Abstract

This study aimed to develop a deep learning-based application for the automatic detection of nutritional deficiencies in coffee plants through the analysis of in-field leaf images. Images were collected from farms in the Shipasbamba district and classified into six deficiency types: nitrogen (N), phosphorus (P), potassium (K), calcium (Ca), magnesium (Mg), and iron (Fe). A total of 2643 leaves were labeled and preprocessed for model training. Several YOLO architectures were evaluated, with YOLO11x achieving the best performance after 100 epochs, reaching a precision of 88.98%, recall of 88.54%, F1-Score of 88.76%, and mAP50 of 92.68%. An interactive web application was developed to allow real-time image upload and processing, providing both graphical and textual feedback on detected deficiencies. These results demonstrate the model’s effectiveness for automated diagnosis and its potential to support coffee growers in timely, data-driven decision-making, ultimately improving nutrient management and reducing production losses.

1. Introduction

Coffee is one of the most socioeconomically significant crops worldwide. It is a globally traded commodity that plays a crucial role in the economies of many countries—particularly in Latin America, Africa, and Asia—providing a livelihood for more than 125 million people across the globe [1]. Its value lies not only in its contribution to income generation but also in the preservation of rural traditions among smallholder farmers, whose coffee production in Peru has increased in recent years [2]. However, as with other crops, nutritional deficiencies in coffee plants reduce both yield and bean quality, thereby increasing production costs and diminishing competitiveness in international markets—factors often compounded by the presence of plant diseases [3].

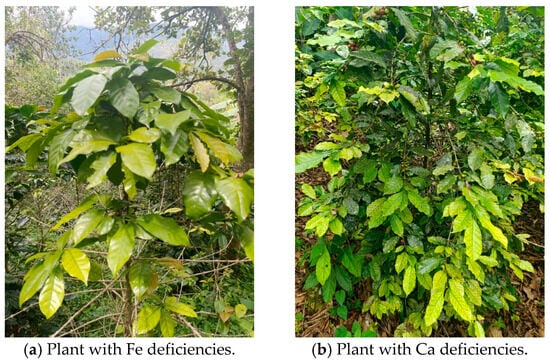

Among the most common nutritional deficiencies are nitrogen (N) deficiency [4], which causes yellowing of leaves and stunted growth; phosphorus (P) deficiency, leading to purplish or reddish discoloration on the underside of leaves and delayed development; potassium (K) deficiency, manifested by scorching and necrosis along leaf margins; calcium (Ca) deficiency, resulting in necrotic tips and margins as well as leaf deformation; magnesium (Mg) deficiency [5], characterized by interveinal chlorosis in older leaves while the veins remain green; boron (B) deficiency, leading to distortion of apical meristems and necrosis of young shoots; iron (Fe) deficiency, which produces interveinal chlorosis in young leaves with veins that stay green; and manganese (Mn) deficiency, which appears as interveinal chlorosis accompanied by small necrotic spots on the leaf blade [6].

Nutritional deficiencies are immediately reflected in the appearance of the leaves. To detect them, farmers typically walk through the crop rows, observing color variations, textures, and deformations, thereby identifying critical areas within minutes [7]. Complementarily, laboratory-based chemical analyses provide precise data on the actual nutrient content of the leaves; however, they only represent specific samples and require several days to produce results [8]. Due to the extensive size of coffee plantations, diagnoses are generally referential, combining visual inspection with periodic photographic records and a sampling plan that selects representative points.

A comprehensive inspection of coffee plantations using conventional methods is unfeasible in terms of both time and cost, as it requires extensive sampling and long waiting periods for laboratory results. To overcome these limitations, recent research has proposed the use of computer vision and machine learning techniques to enable faster detection and to estimate the nutritional status of plants across various crops. In study [9], a fertilizer recommendation system was developed based on the prediction of nutritional deficiencies. Using a dataset of 20,777 labeled images across 11 deficiency classes, the researchers implemented a ResNet-50 network that not only identified the specific deficiency with an accuracy of 98.18% but also generated nutrient application recommendations, demonstrating how computer vision can effectively complement agronomic decision-making.

