Abstract

This paper proposes a fruit-harvesting robot system that improves harvesting efficiency by utilizing a Reachability Map (RM) and an Inverse Reachability Map (IRM). The proposed system accurately detects fruit locations using You Only Look Once version 5 (YOLOv5)–based object detection and camera calibration. Through coordinate transformation and hand–eye calibration, the manipulator is precisely guided to the fruit’s 3D position. During the construction of the reachability map, the reachability index, manipulability isotropy, and harvesting index are jointly considered to quantitatively evaluate manipulator performance. Fruits accessible by the manipulator are prioritized for harvesting. For fruits that cannot be directly reached, the system computes the optimal base pose using the inverse reachability map, enabling the mobile manipulator to reposition itself for harvesting. To further enhance efficiency, multiple fruits are grouped to minimize unnecessary movements. The integrated system is implemented on the Robot Operating System 2 (ROS 2), where fruit detection, autonomous navigation, and harvesting are executed as independent nodes to support scalable and modular operation. Finally, the proposed system is validated in a simulated orchard environment, confirming its effectiveness in improving autonomous fruit-harvesting performance.

1. Introduction

Globally, rural populations have been declining rapidly, a pattern that is particularly pronounced in developed countries. According to the United Nations’ World Urbanization Prospects [1], rural populations exceeded urban populations until the mid-20th century. However, accelerated urbanization has fundamentally shifted this balance, resulting in urban populations becoming significantly larger than rural ones. Korea exhibits a similar demographic trajectory. Statistics Korea (2023) indicates that the number of farming households has fallen below one million for the first time, and the rural population continues to diminish [2]. Moreover, nearly half of all agricultural workers are now aged 65 or older, demonstrating a rapidly advancing aging trend within rural communities. These global and national demographic transitions exacerbate labor shortages, reduce agricultural productivity, and pose substantial challenges to the long-term sustainability of agricultural systems in developed economies.

To address these challenges, the agricultural sector has increasingly adopted advanced technologies such as the Internet of Things (IoT),artificial intelligence (AI), big data, and robotics, leading to the emergence of smart farming systems.

Among various agricultural tasks, fruit harvesting remains one of the most labor-intensive operations, making automation a critical research priority [3]. Recent studies have explored a wide range of fruit-harvesting solutions. Onishi et al. [4] employed an SSD-based detector with stereo vision for IK-based apple harvesting. Han and Shin [5] applied reachability maps to evaluate optimal manipulator poses for tomato harvesting. Kim et al. [6] implemented visual servoing for melon harvesting using a hemispherical workspace. Won et al. [7] developed a rocker–bogie-type robot capable of stable locomotion in uneven open-field environments for persimmon harvesting. However, these prior approaches still face limitations in seamlessly integrating robots into real orchards and supporting intuitive operation for non-expert users.

For effective field operation, both the robot and the operator must clearly understand the manipulator’s reachable workspace and kinematic constraints. Without such understanding, selecting an appropriate base pose often depends on user intuition, which may reduce operational efficiency and increase the risk of mechanical damage or safety issues. Non-expert users frequently assume that a manipulator’s reachable workspace is a simple spherical region defined by its maximum reach.

In reality, joint limits, link geometry, and mechanical constraints significantly restrict reachable positions and orientations, and certain configurations may even lead to singularities that prevent successful task execution. Therefore, a quantitative assessment of the manipulator’s kinematic feasibility and dexterity is essential.

Recent research has applied reachability maps (RMs) and inverse reachability maps (IRMs) for analyzing manipulator workspaces and optimizing robot base placement. Müller et al. [8] investigated manipulator dexterity using RMs for grasp point detection and path planning. Burget and Bennewitz [9] solved inverse reachability problems using IRMs to identify optimal base positions. Yoshikawa [10] introduced the manipulability ellipsoid derived from the Jacobian matrix to quantify directional dexterity. Kang and Ha [11] proposed an occlusion-aware, vision-based approach for reachability evaluation. Jeong et al. [12] constructed an RM and IRM using end-effector manipulability to optimize robot base positioning. However, conventional approaches relying on a single index have inherent limitations.

Furthermore, as modern orchards expand in scale and exhibit complex spatial layouts, autonomous fruit-harvesting systems must be designed to remain scalable and adaptable. The proposed system leverages a modular multi-node architecture based on ROS 2, where each functional module—fruit detection, 3D localization, motion planning, and base-pose optimization—is implemented as an independent node. This structure enables distributed processing and horizontal scalability, ensuring efficient operation even in large orchards. Additionally, the RM/IRM framework relies on precomputed voxel-based workspace maps rather than orchard-specific geometry, allowing the system to generalize effectively to diverse and unstructured field environments.

To address overcome these limitations, this paper proposes a comprehensive reachability evaluation framework integrating three performance indices: (1) reachability score, (2) manipulability isotropy, and (3) harvestability index.

The IRM is further used to compute optimal base poses for unreachable fruits, minimizing unnecessary movements and improving overall harvesting efficiency.

The proposed system was implemented using ROS 2 and validated in a virtual orchard environment using the Gazebo simulator. This integration enabled realistic testing of autonomous fruit detection, 3D localization, motion planning, and harvesting operations.

The main contributions of this paper are summarized as follows:

- A quantitative reachability evaluation framework was developed using the RM to systematically analyze the manipulator’s workspace and assess feasibility for various fruit poses.

- An IRM-based base-pose optimization method was integrated to enable effective harvesting of fruits located beyond the manipulator’s nominal reach.

- A fully autonomous harvesting system was implemented in a realistic virtual orchard environment using ROS 2 and Gazebo, demonstrating the effectiveness and practical potential of the proposed approach.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 introduces the theoretical foundations and mathematical formulations of the RM and IRM. Section 3 presents the ROS 2–based system architecture and operational workflow. Section 4 describes the experimental setup and evaluates system performance. Section 5 concludes the paper with final remarks and future research directions.

2. Related Works

2.1. Camera Calibration for 3D Pose Estimation

Accurate camera calibration is a fundamental requirement for any vision-based robotic system, as it defines the geometric relationship between the 3D world coordinate system and the 2D image plane. Errors in calibration propagate throughout the entire processing pipeline and can result in significant spatial offsets in 3D pose estimation and motion control. In this study, camera calibration was performed to obtain the intrinsic and extrinsic parameters of the RGB-D camera used for fruit recognition and localization.

Zhang’s method was adopted because it requires only a planar checkerboard pattern and multiple images from different viewpoints to estimate lens distortion coefficients and focal lengths simultaneously [13]. This approach has become the de facto standard in robotic vision applications due to its simplicity and accuracy. In the Zhang calibration framework, the relationship between a 3D world point and its 2D image projection is expressed as

Here, A denotes the camera intrinsic matrix, which includes the focal lengths , the principal point coordinates , and the skew coefficient that accounts for the non-orthogonality of the image axes. These intrinsic parameters define the geometric relationship between the camera sensor and the image plane and are determined by the physical properties of the lens and the pixel dimensions of the sensor. R and t represent the extrinsic parameters of the camera, corresponding to the rotation matrix and translation vector, respectively.

They define the rigid-body transformation from the world coordinate system to the camera coordinate system, where R specifies the camera orientation and t specifies the camera position in space. Therefore, Equation (1) serves as a fundamental geometric model for transforming 2D pixel coordinates into metric 3D coordinates, which is essential for precise fruit localization and robot manipulator control in vision-guided harvesting systems.

To further refine the accuracy, the re-projection error was iteratively minimized using the Levenberg–Marquardt optimization algorithm. The final reprojection error was below 0.35 pixels on average, which ensured sub-millimeter accuracy in depth-to-world projection. This level of precision was necessary to enable reliable fruit localization under variable lighting and distance conditions.

2.2. Deep Learning-Based Fruit Recognition and 3D Localization

Deep learning (DL) has become a key enabler of robotic fruit harvesting, providing robust perception, 3D localization, and maturity estimation under natural orchard conditions. Traditional image-processing methods are often affected by illumination variation, occlusion, and complex backgrounds. Consequently, recent research has focused on convolutional neural networks (CNNs) such as YOLO (You Only Look Once), Mask R-CNN, and DeepLab, which offer high detection accuracy and real-time inference. Onishi et al. [14] developed an SSD-based stereo-vision system for fruit depth estimation, while Hou et al. [15] optimized the YOLOv5 architecture for citrus detection, improving precision suitable for robotic harvesting. Lightweight CNNs combined with attention mechanisms have also been proposed to enhance robustness under occlusion and fruit clustering [16].

