Abstract

Resource-constrained IoT and IIoT systems require detection architectures that balance accuracy with energy efficiency, scalability, and contextual awareness. This paper presents a conceptual framework informed by a systematic review of energy-aware detection systems (XDS), unifying intrusion and anomaly detection systems (IDS and ADS) within a single framework. The proposed taxonomy captures six key dimensions: energy-awareness, adaptivity, modularity, offloading support, domain scope, and attack coverage. Applying this framework to the recent literature reveals recurring limitations, including static architectures, limited runtime coordination, and narrow evaluation settings. To address these challenges, we introduce a utility-based decision model for multi-layer task placement, guided by operational metrics such as energy cost, latency, and detection complexity. Unlike review-only studies, this work contributes both a synthesis of current limitations and the design of a novel six-dimensional taxonomy and utility-based layered architecture. The study concludes with future directions that support the development of adaptable, sustainable, and context-aware XDS architectures for heterogeneous environments.

Keywords:

IoT; IIoT; IDs; ADS; energy-aware detection; XDS; green IoT/IIoT; green computing; context-aware security 1. Introduction

The rapid growth of Internet of Things (IoT) and Industrial IoT (IIoT) systems has transformed how critical infrastructure, smart environments, and edge-enabled applications are monitored and managed. However, this transformation introduces serious security challenges, especially in terms of scalability, responsiveness, and energy sustainability. Conventional intrusion detection systems (IDS) and anomaly detection systems (ADS) typically prioritise detection accuracy, often overlooking constraints related to energy consumption, task placement, and real-time adaptability. These constraints are central in distributed, resource-limited deployments.

In response, a growing body of research has proposed energy-aware detection methods that leverage lightweight models [1], decentralised architectures [2], and sustainable deep learning frameworks [3]. While these approaches represent important progress, most remain static, domain-specific, or tied to fixed deployment assumptions. Few systems incorporate adaptive detection complexity, live offloading, or contextual responsiveness into their operational logic.

To streamline discussion and avoid repetition, we use the term XDS as a convenient shorthand to collectively refer to both anomaly detection systems (ADS) and intrusion detection systems (IDS). While ADS approaches typically focus on behavioural analysis [4] and IDS on threat identification and response [5], our analysis considers both under a unified lens. Throughout this paper, XDS simply denotes detection systems that encompass the characteristics and roles of both ADS and IDS.

As this work primarily synthesises and structures existing research rather than reporting new empirical results, the manuscript is positioned as a conceptual and methodological study. In line with this positioning, the study follows a systematic evidence-synthesis protocol guided by PRISMA 2020, ensuring transparency, reproducibility, and a structured basis for the proposed framework.

Prior surveys and taxonomies have contributed valuable insights but remain limited in scope. For example, Roy et al. [1] address green intrusion detection strategies but give limited attention to runtime adaptivity; Arshad et al. [6] discuss energy and privacy but lack multi-layer coordination; Garcia-Teodoro et al. [7] provide an anomaly detection taxonomy focused on techniques rather than operational behaviour; and Khraisat et al. [8] review ML-based IDS in IoT but concentrate mainly on detection models. These frameworks each highlight specific aspects but fall short of integrating behavioural and architectural dimensions in a unified manner. This gap motivates our six-dimensional taxonomy, designed to capture energy-awareness, adaptivity, modularity, offloading support, domain scope, and attack coverage within a single coherent framework.

To address limitations in current detection systems for IoT and IIoT environments, this paper makes two primary contributions. First, we present a structured taxonomy for analysing energy-aware detection systems (XDS), organised around six behavioural and operational dimensions. This taxonomy offers a consistent framework for reviewing and comparing recent approaches. Second, we build on the insights from this taxonomy to propose a layered detection architecture supported by a metric-driven utility model. The model incorporates key operational metrics, such as energy cost, latency, detection complexity, and context relevance into a utility function that supports context-aware and scalable detection across local, edge, and cloud layers. Unlike prior surveys that treat energy and adaptivity as isolated design goals, this paper introduces a unified taxonomy and operational framework that explicitly links detection behaviour to runtime metrics, enabling dynamic decision-making across deployment layers. This paper makes the following key contributions:

- Proposes a six-dimensional taxonomy capturing both behavioural and architectural aspects of energy-aware detection in IoT/IIoT.

- Applies this taxonomy to critically evaluate existing systems, identifying systemic gaps in adaptivity, coordination, and runtime reasoning.

- Introduces a utility-based architecture that formalises task placement using operational metrics aligned with the taxonomy.

The remainder of this paper is organised as follows. Section 2 outlines the literature review protocol and systematic selection process. Section 3 presents the proposed taxonomy and its six dimensions. Section 4 applies this taxonomy to analyse representative XDS studies. Section 5 introduces the layered architecture and metric-driven utility model. Section 6 discusses open challenges and future research directions. Finally, Section 7 concludes the paper.

2. Literature Review Protocol

The review process followed the PRISMA 2020 guidelines to ensure transparency and reproducibility. Our objective was to identify recent energy-aware XDS for IoT and IIoT environments.

2.1. Search Strategy

Searches were conducted between January and September 2025 across the following digital libraries: IEEE Xplore, ACM Digital Library, SpringerLink, ScienceDirect, and MDPI Journals. The query combined keywords such as “IoT”, “IIoT”, “intrusion detection”, “anomaly detection”, “energy-aware”, “green computing”, and “offloading”. Results were limited to peer-reviewed journal and conference papers published from 2020 to 2025.

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Studies were included if they achieved the following: (i) proposed or evaluated an IDS/ADS framework in IoT or IIoT; (ii) addressed energy-awareness, scalability, or adaptive detection; (iii) provided empirical, simulation-based, or testbed evaluation. Studies were excluded if they had the following: (a) were purely review or survey papers; (b) duplicated previously included concepts; (c) did not provide empirical validation; (d) did not address energy-awareness or detection-related objectives.

2.3. Selection Process

In total, 520 records were identified through database and website searches. After removal of 100 duplicates and 70 irrelevant records (e.g., unrelated to IoT security), 350 records remained for screening. Title and abstract screening excluded 200 papers, leaving 150 reports for full-text assessment. Of these, 90 were excluded for reasons such as being review-only, conceptually duplicated, not empirically validated, or not focused on energy-aware detection. A total of 60 studies were retained for detailed analysis.

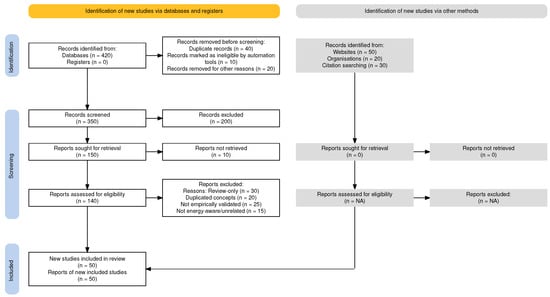

The overall selection process is illustrated in the PRISMA 2020 flow diagram (Figure 1), which summarises the stages of identification, screening, eligibility, and inclusion.

Figure 1.

PRISMA 2020 flow diagram summarising identification (n = 520), screening (n = 350), eligibility (n = 150), and inclusion (n = 60) of studies for the literature review. Counts correspond to the review protocol in Section 2.

2.4. Final Inclusion

The final dataset consisted of 60 primary studies that were mapped against our six-dimensional taxonomy (energy-awareness, adaptivity, modularity, offloading support, domain scope, and attack coverage). These studies form the evidence base for the analysis and framework proposed in this paper. In addition to the systematic PRISMA-based review, a small number of recently published papers (post cut-off) were manually incorporated to ensure that the review reflects the most up-to-date applied works.