On the other hand, study [10] demonstrated the feasibility of detecting nutritional deficiencies in guava leaves captured with mobile phones using lightweight CNN architectures. With a dataset focused on magnesium and phosphorus deficiencies, the system achieved an accuracy of 87%, validating the use of low-cost devices for real-time agronomic diagnostics. These previous studies support the use of computer vision and deep learning as effective tools for crop nutritional monitoring, offering rapid and highly accurate diagnoses.

In the field of viticulture, study [11] integrated a hybrid architecture combining Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN) and Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) to diagnose ten types of nutrient deficiencies in grapevine leaves. Using a dataset of representative images corresponding to nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium, iron, manganese, zinc, calcium, boron, magnesium, and sulfur deficiencies, the model combined the feature extraction capabilities of CNN with the sequential memory of LSTM, achieving an accuracy of 98.6%.

Similarly, in rice fields across China, Bangladesh, and India, study [12] evaluated the performance of five pretrained CNN models (InceptionV3, VGG16, VGG19, ResNet50, and ResNet152) for identifying nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium deficiencies in rice leaves. Data augmentation expanded the dataset from 1156 to 4963 images, and feature extraction followed by Support Vector Machine (SVM) classification achieved up to 97.40% accuracy without augmentation and 99.05% with augmentation, highlighting the importance of data diversity in model training.

Table 1 presents additional relevant studies on the detection of nutritional deficiencies in various crops through leaf analysis using computer vision and deep learning techniques.

Table 1.

Techniques and data used to detect nutritional deficiencies in crops.

The present research aimed to develop a deep learning–based application for diagnosing nutritional deficiencies in coffee plants through the analysis of in-field leaf images.

The justification for this research aligns with the 2030 Agenda, particularly Sustainable Development Goal 2 (Zero Hunger), targets 2.3 (“double the agricultural productivity and incomes of small-scale food producers”) and 2.4 (“ensure sustainable food production systems”) [19].

In this context, the proposed protocol is designed to directly support both farmers and agricultural specialists by providing a fast, low-cost, and automated diagnostic tool that identifies nutritional deficiencies in coffee plants through image analysis. This system facilitates timely decision-making in the field, allowing producers to apply specific fertilizers or corrective treatments based on precise information, thereby reducing resource waste and improving productivity. Moreover, specialists can use the generated data to monitor crop health trends, optimize nutrient management strategies, and contribute to more sustainable and efficient agricultural practices in coffee production.

2. Materials and Methods

Figure 1 illustrates the methodological workflow. The process began with the preparation of the previously collected and labeled dataset, followed by its division into training, validation, and testing subsets. Subsequently, object detection models were trained using the YOLO architecture, and their performance was evaluated using standard computer vision metrics. Finally, the trained model was integrated into a web-based application for end use. Each stage was designed to ensure the robustness of the model and its applicability under real-world agricultural conditions.

Figure 1.

Proposed methodology for the development of an application for detecting nutritional deficiencies in coffee plants.

2.1. Study Area and Data Collection

The present study was conducted in the district of Shipasbamba, which belongs to the province of Bongará, in the Amazonas department, located in the northeastern region of Peru. This area is characterized by its agricultural activity, with coffee cultivation (Coffea arabica) standing out as one of the main crops of economic importance.

The precise geographical location where the images were captured corresponds to the Pirca farm, with coordinates 5°54′29.9″ S latitude and 77°58′10.9″ W longitude. This area exhibits agroclimatic conditions that are ideal for coffee cultivation, with altitude, temperature, and humidity favorable for crop development. Figure 2 shows the location of the Shipasbamba district on the map of Peru.

Figure 2.

Location of Shipasbamba District in Peru.

And in Figure 3 you can see the location of the Pirca estate in the Shipasbamba district.

Figure 3.

Location of the Pirca estate in the Shipasbamba District.

