Abstract

The global poultry industry faces growing challenges from skeletal disorders, with Kinky Back (KB) significantly impacting broiler welfare and production. KB causes spinal deformities that reduce mobility, feed access, and increase mortality. It often remains undetected in early subclinical stages. Traditional KB diagnosis methods are slow and subjective, and highlighting the need for an automated and objective detection. This study develops a machine learning approach for detecting KB in broilers using image data. Male Cobb 500 broilers were raised under controlled conditions and monitored over 7 weeks using overhead 4K video cameras. Behavioral and posture data related to KB were collected and annotated from images extracted from the videos. First, various optimizers (SGD, Adam, AdamW), image sizes, and data augmentation techniques were compared, and the best-performing optimizer, image size, and data augmentation technique were identified. These findings were then used to compare different original lightweight YOLO models trained and to identify the best models with further modifications to these configurations, aiming to improve detection accuracy. Different machine vision models were evaluated using precision, recall, F1-score, and mean average precision metrics to identify the best-performing approach. Among the tested optimizers, SGD achieved the highest precision (100%) and mAP_0.50–0.95 (74.7%), indicating superior localization and lower false-positive rates, while AdamW produced the highest recall (98.9%) with slightly lower precision. Image input size of 960 × 960 pixels yielded the best balance of precision (99.0%), recall (99.4%), and F1-score (99.2%). Data augmentation improved recall and reduced false negatives by confirming its value in enhancing model generalization. Among YOLO architectures, YOLOv9 performs best. Furthermore, the optimized YOLOv9 model, combined with augmentation and 960-sized images, achieved the highest performance, with a precision of 99.1%, recall of 100%, F1-score of 99.5%, and mAP of 78.0%. Overall, the proposed optimized YOLOv9-based system provides a reliable and scalable framework for automated detection of Kinky Back, supporting data-driven welfare management in modern poultry production.

1. Introduction

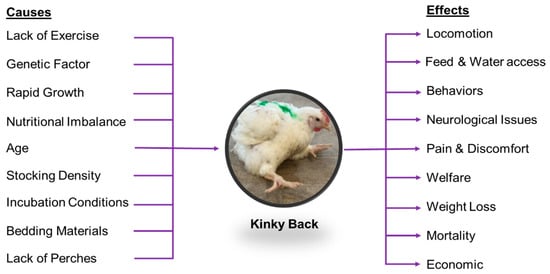

The global poultry industry has experienced significant growth over the past few decades, primarily driven by rising demand for affordable animal protein [1,2]. This surge has been further supported by technological innovations and improved farming techniques that enhance production efficiency. Advances in genetic selection, nutrition, and management practices have contributed to the development of fast-growing broiler chickens [3]. Compared with chicken meat in the 1950s, modern broilers have doubled body mass in half the production time [4]. However, this rapid growth has inadvertently introduced health concerns that negatively affect animal health, productivity, and welfare, including myopathies (woody breast, spaghetti meat) [5,6] and skeletal issues, such as lameness [7,8]. Among skeletal disorders affecting modern broilers, spondylolisthesis is particularly concerning [9]. Spondylolisthesis is a physical disorder that is commonly referred to as a Kinky Back (KB). In addition, KB symptoms can be a manifestation of bacterial infection of the fourth thoracic vertebra (T4), known as spondylitis [10,11,12]. KB has garnered increasing attention due to its impact on broiler welfare and production efficiency (Figure 1). It is characterized by deformities of the thoracic vertebrae, leading to spinal cord compression, gait abnormalities, and, in some cases, paralysis [13]. Affected birds often struggle to access feed and water, contributing to poor performance and increased mortality [14].

Figure 1.

Causal Factors and Effects of Kinky Back in Broilers.

KB was first identified in Great Britain and subsequently reported in countries like Australia, Canada, the USA, and Germany [15,16,17]. It has been recognized as a global concern in the broiler production industry. The condition most frequently affects the fifth and sixth thoracic vertebrae between 3 and 6 weeks of age [9,18,19]. Clinical cases may affect only about 2% of the flock, and up to 60% of birds can be subclinically impacted, experiencing discomfort and mobility issues without visible symptoms [9,17]. This hidden prevalence complicates early intervention, as affected birds often go unnoticed until the condition worsens. In addition, detecting the early subclinical stage is difficult with standard observation methods. Difficulty in early detection underscores the need for advanced diagnostic tools to identify at-risk birds before symptoms progress.

Genetic predisposition is widely acknowledged as a primary factor of spondylolisthesis KB, with notable differences in prevalence across commercial hybrids [17]. Genetic differences influence bone and spinal risks, requiring tailored management. Additionally, dietary factors, such as high-energy and low-fiber diets, have been implicated in exacerbating spinal stress during early growth phases [18]. However, practical limitations often hinder the application of nutritional interventions in commercial systems. Whereas spondylitis KB is highly associated with opportunistic bacteria, particularly Enterococcus. Enterococcal spondylitis leads to a symmetrical hind limb paralysis as a consequence of the Enterococcus cecorum colonization of the free thoracic vertebrae [20,21].

