Innovative Farming Technique: The Use of Agricultural Bio-Inputs by Soybean Farmers in Brazil

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

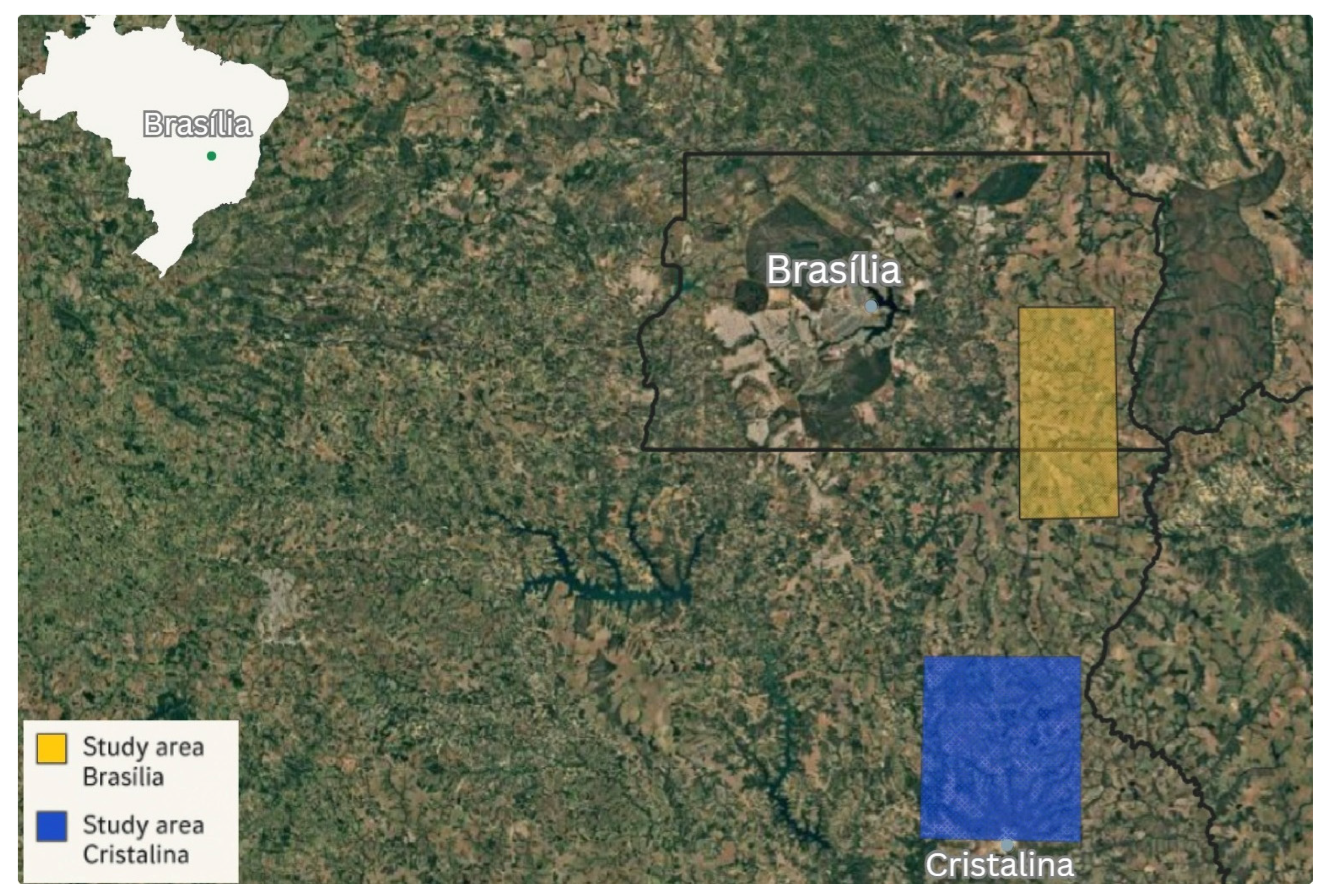

- Federal District (DF)—Area located within the Federal District’s Directed Settlement Program (PAD-DF), including the region adjacent to the Federal District’s border with Goiás. Farmers in this region produce soybean, vegetables, and fruits using advanced technologies, with a focus on high productivity and efficiency.

