Highlights

What are the main findings?

- A semantic link network model for representing logistics transport transactions and states.

- A semantic link with state representation for supporting data security and logistics traceability.

- A location mapping mechanism for ensuring logistics traceability.

What is the implication of the main finding?

- The semantic link network model is expressive and extensible in modelling complex systems and dynamic semantics.

- The semantic link network model is capable of modelling and implementing decentralized and distributed applications.

Abstract

Logistics transports of various resources such as production materials, foods, and products support the operation of smart cities. The ability to trace the states of logistics transports requires an efficient storage and retrieval of the states of logistics transports and locations of logistics objects. However, the restriction of sharing states and locations of logistics objects across organizations makes it hard to deploy a centralized database for supporting traceability in a cross-organization logistics system. This paper proposes a semantic data model on Blockchain to represent a logistics process based on the Semantic Link Network model, where each semantic link represents a logistics transport of a logistics object between two organizations. A state representation model is designed to represent the states of a logistics transport with semantic links. It enables the locations of logistics objects to be derived from the link states. A mapping from the semantic links into the blockchain transactions is designed to enable the schema of semantic links and the states of semantic links to be published in blockchain transactions. To improve the efficiency of tracing a path of semantic links on a blockchain platform, an algorithm is designed to build shortcuts along the path of semantic links to enable a query on the path of a logistics object to reach the target in logarithmic steps on the blockchain platform. A reward–penalty policy is designed to allow participants to confirm the states of links on the blockchain. Analysis and simulation demonstrate the flexibility, effectiveness, and efficiency of the Semantic Link Network on immutable blockchain for implementing logistics traceability.

1. Introduction

Smart cities enhance the quality and efficiency of urban public services through ICT systems that integrate communication and computing technologies [1]. Modern smart logistics undertakes green, efficient, and secure transport of goods within and between smart cities, supporting the operations of smart cities. Security, privacy protection, and efficient collaboration between organizations are challenges to logistics in smart cities. The traceability of a logistics system is the ability to trace the states of logistics transports and the locations of logistics objects being transferred through the logistics transports of a logistics process. Ensuring the traceability of the logistics process helps improve customers’ informedness, especially in cross-border supply chains in smart cities.

To support traceability, a database for recording the states of logistics transports and the locations of logistics objects is necessary. Due to the restrictions of sharing transport states and locations of logistics objects among different organizations, centralized databases are often unsuitable as it is hard to meet the requirements of data privacy protection of different regions. A distributed and decentralized data management solution is desired to implement logistics traceability in a distributed, decentralized, and secure platform where logistics data can be published and traced with less centralized management. Blockchain is a promising decentralized data management model that can be used to publish logistics data in a decentralized way [2,3]. It can be used to implement decentralized and secure information-sharing applications of smart cities [4].

Smart contract enables developers to construct and deploy distributed and decentralized data management services on Blockchain platforms to implement logistics transport data publishing and querying services [5]. However, deploying logistics data on smart contract services faces the following problems:

(1) Publishing on-chain data in smart contracts is expensive, and the immutability property of Blockchain data makes it difficult to implement data management with complex semantics [6]. Implementing logistics traceability requires recording and keeping updated on the states of logistics transports. It needs a data model over immutable blockchain transactions to support data updating and tracing on the blockchain. Logistics management rules implemented in a smart contract may need to be updated during transport and should be promptly reflected in the logistics tracing process. But rewriting smart contracts is costly. The hash pointers underlying blockchain transactions can be revised to allow for updates [7], but it will break the traceability of transactions. Verification and representation of logistics rules can be implemented separately in different smart contracts, which can partially reduce re-deployments of smart contracts [8]. But, any update made to logistics management rules will still require updating smart contracts that implement the logistics rules, which can result in a loss of traceability because it has to add new smart contracts for new logistics rules.

(2) Tracing logistics processes in decentralized data requires visiting and confirming a large number of blockchain transactions that record logistics process states, which is also costly. Various storage indexing structures, such as the Patricia tree, have been developed to improve the efficiency of querying a single transaction in the local storage of computing nodes on a blockchain platform. However, it still lacks an indexing structure over the blockchain transactions to enable fast tracing along a chain of blockchain transactions.

To meet the two challenges, this paper proposes a semantic link network data model to store logistics data with a schema in blockchain transactions to represent logistic process states on a Blockchain platform. A logistics process tracing can be implemented by tracing states stored in blockchain transactions. The state updating schema is implemented in the semantic link network model and is stored with the logistics state within a blockchain transaction so that the rules of logistics states can be dynamically updated during a logistics process. States of a logistics transport can be traced and confirmed by following blockchain transactions on Blockchain, which ensures the security and traceability. A shortcut link publishing algorithm is designed to record the states of a logistics transport path, which can significantly improve the tracing process by following shortcut links. A penalty-reward policy is designed to encourage the two participants to quickly finish the confirmation of the logistics transport states in a decentralized way.

The solution based on Semantic Link Network (in short SLN) model has the following advantages:

(1) The SLN is such a flexible and extensible graph-based semantic representation model that can represent logistics transports by semantic links published on blockchain transactions [9]. It has a schema with a graph structure to define reasoning rules among links. In the model, a logistics process can be represented by a semantic link network where nodes represent the parties and semantic links between two nodes represent logistics transports between two parties. Each logistics object in the logistics process is uniquely represented by a binary string ID. The schema of SLN instances specifies rules for determining legal transitions between link states. A semantic link between two nodes is attached by a logistics object ID to represent one logistics transport of the logistics object between two parties. The logistics transport path corresponds to a path of links that transfer the same logistics object from one node at the beginning of the path to the node at the end of the path. Each semantic link is published in one blockchain transaction together with its schema to enable decentralized tracing on the Blockchain. It can be deployed as a blockchain platform without using a smart contract to manage logistics data.

(2) A state model of link is designed to represent the states of logistics transports in the logistics process. Locations of logistics objects can be derived from the semantic link states. An algorithm can be designed to publish semantic links with different states in blockchain transactions by treating the logistics objects as virtual assets of blockchain transactions. The state updating can be implemented by publishing semantic links with different states in blockchain transactions. The schema can also be published in blockchain transactions to support the verification of state transitions. The traceability can be implemented by tracing semantic links published in blockchain transactions.

(3) Shortcut links can be added to improve the query efficiency of the path of links for obtaining the state of logistics transports on a logistics transport path. Shortcut links are added in a probabilistic way so that different numbers of added links can achieve different speed-ups of the tracing process.

2. Related Work

2.1. Logistics Traceability

A logistics process consists of multiple parties and transports of logistics objects among parties, which requires a graph-like data model [10] to represent and record the whole logistics process for implementing traceability. The main issue is to record the states of logistics transport and locations of logistics objects, and the updating of the logistics states and locations in a database. In the traditional supply chain management, business process models such as state transition diagrams with data flow charts can be used to represent the logistics process [11]. Logic operators are used in data flow charts to represent combinations of outputs from process nodes, and the state transitions and data flows are further stored in relational databases by transforming the business process model to a database schema [12]. When modelling the cross-border logistics, centralized databases are not suitable for recording logistics state due to the restriction of sharing data flow and states among different organizations from different nations [13]. Blockchain techniques provide an alternative solution to implement logistics traceability and enhance privacy protection in a decentralized platform where no centralized authority is required, but it also faces many challenges in deployment of adaptability [14].

2.2. Blockchain Technique

Blockchain is a distributed digital wallet system that records each transaction of transferring an encrypted digital bitcoin from one account to another account in a decentralized way without leveraging a central authority management service [15]. On a blockchain platform, each account owns a public–private key pair that is used to encrypt, sign, and validate transactions of the owned bitcoins to other accounts. A bitcoin is a virtual currency that can be split into smaller pieces of virtual currency. Bitcoins are issued when a hash ID satisfying a hard constraint is mined. Every participant can issue a bitcoin if they can mine out such an ID. The hardness of mining a hash ID ensures that the increase of virtual currency is controllable. A blockchain transaction is a transference of a bitcoin from the payer account to the payee account, which is recorded in a data structure consisting of the transferred bitcoin number, the hash ID of the previous transaction that transferred the bitcoin to current payer account (as a pointer to connect transactions to a list) and the public key of the payee account. The transaction is encrypted by the public key of the payee account so that only the payee account can decrypt it with its private key. The transaction data structure is signed by the payer to enable the payee to verify the signature to ensure the ownership of the bitcoin of payer. By following the pointers of the hash IDs of blockchain transactions, one can verify the bitcoin and trace back to the first transaction that issued the original bitcoin.

