1. Introduction

Over the past decade, the European economy has gradually slowed, losing much of its global competitiveness and falling significantly behind countries such as the US, China, South Korea, Japan, and Taiwan. In recent years, we have witnessed a technological catch-up in the field of key innovations (fundamental scientific discoveries) introduced in the US over the previous decade, such as e-commerce and online retail, with the primary goal of reaching as many customers as possible. In the era of Artificial Intelligence and the boom in quantum processor development, the digital sector is driving growth, creating fundamentally new types of jobs, and generating significant positive side effects across all technology sectors. From personal computers, the internet, digital platforms, 4G/5G, the Internet of Things, smartphones, and cloud services to artificial intelligence (AI), the most significant technological breakthroughs of the last few decades have been dominated by the ICT sector. In the new conditions, the development of regions and individual countries is based on a new type of economy grounded in information, knowledge, and new technologies, whose advancement is influenced by the degree of its successful implementation in the management of economic, managerial, social, and administrative processes. Therefore, we can find a direct link between the development of the ICT sector, the generation and accumulation of know-how, the diffusion of knowledge and new technologies, investments in research and development, manufacturing, and all other factors that underpin economic growth in individual countries and regions.

ICT has been the most innovative area of technological development over the past few decades. It is therefore a key dual factor—both endogenous and exogenous—for regional development, and should be a priority in management programmes and policies. The functions of generative AI create opportunities for accelerating innovation in other sectors.

Since the advent of computers and microprocessors in the mid-1970s, computers have been used in the planning and management of processes, including urban and regional development, over the last decade. Initially in the form of GIS systems for cartography, then for implementing information systems in databases on population, levels of education and healthcare, macroeconomic indicators and indices, and today in the form of artificial intelligence (AI) [

1,

2]. Theories and ideas about the existence of artificial intelligence date back only to the end of World War II, often as secret military experiments aimed at technological superiority over other countries during the Cold War era at the end of the last century.

Since then, the growth rate of IT services’ added value has been almost twice that of the global economy, surpassing all other sectors over the last two decades, according to the Trade in Value Added (TiVA) dataset. Lower-income groups also benefit disproportionately from these digital services [

3]. Value added in ICT development and manufacturing, and in ICT services development, is highly concentrated in high-income economies, with concentration increasing even further over the past decade, in half the time. China and the United States account for more than half of the world’s value added in both industries. In addition, the six largest economies account for 80% of global value added in ICT manufacturing and 70% in ICT services. Since 2010, these shares have increased even further, as economies of scale and scope, network effects, and the characteristics of the ICT sector have reinforced the dominance of the world’s leading economies. Between 2000 and 2020, the intensity of IT services in the financial sector (fintech) increased only slightly in low- and middle-income countries. In contrast, in most high-income countries, it doubled and is now a significant part of lending and payment services.

The development of new information and communication technologies is transforming the global and regional socio-economic environment. The rapid development of artificial intelligence is greatly amplifying these changes. Its role is becoming increasingly key as it transforms the economic system and its nature. We are therefore witnessing a new technological revolution that will propel the economy into a new evolutionary stage of its development. In this sense, such a change requires a specific interdisciplinary approach to research and measurement. One possible theoretical framework for explaining this profound economic change is classical political economy [

4]. Given the profound transformations, the question of environmental and social justice in the context of economic transition arises. In this vein, it is essential to articulate the link between artificial intelligence and sustainable regional development [

5]. Given the specifics and interconnectedness of artificial intelligence with innovative development, innovation, education, and other factors, the impact of artificial intelligence can be analyzed and assessed through the formation of regional innovation systems, which are the modern drivers of progress. For example, an evaluation of the impact of Artificial Intelligence (AI) on regional policy through a political economy framework shows that AI can both drive economic efficiency and exacerbate existing inequalities, with its ultimate effect heavily dependent on governance, policy choices, and existing regional structures [

6]. In classical political economy, the development of artificial intelligence and its impact at the regional level are linked to changes in political power, labor-market management, and the adoption of adequate rules and a regulatory framework that ensure a competitive environment and overcome regional differences [

5,

7]. The economic transition that regions and the world are undergoing must be understood through the concept of sustainable development. On the one hand, artificial intelligence’s influence on regional development needs to be guided by the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals [

8]. At the same time, sustainable development becomes more applicable and realistic through the use of artificial intelligence, which supports more rational resource use, precision agriculture, healthcare, water management, urban planning, energy efficiency, transport, and education. All this has significant economic effects on individual regions. Therefore, AI is a powerful enabler for achieving the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) [

8]. It offers innovative solutions in key areas of sustainable development. By processing massive datasets and identifying patterns, AI can dramatically increase efficiency, reduce waste, and enhance monitoring efforts, though its implementation requires careful ethical governance to mitigate risks [

9].

On the other hand, artificial intelligence is changing regional policy. It provides management with more opportunities through analysis, monitoring, forecasting, and modeling. Artificial intelligence offers more opportunities but also carries many risks and challenges, requiring management to learn and adapt to change continually [

10].

Based on regional sciences, all processes find their natural place within individual territories. In this sense, regional policy creates the conditions for the development of particular regions, including in the context of innovative development. This is the next evolutionary stage of sustainable regional development of territories. This development is based on innovation and regional innovation policy. Therefore, regional policy and the regional innovation system are interrelated and interdependent. In recent years, the development of artificial intelligence has begun. This process is highly dynamic but directly linked to the formation and strengthening of regional innovation systems.

The connection between AI and Regional Innovation Systems (RIS) is increasingly significant, as AI acts as both a driver and an enabler of innovation dynamics within regions. AI technology stimulates regional economic development and innovation capacity, and integrating AI indicators into RIS measurement provides insights into how AI adoption and innovation ecosystems interact and evolve.

The points of contact and interrelationships between AI and RIS can be viewed in different ways. For example, AI fosters regional innovation by reshaping industrial structures, improving production processes, and creating new business models and industries. On the other hand, AI-driven innovation enhances regional economic collaborative innovation, improving productivity and sustainable growth. It should be emphasized that developing AI ecosystems within regions requires coordinated efforts in talent development, finance, infrastructure, and policy support. AI accelerates digital transformation and boosts innovation activities in firms, universities, and public organizations, often measured within RIS frameworks. In this sense, the RIS assessment includes sub-indices for innovation opportunities (human potential, informatization level), innovation activity (patent applications, research quality), and effects (economic returns on innovation activities, including AI-specific contributions). On the other hand, AI indicators can be integrated into these sub-indices to reflect the innovativeness and technological dynamism supported by AI within a region.

This integration of AI indicators into RIS measurement frameworks helps capture how AI affects regional innovation capabilities and provides guidance for policy to foster AI-driven regional growth.

Artificial Intelligence (AI) connects with Regional Innovation Systems (RIS) by acting as a key driver and enabler of innovation within regions, influencing economic growth, productivity, and technological transformation. AI fosters industry restructuring, enhances collaboration among firms and institutions, and introduces new products and processes, which are central concerns of RIS.

Contemporary research lacks sufficient studies and analyses of the relationship between regional innovation systems, the application of artificial intelligence, regional policy, and regional development. The explanations for this are related to the highly dynamic nature of developments in artificial intelligence, which does not allow for the development of an evaluation framework. Furthermore, these processes have been developing in recent years, which limits the collection and analysis of data, especially at the regional and municipal levels.

At the same time, AI promotes regional economic development by enhancing innovation capacity and efficiency. Consequently, AI-driven innovations transform traditional industries and create new market opportunities within regions. From this perspective, AI adoption accelerates digital transformation and collaborative innovation among regional actors, including universities, firms, and governments. That is why the development of AI ecosystems in RIS requires talent cultivation, infrastructure, finance, and coordinated policy. Based on these arguments, the authors analyze the impact of artificial intelligence on regional development through the prism of regional innovation system formation. That is why the authors believe that artificial intelligence applied at the regional and municipal levels is part of the toolkit of modern regional policy.

2. Analysis and Systematization of the Theory Framework

In the scientific literature, the role of AI in spatial planning has received little research attention, except for Zaborovskaia and Toffler, who focused solely on the economic level to stimulate innovation. This role is used much more extensively in urban planning to establish economic centers [

11,

12]. In regional geography, the issue of spatial organisation through AI remains under-researched because of the lack of regional and field studies that reveal its impact on the planning and management of territorial systems at different scales. Many authors argue that a knowledge-based system is based on the assumptions that:

The problem can be clearly defined and well-delimited by setting the parameters of an algorithm;

The relationships between the factors or elements of the problem are known and can be explicitly expressed by setting variables in the algorithm.

