Abstract

The rapid digitalization of work and daily life has introduced a wide range of online threats, from common hazards such as malware and phishing to emerging challenges posed by artificial intelligence (AI). While technical aspects of cybersecurity have received extensive attention, less is known about how individuals perceive digital risks and how these perceptions shape protective behaviors. Building on the psychometric paradigm, this study investigated the perception of seven digital threats among a sample of 300 Italian workers employed in IT and non-IT sectors. Participants rated each hazard on dread and unknown risk dimensions and reported their cybersecurity expertise. Optimism bias and proactive awareness were also detected. Cluster analyses revealed four profiles based on different levels of dread and unknown risk ratings. The four profiles also differed in reported levels of expertise, optimism bias, and proactive awareness. Notably, AI was perceived as the least familiar and most uncertain hazard across groups, underscoring its salience in shaping digital risk perceptions. These findings highlight the heterogeneity of digital risk perception and suggest that tailored communication and training strategies, rather than one-size-fits-all approaches, are essential to fostering safer online practices.

1. Introduction

The pervasive digitalization of daily life has undeniably brought unprecedented convenience and connectivity [1]. However, this advancement has simultaneously exposed individuals to a broad and evolving spectrum of online threats. These include common hazards such as malware infections, sophisticated phishing attempts, identity theft, the misuse of online credentials, and the inappropriate sharing of personal information on social media platforms [2]. In recent years, the proliferation of interconnected devices and systems, driven by the convergence of machine learning, artificial intelligence (AI), and the Internet of Things, has further transformed the cyber risk landscape [3]. As data is increasingly created, exchanged, and processed autonomously by smart devices and algorithms, new non-traditional vulnerabilities have emerged that blur the boundaries between human and technological agency [3]. These developments have amplified the potential for threats such as malware propagation and credential theft within complex, interlinked ecosystems, highlighting the need for a deeper understanding of how individuals perceive and respond to such risks.

While cybersecurity research has traditionally emphasized the technical identification of vulnerabilities and the development of robust defense mechanisms [4], the human factor remains a critically important, and often underestimated, determinant of overall protection [5,6]. Individuals’ perceptions of digital risks significantly influence whether they engage in secure behaviors, such as regularly updating software, exercising caution when encountering suspicious links, or prudently limiting the disclosure of personal data online [7,8,9]. Despite its profound relevance in shaping user behavior and contributing to effective cybersecurity, digital risk perception remains less systematically conceptualized and empirically investigated [10] compared to risk perception in well-established domains like environmental hazards or public health [11].

1.1. The Psychometric Paradigm and Digital Risks

The psychometric paradigm, pioneered by Slovic in 1987 [11] and further elaborated by Slovic et al. in 2004 [12], provides a robust and structured framework for analyzing how diverse hazards are perceived by the public. According to this model, risk perception can be effectively described along two main, largely independent, dimensions: dread risk and unknown risk. Dread risk captures perceptions related to the severity of consequences, the degree of uncontrollability, and the potential for catastrophic outcomes (e.g., widespread harm, long-term impact). Hazards scoring high on dread are often associated with feelings of terror, lack of control, and a sense of imminent catastrophe. Conversely, unknown risk reflects characteristics such as how novel, observable, and well-understood a particular hazard is. Hazards scoring high on unknown risk are typically new, unobservable, have delayed effects, and are not well understood by science or individuals.

This psychometric approach has been widely and successfully applied to a broad array of environmental hazards (e.g., nuclear energy, chemical waste disposal, climate change) and public health threats (e.g., global pandemics, vaccination side effects, foodborne illnesses) [13,14,15,16,17], offering invaluable insights into the complex cognitive and affective components that shape public assessments and reactions to various risks [18,19]. Understanding these dimensions is crucial because they predict not only public acceptance of technologies but also the willingness to support regulatory measures and engage in protective behaviors [20].

Digital threats, however, present a unique set of challenges that distinguish them from more traditional physical or environmental hazards. They are often intangible and invisible, making them difficult to detect or conceptualize without specialized knowledge, their consequences may be delayed, as is often the case with data breaches that are only discovered months after the initial compromise, and their perceived severity frequently depends on a complex interplay of both technical exposure and individual behavioral choices [21,22]. Moreover, the rapid evolution of technology means that new digital threats emerge constantly, often outpacing public understanding and established protective measures. The psychometric paradigm may therefore be a particularly insightful tool for mapping public perceptions of these distinct digital hazards, including both established cyber threats and increasingly salient emerging technological risks such as those posed by AI [23]. By applying this framework, researchers can better understand the underlying factors driving public concern and inform more effective risk communication strategies tailored to the unique characteristics of digital environments.

1.2. Optimism Bias in Digital Risk Perception

Beyond the inherent characteristics of hazards, risk perception is also profoundly shaped by a range of cognitive biases. One of the most robust and consistently observed findings in this area is optimism bias (also known as unrealistic optimism or comparative optimism), which is the pervasive human tendency to believe that negative events are less likely to happen to oneself than to others, or conversely, that positive events are more likely to happen to oneself than to others [24,25]. This bias represents a pervasive psychological phenomenon, and it has been hypothesized that it often serves to protect self-esteem or reduce anxiety [26,27].

