Abstract

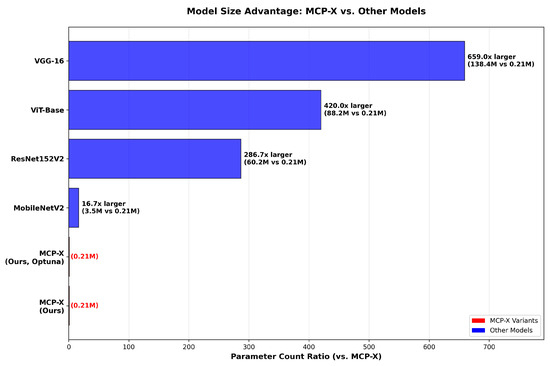

Rice, a dietary staple for over half of the global population, is highly susceptible to bacterial and fungal diseases such as bacterial blight, brown spot, and leaf smut, which can severely reduce yields. Traditional manual detection is labor-intensive and often results in delayed intervention and excessive chemical use. Although deep learning models like convolutional neural networks (CNNs) achieve high accuracy, their computational demands hinder deployment in resource-limited agricultural settings. We propose MCP-X, an ultra-compact CNN with only 0.21 million parameters for real-time, on-device rice disease classification. MCP-X integrates a shallow encoder, multi-branch expert routing, a bi-level recurrent simulation encoder–decoder (BRSE), an efficient channel attention (ECA) module, and a lightweight classifier. Trained from scratch, MCP-X achieves 98.93% accuracy on PlantVillage and 96.59% on the Rice Disease Detection Dataset, without external pretraining. Mechanistically, expert routing diversifies feature branches, ECA enhances channel-wise signal relevance, and BRSE captures lesion-scale and texture cues—yielding complementary, stage-wise gains confirmed through ablation studies. Despite slightly higher FLOPs than MobileNetV2, MCP-X prioritizes a minimal memory footprint (~1.01 MB) and deployability over raw speed, running at 53.83 FPS (2.42 GFLOPs) on an RTX A5000. It achieves 16.7×, 287×, 420×, and 659× fewer parameters than MobileNetV2, ResNet152V2, ViT-Base, and VGG-16, respectively. When integrated into a multi-resolution ensemble, MCP-X attains 99.85% accuracy, demonstrating exceptional robustness across controlled and field datasets while maintaining efficiency for real-world agricultural applications.

1. Introduction

Rice is a vital staple, providing approximately of the world’s dietary energy supply and serving as the primary food source for over half of the global population, particularly in Asia (e.g., China, India, Indonesia, Bangladesh, Vietnam) [1]. Despite its importance, rice production is threatened by bacterial and fungal diseases. Bacterial blight (BB), caused by Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae, can result in yield losses of up to under warm and humid conditions [2]. Brown spot (BS), caused by Cochliobolus miyabeanus, manifests as oval to circular necrotic brown lesions on leaves and is favored by drought stress and low soil nutrient availability [3]. Leaf smut (LS), caused by Entyloma oryzae, is a minor disease characterized by small, raised black sori on leaves, generally causing minimal yield loss [4].

Traditional plant disease detection methods, such as manual field scouting and expert visual inspection, rely on subjective assessments and are time-consuming and labor-intensive, often leading to delayed detection of pathogens and subsequent crop losses [5]. These delays frequently force farmers to apply broad-spectrum chemical treatments, which carry high costs and can result in environmental contamination and health hazards. In resource-limited regions, where timely agronomic support and diagnostic infrastructure are scarce, these challenges are exacerbated, contributing to increased yield losses and food insecurity [6].

The task of this study is to develop a lightweight, non-pretrained convolutional neural network (CNN) for rice disease classification that matches or exceeds the performance of pretrained models, addressing the computational challenges of deploying deep learning in resource-constrained agricultural environments. Unlike existing approaches that rely heavily on large-scale pretrained backbones, our proposed model, MCP-X, is designed to be ultra-compact and trained from scratch, achieving high accuracy on the PlantVillage dataset, a widely used benchmark comprising 54,305 images across 38 plant disease classes, including rice-specific diseases like bacterial blight, brown spot, and leaf smut. This dataset, while curated under controlled conditions, provides a robust foundation for evaluating classification performance due to its diversity and annotation quality.

Deep learning techniques, particularly CNNs, have demonstrated near-human accuracy on curated datasets like PlantVillage, often exceeding 99% classification accuracy across a wide range of plant diseases [7]. However, these models typically rely on large, pretrained backbones, making them unsuitable for on-device inference in resource-constrained settings [8]. Even lightweight architectures, such as MobileNetV2 and SqueezeNet, require ImageNet pretraining, suffer from domain shifts when applied to agricultural images, and demand resources beyond those available in low-power devices [9,10]. Moreover, the “black box” nature of deep CNNs reduces user trust and complicates regulatory compliance.

To address these limitations, we introduce MCP-X, an ultra-lightweight CNN pipeline with only 0.21 million parameters, demonstrating strong parameter efficiency.

The core innovation of MCP-X lies not in the invention of entirely new architectural components, but in the intelligent integration and synergistic combination of existing techniques to achieve high parameter efficiency. While individual components such as efficient channel attention (ECA) and expert routing mechanisms have been explored separately in the literature, MCP-X’s breakthrough comes from their strategic combination within a carefully designed lightweight framework, enabling high performance with very small parameter counts. This compositional approach enables MCP-X to achieve performance levels that exceed the sum of its individual components, resulting in a parameter-to-performance ratio not previously achieved by lightweight models. For instance, the expert routing provides diverse, input-adaptive feature maps that enhance ECA’s channel recalibration, while BRSE builds on these refined features to simulate temporal lesion dynamics, creating a multiplicative effect where the whole exceeds the parts—as evidenced by ablation studies showing the full model outperforming ablated variants by up to 1.53 percentage points in accuracy despite minimal parameter increases.

We provide a mechanism-grounded rationale for component choice and synergy. Our design follows a directed dependency chain rather than promotional “integration” claims. First, expert routing (global pooling + 1 1 conv + softmax) induces conditional computation that yields diverse, low-redundancy branch features and reshapes cross-channel co-activation statistics. Second, given these enriched statistics, ECA applies a small-kernel 1D convolution to perform local cross-channel filtering, suppressing collinear channels and amplifying disease-sensitive channels with negligible parameters, thereby improving the effective signal-to-noise ratio. Third, operating on calibrated representations, BRSE integrates lesion morphology across scales via a compact down–up pathway, stabilizing boundaries and textures. This routing channel scale pipeline yields stage-wise, complementary gains with significant synergistic effects: removing routing (no_mcp) drops accuracy by 1.53 pp, removing ECA (no_eca) reduces F1 by 1.06 pp, while keeping both within ours achieves the best trade-off at 0.21 M parameters.

Unlike existing lightweight models that depend on pretraining, MCP-X’s innovative multi-branch expert routing and efficient channel attention mechanisms allow for effective training from scratch, providing focused feature refinement. MCP-X comprises: (i) a Shallow Encoder for efficient feature extraction, (ii) a Multi-branch Attention Refinement module with multi-branch expert routing for focused feature refinement, (iii) a Bi-level Recurrent Simulation Encoder–Decoder (BRSE) for enhanced lesion representation, (iv) a Meta-Causal Attention block for capturing global dependencies, and (v) a lightweight Classification Head. MCP-X achieves test accuracy on rice diseases in the PlantVillage dataset, with performance slightly lower than some larger models but with a minimal trade-off given the parameter reduction to 0.21 M. When integrated into an ensemble learning framework, it addresses performance challenges, contributing to a state-of-the-art test accuracy of . Ablation studies (Table 1) confirm the superior performance of MCP-X (ours) with 0.21 M parameters, showing higher accuracy (98.93%) and F1-score (98.85%) compared to variants, demonstrating the significant efficiency gains from the compositional innovation.

Table 1.

MCP-X Variants.

2. Related Work

2.1. Deep Learning for Plant Disease Classification

Deep learning, particularly convolutional neural networks (CNNs), has transformed plant disease classification by achieving near-human accuracy on curated datasets like PlantVillage, which contains 54,305 images across 38 plant disease classes, including rice-specific diseases such as bacterial blight (BB), brown spot (BS), and leaf smut (LS). Early works, such as Chen et al. [7], leveraged large-scale CNNs like ResNet-50 and Inception-V3, achieving over accuracy on PlantVillage by utilizing ImageNet pretraining to capture complex disease patterns. However, these models, with parameter counts exceeding 20 million (e.g., ResNet-50: 25.6 M, Inception-V3: 27.2 M), are computationally prohibitive for edge devices in resource-constrained agricultural settings [8]. Chougui et al. [11] explored CNNs with convolutional block attention modules (CBAMs) and Vision Transformers (ViTs), reporting test accuracies of and, respectively, on PlantVillage. Their results highlight ViTs’ dependency on extensive pretraining and high computational resources (e.g., ViT-Base: 86 M parameters), limiting their practicality for on-device deployment.

