Social Responses and Change Management Strategies in Smart City Transitions: A Socio-Demographic Perspective

Highlights

- Individuals in the low-income bracket (below AUD 90,000) exhibited emotional distress—including shock, frustration, and depression—primarily driven by fears of job displacement amid smart city transformations. A weak positive correlation was observed between higher educational attainment and openness to digital environments.

- Elderly individuals and females reported significantly higher levels of anxiety and depression compared to other socio-demographic groups in relation to the adoption of smart technologies and transformed urban systems.

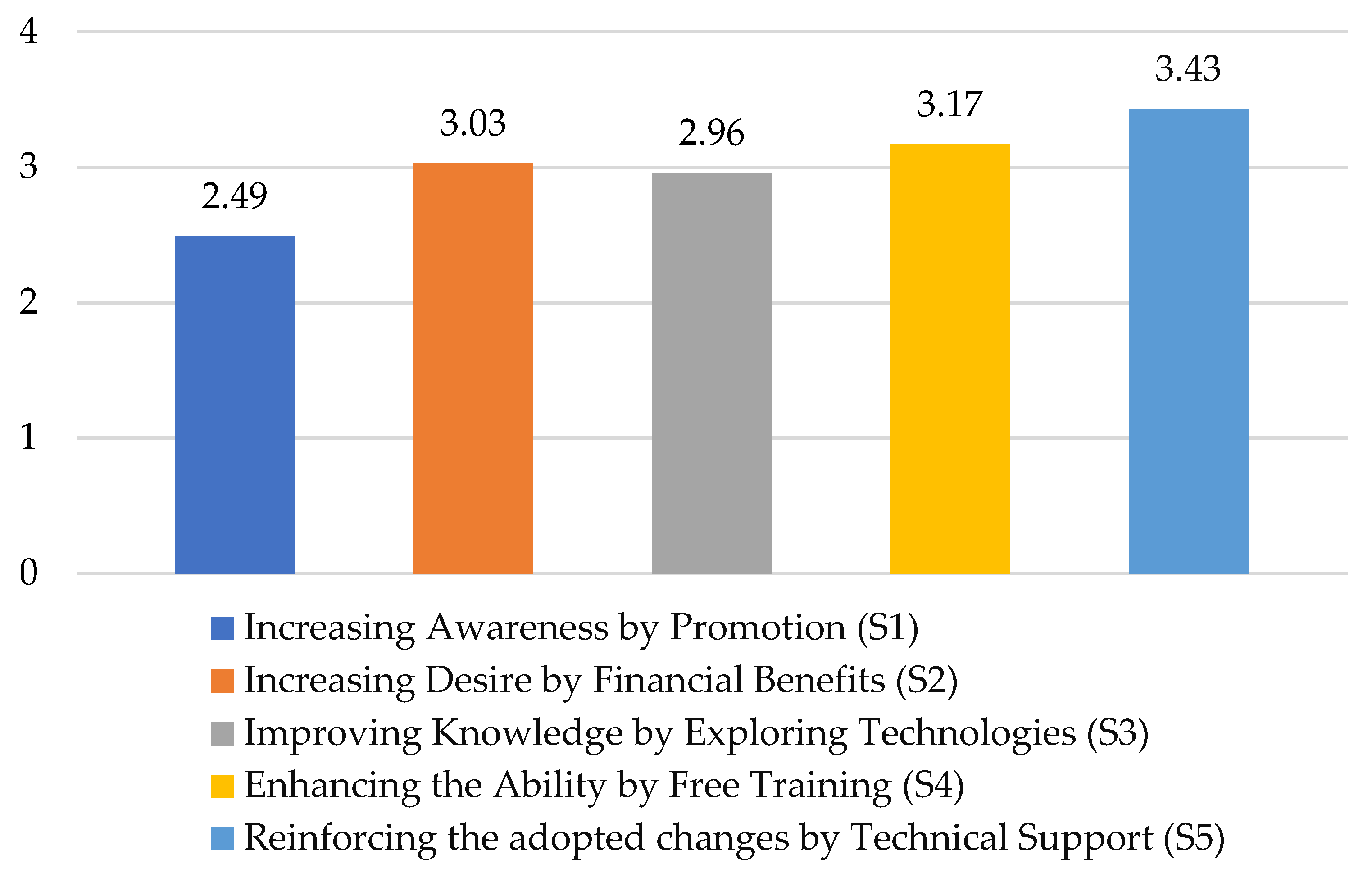

- Free local government-led digital literacy programs and consistent technical support were identified as the most effective change management strategies across socio-demographic groups to reinforce the value of transformed urban environments.