Among existing frameworks, YOLOv5 has been widely employed for real-time fruit detection and 3D localization owing to its balance between accuracy and computational efficiency. It utilizes a CSPDarknet53 backbone for feature extraction and a PANet-based neck for multi-scale feature aggregation, enabling the detection of fruits with diverse sizes and lighting conditions. The training process typically involves data augmentation methods such as mosaic augmentation and color jittering, and a composite loss function composed of bounding-box regression, objectness, and classification losses [15]:

where denotes the bounding-box regression loss computed using the Complete IoU (CIoU) metric, which considers not only the IoU overlap but also the distance between the box centers and the difference in aspect ratios, enabling stable and accurate bounding-box regression. represents the objectness loss that evaluates how accurately the network predicts the probability of an object being present within each anchor box, and is computed using the binary cross-entropy (BCE) between the predicted scores and the ground-truth labels. denotes the classification loss applied to each predicted bounding box, where YOLOv5 employs a BCE-based multi-label classification scheme rather than a softmax-based approach. The weighting factors , , and control the relative contributions of the CIoU regression loss, objectness loss, and classification loss, respectively, and are empirically determined to ensure stable learning and improved detection performance.

Depth information from an RGB–D or stereo camera is often fused with 2D detections to compute the 3D position of fruits using the inverse projection model:

where is the detected pixel position and Z is the corresponding depth value. This geometric relationship has been widely used for spatial localization in harvesting robots.

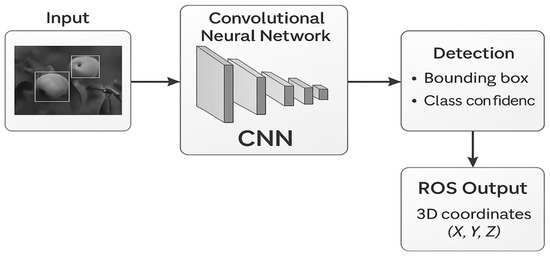

To illustrate this process, Figure 1 shows the overall detection and 3D localization pipeline, where YOLOv5 provides 2D bounding boxes and class confidence, and depth data are fused to estimate the 3D fruit coordinates.

Figure 1.

General YOLOv5 detection and 3D localization pipeline for fruit recognition in agricultural robotics.

2.3. Hand–Eye Calibration and Coordinate Transformation

In robotic manipulation, hand–eye calibration is critical for aligning the camera coordinate system with the robot base coordinate system. Without this calibration, the 3D positions of detected fruits cannot be accurately mapped to the manipulator’s workspace. The hand–eye transformation is typically represented by a homogeneous transformation matrix that describes the pose of the camera relative to the robot base. This transformation can be formulated as

where and represent the known motion of the robot base and the corresponding motion of the camera, respectively, and X is the unknown hand–eye transformation matrix . Several methods exist for hand–eye calibration, including Tsai and Lenz (1989)’s algorithm [17] and Daniilidis (1999)’s dual quaternion formulation [18]. In this study, the dual quaternion approach is chosen for its numerical stability and compact representation of rotation and translation. The procedure involves moving the manipulator to multiple known poses while observing a fixed calibration target.

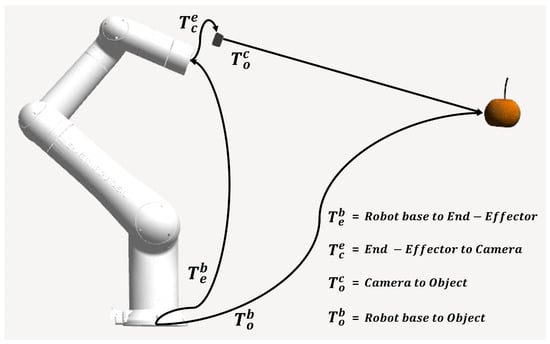

The transformation pipeline used in this paper involves sequential frame conversions.

Each transformation is expressed in homogeneous coordinates to preserve rigid–body consistency. As a result, the 3D position of a fruit in the camera frame can be expressed in the robot base frame as

This calibrated relationship enables the robot to execute precise picking motions guided by vision.

2.4. Reachability and Inverse Reachability Mapping

The concept of reachability maps (RMs) was first introduced to quantitatively describe a robot manipulator’s workspace by discretizing it into voxel cells and evaluating each pose’s kinematic feasibility. Zacharias et al. [19] demonstrated the use of RMs for grasp planning in humanoid robots, while Porges et al. [20] extended the approach to industrial arms for assembly tasks. These methods typically evaluate each voxel by sampling a set of end-effector orientations and checking whether inverse kinematics (IK) solutions exist within joint limits. The reachability score is then defined as the ratio of reachable orientations to the total tested orientations. Mathematically, the reachability index (RI) at a given voxel is defined as

where is the number of reachable orientations and is the total number of sampled orientations. This index provides a probabilistic measure of how likely it is that the manipulator can achieve a desired pose within the local workspace.

Building on this concept, the inverse reachability map (IRM) inverts the relationship by describing the possible base poses from which a given end-effector pose is reachable. An IRM was first applied to mobile manipulators by Stilman and Kuffner [21] for humanoid motion planning and was later adapted for agricultural robots by Zhou et al. [22]. By combining an RM and IRM, it becomes possible to determine optimal base positions for multi-target harvesting tasks and plan repositioning when targets are outside the current workspace.

In this paper, the reachability map is enhanced by introducing three quantitative indices:

- the Reachability Index (RI) for pose feasibility,

- the Manipulability Isotropy (MI) for directional dexterity, and

- the Harvestability Index (HI) for task success probability.

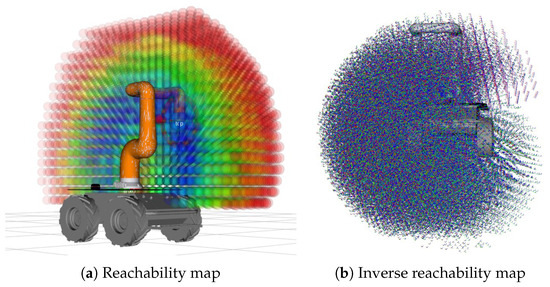

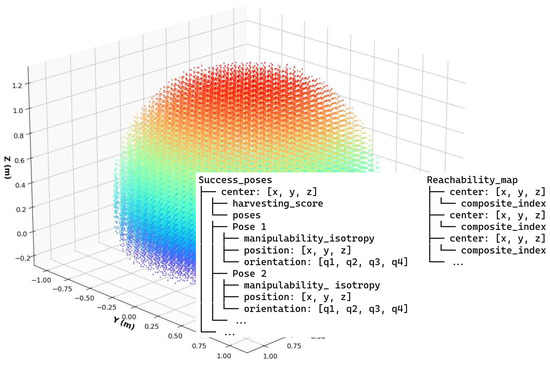

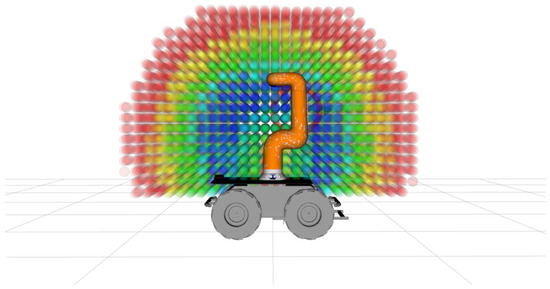

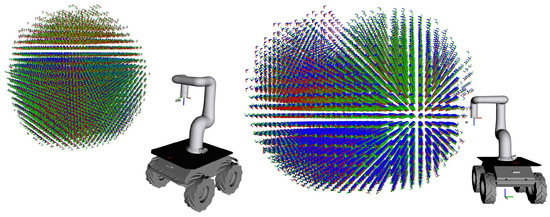

These indices are aggregated into a composite reachability score (CRS) to create a fine-grained representation of the manipulator’s performance space. Furthermore, a KD-Tree-based nearest-neighbor search [23] is used to accelerate matching between the IRM and fruit positions during base pose optimization. To clearly illustrate the spatial structure of the reachable workspace and the corresponding inverse mapping, Figure 2 presents the reachability map and the inverse reachability map used in this paper.

Figure 2.

Visualization of the reachability and inverse reachability maps for the robot manipulator. (a) shows the feasible end-effector workspace colored by reachability score and (b) illustrates the corresponding inverse reachability map indicating possible robot base positions.