3. Behavioural and Architectural Taxonomy for Energy-Aware XDS

Previous taxonomies have typically focused on model characteristics or domain-specific detection goals [1,6,8,9]. Our taxonomy differs by integrating both architectural and behavioural dimensions, providing a more holistic basis for evaluating adaptive and energy-aware XDS in heterogeneous environments.

To support the development and evaluation of scalable, adaptive, and sustainable detection systems, we introduce a behavioural and operational taxonomy tailored to the specific challenges of IoT and IIoT environments. These environments are characterised by constrained computational resources, highly dynamic conditions, and heterogeneous deployment scenarios [10,11], which render traditional performance metrics, such as detection accuracy or throughput, insufficient for capturing system robustness or contextual responsiveness [12].

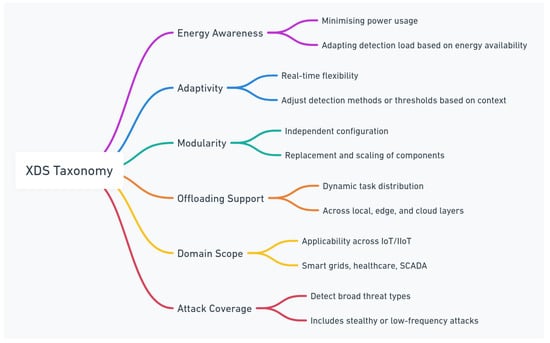

The proposed taxonomy is structured around six foundational dimensions: energy-awareness, adaptivity, modularity, offloading support, domain scope, and attack coverage. These dimensions reflect critical behavioural and architectural characteristics that influence system longevity, responsiveness, and resilience in real-world deployments [1,6,13].

Figure 2 illustrates the conceptual organisation of the taxonomy, showing how each dimension maps to core operational or architectural concerns. To enhance clarity, Table 1 groups these dimensions into two categories: architectural dimensions, which relate to structural flexibility and system integration, and operational dimensions, which describe runtime behaviours such as energy adaptation and threat responsiveness. This layered structure facilitates more coherent comparison across existing detection frameworks, many of which differ significantly in deployment assumptions and evaluation methodologies [14,15].

Figure 2.

Conceptual behavioural and operational dimensions of the proposed XDS taxonomy.

Table 1.

Categorised taxonomy dimensions for evaluating energy-aware detection systems.

This taxonomy provides a consistent basis for examining detection system design choices and highlighting recurring limitations, such as the absence of dynamic control logic [16], narrow domain-specific applicability [17], and weak orchestration across edge, fog, and cloud layers [18]. The six dimensions underpin the comparative analysis presented in Section 4, where they are critically applied to assess the current research landscape.

4. Taxonomy-Informed Literature Analysis

This section delivers a structured literature analysis grounded in the six-dimensional taxonomy introduced earlier. The taxonomy serves as an analytical lens to systematically evaluate representative XDS approaches across key behavioural and operational domains. Each dimension is examined to uncover not only the strengths of current methodologies but also critical design gaps that hinder progress in scalable and energy-aware detection. Particular emphasis is placed on overlooked aspects such as system adaptivity, intelligent task placement, and integrated decision-making logic-elements essential for advancing detection capabilities in dynamic IoT and IIoT environments [19].

4.1. Energy-Awareness

Energy efficiency is widely acknowledged as a fundamental constraint in the design of detection systems for IoT and IIoT environments [1,6]. However, it is often addressed only during the design phase, without being integrated as a dynamic input to influence runtime operations. Most current XDS implementations adopt static energy-saving strategies, such as lightweight classifiers [20,21], decentralised processing [2], or architectural simplifications intended to reduce computational overhead [22]. Although these approaches help minimise baseline power consumption, they lack responsiveness to changing energy conditions in real time.

Many systems rely on pre-selected models known for their low energy consumption, including decision trees, support vector machines, and shallow neural networks [21,22,23]. These models are often chosen based on offline profiling. For example, decision trees have been used to detect EDoS attacks with minimal system strain [21], and memory-efficient classifiers have been applied in SCADA systems to meet energy constraints [22]. Similarly, recursive clustering and lightweight feature selection methods have been proposed to maintain detection performance while lowering energy demands [23]. Still, these approaches remain fixed once deployed and do not account for real-time energy variation.

At the system level, decentralised and federated learning frameworks distribute processing across nodes [14,24,25]. While this helps avoid centralised bottlenecks, it often overlooks energy disparities between devices. For instance, participation in federated learning is typically determined without factoring in battery status [14], and energy-aware optimisation tends to favour system-wide efficiency rather than device-specific conditions [24].

Recent efforts have begun to consider energy as a runtime factor. Ranpara et al. [18] proposed the GreenMU framework with the MUGuard algorithm, which dynamically balances energy consumption and detection performance by adjusting model complexity in response to real-time energy constraints. Their study showed that such adaptive optimisation can reduce energy costs while sustaining high detection quality, demonstrating the potential of “green AI” for scalable IoT and edge deployments.

Jamshidi et al. [26] proposed SecuEdge-DRL, a deep reinforcement learning-based IDS integrated with the MAPE-K self-adaptation cycle, explicitly designed for sustainable IoT. Unlike static IDS approaches, SecuEdge-DRL dynamically adjusts detection and response strategies in real time to balance energy consumption and security. Their Raspberry Pi-based testbed experiments under attacks such as DDoS, DoS Hulk, and port scanning confirmed that the framework maintains high detection accuracy (over 90%) while keeping CPU and energy usage within sustainable limits. This contribution exemplifies how reinforcement learning can operationalise energy-awareness in practice, reinforcing our taxonomy’s emphasis on runtime adaptation as a critical dimension.

Umar et al. [27] further demonstrated that lightweight IDS can be made practical for edge deployments by applying knowledge distillation and quantisation. Their DNN-KDQ framework reduced model size by nearly 90% while retaining 99.4% detection accuracy and achieving inference times of 0.07 ms per sample on Raspberry Pi devices. This shows that energy efficiency can be achieved not only through runtime adaptation but also through model compression, broadening the design space for sustainable IDS in IoT.

In vehicular networks, certain detection frameworks adapt their operation based on available device power [17]. EnergyCIDN goes further by incorporating live energy profiling into collaborative detection workflows [28]. These works represent early steps toward integrating energy feedback into system behaviour but remain isolated within the broader literature.

Insight: In most XDS designs, energy is treated as a static parameter defined at design time, with little consideration for runtime variability. Although recent frameworks such as GreenMU, SecuEdge-DRL, and DNN-KDQ demonstrate that runtime energy-awareness and model compression can be integrated into IDS, these remain isolated implementations rather than a unified design principle. This limits the operational flexibility of detection systems in energy-constrained environments. The literature reveals a significant gap in mechanisms that incorporate live energy profiling into task placement or detection logic. The proposed taxonomy addresses this gap by establishing energy-awareness as a dynamic operational dimension, reinforcing the need for systematic runtime adaptation guided by energy context.

4.2. Adaptivity

Adaptivity in XDS refers to a system’s ability to modify detection strategies in response to evolving threats, changing network behaviours, and dynamic operational contexts [29,30]. In IoT and IIoT environments, where device capabilities, data flows, and topologies frequently change, adaptivity is critical for maintaining detection performance and overall system robustness.

Recent studies have proposed various mechanisms for embedding adaptivity into detection frameworks. Wu et al. [15] introduce a self-improving system that leverages heterogeneous domain adaptation to transfer intrusion knowledge across environments, enabling effective detection even with limited labelled data in the target domain. Deep reinforcement learning (DRL) has also been applied to support dynamic decision-making. Gueriani et al. [31] demonstrate how DRL can adapt detection thresholds and logic in response to network state and adversarial behaviour.

