a typical complex system, and constructing a scientifically sound transportation network model serves as the foundation for studying EV load forecasting and infrastructure planning. In an actual urban traffic system, representative locations can be abstracted into a topological graph, where intersections are defined as network nodes and connecting road segments are assigned different road attributes. Binary relationships effectively characterize the structural distribution of the transportation network [10]. Once the network topology and node–link relationships are clearly defined, the next step is to describe vehicle movement characteristics along the roads.

Based on the transportation network description model, this section develops a dynamic–static coupled road impedance model. Road impedance depends not only on static road attributes—such as road classification, length, and speed limit—but also on dynamic traffic factors including vehicle flow, segment saturation, signal control at intersections, and time-varying speed. The integrated dynamic–static impedance model can more realistically capture vehicle operating conditions under varying road environments and provides a solid basis for the subsequent calculation of vehicle energy consumption per unit distance.

2.1.1. Dynamic Traffic Flow Constraint Model

In this paper, roads are categorized as expressways, main roads, and secondary roads according to their operational properties. Higher-class roads permit greater travel speeds and exhibit stronger traffic capacity. Based on this, an enhanced dynamic traffic flow constraint model is proposed; it divides a full day into time intervals and defines an adaptive adjustment function for each road segment in time period , associated with its road classification, as expressed in Equation (1):

where represents the flow level of a road segment within time period , and is the maximum flow capacity that reflects the segment’s carrying and service ability. Parameters , , and characterize road adjustment behaviors under varying traffic conditions—namely congestion, normal flow, and free flow. Following the configuration method in Ref. [11], distinct parameter values are assigned to roads of different classifications, as summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Road classification.

2.1.2. Segment Impedance

In road impedance modeling, this study employs the saturation index to characterize the congestion level of each road segment [12]. Based on its numerical range, road conditions can be classified into four categories: free flow (0 < ≤ 0.5), light congestion (0.5 < ≤ 0.8), moderate congestion (0.8 < ≤ 1.0), and severe congestion (1.0 < ≤ 2.0). The saturation degree is defined as the ratio of segment traffic flow to its maximum capacity and serves as a key parameter reflecting road efficiency and traffic state. The saturation degree of segment during time period is calculated according to Equation (2).

The segment impedance of segment during time period is related to vehicle speed and segment saturation, and its calculation is given in Equation (3):

where and represent the segment impedance values of segment under different saturation levels during time period , and indicates the free-flow speed of segment , referring to the maximum attainable speed under ideal traffic conditions.

2.1.3. Nodal Impedance

In real-world traffic, vehicles are unavoidably affected by traffic signals when traversing intersections.; therefore, considering only segment impedance is insufficient to capture actual traffic conditions, and nodal impedance must also be incorporated [13]. During time period , the nodal impedance of is jointly determined by the signal cycle, green ratio, segment saturation, and vehicle arrival rate, as expressed in Equation (4):

where and represent the nodal impedance values under different saturation levels during time period ; , the signal cycle; , the green ratio; and , the vehicle arrival rate of the corresponding road segment. Detailed data are provided in Appendix A Table A1.

The impedance of urban road networks is influenced by both static and dynamic factors, with saturation levels serving as the core variable. The specific calculation method of the impedance model is presented in Equation (5):

where is the impedance weight of time period on road section .

2.1.4. Multi-Dimensional Transportation Network Model

Based on the preceding analysis, the transportation network and its impedance characteristics can be quantified as a multi-dimensional transportation network model , as shown in Equation (6):

where denotes the set of nodes comprising all intersections within the network; , the set of road segments covering all roads; , the set of time intervals dividing the entire day into periods; and , the set of impedance weights, recording the impedance of each road segment during each time period.

2.2. Energy Consumption Model for EV Travel Based on Dynamic Road Impedance

After establishing the transportation network topology and dynamic road impedance model, it is necessary to further convert the road traffic characteristics into energy consumption indicators for EVs. Road impedance reflects vehicle operating states under varying road conditions, while vehicle energy consumption serves as the key variable for subsequent SOC evolution and the triggering of charging events. Therefore, this section constructs a per-unit-distance energy consumption model based on the speed–flow relationship and the previously derived road segment and node impedance results, to characterize vehicle energy consumption under specific traffic conditions. This model takes road impedance as input to compute the average energy consumption per segment, thereby forming the foundation for trip-chain aggregation and total daily energy consumption calculations in Section 3.

The speed–flow relationship indicates that during actual driving, vehicle speed depends not only on road classification but also on instantaneous traffic flow and maximum throughput constraints, which directly determine vehicle energy consumption and indirectly influence the spatial–temporal distribution of EV charging demand.

Within the framework of the four-tuple transportation network model , provides the impedance weights of each road segment across different time periods. To convert impedance information into the per-unit-distance energy consumption of EVs, the travel time on segment during time period is derived from the impedance weight , and the average speed is then obtained according to the speed–flow relationship, as expressed in Equation (7).

Here, denotes the free-flow speed of road segment , representing the maximum vehicle speed under ideal driving conditions, and is the velocity-weighting coefficient, . Based on empirical measurements from EV probe data, was set to 0.68, which reflects realistic degradation of speed under congestion. Mapping converts impedance weight into travel time , and is the conversion coefficient. Through empirical fitting, impedance-based travel times are matched to observed EV travel-time data collected from EVs. The resulting value is 1.12, ensuring a physically meaningful mapping aligned with observed EV speeds.

The traction power obtained from the vehicle dynamics model [14] can be expressed as shown in Equation (8):

where represents the powertrain efficiency; , air density; , aerodynamic drag coefficient; , frontal area; , total vehicle mass; , gravitational acceleration; and , rolling impedance coefficient.

Finally, the per-unit-distance energy consumption of the EV on segment during time period can be calculated using Equation (9).

At this point, based on the transportation network topology, road impedance model, and EV travel energy consumption model, a comprehensive EV energy consumption calculation method has been established. It provides a unified input foundation for subsequent analyses: once the vehicle type and travel route are specified, its energy consumption and SOC evolution can be computed for any time period. However, the charging demand of vehicles depends not only on their energy consumption levels but also on their daily travel behaviors and charging characteristics.

