Abstract

Agriculture faces growing pressure to optimize water use, particularly in woody perennial crops where irrigation systems are installed once and seldom redesigned despite changes in canopy structure, soil conditions, or plant mortality. Such static layouts may accumulate inefficiencies over time. This study introduces a decision support system (DSS) that evaluates the hydraulic adequacy of existing irrigation systems using two new concepts: the Resource Overutilization Ratio (ROR) and the Irrigation Ecolabel. The ROR quantifies the deviation between the actual discharge of an installed irrigation network and the theoretical discharge required from crop water needs and user-defined scheduling assumptions, while the ecolabel translates this value into an intuitive A+++–D scale inspired by EU energy labels. Crop water demand was estimated using the FAO-56 Penman–Monteith method and adjusted using canopy cover derived from UAV-based canopy height models. A vineyard case study in Galicia (Spain) serves an example to illustrate the potential of the DSS. Firstly, using a fixed canopy cover, the FAO-based workflow indicated moderate oversizing, whereas secondly, UAV-derived canopy measurements revealed substantially higher oversizing, highlighting the limitations of non-spatial or user-estimated canopy inputs. This contrast (A+ vs. D rating) illustrates the diagnostic value of integrating high-resolution geospatial information when canopy variability is present. The DSS, released as open-source software, provides a transparent and reproducible framework to help farmers, irrigation managers, and policymakers assess whether existing drip systems are hydraulically oversized and to benchmark system performance across fields or management scenarios. Rather than serving as an irrigation scheduler, the DSS functions as a standardized diagnostic tool for identifying oversizing and supporting more efficient use of water, energy, and materials in perennial cropping systems.

1. Introduction

Irrigation is a critical part of agricultural practices, consuming approximately 70% of freshwater resources in Spain [1,2], a similar percentage across southern European countries [3]; 80% in China [4], and up to 86% in Latin American and Caribbean regions [5]. This extensive use underscores the essential role of irrigation in enabling crop growth in areas with insufficient rainfall. Effective irrigation practices are therefore fundamental for maximizing crop yields, ensuring food security, and sustaining the agricultural economy. Given its substantial share of global water use, optimizing irrigation methods to conserve water while maintaining crop health and productivity is of paramount importance.

Climate change significantly affects crop water needs, with direct implications for agricultural production and food security [6,7]. Rising temperatures [8], altered rainfall patterns [9], and increased evapotranspiration rates [10] are intensifying water stress in many agricultural regions, particularly in arid and semi-arid zones. In some areas, this has reduced crop yield and quality, while in others it has created opportunities for new crops and more resilient farming practices. To address these challenges, farmers and policymakers must implement strategies to improve the efficiency of water use at field and system level [11]. The FAO-56 Penman-Monteith method [12] is widely used to estimate crop water requeriments, serving as the foundation for calculating irrigation needs. It relies on reference evapotranspiration (ET0), which represents the water loss from a hypothetical reference crop and is derived from meteorological data such as temperature, humidity, wind speed, and solar radiation. Experts then adjust ET0 using parameters that reflect crop type, phenological stage, and local conditions.

The FAO-56 approach provides a standardized methodology for estimating crop water requirements and helps avoid under- or over-irrigation, both of which can reduce yield, waste water, or increase environmental impacts. When appropriately parameterized, provides consistent and widely accepted estimates of ET0. However, discrepancies may arise when meteorological inputs are not representative, or when crop coefficients (Kc) are poorly adapted to local conditions. Reported limitations include errors of up to −30% in daily evaporation estimates and potential overestimation of water demand when compared with other evapotranspiration models [13], as well as underestimation of potential evapotranspiration by 2–10% [14]. Additional challenges stem from the method’s assumptions of uniform canopy cover (CC) and soil moisture, which rarely align with real field conditions. Moreover, the method does not account for factors such as soil salinity [15]. Despite these limitations, FAO-56 remains the standard method in agricultural engineering due to its transparency, low data requirements, and reproducibility, estimating crop water needs and guiding irrigation management decisions. However, it is recommended to use it in combination with other methods and field measurements. Despite these limitations, the FAO method remains a valuable tool for irrigation management, particularly when combined with complementary sources of information such as soil moisture data, canopy temperature, water stress indicators (e.g., CWSI), or leaf water potential measurements [10,16].

Achieving high irrigation efficiency requires both appropriate system design and proper management. Determining crop water requirements is the first essential step, as this information guides the agronomic and hydraulic design of the irrigation system. Efficient technologies such as pressurized or drip irrigation systems [17], along with soil moisture monitoring [18], can then be implemented. Irrigation should also be scheduled under suitable meteorological conditions (for example, avoiding wind during sprinkler irrigation, applying water at night, and ensuring adequate pressure) to align water application with crop needs throughout the growing season. Irrigation in woody crops presents additional challenges due to their perennial nature. Deep root systems require precise and consistent water delivery [19], and long maturation periods demand sustainable, long-term irrigation strategies [20] that consider variable water availability and changing climatic conditions. Extensive canopy cover can further increase evapotranspiration [21].

Unlike annual crops such as maize, which often require seasonal installation and removal of irrigation systems, woody crops typically rely on permanent irrigation infrastructure. These long-term systems must accommodate changes in plant size, canopy structure, and root development over time. Drip irrigation is commonly used in woody crops to deliver water efficiently to the root zone [22]. Such systems frequently incorporate pressure-compensating emitters or subsurface installations to maintain uniform distribution, even under variable terrain or as plants mature. Automation technologies—including soil moisture sensors and irrigation controllers—can further enhance system performance by enabling real-time adjustments based on environmental or crop-specific conditions [23].

A poorly designed irrigation system for woody crops can have long-term negative effects on both productivity and sustainability. Inadequate designs often emphasize hydraulic and geometric parameters while overlooking agronomic and dynamic factors that should adapt irrigation to crop development and soil conditions. This can result in uneven distribution, inefficient resource use, and chronic over- or under-irrigation, ultimately reducing crop health and yield [24]. Even a well-designed system may become less effective as field conditions evolve or maintenance deteriorates. Furthermore, irrigation practices are often inefficiently managed, highlighting the need for methods to periodically assess whether an installed system remains properly dimensioned.

Precision agriculture incorporates modern technologies, data, and analytics to optimize resource use, improve crop productivity, and enhance sustainability. It enables the development of tailored irrigation strategies, allowing farmers to reduce water consumption and environmental impact while maintaining or increasing yield levels. Remote sensing technologies have become essential tools within precision agriculture, providing multi-scale monitoring of crop and soil conditions. Data acquired from UAVs, aircraft, nanosatellites, and satellites are used for tasks such as disease detection [25,26], identification of missing plants [27], estimation of vegetation indices for crop management [28,29], and monitoring of crop water stress [30]. Compared to ground-based methods, remote sensing enables rapid, large-scale data acquisition and non-destructive monitoring. Nonetheless, it is most effective when used in conjunction with proximal sensing, where in situ data support calibration and validation. When integrated with precision irrigation and smart farming technologies, these methods can support improved irrigation decisions and contribute to more efficient water management.

Many stakeholders have taken steps to optimize irrigation scheduling and reduce water waste. In Spain, the “Sistema de Información Agroclimática para el Regadío (SiAR)” provides high-quality agroclimatic data for irrigation planning, management, and control. However, existing irrigation infrastructures in woody crops are rarely evaluated to determine whether they remain appropriately dimensioned as conditions change. Producers often lack information about whether their systems are still suited to their crops’ needs, especially in the presence of changes in variety, soil water retention capacity, or equipment performance due to inadequate maintenance. Furthermore, the introduction of a water-use efficiency label could support policymakers, farmers, and consumers. Studies show that consumers increasingly value information about water use in the production of both fresh and processed agricultural products [31].

To address these challenges, this research introduces a Decision Support System (DSS) that incorporates two original concepts: the Resource Overutilization Ratio (ROR) and the Irrigation Ecolabel. The DSS provides a standardized and quantitative framework that evaluates the hydraulic efficiency of installed irrigation systems by quantifying oversizing in drip-irrigated woody crops. Using FAO-56 Penman–Monteith calculations and UAV-derived canopy cover, the irrigation network was theoretically redesigned and compared with the existing installation. The ROR quantifies the degree of overuse, while the Irrigation Ecolabel— inspired by the European Union (EU) energy efficiency labels [32], though not affiliated with the official EU Ecolabel scheme—translates this metric into an intuitive scale from “A” (highly efficient) to “G” (highly inefficient). This approach, proposed for the first time in this study, addresses a critical gap in irrigation management by integrating crop-water modelling, hydraulic parameters, and geospatial data into a unified decision-making framework.

