Abstract

An elevated somatic cell count (SCC) affects the physicochemical characteristics of milk, altering its renneting ability and ultimately impacting the yield and quality of the cheese produced. This study aims to analyse the variations in the composition of Latvian goat milk and its technological properties in relation to SCC. Individual goat milk samples (n = 240) were collected from one of the largest goat farms in Latvia during 2019 and 2020. Latvian, Saanen, and cross-breed goat milk samples from different lactations were tested for their chemical composition (fat, protein, lactose, dry matter, and SCC), fat-to-protein ratio, freezing point, and curd firmness. Samples were collected during different lactation periods in order to analyse the seasonal effect on milk quality. The results demonstrated that milk samples from goats with lower SCCs (Group I) exhibited the highest fat (3.34%), lactose (4.56%), and dry matter (11.28%) concentrations and fat-to-protein ratios (1.02). Curd firmness decreased progressively from Group I to Group IV, fluctuating between Latvian Native (1.96–1.47 N), Saanen (1.91–1.59 N), and cross-breed (1.66–1.58 N) goat milk samples. A significantly lower (p = 0.030) curd firmness (1.56 N) was determined in the Group IV goat milk samples. Seasonal fluctuations in milk composition were observed in relation to curd firmness, which peaked in late lactation milk (3.85 N), although minor fluctuations were observed in protein concentrations (3.23% to 3.30%) across the sampling periods (2019 and 2020). These findings highlight the necessity of SCC monitoring in Latvian goat milk to ensure appropriate quality for milk processing.

1. Introduction

The somatic cell count serves as a key indicator of udder health, reflecting the presence of leucocytes and epithelial cells in milk [1,2,3]. Study findings demonstrate a high SCC in goat [4,5,6,7] and sheep [8] milk. Physiological factors, such as the apocrine secretion mechanism, can cause inherently higher SCC in goats, thus complicating the diagnosis of subclinical mastitis [6,7]. Goat milk is a rich source of essential nutrients, providing significant amounts of fat, protein, lactose, and salts for nutrition [9]. Its composition can be influenced by factors such as breed, lactation, age, and parity [3,10,11,12,13], as well as climate, season, farm management, milking system, and feed [14,15,16,17]. The oestrus cycle and stress [18] also impact the composition of milk and its suitability for processing.

In healthy goat mammary glands, epithelial cells and leucocytes are the predominant somatic cell types. The former are derived from the mammary gland itself, while the latter come from the bloodstream [6,11]. The SCC is a principal indicator associated with intramammary infection (mastitis) in cows; however, in goats, the SCC is obscured by non-infectious factors, including milk secretion process and physiological changes that occur during lactation [10,17]. A high SCC is not always a sign of mastitis due to significant differences among individual goats [10]. Recent studies showed that 53.5% of SCC fluctuations in goat milk can be connected to seasonality and the herd lactation stage [17]. An increased somatic cell count (over 1 × 106 cells per ml) is associated with changes in milk’s chemical composition [5,19,20], especially reductions in lactose, fat, and casein concentrations. Therefore, SCC monitoring is crucial not only for goat health but also from a milk-processing perspective, to analyse milk suitability and product properties. Milk processing modifies its physicochemical properties, including mineral equilibrium, whey protein denaturation, and protein–protein interactions, all of which can significantly influence its functional attributes [21].

In Latvia, no limitations have been established for the SCC in raw goat milk; it is set at 400,000 cells per ml for bovine milk [22]. To date, no studies have analysed the somatic cell count in connection with milk composition and quality changes or its influence on milk processing and milk product properties.

Cheese is one of the main dairy products produced from goat milk in Latvia, but cheese properties and quality indices have not been analysed in relation to SCC or induced variations in SCC. Goat milk suitability has been analysed via coagulation kinetics, and the firmness of the curd developed [19]; the most commonly measured coagulation properties are renneting time, curd firmness, and gel strength [23,24]. Various methods are used to determine curd firmness. In the literature, milk coagulation properties are typically evaluated by the rennet coagulation time (RCT), time for curd firming to a specified firmness (k20), and curd firmness measured 30 min after rennet addition (a30) [13,19,24]. The curd firmness, which is strongly influenced by variations in fat and protein concentration, as well as in SCC, can be measured in Newtons (N), which provides a direct estimation of milk’s suitability for cheese production [19,25,26,27]. An elevated SCC (~1 × 106 cells per mL) reduces casein and whey protein stability and impairs micellar aggregation, prolonging renneting time and weakening gel strength across ruminants [19,28,29,30,31].

