Abstract

(1) Background: Climate change is a major threat to human health and new research is highlighting its effects on physical health. However, there is still little research on the psychological effects, particularly on young people, who seem to be disproportionately affected. (2) Objectives: In this context, we conducted a study focusing on the young adult population to identify psychosocial and behavioral factors that may modulate the intensity of this anxiety. (3) Method: A cross-sectional study by questionnaire was carried out on a sample of 369 young French adults. Data were analyzed via structural equation modelling. (4) Results: The main results suggest that: (1) CFC and information seeking predict climate anxiety, which in turn predicts the emotional consequences of exposure to information about the negative consequences of climate change; (2) information seeking moderates the effects of CFC on climate anxiety. (5) Conclusions: This study highlights both the role of temporal orientation and information seeking on the climate anxiety experienced by young adults. These results provide an interesting lever for health professionals to work with this population who may be more vulnerable to climate anxiety than others.

1. Introduction

Climate change is described as a “process that impacts humans and their ecosystems in a myriad of ways” [1] (p. 246): increased temperatures, extreme storms, increased drought, warming and rising sea levels, species extinction, food scarcity, poverty and population displacement, and increased health risks [2]. The World Health Organization (WHO) has identified climate change as the greatest threat to human health and predicts that it will cause an increase of 250,000 additional deaths per year between 2030 and 2050. [3]. In addition, by 2030, the WHO estimates that the costs of direct damage to health are between 2 and 4 billion dollars per year. Finally, in its latest report, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change Group 2 has again highlighted the impact of climate change on physical and mental health [4].

Negative health effects of climate change are well documented [5]: altered exposure to heat and cold, air pollution, pollen-related allergies, food scarcity, emerging infections, flooding, water-borne diseases, increased exposure to UV radiation, or difficulties in accessing health services and facilities, [6,7,8,9,10]. A 2019 report in The Lancet suggests that a child born today will experience a world 7.2° F warmer than the pre-industrial average [11]. Rising temperatures, intense precipitation, extreme weather events and rising sea levels have already led to increased population exposure to extreme heat, poor air quality, reduced food and water quality, changes in infectious agents and population displacement [12]. At the same time, global warming leads to an increase in heat-related and cardiopulmonary diseases, food-, water- and vector-borne diseases, and mental health effects [13].

Climate change impacts on physical health have received much attention in the literature, although it can be noted that the effects of climate change on mental health have often been overlooked [14]. Climate change is considered by most major organizations (e.g., WHO; IPCC; United Nations, etc.) to be the greatest threat to mental health in the next century, yet the study of its effects on mental health is an emerging field that would require more robust empirical studies [15].

1.1. Impact of Climate Change on Mental Health

A WHO survey of 95 countries on health and climate change in 2021 showed that only nine countries included mental health and psychosocial issues in their vulnerability and adaptation assessment documents for climate change and health [16]. However, the consequences on mental health are numerous: emotional suffering, suicidal behavior, feelings of loss, depression or anxiety (e.g., [17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24]). These negative emotional responses to climate change are often called “climate anxiety” or “eco-anxiety” and are receiving increasing attention in the media [25] and from health care personnel such as doctors, psychiatrists and psychologists [26] (Cunsolo et al., 2020). Specifically, climate anxiety is defined as “the distress caused by climate change where people are becoming anxious about their future” [27] (p. 1). For their part, Gousse-Lessard and Lebrun-Paré define it as ‘a state of psychological discomfort and sometimes physical of varying degrees, characterized by the apprehension of a more or less distant threat in the future and significantly associated with the ecological disaster, which is itself perceived as uncertain, difficult to predict and difficult to control’ [28] (p. 4).

The concept of climate anxiety, considered as a future-oriented emotion, finds similarities with general anxiety [29], defined by Grupe and Nitschke ‘as anticipatory affective, cognitive and behavioral changes in response to uncertainty about a potential future threat’ [30] (p. 486). Climate anxiety is generated by three types of causes: direct causes (e.g., trauma related to extreme weather events), indirect causes (e.g., perceived threat of future risks) and psychosocial causes (e.g., migration and conflict related to global warming) [31,32,33]. It can be understood through two sub-dimensions: cognitive-emotional impairments (CEI), i.e., rumination, difficulty sleeping or concentrating, and nightmares or crying and functional impairments (FI), i.e., such as a person’s incapacity to work or to socialize [29]. Other authors describe two distinct manifestations of climate anxiety disorders: a paralyzing facet, preventing the individual from managing his negative emotions, and a practical facet, which allows him to reevaluate situations thanks to information or to produce new behaviors (e.g., [34,35,36]). However, certain groups and populations seemed to be more vulnerable to this problem than others [37]. This is particularly the case for young people (e.g., [38,39]).

1.2. Climate Anxiety and Young Populations

A broad study published in The Lancet Planetary Health and conducted in 10 countries in 2021 [40] reported that young people are deeply affected by climate anxiety. This study examined the relationship between 10,000 young people aged from 16 to 25 years and the consequences of climate change. Findings showed that 83% of young people said they were at least moderately worried that climate change is threatening people and the planet (with 59% saying they were very worried). Furthermore, more than 50% of respondents expressed feelings of sadness, anxiety, anger, helplessness, hopelessness or guilt. Finally, almost half of the young people (45%) reported a significant number of negative thoughts and felt that this affected their daily functioning such as: eating, concentrating, working, going to school, sleeping, spending time in nature, playing, having fun or having social relationships. The survey also showed the young people’s uncertainty about the future of humanity and the planet: 83% considered that people have not taken care of the planet earth, 56% that humanity is doomed and 75% that the future is particularly frightening. Youth appeared particularly affected by psychological problems related to climate change. However, the impacts of climate change on the mental and psychological states of youth have received less attention from the scientific community [41]. Wu et al. pointed out that “few attempts have been made to investigate the short-term and long-term effects of climate anxiety on the mental health of youth” [42] (p. 435).