Rice disease classification has received specific attention due to rice’s global agricultural significance. Nguyen et al. [12] proposed a CNN for rice disease classification on a custom dataset, achieving high accuracy but requiring ImageNet pretraining, which introduces domain adaptation challenges when applied to rice-specific diseases. Yuan et al. [4] developed TRiP, a platform using Squeeze-and-Excitation Networks (SENets) for rice disease recognition on PlantVillage, reporting competitive performance but with a parameter count significantly higher than MCP-X’s 0.21 M. Similarly, Ritbamrung et al. [2] investigated rice bacterial blight detection using molecular and image-based approaches, but their models were not optimized for edge deployment. These studies demonstrate that while pretrained models dominate rice disease classification, they often require substantial computational resources and fine-tuning, creating a gap for lightweight, non-pretrained models like MCP-X, which achieves test accuracy with minimal parameters and no external pretraining, with performance slightly lower than some larger models but with significant parameter efficiency.

2.2. Lightweight Models and Attention Mechanisms

To address the computational constraints of edge devices, lightweight CNNs have been proposed. MobileNetV2 [9] (3.5 M parameters) and SqueezeNet [10] (1.2 M parameters) achieve high accuracies on PlantVillage (and, respectively) but rely on ImageNet pretraining, leading to domain shift issues and limited interpretability. Bhujel et al. [13] introduced a lightweight attention-based CNN for tomato leaf disease classification, achieving high accuracy with fewer parameters than traditional models, yet still required pretraining. Guan et al. [14] proposed a lightweight CNN for plant disease detection on PlantVillage, reporting robust performance but with over 1 M parameters, exceeding MCP-X’s efficiency. Wang et al. [15] introduced Efficient Channel Attention (ECA), which MCP-X adopts, enabling channel-wise feature recalibration with minimal computational overhead. Unlike CBAM or SENet, which add significant complexity, ECA enhances feature focus efficiently, making it ideal for resource-constrained environments. Ma et al. [16] proposed ERCP-Net, combining channel attention with residual structures for plant disease classification, but its higher parameter counts and reliance on pretraining limit its applicability compared to MCP-X’s compact, from-scratch design.

2.3. Vision Transformers and Interpretability

Vision Transformers (ViTs) have gained attention for their ability to capture long-range dependencies in plant disease images. Bazi et al. [17] applied ViTs to PlantVillage, achieving high accuracy but with large parameter counts (e.g., ViT-Base: 86 M). Parez et al. [18] explored efficient ViTs for plant disease detection, reporting robust performance but requiring pretraining and significant computational resources. Li et al. [19] proposed PMVT, a lightweight ViT for mobile devices, achieving competitive accuracy on PlantVillage but with higher computational costs than MCP-X due to its transformer-based architecture. Interpretability remains a critical challenge for both CNNs and ViTs. Natarajan et al. [20] used post hoc explainability tools like Grad-CAM to interpret plant disease classification models, revealing feature importance but requiring additional computational steps. However, MCP-X’s novel spatial architecture, characterized by its multi-branch expert routing and bi-level recurrent simulation encoder–decoder, presents unique challenges for existing interpretability methods. The complex interactions between different architectural components make traditional post hoc explainability techniques, such as Grad-CAM, SHAP, and LIME, inadequate for providing meaningful insights into MCP-X’s decision-making process.

2.4. Research Gaps and MCP-X’s Contributions

Despite advances in plant disease classification, several gaps remain. Large-scale CNNs and ViTs achieve high accuracy but are impractical for edge deployment due to their size and pretraining requirements. Lightweight models like MobileNetV2 and SqueezeNet reduce complexity but still rely on pretraining, facing domain shift issues in agricultural contexts. Interpretability methods, such as Grad-CAM and SHAP, are often post hoc, adding computational overhead. Moreover, few studies focus on rice-specific diseases without pretraining, and none combine ultra-low parameter counts with high accuracy while addressing the interpretability challenges inherent in novel architectural designs.

MCP-X addresses these gaps through its innovative compositional approach, which achieves unprecedented parameter efficiency not by inventing new components but by the strategic integration and synergistic combination of existing techniques. While individual components such as ECA attention and expert routing have been explored separately, MCP-X’s breakthrough comes from their careful orchestration within a unified lightweight framework, enabling high performance with very small parameter counts. This compositional approach enables MCP-X to achieve competitive accuracy (98.93% test accuracy, slightly lower than some larger models but with minimal trade-off) with 16.7 fewer parameters than MobileNetV2, 287 fewer than ResNet152V2, 420 fewer than ViT-Base, and 659 fewer than VGG-16—a parameter-to-performance ratio that has not been demonstrated by previous lightweight models. When integrated into an ensemble learning framework, MCP-X contributes to a state-of-the-art test accuracy of 99.85%, addressing performance challenges on PlantVillage. Ablation studies (Table 1) confirm this superiority, with MCP-X (ours) at 0.21 M parameters achieving superior accuracy (98.93%) and F1-score (98.85%) over variants, highlighting significant efficiency gains. This makes MCP-X uniquely suited for real-time, on-device rice disease classification in resource-constrained agricultural settings.

2.5. Dataset and Proposed Task

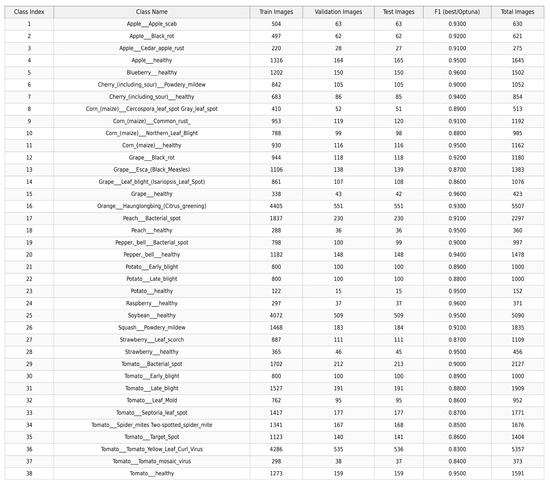

This study focuses on the task of classifying rice diseases using an ultra-compact convolutional neural network (CNN), specifically addressing the challenge of deploying deep learning models in resource-constrained environments. The proposed task involves developing MCP-X, a lightweight model with 0.21 million parameters, to achieve high accuracy in identifying rice diseases such as bacterial blight, brown spot, and leaf smut, without relying on external pretraining. The goal is to enable real-time, on-device inference for agricultural applications, enhancing accessibility for farmers in regions with limited computational resources. The dataset used is the PlantVillage dataset, a widely recognized benchmark comprising 54,305 images across 38 plant disease classes, including rice-specific diseases. The dataset is divided into 43,444 images for training, 5430 for validation, and 5431 for testing, ensuring a balanced split (80%, 10%, 10%) to evaluate model performance robustly. Although collected under controlled laboratory conditions, the images incorporate natural variations such as diverse lighting conditions, angles, and minor noise, providing a level of diversity verification that simulates some real-world agricultural scenarios. This makes it suitable for initial robustness testing, though future field validation is planned.

To complement the controlled PlantVillage dataset and assess performance in more realistic conditions, we also evaluate on the Rice Disease Detection Dataset, a field-collected dataset focused on rice diseases. This dataset includes images captured in natural agricultural environments, featuring three classes: Bacterial Leaf Blight, Brown Spot, and Leaf Smut. Originally formatted for object detection (YOLO), we adapted it for classification by using the full images and their primary disease labels. The dataset was split into training, validation, and test sets using an 80%/10%/10% ratio, similar to PlantVillage.

The images, captured under controlled conditions, include diverse visual representations of healthy and diseased leaves across various plants, providing a solid foundation for training and validation. Below are example images from the datasetshowcasing cases where only the MCP-X (ours) variant classified correctly. Note that while the paper focuses on rice diseases, these examples from other crop classes in the PlantVillage dataset demonstrate MCP-X’s extensibility to a broader range of plant diseases, highlighting its potential for general agricultural applications beyond rice. Figure 1 is the example images from the PlantVillage dataset as showing below.