- To ensure a successful smart city transition, local communities and governments must prioritise knowledge enhancement and address the digital divide, particularly in supporting elderly populations and women.

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Q1. How do socio-demographic factors influence individuals’ emotional and behavioural reactions to smart city transitions?

- Q2. How should social change management strategies be tailored to diverse socio-demographic groups to foster acceptance of smart city transitions?

2. Literature Review

2.1. Social Reactions and Attitudes Toward Smart City Transition

2.2. Kübler–Ross Model in Understanding Social Reactions

2.3. Change Management Strategy for Smart City Transition

3. Research Methods

4. Results

4.1. Socio-Demographic Profiles

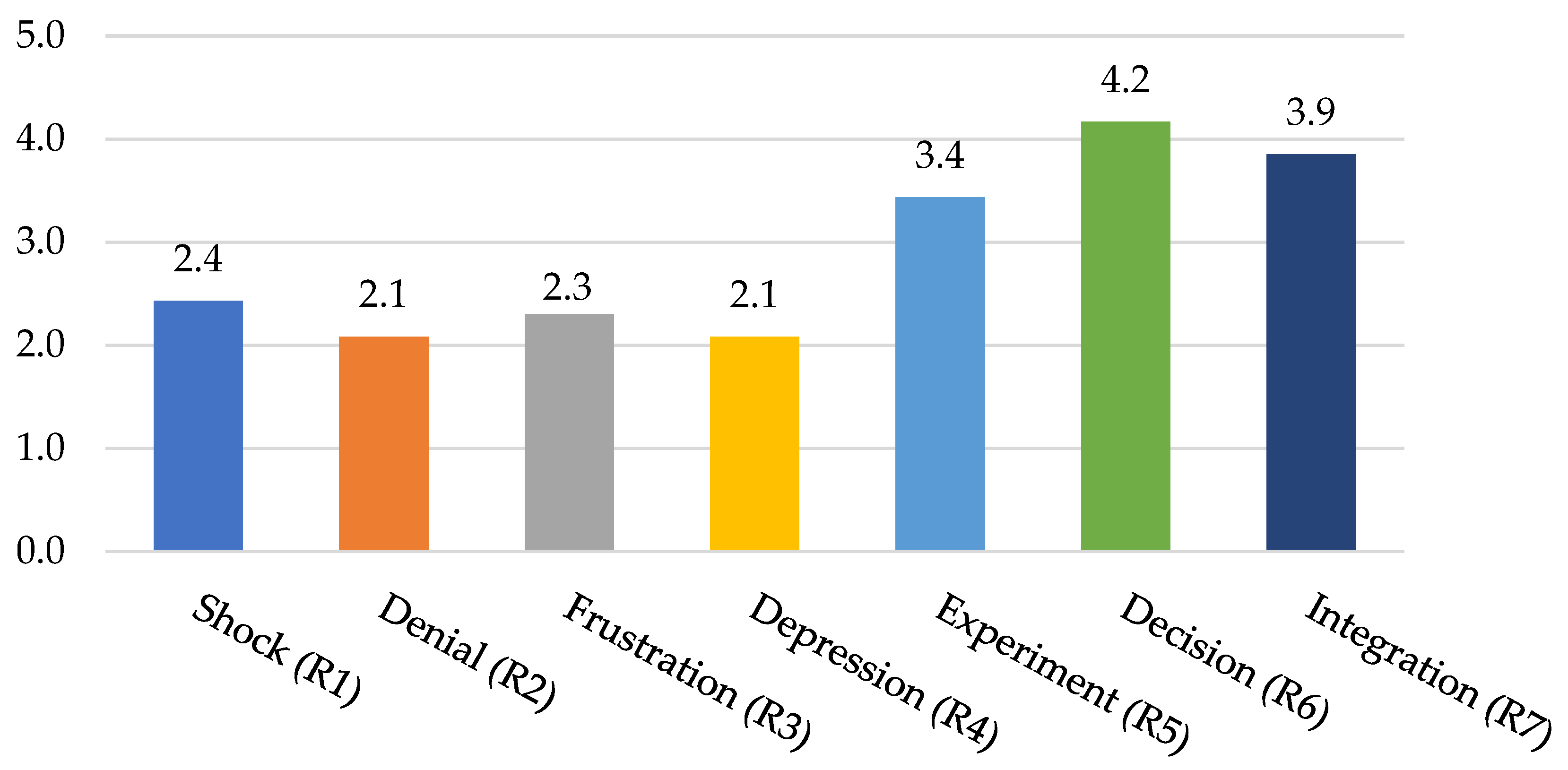

4.2. Social Reactions and Change Management Strategies

4.3. Correlations Between Socio-Demographic Profiles and Social Reactions and Change Management Strategies

4.4. Socio-Demographic Influences on Social Reactions and Change Management Strategies

5. Discussion

5.1. Age

5.2. Academic Degree

5.3. Income Level

5.4. Gender

5.5. Change Management Strategy

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yarashynskaya, A.; Prus, P. Smart Energy for a Smart City: A Review of Polish Urban Development Plans. Energies 2022, 15, 8676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duygan, M.; Fischer, M.; Pärli, R.; Ingold, K. Where do Smart Cities grow? The spatial and socio-economic configurations of smart city development. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2022, 77, 103578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schachtner, C.; Baumann, N. Accompanying study of the development process towards a smart city strategy-with a particular focus on social change. Smart Cities Reg. Dev. J. 2024, 8, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Y.; Yang, J.; Xu, J.; Guan, X.; Zhang, J. High-dimensional urban dynamic patterns perception under the perspective of human activity semantics and spatiotemporal coupling. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2025, 121, 106192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alizadeh, H.; Sharifi, A. Toward a societal smart city: Clarifying the social justice dimension of smart cities. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2023, 95, 104612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarnoff, K.A.; Bostwick, E.D.; Barnes, K.J. Assessment resistance: Using Kubler-Ross to understand and respond. Organ. Manag. J. 2021, 18, 176–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Xing, Z.; Liu, G. Achieving resilient cities using data-driven energy transition: A statistical examination of energy policy effectiveness and community engagement. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2024, 101, 105155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mun Chye, C.; Fahmy-Abdullah, M.; Sufahani, S.F.; Bin Ali, M.K. A study of smart people toward smart cities development. In Proceedings of the Third International Conference on Trends in Computational and Cognitive Engineering: TCCE; Springer: Singapore, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, Y.; Hasanefendic, S.; Bossink, B. A systematic literature review of the smart city transformation process: The role and interaction of stakeholders and technology. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2024, 101, 105112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karmann, J.; Najjar, M.; Ottoni, C.; Shareck, M.; Lord, S.; Winters, M.; Fuller, D.; Kestens, Y. “They didn’t have to build that much”: A qualitative study on the emotional response to urban change in the Montreal context. Emot. Space Soc. 2023, 46, 100937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abebe, R.G.; Bakombo, S.; Konkle, A.T.M. Understanding the Response of Canadians to the COVID-19 Pandemic Using the Kübler-Ross Model: Twitter Data Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 3197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerhardt, T.; Puchkov, R. Preparing for the future: Understanding collective grief through the lens of the Kubler-Ross crisis cycle. High. Educ. Ski. Work.-Based Learn. 2023, 13, 983–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greavu-Serban, V.; Gheorghiu, A.; Ungureanu, C. A multidimensional perspective of digitization in Romanian public institutions. World Dev. 2025, 191, 106996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaklauskas, A.; Bardauskiene, D.; Cerkauskiene, R.; Ubarte, I.; Raslanas, S.; Radvile, E.; Kaklauskaite, U.; Kaklauskiene, L. Emotions analysis in public spaces for urban planning. Land Use Policy 2021, 107, 105458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callaghan, A.; McCombe, G.; Harrold, A.; McMeel, C.; Mills, G.; Moore-Cherry, N.; Cullen, W. The impact of green spaces on mental health in urban settings: A scoping review. J. Ment. Health 2021, 30, 179–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kourtidou, K.; Frangopoulos, Y.; Salepaki, A.; Kourkouridis, D. Digital Inequality and Smart Inclusion: A Socio-Spatial Perspective from the Region of Xanthi, Greece. Smart Cities 2025, 8, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirtz, B.W.; Müller, W.M.; Schmidt, F.W. Digital public services in smart cities–An empirical analysis of lead user preferences. Public Organ. Rev. 2021, 21, 299–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.; Ye, B.; Lin, C.; Wu, Y.J. Can smart city development promote residents’ emotional well-being? Evidence from China. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 116024–116040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, R. Smart Design: Disruption, Crisis, and the Reshaping of Urban Spaces, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2021; pp. 14–30. [Google Scholar]

