Abstract

Chemical defoliation is an important management practice in cotton to facilitate mechanical harvesting and leaf removal and maintain lint quality. Recent advances in precision agriculture have enabled the development of autonomous robotic platforms with a targeted side-spraying system that can achieve good canopy penetration while preventing soil compaction and crop mechanical damage. A side-wise spraying system allows for application of defoliant at different canopy heights. However, information on the effects of staggered defoliation on cotton fiber quality is limited. Thus, field research was conducted to evaluate the effects of various staggered application timing intervals (15, 10, 8, 5, and 3 days) on fiber quality and compare them with standard over-the-top broadcast applications. Staggered defoliation affected fiber length, with significant differences observed for upper half mean length, fiber length based on weight, and upper quartile length. Fiber maturity was also influenced by staggered defoliation timing, with a 15-day interval resulting in the lowest micronaire and higher immature fiber content. The effects of staggered defoliation on other parameters, such as strength, uniformity, and trash characteristics, varied across locations. The findings highlight the potential of robotic systems for chemical spraying and emphasize the need for further research on more precise and targeted application of defoliants to improve fiber quality.

1. Introduction

Cotton (Gossypium spp.) is a tropical shrub belonging to the Malvaceae family with erect branching stems, alternate leaves, large white to reddish-purple flowers, and a capsule-like fruit [1]. Cotton is primarily grown for its spinnable fiber on the seed coat. These fibers begin as elongated outward-growing cells on the ovule surface, which deposit cellulose in a helical pattern. Upon maturation, the protoplast dies, leaving behind a pure cellulosic cell wall that collapses inward to form a convoluted ribbon [2].

Cotton is the most important natural textile fiber, accounting for 90% of natural fiber production [3]. The United States (US) is the third-largest producer of cotton in the world after China and India [4]. Two main varieties cultivated in the US are Upland (Gossypium hirsutum) and Pima (G. barbadense). Upland accounts for 97% of US cotton production [5]. Cotton is predominantly grown in the following US states: Alabama, Arkansas, Arizona, California, Florida, Georgia, Kansas, Louisiana, Mississippi, Missouri, New Mexico, North Carolina, Oklahoma, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, and Virginia [5]. Cotton is one of the major row crops grown in South Carolina. It was planted at 91,054 hectares, yielding 396,000 bales (218 kg per bale), with an average yield of 964 kg per hectare in 2024. This generated USD 120.96 million in revenue [6]. The quality of fibers is an essential aspect in cotton production for both farmers and the textile industry. High-quality fibers provide a competitive market advantage and an opportunity to increase profitability for farmers. Poor fiber quality results in challenges during processing, reduces the quality of the final product, and causes economic losses to producers and manufacturers [7,8,9].

Leaf shedding in cotton is a natural process as the plant matures; however, this process does not synchronize with harvest timing. Therefore, harvest aid chemicals are used to remove leaves, which are the primary source of stains and trash [10]. Additionally, defoliation helps to facilitate the mechanical harvesting of cotton bolls, maintain lint quality, manage maturity for timely harvest, and reduce the potential of boll rot [11]. Even with the application of defoliants, the interaction of plant, weather, chemicals, and application factors can result in inconsistencies after defoliation [12]. Incomplete defoliation of the leaves increases trash content and causes lint staining, decreasing fiber quality and, consequently, its value [13,14]. Although harvest aids have been used for over 40 years, obtaining satisfactory leaf removal is still problematic [12]. Extensive research efforts have targeted improving defoliation uniformity, effectiveness, and timing to optimize harvest outcomes. These include understanding the physiology of cotton defoliation [15], the influence of plant characteristics on defoliation [13], the effectiveness of different defoliants [16], the optimum timing of defoliation [17,18,19,20,21], enhancing sprayer configurations [22], and optimizing the spraying parameters [23]. Cotton defoliants are traditionally applied using a tractor-mounted or self-driving sprayer rig with nozzles arranged on a linear boom above the crop canopy [24]. However, ground-based sprayers can cause mechanical damage to the plants through incidental contact, resulting in loss of mature cotton bolls, lodging of the main stems, and an increase in soil compaction in the drive rows [25,26]. With the development of precision technology, unmanned aerial vehicles used for chemical spraying in agriculture are also gaining popularity [25]. Research has focused on the utility of unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) for spraying harvest aid [26], comparing the efficacy of UAV spraying with ground-based sprayer [25], improving the operational parameters (height, volume, and droplet size) of defoliants [27], using aviation spray adjuvants [28], collecting remotely sensed images to determine defoliation rate and develop prescription maps [29], and establishing variable application rates of defoliation products [30,31]. However, the challenges related to inadequate penetration and distribution at the lower canopy [27] and spray drift persists in UAV spray systems [24]. Defoliant success is contingent on the contact of the chemical defoliant with the leaf because contact defoliants do not move within the plant [10,12]. While UAVs offer advantages in accessibility, their limited droplet penetration in lower canopies remains a challenge, motivating exploration of ground-based robotic alternatives.

Cotton cultivation requires various management practices, such as applying growth regulators and harvest aid chemicals, which presents an opportunity for using robotic systems and automation in cotton production systems [32]. However, there is limited research on using unmanned ground vehicles for defoliant applications. Neupane et al. [33] showed the efficacy of an unmanned ground vehicle equipped with a specialized spraying system which applied defoliants from the side of the plant canopy. This study demonstrated the potential of side-wise spraying for effective chemical penetration and subsequent defoliation. Maja et al. [34] also observed, using multivariate principal component analysis, that a 40% duty cycle was the optimum in balancing effective defoliation and fiber quality. With a robotic system that is capable of side-wise spraying, defoliants can be applied sequentially to the bottom canopy prior to the middle and top canopy to achieve staggered defoliation. Bottom leaves mature early in the season and contribute less to the development of bolls in the upper canopy. Thus, defoliation of the bottom leaves does not impact the growth and development of immature bolls in the upper canopy [35]. Staggered defoliation can alter the source–sink relations within the cotton plant and improve the overall fiber quality characteristics, especially for the bolls in the top canopy. Previous studies have reported intra-plant variability in fiber quality, where fibers harvested from the top canopy tend to be poor in quality [36,37,38]. Historically, Brown [35] used hand-spraying and a Hahn Hi-Boy clearance rig to defoliate the bottom of the cotton canopy in Arizona. The research demonstrated that bottom defoliation resulted in an effective leaf drop and increased boll opening, which allowed for an earlier harvest without any detrimental effect on lint quality. However, no studies have evaluated staggered defoliation using autonomous robotic platforms in modern cotton cultivars.