1.2.1. Youth Exposure to Climate Change Information as an Explanatory Factor for Climate Anxiety

Researchers are now attempting to identify factors that may explain the prevalence of climate anxiety in this population. One of the factors regularly mentioned to explain the high climate anxiety felt by youth would be their high exposure to these issues in the media [36]. Indeed, youth are often exposed (e.g., on social networks) to news, images, or even reports of environmental disasters that bear witness to the consequences of climate change [43]. Similarly, Ma et al. [44], reviewed 92 empirical studies and identified media exposure as a risk factor that should be considered when assessing youth climate anxiety. Crandon et al. [45] also proposed in their “socio-ecological framework of climate anxiety in children and adolescents” to take into account the impact of the media in the assessment of climate anxiety. Thus, more and more studies examined the impact of the media on the emotions felt by young people. Ortiz et al. [46], for example, showed that presenting children with media cues related to a disaster (i.e., a category 5 hurricane) resulted in significantly higher levels of state anxiety (i.e., the situational anxiety felt by an individual). More recently, a study conducted among students showed that exposure to Typhoon Hato-related content on social networks was associated with post-traumatic stress disorder [47]. Other authors have attempted to determine the role of the media in the psychological process leading to climate anxiety. Doherty and Clayton [31] considered that the media is one of the mediators of climate anxiety. Reser and Swim [48] assume that information seeking is a proactive and reactive behavioral response that allows the individual to adapt to the psychological impacts of climate change. Thus, while most authors agree that exposure to media information is a major factor of youth climate anxiety, few empirical studies examine the place of this factor of this form of anxiety.

1.2.2. Youth Temporal Orientation as an Explanatory Factor for Climate Anxiety

Another factor put forward to explain the prevalence of climate anxiety among youth is that they are, by virtue of their age, more concerned about climate change because they “will bear a disproportionate share of the burden of climate change” [49] (p. 3). Albert et al. [50] noted that the younger generation perceives climate change as an unavoidable threat, so they are increasingly pessimistic about the future [51]. Rickinson, in 2001 [52], already emphasized the need to take into account youth visions of the future to highlight environmental concerns. Indeed, for youth, climate change is an issue “closely connected with uncertainty about the future survival of our planet and therefore as evoking feelings of existential anxiety and hopelessness” [53] (p. 626). Indeed, it seems that young adults are likely to develop a particular relationship to time (past, present and future) when faced with the issue of climate change. The relationship to time, called temporal perspective, is defined by Lewin as the “totality of the individual’s view of his psychological future and psychological past existing at a given time” [54] (p. 75). The time perspective impacts individuals and their behaviors in the present, either because they are influenced by past experiences or because they base their behavior on future consequences [55]. Behavioral anticipation of future consequences or Consideration of Future Consequences (CFC) is defined as “the extent to which people consider the potential distant outcomes of their current behaviors and the extent to which they are influenced by these potential outcomes” [56] (p. 743). It describes the way individuals will act, either in terms of immediate and concrete concerns (i.e., immediate time orientation), or rather in terms of future and abstract concerns (i.e., future time orientation) [57]. The relationship to time has, for example, been shown links to be related to psychological health, environmental behavior and health behavior (e.g., [58,59]). Future time orientation can also affect present motivations and emotions [60,61]. Other researchers have found that the future dimension of the CFC predicted of environmental values and beliefs about global warming [62]. Carmi and Arnon [63] showed that future-oriented individuals are more likely to express concerns about the environment. Similarly, Milfont and colleagues [64] found in a meta-analysis that more future-oriented individuals were among the most environmentally engaged populations. Finally, in a recent study, Geiger et al. [65] investigated the importance of present or future time orientation on individuals’ climate commitment. The results indicated that age and climate commitment decrease together, when individuals see their actions as having consequences for the present but less for the future.

Both theoretical and empirical evidence suggests that repeated exposure (e.g., through information-seeking behaviors) to this type of information in the media increase young people’s awareness of the immediate and future consequences of climate change. Thus, the individual preference in terms of relationship to time (i.e., whether individuals act more according to immediate and concrete concerns or more according to future and abstract concerns) can explain the way in which young people will apprehend and manage the consequences of climate change. While temporal orientation and exposure to information about the negative consequences of climate change appear to be predominant factors of climate anxiety among youth, no study has yet examined the interdependence and influence of these variables on the expression of climate anxiety and its cognitive, emotional, and functional manifestations.

1.3. Current Research

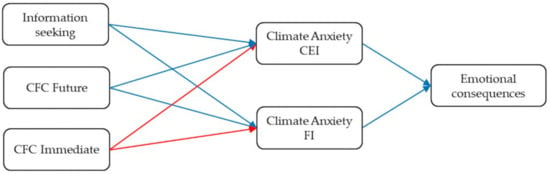

In this research perspective, a cross-sectional study involving young adults was conducted to examine the associations between considerations of future consequences (immediate or future) and information seeking on the two dimensions of climate anxiety (i.e., cognitive–emotional and functional impairments) and their emotional consequences on exposure to information about climate change consequences (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Theoretical model of the relationships between information seeking, consideration of future consequences, climate anxiety, and emotional consequences. Blue arrows represent positive relationships. Red arrows represent negative relationships.

To test this model, four specific hypotheses were formulated:

Hypothesis 1.

A “future” time orientation will be positively related to the two subdimension of climate anxiety (cognitive-emotional and functional impairments), whereas an “immediate” time orientation will be negatively related to climate anxiety.

Hypothesis 2.

A high propensity to seek information about climate change will be positively related to the different components of climate anxiety, whereas a low propensity to seek information about climate change will be negatively related to the different components of climate anxiety.

Hypothesis 3.

Participants with high levels of climate anxiety will have stronger emotional responses than other participants when exposed to information about climate change.

Hypothesis 4.

The effects of both dimensions of CFC (future and immediate) on the two dimensions of climate anxiety (CEI and FI) are moderated by information seeking. The more information-seeking participants are, the stronger the negative effects of CFC-I on both dimensions of climate anxiety and the stronger the positive effects of CFC-F on both dimensions of climate anxiety.

2. Materials and Methods

In order to test these different hypotheses, youth were asked to complete a questionnaire consisting of several measures: climate anxiety; considerations of future consequences; information seeking on climate change issues and emotional consequences of exposure to climate change information.