The aim of the current study was to analyse the variations in Latvian goat milk composition and technological properties in relation to somatic cell count.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Farm Characteristics

Individual goat milk samples were collected from a goat farm located in Latvia (Jelgava district), which maintained a herd of 146 goats, including 100 milking does and three bucks. In total, 240 individual milk samples were collected during 2019 and 2020, representing Latvian Native (n = 60), Saanen (n = 70), and cross-bred (n = 110) goats. The pedigree contribution in the cross-bred goats was approximately 40% and 60% Latvian Native and Anglo Nubian lines, respectively. The animals selected for the study were goats in the 2nd (n = 85), 3rd (n = 112), and 4th (n = 43) lactation stages. All animals received the same feed—hay (produced on the farm fields), carrots, and grain (oats or barley)—and from March to October, the goats were pastured. Salt licks (KNZ Basic; Akzo Nobelas, Hengelo, The Netherlands) and micro- and macro-elements (Minera Ecolick; Vilmox Baltic Ltd., Tukuma municipality, Latvia) were also available ad libitum. On average, per 50 kg of live goat weight, the goats consumed around 2.0 kg of dry matter, providing ~20 MJ of metabolisable energy and 250 g of crude protein. According to the author’s calculations, this was supplied by roughly 0.3 kg DM from hay, 1.5 kg DM from pasture herbage, and 0.2 kg DM from cereal grains.

In this study, the seasonal effect was analysed by collecting samples in spring, early and late summer and autumn. The collected samples were classified by the determined somatic cell count, categorised within groups, and the results were analysed within breeds and lactation stages.

2.2. Sample Collection

Prior to sample collection, the goat udders were cleaned and disinfected (Eimu Euterwasch, Dobrcz, Poland), and then foremilk was discharged and manually milked into a separate bucket from which the sample was taken. The goat milk samples were collected at morning milking in 50 mL plastic tubes, immediately cooled to 4 °C, and kept in the refrigerator at 4 °C until delivery to the laboratory. Sample collection and milk composition analyses were carried out on the same day.

2.3. Milk Proximate Composition Analyses

Fat, protein, lactose, dry matter, and freezing point were measured using MilkoScan MarsTM (Foss, Hillerød, Denmark), and the somatic cell count was determined using Fossomatic FC (Foss, Hillerød, Denmark).

SCC was transformed into standardised units—the somatic cell score (SCS)—using the following equation [32]:

SCS = log2(SCC/100,000) + 3,

Season was included as a factor in the analysed samples as they were taken in spring, early and late summer, and autumn.

2.4. Goat Groups

Goats were categorised based on the somatic cell counts determined from the milk samples and separated into four groups according to the studies of Desidera et al. (2025) and Tvarožková et al. (2023) [19,33]. The determined somatic cell count was converted into a somatic cell score. The different groups are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

The characteristics of goat groups.

2.5. Curd Firmness

Individual goat milk samples were heated up to 35 °C, and 1% (v/v) rennet (CHY-MAX Ultra 1000, Chr. Hansen, Hørsholm, Denmark) solution was added. Samples were continuously stirred for 30 s and incubated at 35 °C for 30 min in an incubator (MEMMERT IN55, Schwabach, Germany). Curd firmness was measured using a TA.HD.plus Texture Analyser (Stable Micro Systems, Godalming, UK) using an A/BE disc, 45 mm in diameter, with a testing speed of 1.0 mm s−1. The penetration depth into the sample was 8 mm s−1 [34,35]. The curd firmness (a30) was measured in Newtons (N), and measurements were made in triplicate.

2.6. Study Limitations

Analysing the late summer milk, it was found that four goat milk samples were characterised by low curd firmness (below 0.7 N), all representing the cross-breed group. This unusually low data could influence the average results; therefore, they were excluded from further analyses.

2.7. Data Analyses

Statistical analysis was conducted using descriptive statistics and ANOVA (MS Excel Office 2016). Mean comparisons of the parameters were performed using descriptive statistics and the paired two-sample t-test for means. Differences were considered significant at a confidence level of p > 0.05. Standard deviation was used to indicate the variability of the mean.

3. Results

Individual goat milk samples were collected to clarify milk composition and curd firmness data in relation to somatic cell count variations, and seasonal fluctuations were determined to establish a relationship between somatic cell and season (Table 2).

Table 2.

Goat milk composition and curd firmness depending on SCS.

Milk composition and coagulation characteristics were strongly affected by somatic cell count, and a higher SCS was associated with a decreased freezing point and dry matter concentration, as well as a lower protein content and curd firmness.

