Highlights

What are the main findings?

- The assessment of the quality of life in cities varies due to demographic, social, and geographical characteristics and cannot be generalized (the differences may be ambiguous and multidirectional).

- At the regional level, despite similar socioeconomic conditions, there are significant differences in the residents’ quality of life, creating a risk of imbalance and exclusion of some cities from further regional development.

- The perspective of the quality of life varies in different groups of residents; however, the identified differences do not always correspond to the generally accepted direction of exclusion.

- The quality of life is moderately positively correlated with the economic conditions of cities, but this is not the only condition for a higher quality of life and a city’s aspiration to be smart.

What are the implications of the main findings?

- Theoretically, the analysis provides new knowledge on the diversity of quality-of-life assessments in cities depending on the demographic and social characteristics of residents and the regional location of cities.

- In practical terms, the study provides information on the assessment of quality of life from the perspective of residents (very rarely found in the literature) of large cities located in a developing economy.

- In terms of recommendations, the results of the study indicate directions for improving living conditions in cities and the Silesian province, which can also be used in other geographical locations.

Abstract

The inspiration and main goal for creating smart cities is to improve the quality of urban life. However, this ambitious task is not always successful as urban stakeholders are not homogeneous. Their experiences and expectations can vary significantly, which ultimately affects their level of satisfaction with life in the city. This article assesses the quality of life in 19 cities with county rights located in the Silesian province of Poland. The assessment takes into account stakeholders’ age, gender, education, and household size. The study also assesses the geographical variation in the quality of life in individual cities in the region with a view to individualizing the management approach. The research methodology is based on a survey conducted in a representative sample of 1863 residents of Silesian cities. The results are analyzed using descriptive statistics and nonparametric tests. The conclusions indicate a lower quality of life for women, residents aged 31 to 40, and people with primary education and a bachelor’s degree. The quality of life is significantly worse in post-mining towns where economic transformation has not been successfully implemented. The quality of urban life is rated highest by men, older people, and residents with basic and secondary education. Communities living in cities with modern industry and a stable economic situation are very satisfied with their standard of living. The results of the study imply the need for an individualized approach to shaping living conditions in cities and the implementation of remedial measures for groups and cities at risk of a lower quality of life. This will help to balance the quality of urban life and prevent various forms of exclusion.

1. Introduction

The concept of a smart city (SC) has been developing rapidly in recent years in the literature, in research, and in practice [1,2,3]. The status of being ‘smart’ is synonymous with an above-average quality of life, a distinguishing feature that improves the image of a city and attracts investors and new residents [4,5,6].

The primary goal of smart city development is to improve the quality of life for residents, who are stakeholders. Smart solutions are created principally for them across key areas of urban life. Currently, there is increasing emphasis on improving the urban quality of life for future generations while ensuring the full sustainability of smart cities. Therefore, quality of life remains central to the smart city concept.

There is nothing surprising or wrong with striving to be ‘smart’, as we all want to live longer and better lives. The smart city concept is, therefore, merely a response to human desires and expectations. In general, its theoretical assumptions do not raise major objections [7,8].

Nevertheless, as with any other activity, the implementation of the SC concept has risks that can lead to distortions and irregularities in the functioning of smart cities. One of the most serious implementation risks is the risk of excluding ‘weaker’ (for many different reasons) urban stakeholders [9,10,11,12]. This is most often manifested in limited access to the smart city’s offerings. The reasons for this may include age, gender, origin, religion, and other characteristics that differentiate local communities [13,14]. This exclusion can result in not only limiting the benefits of smart cities, but also in disappointment and frustration [15,16]. Both above circumstances will have a negative impact on the assessment of the urban quality of life by less satisfied and excluded stakeholder groups.

Exclusion may also affect entire regions and individual cities, which, for economic or other reasons, are unable to catch up with smart cities operating in highly developed economies [17,18,19,20]. Then, dissatisfaction with the quality of life may affect entire local and regional communities. In extreme cases, this can lead to conflicts, demonstrations, and protests, highlighting international and inter-regional differences.

In the context of the importance of quality of life in smart cities, the lack of research into the residents themselves is surprising. Few analyses address residents’ individual feelings about urban life. However, without identifying residents’ well-being, effective management decision-making is virtually impossible. This situation illustrates a significant gap between smart city declarations and their actual implementation.

Beyond the lack of resident-focused quality of life research, several other circumstances justify this article’s focus, as detailed in the literature review and hypothesis development sections. These include the following:

- the need to assess the quality of life in cities aspiring to smart status within emerging economies;

- the necessity of evaluating quality of life disparities based on sociodemographic characteristics (age, gender, education, economic status) that signal potential exclusion risks;

- and the need to expand knowledge regarding residential location impacts on quality of life on the regional scale.

There are many ways to measure quality of life. Most of these are based on a top-down approach, which aggregates different perspectives into a coherent and uniform indicator. Examples include the Human Development Index (HDI), World Health Organization Quality of Life (WHOQOL), and the Quality of Life Index. The ISO 37120:2018—Sustainable cities and communities, ref. [21] adapted to the needs of cities, also offers a broad approach to assessment. The advantages of these methods include their universality and the possibility of making easy comparisons.

However, their main drawback is their inadequacy for the analysis of local conditions and the failure to consider individual perspectives. For these reasons, in this article, the assessment of the quality of urban life is entirely based on the perceptions of residents, as direct recipients of city authorities’ decisions related to shaping living conditions.

In view of the above circumstances, the main objective of the research presented in this article is to assess the quality of life in cities from the perspective of various groups in the local community and from the perspective of different geographical locations. These analyses allow us to answer the following research questions:

- Which social groups assess the quality of life in the city as worse and are potentially at risk of exclusion?

- In which cities in the region do residents live in worse circumstances, and are these cities at risk of pauperization, depopulation, and rapid aging of the local community?

To determine answers to these research questions, a survey was conducted in 19 cities located in the Silesian province of Poland. These are large cities, units with county rights, which are familiar with the smart city concept and aspire to be ‘smart’ and implement solutions in the field of intelligent urban infrastructure. The survey included 1863 residents, with a representative sample for each city.

Research from the perspective of residents has very rarely been conducted in the related literature, as it is time-consuming and often costly [22]. It is also difficult to ensure the representativeness of such research. Nevertheless, given the assumptions of the smart city concept, it is the residents who should answer the question about the quality of life in the city to assess the effectiveness of the implementation of smart urban solutions.

This answer is also linked to the assessment of the sustainability of the implementation of the smart city concept. The greater the dissatisfaction and diversity of assessments of quality of life among different social groups, the greater the social, demographic, and geographical imbalance. Such unbalanced implementations can lead to exclusion and distortion of the smart city concept, negating its original aim.

This research contributes to the development of the smart city concept in the following ways:

- It presents empirical research results on implementing the smart city concept, providing a valuable practical perspective in a field dominated by theoretical considerations.

- It presents conclusions from residents’ perspectives, offering a grassroots analysis rarely found in the literature.

- It uses statistical research on a large representative regional sample, unlike the popular case studies of individual cities.

- It analyzes smart city implementation in cities from developing economies that aspire to become “smart”.