Unlike conventional irrigation scheduling tools that estimate daily irrigation doses, the proposed DSS provides a standardized diagnostic of the hydraulic performance of installed drip irrigation systems. The framework can be repeatedly applied in different years or seasons, enabling consistent performance benchmarking through a standardized ecolabel system, supporting policy adoption. Finally, to demonstrate the potential of the DSS, a case study was conducted in a vineyard using publicly available datasets.

2. Material and Methods

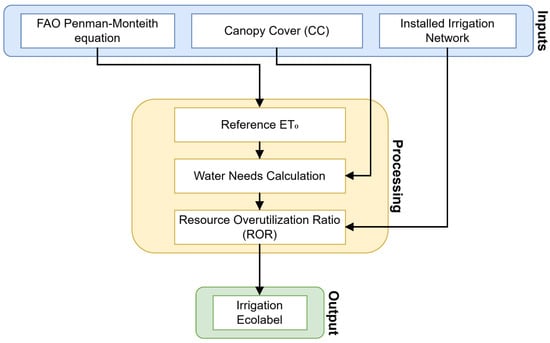

Figure 1 presents a simplified diagram of the research workflow, outlining the architecture of the system. The process begins with the input of parameters from the installed irrigation network, the FAO-56 Penman–Monteith equation, and—when available—UAV-derived crop data. These inputs are processed to calculate water requirements, which are then compared with the installed system parameters (which do not necessarily have to correspond to the initial system’s design parameters) to derive the Resource Overutilization Ratio (ROR). The ROR serves as the basis for generating the Irrigation Ecolabel.

Figure 1.

Simplified overview of the Decision Support System (DSS) and the Irrigation Ecolabel calculation.

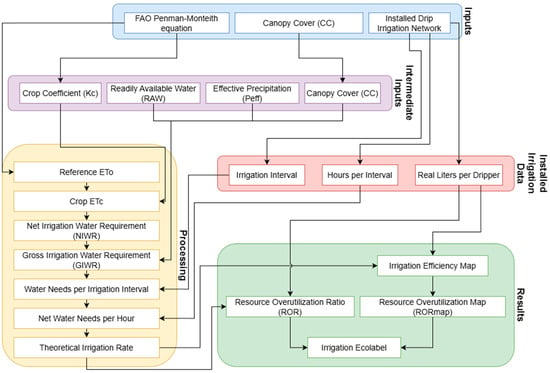

Figure 2 provides a more detailed representation of the DSS, illustrating the intermediate steps used to calculate the Irrigation Ecolabel. The inputs feed into several modules that estimate key parameters such as reference evapotranspiration (ET0), crop evapotranspiration (ETc), and net irrigation water requirement (NIWR). Intermediate variables such as effective precipitation (Peff), Available Water (AW), crop coefficient (Kc), and canopy cover (CC) further refine the estimates. These outputs inform the calculation of the ROR, visualized through maps and ratios, which ultimately lead to the assignment of the Irrigation Ecolabel.

Figure 2.

Workflow of the Decision Support System (DSS) for calculating hydraulic oversizing and sustainability. Inputs include the installed irrigation network, FAO Penman–Monteith equation, and canopy cover data. The processing steps estimate ET0, ETc, NIWR, and GIWR. Intermediate variables include RAW, Peff, and CC. Installed irrigation parameters include the irrigation interval, irrigation duration, and dripper discharge. Outputs include ROR, maps of ROR (hydraulic oversizing), and the final Irrigation Ecolabel.

2.1. Water Requirement Calculation Methodology

The FAO-56 Penman–Monteith method [12] was used to estimate reference evapotranspiration (ET0), which serves as the foundation for calculating crop evapotranspiration (ETc) and irrigation requirements. For each day of the study period, ET0 values were obtained from the nearest agro-meteorological station. Crop evapotranspiration was calculated using:

where Kc is the crop coefficient associated with crop type and phenological stage. Kc values were taken from FAO-56 recommendations and adjusted when required using canopy information. Since these equations are extensively documented in the FAO manual, they are not reproduced here.

In this study, Canopy Cover (CC), when available, was incorporated as a weighting factor to adjust Kc according to the spatial extent of canopy development, thereby refining ETc estimates in woody crops.

The net irrigation water requirement (NIWR) represents the net amount of water that must reach the root zone to offset evapotranspiration losses:

where RAW (Readily Available Water) is a portion of the total soil Available Water (AW), typically approximated as two-thirds of AW depending on soil texture.

To account for irrigation system performance, the gross irrigation water requirement (GIWR) was calculated by correcting NIWR using irrigation efficiency , assumed as 0.9 for drip irrigation [33]:

The irrigation interval (II, days) and duration of each irrigation event (Nh, hours) were used to convert water requirements into flow values compatible with the installed system:

The net water demand (NWD) represents the required hourly water supply during each irrigation event.

The DSS then computes the theoretical irrigation rate—expressed as the required discharge per dripper—using:

where Aeff is the effective irrigation width per dripper and is the number of emitters supplying that area. These values are used to compare the theoretical and actual discharge (i.e., the installed nominal emitter discharge) and compute the ROR. This study focused on the most demanding irrigation period (summer) and considered drip irrigation, consistent with standard practices in woody crops.

2.2. Resource Overutilization Ratio (ROR)

The Resource Overutilization Ratio (ROR) is a novel index that quantifies the deviation between the actual discharge of the irrigation system and the theoretical discharge required to meet crop water needs. It is defined as:

where is the discharge delivered by the installed emitters (actual flow). Positive ROR values indicate overutilization (excess water applied), negative values indicate underutilization, and a value of 0% represents perfect alignment between actual and theoretical water delivery.

2.3. Irrigation Ecolabel

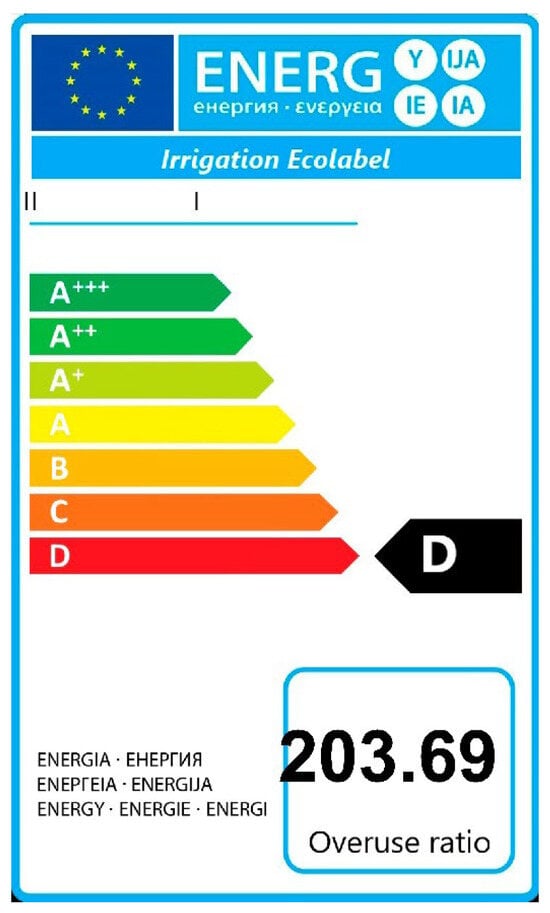

The Irrigation Ecolabel provides a sustainability-oriented classification of irrigation systems based on the ROR. Inspired by the EU energy efficiency labels [34], but not associated with the official EU Ecolabel scheme, it translates hydraulic performance into an intuitive A+++–D scale. Classification thresholds are based on degrees of over-irrigation reported in previous studies [35,36,37,38,39], not by water-use-efficiency metrics. The rating ranges are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Irrigation ecolabel values for field classification.

2.4. Software Overview

The developed software integrates the DSS, combining FAO-56 crop-water calculations with optional UAV-derived canopy data. It processes meteorological inputs, irrigation system characteristics, and geospatial data to compute the ROR and assign the Irrigation Ecolabel.

2.4.1. Implementation Details

The DSS was implemented in Python (v3.10) following a modular architecture that separates evapotranspiration computation, irrigation network characterization, geospatial processing, and visualization/reporting. Additional details are explained in the Supplementary Material Text S1.

2.4.2. Software Usage

The software guides the user through a workflow that includes:

- (1)

- entering meteorological data or importing values from a reference station;

- (2)

- providing irrigation system information (dripper flow, spacing, irrigation efficiency, and irrigation interval);

- (3)

- optionally importing UAV-derived canopy cover data;

- (4)

- performing the required water-demand and efficiency calculations; and

- (5)

- generating visual outputs and an optional PDF report.