Blockchain transactions are broadcast to all hosts and are stored in the latest block of the longest blockchain in the local computing device of each host within the blockchain network. Each host keeps mining a hash ID for the current longest chain. The first mined out hash ID (proof-of-work) for the latest block is used as the pointer to connect the latest block to the longest block chain, and a new block is prepared to accept the following new transactions. The blockchain transactions that are validated in the longest chain of blocks are accepted as legal transactions, which can avoid the double-spend on the blockchain platform because only the longest blockchain is accepted by all hosts. The hardness of computing a proof-of-work prevents malicious hosts from altering the blocks in the accepted longest blockchain. Thus, transactions on blockchain are immutable.

The transactions starting from the root account of a bitcoin form a tree path from the root of the tree to a leaf node, which records the path of the bitcoin transferred from the root to the leaf node and can be traced back by verifying the signature of each block transaction on the path. Smart contract techniques are extended to enable the development of various decentralized applications on blockchain by publishing services in a block so that any blockchain transaction can access the customized services of blockchain transaction management [5]. Smart contract encapsulates executable procedures in a blockchain transaction such that the procedures can be executed on the data published in the transaction. Smart contracts are published on all peers and become immutable. The encapsulated procedure is protected and can be verified for authentication of the execution results on the data, which provides an extensible way to implement various computing services on data published in transactions [16].

A blockchain platform needs to reach consensus on the longest blockchain among all hosts, which could take a long time [17] and incur a high computation cost. Although blockchain databases have been receiving more and more attention, the research focus is still mainly on the consensus and scalability issues [18], as there is still much time cost to reach consensus on blockchain transactions, which can greatly decrease the performance of publishing transactions and retrieval in blockchain databases [17]. Alternative solutions of consensus schema, such as Proof-of-Stake, Proof-of-Authority, and PBFT (Practical Byzantine Fault Tolerance) have been proposed to allow transactions to be verified and synchronized in an efficient and decentralized way, without requiring to mine qualified hash IDs by powerful computing devices [19,20]. Permissioned blockchain platforms have been developed for developing blockchain applications in controlled network environments where only authorized participants can join [2], and most efforts are focused on confidentiality, verifiability, and performance across blockchains [21]. Blockchain databases such as BigchainDB [3] provide enabling frameworks for developing blockchain applications without caring much about the underlying implementations of the blockchain transaction publishing, synchronization, and verification. One of the major differences between the blockchain database and traditional databases is that the blockchain database is immutable and lacks data model schemas that can support ACID-compliant transactions [22]. Updating already published data in blockchain transactions should be indirectly realized by replacing the update with appending new data published in new blockchain transactions.

2.3. Implementing Logistics Traceability on Blockchain

- (1)

- Data storage

Distributed ledgers on blockchain are used as distributed storage shared by participants in a supply chain, where participants can update information published on the shared ledgers that are synchronized and managed in smart contracts on blockchain [23]. A multi-blockchain framework has been proposed to enable different logistics business organizations to join in and share their blockchain transactions on multiple blockchains according to a hierarchical key distribution mechanism [24]. However, the framework does not address the logistics state representation problem. Traceability tags are used to record and verify the owners of products. It does not support logistics transport path trace as the logistics transport state updating is not considered in the framework.

Supply chain and logistics management can be implemented on the blockchain database BigchainDB, where products and goods are treated as virtual assets that are published in blockchain transactions in BigchainDB [25]. However, the state updating issue is not addressed.

The immutability of blockchain presents challenges when implementing a complex data management model that requires the recording and updating of logistics states and locations [6]. A suitable middle data model is required as a bridge between the immutable blockchain transactions and application transactions to help developer compose applications based on a middle data model [26], rather than directly on the raw blockchain transaction data structures, which can ease the extension and compatibility of applications and reduce the development cost and prompt adoption of blockchain techniques [13]. Such kind of data models in previous supply chain management research have been studied in a centralized database [27]. However, the immutability and decentralization of blockchain pose new challenges for developing a data model that requires recording and updating of logistics states and locations.

- (2)

- Implementation of logistics rules

To implement logistics traceability, it is necessary to verify the conditions that trigger legal transport according to specific rules for controlling the logistics process under different conditions and events, and to log transport states while indicating the next legal states and actions, which can be implemented by if-then rules in smart contracts [28]. Business Process Management Notation (BPMN) scripts were used to program complex workflow conditions and are published in smart contracts to facilitate the checking of conditions for each action in a supply chain, which helps implement traceability on blockchain [29]. However, when the logistics rules are frequently updated through a logistics process, it can be costly to re-write BPMN scripts and re-deploy updated BPMN scripts in new smart contracts, which will also break the traceability. Implementing the rule interpreter of BPMN and scripts of BPMN separately in different smart contracts can reduce the cost of updating smart contracts, as the rule interpreter can remain unchanged [8]. However, it is still inevitable to update logistics rules in a logistics process, as logistics management rules in a supply chain often change. This requires handling of new logistics rules in a timely manner for executing logistics processes. Implementing tracing services in multiple abstraction layers can improve the system’s adaptability and extensibility [30], but it often requires off-chain services to implement application-level services, which can break the decentralization of blockchain and traceability.

One possible solution for managing updates of both logistics rules and logistics transport states is to publish them with blockchain transactions. This allows for easy updating by appending new transactions to the blockchain. To achieve this, a schema for representing logistics rules and a data model for representing logistics transport states on the blockchain are required. The semantic link network is a suitable candidate graph-like semantic model consisting of semantic nodes, semantic links, a schema of reasoning rules, and a semantic space where the semantics of nodes and links are defined to represent concepts, instances, and relationships among them. It supports both centralized applications and decentralized applications (e.g., on peer-to-peer networks) with an interactive semantics [31]. Its nodes can be in different spaces to model cyber-physical-social systems [32]. It has been applied to improve e-learning and text summarization [9,33]. Graph tools have been used to model logistics systems [34]. Directed Acyclic Graph (DAG)-based immutable databases provide a more efficient distributed data publishing and tracing service by allowing multiple confirmations of transactions maintained by multiple participants [35]. However, it still has less compatibility and extensibility to support complex semantic representation of data on blockchain. The semantics link network model has the capability of representing different link types, which can act as a middle data model to describe the logistics transport relationships between two parties in a logistics process. The link structure can be mapped into a blockchain transaction to support publishing logistics transport, which eases its application in representing logistics transports on blockchain. The schema defines semantic links and reasoning rules on semantic links of different types, which can also be published as blockchain transactions. A semantic link schema can represent logistics rules on the blockchain. Any update to the logistics rules can be implemented by appending a new schema on the blockchain. However, it cannot directly record the state of logistics transports by a semantic link that is published in a blockchain transaction. An extension on SLN is required for representing both the logistics transport state and locations of logistics objects, allowing state updates to be published and queried on blockchain to implement traceability.

- (3)

- Trace efficiency

It is still time-consuming when the tracing process requires confirmations by participants of the logistics process along the path of links to ensure the consistency between the published state of links and the state of real logistics transports. The decentralization of the blockchain platform enables tracing to be conducted in a concurrent way, like how a decentralized query is concurrently processed in a classic P2P network [36].

A distributed algorithm has been proposed to accelerate blockchain tracing by executing a parallel tracing process among two nodes when the topology of blockchain transactions is a directed graph [37]. However, the blockchain transactions are chained to form a list, and only sequential accesses are supported.

Shortcuts can be added among nodes in structured ring P2P networks to improve the query performance to a logarithmic scale [38].

- (4)

- State confirmation

The confirmation of consistency can be conducted concurrently by following shortcuts appended on the blockchain list to speed up the whole confirmation process along the semantic link path. Each confirmation can be verified only by the direct participants in the logistics transport. It should be conducted in a controlled way such that malicious actions can be avoided. As there is no centralized server responsible for the consistency management, a decentralized policy is required to ensure that the participants to publish links consistent with the real logistics transport states. On the blockchain platform, PoW (Proof-of-Work) takes too much computing cost to reach consensus among blocks and cannot be applied to support publishing semantic links for logistics traceability. PoS (Proof-of-Stake) and PBFT [20] cannot be directly applied to two participants to confirm a link state. An encrypted schema is used to encrypt traceability tags for anti-counterfeit [24], but it does not consider the confirmation problem by participants. A safety checking function is implemented on smart contracts to let the users of contracts denote the safety problem of the contracts [39], but it does not support arguments of the consensus on the blockchain transactions. A penalty is given to those account that performs misoperations, and the penalty is stored in the blockchain for checking [40], but it does not consider how to reach a consensus on one transaction. A reward–penalty schema is designed to handle the bifurcation problem of blockchain transaction release in PoS based blockchain platform [19]. The main concern for PoS is to ensure a consensus on the blocks for storing blockchain transactions published by users. A reward and penalty scheme can be designed based on the consensus status of parties to encourage nodes to reach consensus as quickly as possible [41]. However, the logistics transport can be confirmed only by the related participants of the transport. Thus, when implementing logistics traceability on a blockchain platform, it needs a consistence management schema for confirming the consistency of published links with the real transport by the participants.