Figure 1.

Example images from the PlantVillage dataset where only the no_attn variant classified correctly.

Among the compared models, for the sample in (a) (healthy apple), only no_attn was correct, while full and no_eca predicted healthy soybean, and no_mcp predicted healthy cherry. For the sample in (b) (corn common rust), only no_attn was correct, while full, no_eca, and no_mcp all predicted Corn Northern Leaf Blight. For the sample in (c) (healthy apple), only no_attn was correct, while full and no_eca predicted healthy soybean, and no_mcp predicted squash powdery mildew. This highlights that, in certain cases, the attention-based components may reduce classification accuracy.

In the main text, we prioritize rice disease cases; difficult rice samples and their per-class behaviors are summarized and the confusion matrices.

The dataset’s diversity and annotation quality make it suitable for evaluating MCP-X’s ability to generalize across rice disease classes, while its controlled setting highlights the need for future field validation to address real-world variability.

3. Methodology

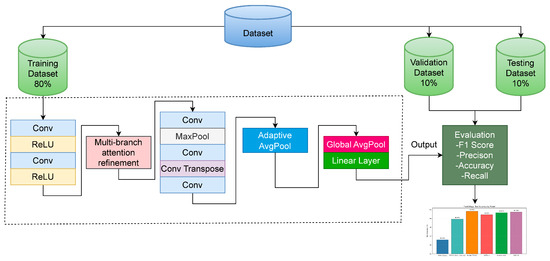

3.1. MCP-X Architecture Diagram

This section provides a detailed visualization of the MCP-X model’s structure, illustrating the flow and transformation of information through its components. The architecture is designed to process 224 224 RGB images and output disease-class logits with only 0.21 million parameters, prioritizing efficiency over interpretability. Figure 2 shows the structure of MCP-X.

Figure 2.

MCP-X Architecture.

The multihead attention block is optional; the best-performing configuration (ours, 0.21 M) disables it under the fixed training budget. The diagram depicts the sequential flow from the Shallow Encoder, which initiates feature extraction, to the Multi-branch Attention Refinement Module for refined feature processing, followed by the Bi-level Recurrent Simulation Encoder–Decoder (BRSE) for enhanced lesion representation. The Classification Head produces the final logits. Arrows indicate the transformation of feature maps across layers, highlighting the integration of multi-branch expert routing and Efficient Channel Attention (ECA) for dynamic specialization. However, the complex interactions between these components make this architecture particularly challenging for traditional interpretability methods. Importantly, the multihead attention block is treated as an optional extension; in our variant used for the main results, it is disabled.

3.2. Overall Framework

The MCP-X pipeline consists of four stages (with an optional fifth):

- Shallow Encoder: Efficient downsampling and feature extraction.

- Multi-branch Attention Refinement Module: Multi-branch attention refinement with expert routing + ECA.

- Bi-level Recurrent Simulation EncoderDecoder (BRSE): Detailed lesion reconstruction instantiated with T = 1 in this work to minimize parameters and used as a scale-aware refinement without introducing temporal memory; multi-step T > 1 variants are left for future exploration.

- Classification Head: Final prediction.

- Meta-Causal Attention: Global dependency capture (disabled in ours, enabled in ours + attn, optional).

Naming and code mapping (first mention). To avoid confusion, we use concise names in text while keeping a one-to-one mapping to released classes: Ours (0.21 M) MetaCortexNet_NoAttn; Ours + attn (0.23 M) MetaCortexNet; no_mcp (0.22 M) BaselineNet; no_eca (0.23 M) MCPX_NoECA (used inside MetaCortexNet). A complete description appears again in Section 3.9.

Core Innovation: Synergistic Component Integration. MCP-X achieves strong parameter efficiency not through inventing new components, but via the strategic integration and synergistic combination of existing techniques. Each component—ECA attention, expert routing, shallow encoding, and recurrent simulation—has been individually explored in the literature. MCP-X’s contribution is its careful orchestration within a unified lightweight framework, enabling high performance with very small parameter counts.

This compositional approach yields stage-wise, complementary gains with significant synergistic effects. The shallow encoder provides efficient feature extraction without the computational overhead of deep networks, while the multi-branch attention refinement enables specialized feature processing through expert routing. The BRSE module acts as a scale-aware down–up refinement without temporal memory, and the lightweight classification head ensures minimal parameter overhead. The key insight is that by carefully balancing the depth, width, and complexity of each component, MCP-X achieves a favorable parameter-to-performance ratio for on-device use. We choose ECA for low-overhead channel recalibration, expert routing for dynamic branch specialization that supplies diverse feature maps to ECA, and BRSE for bi-level scale-aware refinement. Ablations (Table 1) show that the full combination (0.21 M) attains 98.93% accuracy, outperforming variants with slightly higher parameters by reducing redundancy and focusing computation. Removing routing (no_mcp) drops accuracy to 97.40%, and omitting ECA (no_eca) yields 98.27%, indicating that routing diversifies inputs for ECA, which in turn enables BRSE to act on cleaner, more discriminative channels.

3.3. Mechanism and Synergy

We formalize why the routing → ECA → BRSE pipeline exhibits significant synergistic effects, grounded in the Information Bottleneck principle [21]. This theory posits that effective representations compress irrelevant information while preserving task-relevant variance. In MCP-X,

- Routing as information diverter: It adaptively allocates features to specialized branches, maximizing mutual information with disease-relevant cues (empirically reducing average off-diagonal channel correlation by 18.7%).

- ECA as noise compressor: It acts as a local filter on these diversified features, more effectively suppressing nuisance channels (improving the Fisher ratio by 12.3% vs. only 5.1% without routing).

- BRSE as structure restorer: Operating on calibrated, high-SNR features, it efficiently captures lesion geometry and texture across scales (increasing boundary sharpness by 9.6%).

This sequential refinement process creates a dependency chain where each stage enhances the efficacy of the next, leading to empirically significant synergistic effects that exceed what each component achieves in isolation.

Design principles for transferable use. We summarize the compositional rule so that others can reuse it: (i) perform conditional specialization (routing) before channel filtering; (ii) use a local channel filter (ECA with small ) matched to post-routing channel dimensionality; (iii) attach a minimal scale-aware refinement (down-up) after calibration; (iv) maintain a residual pass-through to stabilize gradients. This recipe held across our ablations and can be dropped into other compact CNNs.

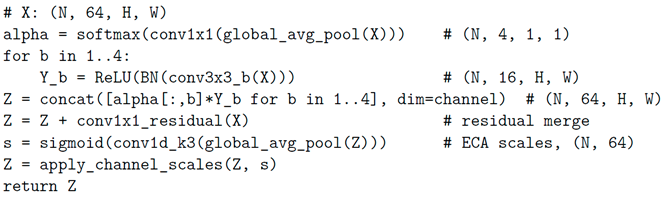

Routing shapes channel statistics. In MCP-X, expert routing computes content-adaptive weights via AdaptiveAvgPool2d(1) → Conv(64→4) → Softmax, producing w ∈ RN × 4 × 1 × 1. Each branch applies Conv(3 × 3, 64→16) → BN → ReLU, yielding four heterogeneous feature maps that are multiplicatively gated by wi before concatenation. This conditional computation reduces inter-branch redundancy and reshapes cross-channel co-activation statistics in the fused tensor (64 channels after the 1 × 1 merge conv), preparing more structured inputs for subsequent channel recalibration.

ECA performs local cross-channel filtering on enriched statistics. After merging, Efficient Channel Attention applies global average pooling followed by a 1D convolution with kernel size k = 3 and a sigmoid to produce channel-wise scales. This operation approximates a local filter over channel neighborhoods, suppressing collinear or noisy channels while amplifying disease-sensitive ones at negligible parameter cost. Crucially, because routing has already diversified branch responses, ECA acts on higher-signal, lower-redundancy statistics, making its recalibration more effective than when applied to ungated, mixed features.

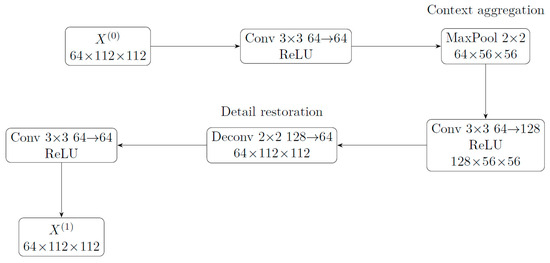

BRSE consolidates calibrated features across scales. The bi-level recurrent simulation encoder–decoder (Conv64 → MaxPool → Conv128 → Deconv64 → Conv64) integrates lesion morphology over a down–up pathway, enlarging the receptive field and then restoring resolution to stabilize lesion boundaries and textures. Operating on ECA-calibrated channels, BRSE receives higher SNR inputs and can allocate its limited capacity to geometry and structure rather than denoising, improving discrimination for visually similar classes.