Additional details are explained in the Supplementary Material Text S1, while a complete list of all user-provided inputs required during execution of the DSS is summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Required user inputs for running the Decision Support System (DSS).

2.4.3. Sample Execution

When launched, the software displays a welcome message and provides access to the user manual. The user is then guided through a sequence of input steps to specify the required meteorological parameters for ET0 and ETc, describe the characteristics of the existing irrigation system, and, if desired, load geospatial information derived from UAV imagery. After the inputs are completed, the software automatically performs all calculations, generates the ROR, Irrigation Ecolabel and the corresponding visual outputs, and offers the option to produce a comprehensive PDF report summarizing the results.

The full software package and source code are openly available at: https://github.com/druzzo/IrrigationEcolabel (accessed on 26 September 2025), An instructional video demonstrating the workflow is included in the README section of the repository.

2.5. Case Study Example: Irrigation in a Vineyard

This section illustrates how the methodology is applied in practice. The values are specific to the vineyard used as an example but demonstrate how the DSS can be adapted to other orchards:

2.5.1. Vineyard Characteristics

Data was collected from a commercial vineyard property of Bodegas Terras Gauda, S.A., specifically a Vitis vinifera cv. Loureiro variety, located in Tomiño, Pontevedra, Galicia, Spain (X: −979,061.0, Y: 5,154,269.1; WGS84 Pseudo-Mercator, EPSG: 3857). This vineyard, spanning 1.06 hectares with an 8.1% slope, is part of the “Rias Baixas DO” (Designation of Origin). The vines, planted in 1990 with a northeast-southwest orientation, are trained in the Vertical Shoot Positioning (VSP) system. Vineyard management was conducted in accordance with DO protocol and applicable legislation. The vineyard exhibited phenological dynamics consistent with those observed in prior years, and spontaneous plant species were allowed to grow as cover crops between vine rows. The irrigation system installed in the vineyard operates with a dripper flow rate of 4 L per hour. The drippers are spaced 0.75 m apart along the irrigation lines. This configuration delivers an average application rate of 2.13 mm·h−1 over the planted area (4 L·h−1 emitters at 0.75 m spacing and 2.5 m row spacing).

2.5.2. UAV Data

Data Acquisition

The UAV data was collected on 14 July 2022, close to veraison, which is a critical period for managing irrigation and optimizing berry quality, as it coincides with the vineyard’s peak vegetative development and the cessation of growth [40,41]. The flight was conducted using a Zenmuse L1 sensor mounted on a DJI M300 RTK (Shenzhen, China), under clear sky conditions with some isolated clouds (0 to 1 Okta cloud cover). The Zenmuse L1 sensor, integrated with a 1-inch CMOS camera, Livox LiDAR module (Shenzhen, China), and high-accuracy IMU, operated at an altitude of 20 m and a speed of 4 m/s, with a side overlap of 50% and frontal overlap of 80% (Figure 3). More information can be found in the dataset [42].

Figure 3.

Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV) and sensor employed in the experiment. DJI M300 UAV with DJI Zenmuse L1 LiDAR. Adapted from [42].

Data Preprocessing

The raw RGB images gathered using the Zenmuse L1, were processed using DJI Terra software (Version 3.1.4). This software integrates information from the RGB camera to create high-precision 3D point clouds. To derive the Canopy Height Model (CHM) from the LiDAR data, the open-source software CloudCompare (v.2.12.4) with the Cloth Simulation Filter plugin was utilized. This plugin uses a cloth simulation algorithm to extract ground points by mimicking a cloth draping over the terrain. For this study, key parameters were configured: scene = relief, max iterations = 500, cloth resolution = 0.1 m, and cloth stiffness = 0.5. These settings enabled the effective separation of ground and vegetation points. The vegetation points were rasterized to create the Digital Surface Model (DSM), while the ground points were used to generate the Digital Terrain Model (DTM). The Canopy Height Model (CHM) was then computed by subtracting the DTM from the DSM.

Optimizing the CHM as Input

The CHM was used to reflect the vineyard canopy, identifying any height exceeding 0.5 m as vineyard vegetation. This approach was preferred over methods based on vegetation indices, such as the NDVI (Normalized Difference Vegetation Index) method, because of the presence of cover crops between rows, which could interfere with accurate vegetation masking. However, an NDVI approach could be implemented using other UAV data sources, such as multispectral imagery [43].

Then, the software used the CHM and the irrigation network in vector format as inputs.

3. Results

The values presented in this section correspond to an illustrative case study. In practical applications, the technician using the tool must adjust all parameters according to the specific conditions and requirements of the vineyard under analysis. The methodology is flexible and allows users to select appropriate values to ensure that the irrigation assessment is tailored to the unique characteristics of each plot.

3.1. Results (FAO-56, Without Geospatial Inputs)

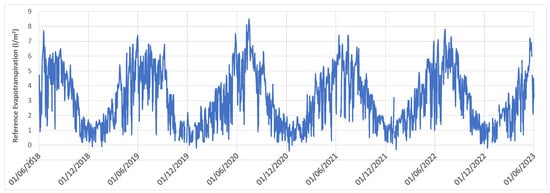

The following results were obtained using the FAO-56 method without geospatial inputs and relying on a user-estimated canopy cover (CC). To avoid underestimation, conservative values were selected for each parameter. The ET0 was set to 8.50 mm/day, the maximum recorded between 1 June 2018 and 1 June 2023 at the closest Meteogalicia station, As Eiras (Figure 4) (lat 41.9302, lon −8.7852, WGS84), located less than 2 km from the vineyard. Using this ET0 value and a crop coefficient (Kc) of 0.7, the calculated ETc was 5.95 mm/day. The Kc of 0.7 follows the FAO-56 Penman–Monteith recommendations for grapevines for wine production [12]; in fact, it is uncommon for Kc values in vineyards to exceed this threshold [44,45,46,47].

Figure 4.

Reference Evapotranspiration (ET0) recorded between 1 June 2018 and 1 June 2023 at the Meteogalicia station “As Eiras”. Note: Small negative ET0 values appear in the official MeteoGalicia dataset, probably due to measurement or calculation artifacts. These values have been plotted as provided by the official station and do not affect the interpretation of the seasonal ET0 patterns.

Regarding deficit irrigation strategies—commonly applied in vineyards with irrigation levels between 25% and 50% of ET0 [48,49]—this methodology adopts a more conservative approach. Specifically, 100% of ET0 was applied, representing the most unfavorable water-management scenario. This percentage can be expressed using the deficit irrigation factor (fDI), which ranges from 0 (full deficit) to 1 (no deficit). Here, fDI = 1.0 corresponds to full irrigation (100% of ET0). Additionally, Peff and AW (and thus RAW) were assumed to be 0.00 mm/day, representing conditions with no rainfall or soil moisture contributions during irrigation—an unfavorable scenario consistent with dry summer periods. Consequently, NIWR remained 5.95 mm/day.

The current irrigation system uses drippers with a discharge of 4.00 L/h spaced 0.75 m apart. In this study, the original spacing was retained; however, a detailed soil analysis could justify adjusting emitter spacing depending on soil type, as drip irrigation efficiency is strongly influenced by soil hydraulic characteristics and emitter discharge [50]. An effective irrigation width of 1.50 m was assumed, with irrigation applied once every seven days for 8.0 h per cycle. This schedule follows the vineyard’s standard management practice and was used as the operational baseline for ROR estimation. The resulting irrigation requirement for the weekly period was 41.65 mm.

Regarding the calculation of CC, it is important to note that evapotranspiration in woody crops is strongly correlated with canopy ground cover [51], and canopy expansion directly increases water demand [52]. The fraction of vegetation cover also affects the partitioning of evapotranspiration fluxes, with soil evaporation often dominating over transpiration during dry periods [53]. With drip irrigation, however, soil evaporation is largely confined to the wetted area beneath the canopy and does not occur uniformly across the bare soil surface [12]. Although Kc implicitly accounts for crop development and canopy cover, it only does so under conditions where the canopy fully covers the soil surface—an uncommon situation in woody crops. In most orchards, horizontal canopy projection rarely exceeds 60% of the ground area even at full development [54], as pruning and training practices are designed to facilitate mechanization and improve the distribution of solar radiation to fruiting branches [55]. Canopy cover (expressed as a percentage of ground area) is therefore a critical factor because Kc tends to scale with CC in woody crops [56,57,58].

The FAO document proposes the dual crop coefficient method for separating soil evaporation and plant transpiration [12]. However, it is not specifically designed for woody crops and requires parameters that users may find difficult to estimate reliably, such as the evaporation reduction coefficient (K_r), mean maximum plant height (h), and fraction of wetted soil (f_w). Omitting the dual Kc may cause slight overestimation of ETc when soil evaporation is significant, but because the objective of the DSS is to evaluate the hydraulic efficiency of the installed irrigation system—rather than to perform precise irrigation scheduling—the impact of this simplification on the ROR is minimal.