3. Logistics Transport Semantic Link Network Model for Supporting Traceability

3.1. Basic Framework

A logistics process consists of a series of logistics transports that deliver logistics objects from their source locations to target locations, where logistics objects include the parcel to be transported and the related documents such as contracts, transport licenses, trade certifications, and custom clearance application forms that are necessary for customs clearance across borders. To record each logistics transport for supporting traceability, we use the semantic link network model [31] to represent a logistics transport by a semantic link with a logistics object ID to represent a logistics transport. Then, a semantic link is published in a blockchain transaction on a blockchain platform by the source participants of the logistics transport, which can be confirmed by the receiver using the blockchain transaction confirmation mechanism on the blockchain platform. A logistics process can be traced by following the chain of blockchain transactions on the platform.

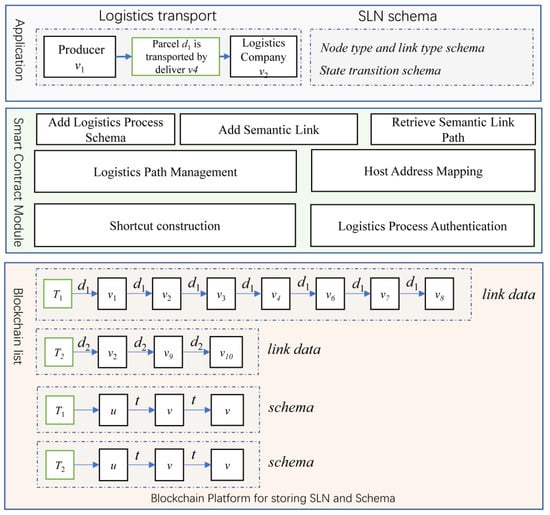

Figure 1 shows the framework of publishing links on a blockchain platform to support tracing logistics transports. The application layer provides the user interface for inputting and querying the transport states and locations of logistics objects. The middle layer is based on the smart contract technique to implement link publishing, querying and validating, and confirmation on the blockchain. The host address mapping module is used to determine the blockchain transaction account when publishing a link. The logistics process authentication module is used to release authentication to the legal access to the blockchain platform. The shortcut construction module is used to improve the efficiency of tracing the path of links by building shortcut links among nodes in the SLN. The bottom layer is the blockchain platform, such as BigchainDB [3], that is used to store and access SLN data and schema by using the logistics object IDs as virtual assets of transactions.

Figure 1.

The framework for implementing the proposed model.

3.2. Semantic Link Network Model for Logistics Transport

A semantic link network consists of a set of semantic links [31]. A semantic link takes the following form: <v1: a—γ→v2: b>, where γ is a predefined link type, v1 is an instance of a semantic node of type a, v2 is an instance of another semantic node of type b. <v1—γ→v2> is a simplified format of a semantic link by omitting the type of nodes. The schema defines the legal types of the link and the node of semantic links in the form of [a—γ→b], which defines that a link with the starting node of type a, the link of type γ, and the target node of type b is a legal link. The reasoning rules on semantic links are also defined in the schema. For example, the reasoning rule {α·β⇒γ} defines that a link of type α adjoined to a link of type β implies a link of type γ, where α, β, and γ are link types [9] and the operator “·” indicates the adjacency of two links.

A logistics transport semantic link (link) uses a directed semantic link with a logistics object ID to represent the transport of a logistics object (such as a parcel or a document) from the source party to the target party in a logistics process. A set of links forms a logistics-transport Semantic Link Network of the logistics process.

Definition 1.

A logistics transport Semantic Link Network (SLN) is defined as: G = <V, D, E>, where:

- V is the set of unique IDs of the nodes of the network.

- D = {d1, d2, …, dn} is the set of logistics object IDs.

- E = {vi—<l, d>→vj | vi, vj∈V, d∈D} is the set of logistics transport semantic links (links) where vi—<l, d>→vj is a semantic link from node vi to vj attached by a logistics object ID d and l is the data structure that consists of the unique ID of the link, the link type, the link state and the attached data of the logistics transport including the cost of the transport, the time constraints and other user-defined data structures for the logistics transport.

A logistics process is represented by an SLN, where each party in the logistics process is uniquely represented by one node ID in V. The logistics object IDs are used to uniquely identify the parcels and the necessary documents to be transported. A link vi—<l, d>→vj represents a logistics transport l that delivers a logistics object d from the starting node vi to the target node vj in l.

3.3. Location Representation of a Logistics Object

The nodes and links in an SLN are used to represent the locations of a logistics object in a logistics process. That is, in a SLN G = <V, D, E>, S = V∪E is the location space of logistics objects in D [3]. A movement of a logistics object d from one location to another location is through a link vi—<l, d>→vj, either from vi to the link l, or from the link l to node vj, or from vi to the End location. A logistics object d can be at one of three possible locations of a link vi—<l, d>→vj: the starting node vi, the target node vj, and the link l. When d is at the node vi, the logistics object is at the starting node, and the transport is not started yet. When d is at the link l, it means that the logistics object is in the transport process. When d is at the node vj, the logistics object is at the target party, and the transport is completed. When all transports of d are completed, d is at the End location and no more transports of d are required.

A logistics object d is transported from its starting location to a target location through a path of n logistics transports, which corresponds to a link path L(d) = {v1—<l1, d>→v2, v2—<l2, d>→v3, …, vn−1—<ln, d>→vn}. As a logistics object d is transported through a path of semantic links, its locations are represented by d(1), d(2), …, and d(n), where d(n) is the latest location of d.

3.4. State Representation Model of Semantic Link

A logistics transport has multiple states indicating the status of the transport. For example, the initialized state indicates that the transport is to be started, the transporting state indicates that the transport is ongoing and the parcel is the path from the source to the destination, the succeeded state indicates that the transport is successfully completed, the failed state indicates that the transport is failed and the End state indicates that the whole transport is terminated and the parcel will not be transported further. One transport can be started only after its predecessor transport is successfully completed. States of logistics transports should be traced. Simply storing one logistics transport in one semantic link cannot reflect the state of a logistics transport. A state model is required to represent the logistics transport states in a logistics process.

A link has five states: Init, Transporting, Succeeded, Failed, and End to represent states of one logistics transport: the initial state, the transporting state, the state of successful completion, the failure state, and the end of the logistics transport. Definition 2 defines the way to determine the state of a link according to the transport of the logistics object.

Definition 2.

The state process of a link l∈E is a set of indexed states Pc(l) = {l(j) | j∈I = {1…n}} where l(j): I→{Init, Succeeded, Failed, Transporting, End} is the jth state of the link l.

- In the state l(j) = Init, the logistics object d of l is going to move from vi to vk;

- In the state l(j) = Transporting, the logistics object d of l is being transported through l from vi to vk but the transport is still not completed;

- In the state l(j) = Succeeded, the logistics object d of l is successfully moved from vi to vk;

- In the state l(j) = Failed, a logistics object d of l failed to move from vi to vk.

- In the state l(j) = End, a logistics object d of l halts.

More states can be added according to application requirements. According to Definition 2, the location of a logistics object can be determined by inference rules.

Definition 3.

Location and state inference rules specify the implication relations (denoted as “⇒“) between the states of a link vk—<l, d>→ vj and the location of the logistics object d, where l(n) denotes the current state of the link l and d(n) denotes the latest location of d at l:

- l(n) = Init⇒ d(n) =vk;

- l(n) = Transporting⇒ l(n − 1) = Init | Transporting, d(n − 1) = vk | l and d(n) = l;

- l(n) = Succeeded⇒ l(n − 1) = Transporting, d(n − 1) = l and d(n) = vj;

- l(n) = End⇒ l(n − 1) = Init | Succeeded | Failed, d(n) = End, and d(n + 1) = End;

- l(n) = Failed ⇒ l(n − 1) = Init | Transporting and d(n) = vj.

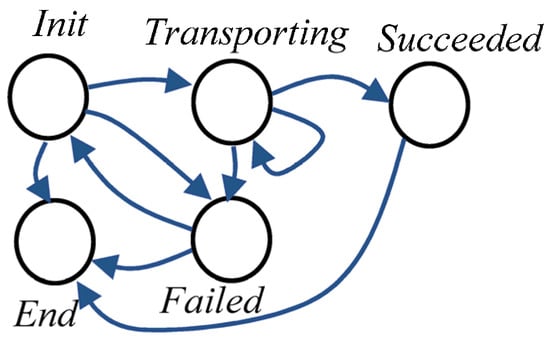

According to the inference rules in Definition 3, the legal transitions of link states from the current state to the next state are shown in a schema. Figure 2 illustrates the state transition graph corresponding to the schema. When the state of a transport is in state Failed, the object ID is transferred to the payee. This is because when a transport is confirmed to be Failed, both the payer and payee should accept that state.