3. Analysis of EV Travel Behavior and Charging Characteristics

This section focuses on the analysis of EV travel and charging behaviors. First, the probability distribution of starting and ending functional zones for different EV types (PDOSE) is utilized to establish a theoretical basis for generating the OD probability matrix . Then, based on the origin and destination pairs provided by matrix , the shortest travel path is determined using the Floyd algorithm. Subsequently, considering the usage characteristics of various types of EVs, corresponding charging behavior and charging characteristic models are developed. Finally, based on the above analyses, an integrated framework for predicting the spatiotemporal distribution of EV charging loads is proposed. Through the analyses presented in this section, an organic linkage from “road energy consumption” to “travel path generation” and further to “charging behavior” is achieved, providing a complete theoretical foundation for the simulation and validation presented in the next section.

3.1. Multi-Functional Zone-Based Transportation Network and Multi-Scenario Travel Chain Analysis

This section analyzes vehicle travel chains under multi-scenario settings based on the topology of a transportation network divided by multiple functional zones, thereby providing a more accurate representation of the spatiotemporal travel characteristics of EV groups and laying the foundation for subsequent charging load forecasting. The core study area of this paper is the central district of a typical southwestern Chinese city. For this region, a transportation network topology consisting of 30 nodes and 50 roads was constructed for case simulation. The total road length of the study area is approximately 120 km, covering a land area of about 82 km2. Detailed information on road length, classification, and capacity is provided in Appendix A Table A2.

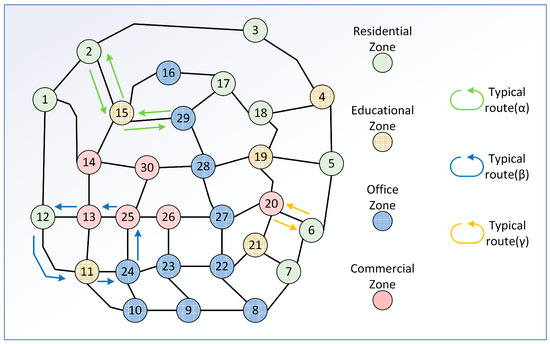

As shown in Figure 1, the transportation network topology of the study area was constructed based on a multi-functional zoning model [15], which divides the urban space into four main functional zones: residential, educational, office, and commercial zones. This division better reflects the actual travel patterns of EVs under different usage scenarios. A node functional zone identifier variable is introduced to indicate the type of area in which each node is located, where correspond to residential, educational, office, and commercial zones, respectively.

Figure 1.

Transportation network topology.

The concept of a travel chain refers to the sequence of linked travel destinations that an individual visits within a specific time frame to perform one or several activities [16]. Travel chains can thus reveal the travel patterns of EV users over a given period. During the modeling process, user travel is treated as a complex stochastic problem. By predefining the functional classification of nodes and constructing complex travel chains, the user’s travel behavior within a given time period can be quantitatively characterized, improving the accuracy and realism of subsequent charging load demand analyses. As shown in Figure 1, the typical complex travel chains can be summarized as Route(α) , Route(β) , and Route(γ) , respectively.

Considering the development of EVs in the study area and referring to the travel characteristics and charging habits of different EV types in China, vehicles are classified into three categories: private cars (Type I), taxis/ride-hailing cars (Type II), and other vehicles (Type III). The travel behaviors of multiple types of EVs within the multi-functional-zone transportation network follow certain statistical regularities. In this study, the PDOSE matrix is generated using a simple frequency-based approach. For each EV type, we first count the number of daily trips originating from each functional zone (residential, educational, office, commercial) and then compute the relative occurrence frequency, which forms the probability distribution of trip origins. Similarly, the probability distribution of trip destinations is obtained from the observed frequency of each functional zone serving as a destination. By normalizing the joint origin–destination frequencies, the PDOSE matrix is derived for each EV category and used as the basis for the Monte Carlo sampling of trip starting and ending nodes. In addition, by further refining the four functional zones to their constituent nodes, the OD probability matrix can be generated. Let and denote the functional zone identifier variables of the origin and destination node, respectively. The PDOSE is presented in Appendix A Table A3.

After randomly sampling the origin and destination of the j-th vehicle from the OD probability matrix of the transportation network, the travel path is generated using the Floyd algorithm, which yields all nodes along the route. Let denote the starting node, the destination node, and the intermediate nodes along the path. The initial departure time is , and the time of arrival at node is , with the travel time on each road segment denoted as . In assuming that the initial battery state of the EV is , and its remaining charge upon reaching node is , the energy consumption on each segment follows the relationship expressed in Equation (10):

where is the loss coefficient representing the battery energy losses other than traction energy consumption; , the driving distance between nodes and ; and , the energy consumption per unit distance for the given vehicle type.

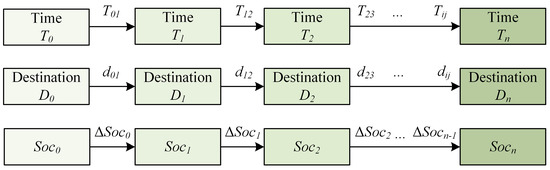

Finally, the spatiotemporal variation in the battery state for the j-th vehicle can be illustrated as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

The spatiotemporal variation in the battery state.

3.2. Charging Characterization Based on Multiple Types of EVs Analysis

After a user completes the trip and arrives at the destination, if the charging threshold is higher than the remaining battery level , a charging demand is triggered. The vehicle will then travel to the nearest charging station, where the dwell time consists of two parts: queuing time and charging time.

Before simulating EV travel behaviors, it is necessary to analyze the key characteristics within the travel chain. The temporal chain includes departure time, dwell duration in each functional area, and return time, while the spatial chain primarily covers the trip origin and destination. The three types of vehicles exhibit distinct differences in travel patterns, dwelling behavior, charging mode, and SOC threshold settings. Detailed classification is presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Comparison of EV types and charging characteristics.