Federated learning offers another pathway for enabling localised adaptivity while preserving data privacy. Rashid et al. [14] propose a decentralised XDS that learns from edge-specific data without exchanging raw inputs. However, many federated systems lack coordinated decision mechanisms, making it difficult to achieve consistent adaptivity across distributed nodes.

Some approaches include context-aware reconfiguration. Rullo et al. [32] design an XDS that adjusts its internal detection logic based on detected anomalies and environmental signals. Although effective in terms of flexibility, such systems often fail to consider resource constraints common in edge deployments. Shen et al. [16] employ ensemble distillation to improve adaptability across heterogeneous and non-independent data distributions. Belarbi et al. [13] explore personalised federated learning updates to maintain local model relevance, but challenges remain regarding convergence and communication overhead.

Hybrid learning strategies have also been introduced to enhance adaptivity. Fenjan et al. [33] combine convolutional neural networks (CNNs), artificial neural networks (ANNs), and multi-layer perceptrons (MLPs) to improve performance across diverse contexts. However, these architectures are typically fixed at deployment and lack mechanisms for runtime reconfiguration. Similarly, CIDIoT [34] presents a privacy-preserving Generative Adversarial Network (GAN)-based system [35] that scales models adaptively, although this adaptivity remains confined to internal components rather than being coordinated across system layers.

Qin et al. [36] proposed DCEDRL, a deep reinforcement learning framework with density clustering and ensemble learning to optimise task offloading in mobile edge computing. While their evaluation focused on general IoT workloads, the adaptive offloading mechanism is directly relevant to IDS/ADS tasks, which share similar latency and resource-sensitivity constraints. This work illustrates how reinforcement learning can support context-aware, adaptive distribution of detection workloads across IoT, edge, and cloud tiers.

Insight: Adaptivity is increasingly acknowledged as essential for effective detection in decentralised and resource-constrained environments. However, it is often implemented as a model-level feature rather than as an integrated system property. A broader view of adaptivity is required, one that embeds responsiveness into the operational logic and dynamically accounts for live system metrics such as energy status, computational load, and environmental context.

4.3. Modularity

Modularity refers to the architectural decomposition of a detection system into discrete, interchangeable, and independently updatable components. This design principle enables scalability, maintainability, and operational flexibility, which are especially important in IoT and IIoT environments where resource constraints and deployment diversity necessitate lightweight and adaptable configurations. Modular architectures facilitate the tailoring of systems to specific use cases and allow updates to be implemented without requiring complete system redesign [37].

Although modularity is widely cited in the literature, its implementation is often limited or superficial. For instance, Atefinia et al. [38] present a modular deep neural network (DNN) architecture where detection tasks are assigned to specialised blocks. While this enhances training efficiency and scalability, it lacks runtime orchestration and does not integrate with broader system-level decision-making.

Layered or hierarchical models are another common approach. Alsoufi et al. [20] structure their detection system into sensing, analysis, and response layers. However, these layers are typically fixed at design time and do not support dynamic reconfiguration or inter-component feedback. Similarly, Illy et al. [39] propose a fog-based ensemble learning approach that distributes detection tasks across network nodes, but the overall architecture remains static during operation.

More granular approaches have also been explored. Cui et al. [40] design a system with dedicated modules for feature extraction, data balancing, and classification, enabling targeted updates to individual components. Chiriac et al. [41] develop a modular Industry 4.0 framework that integrates Nvidia Morpheus with GAN-based modules. Although such designs improve configurability, they still lack runtime orchestration or integration with control frameworks capable of adapting to contextual changes. Ayad et al. [42] extend this line of work with a fog-empowered IDS architecture based on a one-class asymmetric stacked autoencoder. Their design explicitly modularises detection tasks across edge, fog, and cloud layers: edge nodes capture data, fog nodes perform preprocessing and anomaly detection, and the cloud handles model training and updates. Evaluation on BoT-IoT and IoT-23 datasets showed detection accuracy above 97% with minimal false positives, demonstrating that modular distribution can achieve both high performance and deployment flexibility in IoT anomaly detection.

In practice, many XDS implementations remain monolithic, with tightly coupled detection, processing, and response components. This architectural rigidity hampers maintainability, limits component reuse, and restricts the ability to adapt to new operational requirements. Without standardised interfaces or orchestration mechanisms, modularity cannot fully support dynamic reconfiguration or cross-layer task migration.

Insight: Modularity is essential for building sustainable and scalable detection systems, but it must be embedded as a runtime capability rather than a static design choice. Recent fog-empowered approaches show that partial runtime modularity is possible, but these remain isolated efforts rather than standard practice. Future XDS architectures should enable component discovery, activation, and replacement during operation. This requires control frameworks and standardised protocols that support reconfigurable deployments across cloud, fog, and edge environments.

4.4. Offloading Support

Offloading in XDS has evolved from a performance optimisation strategy into a fundamental architectural element. In IoT and IIoT environments, where energy constraints, latency sensitivity, and heterogeneous processing capabilities are common, offloading enables flexible task delegation and enhances system scalability. By distributing detection workloads across local, edge, fog, and cloud layers, systems can reduce bottlenecks, conserve energy, and leverage more powerful resources for complex analytical tasks [43].

Recent research increasingly emphasises context-aware and dynamic offloading strategies. For example, FCAFE-BNET [44] implements a hierarchical allocation approach that accounts for device energy levels, network conditions, and computational capacity. Although this improves system responsiveness, it is still based on static deployment assumptions and lacks runtime coordination mechanisms.

Some studies incorporate offloading directly into detection logic. Simioni et al. [45] integrate early exit points and confidence thresholds within deep learning models, allowing uncertain inferences to be forwarded to more capable nodes. This aligns inference pathways with system constraints and enables energy-efficient resource utilisation.

Reinforcement learning has also been applied to offloading decisions. Zhao et al. [46] frame task placement as a Deep Q-Network problem, using metrics such as energy, latency, and packet loss to inform actions. These approaches introduce adaptive behaviour, though their effectiveness can be limited by slow convergence in rapidly changing environments.

Jamshidi et al. [26] extend this direction by embedding offloading into a reinforcement learning loop. Their SecuEdge-DRL framework dynamically decides which detection and response tasks to keep at the edge and which to offload to the cloud, based on real-time energy and attack conditions. Testbed evaluation on Raspberry Pi devices confirmed that SecuEdge-DRL sustains high accuracy while operating within sustainable energy budgets, showing that IDS offloading can be integrated directly into adaptive system logic.

Complementing cloud-oriented approaches, Umar et al. [27] demonstrated that model compression can eliminate the need for constant offloading. Their DNN-KDQ system applies knowledge distillation and quantisation to deep learning IDS models, reducing their size by nearly 90% while retaining 99% accuracy and achieving inference latencies of 0.07 ms on Raspberry Pi edge devices. This illustrates that efficient local execution can sometimes outperform offloading, highlighting the need for context-sensitive strategies.

Security and trust in offloading have gained attention as well. Liu et al. [47] combine federated learning with blockchain technology to ensure the integrity of offloaded detection tasks. This combination supports secure collaboration and distributed coordination, particularly in heterogeneous and adversarial contexts.

While not always focused exclusively on offloading, optimisation studies such as Zhang et al. [48] highlight the trade-offs between latency, energy consumption, and detection accuracy. Their use of Pareto-based optimisation techniques reinforces the importance of multi-objective approaches that balance conflicting operational goals.

In vehicular networks, Mourad et al. [49] propose a fog-based framework that adapts task delegation based on mobility patterns, residual energy, and link quality. However, the reliance on heuristics limits the generalisability of the approach across diverse use cases.

