Highlights

What are the main findings?

- This survey provides a systematic overview of the layer-wise design of edge AI-enabled smart cities, and four core components supporting the systems, spanning smart applications, sensing data, learning models, and hardware infrastructure, with an emphasis on how these components interact in urban contexts.

- This survey synthesizes and organizes applications across multiple domains in smart cities, including manufacturing, healthcare, transportation, buildings, and environments, demonstrating the breadth of real-world deployments. Moreover, it identifies the inherent challenges and analyzes corresponding solutions from the perspectives of sensing data sources, on-device learning model optimization, and hardware infrastructure, to support applications across different domains.

What is the implication of the main finding?

- This survey provides an integrated roadmap that can support researchers, engineers, and policymakers in advancing edge AI technologies for smart cities.

- This survey highlights open challenges and identifies future research directions for advancing more efficient, resilient, and intelligent urban ecosystems.

Abstract

Smart cities seek to improve urban living by embedding advanced technologies into infrastructures, services, and governance. Edge Artificial Intelligence (Edge AI) has emerged as a critical enabler by moving computation and learning closer to data sources, enabling real-time decision-making, improving privacy, and reducing reliance on centralized cloud infrastructure. This survey provides a comprehensive review of the foundations, challenges, and opportunities of edge AI in smart cities. In particular, we begin with an overview of layer-wise designs for edge AI-enabled smart cities, followed by an introduction to the core components of edge AI systems, including applications, sensing data, models, and infrastructure. Then, we summarize domain-specific applications spanning manufacturing, healthcare, transportation, buildings, and environments, highlighting both the softcore (e.g., AI algorithm design) and the hardcore (e.g., edge device selection) in heterogeneous applications. Next, we analyze the sources of sensing data generation, model design strategies, and hardware infrastructure that underpin edge AI deployment. Building on these, we finally identify several open challenges and provide future research directions in this domain. Our survey outlines a future research roadmap to advance edge AI technologies, thereby supporting the development of adaptive, harmonic, and sustainable smart cities.

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

Smart cities have emerged as a central focus with the rapid development of the Internet of Things (IoT), Cyber–Physical Systems (CPS), Artificial Intelligence (AI), and 5G wireless communication technologies [1,2,3,4,5]. Smart cities are not only a research frontier but also a transformative concept that directly affects the daily lives of citizens. They enable more reliable public transportation, faster emergency responses, cleaner air through intelligent environmental monitoring, optimized energy usage in buildings, and improved healthcare through real-time monitoring and predictive services. Every day, billions of interconnected devices and sensors in urban environments generate unprecedented volumes of data, which must be processed, analyzed, and acted upon in real time. By leveraging IoT, CPS, AI, and next-generation wireless communication technologies [6,7,8], smart cities provide a rich opportunity to design intelligent solutions that can address pressing urban challenges while enhancing the efficiency, resilience, and sustainability of city services.

1.2. Motivations

Edge Artificial Intelligence (Edge AI) has recently attracted significant attention because it brings learning and inference closer to data sources, reducing reliance on centralized cloud infrastructures [9,10,11]. This paradigm is especially important for smart city applications, where rapid response, privacy preservation, and energy efficiency are critical. Traditional cloud-centric approaches often fall short due to latency, bandwidth, privacy, and reliability concerns, particularly when crucial decisions must be made instantly for transportation safety, healthcare monitoring, or energy management. However, by enabling low-latency analytics directly on edge devices, edge AI empowers domains such as traffic management, environmental monitoring, healthcare, and industrial automation to operate more effectively.

Edge AI is also a natural fit for smart city services because it aligns well with the highly distributed, resource-constrained, and dynamic nature of urban systems. City infrastructure involves thousands of heterogeneous devices deployed across diverse locations, many of which cannot afford continuous connectivity to distant data centers. By processing data locally, edge AI reduces communication overhead, increases scalability, and allows services to remain resilient even under network disruptions. Furthermore, the proximity of edge intelligence enables context-aware decision-making that can adapt to local conditions, which is essential for personalized healthcare, adaptive traffic control, and energy-efficient building management. These advantages make edge AI a compelling paradigm for building the next generation of intelligent, responsive, and sustainable urban services.

The motivation for this survey stems from the need to provide an integrated view of edge AI in applied smart city subdomains, in contrast to existing surveys that typically focus on a single and isolated subdomain. For example, prior surveys [12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22] each concentrate on one or a few specific application areas. More importantly, to the best of our knowledge, there is no unified perspective that systematically highlights the common aspects shared across subdomains, such as data sources, learning models, and hardware infrastructure. This survey addresses that gap by proposing a unified taxonomy that spans real-world applications, sensing data, learning models, and hardware infrastructure, thereby clarifying the role of edge AI across the smart city landscape. Our work aims to serve researchers seeking to develop algorithms and models for edge intelligence, engineers and practitioners designing edge infrastructures, and policymakers interested in this domain. By offering a structured overview and identifying open research directions, this survey aims to guide interdisciplinary communities in advancing edge AI for smart cities.

1.3. Search Strategy for Literature

The papers were retrieved primarily from four databases: IEEE Xplore, ACM Digital Library, Elsevier, and arXiv. We focused on peer-reviewed journals and conference proceedings, which are publicly accessible. The search strategy employed a three-level query structure combining (i) general terms (e.g., edge AI, smart cities), (ii) domain-specific keywords (e.g., manufacturing, healthcare, transportation, buildings, environment), and (iii) technical descriptors (e.g., model compression, federated learning, edge data centers, hardware–software co-design, etc.). In addition, Boolean operators (AND, OR) and exclusion filters (-survey, -review) were applied. This final corpus reviews 241 papers and reports, with 215 works published between 2019 and 2025, reflecting the rapid growth of edge AI research in smart cities. Additionally, a smaller subset of 26 foundational works from 2011 to 2018 provides important conceptual baselines in this domain.

1.4. Related Surveys for Edge AI Empowered Smart Cities

Table 1 summarizes existing surveys on edge AI for smart cities. Earlier works focus on specific domains, such as geographic information systems (GISs) [12], microgrids [13], healthcare [15,18], public safety [16], or transportation video surveillance [17]. Others emphasize broader trends and requirements across applications [14], machine learning methods [19], or the integration of edge AI with blockchain [20]. More recent surveys review architectures and frameworks [21] or highlight TinyML for lightweight urban sensing [22]. While valuable, these studies are either domain-specific or limited in scope, underscoring the need for a comprehensive review that integrates applications, sensing data, learning models, and hardware infrastructures.

Table 1.

A Comparative Analysis of Existing Surveys Related to Edge AI for Smart Cities.

Compared with these existing works, our survey offers a more comprehensive and integrative perspective, covering the entire ecosystem of edge AI for smart cities by bringing together four complementary components: applications, sensing data, learning models, and hardware infrastructure. This holistic framing allows us to highlight cross-layer challenges, identify synergies among sensing, communication, computing, and control, and propose forward-looking research directions. Therefore, our work fills a critical gap by not only benchmarking existing studies but also providing an integrated roadmap that can support researchers, engineers, and policymakers in advancing edge AI technologies for smart cities.

1.5. Our Contributions

The contributions of this survey can be summarized as follows:

- First, this survey provides a systematic overview of the layer-wise design of edge AI-enabled smart cities, and four core components that support the systems, spanning smart applications, sensing data, learning models, and hardware infrastructure, with an emphasis on how these components interact in urban contexts.

- Second, it synthesizes and organizes applications across multiple domains in smart cities, including manufacturing, healthcare, transportation, buildings, and environments, demonstrating the breadth of real-world deployments.

- Third, it categorizes the inherent challenges and analyzes corresponding solutions from the perspectives of sensing data sources, on-device learning model optimization, and hardware infrastructure, to support applications across different domains.

- Finally, it highlights open challenges and identifies future research directions for advancing more efficient, resilient, and intelligent urban ecosystems.

