Abstract

Hashes are vital in limiting the spread of child sexual abuse material online, yet their use introduces unresolved technical, legal, and ethical challenges. This paper bridges a critical gap by analyzing both cryptographic and perceptual hashing, not only in terms of detection capabilities, but also their vulnerabilities and implications for privacy governance. Unlike prior work, it reframes CSAM detection as a multidimensional issue, at the intersection of cybersecurity, data protection law, and digital ethics. Three key contributions are made: first, a comparative evaluation of hashing techniques, revealing weaknesses, such as susceptibility to media edits, collision attacks, hash inversion, and data leakage; second, a call for standardized benchmarks and interoperable evaluation protocols to assess system robustness; and third, a legal argument that perceptual hashes qualify as personal data under EU law, with implications for transparency and accountability. Ethically, the paper underscores the tension faced by service providers in balancing user privacy with the duty to detect CSAM. It advocates for detection systems that are not only technically sound, but also legally defensible and ethically governed. By integrating technical analysis with legal insight, this paper offers a comprehensive framework for evaluating CSAM detection, within the broader context of digital safety and privacy.

1. Introduction

The proliferation of CSAM online presents a grave challenge to society, necessitating innovative and effective technological interventions to combat its dissemination. Traditional methods of identifying and removing CSAM, such as manual review and signature-based detection, often struggle to keep pace with the sheer volume of content being generated and shared across various platforms. The limitations of manual filtering underscore the need for automated tools capable of detecting and blocking sensitive content [1].

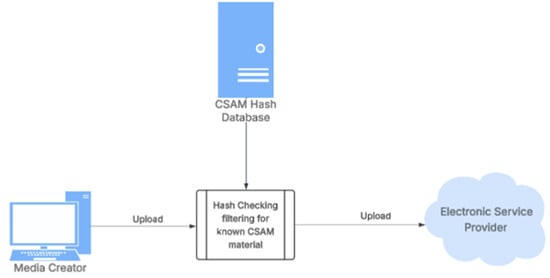

Thus, image hashing plays a vital role in the global effort to combat CSAM, enabling the automated detection of illegal content, even when that content has been subtly modified to evade traditional filters. Once an offending image or video is detected, either manually or through automation, a unique digital signature is generated from the content. This signature, commonly known as a hash (also referred to as a fingerprint, message digest, hash value, hash code, or hash sum), acts as a compact identifier. Each subsequent upload is hashed in the same manner, and the resulting value is compared against a Digital Service Provider (DSP), such as Platform, Apps, Cloud Services, etc. If a match is found, the content can be automatically blocked or handled according to the service provider’s policy, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

CSAM filtering by platforms and electronic service provider before uploading.

That being said, the convergence of hashing technology and privacy law represents a critical interdisciplinary frontier, demanding mutual literacy between technologists and legal scholars. The hashing algorithmic process that transforms data into fixed-length representations plays a pivotal role in anonymization, data integrity, and secure identity verification. Yet its deployment within privacy-preserving systems raises complex legal questions about identifiability and compliance with the EU law. This paper aims to bridge the conceptual divide: offering technologists a nuanced understanding of legal thresholds for personal data and equipping legal researchers with a technical foundation to evaluate the robustness and limitations of hashing-based safeguards.

2. Cryptographic and Perceptual Hashes: State of the Art

Hashing technologies can be broadly categorized into cryptographic and perceptual hashes, each serving distinct purposes within digital systems. Cryptographic hashes are designed for data integrity and security, producing unique irreversible outputs that change drastically with even the slightest input variation. They are foundational to authentication protocols, blockchain systems, and secure data storage. In contrast perceptual hashes are engineered to identify visually similar multimedia content tolerating minor edits, such as cropping or compression. These are particularly useful in content moderation and duplicate detection. The hashing usage emerged around 1967 in the context of data processing [2]. Early on, in the 1980s, authors [3] have laid the theoretical groundwork in image processing and feature extraction for perceptual similarity analysis, based on edge detection using the Laplacian of Gaussian filter, inspired by early human vision models. In early 2000s [4,5,6], researchers began exploring robust image hashing techniques that could tolerate minor edits (e.g., resizing or compression).

A key milestone in the adoption of image hashing in the context of image authentication and content-based image retrieval was in 2007 when a review article in the Journal of Shanghai University [7] highlighted the growing interest in perceptual hashing. Two years later Microsoft and Dartmouth College, with leading scientist Hany Farid [8] developed PhotoDNA, a perceptual hashing system to detect CSAM. This marked a major real-world deployment of perceptual hashing at a scale, and since then, the use of the hashing method remains a cornerstone method in preventing the redistribution of known harmful media, such as CSAM [9,10]. But apart from data matching of multimedia online, other applications of hashing include efficient data storage (removal of duplicates), efficient retrieval, and data integrity for computer forensics and law enforcement agencies.

A well-designed hash algorithm must incorporate the following essential properties to ensure optimal performance:

- Deterministic: The same input always produces the same output, to ensure that a multimedia is identifiable on its hash.

- Hash Length: Compact and fast to compute, even for large inputs.

- Computational Efficiency: The computational cost of comparing hashes should be low, to guarantee applicability on large social media platforms.

- Distinct: The hashes of two distinct multimedia files should themselves be distinct to avoid or minimize coalitions.

- Non-reversible: Hashes should be irreversible. Given a hash output, it should be infeasible to reverse-engineer the original input; this allows hashes of illegal content to be shared across different organizations to eliminate known malicious material.

- Secure: Test resistance to adversarial attacks.

2.1. Perceptual Hashes

Perceptual hashing is a technique used to generate a compact fingerprint of multimedia content, like images, audio or video, based on its visual or auditory features, rather than its exact binary data. Unlike cryptographic hashes, perceptual hashes are designed to remain similar for similar content [11,12]. This property of perceptual hashes makes them ideal to detect visually similar but altered content (e.g., resized, cropped, slightly edited) and help identify variants of known CSAM that might bypass traditional detection methods.

2.1.1. Perceptual Image Hashes

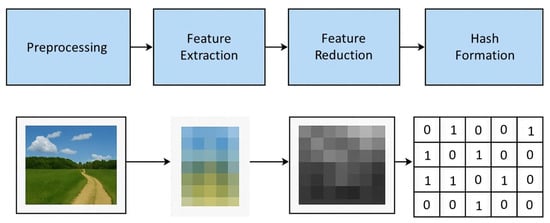

The way to create the perceptual image hashes is by extracting the visual characteristics of an image or a video [9]. Perceptual characteristics refer to features that align with how humans visually interpret content, such as color, texture, etc. These characteristics can be color-based features, textural and structural features, or frequency-based components, or other features (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Standard workflow for generating a perceptual hash.

The most widely known perceptual hash is the so-called Perceptual Hash (pHash), which was developed in the early 2000s [6]. The pHash is the most widely cited and evaluated among all the other perceptual hashing algorithms. Notable implementation of the pHash can be found on phash.org [13]. The algorithm operates by applying the Discrete Cosine Transform (DCT) to a grayscale version of the image, capturing its low-frequency components that represent the image’s overall structure and tone. Below is a step-by-step breakdown of the algorithm’s procedure:

- Convert Image to Grayscale

- Removes color information to focus on structure and brightness.

- Simplifies processing by reducing the image to a single intensity channel.

- Resize Image

- Resize to a standard size typically 32 × 32 pixels.

- This balances detail retention with computational efficiency.

- Apply Discrete Cosine Transform DCT

- DCT converts spatial data into frequency components.

- Captures the image’s low frequency features that encapsulate its global structure, and discards high frequency elements, typically associated with fine-grained noise.

- Extract Top-Left 8 × 8 DCT Coefficients

- These represent the lowest frequencies which are most resilient to changes like compression or scaling.