Insight: Offloading is increasingly central to the scalability and resilience of detection systems. Recent IDS frameworks such as SecuEdge-DRL and DNN-KDQ show that task delegation is no longer an auxiliary optimisation but a core behavioural function, with RL-based orchestration and model compression shaping whether detection is offloaded or executed locally. However, many implementations continue to rely on fixed heuristics. To improve adaptability, future XDS architectures should embed offloading into the system’s behavioural logic, guided by live metrics such as energy levels, inference confidence, network conditions, and detection complexity [43]. Effective orchestration across system layers will be critical for achieving real-time, context-sensitive task distribution.

4.5. Domain Scope

Domain scope refers to the contextual breadth and specialisation of an XDS, including whether it is tailored for a specific environment, such as industrial control systems, vehicular networks, or smart grids, or designed for broader, cross-domain applicability [50]. In heterogeneous IoT deployments, domain scope directly influences system adaptability, detection reliability, and scalability.

Many detection systems exhibit high performance within clearly defined domains but often struggle to generalise beyond their original context. For instance, MTH-IDS [51] demonstrates strong accuracy in both intra-vehicle and external vehicular networks through a multi-tiered model that targets both known and zero-day attacks. However, the architecture is closely aligned with vehicular traffic characteristics, making it less suitable for other domains.

Similar limitations are observed in industrial and cyber-physical environments. Surveys such as [52,53] report that many detection solutions face challenges related to real-time performance, constrained bandwidth, and limited labelled data—conditions frequently encountered in operational technology deployments. These constraints highlight the need for lightweight, explainable, and interoperable detection frameworks capable of adapting to changing conditions.

To improve generalisability, several studies have explored transfer learning. Yan et al. [54] provide a comprehensive overview of deep transfer learning methods for time-series anomaly detection. While these approaches reduce dependency on domain-specific data and support adaptation, many focus on basic parameter transfer and overlook more sophisticated strategies such as adversarial learning or feature alignment.

Few-shot learning is gaining traction as a viable alternative for enabling cross-domain adaptability. Shi et al. [55] utilise a model-agnostic meta-learning (MAML) framework that allows rapid adjustment to new environments with minimal training data. This approach improves flexibility and data efficiency, making it particularly relevant for real-world IoT scenarios that demand quick and resource-aware adaptation.

Insight: Domain scope is not merely a deployment constraint, but a critical factor shaping how detection systems balance flexibility, performance, and resource efficiency. Although domain-specific models often achieve high accuracy within their intended settings, their utility is limited in more diverse environments. Future research should focus on integrating cross-domain learning capabilities, including few-shot and adversarial transfer methods, within modular and context-aware XDS architectures.

4.6. Attack Coverage

Attack coverage refers to the range and complexity of threats a detection system can identify, from high-volume attacks such as floods and scans to stealthier threats like spoofing, reconnaissance, or protocol abuse. In complex IoT environments with diverse and evolving threat surfaces, broad and adaptable attack coverage is essential for system resilience [56].

Traditional detection approaches often rely on signature-based methods, which are effective against known threats but struggle with novel or evolving attacks. Anomaly-based techniques offer greater adaptability but typically suffer from high false positive rates, particularly in dynamic networks [57]. Hybrid approaches aim to combine the strengths of both, yet their integration does not always translate to improved generalisability, especially when training data is limited or biased [58].

Recent studies have attempted to improve coverage using richer datasets. For example, IoTGEM [58] introduces a structured feature pipeline that achieves robust performance against both known and previously unseen threats. Still, detection consistency varies across attack types, revealing weaknesses in generalisation. To better understand this, Table 2 maps attack categories to detection challenges such as feature visibility, temporal complexity, and similarity to benign traffic.

Table 2.

Empirical mapping of attack types to detection challenges (based on IoT-NID dataset [59]).

The table shows that volumetric attacks like ACK- and SYN-floods are easily detected due to their high visibility and predictable patterns. By contrast, stealthy attacks, such as ARP spoofing or OS discovery, are harder to detect because they closely resemble legitimate traffic or occur sporadically over time. Brute-force attacks also present challenges due to their similarity to normal authentication attempts.

Ayad et al. [42] demonstrated broad coverage with a fog-empowered IDS using a one-class asymmetric stacked autoencoder. Tested on BoT-IoT and IoT-23, it addressed attacks such as DoS/DDoS, scanning, Mirai, and spoofing, aligning with ATT&CK tactics like Discovery, Impact, Execution, and Persistence. Achieving F1-scores above 97%, it shows that modular edge–fog–cloud architectures can combine high accuracy with wide tactic coverage.

Another challenge is that many evaluations rely on clean, isolated datasets that do not reflect real-world operational noise or concurrent threat activity. As noted by Yan et al. [54], this creates a mismatch between reported performance and actual deployment reliability.

Emerging methods such as continual learning and meta-learning aim to improve generalisability. Deep transfer learning supports the reuse of learned features across domains, reducing retraining costs. However, domain shifts and limited labelled data remain persistent barriers to broader coverage.

Insight: Expanding attack coverage demands more than detecting a larger set of threats. It requires aligning detection strategies with the behavioural complexity of real-world attacks. Fog-empowered and modular detection approaches show that broad ATT&CK tactic coverage is achievable, but current efforts remain dataset-specific rather than standardised across deployments. Robust performance across dynamic environments is best supported through approaches that emphasise feature generalisation, continual learning, and evaluation against diverse attack scenarios.

To contextualise the literature review, Table 3 provides a comparative summary of recent XDS studies evaluated across key dimensions: energy-awareness, adaptivity, modularity, scalability, deployment context, and evaluation methodology. Several consistent patterns and limitations emerge. While energy-efficient and adaptive mechanisms are increasingly explored, particularly through federated learning and lightweight models, modularity and scalability remain underdeveloped. The absence of modular architectures reduces system flexibility and limits reuse, especially in heterogeneous, edge-enabled environments.

Table 3.

Comparative mapping of XDS studies to evaluation criteria.

Evaluation practices are also inconsistent. Many studies rely on simulations or isolated scenarios, with limited use of benchmark datasets or real-world deployments. This undermines both generalisability and reproducibility. Despite frequent claims of high accuracy, the lack of standardised evaluation procedures and operational insights makes meaningful comparison across studies difficult.

5. Proposed Architecture and Metric-Driven Utility Model

To operationalise the insights derived from our taxonomy and address the multifaceted constraints of detection in IoT and IIoT systems, we propose a layered XDS architecture supported by a metric-driven decision framework. The rationale for adopting a three-tier structure of local, edge/fog, and cloud is grounded in the need to balance trade-offs between energy consumption, latency, processing complexity, and contextual relevance. These layers reflect increasing capabilities and resource availability while accommodating the heterogeneous and distributed nature of modern IoT deployments [43].

Local detection prioritises immediacy and energy efficiency, typically operating on resource-constrained devices with limited memory and compute power. Edge/Fog detection offers a compromise between responsiveness and analytical depth, suitable for scenarios requiring low-latency decisions and moderate processing capacity. Cloud detection supports complex analysis and global correlation but is subject to higher communication overhead and latency.

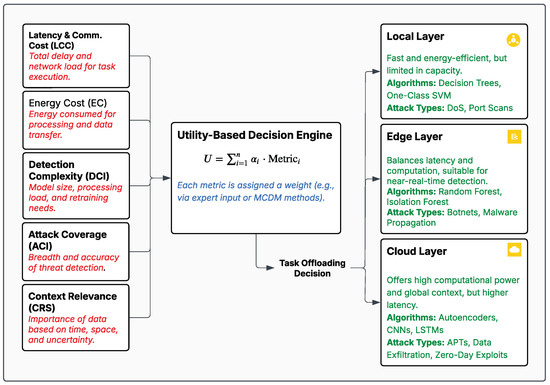

Task placement across these layers is directed by a composite utility function (U), (Equation (1)) that dynamically evaluates system conditions using a set of formalised metrics. Each metric is explicitly linked to the dimensions defined in our taxonomy, ensuring that placement decisions are both theoretically grounded and contextually appropriate.