1.6. Survey Road-Map

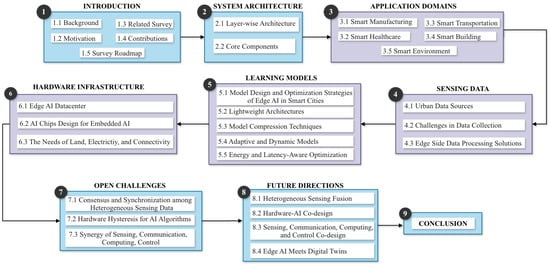

As illustrated in Figure 1, we now provide a road map of the survey. The survey is structured to provide a comprehensive understanding of the edge AI ecosystem for smart cities. In particular, Section 2, the summary section, discusses our five focused heterogeneous domains, e.g., manufacturing, healthcare, transportation, buildings, and environment. Specifically, it presents a system architecture for edge AI-empowered smart cities, outlining the envisioned layer-wise design and its core components, e.g., spanning applications (in Section 3), sensing data (in Section 4), learning models (in Section 5), and hardware infrastructure (in Section 6). They collectively provide a comprehensive understanding of how edge AI supports smart-city applications from data collection to computation and deployment. Particularly, Section 3 surveys recent edge AI applications across five heterogeneous domains, namely manufacturing, healthcare, transportation, buildings, and environment. Each application is analyzed with respect to its deployed edge devices, learning algorithms, main contributions, benefits, and identified gaps. Section 4 shifts the focus to the data aspect, discussing sensing data sources, challenges, and edge-side data processing solutions. Section 5 turns to edge AI learning models, covering lightweight design, model compression, dynamic models, and energy-aware optimization. Section 6 reviews edge AI hardware infrastructures that enable these edge-intelligent systems, including data centers, chip design, and supporting resources in land, electricity, and networking connectivity. Section 7 provides several open challenges, including data heterogeneity, hardware hysteresis, the need for synergy across sensing, communication, computing, and control as well as ethical, governance and policy, security, and privacy considerations. Section 8 explores future research directions, including heterogeneous sensing fusion, hardware–AI co-design, system-level co-design, and integrations between edge AI and digital twins. Finally, Section 9 concludes with final remarks and reflections.

Figure 1.

A Survey Road-map Highlighting the Structure of this Survey.

2. System Architecture for Edge AI-Empowered Smart Cities

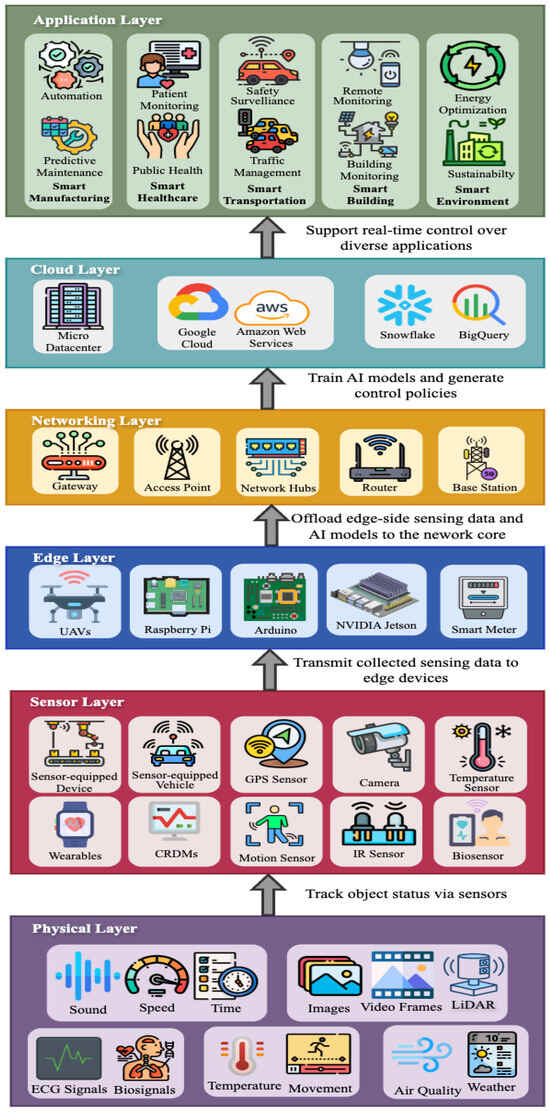

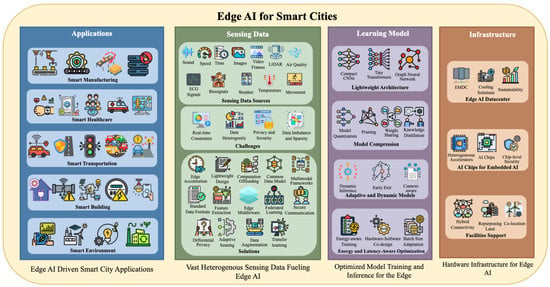

This section presents the overall architecture for edge AI-empowered smart cities. We present two complementary views of the edge AI ecosystem. First, we introduce a vertical view of architecture (Figure 2) that shows how sensors collect data, edge and cloud systems process it, and applications use the results to control city services. Second, we present a horizontal view organized around four core components as shown in Figure 3: applications that define system requirements, sensing data that fuels intelligence, learning models that enable efficient on-device computation, and infrastructure that provides the hardware backbone. Together, these two perspectives, e.g., vertical layering and horizontal components, provide a complete architectural understanding of how edge AI systems are structured and deployed in smart-city contexts.

Figure 2.

The Envisioned Layer-wise Architecture for Edge AI-Empowered Smart Cities.

Figure 3.

Core Components of Edge AI for Smart Cities, Spanning Applications, Sensing Data, Learning Models, and Infrastructure.

2.1. Our Envisioned Layer-Wise Architecture for Edge AI-Empowered Smart Cities

The envisioned architecture for edge AI in smart cities follows a multi-layer design that integrates physical sensing, intelligent edge computing, networking, cloud processing, and diverse applications, as illustrated in Figure 2. This design builds on the foundations of edge intelligence paradigms and smart city [11,23,24]. The hierarchical Physical–Edge–Cloud structure is adopted from classical CPS-related literature [4,8,25,26], which provides a structural basis for sensing, computing, and control. The component definitions and inter-layer relationships extend from edge intelligence frameworks [11,23], articulating how sensing, computation, and networking elements interconnect. The design incorporates the smart-city perspective discussed in [14], thereby offering a unified model.

Although Figure 2 adopts the layered organization with features inspired from existing IoT and CPS architectures mentioned above, there are two distinct aspects we need to highlight: First, the cloud layer is explicitly incorporated rather than implicit in the referred architectures [11,23,24]. Several surveyed applications, particularly in the smart transportation, health, and environment sub-domains, rely heavily on cloud resources for analytical functions at scale that are difficult or inefficient to execute at the edge, including training models using data collected over long periods or across multiple sites, maintaining updated models, and supporting system-wide coordination. By explicitly representing this cloud–edge separation, the framework clarifies how edge intelligence and cloud computation are distributed and synergized in practice. Second, this framework delineates concrete components and responsibilities within each layer, rather than presenting them solely at an abstract level. For example, the edge layer identifies specific devices observed in the surveyed studies, such as UAVs, Raspberry Pi platforms, NVIDIA Jetson modules, and smart meters, thereby reflecting actual deployment practices.

From the bottom to the top, specifically, at the physical layer, urban environments are monitored through rich sensing modalities such as sound, images, biosignals, weather, and air quality, which provide the raw foundation for focusing on objects enabling their intelligent services at upper layers. The sensor layer builds on this by employing heterogeneous devices, including cameras, GPS modules, wearables, environmental sensors, and biosensors, to capture domain-specific data in real time. The edge layer leverages resource-constrained but intelligent devices such as Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs), Raspberry Pi, Arduino boards, NVIDIA Jetson modules, and smart meters, which locally process sensing data and enable low-latency inference. These are supported by the networking layer, consisting of gateways, routers, access points, hubs, and base stations that interconnect distributed edge devices and transmit both raw and pre-processed data. The cloud layer provides powerful computing infrastructure such as data centers and commercial platforms (e.g., Google Cloud, Amazon Web Services (AWS), Snowflake, and BigQuery) that train large-scale models, manage city-wide data, and generate optimized control policies. At the top, the application layer enables smart city services, including predictive maintenance in manufacturing, patient monitoring in healthcare, traffic management in transportation, building monitoring, and energy optimization in urban environments. Together, these layers ensure that sensing, communication, computing, and control are integrated to provide real-time, reliable, and adaptive intelligence for urban operations.

2.2. Core Components for Edge AI-Empowered Smart Cities

The architecture presented in Figure 3 outlines the structural organization of this survey and presents our original framework, highlighting how edge AI interconnects four key components: applications, sensing data, learning models, and infrastructure into a unified framework for the smart-city ecosystem. To the best of our knowledge, we are the first to provide an integrated, end-to-end design for edge AI systems, from data generation through model training, hardware deployment, and application delivery. This design enables identification of cross-component dependencies observed in the surveyed literature: sensing data characteristics influence model design choices, model requirements determine hardware platform selection, and infrastructure constraints shape feasible applications.