To address the KB condition from both welfare and productivity perspectives, researchers have investigated ways to manage it through environmental enrichment. These approaches focus on promoting movement and strengthening musculoskeletal health [22]. Enrichment tools such as elevated platforms, straw bales, and interactive laser light projections have shown promising results in mitigating the incidence of KB [22]. These tools engage animals in dynamic behaviors, encouraging natural movement and exploration. By promoting increased activity, these strategies help reduce mechanical stress on the developing bones and spine. For instance, perching platforms and laser stimulation have been reported to decrease the prevalence of subclinical spondylolisthesis from as high as 60% to as low as 21% and 29%, respectively [19,22]. While these strategies offer preventive benefits, they are insufficient on their own due to the multifactorial etiology of the condition and the delayed detection of current methods. To address this complexity, integrating proactive monitoring with targeted interventions is essential for optimizing outcomes.

Historically, KB has relied on manual assessment of gait, posture, and activity levels [19,23]. These methods are inherently time-consuming, subjective, inconsistency, and vastly inadequate for identifying subclinical cases. Therefore, there is a critical need for automated tools with real-time detection capabilities and objectivity to identify indicators of the condition. The rise in precision livestock farming presents new opportunities to meet this need. Technologies such as computer vision and sensor-based monitoring pave the way for real-time health assessments [24]. Machine learning offers a powerful approach for analyzing behavioral and physiological data [25,26,27]. It enables accurate and consistent detection of health issues, including musculoskeletal disorders [28,29].

Recent advances in ML applications in livestock systems have demonstrated the utility of convolutional neural networks (CNNs), support vector machines (SVMs), and random forests for health monitoring [30,31,32,33]. In poultry production, these models have successfully identified lameness [34], footpad dermatitis [24], and mortality [35,36] through the image and sensor. Utilizing video footage and time-series data from activity monitoring enables the detection and classification of abnormal patterns [37,38]. However, these technologies have shown promise in other areas. Their application in detecting KB in broilers remains underexplored. Subtle behavioral signs, such as reduced perching, altered posture, or restricted movement, in the early stages can be challenging to notice. Machine learning offers a precise framework for identifying and analyzing these indicators.

This study aims to develop a robust, automated, and scalable machine learning-based approach for detecting KB once its symptoms are present. Detecting KB will help identify increasing cases of KB and facilitate removal, reducing pain and negative impacts on behaviors and welfare. The proposed research will collect image-based data during growth phases, including expert-guided labeling of clinical and subclinical cases, and train multiple machine learning models to assess detection performance. Ultimately, this research aims to develop an improved machine learning model to detect KB and help farmers make timely interventions. By addressing the current limitations in detection, the study has the potential to significantly enhance welfare and health management strategies within commercial poultry operations.

2. Materials and Methods

The materials and methods section clearly outlines how image data were collected, processed, and used to train a model for Kinky Back detection. It details animal housing and management, image collection and processing, data augmentation, the software and hardware used, the architecture, and evaluation metrics.

2.1. Broiler Housing and Management

KB cases were collected during the experimental lameness trial in Fall 2024. These experimental lameness procedures were conducted in accordance with the ethical standards approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at the University of Arkansas (Protocol #23014). The study was conducted over 56 days at the University of Arkansas Poultry Research Farm Complex. A total of 720 male Cobb 500 chicks were randomly distributed into 12 pens. Two pens featured wire flooring as an incubation for lameness diseases, including KB, and ten had litter flooring for study treatments. Each pen initially housed 60 chicks, which were reduced to 50 per pen on day 14 (D14) to maintain an appropriate stocking density. In the last two weeks, we assigned two more pens with 10 broilers each, one of which has a KB for data collection. All pens were identical in size, measuring 1.5 m by 3.0 m.

Environmental conditions within the house were automatically controlled to maintain thermoneutral temperatures appropriate for broiler development. Temperature of 32 °C (90 °F) from days 1 to 3, 31 °C (88 °F) from days 4 to 6, 29 °C (85 °F) from days 7 to 10, 26 °C (80 °F) from days 11 to 14, and 24 °C (75 °F) thereafter. A constant photoperiod of 23 h light and 1 h dark (23L:1D) was maintained throughout the trial. Birds were provided with unrestricted access to clean water and fed industry-standard diets. Broilers receive starter crumbles from day 0 to 21 and grower pellets from day 22 to 56.