Figure 3 illustrates how the proposed operational metrics are integrated into a utility-based decision engine. Each metric contributes to the selection logic, guiding adaptive task offloading based on energy, latency, complexity, context, and detection capability across system layers.

Figure 3.

Utility-based architecture for adaptive task placement in layered XDS environments.

5.1. Operational Metrics and Their Taxonomic Foundations

To support adaptive task placement across the local, edge, and cloud layers, we introduce five operational metrics derived from the six-dimensional taxonomy outlined in Section 3. Each metric quantifies a specific behavioural or operational factor central to scalable, energy-aware detection in IoT and IIoT environments. These metrics act as core inputs to the utility-based decision engine.

- Latency and Communication Cost (LCC): Rooted in the offloading support and adaptivity dimensions, LCC captures end-to-end delay and network burden. It combines communication overhead with inference latency to assess whether a task can be completed within system-defined time constraints. Prior work highlights the criticality of LCC in SCADA [60] and vehicular systems [61].

- Energy Cost (EC): Anchored in the energy-awareness dimension, EC quantifies the energy consumed for preprocessing, transmission, and inference. Studies such as [24] have demonstrated how offloading strategies and lightweight models can significantly reduce EC in constrained environments.

- Detection Complexity Index (DCI): Aligned with modularity and adaptivity, DCI reflects the computational burden of model inference and maintenance. This includes architectural complexity, memory footprint, and retraining overhead [14,56].

- Attack Coverage Index (ACI): Reflecting the attack coverage and modularity dimensions, ACI measures the breadth of threats a model can detect, its accuracy per class, and generalisability to emerging or obfuscated attacks [62,63].

- Context Relevance Score (CRS): CRS addresses the domain scope and adaptivity dimensions. It evaluates how spatial, temporal, and semantic context influence the urgency or appropriateness of a detection task. High CRS values prioritise escalation to higher tiers [64,65].

5.2. Utility-Based Decision Function

These five metrics are integrated into a composite utility function U, which evaluates the suitability of each detection tier under current system conditions:

Each represents the weight assigned to its respective metric, allowing system designers to prioritise different trade-offs based on operational needs. LCC, EC, and DCI represent undesirable overheads. Lower values of these metrics indicate better performance. To reflect this in the utility function (where higher scores are preferred), we use their inverse forms (e.g., ), ensuring that a reduction in cost leads to an increase in utility.

In contrast, higher values of ACI and CRS represent improved coverage and contextual fit. These are used in their original form, contributing positively to the overall utility without inversion.

Here, each is a tunable weight that reflects the relative importance of its corresponding metric. Weights can be configured through a variety of strategies, depending on system constraints and operational goals:

- Expert-driven prioritisation: Weights may be manually assigned based on mission-specific needs. For example, energy might be prioritised in battery-limited nodes [6].

- Historical profiling: System logs and past performance can inform empirical tuning, aligning decisions with known trade-offs [34].

- Multi-objective optimisation: Classical methods such as weighted sum scalarisation or Pareto front analysis allow for balancing conflicting objectives [66,67].

- Hybrid subjective–objective methods: Entropy weighting [68] and TOPSIS [69] integrate human judgement with system telemetry for more nuanced weighting.

- Learning-based adaptation: Reinforcement learning and Bayesian optimisation approaches enable real-time tuning of weights based on observed utility [15,31].

In practice, these strategies imply that weights can operate in either a static mode (expert- or policy-defined) or an adaptive mode (continuously adjusted at runtime). This distinction clarifies how the utility model can balance stability with responsiveness depending on deployment requirements.

Operational Example: In a smart traffic monitoring system, weights are set as (LCC), (EC), (DCI), (ACI), and (CRS). Roadside cameras with low energy use ( J) but high data rates ( ms) prioritise edge processing to reduce delay. For vehicles with limited compute () and high attack exposure (), detection tasks are escalated to fog servers. During accidents where context is critical (), tasks are further escalated to the cloud for cross-site correlation. This scenario shows how the utility balances latency, energy, complexity, coverage, and context in real time.

To validate the practical applicability of the proposed utility-based XDS architecture, we plan to implement and test the model in a real-world IoT/IIoT deployment environment. This implementation will involve profiling detection models and evaluating operational metrics such as latency, energy consumption, and context relevance under realistic workloads. The aim is to assess how effectively the utility-based decision function supports dynamic task placement, enhances system responsiveness, and minimises resource usage in heterogeneous and constrained settings. These empirical insights will help refine the architecture and inform its broader applicability.

Recent works provide guidance on how such validation can be systematically undertaken. Mahadevappa et al. [70] validate edge-centric IDS frameworks through security and performance benchmarking. Jamshidi et al. [26] demonstrate empirical evaluation of reinforcement learning-based IDS on constrained IoT hardware, while Jamshidi et al. [71] propose a broader methodology for assessing detection systems in edge environments. Inspired by these studies, we propose three principles for empirical validation of our taxonomy: (i) apply it in controlled testbeds with realistic IoT/IIoT workloads; (ii) quantify trade-offs between detection accuracy, energy use, and latency; (iii) demonstrate cross-domain applicability by testing across heterogeneous environments such as smart grids, vehicular IoT, and healthcare IoT. These principles outline a clear pathway for future validation efforts.

6. Future Research Directions and Technical Challenges in XDS

This section outlines key research gaps and open challenges identified through the taxonomy-informed analysis of energy-aware detection systems (XDS) for IoT and IIoT environments. The goal is to provide a roadmap for future investigations that address critical limitations and support the development of scalable, resilient, and context-aware security frameworks.

6.1. Dynamic Energy-Aware Decision-Making

Although energy efficiency is widely acknowledged as a design goal, most detection systems continue to treat it as a static constraint [1,21]. Future research should advance models that incorporate energy as a dynamic parameter within detection-related decision processes. This includes live energy profiling, adaptive workload reallocation, and energy-informed task placement at runtime [18,28]. Such dynamic integration is essential for sustaining long-term detection capabilities in resource-constrained environments. By aligning detection strategies with real-time energy conditions, systems can maintain operational continuity and reduce the risk of degraded monitoring coverage over time.

6.2. Unified Adaptive Control Frameworks

Current approaches to adaptivity in detection systems are often fragmented and confined to model-specific adjustments [15,31]. There is a growing need for unified control frameworks that can dynamically coordinate detection behaviour in response to evolving threat patterns, system workload, and contextual variations. Such frameworks should enable the selective adjustment of detection parameters, retraining schedules, or model configurations based on runtime observations. Reinforcement learning and online learning present promising methods for this purpose [31,46], particularly when extended to support multi-objective optimisation and real-time adaptation across heterogeneous and distributed layers. By embedding adaptivity into a centralised control logic, detection systems can remain effective under variable conditions without compromising responsiveness or coverage.

6.3. Operational Modularity and Reconfigurability

Modularity is often addressed at the design stage, with limited emphasis on runtime orchestration or reconfiguration [38,41]. Future detection architectures should support dynamic module replacement, scaling, and adaptation in response to changes in system state or threat landscape. This is particularly relevant in heterogeneous IoT and IIoT environments, where detection requirements may vary significantly across devices and operational contexts. Service-oriented and container-based designs, coupled with standardised interfaces, can facilitate seamless integration and runtime flexibility across edge, fog, and cloud layers [40]. Enhancing modularity in this way allows detection systems to remain responsive, context-aware, and resilient as operational demands evolve.