The first is applications, where edge AI drives innovation across domains, including smart manufacturing, healthcare, transportation, buildings, and environmental management, enabling context-aware and domain-specific services. The second is sensing data, which fuels edge AI by capturing multimodal information, yet also introduces challenges such as heterogeneity, real-time constraints, privacy concerns, and data imbalance. Addressing these requires solutions like lightweight design, adaptive sensing, federated learning, differential privacy, and secure communication. The third component is the learning model, where techniques such as lightweight architectures (e.g., compact CNNs, Tiny Transformers, graph neural networks), model compression (e.g., quantization, pruning, knowledge distillation), adaptive and dynamic models (e.g., early exit, context-aware inference), and energy- and latency-aware optimization strategies ensure efficient model training and inference at the edge. Finally, the infrastructure component provides the hardware backbone, including edge data centers with sustainable cooling, embedded AI chips with security features, and supporting facilities such as hybrid connectivity, land repurposing, and co-location. These components interact seamlessly to enable scalable, efficient, and sustainable edge AI solutions tailored for the complex demands of smart cities.

3. Edge AI Applications Across Heterogeneous Domains in Smart Cities

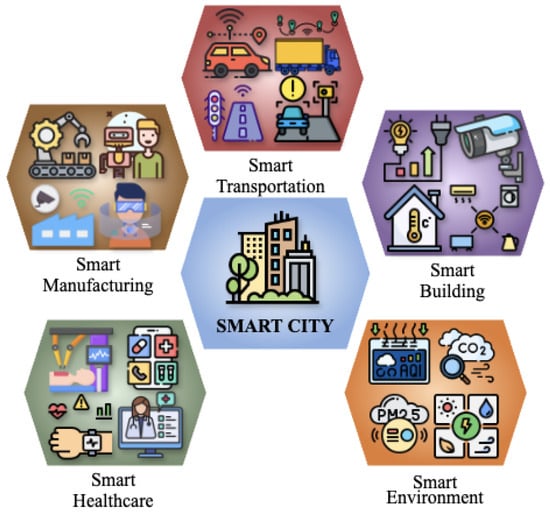

In this section, we systematically discuss five distinct domains in smart cities, including smart manufacturing, smart healthcare, smart transportation, smart buildings, smart environments, and describe how edge AI can be leveraged in each domain, as illustrated in Figure 4. These domains represent the core components of urban life: how people work, maintain health, move, inhabit spaces, and interact with their surroundings, and were selected based on prior works on edge AI and smart city architectures [14,20,27]. Each row in the Table 2, Table 3, Table 4, Table 5 and Table 6 describes an application along with algorithm, edge device, contribution, benefits, and limitations to ensure consistency. The tabular format was adapted from [28], and refined to align with the smart-city context.

Figure 4.

The Five Considered Sub-domains in Smart Cities: Smart Manufacturing, Smart Healthcare, Smart Transportation, Smart Building, and Smart Environment.

Table 2.

Edge AI Applications in Smart Manufacturing Domains.

Table 3.

Edge AI Applications in Smart Healthcare Domains.

Table 4.

Edge AI Applications in Smart Transportation Domains.

Table 5.

Edge AI Applications in Smart Building Domains.

Table 6.

Edge AI Applications for Smart Environment Domains.

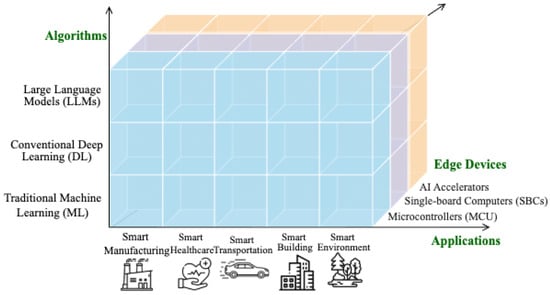

Figure 5 provides an overview of the five domains, showing how algorithmic design and hardware choices meet domain-specific requirements. In particular, smart Manufacturing focuses on automation, predictive maintenance, and industrial efficiency; Smart Healthcare enables telemedicine, remote monitoring, and data-driven diagnosis; Smart Transportation enhances mobility through traffic optimization, autonomous driving, and emergency response; Smart Building emphasizes energy management, occupant comfort, and security; and Smart Environment addresses air quality, waste management, and disaster preparedness. Although each domain pursues distinct objectives, they share common challenges, including real-time inference, limited edge resources, privacy and security concerns, and the scalability of heterogeneous systems. Thus, we will systematically summarize both the AI algorithms design and hardware selections in each domain, as shown in Figure 5, in what follows.

Figure 5.

Applications in Edge AI for Smart Cities.

3.1. Smart Manufacturing Domains

Integrating edge AI into manufacturing supports predictive maintenance, process automation, quality inspection, and supply chain optimization. Several works address the integration of edge and cloud resources to balance real-time processing with centralized coordination. Li et al. [29] developed a hybrid computing framework with two-phase resource scheduling on Raspberry Pi 3, ensuring low-latency task execution for Industry 4.0 transitions. Building on this paradigm, Yang et al. [32] proposed AI-Mfg-Ops, a software-defined edge–cloud architecture for smart monitoring, analysis, and execution. Tang et al. [33] introduced a multi-agent system with Intelligent Production Edges (IPEs) enabling dynamic reconfiguration and self-organized control in mixed-flow production. Ying et al. [34] validated an edge–cloud platform integrated with quality management systems on a semiconductor production line, achieving reductions in downtime (12%), defects (20%), and costs (up to 80%).

In the context of production scheduling and resource management, Lin et al. [30] applied Multi-class Deep Q-Network (MDQN) for job-shop scheduling across distributed edge devices, while Ing et al. [31] showed how small- and medium-sized enterprises can adopt Deep Learning (DL) and Deep Reinforcement Learning (DRL) within existing quality management systems (QMS) to support AI-driven resource allocation. For condition monitoring and fault detection, Vermesan et al. [35] implemented ML and DL models including K-Means, Random Forest, SVM, and CNN on ARM Cortex-M4 processors in a soybean processing facility, improving productivity through Industrial IoT (IIoT) enabled sensing and control.

Beyond conventional industrial AI applications, Rane et al. [36] examined applications of generative AI tools such as ChatGPT and Bard in construction, covering robotics, building information management, and AR/VR systems, and outlined a cyclical AI framework for continuous learning. Xu et al. [37] investigated embodied AI systems where robots, sensors, and actuators enable self-learning and swarm intelligence in Industry 5.0 settings, identifying opportunities for improved productivity, sustainability, and worker well-being. Addressing energy consumption in IIoT environments, Zhu et al. [38] designed a heterogeneous edge computing framework using DRL-based scheduling on NVIDIA Jetson and Raspberry Pi 4B platforms, achieving 70–80% energy reduction compared to static and FIFO scheduling approaches.

3.2. Smart Healthcare Domains

Integrating edge AI into healthcare links patient monitoring, resource management, disease prediction, emergency response, and public health. These applications enable faster diagnostics, optimized resource use, proactive prevention, and comprehensive safety monitoring.

In the patient monitoring domain, Hayyolalam et al. [28] developed a framework employing DRL across distributed edge–cloud infrastructure to facilitate early disease detection while reducing medical costs, latency, and network load. Multiple works address continuous monitoring through wearable and IoT devices. Putra et al. [39] designed a non-invasive glucose monitoring system using LeNet-5 CNN and ANN on ESP32 microcontrollers with PPG sensors, offering a pain-free alternative to invasive methods. Putra et al. [40] integrated CNN-RNN models with You Only Look Once (YOLO) to process multimodal sensor and image data at edge nodes for real-time diagnostics and personalized care. Pradeep et al. [41] combined health-monitoring sensors, Raspberry Pi, and NVIDIA Jetson Nano with Random Forest models for continuous monitoring and secure remote consultation. Akram et al. [42] surveyed ML, Federated Learning (FL), TinyML, and hardware acceleration strategies for privacy-preserving cardiac monitoring, emphasizing differential privacy, model quantization, and Field Programmable Gate Array (FPGA) acceleration to address latency, energy, and personalization challenges.

Resource management, disease prediction, and emergency response applications leverage edge AI for operational efficiency. Rathi et al. [43] developed a framework that processes patient sensor data at edge nodes, prioritizing cases using max-heap queues and allocating resources through category-specific min-heaps, achieving response times between 0.2–0.4 units in hospital network simulations. Badidi [44] reviewed edge AI for early disease detection through wearable devices and medical sensors, highlighting CNN, RNN, and collaborative training for real-time health risk analysis. Ahmed et al. [45] designed ACA-R3, an edge-enabled protocol for autonomous connected ambulances (ACAs) that monitors patient vitals and optimizes routes based on GPS and traffic data, reducing handover time and improving emergency coordination through real-time telemedicine integration.

Addressing public health and safety, Thalluri et al. [46] incorporated edge computing into environmental monitoring, processing environmental data locally on Raspberry Pi devices with decision tree models generating automated alerts for abnormal levels. Sengupta et al. [47] deployed high-resolution network (HRNET), YOLO, Region-based CNN (R-CNN), Fully-CNN (F-CNN), and Mask R-CNN techniques on heterogeneous edge devices for contact tracing, mask detection, and social distancing monitoring from surveillance feeds, enhancing workplace safety compliance during epidemics. Choudhury et al. [48] implemented YOLOv4 with composite attention and deep pre-trained models (DPTMs) on Grove AI Hat and Raspberry Pi for mask detection, contact tracing, and cyber-threat detection, reducing latency through bandwidth optimization and edge parallelism to support data-driven pandemic response.