- Michalik, D.; Kohl, P.; Kummert, A. Smart cities and innovations: Addressing user acceptance with virtual reality and Digital Twin City. IET Smart Cities 2022, 4, 292–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, B.J.; Gordon, S.L.; Struwig, J.; Bohler-Muller, N.; Gastrow, M. Promise or precarity? South African attitudes towards the automation revolution. Dev. South. Afr. 2022, 39, 498–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Twist, A.; Ruijer, E.; Meijer, A. Smart cities & citizen discontent: A systematic review of the literature. Gov. Inf. Q. 2023, 40, 101799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.-Q.; Alamsyah, N. Citizen empowerment and satisfaction with smart city app: Findings from Jakarta. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2022, 174, 121304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lung-Amam, W.; Bierbaum, A.H.; Parks, S.; Knaap, G.J.; Sunderman, G.; Stamm, L. Toward engaged, equitable, and smart communities: Lessons from west Baltimore. Hous. Policy Debate 2021, 31, 93–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirsbinna, A.; Grega, L.; Juenger, M. Assessing Factors Influencing Citizens’ Behavioral Intention towards Smart City Living. Smart Cities 2023, 6, 3093–3111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, E.; Green, M. Making Sense of Change Management: A Complete Guide to the Models, Tools and Techniques of Organizational Change, 2nd ed.; Kogan Page Publishers: London, UK, 2019; pp. 255–308. [Google Scholar]

- Del-Real, C.; Ward, C.; Sartipi, M. What do people want in a smart city? Exploring the stakeholders’ opinions, priorities and perceived barriers in a medium-sized city in the United States. Int. J. Urban Sci. 2023, 27, 50–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahachi, H.A.; Ali, M.A.; Al-Hinkawi, W.S. Urban Change in Cities During the COVID-19 Pandemic: An Analysis of the Nexus of Factors from Around the World, International Symposium: New Metropolitan Perspectives; Springer: Reggio Calabria, Italy, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Dumont, A.; Ruiz, J.; Campeau, S. The Change towards the Integration of Agri-environmental Practices (CIAEP) into farmer’s practices system: An affective, cognitive, and behavioural process. J. Rural. Stud. 2025, 113, 103479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogner, K.; Kump, B.; Beekman, M.; Wittmayer, J. Coping with transition pain: An emotions perspective on phase-outs in sustainability transitions. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2024, 50, 100806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corr, C.A. Elisabeth Kübler-Ross and the five stages model in selected social work textbooks. Illn. Crisis Loss 2022, 30, 320–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barclay, K.; Riddle, J. Urban Emotions and the Making of the City, 1st ed.; Routledge: Oxford, UK, 2021; pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Esteban-Narro, R.; Lo-Iacono-Ferreira, V.G.; Torregrosa-López, J.I. Urban Stakeholders for Sustainable and Smart Cities: An Innovative Identification and Management Methodology. Smart Cities 2025, 8, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shayan, S.; Kim, K.P. Understanding correlations between social risks and sociodemographic factors in smart city development. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2023, 89, 104320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajoudanian, S.; Aboutalebi, H.R. A capability maturity model for smart city process-aware digital transformation. J. Urban Manag. 2025; in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pahuja, N. Partnering with technology firms to train smart city workforces. In Smart Cities Policies and Financing; Vacca, J.R., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; Chapter 12; pp. 169–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almarri, K.; Boussabaine, H. Critical success factors for public–private partnerships in smart city infrastructure projects. Constr. Innov. 2025, 25, 224–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beer, A.; Sotarauta, M.; Bailey, D. Leading change in communities experiencing economic transition: Place leadership, expectations, and industry closure. J. Change Manag. 2023, 23, 32–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pallapu, A.V. Assessment of change management and development; in perspective of sustainable development. Int. J. New Innov. Eng. Technol. 2022, 19, 177–186. [Google Scholar]