The highest fat concentration (3.34%) was established in Group I samples with an SCS < 5.32. The protein concentration varied between 3.20% and 3.32%, and no significant differences were found among groups. The freezing point exhibited minor variations amongst the studied groups, ranging from −0.477 to −0.491 °C. A higher fat-to-protein ratio was observed in Group I samples (1.02), while in the remainder of the groups, the value remained below 1.00. Stocco et al. (2018) found that the fat concentration is associated with improved coagulation properties, with a higher value associated with shorter rennet coagulation times and higher curd firmness at 30 min [31]. A high somatic cell count (Group IV—9.08) significantly reduces curd firmness (Table 2), considerably lowering the results by 14% to 17% (1.56 N) in comparison with Group III (1.88 N, p = 0.038), Group II (1.89 N; p = 0.026), and Group I (1.81 N; p = 0.042) samples. No significant differences were observed in lactose concentration (4.50–4.56%) between the groups, indicating there was no direct influence of increased SCC on this parameter in this study. Salomone-Caballero et al. (2024) also reported no significant association between SCC and lactose concentration in Canarian dairy goat milk [36], and Podhorecká and co-authors concluded that 1 × 106 SCC per ml does not affect lactose synthesis in goat secretory mammary epithelial cells [6].

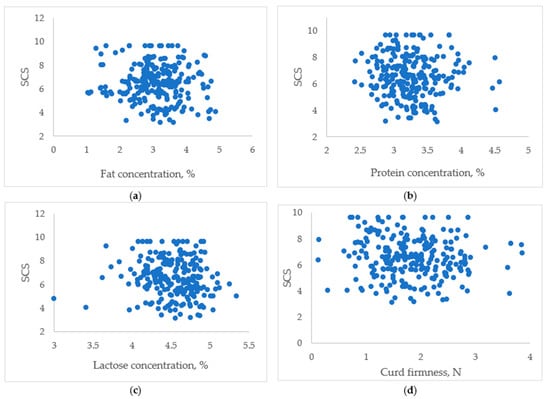

Principal correlation analysis was performed to investigate the impact of SCC on milk composition. No correlation was established between the SCS and curd firmness, but the SCS declines slightly as curd firmness increases. Figure 1 highlights the datasets with no associations between the studied variables.

Figure 1.

The associations between somatic cell score and goat milk fat (a), protein (b), lactose (c), and curd firmness (d).

The presented data support the statement that the SCC has a limited impact on milk composition. Curd firmness was affected by high SCCs (Group IV; Table 2), yet when all milk samples were analysed collectively, no strong relationship between these parameters was observed. Figure 1 provides valuable insights, showing that no established associations exist between the studied variables.

The seasonal variations in goat milk composition and quality are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Seasonal variations in goat milk composition and its influence on curd firmness data.

The protein concentration in goat milk exhibited only minor variations between seasons, ranging from 3.23% to 3.30%, with the highest protein concentration (3.30%) found in late summer milk samples. Comparable findings were reported by Scano and Caboni (2022), who measured the highest protein concentration in late-lactation (autumn) goat milk [30]. A lower dry matter concentration was observed in early (10.80%) and late (10.74%) lactation goat milk in summer, possibly reflecting the higher pasture quality in early and late summer. Freezing points remain within a relatively narrow physiological range and are related to the concentration of non-fat solids, particularly lactose [37]. In the current study, the freezing point varied from −0.500 to −0.469 °C, with a relatively high value in autumn (−0.469 °C), alongside the lowest dry matter (10.74%) and lactose (4.41%) concentrations.

The fat-to-protein ratio is an indicator that describes the suitability of milk for cheese production and predicts cheese outcomes; average values in goat milk typically range from 1.10 to 1.27 [30,38,39]. The results show that the lowest fat-to-protein ratio (0.83) was found in the spring, and the highest (1.02) was observed in the early summer samples.

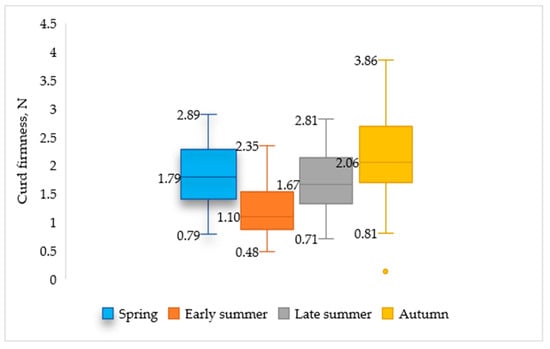

Seasonal differences were observed in the curd firmness of goat milk, with the lowest values in early summer milk (0.480 N) and the highest in samples collected in autumn (3.855 N) (Figure 2). Pazzola et al. (2022) concluded that milk samples collected during early lactation exhibited superior coagulation and curd firmness properties [16]. In the current study, contrary results were observed: the peak value was determined in late-lactation (autumn) milk samples. Additionally, our results demonstrate that curd firmness fluctuates seasonally, ranging from 1.84 N in spring to 2.12 N in autumn, although the lowest values were determined in late summer milk, falling to 1.61 N (Table 3). Desidera et al. (2025) come to similar conclusions, indicating reduced curd firmness during the warm season and improved curd firmness in the autumn [19]. Curd firmness fell to a minimum in early summer, coinciding with a decrease in protein concentration.