In the specific context of online threats, optimism bias can lead individuals to significantly underestimate their personal vulnerability, particularly for risks that are perceived as familiar, common, or controllable [28,29,30]. For example, users might believe they are less likely to fall victim to phishing simply because they have encountered many phishing emails, leading to a false sense of security. This skewed perception can result in a reluctance to adopt necessary protective measures, such as carefully checking where links lead before clicking, regularly backing up data, or updating security software, on the belief that “it won’t happen to me” [31]. Conversely, less familiar or more “dreaded” threats, such as those associated with the opaque and rapidly evolving nature of AI-driven risks, may elicit greater concern and a heightened sense of vulnerability, even among individuals with relatively high technical competence [32]. Understanding the relationship between optimism bias and the dread and unknown dimensions of risk is crucial for designing effective interventions [33] that align with how individuals actually perceive and respond to different digital threats.

1.3. Present Study

This study aims to apply the psychometric paradigm to seven distinct digital threats: social media information sharing, malware infections, general internet browsing risks, phishing attempts, online identity theft, online credential theft, and risks associated with generative AI. The primary objective is to map these diverse threats along the two fundamental dimensions of dread and unknown risk, thereby identifying perceptual patterns that can provide insights for developing more targeted and effective risk communication campaigns and preventive strategies.

Furthermore, the study considers the crucial role of self-rated cybersecurity expertise and optimism bias in shaping individuals’ perceptions of these digital hazards. This allows for a critical examination of whether individuals’ perceived competence in cybersecurity and their inherent cognitive biases are related to how they evaluate and respond to different types of digital hazards. Ultimately, this research aims to offer a basis for designing and implementing evidence-based interventions that promote safer, more informed online behavior across the general population.

In contrast to previous studies that have mainly investigated isolated cybersecurity risks or general attitudes toward online safety [33,34], this research introduces a broader and integrative perspective. It applies the psychometric paradigm to a comprehensive and contemporary set of digital hazards, including both traditional and emerging threats, within a working population. This cross-sectional comparison between IT and non-IT employees, coupled with the inclusion of generative AI as a novel hazard, provides novel insights into how modern digital risks are cognitively and emotionally represented, thereby extending prior work on technological risk perception to the rapidly evolving domain of cybersecurity.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedure

Data were collected using an online questionnaire administered through Google Forms and distributed via the participant recruitment platform Prolific. The study adopted a cross-sectional design, was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Trieste, Italy (Minutes No. 4, dated 29 April 2024), and was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Participants were recruited on a voluntary basis and provided informed consent before accessing the survey. The inclusion criteria included being 18 years or older, currently employed, using digital tools at work, and having Italian as the primary language were. A sampling quota was applied to ensure that approximately 50% of the sample worked in the IT sector and 50% in other sectors. Data collection took place between 1 April 2025, and 30 April 2025.

A total of 300 adult workers completed the questionnaire. Of these, 156 were employed in the IT sector and 144 in non-IT sectors, allowing for the exploration of differences based on professional background. An a priori power analysis conducted using GPower 3.1 [35], based on a one-way fixed effects ANOVA design with four groups, indicated that a minimum sample of 274 participants was required to detect a medium effect size (f = 0.25) with α = 0.05 and power = 0.80. The obtained sample thus exceeded the estimated requirement and provided sufficient power for the planned analyses.

2.2. Measures

In the first section of the questionnaire, participants were asked to evaluate their perception of seven digital hazards: social media information sharing, malware, internet browsing, phishing, online identity theft, online credential theft, and generative AI. These evaluations were based on the psychometric paradigm of risk perception. Specifically, for each hazard, participants first rated the perceived risk level on a 7-point Likert scale (1 = not risky at all, 7 = very risky). Then, as commonly done in studies adopting the psychometric paradigm of risk perception [36], they were asked to rate nine items measuring the dread risk and unknown risk dimensions, using 7-point semantic differential Likert scales. The dread risk items included: (1) Controllable vs. uncontrollable harmful effects; (2) Few vs. many exposed to the risk; (3) Common vs. terrifying risk; (4) Non-fatal vs. fatal consequences; and (5) Voluntarily assumed vs. involuntarily assumed risk. The unknown risk items were: (1) Immediate vs. deferred effects; (2) New vs. familiar risk; (3) Known risk vs. unknown risk to workers; and (4) Known risk vs. unknown risk to experts. Before evaluating each hazard, participants were provided with a brief definition and illustrative examples to ensure a consistent understanding of the stimuli. For instance: Generative AI was defined as “a branch of artificial intelligence capable of generating, through the processing of pre-acquired data, original content such as images, texts, or videos, similar to those created by humans (e.g., ChatGPT, Gemini, Copilot, DALL·E).” The complete set of hazard descriptions is reported in Appendix A.

Optimism bias was assessed with the following item: “Compared to other people of your age and with your level of IT expertise, how much at risk do you consider yourself to be of experiencing cybersecurity threats?” Responses were provided on a 5-point Likert scale (−2 = much less at risk, −1 = less at risk, 0 = equally at risk, 1 = more at risk, 2 = much more at risk).

Subsequently, participants completed the Proactive Awareness subscale of the Security Behavior Intentions Scale [37], consisting of five items that assess engagement in digital security practices (e.g., “When browsing websites, I mouseover links to see where they go, before clicking them.”). Responses were given on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree). McDonald’s ω for the present study was 0.61, a value that closely mirrored the reliability reported for the original scale (0.64; [37]). Given this comparability, the scale was retained as an adequate measure of proactive awareness in the cybersecurity domain.

Finally, participants rated their perceived cybersecurity expertise on a 7-point Likert scale (1 = not at all, 7 = very high) and provided demographic information, including age, gender, and current job seniority.