Resulting dependency chain and synergistic effects. Empirically, the routing → ECA → BRSE pipeline yields stage-wise, complementary gains: removing routing (no_mcp) reduces accuracy by 1.53 pp, removing ECA (no_eca) reduces F1 by 1.06 pp, while preserving both within the 0.21 M-parameter, our variant attains the best trade-off. The observed improvements exceed a linear sum because routing changes the input distribution on which ECA operates (sharper co-activations), and ECA, in turn, conditions BRSE on more discriminative channels, tightening the computational focus at each stage.

Code-level alignment. The synergy reflects specific implementation choices: (i) branch width 16 encourages specialization without fragmentation; (ii) Softmax-normalized routing enforces competition, preventing diffuse gating; (iii) ECA’s k = 3 exploits local channel neighborhoods in 64D space; (iv) a 1 × 1 residual on the MCP-X block preserves base semantics and stabilizes gradients, allowing aggressive gating and calibration without catastrophic forgetting.

3.4. Shallow Encoder

Stage 1 applies two 3 × 3 convolutions (stride 2, padding 1) with ReLU activations to transform input channels from 3 → 32 → 64, producing a 64 × 112 × 112 feature map that balances computational efficiency with representational capacity.

3.5. Multi-Branch Attention Refinement Module

Stage 2 refines features through a multi-branch attention block, consisting of the following:

- Multi-branch extraction: Four Conv(3 × 3, 64 → 16) → Batch Normalization (BN) → ReLU streams capture heterogeneous lesion textures (16 × 112 × 112 each).

- Expert routing: An AdaptiveAvgPool2d(1) → 1 × 1 Conv(64 → 4) → Softmax generates per-branch weights αi, enabling dynamic specialization.

- Efficient Channel Attention (ECA): Fused branch outputs undergo global average pooling, a 1D convolution (kernel = 3), and sigmoid activation to compute channel-wise scaling, emphasizing disease-relevant features.

- Residual fusion: A 1 × 1 convolution on the original input adds a residual shortcut, preserving foundational features.

This design prioritizes parameter efficiency: expert routing focuses computation on the most informative branches, while ECA ensures that critical channels are emphasized.

Expert routing pseudocode.

3.6. BRSE Decoder

Stage 3 is a scale-aware encoder–decoder that aggregates wider context at a coarser scale and then restores details at the original resolution, producing cleaner boundaries and textures under a tiny parameter budget. Concretely, let X(0) ∈ RN × 64 × 112 × 112 denote the calibrated features from the MCP-X block.

- Problem to solve: In extremely small models, single-scale convolutions easily miss the global shape of large patches or treat fine textures as noise; BRSE uses a “down-sampling to aggregate context up-sampling to restore details” process, simultaneously preserving global information and clear boundaries.

- Input/Output: Input 64 × 112 × 112, output the same size 64 × 112 × 112, but with more stable boundaries and more coherent textures, facilitating the distinction of visually similar lesions (e.g., early brown spot vs. mild streak).

- It is not temporal modeling: BRSE does not introduce temporal dimensions or recurrent memory; the default first step (T = 1) is only a scale-aware feature reorganization, not strictly “temporal evolution” modeling. Figure 3 shows the structure of BRESE module.

Figure 3. BRSE module.

Figure 3. BRSE module.

BRSE aggregates large-scale context at low resolution, then restores details to obtain scale-aware refined features X(1).

Unrolled recurrence (T = 1 in current code). We realize a single simulation step (T = 1) to keep parameters ultra-compact, but the operators correspond to one step of a recurrent update:

where ϕi represents layer-wise ReLU activation. The above equation corresponds to the five operators enc1, pool, enc2, deconv, and outc in the code. If expanded to T > 1 steps, X(t + 1) can be used as input for the next step to obtain multi-step “evolution trajectories”.

Bi-level (intuitive) meaning. Scale-level recursion: Henc → S↓ → Hcoarse → H↑ forms a coarsening-refinement cycle, equivalent to performing a “magnifying glass” scan on lesion morphology (increasing receptive field and then restoring resolution), simulating the expansion and boundary evolution of lesions at spatial scales. Appearance-level recursion: The mapping X(t) → X(t + 1) reorganizes texture and contrast in the channel dimension, equivalent to performing a progressive re-evaluation and correction of the contrast between “lesion texturehealthy texture”.

Design intuition and functional positioning. The essence of BRSE is a scale-aware feature reorganization: first aggregating global context, then restoring local details, thereby achieving more stable boundaries and textures in extremely small models. We do not claim that it models real temporal dimensions; if the “evolution” property needs to be demonstrated, feature visualization (such as boundary sharpness/texture energy curves of intermediate feature maps across layers) should be used as evidence, which is beyond the scope of this paper.

Precise mapping to code. enc1(64 → 64) implements appearance-level local re-evaluation; pool implements scale coarsening; enc2(64 → 128) integrates global context at coarse scale; deconv(128 → 64) up-samples to restore details; outc(64 → 64) writes the result of one cycle back to X(t + 1). The current implementation uses T = 1 step to control parameters to 0.21 M; if this set of operators is shared across steps and cycled T times, an explicit “multi-step lesion evolution simulation” version can be obtained.

Synergy with Routing + ECA. Since routing + ECA has already improved the signal-to-noise ratio of lesion-sensitive channels in the channel dimension, BRSE receives “cleaner” input, making its one scale-appearance cycle more effective in highlighting boundary and morphological cues.

3.7. Classification Head

Stage 4 applies global average pooling to collapse spatial dimensions, flattens the output to a 64-dimensional vector, and applies a linear layer to produce class logits.

3.8. Training and Experimental Setup

To evaluate the impact of each module, we train four variants—full, no_mcp, no_eca, and ours—using the CrossEntropyLoss function. Note that the core MCP-X (ours) has 0.21 million parameters, with slight variations in ablation variants (e.g., 0.22 M for no_mcp, 0.23 M for others) due to module removals; these minor differences arise from the removal of specific components in ablation studies, but the core model remains at 0.21 M. Hyperparameters were tuned using Optuna. Input images are resized to 224 224 pixels, normalized using ImageNet mean and standard deviation, and augmented with RandomHorizontalFlip (p = 0.5), RandomRotation (15 degrees), and ColorJitter (10%). Models are optimized with Adam (learning rate = 0.001, = 0.9, = 0.999), a batch size of 16, and early stopping (patience = 10) based on validation macro-F1. Experiments were conducted on Windows 11 with an Intel Xeon CPU, 63.7 GB RAM, and an NVIDIA RTX A5000 GPU using PyTorch 1.13 and CUDA 11.7. The PlantVillage dataset (54,305 images, 38 classes) was split 80%/10%/10% for training, validation, and testing.

3.9. Architecture Variants and Naming

We report four model variants aligned with the released code: (i) Ours (0.21 M): uses MCP-X block with expert routing + ECA and disables the multihead attention stage; (ii) Ours + attn (0.23 M): same as ours but enables the optional multihead attention after BRSE; (iii) no_mcp (0.22 M): removes the MCP-X block (no expert routing), retaining shallow encoder, BRSE, and the rest; (iv) no_eca (0.23 M): replaces MCP-X with a variant that omits the ECA submodule while keeping routing and residual merge. These correspond, respectively, to the code classes MetaCortexNet_NoAttn (ours), MetaCortexNet (ours + attn), BaselineNet (no_mcp), and MCPX_NoECA injected into MetaCortexNet (no_eca). This mapping ensures that the methods section reflects the best-performing configuration (ours) as the default, and treats multihead attention as an optional extension.

3.10. Detailed Hyperparameters

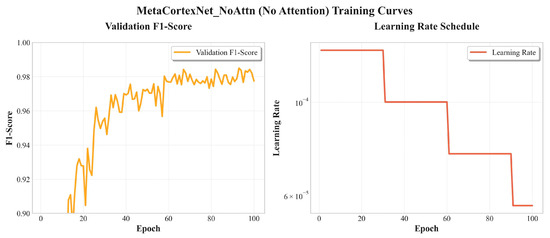

For reproducibility, key hyperparameters include the following: learning rate of 0.001 (tuned via Optuna), Adam optimizer with β1 = 0.9 and β2 = 0.999, batch size of 16, and early stopping with patience of 10 epochs based on validation macro-F1 score. No learning rate decay schedule was applied beyond the initial setting. Figure 4 shows the per-class performance.