2.2. Video Recording and Data Collection

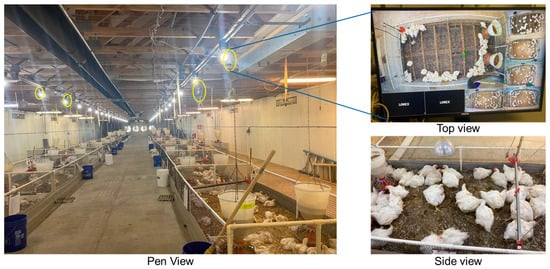

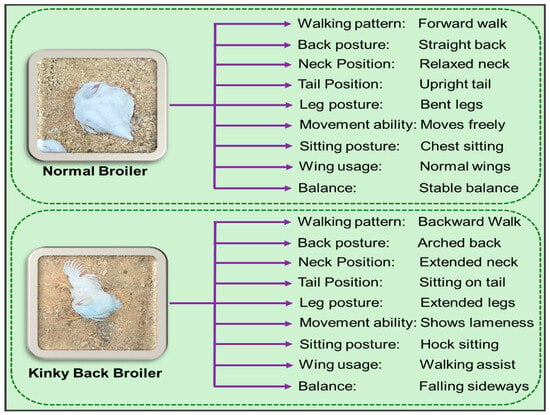

To monitor broiler behavior and detect signs of KB, a continuous video surveillance system was deployed throughout the 7-week trial. In this experiment, the LOREX Pro Series 4K 32-Camera, 8TB Wired NVR System (N884A64B, Lorex Corporation, Columbia, MD, USA) with A14 IP Bullet Cameras (E842CA, Lorex Corporation, Columbia, MD, USA) were used (Figure 2). Overhead cameras were installed in 8 selected pens to capture high-resolution (4K, 20 fps) video footage 24 h a day. From week 3 onward, birds were monitored both via video recording and in person for indicators of KB. This study focused on identifying abnormal postures, including sitting on the back or tail (particularly the “dog-sitting” position), walking backward, reduced mobility, uncoordinated gait, hock-sitting posture with extended legs, frequent sitting or lying, asymmetric leg movement, and difficulty maintaining balance [39,40] (Figure 3). After data collection, birds with KB were humanely euthanized.

Figure 2.

Experimental pen layout and camera setup for data collection.

Figure 3.

Physical differences between normal broiler and Kinky Back broiler.

2.3. Data Annotation and Labeling

The videos were randomly converted to images (2766 × 2082 pixels) using Python 3.13.0 code, and the images were then sorted based on KB presence. The 600-image datasets (5400 regular and 600 KB broiler instances) were split randomly into training (60%), validation (20%), and testing (20%) before labeling. For labeling those images, trained researchers manually annotated the images using Afpha Make Sense (www.makesense.ai, accessed on 1 October 2025). Broilers with KB in each image were labeled using bounding boxes and categorized based on behavioral and physical appearance.

2.4. Machine Learning Model Development

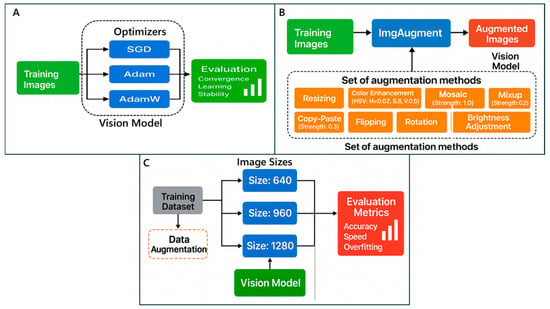

Several open-source deep learning models were initialized in their default configurations to establish baseline performance. Improving model accuracy and robustness required careful selection of optimizers and augmentation techniques during training (Figure 4). This study evaluated various optimizers (Stochastic Gradient Descent, Adam, and AdamW) and augmentation techniques (image size, stronger color, and aggressive augmentations) to determine the most effective combination for improving model performance. These optimizers were used to understand how each optimizer affected convergence, learning stability, and final accuracy [41]. For instance, Adam and AdamW adapt the learning rate during training, potentially improving convergence on complex datasets [42,43], whereas SGD often leads to better generalization [44,45]. In addition, various data augmentation techniques were also applied, including resizing input images (640, 960, 1280), enhancing color variations (hsv_h = 0.02; hsv_s = 0.8; hsv_v = 0.5), and using stronger augmentations such as mosaic, mix-up, flipping, rotation, and brightness adjustment. These augmentations enhance data diversity, enabling the model to generalize more effectively and avoid overfitting [46]. In addition, the reason for using different image sizes is that YOLO models usually use a 640 image size and other arguments by default. Therefore, this study wants to compare the default setting with other settings. Based on prior findings, improved performance is achieved with increased training epochs of 200 and a batch size of 16 [47].

Figure 4.

Modular (A) Optimizer, (B) Data Augmentation, and (C) Image Size Augmentation Framework for Robust Vision Model Training.

Furthermore, this study utilized various small-sized, lightweight YOLO models (YOLOv9s, YOLOv10s, YOLO11s, and YOLO12s) for comparison, identifying the most effective YOLO models [48]. These models were selected for their reduced computational requirements and enhanced accuracy, making them suitable for real-time applications. Each YOLO variant has unique architectural differences, including modifications to backbone, neck, and detection head structures [48]. After evaluating all combinations, the best-performing YOLO model was retrained using the most effective optimizer and augmentation setup to ensure maximum performance. The goal was to identify the most accurate and efficient model for further fine-tuning and deployment. To train these models, the high-performance computing system (Arkansas High Performance Computing Center, Fayetteville, AR, USA) was utilized, with training conducted in Jupyter Notebook 4.2 using NVIDIA A100 GPUs and 64 CPU cores.

