Abstract

Weed management has become a critical agricultural practice, as weeds compete with crops for nutrients, host pests and diseases, and cause major economic losses. The invasive weed Ambrosia artemisiifolia (common ragweed) is particularly problematic in Hungary, endangering crop productivity and public health through its fast proliferation and allergenic pollen. This review examines the current challenges and impacts of A. artemisiifolia while exploring sustainable approaches to its management through precision agriculture. Recent advancements in unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) equipped with advanced imaging systems, remote sensing, and artificial intelligence, particularly deep learning models such as convolutional neural networks (CNNs) and Support Vector Machines (SVMs), enable accurate detection, mapping, and classification of weed infestations. These technologies facilitate site-specific weed management (SSWM) by optimizing herbicide application, reducing chemical inputs, and minimizing environmental impacts. The results of recent studies demonstrate the high potential of UAV-based monitoring for real-time, data-driven weed management. The review concludes that integrating UAV and AI technologies into weed management offers a sustainable, cost-effective, mitigate the socioeconomic impacts and environmentally responsible solution, emphasizing the need for collaboration between agricultural researchers and technology developers to enhance precision agriculture practices in Hungary.

1. Introduction

The Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) reported that the global population is expected to increase to nine billion people by 2050, resulting in a double increase in food consumption; meanwhile, agricultural resources will become more limited, degraded, and increasingly vulnerable to climate change [1]. It is crucial to observe, measure, and study the physical aspects and phenomena within complex multifunctional agricultural ecosystems to have a better understanding of these challenges [2]. To achieve this, the use of unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), image satellites, and autonomous field robots in agriculture has significantly developed [3,4]

In recent years, remote sensing has undergone rapid development, particularly in data gathering and computer vision technologies, which have enabled a wide range of precision agricultural applications. These activities are included: abiotic stress evaluation, growth monitoring, crop yield prediction, weed detection and mapping, and disease and pest identification [2]. The objective of precision agriculture (PA) is to improve resource efficiency, productivity, quality, and profitability of agricultural production by using the data that are collected, processed, and integrated with additional information to make decisions based on temporal and spatial variability [5,6].

Because of this, farmers use advanced technologies, including unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) for weed detection and management to enhance crop productivity [7]. Weed management has become crucial to maintain the quality of crops, particularly vegetable crops and cereals, reducing yield loss and preventing economic loss [8]. Because weeds compete with the main crop for essential resources, including nutrients, water, light, and CO2, space, which causes a significant reduction in crop outcome.

Additionally, weeds serve as reservoirs for a wide range of pests, including insects, bacteria, viruses, and fungi, which can subsequently infest neighboring crops [9,10]. Several economically important insect pests, such as whiteflies and aphids, use weeds as alternative hosts before spreading to vegetable and field crops [11,12]. Similarly, weeds can harbor plant pathogens, including viruses such as Tobacco rattle virus, thereby increasing disease pressure and complicating integrated pest management strategies [13]

However, in addition to civilization and the economy, the introduction of alien species has a major effect on biological variety and the preservation of nature. Invasive alien species are now acknowledged as one of the primary threats to biodiversity, along with habitat loss and fragmentation. The risks and deficiencies have been highlighted by European nations. Projects have been started, and the categorization and list of invasive species have been accurately identified in a number of European nations, such as Hungary and the United Kingdom. Measures to stop the invasion of Common Ragweed (Ambrosia artemisiifolia), which is becoming a greater hazard to human health, are given top attention in Hungary. Approximately 30% of the Hungarian population experiences allergies, with 65% of these persons having sensitivity to pollen, and at least 60% of this pollen sensitivity is caused by common ragweed [14]. Additionally, the world’s landscapes and ecosystems are changing due to ongoing climate change and biological invasions [15,16]. Invasive species are directly impacted by changing rainfall and temperature patterns as they are exposed to changing physiological constraints. Due to their adaptability to changing climatic conditions, many of these species are better able to expand to new areas within their non-native range [17], so by increased extreme rainfall and drier summer conditions have also impacted the spread of A. artemisiifolia.

Direct weed identification in croplands is difficult due to the presence of over 200 harmful plant species. The effects of weeds on various crops have been demonstrated in several studies [18]. For instance, in Californian lettuce fields [19], it was observed that season-long weed competition resulted in a 50% reduction in lettuce production. This study examined different weed management methods on wheat yield, finding that uncontrolled weed growth led to yield reductions ranging from 57.6% to 73.2%. Effective strategies such as post-emergence herbicides and hand weeding were highlighted as crucial for mitigating these losses [20].

The aims of this review paper are to assess the effects of invasive weed species, specifically Ambrosia artemisiifolia, on agricultural output and public health in Hungary and investigate contemporary precision agriculture technology, particularly unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) which is equipped with machine learning-driven image processing, for site-specific weed management. These technologies provide precise weed detection, classification, enabling precision herbicide application, thereby minimizing environmental damage and enhancing resource efficiency.

Hungary is presented in this review as a representative case study for regions in Central and Eastern Europe facing severe Ambrosia artemisiifolia infestation, where agricultural impacts, public health concerns, and the need for advanced monitoring technologies converge.

2. Literature Search Approach

To support the topics addressed in this study, appropriate articles were identified by searches in Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar. The search concentrated on research related to Ambrosia artemisiifolia, precision agriculture, machine learning and deep learning, UAV-based remote sensing, and site-specific weed management (SSWM).

2.1. Search Strategy and Keywords

The search used combinations of the following keywords: “Ambrosia artemisiifolia”, “common ragweed”, “UAV”, “unmanned aerial vehicle”, “drone”, “remote sensing”, “weed detection”, “hyperspectral”, “multispectral”, “RGB imaging”, “sensor fusion”, “multi-modal data”, “precision agriculture”, “machine learning”, “deep learning”, “site-specific weed management”.

2.2. Timeframe and Scope

The literature review is primarily concentrated on papers published from 2000 to 2026, highlighting advancements in contemporary remote sensing, machine learning, and unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) technology for weed detection and management. Earlier foundational publications concerning the history, biology, and ecological effects of Ambrosia artemisiifolia were incorporated to furnish critical background and context. These works encompass previous decades and substantiate the initial sections of the evaluation.

2.3. Selection Approach

While this is not a systematic review, preference was given to: peer-reviewed studies, research involving UAV-based sensors (RGB, multispectral, hyperspectral). Studies addressing weed detection, mapping, classification, or management work focusing on A. artemisiifolia or similar broadleaf weeds. This literature search strategy ensured broad coverage of key technological developments while maintaining a clear focus on sustainable UAV-based site-specific weed management for Ambrosia artemisiifolia.

3. Common Ragweed or Annual Ragweed (Ambrosia artemisiifolia)

Common ragweed, or annual ragweed (Ambrosia artemisiifolia), is an invasive species belonging to the Asteraceae family. Native to North America, but now widespread across Europe, where it causes significant agricultural and public-health impacts [21,22,23,24,25]. Two independent introductions from eastern and western North America have contributed to its establishment in Europe [26]. (Figure 1) shows field photographs of Ambrosia artemisiifolia taken at the experimental field of the Hungarian University of Agriculture and Life Sciences, illustrating its characteristic growth form under local field conditions.

Figure 1.

Morphological appearance of Ambrosia artemisiifolia observed in experimental fields at the Agronomy Institute field, Hungarian University of Agriculture and Life Sciences (MATE), Gödöllő 2100, Hungary: (a) individual plants grown in pots; (b) dense stand of A. artemisiifolia in the field—photographs collected by Sherwan Yassin Hammad, July 2024.

3.1. History of Common Ragweed in Europe, Specifically in Hungary

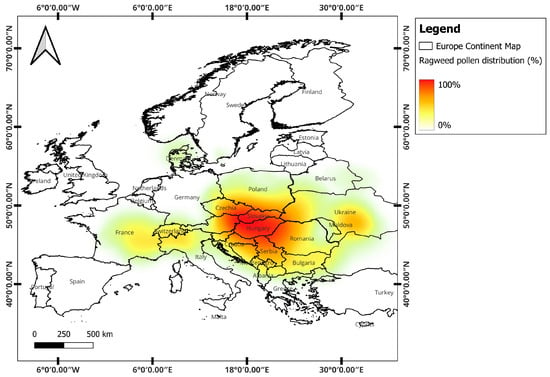

Common ragweed began spreading across Europe after World War I, partly through contaminated clover seed shipments [27,28]. It became increasingly common in Central and Eastern Europe, with major entry points at ports such as Rijeka, Marseille, Genoa, and Trieste [28,29]. Based on data obtained from the European Aeroallergen Network (EAN) and the European Pollen Information (EPI), the pollen distribution map was created, indicating elevated Ambrosia artemisiifolia pollen concentrations across Eastern and Central Europe during the period 1–10 September 2025 (Figure 2) [30,31].