2.5. Challenges in Vision-Guided Harvesting and Research Gap

While a considerable body of literature has explored object recognition and robotic manipulation in agriculture, real-world implementation still faces numerous challenges. The first major issue is the mismatch between perceptual detection and manipulator reachability. Even when fruits are accurately detected in 3D, the robot may be unable to reach them due to mechanical constraints or unfavorable approach angles. Secondly, base pose selection is often performed manually or heuristically, resulting in non-optimal movement paths and increased operation time. Third, most existing systems lack a robust feedback mechanism linking perception, motion planning, and control in real time.

This research addresses these limitations through an integrated framework that unites visual perception, reachability analysis, and ROS 2-based control. By leveraging quantitative workspace indices and distributed communication between ROS nodes, the system achieves fully autonomous harvesting capability with real-time feedback and dynamic base pose adjustment. Such integration not only improves fruit-picking success rates but also provides a foundation for adaptive task planning in unstructured agricultural environments [24,25,26].

3. Methodology

The proposed robotic fruit harvesting framework integrates visual perception, coordinate transformation, reachability mapping, and motion planning under a unified ROS 2 environment. This section presents the detailed methodology used to achieve accurate fruit localization, efficient manipulator motion, and optimal base repositioning for multi-fruit harvesting.

3.1. Deep-Learning-Based Fruit Detection and 3D Localization

3.1.1. Camera Calibration

Accurate 3D localization of fruits from RGB–D images requires reliable camera calibration to correct lens distortion and align image pixels with the world coordinate system. The calibration process estimates intrinsic and extrinsic parameters by minimizing the reprojection error between known 3D world points and their corresponding 2D image projections.

The calibration is performed using Zhang’s planar checkerboard method [13]. A checkerboard with known grid dimensions was captured from multiple viewpoints and orientations using an Intel RealSense D435i RGB–D camera. The corner points were detected using OpenCV’s findChessboardCorners() function and refined to sub-pixel accuracy. Distortion coefficients and intrinsic parameters were optimized via the Levenberg–Marquardt algorithm. The mean reprojection error achieved was 0.32 pixels, confirming the calibration’s precision for accurate 3D reconstruction.

3.1.2. Fruit Detection Using YOLOv5

The trained YOLOv5 network was deployed within the ROS 2 framework for real-time fruit recognition. Upon receiving RGB images from the Intel RealSense D435i camera, the detector identified fruit instances and produced bounding boxes with class labels and confidence scores. For each detected fruit, the center pixel coordinate was extracted as the target position:

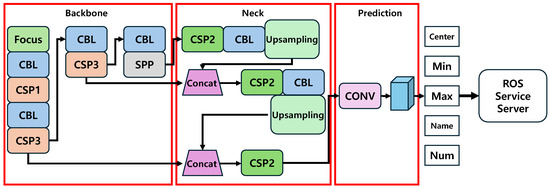

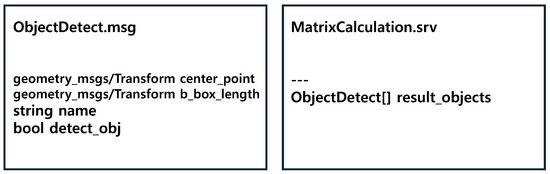

where and denote the upper-left and lower-right coordinates of the bounding box, respectively. The YOLOv5 node published detection results as ROS 2 topics containing bounding-box metadata. The perception module subscribed to these topics and synchronized them with depth frames to compute the fruit’s 3D position using the inverse projection model. The overall communication pipeline between YOLOv5-based fruit detection, depth mapping, and manipulation planning was organized within the ROS 2 framework, as illustrated in Figure 3. The computed 3D positions were packaged as a custom ROS message and transmitted to the manipulation planning node for further processing, as illustrated in Figure 4.

Figure 3.

YOLOv5 detection and ROS 2 communication structure for real-time fruit recognition.

Figure 4.

ROS 2 custom service message structure for transmitting 3D fruit position data to the manipulation node.

The data flow between YOLOv5 detection, depth mapping, and manipulation planning was structured using a ROS 2 publisher–subscriber mechanism for asynchronous yet synchronized communication between perception and motion-planning nodes.

3.2. Eye-in-Hand Transformation for End-Effector to Camera Calibration

In this study, an Eye-in-Hand configuration was adopted, where the RGB–D camera was rigidly mounted on the robot’s end-effector. To determine the spatial relationship between the end-effector and the camera, a hand–eye calibration was performed. The goal was to compute the homogeneous transformation matrix from the end-effector coordinate frame to the camera coordinate frame, denoted as .

The estimation was carried out using the classical Tsai and Lenz algorithm [17], implemented in OpenCV. The resulting homogeneous transformation matrix from the end-effector to the camera was defined as

where and denote the rotation and translation components from the end-effector frame to the camera frame, respectively.

To provide a clearer understanding of the coordinate relationships used in the hand–eye calibration process, Figure 5 illustrates the Eye-in-Hand configuration and the corresponding transformation frames.

Figure 5.

Eye-in-Hand configuration showing the coordinate transformation relationships. The transformation represents the pose of the camera relative to the end-effector, while and denote the base-to-end-effector and base-to-object transformations, respectively.

The forward kinematics of the manipulator were computed using the ROS 2 MoveIt 2 library to obtain the transformation from the robot base to the end-effector. Hence, the 3D position of a detected fruit in the robot base frame can be obtained through the following transformation:

where is the homogeneous coordinate of the fruit position expressed in the camera coordinate frame and is the corresponding point expressed in the robot base coordinate frame. This transformation ensures spatial alignment between the detected fruit position in the camera frame and the robot manipulator’s workspace for motion planning and grasp execution.

3.3. Harvest Pose Calculation and Path Planning

To perform effective harvesting, the robot must determine the optimal pose for the end-effector to reach and grasp the fruit. The process begins by sorting all detected fruits based on their Euclidean distance from the camera center, defined as

where represents the 3D position of the i-th fruit in the camera coordinate frame, and denotes the camera center. Fruits are processed in ascending order of distance, prioritizing those closest to the manipulator for efficient harvesting. Although the YOLOv5 and depth camera can estimate the 3-D position of each fruit , the rotational component is not directly provided.

Therefore, the robot end-effector is initially oriented to face forward, and an additional yaw compensation is applied according to the fruit’s position. This correction reduces potential harvesting failure caused by limited rotation and allows the manipulator to reach the fruit in an appropriate direction. The yaw angle is determined from the fruit position in the camera coordinate system as follows:

The yaw value determines the rotational alignment of the end-effector relative to the fruit. To prevent direct contact with the fruit surface, an approach offset of approximately 5 cm toward the camera direction is applied. The final harvesting position is then calculated by applying the yaw-dependent offset as follows:

where d represents the approach offset distance (set to 0.05 m in this study) and indicates the adjusted approach position in the yaw direction. This offset allows the manipulator to approach the fruit smoothly while avoiding collisions. Figure 6 illustrates the overall harvesting pose calculation procedure based on the yaw angle and offset and Figure 7 shows the final harvesting pose in a simulated environment.

Figure 6.

Harvest pose calculation process based on yaw angle and approach offset.

Figure 7.

Final harvesting pose of the manipulator in simulation: (a) side view and (b) top-right oblique view.

Based on the calculated fruit pose, inverse kinematics (IK) is solved using the Kinematics and Dynamics Library (KDL) integrated in ROS 2 MoveIt 2. Among multiple IK solutions, the one that minimized joint displacement is selected. The joint-space cost function is defined as

where and represent the initial and final angles of the ith joint, respectively. evaluates the overall joint displacement between the start and target configurations. For collision-free path generation, the Rapidly-Exploring Random Tree Connect (RRT-Connect) algorithm proposed by Kuffner and LaValle [27] is employed through the Open Motion Planning Library (OMPL). The algorithm efficiently connects two trees expanding from the start and goal configurations, offering fast and reliable single-query path planning. Ten candidate trajectories are generated, and the trajectory with the smallest is selected as the final motion path. This ensures that the manipulator can reach the fruit efficiently with minimal joint movement and smooth motion execution.

3.4. Reachability and Inverse Reachability Map Construction

The Reachability Map (RM) is a computational tool used to quantitatively evaluate the capability of a robot manipulator to reach specific poses within its workspace [28]. It provides a spatial representation of the manipulator’s dexterity, enabling quantitative analysis of reachable regions, operational flexibility, and harvesting feasibility. In this paper, the robot workspace is discretized into voxel units, and various poses within each voxel are generated and evaluated based on reachability, harvestability, and manipulability indices.