Figure 2.

Link state transition schema.

3.5. Schema of Semantic Link State Transition

The schema of semantic links defines the legal transition of states of links.

Definition 4.

The schema of the state transition of a semantic link regulates the legal transitions as follows.

- Init→ Transporting | Failed | End;

- Transporting→ Transporting | Succeeded | Failed;

- Failed→ Init | End;

- Succeeded→ End.

In the schema, l(n) = s ⇒ l(n + 1) = t1 | t2|…| tk indicates that if the current state is s, then the following state can be one of t1, t2, …, and tk. The schema can be extended according to the increased states. According to Definition 3, each state of a link has exactly one corresponding object location, and the object location can be derived from the states of links. Thus, the platform designed according to the model only needs to publish and record links, and their states on the blockchain.

To ensure correct state transition, the semantic link network schema rules are used to define the transition schema such that the consistency of state transitions can be verified. Specifically, the semantic link network schema defines the implication rules between two links that share one node. The state transition links are used to define those implication rules among links such that only those links that can be reasoned out are legal transitions.

A schema rule of SLN is defined in the following form:

<u, l, v> and <w, t, e> ⇒ <u, r, e>, where u, v, w, and e represent any node in SLN, and l, t, and r represent three types of link. The schema indicates that if there are two links of type l and t connecting nodes from u to v and from w to e, then they imply a link of type r from u to e.

A SLN schema defines a reasoning rule that can be used to derive new links from the existing links according to the link types. The state transition schema of logistics semantic links can be modeled by treating the state of a link as a type of link. Then, a link in different states can be treated as a set of links with different types.

A semantic link schema <u, s, d, v> of SLN matches a link vi—<l, d>→vj with l(n) = s, where s∈{Init, Succeeded, Failed, Transporting, End}.

A state transition l(n) = s ⇒ l(n + 1) = t is represented by a semantic link reasoning schema <u, s, d, v>⇒<u, t, d, v>. Then, a state transition schema l(n) = s ⇒ l(n + 1) = t1|t2| … |tk is represented by a semantic link reasoning schema:

<u, s, d, v> ⇒ <u, t1, d, v> | <u, t2, d, v> | … | <u, tk, d, v>.

The schema for describing the state transition between two different links can be defined as:

<u, s, d, v> ⇒ <v, t, d, w>.

For example, <u, Succeeded, d, v> ⇒ <v, Init, d, w> indicates that only when a semantic link for transferring d from u to v is succeeded, the next link can be started.

The reasoning procedure for checking the consistency of the state transition between two links is to check if there is a rule that matches the states of the two links. For the state reachability checking, the transitive closure of the state transition graph is obtained and is used to check if two states are reachable according to the state transition schema.

Each state transition should adhere to the schema. The schema rules are published in a set of blockchain transactions from the root node T. The starting state of a rule represents the payer account, and the next state represents the payee account, allowing one to obtain the schema rules by inputting the starting state. A new schema rule can be published to replace an existing schema by appending it to a blockchain transaction that follows the existing schema rule. This ensures that the latest schema rule is always held in the last blockchain transaction.

4. Publishing and Tracing Links on Blockchain

4.1. Mapping Semantic Link to a Blockchain Transaction

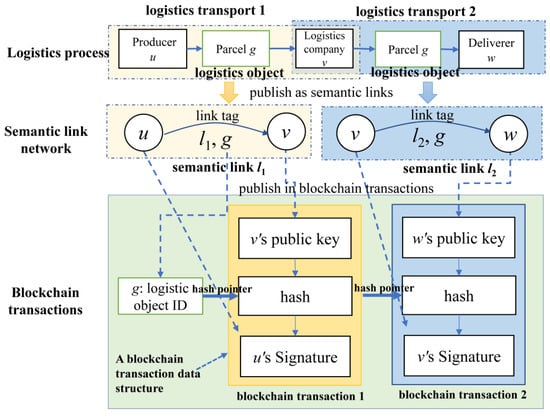

A link is published as a blockchain transaction on a blockchain platform to implement the decentralized traceability of logistics transports by tracing published links for the transport of a logistics object. A mapping from a link to a blockchain transaction is required to determine the payer and the payee account of the blockchain transaction for storing the link, according to the state of the link, as the state updating is realized by publishing new blockchain transactions. On a public blockchain platform, transactions can be verified and processed only by its owners. After a new transaction is correctly produced and published by its owner on a server, it will be broadcast to all servers for verification and acceptance. The authentication is ensured by the transactions’ signatures produced by the previous transaction (see Figure 3). That is, only the owner of the signature can correctly manipulate a transaction. Usually, a client-side system is provided with user account and password management to allow users to manage their own transactions. On a blockchain platform, the first transaction is made for a newly produced bitcoin by the client software to transfer the bitcoin to its first owner (i.e., the miner). In our proposed system, the first transaction is made by the payer who owns the logistics object ID and makes the first logistics transport requirement by transferring the logistics object to the next payee through a logistics process, which is recorded on a semantic link with states in a transaction. The authentication is similar to the original blockchain that uses the signature of the payee to ensure the correct manipulation of a logistics transaction with a semantic link.

Figure 3.

Two logistics transports are published as two blockchain transactions on a blockchain transaction list.

To represent logistics objects, a logistics transport semantic link (link) vi—<l, d>→vj is used for representing a logistics transport that delivers the logistics object d from vi to vj, where d is the logistics object ID, l indicates the link ID, vi represents the starting party of the logistics transport and vj represents the target party of the logistics transport. Then, the semantic links are published in blockchain transactions for implementing traceability.

Figure 3 shows an example consisting of two logistics transports in a logistics process. The first transport transfers the parcel g from the producer u to the logistics company v, and the second logistics transport transfers g from v to the deliverer w (a transport company). The two logistics transports are represented by two semantic links l1, and l2. Then, the two semantic links are published in two blockchain transactions to record the corresponding logistics transports. The starting node of the link is mapped into the payer account of the blockchain transaction, and the ending node of the link is mapped into the payee account of the block transaction.

The logistics object ID is treated as a virtual asset ID of the blockchain transactions. One logistics transport is recorded in one blockchain transaction. Two blockchain transactions are connected by the hash pointer of the previous one that transfers the same logistics object ID, which forms a blockchain list that can be used to trace the logistics transports. The hash function in the first transaction block (in yellow color) is to take the payee’s public key ID (v) and the object ID to be transferred as inputs to produce a signature that can be decoded correctly by only the receiver’s private key. Then, the first transaction block can be linked to the second transaction block by inputting its hash digest and the public key of the second payee w to the hash function to produce the second signature in the second block, which ensures that only payee w can decode the second block. This chain of transactions ensures that only the receiver can verify the current transaction and make the next transaction. The traceability can be conducted on each transaction on the chain by the transaction’s owner.

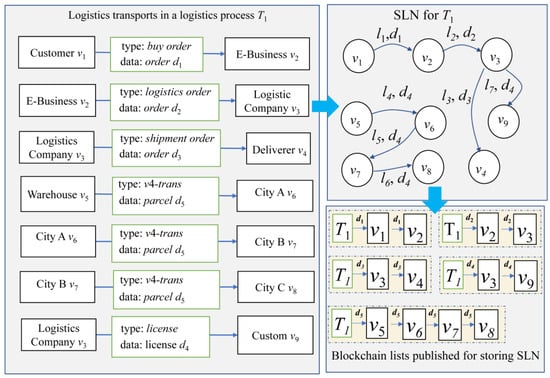

Figure 4 shows an example of an SLN that records a logistics process L. The left-hand side lists 7 logistics transports in L. The first transport starts from the customer v1 with the e-business platform v2 for transferring the purchase order from v1 to v2. The type of the first transport is place_order, which indicates that the platform receives an order from a customer. The logistics object d1 represents the order from the customer v1 to the platform v2. After receiving the order, the e-business platform v2 issues an order of shipment d2 to the logistics company v3 for the second transport. Then, v3 issues a shipment order d3 to the deliverer v4, which fetches the parcel d4 from the warehouse v5 in the fourth transport and transports it to city A, city B, and city C in the following three transports. The logistics company v3 also transfers an application document d5 to the customs department v9 for customs clearance. The logistics transports are mapped into a set of links to form an SLN shown in the upper part of the right-hand side. For example, the first transport is represented by a link v1—<l1, d1>→v2, where v1 is the customer ID, v2 represents is e-business platform ID, l1 consists of the ID, the type and other attributes of the logistics transport to be recorded such as the costs of transport, the deadline and the constraints, and d1 is the logistics object ID that represents the electronic contract document sent from v1 to v2. Semantic links are published in blockchain transactions by using the logistics object ID as the virtual asset ID to be transferred in a blockchain transaction. All the logistics objects are issued by a root account that represents the whole logistics process (T1 in Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Example of SLN on a blockchain.