Methods for solving problems can be formulated, and

experts agree on the solutions, i.e., the cause-and-effect relationships are clearly defined [

13].

In the concept of semantic networks, Sowa links reasoning to pattern finding, while Davis et al. examine “What is knowledge representation?” from a somewhat abstract, often philosophical point of view, based on five different roles: (i) a substitute or replacement for the thing itself (intelligence-artificial intelligence), (ii) a set of ontological commitments, (iii) a fragmentary theory of intelligent reasoning (algorithms), (iv) a means of pragmatically practical computation and (algorithm optimization) (v) a means of human expression, i.e., a language in which we say things about the world (programming realities) [

14,

15,

16].

Despite the rapid development of AI and the expansion of its practical applications, scientific publications and research on the technology’s impact lag behind the generative, super-new value of localization solutions for complex planning and modeling tasks related to regional development. In this vein, geography and economic theories are in dire need of transformation and adaptation to the new realities in which, according to Schumpeter, the end of the old paradigm is near, and its foundations need to be reformed or completely redefined [

17]. During the era of Kondratiev’s sixth “L” wave in economics, AI requires the development of new research methods and methodologies to analyze large databases for accurate forecasting [

18]. The fields of application of these methods will become increasingly widespread in modeling and programming for the development of spatial systems. They are capable of challenging the pure theories of Schandort from the beginning of the 20th century and fundamental economic laws. This article will examine three critical dimensions of the development and application of AI for regional policy: knowledge management and diffusion between regions, policy argumentation, and machine learning.

AI has a significant role in regional policy and urban planning. Creating opportunities for studies and research on the applications of AI in smart cities, urban analysis, and decision-making systems in regional management.

The economic changes associated with the development of artificial intelligence are closely linked to regional processes. These processes essentially represent a new type of regionalization and a change in the institutional order, including the participants in political and managerial decision-making. In this regard, the new regionalism is equivalent to a new type of urbanism based on the principles of social and environmental justice [

7,

8]. New urbanism should be viewed in a broader context, namely, the evolution of strategic planning to achieve better urban design and development.

The new regionalism is associated with political and administrative fragmentation [

7,

19]. This approach can also be seen in the EU, where the concept of a “Europe of regions” plays a key role in its development. This approach is based on the main political objective of bringing regions closer together. In this sense, empowering areas is key to implementing regional policy. Within the framework of regional and local policies, not only is the hierarchical principle important, but horizontal relations are also important, which assume an institutional character in decision-making. Linking the development of artificial intelligence to this change in the institutional mechanism of political power broadly imposes a normative and regulatory approach to regional development and its management. The explanation is related to the need to guide the new type of regional economy, including through regional management.

The new regional economy can be explained using the tools of classical political economy [

5]. One explanation is that artificial intelligence is changing the national and regional environment, transforming capital and directly linking regions’ innovative capabilities through the prism of regional innovation systems. At the same time, there is a qualitative change in human capital through the education system and the acquisition of new knowledge and skills, including those influenced by artificial intelligence. In this sense, labor is also changing its form and geography. As regional differences in the spread of artificial intelligence become more pronounced, these differences are becoming more pronounced [

20]. That is why regional policy essentially aims at convergence, but with the use of artificial intelligence, the environmental and social consequences can be mitigated.

In this regard, the new strategic planning closely incorporates the principles and goals of sustainable development [

21]. The changed institutional mechanism governs these strategies. The latest economic landscape, strongly influenced by the dynamics of artificial intelligence development, must be guided towards achieving regional sustainable development. Regional sustainable development is characterized by its specificities, as each region differs from the others. In addition, regions differ in their political and institutional traditions. What they have in common is regional strategic planning aimed at regional sustainable development. Therefore, it can be based on a common European regulatory framework and monitoring criteria [

7,

22]. There are various models for analyzing regional sustainable development. We want to focus on an interesting model that combines regional growth with sustainable development. The model measures sustainable cities in Bulgaria [

23]. In general, it includes several phases: formulating key indicators for sustainable urban development policy; collecting and modeling data; conducting spatial analysis and visualization; applying the model to assess sustainable urban development; and visualizing and interpreting the results.

A literature review conducted at the beginning of the study reveals several obstacles to AI application, including a lack of statistical data at lower territorial levels (provinces, municipalities, urban areas) and other constraints on the development of digital infrastructure. Regional differences and imbalances in readiness for AI implementation and application.

Review of studies and research related to theories of innovation diffusion and how central locations (e.g., innovation centers and hubs) stimulate regional technology adoption and spatial diffusion. The basis for these concepts draws on the work of Feldman, Asheim, and Gertler on the geography of innovation [

24,

25]. All are directly related to the pure theories of Christaller, the localization theories of Haggett, Chorley, Harvey, and Krugman, and to Fujita’s work on the dispersion of growth factors across territorial units of different sizes [

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31]. The achievements of Krugman, Myrdal, and Kaldor are fundamental and considered cornerstones of a theoretical framework for the study (

Table 1).

The digital era of intangible knowledge began at the end of the 20th century, a period marked by a complex, dynamic prism of time, in which time and space are perceived as significant for socio-economic geography processes with a territorial dimension. Undoubtedly, the intangible assets associated with AI manifest in the same two variables, which reveal the dynamics of social relations. According to Bauman, these relations are characterized by polyvalence, mobility, and diversity [

34]. Diversity naturally fosters competition and contributes to processes such as globalization, digitization, and regionalization. The levels of difference and synergy between the constituent elements of the systems have a multidirectional impact on the cyberspace of quantum computers and generative artificial intelligence. Consequently, they also change the conditions in the environment in which AI develops and influence properties that are often defined, such as self-programming and directly on the “self-organization” property of systems.

Interest in the topic is mainly driven by Castells and Toffler’s concepts of network societies and Polanyi and Granovetter’s concept of establishing knowledge through investment in specific locations with specific environmental conditions [

12,

35,

36,

37]. The aforementioned factors of localized knowledge, transformed into intangible assets and innovations, act simultaneously as exogenous and endogenous factors for the development of the territory. In addition, Westlake and Haskell reveal the symptoms of the growing circular influence of the intangible asset AI on the global future [

38]. According to them, social integration is achieved through the power of connections to transfer information and knowledge, which impacts the region’s development. Therefore, intangible assets and knowledge in the form of databases directly impact regionality, territorial differences, and localization. As a result, the establishment of II fits into the theoretical conceptual essence of regional geography, creating conditions for defining new localization theories in relation to the development of technologies and know-how. New interpretations in socio-economic geography are linked to the new category of “intangible assets (resources)” derived from localized knowledge, as well as to the factors that determine their development (research centers, scientific laboratories, co-working spaces, innovation parks, ICT centers, etc.).

Today, regional geographical research must increasingly focus on seeking scientific explanations for the dynamics of processes such as intangible capitalism, artificial intelligence, the circular economy, decentralization, factor mobility, the informal economy, social networks, the Internet of Things, machine learning, and deep learning. The global accumulation of localized knowledge, military, capital, or innovation potential is fundamental to the development of the world. Therefore, competition among leading countries focuses on accumulating new knowledge to gain a competitive advantage.

The progress and dispersion of artificial intelligence create incentives for policymakers in developed countries to explore the potential of technology to improve regional and urban planning by reducing socioeconomic disparities, addressing infrastructure challenges related to localization decisions, and improving the distribution of various resources. AI functions for processing geospatial databases. Distributive data processed by algorithms enhances the accuracy of forecasting and localization analysis, thereby optimizing decisions, policies, and measures. Therefore, AI calculations can serve as tools for spatial organization and the optimization of regional development by creating new management models.

Despite process optimization, the new functionalities of AI applications in regional policy are accompanied by several obstacles—from technological limitations to ethical considerations and privacy and individual rights concerns. This study reveals the geographical distribution within the EU compared to the US and China, the technological barriers and potential solutions that AI can offer, and the role of AI in promoting and implementing sustainable regional policy.

The models generated by AI represent a self-programming representation of reality. The study of the dynamics in this reality reveals the spatial dimensions of real processes and phenomena during self-organisation, according to the evolutionary theory method in geography [

28]. In this context, spatial models generated by AI can play a key role in clarifying several important localization and urban planning issues related to the development of regional development management policies. These models should seek answers and strive to identify patterns regarding the localization of economic activities, the distribution and dynamics of the population, the size and distribution of cities, and other issues with a spatial dimension, providing answers to the following questions: “Why, Where, and How?” [

39,

40].