- It describes social exclusion from the perspective of different groups—by gender, age, education, and household size.

- It discusses regional exclusion of cities—a topic rarely addressed in the literature.

- It identifies real (not theoretical) gaps in urban quality of life and helps develop remedial actions for sustainable city management.

2. Literature Review

The starting point for this research was a literature review covering two main research themes. Based on this review, a research gap was identified that needed to be filled, and research hypotheses were formulated for verification through the survey.

2.1. Quality of Life in the City in the Light of the Literature Analysis

Quality of life is a flagship priority in smart cities. However, as already mentioned, it is rarely analyzed from a bottom-up perspective based on the opinions and views of residents. This subsection includes the most relevant research and analysis conducted in this area.

Attempts to categorize and quantify quality of life have been undertaken for a very long time, both in the literature and at the institutional level. There has also been a long-standing debate about whether quality of life is determined by material or spiritual goods. Similar reflections accompany the development of Smart Cities. It is now believed that residents’ quality of life cannot be determined solely by the implementation and use of ICT. This corresponds to the assumptions of Amartya Sen’s concept [23,24,25], in which quality of life is assessed in the context of capabilities and functioning. Adapting this approach, a Smart City should provide the local community with comprehensive proposals for activities and development. Residents, in turn, freely choose what, how, where and with whom they want to implement. Urban quality of life is therefore closely linked to freedom and the right to self-determination.

At the institutional level, the World Health Organization [26] has attempted to systematize and comprehensively measure quality of life. According to its standard, quality of life is an individual’s perception of their position in life in the context of the culture and value system in which they live, and in relation to their goals, expectations, standards, and concerns influenced by environmental conditions. Consequently, quality of life is a subjective assessment of everyone, and in the case of Smart Cities, of each resident. It is determined by four groups of very diverse conditions concerning: physical health, mental health, environment, and social relations. This approach is consistent with the idea of fully sustainable smart cities, which develop not only in material terms, but also in social and environmental aspects. The World Health Organization Quality of Life methodology utilizes a bottom-up approach. Quality of life is assessed based on individual experiences and perceptions of respondents. This approach has also been used in this article, but it has been applied strictly to urban quality of life as the main postulate of the Smart City concept.

The analytical frameworks for defining and assessing quality of life described above fit into the positive psychology movement [27,28,29]. According to this approach, quality of life is determined by both objective and subjective factors [30]. The former, in the case of Smart Cities, will concern external conditions, including housing situation, accessibility of healthcare services, and education. The latter will relate to residents’ feelings, including mental state, generalized sense of happiness, and level of security. Both factors can determine the overall assessment of quality of life to varying degrees.

In this article, quality of life is described in the context of Smart Cities. For these reasons, the subsequent part of the literature review focuses on previous research undertaken in this area.

As Chang and Smith (2023) [31] note, quality of life as an aspect of SC functioning has only gained popularity in the last five years. Researchers are particularly interested in issues such as smart urban management [32,33], sustainable development, smart living, participation, and social inclusion [34,35]. They also emphasize that although residents experience smart city initiatives collectively, they assess quality of life individually, depending on their personal priorities and expectations. This observation relates to the general concepts of quality-of-life assessment described at the beginning of this subsection. Moreover, it emphasizes the importance of sustainability in smart cities. Without social, humanistic, or environmental elements, urban quality of life is not complete.

Survey research on the quality of life in smart cities was conducted by Macke et al. (2018) [36]. Their analysis covered a group of 400 residents of Curitiba, a city in southern Brazil. The results indicated four key areas for shaping the desired quality of life in an SC. These are social and structural relations, environmental well-being, material well-being, and social integration. Therefore, the quality of urban life is influenced not only by economic factors but also by relational factors related to social cohesion and integration. These threads also appear in further studies [37,38,39,40,41].

Determinants of quality of life were also identified by Chen et al. (2022) [42] using the example of Macao, China. In their survey, they identified five factors that have a positive impact on the quality of life in a smart city. These include a smart environment, smart people, smart living conditions, smart economy and economic policy, and smart mobility. These factors are directly related to six areas of development of modern smart cities, which also influence their sustainability, as described by [43,44]. This illustrates a certain conceptual and practical consistency in research on smart urban solutions. Moreover, these studies indicate a balanced impact of technical and social infrastructure on residents’ quality of life. This relates directly to Amartya Sen’s concept and positive psychology.

Unfortunately, this consistency is not always found in practice. According to research by Vázquez et al. (2018) [45] conducted among Spanish students, there is a significant gap between the design and the experience of quality of life in the various dimensions of a smart city. The greatest discrepancy concerns the smart economy and smart governance, i.e., areas for which the city authorities are directly responsible. Therefore, research conducted from a government perspective may be less reliable than the opinions of residents. The above results inspired the author of this article to become interested in assessing urban life from the residents’ perspective, detached from measurable infrastructural indicators, and in connection with the subjective feelings of residents, the most important stakeholders of smart cities.

Wang and Zhou (2023) [46] also considered the factors shaping the quality of life in China. They divided these determinants into two groups related to two key strands of smart city analysis. The first was modern technologies (the technological strand) [47,48,49], and the second was human capital (the humanistic strand) [50,51,52]. Their results indicate that ICTs are negatively associated with life satisfaction and the frequency of happy (positive) emotions but are not associated with depressive (negative) emotions. Human capital, in turn, has a positive impact on life satisfaction and the frequency of happy emotions, but it has a negative impact on the frequency of depressive emotions. The quality of life is also influenced by the level of corruption and the efficiency of the authorities. The researchers also noted that the assessment of the quality of life depends on the age and education of the residents. The above results clearly indicate discrepancies in the assessment of quality of life from the perspective of city authorities and from the perspective of local communities. They also emphasize the lack of identification of residents’ expectations. Smart cities very often focus on ICT implementation, even though for local communities, social relations and transparency of local government decisions are most important.

The above conclusions suggest that modern technologies are a prerequisite for the existence of a smart city, but they do not necessarily determine the total quality of life of its residents, although the quality of life does depend in part on the type of technology and its role in everyday life. This was also pointed out by Dameri (2016) [53], who emphasized the importance of ICT in the mobility of residents, an aspect of life that is important for all stakeholder groups. Therefore, in transport and logistics, quality of life is significantly supported by modern technological solutions, as also confirmed by research conducted by Persaud et al. (2018) [54]. Consequently, technological aspects are important for smart cities, but they must be balanced by social and environmental factors.

Additionally, modern technologies and social integration should also be accompanied by sport and recreation as important factors shaping the quality of urban life, as described by Tjønndal and Nilssen (2019) [55]. They emphasize that the activation of the local community can become an effective panacea for economic crisis, which, in their analysis, was the closure of the air force base in Bodø (Norway). These observations confirm the complexity of the quality of life described at the outset. They also acknowledge the importance of well-being in assessing this quality.

According to Wolniak and Jonek-Kowalska (2021) [56], the standardization of assessment and monitoring of this parameter by city authorities is also important in shaping the quality of life. Nevertheless, these researchers’ view of satisfaction with urban life was conducted top-down, starting with the perspective of urban strategy makers and, therefore, may not be completely objective. There is therefore a need to assess urban quality of life independently from economic and infrastructural indicators. This stems not only from the lack of such analyses but also from the necessity of looking at smart cities through the eyes of the local community.