Fiber quality is important because it determines product value, processing and end-use quality [39]. Cotton fiber quality is determined using High-Volume Instrument (HVI) and Advanced Fiber Information Systems (AFIS). The quality traits measured by HVI include length, uniformity, strength, micronaire, short fiber content, yellowness, and reflectance [27]. The HVI evaluates multiple fiber characteristics from a bundle of fibers at a relatively high speed. In contrast, an AFIS measures several properties, including length and maturity of the individual fiber, using an infrared beam a nd electro-optical technology [40]. HVI and AFIS have been extensively used to evaluate variability among cultivars [41], the effects of defoliation timing [42,43,44,45] and planting date [46,47] on cotton fiber quality. The studies by Neupane et al. (2023) [33] and Maja et al. (2024) [34] used HVI and AFIS to evaluate fiber quality following autonomous robotic spraying; however, they were limited to one-time application of chemical defoliants. As such, no study thus far has evaluated the effect of staggered defoliation using autonomous robotic spraying systems on cotton fiber quality. In addition to this, there is no information on appropriate intervals for application between the bottom, middle, and top levels of the canopy to achieve staggered defoliation. Therefore, this study evaluated the effects of different staggered defoliation timings (15, 10, 8, 5, and 3 days) on fiber quality parameters and compared them to conventional over-the-top broadcast defoliation. Given these knowledge gaps, this study aimed to evaluate staggered defoliation timing using an autonomous side-spray robotic platform. We hypothesized that the staggered application—with timing intervals between bottom, middle, and top canopy defoliation—using an autonomous robotic spraying system could improve fiber quality compared to conventional defoliation practices.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Parameters

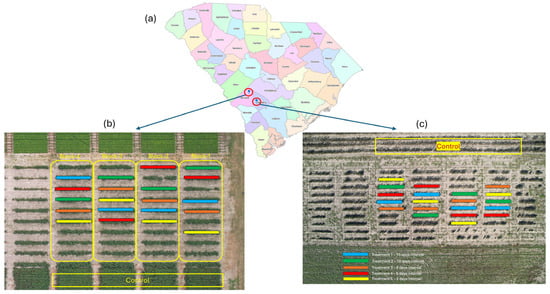

The field experiment was conducted at two sites, the Clemson University Edisto Research and Education Center in Blackville (33.346 N, 81.318 W) and the South Carolina State University Research and Demonstration Farm in Olar (33.160 N, 81.135 W), in 2024 (Figure 1). Two separate locations, Edisto Research and Education Center (EREC) and South Carolina State University Research and Demonstration Farm (SCSRDF), were chosen to capture variability in environmental conditions, particularly differences in soil type, planting dates, microclimates, and growing season duration. Utilizing multiple sites allows for a broader assessment of how staggered defoliation practices influence fiber quality across diverse cotton production environments, ensuring that the findings are robust and widely applicable. The cotton variety Deltapine ‘DP 2127 B3XF’ was planted at both locations at 10 seeds per row meter and at a depth of 1.3 cm. DP 2127 B3XF is an early–mid-maturing variety, with approximately ten fruiting nodes, smooth leaf pubescence, and an open canopy. It is a medium-to-tall plant type and requires timely harvest aid application to optimize micronaire. The micronaire, fiber length, uniformity, and strength are 4.7, 29.21 mm, 83.9%, and 30.4 gtex−1, respectively [48]. The cotton was planted in a 1:1 skip row pattern with 193 cm between the rows. This wide spacing facilitated movement of the autonomous mobile robotic platform and sprayer, while control plots were planted with a standard row spacing of 97 cm. Other management practices, such as irrigation, fertilizer application, regulation of plant growth, and weed management during the season, were based on the South Carolina Cotton Growers’ Guide [28]. At EREC, cotton was planted on 21 May 2024, with treatment rows measuring 12 m in length. Cotton in the SCSRDF site was planted on 14 June 2024, with rows that were 6.1 m long. Since SCSRDF was planted later, the cotton plants were shorter, with less branching at the end of the season compared to EREC.

Figure 1.

(a) Map of South Carolina showing the locations of Edisto Research and Education (EREC) and South Carolina State Research and Demonstration Field (SCSRDF) sites. (b) Detailed layout of EREC, showing the treatment plots (marked in blue, green, orange, red, and yellow) and control plots. (c) Detailed layout of SCSRDF, illustrating the treatment plots (marked in blue, green, orange, red, and yellow) and control plots.

The experimental design was a randomized complete block design with five staggered defoliation treatments and four replications. A control or grower standard broadcast defoliation timing was included as a comparison. Treatments 1 through 5 involved sequential defoliant applications to the bottom, middle, and top canopy at intervals of 15, 10, 8, 5, and 3 days, respectively. Treatment 1 represented the earliest schedule, with a 15-day interval between applications to successive canopy layers, whereas Treatment 5 used the shortest interval (3 days). Intervals longer than 15 days would result in premature defoliation before lower bolls had matured, while intervals shorter than 3 days would not allow sufficient time for effective leaf drop between applications. Therefore, the interval between successive defoliation was set between 15 and 3 days. In control plots, a single application of the defoliant mixture was applied to the entire canopy. The defoliation schedule (see Appendix A) was arranged so that the top canopy application of all treatments occurred at the same time as the control application. This timing aligned with approximately 60% boll opening, which occurred approximately 150 days after planting in EREC. At SCSDF, top defoliation and control applications were completed around 170 days after planting due to a later planting date. A tank mixture of tribufos (Folex 6 EC, Bayer CropScience, St. Louis, MO, USA), ethephon (Setup 6 SL, Adama, Raleigh, NC, USA), and thidiazuron (Freefall 4 SC, NuFarm, Alsip, IL, USA) were applied at 0.84 kg ha−1, 1.68 kg ha−1, and 0.11 kg ha−1, respectively, at the corresponding timings for defoliation based on South Carolina cotton grower’s guide [12]. In the mixture, tribufos results in leaf drop, ethephon aids in boll opening, and thidiazuron helps to inhibit additional regrowth. The operating parameters for staggered defoliation and control broadcast defoliation are provided in Appendix A.2.