3.3. Smart Transportation Domains

Safety surveillance leverage edge AI for rapid detection of critical events while reducing latency, bandwidth consumption, and cloud dependence. Ke et al. [49] implemented Single Shot Detector (SSD) Inception on NVIDIA Jetson TX2 with dashcam, GPS, and Arduino for near-crash detection using multi-threaded linear-complexity tracking of objects. Neto et al. [50] developed MELINDA, distributing face detection and recognition tasks across hardware-accelerated edge devices using SSD MobileNet and FaceNet, processing video streams 33% faster than baseline approaches for unauthorized access alerts. Vision-based surveillance extends to diverse scenarios: Huu et al. [51] deployed YOLOv5 on Jetson Nano for abnormal activity detection, Broekman et al. [52] implemented YOLOv4-tiny on UAV-mounted edge hardware for vehicle classification, and Rahman et al. [53] combined CNNs, Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM), and YOLOv5 on Raspberry Pi and Jetson devices for real-time monitoring with zero-trust architecture. Soy et al. [54] applied kNN and Dynamic Time Warping on Raspberry Pi Pico to monitor aggressive driving on public transport, enabling early detection and proactive safety alerts.

Traffic management applications optimize signal control and network operations at the edge. Irshad et al. [56] designed IB-SEC, a secure edge platform employing African Buffalo Optimization (ABO) and distributed hash functions with Medium Access Control (MAC) protocols to adapt to network conditions and improve throughput and latency. Alkinani et al. [57] applied XGBoost to sensor data from mobile phones and vehicle-mounted devices for real-time traffic analysis. Vision-based approaches address traffic signal optimization, Lee et al. [58] implemented compressed video analysis model with CNNs-YOLOX and LT2 on Jetson AGX Xavier for real-time intersection monitoring in Pyeongtaek City, South Korea, reducing delays during non-peak hours, while Hazarika et al. [59] developed a dynamic traffic light system on Raspberry Pi 3 using YOLO and Rapid Automatic Keyword Extraction (RAKE) to adjust signal timing based on traffic density and inter-junction coordination. Murturi et al. [55] extended to urban logistics, executing the Expressive Numeric Heuristic Search Planner (EHNSP) on distributed IoT devices for real-time waste collection route optimization in densely populated areas.

For intelligent transportation systems (ITSs), Moubayed et al. [60] formulated V2X service placement as binary integer programming and proposed G-VSPA, a low-complexity greedy heuristic for deployment across eNBs and Roadside Units (RSUs), achieving near-optimal performance with reduced computational complexity. Jeong et al. [61] implemented FPGA-based license plate recognition using kNN on Raspberry Pi for power-efficient processing. Chavhan et al. [62] developed an AI-IoT multi-agent system applying Radial Basis Function Neural Network (RBF-NN) and stochastic queuing models on RSUs to process real-time V2X data, achieving 25% CO2 emission reduction while cutting energy use and congestion. Yang et al. [63] designed a self-learning Spiking Neural Network (SNN) navigation system on neuromorphic hardware for low-power cognitive routing in IoV, while Rong et al. [64] developed STGLLM-E, combining RoadSort with spatio-temporal modules and Generative Pre-trained Transformer (GPT) for traffic flow prediction in 6G-integrated autonomous transport systems, outperforming baselines in accuracy and training efficiency. Liu et al. [65] proposed Edge-MuSE, a multi-task system on Jetson Xavier NX performing visibility estimation, dehazing, road segmentation, and surface condition classification for improved environmental perception with lower latency and enhanced privacy.

3.4. Smart Building Domains

Integrating edge AI into smart buildings enables intelligent energy management, security, maintenance, and occupant-aware services, thereby enhancing sustainability, efficiency, safety, and comfort through real-time monitoring and adaptive control. In the context of energy management, Bajwa et al. [69] reviewed AI-enabled building management systems employing DL, Hybrid-DL, Deep Belief Networks (DBNs), Variational Autoencoders (VAEs), and DRL with IoT sensors, finding that these techniques improved energy efficiency while enhancing maintenance and comfort. Chen et al. [66] developed a Smart Home Energy Management System (SHEMS) prototype using fog–cloud architecture with two-stage ANN-based non-intrusive appliance monitoring (NIALM), supporting scalable residential demand-side management with real-time alerts. Márquez-Sánchez et al. [67] combined FL and DRL in an adaptive edge framework that optimizes energy consumption while accounting for occupant comfort and preferences, enabling personalized and sustainable management. Yang et al. [75] applied spherical fuzzy CRITIC-COCOSO decision algorithms to evaluate AI-based models for low-energy buildings, improving decision-making under uncertainty for strategies balancing sustainability, economic growth, and energy efficiency.

Monitoring and detection systems address maintenance, occupancy, and security. Atanane et al. [70] implemented TinyML-based leakage detection using CNN variants (EfficientNet, ResNet, AlexNet, MobileNet) on Arduino Nano33 BLE, analyzing sensor data for deviations in flow, pressure, or vibration to enable real-time detection with minimal intervention. Ahamad et al. [71] developed a real-time people tracking and counting system using SSD, MobileNet, and novel algorithms on Intel NUC12 Pro Mini PC, achieving 97% accuracy at 20-27 frames per second (FPS) across varied lighting conditions. Vijay et al. [72] employed CNN and YOLOv8 with CCTV cameras for customer behavior monitoring, heat map generation, and anomaly detection at the edge, reducing resource use while improving experience and security. Security-focused applications include Craciun et al. [73], who designed an intrusion detection system using hybrid XGBoost models on Orange Pi for real-time threat detection against DDoS attacks, and Reis et al. [74], who implemented Isolation Forest and LSTM Auto-Encoder (LSTM-AE) on Raspberry Pi and Jetson Nano for low-latency, privacy-preserving anomaly detection. Generative AI has also been explored as a decision-support tool for smart building integration within broader smart city ecosystems. Shahrabani et al. [68] employed Google Bard and OpenAI ChatGPT-3 to evaluate smart building integration into smart cities, assessing resilience, efficiency, and sustainability across energy, transportation, water, waste, and security domains.

The surveyed smart building applications reveal two distinct edge AI deployment patterns. First, application algorithms range from classical decision trees [75] and traditional CNNs to recent explorations of large language models for building evaluation [68] and advanced deep learning frameworks [69,70,74]. The algorithms are diverse compared to manufacturing or transportation, where CNNs and YOLO variants dominate. Second, smart building works exhibit limited real-world validation: most remain conceptual frameworks [67,70], prototypes lacking large-scale testing [66], or deployments with evaluation gaps [68,73,75]. This contrasts with transportation, where real-world traffic data and deployed camera systems are more common. The gap between algorithmic sophistication and deployment maturity suggests smart building edge AI remains in an earlier development stage.

3.5. Smart Environment Domains

Integrating edge AI into environmental monitoring enables real-time sensing of air quality, climate, energy, and mobility conditions, supporting sustainable urban development through low-latency perception, efficient resource use, and proactive pollution and safety management. In environment monitoring, Silva et al. [76] developed a hardware–software co-design pipeline for wearable edge AI using smart helmets with Raspberry Pi and Jetson devices. Using MLP and CNN models, the system enabled on-device ecological monitoring in environments with limited network connectivity. Almeida et al. [77] applied multiple neural network models at the edge to measure temperature, humidity, CO2 levels, and human traffic for low-cost workplace environmental monitoring. Liu et al. [65] implemented Edge-MuSE on NVIDIA Jetson Xavier NX, integrating visibility estimation, dehazing, road segmentation, and surface condition classification for low-latency, privacy-preserving environmental perception in traffic contexts.

Addressing sustainability, Chavhan et al. [62] designed RBF-NN and stochastic queuing models on RSUs to process real-time V2X data, achieving 25% CO2 emission reduction while decreasing energy use and noise pollution. Yang et al. [63] applied self-learning SNNs on neuromorphic architecture with fault-tolerant routing for energy-efficient, low-power traffic navigation. Rehman et al. [78] combined CNNs, MLPs, and A* search algorithms in a deep state-space model for urban fire surveillance, enhancing detection accuracy and emergency response optimization.