2.2. Quality of Life in the City and Social Exclusion

Based on the literature review, several key observations can be made that imply the need for in-depth research into the quality of life from the perspective of residents. First, there are many determinants of satisfaction with urban life and, as the studies described here indicate, these are not limited to modern technologies. Social capital and interpersonal relationships are also important. These determinants can only be properly assessed from the perspective of the local community.

Second, areas such as economics and governance are underdeveloped in smart cities. Despite this, most quality-of-life analyses are conducted by the city authorities responsible for these areas. Therefore, their validity and objectivity are questionable.

Third, assessments of the quality of life in a diverse urban community can vary. Therefore, quality-of-life policies in cities should be tailored to various expectations, needs, and deficiencies. Quality of life should therefore be viewed from the perspective of varied stakeholder groups. Among them, residents potentially at risk of exclusion have an important place, as their quality of life is generally lower.

There are several vulnerable social groups, particularly at risk of exclusion. Based on the previous research on smart cities, as well as on more general considerations related to exclusion, several characteristics can be identified that predispose people to being excluded and, therefore, not fully participating in the benefits of urban life. These include the following:

- Gender;

- Age;

- Education;

- Economic status.

In the context of gender, women are considered more vulnerable to urban exclusion. As Calvi (2022) [57] notes, this risk can also be exacerbated by their origin, race, sexual orientation, and abilities. According to the author, there is also a lack of research on the oppressive effects of smart cities on women in various aspects and on laws preventing the effects of gender-based exclusion.

Elanda et al. (2022) [58] also add that women in emerging and developing economies are vulnerable to a poorer quality of life in smart cities. They document this claim with research from the Indonesian economy, which is part of the 100 Smart Cities program, as an example. Singh (2019) [59] advances this argument, stating that smart cities generally overlook women’s needs in mobility; most mobility solutions are geared toward men’s expectations and exacerbate gender-based exclusion.

The situation of age-based exclusion is somewhat different and not necessarily better. Li and Woolrych (2020) [60] note that older people appear in smart city literature. However, these considerations constitute a specific sideline, primarily relating to health and social care. Yet, seniors should be an integral part of the urban community, and local governments should not offer them separate policies and solutions. Such an approach is inherently exclusionary. Similar conclusions and recommendations were also formulated by Jonek-Kowalska and Wolny (2024) [61], based on extensive literature studies, and by Buffel et al. (2020) [62], based on case studies.

Research conducted in a somewhat broader context by Olsson et al. (2017) [63] shows that cognitive skills, including the ability to use modern technologies, deteriorate with age. This relationship can lead to the exclusion of seniors from smart city life based on the use of IT and ICT.

This will also affect residents with lower levels of knowledge and education. Smart cities are highly demanding infrastructures. Albuquerque (2017) [64] highlighted this in her discussion of the inclusiveness of smart cities, in terms of the learning capacity of local communities. Smart cities develop not because of modern technologies but through the utilization of human capital equipped with specific knowledge, competencies, and skills. Therefore, their absence can also lead to various forms of exclusion.

Further, as Van Twist et al. (2023) [10] note, some of the residents of smart cities are not even able to express their dissatisfaction with the existence of smart cities due to a lack of digital skills and access to the Internet, which further stigmatizes and excludes them.

This threat is closely related to economic exclusion. Greene et al. (2016) [65] distinguish four dimensions. The first refers to the labor market, which in SC is characterized by high potential only for people with higher education and very good digital skills. The second concerns wage stagnation for low-skilled residents. The third is related to the lack of security for low-income households in the event of economic crises. The fourth is a consequence of the previous ones: residential segregation (rich and poor residents live in separate neighborhoods).

The threat of exclusion from urban life presented above is not directly linked to a poorer quality of life. However, in practice, it can translate into it. For these reasons, this article not only identifies the quality of urban life in an emerging economy but also attempts to answer the question of the level of urban life quality among groups at risk of exclusion due to gender, age, education, and social status. Hence, the results described contribute not only to policies for shaping quality of life in cities but also to principles for counteracting exclusion.

2.3. Identification of a Research Gap and Formulation of Research Hypotheses

The results of the previous studies on the quality of life of residents presented above lead to the following observations:

- Quality of life is most often assessed indirectly—through the impact of various factors on satisfaction with urban life.

- Numerous studies, including direct ones, focus on the determinants of quality of life, without paying attention to the assessment itself and its diversity.

- Literature does not provide a comparative analysis of quality of life, whether local, regional, national, or international, which could have important implications for urban management.

Given the above, there is a two-part research gap. The first is the lack of research conducted from the perspective of residents. The other is the lack of research on the diversity of quality-of-life assessments in the city according to different social groups. Meanwhile, as emphasized above, the perception of a smart city is collective, but the feelings associated with it are individual.

In view of the above circumstances, the main objective of the research presented in this article is to assess the quality of life in the city from the perspective of various groups representing the local community and from the perspective of different geographical locations. These groups were identified based on the risk of social exclusion and the need to ensure social sustainability in smart cities [66,67,68].

Thus, according to the literature, one of the groups at risk of exclusion in a smart city is women, especially in economies where they are perceived mainly in the context of traditional family roles [69,70,71,72]. Women also often have limited access to education, making it difficult for them to use modern urban digital technologies [73,74,75]. As a result, this group may feel worse in a smart city and, consequently, perceive a lower quality of urban life than men. For these reasons, the first research hypothesis was formulated as follows:

H1.

There are statistically significant differences in the assessment of the quality of life in the city between women and men.

Seniors are also at risk of social exclusion in smart cities [76,77]. In their case, this can lead to both digital exclusions, related to limited access to knowledge, and economic or social exclusion [78,79,80,81], due to health problems or low pensions [82]. Given the lack of broader research on the relationship between quality of life and the age of residents, we decided to generalize the second research hypothesis by referring to the age diversity of the entire urban community. It was formulated as follows:

H2.

There are statistically significant differences in the assessment of the quality of life in the city between different age groups.

A review of the literature shows that quality of life may also vary depending on the level of knowledge of the local community [83,84,85]. Knowledge of modern technologies is generally better among residents with higher levels of education [86,87,88]. Income levels and living conditions are also closely linked to professional status and position in the labor market. These, in turn, are a direct result of qualifications. It can therefore be assumed that the assessment of quality of life in a city may be linked to the education of its residents. For these reasons, the third research hypothesis was formulated as follows:

H3.

There are statistically significant differences in the assessment of quality of life in a city depending on the individual’s level of education.

One of the important dimensions of a smart city is also its economy and the related level of well-being of its residents. Many studies emphasize the role of this factor in shaping life satisfaction [89,90,91,92,93]. It seems to be particularly important in developing and emerging economies with low disposable income levels. Basic conditions determine the quality of life in a primary existential way. Only after basic needs have been met can expectations change and grow. The number of people in a household is linked to income levels: the more people, the more difficult it is to achieve a higher economic status and find time for paid work. For these reasons, the fourth research hypothesis was formulated as follows:

H4.