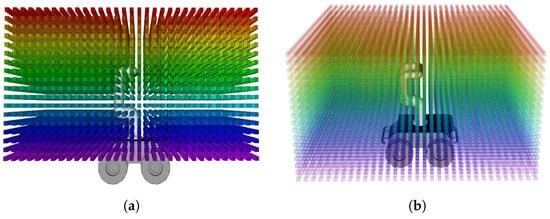

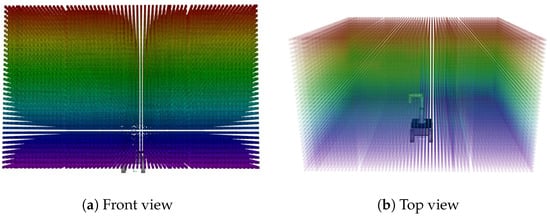

3.4.1. Workspace Voxelization

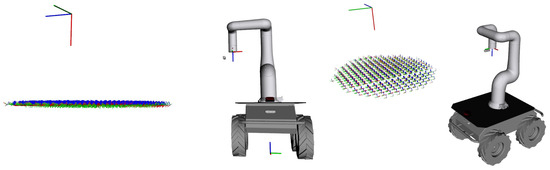

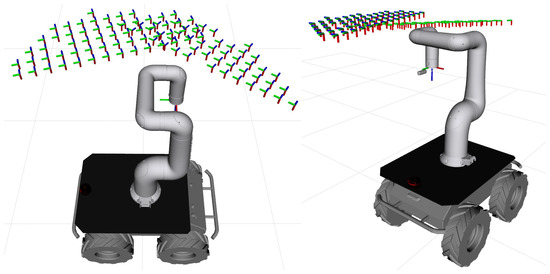

The workspace voxelization process divides the robot’s reachable space into small cubic units (voxels) to quantitatively assess the manipulator’s accessibility. An octree-based hierarchical structure is used to efficiently subdivide the space, with the root node corresponding to the manipulator base and each node connected to eight sub-nodes. The voxel resolution determines how finely the workspace is analyzed; smaller voxels yield higher precision but require greater computational cost. To balance accuracy and efficiency, a voxel resolution of 0.08 m is employed in this paper. Figure 8 illustrates the voxelized structure of the robot’s workspace.

Figure 8.

Voxelization of the robot workspace: (a) side view and (b) top view.

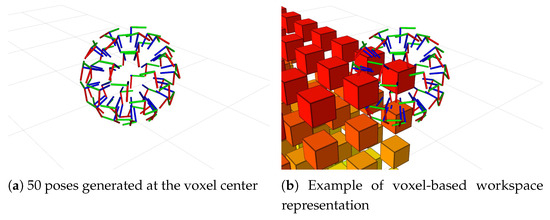

3.4.2. Pose Generation and Reachability Index Calculation

For each voxel center, multiple potential end-effector poses are generated to evaluate the manipulator’s accessibility. A Fibonacci Spiral Sphere sampling method is used to uniformly distribute poses across the surface of a unit sphere, avoiding clustering while maintaining consistent angular coverage. The longitude () and latitude () of each sampled pose are computed using the golden angle principle:

where i is the pose index and N is the total number of sampled orientations (50 per voxel in this study). The resulting Cartesian coordinates of each pose are calculated as

where r is the voxel radius and are the voxel center coordinates in the robot base frame. Figure 9 visualizes 50 uniformly distributed poses generated around each voxel center.

Figure 9.

Uniformly generated poses at voxel center coordinates: (a) side view and (b) top view.

The Reachability Index (RI) represents the ratio of successfully reachable poses to all generated poses within a voxel and is defined as

where is the number of successful inverse kinematics (IK) solutions and is the total number of generated poses (50 in this study). This metric quantifies the likelihood of the manipulator successfully reaching a target position within the workspace.

3.4.3. Manipulability and Isotropy Calculation

The manipulability index quantifies the kinematic performance of the manipulator by measuring its ability to move in multiple directions from a given configuration [10]. It is derived from the Jacobian matrix J, which defines the relationship between joint velocities and end-effector velocities :

To analyze the kinematic performance, Singular Value Decomposition (SVD) is applied to decompose J as

where contains the singular values , , and , U represents the orthogonal matrix that maps joint space motions to Cartesian directions, while V is the orthogonal matrix describing the principal axes in joint space.

The overall manipulability measure is computed as

Furthermore, the manipulability isotropy index evaluates how uniformly the manipulator can move in all directions and is defined as

A value of 1 indicates isotropic motion (equal dexterity in all directions), while a value approaching 0 signifies a near-singular configuration.

3.4.4. Composite Index and Visualization

A total of 980,100 poses are generated across the workspace, among which 194,700 yielded valid IK solutions. For each voxel, the reachability index, harvestability index, and manipulability isotropy are calculated and combined using weighted coefficients to form a composite score:

Here, denotes the Harvestability Index, representing the probability of successful harvesting at a given pose; is the Manipulability Isotropy, quantifying directional dexterity based on the singular value distribution of the Jacobian; and corresponds to the Reachability Index, indicating the feasibility of achieving an end-effector pose within the robot’s kinematic limits. This weighting emphasizes the importance of successful harvesting (50%) while maintaining a balance between dexterity (30%) and physical reachability(20%).

All computed indices are stored in JSON format, as illustrated in Figure 10.

Figure 10.

Data structure for composite index calculation.

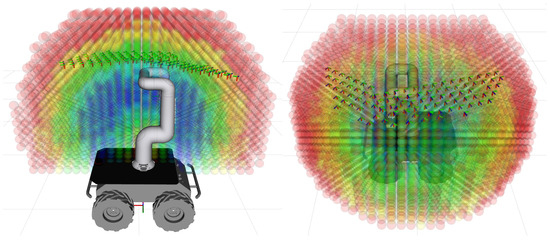

Finally, the composite indices are visualized as a 3D color map to represent the manipulator’s operational capability across the workspace. Color intensity varies from red (low reachability) to blue (high reachability), providing an intuitive visualization of the most efficient regions for harvesting. Figure 11 shows the final reachability map of the robot manipulator.

Figure 11.

Visualization of the reachability map. Blue regions indicate high reachability and dexterity, while red regions represent low reachability.

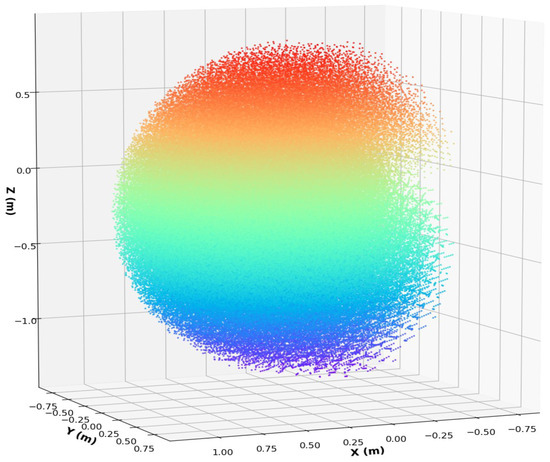

3.4.5. Inverse Reachability Map (IRM)

The Inverse Reachability Map (IRM) is constructed to determine the optimal base poses of the robot manipulator that can reach specific task poses. It is derived from the RM, which defines the feasible task-space poses that the manipulator can achieve. Each reachable pose obtained from the RM is expressed as a six-degree-of-freedom (6-DoF) transformation, represented as

where denotes the position of the Tool Center Point (TCP) relative to the robot base frame and represents its orientation in Euler angles. To compute the IRM, the inverse transformation of each reachable pose is applied to obtain the corresponding base pose that allows the TCP to reach that position and orientation:

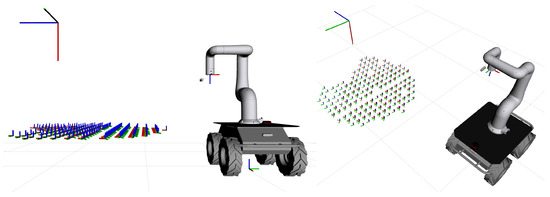

By inverting the transformations, the IRM identifies all feasible base positions and orientations from which the manipulator can successfully reach the target fruit or object. This mapping serves as a key reference for determining the optimal robot placement during harvesting operations. Figure 12 illustrates the visualized inverse reachability map, showing the density of feasible base poses corresponding to reachable task configurations.

Figure 12.

Inverse reachability map representing the feasible base pose set that enables the manipulator to achieve the specified task configurations. The points are colored according to their spatial coordinates to visualize positional distribution; therefore, the color does not indicate reachability performance or manipulability quality. Base pose suitability is instead determined by pose density and convex region structure.