- Goiás (GO)—Area surrounding the headquarters of the municipality of Cristalina in Goiás, including the Campos Lindos District and the village of São Bartolomeu. Farmers in this region have large-scale properties producing soybeans based on conventional agricultural methods (Figure 1).

3. Results

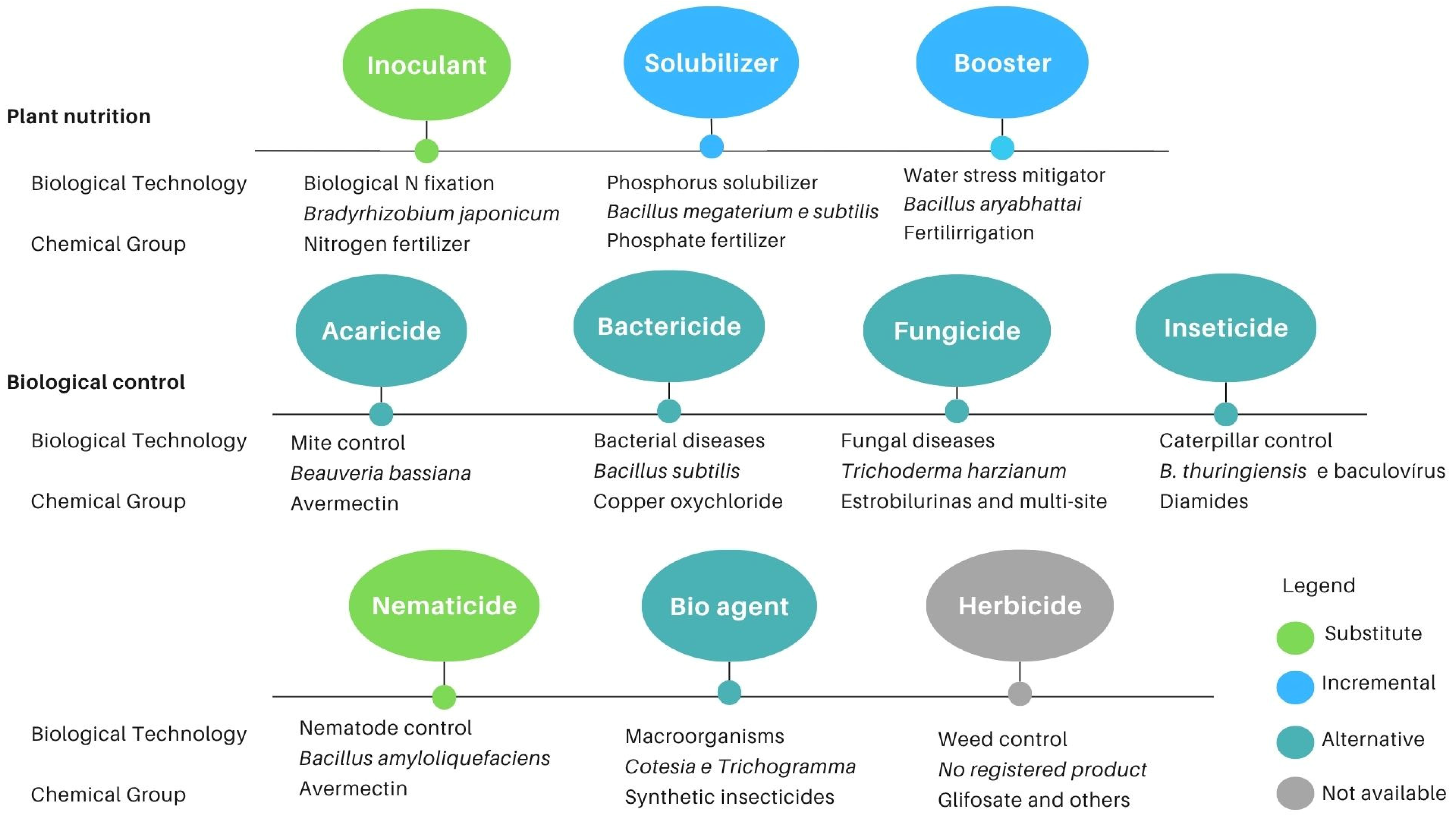

3.1. Biological Solutions for Farming

3.1.1. Plant Nutrition

3.1.2. Biological Control

Control of Mites, Bacteria, Fungi and Insects

Nematode Control Agents

3.1.3. Weed Control

3.2. Adoption of Biological Technologies by Farmers

3.2.1. Plant Nutrition—Phosphorus Biosolubilizers

3.2.2. Biological Control—Bt and Virus

3.2.3. Nematode Control

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mouratidis, A.; Marrero-Díaz, E.; Sánchez-Álvarez, B.; Hernández-Suárez, E.; Messelink, G.J. Preventive releases of phytoseiid and anthocorid predators provided with supplemental food successfully control Scirtothrips in strawberry. BioControl 2023, 68, 603–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, H.; Marcondes de Almeida, J.E.; Limberger, C.; Harakava, R.; Sato, M.E.; Costa, V.A.; Schoeninger, K.; Leite, L.G.; Chacon-Orozco, J.G.; Baldo, F.B. The Rise of Bioinputs in the Brazilian Agri-Industry: Trends, Cases and Hurdles. Outlooks Pest Manag. 2023, 34, 106–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ercole, T.G.; Kava, V.M.; Petters-Vandresen, D.A.L.; Nassif Gomes, M.E.; Aluizio, R.; Ribeiro, R.A.; Hungria, M.; Galli, L.V. Unlocking the growth-promoting and antagonistic power: A comprehensive whole genome study on Bacillus velezensis strains. Gene 2024, 927, 148669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyer, M.; Bueno, A.; Mazaro, S.; Silva, J. Bioinsumos na Cultura da Soja; Embrapa Soja: Londrina, Brazil, 2022; ISBN 9786587380964. [Google Scholar]

- Canellas, L.P.; da Silva, R.M.; Busato, J.G.; Olivares, F.L. Humic substances and plant abiotic stress adaptation. Chem. Biol. Technol. Agric. 