2.2. Sprayer Setup

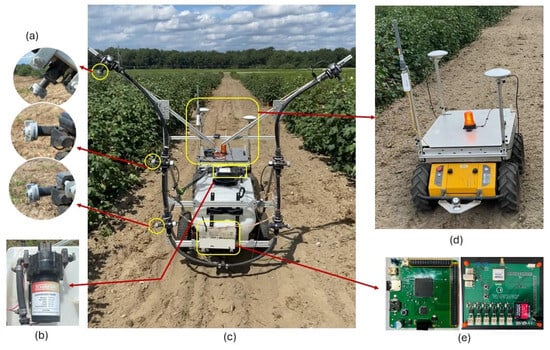

Defoliant treatments were applied using a sprayer unit attached to an autonomous mobile platform. The mobile platform was a Husky A200 from Clearpath Robotics (Kitchener, ON, Canada). It was selected due to its lightweight design and capability to carry payloads of up to 75 kg at operational speeds of 1 m/s (Figure 2d). The robot is equipped with an Inertial Measuring Unit (IMU), Global Positioning System (GPS), laser scanner, steering motors, and encoders for obstacle detection and navigation in the field. The sprayer unit (Model #1598042, County Line, Austin, TX, USA) had a 94 L tank equipped with a 12 V diaphragm pump (Figure 2b) and could deliver 9.5 L/min at a pressure of 482 kPa (Figure 2c). The sprayer was fitted with six nozzles. Each nozzle body was equipped with an ER110-06 spray tip (Wilger Industries, Saskatoon, SK, Canada), a conventional flat fan nozzle which produces a fine droplet spray with a consistent pattern. The three spray nozzles per side were mounted at 38, 84, and 145 cm from the ground, targeting the bottom, middle, and top canopy layers (Figure 2a). The flow was modulated by the Capstan controller (Model #625147-001, Capstan Ag Systems Inc., Topeka, KS, USA), enabling a 40% duty cycle for each treatment application. Maja et al. [34] showed that a 40% duty cycle is optimal for balancing effective defoliation and cotton lint quality. Therefore, this duty cycle was selected for this study. A 40% duty cycle indicates that the signal is open 40% of the time. The droplet distribution and canopy penetration performance of this robotic sprayer configuration were evaluated in complementary, unpublished experiments, conducted using the same platform. Related studies by Maja et al. [34] and Neupane et al. [33] reported the effects of pulse-width-modulated duty cycles on cotton fiber quality and emphasized the importance of achieving adequate canopy coverage.

Figure 2.

(a) Sprayer nozzle’s top, middle, and bottom positions, respectively; (b) diaphragm pump; (c) autonomous mobile platform with the sprayer unit; (d) autonomous mobile platform (Husky A200); (e) sprayer controller system (main controller and sprayer board).

The controller featured an ARM Cortex-M4-based microcontroller (MK66FX1M0VMD18, NXP, Eindhoven, Netherlands) equipped with a wireless transceiver (Telemetry Radio V3, Holybro, Hong Kong, China), a micro-SD card socket, and a GPS module (MTK3339, GlobalTop Technology Inc., Tainin, Taiwan). The ARM Cortex-M4 microcontroller includes 256 KB of Static Random-Access Memory (SRAM), 1280 KB of Flash RAM, 4 KB of EEPROM, six UARTs, three SPIs, four I2C interfaces, two USB controllers, and one Ethernet port. Additionally, it provides 100 programmable GPIO pins, 25 16-bit timers, and 4 32-bit timers (Figure 2e).

2.3. Data Collection and Analysis

At EREC, cotton bolls were hand-harvested over a row length of 1.8 m between 29 October and 2 November. For SCSDF, bolls were harvested on the 9th of December from a 6.1-row meter due to the late planting, which resulted in fewer bolls per plant. The samples from EREC were dried at 50–55 °C for one week, while those from SCSDF were dried at the same temperature for five days. After drying, all samples were ginned (seed was removed from the fiber) using a USDA 6-inch cotton gin (Figure 3a). The ginned fiber samples were mixed thoroughly by hand (Figure 3b). A 60 g subsample was placed in a paper bag and sent to the Product Evaluation Laboratory at Cotton Incorporated (6399 Weston Parkway; Cary, NC, USA) for HVI and AFIS fiber quality analysis (Figure 3c).

Figure 3.

(a) Ginning of cotton lint; (b) weighing; (c) cotton sample in a labeled paper bag.

The results obtained from the High-Volume Instrument (HVI) and Advanced Fiber Information System (AFIS) were analyzed using R (64-bit version 4.4.2). Due to the different planting dates and conditions at EREC and SCSDF, the two locations were analyzed separately. Before analysis, the residuals were tested for normality using the Shapiro–Wilk test and homogeneity of variance using the Bartlett test. A one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with blocking was performed to evaluate the effects of defoliation timing on fiber quality. The means were separated using Fisher’s protected LSD at the p ≤ 0.10 level. The Friedman test was used as an alternative to ANOVA when the assumption of normality of residuals was not met. Because of the high field variability and limited replication inherent in multi-factor field trials, a significance threshold of α = 0.10 was adopted, following accepted agronomic field research conventions, where biological variation is high and Type II errors (false negatives) are of greater concern. This approach is consistent with previous cotton defoliation and agronomic studies [44].

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. HVI Fiber Quality Analysis

Cotton fiber quality impacts the processing efficiency, yarn quality, and value of the end products. This quality is influenced by genotype [42,49], environmental variations [9], and management practices including the use of harvest aids [13,50]. The HVI evaluates multiple fiber characteristics from a bundle of fibers at a relatively high speed [30]. Significant differences in fiber quality parameters were observed across defoliation intervals, although not consistently across sites. Staggered defoliation timing affected some fiber quality parameters at EREC and SCSRDF (Table 1). At EREC, the defoliation timing was significant for micronaire (p = 0.0585), upper half mean lengths (p = 0.0791), uniformity index (p = 0.0673), reflectance (p = 0.0842), trash count (p = 0.0468), and short fiber index (p = 0.0810). In contrast, the defoliation timing was significant at SCSRDF for upper half mean lengths (p = 0.0746), strength (p = 0.0822), elongation (p = 0.0882), and trash area (p = 0.0759). However, the staggered defoliation timing did not influence other quality parameters at EREC (strength, elongation, yellowness, and trash area) and SCSRDF (uniformity index, reflectance, yellowness, trash count, and short fiber index) at the p = 0.10 significance level (Table 1).

Table 1.

Effects of staggered defoliation timings on fiber quality parameters: micronaire (mic), upper half mean length (UHML), uniformity index (UI), strength (Str), elongation (Elo), reflectance (Rd), yellowness (+b), trash count, trash area, and short fiber index (SFI) evaluated at Edisto Research and Education Center (EREC) and South Carolina State Research and Demonstration Farm (SCSRDF) during the 2024 season.

Micronaire refers to the fiber fineness (linear density) and maturity (degree of cell wall development) [51]. The 15-day timing had the lowest micronaire values of 3.63 and 3.37 at EREC and SCSRDF, respectively. These fiber quality values were in the base category (3.5 to 3.6 or 4.3 to 4.9) for EREC and the discounted category (<3.5 or >4.9) for SCSRDF (Table 1). The secondary cell wall biosynthesis continues until around 35 days post anthesis, after which the maturation period begins [52]. The earliest application timing of 15 days likely reduced fiber development and maturation time, resulting in low micronaire values. Snipes and Baskin [43] observed a decrease in micronaire with earlier defoliation timings. Delayed defoliation allows for a longer time for canopy photosynthesis and secondary wall development, which increases the micronaire [46]. At EREC, the 3-day timing and control produced micronaire values of 4.65 and 4.42 (base category), respectively, and the 10-, 8-, and 5-day timings resulted in the premium category (3.7 to 4.2) (Table 1). At SCSRDF, all timings except for the 15-day had micronaire values within the premium range. Micronaire values at SCSRDF were consistently lower than those at EREC, likely due to delayed planting, which reduced the available period for fiber maturation. Bauer et al. [47] reported that micronaire and maturity are lower in late planted cotton.

