Abstract

(1) Background: As an emerging topic, no known study to date has described interviews with US dentists regarding their experiences during the beginning of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) with regard to office closures and their implications for both the dentists and the patients they serve, especially among dentists in their first decade of work and new to practice ownership roles. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to describe the experiences of early-career US dentists during the initial stages of the COVID-19 pandemic. (2) Methods: This study utilized a semi-structured interview protocol and employed qualitative descriptive methodology. SPSS 26 and NVivo12 were utilized for data analysis. (3) Results: In April 2020, a total of 12 early-career US dentists completed the interview study protocol. The study sample majority was male (67%), with a mean age of 32 (range = 30–37) and an average of 6 years of dental practice experience (range = 5–10). Participants completed phone interviews with the research team. In summary, three organizing themes emerged: (1) Dentistry during COVID-19: Experiences during the first wave, (2) Long-term concerns regarding COVID-19, and (3) COVID-19 professional communication and dental research. (4) Conclusions: The chief findings of this study are dentists’ long-term concerns for the profession post-COVID-19. Research must still determine how to best prepare for future infectious disease outbreaks with regards to safeguarding the health of the dental workforce and maintaining the oral health of patient populations.

1. Introduction

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is a respiratory illness that began spreading throughout the globe in early 2020, with over 547 million confirmed cases and nearly 6.4 million deaths to date [1]. While the full scope of the clinical presentation of COVID-19 is yet to be fully described, serious complications are most common among adults 65 years and older and among individuals with underlying cardiac conditions, pulmonary disease, and diabetes [1]. In the United States, state and federal mandates to close businesses and shelter-in-place caused the State Dental Societies and American Dental Association (ADA) to formally recommended that dentists close their offices to all but emergency care. Primary announcements of this decision began in mid-March 2020 [2] at the state-level, with subsequent formal recommendations from the ADA communicated on 1 April 2020. In total, US-based dental offices were closed for weeks to months, with offices reopening for routine care on a state-by-state basis with the most recent “Interim Reopening Guidance for Dental Settings” provided by the US Center for Disease Control updated on 18 June 2020 [3].

Office closures around the globe have not only been for the protection of patients’ health but also for dental providers and staff [4]. “Dentists [and support staff including hygienists and assistants] are among the highest risk for transmission and contraction of the virus” as COVID-19 is transmitted through aerosol spray from individuals’ mouths [4,5]. Also of concern for the dental community is the world-wide shortage of personal protective equipment (PPE), which protects both dental staff and patients alike and is essential to minimize the risk of transmission of COVID-19 and other diseases. As an emerging topic, no known study to date has examined US dentists’ experiences during COVID-19 with regard to office closures, care of emergency patients, personal protective equipment (PPE) changes, and the short- and long-term concerns for the dental profession following COVID-19. This topic is of particular importance to early-career dentists who, from a public health standpoint, require support during their transitional years to independent practice given literature documented concerns regarding dentists’ “short career expectancies”, “early professional burnout”, and issues with practice viability [6].

Therefore, the purpose of this study was to describe the experiences of early-career US dentists during the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic. Through thematic analysis, the study details the perspectives shared by dentists with regard to the impact of COVID-19 on their dental practice and the oral health of their patient populations.

2. Materials and Methods

This study utilized qualitative descriptive methodology, employing a semi-structured individual interview protocol for data collection. Prospective research study participants were recruited from throughout the US using a direct approach, including purposive sampling with additional snowball sampling technique employed via word of mouth through practitioner relations. The interviews were not anonymous as the principal investigator’s professional network was utilized to recruit participants. The research study team (JRS, SDS) determined the inclusion criteria of practicing dentists in the United States, which included both practice owners and associates, general dentists, and specialists. The study team purposefully ensured that early-career dentists in a variety of practice settings were included in the research design. For the purposes of this study, early career is defined as dentists with 10 or fewer years of dental experience post-graduation. The primary investigator and clinician on the study team (JRS) was responsible for participant recruitment. Both research study team members were responsible for data collection, data analysis, and writing. At the completion of the 9th interview, the research study team convened to discuss initial findings from interviews 1–9 and reached consensus that the study’s main organizing themes had been identified. In keeping with qualitative methodology best-practices, three subsequent interviews were conducted to confirm that data saturation had been reached with the achievement of “informational redundancy” [7].