- Ignore the DC coefficient (top-left value) as it represents average brightness.

- Compute the Average Value

- Calculate the mean of the 64 DCT values (excluding the DC coefficient).

- This average becomes the threshold for binarizing the hash.

- Generate Binary Hash

- For each of the 64 DCT values if the value > average, then the hash value adds 1, if the value < average, then the hash value adds 0.

- Result is a 64-bit binary string, representing the image’s perceptual fingerprint.

Another widely used algorithm, due to its simplicity and speed, is Average Hash (aHash). It was also developed in the early 2000s from the developer’s community, and it was popularized in the academic literature by [14]. The key idea of the algorithm is to compare pixels’ brightness to average. One more alternative approach with broad adoption is the Difference Hash (dHash) technique, which measures brightness differences between adjacent pixels. It is included in the library of hash algorithms created by Buchner [15] and together with aHash, they are extremely popular due to their simplicity and speed, especially in open-source and teaching contexts.

Although these pioneering algorithms mentioned above initiated the perceptual hashing era, extensive research has been conducted in the following years until today. Different studies have been carried out to evaluate the plethora of hashing algorithms [16,17,18,19,20,21]. Meanwhile, perceptual hashing systems encompass a diverse range of approaches, each with distinct design choices and performance traits [22]. Perceptual hashing algorithms can be broadly categorized based on their underlying approach to feature representation and transformation:

- Pixel-based methods, such as aHash [14], dHash [15], and Block Mean Hash [23], rely on direct comparisons of pixel intensity values and are prized for their simplicity and speed, though they are more sensitive to small changes.

- In contrast, frequency-based methods like pHash [6], DCT Hash [24], and Wavelet Hash [25] transform images into the frequency domain using techniques such as the Discrete Cosine Transform (DCT) or wavelets, yielding greater robustness to compression and subtle distortions.

- Statistical feature hashes, including Color Moment Hash [26] and Radial Variance Hash [27], leverage properties such as color distribution or radial symmetry and typically require normalization and vector quantization.

- Matrix decomposition approaches, exemplified by SVD Hash [28], use singular value decomposition to extract dominant structural components, enabling compact representations.

- Keyed/randomized hashes introduce controlled randomness, e.g., secure pHash [29] to enhance resistance against adversarial manipulation.

- With the advent of machine learning, deep learning-based hashes like CNN Hashes [30,31] and NeuralHash developed by Apple [21] employ convolutional neural networks to learn semantic features, offering high robustness at the cost of computational intensity.

- Finally, hybrid or custom techniques, such as PhotoDNA developed by Microsoft [8], PDQ developed by Meta [32], and Stable Signature conceived by Meta AI Research [33], integrate multiple approaches—statistical, frequency, semantic, and even metadata-aware—to optimize performance across diverse application domains like content moderation, duplicate detection, and copyright enforcement.

Table 1 summarizes all the different image hashing techniques, as well as their strengths and weaknesses.

Table 1.

Clustered comparison of image hashing approaches.

2.1.2. Perceptual Hashing Techniques for Videos

Video hashing techniques [34] aim to generate compact and robust representations of video content for tasks such as duplicate detection, tamper identification, and content-based retrieval. With the sheer volume of uploads—often in real time—these algorithms must be both robust and lightweight, handling everything from memes and reaction clips to professionally produced content. And as trends evolve in seconds, social media platforms rely heavily on smart, scalable video hashing systems to keep up.

The techniques that are used can be broadly categorized into Spatial Domain Techniques (frame-based), Temporal Domain Methods, and Spatio-Temporal Domain Hybrid techniques (feature aggregation). Spatial Domain Techniques extract hash values from selected key frames of a video, often treating them as static images. These frames are processed using perceptual image hashing methods such as pHash or aHash or PDQ, TMK-PDQF [35] to generate compact binary representations. This approach is computationally efficient and well-suited for video deduplication and indexing, especially when video content exhibits minimal temporal variation. However, it offers limited robustness against frame reordering, tampering, or temporal distortions.

Temporal Domain Methods analyze frame-to-frame changes such as motion vectors, luminance differences and temporal ordinal measures. These approaches capture motion dynamics but are less effective for short-duration or heavily edited videos.

Spatio-Temporal Domain hybrid techniques combine spatial and temporal features, e.g., Videntifier [36]. This type of technique also includes models like CNNs, RNNs, or 3D CNNs [37]. These offer improved robustness against both geometric and content preserving transformations, but have a high computational cost.

According to [34], the key challenges of choosing the techniques are the trade-off between robustness and discriminability, the high computational cost for deep models and the insufficient performance under geometric attacks, e.g., cropping and rotation. These challenges are further intensified in the context of social media platforms, where vast volumes of user-generated content are uploaded daily. The sheer scale and variety of data-including images, videos and multimedia-posts demand methods that can withstand frequent modifications and compressions, while still maintaining high fidelity and traceability.

The effective deployment of video hashing systems is significantly hampered by one more under-addressed yet pivotal research challenge, namely benchmark standardization. This challenge is also true for image hashing and is pinpointed in many reviews. The hashing research field lacks unified evaluation benchmarks with curated datasets and consistent transformation protocols, as highlighted in community discussions [38]. Without a shared set of test sequences and distortion pipelines, researchers’ reports that compare performance, remain unreliable and non-reproducible. There are some initial efforts such as PHVSpec [39], which is a benchmark for video perceptual hashes developed by the Tech Coalition, which seeks to bring structure and repeatability to this problem space. Nonetheless, far more comprehensive and publicly accessible frameworks both for image hashing and video hashing are required.

2.1.3. Distance Metrics for Perceptual Hashes

In the context of hashing-based similarity detection, the choice of distance or similarity metric plays a pivotal role in assessing the perceptual closeness of hashed representations. A well-aligned metric ensures that semantically similar inputs yield proximate hash values, thereby optimizing the balance between discrimination power and robustness to benign transformations or noise.

Binary hash outputs are commonly compared using Hamming distance [40], which quantifies the number of bit positions at which two hash codes differ, an efficient metric for evaluating visual similarity in perceptual hashing. For real-valued or vector-based hashes, metrics such as Euclidean distance [41] and Cosine similarity [42] are employed to capture geometric or angular relationships between embeddings. These metrics influence retrieval precision, especially in high-dimensional spaces.

When it comes to specific hashing algorithms, binary hashes like aHash, dHash, and PDQ typically use Hamming distance, which is efficient and ideal for quick bitwise comparisons. pHash and wHash deploy either Hamming distance or normalized Hamming distance. Normalized Hamming distance is computed as the Hamming distance, but it is divided by the length of the hashing strings, so it represents the proportion of different strings, or the percentage of mismatches. Vector-based hashes such as Wavelet Hash, Color Moment Hash, and SVD Hash often rely on metrics like Euclidean or Cosine distance capturing more nuanced geometric relationships. Moreover, algorithms like PhotoDNA leverage custom distance metrics, indicating a domain-specific approach, often optimized for robustness and perceptual relevance. Finally, CNN-based hashes use other distance metrics, like Normalized Convolution Distance [43].

2.2. Cryptographic Hashes

Cryptographic hash functions (also cold hard hashing) are mathematical algorithms that take an input of any size and produce a fixed-sized output called hash (or hash value, or digest or checksum or fingerprint) [44]. Unlike perceptual hashing, cryptographic hashing has one more very important property, namely the “avalanche effect”. The avalanche effect is a crucial property of cryptographic hash functions and encryption algorithms. It ensures that a tiny change in the input (e.g., changing a single bit) produces a drastically different output hash. This is important because it makes it extremely difficult for attackers to predict or reverse-engineer the input based on the output; it helps prevent two different inputs from producing the same hash (a collision); and it ensures that even the smallest tampering with data is detectable.