According to Rifkin, in a “wired world,” geography is more important than ever. In geography today, little is said about intangible assets, AI, and their impact on the organization of space [

41]. The regional dimensions of the degree of influence of these factors are critical because they alert us to the problems of future development. The growing importance of intangible capital generated by AI through accumulated knowledge serves as a hypothesis that companies (enterprises) that operate only in a specific territory (location) have fundamental strategic disadvantages and lower levels of competitive advantage, such as companies in Bulgaria and countries with a similar economic profile to developing countries with economies in transition [

42].

In the context of intangible assets and the diffusion of innovation, a region can be defined as smart, the result of the evolution of a learning region that acquires know-how and technologies and gradually becomes one that generates innovation and technology. A smart region can be defined as a spatial unit entirely covered by a digitized layer of data and information on the state of various natural, social, and economic components. Their qualitative and quantitative status is primarily used to plan cities according to their functions and to implement regional policy to manage and organize regional development. In the specified digital layer, various distributed GIS data on natural elements and large databases related to economic growth are available. This type of data can be visualized as a 3D model, combined with the Internet of Things and other blockchain technologies, and, through artificial intelligence, various solutions can be defined in the argumentation for political decisions relevant to the development and management of a specific territory. Therefore, it is necessary to provide several examples of urban planning initiatives that can synergize with regional-level components.

Batty links several studies on the role of AI in the theory of innovative city management in his research. Other authors, such as Bisen, examine the role and impact of video surveillance applications as tools for law enforcement agencies to monitor compliance with public order [

43,

44,

45]. Such digital systems can be used to organize car parking and manage traffic. In another aspect, collecting data on the ecological footprint of equivalent residents can serve as a tool for developing a waste management, disposal, and recycling system. According to Kumar, AI-driven technologies have various uses in smart cities, from maintaining a healthy environment to improving public transport and safety [

46]. He adds that, using artificial intelligence algorithms and machine learning, the city can implement a more targeted urban planning policy through intelligent traffic management solutions that ensure residents get from one point to another as safely and efficiently as possible.

In a geographical and regional context, Thakker et al. apply AI to monitor flooding by screening ravines and watersheds associated with surface runoff distribution and drainage in key flood-prone areas [

47]. The use of such digital models in the development and implementation of policies addressing the impacts of climate change and its consequences is essential to any decision to monitor floods, fires, droughts, and extreme weather events. Recently, Gao introduced the concept of “geospatial artificial intelligence (GeoAI)”, which regroups all attempts to use AI not only in GIS but also in urban and regional planning, by developing various models that define regional policy priorities [

48].

Sustainable innovations such as AI require significant financial resources and substantial capital expenditures for operations. There is a variety of AI-based business models that include supply (e.g., eco-technologies) on the one hand and demand (e.g., new needs and new forms of consumption in a given region) on the other. Sustainable innovations are distinguished into four “dimensions”: product-oriented, institution-oriented, flagship, and territory-oriented. These dimensions differ not only in territorial scope but also in innovation profile, with a focus on sustainability, purpose, participants, and coordination mode. This framework has been used to classify cases in research tasks, but it appears somewhat ad hoc and lacks a more consistent theoretical foundation. For example, the “flagship-oriented” innovation dimension may have been included to integrate such cases, rather than because flagship orientation is a necessary dimension of sustainable innovation, which covers an extensive and diverse range of topics. From AI-based models for photovoltaics and sustainable finance in Switzerland, green technology construction KIBS in Germany and China, urban renewal and reconstruction projects in Lisbon and Île-de-France, to sustainable tourism in Alpine regions, (inter)regional networks in Rome and the Atlantic region of France, innovative urban operating systems in northern Portugal, a water campus focused on sustainable water technologies in the Netherlands, to changes in regional production systems in the Basque Country and Japan. All of them share certain aspects of sustainability and include studies of specific local industries, with a multi-location or global perspective on AI modeling. These studies are widely applicable to territorial transformations and restructuring, as well as to “flagship projects” in the context of sustainable regional development. Some of them illustrate very well the new characteristics of innovative environments (millio), namely: the global-local “anchoring” of resources and innovations, the symbolic dimension and demonstrative nature of innovations, the wide variety of participants, which goes beyond the traditional “triple helix” of companies, knowledge organizations, and policymakers to include consumers, the media, civil society, NGOs, etc.

Most of the cases cited are interesting, but they are not unified within a common theoretical-scientific framework because they are highly diverse in topics, concepts, and methodologies. Furthermore, they relate differently to the framework and issues raised in the introduction, with some being more closely related to others. Roberto Camani provides an excellent overview of the development of the GREMI approach, including ideas for a new ecological perspective grounded in emerging technologies and innovations. We also find this broader understanding in the concepts of user-driven innovation, collective learning, innovation regimes, and different types of knowledge bases, including analytical, synthetic, and symbolic, all of which are elements of the AI system [

49,

50,

51,

52].

All of the above-described processes and trends related to economic change and the development of artificial intelligence occur in space. Therefore, given the new regionalism, it is necessary to measure the impact of artificial intelligence on regional development and the fundamental changes in countries’ regional policies. Within regions, political decisions are determined by a range of participants in the process, including official national and regional authorities, local communities, civil society organizations, businesses and their industry associations, universities, and others. In this regard, regional policy aims to create conditions for regional sustainable development, with the participation of all listed stakeholders. In this sense, the authors need to design the interaction between the development of artificial intelligence at the regional level and the regional policies applied, to promote regional sustainable development. The common denominator in this case is innovative development, innovation, and education, which are the drivers of growth in the regions. That is why the authors believe that the most appropriate theoretical framework and methodological toolkit is regional innovation systems. Artificial intelligence (AI) is transforming traditional regional innovation systems (RISs) as a general-purpose technology (GPT) that enhances productivity and decision-making, while also posing significant challenges for regional policy and development, including job displacement and the digital divide [

53,

54].

Regional innovation theory emphasizes the importance of localized interactions among firms, universities, research institutions, and government in fostering innovation and economic growth within a specific geographic area [

55]. Key characteristics include: localized learning, institutional Infrastructure, and spatial proximity [

56].

AI is profoundly reshaping these dynamics and necessitates adaptive regional policies to maximize benefits and mitigate risks. These challenges are related to the transformation of the regional innovation system (knowledge empowerment, optimized resource allocation, new collaboration models, and democratization of innovation) [

57].

AI breaks traditional spatial and temporal constraints on knowledge sharing, enabling intelligent acquisition, dissemination, and creation of knowledge through large datasets and machine learning, benefiting regions regardless of proximity. On the other hand, AI helps optimize supply chains, energy use, and public services through predictive analytics, particularly benefiting rural areas or those with infrastructure challenges. Innovation is shifting from linear value chains to networked collaboration, requiring new governance models and platforms that integrate diverse stakeholders (governments, enterprises, etc.) across a region. AI tools lower traditional barriers to entry, enabling innovators from a broader range of socio-economic backgrounds and regions to contribute, thus diversifying the global innovation landscape [

58].

3. Materials and Methods

In the context of economic geography, the impact of AI is often distinguished by concepts such as data, information, knowledge, and wisdom [

59]. In this type of regional research, knowledge can be defined as an intangible asset in the form of information. This knowledge helps solve a given problem—here, the rapid expansion of AI—while wisdom helps make sensible use of accumulated knowledge and know-how to advance society’s scientific and technological progress.

Mirdal and Kaldor define the conceptual and empirical foundations for understanding regional differences as cumulative and self-reinforcing. Krugman transforms these ideas into spatial economic models that explain why economic activity is concentrated in “clusters” and why differences persist despite market integration in the case under study. Instead of reducing differences, the expansion of AI deepens them because regional innovation systems are underdeveloped and dysfunctional.

To clarify the structure of such regional systems, it is essential to apply the DIKW (Data, Information, Knowledge, Wisdom) pyramid, a key concept in computer science and AI. For this reason, it is included in the instrumental part of the analysis.

When researching the impact of AI on economic and geographical factors, we reveal the differences among the concepts of data, information, knowledge, and wisdom [

59]. That is why knowledge is defined as an intangible asset in the form of information that helps solve a problem, and wisdom is the practical application of accumulated knowledge and know-how.

The main objective of the study is to analyze and assess the impact of AI on regional sustainable development and the possible changes in regional policy that incorporate AI tools.

The authors formulate several research hypotheses that they will test:

H1. The readiness to implement AI in the EU at the national and regional levels is low. This reduces the potential for increasing the competitiveness of European economies and regions.

H2. There is polarization in the EU in terms of technological development, the degree of innovation in the regions, and AI implementation.