2.1. Participants and Procedure

Participants were recruited to participate in the study using age as an inclusion criterion. Indeed, we selected participants belonging to the ‘youth’ category, as was done in the study by Hickman et al. [40] and as proposed by Ojala and Lakew [66]. Thus, this study targeted the 18–26 age group to reach young people. In order to address this particular population, we conducted a survey on Limesurvey®. It was shared on the university’s networks and on the 3 largest social media platforms (Linkedin®; Facebook® and Twitter®). This allowed us to reach youth where they were, as these social media sites are frequently used by this population [67]. To ensure that individuals did not complete the survey multiple times, only one survey could be submitted from a particular IP address. This study is defined as non-interventional research and it complies with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Thus, after reading the information notice and completing the consent form, 369 participants completed the different questionnaire (Mage = 20.05, SDage = 2.00, 73.4% women).

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Climate Anxiety

Climate anxiety was measured using the Climate Change Anxiety Scale [29]. The 13-item scale validated in French in two-factor model cognitive-emotional impairments (climate anxiety-CEI dimension) and functional impairments (climate anxiety-FI dimension), was used for this study [68]. Participants answered these items using a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (Never) to 7 (Always). The theoretical model showed a good fit to the data: χ2 (64) = 155.14, p < 0.001, CFI = 0.92, TLI = 0.90, SRMR = 0.05, RMSEA = 0.06, 90% CI [0.05, 0.08]. For reliability, McDonald’s omega coefficients were calculated from a confirmatory factor analysis and were adequate, ω = 0.87 for the CEI subscale, and ω = 0.85 for the FI subscale (for details, see Supplementary Table S1).

2.2.2. Consideration of Future Consequences

The14-item Considerations of Futures Consequences (CFC-14) scale [57] was used in its French version [55] to assess individuals’ consideration of the immediate (CFC-I dimension, 6 items) and future (CFC-F dimension, 7 items) consequences of their actions on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (Does not fit me at all) to 7 (Fits me completely). The two-factor theoretical model showed a good fit to the data: χ2 (64) = 122.17, p < 0.001, CFI = 0.93, TLI = 0.91, SRMR = 0.05, RMSEA = 0.05, 90% CI [0.04, 0.06]. McDonald’s omega coefficients were calculated from a confirmatory factor analysis and were adequate at ω = 0.79 for the future subscale, and ω = 0.82 for the immediate subscale (Supplementary Table S1).

2.2.3. Information Seeking on Climate Change

In order to assess the extent to which the ‘young’ population seeks information on the issue of climate change, participants were asked to respond to the item “You seek information about climate change and its consequences (in the media, social networks…)” on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (Never) to 7 (Often).

2.2.4. Emotional Consequences of Exposure to Climate Change Information

Emotional consequences of participants’ exposure to climate change information were measured in a scenario task. The instructions were as follows: “Imagine the following situation: you watch a video or read a document/article about the effects of climate change (e.g., melting ice, pollution, forest fires, etc.). Below you will find a series of statements that people have used to describe themselves. Read each statement and check off what you feel in this situation.” Participants responded to the items using a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (Not at all) to 4 (A lot). The 7 statements proposed to the participants were based on the STAI-State items [69,70] (e.g., “I feel calm”, “I am worried”) with an adequate reliability (ω = 0.92) (Appendix A).

2.3. Data Analysis

The statistical analyses were conducted by using MPLUS software version 7.4 [71]. Main analyses were conducted with confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) and structural equation modeling (SEM). Several fit indices were used to evaluate model fits to the data [72]: Root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), standardized root mean square residual (SRMR), comparative fit index (CFI), and Tucker–Lewis index (TLI). Maximum likelihood robust (MLR) estimator was used to handle the somewhat non-normal data distributions (−0.37 < Skewness coefficients < 1.06; −1.03 < Kurtosis coefficients < 0.59; see Table 1). First, a confirmatory factorial analysis including substantive factors was performed to assess the factor structure of the latent variables and to compute correlations among latent factors. Then, structural equation modeling was used to examine relationships between latent factors and to test the theoretical model (Hypotheses 1 through 3). Finally, the latent interaction terms of the CFC-F dimension and information seeking on climate change, and the CFC-I and information seeking on climate change was constructed via Latent Moderated Structural Equations (LMS) method (Hypothesis 4; e.g., [73,74]). This method estimates the moderation effect from the latent product of the independent variable and the moderating variable [75]. Since the LMS method does not provide model fit indices generally used to interpret the fit of structural equation models (e.g., χ2, CFI, TLI, and RMSEA), Maslowsky and colleagues [73] recommendations were followed to assess the fit goodness of the moderated model. A log-likelihood ratio test (D) was performed to compare the relative fit of the model excluding the interaction terms (M0) and the model including the interaction terms (M1). A significant log-likelihood ratio test indicates that M0 represents a significant loss in fit relative to M1 (e.g., [73]).

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics.

3. Results

3.1. Preliminary Analyses

Table 1 shows descriptive statistics (mean, standard deviation, minimum and maximum values, skewness and kurtosis coefficients) for each variable. The CFA yielded a good fit to the data (χ2 (64) = 122.17, p < 0.001, CFI = 0.93, TLI = 0.91, SRMR = 0.05, RMSEA = 0.05, 90% CI [0.04, 0.06]) with six well-defined factors (|λ| = 0.46–0.83, M = 0.64; for details see Supplementary Table S1). Correlations between latent factors from the CFA showed that, as expected, the two dimensions of climate anxiety were strongly correlated with each other (r = 0.89, p < 0.001), and moderately correlated with information seeking on climate change and the emotional consequences to information on climate change (r = 0.52, p < 0.001 and r = 0.46, p < 0.001, respectively; see Supplementary Table S2). According to the literature, the two dimensions of the CFC were negatively related to each other (r = −0.65, p < 0.001). The Future dimension is positively correlated with climate anxiety-CEI (r = 0.38, p < 0.001), climate anxiety-FI (r = 0.37, p < 0.001), information seeking on climate change (r = 0.38, p < 0.001) and emotional consequences to information on climate change (r = 0.27, p < 0.001). Conversely, the CFC-I dimension was negatively associated with these variables (respectively, climate anxiety-CEI (r = −0.29, p < 0.001), climate anxiety-FI (r = −0.21, p < 0.001), information seeking on climate change (r = −0.15, p < 0.01) and emotional consequences to information on climate change (r = −0.21, p < 0.001; see Supplementary Table S2).