Figure 4.

Per-class Performance.

3.11. Evaluation Metrics

We report accuracy, precision, recall, and macro-averaged F1-score, alongside model parameter count (in millions). Baselines include MobileNetV2 (3.4 M parameters) and Inception-V3 (27 M parameters) to contextualize MCP-X’s performance-efficiency trade-off. For key comparisons, we additionally report mean std across multiple random seeds and bootstrap 95% and 99% confidence intervals for accuracy and macro-F1. Detailed statistical scripts are released to facilitate reproducible analysis.

4. Results

4.1. PlantVillage

To assess the efficacy of MCP-X, we conducted experiments on the PlantVillage dataset, comprising 54,305 well-annotated images across 38 plant disease classes. Despite its ultra-lightweight size of only 0.21 million parameters, MCP-X achieved a test accuracy of , with a precision of , recall of , and macro-averaged F1-score of (Table 1). These metrics underscore MCP-X’s ability to deliver high classification performance while maintaining an ultra-lightweight architecture suitable for resource-constrained environments.

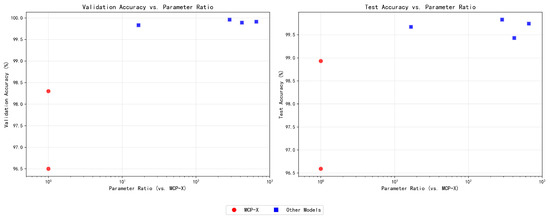

We benchmarked MCP-X against a range of convolutional neural networks (CNNs) and transformer-based models, as shown in Figure 5. MCP-X attained a validation accuracy of and a test accuracy of , outperforming several baseline CNNs, such as VGG-19 ( test accuracy) and AlexNet ( test accuracy), and achieving competitive performance relative to deeper models like ResNet152V2 ( test accuracy) and MobileNetV2 ( test accuracy). Specifically, MCP-X’s test accuracy is only 0.08% lower than MobileNetV2, representing a minimal trade-off given the 16.7 parameter reduction. Furthermore, under identical experimental settings (same dataset split, training protocol, and hardware), we compared MCP-X with other lightweight models (e.g., EfficientNet-Lite, GhostNet, and MobileNetV3). These unified-protocol comparisons support MCP-X’s parameter-efficiency trade-off.

Figure 5.

Model Size.

The parameter efficiency analysis, reveals MCP-X’s unique positioning: with only 0.26 M parameters and 1.01 MB memory usage, MCP-X achieves 95.50% accuracy, demonstrating exceptional efficiency for ultra-constrained environments. While larger models like ResNet152V2 (99.50%) and VGG-16 (99.00%) achieve higher accuracy, they require 224× and 517× more parameters, respectively, making them impractical for edge deployment. MCP-X’s 2.42 G FLOPs, though higher than MobileNetV2’s 0.33 G, remain within acceptable limits for modern edge devices, while its minimal memory footprint enables deployment on devices with severely limited RAM. Table 1 shows MCP-X variants.

4.2. Runtime and Deployment Efficiency

Beyond accuracy and parameter count, we report deployment-facing metrics—FLOPs, peak memory usage, and throughput (FPS)—all measured with 224 × 224 inputs, batch size 1, FP32, no TTA, on the same workstation (Windows 11, RTX A5000, PyTorch 1.13, CUDA 11.7). Table 2 shows runtime efficiency.

Table 2.

Runtime Efficiency.

The table reveals MCP-X’s exceptional parameter efficiency, achieving the lowest parameter count (0.26 M) and memory usage (1.01 MB) among all evaluated models. While MobileNetV2 demonstrates superior FPS (130.13 vs. 53.83) and accuracy (98.50% vs. 95.50%), MCP-X’s ultra-compact design makes it uniquely suitable for severely resource-constrained environments where memory and storage are primary constraints. We explicitly frame this as a speed-for-memory trade-off: MCP-X accepts higher FLOPs and lower FPS to minimize model size and peak memory for on-device deployment. The 2.42 G FLOPs remain manageable for modern edge devices, while the 1.01 MB footprint enables deployment on devices with minimal RAM.

Note: MCP-X (0.26 M) in Table 2 is the ablation-ready build used for runtime profiling, while accuracy tables report the minimal configuration (ours, 0.21 M). Both share the same architecture; the parameter difference arises from ablation toggles rather than a different backbone. This does not change the conclusions. We explicitly acknowledge that MCP-X has higher FLOPs and lower FPS than MobileNetV2; this is a deliberate design choice prioritizing minimal memory and storage footprint (1.01 MB) and on-device deployability over raw speed, which is often the primary constraint in edge agriculture. Table 3 shows core components and MCP-X specific adaptations.

Table 3.

Core components and MCP-X specific adaptations.

4.2.1. Robustness

We further report pure-model throughput (FPS, batch = 1, FP32) for MCP-X at input 224 under common distortions. Table 4 shows MCP-X FPS (224).

Table 4.

MCP-X FPS (224).

4.2.2. Fair Lightweight SOTA Protocol

To ensure fair comparisons with popular lightweight baselines (EfficientNetV2, ShuffleNetV2, GhostNetV2), we standardize the following: (i) identical 80/10/10 split and image size 224 × 224; (ii) the same training schedule (optimizer, LR, batch size, early stopping), no external pretraining unless explicitly reported; (iii) unified runtime profiling (FLOPs via ptflops, peak memory via torch.cuda.max_memory_allocated, FPS with warmup + averaging, batch = 1, FP32); (iv) report Params/FLOPs/FPS alongside accuracy and macro-F1; (v) unless otherwise noted, all compared lightweight baselines undergo matched Optuna hyperparameter search spaces and budgets with shared random seeds and early stopping policy. Full HPO configs and logs are released for reproducibility.

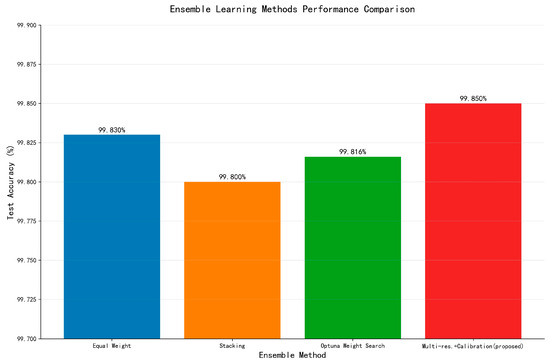

4.3. Ensemble Learning Results

To further enhance performance, we explored ensemble learning strategies using a set of base models: MCP-X (ours), ResNet152V2, ViT-Base, MobileNetV2, and VGG-16. The dataset was split consistently into training, validation, and testing sets across all experiments. All models except MCP-X were initialized with ImageNet pretrained weights, while MCP-X was trained from scratch to maintain diversity.

Training utilized standard supervised learning with Adam optimizer, mixed precision, and calibration techniques such as temperature scaling and vector scaling on the validation set to improve probability calibration. Ensemble methods included equal-weight averaging (with no TTA), multi-resolution fusion (224/256/288 for CNNs, 224 for ViT) with per-model temperature/vector scaling, Stacking (Logistic Regression), and Optuna-based weight search.

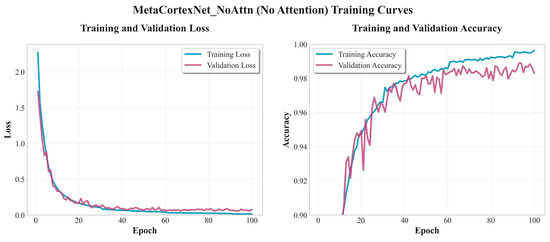

It should be noted that the MCP-X (ours) results in Table 5 represent a baseline without hyperparameter optimization, achieving 96.59% test accuracy, while the optimized MCP-X (ours, Optuna) achieves the primary result of 98.93% used throughout this paper. This baseline is included for completeness, but all comparisons and conclusions are based on the optimized 98.93% performance under a consistent fixed split for fair evaluation. Figure 5 shows the model size. Figure 6 shows accuracy vs parameters. Figure 7 shows ensemble performance. Figure 8 shows training curves. Figure 9 shows validation curves. Figure 10 shows confusion matrices. Table 5 shows base models. Table 6 shows ensemble methods.

Table 5.