As shown in the right-hand bottom part of Figure 4, five blockchain lists are constructed, each having the logistics process ID T1 as the root account. The first blockchain list corresponds to the transport of a purchase order from v1 to v2, where the logistics object d1 is the purchase order. The first arrow is the blockchain transaction transferring d1 from the root account of T1 to v1. Then, the second blockchain transaction represents the transference of d1 from v1 to v2, which represents the link v1—<l1, d1>→v2 of the first logistics transport. The transport of the logistics object d2 is recorded in the second blockchain list, where the link v2—<l2, d2>→v3 is published in a blockchain transaction from v2 to v3. Similarly, the logistics transports of d5 form a blockchain list with three blockchain transactions to represent three links: v5—<l4, d4>→v6, v6—<l5, d4>→v7, and v7—<l6, d4>→v8. Note that all blockchain lists start from the root account T1, which provides a unique access point for obtaining links in the logistics process T1.

4.2. Publishing States of Link on Blockchain

Let a tuple B = <a, c, b, e> be a blockchain transaction that is published and stored on the blockchain platform to record a transference of a bitcoin value c from the payer account a to the payee account b with e being extra tags of the type, time, and other attribute values of the transaction such as the transaction time. According to the authentication mechanism of blockchain, when the block transaction B is published on the blockchain, it is the host (the people who own the account) of the payee account b which obtains the authorization (owning the encryption private key of the blockchain transaction B) to access and encrypt the block transaction B. That is, the host of the account b becomes the current host of the bitcoin c and can make a next transaction to transfer c to another account by applying the private key of b to sign the transaction.

4.2.1. Mapping States of Semantic Link to Blockchain Transaction

A link u—<l, d>→v can be published in a blockchain transaction B = <a, c, b, e> by mapping u to a, d to c, v to b and l(n) to e. The bitcoin c of the blockchain transaction is replaced by the logistics object ID d, the starting node u is the payer account, the target node v corresponds to the payee account of the blockchain transaction, and the state of l is stored in e. To access the block transaction B for obtaining the link u—<l, d>→v, one needs to obtain the authorization from the host of the payee account b, which ensures the protection of published links.

The states of a link is published in new blockchain transactions. The location of the logistics object of a link can be used to determine the mapping from the link to a block transaction according to the states of the link.

Definition 5.

A link u—<l, d>→v is published in a blockchain transaction B = <u, d, H(l, d(n)), l(n)> where u is the payer account, the bitcoin is replaced by the logistics object ID d, l(n) is the stored link state, and H(l, d(n)) is the mapping determines the payee account of the blockchain transaction that holds the link according to the location of the logistics object d(n):

- H(l, d(n)) = u if d(n) = u;

- H(l, d(n)) = u if d(n) = l;

- H(l, d(n)) = v if d(n) = v; and,

- H(l, d(n)) = H(l, d(n − 1)) if d(n) = End,

which means that the Ending state is published in the host same as the host of its previous link.

When publishing a link in a blockchain transaction, the starting node of the link is used as the payer account of the blockchain transaction. The payee account is determined by the location of the logistics object. When the payee account is the same as payer account, the host of the payer account publishes a blockchain transaction to itself. When the logistics object is moved to the End location, it will not move further. The host of the blockchain transaction for the previous link will be responsible for publishing the last link that has the End as the target location.

Before publishing a link u—<l, d>→v for the first logistics transport in a logistics process T, a root account is created by using the logistics process ID T as a root account ID on the blockchain platform. Then, a blockchain transaction B0 = <T, d, u, Succeeded> is published to transfer d from the root account T to the account u. The first blockchain transaction does not store any link. It has a default state of Succeeded. It ensures that links of logistics transports in one logistics process are stored in blockchain lists with the same starting root account T. Thus, accesses to links of the same logistics process T start from the same root account T on the blockchain platform. Logistics transports in different logistics processes are published in different blockchain lists. After the first blockchain transaction from the root account T is published, the blockchain transaction B1 = <u, d, H(l, d(n)), l(n)> is published to store the link u—<l, d>→v according to the current link state l(n) and the location d(n) of d. The following links will be appended to the last block transaction, which forms a blockchain list for representing a transport path of the logistics object. Each payer account of a link is the payee account of its previous link, which can ensure the correctness of the published sequence of links in the blockchain list when multiple links are published simultaneously.

4.2.2. Publishing Multiple Blockchain Transactions for One Logistics Object

The original blockchain platform does not allow double pay of one bitcoin. However, a logistics object d can be transported to multiple target nodes from the same starting node, which requires publishing multiple links that have the same payer account, the same logistics object, but different payee accounts. For example, an application form document is sent to different departments for verification. To skip the double pay restriction of the blockchain platform, we use a suffix naming strategy to allow a logistics object d to be published in multiple blockchain transactions from one payer account to multiple payee accounts. Assuming a logistics object d at node u is transferred to k target nodes in k links: u—<l1, d>→v1, u—<l2, d>→v2, …, u—<lk, d>→vk, then k blockchain transactions are published for B1 = <u, d.v1, v1, l1(n)>, B1 = <u, d.v2, v2, l2(n)>, …, Bk<u, d.vk, vk, lk(n)>, where the ith blockchain transaction Bi = <u, d.vi, vi, li(n)> uses the d.vi as the logistics object ID to be transferred in the blockchain transaction from u to vi. When a logistics object ID with suffix is transferred in a blockchain transaction that has the same payer account and payee account, the payee account ID is appended to the suffix ID of the logistics object so that two links that are published in two blockchain transactions with the same payer and payee account will have different logistics object IDs.

For example, assuming two links u—<l1, d>→v1 and u—<l1, d>→v2 are published with l1(1) = Init and l2(1) = Init, two blockchain transactions are published: B1 = <u, d.v1, u, l1(1)> is published for l1, and B2 = <u, d.v2, u, l2(1)> is published for l2. When the states of l1 and l2 are updated to Transporting, B3 = <u, d.v1, u, l1(2)> and B4 = <u, d.v2, u, l2(2)> are published. Appending the target node ID as the suffix to the logistics object ID of the blockchain transactions can avoid the double pay problem. Each time a logistics object d is transferred in a new link, the target node ID is appended as a suffix to the current logistics object ID in the blockchain transaction.

In this way, the suffix of a logistics object d is extended as d is transferred through a link path, which records the sequence of the nodes that the logistics object d has been transported through. For example, d.v1.v2…..vk represents that the logistics object d has been transferred through nodes v1, v2, …, and vk in a sequence of links, where v1, v2, …, and vk are the target nodes of the link. The suffix of a logistics object ID can be used as a record of the logistics transport path that the logistics object has gone through. Tracing the process of a logistics object path starts from T and follows the published links to verify each link until reaching the end of the path. Shortcuts from the current node to a remote node on the path can be added to improve the efficiency of the tracing process.