3.5. Selection of the Optimal Base Pose

The base pose selection process aims to compute the optimal robot base position for harvesting fruits that lie outside the manipulator’s reachable workspace. The proposed system first harvests fruits within the manipulator’s reach using the Reachability Map (RM). For fruits that cannot be reached, the system determines an optimal base pose using the Inverse Reachability Map (IRM) and moves the mobile platform to that location, thus extending the harvesting capability.

To systematically evaluate feasible base poses, the harvesting space was voxelized, allowing the robot’s movement range to be discretized into uniform 3D cells. Voxelization enables efficient management of possible base positions and facilitates evaluation of workability at each pose.

Unlike the workspace used in RM generation, the harvesting space was defined over a wider area, centered at a distance of approximately 2 m from the fruit — the range at which the depth camera provides the most stable fruit localization. Figure 13 shows the voxelized harvesting space.

Figure 13.

Voxelized harvesting workspace used for determining feasible base poses for unharvested fruits. Each voxel is color-coded according to its spatial orientation and position to help visualize the overall 3D structure of the reachable workspace. The colors are used solely for geometric visualization and do not represent performance or reachability scores.

3.5.1. Base Pose Calculation Process

The base poses are computed based on the IRM, which represents feasible base configurations from which the manipulator end-effector can reach a given task pose. Given a harvesting pose , all possible base poses are derived by combining it with the IRM transformations as

where represents a candidate base configuration capable of reaching the target fruit.

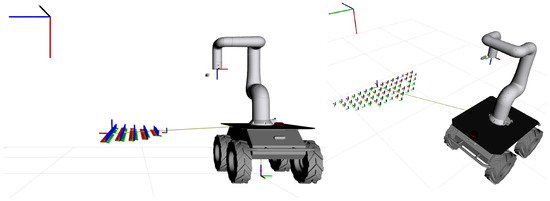

The computed base poses are converted into 3D point clouds and voxelized at the same resolution as the harvesting space. Each voxel’s center is associated with the closest base pose and its corresponding orientation value. Figure 14 and Figure 15 illustrate examples of harvesting poses and the voxelized structure storing rotation values.

Figure 14.

Example of harvesting pose.

Figure 15.

Structure of voxel center coordinates and corresponding rotation values in the harvesting space.

3.5.2. Base Pose Optimization

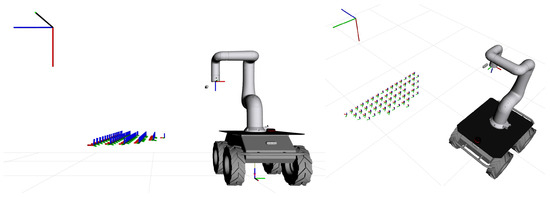

The optimization process selects the most stable and efficient base pose while considering the physical constraints of both the manipulator and the mobile platform. The robot’s vertical motion (z-axis) is limited; thus, the base pose’s z coordinate is constrained within m relative to the manipulator base. This ensures stability by maintaining the working height of the manipulator. Figure 16 shows the distribution of optimal base poses considering this range.

Figure 16.

Optimal base poses considering z-axis range.

Since the mobile platform cannot rotate in roll or pitch, base poses with roll and pitch angles close to are selected, while yaw angles are limited to within to maintain front-facing harvesting orientation. Figure 17 shows the filtered poses satisfying these angular constraints.

Figure 17.

Optimal base poses with roll, pitch, and yaw angle constraints.

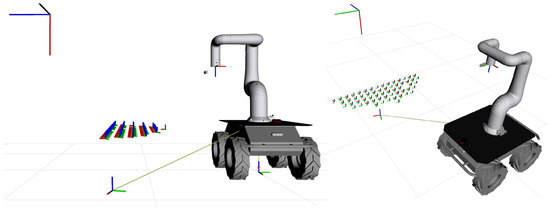

Furthermore, the minimum distance between the manipulator base and the fruit along the x-axis is set to 0.4 m to prevent excessive joint load near the maximum payload limit. This maintains mechanical stability and ensures consistent performance during harvesting. Figure 18 illustrates the filtered base poses satisfying this constraint.

Figure 18.

Optimal base poses with x-axis distance constraint.

3.5.3. Final Base Pose Selection

Filtered base poses are further evaluated using inverse transformation and reachability matching. The inverse transformation process validates whether each filtered base pose can successfully achieve the given harvesting pose:

where denotes the optimized base pose obtained after applying all filtering constraints, is the given harvesting pose of the end-effector, and is the inverse of the filtered IRM transformation corresponding to a feasible base configuration.

Figure 19 and Figure 20 show the inverse transformation process and the mapping between IRM results and the reachability map (RM).

Figure 19.

Inverse transformation process for filtered base coordinates.

Figure 20.

Mapping process of inverse transformation results with the reachability map.

A KD-tree [23] is used to efficiently match each harvesting pose with the nearest voxel in the RM and retrieve its composite reachability score . In addition, a distance-based score is computed as

where is the distance between the manipulator base and the candidate base position and and denote the minimum and maximum distances among all filtered base positions, respectively.

The final integrated score combines the reachability and distance-based scores as

The base pose with the highest is selected as the optimal one, ensuring both high reachability and stable operation. Figure 21 shows the visualized optimal base pose.

Figure 21.

Optimal base poses with final score integration.

To efficiently match each fruit position with the nearest feasible base pose in the IRM, a KD-tree structure is employed to index all IRM voxel centers. The nearest-neighbor query in a balanced KD-tree has a computational complexity of , where N denotes the number of IRM samples. Since one query is required per detected fruit, the total matching cost becomes , with F representing the number of fruits. In our experiments using approximately 200,000 IRM samples and 40–50 fruits, the total KD-tree lookup time remained below 20 ms, demonstrating that the proposed matching method remains efficient even in high-fruit-density environments.

Finally, the selected pose, defined in the manipulator base coordinate frame, is transformed into the mobile robot base frame as

This transformation allows the mobile robot to navigate autonomously to the most suitable position for efficient fruit harvesting. Figure 22 presents the final base pose transformed into the mobile robot coordinate frame.

Figure 22.

Final base pose transformed to the mobile robot base coordinate system.

3.6. Base Position Clustering and Multi-Fruit Harvest Optimization

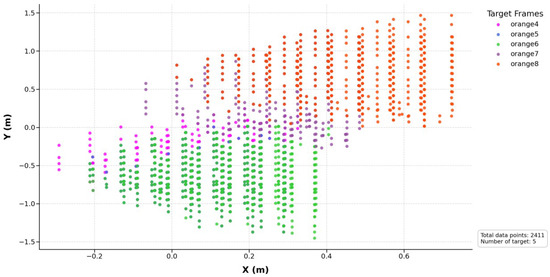

After determining the final base pose, if multiple unharvested fruits remain, moving the mobile robot individually for each fruit is inefficient, as it increases travel time and reduces harvesting efficiency. Figure 23 visualizes all reachable base positions for the unharvested fruits.

Figure 23.

All reachable base positions for unharvested fruits.

For each of these base positions, an optimal pose is computed independently, as shown in Figure 24. However, as seen in the figure, several optimal base poses are located very close to each other. Performing harvesting sequentially at these nearby positions leads to redundant and inefficient motion. Therefore, we propose a method to group base poses for unharvested fruits so that multiple fruits can be harvested in a single movement, thereby improving overall operational efficiency.

Figure 24.

Optimal base poses for each fruit.

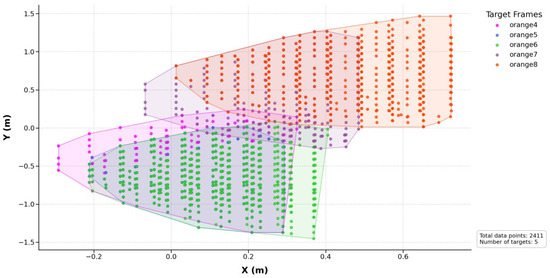

3.6.1. Base Position Clustering Using K-Means

To perform harvesting efficiently, all reachable base positions for each fruit must be effectively clustered. The K-Means clustering algorithm is employed to group reachable base positions for each unharvested fruit. This unsupervised learning method partitions data points into k clusters by iteratively minimizing intra-cluster variance, and the K-Means++ initialization method proposed by Arthur and Vassilvitskii [29] is adopted to improve convergence and clustering stability.

