Abstract

This study evaluates Empirical Bayes (EB) c-charts for monitoring count-type data under precautionary (PLF) and logarithmic (LLF) loss functions. By assuming an exponential prior for the Poisson mean, the EB framework enables the construction of predictive densities for future observations. Simulation studies and a real-world dataset on missing rivets in large aircraft were used to compare the methods’ ability to detect out-of-control conditions. The results show that EB–LLF charts exhibit high sensitivity for small and moderate process shifts, and both EB approaches outperform the classical c-chart by integrating prior information to detect shifts earlier while controlling false alarms. These findings highlight the importance of loss function choice and demonstrate the effectiveness of EB charts for robust process monitoring.

1. Introduction

Statistical Process Control (SPC) serves as a cornerstone in ensuring process stability and maintaining product and service quality. It provides a systematic and data-driven framework for identifying unexpected deviations or shifts in process performance, enabling timely corrective actions before nonconformities escalate. Beyond its traditional applications in industrial manufacturing, SPC has found relevance in numerous modern domains—such as healthcare [1,2,3], finance [4,5], information systems and network monitoring [6,7], and energy and environmental monitoring [8,9,10]—where the early detection of abnormal patterns plays a vital role in minimizing risk and improving operational efficiency.

Within the diverse family of SPC tools, the c-chart is one of the most widely adopted methods for monitoring attribute-type data, specifically the number of defects or nonconformities in inspection units of fixed size. It is grounded in the Poisson distribution, making it suitable for situations where defect occurrences are independent and rare. Practical examples include detecting surface imperfections on materials, counting assembly errors, or recording missing components in production lines. By visualizing defect counts over time within upper and lower control limits, the c-chart enables practitioners to distinguish between natural fluctuations in the process and statistically significant shifts that may indicate underlying process deterioration [11,12,13,14]. Consequently, the c-chart helps maintain process reliability by separating common cause from special cause variation, ensuring that interventions are both justified and effective.

Despite its long-standing usefulness, the traditional c-chart is often limited by its reliance on fixed parameters derived from classical estimation methods. Such fixed parameter designs become less reliable in uncertain or dynamically changing production environments, where defect rates may evolve over time and the assumption of process stationarity no longer holds. These conventional approaches also lack mechanisms to formally incorporate prior information or quantify uncertainty, resulting in delayed detection, increased false alarms, and reduced robustness when the process exhibits parameter drift.

To address this limitation, Bayesian inference has been increasingly utilized in SPC due to its inherent capacity to incorporate prior information, handle uncertainty, and adapt to sequential decision-making scenarios. As highlighted by Bayarri and Garcia-Donato [15], Bayesian approaches provide more flexible and coherent inferential structures than classical techniques. Several studies have demonstrated that Bayesian-based control charts outperform traditional methods in adjusting sampling frequencies, determining control limits, and optimizing decision rules through posterior probability updating [16,17]. Moreover, Bayesian principles have been successfully applied to construct control charts for monitoring the mean and variance in both normally [18] and non-normally distributed processes [19,20,21,22], as well as in developing Bayesian charts under various loss functions for process monitoring frameworks [23,24,25]. Furthermore, a variety of loss functions within the Bayesian framework—ranging from the conventional and weighted squared error loss to more recent formulations such as the K-loss, DeGroot loss, and precautionary loss—have been investigated in both estimation studies [26] and control chart design [27]. Comparative findings consistently show that Bayesian charts constructed under precautionary and K-loss functions exhibit superior sensitivity to out-of-control conditions relative to their classical counterparts [27,28,29,30,31], highlighting the importance of loss function choice in enhancing detection capability. Building on these developments, our study introduces an Adaptive Empirical Bayes framework to address the practical challenges of monitoring count-type data under evolving process conditions and uncertainty.