2.2. Data Collection

There are several datasets of nutritional deficiencies in coffee leaves, however, these datasets are not of plants, but only of leaves, which does not make their use in real crops possible. In [20], a free dataset with 1006 images of coffee leaves from Peru (varieties CATIMOR, CATURRA and BORBON) is presented, captured in a controlled environment, not directly on plants. The dataset [21] contains images of crops, but these are images of leaves for disease classification. However, this study focuses on nutritional deficiencies in leaves.

In the present study, image collection was carried out following a standardized capture protocol in order to guarantee the quality and homogeneity of the data used in the training of the model. In total, 100 images corresponding to coffee leaves (Coffea arabica) of the caturra variety that presented visible signs of six types of nutritional deficiencies were captured: Micronutrients iron (Fe), magnesium (Mg), Macronutrients nitrogen (N), phosphorus (P), potassium (K) and calcium (Ca).

2.2.1. Capture Protocol

An Agronomist Engineer supervised the collection and labeling of the images, ensuring accurate identification and classification of nutritional deficiencies. To control for confounding factors—such as flooding, drought, or other stressors that can produce leaf symptoms similar to nutrient deficiencies—only healthy plants exhibiting clear, element-specific deficiency signs were selected. Leaves showing damage unrelated to nutrient deficiencies were excluded from the dataset.

The photographs were taken at an approximate distance of 1.5 m from the coffee plant to the mobile device, consistently maintaining the same angle and centering the focus on the leaves.

The average plant height was 2.5 m, with a 1 m spacing between rows to facilitate movement and ensure a standardized distance between the camera and the plant. An Agronomist Engineer supervised the collection and labeling of the images, ensuring accurate identification and classification of nutritional deficiencies.

A capture angle of 180° was used, with images taken frontally relative to the leaves, without any upward or lateral tilt.

Images were captured under natural light during field surveys, in sunny conditions with minimal wind interference.

Recording was performed in the morning to ensure adequate and consistent illumination.

Representative leaves were selected for each type of deficiency, ensuring a minimum number of samples per class.

Figure 4 shows two sample images included in the dataset. In Figure 4a, an image displays leaves with calcium nutritional deficiencies, while Figure 4b shows coffee plants with leaves exhibiting iron nutritional deficiencies.

Figure 4.

Sample images from the dataset.

2.2.2. Field Tour

The field survey was conducted on 15 June 2025, at the Pirca farm, located in the district of Shipasbamba, province of Bongará, Amazonas, Peru [22]. The survey covered a total area of 1 hectare (10,000 m2). During the fieldwork, a plant-by-plant visual inspection was performed to identify and capture leaves exhibiting characteristic symptoms of each nutritional deficiency. It was ensured that the selected plants were representative, and images of leaves damaged by pests or diseases unrelated to the study objectives were avoided. Table 2 presents the environmental conditions and image capture parameters for the coffee plants.

Table 2.

Environmental and capture conditions.

2.3. Data Annotation

Each image was reviewed with the support of a coffee cultivation expert, who identified and classified the leaves according to the type of nutritional deficiency. This process ensured the quality of the labeling and the accurate representation of each class.

For image annotation, the open-source software LabelImg [23] was used, which allows object labeling through bounding boxes. The labels were stored in the YOLO (You Only Look Once) format, enabling direct integration with object detection models of the YOLO family [24]. The annotations were saved in text files (.txt), where each line represents a single annotation with the following structure:

where

<class_id> <x_center> <y_center> <width> <height>

x_center: Center of the bounding box along the X-axis, normalized by dividing by the image width.

y_center: Center of the bounding box along the Y-axis, normalized by dividing by the image height.

width: Width of the bounding box, normalized by dividing by the image width.

height: Height of the bounding box, normalized by dividing by the image height.

Figure 5 shows the labels and annotations of two sample images included in the dataset.

Figure 5.

Sample images from the dataset with their annotations and labels.

Table 3 presents the number of annotations corresponding to each nutritional deficiency in coffee leaves.

Table 3.

Number of notes for each type of nutritional deficiency.