3.2. Main Analyses

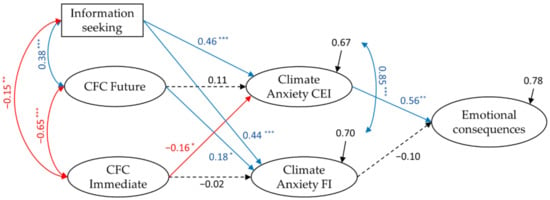

The structural equation model showed a good fit to the data (χ2 (516) = 887.39, p < 0.001, CFI = 0.92, TLI = 0.91, SRMR = 0.05, RMSEA = 0.04, 90% CI [0.04, 0.05]). Figure 2 presents the results of the structural equation modeling of the analysis model. Results indicated that the CFC-F dimension had a significant positive relationship with the climate anxiety-FI dimension (β = 0.18, p = 0.05) but did not have a significant relationship with the climate anxiety-CEI dimension. On the contrary, the CFC-I dimension had a significant negative relationship with the climate anxiety-CEI dimension (β = −0.16, p = 0.05) but was not significantly related to the climate anxiety-FI dimension. Hypothesis 1 was partially supported. Participants who scored high on the CFC-F dimension reported high levels of climate anxiety on the FI dimension and those who scored high on the CFC-I dimension reported low levels of climate anxiety on the CEI dimension. Information seeking on climate change had significant positive relationships with the climate anxiety-CEI dimension and climate anxiety-FI dimension (β = 0.46, p < 0.001, and β = 0.44, p < 0.001, respectively). Results support Hypothesis 2, young adults who seek information on climate change are those who reported the most anxiety related to climate change in the two dimensions assessed (CEI and FI). Overall, significant relationships contributed to explain 33% of the variance in the climate anxiety-CEI dimension and 30% of the variance in the climate anxiety-FI dimension. Finally, results indicated that climate anxiety-CEI dimension had a significant positive relationship with emotional consequences to information on climate change (β = 0.56, p = 0.003) explaining 22% of its variance. The climate anxiety-FI dimension was not significantly related with emotional consequences of climate change information. Hypothesis 3 was partially supported. Participants with high levels on the climate anxiety-CEI dimension reported higher levels of emotional reactions when they were exposed to climate change information compared to other participants. No difference was found for the climate anxiety-FI dimension.

Figure 2.

Standardized Estimates from Structural Equation Model. Latent factor indicators not shown for clarity. Blue arrows represent positive relationships. Red arrows represent negative relationships. Black dashed arrows represent non-significant relationships. * p < 0.05. ** p < 0.01. *** p < 0.001.

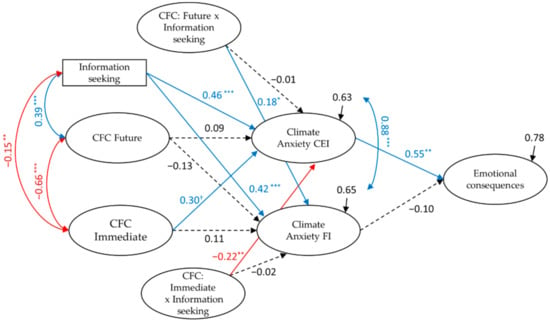

Regarding interaction of the CFC-F dimension and information seeking on climate change, and interaction of the CFC-I dimension and information seeking on climate change, the relative fit of the M1 model to M0 determined by a log-likelihood ratio test indicated that M0 represents a significant loss off fit compared with M1 (D = 21.17, free parameter difference = 4, χ2 (4) = 21.17, p < 0.001). The CFC-F Dimension × Information seeking interaction effect was significant on climate anxiety-FI dimension (β = 0.18, p = 0.03). This interaction effect was not significant on climate anxiety-CEI dimension (β = −0.01, p = 0.86). Conversely, the CFC-I dimension × Information seeking interaction effect was significant on climate anxiety-CEI dimension (β = −0.22, p = 0.01) but non-significant on climate anxiety-FI dimension (β = −0.02, p = 0.76). Hypothesis 4 was partially supported. The more information on climate change young adults seeks, the more the CFC-F dimension arouses the climate anxiety-FI dimension and the less the CFC-I dimension arouses the climate anxiety-CEI dimension. Overall, the model with interaction effects explained 37.2% (vs. 33% for the model without interaction terms) of the variance in the climate anxiety-CEI dimension and 35.1% (vs. 30% for the model without interaction terms) of the variance in the climate anxiety-FI dimension, and 22% of the emotional consequences to information on climate change. The inclusion of interaction effects resulted in the disappearance of significant effects of CFC on climate anxiety: CFC-I dimension on climate anxiety-CEI dimension (from β = −0.16, p = 0.05 to β = 0.30, p = 0.11) and the effect of CFC-F dimension on climate anxiety-FI dimension (from β = 0.18, p = 0.05 to β = −0.13, p = 0.46, Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Standardized Estimates from Structural Equation Model with interactions. Latent factor indicators not shown for clarity. Blue arrows represent positive relationships. Red arrows represent negative relationships. Black dashed arrows represent non-significant relationships. † p < 0.10. * p < 0.05. ** p < 0.01. *** p < 0.001.

4. Discussion

The objective of this study was to examine the influence of Consideration of Future or Immediate Consequences of our actions and of information-seeking behaviors on the manifestations of climate anxiety in a population of young adults. The results show that: (1) CFC and information seeking predict climate anxiety, which in turn predicts the emotional consequences of exposure to information about the negative consequences of climate change; (2) information seeking moderates the effects of CFC on climate anxiety. To our knowledge, this is the first study to empirically provide evidence that both temporal orientation and information seeking predict climate anxiety, and some associated emotional consequences. According to our hypotheses, three results are noteworthy.