- Dopierała-Kalińska, W.; Ossowski, S. Chapter 5. Smart Citizen in Smart City. In Smart Cities and Digital Transformation: Empowering Communities, Limitless Innovation, Sustainable Development and the Next Generation; Miltiadis, D., Lytras, M.D., Housawi, A.A., Alsaywid, B.S., Eds.; Emerald Publishing Limited: Leeds, UK, 2023; pp. 85–103. [Google Scholar]

- Bailey, R.C.; Lumpkin, G. Enacting positive social change: A civic wealth creation stakeholder engagement framework. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2023, 47, 66–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroh, J. Sustain (able) urban (eco) systems: Stakeholder-related success factors in urban innovation projects. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2021, 168, 120767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffioen, D.M.E. Creating the Desire for Change in Higher Education, 1st ed.; Bloomsbury Academic: London, UK, 2022; pp. 21–63. [Google Scholar]

- Balluck, J.; Asturi, E.; Brockman, V. Use of the ADKAR® and CLARC® Change Models to Navigate staffing model changes during the COVID-19 pandemic. Nurse Lead. 2020, 18, 539–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Barachi, M.; Salim, T.A.; Nyadzayo, M.W.; Mathew, S.; Badewi, A.; Amankwah-Amoah, J. The relationship between citizen readiness and the intention to continuously use smart city services: Mediating effects of satisfaction and discomfort. Technol. Soc. 2022, 71, 102115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandt, J.; Batty, M. Smart cities, big data and urban policy: Towards urban analytics for the long run. Cities 2021, 109, 102992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaluarachchi, Y. Implementing data-driven smart city applications for future cities. Smart Cities 2022, 5, 455–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.S.; Masuku, M.B. Sampling techniques & determination of sample size in applied statistics research: An overview. Int. J. Econ. Commer. Manag. 2014, 2, 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. National, State and Territory Population 2023. Available online: https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/population/national-state-and-territory-population/latest-release (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- Liu, Y.; Ji, T.; Ho, H.C.; Guo, C.; Wei, H.H. A decision-making approach for determining strategic priority of sustainable smart city services from citizens’ perspective: A case study of Hong Kong. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2024, 101, 105147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tupasela, A.; Devis Clavijo, J.; Salokannel, M.; Fink, C. Older people and the smart city: Developing inclusive practices to protect and serve a vulnerable population. Internet Policy Rev. 2023, 12, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vojinovic, I.; Panajotovic, T.; Budimirovic, M.; Marija, J.; Dragan, M. User-centric Smart City Services for People with Disabilities and the Elderly: A UN SDG Framework Approach. Economics 2024, 18, 20220103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Shaping Smart Cities of All Sizes, Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development; OECD: Paris, France, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Shayan, S.; Kim, K.P.; Ma, T.; Nguyen, T.H.D. The First Two Decades of Smart City Research from a Risk Perspective. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kummitha, R.K.R. Smart city governance: Assessing modes of active citizen engagement. Reg. Stud. 2025, 59, 2399262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peek, S.T.; Luijkx, K.G.; Rijnaard, M.D.; Nieboer, M.E.; Van Der Voort, C.S.; Aarts, S.; Van Hoof, J.; Vrijhoef, H.J.; Wouters, E.J. Older adults’ reasons for using technology while aging in place. Gerontology 2016, 62, 226–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nam, J.; Kim, S.; Jung, Y. Elderly Users’ Emotional and Behavioral Responses to Self-Service Technology in Fast-Food Restaurants. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN. World Population Day 11 July 2023: As the World’s Population Surpasses 8 Billion, What Are the Implications for Planetary Health and Sustainability? Available online: https://www.un.org/en/un-chronicle/world-population-surpasses-8-billion-what-are-implications-planetary-health-and (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- WHO Decade of Healthy Ageing: Baseline Report, World Health Organization. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240017900 (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- Jobs and Skills Australia. Mature Age Workers and the Labour Market. A REOS Special Report. Australian Government. Available online: https://www.jobsandskills.gov.au/download/19630/mature-age-workers-and-labour-market/2545/mature-age-workers-and-labour-market/pdf (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- IMF Chapter 2: The Rise of the Silver Economy: Global Implications of Population Aging, in World Economic Outlook, a Critical Juncture Amid Policy Shifts, International Monetary Fund. Available online: https://www.elibrary.imf.org/display/book/9798400289583/CH002.xml (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- Treasury. Chapter 6—Overcoming Barriers to Employment and Broadening Opportunities, in Working Future: The Australian Government’s White Paper on Jobs and Opportunities. Australian Government. Available online: https://treasury.gov.au/sites/default/files/2023-09/p2023-447996-08-ch6.pdf (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- Jager, J.; Putnick, D.L.; Bornstein, M.H., II. More than just convenient: The scientific merits of homogeneous convenience samples. Monogr. Soc. Res. Child Dev. 2017, 82, 13–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beştepe, F.; Yildirim, S.Ö. Acceptance of IoT-based and sustainability-oriented smart city services: A mixed methods study. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2022, 80, 103794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO Institute for Lifelong Learning. UNESCO Making Lifelong Learning a Reality: A Handbook; UNESCO Institute for Lifelong Learning: Hamburg, Germany, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirju, I.; Georgescu, R. The Concept of Learning Cities: Supporting Lifelong Learning through the Use of Smart Tools. Smart Cities 2023, 6, 1385–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Babcock, J.; Pham, T.S.; Bui, T.H.; Kang, M. Smart city as a social transition towards inclusive development through technology: A tale of four smart cities. Int. J. Urban Sci. 2023, 27, 75–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Rosa, M.; Glumac, O.; Bianco, V.; Pallonetto, F. A micro-credential approach for life-long learning in the urban renewable energy sector. Renew. Energy 2024, 228, 120660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Guo, Q.; Ren, F.; Wang, L.; Xu, Z. Willingness to pay for self-driving vehicles: Influences of demographic and psychological factors. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2019, 100, 306–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Education. Benefits of Educational Attainment, Australian Government. 2019. Available online: https://www.education.gov.au/integrated-data-research/benefits-educational-attainment (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- AHURI Final Report No. 333: Affordable Housing in Innovation-Led Employment Strategies. Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute, Australia. Available online: https://www.ahuri.edu.au/sites/default/files/migration/documents/AHURI-Final-Report-333-Affordable-housing-in-innovation-led-employment-strategies.pdf (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- Cao, Y.; Hu, Y.; Liu, Q.; Lu, M.; Shan, Y. Job creation or disruption? Unraveling the effects of smart city construction on corporate employment in China. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2023, 195, 122783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, L.; Semirumi, D.T.; Rezaei, R. A thorough examination of smart city applications: Exploring challenges and solutions throughout the life cycle with emphasis on safeguarding citizen privacy. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2023, 98, 104771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Digital Transformation Agency. Digital Inclusion Standard: Supporting Government Agencies to Design and Deliver Inclusive and Accessible Digital Experiences; Version 1.0; Australian Government: Canberra, Australia, 2024.