Figure 2.

Seasonal changes in goat milk curd firmness.

Breed is a recognised determinant of somatic cell counts in goats, and simultaneously has an effect on milk composition and yield [11,40]. In this study, animals were grouped based on SCC, and the influence of breed (Latvian Native, Saanen) and cross-breed was analysed within groups.

The protein concentration was 3.32% for Latvian Native and 3.28% for Saanen goat milk samples, representing the highest values for these breeds (Group 1). A comparable trend was noted for fat concentration, with the highest values in Group I samples: Latvian Native (3.07%), Saanen (3.33%), and cross-breed (3.5%). Significant differences were observed in fat concentration in Group II samples between Latvian Native and Saanen breeds (p = 0.004) and Latvian Native and cross-bred (p = 0.002) breeds. Neither the lactation stage (Table 4) nor breed significantly impacted the fat-to-protein ratio in goat milk (Table 3); an influence of breed was only observed in Group II’s results. There were no established relationships between lactation stages within the groups regarding fat concentration, but there were small differences in lactation between the groups (Figure 1 and Table 4). Comparatively, the curd firmness declined progressively between samples of Group I and Group IV: from 1.96 to 1.47 N for the Latvian Native breed, from 1.91 to 1.59 N for the Saanen breed, and from 1.66 to 1.58 N for the cross-breed.

Table 4.

Goat milk composition analysis based on somatic cell count and breed.

A higher protein concentration (3.53%) was determined in the second-lactation goat milk samples (Group III), and differences in protein concentration were observed between the second-lactation samples (3.35%) and the third- and fourth-lactation samples (3.17% and 3.27%, respectively) (Table 5). Differences were also observed in Group III and Group IV. Second-lactation goat milk samples often exhibit notable milk coagulation traits [31,39], but in the current study, a significant difference in protein concentrations was established between second- and third-lactation goat milk (p = 0.013) in all groups.

Table 5.

Goat milk composition analysis regarding somatic cell count and lactation.

The highest fat concentrations were found in Group I goat milk samples, ranging from 3.30% to 3.40%. Second-lactation milk in particular was characterised by the highest fat concentration (3.40%). There were no significant differences in fat concentration between lactation stages within groups, but a difference was found between Group I and Group II samples for the second and third lactations (p = 0.019 and 0.042). The fat-to-protein ratio ranged from 0.85 to 1.04; the highest results were observed in Group I (1.00 or above) samples. There were no significant differences between the groups for this parameter.

4. Discussion

Understanding the role of curd firmness in the production of goat milk cheese entails considering multiple interacting factors, including milk composition, processing parameters, goat genetics, and environmental influence. The complex interactions amongst these factors highlight the need for careful control and monitoring of milk quality throughout the processing chain, including cheese production [29,41].

This study provides insights into the relationships between SCC, milk composition, and curd firmness for the studied goat milk samples. When analysing SCC and curd firmness, we found no strong relationships between these parameters in goat milk (Table 1, Table 2, Table 3 and Table 4). Desidera et al. (2025) reported a negative association between SCC and the concentration of goat milk protein, but in our study, a correlation was not established [19]. Across the analysed samples, those with the highest SCC (Group IV) exhibited the weakest curd firmness (1.47 N), emphasising that a value of around 1 × 106 SCC per ml significantly prolongs the rennet coagulation time and reduces curd firmness strength [10,19,31]. Podhorecká et al. (2021) and Desidera et al. (2025) emphasised that increasing somatic cell counts influences milk coagulation properties, delaying rennet coagulation time and curd formation [6,19]. In line with the literature findings, the SCC has a marginal impact on curd firmness, although slight reductions were observed at higher SCCs [5,19]. The current study found no correlation between the SCC and curd firmness.