First, individuals with high CFC-F experience more climate anxiety-FI, which is not the case for individuals with high CFC-I. For these participants, the higher their CFC-I, the less climate anxiety-CEI they experience. These results partially confirm hypothesis 1 and could be explained by the propensity of future-oriented individuals, on the one hand, to conduct their actions in the present according to long-term goals and objectives [76] and, on the other hand, to act more in the collective interest [77]. Thus, individuals with high CFC-F are more likely to have integrated the long-term goals set by society to prevent the consequences of climate change. They can therefore more easily anchor their present behaviors in the achievement of these future goals. However, given the huge task at hand, these high CFC-F youth cannot achieve the goals set by society through their behavior alone, which may lead them to experience more climate anxiety than others. On the other hand, youth with high CFC-I probably have not integrated these long-term goals or are able to distance themselves from them, so they seem less prone to climate anxiety. Above all, these individuals are looking to satisfy their short-term needs. The negative consequences of climate change, rather positioned in the future, do not seem to have enough impact in their minds to influence current behavior.

Second, the higher the tendency of these youth to seek information about climate change issues, the more likely they are to experience climate anxiety. However, the state of emotional tension in situations of exposure to this information is particularly important for individuals with high climate anxiety-CEI. These results confirm hypothesis 2 and partially confirm hypothesis 3. It seems that these young French people use the search for information as a way of objectifying and giving sense [78] to the consequences of climate change that they cannot directly experience, as is already the case in certain regions of the world [79]. These new elements may lead begin a reflexive process [78] aimed at critically evaluating, interpreting and giving sense of media events and disasters. This reflection process contributes to the development of knowledge, beliefs, perceptions of climate change and its consequences. This may explain why this population, which is not directly confronted with the problem, seems to be particularly sensitive to climate anxiety.

Third, the results of this study indicate that for youth with high CFC-F, it appears that information seeking is something that increases their perceived anxiety as it affects their daily lives (i.e., functional anxiety), but does not really allow them to cope with the emotional consequences of perceived climate anxiety (i.e., cognitive emotional anxiety). Conversely, for individuals with high CFC-I, the more information they seek, the less climate anxiety-CEI they experience. These results partially support hypothesis 4. As suggested by Reser and Swim [46], information seeking appears to be a proactive and reactive behavioral response that affects how an individual copes with the psychological impacts of climate change. For these young adults, the reflection process initiated by the search for information can be seen as a coping strategy to manage the problem [80]. This process seems to have allowed them to take a step back and deal with the negative emotions they felt about the consequences of climate change. It is as if these individuals were reinforced in their initial positions; the more information they seek, the more elements they have to adapt, reminding them that climate change will have long-term impacts and that it does not affect them directly. In this study, it seems that it is the individual preference for time orientation (immediate or future) that influences information seeking as a coping strategy.

However, this study has some limitations. First, the data were cross-sectional in design, which means that the results are thus correlational in nature. Additional research using longitudinal (at least three waves of data collection) and experimental designs is needed to test the direction of associations. The recruitment method based on social media platforms did not allow the recruitment of participants from different geographical areas, which is potentially relevant for predicting climate anxiety. Further research is needed to address this limitation by including participant’s geographical locations. A comparison of our theoretical model between youth living near flood-prone areas in the south of France and youth living in the north may reveal differences [29]. Finally, the study carried out did not fully investigate people’s relationship to time. Indeed, our hypotheses were mainly concerned with the future temporal perspective adopted by young people towards climate change, and we therefore focused on the consideration of future consequences [56]. Yet, it would have been interesting to study the past experiences of these individuals with disasters or events directly related to climate change. Future studies could thus investigate how the three dimensions of the relationship to time [54] may impact on coping behaviors to reduce climate anxiety.

5. Conclusions

In 2020, Wu and colleagues [42] called on the scientific community to work on levers to reduce the climate anxiety felt by young people. The study presented in this article contributes to this effort by shedding new light on the relationship between the consideration of future consequences [57] and the role of information on the climate anxiety felt by young adults. In particular, the study describes the effects of temporal orientation on behavioral responses (i.e., information seeking).

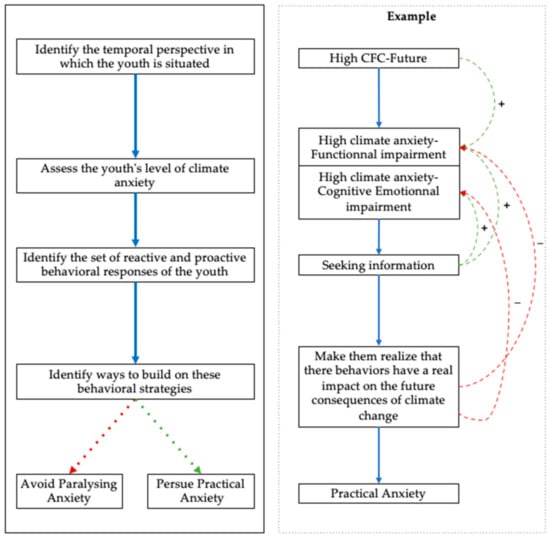

The topic of climate anxiety in young people has been little studied empirically, so these results offer some interesting insights for health professionals (e.g., physicians, psychiatrists, psychologists, etc.). Thus, the results of this study suggest that the accompaniment of a young person confronted with the emotional consequences of climate change could include 5 stages (see Figure 4 below).

Figure 4.

Accompanying a young person facing the emotional consequences of climate change.

The 5 stages of youth care would require: (1) to identify the temporal perspective in which they are situated (e.g., a high CFC-F individual); (2) to studying, as suggested by Reser and Swim [46], the individual’s set of proactive behavioral responses (e.g., Seeking information; Seeking interpersonal or community social support etc.); (3) to assessing one’s level of climate anxiety (e.g., high climate anxiety-FI); (4) to studying, the individual’s set of reactive behavioral responses (e.g., Seeking information; Seeking interpersonal or community social support etc.) [46]; and (5) to identify ways to build on these behavioral strategies (e.g., make them realize that these behaviors have a real impact on the future consequences of climate change). The idea could be to ensure that the individual is not positioned in a paralyzing climate anxiety that would prevent them from adopting pro-environmental behaviors that could reduce their anxiety, but rather in a practical anxiety that would lead them to not feel too much anxiety but enough to take action [36]. Although this proposed intervention model is based on the results of this study, it would require a full research program to investigate the psychological processes involved and to test its efficiency in the field to help youth cope with their climate anxiety.