2.4. Data Augmentation

To increase the size of the training dataset, data augmentation strategies were employed, which are recognized as an effective approach to reduce overfitting [25]. In the present study, augmentation was carried out by applying incremental rotations within a range of −5° to +5°, simulating different viewing perspectives of the coffee leaves on the plant. This preliminary augmentation was applied to increase the number of objects in the dataset before the training phase. During training, additional data augmentation is performed internally by the YOLO framework. The total number of images generated through this procedure is summarized in Table 4.

where is the rotation angle.

Table 4.

Dataset details.

2.5. Coffee Detection

Once the images were captured and annotated using the LabelImg software version 1.8.6, the dataset was organized into three subsets to systematically train, validate, and evaluate the deep learning model. This division followed a widely adopted standard in computer vision: 70% for training, 15% for validation, and 15% for testing.

Each image was accompanied by its corresponding YOLO annotation file (.txt), which contains the bounding box coordinates and the class identifier corresponding to the nutritional deficiency present in the leaf.

This distribution was designed to maintain class balance and ensure that the models learn in a generalized manner, thereby minimizing the risk of overfitting.

YOLO

The initial model was developed using YOLO versions 8 and 11, employing the nano (“N”) configuration to accommodate resource-limited environments and the extra-large (“X”) configuration to maximize detection accuracy and overall performance. YOLO represents a family of object detection architectures that divides the input image into a grid and concurrently predicts multiple bounding boxes along with their corresponding class probabilities. In this study, all images were standardized to a resolution of 640 × 640 pixels. The model subsequently generates feature maps at multiple scales via downsampling operations. Unlike earlier versions, YOLOv8 and YOLO11 adopt an anchor-free strategy, whereby each grid cell directly predicts the bounding box coordinates and confidence scores without depending on predefined anchors. Moreover, the model estimates the likelihood of the Gossypium barbadense class.

The loss function is then calculated by incorporating errors in the bounding box coordinates (x, y, w, h), confidence scores, and class probabilities, thereby enhancing the precision of object detection.

2.6. Performance Evaluation

To evaluate the model’s performance in detecting nutritional deficiencies in coffee leaves, predictions are classified according to their correctness. A True Positive (TP) occurs when the model correctly identifies a leaf exhibiting a specific nutritional deficiency. A True Negative (TN) is recorded when the model accurately determines the absence of a deficiency in a given leaf. Conversely, a False Positive (FP) is assigned when the model incorrectly detects a deficiency in a healthy leaf, while a False Negative (FN) occurs when the model fails to detect an actual deficiency present in the leaf.

The following metrics were used to assess the model’s performance:

Precision (P): This is a metric that quantifies the proportion of true positives relative to the total number of elements classified as positive, thus evaluating the accuracy of the model’s positive predictions.

Recall (R): evaluates the model’s ability to correctly identify all current positive cases.

F1-score (F): provides a balanced measure of precision and recall.

Mean Average Precision at IoU = 0.5 mAP50: measures the model’s average precision across all classes using a fixed Intersection over Union (IoU) threshold of 0.5.

where APi is the Average Precision for class i, N is the total number of classes and APi@IoU = 0.5 is the average precision for class i at an IoU threshold of 0.5.

3. Results

3.1. Performance

During the model training phase for the detection of nutritional deficiencies in coffee leaves, the performance of the YOLOv8 and YOLO11 architectures was evaluated. For both architectures, three variants were trained: nano (n) and extra-large (x), in order to assess their performance and efficiency across different application scenarios. These versions allow comparison of the model’s performance in both resource-constrained environments and high-capacity processing platforms.

Efficiency. To evaluate efficiency, processing time, memory consumption, and CPU usage during the training phase were considered. Table 5 presents a comparison of the computational performance of the YOLOv8n, YOLOv8x, YOLO11n, and YOLO11x models during inference on the coffee leaf dataset. The evaluated parameters include total processing time (in seconds), RAM usage (in megabytes), and average CPU utilization (as a percentage).

Table 5.

Training Efficiency of the CNN Architectures Used.