Building on the expanding role of Bayesian and loss function-based approaches in SPC, another promising direction is the Empirical Bayes (EB) framework. When prior distribution parameters are not explicitly known but estimated directly from observed data, the approach is termed Empirical Bayes (EB). This hybrid methodology combines the strengths of Bayesian and frequentist paradigms by using empirical data to refine prior information. The Empirical Bayes method has demonstrated strong potential for estimation and classification problems, and its applications in SPC have improved adaptability and accuracy in control chart design [32,33,34]. Recent research has shown that EB-based SPC techniques offer advantages in dynamically updating control limits and enhancing robustness under model uncertainty [35]. Furthermore, studies incorporating non-informative priors, such as the Jeffreys prior, have demonstrated significant improvements in key performance indicators, including the Average Run Length (ARL) and the Standard Deviation of Run Length (SDRL) [36], compared to the classical approach [37].

A recent study by Supharakonsakun [38] further advanced the Bayesian c-chart by employing the gamma prior to derive posterior predictive control limits. This modification resulted in higher ARLs and lower false alarm rates than conventional methods, confirming the superiority of Bayesian frameworks for process monitoring. However, the effectiveness of such models depends strongly on the choice of hyperparameters, suggesting that data-driven adjustment mechanisms are essential for optimal performance. The Empirical Bayes approach provides an attractive alternative, allowing for adaptive estimation of these hyperparameters directly from process observations.

Motivated by these developments, the present research focuses on evaluating the signal detection performance of a Bayesian-based attribute control chart constructed under the Empirical Bayes framework. In particular, this study explores parameter estimation using the precautionary loss function, which accounts for asymmetric decision risks, and compares its performance with the conventional squared error loss function and the classical c-chart. This work explicitly extends an earlier study [35], which introduced the use of Empirical Bayes methods for constructing c-charts within a single loss function framework. Building on this foundation, the present study broadens the analysis by incorporating and comparing two additional loss functions—the Precautionary Loss Function (PLF) and the Logarithmic Loss Function (LLF)—to provide a more comprehensive evaluation of how different Bayesian decision criteria influence chart performance. This extension provides deeper insights into the role of loss function selection in EB-based attribute control charts and enhances the generalizability of the previous findings.

The remainder of this article is structured as follows: Section 2 introduces the Empirical Bayes framework for constructing c-charts under different loss functions; Section 3 presents simulation studies assessing chart performance across various process shifts and sample sizes; Section 4 applies the proposed methodology to a real dataset on missing rivets in large aircraft; and Section 5 provides the discussion and conclusions, summarizing insights and implications for practical process monitoring. The aim is to assess the chart’s efficiency in detecting process shifts and improving decision robustness under uncertainty, thereby introducing a novel and adaptive framework for attribute defect monitoring.

2. Empirical Bayes for the c-Chart Under Loss Function Frameworks

The c-chart is widely used in situations where defect occurrences follow a Poisson distribution, such as monitoring surface imperfections in materials, identifying missing components in assembly processes, or detecting errors in printed circuit boards. By continuously plotting the number of detected defects against statistically derived control limits, the c-chart allows practitioners to recognize unusual increases in defect counts, signaling potential disturbances that warrant investigation and corrective measures [39].

The traditional control limits, determined under the assumption that the process mean represents the average number of defects per inspection unit, are calculated as follows:

When inspection units are independently and uniformly sampled over time, the count of nonconformities detected in the ith observation is modeled as a Poisson process with parameter , the expected number of defects per inspection interval. The probability mass function can thus be expressed as

However, the traditional control limits are derived under fixed parameter assumptions and often neglect process uncertainty or prior information regarding the defect generation mechanism. In practical scenarios, such assumptions may lead to biased assessments of process stability and delayed identification of abnormal variations. To overcome these limitations, Bayesian approaches have been proposed that integrate prior knowledge with observed data to establish posterior-based predictive control limits that dynamically adapt to changing process conditions.

Furthermore, when the prior parameters are unknown and estimated directly from observed data, the Empirical Bayes (EB) approach provides a more data-driven alternative. This method bridges the gap between full Bayesian inference and classical estimation by refining the prior distributions through empirical evidence. As a result, Empirical Bayes estimation enhances the flexibility and robustness of the c-chart, thereby improving its sensitivity to subtle process shifts or deviations.

In this study, an informative prior is employed within the Bayesian framework.