To preserve simplicity and remain focused on the objectives of this research—namely, calculating the ROR and generating the Irrigation Ecolabel—the canopy cover weighting method was applied, similar to its use in the AquaCrop model [59].

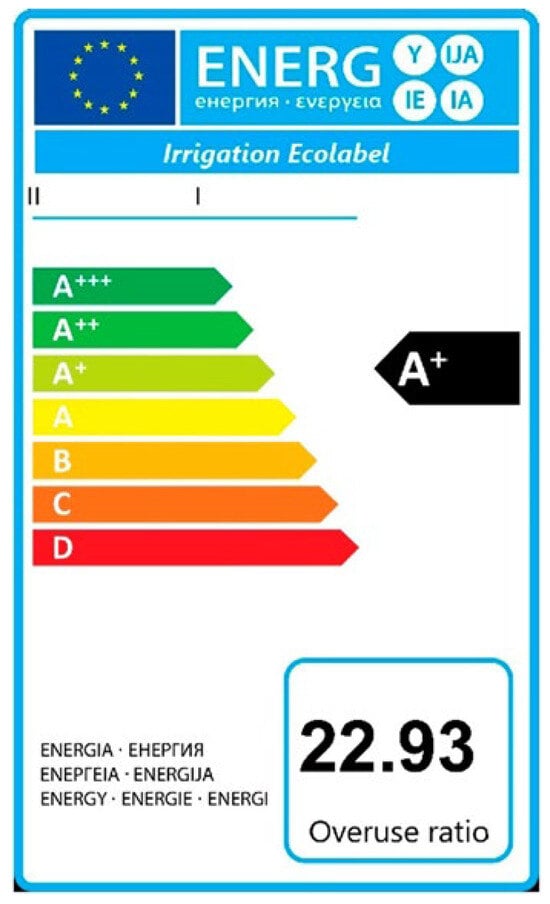

In the example, CC was estimated at 50%, representing a relatively unfavorable scenario. In fact, the actual CC could be even lower [44,45,60,61]. Based on this assumption, the NIWR adjusted per irrigation cycle was 20.82 L/(m2·7 days), while the NIWR adjusted per irrigation hour was 2.60 L/(h·m2). The GIWR during the 8-h irrigation event was 2.89 L/(h·m2), resulting in a theoretical dripper discharge of 3.25 L/h, which could reasonably be rounded to 4.00 L/h for commercial purposes.

Given that the actual dripper discharge is 4.00 L/h, the resulting ROR was 22.93%. This indicates that the installed system is dimensioned to deliver 22.93% more discharge than the theoretical requirement—implying proportional excesses in energy use and materials (polyethylene, metals, etc.). This level of overuse corresponds to an A+ rating in the Irrigation Ecolabel (Figure 5), which still represents an excellent efficiency level. Although it is not the maximum rating (A+++), the A+ classification reflects efficient operation, far from the lower categories (C or D) associated with substantial resource overuse.

Figure 5.

Illustrative mockup of the proposed Irrigation Ecolabel, inspired by the European Union (EU) energy efficiency labels [32]. Label generated without geospatial inputs.

An A+ rating therefore demonstrates robust resource management and situates the vineyard within the high-efficiency range. The difference between A+++ and A+ is marginal compared with the inefficiencies represented by lower categories. Thus, although some room for improvement exists, the vineyard is already performing at an efficiency level that is far from problematic.

3.2. Results Including Geospatial Inputs (UAV-Derived Canopy Data)

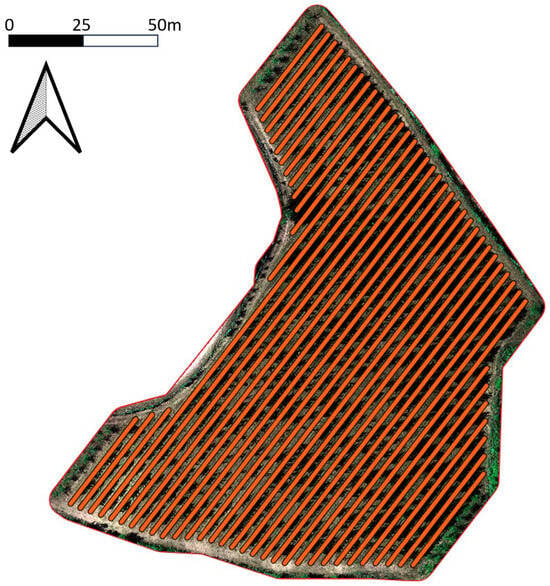

In this section, geospatial In this section, geospatial information and UAV-derived canopy data (Figure 6) are incorporated to refine canopy cover (CC) estimation and update the hydraulic oversizing calculations. Unlike the previous example—where CC was assumed to be 50%—the use of UAV data allows the software to compute CC more accurately, thereby refining the estimation of theoretical discharge required for ROR computation.

Figure 6.

Irrigation network layout overlaid (orange) on a UAV-derived orthomosaic.

Using the same parameters from the previous example, the study assumes an ET0 of 8.50 mm/day, a crop coefficient (Kc) of 0.7, and a deficit irrigation level of 100% of ET0. Peff is considered to be 0.00 mm/day, and AW is also set to 0.00 mm/day. The irrigation system operates with drippers delivering 4.00 L/h, spaced 0.75 m apart, over an effective irrigation width of 1.50 m. Irrigation is applied once every seven days, with each event lasting 8.0 h.

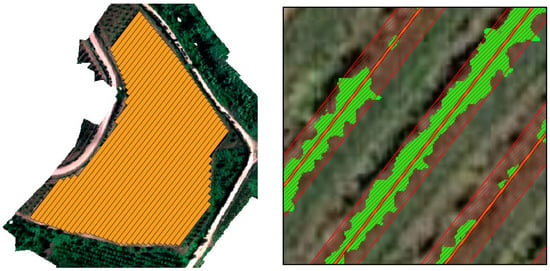

In this specific case, the CC is calculated using GIS-based processing. The left panel of Figure 7 shows the influence area associated with each pipeline, generated based on the user-defined “irrigation width.” This enables the calculation of an average CC factor for the entire vineyard, as well as individual CC values for each row (Figure 7, right).

Figure 7.

(left) Influence area of each dripper (buffer). (right) Overlap between CHM (green), irrigation buffer (red) and irrigation network layout overlaid (orange).

These inputs allow for recalculation of the net water demand and subsequent theoretical discharge calculation. The resulting value was 8.43 L/(m2·week), and 1.05 L/(h·m2) per irrigation hour. Considering a drip irrigation efficiency of Ea = 0.9 [33], the gross water demand was adjusted to 1.17 L/(h·m2) over the 8-h irrigation period to ensure efficient water distribution.

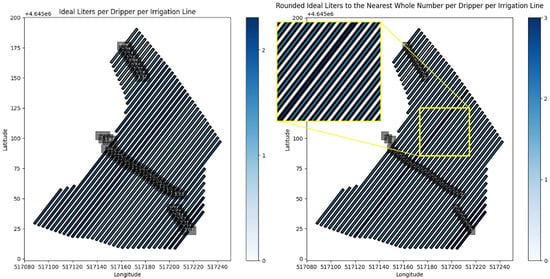

Using this information, the theoretical discharge per dripper was determined to be 1.32 L/h, which can be rounded to 2.00 L/h for commercial implementation. This method enables the calculation of the theoretical flow rate for every row (Figure 8, left), as well as the commercially available dripper size that would be most appropriate for each row (Figure 8, right).

Figure 8.

(left) Actual water flow (L/h) per dripper per irrigation row. (right) Map showing normalized dripper flowrate per row.

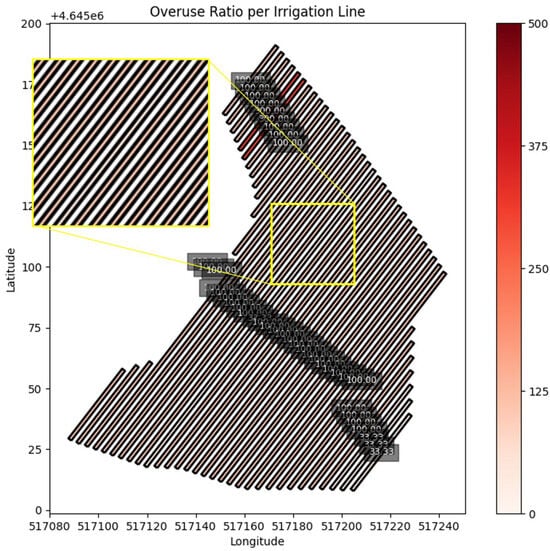

Based on these values, the system can calculate the Resource Overutilization Ratio (ROR) for each individual irrigation row (Figure 9). The ROR serves as a direct indicator of resource efficiency, with values closer to 0% representing optimal performance. This level of spatially detailed analysis enables detailed identification of spatial hydraulic oversizing patterns.