Figure 2.

Distribution of Ambrosia artemisiifolia pollen in Europe during 1–10 September 2025, based on data from the European Pollen Information (EPI). The map was created by the authors using QGIS.

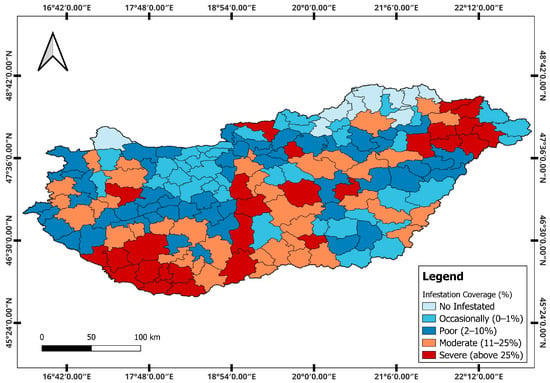

In Hungary, ragweed was first recorded in Budapest in 1888. It expanded rapidly through the 20th century and became one of the country’s most dominant arable weeds, rising from 21st place in the 1950s to 4th place by the 1980s [27]. By 2003, it had infested 5.4 million hectares, with 700,000 hectares strongly infested [32]. According to the data obtained from the Central Office of Soil and Plant Protection of Hungary, counties such as Somogy, Baranya, and Szabolcs-Szatmár-Bereg remained the most affected in 2005 (Figure 3). Along the Austrian–Hungarian border, ragweed abundance was found to depend more on land-use factors (crop cover, previous crop, farming type) than on climatic or soil variables [33].

Figure 3.

Spatial distribution of Ambrosia artemisiifolia infestation across Hungary in 2005, based on data from the Central Office of Soil and Plant Protection of Hungary and mapped by the authors using QGIS.

Hungary has implemented a comprehensive framework for controlling Ambrosia artemisiifolia that combines legal regulation, systematic monitoring, and integrated weed management approaches [34,35,36,37,38]. Since 2005, national legislation has required landowners to prevent ragweed spread, supported by centralized monitoring systems and spatial infestation maps developed by national geodesy and remote sensing institutions [38]. These national efforts align with broader European initiatives, such as the EU COST Action “SMARTER,” which promotes sustainable and biological control strategies for ragweed across Europe [39]. Biological control programs, including the use of Ophraella communa, and citizen science-based monitoring platforms, further highlight that ragweed management is a shared European challenge rather than a country-specific issue [34,40,41]. Together, these national and EU-level actions position Hungary as a representative regional case within wider European strategies, where UAV-based remote sensing and site-specific weed management technologies offer scalable and transferable solutions for invasive weed control [27,36,42].

3.2. Botanical and Biological Characteristics Relevant to Weed Detection

Ragweed is an erect annual plant, typically up to 250 cm tall, with a hairy, branched or unbranched stem and deeply lobed leaves [41]. Male flowers occur in spike-like clusters at the top of the plant, producing large amounts of pollen, while female flowers are located in the leaf axils. Ref. [43] demonstrates that Ambrosia artemisiifolia exhibits strong biological adaptability and herbicide resistance, particularly across early growth stages, highlighting its vigorous growth and survival capacity. Such biological traits contribute to persistent infestations and emphasize the importance of early-stage identification in weed detection systems. Seed predation influences the seed bank and emergence patterns of Ambrosia artemisiifolia, with implications for weed detection [43]. Ambrosia artemisiifolia includes prolonged emergence, rapid vegetative growth, high seed longevity, and strong sensitivity to environmental conditions. These traits drive spatial and temporal variability in infestations, which is critical for effective image-based and sensor-driven weed detection [44,45].

3.3. Agricultural and Health Impacts

Ragweed is the most important arable weed in Hungary [46] and also invades natural ecosystems, reducing species diversity and forage value [47]. Its allelopathic effects can suppress crop germination and growth [48,49]. From a public-health perspective, ragweed is among the most allergenic plants in Europe and North America, ranking 9th among major broadleaf weeds and 7th in soybean fields according to the Weed Science Society of America (WSSA) [50]. Its pollen is a major cause of asthma and allergic rhinitis, contributing substantially to healthcare costs and lost productivity across Europe [46].

The biological, ecological, and impact-related features of common ragweed determine its spatial distribution, spectral appearance, and detectability in UAV imagery, thereby influencing detection accuracy and site-specific weed management strategies discussed in the following sections.

4. Precision Agriculture (PA) and Site-Specific Weed Management (SSWM)

The weed control techniques are classified into three categories: mechanical, physical, and biological. Physical weed control techniques included mulching, solarization, flaming, and steaming [51]. Because chemical herbicides are easy to use, spraying weeds using tractors or Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) has become a common way to manage weeds [52]. Nevertheless, despite their direct toxicity to the plants they are intended to kill, the use of chemical herbicides has resulted in significant environmental damage [53]. Pesticide residues from overuse of herbicides have also been found in agricultural products, affecting their quality and yield as well as the efficiency of agricultural production [54].

The first stage in using an automated weed management system is accurately identifying and detecting weeds, which is good for the environment and the economy [55]. Diverse weed management techniques must be used in SSWM, and they must be modified based on the location, density, and population of the weeds [56]. The vision-based image processing system, which functions as the machine’s brain, finds the real-time application of herbicide through the use of variable rate technology (VRT) [57].

Currently, there are two different kinds of VRT-based applications: (1) sensor-based and (2) map-based. One popular method is map-based, where a region’s map is created using georeferenced soil or plant samples. This procedure is costly and time-consuming as it requires manually collecting soil samples for further investigation [58]. In contrast, sensor-based approaches enable real-time data acquisition and processing, allowing immediate weed detection and treatment. When combined with machine learning (ML) or deep learning (DL) methodologies deployed on ground-based or aerial platforms, sensor-based VRT systems support real-time decision-making and precise herbicide application [57].

Growth monitoring is a critical measure for estimating agricultural production and is vital for decision-making [59]. Traditional methods, such as expert visual evaluations or chemical laboratory analyses, are used to evaluate the crop’s growth and nutritional condition. These approaches are time-consuming and impractical for monitoring large areas of a site. In contrast, machine learning based image processing technology has emerged as an effective solution, providing real-time data on crop health and nutrient status, and can be used for continual monitoring throughout the crop life cycle [60].

The rapid development of automated precision agriculture has been driven by advances in artificial intelligence (AI), machine learning (ML), and deep learning (DL). These technologies play a central role in transforming remotely sensed data into actionable information for site-specific weed management (SSWM). Among AI approaches, deep learning has emerged as a particularly powerful tool for weed identification and discrimination due to its ability to automatically extract complex features from image data [57].

4.1. Machine Learning Approaches for Weed Detection and Mapping

Conventional machine learning (ML) techniques, such as Support Vector Machines (SVM), Random Forests, and k-nearest neighbors (KNN), have been extensively utilized for weed-crop categorization employing characteristics derived from RGB, multispectral, and hyperspectral imaging. Commonly used features include spectral reflectance values, vegetation indices, texture descriptors, and shape-based metrics. Machine learning classifiers are especially proficient when training datasets are limited and computational efficiency is required. The results of these models are generally utilized to create weed distribution maps, which serve as the basis for site-specific weed management strategies.

Recent studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of ML-driven approaches for large-scale and real-time weed detection. For example, hybrid architectures integrating convolutional neural networks with vision transformers, combined with adaptive multispectral feature fusion techniques, have achieved detection accuracies of up to 98% in real-time weed monitoring conditions [61]. Similarly, Random Forest models applied to high-resolution multispectral imagery have shown promising performance in distinguishing crops from weeds, achieving an overall accuracy of approximately 76%, although further refinement is required to reduce false-negative detections [62].

In addition to pixel-based classification, image-processing techniques such as contour detection and Histogram of Oriented Gradients (HOGs) feature extraction have been successfully combined with classifiers such as SVM and KNN for accurate weed identification and management [63]. More recently, deep-learning-based object detection models, including YOLOv8 and YOLOv9, have demonstrated strong performance, with mean average precision (mAP50) values ranging from 80.8% to 98% across different weed and crop species [64].

UAV-based imaging systems further enhance ML-driven weed mapping by providing ultra-high spatial resolution data suitable for early-stage weed detection. Approaches such as object-based image analysis (OBIA) and supervised machine learning applied to UAV imagery have shown promising results in delineating weed patches and supporting site-specific interventions [65]. These techniques contribute to sustainable farming practices by reducing manual labor requirements and minimizing unnecessary herbicide application [63,66,67].