Environmental edge AI applications are closely tied to transportation infrastructure, linking sensing of emissions, air quality, and weather conditions with traffic management and vehicle navigation. This indicates that environmental monitoring often acts as a cross-cutting capability rather than a standalone domain, enhancing other smart city services: traffic systems can reduce emissions [62,63,65], and workplace monitoring can account for environmental factors [77]. These applications also use a wider variety of hardware than other domains, including wearable edge devices [76], standard embedded systems [65,77], vehicle-integrated sensors [62], and specialized neuromorphic architectures [63]. In contrast, smart building and transportation systems tend to rely on a narrower set of platforms, such as Raspberry Pi or Jetson devices, reflecting environmental monitoring’s distributed deployment across diverse infrastructures rather than centralized facilities.

3.6. Common Patterns and Limitations Across Five Sub-Domains

Edge AI implementations across each smart city domain share common patterns, yet also face domain-specific limitations that shape future research in edge deployment.

Common patterns across five sub-domains: Across smart manufacturing, healthcare, transportation, buildings, and environments, several patterns can be observed. Applications employ a wide range of edge devices, from low-power sensors and embedded processors to GPU-enabled platforms, resulting in similar trade-offs among computational capability, energy consumption, and real-time performance. To accommodate resource constraints, many applications adopt lightweight learning approaches, such as compact convolutional models, simplified temporal models, or classical machine learning techniques. Despite differences in sensing modalities, all domains face challenges in feature extraction, data quality, and robustness under real-world operating conditions. Additionally, applications handling sensitive data, particularly in healthcare, transportation, and smart buildings, favor on-device processing to minimize data transmission beyond the edge.

Common limitations and domain-specific limitations: Despite similarities, recurring limitations are evident across five domains. Validation studies are often small-scale, including single-facility investigations in manufacturing, short-duration trials in transportation, limited participant datasets in healthcare, prototype deployments in buildings, and idealized sensor setups in environmental monitoring. Simulation-based evaluation is prevalent, particularly in transportation and healthcare, whereas smart building and environment often remain conceptual or are tested only under controlled conditions. Moreover, robustness to real-world variability is rarely addressed, with limited attention to adverse weather, network disruptions, hardware failures, or heterogeneous operational conditions. Each domain also exhibits unique constraints that further limit deployment. Manufacturing systems struggle with interoperability challenges and evaluation gaps across heterogeneous production setups. Healthcare models rely on simulated or limited patient data and often lack standardized datasets. Transportation applications face issues with poor video quality, network interference, and limited-duration testing. Smart building prototypes rarely undergo large-scale or stress testing and typically evaluate only a narrow range of scenarios. Environmental monitoring systems are distributed across diverse infrastructures, introducing hardware heterogeneity, sparse sensor coverage, and difficulties in aggregating local measurements into actionable city-wide insights.

Hardware trade-offs: Hardware selection further reflects these domain-specific trade-offs. NVIDIA Jetson devices (TX2, Nano, Xavier, AGX Xavier) offer high computational capability with integrated GPU acceleration, supporting real-time inference for complex models, yet their higher power consumption and cost constrain deployment in energy-limited or large-scale networks. Raspberry Pi devices (Pi 3, Pi 4, Pi Pico) offer moderate performance at lower cost and power, making them suitable for diverse applications, though they struggle with computationally intensive tasks. Microcontrollers (ESP32, ARM Cortex-M4, Arduino) enable ultra-low-power, battery-operated, or energy-harvesting deployments but are limited to simple models due to limited memory and processing capacity. FPGA platforms offer reconfigurable hardware with custom acceleration and predictable latency, but require specialized expertise and longer development cycles.

In summary, edge AI applications across smart city domains exhibit technical feasibility, leveraging lightweight models, on-device processing, and a range of hardware platforms. However, the predominance of small-scale validations, simulation-based evaluations, and limited robustness to real-world variability underscores that applications remain at an experimental stage.

4. Edge AI Sensing Data for Smart Cities

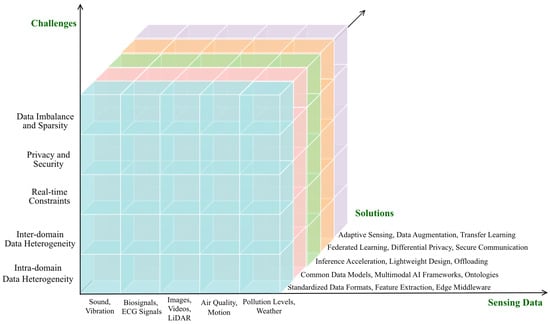

Sensing data-fueled smart cities provide the foundation for diverse edge AI applications by enabling real-time, multimodal insights from urban infrastructure. In this section, we discuss heterogeneous urban sensing data sources, challenges in data collection, and corresponding solutions. Figure 6 provides a high-level view of this section, illustrating how different sensing modalities pose challenges and corresponding techniques to address them.

Figure 6.

Sensing Data Types in Edge AI for Smart Cities.

4.1. Urban Sensing Data Sources for Edge AI-Enabled Smart Cities

In smart cities, different types of sensing data, shown in Table 7, are collected across multiple domains to enable context-aware and adaptive edge AI applications:

Table 7.

Sensing Data Sources.

- Smart Manufacturing Applications: They leverage microphones, inertial measurement units (IMUs), and acoustic emission sensors to capture sound and vibration data for fault diagnosis [79,80]. Industrial and mechanical sensors measure rotation, torque, spindle speed, load, thickness, voltage, current, proximity, pressure, optical, and temperature, enabling anomaly detection and equipment failure prediction, thereby supporting uninterrupted production flow [81]. Time, speed, torque, and temperature measurements are further integrated with thermal models to predict thermal displacement in machining processes [82].

- Smart Healthcare Applications: They employ a variety of sensors to support continuous monitoring and early diagnosis. Electroencephalogram (EEG) sensors generate brain signals (EEG signals) that are analyzed for pathology detection [83]. Wearable devices collect physiological signals, including electrocardiogram (ECG) signals, in a non-invasive manner, enabling personalized health monitoring [84], Myocardial infarction detection [85], and continuous cardiac monitoring [86]. Biosensors measure temperature, blood pressure, pulse rate, and SpO2, supporting medical diagnosis [87] and remote patient monitoring [88]. In addition, breath sensors analyze exhaled air to facilitate early detection of respiratory diseases [89].

- Smart Transportation Applications: They employ environmental sensors and cameras together to measure temperature, humidity, and images for multi-task traffic surveillance [90]. Beyond surveillance, cameras capture image and video frames, which are analyzed for traffic monitoring [91], detect hazards [92], and detect vehicles [93]. LiDAR and radar provide point clouds and radar returns supporting hazard detection [92] and enable real-time decision making in dynamic traffic environments [94].

- Smart Building Applications: They deploy environmental sensors to monitor air quality, humidity, temperature, as well as smoke levels, which are analyzed to enhance energy efficiency and reduce consumption [95,96,97,98]. Motion sensors detect occupant presence, enabling reliable occupancy detection that supports adaptive control of indoor conditions [99].

- Smart Environment Applications: They rely on pollution sensors to monitor air quality, particulate matter, carbon dioxide (CO2), and nitrogen oxide (NOx) levels, supporting continuous air quality monitoring [100,101]. Environmental sensors measure temperature, humidity, pressure, weather conditions, and light intensity, which are utilized to enhance energy efficiency [102,103].

4.2. Challenges and Effective Edge Side Solutions in Smart City Sensing Data Collections

Despite the promise of pervasive sensing for smart cities, several challenges emerge when collecting, managing, and utilizing urban-scale data streams. To address these challenges, effective edge-side data processing techniques are required. We now summarize several solutions for each of the challenges considered below.

4.2.1. High Heterogeneity from Sensing

We consider two types of heterogeneity in smart city applications in what follows.

Intra-domain Heterogeneity. Smart city sensing involves integrating data collected from multiple sensing modalities within each specific domain, each with distinct data formats and characteristics. For example, in smart manufacturing, vibration sensors, infrared cameras, and industrial IoT devices generate time-series signals, thermal images, and structured machine logs for predictive maintenance and process optimization. In smart healthcare, wearable devices and ambient medical IoT sensors produce biosignals such as ECG and SpO2, continuous motion data, and patient health records in both structured and unstructured forms. In smart transportation, traffic cameras and roadside LiDAR produce high-resolution video streams and 3D point clouds, respectively, while GPS devices in connected vehicles generate continuous geospatial trajectories. In smart buildings, energy meters output structured numerical readings of power consumption, motion detectors provide binary occupancy data, and environmental sensors deliver continuous measurements of temperature, humidity, and air quality.

Thus, intra-domain heterogeneity reflects the diversity of sensing modalities and data formats within a single urban domain, requiring domain-specific preprocessing and harmonization strategies. This can be mitigated through domain-specific preprocessing and harmonization.