In goat production systems, the pasture season significantly influences SCCs in milk, typically increasing this value [17,42]. Prior studies on grazing systems have demonstrated that goat milk produced during the warm season exhibits lower concentrations of key components compared to milk obtained in the cold season; consequently, the protein concentration increased from 3.48% to 4.05% and the fat concentration from 4.92–4.98% to 6.75% [15]. Our results also revealed clear seasonal variations in curd firmness. Goat milk in the warm season had the least favourable properties: curd firmness was 1.230 N in early summer milk and 1.625 N in late summer milk compared to cold season values of 1.835 N in spring and 2.125 N in autumn. Researchers have documented that elevated SCCs in the warm season trigger epithelial proteases and activate the plasmin system, resulting in a reduction in curd firmness [19,36]. Pazzola et al. (2022) concluded that in the early stage of lactation, there were higher fat, protein, and lactose concentrations (4.75%, 3.80%, and 4.79%, respectively), and concentrations were lower in late lactation (3.98%, 3.43%, and 4.37%, respectively) [16]. The present study revealed that the lactose concentration was higher in early lactation, whereas fat and protein concentrations were higher in late lactation. Furthermore, in spring milk, the fat concentration was 2.69%, the protein concentration was 3.26%, and the lactose concentration was 4.59%; however, in autumn these values were 3.07%, 3.29% and 4.41%, respectively. Researchers in Sardinia reported data on bulk goat milk in late lactation, showing that SCC substantially influences cheese production, delays the RCT, and weakens curd firmness, as analysed through a30 values [16].

Goat milk compositions vary across breeds, with each breed displaying its own characteristic coagulation performance and suitability for cheese production [39]. The influence of fat concentration demands a more nuanced interpretation; specifically, the scientific literature indicates that a high fat concentration can enhance milk’s coagulation properties, reflected by a shortened RCT, a reduced curd firming rate, and a higher curd firmness at 30 min [19,31]. In our study, the fat concentration was the highest in Group I samples (3.34%); in subsequent breed (Latvian Native—3.07%, Saanen—3.33%, and cross-breed—3.50%) and lactation number (2nd—3.40%, 3rd—3.30%, and 4th—3.34%) analyses, Group I samples still had the highest fat concentrations. Saanen goats are characterised by higher milk yield and, consequently, higher fat and protein concentrations [24,30,43] in milk; however, at the same time, local breeds can exhibit higher solid levels in milk and, correspondingly, higher curd firmness [16,44]. In this study, goat milk from the Latvian Native breed was characterised by a lower fat-to-protein ratio (Group I—0.92; Group II—0.86; Group III—0.91), except in Group IV, where the ratio was similar for all breeds (0.95). Pazzola et al. (2018) concluded that, after including milk composition, lactation stage, and farming system in their model, small differences were found between breeds [24]; therefore, in our study, lactation and breed were treated as influencing factors for curd firmness. In the current study, the cross-breed animals carried Latvian Native and Anglo Nubian ancestry. Anglo Nubian milk is associated with higher fat and protein concentrations [35], which explains why, within the SCC groups, the highest fat and protein concentration values were mostly found for cross-breed goats (Table 3). The fat concentration in cross-breed milk (Group I) was 3.50%, and the protein concentration was 3.27%. Goat milk from the Saanen breed exhibited fat and protein concentrations of 3.33% and 3.28%, respectively. Nicovery et al. (2023) reported that the Anglo Nubian breed exhibits higher fat and protein concentrations; the present results are consistent with this observation [45]. The average milk composition for Anglo Nubian goats was 5.10% fat and 4.18% protein, higher compared to Saanen goat milk, where the composition of fat and protein was 3.66% and 3.32%, respectively [46].

The SCC tends to increase with lactation stage in dairy goats, reflecting the changes in udder tissue and the greater susceptibility to intramammary challenges in does, underscoring the need to adjust for parity when interpreting milk quality and coagulation outcomes [17,36].

The lactation number is an important factor in evaluating goat milk composition, although parity is also linked to variations in milk composition and the dynamics of somatic cell counts. Goat milk samples from the second-lactation stage were characterised by a shorter RCT and higher curd firmness [24,39]. The SCC increases with lactation stage, which further prolongs the coagulation time and decreases curd strength [36]. With progression to later lactation stages, alterations in milk composition, such as in fat, protein, and lactose concentrations, are observed, which subsequently affect milk coagulation properties [41]. Marcinkoniene and Ciprovica (2020) reported average curd firmness values of 1.84 N for the second-lactation goat milk, which decreased to 1.55 N for the third-lactation and further to 1.47 N in the fourth-lactation group [35]. Although the fat concentration is higher in goat milk during the later stages of lactation, the rennet coagulation time is longer, and the curd firmness is less stable. This confirms and highlights the role of various factors in milk coagulation properties.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that the somatic cell count impacts goat milk composition and curd firmness, with higher SCC associated with reduced protein and dry matter concentrations, a higher freezing point, and lower curd firmness, parameters critical for cheese production. The lactation and breed do not significantly affect the fat-to-protein ratio in goat milk, except for Group II in breed characterisation. Across breeds, the curd firmness declined from Group 1 to Group 4 (from 1.96 N to 1.47 N, respectively), and no consistent relationships were found between fat concentration and SCCs in the analysed samples. In the present study, curd firmness also varied seasonally, ranging from 1.84 N in early lactation to 2.12 N in late lactation, although the lowest values were observed in summer goat milk (1.61 N). Maintaining low SCC levels and monitoring seasonal variations in goat milk composition can directly enhance cheese production and product quality in the dairy sector. The current study reveals that to ensure an appropriate raw goat milk quality for processing, Latvian goat producers should monitor somatic cell counts.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, L.M. and I.C.; methodology, L.M. and I.C.; writing—original draft preparation, L.M. and I.C.; writing—review and editing, L.M. and I.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The study was supported by the project “Strengthening Research Capacity in the Latvia University of Life Sciences and Technologies”, contract No. 3.2.-10/2019/LLU/139 and “Strengthening the Institutional Capacity of LBTU for Excellence in Studies and Research,” funded by the Recovery and Resilience Facility, contract No. 3.2.-10/253 (AF29).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| SCC | Somatic cell count |