There are statistically significant differences in the assessment of the quality of life in a city depending on the number of people in a household.

As already mentioned, the quality of life in modern large cities should also be viewed in the context of regional, national, and international differences [94]. They are particularly important in the process of benchmarking and improving city management. Cities should therefore measure quality of life and compare it on different scales and at different levels [95,96]. Such studies are very rare. This is especially true when they are conducted at the same time and in the same region using the same measurement scales. For these reasons, the fifth research hypothesis was formulated as follows:

H5.

There are differences in the assessment of the quality of life in cities at the regional level.

The above hypothesis is innovative. Research at this level regarding the quality of life in smart cities has not yet been conducted.

All the above hypotheses and the research questions posed in the Introduction were assessed using the results of the survey described in Section 4, taking into account sociodemographic and geographical differences. The results are preceded by a methodological section containing a description of the research tools.

All formulated hypotheses are non-directional due to the lack of clear research results in the analyzed areas. This approach is recommended and acceptable in the case of phenomena that have not been fully understood [97,98].

3. Materials and Methods

The literature review presented in the previous section enabled the identification of a research gap and the formulation of specific hypotheses. The way to fill this gap and the methodology for verifying the hypotheses are presented in this section. For this purpose, the research objectives are specified, and a research method focused on diagnosing public opinion is described. Subsequently, the studied cities and the principles of respondent selection are characterized. Within the methodological framework, statistical research tools and limitations of the adopted approach are presented.

3.1. Research Assumptions

As previously mentioned, the purpose of a smart city is to improve the quality of life of its residents. Therefore, there is a close connection between assessing the quality of life and assessing the effectiveness of the smart city concept’s implementation. However, quality of life itself should not be assessed solely by city authorities, experts, or scientists. It should be viewed from the perspective of residents, including those at risk of exclusion and, consequently, of a poorer quality of life. For this reason, we present a bottom-up methodology for evaluating the quality of life, considering the diversity of respondents in terms of their gender, age, education, and household status. These determinants were identified based on the literature review, which also served as the basis for formulating the research hypotheses.

In addition, the study identified the level of variation in the quality of life geographically. It sought answers to questions about the relationship between life satisfaction and individual determinants of urban policies and the regional situation. Such analyses have not been conducted before. From the perspective of shaping smart city strategies at the local and regional levels, they are desirable and valuable, providing additional input into the development of the smart city concept.

In this research, quality of life is understood as the subjective perception of city residents, not differentiated into individual aspects, and not measured quantitatively using urban life indicators. Such measurements are present in the literature on the subject. Furthermore, they do not compare the actions of city authorities with the assessment of residents, which is the foundation of the smart city concept.

3.2. Survey Questionnaire

Quality of life was assessed in this research through subjective opinions collected via a questionnaire survey. Several rationales justify the choice of this method. First, such an analysis, when conducted in a representative manner, provides a collective assessment from the most important urban stakeholder: the local community. Second, the literature is dominated by assessments conducted from the perspective of statistics or municipal authorities. Understanding the perspectives of those affected by decisions regarding quality of life is, therefore, crucial for adding objectivity to existing research findings. Third, improving quality of life requires identifying gaps and deficiencies, which only city residents can effectively indicate through anonymous surveys.

The results of the surveys conducted in 19 cities with county rights in the Silesian province, one of the largest provinces in Poland, were used to verify the research hypotheses.

The sample selection in each of the cities surveyed was representative, according to a confidence level of 95%, a fraction size of 0.5, and a maximum error of 10%. With these values, the final sample size included 1863 residents.

The research was conducted in the last quarter of 2024. The questionnaire and research plan were prepared by the author of this article. An agency specializing in public opinion surveys was entrusted with the study’s implementation. The contractor was selected through the university’s public procurement process. One of the key requirements for this process was years of experience in collaboration with research institutions, supported by recommendations from these institutions. The survey was conducted using the CAWI (Computer-Assisted Web Interview) method.

Given the goal of this study, which is to assess residents’ quality of life in the context of their sociodemographic and geographic diversity, a general question related to the assessment of this quality of life holistically was analyzed: How do you rate the quality of life in your city (general perception) on a scale of 0 to 10?

At this stage, the above question was not further refined by analyzing other dimensions of quality of life due to the need to specify sociodemographic characteristics and the diversity of place of residence. These variables were treated as independent variables relative to quality of life, which was the dependent variable.

The rating scale includes 11 points, giving respondents a wide range of options. It is also intuitive and frequently used in satisfaction surveys. Including 0 and 10 in the rating allows for the expression of very extreme opinions. Residents may have such opinions; so, they should be given the opportunity to utilize their full range of choices. Omitting 0 would assume that every resident has positive feelings about their quality of life (1 already evokes positive associations). Moreover, such a scale enables more accurate measurement of the results, including the elimination of rounding errors [99].

To verify the research hypotheses relating to sociodemographic characteristics, the data presented in Table 1 were used.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics of respondents.

To verify the research hypotheses regarding the geographical diversity of cities, data regarding the location of individual cities were used. A list of the surveyed cities, along with a description, is presented in the next subsection.

Examining respondent diversity according to sociodemographic characteristics stems primarily from the need to empirically assess quality of life disparities within the city. Such disparities represent a source of social exclusion that seriously threatens Smart City sustainability. Information regarding the scale and scope of potential exclusion based on age, gender, education, and place of residence yields practical diagnostic insights for Smart City development. These findings are also valuable for municipal decision-making processes.

3.3. Characteristics of the Cities Studied

As previously mentioned, the study covered the entire Silesian Voivodeship region. Currently, there are 19 cities with county rights within their territories. County status is granted to them by the Council of Ministers. These are large cities with aspirations to become smart. They are units of significant regional importance.

These cities were selected for research with two key circumstances in mind. The first is their location in a developing economy. In such economies, the creation of intelligent urban solutions is hindered due to a lower level of economic development. These cities also receive less attention in the literature. In Poland, the creation of smart cities is additionally hampered by the short (twenty-five-year) period of a free-market economy. Meanwhile, flagship smart cities are characteristic of inherently capitalist countries.

The second is their location in the same region. Such a location allows for the simultaneous study of several large neighboring cities aspiring to be smart. This enables comparisons conducted under the same regional conditions. This approach creates a basis for identifying differences in local urban development strategies. Research on this thematic scope with a sample of 19 cities has not been conducted before.

The description of the results was conducted with consideration of two aspects. The first one referred to the relationship between quality of life and the economic conditions of the cities studied (quantitative analysis). The second encompassed the indirect relationships between descriptive characteristics (strengths and weaknesses) of the studied cities and the obtained quality of life assessments.

The quantitative and qualitative characteristics necessary to conduct the analysis in both aspects are presented in Table 2 and Table 3.

Table 2.

Numerical characteristics of the cities studied.

Table 3.

Descriptive characteristics of the cities studied.

Table 2 shows that the population of these cities ranges from 51,000 (Piekary Śląskie) to 277,000 (Katowice, the provincial capital).