- Standardized Data Formats provide common structures for sensor description, observation encoding, and data access, simplifying integration of heterogeneous IoT devices and enabling interoperability. Without such standards, data from diverse sources would remain fragmented and difficult to analyze efficiently. To this end, Fazio et al. [104] introduced a dual abstraction layer based on Open Geospatial Consortium Sensor Web Enablement (OGC-SWE) standards, employing SensorML for sensor descriptions, O&M for encoding observations, and SOS for data access. Their four-layer, data-centric architecture used a shared database to manage asynchronous uploads and uniformly deliver sensor information. Rubí et al. [105] proposed a OneM2M-based Internet of Medical Things (IoMT) platform to address the interoperability gaps of OpenEHR for e-health devices. The platform extended OpenEHR semantics to transform SenML data into standardized formats, such as FHIR and OpenEHR, enabling big data analytics and online processing. Beyond formatting, data preprocessing is also key to managing intra-domain heterogeneity. Krishnamurthi et al. [25] reviewed approaches including wavelet-based denoising, missing value imputation with statistical and correlation-based models, outlier detection through voting mechanisms, SVM, and Principal Component Analysis (PCA), and data aggregation methods including tree-based, cluster-based, and centralized approaches to address the challenges of real-time IoT sensor data. Similarly, Kim et al. [106] introduced Thing Adaptation Layer (TAL), which uses device-specific TAS functions to translate raw sensor outputs into standardized data formats and convert control instructions into device-specific commands, enabling uniform access through REST APIs.

- Feature Extraction Pipelines use signal processing and domain-specific engineering methods, such as the FFT for vibration data or wavelet transforms, to transform raw sensor outputs into compact, comparable representations. By reducing variability across heterogeneous signals, these pipelines enable more accurate, efficient learning on edge devices. Concerning this, Alemayoh et al. [107] proposed a new data structuring approach for sensor-based HAR, in which duplicated triaxial IMU data were formatted into single and double-channel inputs to enhance temporal–spatial feature extraction. This design improved the accuracy and efficiency of lightweight neural network models for real-time motion recognition. Arunan et al. [108] designed FedMA, an FL framework for industrial health prognostics that addresses misalignment of feature extractors across heterogeneous clients. By matching neurons with similar feature extraction functions before averaging, FedMA preserved local features and improved prognostic accuracy compared with FedAvg. In the context of remote sensing, Wang et al. [109] investigated a scene classification framework that extracts heterogeneous features, including DS-SURF-LLC (dense SURF descriptors), Mean-Std-LLC (statistical features), and MO-CLBP-LLC (multi-orientation texture patterns). These features are fused using discriminant correlation analysis to generate compact representations, while decision-level fusion is performed by combining multiple SVM classifiers through majority voting, further enhancing classification performance.

- Edge Middleware provides a lightweight software layer for ingesting, processing, and distributing heterogeneous IoT data streams. By abstracting device-specific protocols and exposing uniform APIs, middleware frameworks enable real-time analytics, interoperability, and quality-of-service support at the edge. To this end, Akanbi et al. [110] developed a distributed stream processing middleware for real-time environmental monitoring. The framework was built on a publish/subscribe architecture with Apache Kafka, ingested heterogeneous data via Kafka Connect, and processed streams using Kafka Streams with numerical models. Kim et al. [106] proposed a oneM2M-based middleware platform with an open API that provides REST interfaces for interacting with WSN devices at the localhost, local area network, and global network levels. Likewise, Gomes et al. [111] proposed the M-Hub/Context Data Distribution Layer (CDDL) middleware to acquire, process, and distribute context data with QoC provisioning and monitoring. Unlike SSDL middleware that relied on different protocols for mobile and cloud communication, CDDL employs MQTT as a single protocol for both local and remote communication, ensuring that QoS policies are applied end-to-end [16].

Inter-domain Heterogeneity. The heterogeneity across multiple domains extends to data formats (video, audio, numerical, text logs, biosignals), sampling rates (milliseconds for traffic sensors vs. hours for utility meters), and quality (noisy acoustic signals vs. structured meter readings). Bringing these sources together enables holistic applications. For example, combining transportation data with environmental sensor streams allows a city to correlate traffic congestion with air pollution exposure, informing both mobility management and public health interventions. This cross-domain fusion is fundamental to smart city intelligence but requires standardized data representations and efficient multimodal sensing fusion frameworks to overcome incompatibilities.

Thus, inter-domain heterogeneity arises when integrating multimodal data across different urban sectors, demanding cross-domain interoperability standards and multimodal AI techniques to unlock system-level intelligence in smart cities. Addressing this challenge requires fusion across data types and sectors.

- Common Data Models (CDMs) standardize how data are structured and interpreted across systems, acting as a shared semantic “language” for heterogeneous sources. By defining consistent entities and relationships, such as linking sensors to devices or associating readings with locations, CDMs enable interoperability and cross-domain integration. Peng et al. [112] proposed a Semantic Web-based method that uses an OWL integration ontology to unify health and home environment data. Their method combined HL7 FHIR, Web, WoT, and Linked Data into a semantic resource graph at the resource integration layer, enabling standardized access through semantic APIs. Ali et al. [113] proposed a semantic mediation model to address interoperability in heterogeneous healthcare services. Their framework applied the Web of Objects paradigm, incorporating virtual and composite virtual objects, semantic annotation, ontology alignment, and deep representation learning, while leveraging a Common Data Model to transform diverse data into standardized formats. Likewise, Adel et al. [114] proposed a semantic ontology-based model for distributed healthcare systems to address interoperability across heterogeneous EHR sources. These sources are transformed into OWL ontologies and merged into a unified ontology, enabling unified queries through SPARQL and Description Logic. Implementing shared ontologies (e.g., CityGML, Brick schema for buildings) provided semantic consistency across domains.

- Multimodal AI Frameworks combine heterogeneous data sources such as images, sensor readings, text, and temporal signals into unified models that capture complementary information. By jointly learning from multiple modalities, they improve accuracy, robustness, and decision-making in complex edge and IoT applications. For example, Ahmed et al. [115] investigated a multimodal AI framework to address the challenge of delayed detection and response to traffic incidents, integrated YOLOv11 for real-time accident detection, Moondream2 to generate scene descriptions, and GPT-4 Turbo to produce actionable reports. Alghieth et al. [116] proposed Sustain AI, a multimodal DL framework to address the challenge of increasing energy demand and carbon emissions in industrial manufacturing. The system integrated CNNs for defect detection, RNNs for energy prediction, and reinforcement learning (RL) for dynamic energy optimization. Reis et al. [117] proposed an IoT- and AI-driven framework that fused multimodal data from traffic sensors, environmental monitors, and historical logs, employing LSTM networks for congestion prediction and DQNs for route optimization within an edge–cloud hybrid architecture. Likewise, Ranatunga et al. [118] proposed an ontology-based data access framework to integrate heterogeneous environmental geospatial data, employing Ontop for semantic translation and PostgreSQL/PostGIS for storage. A web-based SPARQL Query Interface enabled querying and visualization. The framework enabled a unified semantic knowledge graph, which can be used for performing analysis and decision-making.

- Cross-domain Data Integration addresses the challenge of integrating information from diverse application domains, such as buildings, transportation, and healthcare, into a unified framework. For example, Valtoline et al. [119] investigated an ontology-based approach for cross-domain IoT platforms that applied a multi-granular Spatio-Temporal-Thematic (STT) data model and Semantic Virtualization to annotate heterogeneous sensor schemas with domain ontology concepts. Fan et al. [120] designed BuildSenSys, a cross-domain learning system that reused building sensing data for performing traffic prediction. The system combined correlation analysis with an LSTM-based encoder–decoder, applying cross-domain attention to capture building-traffic relationships and temporal attention to model historical dependencies.

4.2.2. Real-Time Constraints

Many smart city applications, such as adaptive traffic light control, autonomous vehicle coordination, or emergency response systems, demand rapid processing and decision-making. Latency in collecting, transmitting, or analyzing data can compromise system effectiveness and even public safety. Designing sensing pipelines that guarantee real-time performance while operating on resource-constrained edge devices is a key challenge.

Achieving these real-time requirements necessitates low-latency data processing and communication mechanisms.

- Edge Inference Acceleration combines specialized hardware and optimized software runtimes to perform ML inference on edge devices, reducing latency, conserving bandwidth, and improving privacy. For example, Wang et al. [121] designed a cloud–edge collaborative framework for pedestrian and vehicle detection by compressing YOLOv4 models via L1-regularization-based channel pruning and accelerating inference with TensorRT quantization on the NVIDIA Jetson TX2. Zhang et al. [122] proposed edgeIS, an edge-assisted framework for mobile instance segmentation that replaced the traditional “track + detect” paradigm with a “transfer + infer” mobile-edge collaboration scheme. The framework applied mechanisms like motion-aware mask transfer, contour-instructed edge inference acceleration, and content-based RoI selection, reducing latency by 48% while preserving accuracy above 0.92. Likewise, Han et al. [123] developed SDPMP, a self-adaptive dynamic programming algorithm that accelerated CNN inference by combining pipeline parallelism with inter-layer and intra-layer partitioning across heterogeneous edge devices.