Despite these advances, several challenges remain, including spectral similarity between crops and weeds, canopy occlusion, and variable illumination conditions, which can negatively affect classification accuracy. Addressing these limitations requires continued research and methodological refinement, as well as integration with advanced sensing technologies and deep learning approaches [68,69].

4.2. Deep Learning for Weed Crop Discrimination in Complex Field Environments

Deep learning (DL) approaches represent a significant advancement beyond classical machine learning methods for weed crop discrimination, particularly in complex field environments. Unlike traditional ML techniques that rely on handcrafted features, DL models automatically learn hierarchical and task-specific representations directly from image data, enabling improved robustness under variable illumination, canopy overlap, and strong visual similarity between weeds and crops [70,71,72,73].

Convolutional neural networks (CNNs), including architectures such as VGG, ResNet, YOLO-based object detectors, and semantic segmentation models such as U-Net, have demonstrated high accuracy in detecting and localizing weeds in real agricultural settings. YOLO-based models, in particular, have shown strong performance in cluttered field conditions, with reported detection accuracies of approximately 83%, while CNN-based classification and segmentation approaches have achieved accuracies of up to 98% in weed crop discrimination tasks [71,72].

High-resolution imagery acquired from UAV platforms is commonly used to train deep learning models, with preprocessing strategies such as data augmentation and normalization applied to improve generalization across varying field conditions. These techniques are especially important for early growth stages, where weeds are small and difficult to distinguish from crops [74,75].

Deep learning models are increasingly integrated into operational precision agriculture systems, including UAV-based monitoring workflows and smart spraying platforms. This integration enables near real-time weed detection and supports targeted herbicide application, contributing to more efficient and environmentally sustainable site-specific weed management [73,76,77].

Despite their advantages, DL approaches face challenges related to large labeled data requirements and computational complexity. To mitigate these limitations, transfer learning, data augmentation, and lightweight network architectures (e.g., ShuffleNetv2) have been proposed to reduce training effort and improve deployment feasibility [74,75,78]. Further improvements in model generalization and scalability remain key research priorities [79,80].

4.3. From Weed Detection to Precision Herbicide Application

The integration of AI-based weed detection outputs into precision herbicide application systems represents a critical step toward sustainable site-specific weed management. Weed distribution maps generated using machine learning or deep learning models can be translated into prescription maps that guide variable-rate or spot-specific spraying, enabling herbicides to be applied only where weeds are [81,82,83]. This approach significantly reduces chemical inputs, minimizes environmental impacts, and lowers production costs compared with conventional broadcast spraying methods [83,84].

Recent advances in deep learning and computer vision have substantially improved the feasibility of real-time precision herbicide application. Object detection models such as YOLO, including versions YOLOv3 and YOLOv4, have been widely adopted for real-time weed detection using UAV- and camera-based imaging systems. These models are trained on annotated datasets of crops and weeds and can be integrated with drone-mounted cameras or smart spraying platforms to enable targeted herbicide application directly in the field [81,82]. Hybrid frameworks that combine YOLO-based object detection with U-Net semantic segmentation have further improved boundary delineation, enhancing the spatial precision of herbicide delivery [85].

Other deep learning architectures have also demonstrated strong potential for operational weed control. Approaches integrating DenseNet for high-accuracy classification with YOLO for spatial localization have achieved high validation accuracy and mean Average Precision (mAP), supporting efficient and scalable weed management strategies [82]. In addition, ensemble deep learning methods that combine multiple architectures, such as ResNet18, InceptionV3, and DenseNet201, have shown improved robustness and reduced false-positive and false-negative rates in weed detection, further enhancing the reliability of precision spraying systems [86].

In practical applications, high-resolution UAV imagery combined with advanced detection models, such as YOLOv8, has enabled selective herbicide application with minimal human intervention and improved real-time performance [87]. The integration of multispectral remote sensing data with UAV-based platforms has also facilitated site-specific herbicide application, particularly in large agricultural fields. For instance, the use of remotely piloted aerial application systems (RPAAS) in rice fields resulted in a 45% reduction in herbicide usage compared to conventional broadcast spraying methods, demonstrating the environmental and economic benefits of precision application strategies [83].

For invasive species such as Ambrosia artemisiifolia, early and targeted intervention is particularly important to prevent seed production and pollen release. UAV-derived weed maps and AI-driven detection systems support timely decision-making and enable precise treatment at early growth stages, thereby improving control efficiency and reducing long-term infestation risks. Overall, AI-enabled precision herbicide application contributes directly to sustainable farming practices by optimizing resource use, reducing environmental hazards, and improving weed management outcomes [82,84,88].

4.4. Role of AI in Supporting Sustainable Site-Specific Weed Management

Artificial intelligence plays a central role in enabling sustainable site-specific weed management (SSWM) by transforming remotely sensed data into precise, actionable interventions. By supporting accurate weed detection, spatial mapping, and targeted treatment, AI-driven approaches contribute directly to reduced herbicide inputs, lower off-target effects, and improved treatment efficiency, thereby promoting environmentally responsible weed control practices [89,90,91].

AI-based systems integrate machine learning and deep learning algorithms with image processing, computer vision, and multispectral data to accurately identify and classify weed species. This capability enables site-specific and species-specific interventions, which are increasingly important under conditions of climate change that promote faster and prolonged weed growth cycles [92,93,94]. In particular, convolutional neural networks (CNNs) have enhanced weed detection performance through automated feature learning, improving robustness to spatio-temporal variability and heterogeneous field conditions [95].

Beyond detection, AI facilitates real-time decision-making through integration with UAV platforms, smart sprayers, and robotic systems. AI-enabled spot-spraying technologies can apply herbicides directly to detected weeds with minimal overspray, substantially reducing chemical usage while preserving crop health [96]. Most notably, UAVs provide very high spatial resolution, enabling the identification and mapping of small and early-stage weed patches that are often undetectable in satellite imagery due to coarse resolution [97].

Despite these advances, the effectiveness of AI-driven SSWM depends strongly on data quality, sensor selection, and the reliability of real-time sensing and control systems. Challenges remain related to sensor interoperability, system scalability, and the deployment of robust real-time solutions under field conditions [90,98]. In this context, high-resolution UAV imagery supports more accurate early-stage weed detection and timely site-specific weed management [99]. Continued research, technological integration, and collaboration among agronomists, engineers, and policymakers are therefore essential to fully realize the potential of AI in sustainable weed management.

5. Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) in Weed Management

Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) play an increasingly important role in modern agriculture, particularly as platforms for high-resolution data acquisition that support weed detection and site-specific management. While UAV-based spraying technologies exist and offer advantages such as improved targeting and reduced labor demand [100]. This review focuses primarily on UAV-based imaging, sensor technologies, and analytical methods for weed detection and mapping. The section highlights the advantages of UAV-based remote sensing over conventional platforms, discusses key technical constraints in image acquisition and processing, and outlines emerging solutions relevant to site-specific weed management.

5.1. Advantages of UAV-Based Remote Sensing Compared to Other Platforms

UAV-based remote sensing offers several advantages over satellite and manned airborne platforms for site-specific weed management. Most notably, UAVs provide very high spatial resolution, enabling the identification and mapping of small and early-stage weed patches that are often undetectable in satellite imagery due to coarse resolution and cloud interference [101,102,103,104]. This capability is particularly important for early-season detection, which is critical for timely and effective weed management interventions [103,105]. UAVs offer higher spatial resolution, on-demand data acquisition, and reduced sensitivity to cloud cover compared with satellite platforms, making them particularly suitable for site-specific weed detection and mapping [103].

UAVs also offer greater temporal flexibility, as they can be deployed on demand and timed to coincide with optimal phenological stages or favorable illumination conditions, unlike satellites that rely on fixed revisit schedules [101,102,104]. From an operational perspective, UAVs are generally more cost-effective than manned aircraft and reduce data acquisition costs by enabling frequent, field-scale monitoring using relatively low-cost sensors [101,106,107,108].

In addition, UAV platforms support advanced imaging modalities, including RGB, multispectral, and hyperspectral sensors, which enhance species-level discrimination and improve classification accuracy when combined with machine learning and deep learning approaches [107,109,110]. These capabilities facilitate near–real-time data processing and decision-making, which are difficult to achieve with traditional remote sensing platforms. Collectively, these advantages make UAV-based remote sensing particularly well suited for site-specific weed management, offering both environmental benefits through reduced chemical inputs and economic benefits through improved management efficiency [101,102,108,110].