Except for Żory, all the cities analyzed are grappling with depopulation. The most severe depopulation is seen in Chorzów, Częstochowa, Jastrzębie-Zdrój, Ruda Śląska, and Sosnowiec. These trends are driven by unfavorable demographic changes across Poland, including declining fertility rates, negative natural increase, and an aging population.

Table 2 also presents the g index, which illustrates the financial situation of the cities studied. This index measures the level of tax revenue (from taxes and local fees) per capita. The data indicate that, in most cities, it ranges between PLN 2000 and PLN 3000. Its value exceeds PLN 4000 in Katowice and Dąbrowa Górnicza due to the high industrialization of these areas. Similarly, in Gliwice, Jaworzno, and Tychy, its value exceeds PLN 3000.

Unemployment, as in Poland as a whole, is quite low. It falls within the creeping unemployment rate, which does not pose a serious economic threat. The highest rates are found in Bytom, Częstochowa, Dąbrowa Górnicza, Piekary Śląskie, and Sosnowiec. Bytom and Piekary Śląskie are also cities with the lowest g index, illustrating their difficult economic situation.

The last column provides the number of residents surveyed. This was determined based on the total number of residents, assuming the parameters indicated above: a fraction of 0.5, a 95% confidence level, and a standard error of 10%. This method established a representative sample size for each city, totaling 1863 respondents.

In addition to the numerical analysis, the surveyed cities were also characterized descriptively. Table 3 presents their strengths and weaknesses. This approach fully reflects their economic and social situation. It is also worth noting that the Silesian province is a traditional mining region that has been struggling with industrial transformation for the past few decades. However, phasing out hard coal mining is not easy, due to Poland’s energy policy and local difficulties in attracting new investors [101,102].

Examining the relationship between place of residence and quality of life enables assessment of how local policy conditions impact urban development and resident satisfaction. This is essential for formulating tailored recommendations for Smart Governance. It also provides a valuable microeconomic perspective on multiple cities functioning within the same region.

3.4. Methods of Analyzing the Survey Data

The data collected is analyzed in three stages:

- Identifying average trends and variability in the quality of life in individual cities, as well as the skewness and concentration of the distribution;

- Determining the relationship between the quality of life and the economic situation of cities;

- Testing the hypotheses regarding the relationship between the quality of life, sociodemographic characteristics of the residents, and city location.

The statistical tools used to complete these stages are presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Research methods used in the analysis of survey results.

All calculations were performed using the Statistica (14.0.0.15) software.

The survey research conducted in this study has several limitations. First, it involves only a selected group of residents and therefore does not reflect the views of the entire local community. Nevertheless, the assumption of sample representativeness enables cautious generalization of the findings. Second, residents’ opinions are inherently subjective, reflecting their individual experience histories. This subjectivity cannot be eliminated. However, the sample size mitigates this limitation by aggregating individual responses to a general level. Third, the survey research is nationally focused. It does not allow for comparison with cities operating in developing economies.

4. Results

The results of the research are presented in three parts. The first part contains information on the assessment of quality of life in cities with county rights in the Silesian Province, as well as on the correlation between economic and demographic parameters and the quality of urban life. The second assesses the hypotheses concerning differences in the quality of life of respondents depending on gender, age, education, and family size. The third part presents the geographical differences in terms of the quality of life.

4.1. Assessment of the Quality of Life in the Surveyed Silesian Cities

As mentioned, the quality of life was assessed on a scale from 0 to 10 in 19 large cities with county rights in the Silesian province. The sample size of 1863 residents guaranteed the representativeness of the research results.

The results of the descriptive statistics for the entire research sample are presented in Table 5.

Table 5.

Descriptive statistics for the quality of life in the city.

The data contained therein show that residents of large Silesian cities live well, as both the mean and the dominant are close to 7. In addition, the median indicates that 50% of respondents rate the quality of life in their city as better than average. Even 25% of the least satisfied give their cities a good rating of 6 (above half of the ten-point scale).

Accordingly, the average quality of life in the Silesian province is not very low, but it does not reach very good or even satisfactory levels. This area is among the most economically developed in Poland [104,105], which may affect residents’ life satisfaction. It is also an area with centuries-old and well-established cultural and industrial (mining) traditions, which enhances the sense of regional belonging and may also positively impact the quality of life.

Nevertheless, the Silesian province is undergoing a post-mining transformation, which raises concerns and has negative economic consequences, such as job losses and reduced incomes [106,107]. These factors may negatively impact residents’ life satisfaction. Significant environmental pollution and mining damage are also problems.

The variation in the ratings is moderate, which means that respondents are relatively rarely more or less satisfied with their living conditions than the average values suggest, although there are people who rate the city very extremely, i.e., 0 (minimum) and 10 (maximum).

The skewness value indicates a distribution that deviates from normal, strongly skewed to the left, which means that although few respondents rated the quality of life in the city very poorly, these low ratings significantly influenced the arithmetic mean. Therefore, the median better reflects the final average quality-of-life assessment in the city.

The kurtosis also indicates similar characteristics of the distribution obtained. According to its value, the distribution is more slender than normal, which means that most of the quality-of-life ratings are concentrated around the mean values. In turn, the tails of the distribution contain extreme values, mainly ratings of 0. This means that there is a group of residents who are extremely dissatisfied with their quality of life.

The measures of variation described above illustrate the considerable heterogeneity of residents’ opinions. This, in turn, complicates the process of delivering public goods and services that simultaneously satisfy all residents. The research indicates that a state of majority satisfaction is possible while concurrent minority dissatisfaction persists.

It is therefore worth considering whether cities can deliver a high quality of life to the entire local community. Alternatively, whether municipal authorities’ efforts should rather be oriented towards the average resident most numerously represented within a given local environment. This question, in a sense, also underscores the utopian character of the Smart City concept’s assumptions in two dimensions. The first pertains to delivering a high quality of life for all. The second emphasizes the egalitarian treatment of all social groups and the absence of exclusion.

The cities studied are in the same region. This allows for the assumption that regional conditions do not significantly differentiate the quality of life. However, economic and social conditions typical of each city may influence it. To verify this, a correlation analysis was conducted between economic-demographic parameters and quality-of-life assessment. The results are presented in Table 6.

Table 6.

Pearson’s correlation coefficient between the economic and demographic parameters of cities and the quality of urban life.

The presented data indicate that the quality of life is positively and significantly correlated with a city’s economic situation, as measured by the g index. This correlation is moderate; however, it illustrates the link between economic prosperity and the assessment of the quality of urban life. It is worth noting that the g index is directly dependent on the city’s industrialization and economic development. This, in turn, impacts its investment and infrastructure capabilities. Therefore, it can be concluded that investors drive urban development, making cities more attractive places to live. Hence, caring for the city’s economy and industry is a crucial task for city authorities.

The conclusions regarding the relationship between quality of life and a city’s economic situation are also supported by the negative, albeit low and statistically insignificant (due to the small number of cities analyzed), correlation between residents’ assessments and the unemployment rate. As the relative number of unemployed people increases, local community life satisfaction decreases.