In terms of processing time, the more complex models (YOLOv8x and YOLO11x) exhibited the highest values, with 4792.17 s and 4561.35 s, respectively. In contrast, the lighter models (YOLOv8n and YOLO11n) achieved significantly lower processing times, with 1935.91 s and 1961.24 s, respectively. This behavior is consistent with the architecture of these models, as the “n” versions are optimized for speed and efficiency in resource-constrained devices.

Regarding CPU usage, it was observed that the lighter models (YOLOv8n and YOLO11n) demand a higher processing load, with utilization rates of 70.25% and 71.15%, respectively, whereas the heavier models, such as YOLOv8x and YOLO11x, exhibit lower CPU usage (59.05% and 61.05%). This difference may be attributed to a more efficient distribution of parallel processing in the larger models, which tend to leverage the system’s multicore architecture more effectively.

In summary, the YOLOv8n and YOLO11n models offer advantages in processing speed, which is valuable in systems where response time is critical, but this comes at the cost of higher CPU and RAM consumption. Conversely, YOLOv8x and YOLO11x, although requiring more processing time, are more efficient in terms of system resource utilization and are preferable when model accuracy is prioritized over computational performance.

Performance. During the training phase, the performance of the CNN architectures for detecting nutritional deficiencies in coffee leaves was also evaluated. Table 6 presents the results obtained from evaluating the YOLOv8n, YOLOv8x, YOLO11n, and YOLO11x models in the task of detecting nutritional deficiencies in coffee leaves. Standard performance metrics, including precision, recall, F1-Score and mAP50, were employed to compare their effectiveness.

Table 6.

Performance of the CNN architectures used for detecting nutritional deficiencies in coffee leaves.

The YOLO11x model achieved the best overall performance, attaining a precision of 88.98%, a recall of 88.54%, and an F1-Score of 88.76%, demonstrating an excellent balance between correctly identifying positive cases and minimizing false positives. Additionally, the model achieved a mean Average Precision at IoU 0.5 (mAP50) of 92.68%, confirming its strong detection capability and consistency across different classes. This high F1-Score indicates that the model is robust and reliable for application in real-world environments, where accurate identification of nutritional deficiencies without overlooking relevant cases is essential.

The YOLOv8x model also exhibited notable performance, with a precision of 89.24% and an F1-Score of 87.44%, although its recall was slightly lower (85.72%) compared to YOLO11x. This suggests that, while the model is precise, it may fail to detect some positive cases, potentially limiting its effectiveness in scenarios that require comprehensive detection coverage.

The lighter, resource-optimized models, YOLOv8n and YOLO11n, showed lower performance compared to their more complex counterparts. YOLOv8n achieved an F1-Score of 82.14%, while YOLO11n reached 83.09%, indicating acceptable but less consistent performance in identifying nutritional deficiencies.

In summary, these results support the selection of YOLO11x as the most suitable model for the automated detection of nutritional deficiencies in coffee leaves, due to its high precision, coverage, and overall balanced performance.

Figure 6 illustrates the performance of the model trained with the four YOLO variants over 100 epochs.

Figure 6.

Performance of CNN architectures over 100 epochs. (a) Precision, (b) Recall, (c) F1 Score and (d) mAP50.

The trained model enables the detection of nutritional deficiencies. Figure 7 presents several sample images from the detection tests, illustrating the model’s effectiveness in accurately identifying each type of nutritional deficiency.

Figure 7.

Detection of Cotton Fruits with the Trained Model.

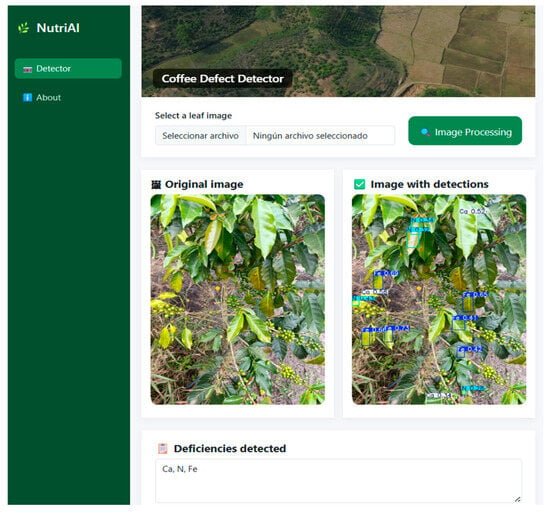

3.2. Application

Finally, Figure 8 illustrates the interaction flow between the interface and the backend for image analysis. After processing the input image, the application identifies the leaves exhibiting nutritional deficiencies, displays the detected labels on the image, and lists the identified deficiencies at the bottom of the interface.