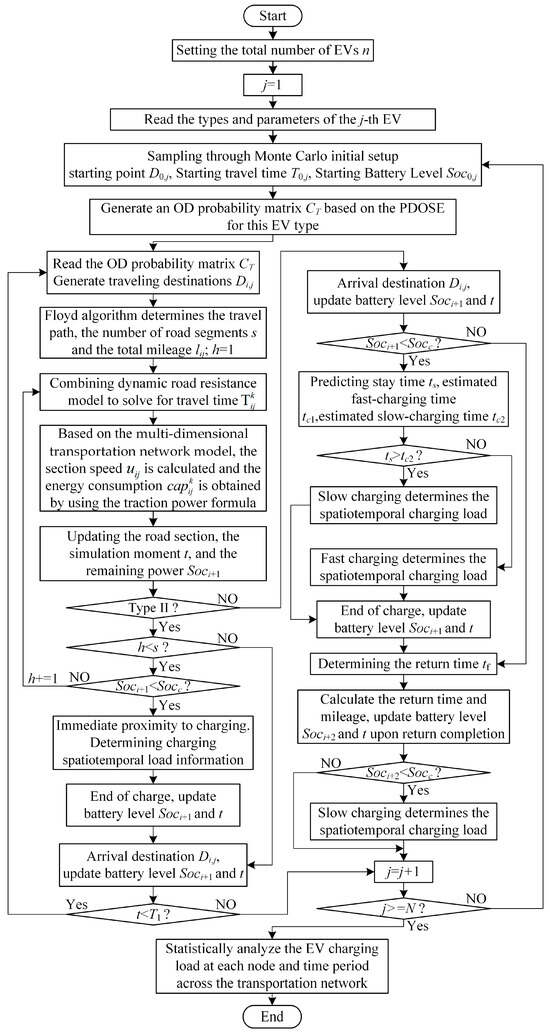

3.3. Spatiotemporal Prediction Process of EV Charging Load

The Monte Carlo method demonstrates strong effectiveness and consistency in large-scale simulation experiments [17]; therefore, this study employed it to simulate EV travel behavior and to predict the spatiotemporal distribution of charging load accordingly. The specific process is illustrated in Figure 3 and can be summarized as follows:

- Travel Chain and Probability Matrix Construction: Based on the PDOSE, the OD probability matrix is generated as the input for Monte Carlo sampling.

- Vehicle Initialization: At simulation time , the Monte Carlo method is used to randomly determine the initial location , departure time , and initial battery state for the j-th EV.

- Destination Generation: Destination is determined through Monte Carlo sampling based on OD probability matrix If the origin and destination are the same, it is assumed that the vehicle has no travel demand during this period.

- Path Travel and Energy Consumption Calculation: Using travel chain analysis and the Floyd algorithm, the travel path and passing nodes are obtained. The vehicle departs from the origin, and the travel time for each road segment is determined based on the dynamic road impedance model. Then, using the traction power formula from the vehicle dynamics model, the unit-distance energy consumption for each segment is calculated.

- State Update: Upon arrival at destination , the current simulation time and vehicle state parameters are updated, and is set as the starting point for the next trip.

- Charging Determination: Based on the evolution of the vehicle, it is determined whether a charging demand is triggered, and the charging load, spatiotemporal location, and duration are recorded.

- Iterative Simulation: By repeating the above steps for multiple EV types across different time periods, the travel trajectories and charging behaviors of the EV fleet over a 24 h cycle can be obtained, from which the spatiotemporal characteristics of the charging load are statistically derived.

Figure 3.

Flowchart of EV charging spatiotemporal load forecasting.

4. Simulation and Analysis

4.1. Analysis of the Spatiotemporal Distribution of EV Charging Demand

Based on the transportation network topology established in the previous section, this study took a transportation network model—constructed from a typical distribution network area in a southwestern Chinese city—as the research object. A simulation analysis of the spatiotemporal distribution of the EV charging demand was conducted, considering different functional zones and vehicle categories. The total simulation period was set to 24 h. Vehicles that generate charging demand were assumed to adopt a combination of slow and fast charging according to their types, with slow- and fast-charging power set at 7 kW and 60 kW, respectively. According to the actual conditions of the selected area, this study assumed an EV penetration rate of 25% [18], introducing a total of 20,000 EVs within the region: 12,000 private cars, 6000 taxis, and 2000 other vehicles. Representative models and parameters of each EV category are presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Electric vehicle parameters.

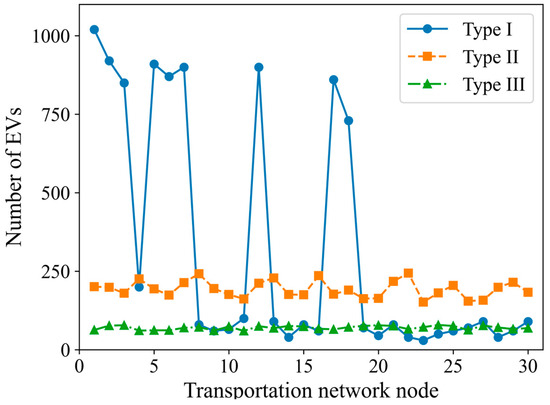

As shown in Figure 4, the initial position distribution curves of different types of EVs are obtained based on the PDOSE, functional zoning, and Monte Carlo sampling [19].

Figure 4.

Initial position distribution curve.

Figure 4 shows that for the three categories of vehicles—private cars (Type I), taxis (Type II), and other vehicles (Type III)—private cars are mainly located in residential zones, with fewer starting positions in other zones. Taxis, due to their operational characteristics, exhibit a relatively uniform spatial distribution. The number of other vehicles is small and assumed to be evenly distributed in this study. The reasonable allocation of different vehicle types according to functional zoning effectively enhances the accuracy of subsequent EV travel and charging load predictions.