The above observations imply a rather clear link between the quality of life in cities and their level of economic development. Undoubtedly, material conditions are also a key factor for individual households. The more opportunities a city offers in this regard, the more attractive it is to residents.

The above observations confirm the beneficial impact of economic conditions on the quality of life at both individual and urban levels. It can therefore be assumed that cities with better material status are and will be more predisposed to being smart. This indicates practical inequality in smart city development. It also highlights their commercial character. This serves as yet another argument against the Smart City concept.

4.2. Sociodemographic Differences in the Assessment of Quality of Life in Silesian Cities

The ratings obtained for the entire sample may not accurately reflect the level of satisfaction with life in the city due to its social and geographical diversity. For these reasons, this subsection verifies the first group of research hypotheses relating to the demographic and social characteristics of residents.

Table 7 presents the results of the Mann–Whitney U test for the assessment of urban quality of life by gender. There are statistically significant differences between women and men. Nevertheless, Cohen’s coefficient indicates that these differences are small.

Table 7.

Test statistics for the Mann–Whitney U test: quality-of-life assessment and gender of the respondents.

The descriptive statistics for individual groups show that women rate the urban quality of life slightly lower than men. This confirms hypothesis H1, with the proviso that the differences in assessment are not significant.

The results confirm previous observations about women’s lives in smart cities. Due to the traditional nature of their roles and their weaker economic position, they cannot always fully participate in utilizing the urban infrastructure. In Poland, women are full citizens. However, the patriarchal family model is deeply ingrained in social thought. This may lead to an increased burden of responsibilities and demands, negatively impacting women’s satisfaction with urban life. The identified patterns indicate a risk of women’s exclusion. This risk is not as pronounced and significant as in countries that violate their rights. However, it may intensify over time. This is particularly concerning if the issue is disregarded and amplified by orthodox right-wing perspectives on women’s roles in society.

Contemporary urban characteristics also feature numerous descriptions of senior exclusion. For this reason, the article examined the quality of life in relation to respondents’ age. The results of verifying the second research hypothesis (H2) related to this problem are presented in Table 8.

Table 8.

Test statistics for the Kruskal–Wallis test: quality-of-life assessment and age of respondents.

The data obtained show that there are differences in quality of life due to age, which confirms hypothesis H2. However, they do not indicate a deterioration in the quality of life with age. The quality of life in the city is rated lowest by the youngest residents aged 18 to 40. In subsequent age groups, the assessment systematically improves.

The observed trend may result from several circumstances. Firstly, the study covered cities located in an emerging economy, which 35 years ago was still a centrally planned economy with a very low level of prosperity [108,109]. Therefore, for older generations, the current social and economic situation in Silesian cities is better than the reality of socialist Poland.

Secondly, younger generations are also characterized by a high level of criticism of the surrounding world and significantly higher expectations regarding the quality of life than their parents or grandparents [110,111]. These generations also could observe life in highly developed European economies, which may adversely affect their assessment of the gap between Polish cities and Western European cities [112,113].

Thirdly, the lowest assessment of the quality of life in cities by thirty-year-olds may also be influenced by the significant workload and family responsibilities characteristic of this age group, as well as the poor housing situation in Poland, which complicates the lives of young families (low availability of municipal housing, very high apartment prices, mortgage repayment prospects spanning several decades) [114,115,116].

The results of the study clearly indicate that seniors live well in Silesian cities, and their assessment of the quality of life in the city is more than good. Therefore, it can be concluded that they do not feel excluded. This positive assessment is certainly also influenced by the senior citizen policy in the analyzed region, implemented, for example, as part of the Seniors in the Metropolis (Seniorzy w Metropolii) program [117]. The offer for older people, covering all metropolitan units, includes cultural, sports, tourist, and entertainment events available on preferential terms. The expectations of seniors are also identified and implemented in areas such as transport and space, volunteering, employment and counseling, citizenship, and decision-making. Information on the scope of senior policy can be found in the comprehensive guide “Senior-friendly Metropolis.”

According to the literature review, sometimes exclusion in Smart Cities may also affect people with low levels of education. Intelligent urban structures require advanced technological knowledge and continuous competence development. Therefore, a hypothesis related to this form of exclusion was formulated and verified. The test results for hypothesis H3 are included in Table 8.

The analysis of the data from Table 9 indicates statistically significant differences in the assessment of the urban quality of life depending on the level of education of the respondents, which confirms hypothesis H3. However, this relationship is not linear. The lowest ratings of life in the city are given by residents with a primary education, which is probably related to their limited earning capacity and a more difficult situation in the labor market.

Table 9.

Test statistics for the Kruskal–Wallis test: quality-of-life assessment and the education of respondents.

This observation is consistent with the findings regarding discrimination against the less educated in smart cities. Life in developing cities requires constant learning. In practice, basic education translates into very low skills and employment opportunities. Residents with low levels of knowledge are more likely to hold lower-paid jobs and are less satisfied with their lives. Therefore, without action, it is likely that the quality of life for this group may deteriorate.

However, the low rating of living conditions among people with bachelor’s degrees is particularly interesting. This result is surprising, especially when compared to the relatively high scores given by residents with basic vocational and secondary education. This phenomenon may result from a discrepancy between the expectations of people with a bachelor’s degree and the actual offerings of individual cities, deepening their dissatisfaction. It may also be the result of the very large number of people with higher education in Poland [118] and the shortage of workers in skilled trades, construction, etc. In such a situation, the latter are more needed and appreciated in the labor market, and people with a bachelor’s degree may be depreciated.

In addition, the group of people with vocational and secondary education most likely includes a large proportion of residents working in coal mining (still a key industry for the region), who in the Silesian province constitute a group of workers with above-average incomes [119,120], which certainly affects their satisfaction with urban life.

Material status related to the number of household dependents may also constitute a discriminating characteristic for some residents. Table 10 presents the verification results of the hypothesis (H4) concerning this form of exclusion.

Table 10.

Test statistics for the Kruskal–Wallis test: quality-of-life assessment and number of persons per household.

The data presented in Table 10 show that, in Silesian cities with county rights, there are no statistically significant correlations between the quality of life and the size of households, which provides grounds for rejecting hypothesis H4. Single people have the lowest quality of life, which may be due to the loneliness associated with living alone [121]. However, families with one or two children also do not rate their quality of life very highly. The most satisfied are two-person households, most likely childless couples, and households with five or more people.

These conclusions are consistent with observed demographic trends. The number of childless families in Poland is increasing, which may reduce the number of challenges faced by families with children (e.g., daycare, school, and higher living costs). In turn, large families (more than two children) are often in a much better financial situation than the rest of society, and their decision to have a large family is fully conscious and inspires a sense of meaning and life satisfaction.

To summarize this stage of the research, in Silesian cities with county rights, there are correlations between gender, age, and education and the quality of life of residents. However, no statistically significant correlations were found between household size and quality of life.