2.5. Model Evaluation and Statistical Analysis

Performance metrics, including precision, recall, F1-score, and mean average precision (mAP), were used for evaluation across all experiments [47,48]. Precision quantified the proportion of correctly identified positive detections, while recall measured the model’s ability to detect true positive instances. The F1-score provided a balanced metric combining precision and recall. Mean Average Precision evaluated detection accuracy across varying intersection-over-union (IoU) thresholds. These metrics helped spot common misclassification patterns and compare models. Each YOLO configuration was trained and validated separately with the same dataset split, and results were compared using these metrics. Furthermore, each YOLO variant had its own architecture and optimization strategy, so they were benchmarked independently.

3. Results and Discussions

3.1. Effect of Optimization Parameters and Preprocessing Techniques

3.1.1. Optimization Parameter Comparison

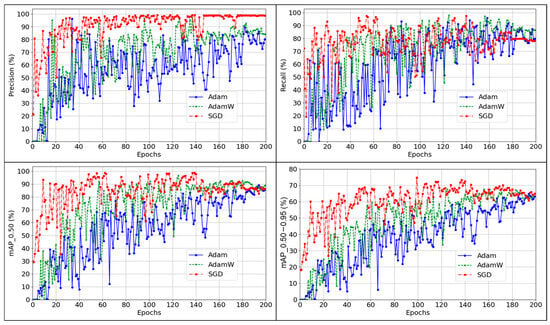

This study compares the performance of three optimizers (Adam, AdamW, and SGD) for detecting KB using a YOLO-based deep learning model. The results showed that SGD performed the best overall as shown in Table 1 and Figure 5. It achieved the highest precision, mAP_0.50, and mAP_0.50–0.95 among the three. While AdamW had slightly higher recall and F1-score, SGD showed stronger overall detection accuracy and localization. High precision means the model made fewer false detections, which is essential in real-time applications. High precision is critical in commercial settings to avoid unnecessary inspections, reduce labor costs, and prevent alert fatigue. A higher mAP_0.50–0.95 also suggests that the model trained with SGD was better at identifying and localizing different variations in the target condition. Previous studies in poultry detection mostly used Adam, AdamW and SGD optimizers [49]. Using SGD reported significantly higher generalization than Adam [49,50]. Figure 4 shows similar results, with the SGD optimizer outperforming the Adam optimizer. The SGD optimizer consistently demonstrated improved performance, whereas other optimizers showed fluctuating trends and less stable convergence. Model performance improves as the number of epochs increases from epoch 0 to 200. This shows the importance of selecting the right optimizer based on the detection goal.

Table 1.

Validation performance of various optimizers for Kinky Back detection (%).

Figure 5.

Comparison of Optimizers’ Performance for Detecting Kinky Back.

A similar trend was observed in the test dataset (Table 2). SGD achieved 100% precision, demonstrating its strong ability to avoid false positives. F1-score was also the highest at 95.6%, confirming its balanced performance. However, the recall was slightly lower at 91.6%, resulting in a higher false-negative rate (FNR) of 8.4%. In comparison, AdamW achieved the highest recall at 98.9% and the lowest FNR of 1.1%, indicating that it was best at detecting all actual cases. Adam had the lowest F1-score at 92.0% and a higher FNR than AdamW. Overall results confirm that SGD is most effective when precision is critical, while AdamW is useful when high recall is required. However, Adam generally provides greater training stability due to its adaptive learning rate and moment estimates.

Table 2.

Performance comparison of optimizers on the test dataset for Kinky Back detection (%).

3.1.2. Evaluation-Based Image Size and Augmentation

This study compares the effect of different image sizes (640, 960, and 1280 pixels) on model performance for detecting KB in broilers. Different image sizes are selected by changing the image size input during model training. The model trained on 960-sized images achieved the best balance between precision, recall, and mAP. Similarly, 960-sized image achieved 98.3% precision, 97.7% recall, 98.7% mAP_0.50, and 76.3% mAP_0.50–0.95, with the highest F1-score of 98.0% (Table 3). This indicates strong detection ability with minimal false positives and negatives. While 1280-sized images yielded a slightly higher mAP_0.50–0.95 of 77.3%, they required more training time and showed a slight drop in precision. Larger sizes slowed inference and increased the risk of overfitting, making them less practical for real-time detection in commercial settings. On the other hand, the 640-sized images trained faster at 14.7 min but had lower recall and F1-score. More training time requires additional computational resources, such as more GPUs, thereby increasing computational costs [51]. Small-sized images train faster with deep learning models than large images [52]. However, large-sized images do not perform as well as medium-sized images. Therefore, the results suggest that using medium-sized images offers the best trade-off between speed and performance without significantly increasing computational cost in real-time systems.

Table 3.

Effect of image size and augmentation on model performance (%) and training time (min) for Kinky Back detection.