H3. There is a direct link between innovation development, economic development, investment levels, and AI implementation.

H4. The EU’s regional and cohesion policy plays a key role in technological change based on the implementation of AI.

The main analytical steps of the study include: theoretical analysis and selection of the main theoretical framework of the study; on this basis, selection of appropriate research approaches and methods; for the application of specific research methods in a spatial context, the authors select appropriate indicators that reflect the interdisciplinary nature and link regional development with innovation and AI development; the next step is related to the spatial characteristics of the spread and implementation of AI in European countries and how this affects their economic growth and future potential; a composite index of AI readiness has been developed and applied, using correlation, regression analysis, and Pearson’s test. Finally, the study’s main results and conclusions, along with opportunities for further research, are presented.

Based on the literature review, the authors adopt the regional innovation system as their main theoretical framework. In this regard, the study requires an interdisciplinary and territorial approach given the nature of the research subject. Within the outlined theoretical framework and approaches, the authors apply a combination of methods, including descriptive, comparative, statistical (regression and correlation), cartographic, and an index of readiness for AI use in NUTS 2 regions.

The data used in the study were collected at NUTS 1 and 2 levels (EU countries and NUTS 2 regions). The following indicators were collected and analyzed: GDP, share of the population using the Internet, enterprises using AI, enterprises using AI in their economic activity, by type of activity, specialists with higher education, intramural R & D expenditure (proxy for patents/investment), R & D personnel (researchers), employment in high-tech sectors (proxy for AI companies/startups), business R & D (proxy for VC/business investment), R & D personnel as human capital, ICT sector share in GVA and high-tech employment as proxies for AI adoption and digital infrastructure. Due to the lack of information for all European countries, the authors analyze and evaluate the following countries: Malta, Germany, the Netherlands, Bulgaria, Latvia, Estonia, Hungary, Belgium, Lithuania, Denmark, Portugal, Spain, Greece, Romania, Cyprus, Finland, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, and Sweden. The countries that are not evaluated are: France, Norway, Lithuania, Slovakia, Poland, the Czech Republic, Austria, Slovenia, and Croatia.

The combination of these methods enables the study of general models based on location (locality) relevant to the application of AI to prove the hypotheses set out in the research tasks. The centroid method is used to identify the locations of regional innovation centers and their relationships to AI innovation and to the region’s factor conditions, which are fundamental to the spread of technology. This method identifies the central locations and reveals the economic factors that make certain areas more favorable for the implementation and use of AI than others [

32,

33]. The use of cartographic and statistical methods helps visualize and predict parameters for AI applications in the management of different regions. This allows for a comparative analysis of the readiness and degree of AI implementation in other areas of spatial planning and regional development according to the New Economic Geography [

30].

When conducting a comparative analysis of the application of AI to model regional development, traditional scientific methods in regional geography are used. With their help, we answer the questions posed in the introductory part of the scientific article. First, we clarify the application of AI to the development of societies and the Industrial Revolution, focusing on changes in labor productivity. In another aspect, improving the quality and education of the workforce in specific sectors also increases income and living standards in those regions. In other words, the marginal utility of such technologies is linked to the multiplier effect within the systematic approach to analyzing the impact of regional policy. Induction and deduction in this context help to study general patterns in the application of AI and specific private cases to verify the validity of the hypotheses set out in the research tasks.

The centripetal method identifies the location of regional innovation centers relative to a region’s factor conditions for technology dissemination. This method for determining central locations focuses on the geographical and economic factors that make certain areas more favorable environments for the implementation and use of AI. The use of cartographic and statistical methods helps visualize and quantify the parameters of AI models used to manage different regions. This allows for a comparative analysis of AI readiness and the degree of AI implementation across other areas of spatial planning and regional development.

To provide more in-depth conclusions from the analysis, we also propose a methodology for calculating the Artificial Intelligence Readiness Index (AIRI) based on indicators of ICT sector development and regional innovation systems. In addition, a correlation analysis has been performed on the relationship between the development of regional innovation systems and regional economic growth rates relative to national GDP.

We use minimum-maximum normalization to scale the values to the range 0–1. This ensures comparability between indicators with different units (e.g., patents versus % coverage). This gives a value between 0 (lowest readiness) and 1 (highest readiness).

Sub-index result = arithmetic mean value of the normalized indicators in this sub-index. In addition, a model for the degree of transformation to Industry 5.0 is also included, which is directly related to the influence of artificial intelligence in terms of digitization and full automation of processes.

Composite

ITI-5.0 = weighted average value of the sub-indices:

Suggested default weights (transparent starting point): D&A = 20%; AI&A = 25%; HCS = 20%; TT-RIS = 20%; EIS = 15%.

Justification: the weight of AI is slightly higher (key factor of 5.0), while maintaining the central role of technology transfer and human resources/sustainability.

Classification (practical levels): Leaders: ITI ≥ 0.75; Advanced: 0.50 ≤ ITI < 0.75; Emerging: 0.25 ≤ ITI < 0.50; Lagging: ITI < 0.25. For the final results and evidence for the hypotheses, the Pearson Correlation Coefficient (r) is:

AIRIi = AI Readiness Index value for region i

GDPGi = GDP growth rate (annual, %) for region i

ȦIRI = mean AIRI across all regions

ḠDPG = mean GDP growth across all regions

n = number of NUTS 2 regions considered

where r ∈ [−1, 1]; r > 0 → positive correlation (higher AIRI → higher GDP growth); r < 0 → negative correlation (higher AIRI → lower GDP growth); r ≈ 0 → no linear correlation. Acceptable range interpretation: |r| ≥ 0.7 → strong correlation; 0.4 ≤ |r| < 0.7 → moderate correlation; |r| < 0.4 → weak or no correlation.

GDP growth as a function of AIRI:

where

This regression expresses the expected GDP growth rate as a linear function of AI Readiness for each NUTS 2 region. The authors use spatial clustering analysis. Spatial clustering patterns are based on Myrdal’s theory of cumulative causation and Kaldor’s concept of increasing returns.

4. Results

4.1. General Characteristics of AI Adoption at the European Level

In semantic networks, Sowa views reasoning as akin to pattern-finding. Davis et al. examine “What is knowledge representation?” from a somewhat abstract, often philosophical point of view, based on five different roles: (i) substitute or replacement for the thing itself (intelligence-artificial intelligence), (ii) set of ontological commitments, (iii) a fragmentary theory of intelligent reasoning (algorithms), (iv) a means of pragmatically effective calculation and (algorithm optimization) (v) a means of human expression, i.e., a language in which we say things about the world (programming realities) [

14,

15,

16]. In conducting a comparative analysis of the application of AI for modeling regional development, traditional scientific methods in regional geography have been used. With their help, we can answer the questions posed in the introductory section of the scientific article correctly. First, we need to clarify the application of AI for industrial development, focusing on labor productivity, workforce quality, and education, and, respectively, increasing incomes. In other words, the marginal utility of such technologies is related to the multiplier effect in the context of system analysis.

From the point of view of linear analysis, the link between AI and regional technological specialisation concerns the diffusion of knowledge, innovation, and know-how that AI itself generates and represents. The abstract concept of generative artificial intelligence is a step towards autonomy in industrial processes and business management. As a result, models for regional development based on big data are more accurate in their forecasts. On the other hand, modeling and precision in goal-setting constitute the highest form of political and geopolitical will for the development of the territory and geospace as a self-organizing system. To reveal the role of AI in the development of territorial systems, we present its application in industrial development, specifically through the implementation of technology across various production processes in enterprises.