5.2. UAV-Based Imaging Systems and Data Acquisition for Weed Detection

Unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) can rapidly acquire high-resolution imagery and detect weed patches across large agricultural areas within short time intervals [111]. Current research highlights three main camera types used for UAV-based weed detection: RGB, multispectral, and hyperspectral sensors. Image processing approaches such as conventional neural networks, deep neural networks, and object-based image analysis are commonly applied to analyze UAV imagery [112,113]. Detection accuracy is influenced by factors, including flight altitude, sensor resolution, and UAV platform characteristics.

Furthermore, UAVs integrated with Geographic Information System (GIS) technologies are increasingly applied in weed management strategies. The combination of UAVs with robotics, artificial intelligence, and additional sensors has been shown to improve detection accuracy, reduce labor requirements, and support more efficient agricultural management [7]. Weed detection systems can be broadly categorized into ground-based and UAV-based image acquisition platforms; however, UAVs are particularly well-suited for field crops and grasslands due to their rapid coverage and operational flexibility [114].

5.3. Type of Cameras for Weed Detection

UAV-based weed detection relies on various imaging sensors that differ in cost, spectral resolution, data volume, and detection accuracy. RGB imaging is widely available and cost-effective, offering high spatial resolution; however, it provides limited spectral information and is highly sensitive to illumination conditions, which reduces its accuracy for precise weed identification [103,115,116,117,118]. Multispectral cameras capture reflectance in multiple discrete wavebands beyond the visible spectrum, providing enhanced spectral information that improves weed crop discrimination compared to RGB imagery, albeit at higher cost and system complexity [103,115,118]. Hyperspectral imaging systems offer the highest spectral resolution, typically capturing hundreds of narrow spectral bands. These sensors enable detailed biochemical and structural analysis and generally achieve the highest weed detection accuracy. However, their practical use is constrained by high cost, large data volumes, and complex data processing requirements [116,119,120,121,122,123,124,125].

Other sensing technologies, including thermal imaging and LiDAR, are primarily used for specific applications such as irrigation management, plant water stress detection, and structural analysis. While valuable for crop monitoring, these sensors are not suitable for direct weed identification due to limited spectral discrimination capabilities [120,126]. Similarly, fluorescence imaging and ultrasonic sensing have niche applications in plant stress detection and structural analysis, respectively, but are not appropriate for comprehensive weed detection [120]. A detailed overview of imaging technologies used in agricultural weed detection, including their advantages, challenges, and applications, is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Overview of imaging technologies used in agriculture and weed detection, detailing their benefits, challenges, and specific applications.

5.4. Mitigation of Sensor Limitations and Emerging Solutions

Recent research has increasingly focused on overcoming the limitations of single-sensor UAV systems through sensor fusion, advanced data processing, and optimized operational strategies. The integration of RGB, multispectral, hyperspectral, and LiDAR data enables a more comprehensive characterization of weed-crop systems by combining spectral, structural, and contextual information, thereby improving discrimination accuracy under complex field conditions [120,131]. Such multimodal approaches are particularly effective for detecting small or early-stage weed patches that are difficult to identify using individual sensors alone.

Advances in deep learning architectures have further enhanced the value of fused UAV data. Object detection and segmentation models such as YOLO, Mask R-CNN, and transformer-based frameworks have demonstrated high accuracy in weed identification, even under variable illumination and canopy overlap [132,133]. Recent developments targeting small-object detection have shown improved performance and processing efficiency, supporting near–real-time applications in site-specific weed management [134]. To address challenges related to data scarcity and environmental variability, researchers have also explored synthetic data generation, data augmentation, and hybrid learning strategies, which improve model robustness across diverse field conditions [84,135].

From an operational perspective, UAV-based weed detection is increasingly embedded within site-specific weed management (SSWM) frameworks, enabling targeted interventions that reduce herbicide use and environmental impact [136,137]. The integration of UAV platforms with IoT-based decision support systems allows real-time monitoring, rapid data transmission, and timely management actions [138]. Machine learning plays a central role in these integrated systems by continuously adapting detection models to new data, weed species, and environmental conditions, thereby enhancing long-term reliability and scalability [107,139,140,141]. Collectively, these developments indicate a clear shift toward intelligent, integrated UAV systems that combine sensing, analytics, and decision support to enable sustainable weed management.

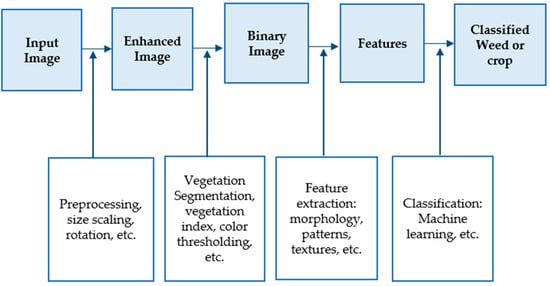

5.5. Image Processing and Machine Learning Workflows for Weed Detection

To differentiate weeds from crops, UAV-acquired images can be analyzed using a combination of spectral properties, morphological characteristics, texture features, and spatial context. A common method for weed detection is image processing, which includes steps such as preprocessing, segmentation, feature extraction, and classification [18], as illustrated in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Typical image processing procedures for weed identification [18].

Due to their potential to expand agricultural mapping, machine learning methods have generated significant interest in RS research during the past decade. The ability of machine learning algorithms for classifying weeds was shown to be effective [142]. The main machine learning (ML) algorithms utilized for weed detection in agricultural applications include supervised learning methods such as convolutional neural networks (CNNs) and the use of deep features for unsupervised data analysis. Deep learning (DL) enhances weed detection in precision agriculture by automating the identification of weeds, reducing herbicide use, and improving sustainability [55,66,68,143,144,145,146,147,148]. A detailed summary of the current state using the application of machine learning and deep learning in site-specific weed management is shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Comparative overview of Machine Learning (ML) and Deep Learning (DL) in site-specific weed management.

5.6. Synthesis of ML and DL Approaches for UAV-Based Weed Detection

As summarized in Table 2, machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL) approaches offer complementary strengths for site-specific weed management. ML methods are computationally efficient and suitable for resource-limited environments but rely on handcrafted features and often show reduced robustness under complex field conditions [131,156]. In contrast, DL models generally achieve higher detection accuracy and better generalization by automatically learning discriminative features, though they require large labeled datasets and substantial computational resources [157,158].

Recent research has focused on mitigating these limitations through transfer learning, data augmentation, lightweight network architectures, and sensor-aware model design [131,156,157,158,159]. While these strategies improve model scalability and real-time deployment on UAV platforms, challenges remain related to domain adaptation, synthetic data realism, accuracy–efficiency trade-offs, and sensitivity to environmental variability [131,159,160,161,162]. Addressing these issues is critical for developing robust and operational UAV-based weed detection systems.

Numerous research studies have been conducted lately to automate the process of classifying and identifying weeds. The machine-learning algorithm called support vector machine (SVM) was used for the effective classification of crops and weeds in digital images, and the results analysis shows that SVM covers a collection of 224 test photos with an accuracy of more than 97% [163].

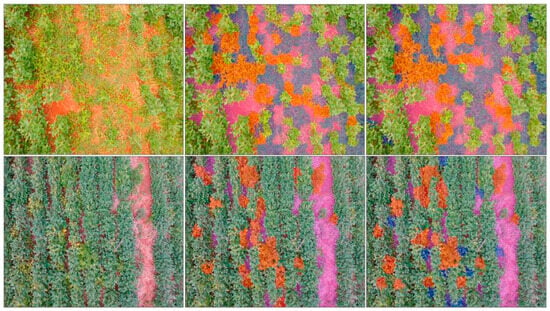

To identify weeds on soybean crop photos taken with a drone, ref. [164] applied a convolutional neural network (CNN—AlexNet), categorized the weeds as either grass or broadleaf, and then sprayed the appropriate herbicide on the weeds that were identified. According to this experiment, broadleaf and grass weeds without soil and soybeans in the background may be identified with 97% accuracy using CNN (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Original UAV image (left) and corresponding classifications by the ConvNet (center) and SVM (right). Broadleaf weeds are shown in red, grasses in blue, soil in purple, and soybean remains in natural color [164].

Ref. [142] used UAV-based multispectral imagery and machine learning for precise weed detection in Calabria, Italy. Four classification algorithms were assessed: K-Nearest Neighbour (KNN), Support Vector Machines (SVMs), Random Forests (RFs), and Normal Bayes (NB). Support Vector Machines and Random Forests showed high stability, with consistency obtained over 81% and 91.2% accuracy, respectively.