2.3. Data Analysis

Following the psychometric paradigm, items related to dread and unknown risk were first averaged for each of the seven digital hazards, resulting in 14 perception variables (7 dread scores and 7 unknown risk scores). Before computing these aggregated scores, the two-factor structure underlying the nine risk-perception items was preliminarily examined through confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), which showed an acceptable fit to the theoretical model. Detailed CFA results are available from the authors upon request. These variables were subsequently standardized (z-scores) and subjected to an exploratory hierarchical cluster analysis using Ward’s method and squared Euclidean distance to identify patterns of similarity in participants’ perception profiles. Inspection of the dendrogram and agglomeration coefficients guided the determination of the optimal number of clusters.

To validate the identified structure, a K-means cluster analysis was subsequently performed, assigning each participant to the nearest centroid. The resulting groups were interpreted based on their mean scores on dread and unknown risk across hazards. To assess the internal consistency and robustness of the identified cluster structure, additional validation procedures were performed, including the calculation of silhouette coefficients and a cross-validation approach (70/30 training–test split).

The clusters were then compared using chi-square tests and analysis of variance (ANOVA) on demographic and psychological variables, including professional domain (IT vs. non-IT), self-rated cybersecurity expertise, optimism bias, and proactive awareness. Effect sizes (η2 or Cohen’s d) and 95% confidence intervals were computed for all relevant tests. Post hoc comparisons were adjusted for multiple testing using the Tukey HSD test.

Finally, to further explore the predictors of proactive awareness, a multiple linear regression analysis was conducted. The model included cluster membership (dummy coded), self-rated cybersecurity expertise, optimism bias, age, gender, and professional sector (IT vs. non-IT), as well as the interaction between cluster membership and professional sector.

To assess optimism bias, each participant’s bias score was compared against zero, which represented the perception of being ‘equally at risk’ as others matched for age and IT competence.

All analyses were conducted using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS), v23.0 (IBM SPSS Statistics, Armonk, NY, USA) and R v4.5.1 (R Core Team).

3. Results

Participants’ demographic information and self-rated cybersecurity expertise are reported in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Study Sample.

As expected, participants employed in the IT sector reported significantly higher self-reported cybersecurity expertise than those in non-IT sectors (t(298) = 8.74, p < 0.001, d = 1.01, 95% CI [0.75, 1.26]). Regarding optimism bias, both IT and non-IT employees reported scores that significantly deviated from the scale’s midpoint (0 = “equally at risk”). These results indicate a pervasive belief among both groups of being less at risk than other people of the same age and IT expertise (IT employees, t(155) = −18.30, p < 0.001, d = −1.46, 95% CI [−1.69, −1.24]; non-IT employees, t(143) = −8.94, p < 0.001, d = −0.75, 95% CI [−0.93, −0.56]). Furthermore, IT employees exhibited a significantly stronger optimism bias compared to non-IT employees (t(298) = 6.31, p < 0.001, d = 0.73, 95% CI [0.49, 0.97]). IT employees also reported significantly higher engagement in proactive security behaviors compared to non-IT employees (t(297) = 4.94, p < 0.001, d = 0.57, 95% CI [0.34, 0.81]).

The results for the psychometric paradigm items (overall riskiness, dread risk, and unknown risk) for each of the seven hazards are reported in Table 2. Higher scores on dread indicate stronger perceptions of severity and uncontrollability, while higher scores on unknown risk reflect lower familiarity and greater uncertainty about the hazard.

Table 2.

Psychometric paradigm dimensions for each hazard.

Online credential theft, online identity theft, and malware were perceived as the riskiest hazards among those assessed, with mean scores approaching a ceiling effect. It is worth noting that these elevated risk ratings were not accompanied by equally high levels of dread, which remained moderate across hazards. Conversely, internet browsing and generative AI were rated as the least risky hazards.

Table 3 shows the correlations between overall perceived riskiness and the Dread and Unknown dimensions for each digital hazard. Perceived riskiness is positively correlated with Dread across all risks, whereas correlations with Unknown are generally weak and occasionally non-significant.

Table 3.

Pearson correlations between overall risk perception and dread and unknown risk dimensions for each digital hazard.

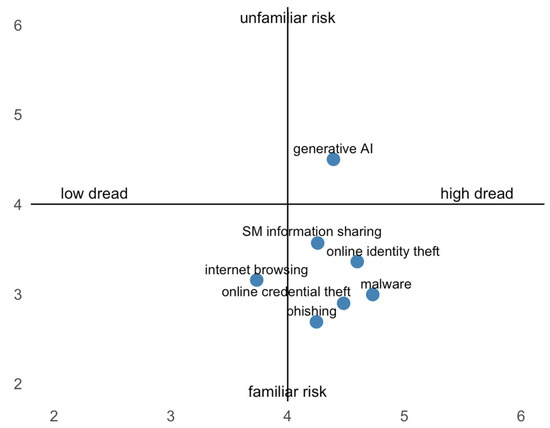

To visualize the positioning of these hazards within the psychometric paradigm, Figure 1 displays the risk map, plotting the seven hazards according to their average scores on the dread risk dimension (x-axis) and the unknown risk dimension (y-axis).

Figure 1.

Risk map of seven digital hazards: social media information sharing, malware, internet browsing, phishing, online identity theft, online credential theft, and generative AI. The x-axis represents the dread risk dimension, and the y-axis represents the unknown risk dimension.

The risk map reveals that most hazards clustered in the high-dread/low-unknown risk quadrant, particularly malware, online identity and credential theft, phishing, and social media information sharing. In contrast, internet browsing was perceived as moderately dreadful with relatively low unknown risk. Notably, generative AI clearly stood apart from the other hazards, being positioned in the high-dread and high-unknown quadrant, reflecting its novelty and the higher uncertainty perceived by participants.