Figure 8.

Image processing in the web application.

4. Discussion

The results obtained in this study demonstrate the potential of the YOLO11x model for the automatic detection of nutritional deficiencies in coffee leaves, achieving a remarkable balance between precision (88.98%), recall (88.54%), and F1-Score (88.76%). Additionally, the model reached a mean Average Precision at IoU threshold 0.5 (mAP50) of 92.68%, confirming its strong detection capability across all nutritional deficiency classes. These metrics indicate the model’s strong capability to accurately identify existing deficiencies while minimizing both false positives and false negatives, which is essential for its application in real agronomic contexts.

It is noteworthy that the central focus of this study was the development of a functional web application designed for practical use by farmers or field technicians. For this reason, the selection of the model emphasized lightweight YOLO versions that allow efficient implementation in resource-constrained environments while maintaining reasonable response times. Consequently, the focus was not exclusively on maximizing absolute model accuracy, but on achieving an appropriate balance between performance, speed, and deployability in a real application.

Compared to previous research, the results obtained align with those reported by various authors. For instance, in the study referenced in [9], a ResNet-50 network was used to classify nutritional deficiencies in different crops, achieving a precision of 98.18%. Although this figure exceeds that of the YOLO11x model, the study employed a deeper network with a larger dataset (20,777 images) and focused on generating personalized agronomic recommendations. In contrast, the present work prioritizes efficiency and rapid response within an automated analysis platform.

Similarly, study [10] achieved 87% accuracy using lightweight CNNs to diagnose specific deficiencies in guava leaves from images captured with mobile phones. This approach is comparable to the present study, as both emphasize field usability and low-cost device implementation. The YOLOv8n (82.14%) and YOLO11n (83.09%) models exhibited similar performance, albeit with a slight disadvantage, possibly attributable to variability in capture conditions or differences between crop types.

On the other hand, studies employing more sophisticated architectures, such as the viticulture work [11], combined CNN and LSTM networks to diagnose up to ten types of deficiencies in grapevine leaves, achieving 98.6% accuracy. Although this performance is higher, the model used was not designed for real-time execution within a lightweight application, as in the present study. Thus, the use of YOLO11x is justified by its balance between accuracy and integration capability in a functional platform.

Likewise, in the study conducted in Asian rice fields [13], five pre-trained models were evaluated with SVM as a classifier, achieving up to 99.05% accuracy with data augmentation. These results reinforce the relevance of data augmentation, a technique also employed in this study to improve model generalization against the variability of coffee leaf images.

From the perspective of computational performance, the lightweight models (YOLOv8n and YOLO11n) were significantly faster, with processing times of 1935.91 s and 1961.24 s, respectively. However, this benefit was accompanied by higher CPU and RAM usage, which may be limiting on low-capacity devices. Conversely, the more complex models (YOLOv8x and YOLO11x) demonstrated better resource management at the cost of longer processing times, a trade-off deemed acceptable considering their superior performance in terms of precision and F1-Score.

Furthermore, the implementation of this protocol has the potential to significantly benefit farmers by enabling early and accurate detection of nutritional deficiencies in coffee plants. By using the proposed system, producers can make timely, data-driven decisions regarding fertilizer application and crop management, avoiding unnecessary treatments and optimizing resource use. This not only helps maintain crop health and improve yields but also reduces production costs by minimizing manual field inspections, decreasing fertilizer waste, and preventing productivity losses caused by undetected deficiencies.