- Lightweight Design for Stream Processing aims to achieve high performance while minimizing resource consumption on edge computing devices. For example, Zhang et al. [124] investigated ECStream, a lightweight edge–cloud framework for structural health monitoring that applied fine-grained scheduling of atomic and composite stream operators. This design reduced bandwidth usage by 73.01% and end-to-end latency by 20.37% on average.

- Computation Offloading transfers computationally intensive tasks from resource-limited devices to more powerful remote nodes such as Edge computing servers, Fog computing nodes, or Cloud computing clusters. In this direction, Cheng et al. [125] proposed a Lyapunov optimization-based scheme for fog computing systems, which comprised energy-harvesting mobile devices. In their approach, computation offloading, subcarrier assignment, and power allocation are jointly optimized to minimize system cost in terms of latency, energy consumption, and device weights. Liu et al. [126] proposed a two-layer vehicular fog computing architecture and designed a real-time task offloading algorithm, which classified tasks by delay, assigned them to four offloading lists, and scheduled them based on deadlines and utilization to maximize the task service ratio. Also, Gao et al. [127] proposed PORA, a predictive offloading and resource allocation scheme for multitier fog computing systems. The system formulated the problem as a stochastic network optimization and applied Lyapunov-based decomposition to enable distributed online offloading, thereby minimizing time-average power consumption while ensuring queue stability.

4.2.3. Privacy and Security Concerns

Urban sensing often involves sensitive data, such as high-resolution video, geolocation traces, or health-related signals. Without robust privacy-preserving mechanisms, these data streams raise risks of surveillance, identity leakage, or malicious exploitation. Ensuring data confidentiality, secure transmission, and compliance with regulatory frameworks (e.g., GDPR, HIPAA) is critical for public trust in smart city systems. Protecting citizen data thus requires privacy-preserving and secure edge computing techniques.

- Federated Learning trains multiple edge devices without sharing raw data. Each device trains a local model and sends only updates for aggregation, which preserves privacy and reduces bandwidth usage. For instance, Liu et al. [128] proposed P2FEC, which exchanged gradients instead of raw data, and applied secure multi-party aggregation during initialization, training, and updating stages to preserve privacy. Li et al. [129] proposed ADDETECTOR, an FL-based smart healthcare system for Alzheimer’s disease detection that collected user audio via IoT devices and applied topic-based linguistic features, differential privacy, and asynchronous aggregation to preserve privacy across user, client, and cloud layers. Wang et al. [130] proposed PPFLEC, a privacy-preserving FL scheme for IoMT under edge computing that used secret sharing with weight masks to protect gradients, a digital signature to ensure message integrity, and periodic local training to reduce communication overhead and accelerate convergence. Likewise, Stephanie et al. [131] designed a blockchain-supported ensemble FL framework that employed secure multi-party computation for privacy, FedAVG and weighted ensemble methods for aggregating heterogeneous models, and blockchain to guarantee data integrity, auditability, and version control.

- Secure Communication Protocols protect data exchanged between devices by ensuring confidentiality, integrity, and authenticity during transmission. To this end, Winderickx et al. [132] proposed HeComm, a fog-enabled architecture, which ensures end-to-end secure communication across heterogeneous IoT networks by establishing secret keys with the HeComm protocol and applying object security at the application layer. Swamy et al. [133] proposed Secure Vision, a layered Wireless Sensor Network (WSN) architecture that combines secure MAC and routing protocols, Transport Layer Security/Transport Layer Security (TLS/DTLS)-based transport security, and image processing techniques such as steganography and watermarking to ensure end-to-end confidentiality, integrity, and resilience.

4.2.4. Data Imbalance and Sparsity

Sensing coverage in cities is rarely uniform. Some regions, such as downtown or high-traffic zones, are saturated with redundant data from numerous sensors, while other areas suffer from sparse or unreliable coverage due to infrastructure gaps. This imbalance complicates the development of robust AI models, which must learn to operate effectively across both dense and sparse data environments. Techniques such as adaptive sampling, synthetic data generation, and cross-region model transfer are needed to mitigate these disparities. Uneven sensing coverage can be alleviated with adaptive and data-augmentation methods.

- Adaptive Sensing enables edge devices to adjust their sensing frequency, resolution, or modality in real time based on environmental conditions or workload demands, allowing them to conserve energy while maintaining data quality. Machidon et al. [134] proposed an adaptive compressive sensing–DL pipeline which dynamically adjusts sampling rates with a learned measurement matrix and entropy-based tuning. It preserved model accuracy while reducing sensor sampling and battery usage by up to 46%. Wang et al. [135] proposed a UAV-based lightweight detection algorithm, which can improve small-target recognition by adding MODConv to the detection head and using LSKAttention to adjust the sensing field adaptively. Combined with Soft-NMS, this adaptive design reduces missed detections while maintaining efficiency with FPW, thereby lowering computational cost. Likewise, Ghosh et al. [136] proposed an adaptive sensing framework for IoT nodes that combines Q-learning and LSTM to optimize energy use while maintaining sensing accuracy. Q-learning dynamically selected an optimal subset of sensors based on cross-correlation and energy constraints, while LSTM predicted missing parameters from sampled data.

- Data Augmentation expands training datasets by applying transformations to existing samples. Generative models such as GANs, Diffusion models can be used to synthesize missing sensor signals or enrich sparse datasets. For instance, Li et al. [137] proposed WixUp, a generic data augmentation framework for wireless human tracking that used Gaussian mixture-based and probability-based transformations to augment diverse wireless data formats and supports unsupervised domain adaptation through self-training. Orozco et al. [138] designed FedTPS, an FL framework for traffic flow prediction that augmented each client’s dataset with synthetic traffic data generated by a diffusion model built on a UNet backbone, trained collaboratively across silos. Pal et al. [139] proposed an ensemble data augmentation model for cardiac arrhythmia detection that combined borderline undersampling of majority classes with chaos-based oversampling of minority classes to balance ECG datasets.

- Cross-region Transfer Learning applies knowledge from a data-rich source region to a data-scarce target region to improve model performance. It is beneficial for tasks where data collection is expensive, complex, or geographically limited, as it addresses distribution shifts across regions. For instance, Guo et al. [140] proposed C3DA, a universal domain adaptation method for remote sensing by combining a two-stage attention mechanism with the C3 criterion (certainty, confidence, consistency) to filter out outliers and unknown classes, improving scene classification accuracy across diverse geographic regions. Zhang et al. [141] introduced Target-Skewed Joint Training (TSJT), a one-stage transfer learning framework for cross-city spatiotemporal forecasting. The framework combined a Target-Skewed Backward (TSB) strategy, which selectively refines gradients from source-city data to benefit the target city, with a Node Prompting Module (NPM) that encoded shared spatiotemporal patterns. Likewise, Zhao et al. [142] proposed an adaptive remote sensing scene recognition network to mitigate domain shift across sensors. Their approach learned sensor-invariant representations adversarially, aligned class-conditional distributions contrastively, and transferred semantic relationship knowledge to improve cross-scene recognition.

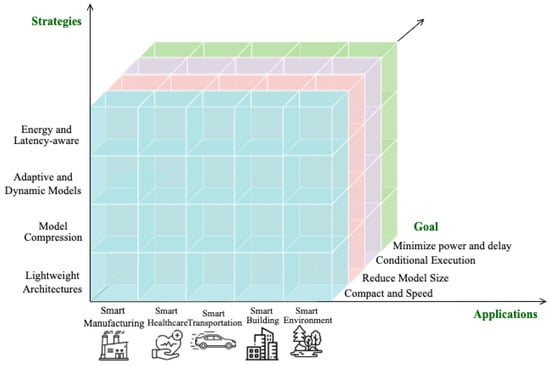

5. Edge AI Learning Models for Smart Cities

In this section, we discuss four key strategies for enabling efficient model deployment in edge AI for smart cities, spanning lightweight architectures, model compression, adaptive and dynamic models, and energy- and latency-aware model optimizations. Figure 7 provides a high-level view of this section illustrating how different strategies are used to achieve goals aligned with sub-domains.

Figure 7.

Learning Models in Edge AI for Smart Cities.