- Hardley, J. Chapter 6: Gender and smart cities. In Handbook on Gender and Cities, 1st ed.; Peake, L., Datta, A., Adeniyi-Ogunyankin, G., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2024; pp. 65–74. [Google Scholar]

- German, S.; Metternicht, G.; Laffan, S.; Hawken, S. Chapter 9: Intelligent spatial technologies for gender inclusive urban environments in today’s smart cities. In Intelligent Environments, 2nd ed.; Droege, P., Ed.; Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 2023; pp. 285–322. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Saidi, M.; Zaidan, E. Understanding and enabling “communities” within smart cities: A literature review. J. Plan. Lit. 2024, 39, 186–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dashkevych, O.; Portnov, B.A. Does city smartness improve urban environment and reduce income disparity? Evidence from an empirical analysis of major cities worldwide. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2023, 96, 104711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shayan, S.; Kim, K.P. A Conceptual Framework to Manage Social Risks for Smart City Development Programs. In Resilient and Responsible Smart Cities, 2nd ed.; Rodrigues, H., Fukuda, T., Bibri, S.E., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 77–86. [Google Scholar]

- Aldhi, I.F.; Suhariadi, F.; Rahmawati, E.; Supriharyanti, E.; Hardaningtyas, D.; Sugiarti, R.; Abbas, A. Bridging Digital Gaps in Smart City Governance: The Mediating Role of Managerial Digital Readiness and the Moderating Role of Digital Leadership. Smart Cities 2025, 8, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anthopoulos, L.G.; Pourzolfaghar, Z.; Lemmer, K.; Siebenlist, T.; Niehaves, B.; Nikolaou, I. Smart cities as hubs: Connect, collect and control city flows. Cities 2022, 125, 103660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, A. Balancing Privacy and Innovation in Smart Cities and Communities. Available online: https://www2.itif.org/2023-smart-cities-privacy.pdf (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- Lucas, E.; Simpson, S. Perspectives on citizen data privacy in a smart city—An empirical case study. Convergence 2024, 31, 462–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, Y.; Edelenbos, J.; Gianoli, A. What is the impact of smart city development? Empirical evidence from a Smart City Impact Index. Urban Gov. 2024, 4, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manchester City Council. Manchester Digital Strategy 2021–2026; Manchester City Council: Manchester, UK, 2021.

- Barcelona City Council. Digital Talent Overview 2025, Barcelona Digital City; Barcelona City Council: Barcelona, Spain, 2025.

- Local Government Association of South Australia. Smart Cities Framework for Metropolitan Adelaide; Local Government Association of South Australia: Adelaide, Australia, 2019.

| Socio-Demographic Profile | Frequency | Percentage (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 18–24 | 18 | 9 |

| 25–34 | 50 | 25 | |

| 35–44 | 76 | 37 | |

| 45–54 | 24 | 12 | |

| 55–64 | 18 | 9 | |

| 65+ | 17 | 8 | |

| Academic Degree | School (High School) | 20 | 10 |

| Certificate | 20 | 10 | |

| Diploma | 20 | 10 | |

| Bachelor | 80 | 39 | |

| Master/Doctoral | 63 | 31 | |

| Annual Income ($, AUD) | Below 48,000 | 91 | 45 |

| 48,000 to 90,000 | 74 | 36 | |

| 90,000 to 126,000 | 20 | 10 | |

| Above 126,000 | 18 | 9 | |

| Gender | Male | 121 | 59 |

| Female | 82 | 41 | |

| Total | 203 | 100 | |

| Age | Academic Degree | Annual Income | Gender | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Correlation Coefficient/Significance | ||||||||

| R1 | 0.16 | 0.04 | −0.17 | 0.23 | −0.13 | 0.09 | 0.12 | 0.11 |

| R2 | 0.17 | 0.02 | −0.02 | 0.76 | −0.13 | 0.09 | 0.12 | 0.11 |

| R3 | 0.22 | 0.00 | −0.06 | 0.43 | −0.15 | 0.05 | 0.10 | 0.19 |

| R4 | 0.16 | 0.04 | −0.04 | 0.63 | −0.19 | 0.01 | 0.15 | 0.06 |

| R5 | −0.20 | 0.01 | 0.12 | 0.11 | −0.03 | 0.74 | −0.06 | 0.47 |

| R6 | −0.14 | 0.05 | 0.17 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.87 | −0.04 | 0.63 |

| R7 | −0.17 | 0.02 | 0.13 | 0.08 | −0.05 | 0.52 | −0.02 | 0.81 |

| Age | Academic Degree | Annual Income | Gender | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Correlation Coefficient/Significance | ||||||||

| S1 | 0.13 | 0.11 | 0.01 | 0.93 | 0.12 | 0.13 | −0.02 | 0.86 |

| S2 | −0.06 | 0.46 | −0.05 | 0.56 | −0.11 | 0.17 | 0.13 | 0.10 |

| S3 | −0.13 | 0.05 | 0.26 | 0.00 | −0.12 | 0.13 | −0.11 | 0.17 |

| S4 | 0.10 | 0.21 | −0.06 | 0.44 | 0.11 | 0.17 | 0.13 | 0.10 |

| S5 | −0.02 | 0.82 | −0.12 | 0.14 | 0.02 | 0.78 | 0.07 | 0.39 |

| Age | Academic Degree | Annual Income | Gender | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P.C. | L.R. | P.C. | L.R. | P.C. | L.R. | P.C. | L.R. | |