The most widely known cryptographic algorithms are MD5 [45] and SHA1 [46]. The MD5 message-digest algorithm is a widely used hash function producing a 128-bit hash value. MD5 was designed by Ronald Rivest in 1991 and was specified in 1992 as RFC 1321 from the Internet Engineering Task Force [45]. SHA-1 (Secure Hash Algorithm 1) is a cryptographic hash function that produces a 160-bit hash value, often represented as a 40-character hexadecimal number. It was designed by the U.S. National Security Agency and is a U.S. Federal Information Processing Standard [47].

Both cryptographic hash functions have been found to break core promise [48,49,50], that each input should have a unique hash, and thus are vulnerable to collision attacks and are both deprecated [51]. Nonetheless, because of the widespread adoption and the backward compatibility they offer, they are still widely used. These algorithms were once industry standards, baked into countless systems, protocols, and libraries, whereas updating legacy systems can be costly or risky, so many organizations adhere to what already works.

The two standards that include the nowadays secure cryptographic hash algorithms are FIPS 180-4 [52] and FIPS 202 [53]. The SHA families that are considered secure hash algorithms are SHA-2 (including SHA-256 and SHA-512, widely used in TLS, SSL, blockchain, and digital signatures) and SHA-3 (offers similar output sizes to SHA-2 but uses a different internal structure for enhanced security).

3. Legal Classification of Hashes in CSAM Detection Frameworks Under the European Legal Order

From a legal standpoint, the property that a cryptographic hash cannot be reverse-engineered from its output, implies that it is not possible to identify a person by reconstructing the original material. However, when assessing whether a hash qualifies as personal data, it is essential to consider the specific context in which the hash is processed, particularly within systems designed to combat CSAM.

In such contexts, hashes are frequently accompanied by annotations or metadata which, although not directly related to the identifiable child victim whose image has been hashed, may nevertheless contain contextual information for the age classification and the resulting facilitation of the victim identification process [54]. Hence, when combined with additional information, such as annotations or metadata, cryptographic hashes may be linked to identifiable persons, thereby qualifying as personal data under article 4 of the GDPR [55].

Another illustrative case is the annotated hash databases maintained by Law Enforcement Agencies (LEAs) which may include case file identifiers that could enable the linking of a hash with a particular perpetrator. This linkage permits identification, transforming what would otherwise be anonymized data into personal data.

According to the GDPR framework, the determination of whether a hash value constitutes personal data does not rest on the intrinsic format of the hash itself. Although a hash may appear to be pseudonymous, it qualifies as personal data according to recital 26 of the GDPR, if it is derived from information relating to an individual and in case there remains a realistic possibility of re-identification, either by the data controller or by a third party, using reasonably available means [55]. In this regard, hashing is recognized as a form of pseudonymization, not anonymization [56].

More specifically, cryptographic algorithms typically constitute a type of “pseudonymizing transformation” [56]. However, relying on non-keyed cryptographic functions does not provide a robust method of pseudonymization. For instance, SHA-256 alone is deterministic and does not involve any secret key or salt, making it vulnerable to brute-force or dictionary attacks. Hence, although cryptographic functions play an important role in ensuring data integrity and accuracy, they are regarded as a weak pseudonymization method [57].

Nevertheless, even though the primary purpose of hashing may be to identify images, rather than to protect personal data through pseudonymization, its widespread use by online service providers and LEAs does not exempt the associated hash databases from the unequivocal requirement to comply with the provisions of the GDPR (and Directive 2016/680 (https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32016L0680 (accessed on 28 October 2025) when required). Considering this, it is worth noting that the use of a weak pseudonymization technique is not inherently prohibited; however, such use must be accompanied by appropriate and effective technical and organizational measures to ensure the protection of personal data. More precisely, the key obligation under the GDPR, as set forth in recital 28, is to ensure that the risk to data subjects’ rights and freedoms is mitigated to a level appropriate to the processing context [55], whether through pseudonymization, other protective measures, or a combination thereof. Accordingly, cryptographic pseudonymization methods that operate without relying on secret keys or salts, although supplemented by separately stored additional identifying information, may constitute a GDPR-compliant pseudonymization technique, if appropriate safeguards are in place to prevent the unauthorized use of the additional information and control the flow of pseudonymized data to the extent possible [56].

In parallel, it must be ensured that the reversal of the pseudonymization by unauthorized third parties lacking access to “additional information” is not straightforward [58]. “Additional information” according to article 4 (5) of the GDPR refers to the link between the initial identifiers of the data subjects and the pseudonyms [55]. It is imperative that this association be secured and kept separate from the pseudonymized data by the data controller. Thus, appropriate measures need to be put in place to prevent unauthorized access to the association between pseudonyms and initial identifiers, by storing them, for instance, in separate databases [59]. To achieve a high level of protection for data subjects’ identities, such a linkage should be secured and not easily identifiable by anyone with access solely to the pseudonymized data.

In the case of LEAs, intermediary service providers, and organizations for the protection of children’s rights, hash databases are widely used for the detection of CSAM, with or without an integrated annotation layer. According to the above, even if the hash database includes categorical annotations or metadata, it should be maintained separately from any additional information that, when combined with an annotated hash, could lead to the identification of an individual.

4. Systems and Databases That Deploy Hashes of Illegal CSAM

The detection of CSAM and duplicate media content has become a top priority for governments, technology companies, and child protection agencies worldwide [58]. To address this, a variety of hash-based systems and databases have been developed that enable the identification of known illegal or previously flagged content, without requiring direct access to the original files. These systems leverage perceptual and cryptographic hashing and increasingly machine learning-assisted matching, to recognize media even after transformations, such as resizing, re-encoding or partial obfuscation. Below are described some of these systems, used to combat CSAM online.

4.1. PhotoDNA Cloud Service

PhotoDNA is a perceptual image hashing system developed by Microsoft Research and Hany Farid around 2009 [60]. It converts images to grayscale, divides them into a grid and applies DCT-based processing to generate robust 1152-bit hashes. These hashes are resilient to common transformations such as resizing compression and color shifts.

PhotoDNA is widely used by tech platforms Microsoft, Google, Facebook, Reddit, as well as by NGOs and law enforcement enabling the automated detection of known CSAM through centralized hash databases maintained in collaboration with NCMEC.

Microsoft has long maintained that PhotoDNA hashes are not reversible and has kept the algorithm secret. Although the European Commission [61] and the European Parliamentary Research Service [62] conflate to some extent cryptographic and perceptual hashes’ traits, they do underscore the irreversibility trait of the PhotoDNA hashes, too. However, recent research directly challenges that claim [12]. Specifically, Athalye [63] developed a machine learning-based model that partially reconstructs blurred thumbnail versions of images from PhotoDNA hashes, leveraging reverse-engineered steps. Later, Madden et al. [64] demonstrated that GAN-based inversion attacks can reconstruct perceptually similar pre-images, even retrieving recognizable facial and scene features and achieve up to 100% similarity under certain perceptual metrics [12]. These findings reveal that perceptual hashes of personal data must be treated as personal data, too.

4.2. PDQ/TMK + PDQF (Meta/Facebook)

In 2019, Facebook open-sourced the PDQ image perceptual hash and the TMK + PDQF video hashing framework [32]. PDQ generates compact image hashes, while TMK + PDQF applies PDQF frame-level, floating-point descriptors combined using temporal matching kernels, enabling the robust detection of duplicate or manipulated media. The system is optimized for penal-moderation workflows, real-time performance, and integration within law enforcement and content platforms.

Recent research has demonstrated that it is possible to both evade detection and construct second-preimage attacks, where an attacker creates a different image that produces the same PDQ hash, as a known target. In particular, Prokos et al. [65] showed that attackers can generate such collisions with imperceptible visual changes, thereby undermining the reliability of PDQ in client-side scanning and moderation systems.