To identify overarching patterns in how participants perceived the seven digital hazards, a hierarchical cluster analysis was performed on the dread and unknown risk ratings, using Ward’s method and squared Euclidean distance as the similarity measure. Examination of the dendrogram (available in Appendix B) and inspection of the agglomeration coefficients revealed a pronounced increase in within-cluster heterogeneity when moving from a four- to a three-cluster solution, supporting the selection of a four-cluster structure. This pattern suggested that the four-cluster solution provided the most parsimonious and theoretically meaningful representation of participants’ risk perception profiles. Consequently, the four-cluster structure was retained and further validated through a K-means cluster analysis, which confirmed the stability of the solution and allowed the assignment of each participant to the nearest cluster centroid. To further evaluate the robustness of this solution, we computed the average silhouette width and conducted a simple 70/30 cross-validation procedure. The mean silhouette width across clusters was 0.103, with cluster-specific averages of 0.12 (Cluster 1), 0.10 (Cluster 2), 0.07 (Cluster 3), and 0.13 (Cluster 4), indicating moderate internal cohesion and adequate separation among groups. In the cross-validation, test cases were assigned to the nearest centroids derived from the training set, resulting in 9, 30, 26, and 25 cases per cluster, respectively. These results support the overall stability and interpretability of the four-cluster solution.

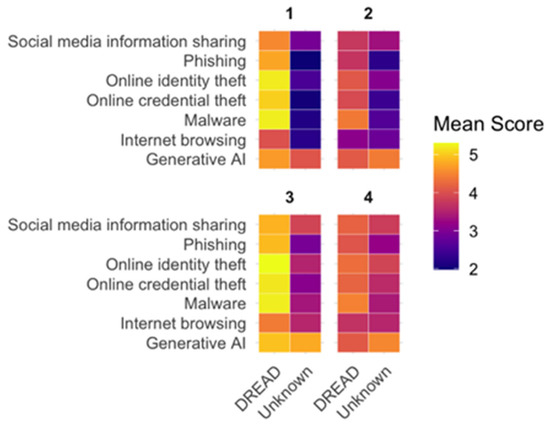

Figure 2 provides a visual representation of the cluster profiles. The heat map illustrates the mean scores of each cluster across the seven digital hazards along the dread and unknown risk dimensions. Warmer colors indicate higher perceived intensity on each dimension, thereby visually distinguishing the four clusters’ patterns of risk perception.

Figure 2.

Heat map showing the mean ratings of the four clusters across the seven digital hazards on the two psychometric dimensions (Dread and Unknown risk). Each colored cell represents the average score for a specific hazard and dimension, with warmer colors indicating higher perceived intensity. The figure highlights the distinctive patterns of risk perception characterizing each cluster.

To interpret the content of the four clusters, we examined their mean scores on dread and unknown risk dimensions for each of the seven digital hazards. Table 4 reports these average values per cluster, along with the number and percentage of participants included in each group.

Table 4.

Mean dread risk and unknown risk ratings in each cluster.

The interpretation of the clusters was conducted a posteriori, based on the patterns emerging across the two risk dimensions and their consistency with theoretical expectations derived from the psychometric paradigm. The four clusters revealed distinct patterns of digital risk perception. Cluster 1 was characterized by relatively high dread across most hazards but comparatively low scores on unknown risk. Participants in this cluster tended to view digital threats as serious yet familiar and understandable, suggesting a profile of informed concern. In contrast, Cluster 2 showed the lowest levels of dread and relatively low unknown risk, indicating that participants perceived digital threats as manageable and not particularly alarming. Cluster 3 displayed the highest dread scores together with the highest levels of unknown risk, perceiving the hazards as both severe and poorly understood. Finally, Cluster 4 was distinguished by medium-to-high levels of dread and unknown risk. Compared to Cluster 3, they appeared less alarmed but still expressed substantial uncertainty, reflecting a cautious but not extreme stance toward digital threats.

A chi-square test revealed significant differences in the distribution of IT and non-IT employees across the four clusters (Table 5, χ2(3) = 16.53, p = 0.001). Specifically, clusters 1 and 2 comprised a larger proportion of IT employees, whereas cluster 3 and 4 were more balanced or showed a greater representation of non-IT workers.

Table 5.

Frequencies and percentages of IT and non-IT employees in each cluster.

A series of one-way ANOVAs with Tukey post hoc tests were conducted to compare clusters on self-rated cybersecurity expertise, optimism bias, and proactive awareness. All analyses were also replicated using the Welch correction and Games–Howell post hoc tests to account for unequal variances, yielding fully consistent results (Table 6). Results indicated a significant effect of cluster membership on cybersecurity expertise (F(3,296) = 9.91, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.09). Post hoc comparisons showed that members of Cluster 1 reported significantly higher expertise than those in Cluster 3 (p < 0.05, d = 0.57, 95% CI [0.17, 0.96]) and Cluster 4 (p < 0.001, d = 0.89, 95% CI [0.50, 1.28]), while Cluster 2 participants scored significantly higher than Cluster 4 participants (p < 0.001, d = 0.65, 95% CI [0.36, 0.94]). A similar pattern emerged for optimism bias (F(3,296) = 4.48, p = 0.004, η2 = 0.04), with participants in Clusters 1 and 2 reporting a stronger optimism bias than those in Cluster 4 (p < 0.05, d = 0.56, 95% CI [0.17, 0.94], and p < 0.05, d = 0.42, 95% CI [0.13, 0.71]). Finally, proactive awareness differed significantly across clusters (F(3,295) = 9.73, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.04). Participants in Cluster 4 reported significantly lower engagement in proactive security behaviors than participants in all other clusters (vs. Cluster 1, p < 0.001, d = 0.84, 95% CI [0.45, 1.23], vs. Cluster 2, p < 0.001, d = 0.69, 95% CI [0.39, 0.98], vs. Cluster 3, p < 0.05, d = 0.43, 95% CI [0.12, 0.74]).