Finally, these encouraging results need to be tested in future research to enable health professionals to support young women and men of today and tomorrow in dealing with the psychological consequences of climate change.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/psych4030043/s1, Table S1: Reliability estimates, descriptive statistics, and factor loadings; Table S2: Correlations between latent variables.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.N., J.-C.D. and L.B.; methodology, K.N., J.-C.D. and L.B.; formal analysis, K.N., J.-C.D. and L.B.; data curation, K.N., J.-C.D., L.B., S.B. and L.M.; writing—original draft preparation, K.N.; writing—review and editing, K.N., J.-C.D., L.B., S.B., D.L.F., L.M., S.D. and A.S.; supervision, A.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study is defined as non-interventional research and was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (1964) and its subsequent amendments (2001), the ethical principles of the French Code of Ethics for Psychologists (2012), as well as the Ethical Principles of Psychologists and the American Psychological Association Code of Conduct (2017). Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to its voluntary nature and anonymity.

Informed Consent Statement

Participants were informed of the purpose of the study in a cover letter and were assured that their data would remain confidential. Participants were required to give explicit consent to access the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article and Supplementary Materials and are openly available at https://osf.io/v9rts/ (accessed on 28 August 2022).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Emotional Consequences of Exposure to Climate Change Information

- I feel calm (R)

- I feel good, comfortable (R)

- I feel safe (R)

- I feel calm (R)

- I feel relaxed (R)

- I am worried

- I feel good (R)

References

- Ferreira, R. Climate Change, Resilience and Trauma: Course of Action Through Research, Policy, and Practice. Traumatology 2020, 26, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nations, U. Causes and Effects of Climate Change. Available online: https://www.un.org/en/climatechange/science/causes-effects-climate-change (accessed on 23 August 2022).

- World Health Organization. Climate Change and Health. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/climate-change-and-health (accessed on 23 August 2022).

- Cissé, G.; McLeman, R.; Adams, H.; Aldunce, P.; Bowen, K.; Campbell-Lendrum, D.; Clayton, S.; Ebi, K.L.; Hess, J.; Huang, C.; et al. Health, Wellbeing and the Changing Structure of Communities. In Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability; Pörtner, H.-O., Roberts, D.C., Tignor, M.M.B., Poloczanska, E.S., Mintenbeck, K., Alegria, A., Craig, M., Langsdorf, S., Löschke, S., Möller, V., et al., Eds.; Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Haines, A.; Ebi, K. The Imperative for Climate Action to Protect Health. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 380, 263–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keswani, A.; Akselrod, H.; Anenberg, S.C. Health and Clinical Impacts of Air Pollution and Linkages with Climate Change. NEJM Evid. 2022, 1, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, L.; Conlon, K.C.; Sorensen, C.; McEachin, S.; Nadeau, K.; Kakkad, K.; Kizer, K.W. Climate Change and Extreme Heat Events: How Health Systems Should Prepare. NEJM Catal. 2022, 3, CAT.21.0454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hames, J.; Vardoulakis, S. Climate Change Risk Assessment for the Heatlh Sector; DEFRA: London, UK, 2012; p. 240.

- Kovats, R.; Osborn, D. UK Climate Change Risk Assessment 2017: Evidence Report. Chapter 5: People & the Built Environment; Adaptation Sub-Committee of the Committee on Climate Change: London, UK, 2016.

- Stanke, C.; Murray, V.; Amlôt, R.; Nurse, J.; Williams, R. The Effects of Flooding on Mental Health: Outcomes and Recommendations from a Review of the Literature. PLoS Curr. 2012, 4, e4f9f1fa9c3cae. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watts, N.; Amann, M.; Arnell, N.; Ayeb-Karlsson, S.; Belesova, K.; Boykoff, M.; Byass, P.; Cai, W.; Campbell-Lendrum, D.; Capstick, S.; et al. The 2019 Report of The Lancet Countdown on Health and Climate Change: Ensuring That the Health of a Child Born Today Is Not Defined by a Changing Climate. Lancet 2019, 394, 1836–1878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pachauri, R.K.; Allen, M.R.; Barros, V.R.; Broome, J.; Cramer, W.; Christ, R.; Church, J.A.; Clarke, L.; Dahe, Q.; Dasgupta, P.; et al. Climate Change 2014: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Pachauri, R.K., Meyer, L., Eds.; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014; p. 151. ISBN 978-92-9169-143-2. [Google Scholar]

- Balbus, J.; Crimmins, A.; Gamble, J.; Easterling, D.; Kunkel, K.; Saha, S.; Sarofim, M. Ch. 1: Introduction: Climate Change and Human Health; US Global Change Research Program: Washington, DC, USA, 2016; pp. 25–42.

- Trombley, J.; Chalupka, S.; Anderko, L. Climate Change and Mental Health. Am. J. Nurs. 2017, 117, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charlson, F.; Ali, S.; Augustinavicius, J.; Benmarhnia, T.; Birch, S.; Clayton, S.; Fielding, K.; Jones, L.; Juma, D.; Snider, L.; et al. Global Priorities for Climate Change and Mental Health Research. Environ. Int. 2022, 158, 106984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. 2021 WHO Health and Climate Change Survey Report; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021; p. 96.