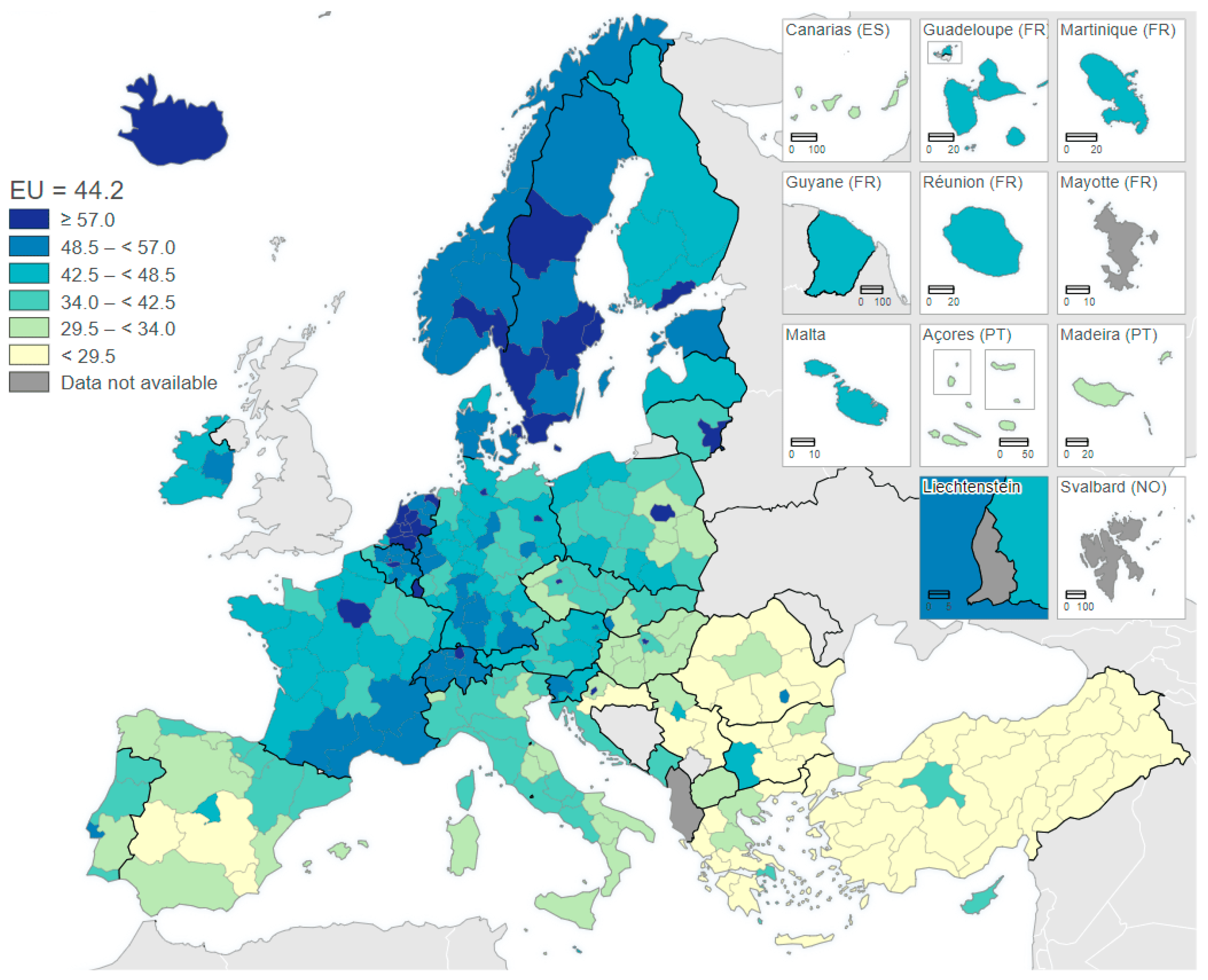

Internet access varies significantly across European countries, as shown in

Figure 1. From this, we can conclude that depending on the speed and coverage of the Internet network, different levels of Internet usage can be observed. In fact, these facts speak to both the level of digital culture among European citizens and the development of digital governance and the digital economy. In this case, we are talking about acquired digital skills, which shows how the education system functions in individual countries. The higher dynamics in the use of information technologies imply technological development, new economic activities, and industries based on innovation, and the implementation of AI. The use of the Internet indicates the technological level of European countries. In other words, these data provide a general idea of the technological development of economic entities in individual European countries and hint at the potential for AI implementation.

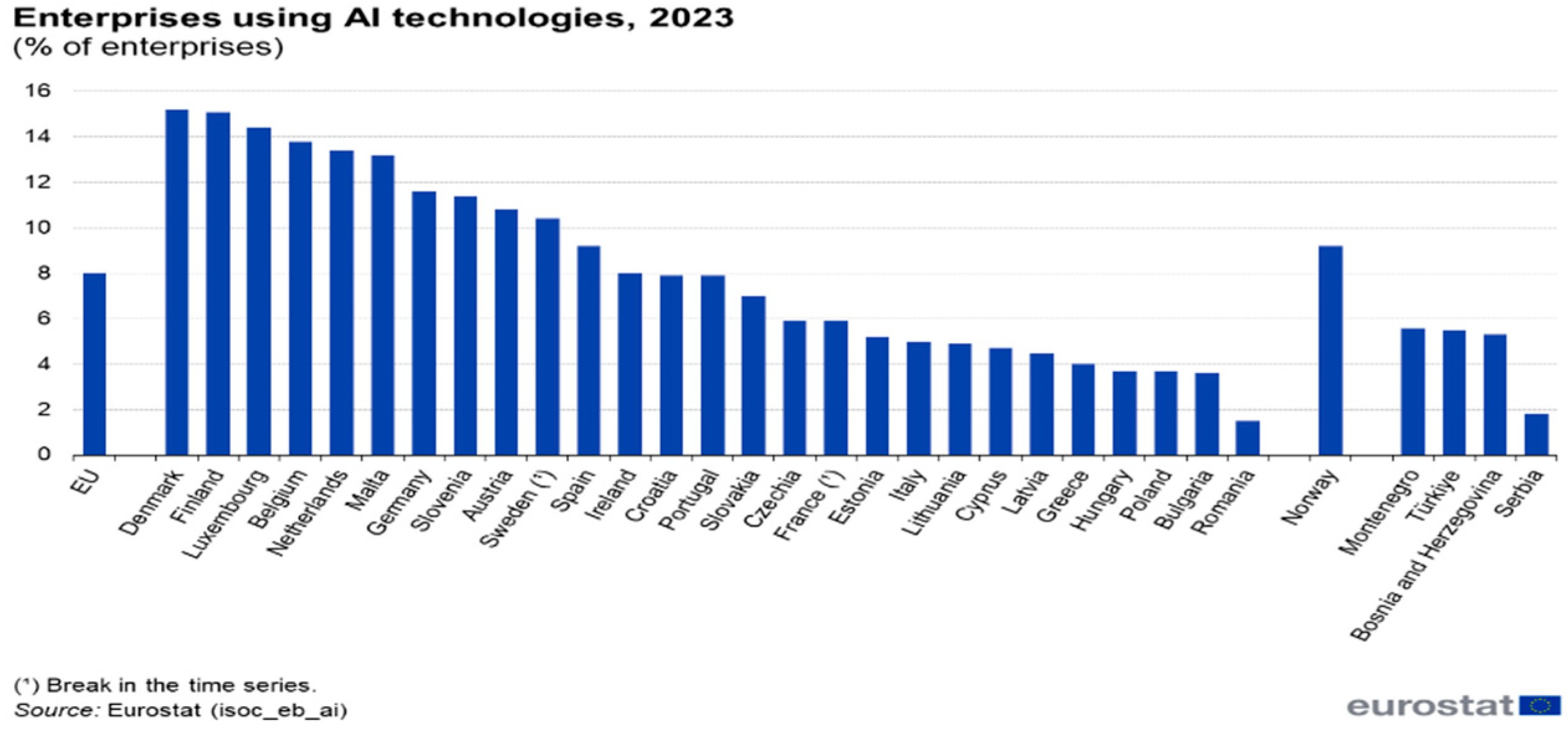

Compared to 2021, the use of technologies with integrated AI has increased slightly by 0.4 percentage points over the last two years (

Figure 2). An analysis of

Figure 2 shows that large enterprises use AI-integrated technologies more than small and medium-sized enterprises. In 2023, 6.4% of small enterprises, 13% of medium-sized enterprises, and 30.4% of large enterprises will use AI for various manufacturing operations.

In this regard, according to Eurostat data, in 2023, around 8% of enterprises in the EU with 10 or more employees and self-employed persons used at least one of the following types of AI:

written language analysis technologies (text extraction);

technologies for converting spoken language into a format that can be read by machine software (speech recognition);

technologies for generating written or spoken language (natural language generation);

technologies for identifying objects or people based on images (image recognition, image processing);

machine learning (deep learning) for data analysis (big data);

technologies for automating various work processes or supporting decision-making (automation of robotic processes using software based on artificial intelligence);

technologies that enable machines to move physically, observing their surroundings and making autonomous decisions based on information about their surroundings collected through sensors.

This difference can be explained, for example, by the complexity of implementing artificial intelligence technologies in the enterprise and the significant need for financial resources to support such systems, economies of scale (i.e., enterprises with -larger economies of scale can benefit more from artificial intelligence due to higher revenues as a result of automation and outsourcing to subcontractors) or costs (investments in artificial intelligence and their maintenance by specialized engineers may be more affordable for large enterprises).