The upper half mean length (UHML) is the average length, by number, of the longest upper half of fibers by weight. The UHML ranged from 27.69 mm to 28.96 mm at EREC and 27.94 to 28.70 mm at SCSRDF, respectively (Table 1). The UHML was 27.69 mm and 27.94 mm for the 10-day and 8-day timings, respectively, at EREC and 27.94 mm for the 8-day timing and control at SCSRDF. These were in the range of medium fiber lengths (25.14 mm to 27.94 mm). The remaining treatments at both locations had long fibers (28.19 to 32.00 mm). The UHML at the 8-day timing was significantly different than the 5-day and control timings at EREC; however, the 8-day timing and control (27.94 mm) were different than the 15-day timing (28.70 mm) at SCSRDF (Table 1). The remaining defoliation timings at both sites were not different from the control. Fiber length is determined by the elongation process occurring between 2 and 20 days post anthesis and is influenced by availability of carbohydrates and turgor pressure in the central vacuole [53]. Late staggered defoliation (5 d and 3 d) intervals may allow for completion of this process, enhancing fiber length and uniformity. Snipes and Baskin [43] reported increased fiber length with earlier defoliation. Although staggered defoliation affected fiber length in our study, a consistent pattern of increased fiber length with early applications was not observed. The uniformity index (UI), expressed as percentage, is the ratio of UHML to mean length. The UI ranged from 82.4% to 83.6% at EREC. The 10-day (82.47%) and 8-day (82.32%) timings were significantly different than the control (83.60%) at EREC. The 10-day and 8-day timings were within the average range of 80 to 82, less than 83% (intermediate range), while the remaining defoliation timings and the control were in the high-UI range (83 to 85). No differences (p = 0.90) were observed for the uniformity index between the defoliation timings (15 to 3 days) and control at SCSRDF (Table 1).

Fiber strength is defined as the force required in grams to break a bundle of fibers that is one tex in size. One tex is the weight in grams of 1000 m of fiber [22]. The strength of the cotton fibers at EREC ranged from 27.45 g tex−1 to 29.18 g tex−1. This range was in the average category (26 to 28 g tex−1) across all treatments and control plots, except for the 15-day and 5-day timings, which had higher strengths, falling into the strong category (29 to 30 g tex−1). At SCSRDF, the 15-day timing exhibited the highest fiber strength (very strong: 31 and above). and all the remaining treatments fell into the strong category (Table 1).

Elongation (p = 0.2228), yellowness (p = 0.3708), and percent trash area (p = 0.3157) revealed no significant differences between defoliation timings at EREC, with values ranging from 7.00 to 7.58, 7.98 to 8.98, and 0.17 to 0.47, respectively (Table 1). The data showed high elongation (6.8 to 7.6) and typical yellowness of 6 to 12 for upland cotton. However, reflectance (p = 0.0842), trash count (p = 0.0468), and short fiber index (p = 0.0810) were significantly different among defoliation timings at EREC. The 5-day interval reflectance (76.77) was significantly different than the 15-day (79.92) and 8-day (79.42) intervals and the control (80.52). However, there were no differences in reflectance between the 15-day, 10-day, 8-day, and 3-day intervals and control. The trash count ranged from 13.50 to 23.75 at EREC. The lowest trash count was observed at the 3-day timing (13.50), which was significantly different from the 10-day (21.5) and 5-day (23.75) timings (Table 1). For the short fiber index, the 8-day interval had the highest value of 8.15%. Differences were observed between the 8-day (8.15%), 15-day (7.73%), and 3-day (7.75%) timings and the control (7.53%).

At SCSRDF, elongation (p = 0.0822) and percent trash area (p = 0.0759) were significantly different among defoliation intervals. However, reflectance (p = 0.9399), yellowness (p = 0.3463), trash count (p = 0.2691), and short fiber length (p = 0.4495) were not different among the defoliation intervals (Table 1). Elongation in the control (7.42%) was significantly different from the 5-day (7.12%), 10-day (7.12%), and 15-day (7.07%) intervals. For the trash area, the 8-day (0.20) and 5-day (0.19) intervals were significantly different than the 3-day interval (0.08) (Table 1). The percentage trash area was in the classer leaf grade of 2 (0.13–0.20) for the 8-day and 5-day defoliation timings, and for all remaining timings, it was within the classer leaf grade of 1 (≤0.13). Reflectance and yellowness values ranged from 78.62 to 79.52 and 7.52 to 8.65. The short fiber index ranged between 7.12 and 7.52, which fell into the low-SFI category (6 to 9). The overall quality was uniform at SCSRDF, which could have been attributed to late planting, which resulted in fewer bolls and less variability in fiber quality.

The color grade for EREC included white or light spotted fibers with strict middling or middling category, whereas, for SCSRDF, all the fibers were white with good middling, strict middling, middling, and strict low middling. White middling and white strict middling were the most observed color categories for cotton fibers in both fields.

Previous research examining the effect of defoliation timing on fiber quality has resulted in conflicting outcomes. Bynum and Cothren [44] reported that the defoliation timing had no effect on fiber length, length uniformity, and fiber strength. Similar results were observed in ref. [45] for ultra-narrow row cotton, with no impact on fiber strength, staple length, uniformity, or extraneous matter content. However, Van Der Sluijs and Hunter [54] reported decreases in fiber length, micronaire, and maturity with earlier harvest aid application. While Snipes and Baskin [43] observed a decrease in micronaire with early defoliation, they reported increases in fiber length and strength. Larson et al. [45] reported similar outcomes of significant effects on micronaire, with higher values for delayed defoliation. On the other hand, Wang et al. [20] reported that late spraying had little or no effect on quality traits like length, uniformity, micronaire, and elongation, whereas the fiber strength was increased. Our study reported a significant impact on UHML at both locations, while other parameters, except for yellowness, were impacted at either location. It is important to note that previous studies did not practice staggered defoliation, which may explain the differences in findings. Although differences were not statistically significant across all parameters at both locations, measurable trends were observed in fiber quality improvements, particularly in upper half mean length (UHML) and micronaire, as confirmed by HVI analyses. These findings suggest that staggered defoliation using a robotic platform can contribute to improved fiber length uniformity and maturity consistency compared with conventional broadcast defoliation. However, this proof-of-concept study does not claim universal superiority; rather, it highlights the system’s potential for targeted, canopy-wise defoliation that could be further enhanced through integration with selective harvesting technologies.

