Abstract

This study examines the activity coefficients of benzene, toluene, and di-(2-ethylhexyl)phosphoric acid (D2EHPA) in binary benzene–D2EHPA and toluene–D2EHPA systems, as well as the ternary n-hexane–toluene–D2EHPA system, using gas chromatography at 293.0 K. The primary objective was to determine UNIFAC model interaction parameters and validate their accuracy for predicting thermodynamic behavior in these systems. Experimental measurements revealed activity coefficient maxima for benzene and toluene at mole fractions of 0.8–0.9, decreasing to 0.46–0.67 in dilute solutions. The UNIFAC interaction parameters were calculated as follows: ACH–HPO4 (−334, 4605), ACCH3–HPO4 (680, 467), and refined CH2–HPO4 (54, 1199). The UNIFAC model achieved deviations of less than 2% from experimental data in both binary and ternary systems. A novel methodology incorporating intermediate standards for gas chromatography was developed to overcome challenges in measuring volatile solvent concentrations, enhancing measurement precision. These findings enable accurate prediction of activity coefficients in mixtures of alkanes, cycloalkanes, and monoaromatic hydrocarbons with D2EHPA, offering significant implications for optimizing metal liquid–liquid extraction processes.

Keywords:

activity coefficients; D2EHPA; benzene; toluene; UNIFAC; gas chromatography; modelling; interaction parameters 1. Introduction

This study extends prior research on the binary n-hexane–di-(2-ethylhexyl)phosphoric acid (D2EHPA) system, where experimental activity coefficients of n-hexane were used to determine UNIFAC interaction parameters for the CH2–HPO4 group pair [1]. D2EHPA is a highly effective extractant widely employed in liquid–liquid extraction processes for separating rare earth elements [2,3], manganese [4], cadmium, nickel [5,6], aluminum, zinc, copper [7,8,9], and purifying metal-containing wastes [10,11]. Its efficacy stems from its ability to form stable complexes through cation-exchange and donor–acceptor mechanisms across diverse media, enhancing metal extraction efficiency [12,13,14,15,16].

Solvents play a pivotal role in liquid–liquid extraction by reducing extractant viscosity, improving phase separation, and influencing the extraction mechanism. Solvents affect metal complex formation [17,18,19], third-phase formation in extraction systems [20,21], and the solubility of D2EHPA in aqueous phases [14]. The influence of solvents is quantified through activity coefficients, which are critical for selecting optimal solvents [22,23], determining selectivity and distribution coefficients [24,25,26], and modeling phase equilibrium compositions [27,28,29].

The UNIFAC (UNIQUAC Functional-group Activity Coefficients) model was selected due to its group-contribution approach, which enables the prediction of activity coefficients in non-ideal liquid mixtures based on molecular structure. This method is widely used for systems composed of well-defined functional groups, such as CH2, CH3, ACH, ACCH3, HPO4. By accounting for both combinatorial (molecular size and shape) and residual (intergroup energy interactions) contributions to non-ideality, UNIFAC provides a reliable framework for extrapolating thermodynamic behavior to systems with limited experimental data [22,30]. A comprehensive description of the model can be found in standard references on thermodynamic modeling [31,32]. This study aims to measure the activity coefficients of benzene and toluene in binary benzene–D2EHPA and toluene–D2EHPA systems respectively, determine UNIFAC interaction parameters for ACH–HPO4 and ACCH3–HPO4 group pairs, and validate their accuracy in the ternary n-hexane–toluene–D2EHPA system. These parameters enable reliable prediction of activity coefficients for all components in mixtures of alkanes, cycloalkanes, and monoaromatic hydrocarbons with D2EHPA, crucial for optimizing metal extraction processes.

This work presents experimental activity coefficient data for binary D2EHPA–benzene and D2EHPA–toluene systems, obtained via gas chromatography at 293.0 K, addressing challenges in measuring volatile components across a wide range of vapor pressures. A novel methodology incorporating intermediate standards enhances measurement precision. By refining UNIFAC parameters and validating them in ternary systems, this study advances the understanding of non-ideal solution behavior and supports the design of efficient liquid–liquid extraction processes involving D2EHPA.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Reagents

In this work, high-grade benzene (CAS 71-43-2), high-grade toluene (CAS 108-88-3) from EKOS-1, and high-grade n-hexane (CAS 110-54-3), D2EHPA (CAS 298-07-7) at 99% purity from LeapChemCo. (Hangzhou, China) were used.

Di-2-ethylhexylphosphoric acid, benzene, and toluene were stored under controlled conditions in their original sealed containers in a dry, temperature-controlled warehouse. Storage facilities were maintained away from heat sources and direct sunlight, with all chemicals remaining within their validated shelf life (through December 2027).

All vapor–liquid equilibrium measurements were performed at a constant temperature of 293.0 K. This temperature was chosen to maintain consistency with prior experimental studies on related systems, such as the n-hexane–D2EHPA binary system investigated in our earlier work [1], thereby ensuring methodological continuity and facilitating the comparison and refinement of UNIFAC parameters across different solvent–extractant combinations. Furthermore, operating near room temperature offers practical advantages: it simplifies thermal control, minimizes errors associated with the temperature sensitivity of vapor-pressure measurements for volatile aromatic solvents, and corresponds to standard reference conditions commonly used in thermodynamic studies of organic mixtures [33].

2.2. Gas Chromatography (GC) Method

Vapor-phase concentrations of benzene, toluene, and n-hexane, in binary (benzene–D2EHPA, toluene–D2EHPA) and ternary (n-hexane–toluene–D2EHPA) solutions were measured using an Agilent GC-6890 gas chromatograph (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) equipped with a flame ionization detector (FID) and a 0.1 cm3 stainless steel dosing loop. Component separation was achieved on a Restek-QS-Bond capillary column (30 m length, 0.53 mm inner diameter, 20 μm phase thickness).

Activity coefficients of benzene, toluene and n-hexane were determined in a 0.27 L glass container thermostat at 293.0 K, equipped with a magnetic stirrer. The test solution filled approximately 20% of the container’s volume. Vapor samples were drawn through a 0.1 mL dosing loop, with a steel syringe needle venting to the atmosphere, using a 3 mL gas-tight syringe. Samples were collected at 90-s intervals, with at least five replicates per sample, and the average chromatographic peak area was calculated. To address variations in FID sensitivity, particularly for volatile solvents like toluene, intern standards (mixtures of known concentrations) were employed, as detailed in [1] and further discussed in Section 4.2, ensuring high precision across a wide range of vapor pressures.

The activity (aᵢ) of component i (benzene, toluene and n-hexane) was calculated as the ratio of its vapor pressure above the solution to that above the pure component, per Equation (1):

where is the activity of component i; and are vapour pressures (Pa) above the solution and pure component; is the vapor-phase concentration (mg/L) of component i in solution, and is the solvent concentration (mg/L) above the pure component at 293.0 K.

The activity coefficient (γᵢ) was calculated using Equation (2):

where is solvent activity coefficient of component i and is its mole fraction in the solution.

This method enabled accurate determination of activity coefficients for all volatile components in the ternary system.

2.3. UNIFAC Modelling

The UNIFAC model predicts solution properties by representing molecules as collections of functional groups, each characterized by volume (Rk), surface area (Qk), and interaction parameters (akm). In this study, di-(2-ethylhexyl)phosphoric acid comprises CH2, CH3, CH, and HPO4 groups; n-hexane includes CH2 and CH3 groups; benzene contains ACH groups; and toluene consists of ACH and ACCH3 groups. The structural parameters (r, q) for each functional group are standard UNIFAC values obtained from the literature [34,35], where they are derived from the Bondi group contribution method based on molecular geometry and physical properties [36]. Structural parameters (r, q) of groups are listed in Table 1. For the HPO4 group of D2EHPA, the parameters were calculated from the geometry of the D2EHPA dimer using Bondi’s atomic volumes and surfaces, consistent with the known association behavior of D2EHPA in nonpolar solvents [14,25]. Interaction parameters for CH2–HPO4, ACH–HPO4, and ACCH3–HPO4 pairs were determined by modelling, based on experimental data. This allows activity coefficients predictions of all components, including D2EHPA.

Table 1.

Structural parameters (r, q) of the Unifac model.

The activity coefficient (γᵢ) of component i is the product of combinatorial (γᵢᶜᵒᵐᵇ) and residual (γᵢʳᵉˢ) contributions, as shown in Equation (3):

The combinatorial contribution (γᵢᶜᵒᵐᵇ), accounting for molecular size and shape, and the residual contribution (γᵢʳᵉˢ), accounting for energy interactions, are calculated using Equations (4) and (5):

where and are volume and surface fractions,

is the volume factor,

and are the Van der Waals volume and surface area of component i (relative units), nᵢₖ is the number of group k in component i, and Rₖ and Qₖ volumes and surface areas of individual groups.

where Gₖₛ and Gₖᵢ are residual activity coefficients of group k in our solution and in solution of component i respectively, calculated via Equation (6):

where θₘ is the surface fraction of group m, and aₖₘ is the energy interaction parameter (non-zero for CH2–HPO4, ACH–HPO4, and ACH3–HPO4 pairs).

The energy interaction parameters were calculated by minimizing the total deviation between the theoretical and experimental activity coefficients of the volatile components. The objective function, defined as the sum of the natural logarithms of the ratios of experimental (γᵢᵉˣᵖ) to theoretical (γᵢᵗʰᵉᵒʳ) activity coefficients, was minimized according to Equation (7):

where γexper and γteor are experimental and theoretical values of solvent activity coefficients.

This function emphasizes relative deviations, aligning with excess chemical potential differences, unlike the sum-of-squares function, S = ∑(γᵢᵉˣᵖ − γᵢᵗʰᵉᵒʳ)2, which prioritizes absolute differences. For example, an F value of 0.2 for 10 data points indicates an average deviation of 0.02 per point, or approximately 2% error in activity coefficients, as ln(1 ± x) ≈ x for x ≤ 0.1.