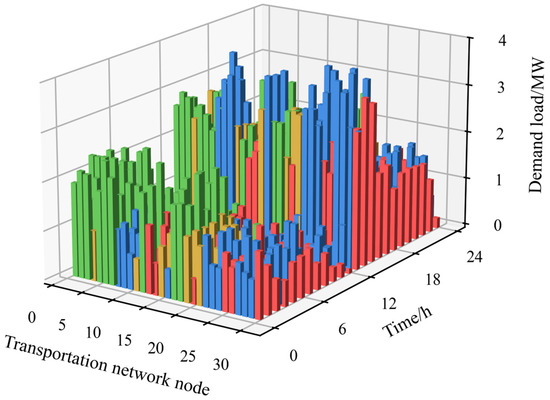

To ensure stable and reproducible simulation results, the Monte Carlo framework used in this study was configured with 10,000 iterations for each EV’s daily trip-chain [20] and SOC evolution. A fixed random seed (2025) was applied throughout the simulation to maintain reproducibility. The simulation scale covered all 20,000 EVs, and preliminary tests confirmed that the aggregated charging-demand results converge stably under this configuration. The final spatiotemporal charging demand distribution is therefore obtained based on the converged Monte Carlo outputs. With the algorithm outlined in Section 3.3, the charging load at each node was simulated and predicted over 24 hourly intervals, yielding the spatiotemporal distribution of EV charging loads shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Spatiotemporal distribution of EV charging loads. Green represents residential zones, yellow represents educational zones, blue represents office zones, and red represents commercial zones.

As shown in Figure 5, the overall distribution of the EV charging demand exhibits a distinct dual-peak pattern. The majority of charging activities occur during two peak periods [21]: 12:00–15:00 and 21:00–04:00. When considering the distribution across functional zones, it is evident that residential zones exhibit nighttime charging peaks, while office zones show daytime peaks. The charging demand [22] in educational and commercial zones is relatively low, consistent with the general travel patterns and users’ realistic charging preferences.

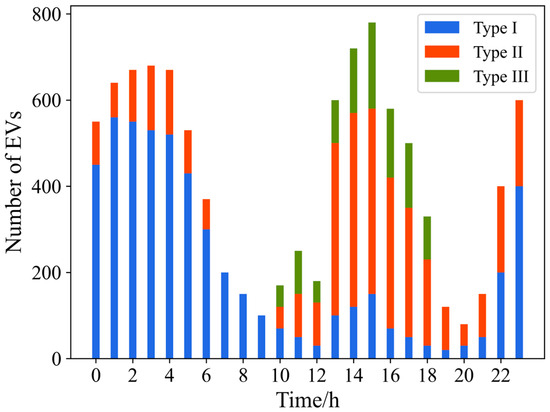

Figure 6 illustrates the distribution of charging demand across different types of electric vehicles over a 24 h period. The horizontal axis represents time (h), and the vertical axis represents the number of vehicles generating charging demand. Blue, orange, and green correspond to private cars (Type I), taxis (Type II), and other vehicles (Type III), respectively.

Figure 6.

EV charging demand by time period.

As shown in Figure 6, the charging demand displays a distinct bimodal pattern: the first peak occurs between midnight and early morning (0:00–5:00), mainly driven by private cars charging in residential zones; the second peak appears from noon to late afternoon (12:00–17:00), dominated by taxis, with some contribution from other vehicles. This distribution reflects typical travel patterns [23]—private cars tend to recharge during nighttime residence, while taxis utilize fast charging during daytime breaks or meal intervals. Overall, the charging periods of different vehicle types complement each other, resulting in a day–night dual-peak pattern in total load, which validates the model’s effectiveness in capturing realistic travel behavior patterns.

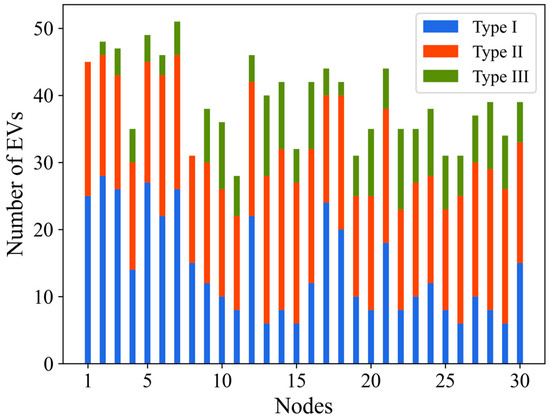

Figure 7 illustrates the spatial distribution of electric vehicle charging demand across 30 nodes within the study area. The horizontal axis represents the node indices, while the vertical axis indicates the number of vehicles generating charging demand at each node. Blue, orange, and green correspond to the three types of vehicles, respectively.

Figure 7.

EV charging demand by node.

As shown in Figure 7, there are significant differences in charging demand across the nodes. Some nodes show taller bars, indicating functional clusters or transportation hubs where vehicles frequently dwell or pass through, resulting in concentrated charging demand. In contrast, nodes with lower demand are mostly located at road termini or in predominantly residential zones. Different vehicle types exhibit distinct spatial patterns [24]: private cars are concentrated in residential zones, taxis are more evenly distributed, and other vehicles tend to cluster around commercial and office zones. This result aligns closely with the city’s functional zoning and mobility characteristics, demonstrating that the model effectively captures the spatial clustering behavior of EVs across different zones.

4.2. Comparative Analysis of Simulation Results

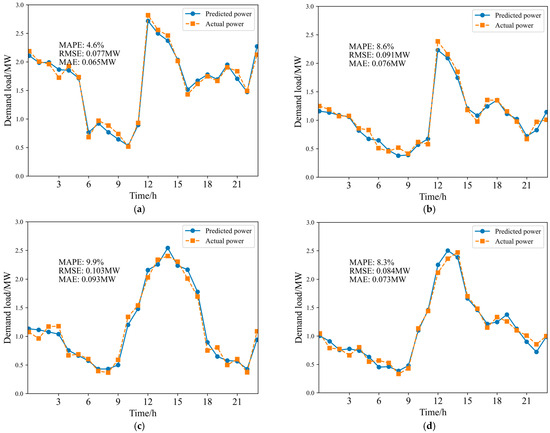

To verify the accuracy of the simulation results, the simulated EV charging demand at each node is compared with the actual power grid load data of the corresponding nodes [25]. Representative nodes 1, 4, 23, and 30 were selected from the residential, educational, office, and commercial zones, respectively, as shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Comparison line charts of predicted charging load and actual load: (a) node 1 represents the residential zone; (b) node 4, the educational zone; (c) node 23, the office zone; (d) node 30, the commercial zone.