- Albrecht, G. “Solastalgia”. A New Concept in Health and Identity. Philos. Act. Nat. 2005, 3, 41–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moser, S.C. More Bad News: The Risk of Neglecting Emotional Responses to Climate Change Information. In Creating a Climate for Change: Communicating Climate Change and Facilitating Social Change; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2007; pp. 64–80. ISBN 978-0-521-86923-2. [Google Scholar]

- Verplanken, B.; Roy, D. “My Worries Are Rational, Climate Change Is Not”: Habitual Ecological Worrying Is an Adaptive Response. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e74708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Reser, J.P.; Bradley, G.; Ellul, M. Coping with Climate Change: Bringing Psychological Adaptation in from the Cold; Nova Science Publishers: Hauppauge, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 1–34. ISBN 978-1-62081-464-2. [Google Scholar]

- Bourque, F.; Willox, A.C. Climate Change: The next Challenge for Public Mental Health? Int. Rev. Psychiatry 2014, 26, 415–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, H.L.; Bowen, K.; Kjellstrom, T. Climate Change and Mental Health: A Causal Pathways Framework. Int. J. Public Health 2010, 55, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayes, K.; Poland, B. Addressing Mental Health in a Changing Climate: Incorporating Mental Health Indicators into Climate Change and Health Vulnerability and Adaptation Assessments. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.; Kim, H.; Gasparrini, A.; Armstrong, B.; Honda, Y.; Chung, Y.; Ng, C.F.S.; Tobias, A.; Íñiguez, C.; Lavigne, E.; et al. Suicide and Ambient Temperature: A Multi-Country Multi-City Study. Environ. Health Perspect. 2019, 127, 117007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baudon, P.; Jachens, L. A Scoping Review of Interventions for the Treatment of Eco-Anxiety. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 9636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cunsolo, A.; Harper, S.L.; Minor, K.; Hayes, K.; Williams, K.G.; Howard, C. Ecological Grief and Anxiety: The Start of a Healthy Response to Climate Change? Lancet Planet. Health 2020, 4, e261–e263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coffey, Y.; Bhullar, N.; Durkin, J.; Islam, M.S.; Usher, K. Understanding Eco-Anxiety: A Systematic Scoping Review of Current Literature and Identified Knowledge Gaps. J. Clim. Change Health 2021, 3, 100047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gousse-Lessard, A.-S.; Lebrun-Paré, F. Regards croisés sur le phénomène « d’écoanxiété »: Perspectives psychologique, sociale et éducationnelle. Centr’ERE 2022, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clayton, S.; Karazsia, B.T. Development and Validation of a Measure of Climate Change Anxiety. J. Environ. Psychol. 2020, 69, 101434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grupe, D.W.; Nitschke, J.B. Uncertainty and Anticipation in Anxiety: An Integrated Neurobiological and Psychological Perspective. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2013, 14, 488–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doherty, T.J.; Clayton, S. The psychological impacts of global climate change. Am. Psychol. 2011, 66, 265–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clayton, S.; Manning, C.; Hodge, C. Beyond Storms & Droughts: The Psychological Impacts of Climate Change; American Psychological Association and ecoAmerica: Washington, DC, USA, 2014; p. 52. [Google Scholar]

- Helm, S.V.; Pollitt, A.; Barnett, M.A.; Curran, M.A.; Craig, Z.R. Differentiating Environmental Concern in the Context of Psychological Adaption to Climate Change. Glob. Environ. Change 2018, 48, 158–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albrecht, G. Chronic Environmental Change: Emerging ‘Psychoterratic’ Syndromes. In Climate Change and Human Well-Being: Global Challenges and Opportunities; Weissbecker, I., Ed.; International and Cultural Psychology; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 43–56. ISBN 978-1-4419-9742-5. [Google Scholar]

- Moser, S.C.; Dilling, L. Creating a Climate for Change: Communicating Climate Change and Facilitating Social Change; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2007; ISBN 978-0-521-04992-4. [Google Scholar]

- Panu, P. Anxiety and the Ecological Crisis: An Analysis of Eco-Anxiety and Climate Anxiety. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palinkas, L.A.; Wong, M. Global Climate Change and Mental Health. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2020, 32, 12–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cianconi, P.; Betrò, S.; Janiri, L. The Impact of Climate Change on Mental Health: A Systematic Descriptive Review. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, S.E.L.; Sanson, A.V.; Van Hoorn, J. The Psychological Effects of Climate Change on Children. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2018, 20, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hickman, C.; Marks, E.; Pihkala, P.; Clayton, S.; Lewandowski, R.E.; Mayall, E.E.; Wray, B.; Mellor, C.; Susteren, L. Van Climate Anxiety in Children and Young People and Their Beliefs about Government Responses to Climate Change: A Global Survey. Lancet Planet. Health 2021, 5, e863–e873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanson, A.V.; Van Hoorn, J.; Burke, S.E.L. Responding to the Impacts of the Climate Crisis on Children and Youth. Child Dev. Perspect. 2019, 13, 201–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Snell, G.; Samji, H. Climate Anxiety in Young People: A Call to Action. Lancet Planet. Health 2020, 4, e435–e436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunasiri, H.; Wang, Y.; Watkins, E.-M.; Capetola, T.; Henderson-Wilson, C.; Patrick, R. Hope, Coping and Eco-Anxiety: Young People’s Mental Health in a Climate-Impacted Australia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 5528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, T.; Moore, J.; Cleary, A. Climate Change Impacts on the Mental Health and Wellbeing of Young People: A Scoping Review of Risk and Protective Factors. Soc. Sci. Med. 2022, 301, 114888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crandon, T.J.; Scott, J.G.; Charlson, F.J.; Thomas, H.J. A Social-Ecological Perspective on Climate Anxiety in Children and Adolescents. Nat. Clim. Change 2022, 12, 123–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz, C.D.; Silverman, W.K.; Jaccard, J.; La Greca, A.M. Children’s State Anxiety in Reaction to Disaster Media Cues: A Preliminary Test of a Multivariate Model. Psychol. Trauma: Theory Res. Pract. Policy 2011, 3, 157–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, B.J.; Xiong, Y.X.; Yip, P.S.Y.; Lao, C.K.; Shi, W.; Sou, E.K.L.; Chang, K.; Wang, L.; Lam, A.I.F. The Association between Disaster Exposure and Media Use on Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Following Typhoon Hato in Macao, China. Eur. J. Psychotraumatol. 2019, 10, 1558709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reser, J.P.; Swim, J.K. Adapting to and Coping with the Threat and Impacts of Climate Change. Am. Psychol. 2011, 66, 277–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Currie, J.; Deschênes, O. Children and Climate Change: Introducing the Issue. Future Child. 2016, 26, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albert, M.; Hurrelmann, K.; Quenzel, G.; Gensicke, T.; Leven, I.; Picot, S.; Schneekloth, U.; Willert, M. Jugend 2010. Eine Pragmatische Generation Behauptet Sich; Fischer-Taschenbuch-Verlag: Frankfurt, Germany, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hicks, D.; Holden, C. Remembering the Future: What Do Children Think? Environ. Educ. Res. 2007, 13, 501–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rickinson, M. Learners and Learning in Environmental Education: A Critical Review of the Evidence. Environ. Educ. Res. 2001, 7, 207–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojala, M. Hope and Climate Change: The Importance of Hope for Environmental Engagement among Young People. Environ. Educ. Res. 2012, 18, 625–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewin, K. Field Theory in Social Science: Selected Theoretical Papers; Cartwright, D., Ed.; Harpers: Oxford, UK, 1951; p. 346. [Google Scholar]