2024, 11, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bortoloti, G.; Sampaio, R.M. Desafios e estratégias no desenvolvimento dos bioinsumos para controle biológico no Brasil. Rev. Tecnol. Soc. 2024, 20, 291–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mac Clay, P.; Sellare, J. Value chain transformations in the transition to a sustainable bioeconomy. SSRN Electron. J. 2022, 319, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina, G.; Rotondo, R.; Rodríguez, G.R. Innovations in Agricultural Bio-Inputs: Commercial Products Developed in Argentina and Brazil. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- INPI. Bioinsumos na Agricultura: Inoculantes, 1st ed.; Instituto Nacional da Propriedade Industrial (Brasil)—INPI: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Mckinsey & Company. Mckinsey & Company. Global Farmer Insights 2024. Available online: https://globalfarmerinsights2022.mckinsey.com/ (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Goulet, F. Characterizing alignments in socio-technical transitions. Lessons from agricultural bio-inputs in Brazil. Technol. Soc. 2021, 65, 101580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, T.; Dias, M.F.P. Drivers of the adoption of organic farming in Brazil: A combinatorial analysis. CEPAL Rev. 2024, 2024, 181–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galli, M.; Feldmann, F.; Vogler, U.K.; Kogel, K.-H. Can biocontrol be the game-changer in integrated pest management? A review of definitions, methods and strategies. J. Plant Dis. Prot. 2024, 131, 265–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, L.d.M.; De Moura, J.B.; Lopes Filho, L.C.; Teixeira, M.F.; Peixoto, J.d.C. Bioinputs: A sustainable alternative to traditional pesticide cultivation. Obs. Econ. Latinoam. 2023, 21, 24777–24816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampaio, A.V.; Fluminense, U.F.; Orsi, B. (re)industrialização—Por que tem que ser nova? Bol. Finde 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MAPA. Sipeagro. MAPA (Ministério da Agricultura Pecuária e Abastecimento). Available online: https://mapa-indicadores.agricultura.gov.br/publico/extensions/Fertilizantes/Fertilizantes.html (accessed on 30 December 2024).

- APA. Agrofit—Sistema de Agrotóxicos Fitossanitários. MAPA (Ministério da Agricultura Pecuária e Abastecimento). Available online: https://agrofit.agricultura.gov.br/agrofit_cons/principal_agrofit_cons (accessed on 30 December 2024).