Figure 9.

Resource overutilization ratio (ROR) per row.

In this case, UAV-derived CC values were substantially lower than those assumed in the previous example, strongly affecting the results. With an installed dripper discharge of 4.00 L h−1, the ROR increased to 203.69%, indicating that the system is dimensioned to deliver more than triple the theoretical water requirement under the evaluated conditions. Such oversizing implies a proportional increase in material use and energy demand associated with the installed infrastructure. This level of discharge mismatch corresponds to a D rating in the Irrigation Ecolabel (Figure 10), reflecting severe hydraulic oversizing according to the proposed diagnostic framework.

Figure 10.

Illustrative mockup of the proposed Irrigation Ecolabel, inspired by the European Union (EU) energy efficiency labels [32]. Label generated using geospatial inputs (UAV-derived data).

A D rating reflects severe overutilization of resources and demonstrates that the system is far from optimized. In contrast to higher categories such as A++ or A+++, which indicate highly efficient management, a D classification highlights the need for significant corrective actions. The results imply that the installed discharge capacity exceeds the theoretical requirement by more than a factor of three, underscoring an urgent need for improvements to reduce waste. Addressing these inefficiencies is essential for progressing toward higher efficiency categories—such as A or B—which represent more sustainable irrigation practices.

3.3. Report Results

Finally, the software automatically generates a PDF report summarizing all calculations and outputs produced during the workflow. The report includes the computed ET0 and ETc values, net and gross irrigation water requirements, irrigation system parameters, the theoretical and actual dripper flow rates, the resulting Resource Overutilization Ratio (ROR), and the corresponding Irrigation Ecolabel.

When geospatial inputs are not used, the report presents only numerical results—meteorological data, agronomic parameters, irrigation system characteristics, and the final ROR and ecolabel—typically resulting in a document of approximately five pages.

When UAV-derived canopy data are included, the report additionally incorporates the geospatial layers generated by the DSS (Ideal/Theoretical Liters per Dripper, Rounded Liters per Dripper, and ROR maps), increasing the length to about ten pages. These spatial outputs enable users to identify variability across the field and highlight driplines or zones where the installed system delivers more or less water than required.

Additional details are explained in the Supplementary Material Text S2.

4. Discussion

The Irrigation Ecolabel obtained in the case study varies markedly depending on the method used to estimate canopy cover and theoretical discharge: A+ when relying solely on the FAO-56 approach (Figure 5) and D when incorporating UAV-derived canopy data (Figure 10), based on ROR values of 22.93% and 203.69%, respectively. This substantial discrepancy highlights the strong influence that input data quality—and specifically canopy cover estimation—can have on the resulting ROR. Although the DSS can operate without geospatial inputs, UAV-based canopy measurements are strongly recommended whenever available, as they greatly reduce the subjectivity inherent in manually estimating canopy cover. Nonetheless, the non-UAV workflow remains useful, especially in orchards where canopy cover is relatively uniform or stable and can be estimated reliably by a trained technician. In contrast, UAV-derived inputs are preferable when intra-field variability is suspected, when canopy development is uncertain, or when a row-level hydraulic diagnostic is required.

Prior to any large-scale adoption, it will be important to establish clear operational rules and standards to ensure that ROR calculations are performed consistently and are not subject to individual interpretation. The choice of methodology should be made by trained technical personnel—such as agricultural engineers—because different approaches can yield significantly different outcomes, which in turn influence the final Irrigation Ecolabel classification.

It should also be noted that the ROR reported in this study was computed using a constant ET0 equal to the maximum observed value. In real-world applications, ET0 fluctuates considerably, especially during summer. Using daily ET0 over a representative period would modify the theoretical water requirement and therefore the resulting ROR, potentially leading to a lower or higher ecolabel rating depending on the distribution of climatic demand. Incorporating temporal variability into future DSS implementations would allow the tool to capture how the hydraulic adequacy of the installed system behaves under changing climatic conditions, providing a more realistic representation of system performance throughout the season.

Importantly, the ROR should not be confused with water-use efficiency (WUE) or water footprint indicators. While WUE and water footprint relate water use to yield or environmental impact, the ROR strictly evaluates the hydraulic performance of the irrigation system by comparing actual emitter discharge with the theoretical design discharge. It is therefore a structural metric, not a productivity metric, and should be interpreted as complementary to—but distinct from—agronomic indicators.

The large differences in ROR values between the FAO-based and UAV-based methods should not be seen as evidence of increased subjectivity. On the contrary, the UAV approach reduces user bias: whereas FAO-based workflows require users to estimate CC manually, UAV-derived CC replaces subjective judgment with spatially explicit measurements. This increases objectivity and more accurately reflects actual field conditions, revealing inefficiencies that conventional estimation methods may overlook. Given that the hydraulic performance of installed systems changes over time with crop development, climatic conditions, and system aging, both the ROR and the Irrigation Ecolabel should be reassessed periodically. Annual evaluation—preferably during peak evapotranspiration—would enable meaningful year-to-year comparisons and ensure that the ecolabel reflects the current state of the irrigation system rather than a one-time assessment.

Several studies have documented significant over-irrigation in Mediterranean and woody cropping systems. Santos et al. [38] reported an average over-irrigation ratio of 1.27 in southern Spain, mainly attributed to inadequate scheduling and limited adoption of monitoring tools. Salvador et al. [37] observed generalized over-irrigation across 102 Spanish farms, with applied volumes systematically exceeding net requirements. These findings reinforce the relevance of the ROR as a diagnostic tool. However, the Irrigation Ecolabel reflects only the hydraulic performance of the system; agronomic strategies such as deficit irrigation may influence interpretation. Under deficit irrigation, a low ROR does not necessarily indicate inefficiency but may instead reflect a deliberate management strategy aimed at optimizing crop performance. Thus, the ROR must always be interpreted in the context of the irrigation strategy used. As shown in this study, the FAO-based method produced an A++-type result, whereas the UAV-based method led to a D rating, underscoring the need to consider which method is used when calculating the ecolabel. While this study used two specific approaches, many others could also be incorporated [62].

Another important aspect is the treatment of canopy cover. For simplicity—and because developing new CC estimation methods was not an objective of this study—CC was used as a weighting factor and calculated both as an average and at the row level. However, CC could be derived using alternative approaches such as density coefficients (K_d) [63] or relationships between CC and Kc [57,58]. With recent advances in UAV technology, new methods are emerging for calculating CC and related metrics such as LAI [64], tree canopy structure [65,66,67] or planar area [68]. The DSS has therefore been designed to remain flexible so that future versions can incorporate more sophisticated canopy metrics. UAV technology offers substantial advantages in detecting spatial variability, enabling high-resolution computation of the ROR at row or sub-row scales—far beyond what is possible with traditional methods. Similar benefits have been demonstrated in other studies: Rozenstein et al. [69] compared UAV-based and ANN-based methods for estimating irrigation doses in tomato crops, finding that both approaches produced accurate ET and irrigation estimates, aligning closely with expert guidelines. Additionally, GIS-based platforms such as Agrisat (Spain) provide daily Kc estimates from NDVI, offering a practical solution for large-scale applications.

The vineyard use case in this study applied a conservative Kc of 0.7, consistent with FAO-56 recommendations [12,61] and with values commonly reported in the literature [22,70]. The DSS requires user-provided inputs, and its accuracy depends on the quality of those inputs, particularly the estimation of crop water needs (ETc, Kc) and the description of the irrigation network. Errors in Kc propagate into ETc and theoretical discharge, thereby affecting the ROR. However, typical Kc sources—FAO tables, regional guidelines, or satellite/UAV products—are usually adequate for diagnostic purposes, since the ecolabel evaluates hydraulic performance rather than scheduling decisions. Moderate uncertainty in Kc tends to influence the magnitude but not the qualitative class of the ecolabel. Users may further reduce uncertainty by applying locally calibrated Kc or UAV-derived canopy data.

The accuracy of the ROR also depends on how precisely the irrigation network is represented in the DSS, including emitter spacing, flow rate, irrigation interval, and actual operating hours. Reliable system characterization ensures an accurate comparison between theoretical and actual discharge.