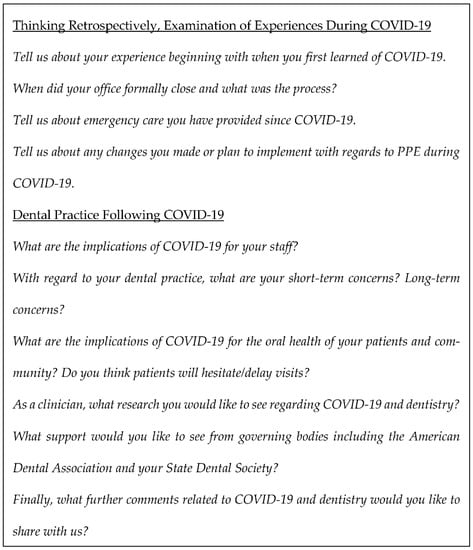

The interview guide utilized in this study design was developed to capture both the retrospective and prospective perspectives of dentists during COVID-19 (Figure 1). This interview guide, semi-structured in design, allowed for consistency from interview to interview while allowing for variability by employing open-ended questions with additional probes to ascertain the individual experience of each interviewed dentist, irrespective of variations in practice structures, areas of specialty, and patient populations. All research study team members approved the final draft of the interview guide. Developed interview guide questions allowed the research team to capture each dentists’ demographic characteristics and work experience and experience with COVID-19 from the time they first became aware of the virus.

Figure 1.

Interview Study Guide.

Institutional Review Board approval was obtained from DePaul University, Chicago IL, USA. All research study team members were registered with CITI. Following IRB approval, the research study team recruited dentists via email and phone to participate in the study protocol. Each study interview was conducted by both investigators as a team. Each interview lasted 15–20 min. At the onset of the interview, the research methodologist (SDS) walked the study participant through the IRB approved information sheet describing the study design and purpose and acquired oral consent for participation. The audio recording was then begun. The research methodologist then asked the study participant their demographic characteristic information. Following this general information, the primary investigator clinician (JRS) on the study team conducted the formal interview, walking each study participant through the formal questions described in the interview guide, clarifying responses, and asking approved probing questions as necessary. Interview questions focused on office closings, emergency care provided, changes to personal protective equipment, staffing, the implications of COVID-19 on the oral health of their patients, and dental practice following COVID-19. The research study team debriefed following each of the 12 interviews.

Audio recordings of each interview were uploaded into a secure cloud storage environment for data storage. Transcription of the audio files was completed by Rev, a professional online transcription company. Each audio file was transcribed verbatim into a Microsoft Office Word document by a Rev-employed transcriptionist. The primary investigator clinician reviewed each written transcript with the coinciding audio file to ensure accuracy for data verification purposes. Study participant demographic characteristics were analyzed by the research methodologist utilizing SPSS 26 (SPSS 26, IBM Corp, Arkmonk, NY, USA). Interview data was qualitatively analyzed, utilizing thematic analysis employing NVIVO 12.5.0 software (QSR International Pty Ltd., Burlington, MA, USA). The research study team members first examined the transcripts independently to identify preliminary organizing themes before then discussing and refining organizing themes to ensure consistency and reach consensus.

3. Results

A total of 12 dentists completed the interview study protocol in this preliminary examination of the experiences of early-career US dentists during the initial stages of the COVID-19 pandemic. Study participants’ characteristics are described in Table 1. The study sample majority was male (67%), with a mean age of 32 (range = 30–37) and an average of 6 years of dental practice experience (range = 5–10). Study participants were predominantly general practitioners (75%) who owned their own practices (58%) with an average of seven operatories (range = 4–14). Participants qualitatively described their professional perspectives and dental practice experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic in phone interviews with the research study team members. In summary, three organizing themes emerged, as illustrated in Table 2, Table 3 and Table 4: (1) Dentistry during COVID-19: Experiences during the first wave, (2) Long-term concerns regarding COVID-19, and (3) COVID-19 professional communication and dental research.