In this paper, k is selected heuristically. It is important to note that K-Means clustering is not applied to the fruit positions themselves, but rather to the candidate base poses generated from the IRM. Since each fruit produces multiple feasible base-pose candidates, clustering is used to spatially group redundant base poses and identify representative positions. This reduces unnecessary repositioning, eliminates duplicated base-pose candidates, and enables efficient path planning during multi-fruit harvesting.

The objective function of K-Means aims to minimize the sum of squared distances between each data point and its corresponding cluster centroid, as defined in Equation (30).

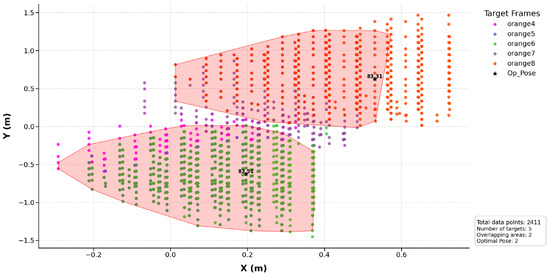

where denotes the i-th position and represents the centroid of the k-th cluster. Each fruit corresponds to one cluster, and the reachable base positions associated with that fruit are grouped accordingly. Figure 25 illustrates the clustering results for each fruit.

Figure 25.

K-means–based clustering of feasible robot base positions for harvesting each target fruit. Each color represents the set of base position candidates from which the manipulator can successfully reach a specific unharvested fruit. The shaded polygon surrounding each cluster corresponds to the convex hull that outlines the spatial boundary of feasible base positions.

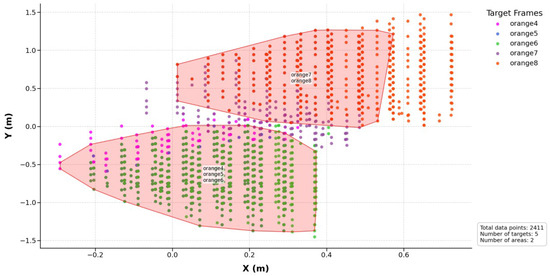

3.6.2. Computation and Filtering of Overlapping Regions

Although each fruit’s base positions are clustered independently, it is essential to identify overlapping regions where multiple fruits can be harvested simultaneously. Delaunay triangulation [30] is applied to analyze geometric relationships between clustered positions. Based on the triangulation, density-based filtering is used to determine overlapping zones. For each base position , the density is computed as the number of nearby positions within a given threshold distance, as shown in Equation (31):

where is the Euclidean distance between positions and , and is an indicator function returning 1 if the condition is satisfied and 0 otherwise.

In this paper, a distance threshold of 0.1 m was used. Regions containing at least 25 base positions and exceeding a minimum convex hull area are considered valid overlapping zones. The maximum group size is limited to four fruits to maintain stable and reliable harvesting. Figure 26 visualizes the identified overlapping regions, enclosed by red convex hulls.

Figure 26.

Optimal base position grouping with overlapping regions. The shaded polygon surrounding each group represents the convex hull that outlines the spatial boundary of these optimal base position clusters.

3.6.3. Computation of Multi-Fruit Harvesting Base Poses

To allow simultaneous harvesting of multiple fruits in overlapping regions, the final base position is determined by combining the distance-based score and the reachability index, following the same optimization framework as described in Section 2.4. Figure 27 shows the final selected optimal base position for multi-fruit harvesting.

Figure 27.

Selection of optimal base position for multi-fruit harvesting.

When multiple fruits are harvested concurrently, individual rotation values computed for each fruit cannot be applied directly. To find a representative orientation for the overlapping region, Principal Component Analysis (PCA) is performed on all quaternions representing rotation values [31]. Each quaternion is expressed as

where denote the rotation axis components and represents the rotation magnitude. The covariance matrix M for n quaternions is calculated as

The eigenvalue decomposition of M yields eigenvectors and eigenvalues , as shown in Equation (34):

The eigenvector corresponding to the largest eigenvalue represents the principal rotation direction and is selected as the optimal quaternion. Figure 28 shows the final optimized base pose incorporating PCA-derived rotation.

Figure 28.

Optimal base pose with PCA-derived rotation for overlapping region.

4. ROS 2-Based Integrated System Design

In this study, a robot harvesting system was designed based on ROS 2 to integrate autonomous navigation, fruit recognition, and harvesting operations. ROS 2 manages communication among distributed nodes, enabling efficient coordination of multiple tasks. Within ROS 2, services and actions are two distinct mechanisms for node-to-node communication. The proposed system utilizes both communication types appropriately to handle asynchronous task execution and real-time feedback exchange.

4.1. Service and Action Structure in ROS 2

A service in ROS 2 consists of a client and a server, following a request–response model. The client sends a task request and the server provides a corresponding response. This model is suitable for short-duration tasks that require immediate responses. In the proposed system, the fruit recognition process was implemented using the service structure. The YOLOv5-based recognition module continuously publishes fruit information through ROS topics and the harvesting server requests the 3D position of detected fruits via a service call whenever needed.

In contrast, a ROS 2 action is designed for long-running tasks and supports bidirectional communication between the client and server. Actions not only transmit goal and result messages but also provide continuous progress feedback and allow cancellation during execution. In the proposed system, actions were employed for both navigation and harvesting operations. During navigation, the robot provides continuous feedback on its position and velocity as it moves toward the goal. Similarly, during harvesting, the action server reports the current status of harvesting progress in real time, allowing the operator to monitor ongoing activities.

4.2. Overall System Workflow

The overall workflow of the proposed system is shown in Figure 29. The central control client manages all tasks in the system. When a user initiates the harvesting process, the central control client first sends a command to the navigation action server. The navigation server moves the robot to the first target tree while continuously providing feedback such as current position and velocity. Once the robot reaches the target location, the navigation server signals task completion, and the control client triggers the harvesting action server.

Figure 29.

Overall workflow of the robot harvesting system.

When harvesting begins, the harvesting action server requests the 3D position of recognized fruits from the fruit recognition service server. Using the reachability map, the server quantitatively evaluates each fruit based on a composite reachability index and proceeds to harvest only those with sufficiently high scores. During harvesting, the system continuously provides feedback to the control client, including the total number of recognized fruits, the number of harvested fruits, and the remaining unharvested ones.

If a fruit has a low reachability score—meaning that the manipulator cannot easily reach it—the harvesting server utilizes the inverse reachability map to compute the optimal base pose for access. However, since the inverse reachability map does not consider obstacles, the calculated base pose might overlap with environmental obstacles. To address this issue, a two-dimensional occupancy grid map is referenced to check whether the computed base pose intersects any obstacle. If the location lies on an obstacle, the corresponding fruit is skipped; otherwise, the mobile robot moves to the new base position to continue the harvesting process.

4.3. Integrated System Configuration

The implemented ROS 2-based integrated system effectively handles navigation, perception, and harvesting tasks asynchronously through the combined use of service and action structures, ensuring real-time feedback and stable operation. Each functional component—navigation, perception, and harvesting—is modularized into independent ROS 2 nodes, facilitating easier maintenance, scalability, and debugging.

Moreover, by incorporating both reachability and inverse reachability maps, the system enables the manipulator to first harvest fruits within reachable areas and then reposition the mobile base to harvest fruits beyond its initial reach. This design allows the system to overcome physical constraints, improve operational efficiency, and achieve adaptive and intelligent harvesting in complex orchard environments.

5. Experimental Results

In this paper, the performance of the fruit harvesting robot system based on the reachability map and inverse reachability map was evaluated through experiments in a virtual farm environment. The efficiency of harvesting was assessed using various combinations of reachability indices to select the optimal map. Based on this selected map, an inverse reachability map was constructed to comprehensively evaluate the performance of the fruit harvesting system.