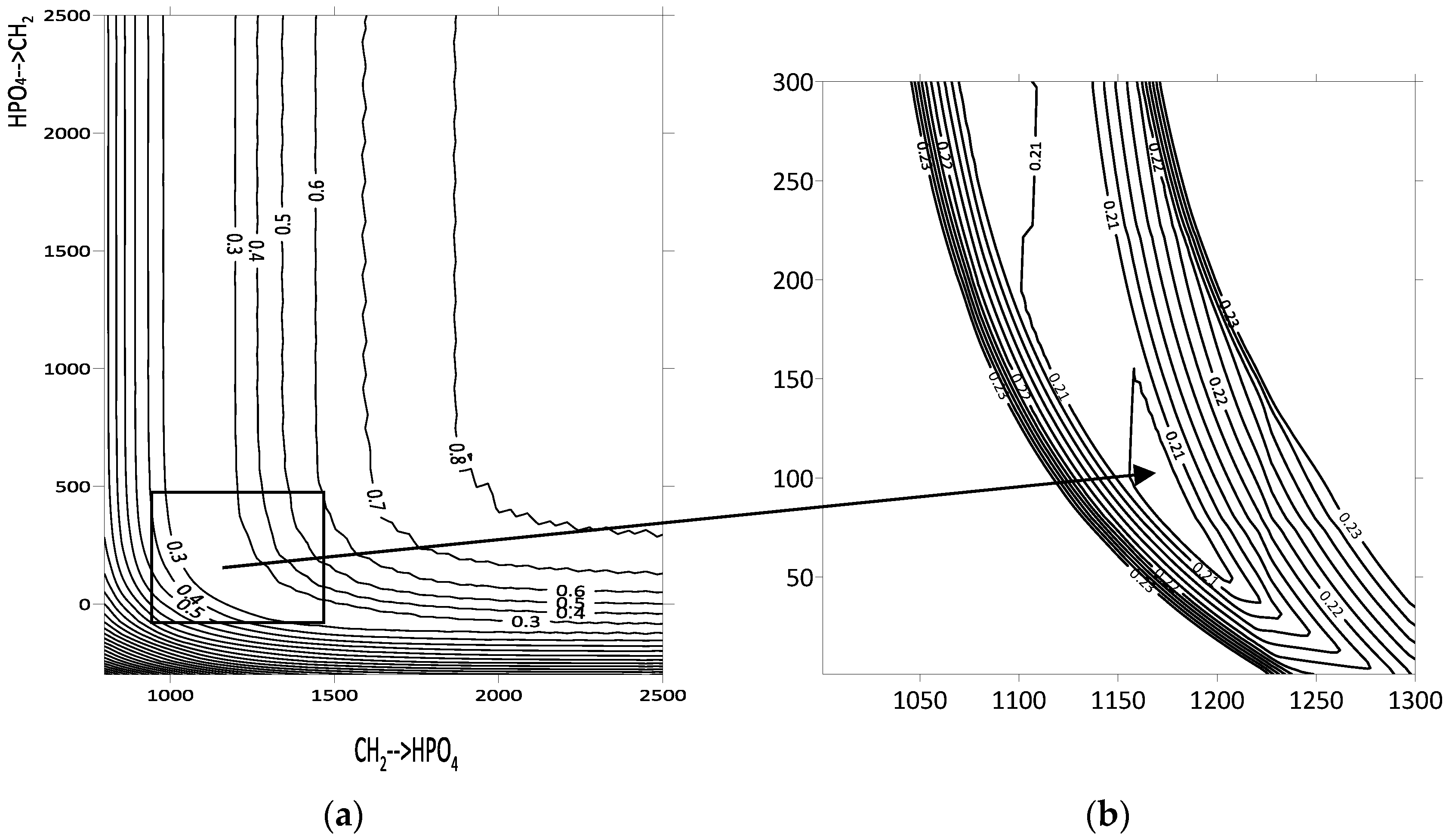

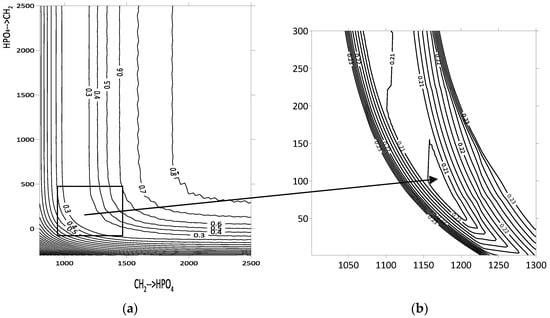

Primary minimization was conducted by evaluating the function F at the nodes of a two-dimensional grid defined by the two energy interaction parameters under investigation (Figure 1a). These parameters ranged from −1000 to 5000 in increments of 10, expressed in units of the gas constant (R = 8.31 J/(mol·K)). The range and step size were adjusted when necessary to refine the calculations. Contour lines representing equal F values were plotted based on the results, providing a visual representation of the parameter space. While this grid-based approach is visually compelling, it may introduce errors in accurately determining the optimal parameters. The dependencies observed were consistent across all three systems studied (hexane–D2EHPA, benzene–D2EHPA, and toluene–D2EHPA), as illustrated for the hexane–D2EHPA system in Figure 1a.

Figure 1.

Contour lines of the function F for the hexane–D2EHPA system: (a) contour lines of relative deviations between theoretical and experimental values of activity coefficients of volatile component; (b) sequential descent method for minimum deviation determination.

The region of minimum F values exhibits an elongated shape along the coordinate axes, resembling a hyperbolic dependence. Consequently, the error in determining one of the two energy interaction parameters is greater than that for the other. Notably, both parameter sets describe the experimental activity coefficients of hexane in the D2EHPA–hexane system with a deviation of no more than 2%, corresponding to an objective function value of F = 0.2 for 14 data points. In order to overcome such errors, the secondary sequential descent method was applied (Figure 1b). For the hexane–D2EHPA system, this algorithm refined the UNIFAC energy interaction parameters for the CH2–HPO4 pair, specifically for CH2→HPO4 from 1144 to 1199 and for HPO4→CH2 from 228 to 54. The modeling of group energy parameters and the issue of error accumulation without applying the sequential descent method are further discussed in Section 4.1.