Figure 8 compares the predicted and actual charging loads over a 24 h period for four representative nodes: node 1 (residential zone), node 4 (educational zone), node 23 (office zone), and node 30 (commercial zone). Overall, the predicted and measured curves exhibit consistent trends across all regions, accurately capturing the characteristic travel and charging patterns of EVs in different functional zones, thereby validating the rationality and applicability of the proposed model.

The charging load at the residential node shows a clear nighttime concentration, with a significant peak occurring between 23:00 and 06:00, and a minor secondary peak from 12:00 to 14:00, consistent with private vehicle users returning home for slow charging after work. The predicted results align closely with actual data, showing an MAPE of 4.6% and an RMSE of 0.077 MW. This indicates that [26] the model effectively captures residential nighttime slow-charging aggregation behavior, while minor deviations in peak values may stem from holidays or unexpected travel fluctuations.

The load profile at the educational node is more pulsating, with peaks during the morning rush (7:00–9:00) and noon (12:00–14:00), and a pronounced drop at night. This matches the typical travel concentration around school and lunch hours. The predicted curve follows the overall trend of the actual data [27], with an MAPE of 8.6% and RMSE of 0.091 MW. The relatively higher error arises from temporary campus events or parent pick-up activities that cause sudden charging fluctuations, suggesting that further optimization is needed for highly uncertain scenarios.

The office node shows a typical “high-daytime, low-nighttime” pattern, with a major peak between 12:00 and 16:00, corresponding to concentrated recharging during working hours. The predicted and observed curves nearly overlap, with an MAPE of 9.9% and RMSE of 0.103 MW, indicating that the model accurately characterizes office area travel and parking behaviors. As most vehicles here are used for fixed commutes and short business trips, the high regularity of travel patterns contributes to the model’s superior fitting accuracy.

The commercial node’s load is mainly concentrated during the late-morning to mid-afternoon period (11:00–16:00), gradually declining at night with a relatively wide peak span. The predicted and measured curves agree well, with an MAPE of 8.3% and RMSE of 0.084 MW. This pattern matches the consumption behavior in commercial zones: daytime retail, dining, and service activities drive concentrated fast-charging demand, while evening traffic reduction lowers the load. Deviations mainly stem from holiday or promotional surges, reflecting the high sensitivity of commercial charging patterns.

Overall, the peak-period deviations occur primarily in functional zones where short-term, event-driven, or behaviorally irregular factors significantly influence EV arrival rates. These localized fluctuations—such as school activities, commercial promotions, or household schedule changes—are inherently difficult to fully capture in a probabilistic [28], behavior-driven simulation framework. Nevertheless, the model demonstrates strong temporal alignment with measured load profiles, and the remaining peak mismatches are consistent with real-world behavioral variability.

To analyze the results, different dimensions must be considered, focusing on representative time periods. Table 5 summarizes the distribution of the total charging loads across different functional zones during representative time periods within a day, as well as their prediction errors compared with actual loads.

Table 5.

Average charging load distribution by functional zone over time.

In summary, the spatiotemporal characteristics of EV charging loads [29] across the four functional zones align closely with actual urban travel patterns: residential zones feature nighttime slow charging, educational zones show short daytime peaks, office zones are concentrated around midday and afternoon, and commercial zones are dominated by daytime fast charging. The MAPE across the four nodes remains below 10%, demonstrating the model’s high precision and general applicability.

4.3. Discussion

The present study relies on several necessary assumptions that may constrain generalizability. The OD probability matrix is derived from functional zone distributions rather than long-term, high-resolution GPS trajectories; while this approach offers good interpretability and avoids reliance on large-scale proprietary datasets, it may underrepresent rare trips or atypical mobility behavior. Similarly, the SOC threshold distributions and charging preferences are modeled at the category level and do not include price-sensitive or opportunistic charging strategies, which may become increasingly important as dynamic pricing mechanisms mature. The assumption of a fixed EV penetration rate and fleet composition also reflects the current conditions of the study area but cannot fully account for the rapid evolution of EV technologies and user preferences. These assumptions do not undermine the current results, but they represent important considerations for future extensions of the model to long-term scenario analysis.

Despite these limitations, the proposed framework offers meaningful implications for real-world planning and operation. By linking dynamic road impedance, trip-chain evolution, real-time energy consumption, and charging trigger behavior into a unified process, the model provides a realistic representation of how charging loads form across time and space. This makes it directly applicable to charging station siting, sizing, and functional zone-based configuration strategies. The load profiles at the four representative nodes show that areas with strong travel regularity (e.g., office districts) are suitable for orderly charging load management and potential demand–response strategies, whereas zones with high stochastic behavior (e.g., commercial districts) may require more flexible fast-charging deployment to accommodate short-term demand surges. These patterns reveal actionable insights for cities seeking to balance infrastructure investment, parking availability, and grid operational constraints [30].

Finally, while the present case study focuses on a southwestern Chinese city’s distribution network region, the modeling framework itself can be transferred to other urban systems, provided that key behavioral and traffic flow parameters are recalibrated to local conditions. The functional zone structures, cultural mobility habits, and market penetration of different EV types will influence the spatiotemporal patterns of charging demand. Thus, although the framework is generalizable, the numerical outcomes should be interpreted as city-specific. Future work may incorporate trajectory-based OD estimation, adaptive parameter evolution, and multi-year scenario simulation to further enhance applicability across diverse urban contexts.