Furthermore, machine learning-based inversion attacks [64,66] have also been explored, wherein approximate reconstructions of original images are synthesized from PDQ hash values. Although these reconstructions are often low-resolution and visually degraded, they raise privacy concerns. These findings challenge the assumption that PDQ hashes are irreversible or secure, and they highlight the need for stronger integrity guarantees in perceptual hashing-based moderation.

4.3. INTERPOL ICSE Database and ICCAM/INHOPE

The International Child Sexual Exploitation (ICSE) database [67], run by INTERPOL and supported by the INHOPE Network of hotlines [68], supports global victim identification and investigative collaboration across more than 70 countries. It integrates PhotoDNA and other perceptual and cryptographic hashes to compare image and video hashes, enabling investigators to identify duplicated content, victims, or locations’ jurisdictions. According to INTERPOL, by 2022–2023, more than 30,000 victims had been identified globally via the system.

Furthermore, the ICCAM platform, operated by INHOPE, is hosted at INTERPOL’s headquarters in Lyon. All CSAM entered into ICCAM is systematically shared with INTERPOL’s ICSE database to support victim identification efforts. The ICCAM platform stores mainly cryptographic hashes, e.g., SHA-1 and MD5.

4.4. Google CSAI Match (YouTube)

CSAI Match [69] is Google/YouTube’s proprietary video hashing system specifically designed to detect previously known CSAM videos across partner platforms. CSAI Match identifies segments of video content that closely resemble known CSAM, including exact duplicates detectable by MD5 hash matching, as well as near duplicates, resulting from re-encoding, obfuscation, truncation, or scaling.

Partners run a hashing tool locally to generate a digital signature, which is then compared via API against YouTube’s repository of verified abusive content. Upon a match, manual review is conducted before takedown, allowing real-time and scalable detection across high-volume uploads, protecting children.

4.5. Apple NeuralHash

NeuralHash was a deep perceptual hashing algorithm proposed by Apple in 2021 for on-device detection of known CSAM images. It maps each image to a 96-bit binary hash via a CNN feature extractor, followed by a learned hashing projection. However, Struppek et al. [21] demonstrated that NeuralHash is susceptible to hash collisions and evasion attacks: adversaries can manipulate images via gradient-based or simple transformations to force a desired hash match or avoid detection altogether, thus enabling both the hiding of illicit content and framing of innocent users. NeuralHash remained paused and eventually canceled in December 2022 due to strong privacy concerns [70], as NeuralHash performed the image hashing and comparison directly on the device.

4.6. IWF Hash Database

The Internet Watch Foundation (IWF) [71] operates one of the most widely used hash databases dedicated to the detection and removal of CSAM online. Based in the United Kingdom, the IWF hash list is a trusted dataset of cryptographic and perceptual hashes derived from confirmed illegal images and videos, curated through both human analyst review and international reports. The database supports industry, cloud providers, and social media platforms in proactively scanning user-uploaded content for known CSAM, often before it becomes publicly accessible. The IWF distributes its hash list to vetted partners under strict legal and technical agreements to prevent misuse or unauthorized access. The hashes contained on the list are compatible with various detection systems, including MD5, PhotoDNA, and other perceptual hashing algorithms, ensuring interoperability with client-side and server-side moderation systems. The IWF hash database has been integrated into systems like Microsoft’s PhotoDNA Cloud Service, Meta’s content moderation pipeline, and global law enforcement initiatives.

4.7. NCMEC CyberTipline

The National Center for Missing & Exploited Children (NCMEC) operates one of the world’s most comprehensive and authoritative hash databases of CSAM [72]. Based in the United States, NCMEC’s CyberTipline serves as a central intake point for reports of suspected child exploitation from the public, electronic service providers, and law enforcement. When CSAM is verified by NCMEC analysts, the imagery is hashed using both cryptographic algorithms (such as MD5 and SHA-1) and perceptual hashing algorithms like PhotoDNA. These hashes are then distributed to vetted technology partners such as Google, Meta, and Microsoft under strict legal frameworks to enable proactive detection and blocking of known illegal imagery across digital platforms. NCMEC’s hash database is a cornerstone of global CSAM mitigation efforts and is also integrated into systems like Thorn’s Safer Match [73], Project Arachnid [74], and INTERPOL’s ICSE platform. The combination of human verification and scalable hash sharing allows for highly accurate identification and takedown of CSAM, reducing re-victimization and improving global child protection.

4.8. Arachnid Project

Project Arachnid is a proactive web-crawling and CSAM detection system operated by the Canadian Centre for Child Protection (C3P) [74]. Launched in 2017, it is designed to detect, report, and facilitate the removal of known illegal content across the internet by leveraging a combination of perceptual hashing technologies (e.g., PhotoDNA, PDQ) cryptographic hashes SHA1 and SHA256, and automated web crawlers. Unlike traditional reactive models that rely on manual reporting, such as INHOPE Association, Arachnid continuously scans public URLs, image boards, file-hosting sites, and forums for visual material that matches a curated hash database of verified CSAM. When a match is found, it automatically issues a notice to service providers and records metadata about the content’s location and persistence.

4.9. Web-IQ Hash Check Server (HCS)

The Hash Check Server (HCS) is Web-IQ’s proprietary hash-matching service [75] designed to detect known CSAM images and videos across platforms used by law enforcement, NGOs, and electronic service providers. Powered by Web-IQ’s OSINT intelligence and supported by the LIBRA project [76], the HCS enables real-time comparison of uploaded content against a curated hash database, allowing organizations to proactively block or flag illegal media prior to public access. Notably, HCS allows partners to scan platforms including the darknet and surface web without ever viewing or storing CSAM themselves, preserving both legal compliance and user privacy. As part of operational deployment, billions of media items have been processed, resulting in the confirmation and removal of millions of CSAM images and videos globally.

4.10. Thorn’s Safer Match

Thorn’s Safer Match [73] is a cloud-based content moderation service designed to detect and prevent the spread of CSAM using perceptual hashing and AI-enhanced matching techniques. Developed by the nonprofit organization Thorn, Safer Match provides an API-accessible platform that allows platforms and service providers to scan images and videos against a curated set of known CSAM hashes. The system incorporates scene-sensitive perceptual hashing, which breaks video content into semantically meaningful segments and computes hashes per segment, enabling high recall and precision even for partially altered or obfuscated material. Importantly, Safer Match is integrated with international databases such as those from NCMEC and allows partners to contribute their own verified hash sets to the detection pipeline.

5. Risks of Systems and Databases That Use Perceptual Hashes

5.1. Limitations in Robustness/Sensitivity to Modifications

While designed to handle minor changes, perceptual hashes can sometimes fail to match content that has been slightly altered, leading to both false negatives and false positives [66]. This type of attack is targeting hashing robustness, and according to literature, 99.9% of images could be modified in such a way, to bypass detection, while preserving their visual content [77]. This poses significant challenges, not only for technical enforcement, but also for legal compliance, particularly under data protection and content moderation laws. For instance, platforms relying on perceptual hashing to detect illicit material such as CSAM, may inadvertently breach regulatory obligations if modified content escapes detection undermining due diligence obligations under statutes, like the EU Digital Services Act.

5.2. Collision Attacks/Poisoning Attacks

A hash collision occurs when two different inputs produce the same hash output. Since hash functions are supposed to uniquely represent data, this undermines their integrity and opens the door to malicious exploits. It is feasible to create different images that result in identical perceptual hashes, potentially allowing malicious content to bypass filters [12]. This can lead to so-called poisoning attacks, where the aim is to generate false positives through the manipulation of targeted collisions, challenging the collision resistance [66].