3. Results

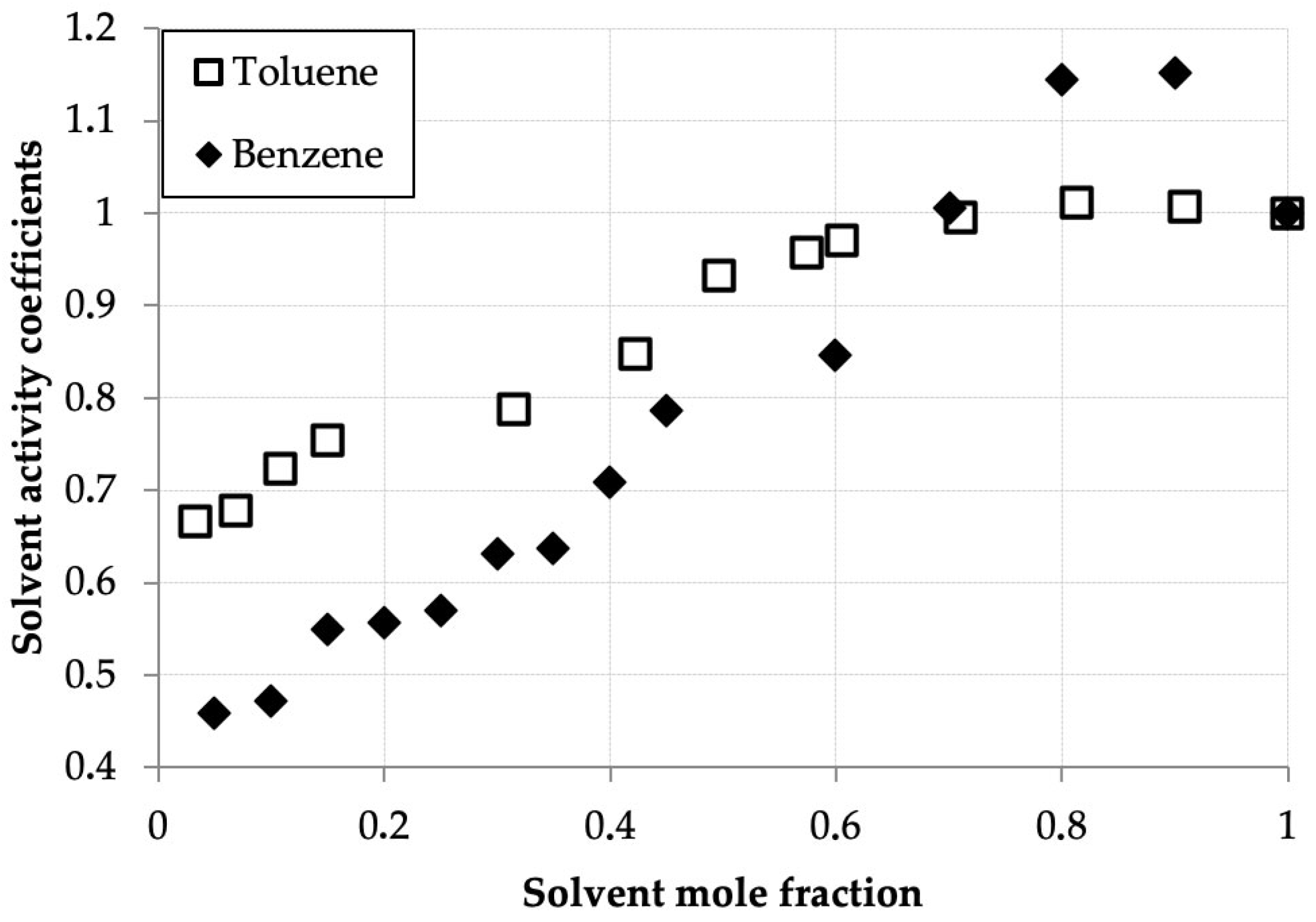

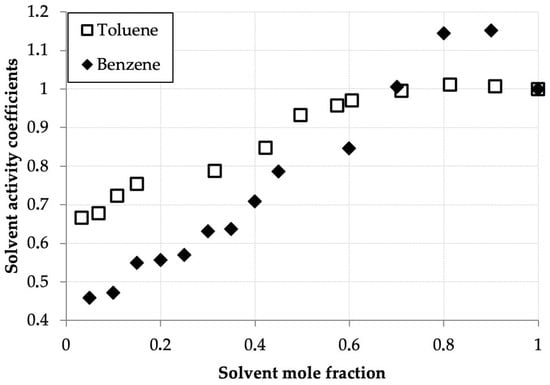

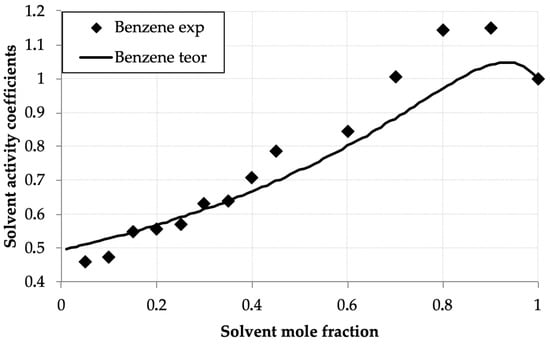

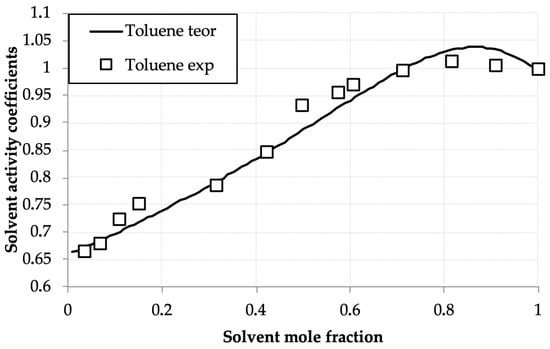

Table 2 and Figure 2 present the measured solvent vapor concentrations and calculated experimental activity coefficient values of benzene and toluene in their binary solutions with D2EHPA as a function of the mole fraction of the volatile component. Both systems exhibit similar behavior, distinct from the hexane–D2EHPA system [1]. In contrast to hexane, for benzene and toluene, the activity coefficient maxima occur at mole fractions, equal 0.9 for benzene and 0.8 for toluene, shifted toward the pure solvents. A key distinction from the hexane system is the lower activity coefficient values (ranging from 0.5 to 0.9) at solvent mole fractions below 0.5. Notably, at equivalent mole fractions in this region, benzene’s activity coefficients are generally lower than those of toluene, with benzene exhibiting a more pronounced maximum. These findings align closely with published data for the toluene–D2EHPA system in [33].

Table 2.

Activity coefficients of benzene and toluene in the solvent–D2EHPA system at 293.0 K.

Figure 2.

Benzene and toluene activity coefficients (γi) versus mole fraction (xi) in D2EHPA solutions at 293.0 K.

The low activity coefficients of benzene and toluene in dilute solutions with D2EHPA can be attributed to their affinity for polar solvents, as the polar D2EHPA molecules effectively retain these compounds in solution. This effect is less pronounced for toluene compared to benzene, which is expected because the addition of a methyl group to toluene’s aromatic ring shifts its properties toward those of alkanes, which exhibit lower solubility in polar solvents. Explaining the presence of activity coefficient maxima in the benzene–D2EHPA and toluene–D2EHPA systems is more challenging, yet these maxima are consistently reproduced in experimental data.

The activity coefficient maxima observed for benzene and toluene arise from the competition between solvent–solvent and solvent–D2EHPA interactions. The shift in the maximum from x ≈ 0.9 (benzene) to x ≈ 0.8 (toluene) is attributed to the presence of a methyl group in toluene, which imparts partial aliphatic character. This results in toluene behaving as an intermediate between benzene and n-hexane, thereby modifying the balance of interactions with D2EHPA and shifting the maximum toward a lower solvent mole fraction. It should be noted that this interpretation, while consistent with the observed trends and molecular reasoning, remains a plausible explanation, as direct measurement of the specific intermolecular interactions was beyond the scope of this thermodynamic study.

4. Discussion

4.1. Determination of UNIFAC Energy Interaction Parameters Using Experimental Data

D2EHPA–benzene and D2EHPA–toluene solutions were modelled as mixtures of CH2, CH3, CH, ACH, ACCH3 and HPO4 groups, with structural parameters listed in Table 1.

In a previous study [1], the energy interaction parameters for the CH2–HPO4 pair were established for the hexane–D2EHPA system. Substituting hexane with benzene introduces the ACH group, for which ACH–HPO4 interaction parameters remain unknown. Using the known CH2–HPO4 parameters, the ACH–HPO4 interaction parameters can be calculated. Similarly, in D2EHPA–toluene solutions, the ACCH3 group is introduced, necessitating the determination of ACCH3–HPO4 interaction parameters based on data from prior hexane and benzene systems.

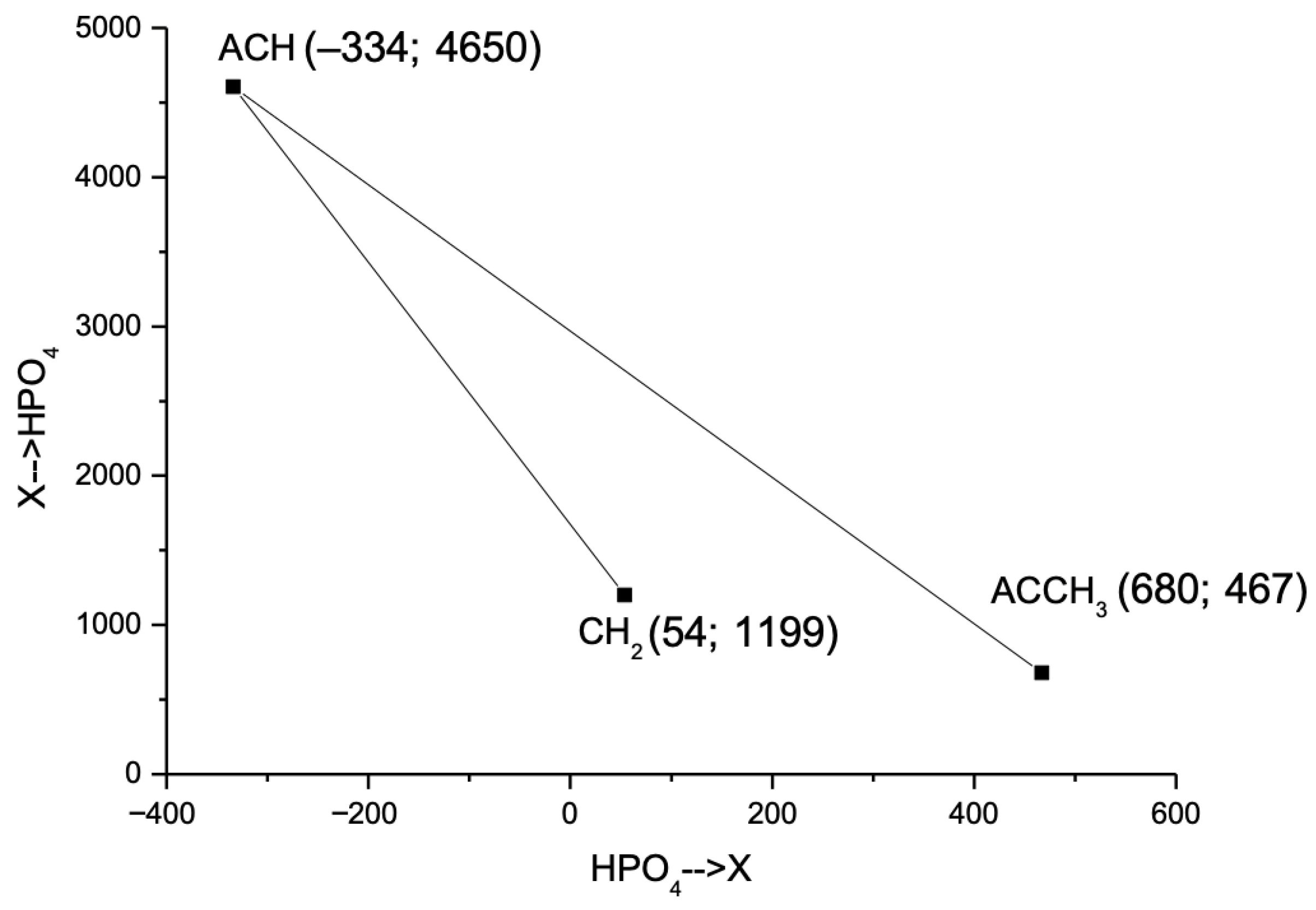

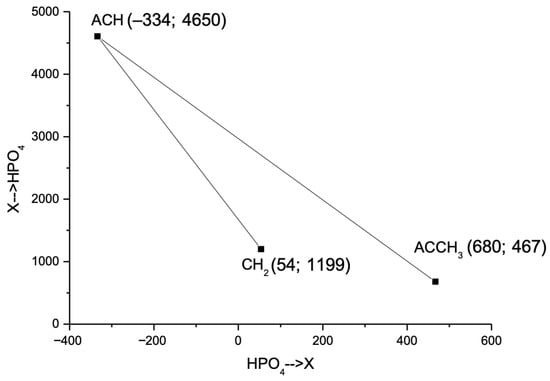

Energy parameters (akm) for ACH–HPO4 and HPO4–ACH, ACCH3–HPO4 and HPO4–ACCH3 interactions were optimized to minimize deviations between experimental and theoretical γi values using Equation (7) and subsequent descent method [37,38]. The UNIFAC energy interaction parameters for benzene and toluene are ACH→HPO4 = 4605, HPO4→ACH = −334, ACCH3→HPO4 = 467, and HPO4→ACCH3 = 680.