5.1. Model Design and Optimization Strategies for Edge AI in Smart Cities

Table 8 outlines four key strategies for enabling efficient model deployment in edge AI for smart cities. For example, lightweight architectures are designed from scratch for compactness and speed, making them suitable for latency-sensitive services like traffic monitoring, though often at the cost of reduced accuracy. Model compression techniques such as quantization, pruning, and knowledge distillation, shrink large models while maintaining most of their accuracy, which is useful in domains like healthcare or safety analytics but may still strain very limited devices. Adaptive and dynamic models allow flexible computation through conditional execution, making them effective for fluctuating workloads such as adaptive traffic control, albeit with added complexity in stability and calibration. Finally, energy- and latency-aware optimization explicitly co-designs models with hardware to minimize power consumption and delay, as in energy-aware or latency-optimized models, which are crucial for long-term sustainability in sensor-rich or wearable applications. Together, these strategies provide complementary solutions for balancing accuracy, efficiency, flexibility, and scalability in smart city AI services. In what follows, we explain each strategy in detail.

Table 8.

Different Model Design and Optimization Strategies for Edge AI in Smart Cities.

5.2. Lightweight Model Architectures

Compact CNNs are smaller, more efficient versions of CNNs designed for resource-constrained devices like microcontrollers and FPGAs. These models are increasingly applied in smart city domains, including healthcare, surveillance, and people counting, where efficiency, low memory usage, and fast inference are critical. In healthcare, Wong et al. [143] proposed a low-complexity binarized 2D-CNN classifier on FPGA-based edge platforms. The design combined a quantized multilayer perceptron (qMLP) for ECG-to-binary image conversion with a binary CNN (bCNN) for classification, reduced multiply–accumulate operations, and achieved 5.8× reduction compared to conventional CNNs. Aarotale et al. [144] introduced PatchBMI-Net, a lightweight facial patch-based ensemble model for body mass index (BMI) prediction on mobile devices. The model processed six facial regions independently with compact CNNs and averaged their outputs, yielding a 5.4× reduction in size and a 3× improvement in inference compared to heavy-weight CNN baselines. Peng et al. [145] developed a lightweight CNN-based cough detection system for FPGA edge deployment. The design used depth-wise separable convolutions and grouped point-wise convolutions, which are inspired by ShuffleNet, together with channel shuffle operations to improve efficiency. In video surveillance, Khan et al. [146] proposed LCDnet, a lightweight crowd density estimation model that integrated a compact CNN architecture with curriculum learning for improved ground-truth generation. The design produced density maps that preserved spatial details while maintaining low computational cost, memory usage, and inference time, making it suitable for drone-based surveillance. For counting the number of people in indoor spaces, Yen et al. [147] developed an adaptive system on a Raspberry Pi 4 equipped with fisheye lens. The system employed a lightweight YOLOv4-tiny model with spatial pyramid pooling (SPP), spatial attention mechanism (SAM), and depthwise separable convolutions to enhance accuracy while reducing computational costs.

Tiny Transformers are smaller, efficient versions of Vision Transformers (ViTs), whereas hybrid CNN–Transformer models integrate the local feature extraction of CNNs with the long-range dependency modeling of Transformers. Together, these approaches balance the global context modeling capability of Transformers with the need for lightweight architectures for resource-constrained devices. In vision tasks, Wu et al. [148] introduced the Progressive Shift Ladder Transformer (PSLT), a lightweight ViT backbone. The design included ladder self-attention blocks that feature multiple branches and a progressive shifting mechanism. In this design, each branch processed a subset of the input channels, reducing the number of parameters and floating-point operations (FLOPs) while preserving the ability to capture long-range interactions. The outputs from all branches are combined using a pixel-adaptive fusion module. In environmental monitoring, Annane et al. [149] proposed a CNN–Transformer hybrid model with blockchain integration for forest fire prediction using drone-captured images. The CNN extracted spatial features; meanwhile, the Transformer captured temporal features such as smoke visibility, fire intensity, and fire direction. These features are fused to predict fire spread and extent, with secure data storage and communication ensured through blockchain. In smart home applications, Ye et al. [150] proposed Galaxy, a collaborative edge-AI system designed to accelerate Transformer inference for voice assistants. The system introduced a hybrid model parallelism to orchestrate inference across heterogeneous edge devices, a workload-planning algorithm to maximize resource utilization, and a tile-based scheme to overlap computation and communication under bandwidth constraints. Evaluations showed that Galaxy reduced end-to-end latency by up to 2.5× across multiple edge environments. In speech processing, Wahab et al. [151] proposed a lightweight encoder-decoder architecture for real-time speech enhancement on edge devices. The encoder employed adaptive, frequency-aware gated convolution to emphasize speech-relevant features. At the same time, the Ginformer-based bottleneck applied low-rank projections and Simple Recurrent Unit (SRU)-based temporal gating to reduce complexity and capture long-range dependencies.

Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) are DL models, which are designed to process graph-structured data, where nodes represent entities and edges represent their connections [152]. By iteratively aggregating information from neighbor nodes, GNNs generate richer node representations to support tasks such as classification, prediction, and detection. In vehicular edge networks, Huang et al. [153] proposed a task migration strategy using a dual-layer GNN. The vehicle-layer GNN predicted vehicular trajectories, while the RSU-layer GNN forecasted resource availability. Their outputs are combined through a task-based maximum flow algorithm (T-MFA) to guide task migration and resource allocation. For vehicular routing, Daruvuri et al. [154] introduced a data packet routing protocol within a three-layer terminal–edge–cloud architecture. GNNs are employed to capture traffic patterns and multi-hop connectivity, while Transformer-based Reinforcement Learning (TRL) adapts routing strategies through interactions with the IoV environment. In rail transit applications, Huang et al. [155] presented Rail-RadarGNN, a radar-only obstacle detection method that embedded radar points into a high-dimensional feature space. The model integrated auto-registration and graph attention mechanisms for feature extraction, while the GAEC module enhanced feature alignment and the MPNN-R module preserved feature integrity to support deeper training.

Automated Machine Learning (AutoML) streamlines model development via automating tasks like feature engineering, model selection, and hyperparameter tuning, which allows faster adaptation in resource-constrained environments. Neural architecture search (NAS) complements AutoML by discovering lightweight yet high-performing neural architectures. These approaches optimize models not only for accuracy but also for the limited compute, memory, and energy budgets of edge devices. For instance, Mitra et al. [156] proposed EVE, an AutoML co-exploration framework for energy-harvesting IoT devices. EVE employed an RNN-based RL controller to search for shared-weight compressed models with varying sparsity, pruning types, and patterns, allowing adaptation to changing energy levels. Similarly, Cereda et al. [157] applied NAS with pruning-in-time (PIT) to optimize CNNs for visual pose estimation on nano-UAVs. Using PULP-Frontnet and MobileNetv1 as seed models, the mask-based DNAS tool generated smaller, more efficient networks while maintaining accuracy. The resulting CNNs, deployed on the Bitcraze Crazyflie 2.1 drone, were up to 5.6× smaller and 1.5× faster than baseline models.

5.3. Model Compression

Model quantization converts a neural network’s parameters (weights and activations) from a higher-precision format (e.g., 32-bit floating-point numbers) to a lower-precision format (e.g., 8-bit integers) to reduce the model size and accelerate inference. This lowers memory usage, storage requirements, and computational costs, enabling efficient deployment on resource-constrained devices. For example, Wong et al. [143] proposed a binarized 2D-CNN classifier for wearables on FPGA fabric. The design integrated a quantized multilayer perceptron (qMLP) that converts ECG signals into binary images using 8-bit weights and a quantized ReLU, followed by a binary CNN (bCNN) that classifies them with binary activations and XNOR operations. This quantization reduced multiply–accumulate operations by 5.8× compared to existing wearable CNNs while maintaining 98.5% accuracy. Similarly, Li et al. [158] proposed a quantization algorithm for CNN-based human foot detection to support inductive electric tailgate systems. The model applied linear asymmetric quantization, converting 32-bit floating-point weights into 8-bit fixed-point values, reducing memory use by 4× and enabling efficient edge deployment. Yang et al. [159] studied quantization and acceleration of the YOLOv5 vehicle detection model on an NVIDIA Tesla T4 GPU. After training, the model was quantized and accelerated using TensorRT, which mapped floating-point activations and weights to 8-bit fixed-point values through calibration, achieving up to 4× faster inference than floating-point operations. Shah et al. [160] introduced OwlsEye, a real-time low-light video instance segmentation system implemented on the Intel Nezha Embedded platform with YOLOv8-Nano-Segmentation. With the EQyTorch framework for fixed-posit quantization, along with brightness verification and asynchronous FIFO pipelining, throughput improved from 0.6 FPS to 28 FPS, with latency and power efficiency gains of up to 9.02× and 87.91× compared to INT8 and FP32. Furthermore, Han et al. [161] designed a lightweight real-time vehicle detection system for edge devices using pruning, quantization, and knowledge distillation. In this system, quantization converted floating-point weights into low-bit integers. As a result, latency decreased from 45 ms to 32–35 ms, and memory usage dropped from 120 MB to 32 MB.