Table 1.

Summary of Study Participant Characteristics.

Table 2.

Dentistry during COVID-19: Experiences during the first wave.

Table 3.

Long-term concerns regarding COVID-19.

Table 4.

COVID-19 Professional Communication and Dental Research.

3.1. Theme 1: Dentistry during COVID-19: Experiences to during the First Wave

The first organizing theme, Dentistry during COVID-19: Experiences during the first wave, details dentists’ experiences with office closures, emergency care provided, PPE, how COVID-19 has impacted staff members, and participating dentists’ short-term concerns related to reopening (Table 2).

3.1.1. Office Closures

Participating dentists unanimously described “abrupt” office closures where the decision to formally close was made quickly, as exemplified in one participant’s statement that “it kind of felt like the rug was pulled out from underneath us…there was very little time to prepare”. At the time of office closures, dentists recalled a “chaotic” environment in which staff, including “hygienist[s] and assistant[s]”, were on the phone “reschedul[ing] and cancel[ing]” patients.

3.1.2. Emergency Care Provided

Participating dentists utilized “phone triage” and “teledentistry”, including video and “pictures” from patients to communicate with those who contacted their offices with emergency concerns. The chief complaints in the first weeks following office closures due to the stay-at-home orders were pain and swelling. As time went on, some reported that they did not “[feel] comfortable letting patients go that long without being seen if they [were] in pain” and began to provide in-office care on an “as-needed basis”. Dentists also described providing education and instruction to patients who called with non-emergent needs such as missing crowns and chipped teeth.

3.1.3. PPE

Participating dentists consistently noted implementing changes to PPE from previous practice to integrate the use of “N95 masks”, double layered masks where an N95 is worn “with a disposable class one mask over” it, “face shields”, “hairnets”, “gowns”, “eye-protection”, and even disposable shoe covers. Participants discussed how practice changes in PPE were made collaboratively with staff involvement. Many noted ongoing concerns with nationwide PPE shortages and increased or unfair PPE costs.

3.1.4. Impact of COVID-19 on Staff

Participating dentists reported overwhelmingly that “staff seem to be coping well” and are “willing to go back when [dentistry] is deemed essential and [the] practice thinks it’s safe”. For staff members with hesitations, the main concern is “the fear of getting sick”. One participating dentist reported,

“They are very…concerned that we have adequate PPE, making sure we can implement social distancing and…change the flow of our days when we get back.”

Dentists noted changes they would be making to accommodate the concerns of staff, including increased PPE measures and new protocols including the avoidance of “ultrasonic scalers” and shifting to “mostly hand-scaling” to address hygienists’ concerns regarding aerosols.

3.1.5. Short-Term Concerns

In the short-term, participating general dentists described being overwhelmed by the “bottle neck” of “backlogged” patients that had to be rescheduled due to office closures. In addition, treatment needs that were present before closure could be amplified and become more urgent. They also spoke of concerns regarding patients delaying appointments due to ongoing fear of contracting COVID-19, as articulated by one participant, “We can’t tell [patients] that [they] are 100% safe here… You can’t ever eliminate 100% of risk” in a patient care environment.

3.2. Theme 2: Long-Term Concerns Regarding COVID-19

The second organizing theme, Long-term concerns regarding COVID-19, details participating dentists’ perspectives on COVID-19’s impact on oral health disparities, practice viability, and financial concerns, as well as the profession’s response to COVID-19 as a precedent for how infectious disease outbreaks impact contemporary dentistry (Table 3).