5.1. Experimental Environment

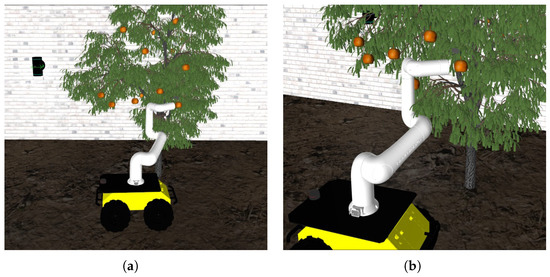

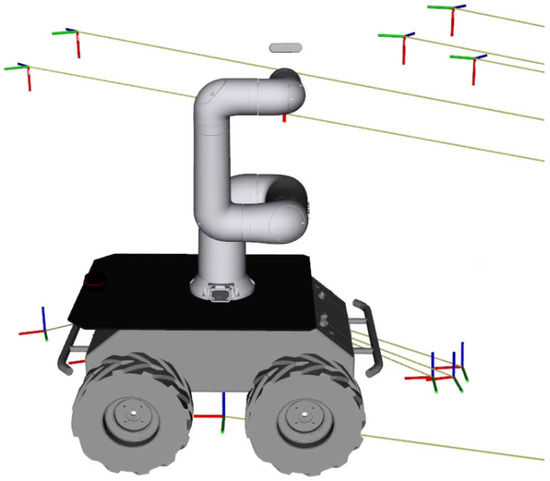

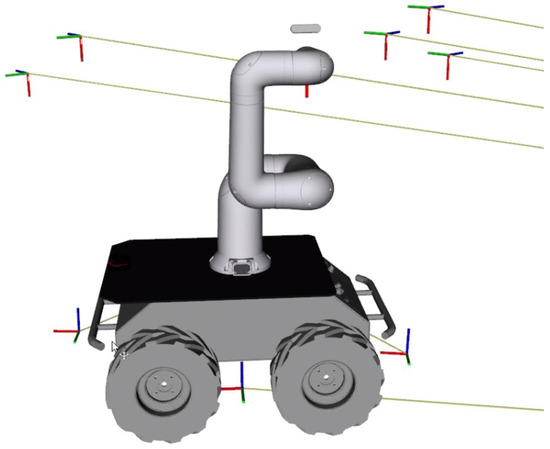

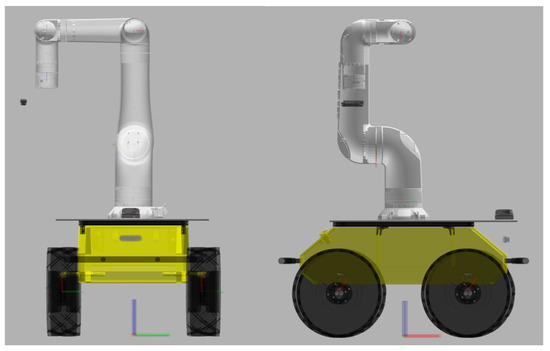

The experiments were conducted in a virtual farm environment built using ROS 2 Humble and Gazebo 11 on the Ubuntu 22.04 operating system. This environment was designed to evaluate the performance of the fruit harvesting robot system, as illustrated in Figure 30.

Figure 30.

Configuration of virtual farm environment.

The robot system was implemented as a mobile manipulator composed of the six-degree-of-freedom manipulator Indy7 (Neuromeka) and the mobile robot Husky (Clearpath Robotics). To perform fruit harvesting operations, the system utilized an Intel Realsense D435i camera, IMU, LiDAR, and wheel encoders. Each sensor was implemented in the virtual environment using Gazebo plugins. The configuration of the robot system is shown in Figure 31. This setup reproduced real agricultural working conditions in a simulated environment, enabling effective performance evaluation of the harvesting system.

Figure 31.

Configuration of the fruit harvesting robot system.

5.2. Evaluation of Basic Harvesting System and Single Index Performance

The basic harvesting system determines whether fruits are harvestable based on whether they are located inside or outside the robot’s workspace, considering only those within the workspace as harvestable targets. Experiments were conducted using the reachability index and manipulability isotropy as individual evaluation criteria to generate separate reachability maps and assess harvesting feasibility.

The reachability index evaluates the physical accessibility of the robot manipulator to a specific position, while the manipulability isotropy reflects the dexterity and motion flexibility of the manipulator when performing harvesting tasks. Table 1 compares the harvesting performance of the basic harvesting system, the system using only the reachability index, and the system using only the manipulability isotropy index. The percentile threshold represents the proportion of the top-scoring voxels in the reachability map that were considered as harvestable regions.

Table 1.

Comparison of harvesting performance between basic system and single index–based system. Successful Harvests (out of 50): number of successful harvest attempts out of 50 trials; Success Rate: ratio of successful attempts; Error Rate: number of failed attempts; Recall and Precision: detection and harvesting accuracy indicators; Time: total harvesting time for 50 attempts.

In the basic harvesting system, the success rate was 66.0%, while the rate of incorrect harvesting attempts was 28.0%. This indicates a limitation of determining harvestability solely based on workspace boundaries, as the robot may include fruits located in areas that are physically difficult to reach as harvestable targets.

When applying the reachability map based on the reachability index, the success rate decreased to 50.0% at the 50th percentile, but the rate of incorrect harvesting attempts dropped to 0%. This reduction is attributed to the fact that only high-score positions were selected for harvesting attempts.

At the 20th percentile, the success rate increased to 66.0%, but the higher number of incorrect attempts led to a decrease in precision. These results demonstrate that when the reachability index alone is used to determine harvestability, it is difficult to maintain a balance between harvesting success rate and precision. In the experiment based on manipulability isotropy, the overall harvesting performance was lower. At the 50th percentile, the success rate dropped to 18.0%, indicating that when harvest targets are selected solely considering manipulability, the harvesting performance can significantly deteriorate.

5.3. Performance Evaluation of Reachability Map Based on Composite Index

In the experiments using the basic harvesting system and single-index-based approaches, each method exhibited clear limitations. To address these shortcomings, a composite reachability map was constructed by comprehensively considering the Harvestability Index, Reachability Index, and Manipulability Isotropy.

The performance of the system was evaluated under different ratio combinations of these indices. Table 2 presents the experimental results for the composite index ratios of 5:3:2, 6:3:1, 4:3:3, and 3:5:2, which represent the respective weighting contributions of the Harvestability Index, Reachability Index, and Manipulability Isotropy. For each ratio combination, the reachability map was assessed using percentile thresholds to determine whether each fruit was considered harvestable. Based on the experimental results, the combination of a 5:3:2 ratio and the 40th percentile exhibited the best overall performance.

Table 2.

Comparison of composite index ratios for reachability map performance.

This configuration achieved both high success and precision rates, with an error rate of 0%, indicating that no incorrect harvesting attempts occurred. These results demonstrate that achieving an appropriate balance among the Harvestability Index, Reachability Index, and Manipulability Isotropy can significantly improve the accuracy and efficiency of fruit harvesting operations. Although the 6:3:1 and 3:5:2 ratios also showed acceptable performance, their success rates were slightly lower than those of the 5:3:2 configuration. In particular, the 6:3:1 combination, despite assigning a higher weight to the Harvestability Index, did not achieve a corresponding improvement in harvesting performance, indicating that increasing the contribution of a single index alone is insufficient for optimal results.

In conclusion, the evaluation of multiple ratio combinations revealed that balancing the contribution of the Harvestability Index while complementarily utilizing the Reachability Index and Manipulability Isotropy is effective in enhancing overall harvesting performance. Notably, the 5:3:2 ratio with the 40th percentile achieved the most stable results, maintaining an excellent balance between harvesting success and error rate.

5.4. Evaluation of Reachability and Inverse Reachability Map Performance

The performance of three harvesting systems—(1) the basic harvesting system, (2) the reachability-map-based system with a composite index, and (3) the inverse-reachability-map-based system—was evaluated and compared. The experiment was conducted in a virtual orchard environment, where the robot sequentially moved between six trees (Tree 1–Tree 6) and harvested the fruits at each location.

The success rate and total operation time were measured for each system. The basic harvesting system determined harvestable fruits based solely on the robot’s workspace, targeting only those located within its reachable boundary. After harvesting all accessible fruits on one tree, the robot proceeded to the next tree and repeated the same procedure.

The reachability-map-based system employed a composite index ratio of 5:3:2 (Harvestability Index:Reachability Index:Manipulability Isotropy). Fruits were selected according to this composite reachability score, and harvesting was performed sequentially from Tree 1 to Tree 6.

In the inverse-reachability-map-based system, harvesting was first conducted based on the reachability map. For fruits that could not be harvested, the inverse reachability map was applied to compute the optimal base pose for each remaining fruit. The robot then repositioned itself to these poses to perform additional harvesting operations, allowing efficient harvesting even for fruits located in difficult-to-reach positions.

Table 3 summarizes the comparative results of the three harvesting systems. The experimental results indicate that the basic harvesting system achieved a success rate of 66.0%, but required 596.06 s to complete the task. This extended duration resulted from inefficient operations when the robot attempted to harvest fruits near the workspace boundaries. The reachability-map-based system, by focusing only on fruits located in regions with high accessibility, improved efficiency and reduced the total time to 413.65 s. However, this improvement came at the cost of a lower success rate (58.0%), as the robot skipped some difficult-to-reach fruits.