The relative positioning of the energy interaction parameters in the parameter space defined by E(X→HPO4) and E(HPO4→X) is illustrated in Figure 3. The ACH group, representing benzene, is positioned at a significant distance from the ACCH3 and CH2 groups, underscoring their distinct interaction characteristics in the UNIFAC model.

Figure 3.

Intergroup energy interaction parameters for X–HPO4 pairs (X = CH2, ACH, ACCH3).

The need to refine the UNIFAC energy interaction parameters emerged during data analysis for the D2EHPA–benzene system, where the interaction parameters for the HPO4–CH2 pair were assumed to be known from prior studies. In the D2EHPA–toluene system, the discrepancy between calculated and experimental activity coefficients increased significantly, resulting in deviations exceeding 20% per experimental data point for the observed dependency. For ternary systems, such as D2EHPA–hexane–benzene, this discrepancy escalated to 30% or greater, highlighting challenges in accurately modeling these complex mixtures.

The observed discrepancies were not attributed to fundamental limitations in the UNIFAC model but rather to inaccuracies in the determination of the energy interaction parameters and the cumulative effect of errors. To accurately model all three systems studied (D2EHPA–hexane, D2EHPA–benzene, and D2EHPA–toluene), the energy interaction parameters must be determined with an accuracy of at least 1%.

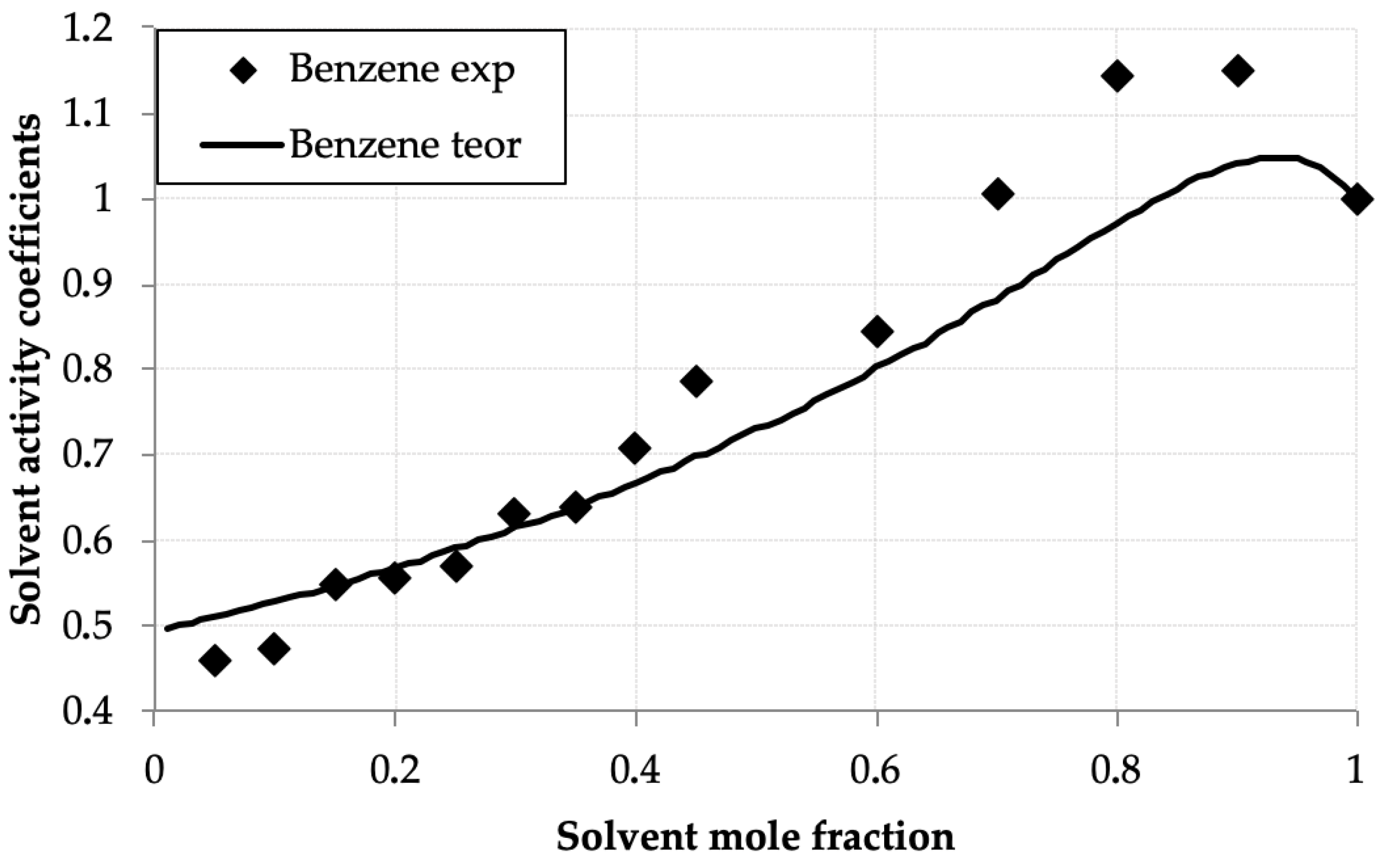

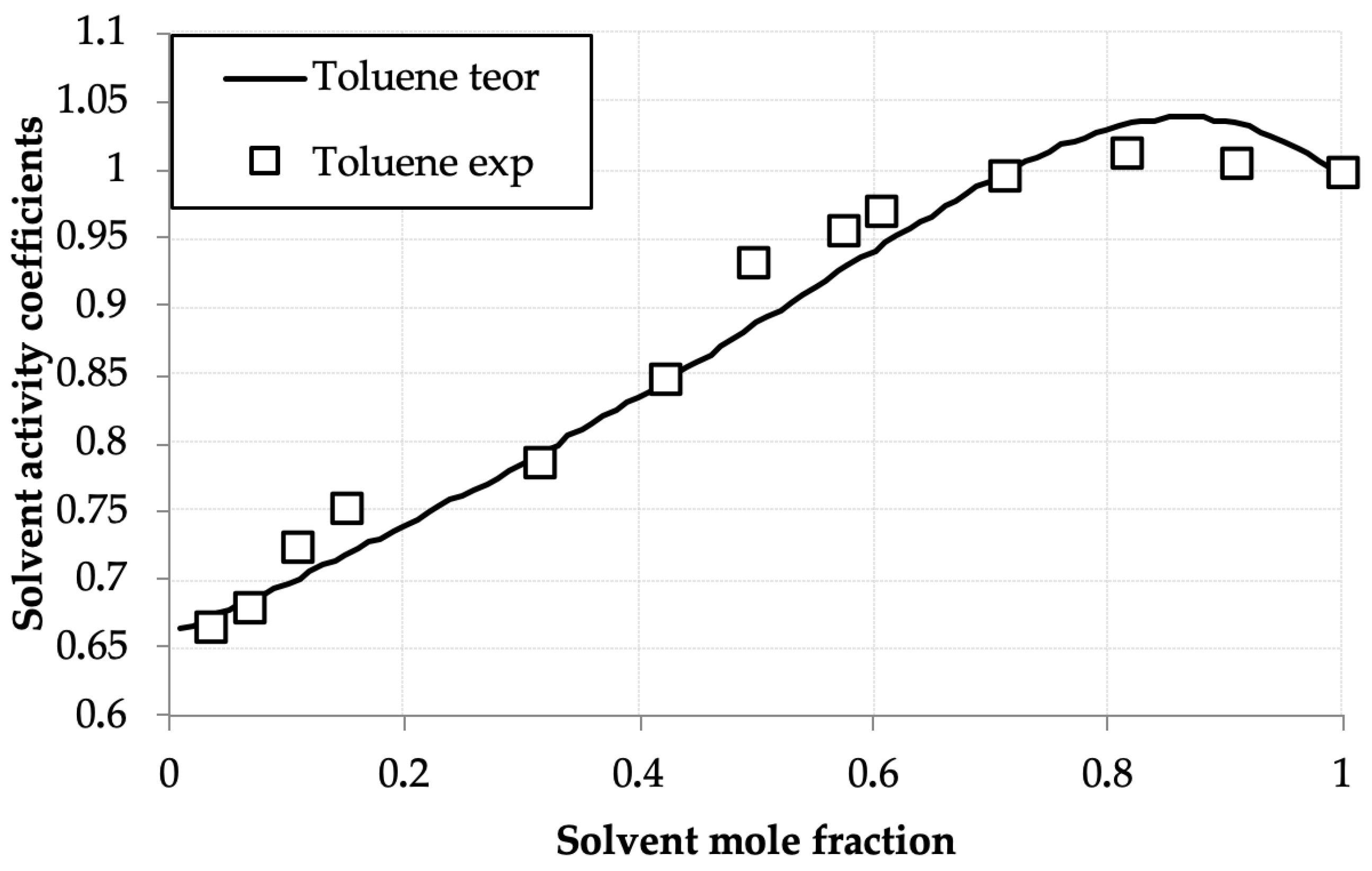

The activity coefficients for the D2EHPA, benzene, and toluene were calculated using the UNIFAC model. Figure 4 and Figure 5 compare experimental γi values with UNIFAC predictions at these parameters, showing strong agreement across compositions. Results of calculations are presented in Table 3

Figure 4.