6.4. Behaviour-Aware Offloading Strategies

Offloading in current detection systems is often reactive and guided by static heuristics [44,49]. Future research should advance proactive, learning-driven offloading strategies that consider detection confidence, behavioural profiles, energy constraints, and network variability [45,46]. To ensure reliable and secure operations, offloading decisions must also incorporate trust metrics and security posture assessments of remote execution environments. This is particularly important when delegating detection tasks across untrusted or distributed layers in IoT and IIoT settings. Hybrid frameworks that integrate detection logic with orchestration layers are essential to enable security-aware, context-sensitive task placement [47], ensuring both the integrity of detection processes and the trustworthiness of execution endpoints.

6.5. Cross-Domain Generalisability

Many detection models remain highly specialised, exhibiting limited transferability beyond their original deployment context [51,52]. Future research should prioritise cross-domain learning strategies, such as meta-learning, few-shot learning, and adversarial domain adaptation that enable detection systems to operate effectively across heterogeneous and evolving IoT and IIoT environments [54,55]. Enhancing generalisability is essential for maintaining consistent threat detection in settings where data distributions, device characteristics, and operational behaviours may vary widely. Adaptive detection models capable of transferring knowledge between domains can reduce retraining overheads and improve resilience against unseen or domain-shifted threats.

6.6. Holistic Attack Coverage and Evaluation

Existing detection research frequently targets isolated or well-characterised attack types, often relying on idealised datasets with limited contextual variability [56,57]. To support robust and trustworthy detection, future work must adopt broader evaluation frameworks that incorporate multi-attack scenarios, diverse deployment contexts, and realistic threat models [54,58]. Emphasis should be placed on detecting stealthy, low-frequency, and evolving threats that may evade conventional techniques. This requires the integration of continual learning, adversarial robustness, and adaptive detection mechanisms capable of sustaining performance under adversarial conditions and environmental drift.

6.7. Evaluation Benchmarks and Reproducibility

The absence of consistent benchmarking standards continues to hinder progress in the development and validation of detection systems [14,24]. To enable fair and meaningful comparison across studies, future work must prioritise the creation of shared datasets, reproducible simulation environments, and standardised evaluation metrics tailored to detection performance. Open-source frameworks and well-defined testing pipelines are essential for assessing key attributes such as detection accuracy, adaptability, resource consumption, and robustness to adversarial behaviours. Establishing reproducibility as a foundational principle will support the development of trustworthy and generalisable detection approaches across diverse IoT and IIoT deployments.

6.8. Industrial Adoption Barriers

In addition to technical challenges, future research must also address industrial adoption barriers. Deployment complexity in constrained OT environments often restricts the feasibility of advanced IDS/ADS frameworks. Federated learning introduces concerns of trust, accountability, and governance across heterogeneous stakeholders [72]. Moreover, legacy OT (Operational Technology) systems remain prevalent in many industrial settings, creating integration difficulties and security risks when retrofitting them into IIoT environments [73,74]. Overcoming these barriers is critical for bridging the gap between research prototypes and sustainable real-world deployments.

The utility-based detection model proposed in this study directly addresses several of the identified gaps by integrating context-aware offloading, adaptive control mechanisms, and multi-dimensional metric evaluation within a layered architectural framework. As a practical next step, implementing and validating this model in real-world or controlled testbed environments will be critical to assess its feasibility, performance characteristics, and operational viability.

Addressing the outlined challenges calls for a transition from static, domain-specific detection solutions toward dynamic, modular, and context-responsive architectures. The integration of adaptive control logic, security-aware offloading strategies, and reconfigurable modular components is central to developing sustainable and scalable detection systems. Such architectures will be essential for meeting the evolving demands of energy efficiency, situational awareness, and threat resilience across diverse IoT and IIoT ecosystems.

7. Conclusions

This paper examined the limitations of current energy-aware detection systems (XDS) in IoT and IIoT environments and proposed a structured approach to improve their scalability, adaptability, and sustainability. We introduced a behavioural and operational taxonomy covering six key dimensions: energy-awareness, adaptivity, modularity, offloading support, domain scope, and attack coverage. This taxonomy provided a consistent basis for analysing recent literature and highlighting recurring challenges in detection system design.

Building on these insights, we proposed a layered XDS architecture supported by a utility-based decision model. This model integrates multiple operational metrics, such as latency, energy cost, detection complexity, and context relevance, to enable dynamic task placement across local, edge, and cloud layers. Each metric is explicitly aligned with the taxonomy, ensuring that system decisions are both context-sensitive and practically grounded.

While this study introduces a conceptual framework, it has not yet been empirically validated. Its ultimate aim is real-world applicability, and future work will focus on implementing and testing the proposed model in controlled IoT/IIoT testbed environments. This will enable systematic evaluation of detection accuracy, energy efficiency, and responsiveness under realistic operational conditions.

We therefore position the taxonomy and utility-based model as a structured foundation rather than a fully realised solution, providing a clear reference point for subsequent empirical research and practical deployments in IoT and IIoT security.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, A.J. and H.A.; methodology, A.J.; software, A.J.; validation, A.J., H.A., and A.H.; formal analysis, A.J.; investigation, A.J.; resources, A.J.; data curation, A.J.; writing—original draft, A.J.; writing—review and editing, A.J., H.A., A.H., and H.A.I.; visualisation, A.J.; supervision, A.J.; project administration, A.J.; model design and taxonomy, A.J. and H.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created. The datasets used in this study are publicly available and cited in the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Roy, S.; Sankaran, S.; Zeng, M. Green intrusion detection systems: A comprehensive review and directions. Sensors 2024, 24, 5516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioannou, I.; Nagaradjane, P.; Angin, P.; Balasubramanian, P.; Kavitha, K.J.; Murugan, P.; Vassiliou, V. GEMLIDS-MIOT: A green effective machine learning intrusion detection system based on federated learning for medical IoT network security hardening. Comput. Commun. 2024, 218, 209–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez, Á.L.P.; Maimó, L.F.; Celdrán, A.H.; Clemente, F.J.G. SUSAN: A Deep Learning based anomaly detection framework for sustainable industry. Sustain. Comput. Inform. Syst. 2023, 37, 100842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samariya, D.; Thakkar, A. A comprehensive survey of anomaly detection algorithms. Ann. Data Sci. 2023, 10, 829–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, D.; Jiang, M. A survey on data-driven network intrusion detection. ACM Comput. Surv. (CSUR) 2021, 54, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arshad, J.; Azad, M.A.; Amad, R.; Salah, K.; Alazab, M.; Iqbal, R. A review of performance, energy and privacy of intrusion detection systems for IoT. Electronics 2020, 9, 629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Teodoro, P.; Diaz-Verdejo, J.; Maciá-Fernández, G.; Vázquez, E. Anomaly-based network intrusion detection: Techniques, systems and challenges. Comput. Secur. 2009, 28, 18–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khraisat, A.; Alazab, A. A critical review of intrusion detection systems in the internet of things: Techniques, deployment strategy, validation strategy, attacks, public datasets and challenges. Cybersecurity 2021, 4, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, A.; Ranga, V. Machine learning based intrusion detection systems for IoT applications. Wirel. Pers. Commun. 2020, 111, 2287–2310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alrawais, A.; Alhothaily, A.; Hu, C.; Cheng, X. Fog computing for the Internet of Things: Security and privacy issues. IEEE Internet Comput. 2017, 21, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butun, I.; Osterberg, P.; Song, H. Security of the Internet of Things: Vulnerabilities, attacks, and countermeasures. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutorials 2019, 22, 616–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Liu, Y.; Chen, T.; Tong, Y. Federated machine learning: Concept and applications. ACM Trans. Intell. Syst. Technol. 2020, 10, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belarbi, O.; Spyridopoulos, T.; Anthi, E.; Mavromatis, I.; Carnelli, P.; Khan, A. Federated deep learning for intrusion detection in IoT networks. In Proceedings of the GLOBECOM 2023—2023 IEEE Global Communications Conference, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 4–8 December 2023; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 237–242. [Google Scholar]