A comparative analysis of enterprises using at least one AI-enabled technology across EU countries (

Figure 3) shows that the share of AI-enabled enterprises ranges from 1.5% to 15.2%. The highest share of enterprises with AI is registered in Denmark (15.2%), followed by Finland (15.1%) and Luxembourg (14.4%), while the lowest shares are registered in Romania (1.5%), Bulgaria (3.6%), and Poland and Hungary (both 3.7%).

The data in the chart (

Figure 3) shows that artificial intelligence is used much more in some economic activities than in others. Therefore, AI is still only applicable to specific activities. In 2023, the information and communications sector (29.4%) and professional, scientific, and technical services (18.5%) had the highest shares of enterprises using AI. In all other economic activities, the share of enterprises using AI is below 10%. This ranges from 8.8% (electricity, gas, steam, air conditioning, and water supply) to 3.2% (construction).

Other analyses can also be performed using the provided data. As can be seen, countries with better internet access and coverage tend to implement more AI in individual enterprises’ economic activities. On the other hand, these countries are among the most developed in the EU. With the use of AI, differences between individual countries and regions are increasing, making it even more necessary to adopt a new type of regional policy aimed at mitigating imbalances. This observation is confirmed by studies within the EU [

60,

61]. The widening differences in investment in and potential for AI adoption are evident in

Figure 4, which shows a strong correlation between AI investment and the degree of regional specialization in the EU. On the other hand, internet usage, digital skills, the quality of public administration, and investment in and implementation of AI (i.e., its use by companies in various industries) are linked to the performance of individual countries and regions. That is why, according to the authors, a regional planning approach is needed to achieve a high degree of regional specialisation, which is at the heart of regional policy. In addition, the use and development of AI in enterprises can be linked to enterprise productivity, which increases [

61]. Higher productivity means more revenue and a higher regional and national gross domestic product. From this perspective, we can interpret the results in

Figure 5 as follows. Countries with the most developed information and communication technology sector are likely to have greater specialization, higher productivity, and conditions conducive to regional sustainable growth and development.

Industrial enterprises in the EU that use different types of artificial intelligence technologies. From the technologies with implemented AI shown in

Figure 5, it is clear that no single AI-related technology predominates. The more common artificial intelligence technologies primarily automate various work processes or support decision-making (e.g., artificial intelligence-based software for automating robotic processes). In 2023, such technologies were used by about 3% of enterprises. The application of this type of know-how is mainly expressed in:

analyze written language (i.e., text extraction)—2.9% of companies;

machine learning technologies (e.g., deep learning) for data analysis;

technologies for converting spoken language into a machine-readable format (speech recognition);

technologies for identifying objects or persons based on images (image recognition, image processing) and

Technologies for generating written or spoken language (natural language generation) are used by between 2.6% and 2.1% of enterprises.

Technologies that enable machines to move physically by observing their surroundings and making autonomous decisions (e.g., autonomous vehicles) are used by less than 1% of enterprises (0.9%). Although not all industries use predominant artificial intelligence technology,

Figure 6 shows a different picture for enterprise size, huge enterprises. The most commonly used artificial intelligence technologies are those that automate various work processes or support decision-making, with 16.4% of manufacturers, followed by machine learning for data analysis (14.6%). The least-used artificial intelligence technologies are those that enable the physical movement of machines through autonomous decisions based on environmental observations (7.0%).

Table 2 presents the different types of artificial intelligence technologies by economic activity. The information and telecommunications technology sector has the highest share of enterprises using AI. The most commonly used technologies are machine learning for data analysis (16.2%) and text extraction (14.2%). In professional, scientific, and technical services, speech recognition is used slightly more often than other artificial intelligence technologies (7.2%), followed by text extraction and artificial intelligence technologies that automate various work processes or support decision-making (both 6.9%) (

Figure 6). In all other activities, the share of enterprises using specific artificial intelligence technologies ranges from 0.9% to 3.9%.

The 2023. 26.2% of enterprises used artificial intelligence technologies in the form of software or other ICT security systems (e.g., machine learning to detect and prevent cyberattacks), while another 25.8% used it for accounting, control, or financial management. Only 9.6% of enterprises using artificial intelligence technologies use software or systems with embedded AI for logistics (

Figure 6). The purposes for which enterprises use AI software and systems vary by size, technological readiness, and specialization. The most significant difference between small and large enterprises is seen in those that use AI software or systems for ICT security (47.9% of large enterprises, 20.5% of small enterprises), followed by those that use them for manufacturing processes (39.4% of large enterprises, 22.3% of small enterprises), and those that use them for logistics (20.6% of large enterprises, 7.5% of small enterprises). Enterprises implement and adapt the technology for different purposes depending on their economic activity. In the manufacturing sector, software or AI systems are mainly used for production processes (38.2%), while in the energy sector, gas supply and water supply (37.6%), and in the information and communications sector (31.6%).

Although some of the most technologically advanced countries are part of the EU or located on the European continent, Europe generally lags in breakthrough (fundamental) digital technologies. These technologies stimulate long-term growth and yield dividends in terms of capital expenditure for regional convergence and can serve as an indicator of the effectiveness of cohesion policy. Around 70% of the fundamental AI models have been developed in the US since 2017, and just three American hyperscalers account for over 65% of the global and European cloud services market. The largest European cloud services operator accounts for only 2% of the EU market. On the other hand, quantum computing is set to be the next significant innovation, given that some of the ten most prominent technology companies in the world in terms of investment in quantum technologies are based in the US, and four in China. None of them is based in the EU, despite the technological advantages of the Netherlands, Switzerland, the United Kingdom, Sweden, and Estonia.

The technological level of European countries is not only reflected in the share of companies using new technologies and artificial intelligence, but also in the percentage of highly educated people in their populations. In

Figure 7, we see the countries that have a higher share of highly skilled employees. Logically, these countries use more innovation, new technologies, and artificial intelligence, which is reflected in increases in gross domestic product.

4.2. Analysis of AI Adoption in EU for Regional Economic Development Using the Composite AI Readiness Index

The Composite AI Readiness Index (AIRI) provides a comprehensive assessment of the capacity of European Union (EU) member states to develop, adopt, and integrate artificial intelligence technologies across economic sectors. The index incorporates seven indicators, grouped into three balanced dimensions: Innovation and Knowledge Base, Business and Human Capital, and Adoption and Infrastructure.

The methodology applies min–max normalization and equal weighting, ensuring cross-country comparability and temporal consistency. This structure allows for balanced measurement of digital maturity, innovation potential, and human resource readiness for AI transformation. At the first stage, the authors performed the calculation at the national level using Eurostat data. After that, the authors used the following method: min-max normalization, three sub-indices (Innovation, Business & Human Capital, and Adoption), and equal weights. AIRI computed where at least two sub-indices are available.

The classification identifies four performance groups: High, Medium, Low, and Negative.

High performers combine technological investment, advanced governance frameworks, and active digital ecosystems. Low- and negative-performing companies remain dependent on imported technologies and exhibit slower institutional adaptation to AI transformation. The analysis shows that Malta, Germany, Bulgaria, and the Baltic countries have strong performance in innovative readiness and AI adoption (

Table 3).

The results reveal a strong north–west-south–east polarization. Northern and Western European economies—such as Sweden, Germany, the Netherlands, and Finland—lead the AI readiness scale, reflecting high innovation capacity, advanced digital infrastructure, and robust R & D ecosystems (

Table 4). In contrast, several Central, Eastern, and Southern European countries lag, constrained by limited R & D intensity, lower AI-related education output, and less dynamic startup environments.

Figure 8 clearly shows the link between countries’ and regions’ innovative capabilities and education. In practice, higher education is a prerequisite for a higher innovation readiness index. Analysis shows that indicator availability across EU27 (counts) is distributed as follows—gdp_pc: 2 countries; productivity: 1 country; ict_share: 20 countries; tertiary_pct: 27 countries; graduates_emp_pct: 27 countries.

The Pearson correlation between national AIRI scores and GDP growth (2022–2023) is weak and statistically insignificant (r = –0.0517,

p = 0.609) [

62].

This finding suggests that short-term macroeconomic performance does not yet reflect AI readiness levels. Instead, AI preparedness acts as a structural factor influencing long-term productivity, innovation diffusion, and competitiveness rather than short-term cyclical growth.

At the level NUTS 2, the authors use the following data for analysis and correlation according to other surveys [

63,

64,

65]:

Innovation & Knowledge Base: intramural R & D expenditure (proxy for patents/investment), R & D personnel (researchers) as proxy for publications.