In [165], a deep learning strategy was applied for feature extraction from multispectral drone data to detect weeds in a lettuce field, achieving an F1 score of 94%. Furthermore, some other research is listed in Table 3, where various models, or the algorithm of deep learning or machine learning, were used for weed identification.

Table 3.

Additional studies that used various deep learning or machine learning models or algorithms for weed detection.

5.7. Applications of UAV and AI Methods for Ambrosia artemisiifolia Detection

A number of researchers use these technologies for weed detection on Ambrosia artemisiifolia. Ref. [171] used a Phantom 3 UAV flown at 10.1 m and an S1000 UAV flown at 8 m to collect high-resolution imagery for weed detection in soybean fields. The research integrated multispectral and thermal data to identify both common weed species and glyphosate-resistant biotypes at early growth stages. The study focused on four weed species: Ambrosia artimisifolia, Ambrosia rudis, Kochia scoparia, and Chenopodium album. Six supervised classifiers, Parallelepiped, Mahalanobis Distance, Maximum Likelihood, Spectral Angle Mapper, Support Vector Machine, and Decision Tree, were applied using pixel-based (PBIA) and object-based (OBIA) image analysis. OBIA achieved the highest performance, with overall accuracy exceeding 86%. Thermal photography was employed to identify glyphosate resistance by assessing variations in canopy temperature, resulting in classification accuracies of 88% for kochia, 93% for Amaranthus, and 92% for Ambrosia, showing the effectiveness of this method for (SSWM).

This research study presents a multi-format open-source weed image dataset designed to support real-time weed detection in precision agriculture. Five major weed species, including common ragweed, were documented using both aerial and ground-based imaging. Aerial data were collected with a DJI Phantom 4 Pro (V2.0) UAV equipped with its built-in 1-inch CMOS RGB camera, capturing high-resolution 5472 × 3648 px images at ~12 ft altitude to obtain clear weed features. Additional individual-plant images were taken using a Canon 90D handheld camera to enrich the dataset. Images were manually annotated using LabelImg and exported in TXT, XML, and JSON formats for training deep learning models. The final dataset contains 3975 images and 10,090 annotated weed instances, including 650 ragweed instances in aerial images. The dataset successfully provides diverse lighting, occlusion, and environmental conditions, making it suitable for training robust weed-detection models for both aerial and ground robotics applications [172]. Also, this conference paper showed that drones equipped with compressed deep neural networks can identify Ambrosia artemisiifolia efficiently from the air. By training detection and segmentation models and then optimizing them through shunt connections, knowledge distillation, and TensorRT, the system was able to run on an NVIDIA Jetson TX2 with inference times of 200–400 ms. This method significantly lowers the cost of ragweed monitoring and enables rapid, large-scale aerial detection [173].

Another study used RGB images captured with a Google Pixel 5 device equipped with a 12.2-MP main camera (F1.7 aperture, 28 mm focal length, 1.4 μm pixels) and a 16-MP ultra-wide camera (F2.2 aperture, 1 μm pixels). The researchers extracted texture features to categorize four weed species (horseweed, kochia, ragweed, waterhemp) and six crops (black bean, canola, corn, flax, soybean, sugar beets) utilizing Support Vector Machine (SVM) and VGG16 deep learning models, based on 3792 images captured in a greenhouse. The VGG16 model outperformed SVM, obtaining f1-scores between 93% and 97.5%, with an excellent 100% for maize, highlighting its applicability in site-specific weed management within precision agriculture [174]. The study used UAV-based sensing to detect glyphosate-resistant weeds, including kochia, waterhemp, redroot pigweed, and ragweed. A DJI M600 equipped with a Zenmuse XT2 thermal camera and Micasense RedEdge-MX Dual multispectral sensor captured canopy data, which were classified using Maximum Likelihood, Random Trees, and SVM learning methods. Multispectral features (NDVI and 705/740/842 nm bands) outperformed thermal imaging, with the best result, 87.2% accuracy for ragweed, achieved using the Random Trees classifier [115]. Using 5-band multispectral UAV imagery captured at 15 m, the study evaluated species differentiation among Palmer amaranth, common ragweed, and sicklepod at plant heights of 5, 10, 15, and 30 cm. Supervised image classification was applied and achieved 24–100% accuracy, with Palmer amaranth consistently identified at 100%, and ragweed and sicklepod showing lower but usable accuracy. Although spectral responses varied with species and height, clear separation, especially in bands 3 and 4n, demonstrated the potential of multispectral sensing for weed species discrimination [175].

Ref. [176] employed hyperspectral imaging using the Cubert UHD185 camera mounted on a tripod and used for ground-based imaging at a fixed distance of approximately 90 cm to detect invasive and weed species, such as (Ambrosia artemisiifolia, Euphorbia seguieriana, Atriplex tatarica, Glycyrrhiza glabra, and Setaria pumila) in grain agroecosystems following the harvest of winter wheat. Utilizing statistical approaches and machine learning techniques (Principal Component Analysis, decision tree, random forest), they computed 80 Vegetation Indices (VIs) successfully differentiating among weed types. The research emphasized VIs Derivative index (D1), Chlorophyll content index (Datt3), and Pigment specific normalized difference (PSND) as critical metrics for accurate weed identification.

Ref. [177] used a ground-based hyperspectral imaging system (400–1000 nm, ImSpector V10E spectrograph with a Pixelfly QE CCD camera mounted on a fixed indoor imaging setup) to differentiate Ambrosia artemisiifolia (ragweed) from Artemisia vulgaris (mugwort) across three growth stages by analyzing stem and leaf reflectance, particularly at 450, 550, 650, and 680–712 nm. The study found that wavelengths of 550 nm and 650 nm were especially effective for detecting A. artemisiifolia stems during the fruit development stage, regardless of the surrounding crop environment. The following section discusses these technical challenges and outlines future research directions for UAV-based SSWM.

6. Challenges, Limitations, and Future Directions of UAV-Based SSWM for Ambrosia artemisiifolia

While unmanned aerial vehicles have distinct benefits for high-resolution monitoring and mapping of weeds, numerous challenges and limitations constrain their operational application in site-specific weed management (SSWM) of Ambrosia artemisiifolia. These include challenges associated with data accuracy, scalability, and environmental effect, as well as technical, financial, regulatory, and operational issues. To overcome these obstacles, concerted efforts must be made to establish standardized protocols, enhance UAV technology, and offer users financial assistance and training [178,179,180,181].

6.1. Regulatory, Operational, and Economic Constraints

6.1.1. Fragmented Regulations

The deployment of UAVs may be restricted by the strict laws that frequently govern their operations. It is challenging to standardize UAV-based techniques for controlling Ambrosia artemisiifolia because these rules can differ greatly by location [178,179]. For instance, in Europe, the U-space concept aims to integrate UAVs into the airspace, but the regulatory framework is still evolving and varies between countries [182].

6.1.2. Safety and Risk Management

Regulatory authorities underscore safety, necessitating thorough risk evaluations and safety solutions for UAV operations, particularly in populated or crucial regions [183,184]. The Specific Operations Risk Assessment (SORA) framework assists in identifying and mitigating safety risks; however, it also introduces additional complexity to the regulatory approval process [184].

6.1.3. Technical and Operational Constraints

The deployment of UAVs in some circumstances may be limited by their need to adhere to operating limitations and technical standards [183]. Their application in the management of invasive species is further complicated by factors like airworthiness, flying duration, and range limitations [185].

6.1.4. Insurance, Liability, and Economic

Due to a lack of actuarial data, a lack of experience, and a great deal of regulatory uncertainty, aviation insurers have a difficult time offering adequate coverage for UAV operations. This complexity results from the fact that numerous countries do not have complete data on UAV incidents and accidents, and many UAV models have not been in use long enough to create reliable risk profiles, which adds another layer of complexity. To address this challenge of inefficient coverage, a multi-sector cooperation provision framework involving aviation insurers, the government, and UAV manufacturers has been proposed [186]. The implementation of UAVs is frequently obstructed by substantial initial expenses, encompassing the acquisition of the UAVs and requisite sensors and equipment [187,188].

6.2. Sensor and Image Acquisition Constraints

6.2.1. Solar Angle

The accuracy and robustness of classification models can be significantly affected by the high sensitivity of AV-based remote sensing to different lighting conditions, especially in RGB and multispectral images. Sun-camera geometry, including solar angle, strongly influences reflectance measurements. Even a 2° change in view angle can alter reflectance by more than ±50% of the nadir value 2, requiring correction for directional effects to ensure reliable data [189].