- Rashid, M.M.; Khan, S.U.; Eusufzai, F.; Redwan, M.A.; Sabuj, S.R.; Elsharief, M. A federated learning-based approach for improving intrusion detection in industrial internet of things networks. Network 2023, 3, 158–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Wang, Y.; Dai, H.; Xu, C.; Kent, K.B. Adaptive bi-recommendation and self-improving network for heterogeneous domain adaptation-assisted IoT intrusion detection. IEEE Internet Things J. 2023, 10, 13205–13220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Yang, W.; Chu, Z.; Fan, J.; Niyato, D.; Lam, K.Y. Effective intrusion detection in heterogeneous Internet-of-Things networks via ensemble knowledge distillation-based federated learning. In Proceedings of the ICC 2024-IEEE International Conference on Communications, Denver, CO, USA, 9–13 June 2024; pp. 2034–2039. [Google Scholar]

- Lihua, L. Energy-Aware Intrusion Detection Model for Internet of Vehicles Using Machine Learning Methods. Wirel. Commun. Mob. Comput. 2022, 2022, 9865549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranpara, R.; Alsalman, O.; Kumar, O.P.; Patel, S.K. A simulation-driven computational framework for adaptive energy-efficient optimization in machine learning-based intrusion detection systems. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 13376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandola, V.; Banerjee, A.; Kumar, V. Anomaly detection: A survey. ACM Comput. Surv. (CSUR) 2009, 41, 1–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsoufi, M.A.; Siraj, M.M.; Ghaleb, F.A.; Al-Razgan, M.; Al-Asaly, M.S.; Alfakih, T.; Saeed, F. Anomaly-based intrusion detection model using deep learning for IoT Networks. Comput. Model. Eng. Sci. 2024, 141, 823–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldhyani, T.H.; Alkahtani, H. Artificial intelligence algorithm-based economic denial of sustainability attack detection systems: Cloud computing environments. Sensors 2022, 22, 4685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahakonye, L.A.C.; Mukisa, K.J.; Nwakanma, C.I.; Kim, D.S. Eco-Secure SCADA: Towards Machine Learning Reliability for Green Cybersecurity. In Proceedings of the 2025 International Conference on Artificial Intelligence in Information and Communication (ICAIIC), Fukuoka, Japan, 18–21 February 2025; pp. 337–341. [Google Scholar]

- Almalawi, A. A Lightweight Intrusion Detection System for Internet of Things: Clustering and Monte Carlo Cross-Entropy Approach. Sensors 2025, 25, 2235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahmati, M. Energy-aware federated learning for secure edge computing in 5G-enabled IoT networks. J. Electr. Syst. Inf. Technol. 2025, 12, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enam, M.M.R.; Joarder, M.M.I.; Taimun, M.T.Y.; Sharan, S.M.I. Framework for Smart SCADA Systems: Integrating Cloud Computing, IIoT, and Cybersecurity for Enhanced Industrial Automation. Saudi J. Eng. Technol. 2025, 10, 152–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamshidi, S.; Amirnia, A.; Nikanjam, A.; Nafi, K.W.; Khomh, F.; Keivanpour, S. Self-adaptive cyber defense for sustainable IoT: A DRL-based IDS optimizing security and energy efficiency. J. Netw. Comput. Appl. 2025, 239, 104176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umar, H.G.A.; Yasmeen, I.; Aoun, M.; Mazhar, T.; Khan, M.A.; Jaghdam, I.H.; Hamam, H. Energy-efficient deep learning-based intrusion detection system for edge computing: A novel DNN-KDQ model. J. Cloud Comput. 2025, 14, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Rosenberg, P.; Glisby, M.; Han, M. EnergyCIDN: Enhanced energy-aware challenge-based collaborative intrusion detection in internet of things. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Algorithms and Architectures for Parallel Processing, Copenhagen, Denmark, 10–12 October 2022; pp. 293–312. [Google Scholar]

- Ragsdale, D.J.; Carver, C.; Humphries, J.W.; Pooch, U.W. Adaptation techniques for intrusion detection and intrusion response systems. In Proceedings of the SMC 2000 Conference Proceedings, 2000 IEEE International Conference on Systems, Man and Cybernetics, ’Cybernetics Evolving to Systems, Humans, Organizations, and Their Complex Interactions’, Nashville, TN, USA, 8–11 October 2000; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2000; Volume 4, pp. 2344–2349. [Google Scholar]

- Elsayed, M.A.; Wrana, M.; Mansour, Z.; Lounis, K.; Ding, S.H.; Zulkernine, M. AdaptIDS: Adaptive intrusion detection for mission-critical aerospace vehicles. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2022, 23, 23459–23473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gueriani, A.; Kheddar, H.; Mazari, A.C. Deep reinforcement learning for intrusion detection in IoT: A survey. In Proceedings of the 2023 2nd International Conference on Electronics, Energy and Measurement (IC2EM), Medea, Algeria, 28–30 November 2023; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Rullo, A.; Midi, D.; Mudjerikar, A.; Bertino, E. Kalis2. 0—A SECaaS-Based Context-Aware Self-Adaptive Intrusion Detection System for IoT. IEEE Internet Things J. 2023, 11, 12579–12601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenjan, A.; Almashhadany, M.T.M.; Ahmed, S.R.; Fadel, H.A.; Sekhar, R.; Shah, P.; Veena, B. Adaptive Intrusion Detection System Using Deep Learning for Network Security. In Proceedings of the Cognitive Models and Artificial Intelligence Conference, Istanbul, Turkiye, 25–26 May 2024; pp. 279–284. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, W.; Zhao, H.; Shi, H. Privacy-preserving collaborative intrusion detection in edge of internet of things: A robust and efficient deep generative learning approach. IEEE Internet Things J. 2023, 11, 15704–15722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodfellow, I.; Pouget-Abadie, J.; Mirza, M.; Xu, B.; Warde-Farley, D.; Ozair, S.; Courville, A.; Bengio, Y. Generative adversarial networks. Commun. ACM 2020, 63, 139–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y.; Chen, J.; Jin, L.; Yao, R.; Gong, Z. Task offloading optimization in mobile edge computing based on a deep reinforcement learning algorithm using density clustering and ensemble learning. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrivastwa, R.R.; Bouakka, Z.; Perianin, T.; Dislaire, F.; Gaudron, T.; Souissi, Y.; Karray, K.; Guilley, S. An embedded AI-based smart intrusion detection system for edge-to-cloud systems. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Cryptography, Codes and Cyber Security, Casablanca, Morocco, 26–28 October 2022; pp. 20–39. [Google Scholar]