Benzene activity coefficients (γbenz) versus mole fraction (xbenz) in the benzene—D2EHPA system at 293.0 K: experimental (points) and UNIFAC calculations (line).

Figure 5.

Toluene activity coefficients (γtol) versus mole fraction (xtol) in the toluene—D2EHPA system at 293.0 K: experimental (points) and UNIFAC calculations (line).

Table 3.

UNIFAC-calculated activity coefficients of benzene (γbenz) and toluene (γtol) and D2EHPA (γD2EHPA) at 293.0 K.

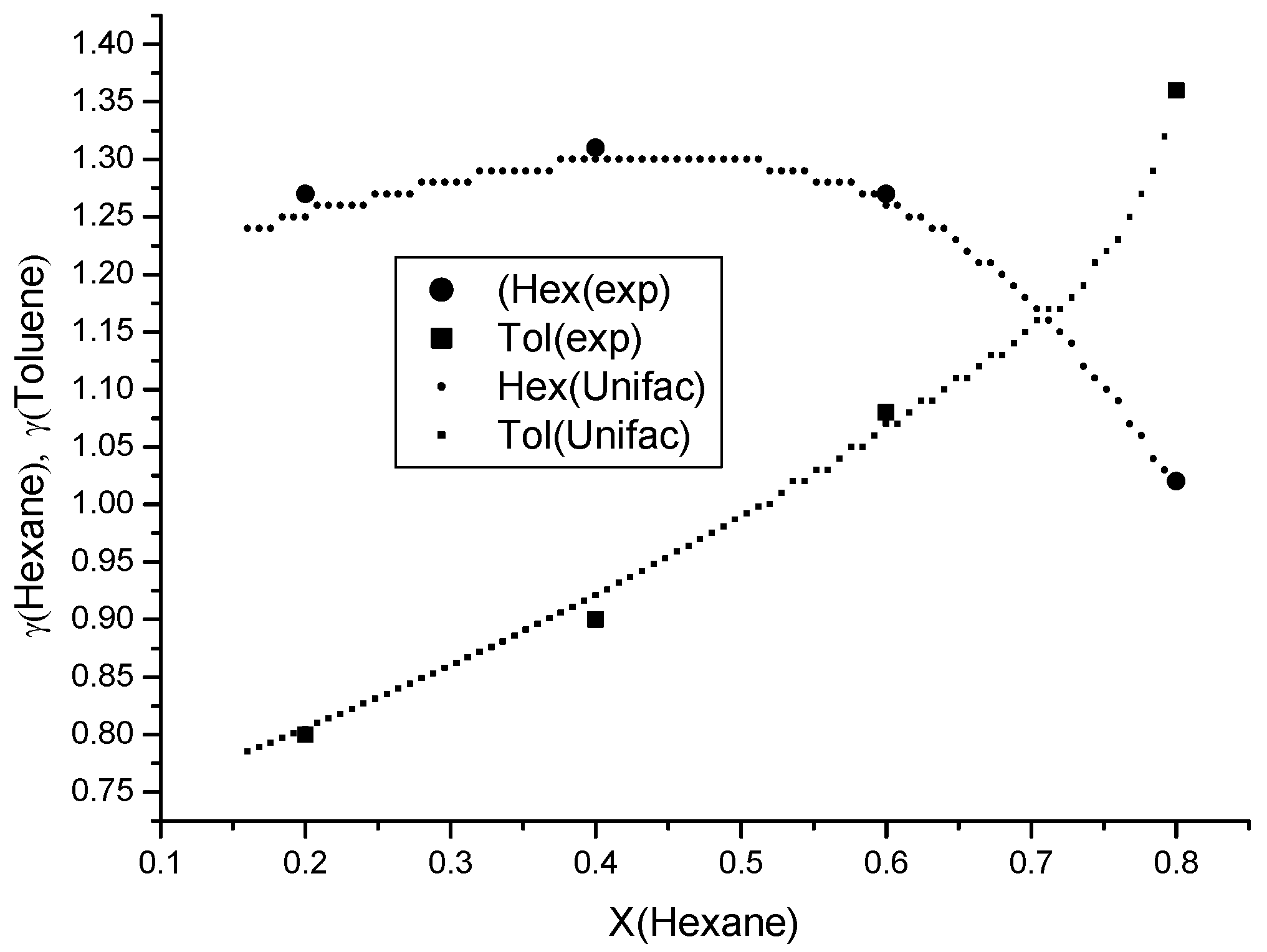

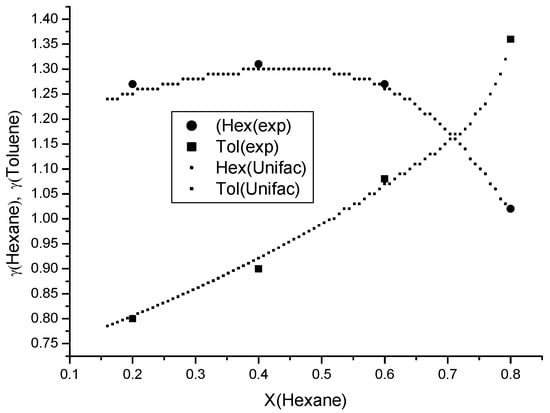

4.2. Validation of the UNIFAC Model for the Ternary Hexane–Toluene–D2EHPA System

To validate the performance of the UNIFAC model by comparing calculated activity coefficients with experimental values, the ternary hexane–toluene–D2EHPA system was investigated, as it comprises only the studied groups (CH2, ACH, ACCH3, HPO4), enabling the model to reliably predict the activity coefficients of both volatile components (n-hexane and toluene).

Despite the high sensitivity of the flame ionization detector (FID) and optimized chromatographic separation conditions, simultaneous measurement of the activity coefficients of both volatile components is often challenging. At varying concentrations of the volatile components in solution, the areas of their chromatographic peaks can differ by a factor of 20 to 100. This significant variation necessitates switching the detector’s sensitivity ranges to accurately determine the concentrations and activity coefficients of each component.

The use of intermediate compositions (interim standard) in place of pure solvents (standard solution) addresses the challenge of varying detector sensitivity for each component in the mixture, such as in the hexane–toluene–D2EHPA ternary system. These interim standard composition is selected to minimize measurement errors in component activity coefficients and must meet two conditions: (1) the detector (FID) maintains identical sensitivity settings during gas chromatography of both standard and interim standard solutions; (2) the chromatographic peak areas of the standard and interim standard solutions differ by less than a factor of 10. Under these conditions, the calculation of activity coefficients, as described by Equation (8), is expressed as follows:

where —solvent concentration in vapour phase (mg/L); the indices 1 and 2 designate sensitivity FID ranges; the index st means standard solution (pure solvent); the index int means interim standard; the ratio is the activity of the volatile component in the intermediate standard ().

To measure the activity coefficients in the ternary n-hexane–toluene–D2EHPA system, a binary solution of toluene in n-hexane was prepared, consisting of 80% n-hexane and 20% toluene by mole fraction. The activity coefficients of n-hexane and toluene were determined using the gas chromatography method outlined previously. Subsequently, D2EHPA was added to the binary mixture, and the activity coefficient measurements were repeated for the resulting ternary composition. A total of four distinct compositions were investigated. The results are presented in Figure 6, demonstrating excellent agreement between the UNIFAC model predictions and experimental data for the ternary system.

Figure 6.

Experimental and UNIFAC–predicted activity coefficients of n-hexane and toluene in the ternary D2EHPA–Toluene–n-Hexane system. Large markers denote experimental values obtained via gas chromatography.