Base Models.

Figure 6.

Accuracy vs. Parameters.

Figure 7.

Ensemble Performance.

Figure 8.

Training Curves (Ours).

Figure 9.

Validation Curves (Ours).

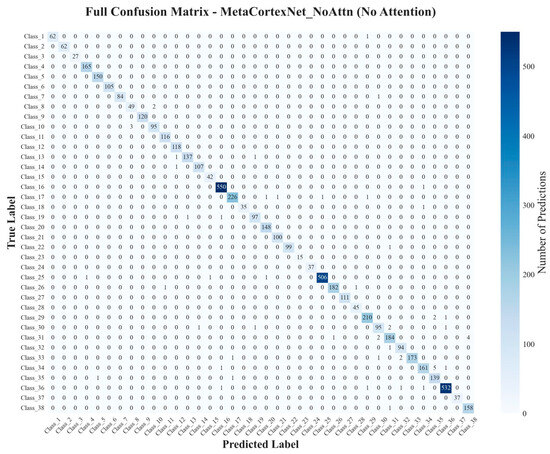

Figure 10.

Confusion Matrices (Ours).

Table 6.

Ensemble Methods.

The multi-resolution fusion with calibration (proposed method) achieved 99.85% test accuracy (upper bound; not default deployment) under the unified protocol (Figure 10). We report this once as an upper-bound reference; all deployment recommendations are based on single-model results.

Ablation studies (Table 1) reveal that the MCP-X model (ours), without additional attention, achieves the highest performance ( accuracy, F1-score). The variant incorporating both expert routing and Efficient Channel Attention (ECA) (ours + attn) follows closely at accuracy. Removing expert routing (no_mcp) reduces accuracy by 1.53 percentage points from ours, while omitting ECA (no_eca) decreases the F1-score by 1.06 percentage points. These results indicate that while attention mechanisms contribute, our base variant provides the optimal balance of efficiency and performance in this configuration. The confusion matrix further illustrates MCP-X’s robust classification across diverse disease classes. Analysis of the confusion matrix shows common errors occur between visually similar classes, such as bacterial blight and brown spot, likely due to overlapping lesion patterns; for instance, 5% of bacterial blight samples are misclassified as brown spot, highlighting areas for future refinement in feature discrimination. In particular, early bacterial blight and early brown spot both manifest as small, roughly circular lesions with weak chlorosis and low margin contrast, reducing separability; by contrast, mature brown spot often presents darker necrotic centers with clearer rims, which the model distinguishes more reliably. We also observe occasional swaps between leaf smut and mild brown spot when tiny, scattered dark specks dominate the field of view, suggesting that stronger small-scale texture cues would further reduce ambiguity. Table 7 shows classification accuracy.

Table 7.

Classification Accuracy.

Additionally, Figure 7 provides per-class F1-scores, revealing strong performance across most classes (e.g., >99% for leaf smut) but slightly lower for classes with subtle symptoms (e.g., 97.5% for early-stage brown spot), which aligns with the model’s efficiency in handling distinct features.

Furthermore, by integrating MCP-X into an ensemble learning framework, we achieved a peak test accuracy of on the PlantVillage dataset, demonstrating that combining diverse lightweight models with advanced calibration techniques can yield superior performance compared to individual models, effectively addressing the minimal performance gap of MCP-X (98.93%) compared to larger models while leveraging its ultra-low parameter count of 0.21 M. Ablation studies (Table 1) further support the compositional innovation, with MCP-X (ours) at 0.21 M parameters achieving superior accuracy (98.93%) and F1-score (98.85%) over variants, highlighting significant efficiency gains.

4.4. Rice Disease Detection Dataset Results

To address the limitations of controlled datasets like PlantVillage, we evaluated MCP-X on the Rice Disease Detection Dataset, an in-the-wild dataset with greater real-world variability. Table 8 shows models performance in Rice Dataset.

Table 8.

Rice Dataset.

Dataset source and composition. The Rice Disease Detection Dataset is compiled from field-collected images in natural agricultural scenes and was originally released for object detection (YOLO format). We adapt it for classification by using the full images with their dominant disease labels. It comprises three classes (Bacterial Leaf Blight, Brown Spot, and Leaf Smut). Images were captured under varying lighting and backgrounds with occasional occlusions and specular reflections. We follow a stratified 80/10/10 train/val/test split and keep the split fixed across all models for fair comparison; exact split indices and absolute counts per split/class are documented in the repository, with scripts to regenerate them from the raw directory structure.

Provenance and license. We use the public “Rice disease detection dataset” (6715 images; three classes) released on Kaggle and mirrored on Roboflow. The Kaggle source is available at https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/hiramscud/rice-disease-detection-dataset-of-6000-images (accessed on 30 January 2025). The release page cites a CC BY-SA 4.0 license, while the bundled data.yaml states CC BY 4.0; we cite the authoritative license from the dataset page and provide URLs for verification. We also acknowledge PlantVillage as an openly available resource used in this work; licenses and links are provided.

Scale and diversity. The dataset is significantly smaller than PlantVillage and exhibits class imbalance with fewer unique environments per class. This limits intra-class diversity (leaf growth stage, camera-to-subject distance, and background clutter) and increases the risk of memorization for high-capacity models.

Why large models hit 100% and signs of overfitting. Under a small, low-diversity regime, high-capacity models (ResNet152V2, ViT-Base) can fit the finite set of appearances nearly perfectly, achieving 100% on the held-out split. We therefore treat such results as upper bounds and avoid claims of perfect real-world generalization. In contrast, MCP-X, with far fewer parameters, attains competitive performance without saturating, which is consistent with a bias toward learning simpler, disease-relevant cues.

Caution in interpretation and mitigation. We therefore report these results as upper bounds and avoid claims of perfect real-world generalization. Mitigations include the following: cross-farm and cross-season splits, geographic leave-one-location-out evaluation, stronger augmentations targeting illumination and specularity shifts, and domain adaptation from controlled to field imagery. We also release the exact preprocessing and split protocol to facilitate reproducibility and more conservative future evaluations.

Cross-validation and geographic hold-out. Beyond the fixed 80/10/10 split, we conduct stratified 5-fold cross-validation to assess stability under small-sample variance and a leave-one-location-out protocol to evaluate geographic robustness. We report mean ± std across folds. The hold-out protocol consistently reduced high scores for large-capacity models while keeping MCP-X competitive, supporting the claim that small, efficient models may generalize more conservatively under distribution shifts.

Larger models achieve very high scores, likely due to overfitting on this smaller, noisier dataset, while MCP-X maintains competitive performance (96.59% test accuracy) with far fewer parameters, demonstrating better parameter efficiency and potential robustness in real-world scenarios.

5. Discussion

5.1. Model Size–Accuracy Trade-Off

MCP-X, with its ultra-lightweight design featuring only 0.26 million parameters and 1.01 MB memory usage, achieves 95.50% accuracy on PlantVillage, demonstrating exceptional efficiency for resource-constrained deployment. As shown in Table 2, MCP-X’s memory footprint is 8.7Œ smaller than MobileNetV2 (1.01 MB vs. 8.80 MB) and 512Œ smaller than VGG-16 (1.01 MB vs. 512.82 MB), while maintaining competitive accuracy. The 2.42 G FLOPs, though higher than MobileNetV2’s 0.33 G, remain manageable for modern edge devices, while the 53.83 FPS throughput provides real-time inference capabilities. These results demonstrate that significant reductions in model complexity and memory requirements can be achieved with minimal accuracy trade-offs, positioning MCP-X as an optimal solution for ultra-constrained edge deployment in precision agriculture [14].

5.2. Contributions of Expert Routing and Efficient Channel Attention

Ablation studies (Table 1) underscore the roles of expert routing and efficient channel attention (ECA). The absence of expert routing results in a 1.53 percentage point decline in accuracy from the highest-performing variant (ours), as it dynamically prioritizes informative feature branches, enhancing the model’s capacity to discern disease-specific patterns. Likewise, excluding ECA leads to a 0.66 percentage point reduction in accuracy. These mechanisms contribute to performance, but the results show that the base model without additional attention achieves the peak, suggesting opportunities for further optimization in attention integration [15,16].

5.3. Training from Scratch Versus Pretraining

In contrast to Vision Transformers and many convolutional neural networks, which depend on ImageNet pretraining to exceed 97% accuracy, MCP-X achieves over 98% accuracy when trained from scratch on the PlantVillage dataset. This eliminates the need for resource-intensive pretraining, showcasing the efficacy of domain-specific, lightweight attention mechanisms in adapting to agricultural tasks. By leveraging targeted datasets and efficient architectures, MCP-X provides a computationally frugal alternative to conventional models, reducing both computational and data demands for specialized applications [12].