- Atefinia, R.; Ahmadi, M. Network intrusion detection using multi-architectural modular deep neural network. J. Supercomput. 2021, 77, 3571–3593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Illy, P.; Kaddoum, G.; Moreira, C.M.; Kaur, K.; Garg, S. Securing fog-to-things environment using intrusion detection system based on ensemble learning. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE wireless communications and networking conference (WCNC), Marrakesh, Morocco, 15–18 April 2019; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, J.; Zong, L.; Xie, J.; Tang, M. A novel multi-module integrated intrusion detection system for high-dimensional imbalanced data. Appl. Intell. 2023, 53, 272–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiriac, B.N.; Anton, F.D.; Ioniță, A.D.; Vasilică, B.V. A Modular AI-Driven Intrusion Detection System for Network Traffic Monitoring in Industry 4.0, Using Nvidia Morpheus and Generative Adversarial Networks. Sensors 2024, 25, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayad, A.G.; Sakr, N.A.; Hikal, N.A. Fog-empowered anomaly detection in IoT networks using one-class asymmetric stacked autoencoder. Clust. Comput. 2025, 28, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaddoa, A.; Sakellari, G.; Panaousis, E.; Loukas, G.; Sarigiannidis, P.G. Dynamic decision support for resource offloading in heterogeneous Internet of Things environments. Simul. Model. Pract. Theory 2020, 101, 102019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selamnia, A.; Brik, B.; Bouabdallah, A. Dynamic hierarchical intrusion detection task offloading in IoT edge networks. Softw. Pract. Exp. 2023, 53, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simioni, J.A.; Viegas, E.K.; Santin, A.O.; de Matos, E. An Energy-Efficient Intrusion Detection Offloading Based on DNN for Edge Computing. IEEE Internet Things J. 2025, 12, 20326–20342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Huang, G.; Jiang, J.; Gao, L.; Li, M. Task offloading of cooperative intrusion detection system based on Deep Q Network in mobile edge computing. Expert Syst. Appl. 2022, 206, 117860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, P.; Zhou, X.; Shao, X.; Pu, G.; Zhang, Y. Blockchain and federated learning for collaborative intrusion detection in vehicular edge computing. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2021, 70, 6073–6084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Gong, B.; Waqas, M.; Tu, S.; Chen, S. Many-objective optimization based intrusion detection for in-vehicle network security. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2023, 24, 15051–15065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mourad, A.; Tout, H.; Wahab, O.A.; Otrok, H.; Dbouk, T. Ad hoc vehicular fog enabling cooperative low-latency intrusion detection. IEEE Internet Things J. 2020, 8, 829–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, N.W.; Alshehri, M.S.; Khan, M.A.; Almakdi, S.; Moradpoor, N.; Alazeb, A.; Ullah, S.; Naz, N.; Ahmad, J. A hybrid deep learning-based intrusion detection system for IoT networks. Math. Biosci. Eng. 2023, 20, 13491–13520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Moubayed, A.; Shami, A. MTH-IDS: A multitiered hybrid intrusion detection system for internet of vehicles. IEEE Internet Things J. 2021, 9, 616–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holdbrook, R.; Odeyomi, O.; Yi, S.; Roy, K. Network-Based Intrusion Detection for Industrial and Robotics Systems: A Comprehensive Survey. Electronics 2024, 13, 4440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heartfield, R.; Loukas, G.; Bezemskij, A.; Panaousis, E. Self-configurable cyber-physical intrusion detection for smart homes using reinforcement learning. IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensics Secur. 2020, 16, 1720–1735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, P.; Abdulkadir, A.; Luley, P.P.; Rosenthal, M.; Schatte, G.A.; Grewe, B.F.; Stadelmann, T. A comprehensive survey of deep transfer learning for anomaly detection in industrial time series: Methods, applications, and directions. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 3768–3789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Z.; Xing, M.; Zhang, J.; Wu, B.H. Few-shot network intrusion detection based on model-agnostic meta-learning with l2f method. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE Wireless Communications and Networking Conference (WCNC), Glasgow, UK, 26–29 March 2023; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Shone, N.; Ngoc, T.N.; Phai, V.D.; Shi, Q. A deep learning approach to network intrusion detection. IEEE Trans. Emerg. Top. Comput. Intell. 2018, 2, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulanuwat, L.; Chantrapornchai, C.; Maleewong, M.; Wongchaisuwat, P.; Wimala, S.; Sarinnapakorn, K.; Boonya-Aroonnet, S. Anomaly detection using a sliding window technique and data imputation with machine learning for hydrological time series. Water 2021, 13, 1862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostas, K.; Just, M.; Lones, M.A. Iotgem: Generalizable models for behaviour-based iot attack detection. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2401.01343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, H.; Ahn, D.H.; Lee, G.M.; Yoo, J.D.; Park, K.H.; Kim, H.K. IoT Network Intrusion Dataset. IEEE Dataport 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, T.; Gao, W. Industrial control system traffic data sets for intrusion detection research. In Critical Infrastructure Protection VIII, Proceedings of the 8th IFIP WG 11.10 International Conference, ICCIP 2014, Arlington, VA, USA, 17–19 March 2014, Revised Selected Papers; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2014; pp. 65–78. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, G.; Xiao, M. Low-Latency Communications with Millimeter Wave. In Encyclopedia of Wireless Networks; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 733–736. [Google Scholar]

- Meidan, Y.; Bohadana, M.; Mathov, Y.; Mirsky, Y.; Shabtai, A.; Breitenbacher, D.; Elovici, Y. N-baiot—network-based detection of iot botnet attacks using deep autoencoders. IEEE Pervasive Comput. 2018, 17, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beshah, Y.K.; Abebe, S.L.; Melaku, H.M. Drift adaptive online DDoS attack detection framework for IoT system. Electronics 2024, 13, 1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadreazami, H.; Mohammadi, A.; Asif, A.; Plataniotis, K.N. Distributed-graph-based statistical approach for intrusion detection in cyber-physical systems. IEEE Trans. Signal Inf. Process. Over Netw. 2017, 4, 137–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gal, Y.; Ghahramani, Z. Dropout as a bayesian approximation: Representing model uncertainty in deep learning. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, PMLR, ICML 2016, New York, NY, USA, 19–24 June 2016; pp. 1050–1059. [Google Scholar]

- Deb, K. Multi-Objective Optimization Using Evolutionary Algorithms; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Zitzler, E.; Thiele, L.; Laumanns, M.; Fonseca, C.M.; da Fonseca, V.G. A tutorial on evolutionary multiobjective optimization. Metaheuristics Multiobject. Optim. 2004, 5255, 3–37. [Google Scholar]

- Sethuraman, R.; Kar, S.; Selvamuthu, D. Analysis of traffic offload using multi-attribute decision making technique in heterogeneous shared networks. IET Netw. 2019, 8, 256–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, B.; Dastjerdi, A.V.; Calheiros, R.N.; Srirama, S.N.; Buyya, R. A context sensitive offloading scheme for mobile cloud computing service. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE 8th international conference on cloud computing, New York, NY, USA, 27 June–2 July 2015; pp. 869–876. [Google Scholar]

- Mahadevappa, P.; Murugesan, R.K.; Al-Amri, R.; Thabit, R.; Al-Ghushami, A.H.; Alkawsi, G. A secure edge computing model using machine learning and IDS to detect and isolate intruders. MethodsX 2024, 12, 102597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jamshidi, S.; Nafi, K.W.; Nikanjam, A.; Khomh, F. Evaluating machine learning-driven intrusion detection systems in IoT: Performance and energy consumption. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2025, 204, 111103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vahabi, M.; Fotouhi, H.; Fotouhi, H. Federated learning at the edge in Industrial Internet of Things: A review. Sustain. Comput. Inform. Syst. 2025, 46, 101087. [Google Scholar]

- Korodi, A.; Nițulescu, I.V.; Fülöp, A.A.; Vesa, V.C.; Demian, P.; Braneci, R.A.; Popescu, D. Integration of Legacy Industrial Equipment in a Building-Management System Industry 5.0 Scenario. Electronics 2024, 13, 3229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comert, M.; Ahmed, A.; Ahmed, H. Identifying security challenges in the transition from traditional to smart manufacturing through IIoT retrofitting. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 14th International Conference on the Internet of Things, Oulu, Finland, 19–22 November 2024; pp. 285–289. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).