From a practical standpoint, drippers are commercially available only at discrete flow rates (e.g., 2, 3, or 4 L·h−1). Although the DSS calculates theoretical discharge as a continuous value for analytical precision, such exact values cannot always be implemented in practice. Designers should therefore select the closest available emitter size when upgrading systems. This does not affect the ROR computation, which remains based on the theoretical discharge, but it may influence practical installation choices.

Finally, the Irrigation Ecolabel classes (A–D) are currently proposed as a conceptual communication tool, inspired by EU energy labels and informed by ranges reported in the overirrigation literature. These thresholds have not yet been empirically calibrated across crops or environmental conditions and should be regarded as provisional. Developing official certification standards or validation protocols would require further research and coordinated efforts among regulatory bodies, irrigation manufacturers, and agricultural certification agencies. The methodology presented here provides a transparent and reproducible foundation for such future standardization. The ecolabel is therefore intended as a flexible diagnostic and benchmarking tool that may later be formalized within regulatory frameworks.

Limitations of the Methodology and Future Enhancements

This study presents several limitations that should be addressed in future research. First, the methodology was developed primarily for woody crops under drip irrigation, which may limit its applicability to other crop types or irrigation systems. Expanding the DSS to encompass a wider range of crops, climates, and irrigation infrastructures will be necessary for broader generalization. Although UAV data were incorporated, the current framework does not fully exploit more advanced technologies such as machine learning, real-time sensors, or 3D canopy reconstruction, which could substantially enhance spatial and temporal precision. For example, CC could be derived from density coefficients or advanced 3D metrics, but developing such techniques was beyond the scope of this study.

The approach relies on the FAO-56 method, chosen for its simplicity and widespread use. Although alternative models such as AquaCrop or METRIC may offer more detailed evapotranspiration estimates, they require numerous parameters—soil hydraulic properties, detailed crop development, or extensive meteorological inputs—that are often unavailable to farmers and impractical for routine use. Thus, these models are mentioned as potential future extensions rather than feasible options for the current operational version of the DSS.

In this study, the crop coefficient was adjusted using a simplified approach (Kc_adj = Kc_FAO × CC), which may partially overcorrect evapotranspiration because FAO-56 Kc values already embed canopy development. This simplification was intentionally adopted to keep the method focused on the ROR and the Irrigation Ecolabel. Moreover, the FAO-56 workflow was intentionally computed under a worst-case scenario—maximum ET0, zero soil water storage (RAW = 0), and zero effective rainfall—to clearly illustrate the contrast between FAO-based and UAV-based results. In practice, moderate assumptions (seasonal average ET0, non-zero soil moisture, or effective rainfall) would produce narrower differences. Future DSS versions should allow the user to simulate realistic soil and climate conditions.

Regarding the Irrigation Ecolabel, the proposed thresholds are conceptual and should be empirically calibrated using multi-year datasets, multiple crops, and diverse climates. The current implementation is optimized for small-scale systems, and future developments should define aggregation rules for multi-zone or large-scale irrigation networks to ensure consistent ecolabel assignment.

Lastly, although the current formulation focuses solely on hydraulic performance, future extensions of the DSS could incorporate agronomic elements—such as crop-specific water stress thresholds, phenological sensitivities, or indicators of sustained deficit responses—to broaden the diagnostic scope. This would allow the system to contextualize hydraulic oversizing within crop-level water needs without moving into full crop growth or yield modelling.

5. Conclusions

This study presents a standardized and transparent framework for diagnosing irrigation overutilization through a decision-support system (DSS) that computes the Resource Overutilization Ratio (ROR) and the associated Irrigation Ecolabel. By combining FAO-56 crop-water calculations with optional UAV-derived canopy data, the DSS identifies where the installed irrigation network is oversized relative to crop water requirements, producing spatial diagnostics of hydraulic adequacy rather than maps of actual water distribution.

The approach is particularly useful for irrigation systems designed from coarse assumptions about crop water needs, where emitter discharge is fixed and irrigation is adjusted only through application time. Such conditions often lead to chronic oversizing. The DSS quantifies these mismatches—such as irrigating before full canopy development or using emitters with unnecessarily high nominal discharge—thereby supporting improvements in hydraulic adequacy and reducing unnecessary water, energy, and material use.

Application of the method in a commercial vineyard demonstrated its practical implementation and suitability for drip irrigation in woody crops. Although illustrated in a single crop, the framework is adaptable to other perennial drip-irrigated systems. The Irrigation Ecolabel serves as a diagnostic and benchmarking tool—not an irrigation scheduler—providing a consistent way to compare hydraulic performance under comparable input assumptions. A major finding is the importance of spatially explicit canopy measurements (for example, using UAV data), which can uncover oversizing that remains hidden when canopy cover is user-estimated.

The ROR proved effective for isolating the hydraulic dimension of irrigation performance, enabling diagnostics at high spatial resolution and facilitating comparisons across seasons or fields. Because system adequacy evolves with canopy development, climate, and ageing, the ecolabel should be recalculated periodically, ideally once per year during peak evaporative demand. Future work should include multi-season and multi-crop validations, empirical calibration of ecolabel thresholds, and integration of complementary data sources such as real-time sensors, satellite-based ET, or machine-learning canopy metrics to broaden robustness and applicability.

Disclaimer: This study introduces a new methodological framework designed to diagnose hydraulic oversizing in drip-irrigated crops. As this is the first application of the proposed approach, some parameters and assumptions were necessarily simplified or estimated due to the exploratory nature of the method and data availability. While the procedures followed were rigorous, the resulting values should be interpreted within the context of this methodological development. Consequently, the findings do not represent the exact conditions of the case-study vineyard, and any practical application of the methodology should be supported by site-specific verification and technical assessment.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/agriengineering7120429/s1, Figure S1: Report generated by the software. A 5-page report is produced when no geospatial inputs are provided; Figure S2: Report generated by the software. A 10-page report is generated if geospatial inputs are included, incorporating both intermediate and final GIS outputs.

Author Contributions

S.V. Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Validation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Resources, Data Curation, Writing—Original Draft, Writing—Review & Editing, Visualization, Supervision, Project administration, Funding acquisition. R.M.-P. Validation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Data Curation, Writing—Review & Editing, Visualization. M.A.-S. Validation, Formal analysis, Resources, Data Curation, Writing—Review & Editing. J.V. Validation, Writing—Review & Editing, Supervision, Project administration, Funding acquisition. I.S. Data curation, Visualization, Writing—Review & Editing. M.Á.P. Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Data Curation, Writing—Original Draft, Writing—Review & Editing, Visualization, Supervision, Project administration, Funding acquisition. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work has been carried out in the scope of the H2020 FlexiGroBots project, which has been funded by the European Commission in the scope of its H2020 program (contract number 101017111, https://flexigrobots-h2020.eu/ (accessed on 26 September 2025)).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets can be found at [42,43]. The open-source software can be found at https://github.com/druzzo/IrrigationEcolabel (accessed on 26 September 2025). The video tutorial can be found at https://github.com/druzzo/IrrigationEcolabel?tab=readme-ov-file#video-tutorial (accessed on 26 September 2025).