4.2.3. Procedure of Publishing a Blockchain Transaction

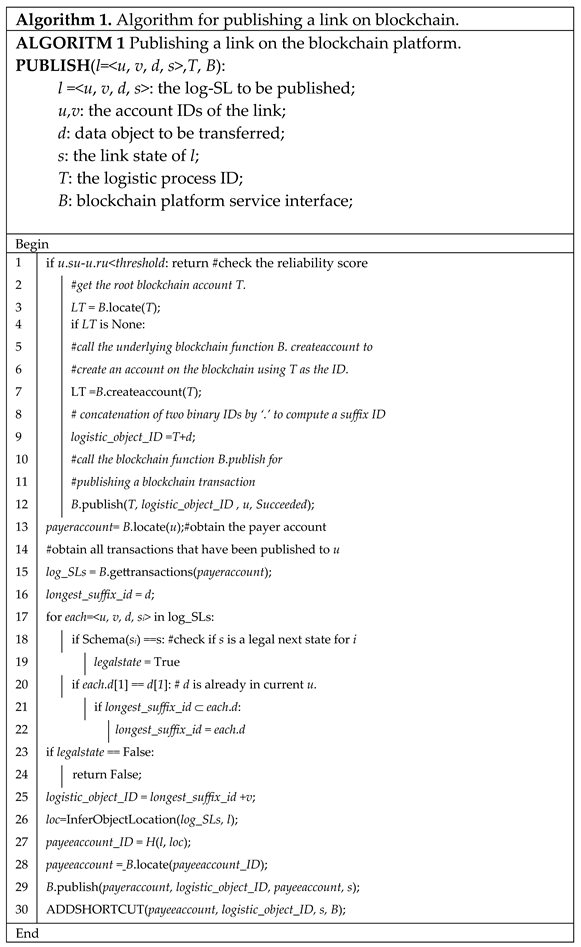

The algorithm for publishing a link on the blockchain platform is shown in Algorithm 1. The input arguments include the link l, the logistics process ID T, and the blockchain platform service B. First, the reliability score is computed to check if the account u is allowed to publish a new link according to a penalty–reward policy defined in Section 5.3, where u.su and u.ru are the trustiness score and the responsibility score of u. Then, the root account T of the logistics process is located (line 3). If there is no such logistics process, the root account T is created, and the first blockchain transaction from T to u with logistics object d is published on the blockchain (line 4 to line 12). The payer account is located for u and all links that have been published from the payer account u are obtained in line 15. Then, the longest suffix ID of the logistics object d is obtained from line 16 to line 22, and the new suffix ID of d is built by appending the ending node ID v to the longest suffix ID in line 24. In this way, the logistics object d will be published with the longest suffix ID that records the path of the transport of d and the longest suffix ID will be used to add shortcut links in ADDSHORTCUT in line 29. After the suffix ID is obtained, the location loc of d is obtained by the function InferObjectLocation through the state of the link l in line 25, the payee account is located by the function H(l, loc) according to the rules in Definition 5 in line 26. Finally, the blockchain transaction is published in line 28 from the payer account of u to the payee account of v using the suffix ID. When checking each existing link, Schema(si) is called in line 18 to verify if the current link to be published is a legal next state of an existing link. Schema(si) loads the Blockchain transactions from the root node T with starting account si to determine if s is its next states. If s is not a legal next state, the publishing is halted in line 23.

|

The implementation of Algorithm 1 depends on the underlying blockchain platform to provide blockchain transaction publishing services listed in Table 1 for supporting blockchain account creation and blockchain transaction publishing and retrieval.

Table 1.

Functions provided by blockchain for publishing links as blockchain transactions.

One can obtain the starting blockchain transactions of logistics objects by accessing the root account T of the logistics process and then obtain links in the following blockchain transactions by tracing along the block chain lists starting from T. Thus, it assumes that the users who can start a logistics process should have account T and can access account T with the corresponding private key on the blockchain. The tracing process can be realized by following the hash pointers back to the payer account and using the public key of the payer account to verify the signature of the blockchain transaction. However, if one needs to check the detailed semantic link data with the real record of the logistics transport, they need the payee account to decrypt the blockchain transaction and obtain the semantic link data structure. Due to the lack of a centralized server, one must get authorization from the host of the payee account of each blockchain transaction to access the links and verify the semantic link and the corresponding logistics transport, which could take time.

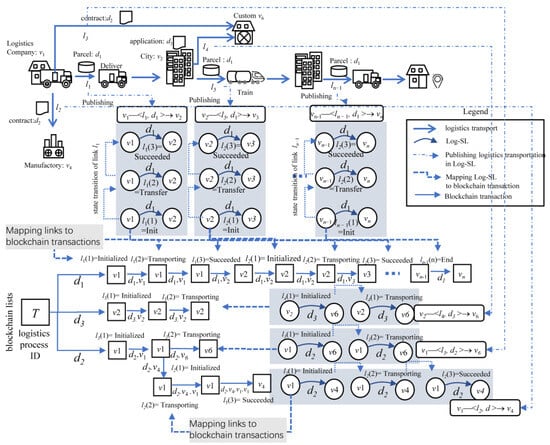

4.2.4. Scenario of Publishing Semantic Links on Blockchain

Figure 5 shows an example case of a logistics transport process, and the states recorded in semantic links and published in blockchain transactions. The upper part of Figure 5 shows a logistics process consisting of manufacturer, the logistics company, custom department, the transport tools, and the target. The logistics process is represented by a set of semantic links in the middle of Figure 5. A blockchain list T consists of blockchain transactions storing semantic links and states, which is started by a logistics company v1. Three logistics transports are started from v1: l1 sends a parcel d1 via a delivery, l2 sends an application document d2 from v2 to the customs department v6, l3 sends a contract document d3 to the manufactory v4, and l4 sends the same contract d3 to the customs department v6. Those transports are represented by semantic links stored in blockchain transactions.

Figure 5.

Logistics process published on blockchain lists.

The first logistics transport l1 for transporting a parcel d1 is represented by a link v1—<l1, d1>→v2. The first state of l1 is Init. According to Definition 5, the payee account is still v1, thus the first blockchain transaction B1 = <v1, d1, v1, l1(1)> is published to store v1—<l1, d1>→v2 with l1(1) = Init. After the state of l1 is updated to Transporting, v1 is used again as the payee account and the block transactions B2 = <v1, d1, v1, l1(2)> is published to record l1 with l1(2) being Transporting. When publishing l1 with l1(3) being Succeeded, v2 becomes the payee account and the blockchain transaction from v1 to v2 is published as B3 = <v1, d1, v2, l1(3)>. After l1 is completed with the Succeeded state, the next transport from v2 to v3 is started. The link v2—<l2, d1>→v3 is published for recording the transport of d1 from v2 to v3. The first state of l2 is the Init state, and a blockchain transaction B4 = <v2, d1, v2, l2(1)> is published to store the link and its current state. Then, the next two states of l2 are published in two blockchain transactions B5 = <v2, d1, v2, l2(2)> and B6 = <v2, d1, v3, l2(3)>. Finally, the blockchain transactions for storing the links that transfer d1 from a blockchain list.

The logistics object d2 represents the application form transferred from v2 to the national customs office v6 for customs clearance. The first two states of the link l3 are published in two blockchain transactions from v1 to v1, which form the blockchain list starting from d2.

The logistics transport l3 and l4 correspond to the transport of the contract represented by d2 from v1 to the manufacturer v4 and from v2 to the customs office v6, respectively. They are recorded in two links. The branch in the blockchain list represents that the logistics object d2 has multiple targets. The suffix naming schema is applied to give the logistics object d2 two different IDs d2.v4 and d2.v6, when publishing the two links from v1 to v6 and v7.

4.3. Traceability of Semantic Links on Blockchain

After publishing links in blockchain transactions, tracing logistics transports can be implemented by collecting the states of links of the logistics transports published on blockchain platform. Different levels of traceability can be supported with different costs for collecting states of links published for recording logistics transports.

(1) Transport state traceability. Checking the current state of a logistics transport requires to obtain a link and check its latest state by locating the blockchain transaction published for recording the latest state of the link. For example, checking if a logistics transport of a parcel to a customer is Succeeded or Failed can be implemented by finding the link that has the target node being the customer and checking whether the link state is Succeeded. This can be implemented by locating the payee account of the blockchain transaction that holds the link and obtaining the links that has been published by the payee account.

(2) Path state traceability. Checking the states of a set of logistics transports that a logistics object has transported through. A link path corresponds to such a set of logistics transports published in blockchain transaction in one blockchain list. Implementing the path state traceability requires to obtain the sequence of links and their corresponding states, which needs to obtain all blockchain transactions in a blockchain list from the root account of the logistics process.

(3) Logistics process traceability. This requires obtaining all blockchain lists that are published for recording transference paths of all objects in a logistics process.

Different levels of traceability require to obtain different numbers of blockchain transactions. One of the major challenges is to improve the efficiency of tracing the path of a logistics object. The natural way is to traverse the whole block transactions for obtaining all links on a path, which could be time consuming because checking semantic links stored in a blockchain transaction requires obtaining the authority of the hosts of the payee account of blockchain transactions. To make the process more efficient, one way is to reduce the number of accesses to accounts, and another way is to let the tracing process be conducted in parallel.

5. Reducing the Average Accesses to Account

To reduce the number of accesses to the hosts while still maintaining a certain level of decentralization, it is necessary to keep balance between the number of accesses to the hosts and the decentralization of storage. According to the location mapping in Definition 5, in two cases of the location of d, u—<l, d>→v is mapped onto the payer account u and in one case l is mapped onto the payee account v. Due to the location inference rules in Definition 3, the hosts of the blockchain transactions published for a link with different states is unevenly distributed among two computing host of the two accounts. Thus, for obtaining the states of links, the average number of accessing the two hosts is reduced from 2 to 1.4 as shown in Theorem 1.

Theorem 1.

Assuming that a query on the k states of a given link l visits each state with the equal probability, the expected times of accessing the hosts of blockchain transactions for l is 1.414, when using the host mapping function in Definition 5.

Proof.