From a legal standpoint, such attacks could complicate the enforcement of online regulations, such as the DSA, while weakening perceptual hashing may constitute a systemic risk and failure to implement appropriate mitigation measures may amount to non-compliance. If malicious actors intentionally exploit hash collisions to bypass filters, they may expose organizations to liability for failing to prevent the dissemination of harmful content complicating the legal landscape around platform accountability and user protection. Such practices may also lead to chilling effects, impacting the fundamental right to freedom of expression as enshrined under article 11 of the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the EU, while also constituting a systemic risk under the DSA (DSA, article 34).

5.3. Hash Inversion

Research indicates that it is possible to reconstruct original images from their perceptual hashes, compromising user privacy [12]. Researchers have demonstrated several methods to conduct inversion attacks, like adversarial machine learning (using neural networks to generate images that match target hashes), black box attacks (iteratively modifying images without knowing the hash function internals), and generative models training AI to reconstruct likely inputs from perceptual hashes [64].

From a legal perspective, these vulnerabilities pose significant risks to data subjects’ privacy and personal data protection. If attackers can reverse-engineer original images from perceptual hashes, sensitive personal information may be exposed. Additionally, this kind of attack could challenge the effectiveness of privacy safeguards in platforms relying on hash-based technologies for content moderation or user data protection. The legal implications could extend to liability for organizations that fail to implement stronger cryptographic measures to prevent such privacy breaches.

5.4. Data Storage and Handling/Data Leakage

Storing perceptual hashes can inadvertently expose sensitive information if not properly secured. The retention of user data and flagged content also raises privacy issues. The General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) in Europe imposes strict requirements on data collection, processing, and retention, emphasizing the importance of data minimization, lawful processing, and the right to be forgotten. Platforms and other DSPs must ensure that CSAM detection processes adhere to these principles to prevent the misuse of personal data, and specifically perceptual hashes must be treated as almost as sensitive as original images. Controllers should determine a precise storage period, and if this is not feasible, they should set strict time limits for a periodic review (GDPR, recital 39, article 5 (1) (e)). In parallel, given the seriousness of child sexual abuse allegations, data generated from false positives must be erased, except for what is necessary to improve automated detection tools [61].

6. Ethical Considerations and the Proposed CSAR Regulation of the European Commission

Numerous online technology platforms in Europe have been voluntarily employing hash technologies [78] for over a decade to automatically detect previously known CSAM on their services. This valuable practice for countering the relentless spread of known CSAM was at risk of being discontinued due to the wording of the e-Privacy Directive, as it could amount to users’ privacy rights infringement. Specifically, the e-Privacy Directive [79], as construed in light of the GDPR, strictly limits the monitoring and processing of electronic communications, protecting confidentiality and permitting exceptions only under narrowly defined conditions with explicit legal authorization at the national or EU level. As a result, the voluntary deployment of CSAM detection technologies risked being deemed unlawful interception or processing of confidential communications, as it lacked an explicit legal exception under these provisions. To ensure that service providers can detect CSAM within their services, the interim Regulation (EU) 2021/1232 on a temporary derogation from certain provisions of the e-Privacy Directive came into effect on 2 August 2021 [80], the force of which was extended until 2026 [81]. With this change, there is currently no legal e-Privacy obstacle concerning the automated detection of CSAM in Europe.

Regarding the current landscape in the field of online child protection from sexual abuse, the Proposal for the Regulation on CSA [82] was published on 11 May 2022 by the European Commission. Since then, a series of Council compromise texts have emerged under successive presidencies [83], reflecting each presidency’s priorities and deeper legal and ethical debates at all levels of EU governance. The core debate surrounding the proposed CSA Regulation revolves around the urgent need of establishing mandatory obligations for online service providers to detect, report, and remove known and new CSAM, as well as grooming incidents, without jeopardizing the users’ fundamental rights to privacy and freedom of expression. In particular, the main concerns on the potential negative effects of such measures are related to users’ privacy, the integrity of end-to-end encryption and the principle of proportionality under EU law.

The Proposal consists of two main pillars: the first one introduces specific obligations for providers of hosting services, interpersonal communication services and platforms concerning the assessment of the risk of their services being misused for online child sexual abuse, detection, reporting, removing and blocking of known and new CSAM, as well as solicitation of children. The second one foresees the establishment of a decentralized EU body, the EU Centre on Child Sexual Abuse, which will maintain a centralized database of known CSAM indicators, new material, and grooming patterns to help companies comply with the provisions of the Regulation. Establishing a centralized repository for such data is expected to enhance the efficiency of service providers’ efforts. A noteworthy shift is that the responsibility for reporting detected abuse cases to law enforcement will now rest with the EU Centre, rather than individual service providers. This approach aims to ensure more consistent and timely information-sharing, particularly in cross-border situations [84].

It is worth emphasizing that the proposed CSA Regulation is technology-neutral and future-proof. This means that the detection obligations would apply regardless of the technology used in online exchanges. However, it is recommended that additional safeguards be applied, such as independent expert auditing of the database of indicators of the Centre and independent expert certification of tools for automated CSAM detection [61]. While companies may decide which technology to deploy, the designated competent national authority which is responsible for supervision and reviewing the risk assessment conducted by the provider may rely on independent experts to assess whether the technology a service provider intends to use complies with the legal requirements. The Proposal and the accompanying impact assessment report put forward only examples of hashing technologies and not standardized technical benchmarks.

Regarding the role that hashing technologies are envisaged to perform under the scope of the proposed Regulation—they will be primarily used for the detection of already known CSAM. Indeed, as also emphasized under the Impact Assessment Report accompanying the Proposal [61], hashing technologies have an estimated false positive rate of 0.000000002%.

In their Joint Opinion 04/2022, the European Data Protection Board (EDPB) and European Data Protection Supervisor (EDPS) [85], consider the clear standards that technologies for CSAM detection must adhere to (see proposed article 10 of CSAR.). Regarding the impact of the Proposal on end-to-end encryption (E2EE), the Joint Opinion underlines that European Data Protection Authorities have consistently emphasized, regardless of the technology used, their strong support for the widespread availability of robust encryption tools and their opposition to any form of backdoors, as encryption is essential to ensure the enjoyment of all human rights both offline and online.

Although the Proposal does not impose any obligation for providers to systematically intercept communications, the sheer possibility of a detection order being issued is expected to influence providers’ technical decisions to ensure timely compliance with the Regulation [85]. Consequently, the continued use of E2EE by some providers may be reconsidered or withdrawn. In particular, the EDPB and EDPS insist that technologies outlined in the Impact Assessment Report that accompanied the Proposal, such as client-side and server-side scanning, which are all methods aimed at bypassing end-to-end encryption’s privacy safeguards, entail security loopholes.

In relation to the practical application of the proposed Regulation, it is noted that a broad scope of the detection order may emerge due to the general conditions for its issuance in accordance with the Proposal’s provisions, such as its application to an entire service rather than to selected communications and the duration of the order which may extend up to 24 months for known CSAM, for instance. In view of the above, the EDPB and the EDPS also express their concern about the potential chilling effects of the exercise of freedom of expression [85].

With regard to the Interim Regulation, it is worth noting that the proposed CSAR Regulation aims at its abolition. Consequently, as of the date of the Proposal’s implementation, service providers will no longer be permitted to voluntarily detect online CSAM. Considering the regulation that will obligate only the recipients of detection orders to investigate such material, voluntary use of technologies by providers for the detection of CSAM and grooming incidents will only be allowed if explicitly provided for in the relevant national legislation, transposing the e-Privacy Directive, in accordance with Article 15 (1) of the aforementioned Directive. At the same time, the CSAR Proposal aims to establish a legal basis, within the meaning of the GDPR, for the processing of personal data for the purpose of CSAM detection (see Explanatory Memorandum of the CSAR Regulation, “Consistency with other Union Policies”.).