3.2.1. COVID-19’s Impact on Oral Health Disparities

Participating dentists spoke of how COVID-19 may disproportionally impact the oral health of specific demographic groups within their communities of care, including “high risk” categories such as the “elderly”, “those with hypertension or uncontrolled diabetes”, and patients of low socioeconomic status. They described concerns regarding whether treatment of older adults should be delayed to minimize their risk of contracting COVID-19 in the dental office, noting that “they’re scared to come in”. One participant stated that they anticipated that delayed care due to COVID-19 would affect, not only patients’ dental health, but would also have implications for their systemic health. “[As] dental disease progresses, we know it doesn’t get better without intervention”, they added.

3.2.2. Practice Viability and Financial Concerns

Every participating early-career dentist spoke of financial concerns surrounding the viability of their practices following COVID-19. One participant shared,

“Long-term concerns for me is just dentistry in general. Is it going to be the same as what it was, what we planned for when we…went into the dental field? With a lot of people losing their jobs or being furloughed, [everyone’s] disposable income is dwindling or... nonexistent. When we do open up are people going to see dentistry as something that they need? We can open back up, but if nobody has the money or interested in getting work done, we’re still highly effected by the [aftermath] of [COVID-19]”.

Concerns about the economy going into a recession were particularly pressing for practice owners, who vocalized uncertainties surrounding reduced “new patient exams”, “elective procedures”, and “cash flow”. Apprehension regarding the financial future of dentistry was expressed by one participant as,

“I’m not sure what that’s going to do as far as effecting my specialty and this practice that I’ve been investing in for the last six and a half years… the student debt load that we all carry…the financial plans that [we] have… That’s [my] biggest long-term concern”.

3.2.3. COVID-19 as a Precedent

The final long-term concern expressed by dentists interviewed focused on dentistry in a post-COVID-19 world, questioning whether “these changes for infection control [are] going to become permanent” and if a resurgence of COVID-19 or another virus may impact dental offices into the future. As described by one participant,

“If [infectious disease outbreaks] become more of a regular issue...what [they may] do is force everyone to close their doors. That’s my long-term concern. What kind of precedent [does COVID-19] set moving forward? What is deemed a [nationwide] emergency? It sets a precedent business-wise in the future [that dental offices could] close... you could possibly go out of business”.

3.3. Theme 3: COVID-19 Professional Communication and Dental Research

The third and final organizing theme, COVID-19 professional communication and dental research, describes participating dentists’ retrospective and prospective perspectives of professional communication originating from the dental profession’s national and state-level governing bodies, as well as participants’ thoughts on future dental research surrounding COVID-19 that they feel would support their clinical practice (Table 4).

3.3.1. Governing Bodies Communication and Guidelines

Communication and guideline development from dentistry’s governing bodies were the most pervasive themes in the interviews with study participants. Participants noted that governing bodies in US dentistry were highly communicative, “sending out alerts” and working to keep “members in the loop as much as they can”. Participants resoundingly reported that governing bodies utilized their leadership to “advocate [dentists’] importance as healthcare providers” and “small business owners”. Participating dentists also vocalized that that they would like governing bodies to help ensure dentistry’s “access to PPE”, especially given that many dental providers donated their PPE supplies to medical centers.

Additionally, participating dentists described their desires for further regulations and recommendations from governing bodies in great detail. In sum, participants asked that the national and international dental associations put forth plans to “show us what a dental office [should] look like…in terms of how they expect it to function”, including a detailed plan from optimal scheduling of patient appointments, to front desk reception and check out, chair treatment, and updated PPE protocols. They asked, “what does that look like? What are the expectations?”, articulating a need for “practical implementation” of thorough guidelines. Participants noted that “it would be nice to have something to show patients right away if there’s ever any concerns”. They also spoke about whether these guidelines might vary between urban and rural practice locations, stating that perhaps state dental societies might examine what to implement for their constituents. In sum, dentists interviewed asked for “something more concrete. Because, they always say use your best clinical judgment...As a dentist, you feel you’re alone, if somebody tells you to just use your best clinical judgment, okay, fair enough, but my clinical judgment is not the same as yours in every scenario”.