Let the random variable follow an exponential distribution with parameter , denoted as ∼ Exp(), which is a special case of the Gamma distribution with the shape parameter equal to 1.

The probability density function (PDF) of the exponential distribution is given by

Supharakonsakun and Jampachasri [40] proposed an Empirical Bayes estimator for by estimating the hyperparameter using the maximum likelihood estimator (MLE) derived from the marginal posterior distribution (see [41]). The MLE of the hyperparameter is obtained as

where denotes the sample mean, calculated as the average of the observed count data collected across all inspection units.

In this study, the Empirical Bayes framework adopts this MLE-based estimate () across all simulation experiments and real-world applications. This specification ensures a fully data-driven prior that is coherent with the predictive density formulation used in conjunction with the PLF and LLF.

The posterior distribution of can be obtained by combining the prior information with the likelihood function derived from the observed data. By applying Bayes’ theorem, the posterior distribution can be explicitly expressed, providing a complete probabilistic description of that incorporates both prior knowledge and observed evidence, as follows:

Specifically, it can be shown that the posterior distribution of follows a gamma distribution with shape parameter and rate parameter , which can be expressed as

In this formulation, Y denotes the number of nonconformities observed within an inspection unit. The above expression can be further reformulated into a predictive density function, as shown below (see [18]):

By simplifying the expression, the predictive density can be written as

Hence, the predictive density follows a negative binomial distribution, which can be denoted as

These advantages become particularly evident when the estimation process is examined under different loss function frameworks, such as the squared error loss function (SELF) and the precautionary loss function (PLF). Each of these frameworks provides a distinct lens for evaluating estimation accuracy and decision-making sensitivity.

In statistical inference, a loss function is a quantitative measure that penalizes the discrepancy between an estimated value and the true, unknown parameter. The choice of a loss function directly influences the nature of the resulting estimator, reflecting the emphasis placed on underestimation or overestimation errors. Accordingly, selecting an appropriate loss function is crucial for aligning the estimation process with practical objectives and risk preferences in quality control and process monitoring.

Among various alternatives, the squared error loss function (SELF) has been the most commonly adopted criterion due to its mathematical simplicity and symmetric treatment of estimation errors. It penalizes deviations from the true value equally in both directions, yielding estimators that are optimal for minimizing the expected squared deviation. The SELF framework also provides a convenient analytical foundation for Bayesian estimation, where the optimal estimator is the posterior mean.

2.1. Squared Error Loss Function (SELF)

The squared error loss function (SELF) is one of the most widely used and fundamental loss functions in statistical estimation theory. Originally introduced by Legendre [42] in the context of the method of least squares and later formalized by Gauss [43], the SELF provides a symmetric and analytically convenient criterion for evaluating the accuracy of parameter estimates.

Let denote the unknown parameter associated with a study variable Y, and let represent an estimator of μ that minimizes the expected posterior loss. The SELF measures the discrepancy between the estimator and the true parameter value and is defined as

Under this loss function, the Bayes estimator is obtained by minimizing the posterior expected loss. It can be shown that the resulting estimator corresponds to the posterior predictive mean, expressed as

For the exponential Empirical Bayes (EB) prior, the detailed derivation and proof of the Bayes estimator under the squared error loss function are provided in [43]. The resulting form of the estimator can be expressed as follows:

which highlights the estimator’s dependence on the posterior expectation of the parameter, given the likelihood of the observed data.

This property makes the SELF particularly attractive in Bayesian analysis, as it is simple, symmetric, and directly interpretable as a measure of estimation accuracy.

2.2. Precautionary Loss Function (PLF)

The precautionary loss function (PLF) employed in Bayesian estimation is a symmetric, continuous, and differentiable function of both the true parameter, denoted by , and its estimator, . This function is particularly appropriate in decision-making environments where the consequences of overestimation and underestimation are equally undesirable. Unlike asymmetric loss functions that assign different penalties depending on the estimation direction, the PLF treats both types of estimation errors equally, thereby promoting more stable and conservative inferential decisions.