3.2. Fiber Quality Using Advanced Fiber Information System (AFIS)

3.2.1. Neps Parameter

Neps are knots or clusters of entangled fibers, which can be fiber knots entirely or entangled with foreign materials, such as seed coat fragments [54]. There were no significant differences in nep size (p = 0.1401), neps per gram (p = 0.1673), seed coat nep size (p = 0.1907), and seed coat neps content per gram (p = 0.5823) among the defoliation timings and control at either EREC and SCSRDF (Table 2). Nep size ranged from 663 to 687 µm at EREC and 665 to 684 µm at SCSRDF. The number of neps per gram at EREC ranged from 247.25 to 271.25 neps g−1, while it ranged from 183.50 to 241.75 neps g−1 at SCSRDF. The neps per gram for the control plot at SCSRDF was within the low-nep range of 100 to 200 neps g−1, except for which all the values were within the medium range (200 to 300 neps g−1) (Table 2). Neupane et al. [33] reported that most of the fibers fell within the low range of below 200 neps per gram for similar nep size values. The seed coat neps (SCN) value was in the best (up to 10 SCN g−1) or low-seed-coat-neps category (11 to 20 SCN g−1) for EREC, whereas for SCSRDF, it was within the best category (up to 10 SCN g−1). Zeng and Meredith [55] reported the average nep size, nep count per gram, SCN size, and SCN count per gram as 661, 94, 1210, and 5.90, respectively, for five cotton cultivars. The neps g−1 was higher in our study, which could be due to lower maturity of the fibers. Early application of harvest aid chemicals increases the number of fiber neps due to the termination of fiber development and maturation [56].

Table 2.

Effects of selected defoliation timings on nep size, number of neps, seed coat nep size (SCN), and number of SCN at Edisto Research and Education Center (EREC) and South Carolina State Research and Demonstration Field (SCSRDF) in 2024.

3.2.2. AFIS Length Parameters

Fiber length parameters in the HVI did not account for within-sample variation in length; therefore, an AFIS is used to evaluate individual fibers and further characterize within-sample fiber length distribution [40]. An AFIS determines both the length and diameter of fibers, thus giving a measurement of numerical and weight-based length distributions [57]. The average fiber length based on weight, L(w), upper quartile length (UQL, a measure of fiber length that is longer than 25% of all fibers by weight), and fiber length longer than 5% of all fibers by number, L (5%), were significantly different at a 1% significance level, and the average fiber length on a number basis L(n) at a 10% level of significance for EREC (Table 3). The L(w) ranged between 24.89 mm to 26.16 mm at EREC. The control had the longest length (26.16 mm), significantly different from the 10-, 8-, 5-, and 3-day timings, whereas the 5-day timing resulted in the shortest length (24.89 mm), significantly different from the 15-day and control treatments. The UQL value was highest for the control (30.99 mm) and significantly different from the 10-, 8-, 5-, and 3-day timings. The longest L(n) was observed in the control (22.60 mm), which was significantly different from the 10-day and 5-day timings. The L5% (n) was highest for the control (34.80 mm) and significantly differed from all treatment timings. Other length parameters, such as length variation by weight L(w) CV (p = 0.2320), length variation by number L(n) CV (p = 0.5051), short fiber content (SFC), fibers less than 12.7 mm by weight SFC (w) (p = 0.2596), and fibers less than 12.7 mm by length SFC(n) (p = 0.4072) were not influenced by staggered defoliation timings at EREC.

Table 3.

Effects of selected defoliation timings on fiber length by weight (L[w], (L[w] CV)), upper quartile length by weight (UQL [w]), short fiber content by weight (SFC [w]), average fiber length based on number (L[n], L[n] CV), short fiber content by number (SFC [n]), and >5% fiber length by number at Edisto Research and Education Center (EREC) and South Carolina State Research and Demonstration Field (SCSRDF) in 2024.

At SCSRDF, the average fiber length based on weight, L(w), and upper quartile length (UQL) were significantly different at a 10% level of significance. The L(w) ranged between 25.65 mm to 26.92 mm. The 3-day timing resulted in the longest length (26.92 mm), significantly different from the 10-day and 8-day timings, whereas the 8-day timing resulted in the shortest length (25.65 mm), significantly different from the 15-day and 3-day timings. The UQL values ranged between 30.23 mm to 31.24 mm. The lowest value of UQL was observed for the 8-day interval, with significant differences from the 3-day interval. The variation in fiber length by weight, L(w) CV; short fiber content by weight; average fiber length by number, L(n); variation in fiber length by number, L(n) CV; short fiber content by number; and fiber length longer than 5% of all fibers by number L (5%) were non-significant (p = 0.2254, 0.3317, 0.1337, 0.1727, 0.2321, and 0.1410, respectively).

A study by Liu (2024) [41] demonstrated the means of L(w), L(w) CV, UQL (w) [mm], SFC (w), L (n), L(n) CV, SFC(n), and L 5% (n) were 27.18, 32.03, 32.77, 6.84, 21.85, 49.78, 23.68, and 36.58, respectively, for commercial cotton cultivars. Paudel et al. [58] also reported UQL values for cotton samples ranging from 24.13 to 35.05 mm, with a mean of 28.70 mm.

3.2.3. AFIS Trash Parameter

Trash size varied significantly across treatments at EREC (p = 0.0175), with the largest size (343.50 µm) being observed in the control. This was significantly different from all the staggered defoliation timings (Table 4). The total (dust and trash) contents per gram (p = 0.9090), dust content per gram (p = 0.9090), trash content per gram (p = 0.7519), and visible foreign matter percentage (p = 0.9038) ranged from 270 to 357.50 per gram, 226.50 to 306 per gram, 32.50 to 51.75 per gram, and 0.83 to 0.98 percent, respectively. No significant variations were observed across treatment groups and control in total trash content per gram, trash size, number of dust particles, trash content per gram, and percentage of visible foreign matter (VFM) at SCSRDF (p = 0.2274, 0.2077, 0.2544, 0.1296, and 0.1493, respectively) (Table 4). Calhoun and Bargeron [59] reported the total trash content, trash size, dust content, trash content, and VFM was 280, 355, 224, 55, and 1.07, respectively.

Table 4.

Effects of selected defoliation timings on trash parameters (total number of particles, mean size of particles, number of dust particles < 500 µm, number of trash particles > 500 µm, and visible foreign materials (VFMs) and dust and trash contents in % at Edisto Research and Education Center (EREC) and South Carolina State Research and Demonstration Field (SCSRDF) in 2024.

3.2.4. Fiber Fineness, Maturity Ratio, and Immature Fiber Content

The fineness of the fibers is the weight per unit length of fibers in millitex. One thousand meters of fiber with a mass of 1 milligram equals 1 millitex [60]. Fiber maturity is often represented by the term circularity, which is defined as the cross-sectional area of the secondary cell wall relative to the area of a circle with the same perimeter [61]. The immature fiber content is the percentage of fibers with less than 0.25 circularity. A lower IFC percentage is suitable for dyeing [56]. The maturity ratio is defined as the ratio of fibers with 0.5 or more circularity divided by the number of fibers with 0.25 or less circularity. Fibers with a higher maturity ratio are considered more suitable for dyeing [60].