7. Limitations and Future Directions

This study presents several limitations that should be acknowledged. First the scope of the research was restricted to multimedia content in the form of images and videos, excluding other types, such as audio or text. Additionally, the study was conducted by researchers based in Europe, which means it predominantly reflects the legal frameworks and considerations within the European Union. As a result, the analysis does not extend to the laws of other regions or countries outside of the EU. In future work it would be valuable to broaden the scope to include audio and text-based multimedia, as well as to explore how different legal systems outside Europe, such as those in North America, Asia or Africa, approach similar issues. A cross-jurisdictional comparison could provide a more comprehensive understanding of the global implications and legal challenges posed by these technologies.

Further limitations exist due to the lack of standardized benchmarks, forcing developers to rely on ad hoc testing environments, which vary widely in dataset composition, transformation types (e.g., rotation, compression, blurring, etc.), and evaluation protocols. This inconsistency leads to fragmented results and hinders reproducibility across platforms. From a legal standpoint, while the European Commission provides examples of hashing technologies widely used for CSAM elimination, no specific technology is mandated, and technologies are not obliged to meet predefined benchmarks; rather, their suitability is evaluated in terms of their effectiveness, necessity, and proportionality in addressing the relevant criminal activities. Establishing standardized benchmarks would not only improve transparency and interoperability across perceptual hashing systems but also provide a foundation for ethical governance. It would enable regulators, researchers and service providers to align on what constitutes adequate detection performance, paving the way for more accountable and trustworthy content-moderation technologies, even though the EU legislation is designed to be future-proof.

Another significant challenge is the complex array of technical and legal risks inherent in using perceptual hashing in systems and databases, which demand careful scrutiny. Despite their design to tolerate minor content alterations, perceptual hashes remain vulnerable to attacks targeting robustness, because even small modifications can lead to false negatives or positives. Studies suggest that nearly all images can be altered to evade detection while retaining their visual characteristics, posing serious challenges for platforms tasked with identifying illicit content, such as CSAM. This not only undermines technical enforcement, but also risks non-compliance with legal obligations under frameworks, like the EU Digital Services Act, especially when detection failures compromise due diligence obligations.

These risks are further compounded by hash collisions, which allow different inputs to produce identical hash outputs. Such vulnerabilities enable poisoning attacks, where malicious actors manipulate collisions to bypass filters or generate false positives. These exploits threaten the integrity of hash-based moderation systems and complicate legal accountability, potentially exposing organizations to liability for failing to prevent the spread of harmful content. Equally concerning are inversion attacks which demonstrate that original images can be reconstructed from perceptual hashes using adversarial machine learning black box techniques or generative models. These methods jeopardize data subjects’ privacy and challenge the assumption that hashed data is inherently secure.

Finally, the storage and handling of perceptual hashes introduce additional privacy risks. If not properly secured, these hashes can leak sensitive information and their retention must comply with strict legal standards governing data, processing, and the right to be forgotten. Platforms must treat perceptual hashes with the same level of sensitivity as original content, to avoid misuse and ensure lawful operation.

Taken together, these risks highlight the urgent need for both technological refinement and legal evolution. Future systems must incorporate more resilient hashing techniques and regulatory frameworks must adapt to the probabilistic nature of these tools, balancing detection efficacy with robust privacy safeguards.

8. Conclusions

Hashes play a vital role in limiting the online spread of CSAM. Cryptographic hashes are used to identify exact duplicates of previously flagged content with high precision, while perceptual hashes enable the detection of visually similar or modified images. Together, these hashing techniques allow known CSAM files to be reliably blocked from re-upload, tracked across platforms, and authenticated during forensic investigations. This dual-hashing approach enhances the digital framework for CSAM prevention and law enforcement.

In our work, we highlighted the fact that there exists a critical yet underexplored challenge in this field. The perceptual hashing research community continues to highlight the need for unified evaluation frameworks, curated datasets, and consistent transformation protocols. The lack of standardized benchmarks in perceptual hashing presents a significant obstacle to technical evaluation. Unlike cryptographic hashing which benefits from well-defined performance metrics and security standards, perceptual hashing lacks universally accepted criteria for assessing robustness, accuracy, and collision resistance. This absence makes it difficult to compare algorithms objectively or to determine whether a given implementation meets the necessary thresholds for reliable content detection.

From a legal point of view, our findings reveal that perceptual hash functions do not qualify as a method of pseudonymization, and that hashes of personal data must be treated as personal data, too. Platforms and other DSPs must strike a delicate balance between ensuring user privacy and safeguarding against the dissemination of CSAM hashes.

On the one hand, there is the ethical imperative to protect individuals from exposure to abusive material and prevent the victimization of children. On the other hand, excessive surveillance of internet traffic may undermine the public’s right to privacy. Proportionality, transparency, and accountability are key points to CSAM systems containing hashes. Thus, detection systems must be proportional to the risk posed by CSAM. This means ensuring that detection efforts target illegal material, without sweeping up unrelated or lawful content, especially when employing broad monitoring techniques like AI-driven analysis.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.F.; Methodology, E.D.; Validation, P.F., E.D. and E.K.; Formal analysis, E.D.; Investigation, E.D. and E.K.; Resources, E.D. and E.K.; Data curation, E.D. and E.K.; Visualization, E.D.; Writing—original draft preparation, E.D. and E.K.; Writing—review and editing, P.F., E.D. and E.K.; Supervision, P.F.; Project administration, P.F.; Funding acquisition, P.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Internal Security Fund of the European Union under Specific Action “Towards a Coordinated and Cooperative Effort for the Prevention of Child Sexual Abuse at a European level” (Call: ISF/2022/SA/1.4.1; MIS: 6002910).

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the European Commission or the European Union Agency for CyberSecurity (ENISA).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Álvarez, D.P.; Orozco, A.L.S.; García-Miguel, J.P.; Villalba, L.J.G. Learning Strategies for Sensitive Content Detection. Electronics 2023, 12, 2496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellerman, H. Digital Computer System Principles Hardcover Herbert Hellerman; McGraw-Hill Companies: San Jose, CA, USA, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Marr, D.; Hildreth, E. Theory of edge detection. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 1980, 207, 187–217. [Google Scholar]

- Venkatesan, R.; Koon, S.-M.; Jakubowski, M.; Moulin, P. Robust Image Hashing. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Image Processing, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 10–13 September 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Swaminathan, A.; Mao, Y.; Wu, M. Perceptual Hash Functions for Image Authentication. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Image Processing (ICIP 2006), Atlanta, GA, USA, 8–11 October 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Monga, V.; Evans, B.L. Perceptual Image Hashing Via Feature Points: Performance Evaluation and Tradeoffs. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2006, 15, 3452–3465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuo-Zhong, W.; Xin-Peng, Z. Recent development of perceptual image hashing. J. Shanghai Univ. 2007, 11, 323–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farid, H. Digital Image Forensics. Sci. Am. 2008, 298, 66–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farid, H. Reining in online abuses. Technol. Innov. 2018, 19, 593–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farid, H. An Overview of Perceptual Hashing. J. Online Trust. Saf. 2021, 1, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Khan, M.Z.; Sharma, S.; Debnath, N.C. Perceptual Hashing Algorithms for Image Recognition. In Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Advanced Intelligent Systems and Informatics (AISI 2025), Port Said, Egypt, 19–21 January 2025; pp. 90–101. [Google Scholar]