3.3.2. Direction for Future Research

With regard to the future direction for dental research regarding COVID-19, study participants spoke at length about research surrounding aerosols, including the effectiveness of “high volume evacuation”, lifespan of COVID-19 on organic and non-organic surfaces, “how long the virus can be in the air”, and the effectiveness of varying masks utilized by dental offices. Participants also postulated about the best protocol for “actively treat[ing a patient] with coronavirus” and how dentistry can “prevent cross-contamination” of COVID-19. In general, the research interests of this sample of practicing dentists focused on infection control and safety.

4. Discussion

The early-career US dentists interviewed in this study universally described abrupt office closures, a variety of emergency care provided both remotely and in-person, adoption of higher levels of PPE, and staff support as well as short-term concerns around providing treatment to patients immediately post-office closures. The chief finding of this study is these dentists’ long-term concerns for the profession post-COVID-19, with future infectious disease outbreaks likely. Practice viability was expressed regarding the longevity of their businesses. They also expressed concerns that the stay-at-home and shelter-in-place orders set a precedent moving forward for what may happen again if there is a reemergence of COVID-19 or another infectious disease outbreak. These long-term concerns amongst our study participants echo the findings of Consolo et al. in a survey study of Italian dental practitioners that reported “practice closures” and “strong activity reduction” as well as “feelings of concern, anxiety, and fear” in dentists and “concerns about the professional future” and “hope for economic measures to help dental practitioners” [8]. This study also describes US dentists’ concerns for how COVID-19 may exacerbate oral health disparities in low socioeconomic groups and among older adults with comorbidities. In addition, this study’s qualitative findings contribute valuable narratives to the previous survey studies of dentists’ experiences during COVID-19 around the world, articulating topics including anxiety, provider preparedness, and increased stress among practitioners [9,10,11,12]. Furthermore, this qualitative descriptive study shares first-hand accounts of COVID-19’s impact on US dentistry, reinforcing the increased cost of providing care, challenges with implementation of safety protocols, and concerns for long term practice finances reported in Liu et al.’s examination of the pandemic’s effect on dentists’ workforce confidence and workflow in the US [13].

This study’s strengths include its novelty as the first known qualitative examination of US dentists’ experiences during COVID-19 and its descriptive design, which allowed for robust narrative data collection. However, our focus on solely early-career dentists and our utilization of purposive sampling and snowball sampling techniques, along with a modest sample size, limit the generalizability of our study findings. Therefore, our findings do not express the perspectives of all US-based dentists. However, this study adds to our collective understanding of the ways in which dental practice was impacted by COVID-19. Future research should examine the experiences of other dental practitioners by utilizing both qualitative and quantitative methods and how dental practice has further changed since the time of our data collection in spring 2020. In addition, much clinically-based and implementation-focused research remains to be done in order to determine how to best treat patients in a dental office settings in future pandemic periods.

5. Conclusions

This study describes the first known qualitative examination of US dentists’ experiences during COVID-19, with regard to office closures, care of emergency patients, personal protective equipment changes, and short and long-term concerns for the dental profession. It is important that we learn from the experiences of dentists during the COVID-19 pandemic to implement strategies to support dental clinicians and their practices during infectious disease outbreaks. Dental researchers have worked hard to provide evidence of the oral systemic connection, and collectively the dentists we interviewed felt that the health of their patients was overlooked by the extended office closures. Concrete evidence-based guidelines focused on patient safety and infection control need to be developed by governing bodies so that clinicians may implement them in a timely fashion. As a profession, dentists have the difficult task of determining ethical and logical approaches to optimize the oral health of their practice communities and the viability of their small businesses simultaneously. Dental professionals are urged to remain mindful of the risks associated with providing direct patient care during infectious disease outbreaks, and must remain committed to preserving the oral health of their patients.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: J.R.S. and S.D.S.; Methodology: J.R.S. and S.D.S.; Validation: J.R.S. and S.D.S.; Formal analysis: J.R.S. and S.D.S.; Investigation: J.R.S. and S.D.S.; Resources: J.R.S. and S.D.S.; Data curation: J.R.S. and S.D.S.; Writing—original draft preparation: J.R.S. and S.D.S.; writing—review and editing, J.R.S. and S.D.S.; visualization, J.R.S. and S.D.S.; supervision, J.R.S. and S.D.S.; project administration, S.D.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of DePaul University (protocol SS040820NUR approved 14 April 2020).