In this study, there were fewer KB samples than normal broilers, so we used data augmentation to balance the dataset. Data augmentation methods mitigate overfitting issues in computer vision and machine learning [53]. Therefore, this study also compares the impact of data augmentation on model performance (Table 3). When data augmentation was applied, the model achieved 97.5% precision and 91.6% recall with an F1-score of 94.5% and mAP_0.50–0.95 of 73.2%. Without augmentation, precision remained similar at 98.1%, but recall dropped significantly to 85.7%. The result suggests that augmentation enhanced the model’s ability to generalize, which leads to better detection of true classes. Similar results were observed in the previous study [54]. Data augmentation is effective in tasks like poultry behavior detection and helps models avoid overfitting [27]. These results demonstrate that even small changes from data augmentation can lead to noticeable improvements in recall and overall model robustness.

Table 4 compares the effects of image size and data augmentation on test performance for KB detection using a deep learning model. Among different image sizes, 960 pixels achieved the best results, with a precision of 99.0%, a recall of 99.4%, and the highest F1-score of 99.2%. The performance for both validation and test was higher for image size 960. The 640-pixel size had slightly higher precision (99.4%) but lower recall (93.9%) and a higher FNR of 6.1%. In contrast, 1280 pixels showed lower precision (93.6%) despite achieving a reasonable recall rate (97.8%). These results suggest that 960-pixel images offer the best balance of accuracy and sensitivity without excessive false positives or longer training times. The findings show that image size and augmentation are key to achieving both high precision and recall.

Table 4.

Comparison of image size and augmentation effects on test dataset performance (%) for Kinky Back detection.

3.2. Comparison of YOLO Architectures with Optimized Settings

This study compares several small YOLO model architectures, including YOLOv9, YOLOv10, YOLO11, and YOLO12. Among the base models, YOLOv9 demonstrated high precision (98.1%) but moderate recall (85.7%), with an F1-score of 91.6% (Table 5). YOLO11 had the highest recall at 94.1% and a strong F1-score of 93.6%. However, YOLOv10 and YOLO12 performed slightly lower in both precision and recall. Given the YOLOv9 model’s higher performance, this study focused on further improving It by applying various optimizations and data augmentation techniques based on the above findings.

Table 5.

Validation performance comparison of YOLO architectures and optimized YOLOv9 models with augmentation strategies for Kinky Back detection (%).

The YOLOv9 model, trained with SGD and augmentation, achieved perfect recall (100%) and maintained high precision (97.9%). When combined with 960-pixel image input and augmentation (YOLOv9-Optimized + I960 + Augmentation), the model achieved the highest precision of 99.1%, perfect recall, and the best F1-score of 99.5%, along with an improved mAP_0.50–0.95 of 78.0%. These results highlight that optimization and proper preprocessing can greatly enhance detection accuracy. Overall, YOLO versions that initially showed lower recall or precision benefited from these optimizations.

From Table 6, YOLOv9 achieved 100% precision but a lower recall of 87.7%, resulting in an F1-score of 93.5% and an FNR of 12.3%. Similar trends were observed in YOLOv10 and YOLO12, both of which exhibited high precision but recall rates below 88%. YOLO11 differed by achieving very high recall (99.4%) and a low FNR (0.6%), but its precision dropped to 86.4%. These base models highlight a trade-off between precision and recall, affecting overall detection reliability. Similarly, optimized versions of YOLOv9 were tested with augmentation and an input image size of 960 pixels. These improvements demonstrate that optimization and preprocessing significantly enhance detection balance and reduce the number of missed cases. Our results align with studies that emphasize data augmentation and input size adjustments as key factors for boosting model robustness (Figure 6). This comparison confirms that customized YOLOv9 models provide superior and more reliable detection of KB. Thus, this study successfully developed an improved machine learning model to detect KB, which can help farmers in the future identify KB cases on the farm and develop ways to mitigate them.

Table 6.

Test dataset performance comparison of YOLO architectures and optimized YOLOv9 models for Kinky Back detection (%).

Figure 6.

Prediction results of different models with bounding boxes and confidence scores.

3.3. Limitation and Future Direction

Despite the machine learning model’s promising performance in detecting KB, several limitations were identified. One key challenge is the visual similarity between affected and healthy birds in static images at an early stage. It can lead to misclassifications where subtle deformities are not yet apparent. In addition, the model’s efficacy is constrained by its training on data from specific housing systems. It may limit its applicability to settings such as free-range or enriched cages, where lighting, crowding, and background conditions vary significantly. Moreover, limited datasets are due to fewer KB cases than normal broilers, and a single class may introduce biases related to breed, age, or image quality. Therefore, there is a need for more diverse and robust training samples to mitigate overfitting and enhance reliability in practical applications.

To address these limitations, future research will incorporate video data to capture dynamic movements and behavioral cues. It will help enable more accurate differentiation between KB-affected broilers and healthy ones through temporal analysis. Domain adaptation techniques will be explored to improve model transferability across varied housing systems, facilitating broader deployment in commercial settings. Moreover, integrating behavioral observations with structural assessments could enable early prediction of KB. In addition, associated with lameness issues, potentially through multi-modal approaches that correlate gait patterns, activity levels, and morphological features. These advancements aim to refine precision detection and support proactive welfare interventions in poultry production.