5. Conclusions

Given that EVs serve both as means of transportation and mobile power loads, this work emphasizes constructing a multi-dimensional transportation network model that accounts for the dynamic influence of road impedance. The OD probability matrix approach is applied to describe EV travel behavior in a probabilistic and categorized manner, improving the overall reliability and precision of spatiotemporal charging load forecasting.

In the case study, charging demand patterns differ markedly among various functional areas and partly coincide with the peak periods of the local power grid. This suggests the need for targeted planning and operational strategies for different EV types and regional functions. The comparison between simulated and observed results shows that the predicted spatial distribution of EV charging demand [31] matches real-world conditions well. The developed spatiotemporal load prediction model accurately reflects residents’ travel habits, and its results are consistent with both theory and practice, confirming the model’s validity and robustness.

Overall, the findings of this study offer valuable theoretical insights and technical guidance for future research on the siting, sizing, and operational optimization of integrated PV–storage–charging infrastructures.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.L.; Methodology, K.L.; Validation, Y.X. (Yindong Xiao); Writing—original draft, Y.X. (Yuhang Xie); Writing—review & editing, Y.X. (Yuhang Xie); Supervision, J.Y.; Project administration, J.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Node feature data.

Table A1.

Node feature data.

| Node | Signal Cycle (s) | Green Ratio | Vehicle Arrival Rate |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 60 | 0.5 | 0.4 |

| 2 | 80 | 0.5 | 0.4 |

| 3 | 60 | 0.5 | 0.4 |

| 4 | 70 | 0.5 | 0.4 |

| 5 | 60 | 0.5 | 0.4 |

| 6 | 90 | 0.5 | 0.4 |

| 7 | 60 | 0.5 | 0.4 |

| 8 | 80 | 0.5 | 0.4 |

| 9 | 70 | 0.5 | 0.4 |

| 10 | 90 | 0.5 | 0.3 |

| 11 | 60 | 0.5 | 0.4 |

| 12 | 90 | 0.5 | 0.4 |

| 13 | 60 | 0.5 | 0.4 |

| 14 | 100 | 0.5 | 0.3 |

| 15 | 90 | 0.5 | 0.3 |

| 16 | 90 | 0.5 | 0.4 |

| 17 | 120 | 0.5 | 0.3 |

| 18 | 90 | 0.5 | 0.3 |

| 19 | 120 | 0.5 | 0.3 |

| 20 | 70 | 0.5 | 0.4 |

| 21 | 110 | 0.5 | 0.3 |

| 22 | 90 | 0.5 | 0.3 |

| 23 | 120 | 0.5 | 0.4 |

| 24 | 120 | 0.5 | 0.4 |

| 25 | 60 | 0.5 | 0.3 |

| 26 | 90 | 0.5 | 0.3 |

| 27 | 120 | 0.5 | 0.3 |

| 28 | 110 | 0.5 | 0.3 |

| 29 | 120 | 0.5 | 0.3 |

| 30 | 120 | 0.5 | 0.3 |

Table A2.

Road segment feature data.

Table A2.

Road segment feature data.

| Road Segment | Lengths (km) | Road Class | Free-Flow Speeds (km/h) | Morning Peak (7–9) | Morning (9–12) | Noon (12–14) | Afternoon (14–17) | Evening Peak (17–19) | Evening (19–23) | Other Time Periods |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1–2 | 2.8 | I | 90 | 1.0 | 0.3 | 0.8 | 0.6 | 1.2 | 0.4 | 0.3 |