Table 6.

Mean cybersecurity expertise, Optimism bias and proactive awareness in each cluster.

To further examine how individual differences and cluster membership jointly influenced proactive awareness, a multiple linear regression was conducted including cluster membership (dummy-coded), self-rated cybersecurity expertise, optimism bias, and professional sector (IT vs. non-IT) as predictors, along with their interaction terms. The model accounted for approximately 24% of the variance in proactive awareness (R2 = 0.24). Self-rated cybersecurity expertise emerged as a significant positive predictor (β = 0.15, p < 0.001), whereas optimism bias negatively predicted proactive awareness (β = −0.15, p = 0.004). Among the cluster variables, only Cluster 4 was a significant negative predictor (β = −0.421, p = 0.005), indicating lower engagement in security behaviors compared to participants in Cluster 1, which served as the reference group. Cluster 2, Cluster 3, gender, and all interaction terms were not significant, and age showed a marginal positive association (β = 0.006, p = 0.072).

Based on their distinct profiles across perceived risk dimensions (dread and unknown risk), self-rated cybersecurity expertise, optimism bias, and proactive awareness, the four clusters were subsequently labeled to reflect their predominant characteristics. Cluster 1, characterized by relatively high dread and low unknown risk alongside higher expertise and proactive behaviors, was named Vigilant Realists. Cluster 2, showing the lowest dread and unknown risk, coupled with strong optimism bias and higher proactive engagement, was termed Under-concerned Optimists. Cluster 3, which exhibited the highest dread and unknown risk, combined with lower expertise and a weaker optimism bias, was labeled Anxious & Uncertain. Finally, Cluster 4, marked by medium-to-high dread and unknown risk but notably the lowest proactive awareness, was identified as Concerned Bystanders. These labels provide a conceptual framework for understanding the diverse ways individuals perceive and respond to digital threats.

4. Discussion

4.1. General Findings and Discussion

The present study contributes to the growing body of research on digital risk perception [21,38,39] by applying the psychometric paradigm to a range of contemporary digital hazards. This includes traditional threats like malware, phishing, and credential theft, as well as emerging issues such as generative AI. By combining measures of dread and unknown risk, alongside assessments of self-rated cybersecurity expertise, optimism bias, and proactive security behaviors, we identified four distinct perception profiles among employees who use digital tools at work. This approach effectively captures the heterogeneity in how individuals evaluate digital threats.

Overall, the findings highlight that digital risk perception does not follow a single, uniform pattern, rather it segments into meaningful typologies with specific implications for intervention.

The Vigilant Realists (Cluster 1) combined relatively high dread with low unknown risk. This profile suggests individuals who perceive digital threats as serious and potentially severe, yet feel they possess a strong understanding and familiarity with these risks. Their higher self-rated cybersecurity expertise and strong proactive awareness reinforce a profile of informed concern and practical engagement. At the same time, members of this cluster displayed one of the strongest levels of optimism bias, indicating that their confidence in knowledge and practices may lead them to underestimate their personal vulnerability. For practice, communication strategies targeting this group should aim to reinforce existing knowledge and high security standards, while also counterbalancing overconfidence by emphasizing that even well-informed users remain exposed to evolving and unpredictable threats.

In contrast, the Under-concerned Optimists (Cluster 2) reported the lowest levels of dread and unknown risk, coupled with the strong optimism bias and high proactive awareness. This group appears to downplay potential dangers, likely due to a combination of perceived competence and a tendency to believe negative events are less likely to happen to them. Interventions for this group might need to subtly challenge overconfidence by presenting realistic, but not fear-mongering, scenarios that demonstrate the pervasive nature of threats, even for experienced users, without undermining their existing proactive behaviors.

The Anxious & Uncertain (Cluster 3) displayed the highest dread scores together with the highest levels of unknown risk. This profile points to individuals who perceive hazards as both highly threatening and poorly understood. Their lower self-rated expertise and weaker optimism bias, combined with comparatively lower proactive awareness, suggest a state of overwhelm or helplessness. For this group, practical interventions should prioritize foundational education and demystification of digital threats, offering clear, actionable steps to reduce perceived uncertainty and build a sense of control, thereby transforming anxiety into productive action.

Finally, the Concerned Bystanders (Cluster 4) were marked by medium-to-high dread and unknown risk, but notably reported the lowest engagement in proactive security behaviors among all clusters. This suggests individuals who are moderately concerned and uncertain about digital threats but struggle to translate this concern into protective action. This group represents a critical target for interventions focusing on behavioral activation. Strategies should simplify security practices, provide clear step-by-step guides, and potentially leverage social norms or reminders to bridge the gap between their moderate concern and a lack of active engagement.

Consistent with this interpretation, regression analyses confirmed that self-rated cybersecurity expertise positively predicted proactive security behaviors, whereas optimism bias exerted a small but significant negative effect. Moreover, membership in the Concerned Bystanders cluster also predicted reduced engagement in protective behaviors, even after accounting for individual differences in expertise and optimism.

These differentiated patterns align with previous work showing that perceptions of controllability, familiarity, and dread play a key role in shaping responses to technological risks [11,15], but they extend such insights to the domain of cybersecurity and AI.