Table 3.

Performance comparison of harvesting systems.

6. Conclusions

In this paper, a reachability map–based harvesting system was proposed to achieve autonomous fruit harvesting. The system constructs a reachability map (RM) to pre-select harvestable fruits within the manipulator’s workspace and enables harvesting of fruits located in difficult-to-reach positions. The RM integrates three indices—Harvestability Index, Reachability Index, and Manipulability Isotropy—with a weighting ratio of 5:3:2, allowing quantitative evaluation of feasible harvesting poses.

The constructed RM achieves a recall of 87.9% and a precision of 100%, demonstrating that the robot accurately identifies harvestable fruits while excluding unreachable ones. This reduces unnecessary movements and improves operational efficiency. After harvesting the fruits identified by the RM, the inverse reachability map (IRM) is used to compute optimal base poses for the remaining unharvested fruits. The robot then relocates to these poses, enabling efficient harvesting even for occluded or distant fruits. Additionally, spatial clustering is applied to fruits located in close proximity, allowing multiple fruits to be harvested in a single movement and further reducing travel time.

The proposed system achieves a total harvesting success rate of 90%, confirming the effectiveness of combining RM-based selection, IRM-based base-pose optimization, and clustering-based motion planning for autonomous fruit harvesting.

Future work will focus on extending the system to real-world conditions by incorporating realistic environmental variations such as wind-induced fruit motion, occlusion, and lighting changes. Furthermore, visual servoing will be integrated to compensate for fine fruit movement during grasping. Enhancing fruit detection robustness for visually similar or partially damaged fruits, as well as improving generalization for multiple fruit types, will also be addressed. The transition from simulation to field deployment will include closed-loop navigation, force-adaptive grasping, and real-orchard testing.

Author Contributions

J.-W.H. was primarily responsible for developing the overall concept of the study, implementing the software framework, and conducting all experimental evaluations. J.-H.C. contributed to refining and improving the proposed methodology and participated in the review and editing of the manuscript. Y.-T.K., as the corresponding author, supervised the research, provided overall guidance throughout the project, and contributed significantly to the manuscript’s revision and final editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Korea Institute of Planning and Evaluation for Technology in Food, Agriculture and Forestry (IPET) through the Open Field Smart Agriculture Technology Short-term Advancement Program, funded by the Ministry of Agriculture, Food, and Rural Affairs (MAFRA) (122032-03-1SB010), and by the Smart Convergence Technology Research Center.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Restrictions apply to the datasets. The datasets presented in this article are not readily available due to restrictions imposed by the Korean government, as the data were generated under a government-funded project. Therefore, the data cannot be shared publicly.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Jae-Woong Han was employed by the company Aidin Robotics Inc. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- UN DESA. World Urbanization Prospects: The 2022 Revision. Available online: https://population.un.org/wup/ (accessed on 20 September 2025).

- Statistics Korea. 2023 Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries Census. Available online: https://kostat.go.kr/ (accessed on 20 September 2025).

- Balafoutis, A.T.; Beck, B.; Fountas, S.; Vangeyte, J.; van der Wal, T.; Soto, I.; Gómez-Barbero, M.; Barnes, A.; Eory, V. Smart Farming Technology Trends: Economic and Environmental Effects, Labor Impact and Adoption Readiness. Agronomy 2020, 10, 743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onishi, T.; Kondo, N.; Shigematsu, K. Apple Harvesting Robot Using the SSD Object Detector and Stereo Vision. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2019, 156, 367–377. [Google Scholar]

- Han, J.; Shin, Y. Evaluation of Manipulator Postures for Tomato Harvesting Using Reachability Maps. Biosyst. Eng. 2022, 213, 102–114. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.; Lee, H.; Choi, J. Visual Servo-Based Melon Harvesting Robot with Hemispherical Workspace Analysis. Smart Agric. Robot. 2022, 8, 55–67. [Google Scholar]

- Won, S.-W.; Choe, S.-M.; Lee, H.-A.; Kim, Y.-T. Study on the Design of a Rocker–Bogie Structure Fruit Harvesting Robot. J. Korean Inst. Intell. Syst. 2023, 33, 469–476. (In Korean) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, C.; Frese, U.; Röfer, T. Reachability Maps for Path Planning and Grasping Point Selection. Robot. Auton. Syst. 2012, 60, 675–682. [Google Scholar]

- Burget, F.; Bennewitz, M. Stance Optimization for Humanoid Grasping Tasks Using Reachability Maps. Robot. Auton. Syst. 2015, 70, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Yoshikawa, T. Foundations of Robotics: Analysis and Control; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, H.; Ha, S. Vision-Based Reachability Analysis for Occlusion-Aware Manipulation. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2024, 9, 1184–1191. [Google Scholar]

- Jeong, S.; Park, J.; Lee, D. Inverse Reachability Map Generation for Mobile Manipulators Based on Manipulability Analysis. Robot. Auton. Syst. 2021, 145, 103863. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z. A flexible new technique for camera calibration. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2000, 22, 1330–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onishi, Y.; Ise, N.; Shimizu, S.; Noguchi, N. An Automated Fruit Harvesting Robot by Using Deep Learning. ROBOMECH J. 2019, 6, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, C.; Zhang, X.; Tang, Y.; Zhuang, J.; Tan, Z.; Huang, H.; Chen, W.; Wei, S.; He, Y.; Luo, S. Detection and localization of citrus fruit based on improved You Only Look Once v5s and binocular vision in the orchard. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 972445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Luo, T. A Multi-Fruit Recognition Method for a Fruit-Harvesting Robot Based on Multi-Scale Attention and Hough Localization. Horticulturae 2024, 10, 1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, R.Y.; Lenz, R.K. A new technique for fully autonomous and efficient 3D robotics hand/eye calibration. IEEE Trans. Robot. Autom. 1989, 5, 345–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniilidis, K. Hand–eye calibration using dual quaternions. Int. J. Robot. Res. 1999, 18, 286–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zacharias, F.; Borst, C.; Hirzinger, G. Capturing robot workspace structure: Representing robot capabilities. In Proceedings of the 2007 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, San Diego, CA, USA, 29 October–2 November 2007; pp. 3229–3236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porges, O.; Zacharias, F.; Röder, T.; Borst, C. Reachability and capability analysis for manipulation tasks. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Hong Kong, China, 31 May–7 June 2014; pp. 1288–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stilman, M.; Kuffner, J.J. Navigation among movable obstacles: Real-time reasoning in complex environments. In Proceedings of the IEEE-RAS International Conference on Humanoid Robots, Tsukuba, Japan, 5–7 December 2005; pp. 322–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Li, S.; Liu, Z.; Tao, J.; Yang, S. Inverse reachability mapping and base placement optimization for a mobile fruit-harvesting manipulator. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2021, 189, 106408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentley, J.L. Multidimensional binary search trees used for associative searching. Commun. ACM 1975, 18, 509–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Shen, X.; Chen, H.; Li, G. Recognition and Localization Methods for Vision-Based Harvesting Robots. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, W.; Huang, X.; Wang, S.; He, X. A Comprehensive Review of the Research of the “Eye–Brain–Hand” Harvesting System. Agronomy 2023, 13, 2237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajendran, V.; Debnath, B.; Mghames, S.; Mandil, W.; Parsa, S.; Parsons, S.; Ghalamzan-E., A. Towards autonomous selective harvesting: A review of robot perception, robot design, motion planning and control. J. Field Robot. 2024, 41, 2247–2279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuffner, J.J.; LaValle, S.M. RRT-Connect: An Efficient Approach to Single-Query Path Planning. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), San Francisco, CA, USA, 24–28 April 2000; pp. 995–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makhal, S.S.; Goins, E.R. A Framework for Reachability Map Generation and Analysis for Robot Manipulators. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Mechatronics and Automation (ICMA), Takamatsu, Japan, 6–9 August 2017; pp. 2121–2126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arthur, D.; Vassilvitskii, S. k-means++: The Advantages of Careful Seeding. In Proceedings of the Eighteenth Annual ACM–SIAM Symposium on Discrete Algorithms(SODA 2007), New Orleans, LA, USA, 7–9 January 2007; pp. 1027–1035. [Google Scholar]

- Su, P.; Drysdale, R.L. A Comparison of Sequential Delaunay Triangulation Algorithms. Comput. Geom. 1997, 7, 361–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maćkiewicz, A.; Ratajczak, W. Principal Components Analysis (PCA). Comput. Geosci. 1993, 19, 303–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).