Significant differences in fiber quality parameters were observed across defoliation intervals, although not consistently across sites. Staggered defoliation timings had no significant effects on fiber fineness, immature fiber content (IFC), or maturity ratio at EREC (p = 0.3439, 0.7046, and 0.7818, respectively) and fineness and maturity ratio at SCSRDF (p = 0.1565 and 0.2257, respectively). However, it had a significant effect on IFC at SCSRDF (p = 0.0399). Treatment 1 (15 day) had the highest IFC, which was statistically different from the control and 10-, 8-, and 3-day timings; however, all the treatments and control were within the average range of 8 to 14% (Table 5). Cotton fibers ranged between very fine (<125 millitex) and very coarse (>250 milllitex) (Table 5). Except for the 15-day timing at SCSRDF (0.79, immature), all defoliation timings had fibers that were in the mature range (maturity ratio > 0.8). The maturity ratio was close to 0.8, showing that the fibers were less mature. Liu [41] reported the fineness, IFC, and maturity ratio for commercial cotton cultivars were 161.85, 6.87, and 0.88, respectively. Paudel et al. [58] reported that the fiber fineness ranges from 137 to 198, with an average value of 163 and an average maturity ratio of 0.86. While our results were within the ranges of these studies, the average value was slightly lower, especially for treatments with early defoliation timing, indicating that the overall fiber maturity was low.

Table 5.

Effects of staggered defoliation timing on average fineness (fine), immature fiber content (IFC), and maturity (Mat) ratio at Edisto Research and Education Center (EREC) and South Carolina State Research and Demonstration Field (SCSRDF) in 2024.

4. Conclusions

The effects of staggered defoliation varied across the two sites which made it difficult to conclude significant improvement in fiber quality compared to the standard farmer practice. Thefore, this study represents an initial prsoof-of-concept evaluation, highlighting feasibility rather than superiority of the robotic staggered defoliation in cotton. Nevertheless, staggered defoliation demonstrated potential to influence fiber quality positively, especially fiber length characteristics (UHML, L(w), and UQL), as confirmed by both HVI and AFIS analyses. Fiber maturity, indicated by micronaire and immature fiber content, is also influenced by staggered defoliation. Staggered application of defoliants could potentially reduce micronaire, bringing fibers to within the premium range in fields where high micronaire is a concern. The 5-day interval for staggered defoliation resulted in better HVI fiber quality parameters, including micronaire, length, and strength, except for the trash content, which was higher than in other treatments. However, this improvement was not reflected in the AFIS results. Staggered defoliation with a 15-day interval reduced the micronaire and maturity ratio; however, other quality parameters were within the standard range. This presents the potential for early staggered defoliation and harvest to reduce exposure to weather conditions. A multivariate analysis of HVI and AFIS parameters could reveal interactions between fiber quality parameters and provide a more comprehensive understanding of the influence of staggered defoliation timing on fiber quality.

The fiber quality parameters for staggered defoliation were similar to standard practice although canopy-wise defoliation was practiced, the bolls were harvested all together, leaving mature bolls exposed to weather conditions. With the advancement in automation and precision technology, staggered defoliation followed by selective harvesting targeting each canopy level at its peak maturity could result in more uniform and higher-quality fibers. Further research is needed on source–sink dynamics with respect to defoliant applications to enhance the utility of staggered defoliation. Moreover, the exploration of different application timings based on boll maturity, optimization of operational parameters such as application volume, and duty cycles of the robotic spray system could enhance staggered defoliation and fiber quality in cotton. Future research will include the publication of spray deposition and canopy penetration analyses to complement the fiber quality results presented in this study, providing a more complete validation of the robotic defoliation system. Future studies will also incorporate multiple site years to evaluate inter-annual consistency and strengthen the robustness of the findings.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.B., J.M.M., M.W.M. and A.K.; Methodology, J.M.M., M.W.M., A.K., V.P., G.M. and J.L.; Software, J.M.M., M.W.M., A.K. and J.L.; Validation, A.K., J.L., M.W.M. and J.M.M.; Formal Analysis, A.K., M.W.M. and J.M.M.; Investigation, J.M.M., M.W.M., A.K., V.P., G.M. and J.L.; Resources, J.M.M., V.P., E.B., M.W.M., A.K., V.P., G.M. and J.L.; Data Curation, A.K. and V.P.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, A.K.; Writing—Review and Editing, M.W.M., J.M.M., A.K., V.P., G.M., J.L. and E.B.; Visualization, J.M.M., M.W.M. and A.K.; Supervision, J.M.M., M.W.M., J.L., E.B. and G.M.; Project Administration, M.W.M., J.M.M. and E.B.; Funding Acquisition, J.M.M., E.B. and M.W.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by funding from Cotton Incorporated under Project No. 24-061.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the results of this study can be made available from the corresponding authors upon request.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the support of Cotton Incorporated for funding this project under Project No. 24-061. Special thanks to Roberta Smith-Uhl, Andi Korestsky, and the staff at the Product Evaluation Laboratory, Cotton Inc., for their assistance in processing and analyzing fiber samples using HVI and AFIS testing. We would also like to thank Kyle Kinard and Zachary Jordan for their assistance with the spraying applications. Their contributions to field operations were essential to the success of this study.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Edward Barnes was employed by the company Cotton Incorporated. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Spraying Dates for Staggered Defoliation at Edisto Research and Education Center (EREC) and South Carolina State Research and Demonstration Field (SCSRDF) in 2024

| Treatments | Canopy Level | EREC | SCSRDF |

| Treatment 1 (15 d interval) | Bottom | 17 September | 28 October |

| Middle | 1 October | 12 November | |

| Top | 17 October | 27 November | |

| Treatment 2 (10 d interval) | Bottom | 25 September | 8 November |

| Middle | 7 October | 18 November | |

| Top | 17 October | 27 November | |

| Treatment 3 (8 d interval) | Bottom | 1 October | 11 November |

| Middle | 9 October | 19 November | |

| Top | 17 October | 27 November | |

| Treatment 4 (5 d interval) | Bottom | 7 October | 18 November |

| Middle | 11 October | 22 November | |

| Top | 17 October | 27 November | |

| Treatment 5 (3 d interval) | Bottom | 11 October | 22 November |

| Middle | 14 October | 25 November | |

| Top | 17 October | 27 November | |

| Control | Whole canopy | 17 October | 27 November |

Appendix A.2. Details of the Spraying System for Broadcast and Staggered Defoliation

| High boy sprayer used for the broadcast defoliation: Nozzle type: TeeJet 8004EVS, even flat fan # on boom: 40 Spray width: 20 m Speed: 9.7 kph Pressure: 345 kPa Boom height: 61 cm Spray volume: 147 liter ha−1 | Autonomous robotic spraying system used for staggered defoliation: Nozzle: Flat fan nozzle Pressure (kPa): 482 Duty cycle: 40% Flow rate: 22.8 mL/s Nozzle height: 38, 84 and 145 cm from ground Speed of movement = 3.3 kph |

References

- Ali, M.A.; Ilyas, F.; Danish, S.; Mustafa, G.; Ahmed, N.; Hussain, S.; Arshad, M.; Ahmad, S. Soil management and tillage practices for growing cotton crop. In Cotton Production and Uses: Agronomy, Crop Protection, and Postharvest Technologies; Springer: Singapore, 2020; pp. 9–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.A.; Fang, D.D. Cotton as a world crop: Origin, history, and current status. In Cotton; Fang, D.D., Percy, R.G., Eds.; ASA, CSSA, SSSA: Madison, WI, USA, 2015; pp. 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C. Natural Textile Fibres: Vegetable Fibres. In Textiles and Fashion: Materials, Design and Technology; Elsevier Inc.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015; pp. 29–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahbandeh, M. Leading Cotton Producing Countries Worldwide in 2022/2023. US Department of Agriculture. 2023. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/263055/cotton-production-worldwide-by-top-countries/ (accessed on 24 February 2025).