- dos Santos Barros, N.; Barbosa da Silva, E.; Fernandes dos Anjos, A. Segurança hídrica e conflitos pela água no município de Cristalina-Go. Ateliê Geogr. 2023, 17, 196–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IBGE. Censo Agropecuário 2017—Resultados Definitivos. Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística. Available online: https://sidra.ibge.gov.br/pesquisa/censo-agropecuario/censo-agropecuario-2017 (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- ANPII. Estatísticas da Associação Nacional dos Produtores e Importadores de Inoculantes—ANPII. Available online: https://www.anpii.org.br/ (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- de Araujo, F.G.; Teixeira, S.J.C.; de Souza, J.C.; Arieira, C.R.D. Cover crops and biocontrol agents in the management of nematodes in soybean crop. Rev. Caatinga 2023, 36, 243–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira-Paiva, C.A.; Bini, D.; de Sousa, S.M.; Ribeiro, V.P.; dos Santos, F.C.; de Paula Lana, U.G.; de Souza, F.F.; Gomes, E.A.; Marriel, I.E. Inoculation with Bacillus megaterium CNPMS B119 and Bacillus subtilis CNPMS B2084 improve P-acquisition and maize yield in Brazil. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1426166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Godoy, D.N.; Pretto, V.E.; de Almeida, P.G.; Weschenfelder, M.A.G.; Warpechowski, L.F.; Horikoshi, R.J.; Martinelli, S.; Head, G.P.; Bernardi, O. Dose Effects of Flubendiamide and Thiodicarb against Spodoptera Species Developing on Bt and Non-Bt Soybean. Insects 2023, 14, 766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Freitas Soares, F.E.; Ferreira, J.M.; Genier, H.L.A.; Al-Ani, L.K.T.; Aguilar-Marcelino, L. Biological control 2.0: Use of nematophagous fungi enzymes for nematode control. J. Nat. Pestic. Res. 2023, 4, 100025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, C.M.; Almeida, N.O.; Côrtes, M.V.d.C.B.; Júnior, M.L.; da Rocha, M.R.; Ulhoa, C.J. Biological control of Pratylenchus brachyurus with isolates of Trichoderma spp. on soybean. Biol. Control 2021, 152, 104425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontanela, M.L.C.; Miamoto, A.; Rodrigues-Neto, D.A.; Calandrelli, A.; de Silva, M.T.R.; Dias-Arieira, C.R. Chemical control associated with genetic management of Meloidogyne javanica in soybean. Chil. J. Agric. Res. 2024, 84, 281–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokrini, F.; Laasli, S.-E.; Ezrari, S.; Belabess, Z.; Lahlali, R. Plant-Parasitic Nematodes and Microbe Interactions: A Biological Control Perspective. In Sustainable Management of Nematodes in Agriculture; Springer Nature: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024; pp. 89–126. [Google Scholar]

- Berçot, M.R.; Queiroz, P.R.M.; Grynberg, P.; Togawa, R.; Martins, É.S.; Rocha, G.T.; Monnerat, R.G. Distribution and Genetic Diversity of Genes from Brazilian Bacillus thuringiensis Strains Toxic to Agricultural Insect Pests Revealed by Real-Time PCR. Microb. Ecol. 2023, 86, 2515–2526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Productive Axis | Number | Practice |

|---|---|---|

| Plant nutrition | 1 | Seed inoculation |

| 2 | Fertilization | |

| 3 | Plant activators | |

| Biological control of pests and diseases | 4 | Mite control |

| 5 | Bacteria control | |

| 6 | Fungus control | |

| 7 | Insect control | |

| 8 | Nematode control | |

| 9 | Biological control agents (macroorganisms) | |

| Weed control | 10 | Herbicides |

| Product | Company (Headquarters) * | Active Ingredient | Crops | Function |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BiomaPhos | Bioma (Fazenda Rio Grande, PR, Brazil) | Bacillus subtilis (CNPMS B2084 (BRM034840) and Bacillus megaterium CNPMS B119 (BRM033112) | Corn and Soybean | Phosphorus solubilizer |

| SC5 | De Sangose (Pont du Casse, France) | Pseudomonas thivervalensis SC5 | All crops | Multifunction Soil conditioner |

| Hober Phos | Ballagro (Bom Jesus dos Perdões, SP, Brazil) | Pseudomonas fluorescens ATCC 13525 | - | Phosphorus solubilizer |