From the link inference rules in Definition 3 and location mapping function in Definition 5, one can see that 5 out of 6 states of a link u—<l, d>→v is mapped into the account u. Then, if all k states are within the 5 states stored in u, then one access to the account u is enough, if there is at least one visit to the state stored in v, then two accesses are required. The expectation can be obtained by modelling the probability of having one host access and having two hosts accesses as a binomial distribution:

That is, when the states are stored in an unbalanced way distributed on two hosts of a link, more states of links can be accessed on one host of a transaction that stores more states of links than another. When p = 5/6, E(X) obtains the minimum. □

5.1. Improving Efficiency of Path Tracing by Adding Shortcut Links

Although the unbalanced storage distribution of link states can reduce the average accessing times for checking the states of a link, it is still inevitable to traverse each host of account of each blockchain transaction published for a link path when implementing the link path traceability. The total number of accesses is proportional to the number of hosts for storing the path of links. Specifically, to access a path L(di) = {v1, l1, v2, l2, v3, …, ln, vn} of the object di from node v1 to node vn, it first needs to visit the root node to obtain the first blockchain transaction starting from v1 and then it obtains the first link l1 and its corresponding states. Following the blockchain transaction pointer from v1, the next host v2 is accessed to obtain the second link l2 until reaching the final node vn, where all hosts v1, v2, v3, …, and vn are accessed sequentially by at least one time and each access needs an authorization of the payer account of the blockchain transaction. It can be time-consuming when sequentially visiting each payee account for verification of blockchain transactions.

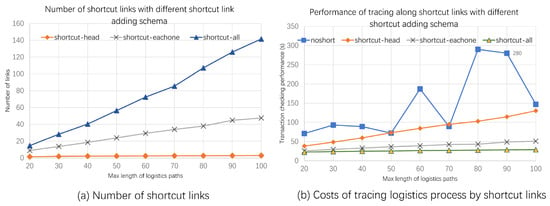

To reduce the number of accesses to hosts for getting a link path L(d), a simple way is to separate the whole path L(d) into to ⌈n/s⌉ segments and select the first node in each segment of s nodes as a representative host to hold the links within the segment so that one access to the representative node can obtain links of the whole segment of L(d). ⌈n/s⌉ representative nodes are enough to hold all n links and the number of accesses of hosts is reduced to ⌈n/s⌉. However, the total length n of the path cannot be obtained during the link publishing process, which makes it difficult to obtain a proper s for determining ⌈n/s⌉. To overcome this limitation, an algorithm is designed to add shortcuts among nodes on a path of link L(d) in a probabilistic manner without knowing the length of the path. Instead of splitting the path L(d) into segments, it lets each node on a link path randomly add a set of shortcut links from itself to its following nodes along the path when a link is being published in a blockchain transaction. A shortcut link allows a query along the path L(d) to jump over a sub sequence of nodes from a node to the rear part of the link path by following the pointer of the shortcut link. The aim is to allow the tracing process to visit log(n) nodes to reach the end of the path and obtain all links in L(d) without knowing n. After building the shortcuts, the node holds replicas of node IDs within the sub-sequence of the link path from the node to its longest shortcut on the link path so that one can obtain the path in L(d) by visiting log(n) nodes. In this way, log(n) shortcuts are built for each node to enable accessing the path L(d) within log(n) steps of jumps from the root node to the final target node in L(d). Since each node is stored in one host, thus, log(n) hosts are accessed to obtain the link path.

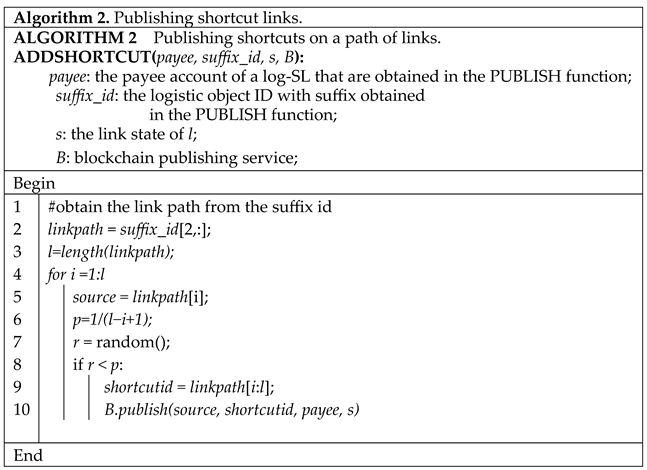

Algorithm 2 shows the shortcut publishing algorithm. A shortcut is constructed as the logistics object d is transferred to a payee account when a link is published in a block transaction from a payer account to the payee account. The suffix ID of the object d is used as a token to record the account IDs that it has been transferred to. Thus, the path of d can be obtained from the suffix ID (in Line 1). For each node vi on the path, the distance si from vi to payee is l − i + 1 and a short cut is constructed in a random sampling way with the sampling probability of 1/si (from line 6 to line 10). When a shortcut link is built, a blockchain transaction with the suffix ID of the logistics object d from vi to payee is published by vi so that the account vi will have a pointer to payee (line 10). Note that the length l is not the final length of the link path, it is the length of current path that has been passed through by d. Thus, the algorithm does not need to know the length of the final path.

|

5.2. Analysis of Performance of Tracing Path Along Shortcut Links

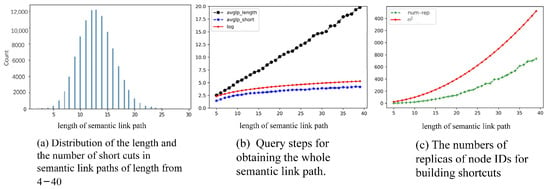

According to Theorems 3 and 4, each node along the path L(di) will have O(ln(n)) shortcut links on average, and the expected steps to obtain the whole links of L(di) is O(ln(n)).

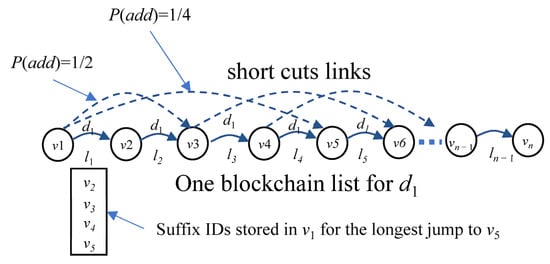

Figure 6 shows an example of shortcuts appended on a blockchain list for one logistics object d1. There are shortcut links across multiple nodes on the link path. For example, v1 has two shortcuts to v3 and v5, respectively, then it has replicas of node IDs of the path from v1 to v5. The shortcut to v3 is added with a probability of P(add) = 1/2 because logistics object d1 moves 2 steps from v1. The shortcut to v5 is added with a probability of P(add) = 1/4. By accessing v1, one can obtain a set of nodes from v2 to v5 of the current path, which can greatly speed up traversal performance.

Figure 6.

Shortcuts on a blockchain list.

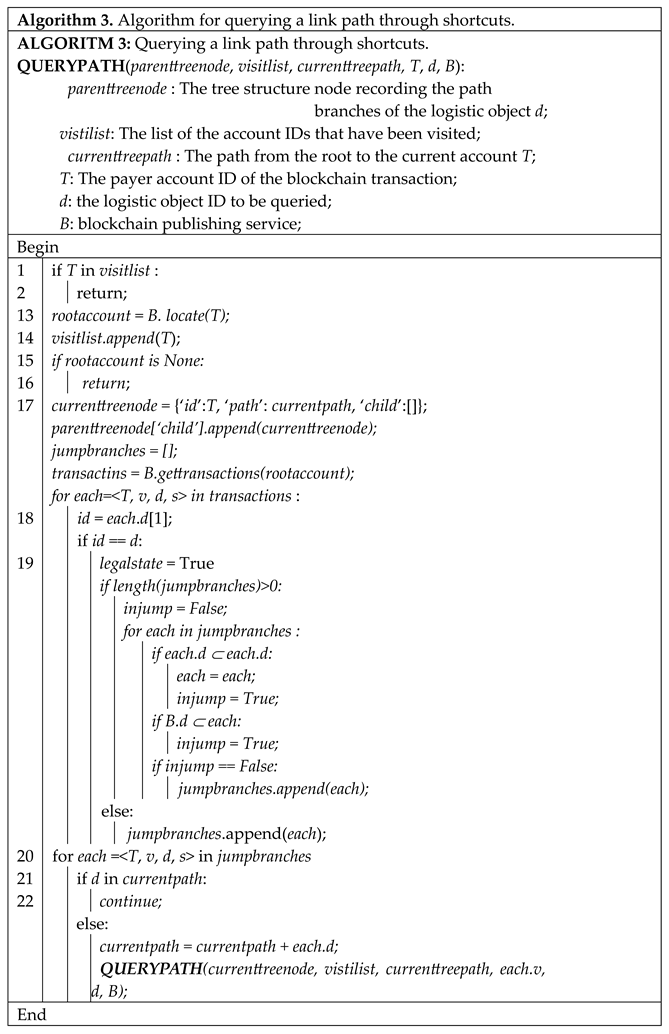

A query on a path of links is processed in an iterative way to obtain a tree structure formed by the paths of a logistics object d transported from the root account T (shown in Algorithm 3). The Algorithm 3 includes the following input arguments: parent records the current tree node to be constructed to record the paths starting from the first root node of the tree used as the final output argument of the algorithm, visistlist records the account IDs that have been processed, currenttrepath records the tree path that has been traversed from the root account, T is the current blockchain account ID that the query is processing, the logistics object ID d is the query target ID, and B is the blockchain platform service interface.