Acknowledgments

Sergio Vélez’s holds a Distinguished Researcher contract (Beatriz Galindo BG23/00073), funded by the Spanish Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities under the 2023 call, within the framework of the State Plan for Scientific, Technical, and Innovation Research (PEICTI) 2021–2023. Miguel Ángel Pardo’s work was supported by the research project “HIDREN” through the 2023 call Estancias de profesores e investigadores senior en centros extranjeros (PRX23/00582). We would like to thank the support of COST Action (European Cooperation in Science and Technology): FruitCREWS, CA21142. The authors acknowledge valuable help and contributions from ‘Bodegas Terras Gauda, S.A.’, particularly the valuable technical feedback of Emilio Rodríguez Cañas (Terras Gauda S.L.). The contribution of Igor Sirnik was partially supported within the framework of the research programme P2-0406: Opazovanje Zemlje in geoinformatika, which is funded by the Javna agencija za znanstvenoraziskovalno in inovacijsko dejavnost Republike Slovenije from the state budget of the Republic of Slovenia. During the preparation of this manuscript/study, the authors used OpenAI’s ChatGPT5 for the purposes of revision of the English language and image generation for the PDF report. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Duarte, R.; Pinilla, V.; Serrano, A. The Water Footprint of the Spanish Agricultural Sector: 1860–2010. Ecol. Econ. 2014, 108, 200–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Núñez, M.; Pfister, S.; Antón, A.; Muñoz, P.; Hellweg, S.; Koehler, A.; Rieradevall, J. Assessing the Environmental Impact of Water Consumption by Energy Crops Grown in Spain. J. Ind. Ecol. 2013, 17, 90–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, R.; Pinilla, V.; Serrano, A. The Globalization of Mediterranean Agriculture: A Long-Term View of the Impact on Water Consumption. Ecol. Econ. 2021, 183, 106964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thevs, N.; Nurtazin, S.; Beckmann, V.; Salmyrzauli, R.; Khalil, A. Water Consumption of Agriculture and Natural Ecosystems along the Ili River in China and Kazakhstan. Water 2017, 9, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salazar, O.; Chinchilla-Soto, C.; de los Santos-Villalobos, S.; Ayala, M.; Benavides, L.; Berriel, V.; Cardoso, R.; Chavarrí, E.; Anjos, R.; González, A.; et al. Water Consumption by Agriculture in Latin America and the Caribbean: Impact of Climate Change and Applications of Nuclear and Isotopic Techniques. Int. J. Agric. Nat. Resour. 2022, 49, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Y.; Khan, S.; Ma, X. Climate Change Impacts on Crop Yield, Crop Water Productivity and Food Security—A Review. Prog. Nat. Sci. 2009, 19, 1665–1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masia, S.; Trabucco, A.; Spano, D.; Snyder, R.L.; Sušnik, J.; Marras, S. A Modelling Platform for Climate Change Impact on Local and Regional Crop Water Requirements. Agric. Water Manag. 2021, 255, 107005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Liu, B.; Piao, S.; Wang, X.; Lobell, D.B.; Huang, Y.; Huang, M.; Yao, Y.; Bassu, S.; Ciais, P.; et al. Temperature Increase Reduces Global Yields of Major Crops in Four Independent Estimates. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 9326–9331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Climate Change 2021—The Physical Science Basis: Working Group I Contribution to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, 1st ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2023; ISBN 978-1-009-15789-6. [Google Scholar]

- Pereira, L.S.; Allen, R.G.; Smith, M.; Raes, D. Crop Evapotranspiration Estimation with FAO56: Past and Future. Agric. Water Manag. 2015, 147, 4–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, A.; Friedel, J.K.; Bodner, G. Improving Water Use Efficiency for Sustainable Agriculture. In Agroecology and Strategies for Climate Change; Lichtfouse, E., Ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2012; pp. 167–211. ISBN 978-94-007-1904-0. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, R.G.; Pereira, L.S.; Raes, D.; Smith, M. Crop Evapotranspiration: Guidelines for Computing Crop Water Requirements; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 1998; ISBN 92-5-104219-5. [Google Scholar]

- Widmoser, P. A Discussion on and Alternative to the Penman–Monteith Equation. Agric. Water Manag. 2009, 96, 711–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duce, P.; Snyder, R.L.; Spano, D. Forecasting reference evapotranspiration. Acta Hortic. 2000, 537, 135–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vivaldi, G.A.; Camposeo, S.; Romero-Trigueros, C.; Pedrero, F.; Caponio, G.; Lopriore, G.; Álvarez, S. Physiological Responses of Almond Trees under Regulated Deficit Irrigation Using Saline and Desalinated Reclaimed Water. Agric. Water Manag. 2021, 258, 107172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellvert, J.; Mata, M.; Vallverdú, X.; Paris, C.; Marsal, J. Optimizing Precision Irrigation of a Vineyard to Improve Water Use Efficiency and Profitability by Using a Decision-Oriented Vine Water Consumption Model. Precis. Agric. 2021, 22, 319–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abioye, A.E.; Abidin, M.S.Z.; Mahmud, M.S.A.; Buyamin, S.; Mohammed, O.O.; Otuoze, A.O.; Oleolo, I.O.; Mayowa, A. Model Based Predictive Control Strategy for Water Saving Drip Irrigation. Smart Agric. Technol. 2023, 4, 100179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, L.; Parra, L.; Jimenez, J.M.; Lloret, J.; Lorenz, P. IoT-Based Smart Irrigation Systems: An Overview on the Recent Trends on Sensors and IoT Systems for Irrigation in Precision Agriculture. Sensors 2020, 20, 1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rallo, G.; González-Altozano, P.; Manzano-Juárez, J.; Provenzano, G. Using Field Measurements and FAO-56 Model to Assess the Eco-Physiological Response of Citrus Orchards under Regulated Deficit Irrigation. Agric. Water Manag. 2017, 180, 136–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero, P.; Navarro, J.M.; Ordaz, P.B. Towards a Sustainable Viticulture: The Combination of Deficit Irrigation Strategies and Agroecological Practices in Mediterranean Vineyards. A Review and Update. Agric. Water Manag. 2022, 259, 107216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elfarkh, J.; Johansen, K.; El Hajj, M.M.; Almashharawi, S.K.; McCabe, M.F. Evapotranspiration, Gross Primary Productivity and Water Use Efficiency over a High-Density Olive Orchard Using Ground and Satellite Based Data. Agric. Water Manag. 2023, 287, 108423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, L.E. Determination of Evapotranspiration and Crop Coefficients for a Chardonnay Vineyard Located in a Cool Climate. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 2014, 65, 159–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capraro, F.; Tosetti, S.; Rossomando, F.; Mut, V.; Vita Serman, F. Web-Based System for the Remote Monitoring and Management of Precision Irrigation: A Case Study in an Arid Region of Argentina. Sensors 2018, 18, 3847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carraro, E.; Di Iorio, A. Eligible Strategies of Drought Response to Improve Drought Resistance in Woody Crops: A Mini-Review. Plant Biotechnol. Rep. 2022, 16, 265–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cisternas, I.; Velásquez, I.; Caro, A.; Rodríguez, A. Systematic Literature Review of Implementations of Precision Agriculture. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2020, 176, 105626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariza-Sentís, M.; Vélez, S.; Valente, J. BBR: An Open-Source Standard Workflow Based on Biophysical Crop Parameters for Automatic Botrytis cinerea Assessment in Vineyards. SoftwareX 2023, 24, 101542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Gennaro, S.F.; Vannini, G.L.; Berton, A.; Dainelli, R.; Toscano, P.; Matese, A. Missing Plant Detection in Vineyards Using UAV Angled RGB Imagery Acquired in Dormant Period. Drones 2023, 7, 349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furlanetto, J.; Dal Ferro, N.; Longo, M.; Sartori, L.; Polese, R.; Caceffo, D.; Nicoli, L.; Morari, F. LAI Estimation through Remotely Sensed NDVI Following Hail Defoliation in Maize (Zea mays L.) Using Sentinel-2 and UAV Imagery. Precis. Agric. 2023, 24, 1355–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vélez, S.; Ariza-Sentís, M.; Panić, M.; Ivošević, B.; Stefanović, D.; Kaivosoja, J.; Valente, J. Speeding up UAV-Based Crop Variability Assessment through a Data Fusion Approach Using Spatial Interpolation for Site-Specific Management. Smart Agric. Technol. 2024, 8, 100488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boursianis, A.D.; Papadopoulou, M.S.; Diamantoulakis, P.; Liopa-Tsakalidi, A.; Barouchas, P.; Salahas, G.; Karagiannidis, G.; Wan, S.; Goudos, S.K. Internet of Things (IoT) and Agricultural Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) in Smart Farming: A Comprehensive Review. Internet Things 2022, 18, 100187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nydrioti, I.; Grigoropoulou, H. Using the Water Footprint Concept for Water Use Efficiency Labelling of Consumer Products: The Greek Experience. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 30, 19918–19930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission Ecodesign and Energy Label. Available online: https://energy-efficient-products.ec.europa.eu/ecodesign-and-energy-label_en (accessed on 26 September 2025).

- Ministerio de Agricultura. Estimación de La Demanda de Agua de Los Cultivos; Ministerio de Agricultura: Santiago, Chile, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Regulation (EU) 2017/1369 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 4 July 2017. 2017. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2017/1369/oj/eng (accessed on 26 September 2025).