6.2.2. Flight Altitude and Spatial Resolution

Reflectance accuracy is also impacted by the angle at which incident light sensors (ILS) face the sun and the altitude of the aircraft [190]. Complex terrain and other topographic factors can skew sun illumination and interfere with optical remote sensing studies [191]. To identify individual weed plants in varied environments, good spatial resolution requires low-altitude aircraft [192,193,194]. Nonetheless, reduced altitudes reduce the covering area per image and increase the number of images needed, thus complicating the mission and increasing data volume [193,195]

6.2.3. Motion Blur and Platform Instability

Wind-related UAV instability can cause motion blur, reducing image quality and hindering accurate weed detection. This issue is amplified during high-speed flights, where rapid movements further intensify the blur [196,197,198]. A UAV-based photogrammetric inspection study quantified how motion blur degrades reconstruction accuracy. The researchers found that motion-induced blurring significantly distorts image features, increasing reconstruction standard deviation and peak-to-peak error by up to a factor of two under typical flight conditions. In the worst tested scenario, overall reconstruction error degraded by a factor of 13 compared to the optimal setup, demonstrating the severe sensitivity of image-based inspections to motion blur [197]. Similarly, another study noted that motion blur and other environmental factors could reduce the accuracy of weed detection models [199].

6.3. Weed–Crop Spectral and Structural Complexity

Ambrosia artemisiifolia poses significant challenges in agricultural fields due to having similar colors, textures, and shapes with crops and other broadleaf species, especially during early phenological stages, making them difficult to distinguish [141,200,201,202]. Crops and weeds, such as ragweed, have the same spectral signatures, especially in the visible and near-infrared (NIR) spectrum, complicating their differentiation using standard RGB or multispectral sensors [203,204,205]. The interaction of light with complex canopy structures might result in distorted or corrupted spectral data, hence hindering detection operations [206]. The application of particular Vegetation Indices (VIs), such as the Derivative index (D1), Chlorophyll content index (Datt3), and Pigment specific normalized difference (PSND), has demonstrated enhanced efficacy in identifying weed species, such as ragweed, even in obstructed situations [176].

6.4. Potential Directions to Overcome Limitations

Building on the technical and operational challenges discussed in previous sections, several priority research and development directions can help address current limitations in UAV-based detection of Ambrosia artemisiifolia. First, the use of optimized UAV platforms, particularly rotary-wing systems for low-altitude, high-resolution imaging and fixed-wing UAVs for larger-area surveys, can improve detection performance across different spatial scales [207,208,209,210]. Integrating multispectral and RGB data can also strengthen detection reliability across varying growth stages and environmental conditions [211].

Advanced computational methods are another priority. Deep neural networks (DNNs), including compressed models optimized for embedded platforms like Nvidia Jetson TX2, allow for faster and more accurate detection while enabling real-time or near–real-time processing onboard UAVs [173]. Complementary machine learning approaches, such as vegetation indices (e.g., TDVI), Support Vector Machines (SVM), Maximum Likelihood (ML) classifiers, and multilayer perceptrons (MLP-ARD), can assist in overcoming spectral instability and improving classification accuracy under variable lighting and field conditions [177,211,212]. Object-based image analysis and fuzzy-logic frameworks offer further benefits by incorporating spatial context and landscape characteristics, enabling stable prediction of ragweed likelihood in highly heterogeneous areas, including urban landscapes [210].

Optimizing flight parameters such as altitude, image overlap, and timing under stable illumination helps reduce blur, shadow effects, and spectral inconsistencies that currently hinder detection reliability [112,207]. Finally, improved detection algorithms, including YOLOv5-based models and novelty-detection classifiers, can better handle challenges such as overlapping leaves, morphological variability, and dense ragweed patches that commonly occur in the field [209,213]. These directives underline the necessity of integrating new sensing technologies, enhanced data processing methodologies, and optimized UAV operations to attain more resilient and scalable detection of Ambrosia artemisiifolia in varied situations.

7. Conclusions

Ambrosia artemisiifolia is among the most damaging invasive weeds affecting agricultural productivity and public health in Hungary and across Europe. In arable systems, it readily colonizes disturbed habitats and low-cover crop environments, where its competitiveness increases infestation pressure and contributes to yield losses and higher management costs [214,215,216]. Beyond agriculture, ragweed produces highly allergenic pollen that drives allergic rhinitis and asthma burdens in Central and Eastern Europe, with pollen and seed production varying across regions and seasons [36,214,217]. Accordingly, effective management requires prevention of further spread and scalable interventions, including disturbance reduction and sustainable options [218,219].

Uniform herbicide-based control is increasingly unsustainable due to environmental impacts, resistance risks, and regulatory pressure to reduce chemical inputs [220,221,222], consistent with goals such as the EU Green Deal [223]. Precision and site-specific weed management (SSWM) offer a practical alternative by enabling detection-driven interventions that reduce unnecessary herbicide use, which fundamentally depend on the spatially explicit characterization of vegetation condition derived from spectral remote sensing information [224,225,226]. In particular, UAV-based remote sensing supports flexible, on-demand, high-resolution monitoring for early-season detection and patch-level mapping [113], and recent advances in UAV weed detection using deep learning further improve the feasibility of producing actionable weed maps for targeted treatments [134,227].

UAV-based remote sensing using RGB, multispectral, and hyperspectral sensors provides high-resolution and timely weed detection that is not achievable with satellite platforms, particularly during early growth stages critical for effective control. Multispectral and hyperspectral data enhance weed-crop discrimination, while flexible UAV deployment enables targeted monitoring of invasive species such as Ambrosia artemisiifolia [107,228]. When combined with machine learning and deep learning models, including SVMs and CNNs, UAV imagery supports accurate weed mapping and site-specific herbicide application, reducing chemical inputs and environmental impacts [107,212,229].

Despite these advantages, several technical, sensor-related, operational, and regulatory challenges continue to limit the widespread adoption of UAV-based weed management. From a technical perspective, UAV operations are constrained by limited flight duration and payload capacity, which restrict sensor selection and coverage area [230,231]. Sensor-related challenges include the limited spectral information of RGB cameras, the high cost and large data volumes associated with multispectral and hyperspectral sensors, and image quality issues caused by variable illumination, motion blur, and platform instability, all of which affect detection accuracy and data processing efficiency [231,232,233]. In addition, onboard data processing and real-time analysis remain challenging, particularly for computationally intensive machine learning and deep learning models [232,233]. These technical constraints are compounded by high initial investment costs and regulatory restrictions on UAV operations, posing additional barriers for small and medium-sized farms, and highlighting the need for cooperative UAV-sharing schemes, policy support, and targeted training programs to enable broader adoption [185,188,234].

Future research should prioritize the development of lightweight and sensor-aware deep learning models, along with multi-sensor data fusion strategies, to improve the robustness and transferability of UAV-based detection of Ambrosia artemisiifolia under variable field conditions [173,228,235]. Particular emphasis should be placed on integrating RGB, multispectral, and hyperspectral imagery with optimized machine learning and deep learning architectures that enable real-time or near–real-time onboard processing [141,228,236,237]. In parallel, advances in mission planning, standardized acquisition protocols, and cloud edge computing frameworks are required to enhance the scalability and operational efficiency of UAV-based site-specific weed management [141,235]. Beyond technical developments, interdisciplinary research combining agronomy, ecology, and policy analysis is essential to evaluate long-term ecological impacts, address regulatory constraints, and support wider adoption through cooperative UAV-sharing models and targeted policy incentives [34,228,236]. Finally, effective translation of UAV-based technologies into practical and sustainable solutions for controlling Ambrosia artemisiifolia in Hungary and across Europe will depend on strong interdisciplinary collaboration among agronomists, engineers, data scientists, and policymakers, supported by targeted farmer training programs and enabling policy frameworks [187,238,239,240,241]. Such coordinated efforts are essential to overcome technical, economic, and regulatory barriers, promote adoption among small and medium-sized farms, and ensure that UAV-driven site-specific weed management contributes meaningfully to long-term agricultural sustainability [242,243,244].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.Y.H.; methodology, S.Y.H.; software, S.Y.H. and G.M.; validation, S.Y.H.; resources, S.Y.H.; data curation, S.Y.H. and G.M.; writing—original draft preparation, S.Y.H.; writing—review and editing, S.Y.H.; supervision and funding acquisition, G.M. and G.P.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the support of the Hungarian University of Agriculture and Life Sciences (MATE) and the Stipendium Hungaricum Scholarship Programme. The publication of this article was financially supported by MATE and the Stipendium Hungaricum Scholarship.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Networks |

| D1 | Derivative Index |

| DL | Deep Learning |

| EAN | European Aeroallergen Network |

| EPI | European Pollen Information |

| FAO | Food and Agriculture Organization |

| GPU | Graphic Processing Unit |

| ILS | Incident Light Sensors |

| KNN | K-Nearest Neighbour |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| NB | Naïve Bayes |

| OBIA | Object-Based Image Analysis |

| PA | Precision Agriculture |

| PBIA | Pixel-Based Image Analysis |

| PSND | Pigment-Specific Normalized Difference |

| RF | Random Forests |

| RGB | Red, Green, Blue |

| RPAAS | Remotely Piloted Aerial Application Systems |

| SDM | Species Distribution Models |

| SORA | Specific Operations Risk Assessment |

| SSWM | Site-Specific Weed Management |

| SVM | Support Vector Machines |

| UAVs | Unmanned Aerial Vehicles |

| Vis | Vegetation Indices |

| WSSA | Weed Science Society of America |

References

- FAO. How to feed the world in 2050. Insights from an expert meet. In Insights from an Expert Meeting at FAO; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2009; Volume 2050, pp. 1–35. [Google Scholar]