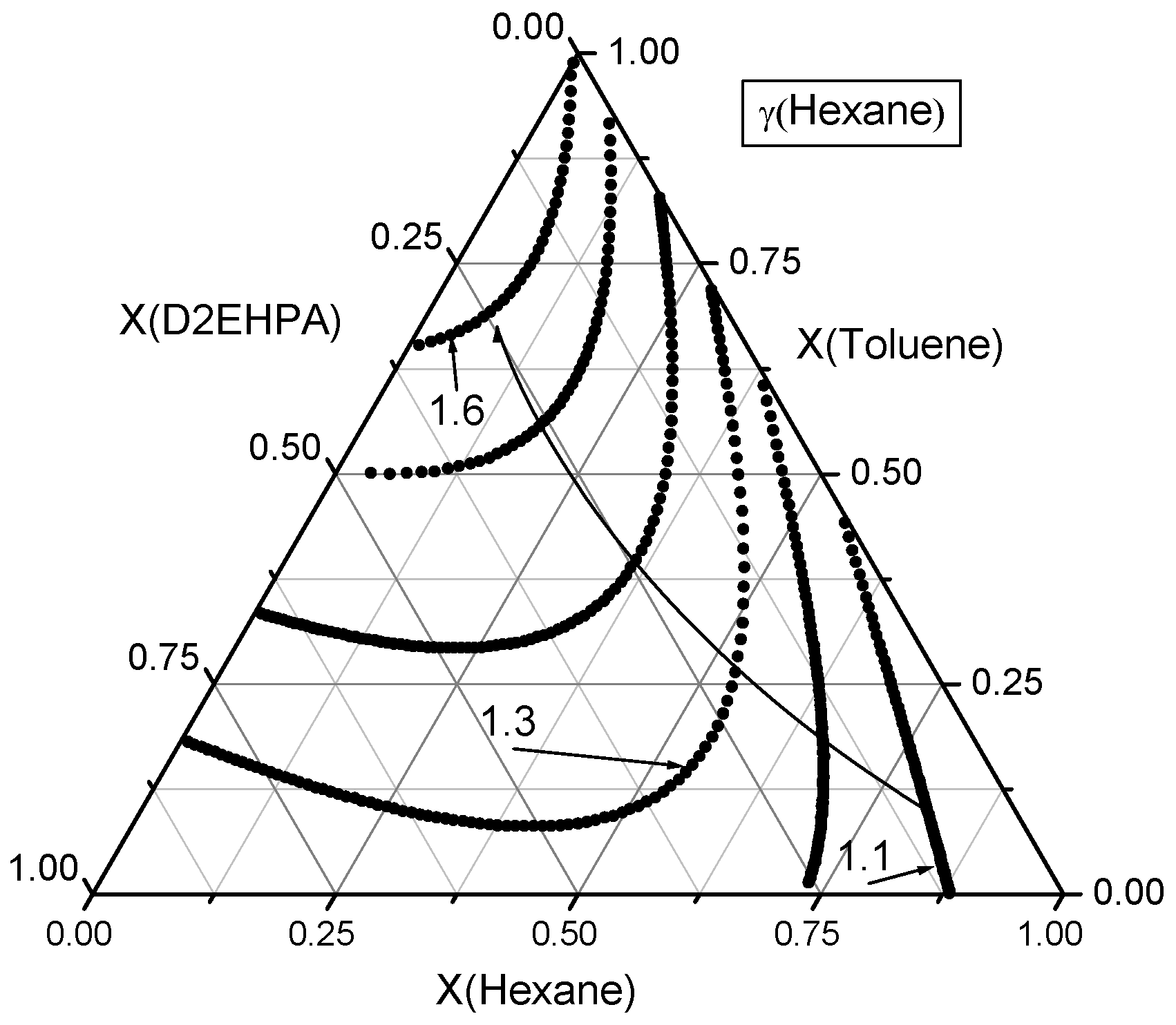

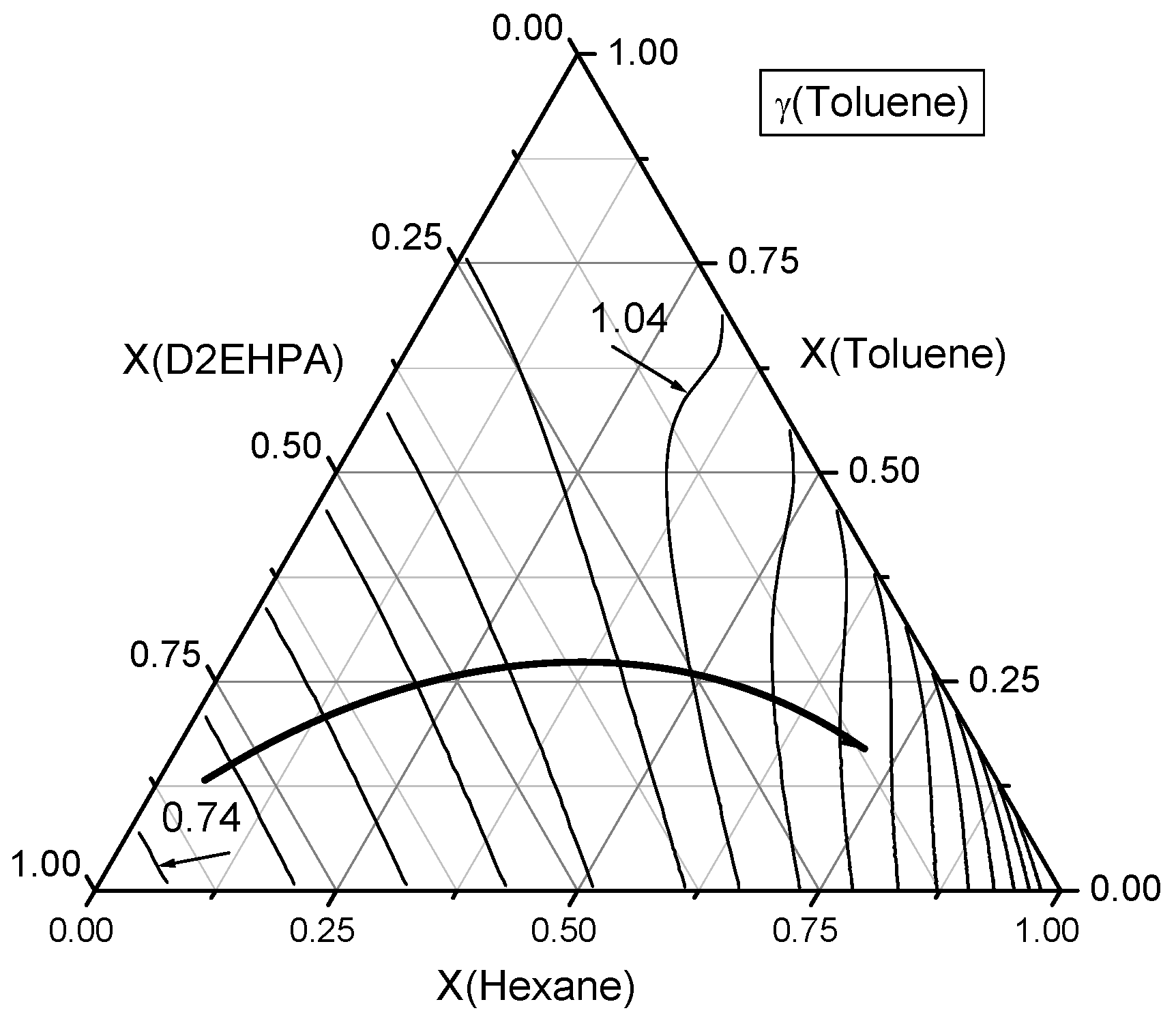

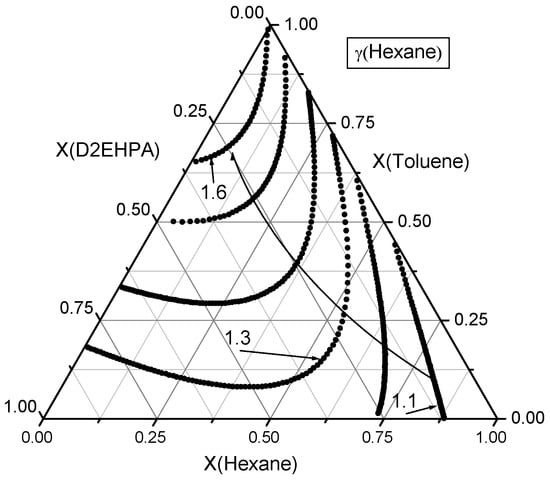

4.3. Modeling of Component Activity Coefficients in Ternary Liquid Systems

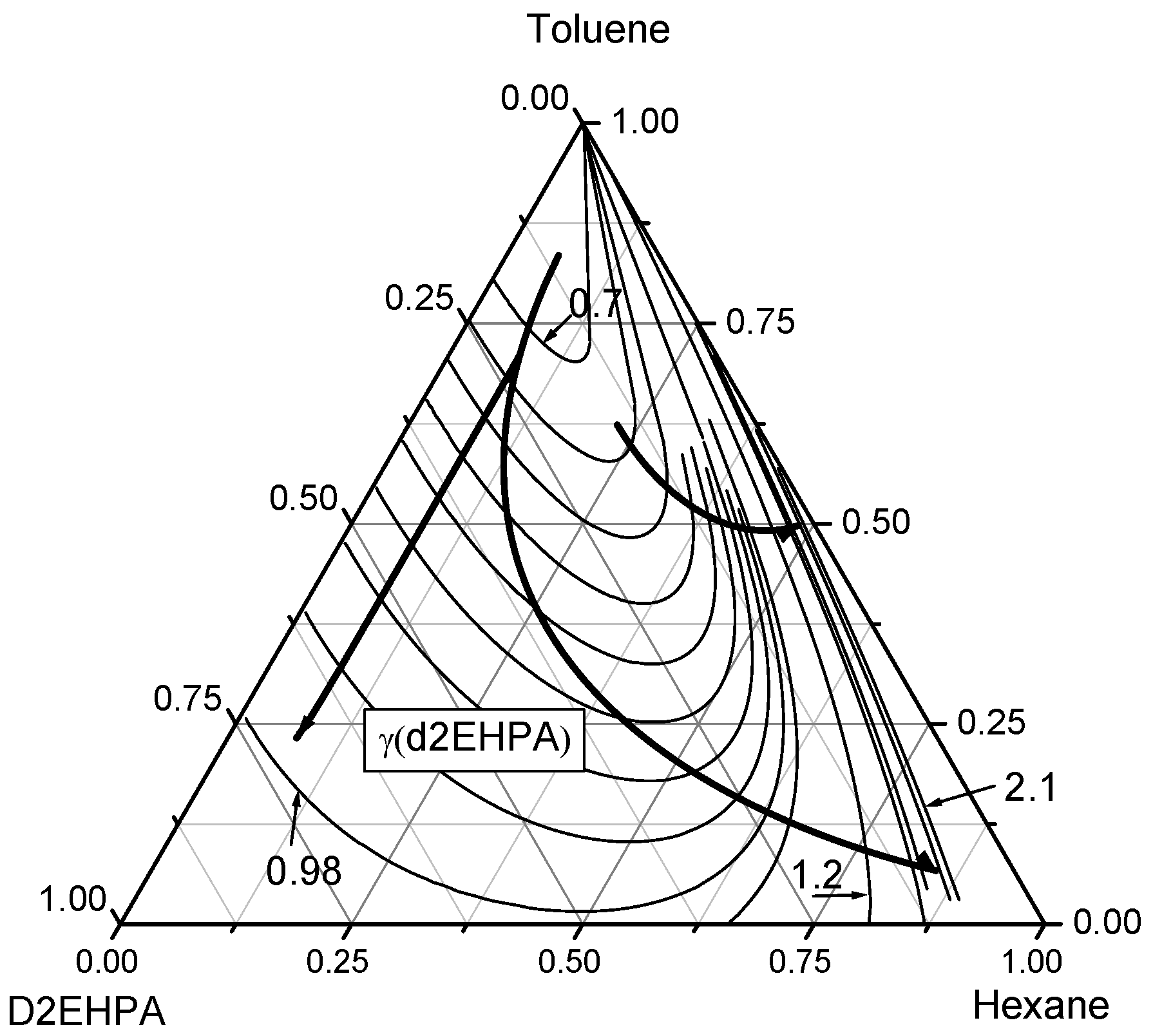

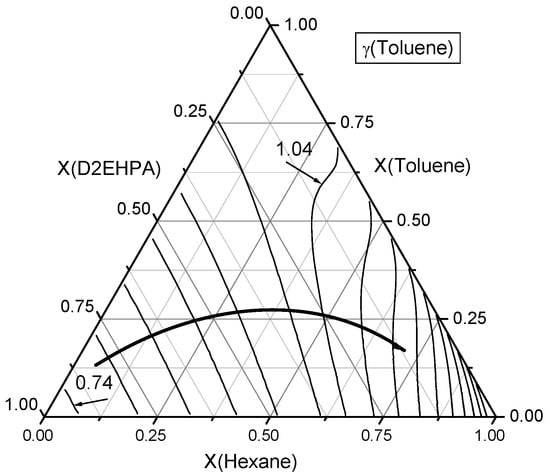

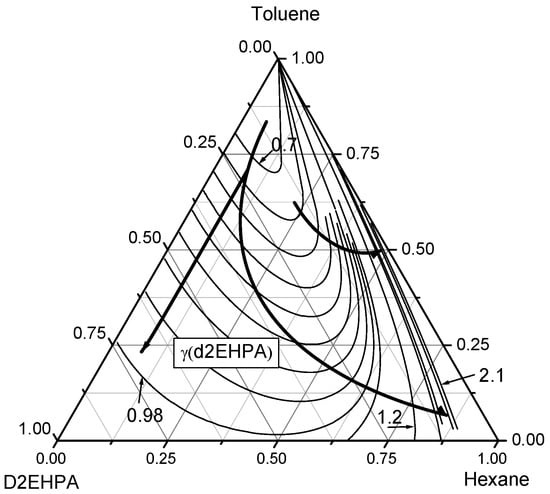

The activity coefficients of the components in the ternary n-hexane–toluene–D2EHPA system were analyzed. The UNIFAC model, utilizing known geometric and energy interaction parameters for groups CH2, ACH, ACCH3, HPO4, enables the calculation of contour lines within the corresponding composition triangle. These ternary diagrams are presented in Figure 7, Figure 8 and Figure 9. Each side of the diagram corresponds to the composition of the binary mixture (n-hexane–toluene, n-hexane–D2EHPA, and toluene–D2EHPA) and each vertex corresponds to a pure component (n-hexane, toluene, or D2EHPA).

Figure 7.

Contour lines of n-hexane activity coefficients in the ternary n-Hexane–Toluene–D2EHPA system. A curved line with an arrow denotes the direction of increasing activity coefficients for n-hexane. The isoclines are plotted with an increment of Δγ = 0.1.

Figure 8.

Contour lines of toluene activity coefficients in the ternary n-Hexane–Toluene–D2EHPA system. A curved line with an arrow denotes the direction of increasing toluene activity coefficients (γtol). The contour lines are plotted with an increment of Δγ = 0.05.

Figure 9.

Contour lines of D2EHPA activity coefficients in the ternary n-Hexane–Toluene–D2EHPA system. The curved lines with arrows denote the directions of increasing D2EHPA activity coefficients (γD2EHPA). The contour lines are plotted with an increment of Δγ = 0.1 near the n-hexane vertex and Δγ = 0.03 when the mole fraction of n-hexane is less than 0.7.

Firstly, the activity coefficients of n-hexane were examined across the composition space, as illustrated in the ternary diagram in Figure 7. The activity coefficient of n-hexane at a mole fraction of is . In the binary n-hexane–D2EHPA mixture, at , the activity coefficient is , while in the binary n-hexane–toluene mixture, at , it is . Thus, starting from n-hexane vertex, at least one composition exists for which activity coefficient of n-hexane is a specified value between 1.2 and 1.6.

In the ternary n-hexane–toluene–D2EHPA system, various compositions with identical n-hexane activity coefficients but differing mole fraction ratios of toluene to D2EHPA define a contour line of constant n-hexane activity coefficients within the triangle. By varying the activity coefficient of n-hexane within its permissible range (e.g., 1.2 to 1.6) at discrete intervals, a family of contour lines representing constant n-hexane activity coefficients can be constructed. These contour lines are illustrated in Figure 7.

The activity coefficient of n-hexane increases smoothly and, in most regions, monotonically as pure n-hexane () is diluted with a binary mixture of toluene and D2EHPA. Notably, the influence of toluene on the activity coefficient of n-hexane is more pronounced than that of D2EHPA.

Secondly, the behavior of toluene in the ternary n-hexane–toluene–D2EHPA system was examined and results are presented in Figure 8. Experimental measurements indicate that the minimum values of toluene activity coefficients occur near the D2EHPA vertex in the ternary composition space. As the composition moves away from the D2EHPA vertex, the activity coefficient of toluene (γtol) increases, reaching unity (γtol = 1) at a D2EHPA:n-hexane mole ratio of approximately 2:3. Notably, the mole fraction of toluene itself has a limited influence on its activity coefficient. Furthermore, a region surrounding this ray exists where the activity coefficient of toluene remains close to 1, largely independent of the toluene mole fraction.