Importantly, the emergence of artificial intelligence as the least familiar hazard across clusters underscores the salience of novel digital technologies in shaping public concern. Unlike more traditional risks, AI is perceived as relatively unknown, evoking uncertainty regardless of an individual’s general cybersecurity expertise. This suggests that communication and policy initiatives addressing AI-related risks should consider not only technical vulnerabilities but also the broader psychological and social dimensions of perceived uncertainty. Effective strategies will need to build familiarity, explain complex concepts in accessible ways, and provide clear guidelines for understanding and managing AI-related risks.

Another notable finding is the pervasive role of optimism bias, which was evident to varying degrees across all clusters. While participants generally perceived themselves as less at risk than others of similar age and IT expertise, the intensity of this bias varied significantly. Vigilant Realists and Under-concerned Optimists exhibited stronger optimism bias compared to Anxious & Uncertain and Concerned Bystanders. This points to a paradox: those with higher perceived expertise and proactive behaviors may also underestimate their personal vulnerability. A possible explanation is that consistent engagement in security practices and a sense of technical competence can foster an illusion of control, leading individuals to believe that their behaviors effectively shield them from risk [40]. Over time, this confidence may evolve into a subtle form of complacency, where familiarity with threats reduces perceived risk rather than reinforcing caution. Similar patterns have been observed in other safety-critical domains, where experience and skill can paradoxically lower perceived risk [24,40,41]. Understanding this relationship is crucial for designing interventions that mitigate overconfidence without diminishing protective behaviors.

4.2. Strengths and Limitations

A key strength of this study is the use of a relatively large and balanced sample of IT and non-IT workers, which ensured both heterogeneity and comparability across professional domains. Moreover, the application of both hierarchical and K-means clustering provided robust evidence for the four-cluster solution, while the integration of self-reported expertise, optimism bias, and proactive behaviors allowed for a comprehensive examination of how perception patterns translate into action. Another strength lies in the inclusion of generative AI, which extends the psychometric paradigm to an emergent technological domain.

Nonetheless, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, the reliance on self-report measures for expertise, optimism bias, and proactive awareness may have introduced social desirability or recall biases, limiting the strength of the behavioral inferences that can be drawn. Nevertheless, previous research has shown that self-reported cybersecurity behaviors can validly reflect individual practices and tendencies, even when unsafe actions are disclosed [42,43]. Second, the cross-sectional design prevents causal conclusions about the relationships between risk perception, optimism bias, and security practices. Third, while the sample was balanced across IT and non-IT workers, it was restricted to Italian-speaking participants, limiting the generalizability of the findings to other cultural contexts. Finally, the reliability of the proactive awareness subscale was modest. Although this value is consistent with prior research [37], it likely reflects the brevity and behavioral nature of the scale rather than a structural weakness. Nonetheless, this limitation suggests that behavioral findings should be interpreted with appropriate caution. Future studies should refine measurement tools for digital security behaviors by integrating more objective indicators or behavioral measures.

Taken together, these findings demonstrate that digital risk perception is multifaceted and structured in identifiable profiles, with important implications for risk communication, cybersecurity training, and policy interventions. By tailoring approaches to these distinct perceptual groups, interventions can be designed to be more targeted and effective, ultimately fostering safer and more informed online behaviors across the general population.

5. Conclusions

This study examined digital risk perception through the lens of the psychometric paradigm, applying it to a contemporary set of digital hazards, including generative AI. The results indicate that perceptions of digital risk are not monolithic, but rather structured into four distinct profiles: Vigilant Realists, Under-concerned Optimists, Anxious & Uncertain, and Concerned Bystanders. Each cluster represents a unique combination of perceived dread, unknown risk, self-rated cybersecurity expertise, optimism bias, and engagement in proactive security behaviors. The identification of these distinct profiles underscores the necessity of moving beyond generic, “one-size-fits-all” campaigns toward tailored awareness initiatives, training programs, and policy interventions that resonate with the specific psychological and behavioral characteristics of each group.

For instance, Vigilant Realists may benefit from advanced threat intelligence, while Under-concerned Optimists might require subtle challenges to their overconfidence. Anxious & Uncertain individuals need foundational education to transform their high concern and perceived helplessness into actionable knowledge, whereas Concerned Bystanders would benefit from simplified, actionable steps to bridge the gap between moderate concern and low engagement in protective behaviors. Furthermore, the perception of generative AI as high in unknown risk, irrespective of individual expertise, signals a particular need for clear, accessible communication to build familiarity and mitigate uncertainty around emerging technologies [44].

Building upon these insights, future research should pursue several promising avenues. First, longitudinal studies are essential to explore the causal relationships between risk perception, optimism bias, expertise, and proactive behaviors. This would clarify whether changes in perceived risk lead to altered behaviors, or vice versa. Second, the generalizability of our findings could be enhanced by replicating this study in diverse cultural and linguistic contexts, as digital risk perception may vary significantly across different societal norms and technological adoption rates. Third, future work should focus on developing and testing targeted interventions derived from our cluster profiles. This involves designing specific communication messages or training modules for each group and evaluating their effectiveness in promoting safer online behaviors. Finally, given the modest reliability of the proactive awareness subscale, there is a need for further development and validation of robust measurement tools for digital security behaviors, particularly those that can capture both intentional and habitual actions in a less biased manner than self-report.