| SCS | Somatic cell score |

| a30 | Curd firmness measured 30 min after rennet addition |

| k20 | Curd firming time to specified firmness |

| N | Newtons |

| RCT | Rennet coagulation time |

References

- Alhussien, M.N.; Dang, A.K. Milk somatic cells, factors influencing their release, future prospects, and practical utility in dairy animals: An overview. Vet. World 2018, 11, 562–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smistad, M.; Sølverød, L.; Inglingstad, R.A.; Østerås, O. Distribution of somatic cell count and udder pathogens in Norwegian dairy goats. J. Dairy Sci. 2021, 104, 11878–11888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stocco, G.; Dadousis, C.; Vacca, G.M.; Pazzola, M.; Summer, A.; Dettori, M.L.; Cipolat-Gotet, C. Predictive formulas for different measures of cheese yield using milk composition from individual goat samples. J. Dairy Sci. 2022, 105, 5610–5621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, S.; Mora Garcίa, M.B. A 100-Year Review: Advances in goat milk research. J. Dairy Sci. 2017, 100, 10026–10044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leitner, G.; Lavon, Y.; Matzrafi, Z.; Benun, O.; Bezman, D.; Merin, U. Somatic cell counts, chemical composition and coagulation properties of goat and sheep bulk tank milk. Int. Dairy J. 2016, 58, 9–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podhorecká, K.; Borková, M.; Šulc, M.; Seydlová, R.; Dragounová, H.; Švejcarová, M.; Peroutková, J.; Elich, O. Somatic Cell Count in Goat Milk: An Indirect Quality Indicator. Foods 2021, 10, 1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupp, R.; Huau, C.; Caillat, H.; Fassier, T.; Bouvier, F.; Pampouille, E.; Clément, V.; Palhière, I.; Larroque, H.; Tosser-Klopp, G.; et al. Divergent selection on milk somatic cell count in goats improves udder health and milk quality with on nematode resistance. J. Dairy Sci. 2018, 102, 5242–5253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marshall, A.C.; Vigalo, V.; De Marchi, M.; Lopez-Villalobos, N.; Loveday, S.M.; Weeks, M.; McNabb, W. Effect of protein polymorphisms on milk composition, coagulation properties, and protein profile in dairy sheep. Int. Dairy J. 2025, 160, 106102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Prendes, R.; Crooijmans, R.P.M.A.; Dibbits, B.; Laport, K.; Breunig, S.; Keijzer, P.; Pellis, L.; Bovenhulis, H. Genetic and environmental factors shaping goat milk oligosaccharide composition. J. Dairy Sci. 2024, 107, 11214–11223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desidera, F.; Skeie, S.B.; Devold, T.G.; Inglingstad, R.A.; Porcellato, D. Fluctuations in somatic cell count and their impact on individual goat milk quality throughout lactation. J. Dairy Sci. 2024, 108, 152–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lianou, D.T.; Michael, C.K.; Vasileiou, N.G.C.; Liagka, D.V.; Mavrogianni, V.S.; Caroprese, M.; Fthenakis, G.C. Association of Breed of Sheep or Goats with Somatic Cell Counts and Total Bacterial Counts of Bulk-Tank Milk. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 7356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, W.D., Jr.; Marinho do Monte, D.F.; Gomes Cardoso de Leon, C.M.; Paulino de Moura, J.F.; Vieira da Silva, N.M.; Ramos do Egypto Queiroga, R.d.C.; Neto, S.G.; Naves Givisiez, P.E.; Pereira, W.E.; Bruno de Oliveira, C.J. Logistic regression model reveals major factors associated with total bacteria ans somatic cell counts in goat bulk milk. Small Rumin. Res. 2021, 198, 106360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stocco, G.; Dadousis, C.; Vacca, G.M.; Pazzola, M.; Paschino, P.; Dettori, M.L.; Ferragina, A.; Cipolat-Gotet, C. Breed of goat affects the prediction accuracy of milk coagulation properties using Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy. J. Dairy Sci. 2020, 104, 3956–3969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kotsiou, K.; Andreadis, M.; Manessis, G.; Lazaridou, A.; Biliaderis, C.G.; Basdagianni, Z.; Bossis, I.; Moschakis, T. Effects of farming system on rheological behaviour of rennet-induced coagulation in milk from Skopelos breed goats. Foods 2025, 14, 1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margatho, G.; Rodrίguez-Estévez, V.; Medeiros, L.; Simões, J. Seasonal variation of Serrana goat milk contents in mountain grazing system for cheese manufacture. Rev. Med. Vet. 2018, 169, 166–172. [Google Scholar]