4.3. Geographical Differences in Quality-of-Life Assessments in the Silesian Province

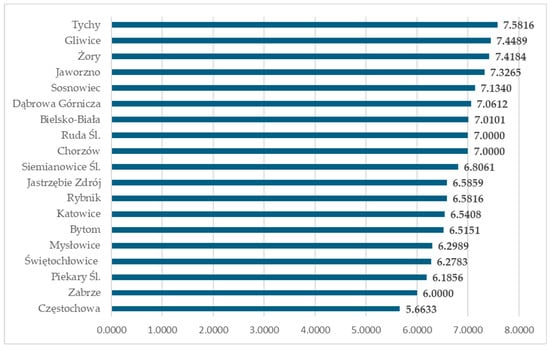

In the second stage of the study, differences in quality of life were assessed geographically, i.e., in relation to individual cities. Detailed data on individual responses are included in Table 11, descriptive statistics are presented in Table 12, and Figure 1 shows the average quality-of-life rating for all respondents.

Table 11.

The frequency of quality-of-life ratings in the cities surveyed (in %).

Table 12.

Descriptive statistics for the cities surveyed.

Figure 1.

Average rating of the quality of life in the surveyed cities.

According to the results presented, the best places to live are Tychy, Gliwice, Żory, Jaworzno, and Sosnowiec. The worst are Piekary Śląskie, Zabrze, and Częstochowa. The gap between the best and worst places is quite significant.

The three cities rated highest in terms of the quality of life by residents are located in the Katowice Special Economic Zone, which is undoubtedly an advantage for investors and translates into employment and income opportunities. These cities have also successfully transformed their industries following the closure of most of their coal mines. In Tychy, Żory, and Gliwice, the automotive industry is developing, mainly producing parts and components for well-known car brands [122].

These cities are also located in the Upper Silesian–Zagłębie Metropolis, not far from each other. They are well-connected and located near the two largest expressways in Poland (A1 and A4). Due to their thriving industries and membership in the economic zone, all of them have a healthy and stable financial situation, as well as a well-functioning labor market. These advantages certainly translate into the satisfaction of residents and their economic well-being.

Importantly, Tychy and Gliwice have a very good economic situation, reflected in low unemployment and a high g index. This confirms the earlier conclusion about the relationship between life satisfaction in the city and its financial situation. This also provides good prospects for the future development of Gliwice and Tychy as smart cities. However, this still implies—as criticized in the literature—the commercial nature of smart cities and the close connection between their development and the need to acquire significant financial capital.

In this context, the case of Żory is different. The economic indicator g is not high; however, residents rate the quality of life very positively. It is also the only city where population growth is observed. This may be due to the lack of inconveniences of living in large cities. Żory is a quiet, relatively sparsely built-up area with plenty of green spaces. This, combined with convenient transportation, proximity, and accessibility to jobs, offers sustainable living conditions. This case proves that being smart does not always equate to being wealthy. Sustainability is equally important and appreciated by residents.

Interestingly, two other cities—Sosnowiec and Jaworzno—do not have similar advantages to the other highly rated cities; however, residents rate the quality of life in these places very highly. Both Sosnowiec and Jaworzno have been struggling with progressive migration and an aging urban population for years [123]. They also failed to fully transform the local industry due to the transition away from coal. Nevertheless, the local finances of both entities are quite healthy and stable.

Sosnowiec seems to be a particularly surprising exception. It is a city with the highest depopulation, an average g-index, and a very high unemployment rate. Despite this, residents still rate the quality of life highly. Perhaps the less-than-ideal conditions are offset by the proximity of highly developed cities and good public transportation. It is also possible that after the out-migration, the city is now mainly inhabited by residents attached to the Zagłębie tradition and their original place of residence.

In Częstochowa, Zabrze, and Piekary Śląskie, both the average quality of life rating and the median are the lowest in the groups surveyed. Zabrze and Piekary Śląskie are post-mining towns where all coal mines have been closed down in recent years. Unfortunately, these towns have not undergone a successful industrial transformation and have replaced mining with other industries [124]. Numerous post-industrial tourism facilities have been built in Zabrze, but they are not as economically profitable as modern commercial enterprises.

Częstochowa is also experiencing economic and social decline. The city, located some distance from Upper Silesia, is mainly developing the logistics and commercial services sector, which does not attract highly qualified staff or investors. The city’s revenues are steadily declining, causing population migration and accelerating the aging of the local community.

All three of the lowest-rated cities are also struggling with the consequences of a poor economic situation. These include, above all, progressive depopulation and the aging of the local community. Another problem is the rising unemployment rate and the resulting difficulties in finding attractive jobs. In Zabrze and Piekary Śląskie, the degradation of post-mining areas is also evident, which discourages investors and deters residents.

Świętochłowice and Mysłowice are also affected by a similar regional situation and are not rated very highly by their residents. The quality of life in these places does not exceed 6.3.

All five cities with the lowest quality-of-life ratings share a difficult economic situation. These cities are characterized by relatively high unemployment rates, a lack of alternatives to the mining industry, and a lack of their own economic base. In the case of Zabrze, Piekary Śląskie, and Świętochłowice, this is reflected in the lowest g indices. In Częstochowa and Mysłowice, this index is slightly higher, but still far from the leader cities.

This indicates that the quality of life in cities with poor financial conditions is strongly determined by their economic potential. Therefore, it can be concluded that the starting point for aspiring to be smart is ensuring good development conditions that positively impact the basic feelings of residents. Only then can additional smart urban solutions be introduced. However, as the case of Żory shows, these do not always have to be commercial solutions related to economic prosperity.

Comparing all the cities, the maximum quality-of-life rating in all the entities surveyed was 10, which means that, among the respondents, there were always people who were extremely satisfied with their place of residence. In the case of the minimum rating (0), no such pattern was observed. The sample included cities where none of the residents gave a score of 0. In this context, Gliwice, where the lowest score was 5, and Jaworzno, with a minimum of 3, should be considered exceptional in terms of quality of life. This confirms earlier conclusions about their attractiveness.

The greatest variation in the quality-of-life ratings was observed in cities where, according to residents, life is worst, i.e., in Częstochowa, Zabrze, and Piekary Śląskie. On the other hand, the residents of Gliwice differed the least in terms of quality-of-life ratings. Therefore, we can conclude that good living conditions are appreciated by everyone. On the other hand, a poor situation may have a particularly negative impact on certain groups of residents who are more susceptible to specific phenomena (e.g., those with lower education levels are more vulnerable to being unemployed).

The above observations suggest that in cities with good living conditions, everyone lives better. However, in cities with poor economic conditions, only some residents experience better living conditions. These cities, therefore, fail to meet the key requirement for smart cities. Consequently, in the studied group, the leaders in quality-of-life assessments, Gliwice, Tychy, and Żory, deserve to be considered cities effectively aspiring to a better life for their local communities and achieving full sustainability. Unfortunately, it will be very difficult for cities at the bottom of the ranking to change the attitudes of their residents, because changing economic and development conditions requires time and consistent action.

All the distributions of the surveyed residents of individual cities were skewed to the left, which means that extremely low values significantly lowered the arithmetic mean, and the actual quality of life in a given city is better illustrated by the median, which was usually 7. Nevertheless, the lowest median (6) still indicates the same group of cities with the lowest ratings (Zabrze, Częstochowa, and Żory), and the highest median continues to identify the same group of cities with the best ratings (Tychy, Żory).