Thirdly, the behavior of D2EHPA activity coefficients in the ternary n-hexane–toluene–D2EHPA system is depicted through contour lines in the ternary diagram shown in Figure 9. The activity coefficients of D2EHPA () increase from the toluene vertex (xtol = 1) toward the D2EHPA vertex ( = 1) and the n-hexane vertex ( = 1). Along the toluene–D2EHPA binary edge, rises from 0.7 to 1.0, a notably smaller increase compared to the toluene–n-hexane binary edge, where ranges from 0.7 to 2.1. As the mole fraction of n-hexane increases along the toluene–n-hexane edge, the rate of increase in diminishes, though the activity coefficient itself continues to rise. The contour lines of converge as they approach the toluene vertex, indicating that the reduction in caused by increasing the toluene mole fraction can be offset by decreasing the mole fraction of D2EHPA. These findings, derived from UNIFAC model predictions and validated by gas chromatography measurements, underscore the non-ideal interactions within the ternary n-Hexane–Toluene–D2EHPA system.

5. Conclusions

The main objective of this study was to implement the proposed methodology for activity coefficients calculations of components of D2EHPA and multicomponent solvent. This approach includes experimental determination of volatile components activity coefficients, calculation of group energy interaction parameters and UNIFAC modeling.

The following steps were implemented to achieve this objective:

- Firstly, initial experimental determination of the activity coefficient for benzene and toluene in binary systems with D2EHPA was performed by gas chromatography at 293.0 K.

- Secondly, the energy interaction parameters were calculated by minimizing the total deviation between the experimental and modeled via UNIFAC activity coefficients using sequential descent method. The resulting values for the energy interaction parameters are: ACH–HPO4 = 4650, HPO4–ACH = −334, ACCH3–HPO4 = 467, and HPO4–ACCH3 = 680. The refined energy interaction parameters for the aliphatic group are CH2–HPO4 = 1199 and HPO4–CH2 = 54.

- Thirdly, the parameterized UNIFAC model was applied to calculate activity coefficient of the components of the ternary n-Hexane–Toluene–D2EHPA system, which contains all previously investigated groups. The calculated values were compared with the experimental data for the same system. The significant difference in saturated vapor pressures of n-hexane and toluene necessitated the application of an interim standard. The implementation of the interim standard improved measurement accuracy in systems where the vapor concentration of analytes varied by more than 20 times. The activity coefficient of the volatile components, as calculated by the model, demonstrated good agreement with experimental data.

- The final step involved calculating the activity coefficient contour lines for each component in the ternary n–Hexane–Toluene–D2EHPA system. The aliphatic n-hexane acts as a strong driver of non-ideality, significantly increasing the activity coefficients of both toluene and D2EHPA, especially the latter. In contrast, toluene is the primary agent affecting n-hexane’s activity, but also stabilizes the activity coefficient of toluene itself and mitigates the strong non-ideal interactions between n-hexane and D2EHPA. This asymmetric interplay underscores the complexity of multicomponent systems and is critical for optimizing processes like liquid–liquid extraction where such mixtures are encountered.

The methodology developed in this study demonstrates broad applicability for investigating the thermodynamic behavior of organic phosphoric acid esters, such as D2EHPA, and aliphatic, aromatic and cyclic hydrocarbons.