| Relationships with Social Reactions | ||||||||

| Value | 57.02 | 58.96 | 15.77 | 15.95 | 22.71 | 21.80 | 12.39 | 12.69 |

| df (Degree of Freedom) | 20 | 20 | 16 | 16 | 12 | 12 | 4 | 4 |

| Asymptotic Significance | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.47 | 0.46 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.03 |

| Relationships with Change Management Strategies | ||||||||

| Value | 88.34 | 90.18 | 21.13 | 22.15 | 41.30 | 36.48 | 20.85 | 21.03 |

| df | 20 | 20 | 16 | 16 | 12 | 12 | 4 | 4 |

| Asymptotic Significance | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.17 | 0.14 | 0.02 | 0.01 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| R1 | R2 | R3 | R4 | R5 | R6 | R7 | S1 | S2 | S3 | S4 | S5 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | KW H | 11.82 | 14.37 | 24.07 | 12.25 | 28.60 | 26.78 | 17.02 | 9.82 | 1.37 | 6.43 | 4.44 | 0.54 |

| df | 5.00 | 5.00 | 5.00 | 5.00 | 5.00 | 5.00 | 5.00 | 5.00 | 5.00 | 5.00 | 5.00 | 5.00 | |

| 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.08 | 0.93 | 0.27 | 0.49 | 0.99 | ||

| Degree | KW H | 8.33 | 6.35 | 7.41 | 5.46 | 7.34 | 9.05 | 5.04 | 2.35 | 2.58 | 14.62 | 1.12 | 2.46 |

| df | 4.00 | 4.00 | 4.00 | 4.00 | 4.00 | 4.00 | 4.00 | 4.00 | 4.00 | 4.00 | 4.00 | 4.00 | |

| 0.08 | 0.17 | 0.12 | 0.24 | 0.12 | 0.06 | 0.28 | 0.67 | 0.63 | 0.01 | 0.89 | 0.65 | ||

| Annual Income | KW H | 8.78 | 4.93 | 8.83 | 9.70 | 0.91 | 3.42 | 1.61 | 2.53 | 3.50 | 2.76 | 2.05 | 1.35 |

| df | 3.00 | 3.00 | 3.00 | 3.00 | 3.00 | 3.00 | 3.00 | 3.00 | 3.00 | 3.00 | 3.00 | 3.00 | |

| 0.03 | 0.18 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.82 | 0.33 | 0.66 | 0.47 | 0.32 | 0.43 | 0.56 | 0.72 | ||

| Gender | MW U | 2998.5 | 3013.5 | 3045.5 | 2833.5 | 3093.5 | 3318.5 | 3343.5 | 2974.0 | 2538.5 | 2695.5 | 2567.5 | 2770.5 |

| 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.10 | 0.03 | 0.11 | 0.41 | 0.49 | 0.99 | 0.10 | 0.17 | 0.09 | 0.37 | ||

| Mean Rank (Male) | 81.79 | 81.93 | 82.23 | 80.23 | 91.32 | 89.19 | 88.96 | 96.00 | 95.00 | 98.00 | 98.00 | 99.00 | |

| Mean Rank (Female) | 95.25 | 95.02 | 94.54 | 96.57 | 80.17 | 83.53 | 83.90 | 62.00 | 63.00 | 63.00 | 62.00 | 61.00 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shayan, S.; Kim, K.P. Social Responses and Change Management Strategies in Smart City Transitions: A Socio-Demographic Perspective. Smart Cities 2025, 8, 188. https://doi.org/10.3390/smartcities8060188

Shayan S, Kim KP. Social Responses and Change Management Strategies in Smart City Transitions: A Socio-Demographic Perspective. Smart Cities. 2025; 8(6):188. https://doi.org/10.3390/smartcities8060188

Chicago/Turabian StyleShayan, Shadi, and Ki Pyung Kim. 2025. "Social Responses and Change Management Strategies in Smart City Transitions: A Socio-Demographic Perspective" Smart Cities 8, no. 6: 188. https://doi.org/10.3390/smartcities8060188

APA StyleShayan, S., & Kim, K. P. (2025). Social Responses and Change Management Strategies in Smart City Transitions: A Socio-Demographic Perspective. Smart Cities, 8(6), 188. https://doi.org/10.3390/smartcities8060188