- Castellano, G.; De Marinis, P.; Vessio, G. Weed mapping in multispectral drone imagery using lightweight vision transformers. Neurocomputing 2023, 562, 126914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, M.; Driscoll, A.; Lobell, D.B.; Ermon, S. Using satellite imagery to understand and promote sustainable development. Science 2021, 371, eabe8628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vougioukas, S.G. Agricultural Robotics. Annu. Rev. Control Robot. Auton. Syst. 2019, 2, 365–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stafford, J.V. Implementing precision agriculture in the 21st century. J. Agric. Eng. Res. 2000, 76, 267–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Wang, M.; Wang, N. Precision agriculture—A worldwide overview. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2002, 36, 113–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meesaragandla, S.; Jagtap, M.P.; Khatri, N.; Madan, H.; Vadduri, A.A. Herbicide spraying and weed identification using drone technology in modern farms: A comprehensive review. Results Eng. 2024, 21, 101870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijayakumar, V.; Ampatzidis, Y.; Schueller, J.K.; Burks, T. Smart spraying technologies for precision weed management: A review. Smart Agric. Technol. 2023, 6, 100337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abo-Habaga, M.; Imara, Z.; Okasha, M. Development of a Combine Hoeing Machine for Flat and Ridged Soil. J. Soil Sci. Agric. Eng. 2018, 9, 817–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roshan, P.; Kulshreshtha, A.; Hallan, V. Global Weed-Infecting Geminiviruses. In Geminiviruses: Impact, Challenges and Approaches; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Zandstra, B.H.; Motooka, P.S. Beneficial Effects of Weeds in Pest Management—A Review. PANS 1978, 24, 333–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffus, J.E. Role of Weeds in the Incidence of Virus Diseases. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 1971, 9, 319–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byron, M.; Treadwell, D.D.; Dittmar, P.J. Weeds as Reservoirs of Plant Pathogens Affecting Economically Important Crops. Edis 2019, 2019, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makra, L.; Juhász, M.; Borsos, E.; Béczi, R. Meteorological variables connected with airborne ragweed pollen in Southern Hungary. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2004, 49, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sala, O.E.; Stuart Chapin, F.; Armesto, J.J.; Berlow, E.; Bloomfield, J.; Dirzo, R.; Huber-Sanwald, E.; Huenneke, L.F.; Jackson, R.B.; Kinzig, A.; et al. Global Biodiversity Scenarios for the Year 2100. Science 2000, 287, 1770–1774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitousek, P.M.; Mooney, H.A.; Lubchenco, J.; Melillo, J.M. Human Domination of Earth’s Ecosystems. Science 1997, 277, 494–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, B.A.; Blumenthal, D.M.; Wilcove, D.S.; Ziska, L.H. Predicting plant invasions in an era of global change. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2010, 25, 310–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Bruch, R. Weed Detection for Selective Spraying: A Review. Curr. Robot. Rep. 2020, 1, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanini, W.T.; Le Strange, M. Low-input management of weeds in vegetable fields. Calif. Agric. 1991, 45, 11–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amare, T.; Sharma, J.J.; Zewdie, K. Effect of Weed Control Methods on Weeds and Wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) Yield. World J. Agric. Res. 2014, 2, 124–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bullock, J.M.; Chapman, D.; Schafer, S.; Roy, D.; Girardello, M.; Haynes, T.; Beal, S.; Wheeler, B.; Dickie, I.; Phang, Z.; et al. Assessing and Controlling the Spread and the Effects of Common Ragweed in Europe. Final report: ENV. B2/ETU/2010/0037. 2010. Available online: https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&source=web&rct=j&opi=89978449&url=https://circabc.europa.eu/sd/d/d1ad57e8-327c-4fdd-b908-dadd5b859eff/FinalFinalReport.pdf&ved=2ahUKEwia-uam__WRAxXz3AIHHbvoAFQQFnoECBgQAQ&usg=AOvVaw2C0iNelILWHrjMUvTr13lK (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Jager, O.R.S. Ambrosia (ragweed) in Europe. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Int. 2001, 13, 60–66. [Google Scholar]

- Jäger, S. Global aspects of ragweed in Europe. In Proceedings of the 6th International Congress on Aerobiology. Satellite Symposium Proceedings: Ragweed in Europe, Perugia, Italy, 22–26 August 1998; ALK Abelló: Hørsholm, Denmark, 1998; pp. 6–10. [Google Scholar]

- Juhász, M. History of ragweed in Europe. In Proceedings of the 6th International Congress on Aerobiology. Satellite Symposium Proceedings: Ragweed in Europe, Perugia, Italy, 22–26 August 1998; ALK Abelló: Hørsholm, Denmark, 1998; pp. 11–14. [Google Scholar]

- Makra, L.; Matyasovszky, I.; Deák, Á.J. Ragweed in Eastern Europe. In Invasive Species and Global Climate Change; CABI: Wallingford, UK, 2014; pp. 117–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaudeul, M.; Giraud, T.; Kiss, L.; Shykoff, J.A. Nuclear and chloroplast microsatellites show multiple introductions in the worldwide invasion history of common ragweed, Ambrosia artemisiifolia. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e17658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makra, L.; Matyasovszky, I.; Hufnagel, L.; Tusnády, G. The history of ragweed in the world. Appl. Ecol. Environ. Res. 2015, 13, 489–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Járai-Komlódi, M.; Juhász, M. Ambrosia elatior (L.) in Hungary (1989–1990). Aerobiologia 1993, 9, 75–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makra, L.; Juhász, M.; Béczi, R.; Borsos, E.K. The history and impacts of airborne Ambrosia (Asteraceae) pollen in Hungary. Grana 2005, 44, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Aeroallergen Network (EAN). Distribution of Ambrosia artemisiifolia Pollen in Europe. 2025. Available online: https://ean.polleninfo.eu/Ean (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- European Pollen Information (EPI). Pollen Information and Ragweed Pollen Distribution Data. 2025. Available online: https://www.polleninformation.at/en/allergy/pollen-load-map-of-europe (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Tóth, Á.; Hoffmanné, P.Z.; Szentey, L. A parlagfű (Ambrosia elatior) helyzet 2003-ban Magyarországon. A Levegő Pollenszám Csökkentésének Nehézségei 2004, 14. [Google Scholar]

- Pinke, G.; Kolejanisz, T.; Vér, A.; Nagy, K.; Milics, G.; Schlögl, G.; Bede-Fazekas, Á.; Botta-Dukát, Z.; Czúcz, B. Drivers of Ambrosia artemisiifolia abundance in arable fields along the Austrian-Hungarian border. Preslia 2019, 91, 369–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knolmajer, B.; Jócsák, I.; Taller, J.; Keszthelyi, S.; Kazinczi, G. Common Ragweed—Ambrosia artemisiifolia L.: A Review with Special Regards to the Latest Results in Protection Methods, Herbicide Resistance, New Tools and Methods. Agronomy 2025, 15, 1765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerber, E.; Schaffner, U.; Gassmann, A.; Hinz, H.L.; Seier, M.; Müller-Schärer, H. Prospects for biological control of Ambrosia artemisiifolia in Europe: Learning from the past. Weed Res. 2011, 51, 559–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leru, P.M.; Eftimie, A.M.; Anton, V.F.; Thibaudon, M. Assessment of the risks associated with the invasive weed Ambrosia artemisiifolia in urban environments in Romania. Ecocycles 2019, 5, 56–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohren, C.; Mermillod, G.; Delabays, N. Ambrosia artemisiiifolia L.—Control measures and their effects on its capacity of reproduction. J. Plant Dis. Proctection 2008, 21, 311–316. [Google Scholar]