In conclusion, this study provides a structured perspective on the complex landscape of digital risk perception among employees. By recognizing and responding to the diverse psychological profiles of users, more effective, human-centric strategies can be developed to foster a safer digital environment.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.C., F.M. (Francesco Marcatto), F.M. (Francesca Mistichelli) and D.F.; methodology, F.M. (Francesco Marcatto); formal analysis, D.C. and F.M. (Francesco Marcatto); investigation, D.C., F.M. (Francesco Marcatto) and F.M. (Francesca Mistichelli); resources, F.M. (Francesco Marcatto) and F.M. (Francesca Mistichelli); data curation, D.C. and F.M. (Francesco Marcatto); writing—original draft preparation, D.C. and F.M. (Francesco Marcatto); writing—review and editing, D.C., F.M. (Francesco Marcatto), F.M. (Francesca Mistichelli) and D.F.; supervision, D.F.; project administration, F.M. (Francesco Marcatto); funding acquisition, F.M. (Francesco Marcatto) All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Laus Informatica srl.: 23/05/24.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Trieste, Italy (Minutes No. 4, dated 29 April 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript, the author(s) used Gemini 2.5 Pro to improve the language, style, and readability of the text. The authors have reviewed and edited all AI-generated suggestions and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

F.MI. is an employee of Laus Informatica srl, which funded this research. The funder had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| IT | Information Technology |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

Appendix A

Participants were provided with a short description of each digital hazard before completing the risk perception ratings. The wording was intended to reduce ambiguity and ensure a shared understanding of the stimuli.

Table A1.

Risk stimuli presented to participants.

Table A1.

Risk stimuli presented to participants.

| Hazard | Descriptions Presented to Participants |

|---|---|

| Social Media Information Sharing | Activity that consists of making personal information available to other people through the use of social media (e.g., Facebook, Instagram, LinkedIn, Twitter, TikTok, etc.). |

| Malware | Computer program, digital document, application, or email capable of causing damage to a computer system. (e.g., viruses, spyware, rogueware, ransomware, Trojans, etc.) |

| Internet browsing | Exploring web pages through a browser, using the search bar, clicking on hyperlinks, or using search engines. |

| Phishing | Phishing involves cybercriminals sending particularly credible emails that trick people into clicking on malicious links, allowing them to access computer systems and subsequently demand a ransom. |

| Identity theft | An activity perpetrated by cybercriminals to illegally obtain an individual’s personal data (first name, last name, date of birth, social security number, address) in order to commit fraud or illegal acts in their name. |

| Credential theft | Activity perpetrated by cybercriminals to illegally obtain sensitive data belonging to an individual (passwords, PINs, and access keys to bank accounts or credit card cloning) in order to commit fraud, theft, or other illegal acts against them. |

| Artificial Intelligence (AI) | A branch of artificial intelligence that is capable of generating, through the processing of pre-acquired data, original content such as images, texts, and videos, similar to those created by humans (e.g., CHAT GPT, GEMINI, COPILOT, DALL-E, etc.). |

Appendix B

Figure A1.

Cluster analysis dendrogram.

References

- Farkaš, I. Transforming Cognition and Human Society in the Digital Age. Biol. Theory 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslan, Ö.; Aktuğ, S.S.; Ozkan-Okay, M.; Yilmaz, A.A.; Akin, E. A Comprehensive Review of Cyber Security Vulnerabilities, Threats, Attacks, and Solutions. Electronics 2023, 12, 1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chahal, A.; Addula, S.R.; Jain, A.; Gulia, P.; Gill, N.S.; Dhandayuthapani, V.B. Systematic Analysis Based on Conflux of Machine Learning and Internet of Things Using Bibliometric Analysis. J. Intell. Syst. Internet Things 2024, 13, 196–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humayun, M.; Niazi, M.; Jhanjhi, N.; Alshayeb, M.; Mahmood, S. Cyber Security Threats and Vulnerabilities: A Systematic Mapping Study. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 2020, 45, 3171–3189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proctor, R.W.; Chen, J. The Role of Human Factors/Ergonomics in the Science of Security: Decision Making and Action Selection in Cyberspace. Hum. Factors 2015, 57, 721–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edeh, N.C. Cybersecurity and Human Factors: A Literature Review. In Cybersecurity for Decision Makers; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Ng, B.-Y.; Kankanhalli, A.; Xu, Y. Studying Users’ Computer Security Behavior: A Health Belief Perspective. Decis. Support. Syst. 2009, 46, 815–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraemer, S.; Carayon, P.; Clem, J. Human and Organizational Factors in Computer and Information Security: Pathways to Vulnerabilities. Comput. Secur. 2009, 28, 509–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, H.; Xue, Y. Understanding Security Behaviors in Personal Computer Usage: A Threat Avoidance Perspective. J. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2010, 11, 394–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaltegger, T.; Ambuehl, B.; Bosshart, N.; Bearth, A.; Ebert, N. Human Behavior in Cybersecurity: An Opportunity for Risk Research. J. Risk Res. 2025, 28, 843–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slovic, P. Perception of Risk. Science 1987, 236, 280–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slovic, P.; Finucane, M.L.; Peters, E.; MacGregor, D.G. Risk as Analysis and Risk as Feelings: Some Thoughts about Affect, Reason, Risk, and Rationality. Risk Anal. 2004, 24, 311–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sjöberg, L. Explaining Individual Risk Perception: The Case of Nuclear Waste. Risk Manag. 2004, 6, 51–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savadori, L.; Lauriola, M. Risk Perception and Protective Behaviors During the Rise of the COVID-19 Outbreak in Italy. Front. Psychol. 2021, 11, 577331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fischhoff, B.; Slovic, P.; Lichtenstein, S.; Read, S.; Combs, B. How Safe Is Safe Enough? A Psychometric Study of Attitudes towards Technological Risks and Benefits. Policy Sci. 1978, 9, 127–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fife-Schaw, C.; Rowe, G. Public Perceptions of Everyday Food Hazards: A Psychometric Study. Risk Anal. 1996, 16, 487–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caserotti, M.; Girardi, P.; Rubaltelli, E.; Tasso, A.; Lotto, L.; Gavaruzzi, T. Associations of COVID-19 Risk Perception with Vaccine Hesitancy over Time for Italian Residents. Soc. Sci. Med. 2021, 272, 113688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aakko, E. Risk Communication, Risk Perception, and Public Health. WMJ 2004, 103, 25–27. [Google Scholar]