The next phase of research will extend this approach to examine a D2EHPA complex coordinated with a rare earth metal cation. Due to the low solubility of such complexes in n-hexane, direct measurement of n-hexane activity coefficients using the previously employed gas chromatography methods may not be feasible. Similarly, this limited solubility precluded the determination of UNIFAC group interaction parameters for the H2O–HPO4 pair specific to D2EHPA in this study. Consequently, a shift from liquid–vapor equilibrium to liquid–liquid equilibrium is proposed, focusing on the measurement of distribution coefficients rather than activity coefficients. The distribution coefficient, defined as the ratio of a component’s activity coefficients in coexisting liquid phases, can be reliably predicted using the UNIFAC model, offering a robust alternative for characterizing the thermodynamic properties of these complexes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, O.V.C. and V.G.P.; methodology, V.G.P.; software, V.G.P.; validation, D.A.A. and V.G.P.; formal analysis, V.G.P. and O.V.C.; investigation, D.A.A. and V.G.P.; data curation, D.A.A. and V.G.P.; writing—original draft preparation, D.A.A. and V.G.P.; writing—review and editing, V.G.P., D.A.A. and O.V.C.; visualization, D.A.A. and V.G.P.; supervision, O.V.C. and V.G.P.; project administration, O.V.C.; funding acquisition, O.V.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was carried out within the state assignment of the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Russian Federation (Research on the processes of integrated subsurface management and deep processing of geo-resources, FSRW-2026-0003).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| D2EHPA | Di-(2-ethylhexyl)phosphoric acid |

| GC | Gas Chromatography |

| FID | Flame Ionization Detector |

References

- Povarov, V.G.; Cheremisina, O.V.; Alferova, D.A.; Fedorov, A.T. Determination of the Activity Coefficients of Components in a Di-2-ethylhexylphosphoric Acid–n-Hexane Binary System Using Gas Chromatography. Chemistry 2025, 7, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakesh, B.; Patel, A.S.; Rana, S.K.; Kumar, T.P. D2EHPA treated resin for the extraction of rare earth elements. Indian Chem. Eng. 2023, 65, 486–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litvinova, T.E.; Gerasev, S.A. Behaviour of cerium (III) phosphate in a carbonate-alkaline medium. J. Min. Inst. 2025, 271, 181–188. [Google Scholar]

- Koo, N.; Kim, B.; Kim, H.-I.; Kwon, K. Extraction Strategies from Black Alloy Leachate: A Comparative Study of Solvent Extractants. Batteries 2024, 10, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathak, P.; Pandey, N. Hydrometallurgical recycling of critical metals from spent Ni-Cd batteries with emphasis on the separation of Cd2+ over Ni2+ using D2EHPA. Geosyst. Eng. 2023, 26, 200–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoninova, N.; Sobenin, A.; Usmanov, A.; Shepel, K. Assessment of the possibility of using iron-magnesium production waste for wastewater treatment from heavy metals (Cd2+, Zn2+, Co2+, Cu2+). J. Min. Inst. 2023, 260, 257–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correa, M.M.J.; Silvas, F.P.C.; Aliprandini, P.; Moraes, V.T.D.; Dreisinger, D.; Espinosa, D.C.R. Separation of Copper from a Leaching Solution of Printed Circuit Boards by Using Solvent Extraction with D2EHPA. Braz. J. Chem. Eng. 2018, 35, 919–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pryakhin, E.I.; Zhdanova, E.Y.; Sharapova, D.M.; Dranova, A.Y. Application of composite film materials for marking engineering products. Chernye Met. 2024, 9, 93–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maksimova, V.; Krasavtseva, E.; Savchenko, Y.; Ikkonen, P.; Elizarova, I.; Masloboev, V.; Makarov, D. Study of the composition and properties of the beneficiation tailings of currently produced loparite ores. J. Min. Inst. 2022, 256, 642–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, G.; Wu, Y.; Chen, D.; Wang, Y.; Qi, T.; Wang, L. Selective removal of iron(III) from highly salted chloride acidic solutions by solvent extraction using di(2-ethylhexyl) phosphate. Front. Chem. Sci. Eng. 2021, 15, 528–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borisova, D.D.; Pashkevich, M.A.; Matveeva, V.A. Using seed materials for the remediation of fluoride-contaminated wastewater. Obogashchenie Rud 2025, 3, 43–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamaruddin, M.A.; Ismail, N.; Osman, U.N.; Alrozi, R. Sustainable separation of Cu(II) and Cd(II) from aqueous solution by using solvent extraction technique with di-2-ethylhexylphosphoric acid (D2EHPA) as carrier: Optimization study. Appl. Water Sci. 2019, 9, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishihama, S.; Hirai, T.; Komasawa, I. Separation and Recovery of Gallium and Indium from Simulated Zinc Refinery Residue by Liquid−Liquid Extraction. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 1999, 38, 1032–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grymonprez, B.; Lommelen, R.; Bussé, J.; Binnemans, K.; Riaño, S. Solubility of di-(2-ethylhexyl)phosphoric acid (D2EHPA) in aqueous electrolyte solutions: Studies relevant to liquid-liquid extraction. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2024, 333, 125846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozhevnikova, A.V.; Milevskii, N.A.; Lobovich, D.V.; Zakhodyaeva, Y.A.; Voshkin, A.A. Deep Eutectic Solvent (TOPO/D2EHPA/Menthol) for Extracting Metals from Synthetic Hydrochloric Acid Leachates of NMC-LTO Batteries. Metals 2024, 14, 1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutskiy, D.S.; Lukyantseva, E.S.; Mikheeva, V.Y.; Grigorieva, L.V. Investigation of the extraction of samarium and gadolinium from leaching solutions of phosphorus-containing raw materials using solid extractants. Arab. J. Basic Appl. Sci. 2023, 30, 68–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Driscoll, D.M.; Liu, H.; Reinhart, B.; Popovs, I.; Bocharova, V.; Jansone-Popova, S.; Jiang, D.; Ivanov, A.S. Noncoordinating Secondary Sphere Ion Modulates Supramolecular Clustering of Lanthanides. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2022, 13, 12076–12081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Liu, Z.; Xia, M.; Song, Y.-F.; Chai, Z.; Wang, D. Biphasic Behaviors of Nd3+ Bound with Cyanex272, Cyanex301, and Cyanex302: A Molecular Dynamics Simulation Study. Inorg. Chem. 2022, 61, 8920–8929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuzmin, K.A.; Ivkin, A.S.; Vovk, M.A.; Rudko, V.A. Pour point depressant efficacy for diesel fuels with different n-paraffin distribution. Fuel 2025, 392, 134885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z.; Dourdain, S.; Pellet-Rostaing, S. Correction to “Understanding the Effect of the Phase Modifier n -Octanol on Extraction, Aggregation, and Third-Phase Appearance in Solvent Extraction”. Langmuir 2021, 37, 2863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kloetzer, L.; Poştaru, M.; Galaction, A.-I.; Blaga, A.C.; Caşcaval, D. Comparative Study on Rosmarinic Acid Separation by Reactive Extraction with Amberlite LA-2 and D2EHPA. 1. Interfacial Reaction Mechanism and Influencing Factors. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2013, 52, 13785–13794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meniai, A.-H.; Newsham, D.M.T.; Khalfaoui, B. Solvent Design for Liquid Extraction Using Calculated Molecular Interaction Parameters. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 1998, 76, 942–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Smolders, S.; Li, X.; Raiguel, S.; Nies, E.; De Vos, D.E.; Binnemans, K. Enhancing Metal Separations by Liquid–Liquid Extraction Using Polar Solvents. Chem. A Eur. J. 2019, 25, 9197–9201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mukhopadhyay, M. A thermodynamic method based upon the theory of regular solutions for selection of solvents and process conditions for aromatics extraction. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 1979, 29, 634–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.-J.; Neuman, R.D. Giant Rodlike Reversed Micelles Formed by Sodium Bis(2-ethylhexyl) Phosphate in n-Heptane. Langmuir 1994, 10, 2553–2558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Wang, C.; Lan, J.; Wu, Q.; Zhao, Y.; Chai, Z.; Nie, C.; Shi, W. Theoretical studies on the complexation of Eu(III) and Am(III) with HDEHP: Structure, bonding nature and stability. Sci. China Chem. 2016, 59, 324–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sethi, S.; Zhang, X.; Sundmacher, K. Process-driven solvent screening for efficient extractive distillation using interpolative rational functions. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2025, 301, 120675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litvinova, T.; Gerasev, S.; Sergeev, V.; Lidanovskiy, E. Rare Earth Metal Ion-Associates in Ln3+—CO32−—H2O System. Metals 2025, 15, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zdretsov, I.M.; Gerasimov, A.M. Green and low-cost synthesis of zeolites from kaolin: A promising technology or a delusion? React. Chem. Eng. 2024, 9, 1994–2027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerber, R.P.; Soares, R.D.P. Prediction of Infinite-Dilution Activity Coefficients Using UNIFAC and COSMO-SAC Variants. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2010, 49, 7488–7496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morachevskii, A.G.; Smirnova, N.A.; Alekseeva, M.V.; Balashova, I.M.; Viktorov, A.I.; Kuranov, G.L.; Piotrovskaya, E.M.; Pukinskii, I.B. Termodinamika Ravnovesiya Zhidkost’-Par [Thermodynamics of Liquid-Vapor Equilibrium]; Khimiya: Leningrad, Russia, 1989; 344p. [Google Scholar]

- Fredenslund, A.; Gmehling, J.; Rasmussen, P. Vapor-Liquid Equilibria Using UNIFAC: A Group Contribution Method; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1977; 380p. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grigorash, D.Y.; Kurdakova, S.V.; Kovalenko, N.A.; Moiseev, A.E.; Uspenskaya, I.A. Experimental study and modeling of vapor–liquid equilibria and excess molar volumes in the di-(2-ethylhexyl)phosphoric acid—Toluene (cyclohexane, hexane, heptane) systems. J. Chem. Thermodyn. 2021, 163, 106608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wittig, R.; Lohmann, J.; Gmehling, J. Vapor−Liquid Equilibria by UNIFAC Group Contribution. 6. Revision and Extension. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2003, 42, 183–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayer, N.; Hasse, H.; Jirasek, F. Modified UNIFAC 2.0-A Group-Contribution Method Completed with Machine Learning. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2025, 64, 10304–10313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bondi, A. Physical Properties of Molecular Crystals, Liquids, and Glasses, 1st ed.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1968; pp. 1–512. [Google Scholar]

- Grabovskii, A.Y.; Mustafaev, A.S.-U.; Stoda, E.V. Setochnyj stabilizator napryazheniya na baze puchkovoj plazmy. TVT 2025, 63, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prishchepa, O.M.; Lutskii, D.S.; Kireev, S.B.; Sinitsa, N.V. Thermodynamic modelling as a basis for forecasting phase states of hydrocarbon fluids at great and super-great depths. J. Min. Inst. 2024, 269, 815–832. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.