- Attila, M. Ambrosia vs. authority: Tasks, methods and results of the land management in ragweed prevention and monitoring of common interest. Geod. Kartogr. 2009, 61, 32–34. [Google Scholar]

- Vidović, B.; Cvrković, T.; Rančić, D.; Marinković, S.; Cristofaro, M.; Schaffner, U.; Petanović, R. Eriophyid mite Aceria artemisiifoliae sp.nov. (Acari: Eriophyoidea) potential biological control agent of invasive common ragweed, Ambrosia artemisiifolia L. (Asteraceae) in Serbia. Syst. Appl. Acarol. 2016, 21, 919–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lommen, S.T.; Jolidon, E.F.; Sun, Y.; Bustamante Eduardo, J.I.; Müller-Schärer, H. An early suitability assessment of two exotic Ophraella species (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae) for biological control of invasive ragweed in Europe. Eur. J. Entomol. 2017, 114, 160–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dirr, L.; Bastl, K.; Bastl, M.; Berger, U.E.; Bouchal, J.M.; Kofol Seliger, A.; Magyar, D.; Ščevková, J.; Szigeti, T.; Grímsson, F. The Ragweed Finder: A Citizen-Science Project to Inform Pollen Allergy Sufferers About Ambrosia artemisiifolia Populations in Austria. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 12333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valkó, O.; Deák, B.; Török, P.; Kelemen, A.; Miglécz, T.; Tóth, K.; Tóthmérész, B. Abandonment of croplands: Problem or chance for grassland restoration? case studies from hungary. Ecosyst. Health Sustain. 2016, 2, e01208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazinczi, G.; Beres, I.; Novák, R.; Biro, K.; Pathy, Z. Common ragweed (Ambrosia artemisiifolia): A review with special regards to the results in Hungary. I. Taxonomy, origin and distribution, morphology, life cycle and reproduction strategy. Herbologia 2008, 9, 55–91. [Google Scholar]

- Qin, Z.; Mao, D.J.; Quan, G.M.; Zhang, J.-E.; Xie, J.F.; DiTommaso, A. Physiological and morphological responses of invasive Ambrosia artemisiifolia (common ragweed) to different irradiances. Botany 2012, 90, 1284–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Xue, Z.; Liu, T.; Wang, H.; Han, Z. Factors affecting establishment and population growth of the invasive weed Ambrosia artemisiifolia. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1251441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.; Cecchi, L.; Skjøth, C.A.; Karrer, G.; Šikoparija, B. Common ragweed: A threat to environmental health in Europe. Environ. Int. 2013, 61, 115–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sărățeanu, V.; Moisuc, A.; Cotuna, O. Ambrosia artemisiifolia L. an invasive weed from ruderal areas to disturbed grasslands. Lucr. Ştiinţifice—Ser. Agron. 2010, 53, 235–238. [Google Scholar]

- Lehoczky, E.; Szabó, R.; Nelima, M.O.; Nagy, P.; Béres, I. Examination of common ragweed’s (Ambrosia artemisiifolia L.) allelopathic effect on some weed species. Commun. Agric. Appl. Biol. Sci. 2010, 75, 107–111. [Google Scholar]

- Lehoczky, E.; Gólya, G.; Szabó, R.; Szalai, A. Allelopathic effects of ragweed (Ambrosia artemisiifolia L.) on cultivated plants. Commun. Agric. Appl. Biol. Sci. 2011, 76, 545–549. [Google Scholar]

- Beam, S.C.; Cahoon, C.W.; Haak, D.C.; Holshouser, D.L.; Mirsky, S.B.; Flessner, M.L. Integrated Weed Management Systems to Control Common Ragweed (Ambrosia artemisiifolia L.) in Soybean. Front. Agron. 2021, 2, 598426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pannacci, E.; Lattanzi, B.; Tei, F. Non-chemical weed management strategies in minor crops: A review. Crop Prot. 2017, 96, 44–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, K.; Shu, L.; Xie, Q.; Song, M.; Zhu, Y.; Cao, W.; Ni, J. Precision weed detection in wheat fields for agriculture 4.0: A survey of enabling technologies, methods, and research challenges. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2023, 212, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carver, B.F. Wheat Science and Trade; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2009; pp. 1–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Authority, E.F.S. The 2015 European Union report on pesticide residues in food. EFSA J. 2017, 15, e04791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasan, A.S.M.M.; Sohel, F.; Diepeveen, D.; Laga, H.; Jones, M.G.K. A survey of deep learning techniques for weed detection from images. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2021, 184, 106067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiles, L.J. Beyond patch spraying: Site-specific weed management with several herbicides. Precis. Agric. 2009, 10, 277–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, N.; Zhang, Y.; Ram, B.G.; Schumacher, L.; Yellavajjala, R.K.; Bajwa, S.; Sun, X. Applications of deep learning in precision weed management: A review. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2023, 206, 107698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Costa Lima, A.; Mendes, K.F. Variable Rate Application of Herbicides for Weed Management in Pre- and Postemergence. In Pests, Weeds and Diseases in Agricultural Crop and Animal Husbandry Production; Kontogiannatos, D., Kourti, A., Mendes, K.F., Eds.; IntechOpen: Rijeka, Croatia, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velumani, K.; Madec, S.; de Solan, B.; Lopez-Lozano, R.; Gillet, J.; Labrosse, J.; Jezequel, S.; Comar, A.; Baret, F. An automatic method based on daily in situ images and deep learning to date wheat heading stage. Field Crops Res. 2020, 252, 107793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbedo, J.G.A. Detection of nutrition deficiencies in plants using proximal images and machine learning: A review. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2019, 162, 482–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madeshwar, M.; Priyan, M.V.; Manvizhi, N. Hybrid Vision Transformer and CNN-Based System for Real-Time Weed Detection in Precision Agriculture. In Proceedings of the 2025 International Conference on Emerging Technologies in Engineering Applications, ICETEA, Puducherry, India, 5–6 June 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazrafkan, A.; Kosugi, Y.; Flores, P. A machine learning extension built on ArcGIS for the detection of weeds in cornfields. In Proceedings of the 2024 ASABE Annual International Meeting, Anaheim, CA, USA, 28–31 July 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Sharma, S.; Malik, A.; Sobti, R.; Hussain, M. Enhancing Sustainable Farming with Automated Weed Detection: A Hybrid Approach Using Image Processing and Machine Learning; Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems, LNNS; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; Volume 1399, pp. 54–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunil, G.C.; Upadhyay, A.; Zhang, Y.; Howatt, K.; Peters, T.; Ostlie, M.; Aderholdt, W.; Sun, X. Field-based multispecies weed and crop detection using ground robots and advanced YOLO models: A data and model-centric approach. Smart Agric. Technol. 2024, 9, 100538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Ortiz, M.; Peña, J.M.; Gutiérrez, P.A.; Torres-Sánchez, J.; Hervás-Martínez, C.; López-Granados, F. Selecting patterns and features for between- and within- crop-row weed mapping using UAV-imagery. Expert. Syst. Appl. 2016, 47, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Badri, A.H.; Ismail, N.A.; Al-Dulaimi, K.; Salman, G.A.; Khan, A.R.; Al-Sabaawi, A.; Salam, M.S.H. Classification of weed using machine learning techniques: A review—Challenges, current and future potential techniques. J. Plant Dis. Prot. 2022, 129, 745–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shilaskar, S.; Gholap, R.; Bhatlawande, S.; Ranade, N.; Ghadge, S. Computer Vision Based Detection of Weed in Ginger and Sugarcane Crop for Automated Farming System. In Proceedings of the 2023 International Conference on IoT, Communication and Automation Technology, ICICAT 2023, Gorakhpur, India, 23–24 June 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhinata, F.D.; Wahyono Sumiharto, R. A comprehensive survey on weed and crop classification using machine learning and deep learning. Artif. Intell. Agric. 2024, 13, 45–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Villiers, C.; Munghemezulu, C.; Mashaba-Munghemezulu, Z.; Chirima, G.J.; Tesfamichael, S.G. Weed Detection in Rainfed Maize Crops Using UAV and PlanetScope Imagery. Sustainability 2023, 15, 13416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavitha, K.; Gopalakrishnan, K.; Balaji, S.; Jeevanantham, J.; Aakhila Hayathunisa, M. Crop Classification using Convolutional Neural Network. In Proceedings of the 15th International Conference on Advances in Computing, Control, and Telecommunication Technologies, ACT 2024, Hyderabad, India, 21–22 June 2024; Volume 2, pp. 5438–5444. [Google Scholar]