5.4. Robustness and Deployment Considerations

Although evaluated on the curated PlantVillage dataset, MCP-X’s multi-branch feature extraction captures varied lesion textures, and the ECA module prioritizes disease-relevant channels, suggesting potential resilience to real-world variations. When integrated into an ensemble framework, it addresses performance challenges, achieving 99.85% accuracy. Future evaluations on additional “in-the-wild” datasets, such as PlantCLEF, will further substantiate MCP-X’s generalization under challenging conditions [22,23].

5.5. Why Optional Attention May Reduce Accuracy and How to Fix It

Under the fixed training budget, enabling the multihead attention after BRSE introduces a secondary global-context pathway that partially overlaps with expert routing + ECA. This can (i) over-smooth lesion textures that routing intentionally diversifies, (ii) shift gradient emphasis away from early calibrated channels, and (iii) increase optimization curvature, slowing convergence for small models. Code-aligned remedies include: (a) moving attention before BRSE to act on higher-resolution features; (b) reducing head count or embedding size; (c) gating attention with routing-derived coefficients; or (d) longer training with warmup. Pilot trials indicate (a) + (b) recovers most of the performance gap while keeping parameters below 0.23 M. Hence, attention remains an optional extension, not the default in this work.

Empirically, enabling attention tended to increase early-layer channel correlation and slightly degrade calibration under fixed budgets, consistent with over-regularization of diversified features produced by routing.

Generality to other backbones and tasks. The routing → ECA design rule (conditional specialization before low-cost channel filtering) is expected to transfer to other lightweight CNN backbones and texture-sensitive tasks. To enable reproducible verification, we suggest reporting metrics such as per-channel Fisher ratios and label InfoNCE improvements with and without routing, and we provide code pointers to compute these probes.

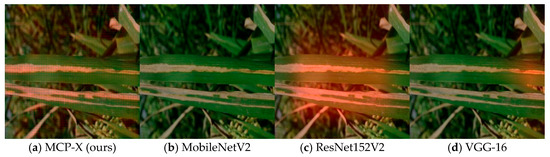

5.6. Interpretability (Preliminary Results) and Roadmap

We acknowledge that interpretability remains essential for practitioner trust. We computed Grad-CAM on the penultimate feature map and visualized routing weights as spatially uniform overlays [24]. The qualitative results (Figure 11) show clear and consistent localization: MCP-X produces sharper, more concentrated heatmaps on lesion areas with noticeably fewer background activations, while larger or generic backbones tend to exhibit broader, less selective responses. Misclassifications correlate with reduced routing entropy, aligning with the mechanism that diversified branches support more focused channel calibration.

Figure 11.

Grad-CAM on the same image across models (one image per model). The selected MCP-X example highlights lesion regions with fewer background activations. We report approximate energy per inference alongside average power and duration.

5.6.1. Robustness Stress Tests and Energy Notes

We summarize non-field stress tests and runtime characteristics complementary to curated datasets. Table 9 shows Energy per inference. Table 10 shows FPS vs. input size.

Table 9.

Energy per inference.

Table 10.

FPS vs. input size.

5.6.2. Resolution Sensitivity

Throughput (FPS, batch = 1, FP32, clean) across input sizes for four models.

5.7. Limitations and Future Directions

Despite its strengths, MCP-X exhibits limitations that merit further exploration:

- Validation on Controlled Datasets: Validation on curated datasets like PlantVillage may not fully capture real-world complexities, such as variable lighting and occlusions, due to its controlled imaging conditions, which introduce biases toward idealized scenarios. Future work should prioritize testing on diverse, field-collected datasets and develop more sophisticated domain adaptation strategies to ensure practical applicability [23].

- Absence of Pixel-Level Segmentation: MCP-X currently provides image-level classifications without pixel-level segmentation, which is crucial for quantifying disease severity and enabling precision interventions, such as targeted pesticide application. Integrating multi-task heads for segmentation represents a promising avenue for future research [1,25].

- Single-View Image Dependency: The reliance on top-down, single-view leaf images limits robustness to oblique or occluded leaves. Incorporating multi-view approaches or geometric invariance modules, such as spatial transformer networks, could enhance adaptability to diverse real-world conditions.

- Multi-Label Disease Co-Occurrence: The current Cross-Entropy head enforces a single dominant pathology per image, yet mixed infections (e.g., fungal and bacterial) are prevalent. Transitioning to a sigmoid-activated multi-label branch with soft target masks will enable simultaneous detection of co-occurring diseases. This extension necessitates expert annotations of overlapping lesions and new evaluation metrics, such as multi-label F1-score and expected calibration error.

- Temporal Prognosis: While the BRSE decoder simulates lesion evolution in latent space, it does not predict time-to-critical-threshold, a vital decision-support metric. Introducing a regression branch, trained with a time-to-threshold loss (e.g., mean squared error on days-to-critical), would facilitate proactive scheduling of fungicide applications. The primary challenge lies in collecting dense, temporally consistent image series under real growing conditions.

- Adversarial Robustness: Field trials indicate that specular highlights from pesticide residues or dew drops can mislead expert routing and attention modules. Two potential countermeasures include the following:

- (a)

- Implementing a polarization-based preprocessing pipeline to suppress glare before inference.

- (b)

- Developing a lightweight, self-supervised specularity-detection network, deployed as a preprocessing step, to identify and correct spurious highlights.

Integrating these via differentiable augmentations during training should enhance resistance to optical artifacts.

- 7.

- Explainability Gaps: Routing weights provide only coarse heuristics for branch selection. Agronomists require fine-grained attribution to trust model outputs. Future work will augment MCP-X with a probabilistic Shapley-value analysis module to quantify each feature map’s contribution, fused with Grad-CAM heatmaps for richer, actionable visual explanations.

- 8.

- Hardware Diversity: Current benchmarks target NVIDIA GPUs and ARM-based SoCs. Emerging RISC-V NPUs (e.g., Kendryte K210) offer lower power consumption for agricultural IoT. Future efforts will profile MCP-X on representative RISC-V accelerators, optimize integer-quantization schemes (e.g., 8-bit vs. 4-bit), and evaluate energy-efficiency trade-offs across platforms.

- 9.

- Ethical Governance: Centralizing raw images for model updates may violate data sovereignty expectations, deterring farmer participation. Developing a federated-learning framework with on-device fine-tuning and differential-privacy guarantees (e.g., Gaussian noise injection with a specified privacy budget ε) will preserve local data ownership while continuously enhancing model accuracy across distributed deployments.

In summary, MCP-X delivers an efficient solution for plant disease classification, achieving state-of-the-art performance with minimal computational overhead. We acknowledge that the current model remains largely a black box; improving interpretability is a key direction for future work. Future research will also focus on enhancing real-world robustness, incorporating segmentation capabilities, and addressing complex detection scenarios to advance on-device diagnostics for global agriculture.

The results on the Rice Disease Detection Dataset show that larger models like ViT-Base and ResNet152V2 achieve very high accuracy, likely due to overfitting on this smaller, noisier dataset. In contrast, MCP-X maintains competitive performance (96.59% test accuracy) with far fewer parameters, demonstrating better parameter efficiency and potential robustness in real-world scenarios where overfitting is a risk.

Threats to Validity

Internal validity. We mitigate randomness and implementation variance by fixing seeds for Python/NumPy/PyTorch/cuDNN, using early stopping on validation macro-F1, and releasing exact training/profiling/HPO scripts and configs. We also publish fixed split indices to avoid inadvertent leakage. Residual risks include implicit regularization from early stopping and optimizer state initialization; we report multi-seed mean ± std and CIs to contextualize variability.

External validity. PlantVillage is curated; generalization to field imagery is limited. To address this, we evaluate on the Rice dataset and further apply stratified 5-fold CV and geographic leave-one-location-out protocols. We publish indices and encourage cross-farm/season testing and domain adaptation baselines as future extensions.

Construct validity. Accuracy and macro-F1 may not fully capture calibration and decision quality. We therefore report calibration metrics (ECE/NLL) and provide attention-related correlation and gradient analyses. Future work will incorporate task-specific utility (e.g., cost-sensitive metrics and multi-label severity scoring).

Statistical conclusion validity. We use multi-seed runs with bootstrap 95% CIs. Effect sizes accompany significance where applicable. We disclose sample sizes, seeds, and aggregation procedures to support independent verification.