Business & Human Capital: employment in high-tech sectors (proxy for AI companies/startups), business R & D (proxy for VC/business investment), R & D personnel as human capital.

Adoption & Infrastructure: ICT sector share in GVA and high-tech employment as proxies for AI adoption and digital infrastructure.

Some direct AI-specific indicators (patents explicitly labelled as AI, AI startups, VC) were not available; proxies were used and documented.

At the regional level, AI readiness is highly uneven. Advanced metropolitan and industrial regions—such as Île-de-France, Stockholm, Bavaria, and Lombardy—emerge as technological and innovation hubs. These areas benefit from dense research infrastructures, concentration of universities and R & D centers, and strong business–academia linkages (

Table 5). Conversely, peripheral regions in Southeastern Europe, parts of Spain and Portugal, and the Baltic states display substantially lower AIRI values, often due to weaker innovation systems and limited integration of AI in local industries.

Spatial clustering patterns reveal a core–periphery dynamic, consistent with Myrdal’s theory of cumulative causation and Kaldor’s concept of increasing returns. AI-ready regions attract more investment, talent, and institutional support, reinforcing innovation leadership. Lagging territories face structural inertia, where limited AI capacity constrains both competitiveness and convergence potential.

This uneven geography of technological transformation underlines the critical role of EU cohesion policy in promoting balanced regional development and digital convergence. Targeted interventions in human capital, R & D collaboration, and digital infrastructure are necessary to bridge the AI readiness gap at the NUTS 2 level.

The development trends of the top 5 regions show a decrease during the coronavirus period, followed by a sharp increase in 2024 and, probably, in 2025 (

Figure 9 and

Figure 10). This means the top 5 regions are experiencing sustainable growth driven by innovation and AI adoption. The AIRI trends for the top five areas show that the Bratislava region (Bratislavsky kraj) in Slovakia, Budapest in Hungary, the city of Zagreb in Croatia, Prague in the Czech Republic, and the Eastern and Midland regions show high performance.

Beyond descriptive statistics, the correlation analysis highlights that the relationship between AI readiness and GDP growth is nonlinear and structurally mediated.

Spearman’s rank correlation (r = −0.215) supports the observation that countries with higher AI readiness do not necessarily experience faster short-term economic growth. However, they tend to maintain higher levels of productivity and resilience.

Key determinants of AI readiness include:

The scale and efficiency of national and regional R & D systems;

The quality and specialization of STEM and AI-related human capital;

Availability of digital infrastructure (broadband, 5G, HPC facilities); and

The level of AI adoption in businesses and public administration.

Countries with coherent policy frameworks, effective governance, and strong funding channels for innovation convert AI readiness into tangible economic outcomes more effectively [

66,

67]. Conversely, regions with fragmented innovation systems or low institutional capacity often experience limited diffusion of AI technologies, leading to underperformance despite their potential. The findings confirm that AI readiness is a long-term enabler of technological and economic transformation rather than a short-term driver of growth.

Leave-one-out mean and max absolute differences (AIRI) when removing each normalized indicator: innovation_investment_n: mean_abs_diff = 0.0, max_abs_diff = 0.0, n_affected = 0; researchers_n: mean_abs_diff = 0.0, max_abs_diff = 0.0, n_affected = 0; hightech_employment_n: mean_abs_diff = None, max_abs_diff = None, n_affected = 0; business_rnd_n: mean_abs_diff = 0.0, max_abs_diff = 0.0, n_affected = 0; ict_share_n: mean_abs_diff = 0.0, max_abs_diff = 0.0, n_affected = 0; Correlation between equal-weight AIRI and dimension-weighted AIRI (30/40/30) is none.

The analysis confirms that AI readiness across the European Union remains highly uneven, both at the national and regional levels. The spatial distribution of AIRI scores reveals a pronounced technological core–periphery divide, with Northern and Western Europe functioning as centers of innovation and Southern and Eastern regions remaining in an adaptive development phase. The weak correlation between AI readiness and short-term GDP growth suggests that the economic effects of AI are not immediate but accumulate gradually through innovation, productivity enhancement, and structural transformation (

Table 6). Compared to other regions, such as China, European regions are lagging [

67]. However, comparative analysis shows the great importance of building capacity for the development of regional innovation systems [

68].

5. Discussion

The lack of a targeted EU-level strategy for cloud computing is widening the gap in competitive technological advantage. This is determined by the nature of the technology, which needs continuous investment, economies of scale, and a large volume of skilled human resources. However, there are many reasons why Europe should not give up on developing its domestic technology sector, in particular, supercomputing and AI. First, EU companies must maintain a position in areas where technological sovereignty is required, such as security and encryption (sovereign cloud solutions). Second, the underdeveloped technology sector limits innovation performance across a wide range of related industries, including pharmaceuticals, energy, automotive, the circular economy, and defense. Third, artificial intelligence—and, in particular, generative artificial intelligence. It is an emerging technology in which EU companies and regional growth centers can still secure a leading position in selected segments. For example, Europe leads in autonomous robotics, where around 22% of global activity occurs, and in AI services, where around 17% of global activity occurs. However, innovative digital companies generally fail to scale up in Europe and attract funding, resulting in a significant funding gap later on between the EU and the US. In fact, in the EU, no company with a market capitalization of more than EUR 100 billion has been created from scratch in the last forty years. In contrast, in the US, all six companies with valuations exceeding EUR 1 trillion (Google, Amazon, Meta, Apple, X, and NVIDIA) were created during this period.

AI readiness represents a deep-seated component of national competitiveness, embedding the capacity to innovate, learn, and integrate new technologies across institutional and industrial domains. Its impact extends beyond conventional economic cycles, acting instead as a transformative mechanism that shapes the long-term trajectory of regional development. The empirical results reinforce the importance of fostering R & D collaboration, strengthening AI-specific education, and expanding digital infrastructure as central elements of cohesive European innovation policy.

At the NUTS 2 level, the top ten regions are located in Western and Central Europe. These regions are assessed against the innovation readiness index, which mainly reflects the development and implementation of artificial intelligence. The assessment is based on the formation of a regional innovation system, in which the incorporation of artificial intelligence technologies is critical to its effective performance. For example, in Montreal, the regional innovation system is developing through the use of artificial intelligence in industry [

69]. In practice, regional innovation systems are based on the development of artificial intelligence, as shown by some recent studies [

70,

71]. Correlation analysis establishes a strong link between the composite AI readiness index, artificial intelligence, and educational attainment. The strong link between universities and industry, expressed through the development and application of artificial intelligence, has been analyzed in China, which fully confirms the results of this study [

72]. Artificial intelligence already plays a vital role in the development of a regional innovation system and can be seen as an instrument of regional policy. On the other hand, artificial intelligence serves as a link between universities, scientific organizations, and industry at the regional level, contributing to the formation of a regional innovation system [

73,

74,

75].