| Omsugo™ P | Corteva (Indianapolis, IN, USA) | Bacillus subtilis (CNPMS B2084 (BRMO34840)) and Bacillus megaterium (CNPMS B119 (BRMO33112)) | Soybean | Phosphorus solubilizer |

| Omsugo™ ECO | Corteva (Indianapolis, IN, USA) | Bacillus subtilis (CNPMS B2084 (BRMO34840)) and Bacillus megaterium (CNPMS B119 (BRMO33112)) | Sugarcane | Phosphorus solubilizer |

| SolubPHOS | Simbiose (Cruz Alta, RS, Brazil) | BRM 119 (Bacillus megaterium) and BRM 2084 (Bacillus subtilis) | Corn and Soybean | Phosphorus solubilizer |

| Phosbac® | Andermatt (Grossdietwil, Switzerland) | Bacillus amyloliquefaciens (FZB45) | Corn and Soybean | Phosphorus solubilizer |

| Meli-X Turbo | Vittia (São Joaquim da Barra, SP, Brazil) | Bacillus subtilis UFV 3918 | - | Biological nutrient extractor |

| Rhizophos | Rhizobacter (in partnership with Syngenta) (Pergamino, Argentina) | Pseudomonas fluorescens | - | Multifunction/Soil solubilizer |

| JumpStart | Novonesis (Bagsværd, Denmark) | Penicillium bilaiae | - | Phosphorus solubilizer |

| Biofree | Biotrop (Vinhedo, SP, Brazil), now part of the Belgian group BioFirst | Azospirillum brasilense Ab-V6 Pseudomonas fluorescens CCTB03 | - | Phosphorus and nitrogen bioavailability |

| Product | Company (Headquarters) * | Active Ingredient | Biological Target |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acera | Ballagro (Bom Jesus dos Perdões, SP, Brazil) | Bacillus thuringiensis, isolates 1641; Bacillus thuringiensis, isolates 1644 | Chrysodeixis includens/Ecdytolopha aurantiana/Helicoverpa armigera/Plutella xylostella/Spodoptera frugiperda/Tuta absolute |

| Agree | Bio Controle (Indaiatuba, SP, Brazil) | Bacillus thuringiensis aizawai GC-91 | Bonagota salubricola/Cryptoblades gnidiella/Diaphania hyalinata/Diaphania nitidalis/Ecdytolopha aurantiana/Grapholita molesta/Helicoverpa armigera/Neoleucinodes elegantalis/Plutella xylostella/Pseudoplusia includens/Spodoptera frugiperda/Tuta absolute |

| BTControl | Simbiose (Cruz Alta, RS, Brazil) | Bacillus thuringiensis var. kurstaki, strain HD-1 (CCT 1306) | Anticarsia gemmatalis/Chrysodeixis includens/Helicoverpa armigera/Diaphania hyalinata |

| BT Protection | Bioma (Fazenda Rio Grande, PR, Brazil) | Bacillus thuringiensis var. kurstaki, isolated HD-1 (S 1450) | Anticarsia gemmatalis/Chrysodeixis includens/Helicoverpa armigera/Diaphania hyalinata |

| BT/Tec CATP pro remote control | Solubio (Jataí, GO, Brazil) | Bacillus thutingiensis kurstaki, isolate HD-1 (S1450) | Helicoverpa armigera/Plutella xylostella |

| Crystal | Lallemand (in partnership with Embrapa) (Toronto, ON, Canada) | Bacillus thuringiensis subsp. Thoworthy isolated 344 | Spodoptera frugiperda |

| Tarik EC/BT Vale/Cepakill/ QuestBR/BS Beta | Vectorcontrol (Vinhedo, SP, Brazil) | Bacillus thuringiensis, subsp. kurstaki, strain CCT 1306 | Ecdytolopha aurantiana/Erinnyis ello/Helicoverpa armigera/Helicoverpa zea/Plutella xylostella/Spodoptera frugiperda/Thyrinteina arnobia |

| Product | Company (Headquarters) * | Active Ingredient | Biological Target |

|---|---|---|---|

| BaculoMip-SF/Spinix/BioCash/Baculoshock | Promip (Genetics) (Engenheiro Coelho, SP, Brazil) | Spodoptera frugiperda multiple nucleopalyhedrovirus (SfMNPV) | Spodoptera frugiperda |