- Wachinger, G.; Renn, O.; Begg, C.; Kuhlicke, C. The Risk Perception Paradox—Implications for Governance and Communication of Natural Hazards. Risk Anal. 2013, 33, 1049–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Li, Y. Factors Influencing Public Risk Perception of Emerging Technologies: A Meta-Analysis. Sustainability 2023, 15, 3939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Schaik, P.; Jeske, D.; Onibokun, J.; Coventry, L.; Jansen, J.; Kusev, P. Risk Perceptions of Cyber-Security and Precautionary Behaviour. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 75, 547–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rimal, R.N.; Real, K. Perceived Risk and Efficacy Beliefs as Motivators of Change. Hum. Commun. Res. 2003, 29, 370–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwesig, R.; Brich, I.; Buder, J.; Huff, M.; Said, N. Using Artificial Intelligence (AI)? Risk and Opportunity Perception of AI Predict People’s Willingness to Use AI. J. Risk Res. 2023, 26, 1053–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinstein, N.D. Unrealistic Optimism about Future Life Events. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1980, 39, 806–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinstein, N.D. Optimistic Biases About Personal Risks. Science 1989, 246, 1232–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwarzer, R. Optimism, Vulnerability, and Self-Beliefs as Health-Related Cognitions: A Systematic Overview. Psychol. Health 1994, 9, 161–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, M.; Jeong, J. Optimistic Bias: Concept Analysis. Res. Community Public Health Nurs. 2024, 35, 112–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Yuan, Y. The Impact of Ignorance and Bias on Information Security Protection Motivation: A Case of e-Waste Handling. Internet Res. 2023, 33, 2244–2275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Turel, O.; Yuan, Y. E-Waste Information Security Protection Motivation: The Role of Optimism Bias. Inf. Technol. People 2022, 35, 600–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhee, H.-S.; Ryu, Y.U.; Kim, C.-T. Unrealistic Optimism on Information Security Management. Comput. Secur. 2012, 31, 221–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatoki, J.G.; Shen, Z.; Mora-Monge, C.A. Optimism amid Risk: How Non-IT Employees’ Beliefs Affect Cybersecurity Behavior. Comput. Secur. 2024, 141, 103812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.-X.; Hwang, B.-G. Charting the Unseen: A Systematic Review of Risk Perception in Emerging Technologies. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2025, 72, 3832–3848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogbanufe, O.; Kim, D.J. “Just How Risky Is It Anyway?” The Role of Risk Perception and Trust on Click-through Intention. Inf. Syst. Manag. 2018, 35, 182–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parkin, S.; Kuhn, K.; Shaikh, S.A. Executive Decision-Makers: A Scenario-Based Approach to Assessing Organizational Cyber-Risk Perception. J. Cybersecur. 2023, 9, tyad018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Buchner, A.; Lang, A.-G. Statistical Power Analyses Using G*Power 3.1: Tests for Correlation and Regression Analyses. Behav. Res. Methods 2009, 41, 1149–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barattucci, M.; Ramaci, T.; Matera, S.; Vella, F.; Gallina, V.; Vitale, E. Differences in Risk Perception Between the Construction and Agriculture Sectors: An Exploratory Study with a Focus on Carcinogenic Risk. La Med. Del Lav. 2025, 116, 16796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egelman, S.; Peer, E. Scaling the Security Wall: Developing a Security Behavior Intentions Scale (SeBIS). In Proceedings of the 33rd Annual ACM Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 18 April 2015; pp. 2873–2882. [Google Scholar]

- Larsen, M.H.; Lund, M.S. Cyber Risk Perception in the Maritime Domain: A Systematic Literature Review. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 144895–144905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Schaik, P.; Jansen, J.; Onibokun, J.; Camp, J.; Kusev, P. Security and Privacy in Online Social Networking: Risk Perceptions and Precautionary Behaviour. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2018, 78, 283–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhee, H.-S.; Ryu, Y.; Kim, C.-T. I Am Fine but You Are Not: Optimistic Bias and Illusion of Control on Information Security. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Information Systems, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 11–14 December 2005; Volume 32. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, J.; Greenauer, N.; Macaluso, K.; End, C. Unrealistic Optimism in Internet Events. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2007, 23, 1273–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, J.D.; Weems, C.F.; Ahmed, I.; Richard, G.G., III. Self-Reported Secure and Insecure Cyber Behaviour: Factor Structure and Associations with Personality Factors. J. Cyber Secur. Technol. 2017, 1, 163–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cain, A.A.; Edwards, M.E.; Still, J.D. An Exploratory Study of Cyber Hygiene Behaviors and Knowledge. J. Inf. Secur. Appl. 2018, 42, 36–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, A.B.; Kumar, V.; Spyropoulou, S. Identifying the Public’s Beliefs About Generative Artificial Intelligence: A Big Data Approach. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2025, 72, 827–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).