The kurtosis analysis, in turn, indicates the leptokurtic nature of most quality-of-life ratings. Therefore, extreme values may appear more frequently in the obtained results than in a normal distribution. This situation is not present in Chorzów, Gliwice, Jastrzębie-Zdrój, Piekary Śląskie, and Rybnik. For these towns, kurtosis takes positive values, and the distribution is platykurtic.

5. Discussion

5.1. Comparison of the Research Results with Previous Analyses and Observations

The results of the study indicate that there are quite significant differences in the assessment of quality of life due to the sociodemographic characteristics of the inhabitants and the geographical location of cities in the region. Of the five hypotheses put forward, four were positively verified, showing statistically significant differences in terms of gender, age, education, and place of residence. This confirms the previous general observations found in the literature on the subject.

Nevertheless, the direction and scope of the differences identified were not always consistent with the results of previous studies. Thus, for gender differences, a lower quality-of-life assessment among women was confirmed, which poses a certain risk of exclusion for this social group. They are described in the literature on the subject, including [69,70,71,72].

Given the very small differences observed, the risk of exclusion cannot be considered very serious. Polish women are therefore not exposed to such strong exclusion as women in Indonesia; nevertheless, their life satisfaction is not as good as men’s well-being. The differences documented in both studies certainly result from the patriarchal approach to family and women’s place in society. Religion also has a significant impact on the perception of women’s roles, which, although different in Indonesia and Poland, places women lower than men.

The study also found a significant correlation between quality of life and age. However, this did not indicate that seniors are a potential group at risk of exclusion, as previously suggested in analyses by [76,77,78,79,80,81]. Older people (aged 60 and over) rated the quality of life in the Silesian province highest among all age groups. Given the results obtained, young people aged 18 to 40 were the most dissatisfied with life in the city. This pattern may be characteristic of emerging and developing economies, which have undergone significant economic changes over the years. They are appreciated by the older generation because of their previous living conditions. For younger generations, they are probably not yet as advanced as those in highly developed economies.

The above observations do not correspond with the results of earlier research by Li and Woolrych [60,79], which indicates that seniors in Chinese cities are the group most exposed to social exclusion. Seniors in Polish cities assess their quality of life well. Their satisfaction may be influenced by local conditions such as a stabilized lifestyle, living in multigenerational families, or a good economic situation (most are former miners receiving high pensions). Consequently, the assertion about excluding seniors from Smart City life is not universal.

The research results additionally draw attention to the dissatisfaction with life among people of working age. This is quite a new finding. In Poland, young urban residents are most likely not satisfied with objective factors of quality of life, such as housing conditions or income. This illustrates the mutual influence of objective and subjective conditions emphasized within positive psychology. Low quality of life among young people may have serious economic and demographic consequences. Unsatisfactory quality of life may discourage engagement in work or starting a family. In cities of developing economies, it would therefore be necessary to carefully identify and satisfy the expectations of young people. Their life frustration may seriously threaten the lives of future generations.

The analysis also shows that education is related to the quality of life in the city; however, this relationship is not clear-cut and unidirectional. It cannot be said that higher education is accompanied by a higher quality of life, as previous observations might suggest [81,82,83,84,85,86]. In the cities surveyed, the quality of life was rated lowest by people with a bachelor’s degree and highest by people with vocational and secondary education. This correlation may be the result of the progressive depreciation of higher education in the region and the country, and the excessive number of people with such education. It may also result from the growing appreciation for manual workers in the labor market.

In recent years, the labor market in Poland has changed significantly. There is a very high demand for manual workers, e.g., construction workers, mechanics, locksmiths, nurses, hospital orderlies, etc. Residents working in these professions and holding vocational or secondary education therefore have greater opportunities to find well-paid and satisfying work than residents with higher education. The above circumstances affect the objective conditions of quality of life (income, housing conditions). They also cause disappointment among residents with higher education who expect better living conditions due to their higher qualifications. Their frustration, in turn, affects subjective factors of quality of life (generalized sense of happiness).

The study did not confirm any differences in the assessment of quality of life depending on the number of people in the household, although single people were the least satisfied, and large households with more than five people were the most satisfied. This may suggest that social ties play an important role in shaping the quality of urban life, as pointed out in the literature on the subject [36,37,38,39,40].

These conclusions would also be partially consistent with the general assumptions of positive psychology and Amartya Sen’s concept, in which material factors are not the main determinant of quality of life. What is important is fulfilling one’s own expectations and the possibility of freely choosing them. In this context, single people may be satisfied with the conveniences of life, while large families may be satisfied with social bonds. The broader implication of these findings indicates the necessity of leaving residents the choice of developmental opportunities without limiting or imposing them. Freedom of choice may indeed be one of the most important determinants of quality and satisfaction with life. Similar conclusions regarding Brazilian city residents were also reached by Macke et al. [35] based on their research.

Finally, quite significant differences were also found in the assessment of quality of life in the cities of the studied region, which indicates a certain inconsistency in regional policy and a high risk of exclusion of the weakest cities from further development. This applies to post-mining towns (Zabrze, Piekary Śląskie), which have failed to meet the challenges of economic transformation [124]. The measurable effects of the poor quality of life in these towns include depopulation, above-average aging of the local community, and pauperization, as described in the literature [123]. Thus, following Vázquez et al. (2018) [45], it can be clearly emphasized that the government’s assessment of proposals for the development of contemporary cities does not always coincide with the assessment of the local community, which is often much lower.

The above results suggest a departure from generalizing and simplifying the factors that shape the assessment of urban quality of life. They also imply the need for an individualized approach to assessing quality of life in cities, considering specific social groups. Recommendations for urban governance that consider the above observations are included in the next subsection.

5.2. Implications for the Smart City Concept

The key smart city assumption of offering a better quality of life for the entire urban community is not being met in the cities studied. There are groups unable to fully benefit from the benefits of a smart urban structure. Therefore, strong emphasis should be placed on ensuring the satisfaction of all residents, with particular attention paid to the groups at risk of exclusion. This is particularly important for cities aspiring to become smart cities, operating in developing economies, as the initial inequalities may escalate over time. This, in turn, will lead to profound imbalances that preclude smart city status.

It is worth noting, however, that in the cities studied, the exclusion was not always consistent with the trend observed earlier in smart cities. Seniors were not the least dissatisfied group of residents. Those with higher education (Bachelor’s degrees) may experience a lower quality of life. In addition, large families are not always those with lower incomes and poorer well-being. Much, therefore, depends on the specific nature of a given economy, traditions, culture, and regional conditions.

The above observations imply two practical suggestions for the development of sustainable smart cities. First, city authorities need to recognize residents’ expectations without relying solely on intuition and previous conclusions. Second, they need to implement a personalized approach to shaping the quality of life in cities, taking into account the specific characteristics of each local community.

This is crucial, given the significant differences identified in the quality of life across the cities studied. Although the cities operate within the same region, residents clearly distinguish regional conditions from local ones, specific to a given city. They are attached to their place of residence and often critical of the conditions in which they live, but their assessment should serve as guidance for city authorities if they truly aspire to become a smart city.