| 1–12 | 4.1 | I | 100 | 0.9 | 0.3 | 0.7 | 0.5 | 1.1 | 0.3 | 0.2 |

| 1–14 | 3.6 | II | 50 | 1.1 | 0.5 | 0.9 | 0.7 | 1.3 | 0.5 | 0.4 |

| 2–3 | 5.1 | I | 90 | 0.9 | 0.3 | 0.7 | 0.5 | 1.1 | 0.3 | 0.2 |

| 2–15 | 2.9 | II | 60 | 1.2 | 0.6 | 1.0 | 0.8 | 1.4 | 0.6 | 0.4 |

| 3–4 | 3.4 | I | 85 | 1.0 | 0.3 | 0.8 | 0.6 | 1.2 | 0.4 | 0.3 |

| 4–5 | 2.5 | I | 90 | 1.2 | 0.6 | 1.0 | 0.8 | 1.4 | 0.6 | 0.4 |

| 4–18 | 2.5 | II | 55 | 1.0 | 0.3 | 0.8 | 0.6 | 1.2 | 0.4 | 0.3 |

| 5–6 | 2.6 | I | 90 | 1.1 | 0.6 | 1.0 | 0.8 | 1.3 | 0.6 | 0.4 |

| 5–19 | 2.7 | I | 80 | 1.0 | 0.3 | 0.8 | 0.6 | 1.2 | 0.4 | 0.3 |

| 6–7 | 1.5 | I | 90 | 1.2 | 0.6 | 1.0 | 0.8 | 1.4 | 0.6 | 0.4 |

| 6–20 | 1.6 | II | 50 | 1.1 | 0.3 | 0.9 | 0.6 | 1.3 | 0.4 | 0.3 |

| 7–8 | 1.6 | I | 90 | 1.1 | 0.5 | 0.9 | 0.7 | 1.3 | 0.5 | 0.4 |

| 7–21 | 1.4 | I | 90 | 0.9 | 0.3 | 0.7 | 0.5 | 1.1 | 0.3 | 0.2 |

| 8–9 | 2.3 | I | 80 | 1.0 | 0.3 | 0.8 | 0.6 | 1.2 | 0.4 | 0.3 |

| 8–22 | 2.4 | II | 60 | 1.1 | 0.5 | 0.9 | 0.7 | 1.3 | 0.5 | 0.4 |

| 9–10 | 2.1 | I | 90 | 1.0 | 0.3 | 0.8 | 0.6 | 1.2 | 0.4 | 0.3 |

| 9–23 | 1.7 | II | 60 | 1.1 | 0.5 | 0.9 | 0.7 | 1.3 | 0.5 | 0.4 |

| 10–11 | 2.2 | I | 90 | 1.0 | 0.3 | 0.8 | 0.6 | 1.2 | 0.4 | 0.3 |

| 10–24 | 1.2 | II | 50 | 1.2 | 0.6 | 1.0 | 0.8 | 1.4 | 0.6 | 0.4 |

| 11–12 | 3.2 | I | 85 | 1.2 | 0.6 | 1.0 | 0.8 | 1.4 | 0.6 | 0.4 |

| 11–13 | 2.7 | II | 55 | 1.0 | 0.4 | 0.8 | 0.6 | 1.2 | 0.5 | 0.4 |

| 11–24 | 1.4 | II | 50 | 1.1 | 0.5 | 0.9 | 0.7 | 1.3 | 0.5 | 0.4 |

| 12–13 | 1.6 | I | 70 | 1.1 | 0.5 | 0.9 | 0.7 | 1.3 | 0.5 | 0.4 |

| 13–14 | 3.3 | I | 70 | 1.1 | 0.5 | 0.9 | 0.7 | 1.3 | 0.5 | 0.4 |

| 13–25 | 1.0 | II | 60 | 1.1 | 0.5 | 0.9 | 0.7 | 1.3 | 0.5 | 0.4 |

| 14–15 | 3.4 | II | 60 | 1.0 | 0.4 | 0.8 | 0.6 | 1.2 | 0.5 | 0.4 |

| 14–30 | 2.4 | III | 40 | 1.2 | 0.6 | 1.1 | 0.8 | 1.4 | 0.7 | 0.4 |

| 15–16 | 2.5 | II | 50 | 1.0 | 0.5 | 0.9 | 0.7 | 1.3 | 0.5 | 0.4 |

| 15–29 | 2.3 | III | 40 | 1.2 | 0.6 | 1.1 | 0.8 | 1.4 | 0.7 | 0.4 |

| 16–17 | 1.9 | III | 40 | 1.3 | 0.7 | 1.2 | 0.8 | 1.5 | 0.8 | 0.4 |

| 17–18 | 1.7 | II | 60 | 1.1 | 0.5 | 0.9 | 0.7 | 1.3 | 0.5 | 0.4 |

| 17–29 | 1.5 | III | 40 | 1.3 | 0.7 | 1.0 | 0.9 | 1.5 | 0.8 | 0.4 |

| 18–19 | 2.5 | II | 50 | 1.0 | 0.3 | 0.8 | 0.6 | 1.2 | 0.5 | 0.3 |

| 19–20 | 1.4 | II | 60 | 1.0 | 0.5 | 1.0 | 0.7 | 1.3 | 0.5 | 0.4 |

| 19–28 | 2.3 | III | 30 | 1.2 | 0.7 | 1.1 | 0.9 | 1.5 | 0.9 | 0.4 |

| 20–21 | 2.1 | II | 55 | 1.1 | 0.3 | 0.9 | 0.6 | 1.4 | 0.4 | 0.3 |

| 20–27 | 2.3 | III | 40 | 1.4 | 0.7 | 1.1 | 0.8 | 1.6 | 0.8 | 0.5 |

| 21–22 | 1.6 | II | 50 | 1.0 | 0.5 | 0.9 | 0.7 | 1.3 | 0.4 | 0.4 |

| 22–23 | 2.9 | II | 50 | 1.1 | 0.4 | 0.8 | 0.6 | 1.2 | 0.5 | 0.4 |

| 22–27 | 2.8 | III | 40 | 1.4 | 0.7 | 1.2 | 0.9 | 1.7 | 0.9 | 0.5 |

| 23–24 | 2.6 | II | 50 | 1.1 | 0.4 | 0.9 | 0.6 | 1.2 | 0.5 | 0.4 |

| 23–26 | 2.1 | III | 40 | 1.3 | 0.7 | 1.0 | 0.8 | 1.5 | 0.7 | 0.4 |

| 24–25 | 1.8 | III | 30 | 1.2 | 0.6 | 1.1 | 0.8 | 1.5 | 0.8 | 0.3 |

| 25–26 | 2.4 | II | 50 | 1.0 | 0.6 | 0.9 | 0.8 | 1.3 | 0.5 | 0.4 |

| 25–30 | 3.0 | II | 50 | 1.0 | 0.3 | 0.8 | 0.7 | 1.2 | 0.4 | 0.3 |

| 26–27 | 2.5 | II | 50 | 1.1 | 0.5 | 0.8 | 0.6 | 1.4 | 0.5 | 0.4 |

| 27–28 | 2.2 | II | 50 | 1.1 | 0.3 | 0.9 | 0.7 | 1.2 | 0.4 | 0.3 |

| 28–29 | 2.0 | III | 30 | 1.2 | 0.6 | 1.1 | 0.8 | 1.4 | 0.7 | 0.5 |

| 28–30 | 1.5 | II | 50 | 1.0 | 0.5 | 0.9 | 0.7 | 1.3 | 0.6 | 0.4 |

Table A3.

PDOSE.

Table A3.