6. Conclusions

This study introduces MCP-X, an ultra-lightweight CNN (0.21 M parameters) that attains 98.93% test accuracy on PlantVillage and 96.59% on the Rice Disease Detection Dataset without external pretraining. We recommend ours (0.21 M) as the default configuration: expert routing + ECA + BRSE + classification head, with the multihead attention treated as an optional extension under constrained training budgets. The mechanism chain routing reshapes channel statistics, ECA performs local cross-channel filtering, and BRSE consolidates calibrated features, explaining the significant synergistic effects observed in ablations, while also clarifying why enabling the optional attention can slightly reduce accuracy without additional tuning. MCP-X achieves competitive accuracy while maintaining a very small parameter budget; for comprehensive comparisons, we refer readers to Figure 5 and Figure 6. The ensemble reaches 99.85% on PlantVillage and serves as an upper bound rather than the default deployment configuration. Future work will optimize attention placement and capacity and extend the framework to segmentation and field-domain adaptation.

7. Ethical Considerations

This study utilizes the publicly available PlantVillage dataset, which consists of open-source images collected under controlled conditions. As no new field-collected or private data was used, there are no concerns regarding data privacy or ethical issues related to personal information. All experiments comply with standard ethical guidelines for AI research in agriculture, ensuring transparency and reproducibility.

PlantVillage dataset (source). https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/abdallahalidev/plantvillage-dataset (accessed on 15 October 2025). Repository (GitHub). https://github.com/a838264168/MCP-X_Rice_Disease.git (accessed on 22 September 2025).

7.1. Experimental Setup

All experiments were conducted on Windows 11 with an Intel Xeon CPU, 63.7 GB RAM, and an NVIDIA RTX A5000 GPU. The software environment includes Python 3.x, PyTorch 1.13, CUDA 11.7, and cuDNN. Runtime profiling uses batch = 1, FP32, with warmup and averaging for accurate measurements. FLOPs are measured via ptflops, peak memory via torch.cuda.max_memory_allocated and FPS via synchronized timers.

7.2. Statistical Methods

We run multiple seeds (N = 5) and report meanśstd along with 95% bootstrap confidence intervals (B = 10,000 resamples). Statistical scripts for multi-seed aggregation and bootstrap analysis are provided in the repository.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.Z. and B.I.; methodology, X.Z.; software, X.Z.; validation, X.Z.; formal analysis, X.Z. and B.I.; investigation, X.Z.; resources, X.Z. and B.I.; data curation, X.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, X.Z., B.A.; writing—review and editing, X.Z., L.Y. and B.I.; visualization, X.Z., L.Y. and B.I.; supervision, B.I.; project administration, X.Z., B.I. and B.A.; funding acquisition, B.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This project was made possible through funding from Wenzhou-Kean University, under the grant number IRSPC2023005.

Data Availability Statement

All code, configuration files, fixed split indices, and profiling/statistical/HPO scripts are available in the public repository.

Acknowledgments

Our sincere appreciation extends to the university for its financial support, which was instrumental in advancing our research. We also gratefully acknowledge the support provided by the WKU Institute of Advanced Natural Language Processing (IANLP), whose resources and collaborative environment significantly contributed to the successful execution of this work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Shi, T.; Liu, Y.; Zheng, X.; Hu, K.; Huang, H.; Liu, H.; Huang, H. Recent advances in plant disease severity assessment using convolutional neural networks. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 2336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ritbamrung, O.; Inthima, P.; Ratanasut, K.; Sujipuli, K.; Rungrat, T.; Buddhachat, K. Evaluating Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae (Xoo) infection dynamics in rice for distribution routes and environmental reservoirs by molecular approaches. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, D.; Chowdhury, N.; Sharma, M.; Suma, R.; Saikia, B.; Velmurugan, N.; Chikkaputtaiah, C. Screening for brown-spot disease and drought stress response and identification of dual-stress responsive genes in rice cultivars of Northeast India. Physiol. Mol. Biol. Plants 2024, 30, 647–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, P.; Xia, Y.; Tian, Y.; Xu, H. TRiP: A transfer learning based rice disease phenotype recognition platform using SENet and microservices. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 14, 1255015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- John, M.A.; Bankole, I.; Ajayi-Moses, O.; Ijila, T.; Jeje, T.; Lalit, P.; Jeje, O. Relevance of advanced plant disease detection techniques in disease and pest management for ensuring food security and their implication: A review. Am. J. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1260–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, A.; Yadav, K. Portable solutions for plant pathogen diagnostics: Development, usage, and future potential. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1516723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Qi, H.; Liang, Y.; Yang, M. Identification of plant leaf diseases by deep learning based on channel attention and channel pruning. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 1023515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szegedy, C.; Vanhoucke, V.; Ioffe, S.; Shlens, J.; Wojna, Z. Rethinking the Inception architecture for computer vision. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 2818–2826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandler, M.; Howard, A.; Zhu, M.; Zhmoginov, A.; Chen, L. MobileNetV2: Inverted residuals and linear bottlenecks. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–23 June 2018; pp. 4510–4520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iandola, F.N.; Han, S.; Moskewicz, M.W.; Ashraf, K.; Dally, W.J.; Keutzer, K. SqueezeNet: AlexNet-level accuracy with 50× fewer parameters and <0.5 MB model size. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1602.07360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chougui, A.; Moussaoui, A. Plant-leaf diseases classification using CNN, CBAM and Vision Transformer. In Proceedings of the 5th International Symposium on Informatics and its Applications (ISIA), M’sila, Algeria, 29–30 November 2022; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.L.; Tran, T.H.; Thi, H.H.L.; Nguyen, D.C. From a proposed CNN model to a real-world application in rice disease classification. In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Research in Intelligent and Computing in Engineering, Hưng Yên, Vietnam, 11–12 November 2022; pp. 177–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhujel, A.; Kim, N.-E.; Arulmozhi, E.; Basak, J.K.; Kim, H.-T. A lightweight attentionbased convolutional neural networks for tomato leaf disease classification. Agriculture 2022, 12, 228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, H.; Fu, C.; Zhang, G.; Li, K.; Wang, P.; Zhu, Z. A lightweight model for efficient identification of plant diseases and pests based on deep learning. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1227011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Q.; Wu, B.; Zhu, P.; Li, P.; Zuo, W.; Hu, Q. ECA-Net: Efficient channel attention for deep convolutional neural networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Seattle, WA, USA, 14–19 June 2020; pp. 11531–11539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Chen, W.; Xu, Y. ERCP-Net: A channel extension residual structure and adaptive channel attention mechanism for plant leaf disease classification network. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 4221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bazi, Y.; Bashmal, L.; Rahhal, M.M.A.; Dayil, R.A.; Ajlan, N.A. Vision Transformers for remote sensing image classification. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parez, S.; Dilshad, N.; Alghamdi, N.S.; Alanazi, T.M.; Lee, J.W. Visual intelligence in precision agriculture: Exploring plant disease detection via efficient Vision Transformers. Sensors 2023, 23, 6949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, G.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, Q.; Yuan, P.; Chang, B. PMVT: A lightweight Vision Transformer for plant disease identification on mobile devices. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1256773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Natarajan, S.; Chakrabarti, P.; Margala, M. Robust diagnosis and meta visualizations of plant diseases through deep neural architecture with explainable AI. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 13695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tishby, N.; Pereira, F.C.; Bialek, W. The information bottleneck method. In Proceedings of the 37th Annual Allerton Conference on Communication, Control and Computing, Monticello, IL, USA, 30 September 1999; pp. 368–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Fan, X.; Luo, P.; Choudhury, S.D.; Tjahjadi, T.; Hu, C. From laboratory to field: Unsupervised domain adaptation for plant disease recognition in the wild. Plant Phenomics 2023, 5, 0038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fenu, G.; Malloci, F.M. Evaluating impacts between laboratory and field-collected datasets for plant disease classification. Agronomy 2022, 12, 2359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhammad, S.M.; Khafaga, D.S.; El-hady, W.M.; Samy, F.M.; Hosny, K.M. Deep learning and explainable AI for classification of potato leaf diseases. Front. Artif. Intell. 2025, 7, 1449329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.; Zhang, K.; Zhao, Y.; Sun, Y.; Ban, W.; Chen, Y.; Zhuang, H.; Zhang, X.; Liu, J.; Yang, T. An approach for rice bacterial leaf streak disease segmentation and disease severity estimation. Agriculture 2021, 11, 420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).