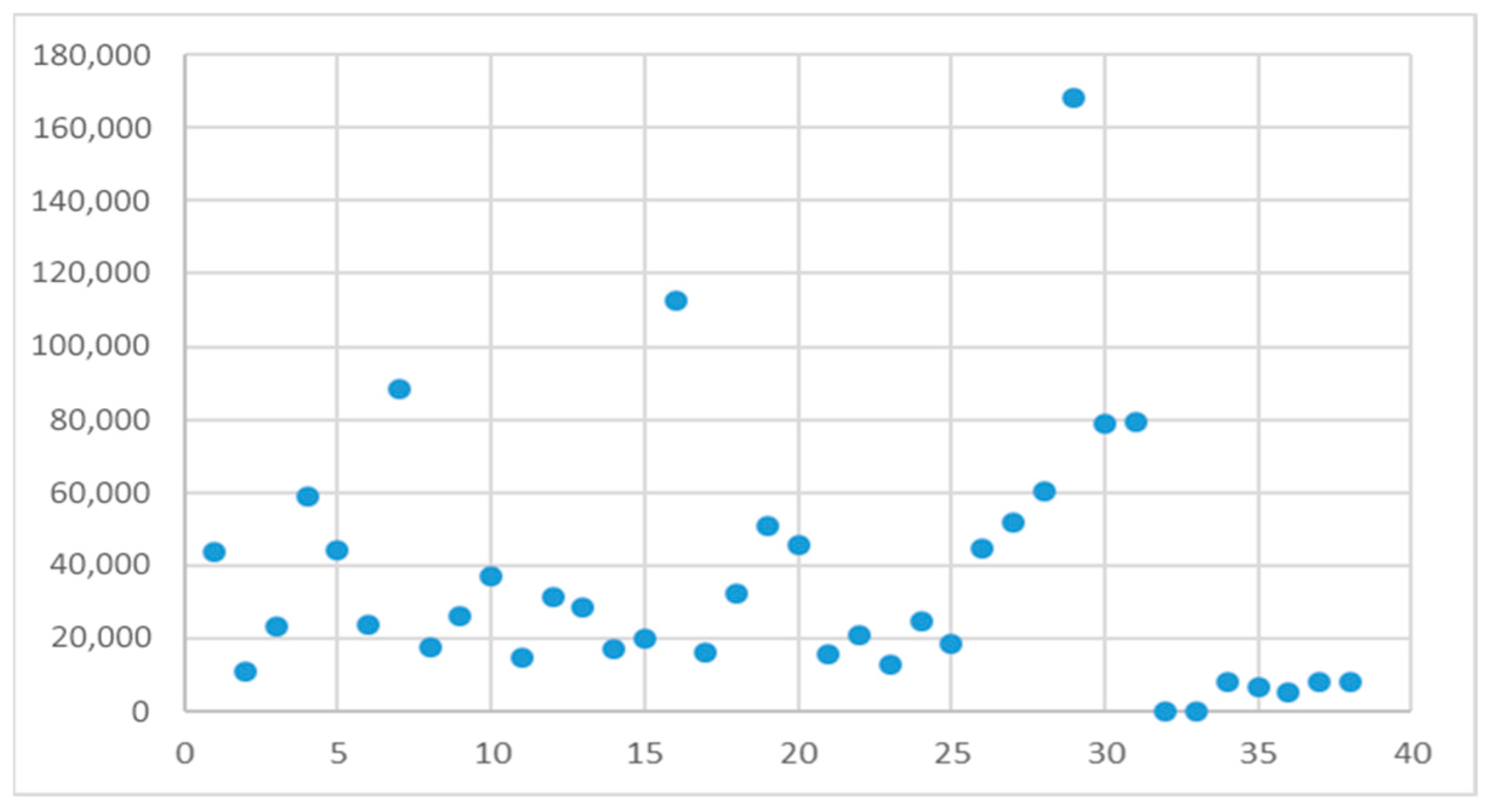

Based on the spatial and economic analyses, the authors conduct a correlation analysis to examine the relationship between the gross domestic product of European countries and the share of the ICT sector, on the one hand. On the other hand, the authors examine the relationship between GDP and the level of education among the European population. In

Figure 11, we see a moderate relationship between the share of the ICT sector and GDP. We observe that the share of this sector is small, which does not have a substantial impact on the economic development of European countries. These results show that the deployment of artificial intelligence remains low. Also, the technological level has a significant effect on the development of countries.

Figure 12 plots the degree of correlation between the level of education of the European population and the GDP produced in 2023. We can see a correlation. The more educated the population, the more technologically advanced a European country can be, and the higher its GDP.

To achieve sustainable convergence, the EU must direct policy efforts toward enhancing human capital formation, supporting AI entrepreneurship, and integrating lagging regions into continental innovation networks. Addressing disparities in AI readiness is not merely a technological goal but a strategic necessity for ensuring social and territorial cohesion in the era of digital transformation. In essence, AI readiness serves as both a barometer of technological potential and a catalyst for inclusive, resilient economic growth across the European Union [

71,

72,

73,

74,

75,

76].

Thus, the described results stem from the lack of a regional policy that accounts for technological evolution. This type of policy should aim to build regional scientific hubs and centers, stimulate scientific and educational institutions, and strengthen interaction among regional and local actors in the regional development process. This is why modern regional policy must make full use of AI to address regional inequalities, close the technological gap, and boost European competitiveness.

This study fills an existing gap in the scientific literature by analyzing the interaction between artificial intelligence and the regional innovation system and its effects on regional development in Europe. The authors propose an index to compare European regions in terms of their innovation readiness and the adoption of artificial intelligence.

Viewing AI as a regional policy tool, central locations or innovation hubs can play a key role in advancing policies that stimulate innovation, STEM centers, technology parks, and R & D through planning and localization choices informed by AI-based models. Areas with existing high-level technological infrastructure and human capital benefit more readily from implementing AI and applying it to regional development management, thereby strengthening the role of central locations with technological competitive advantages in the dissemination of impulses and the diffusion of technologies.

AI is A promising and valuable tool for addressing various localisation issues in urban planning, such as reducing traffic congestion through traffic management systems, improving waste management, enabling mobile urban mobility services, and more effectively integrating urban transport and social services systems. On a broader territorial scale, the technology can be applied to improve resource allocation in areas such as recycling, sustainability, and energy and resource conservation. On the other hand, the digitization of administration leads to improved social services and the successful integration of horizontal policies that operate locally. However, in relation to the previous conclusion, efficiency varies significantly across regions due to differences in technological readiness, capital expenditure availability, intangible resources (knowledge and software), and human capital.

The main limitation of the study is the lack of sufficient regional-level data for collection and analysis. The reason is that the development of artificial intelligence is highly dynamic, setting the pace for economic processes and driving economic transformation. For this reason, there are two limiting factors: there is no established model for assessing and measuring artificial intelligence and its implications for the economy; the time period during which processes related to artificial intelligence occur is very short, and there is no accumulated statistical information. For this reason, it is difficult to identify the points of contact between artificial intelligence and regional development and to measure its impact on regional-level socio-economic processes.

6. Conclusions

This study attempts to determine the impact and potential of AI on the development of European regions. The authors examine the development and implementation of AI as a modern tool of regional policy. In this way, regional disparities can be overcome, urban planning optimized, and the technological gap reduced both within the EU and between the EU and the world’s most innovative economies. However, significant barriers remain, especially in regions without robust digital infrastructure. Policy interventions should focus on digital inclusion, the promotion of innovation hubs, and the provision of resources for AI implementation. Future research could examine the longitudinal effects of AI-based policies in different regional contexts and assess the social and ethical considerations associated with AI in public policy.

Based on the study, the authors reach important and interesting conclusions. The analyses show that the EU countries with the highest innovation index (i.e., those that allocate more funds to research and development and to the implementation of new technologies) are those characterized by the highest share of industries using AI in their economic activity. These same countries have the highest share of the ICT sector in their economies. The territorial and geographical analysis of the distribution of technology sectors across European countries and the use of AI shows a clear concentration that affects countries’ economic growth and development. As we know, high-tech industries are characterized by high added value. Such countries are the Scandinavian countries (Denmark, Finland, Sweden), France, the Netherlands, Luxembourg, Belgium, and, outside the EU but in Europe, the United Kingdom. The diffusion of know-how, knowledge, new technologies, and AI does not follow any specific pattern in its territorial spread. At the same time, however, geographical distribution is linked to investment activity, and this process can be managed within European countries and regions. This role can be played by regional policy, which directly relates to the EU’s smart specialization strategy for areas [

77].

Obviously, the potential for using AI in the economy is enormous. In this sense, countries can incorporate the development and implementation of AI into their regional development strategies. In this study, the authors have attempted to demonstrate not only the role of AI in the development of countries, but also that it can be seen as a modern tool of regional policy. In this regard, the main conclusion is that limitations in data volume and territorial scope, the lack of digital infrastructure, and the high implementation costs in some European regions are significant obstacles to integrating AI into regional policy, urban planning, and resource management [

77,

78].

The AI readiness index shows that only 10 regions are performing well at the regional level, while 108 others are performing poorly. Long-term trends show fluctuations across regions, but the top ten continue to drive economic development through the adoption of artificial intelligence. Based on the correlation analysis, we see a strong link among the use of artificial intelligence, regional performance, and educational attainment. On the other hand, there is no strong link between the AI readiness index and the increase in gross domestic product. A possible explanation is that sectors that use artificial intelligence represent a small share of the economy and, accordingly, their contribution is minor.

The limitations of the study stem from the very nature of economic development, which is influenced by artificial intelligence. The dynamics of the development of artificial intelligence and its application in the economy are very high. As a result, insufficient data are collected at the lower regional level, and a research framework is lacking that defines the basic indicators for which statistical information is collected and processed. For this reason, it is difficult for authors to apply the analysis framework to smaller regions and municipalities in the EU.

Studies such as this contribute to both the development of regional science and the analysis of the relationship between artificial intelligence and regional development. In the future, the study could be expanded by deepening the analysis of the role of artificial intelligence in the smart specialization of regions, viewed through the prism of regional innovation systems. In this regard, future studies should identify the points of contact between artificial intelligence and regional policy that shape the regional ecosystem.