4. Conclusions

This study evaluated the effectiveness of various optimization parameters, preprocessing techniques, and YOLO model architectures for detecting KB. Among the tested optimizers, SGD achieved the highest precision and mAP scores, demonstrating superior localization and reduced false positives. Preprocessing comparisons revealed that using 960-pixel images provided the best trade-off between detection accuracy and computational cost. It achieved the highest F1 Score and the lowest FNR. Data augmentation also significantly improved recall and overall model robustness without increasing training time. Among YOLO architectures, YOLOv9 outperformed other YOLO models. Similarly, by optimizing and using augmented data with a 960-pixel image resolution, YOLOv9’s performance was significantly improved. The optimized YOLOv9 model achieved near-perfect precision, recall, and F1-score. These results show how crucial it is to select the best optimizer, image resolution, augmentation, and fine-tune the model. Together, these choices enable highly accurate and reliable detection of poultry health conditions in real-world applications. Future research will utilize video data for enhanced KB detection and apply domain adaptation to diverse housing systems. It will also integrate behavioral and structural data to predict KB and lameness early, thereby improving accuracy and poultry welfare.

Author Contributions

R.B.B.: Writing—review and editing, Writing—original draft, Investigation, Visualization, Validation, Supervision, Software, Methodology, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Y.T. and C.P.: Writing—review and editing, Conceptualization. A.A., A.D.T.D. and A.A.K.A.: Writing—review and editing, Methodology, Data curation, Investigation. D.W.: Supervision, Writing—review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported and funded by the University of Arkansas Experimental Station and the University of Arkansas College of Engineering, USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture (No: 2023-70442-39232, 2024-67022-42882).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the computational support provided by the Arkansas High Performance Computing Center, which is made possible through multiple National Science Foundation grants and the Arkansas Economic Development Commission. We also used Grammarly to improve grammar and clarity throughout the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that no competing financial interests or personal relationships could have influenced the work presented in this paper.

References

- Mottet, A.; Tempio, G. Global Poultry Production: Current State and Future Outlook and Challenges. Worlds Poult. Sci. J. 2017, 73, 245–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- USDA ERS. Poultry Expected to Continue Leading Global Meat Imports as Demand Rises|Economic Research Service. Available online: https://www.ers.usda.gov/amber-waves/2022/august/poultry-expected-to-continue-leading-global-meat-imports-as-demand-rises (accessed on 21 July 2025).

- Tavárez, M.A.; Solis de los Santos, F. Impact of Genetics and Breeding on Broiler Production Performance: A Look into the Past, Present, and Future of the Industry. Anim. Front. 2016, 6, 37–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuidhof, M.; Schneider, B.; Carney, V.; Korver, D.; Robinson, F. Growth, Efficiency, and Yield of Commercial Broilers from 1957, 1978, and 2005. Poult. Sci. 2014, 93, 2970–2982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petracci, M.; Mudalal, S.; Soglia, F.; Cavani, C. Meat Quality in Fast-Growing Broiler Chickens. Worlds Poult. Sci. J. 2015, 71, 363–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Che, S.; Wang, C.; Iverson, M.; Varga, C.; Barbut, S.; Bienzle, D.; Susta, L. Characteristics of Broiler Chicken Breast Myopathies (Spaghetti Meat, Woody Breast, White Striping) in Ontario, Canada. Poult. Sci. 2022, 101, 101747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lilburn, M.S. Skeletal Growth of Commercial Poultry Species. Poult. Sci. 1994, 73, 897–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; He, Y.; Xu, B.; Lin, L.; Chen, P.; Iqbal, M.K.; Mehmood, K.; Huang, S. Leg Disorders in Broiler Chickens: A Review of Current Knowledge. Anim. Biotechnol. 2023, 34, 5124–5138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wise, D.R. Spondylolisthesis (‘Kinky Back’) in Broiler Chickens. Res. Vet. Sci. 1970, 11, 447–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anthney, A.; Do, A.D.T.; Alrubaye, A.A. Bacterial Chondronecrosis with Osteomyelitis Lameness in Broiler Chickens and Its Implications for Welfare, Meat Safety, and Quality: A Review. Front. Physiol. 2024, 15, 1452318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choppa, V.S.R.; Kim, W.K. A Review on Pathophysiology, and Molecular Mechanisms of Bacterial Chondronecrosis and Osteomyelitis in Commercial Broilers. Biomolecules 2023, 13, 1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wideman, R.F., Jr. Bacterial Chondronecrosis with Osteomyelitis and Lameness in Broilers: A Review. Poult. Sci. 2016, 95, 325–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marzban Abbasabadi, B.; Golshahi, H.; Seifi, S. Pathomorphologial Investigation of Spondylolisthesis Leaded to Spondylosis in Commercial Broiler Chicken with Posterior Paralysis: A Case Study. Vet. Res. Forum 2021, 12, 263–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitchell, R. Broiler Lameness in the United States: An Industry Perspective; Engormix: Córdoba, Argentina, 2014; Volume 175. [Google Scholar]