- Pazzola, M.; Amalfitano, N.; Bittante, G.; Dettori, M.L.; Vacca, G.M. Composition, coagulation properties, and predicted cheesemaking traits of bulk milk from different farming systems, breeds, and stages of production. J. Dairy Sci. 2022, 105, 6724–6738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smistad, M.; Inglingstad, R.A.; Skeie, S. Seasonal dynamics of bulk milk somatic cell count in grazing Norwegian dairy goats. Short Communication. J. Dairy Sci. 2024, 5, 205–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehdid, A.; Martί-De Olives, A.; Fernández, N.; Rodrίguez, M.; Peris, C. Effect of stress on somatic cell count and milk yield and composition in goats. Res. Vet. Sci. 2019, 125, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desidera, F.; Skeie, S.B.; Devold, T.G.; Inglingstad, R.A.; Porcellato, D. Impact of somatic cell count and lactation stage on coagulation properties of milk from Norwegian individual goats. Int. Dairy J. 2025, 162, 106161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geus, Y.de.; Scherpenisse, P.; Smit, L.A.M.; Bossers, A.; Stegeman, J.A.; Benedictus, L.; Spieβ, L.; Koop, G. Total bacterial count and somatic cell count in bulk and individual goat milk around kidding: Two longitudinal observational studies. J. Dairy Sci. 2024, 107, 5427–5437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Delger, M.; Dave, A.; Singh, H.; Ye, A. Acid and rennet gelation properties of sheep, goat, and cow milks: Effects of processing and seasonal variation. J. Dairy Sci. 2022, 106, 1611–1625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regulation (EC) No 853/2004 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 29 April 2004 Laying down Specific Hygiene Rules for Food of Animal Origin; European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 2004.

- Cipolat-Gotet, C.; Cecchinato, A.; Malacarne, M.; Bittante, G.; Summer, A. Variations in milk protein fractions affect the efficiency of the cheese-making process. J. Dairy Sci. 2018, 101, 8788–8804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pazzola, M.; Stocco, G.; Paschino, P.; Dettori, M.L.; Cipolat-Gotet, C.; Bittante, G.; Vacca, G.M. Modeling of coagulation, curd firming, and syneresis of goat milk from 6 breeds. J. Dairy Sci. 2018, 101, 7027–7039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stocco, G.; Cipolat-Gotet, C.; Cecchinato, A.; Calamari, L.; Bittante, G. Milk skimming, heating, acidification, lysozyme, and rennet affect the pattern, repeatability, and predictability of milk coagulation properties and of curd-firming model parameters: A case study of Grana Padano. J. Dairy Sci. 2014, 98, 5052–5067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobbo, T.; Cipolat-Gotet, C.; Bittante, G.; Cecchinato, A. The nonlinear effect of somatic cell count on milk composition, coagulation properties, curd firmness modelling, cheese yield, and curd nutrient recovery. J. Dairy Sci. 2015, 99, 5104–5119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonfatti, V.; Ribeiro de Freitas, D.; Lugo, A.; Vicario, D.; Carnier, P. Effects of the detailed protein composition of milk on curd yield and composition measured by model micro-cheese curd making of individual milk samples. J. Dairy Sci. 2018, 102, 7863–7873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breunig, S.; Crooijmans, R.P.M.A.; Bovenhuis, H.; Hettinga, K.; Bijl, E. Linking variation in the casein fraction and salt composition to casein micelle size in milk of Dutch dairy goats. J. Dairy Sci. 2024, 107, 6474–6486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dadousis, C.; Cipolat-Gotet, C.; Stocco, G.; Ferragina, A.; Dettori, M.L.; Pazzola, M.; Rangel, A.H.d.N.; Vacca, G.M. Goat farm variability affect milk Fourier-transform infrared spectra used for predicting coagulation properties. J. Dairy Sci. 2020, 104, 3927–3935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scano, P.; Caboni, P. Seasonal variation of milk composition of Sarda and Saanen dairy goats. Dairy 2022, 3, 528–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stocco, G.; Pazzola, M.; Dettori, M.L.; Paschino, P.; Bittante, G.; Vacca, G.M. Effect of composition on coagulation, curd firming, and syneresis of goat milk. J. Dairy Sci. 2018, 101, 9693–9702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schutz, M.M.; Hansen, L.B.; Steuernagel, G.R.; Reneau, J.K.; Kuck, A.L. Genetic parameters for somatic cells, protein, and fat in milk of Holsteins. J. Dairy Sci. 1990, 73, 494–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tvarožková, K.; Tančin, V.; Uhrinčat, M.; Oravcová, M.; Hleba, L.; Gancárová, B.; Mačuhová, L.; Ptáček, M.; Marnet, P.G. Pathogens in milk of goats and their relationship with somatic cell count. J. Dairy Res. 2023, 90, 173–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrovska, S.; Jonkus, D.; Zagorska, J.; Ciprovica, I. The influence of k-casein genotype on the coagulation properties of milk collected from the local Latvian cow breeds. Agr. Res. 2017, 15, 1411–1418. [Google Scholar]