- Camus, G.; Berjot, S.; Ernst-Vintila, A. French validation of the Consideration of Future Consequences scale (CFC-14). Rev. Int. Psychol. Soc. 2014, 27, 35–63. [Google Scholar]

- Strathman, A.; Gleicher, F.; Boninger, D.S.; Edwards, C.S. The Consideration of Future Consequences: Weighing Immediate and Distant Outcomes of Behavior. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1994, 66, 742–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joireman, J.; Shaffer, M.J.; Balliet, D.; Strathman, A. Promotion Orientation Explains Why Future-Oriented People Exercise and Eat Healthy: Evidence From the Two-Factor Consideration of Future Consequences-14 Scale. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2012, 38, 1272–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boniwell, I.; Zimbardo, P.G. Balancing Time Perspective in Pursuit of Optimal Functioning. In Positive Psychology in Practice; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2004; pp. 165–178. ISBN 978-0-471-45906-4. [Google Scholar]

- Joireman, J.; King, S. Individual Differences in the Consideration of Future and (More) Immediate Consequences: A Review and Directions for Future Research. Soc. Personal. Psychol. Compass 2016, 10, 313–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Williams, K.D. Imagined Future Social Pain Hurts More Now than Imagined Future Physical Pain. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 2012, 42, 314–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oettingen, G. Future Thought and Behaviour Change. Eur. Rev. Soc. Psychol. 2012, 23, 1–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joireman, J.; Liu, R.L. Future-Oriented Women Will Pay to Reduce Global Warming: Mediation via Political Orientation, Environmental Values, and Belief in Global Warming. J. Environ. Psychol. 2014, 40, 391–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmi, N.; Arnon, S. The Role of Future Orientation in Environmental Behavior: Analyzing the Relationship on the Individual and Cultural Levels. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2014, 27, 1304–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milfont, T.L.; Wilson, J.; Diniz, P. Time Perspective and Environmental Engagement: A Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Psychol. 2012, 47, 325–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geiger, N.; McLaughlin, B.; Velez, J. Not All Boomers: Temporal Orientation Explains Inter- and Intra-Cultural Variability in the Link between Age and Climate Engagement. Clim. Change 2021, 166, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojala, M.; Lakew, Y. Young People and Climate Change Communication. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Climate Science; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berryman, C.; Ferguson, C.J.; Negy, C. Social Media Use and Mental Health among Young Adults. Psychiatr. Q. 2018, 89, 307–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouguiama-Daouda, C.; Blanchard, M.A.; Coussement, C.; Heeren, A. On the Measurement of Climate Change Anxiety: French Validation of the Climate Anxiety Scale. Psychol. Belg. 2022, 62, 123–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spielberger, C.D. State-Trait Anxiety Inventory for Adults; Mind Garden: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Spielberger, C.D.; Bruchon-Schweitzer, M.; Paulhan, I. STAI-Y: Inventaire D’anxiété Etat-Trait Forme Y; Éditions du Centre de Psychologie Appliquée: Paris, France, 1993; ISBN 978-2-7253-0003-0. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén, L.K.; Muthén, B.O. Mplus: Statistical Analysis With Latent Variables (User’s Guide)—Version 5; Muthen & Muthen: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff Criteria for Fit Indexes in Covariance Structure Analysis: Conventional Criteria versus New Alternatives. Struct. Equ. Modeling Multidiscip. J. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslowsky, J.; Jager, J.; Hemken, D. Estimating and Interpreting Latent Variable Interactions: A Tutorial for Applying the Latent Moderated Structural Equations Method. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 2015, 39, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieters, C.; Pieters, R.; Lemmens, A. Six Methods for Latent Moderation Analysis in Marketing Research: A Comparison and Guidelines. J. Mark. Res. 2022, 59, 941–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, A.; Moosbrugger, H. Maximum Likelihood Estimation of Latent Interaction Effects with the LMS Method. Psychometrika 2000, 65, 457–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lens, W.; Paixao, M.P.; Herrera, D.; Grobler, A. Future Time Perspective as a Motivational Variable: Content and Extension of Future Goals Affect the Quantity and Quality of Motivation. Jpn. Psychol. Res. 2012, 54, 321–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Lange, P.A.M.; Joireman, J.A. How We Can Promote Behavior That Serves All of Us in the Future. Soc. Issues Policy Rev. 2008, 2, 127–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mezirow, J. Transformative Dimensions of Adult Learning; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1991; p. 247. ISBN 978-1-55542-339-1. [Google Scholar]

- Leal Filho, W.; Azeiteiro, U.M.; Balogun, A.-L.; Setti, A.F.F.; Mucova, S.A.R.; Ayal, D.; Totin, E.; Lydia, A.M.; Kalaba, F.K.; Oguge, N.O. The Influence of Ecosystems Services Depletion to Climate Change Adaptation Efforts in Africa. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 779, 146414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarus, R.S.; Folkman, S. Stress, Appraisal, and Coping; Springer Publishing Company: New York, NY, USA, 1984; ISBN 978-0-8261-4192-7. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).