|

The Algorithm 3 starts from the root account T of a logistics process. In each iteration, a tree node currenttreenode is constructed in line 8 and is set as a child node of the tree node parenttreenode, which finally forms a tree consisting of paths of the logistics object d has been traversed as the query result. After constructing the current tree node, all the blockchain transactions started from T are obtained (line 11), and each blockchain transaction is checked to find those blockchain transactions that are used to transfer the query target d (line 13 and 14). For each of these blockchain transactions, two cases need to be handled. If the suffix ID (B.d in line 13) of the blockchain transaction B = <T, v, d, s> is longer than an existing suffix IDs that have been located and store in jumpbranches (line 18), then the blockchain transaction stored in jumpbranches is replaced by current B (line 19). If there is no such blockchain transaction, B is a new branch of transport of d and is appended to the list jumpbranches. In this way, the blockchain transaction that has the longest jump can be located. After checking all the blockchain transactions sent from T, jumpbranches contains the longest paths that d has taken. Then, for each jump in jumpbranches, the iterative call on QUERYPATH(currenttreenode, vistilist, currenttreepath, each.v, d, B) will recursively process each branch using the updated input argument in the last call of the procedure until reaching the leaf nodes that have no branch of transport of d (line 32). The recursive call can be processed in an asynchronous way so that the branches can be processed concurrently processed efficiently by leveraging the shortcut jumps.

According to Theorem 2, the expected number of shortcuts added for each node is ln(n), where n is the total number of nodes in the link. The number of steps for finding a node is also bounded by ln(n) (Theorems 3 and 4). According to Theorem 5, the number of suffix IDs for duplication during the shortcut construction along a path is O(n2). All links can be obtained within the O(ln(n)) steps by allowing a query from the starting node to concurrently process along all the shortcut links, which can be deemed as a width-first concurrent traverse on a tree of depth O(ln(n)).

Theorem 2.

The expected number of shortcut links for v1 is O(ln(n)).

Proof.

At the ith step of movement of di, the probability of adding a shortcut link from v1 is 1/i. The expectation of the number of links from v1 to the ith node is also 1/i. The expectation of the total number of shortcut links of v1 is the sum of expectations of the ith nodes for i = 1, …, and n, which is O(ln(n)) according to the upper bound of the limitation of the sum of the first n elements in a Harmonic series [38]. □

Theorem 3.

The expected number of steps for reaching a target node vj from vk is O(ln(j − k)).

Proof.

Assuming vk is at the tth step and the number of steps from vk to vj is j − k, which is represented as s(t) = j − k. Then there is one shortcut vq from vk that can jump across a segment of steps (j − k)/e with high probability. That is, vq that can help reduce the distance from 1/e of s(t) and the distance from the vq to vj is (j − k)/e. Recursively applying this process, there is at most O(ln(j − k)) steps to reach vj. □

According to Theorem 3, the following expected upper-bound of the longest jump can be obtained.

Theorem 4.

The expected longest jump from vk to vj is O((j − k)/e).

According to Theorem 3 and 4. The expected number of IDs stored for a node vk is the (n − k)/e. There are n(n − k)/e node IDs on n nodes for one link path and a query from any node to its following ending node in the path can be processed in O(ln(n)) steps involving O(ln(n)) access to nodes.

Theorem 5.

The expected number of suffix IDs for a link of length n is O(n2/e)).

Proof.

According to Theorem 2, the longest expected jump is 1/e, which incurs n/e replicas of suffix IDs. Therefore, n nodes will have at most n2/e replicas of node IDs. □

5.3. Penalty-Reward for Speeding up Confirmation of Link States

A penalty–reward policy is designed to encourage users to publish semantic links in a consistent way to avoid conflict in the confirmation of a link state by the participants of the logistics transports. When publishing a semantic link u—<l, d>→v with state l(n), the hosts of node u and v of the semantic link need to confirm the consistency of the published link with the real logistics transport. If the link is correctly published, then the two hosts should reach consensus on the state of the published link. Otherwise, they should make a check on the status of the logistics transport. If they cannot reach a consensus on the state of the link, they are unable to publish new links. There should be a penalty on the account u who publishes inconsistent links that cannot be confirmed by node v. But there can be malicious responses on confirmation, thus we need to control the confirmation process to let responses also pay costs so that malicious responses can be suppressed.

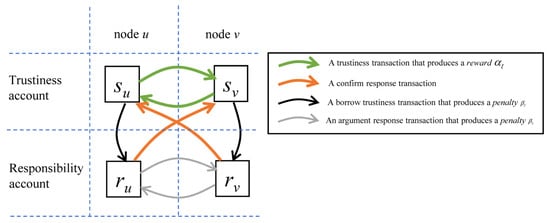

To implement such a policy, each node is assigned two scores in two accounts su and ru, where su is the trustiness account that is used for starting a confirmation of link and ru is the responsibility account that is used to store the score that needs to respond to a confirmation. Then, the confirmation process is conducted by transferring scores through blockchain transactions among the trustiness account and the responsibility account of two nodes. It can be implemented in a smart contract. Four types of transactions can be issued among the four accounts of two nodes u and v as shown in Figure 7. The whole confirmation procedure can be executed in following four stages:

Figure 7.

Confirmation transactions.

- (1)

- The trustiness transactions are issued between su and sv, which are used to send confirmation requests and confirmation responses for each published link t (two green arrows in Figure 7). The trustiness score is added by St when there is a new link t to be confirmed. A trustiness transaction will transfer St from su to sv. Thus, the trustiness transaction can be executed only once for one link. When node v confirms the link state, the trustiness score St is sent back to su in another trustiness transaction, and a reward score αt is added to both trustiness accounts of su and sv.

- (2)

- If node v has a conflict on the confirmation, it needs to start an argument to respond to node u. In this case, it will not use the trustiness transaction. Instead, node v uses the account rv to make an argument response transaction to ru with score St (gray arrow in Figure 7). However, the response account rv does not have initial scores, which need to borrow scores from its own trustiness account sv in a borrow trustiness transaction (dark arrows in Figure 7). Then, the score is sent to the responsibility account in an argument response transaction. When node u receives the transaction scores in its ru, it knows that there is a conflict on confirmation. Node u needs to check the transport with node v so that they can reach a consensus on the state of the link.

- (3)

- If they reach a consensus, node u uses the confirm response transaction to send score St back to the trustiness account sv of node v. Then, node v sends St back to node u through a trustiness transaction. In this case, the confirmation completes.

- (4)

- If they need further arguments, response transactions are used to send scores from their own responsibility account to counterpart’s responsibility account, until one sends the score St back to the trustiness account, which indicates that they reach consensus.

Since the responsibility account initially has a zero score, it needs to borrow scores from the trustworthiness account to make an argument. Moreover, there is an extra penalty βt charged on their trustiness account for each borrow trustiness transaction. Each argument transaction is also charged by βt. That is, if more arguments are made, their trustworthiness score will be exhausted, and they will not have enough trustworthiness score to start a new confirmation process for a new link and start an extra argument response. So, malicious responses are costly for both sides of a link. On the contrary, if they can reach consensus quickly on a confirmation just using the trustiness transactions, rewards can be accumulated in their trustiness accounts.

Finally, a reliability score Ru = su − ru can be obtained for a node u as the indicator of the performance of u. A higher Ru means that there are more consistent links published and fewer arguments for node u. The nodes with a reliability score lower than a threshold R will be halted.

As the topology shown in Figure 7 is strongly connected, the scores will finally approach an ending distribution for four accounts. In an extreme case, the two nodes halt after their reliability score is lower than R.

Theorem 6.

The scores of su, sv, ru, and rv will approach a halting condition for one complete confirmation process with two trustiness transactions.

Proof.

As the graph of Figure 7 is strongly connected, there are two possible ending states: two trustiness transactions are finally executed; their reliability scores T are exhausted. □

One possible situation is that one participant does not take any further action. In this case, its responsibility account and trustiness account are not balanced. The further actions can be halted according to the unbalance of the two accounts of a host.

As the account score can be exhausted when too many confirmation requirements are issued, it can help protect confirmation from DoS attacks. Moreover, the account score can be accumulated when completing the logistics process by end-users, which can also help prevent a Sybil attack to some extent when end-users are verified on the blockchain.