The formal definition of the precautionary loss function has been established in the literature [44,45,46], as follows:

In Bayesian inference, the precautionary loss function serves as a decision-theoretic foundation for deriving estimators that minimize expected posterior loss. Specifically, the Bayesian estimator under the PLF is obtained by minimizing the posterior expected value of the loss function, conditional on the observed data. This process incorporates both the posterior predictive distribution and the uncertainty associated with the underlying model parameters:

To initiate this derivation, the posterior predictive variance must first be determined, as it plays a central role in defining the expected loss and, consequently, the optimal estimator. For an informative prior, particularly an exponential Empirical Bayes (EB) prior, the variance of the posterior predictive distribution can be expressed as

Using this result, the Empirical Bayes estimator of the Poisson parameter under the precautionary loss function—based on the posterior predictive density derived from the exponential prior—is formulated by minimizing Equation (11). The intermediate steps of this derivation can be presented as follows:

Accordingly, the Bayesian estimator for the posterior predictive density under the precautionary loss function with exponential Empirical Bayes prior is obtained as

2.3. Logarithmic Loss Function (LLF)

The logarithmic (mode-based) loss function employed in Bayesian estimation is particularly suitable for discrete count data, such as the number of nonconformities monitored using a c-chart. Unlike symmetric loss functions that minimize mean or squared deviations, the mode-based loss focuses on the mode of the posterior predictive distribution, making it appropriate when the most likely outcome is of primary interest.

In the literature, the formal definition of the logarithmic loss function was provided by Brown (1968) [47] as follows:

The Bayesian estimator under this loss function, commonly referred to as the mode-based Bayes estimator, is defined as the mode of the posterior predictive distribution conditional on the observed data:

For the negative binomial posterior predictive distribution derived from an Empirical Bayes (EB) approach from Equation (8), the mode of predictive density of Y can be explicitly expressed as

The resulting estimate represents the most likely number of nonconformities in a future inspection unit, taking into account both the information from the observed data—namely, the total number of defects across inspected units—and the prior knowledge, reflected in the sample size and the prior hyperparameter estimate. By adopting the mode as the estimator, practitioners obtain a stable, practical value that highlights the most probable outcome rather than the average, which is especially advantageous when working with discrete count data and when process monitoring is intended to capture the typical pattern of defect occurrences.

The Empirical Bayes (EB) estimators derived from the exponential prior under both the squared error loss function (SELF), the precautionary loss function (PLF), and the logarithmic loss function (LLF) are subsequently employed to establish control limits for the c-chart. These limits are then compared with those obtained from the traditional estimator used in the classical c-chart framework. The comparative evaluation aims to determine the degree to which the EB-based approaches enhance sensitivity and stability in process monitoring.

The proposed EB predictive approach is inherently adaptive, as it updates parameter estimates and the resulting control limits according to the selected loss function. This adaptive feature enables the control chart to respond with varying sensitivities to process shifts, reflecting different risk attitudes and enhancing the overall effectiveness of monitoring.

The effectiveness and efficiency of the proposed control chart procedures are primarily assessed using the Average Run Length (ARL) criterion, which measures the expected number of samples taken before an out-of-control signal is triggered. To provide a more comprehensive performance evaluation, two supplementary metrics—namely, the Average Extra Quadratic Loss (AEQL) and the Performance Comparison Index (PCI) introduced by Alevizakos et al. [48]—are also incorporated into the analysis.

The AEQL quantifies the average deviation between the estimated and true process conditions, thereby serving as an indicator of estimation accuracy and signal responsiveness. It is defined as follows:

Here, δ represents the magnitude of process change, reflecting the incremental shift between the in-control and out-of-control states. In this study, a value of δ = 10 is adopted to represent a meaningful and practically observable level of process variation. Control charts yielding smaller AEQL values are considered to demonstrate superior detection capability and more reliable estimation accuracy.

To facilitate a direct comparison of AEQL performance across different charting methods, the Performance Comparison Index (PCI) is employed. This index expresses the efficiency of each control chart relative to the chart exhibiting the lowest AEQL value, thus serving as a standardized efficiency measure:

A PCI value of 1 indicates the most efficient control chart design, while values exceeding 1 indicate comparatively lower efficiency relative to the benchmark chart.