- Ofcom. Overview of Perceptual Hashing Technology. 2022. Available online: https://www.ofcom.org.uk/siteassets/resources/documents/research-and-data/online-research/other/perceptual-hashing-technology.pdf?v=328806 (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- Klinger, E.; Starkweather, D. pHash: The Open Source Perceptual Hash Library. Available online: https://phash.org/ (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- Zauner, C. Implementation and Benchmarking of Perceptual Image Hash Functions. Bachelor’s Thesis, University of Applied Sciences Upper Austria, Hagenberg, Austria, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Buchner, J. ImageHash: Perceptual Image Hashing in Python. GitHub. 2013. Available online: https://github.com/JohannesBuchner/imagehash (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- McKeown, S.; Buchanan, W.J. Hamming Distributions of Popular Perceptual Hashing Techniques. In Proceedings of the DFRWS EU 2023, Bonn, Germany, 21–24 March 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Hamadouche, M.; Zebbiche, K.; Guerroumi, M.; Tebbi, H.; Zafoune, Y. The Comparative Study of Perceptual Hashing Algorithms: Application on Fingerprint Images. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Computer Science’s Complex Systems and their Applications (ICCSA 2021), Oum El-Bouaghi, Algeria, 25–26 May 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Du, L.; Ho, A.T.S.; Cong, R. Perceptual Hashing for Image Authentication: A Survey. Signal Process. Image Commun. 2020, 81, 115713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priyanka, S.; Shweta, J. Analysis of Perceptual Hashing Algorithms in Image Manipulation Detection. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2021, 185, 203–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkhowaiter, M.; Almubarak, K.; Zou, C. Evaluating Perceptual Hashing Algorithms in Detecting Image Manipulation Over Social Media Platforms. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE International Conference on Cyber Security and Resilience (CSR), Rhodes, Greece, 27–29 July 2022; pp. 149–156. [Google Scholar]

- Struppek, L.; Hintersdorf, D.; Neider, D.; Kersting, K. Learning to Break Deep Perceptual Hashing: The Use Case NeuralHash. In Proceedings of the 2022 ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency (FAccT 2022), Seoul, Republic of Korea, 21–24 June 2022; pp. 58–69. [Google Scholar]

- Roy, M.; Meitei, T.D.; Pal, S. Various Approaches to Perceptual Image Hashing Systems–A Survey. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Symposium on Advanced Computing and Communication (ISACC 2023), Silchar, India, 3–4 February 2023; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, B.; Gu, F.; Niu, X.; Huang, Y. Block Mean Value Based Image Perceptual Hashing. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Intelligent Information Hiding and Multimedia Signal Processing (IIH-MSP), Pasadena, CA, USA, 18–20 December 2006; pp. 167–172. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, J. A novel Block-DCT and PCA based image perceptual hashing algorithm. arXiv 2013, arXiv:1306.4079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.C.; Hatzinakos, D. Content Based Image Hashing Via Wavelet and Radon Transform. In Proceedings of the Advances in Multimedia Information Processing–PCM 2007, Hong Kong, China, 11–14 December 2007; pp. 755–764. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, Z.; Li, X.; Yuan, Y. Perceptual Hashing for Color Images Using Invariant Moments. Appl. Math. Inf. Sci. 2012, 6, 643S–650S. [Google Scholar]

- De Roover, C.; De Vleeschouwer, C.; Lefebvre, F.; Macq, B. Robust image hashing based on radial variance of pixels. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Image Processing (ICIP), Genova, Italy, 14 September 2005; pp. 77–80. [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez, R.A.P.; Miyatake, M.N.; Kurkoski, B.M. Robust image hashing using image normalization and SVD decomposition. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Midwest Symposium on Circuits and Systems (MWSCAS), Seoul, Republic of Korea, 7–10 August 2011; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Koval, O.J.; Voloshynovskiy, S.; Beekhof, F.; Pun, T. Security analysis of robust perceptual hashing. Proc. SPIE 2008, 6819, 681906. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H.; Zhou, H.; Zhang, J.; Chen, D.; Zhang, W.; Chen, K.; Hua, G.; Yu, N. Perceptual Hashing of Deep Convolutional Neural Networks for Model Copy Detection. ACM Trans. Multimed. Comput. Commun. Appl. 2023, 19, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Li, J. CNN Based Hashing for Image Retrieval. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1509.01354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalins, J.; Wilson, C.; Boudry, D. PDQ & TMK + PDQF–A Test Drive of Facebook’s Perceptual Hashing Algorithms. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1912.07745. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez, P.; Couairon, G.; Jegou, H.; Douze, M.; Furon, T. The Stable Signature: Rooting Watermarks in Latent Diffusion Models. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Paris, France, 2–3 October 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Wary, A.; Neelima, A. A Review on Robust Video Copy Detection. Int. J. Multimed. Inf. Retr. 2019, 8, 61–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- META AI, TMK+PDQF Video Hashing Framework. GitHub. 2021. Available online: https://github.com/facebook/ThreatExchange/tree/main/hashing/tmk (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- Ásmundsson, F.H.; Lejsek, H.; Daðason, K.; Jónsson, B.Þ.; Amsaleg, L. Videntifier Forensic: Robust and Efficient Detection of Illegal Multimedia. In Proceedings of the First ACM Workshop on Multimedia in Forensics, Beijing, China, 23 October 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H.; Hu, C.; Lee, F.; Lin, C.; Yao, W.; Chen, L.; Chen, Q. A Supervised Video Hashing Method Based on a Deep 3D Convolutional Neural Network for Large-Scale Video Retrieval. Sensors 2021, 21, 3094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gayathri, M.; Livitha, M.; Surya, N.; Ramya, M.; Surya, N. A Survey on Secured Video Transmission by Synchronisation and Hashing Technique. Int. J. Adv. Inf. Commun. Technol. 2019, 6. Available online: https://www.ijaict.com/journals/ijaict/ijaict_pdf/2019_volume06/2019_v6i11/ijaict%202017110301.pdf (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- Morales, F.; Sharma, S.; Doan, C.; Levine, B. PHVSpec: A Benchmark-based Analysis of Perceptual Hash Systems for Videos. Tech. Coalit. 2024. Available online: https://paragonn-cdn.nyc3.cdn.digitaloceanspaces.com/technologycoalition.org/uploads/Tech-Coalition-Video-Hash-Benchmark-Paper.pdf (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- Hamming, R.W. Error detecting and error correcting codes. Bell Syst. Tech. J. 1950, 29, 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dokmanic, I.; Parhizkar, R.; Ranieri, J.; Vetterli, M. Euclidean Distance Matrices: Essential Theory, Algorithms and Applications. IEEE Signal Process. Mag. 2015, 32, 12–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connor, R. A Tale of Four Metrics. In Proceedings of the Similarity Search and Applications (SISAP 2016), Tokyo, Japan, 24–26 October 2016; pp. 210–217. [Google Scholar]

- McKeown, S. Beyond Hamming Distance: Exploring spatial encoding in perceptual hashes. Forensic Sci. Int. Digit. Investig. 2025, 52, 301878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menezes, A.J.; van Oorschot, P.C.; Vanstone, S.A. Handbook of Applied Cryptography; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Rivest, R. The MD5 Message-Digest Algorithm. RFC Editor. 1992. Available online: http://www.ietf.org/rfc/rfc1321.txt (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- Eastlake, D.; Jones, P. US Secure Hash Algorithm 1 (SHA1). IETF RFC3174. 2001. Available online: https://www.rfc-editor.org/rfc/rfc3174.html (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- FIPS 180-1; Secure Hash Standard. National Institute of Standards and Technology: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 1995.

- Klima, V. Finding MD5 Collisions–a Toy For a Notebook. Cryptol. Eprint Arch. 2005. Available online: https://eprint.iacr.org/2005/075.pdf (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- Wang, X.; Yin, Y.; Yu, H. Finding Collisions in the Full SHA-1. In Proceedings of the 25th Annual International Cryptology Conference, Santa Barbara, CA, USA, 14–18 August 2005; pp. 17–36. [Google Scholar]

- Black, J.; Cochran, M.; Highland, T. A Study of the MD5 Attacks: Insights and Improvements. In Proceedings of the 13th International Workshop, Fast Software Encryption, Graz, Austria, 15–17 March 2006; pp. 262–277. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute of Standards and Technology. NIST Transitioning Away from SHA-1 for All Applications. 2022. Available online: https://www.nist.gov/news-events/news/2022/12/nist-transitioning-away-sha-1-all-applications (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- FIPS PUB 180-4; Secure Hash Standard (SHS). National Institute of Standards and Technology: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2015.