| Carthusian | Agbitech (Glenvale, Australia) | Spodoptera frugiperda multiple nucleopolyhedrovirus (SfMNPV) | Spodoptera frugiperda |

| Evo diplomat | Koppert (Berkel en Rodenrijs, Netherlands) | Chrysodeixis includes nucleopolyhedrovirus (ChinNPV)/ Helicoverpa armigera Nucleopolyhedrovirus (HearNPV) | Chrysodeixis includens/Helicoverpa armigera |

| Revers | Nitro (São Miguel Paulista, SP, Brazil) | Spodoptera frugiperda multiple nucleopolyhedrovirus (SfMNPV) | Spodoptera frugiperda |

| Surtive | Agbitech (Glenvale, Australia) | ChinNPV Virus/HearNPV Virus | Helicoverpa armigera/Chrysodeixis includens |

| Verpavex | Andermatt (Grossdietwil, Switzerland) | Helicoverpa armigera Nucleopolyhedrovirus (HearNPV) | Helicoverpa armigera |

| VirControl SF | Simbiose (Cruz Alta, RS, Brazil) | Spodoptera frugiperda multiplenucleopolyhedrovirus (SfMNPV) | Spodoptera frugiperda |

| Product | Company (Headquarters) * | Active Ingredient | Biological Target |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nemacontrol | Simbiose (Cruz Alta, RS, Brazil) | Bacillus amyloliquefaciens isolate SIMBI BS 10 (CCT 7600) (bacteria) | Meloidogyne incognita/Meloidogyne exigua/Pratylenchus brachyurus/Heterodera glycines/Slerotinia sclerotiorum |

| Nemat/Nemaouro | Ballagro (Bom Jesus dos Perdões, SP, Brazil) | Paecilomyces lilacinus Isolate Uel Pae 10 (fungus) | Meloidogyne incognita/Meloidogyne javanica/Pratylenchus brachyurus |

| NemaOff/Bionexus/ Volga CI/AgDommon | Massen (Indaiatuba, SP, Brazil) | Bacillus subtilis, strain ATCC 6051; Bacillus licheniformis, strain ATCC 12713; Paecilomyces lilacinus, strain CPQBA 040-11 DRM 10 (bacteria and fungus) | Meloidogyne incognita/Pratylenchus brachyurus |

| Onix OG | Lallemand (Toronto, ON, Canada) | Bacillus methylotrophicus isolate UFPEDA20 (bacteria) | Meloidogyne javanica/Pratylenchus brachyurus |

| Quartz/Surface | FMC Chemistry (Philadelphia, PA, USA) | Bacillus subtilis strain FMCH002 (DSM32155); Bacillus licheniformis strain FMCH001 (bacteria) | Pratylenchus zeae/Meloidogyne exigua/Meloidogyne javanica/Pratylenchus brachyurus/Meloidogyne graminicola/Meloidogyne incognita/ Radopholus similis/Heterodera glycines |

| Summer | Koppert (Berkel en Rodenrijs, The Netherlands) | Bacillus amyloliquefaciens strain UMAF6614 (bacteria) | Meloidogyne incognita/Meloidogyne javanica/Pratylenchus brachyurus |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Medina, G.d.S.; Nascimento, L.C.d.; Stadnik, M.J.; Ramos, M.L.G. Innovative Farming Technique: The Use of Agricultural Bio-Inputs by Soybean Farmers in Brazil. AgriEngineering 2025, 7, 416. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriengineering7120416

Medina GdS, Nascimento LCd, Stadnik MJ, Ramos MLG. Innovative Farming Technique: The Use of Agricultural Bio-Inputs by Soybean Farmers in Brazil. AgriEngineering. 2025; 7(12):416. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriengineering7120416

Chicago/Turabian StyleMedina, Gabriel da Silva, Luciana Cordeiro do Nascimento, Marciel João Stadnik, and Maria Lucrecia Gerosa Ramos. 2025. "Innovative Farming Technique: The Use of Agricultural Bio-Inputs by Soybean Farmers in Brazil" AgriEngineering 7, no. 12: 416. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriengineering7120416

APA StyleMedina, G. d. S., Nascimento, L. C. d., Stadnik, M. J., & Ramos, M. L. G. (2025). Innovative Farming Technique: The Use of Agricultural Bio-Inputs by Soybean Farmers in Brazil. AgriEngineering, 7(12), 416. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriengineering7120416