PDOSE.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | II | III | I | II | III | I | II | III | I | II | III | ||

| 1 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.1 | 0.04 | 0.06 | 0.1 | 0.08 | 0.09 | 0.1 | 0.08 | 0.05 | |

| 2 | 0.15 | 0.09 | 0.07 | 0.02 | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.02 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.07 | 0.07 | |

| 3 | 0.2 | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.06 | |

| 4 | 0.1 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.01 | 0.08 | 0.07 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.07 | |

References

- Yang, J.; Dong, J.; Hu, L. A data-driven optimization-based approach for siting and sizing of electric taxi charging stations. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2017, 77, 462–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wang, Z.; Miller, E.J.; Cui, D.; Liu, P.; Zhang, Z. Charging demand prediction in Beijing based on real-world electric vehicle data. J. Energy Storage 2023, 57, 106294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Xiao, Z.; Zhao, P.; Iyengar, A. An Empirical Study of Travel Behavior Using Private Car Trajectory Data. IEEE Trans. Netw. Sci. Eng. 2021, 8, 53–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, D.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, L.; Chen, F.; Peng, Z.-R. Urban travel behavior analyses and route prediction based on floating car data. Transp. Lett. 2014, 6, 118–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mocanu, T. What Types of Cars Will We Be Driving? Methods of Forecasting Car Travel Demand by Vehicle Type. Transp. Res. Rec. 2018, 2672, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; He, J.; Liu, Z.; Xing, L.; Wang, Y. Travel demand and distance analysis for free-floating car sharing based on deep learning method. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0223973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Q.; Tong, X.; Huang, Y.; Li, J.; Xiong, G. IMOCS Based EV Charging Station Planning Optimization Considering Stakeholders’ Interests Balance. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 52102–52115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, M.M.; El-Tazi, N.; Moawad, R.; Eissa, A.H.B. TSB-Forecast: A Short-Term Load Forecasting Model in Smart Cities for Integrating Time Series Embeddings and Large Language Models. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 141694–141716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Xu, S.; Song, Y.; Qi, W.; Guo, Q.; Li, X.; Kong, L.; Chen, J. Real-Time Global Optimal Energy Management Strategy for Connected PHEVs Based on Traffic Flow Information. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2024, 25, 20032–20042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsiotas, D.; Polyzos, S. The topology of urban road networks and its role to urban mobility. Transp. Res. Procedia 2017, 24, 482–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Mao, Y.; Li, J.; Xiong, Z.; Wang, W.-X. Predictability of Road Traffic and Congestion in Urban Areas. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0121825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isradi, M.; Dwiatmoko, H.; Setiawan, M.; Supriyatno, D. Analysis of Capacity, Speed, and Degree of Saturation of Intersections and Roads. J. Appl. Sci. Eng. Technol. Educ. 2020, 2, 150–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, N.; Zhao, S.-c. Urban Road Traffic Impedance Function—Dalian City Case Study. J. Highw. Transp. Res. Dev. (Engl. Ed.) 2014, 8, 90–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Song, Z.; Chen, R. Energy consumption prediction of PEVs incorporating traffic flow information. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 22602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Q.; Fu, J.; Yu, Y.; Tang, X. Identification of urban regions’ functions in Chengdu, China, based on vehicle trajectory data. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0215656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bifulco, G.N.; Cartenì, A.; Papola, A. An activity-based approach for complex travel behaviour modelling. Eur. Transp. Res. Rev. 2010, 2, 209–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauke, H.; Mertens, S. Random numbers for large-scale distributed Monte Carlo simulations. Phys. Rev. E 2007, 75, 066701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bin Ahmad, M.S.; Pesyridis, A.; Sphicas, P.; Mahmoudzadeh Andwari, A.; Gharehghani, A.; Vaglieco, B.M. Electric Vehicle Modelling for Future Technology and Market Penetration Analysis. Front. Mech. Eng. 2022, 8, 896547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, F.; Dong, H. Targeted optimal-path problem for electric vehicles with connected charging stations. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0220361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostic, B.; Gentile, G. Using traffic data of various types in the estimation of dynamic O-D matrices. In Proceedings of the 2015 International Conference on Models and Technologies for Intelligent Transportation Systems (MT-ITS), Budapest, Hungary, 3–5 June 2015; pp. 66–73. [Google Scholar]

- Souza, G.G.d.; Santos, R.R.d.; Godoy, R.B. Optimizing power grids: A valley-filling heuristic for energy-efficient electric vehicle charging. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0316677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, L.; He, J.; Zhu, L.; Huang, W.; Wang, Y.; Yu, H. Comprehensive evaluation of electric vehicle charging network under the coupling of traffic network and power grid. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0275231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Z.; Li, J.; Zhang, X.P.; Zhang, R. Review on Optimization of Forecasting and Coordination Strategies for Electric Vehicle Charging. J. Mod. Power Syst. Clean Energy 2023, 11, 389–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nespoli, A.; Ogliari, E.; Leva, S. User Behavior Clustering Based Method for EV Charging Forecast. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 6273–6283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Zhu, C.; Liang, Q.; Jiang, N.; Luo, S.; Wu, Q. A step-by-step load forecasting method considering electric vehicle charging stations. In Proceedings of the 2024 3rd International Conference on Energy, Power and Electrical Technology (ICEPET), Chengdu, China, 17–19 May 2024; pp. 1325–1329. [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, J.; Lei, X.; Shao, Z.; Jian, L. A Reliable Evaluation Metric for Electrical Load Forecasts in V2G Scheduling Considering Statistical Features of EV Charging. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2024, 15, 4917–4931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, S.; Wei, Z.; Shang, D.; Zhao, Z.; Chen, H. Charging Load Prediction and Distribution Network Reliability Evaluation Considering Electric Vehicles’ Spatial-Temporal Transfer Randomness. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 124084–124096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, S.; Zhang, H.; Yang, Y.; Li, B.; Su, S.; Huang, S.; Zheng, G. Spatial-temporal Dynamic Forecasting of EVs Charging Load Based on DCC-2D. Chin. J. Electr. Eng. 2022, 8, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Cong, P.; Wang, Y. Charging Load Forecasting of Electric Vehicles Based on VMD–SSA–SVR. IEEE Trans. Transp. Electrif. 2024, 10, 3349–3362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Dou, C.; Hancke, G.P.; Yue, D.; Wei, X.; Zhang, B.; Xu, L.; Yan, T. Prediction of Charging Station Load Uncertainty Based on Multi-Dimensional Quantile Spatial-Temporal Traffic Flow Forecast. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2025, 16, 5324–5339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, R.; Wang, J.; Sun, Z.; Wu, J.; Lu, X.; Chang, L. Multi-Scale Spatial-Temporal Graph Attention Network for Charging Station Load Prediction. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 29000–29017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).