- FIPS PUB 202; SHA-3 Standard: Permutation-Based Hash and Extendable-Output Functions. National Institute of Standards and Technology: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2015.

- Vidanage, A.; Christen, P.; Ranbaduge, T.; Schnell, R. A Vulnerability Assessment Framework for Privacy-preserving Record Linkage. ACM Trans. Priv. Secur. 2023, 26, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GDPR, GDPR, REGULATION (EU) 2016/679 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 April 2016 on the Protection of Natural Persons with Regard to the Processing of Personal Data and on the Free Movement of Such Data. 2016. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2016/679/oj/eng (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- EDPB. Guidelines 01/2025 on Pseudonymization. 2025. Available online: https://www.edpb.europa.eu/our-work-tools/documents/public-consultations/2025/guidelines-012025-pseudonymisation_en (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- ENISA. Data Pseudonymisation: Advanced Techniques & Use Cases. 2021. Available online: https://www.enisa.europa.eu/publications/data-pseudonymisation-advanced-techniques-and-use-cases (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- Danaher, B.; Hersh, J.; Smith, M.D.; Telang, R. Fighting Crime Online. Assoc. Comput. Mach. 2025, 68, 34–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ENISA. Recommendations on Shaping Technology According to GDPR Provisions: An Overview on Data Pseudonymization. 2018. Available online: https://www.enisa.europa.eu/publications/recommendations-on-shaping-technology-according-to-gdpr-provisions (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- Microsoft Research; Farid, H. PhotoDNA. 2009. Available online: https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/photodna (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- Impact Assessment Report. Commission Staff Working Document Impact Assessment Report Accompanying the document Proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council laying down rules to prevent and combat child sexual abuse. 2022. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=celex:52022SC0209 (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- EPRS. Complementary Impact Assessment Report. 2023. Available online: https://www.ecorys.com/app/uploads/files/2023-05/EPRS_STU(2023)740248_EN.pdf (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- Athalye, A. Inverting PhotoDNA: Reconstructing Images from Hashes. Personal blog and GitHub. 2021. Available online: https://anishathalye.com/inverting-photodna (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- Madden, J.; Bhavsar, M.; Dorje, L.; Li, X. Robustness of Practical Perceptual Hashing Algorithms to Hash-Evasion and Hash-Inversion Attacks. NeurIPS 2024 Workshop on New Frontiers in Adversarial Machine Learning. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2406.00918. [Google Scholar]

- Prokos, J.; Fendley, N.; Green, M.; Schuster, R.; Tromer, E.; Jois, T.; Cao, Y. Squint Hard Enough: Attacking Perceptual Hashing with Adversarial Machine Learning. In Proceedings of the 32nd USENIX Security Symposium (USENIX Security 23), Anaheim, CA, USA, 9–11 August 2023; pp. 211–228. [Google Scholar]

- Hawkes, S.; Weinert, C.; Almeida, T.; Mehrnezhad, M. Perceptual Hash Inversion Attacks on Image-Based Sexual Abuse Removal Tools. IEEE Secur. Priv. 2025, 23, 64–73. [Google Scholar]

- INTERPOL. INTERPOL’s Child Sexual Exploitation Database. INTERPOL and ECPAT. 2018. Available online: https://www.interpol.int/en/content/download/9363/file/Summary%20-%20Towards%20a%20Global%20Indicator%20on%20Unidentified%20Victims%20in%20Child%20Sexual%20Exploitation%20Material.%20February%202018.pdf (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- Kokolaki, E.; Daskalaki, E.; Psaroudaki, K.; Christodoulaki, M.; Fragopoulou, P. Investigating the dynamics of illegal online activity: The power of reporting, dark web, and related legislation. Comput. Law Secur. Rev. 2020, 38, 105440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Google/YouTube. CSAI Match: Video Fingerprinting System for Known CSAM Detection. 2022. Available online: https://protectingchildren.google/tools-for-partners (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- Gupta, D. Apple Renounces NeuralHash, Its Controversial Anti-CSAM System. Τechunwrapped. 2022. Available online: https://techunwrapped.com/apple-renounces-neuralhash-its-controversial-anti-csam-system (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- Internet Watch Foundation. IWF Hash List: A Database of Hashes of Known Child Sexual Abuse Material. 2022. Available online: https://www.iwf.org.uk/our-technology/our-services/image-hash-list (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- National Center for Missing & Exploited Children. NCMEC CSAM Hash Database and CyberTipline System. 2023. Available online: https://www.missingkids.org/gethelpnow/cybertipline (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- Thorn. Introducing Safer Match, API-Based CSAM Detection. Thorn. 2023. Available online: https://www.thorn.org/blog/safer-match (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- Canadian Centre for Child Protection. Project Arachnid: Reducing the Online Availability of Child Sexual Abuse Material. 2017. Available online: https://www.projectarachnid.ca (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- Web-IQ, B.V. Hash Check Server (HCS): Scalable CSAM Hash Matching Service. 2025. Available online: https://www.web-iq.com (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- World Childhood Foundation. Advancing Technology to Stop Child Sexual Abuse, World Childhood Foundation. 2022. Available online: https://childhood.org/news/advancing-technology-to-stop-child-sexual-abuse/ (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- Jain, S.; Crețu, A.-M.; de Montjoye, Y.-A. Adversarial Detection Avoidance Attacks: Evaluating the robustness of perceptual hashing-based client-side scanning. In Proceedings of the 31st USENIX Security Symposium, Boston, MA, USA, 10–12 August 2022. [Google Scholar]

- INHOPE. e-Privacy Derogation Passes & New Regulations. 2021. Available online: https://inhope.org/EN/articles/e-privacy-derogation-passes-new-regulations (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- e-Privacy. Directive 2002/58/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 12 July 2002 Concerning the Processing of Personal Data and the Protection of Privacy in the Electronic Communications Sector (Directive on Privacy and Electronic Communications). 2002. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/dir/2002/58/oj/eng (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- Interim Regulation. Regulation (EU) 2021/1232 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 14 July 2021 on a Temporary Derogation from Certain Provisions of Directive 2002/58/Ec as Regards the Use of Technologies by Providers of Number-Independent Interpersonal Communications. 2021. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=uriserv:OJ.L_.2021.274.01.0041.01.ENG (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- Interim Regulation Amendment. Regulation (EU) 2024/1307 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 29 April 2024 Amending Regulation (EU) 2021/1232 on a Temporary Derogation from Certain Provisions of Directive 2002/58/Ec as Regards the Use of Technologies by Providers of Number. 2024. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A32024R1307 (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- CSAR. Proposal for a Regulation of the European and of the Council Laying Down Rules to Prevent and Combat Child Sexual Abuse. 2022. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=COM%3A2022%3A209%3AFIN&qid=1652451192472 (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- EDRi. CSA Regulation Document Pool. 2023. Available online: https://edri.org/our-work/csa-regulation-document-pool/?utm_source=chatgpt.com#council (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- Rojszczak, M. Preventing the dissemination of child sexual abuse material (CSAM) with surveillance technologies: The case of EU Regulation 2021/1232. Comput. Law Secur. Rev. 2025, 56, 106097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EDPS; EDPB. Joint Opinion 04/2022 on the Proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council Laying Down Rules to Prevent and Combat Child Sexual Abuse. Available online: https://www.edpb.europa.eu/system/files/2022-07/edpb_edps_jointopinion_202204_csam_en_0.pdf (accessed on 28 October 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).