- Meyer, L.; Dew, T. Cotton and Wool- Cotton Sector at a Glance. Economic Research Service, USDA. 2025. Available online: https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/crops/cotton-and-wool/cotton-sector-at-a-glance (accessed on 24 February 2025).

- National Agricultural Statistics Service. 2023 State Agriculture Overview South Carolina. USDA, NASS. 2025. Available online: https://www.nass.usda.gov/Quick_Stats/Ag_Overview/stateOverview.php?state=SOUTH%20CAROLINA (accessed on 24 February 2025).

- Brown, S.; Sandlin, T. How to think about fiber quality in cotton. Alabama Cooperative Extension System. In Crop Production. 2022. Available online: https://www.aces.edu/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/ANR-2637-HowToThinkCotton_FiberQuality_052022L-G.pdf (accessed on 23 October 2025).

- Beegum, S.; Reddy, V.; Reddy, K.R. Development of a cotton fiber quality simulation module and its incorporation into cotton crop growth and development model: GOSSYM. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2023, 212, 108080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradow, J.M.; Davidonis, G.H. Effects of Environment on Fiber Quality. In Physiology of Cotton; Springer: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2010; pp. 229–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodds, D.M.; Reynolds, D.B.; Barber, L.T.; Raper, T.B. 2015 Mid-South Cotton Defoliation Guide. Available online: https://arkansascrops.uada.edu/posts/crops/cotton/2025-cotton-defoliation.aspx (accessed on 11 March 2025).

- Edmisten, K.; Collins, G. Cotton Defoliation. In 2025 Cotton Information; North Carolina State University Cooperative Extension: Raleigh, NC, USA, 2025; Available online: https://content.ces.ncsu.edu/cotton-information (accessed on 21 February 2025).

- Jones, M.A.; Farmaha BSi Greene, J.; Marshall, M.; Mueller, J.D.; Smith, N.B. South Carolina Cotton Growers Guide; Clemson University Cooperative Extension: Clemson, SC, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Byrd, S.A.; Collins, G.D.; Edmisten, K.L.; Roberts, P.M.; Snider, J.L.; Spivey, T.A.; Whitaker, J.R.; Porter, W.M.; Culpepper, A.S. Leaf pubescence and defoliation strategy influence on cotton defoliation and fiber quality. J. Cotton Sci. 2016, 20, 280–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, S.H.; Cothren, J.T.; Sohan, D.E.; Supak, J.R. A History of Cotton Harvest Aids. In Cotton Harvest Management: Use and Influence of Harvest Aids; The Cotton Foundation: Memphis, TN, USA, 2001; pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Cothren, J.T.; Gwathmey, C.O.; Ames, R.B. Physiology of Defoliation in Cotton Production. In Cotton Harvest Management; The Cotton Foundation: Memphis, TN, USA, 1986; pp. 143–153. [Google Scholar]

- Snipes, C.E.; Cathey, G.W. Evaluation of defoliant mixtures in cotton. Field Crops Res. 1992, 28, 327–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catlin, C.B. Cotton Harvest Aid Efficacy and Cotton Fiber Quality as Influenced by Application Timing. Master Thesis’s, Oklahoma State University, Stillwater, OK, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Collins, G.D. Defining Optimal Defoliation and Harvest Timing for Various Fruiting Patterns of Cotton in North Carolina. Master’s Thesis, North Carolina State University, Raleigh, NC, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Çopur, O.; Demirel, U.; Polat, R.; Gür, M.A. Effect of different defoliants and application times on the yield and quality components of cotton in semi-arid conditions. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2010, 9, 2095–2100. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.; Deng, Y.; Kong, F.; Duan, B.; Saeed, M.; Xin, M.; Wang, X.; Gao, L.; Shen, G.; Wang, J.; et al. Evaluating the effects of defoliant spraying time on fiber yield and quality of different cotton cultivars. J. Agric. Sci. 2023, 161, 205–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Sun, Y.; Luo, D.; Li, P.; Liu, T.; Xiang, D.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, M.; Gou, L.; Tian, J.; et al. Harvest Aids Applied at Appropriate Time Could Reduce the Damage to Cotton Yield and Fiber Quality. Agronomy 2023, 13, 664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumner, H.R.; Herzog, G.A. Spray droplet penetration in cotton canopy using air-assisted and hydraulic sprayers. In Proceedings of the Beltwide Cotton Conference; National Cotton Council: Memphis, TN, USA, 1999; Volume 1, pp. 390–393. [Google Scholar]