- Riddell, C.; Howell, J. Spondylolisthesis (‘Kinky Back’) in Broiler Chickens in Western Canada. Avian Dis. 1972, 16, 444–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, M.A.; Olson, N.O.; Weiss, R. Spondylopathy in Broilers: Case Reports. Poult. Sci. 1973, 52, 1847–1852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinev, I. Pathomorphological Investigations on the Incidence of Clinical Spondylolisthesis (Kinky Back) in Different Commercial Broiler Strains. Rev. Med. Vet. 2012, 163, 511–515. [Google Scholar]

- Pompeu, M.; Barbosa, V.; Martins, N.; Baião, N.; Lara, L.; Rocha, J.; Miranda, D. Nutritional Aspects Related to Non-Infectious Diseases in Locomotor System of Broilers. Worlds Poult. Sci. J. 2012, 68, 669–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lourenço da Silva, M.I.; Leonie, J. Kinky Back (Spondylolisthesis) in Broiler Chickens: What We Can Do Today to Reduce the Problem; VCE Publications: Blacksburg, VA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Robbins, K.M.; Suyemoto, M.M.; Lyman, R.L.; Martin, M.P.; Barnes, H.J.; Borst, L.B. An Outbreak and Source Investigation of Enterococcal Spondylitis in Broilers Caused by Enterococcus cecorum. Avian Dis. 2012, 56, 768–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borst, L.; Suyemoto, M.; Sarsour, A.; Harris, M.; Martin, M.; Strickland, J.; Oviedo, E.; Barnes, H. Pathogenesis of Enterococcal Spondylitis Caused by Enterococcus cecorum in Broiler Chickens. Vet. Pathol. 2017, 54, 61–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lourenço da Silva, M.I.; de Lima Almeida Paz, I.C.; Jacinto, A.S.; Nascimento Filho, M.A.; de Oliveira, A.B.S.; dos Santos, I.G.A.; dos Santos Mota, F.; Caldara, F.R.; Jacobs, L. Providing Environmental Enrichments Can Reduce Subclinical Spondylolisthesis Prevalence without Affecting Performance in Broiler Chickens. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0284087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anthney, A. Bacterial Chondronecrosis with Osteomyelitis in Broiler Chickens: Experimental Lameness and Additive Probiotic Treatments. Master’s Thesis, University of Arkansas, Fayetteville, AR, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Bist, R.B.; Yang, X.; Subedi, S.; Bist, K.; Paneru, B.; Li, G.; Chai, L. An Automatic Method for Scoring Poultry Footpad Dermatitis with Deep Learning and Thermal Imaging. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2024, 226, 109481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derakhshani, S.M.; Overduin, M.; van Niekerk, T.G.; Groot Koerkamp, P.W. Implementation of Inertia Sensor and Machine Learning Technologies for Analyzing the Behavior of Individual Laying Hens. Animals 2022, 12, 536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manikandan, V.; Neethirajan, S. Decoding Poultry Welfare from Sound—A Machine Learning Framework for Non-Invasive Acoustic Monitoring. Sensors 2025, 25, 2912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subedi, S.; Bist, R.B.; Yang, X.; Li, G.; Chai, L. Advanced Deep Learning Methods for Multiple Behavior Classification of Cage-Free Laying Hens. AgriEngineering 2025, 7, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dayan, J.; Goldman, N.; Waiger, D.; Melkman-Zehavi, T.; Halevy, O.; Uni, Z. A Deep Learning-Based Automated Image Analysis for Histological Evaluation of Broiler Pectoral Muscle. Poult. Sci. 2023, 102, 102792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marzoque, H.J.; de Alencar Nääs, I.; Marzoque, G.A.; do Carmo, M.; de Alencar, B.; Batista, M.L. Design of an Application for Analysing the Progression of Musculoskeletal Diseases in Slaughterhouses. In Proceedings of the XL CIOSTA & CIGR Section V International Conference, Évora, Portugal, 10–13 September 2023; Volume 158. [Google Scholar]