- Islam, M.S.; Tumpa, S.; Afrin, S.; Ahsan, M.N.; Haider, M.Z.; Das, D.K. From over to Optimal Irrigation in Paddy Production: What Determines over-Irrigation in Bangladesh? Sustain. Water Resour. Manag. 2021, 7, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, J.; Feng, J.; Liu, S.; Jia, S.; Fan, F. A Simple Method for Drip Irrigation Scheduling of Spinach (Spinacia oleracea L.) in a Plastic Greenhouse in the North China Plain Using a 20 cm Standard Pan Outside the Greenhouse. Horticulturae 2023, 9, 706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvador, R.; Bautista-Capetillo, C.; Playán, E. Irrigation Performance in Private Urban Landscapes: A Study Case in Zaragoza (Spain). Landsc. Urban Plan. 2011, 100, 302–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, C.; Lorite, I.J.; Tasumi, M.; Allen, R.G.; Fereres, E. Performance Assessment of an Irrigation Scheme Using Indicators Determined with Remote Sensing Techniques. Irrig. Sci. 2010, 28, 461–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segovia-Cardozo, D.A.; Rodríguez-Sinobas, L.; Zubelzu, S. Water Use Efficiency of Corn among the Irrigation Districts across the Duero River Basin (Spain): Estimation of Local Crop Coefficients by Satellite Images. Agric. Water Manag. 2019, 212, 241–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baeza, P.; Junquera, P.; Peiro, E.; Ramón Lissarrague, J.; Uriarte, D.; Vilanova, M. Effects of Vine Water Status on Yield Components, Vegetative Response and Must and Wine Composition. In Advances in Grape and Wine Biotechnology; Morata, A., Loira, I., Eds.; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2019; ISBN 978-1-78984-612-6. [Google Scholar]

- Caruso, G.; Palai, G.; Gucci, R.; D’Onofrio, C. The Effect of Regulated Deficit Irrigation on Growth, Yield, and Berry Quality of Grapevines (Cv. Sangiovese) Grafted on Rootstocks with Different Resistance to Water Deficit. Irrig. Sci. 2023, 41, 453–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vélez, S.; Ariza-Sentís, M.; Valente, J. VineLiDAR: High-Resolution UAV-LiDAR Vineyard Dataset Acquired over Two Years in Northern Spain. Data Brief 2023, 51, 109686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vélez, S.; Ariza-Sentís, M.; Valente, J. Dataset on Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Multispectral Images Acquired over a Vineyard Affected by Botrytis Cinerea in Northern Spain. Data Brief 2023, 46, 108876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, I.; Neale, C.M.U.; Calera, A.; Balbontín, C.; González-Piqueras, J. Assessing Satellite-Based Basal Crop Coefficients for Irrigated Grapes (Vitis vinifera L.). Agric. Water Manag. 2010, 98, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, M.I.; Silvestre, J.; Conceição, N.; Malheiro, A.C. Crop and Stress Coefficients in Rainfed and Deficit Irrigation Vineyards Using Sap Flow Techniques. Irrig. Sci. 2012, 30, 433–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cancela, J.J.; Fandiño, M.; Rey, B.J.; Martínez, E.M. Automatic Irrigation System Based on Dual Crop Coefficient, Soil and Plant Water Status for Vitis vinifera (Cv. Godello and Cv. Mencía). Agric. Water Manag. 2015, 151, 52–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortuani, B.; Facchi, A.; Mayer, A.; Bianchi, D.; Bianchi, A.; Brancadoro, L. Assessing the Effectiveness of Variable-Rate Drip Irrigation on Water Use Efficiency in a Vineyard in Northern Italy. Water 2019, 11, 1964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteban-Sanchez, G.; Campillo, C.; Uriarte, D.; Moral, F.J. Technical Feasibility Analysis of Advanced Monitoring with a Thermal Camera on an Unmanned Aerial Vehicle and Pressure Chamber for Water Status in Vineyards. Horticulturae 2024, 10, 305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilanova, M.; Rodríguez-Nogales, J.M.; Vila-Crespo, J.; Yuste, J. Influence of Water Regime on Yield Components, Must Composition and Wine Volatile Compounds of Vitis Vinifera Cv. Verdejo: Influence of Water Regime on Verdejo Grapes and Wine. Aust. J. Grape Wine Res. 2019, 25, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cote, C.M.; Bristow, K.L.; Charlesworth, P.B.; Cook, F.J.; Thorburn, P.J. Analysis of Soil Wetting and Solute Transport in Subsurface Trickle Irrigation. Irrig. Sci. 2003, 22, 143–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drechsler, K.; Fulton, A.; Kisekka, I. Crop Coefficients and Water Use of Young Almond Orchards. Irrig. Sci. 2022, 40, 379–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espadafor, M.; Orgaz, F.; Testi, L.; Lorite, I.J.; Villalobos, F.J. Transpiration of Young Almond Trees in Relation to Intercepted Radiation. Irrig. Sci. 2015, 33, 265–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chebbi, W.; Boulet, G.; Le Dantec, V.; Lili Chabaane, Z.; Fanise, P.; Mougenot, B.; Ayari, H. Analysis of Evapotranspiration Components of a Rainfed Olive Orchard during Three Contrasting Years in a Semi-Arid Climate. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2018, 256, 159–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villalobos, F.J.; Fereres, E. (Eds.) Principles of Agronomy for Sustainable Agriculture; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; ISBN 978-3-319-46115-1. [Google Scholar]

- Fereres, E.; Goldhamer, D.A.; Sadras, V.O. Yield Response to Water of Fruit Trees and Vines: Guidelines. In Crop Yield Response to Water; FAO Irrigation and Drainage; FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations): Rome, Italy, 2012; Volume 33, p. 246. ISBN 978-92-5-105980-7. [Google Scholar]

- Picón-Toro, J.; González-Dugo, V.; Uriarte, D.; Mancha, L.A.; Testi, L. Effects of Canopy Size and Water Stress over the Crop Coefficient of a “Tempranillo” Vineyard in South-Western Spain. Irrig. Sci. 2012, 30, 419–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testi, L.; Villalobos, F.J.; Orgaz, F. Evapotranspiration of a Young Irrigated Olive Orchard in Southern Spain. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2004, 121, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villalobos, F.J.; Testi, L.; Moreno-Perez, M.F. Evaporation and Canopy Conductance of Citrus Orchards. Agric. Water Manag. 2009, 96, 565–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steduto, P.; Hsiao, T.C.; Raes, D.; Fereres, E. AquaCrop—The FAO Crop Model to Simulate Yield Response to Water: I. Concepts and Underlying Principles. Agron. J. 2009, 101, 426–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yunusa, I.A.M.; Walker, R.R.; Lu, P. Evapotranspiration Components from Energy Balance, Sapflow and Microlysimetry Techniques for an Irrigated Vineyard in Inland Australia. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2004, 127, 93–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, L.E.; Levin, A.D.; Fidelibus, M.W. Crop Coefficients (Kc) Developed from Canopy Shaded Area in California Vineyards. Agric. Water Manag. 2022, 271, 107771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, G.; Han, W.; Zhang, H.; Liu, S.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Cui, X. Mapping Maize Crop Coefficient Kc Using Random Forest Algorithm Based on Leaf Area Index and UAV-Based Multispectral Vegetation Indices. Agric. Water Manag. 2021, 252, 106906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, R.G.; Pereira, L.S. Estimating Crop Coefficients from Fraction of Ground Cover and Height. Irrig. Sci. 2009, 28, 17–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comba, L.; Biglia, A.; Ricauda Aimonino, D.; Tortia, C.; Mania, E.; Guidoni, S.; Gay, P. Leaf Area Index Evaluation in Vineyards Using 3D Point Clouds from UAV Imagery. Precis. Agric. 2020, 21, 881–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantürk, M.; Zabawa, L.; Pavlic, D.; Dreier, A.; Klingbeil, L.; Kuhlmann, H. UAV-Based Individual Plant Detection and Geometric Parameter Extraction in Vineyards. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1244384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, J.; De Bei, R.; Fuentes, S.; Collins, C. UAV and Ground-Based Imagery Analysis Detects Canopy Structure Changes after Canopy Management Applications. OENO One 2020, 54, 1093–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Sánchez, J.; De Castro, A.I.; Peña, J.M.; Jiménez-Brenes, F.M.; Arquero, O.; Lovera, M.; López-Granados, F. Mapping the 3D Structure of Almond Trees Using UAV Acquired Photogrammetric Point Clouds and Object-Based Image Analysis. Biosyst. Eng. 2018, 176, 172–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vélez, S.; Vacas, R.; Martín, H.; Ruano-Rosa, D.; Álvarez, S. A Novel Technique Using Planar Area and Ground Shadows Calculated from UAV RGB Imagery to Estimate Pistachio Tree (Pistacia vera L.) Canopy Volume. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 6006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozenstein, O.; Fine, L.; Malachy, N.; Richard, A.; Pradalier, C.; Tanny, J. Data-Driven Estimation of Actual Evapotranspiration to Support Irrigation Management: Testing Two Novel Methods Based on an Unoccupied Aerial Vehicle and an Artificial Neural Network. Agric. Water Manag. 2023, 283, 108317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beeri, O.; Netzer, Y.; Munitz, S.; Mintz, D.F.; Pelta, R.; Shilo, T.; Horesh, A.; Mey-tal, S. Kc and LAI Estimations Using Optical and SAR Remote Sensing Imagery for Vineyards Plots. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 3478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).