- Weicai, Q.; Xinyu, X.; Longfei, C.; Qingqing, Z.; Zhufeng, X.; Feilong, C. Optimization and test for spraying parameters of cotton defoliant sprayer. Int. J. Agric. Biol. Eng. 2016, 9, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Han, Y.; Li, X.; Andaloro, J.; Chen, P.; Hoffmann, W.C.; Han, X.; Chen, S.; Lan, Y. Field evaluation of spray drift and environmental impact using an agricultural unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) sprayer. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 737, 139793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavalaris, C.; Karamoutis, C.; Markinos, A. Efficacy of cotton harvest aids applications with unmanned aerial vehicles (UAV) and ground-based field sprayers—A case study comparison. Smart Agric. Technol. 2022, 2, 100047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Y.; Song, J.; Lan, Y.; Mei, G.; Liang, Z.; Han, Y. Harvest aids efficacy applied by unmanned aerial vehicles on cotton crop. Ind. Crops Prod. 2019, 140, 111645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Ouyang, F.; Wang, G.; Qi, H.; Xu, W.; Yang, W.; Zhang, Y.; Lan, Y. Droplet distributions in cotton harvest aid applications vary with the interactions among the unmanned aerial vehicle spraying parameters. Ind. Crops Prod. 2021, 163, 113324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Q.; Xin, F.; Lou, Z.; Zhou, T.; Wang, G.; Han, X.; Lan, Y.; Fu, W. Effect of aviation spray adjuvants on defoliant droplet deposition and cotton defoliation efficacy sprayed by unmanned aerial vehicles. Agronomy 2019, 9, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Xu, W.; Zhan, Y.; Yang, W.; Wang, J.; Lan, Y. Evaluation of Cotton Defoliation Rate and Establishment of Spray Prescription Map Using Remote Sensing Imagery. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 4206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudd, J.D.; Roberson, G.T. Using unmanned aircraft systems to develop variable rate prescription maps for cotton defoliants. In ASABE 2018 Annual International Meeting; American Society of Agricultural and Biological Engineers: Detroit, MI, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, L.; Lan, Y.; Kong, H.; Kong, F.; Huang, H.; Han, X. Exploring the potential of UAV imagery for variable rate spraying in cotton defoliation application. Int. J. Precis. Agric. Aviat. 2019, 2, 42–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, E.; Morgan, G.; Hake, K.; Devine, J.; Kurtz, R.; Ibendahl, G.; Sharda, A.; Rains, G.; Snider, J.; Maja, J.M.; et al. Opportunities for Robotic Systems and Automation in Cotton Production. AgriEngineering 2021, 3, 339–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neupane, J.; Maja, J.M.; Miller, G.; Marshall, M.; Cutulle, M.; Luo, J. Effect of Controlled Defoliant Application on Cotton Fiber Quality. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 5694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maja, J.M.; Neupane, J.; Patiluna, V.; Miller, G.; Karki, A.; Marshall, M.W.; Cutulle, M.; Luo, J.; Barnes, E. Evaluating the Effect of Pulse Width Modulation-Controlled Spray Duty Cycles on Cotton Fiber Quality Using Principal Component Analysis. AgriEngineering 2024, 6, 3719–3738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, L.C. Chemical defoliation of cotton. 1. Bottom leaf defoliation. Agron. J. 1953, 45, 314–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayele, A.G.; Kelly, B.R.; Hequet, E.F. Evaluating within-plant variability of cotton fiber length and maturity. Agron. J. 2018, 110, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indest, M.O. Factors Affecting Within-Plant Variation of Cotton Fiber Quality and Yield; Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College: Baton Rouge, LA, USA, 2015; Available online: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/1091 (accessed on 19 February 2025).

- Kothari, N.; Dever, J.; Hague, S.; Hequet, E. Evaluating intraplant cotton fiber variability. Crop Sci. 2015, 55, 564–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, L. HVI: The System that has Revolutionized the Testing of Cotton Fiber Quality. In Proceedings of the World Cotton Research Conference, Athens, Greece, 6–12 September 1998; pp. 999–1002. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly, B.R.; Hequet, E.F. Variation in the advanced fiber information system cotton fiber length-by-number distribution captured by high volume instrument fiber length parameters. Text. Res. J. 2018, 88, 754–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y. Variability of Fiber AFIS Length and Maturity within and Among Upland Cotton Cultivars. J. Nat. Fibers 2024, 21, 2356694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, R.L.; Delhom, C.D.; Bange, M.P. Effects of cotton genotype, defoliation timing and season on fiber cross-sectional properties and yarn performance. Text. Res. J. 2021, 91, 1943–1956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snipes, C.E.; Baskin, C.C. Field Crops Research Influence of early defoliation on cotton yield, seed quality, and fiber properties. Field Crops Res. 1994, 37, 137–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bynum, J.B.; Cothren, J.T. Indicators of last effective boll population and harvest aid timing in cotton. Agron. J. 2008, 100, 1106–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, J.A.; Gwathmey, C.O.; Hayes, R.M. Effects of defoliation timing and desiccation on net revenues from ultra-narrow-row cotton. J. Cotton Sci. 2005, 9, 204–224. [Google Scholar]

- Bauer, P.J.; Frederick, J.R.; Bradow, J.M.; Sadler, E.J.; Evans, D.E. Canopy photosynthesis and fiber properties of normal-and late-planted cotton. Agron. J. 2000, 92, 518–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, P.J.; May, O.L.; Camberato, J.J. Planting date and potassium fertility effects on cotton yield and fiber properties. J. Prod. Agric. 1998, 11, 415–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayer. (n.d.). DP 2127 B3XF Cotton Seed. Available online: https://www.cropscience.bayer.us/d/deltapine-dp-2127-b3xf-cotton (accessed on 23 September 2025).

- Silvertooth, J.C. Crop Management for Optimum Fiber Quality and Yield; The University of Arizona Cooperative Extension: Tucson, AZ, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly, C.M.; Hequet, E.F.; Dever, J.K. Interpretation of AFIS and HVI fiber property measurements in breeding for cotton fiber quality improvement. J. Cotton Sci. 2012, 16, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Cotton Incorporated. The Classification of Cotton; Cotton Incorporated: Cary, NC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Hinchliffe, D.J.; Meredith, W.R.; Delhom, C.D.; Thibodeaux, D.P.; Fang, D.D. Elevated growing degree days influence transition stage timing during cotton fiber development resulting in increased fiber-bundle strength. Crop Sci. 2011, 51, 1683–1692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stiff, M.R.; Haigler, C.H. Recent advances in cotton fiber development. In Flowering and Fruiting in Cotton; The Cotton Foundation: Cordova, TN, USA, 2012; pp. 163–192. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Sluijs, M.J.; Hunter, L. A review on the formation, causes, measurement, implications and reduction of neps during cotton processing. Text. Prog. 2016, 48, 221–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, L.; Meredith, W.R. Neppiness in an Introgressed Population of Cotton: Genotypic Variation and Genotypic Correlation. J. Cotton Sci. 2010, 14, 17–25. [Google Scholar]

- Bange, M.P.; Long, R.L.; Constable, G.A.; Gordon, S.G. Minimizing immature fiber and neps in upland cotton. Agron. J. 2010, 102, 781–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bragg, C.K.; Shofner, F.M. A rapid, direct measurement of short fiber content. Text. Res. J. 1993, 63, 171–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paudel, D.R.; Hequet, E.F.; Abidi, N. Evaluation of cotton fiber maturity measurements. Ind. Crops Prod. 2013, 45, 435–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calhoun, D.S.; Bargeron, J.D. An Introduction to AFIS for Cotton Breeders. In Proceedings of the Beltwide Cotton Conference, New Orleans, LA, USA, 6–10 January 1997; National Cotton Council of America: Memphis, TN, USA, 1997; pp. 418–424. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, G.F.; Yankey, J.M. New Developments in Single Fiber Fineness & Maturity Measurements. In Proceedings of the Beltwide Cotton Conference, Nashville, TN, USA, 9–12 January 1996; National Cotton Council of America: Memphis, TN, USA, 1996; pp. 1284–1289. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Chang, S. Comprehensive Analysis of Cotton Fiber Infrared Maturity Distribution and Its Relation to Fiber HVI and AFIS Properties. Fibers Polym. 2024, 25, 1127–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).