Informed Consent Statement

Per Institutional Review Board, formal informed consent was waived to protect the identities of participants. Oral consent was obtained following review of the information sheet with the research team before voluntary completion of the interview protocol.

Data Availability Statement

Study data are available upon request. Please contact the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The study authors would like to acknowledge Charles Lawrence, William Rudolph and John Edward (Teddy) for their support of this work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- World Health Organization. Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard. Available online: https://covid19.who.int (accessed on 5 July 2022).

- ISDS Issues Recommendations for Dental Offices Regarding COVID-19. Illinois State Dental Society. Available online: https://www.isds.org/news-details/2020/03/16/isds-issues-recommendations-for-dental-offices-regarding-covid-19 (accessed on 8 April 2020).

- CDC Releases Interim Reopening Guidance for Dental Settings. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/oralhealth/infectioncontrol/statement-COVID.html (accessed on 31 July 2020).

- Checchi, V.; Montevecchi, M.; Checchi, L. Variation of Efficacy of Filtering Face Pieces Respirators over Time in a Dental Setting: A Pilot Study. Dent. J. 2021, 9, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ADA Urges Dentists to Heed April 30 Interim Postponement Recommendation, Maintain Focus on Urgent and Emergency Dental Care Only. American Dental Association. Available online: https://www.ada.org/en/press-room/news-releases/2020-archives/april/summary-of-ada-guidance-during-the-covid-19-crisis?utm_source=adaorg&utm_medium=adahomerotator&utm_content=interim-statement&utm_campaign=covid-19 (accessed on 8 April 2020).

- Gorter, R.C.; Storm, M.K.; Te Brake, J.H.; Kersten, H.W.; Eijkman, M.A. Outcome of career expectancies and early professional burnout among newly qualified dentists. Int. Dent. J. 2007, 57, 279–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polit, D.F.; Beck, C.T. (Eds.) Sampling in Qualitative Research. In Nursing Research: Generating and Assessing Evidence for Nursing Practice, 10th ed.; Wolters Kluwer: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Consolo, U.; Bellini, P.; Bencivenni, D.; Iani, C.; Checchi, V. Epidemiological Aspects and Psychological Reactions to COVID-19 of Dental Practitioners in the Northern Italy Districts of Modena and Reggio Emilia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bellini, P.; Checchi, V.; Iani, C.; Bencivenni, D.; Consolo, U. Psychological reactions to COVID-19 and epidemiological aspects of dental practitioners during lockdown in Italy. Minerva Dent. Oral Sci. 2021, 70, 32–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrar, E.; Abduljabbar, A.S.; Naseem, M.; Panhwar, M.; Vohra, F.; Abduljabbar, T. Evaluating the Influence of COVID-19 Among Dental Practitioners After Lockdown. Inquiry 2021, 58, 469580211060753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sotomayor-Castillo, C.; Li, C.; Kaufman-Francis, K.; Nahidi, S.; Walsh, L.J.; Liberali, S.A.; Irving, E.; Holden, A.C.; Shaban, R.Z. Australian dentists’ knowledge, preparedness, and experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic. Infect. Dis. Health 2022, 27, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salehiniya, H.; Hatamian, S.; Abbaszadeh, H. Mental health status of dentists during COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Health Sci. Rep. 2022, 5, e617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, D.Z.; Gallo, G.N.; Babikow, E.; Wiesen, C.; Jackson, T.H.; Mitchell, K.; Jacox, L.A. Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on dentists’ workforce confidence and workflow. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 2022, 153, 610–624.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).