- Brossard, L.; Quiniou, N.; Marcon, M.; Méda, B.; Dusart, L.; Lopez, V.; Dourmad, J.-Y.; Pomar, J. Development of a Decision Support System for Precision Feeding Application in Pigs and Poultry; HAL: Lyon, France, 2017; Volume 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kader, M.S.; Ahmed, F.; Akter, J. Machine Learning Techniques to Precaution of Emerging Disease in the Poultry Industry. In Proceedings of the 2021 24th International Conference on Computer and Information Technology (ICCIT), Dhaka, Bangladesh, 18–20 December 2021; IEEE: Dhaka, Bangladesh, 2021; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, X.; Bist, R.B.; Paneru, B.; Chai, L. Deep Learning Methods for Tracking the Locomotion of Individual Chickens. Animals 2024, 14, 911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pallerla, C.; Feng, Y.; Owens, C.M.; Bist, R.B.; Mahmoudi, S.; Sohrabipour, P.; Davar, A.; Wang, D. Neural Network Architecture Search Enabled Wide-Deep Learning (NAS-WD) for Spatially Heterogenous Property Awared Chicken Woody Breast Classification and Hardness Regression. Artif. Intell. Agric. 2024, 14, 73–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasiri, A.; Yoder, J.; Zhao, Y.; Hawkins, S.; Prado, M.; Gan, H. Pose Estimation-Based Lameness Recognition in Broiler Using CNN-LSTM Network. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2022, 197, 106931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, Y.; Lu, H.; Zhao, Q.; Yang, Z.; Xu, W. Detection System of Dead and Sick Chickens in Large Scale Farms Based on Artificial Intelligence. Math. Biosci. Eng. 2021, 18, 6117–6135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bist, R.B.; Subedi, S.; Yang, X.; Chai, L. Automatic Detection of Cage-Free Dead Hens with Deep Learning Methods. AgriEngineering 2023, 5, 1020–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Zhao, Y.; Gan, H.; Hawkins, S.; Eckelkamp, L.; Prado, M.; Burns, R.; Purswell, J.; Tabler, T. Modeling Gait Score of Broiler Chicken via Production and Behavioral Data. Animal 2023, 17, 100692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaihuni, M.; Zhao, Y.; Gan, H.; Tabler, T.; Qi, H. Automated Broiler Mobility Evaluation Through DL and ML Models: An Alternative Approach to Manual Gait Assessment. AgriEngineering 2025, 7, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makrai, L.; Nemes, C.; Simon, A.; Ivanics, E.; Dudás, Z.; Fodor, L.; Glávits, R. Association of Enterococcus cecorum with Vertebral Osteomyelitis and Spondylolisthesis in Broiler Parent Chicks. Acta Vet. Hung. 2011, 59, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asnayanti, A.; Do, A.D.T.; Alharbi, K.; Alrubaye, A. Inducing Experimental Bacterial Chondronecrosis with Osteomyelitis Lameness in Broiler Chickens Using Aerosol Transmission Model. Poult. Sci. 2024, 103, 103460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassan, E.; Shams, M.Y.; Hikal, N.A.; Elmougy, S. The Effect of Choosing Optimizer Algorithms to Improve Computer Vision Tasks: A Comparative Study. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2023, 82, 16591–16633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tong, Q.; Liang, G.; Bi, J. Calibrating the Adaptive Learning Rate to Improve Convergence of ADAM. Neurocomputing 2022, 481, 333–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, P.; Xie, X.; Lin, Z.; Yan, S. Towards Understanding Convergence and Generalization of AdamW. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2024, 46, 6486–6493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amir, I.; Koren, T.; Livni, R. SGD Generalizes Better than GD (and Regularization Doesn’t Help). Proc. Mach. Learn. Res. 2021, 134, 63–92. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, A.; Ramanath, R.; Shi, J.; Keerthi, S.S. Adam vs. Sgd: Closing the Generalization Gap on Image Classification; LinkedIn: Sunnyvale, CA, USA, 2021; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Rebuffi, S.-A.; Gowal, S.; Calian, D.A.; Stimberg, F.; Wiles, O.; Mann, T.A. Data Augmentation Can Improve Robustness. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2021, 34, 29935–29948. [Google Scholar]

- Bist, R.B.; Subedi, S.; Yang, X.; Chai, L. A Novel YOLOv6 Object Detector for Monitoring Piling Behavior of Cage-Free Laying Hens. AgriEngineering 2023, 5, 905–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ultralytics Models Supported by Ultralytics. Available online: https://docs.ultralytics.com/models (accessed on 28 December 2024).

- Liu, D.; Wang, B.; Peng, L.; Wang, H.; Wang, Y.; Pan, Y. HSDNet: A Poultry Farming Model Based on Few-Shot Semantic Segmentation Addressing Non-Smooth and Unbalanced Convergence. PeerJ Comput. Sci. 2024, 10, e2080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, P.; Feng, J.; Ma, C.; Xiong, C.; Hoi, S.; E, W. Towards Theoretically Understanding Why SGD Generalizes Better Than Adam in Deep Learning. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2010.05627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subedi, S.; Bist, R.; Yang, X.; Chai, L. Tracking Pecking Behaviors and Damages of Cage-Free Laying Hens with Machine Vision Technologies. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2023, 204, 107545. [Google Scholar]

- Saponara, S.; Elhanashi, A. Impact of Image Resizing on Deep Learning Detectors for Training Time and Model Performance. In Proceedings of the Applications in Electronics Pervading Industry, Environment and Society; Saponara, S., De Gloria, A., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 10–17. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, T.; Brennan, R.; Mileo, A.; Bendechache, M. Image Data Augmentation Approaches: A Comprehensive Survey and Future Directions. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 187536–187571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poojary, R.; Raina, R.; Kumar Mondal, A. Effect of Data-Augmentation on Fine-Tuned CNN Model Performance. IAES Int. J. Artif. Intell. 2021, 10, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).