In terms of future research directions, this study paves the way for extending the model’s applicability to other crops beyond coffee, allowing the development of multi-crop diagnostic tools suitable for diverse agricultural contexts. Additionally, efforts will focus on enhancing the model’s robustness under more varied environmental conditions, such as different lighting, weather, and leaf orientations, to ensure consistent performance in real-world scenarios.

5. Conclusions

A representative dataset of coffee leaves affected by six nutritional deficiencies (N, P, K, Ca, Mg, and Fe) was successfully collected and accurately labeled, enabling robust model training. The images underwent preprocessing, including contrast enhancement, slight rotations, and normalization, which improved dataset diversity and model generalization.

Among the YOLO variants evaluated (YOLOv8n, YOLOv8x, YOLO11n, YOLO11x), YOLO11x achieved the best performance with a precision of 88.98%, recall of 88.54%, and F1-Score of 88.76%, balancing accuracy and computational efficiency for practical deployment.

A functional web application was developed to integrate the trained model, allowing users to upload coffee leaf images for immediate nutritional diagnosis, with visual and textual outputs for affected nutrients. System evaluation showed that lightweight models (YOLOv8n, YOLO11n) offered faster processing but higher resource usage, while larger models (YOLOv8x, YOLO11x) provided higher accuracy and better resource optimization. Overall, YOLO11x was identified as the most suitable model for this application.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.C.-M., U.T.-G. and J.A.-D.; methodology, C.C.-M., U.T.-G., J.A.-D. and H.I.M.-C.; software, C.C.-M., U.T.-G. and J.A.-D.; validation, C.C.-M., U.T.-G. and J.A.-D.; formal analysis, H.I.M.-C. and J.A.-D.; investigation, C.C.-M., U.T.-G. and J.A.-D.; data curation, C.C.-M., U.T.-G.; writing—original draft, C.C.-M., U.T.-G., J.A.-D. and H.I.M.-C.; writing—review and editing, H.I.M.-C. and J.A.-D.; supervision, J.A.-D. and H.I.M.-C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The APC was funded by the Universidad Señor de Sipán (Perú).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Mishra, M.K. Genetic Resources and Breeding of Coffee (Coffea spp.). In Advances in Plant Breeding Strategies: Nut and Beverage Crops; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 475–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grashuis, J.; Skevas, T. What is the benefit of membership in farm producer organizations? The case of coffee producers in Peru. Ann. Public Coop. Econ. 2023, 94, 423–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira-Morrillo, A.A.; Vélez-Zambrano, J.P.; Intra Moreira, S.; Garcés-Fiallos, F.R. Diseases affecting the coffee crop: Elucidating the life cycle of Rust, Thread Blight and Cercospora Leaf Spot. Sci. Agropecu. 2023, 13, 395–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- León-Burgos, A.F.; Rendón Sáenz, J.R.; Imbachi Quinchua, L.C.; Unigarro, C.A.; Osorio, V.; Khalajabadi, S.S.; Bala-guera-López, H.E. Varying fruit loads modified leaf nutritional status, photosynthetic performance, and bean biochemical composition of coffee trees. Sci. Hortic. 2024, 329, 113005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores, R.A.; Borges, B.M.M.N.; Almeida, H.J.; De Mello Prado, R. Growth and nutritional disorders of coffee cultivated in nutrient solutions with suppressed macronutrients. J. Plant Nutr. 2016, 39, 1578–1588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perígolo, D.; Nogueira, N.O.; César, M.d.S.; Rocha, B.C.P.; Clemente, J.M. Widespread nutritional imbalances of coffee plantations. J. Plant Nutr. 2023, 46, 2407–2415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evizal, R.; Erry Prasmatiwi, F. Nutrient Deficiency Induces Branch and Shoot Dieback in Robusta Coffee. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2022, 1012, 012073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, H.E.P.; Souza, R.B.; Abadía Bayona, J.; Hugo Alvarez Venegas, V.; Sanz, M. Coffee-Tree Floral Analysis as a Mean of Nutritional Diagnosis. J. Plant Nutr. 2003, 26, 1467–1482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prathik, K.; Madhuri, J.; Bhanushree, K.J. Deep Learning-Based Fertilizer Recommendation System Using Nutrient Deficiency Prediction. In Proceedings of the 2023 7th International Conference on Computation System and Information Technology for Sustainable Solutions (CSITSS), Bangalore, India, 2–4 November 2023; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haris, S.; Sai, K.S.; Rani, N.S. Nutrient Deficiency Detection in Mobile Captured Guava Plants using Light Weight Deep Convolutional Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the 2023 2nd International Conference on Applied Artificial Intelligence and Computing (ICAAIC), Salem, India, 4–6 May 2023; pp. 1190–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priyaradhikadevi, T.; Santhosh Kumar, C.; Srivani, A.; Palanivel, N.; Madhan, K.; Kavitha, K. Deficiencies Identification and Detection in Grape Plant Leaves Using LSTM and CNN Model. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on System, Computation, Automation and Networking (ICSCAN), Puducherry, India, 27–28 December 2024; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Supreetha, S.; Premalathamma, R.; Manjula, S.H. Deep Learning Techniques to Detect Nutrient Deficiency in Rice Plants. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Inventive Computation Technologies (ICICT), Lalitpur, Nepal, 24–26 April 2024; pp. 699–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalita, H.; Sharma, U. Machine Learning Applications for Precise Nutrient Deficiency Detection in Paddy Farming Using K-Means Clustering and SVM. In Innovative Computing and Communications; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024; pp. 623–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolhar, S.; Jagtap, J.; Shastri, R. Deep Neural Networks for Classifying Nutrient Deficiencies in Rice Plants Using Leaf Images. Int. J. Comput. Digit. Syst. 2024, 15, 305–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhagirath, S.N.; Bhatnagar, V.; Raja, L. Prediction of Nitrogen Deficiency in Paddy Leaves Using Convolutional Neural Network Model. In Advances in Data-driven Computing and Intelligent Systems; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023; pp. 711–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begum, S.S.; Chowdary, M.C.C.; Devi, T.R.; Nallamothu, V.P.; Jahnavi, Y. Deep Learning-based Nutrient Deficiency symptoms in plant leaves using Digital Images. In Proceedings of the 2023 Second International Conference on Advances in Computational Intelligence and Communication (ICACIC), Puducherry, India, 7–8 December 2023; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamelia, L.; Nurmalasari, R.R. Analysis of Decision Tree and Random Forest Algorithms for Nutrient Deficiency Classification in Citrus Leaves through Image Processing. 2023 17th International Conference on Telecommunication Systems, Services, and Applications, TSSA 2023, Lombok, Indonesia, 12–13 October 2023; Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, A.; Mishra, R.; Sharma, A. Classification Nutrient Deficiency of Maize Plant Leaf Using Machine Learning Algorithm. Fusion Pract. Appl. 2025, 17, 78–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bąk, I. Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs): Concept and measurement. In The Role of Financial Markets in Achieving the Sustainable Development Goals; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2024; pp. 15–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuesta-Monteza, V.A.; Mejia-Cabrera, H.I.; Arcila-Diaz, J. CoLeaf-DB: Peruvian coffee leaf images dataset for coffee leaf nutritional deficiencies detection and classification. Data Brief 2023, 48, 109226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jepkoech, J.; Mugo, D.M.; Kenduiywo, B.K.; Too, E.C. Arabica coffee leaf images dataset for coffee leaf disease detection and classification. Data Brief 2021, 36, 107142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wikipedia. Distrito de Shipasbamba. Available online: https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Distrito_de_Shipasbamba (accessed on 14 July 2025).

- Tzutalin. LabelImg: Image Annotation Tool. Available online: https://github.com/HumanSignal/labelImg (accessed on 21 December 2024).

- Ali, M.L.; Zhang, Z. The YOLO Framework: A Comprehensive Review of Evolution, Applications, and Benchmarks in Object Detection. Computers 2024, 13, 336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.-Y.; Hsieh, C.-J. (Eds.) Chapter 21-Data augmentation for unsupervised machine learning. In Adversarial Robustness for Machine Learning; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 241–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).