- Marcinkoniene, L.; Ciprovica, I. The influence of milk quality and composition on goat milk suitability for cheese production. Agr. Res. 2020, 18, 1796–1803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salomone-Caballero, M.; Fresno, M.; Álvvarez, S.; Torres, A. Effects of parity and somatic cell count threshold on udder morphology, milk ability traits, and milk quality in Canarian goats. Animals 2024, 14, 1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kjajevis, N.V.; Tomasevic, I.B.; Miloradovic, Z.N.; Nedeljkovic, A.; Miocinovic, J.B.; Jovanovic, S.T. Seasonal variations of Saanen goat milk composition and the impact of climatic conditions. J. Food. Sci. Technol. 2018, 55, 299–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferro, M.M.; Tedeschi, L.O.; Atzori, A.S. The comparison of the lactation and milk yield and composition of selected breeds of sheep and goats. Transl. Anim. Sci. 2017, 1, 498–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vacca, M.G.; Stocco, G.; Dettori, L.M.; Pira, E.; Bittante, G.; Pazzola, M. Milk yield, quality, and coagulation properties of 6 breeds of goats: Environmental and individual variability. J. Dairy Sci. 2018, 101, 7236–7247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Šlyžius, E.; Anskienė, L.; Palubinskas, G.; Juozaitienė, V.; Šlyžienė, B.; Juodžentytė, R.; Laučienė, L. Associations between somatic cell count and milk fatty acid and amino acid profile in Alpine and Saanen goat breeds. Animals 2023, 13, 965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolenc, B.; Malovrh, Š.; Paveljšek, D.; Rozman, V.; Simčič, M.; Treven, P. Correlation of goat milk coagulation properties between dams and daughters. Int. Dairy J. 2023, 143, 105644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inglingstad, R.A.; Eknæs, M.; Brunborg, L.; Mestawet, T.; Devold, T.G.; Vegarud, G.E.; Skeie, S.B. Norwegian goat milk composition and cheese quality: The influence of lipid supplemented concentrate and lactation stage. Int. Dairy J. 2016, 56, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michlová, T.; Dragounová, H.; Seydlová, R.; Hejtmánková, A. The hygienic and nutritional quality of milk from Saanen goats bred in the Moravian-Silesian region. Agr. Res. 2016, 14, 1396–1406. [Google Scholar]

- Currò, S.; De Marchi, M.; Claps, S.; Salzano, A.; De Palo, P.; Manuelian, C.L.; Neglia, G. Differences in the detailed milk mineral composition of Italian local and Saanen goat breeds. Animals 2019, 9, 412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicovery, I.M.C.; Rodrigues, T.C.G.d.C.; Tosto, M.S.L.; Bittencourt, R.F.; Mariz, L.D.S.; Azevedo, J.A.G.; Pinto de Carvalho, G.G.; Santos, S.A. Nutritional attributes of goat milk obrained from Anglo Nubian, Moxoto, and Saanen breeds in different lactation phases. Int. Dairy J. 2023, 145, 105720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, T.C.G.d.C.; Nicovery, I.M.C.; Alba, H.D.R.; Carvalho, G.G.P.d.C.; Tosto, M.S.L.; Bittencourt, R.F.; Azevedo, J.A.G.; Mariz, L.D.S.; Santos, S.A. Lactation curve, milk composition and metabolic status of goats from different genetic groups under propical conditions. J. Livest. Sci. Teh. 2023, 11, 01–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.