The simulation results, including the ARL-based performance assessment and the comparative analysis of AEQL and PCI across various methods, are presented and discussed in the following section.

3. Simulation Studies

The simulation study, conducted in R, compared the Empirical Bayes (EB) and frequentist approaches for detecting shifts in the process mean ( set to 10, 5, 20, and 25). The EB method was evaluated under three loss functions: squared error (SELF), precautionary (PLF), and logarithmic (LLF).

The study covered a wide range of shift magnitudes (δ = 0.01 to 10.0) and inspection unit sizes (20, 30, and 50), with the in-control Average Run Length (ARL0) fixed at 370. Performance was judged by minimizing the out-of-control ARL1, SDRL1, and AEQL; a control structure with a PCI of 1.0000 was designated as superior, indicating faster, more consistent, and cost-efficient detection.

Table 1 presents the ARL and SDRL values obtained from both classical and Empirical Bayes (EB) methods for inspection unit sizes of 20, 30, and 50 with = 10. The EB method using the proposed LLF consistently provides lower ARL1 and SDRL1 values across all shift magnitudes and inspection unit sizes. In addition, the AEQL and PCI values confirm the superior performance of the EB-LLF method, achieving the lowest AEQL and a PCI of 1.0000, demonstrating its high effectiveness in detecting process shifts.

Table 1.

Comparative ARL, SDRL, AEQL, and PCI for μ = 10 across different δ and sample sizes (n = 20, 30, 50).

Table 2 summarizes the results for = 15. For an inspection unit size of n = 20, the EB method under the SELF yields lower ARL1 and SDRL1 values for shift sizes δ ≤ 0.1. However, for larger shifts (δ = 0.5 − 10.0), both the classical and EB methods under the LLF perform better. When n = 30, the EB method under the SELF continues to show lower ARL1 and SDRL1 values for several shift magnitudes, with performance similar to the classical approach in some cases. For n = 50, the EB method under the SELF again provides smaller ARL1 and SDRL1 for δ ≤ 1.0, while the EB method under the LLF performs better for larger shifts (δ ≥ 2.0). Moreover, the EB-LLF method achieves the minimum AEQL and a PCI of 1.0000, reinforcing its high detection efficiency.

Table 2.

Comparative ARL, SDRL, AEQL, and PCI for μ = 15 across different δ and sample sizes (n = 20, 30, 50).

Table 3 presents the results for = 20. The EB method with the proposed LLF consistently achieves lower ARL1 and SDRL1 values across all shift magnitudes and inspection unit sizes. Similarly, the AEQL and PCI results confirm the superior performance of the EB-LLF method, with the lowest AEQL and a PCI of 1.0000, indicating strong detection capability and robustness.

Table 3.

Comparative ARL, SDRL, AEQL, and PCI for μ = 20 across different δ and sample sizes (n = 20, 30, 50).

Table 4 reports the findings for = 25. The EB method with the LLF again provides lower ARL1 and SDRL1 values for inspection unit sizes of n = 20 and 30 across all shift magnitudes. For n = 50, the EB method under the SELF performs the best for smaller shifts (δ ≤ 0.1); meanwhile, for larger shifts (δ = 0.5 − 10.0), both the classical and EB methods under the LLF outperform the others. For n = 30, the EB method under the SELF still yields smaller ARL1 and SDRL1 values across several shift magnitudes, with results comparable to those of the classical approach.

Table 4.

Comparative ARL, SDRL, AEQL, and PCI for μ = 25 across different δ and sample sizes (n = 20, 30, 50).

In addition, the AEQL and PCI results confirm the superior performance of the EB-LLF method, which achieves the lowest AEQL and a PCI of 1.0000, demonstrating consistency and high effectiveness in detecting process shifts.

4. Application

In this section, a performance comparison is conducted between the traditional c-chart and Empirical Bayes (EB) c-charts constructed under three loss function frameworks: the squared error, precautionary, and logarithmic loss functions. To demonstrate their applicability, a real dataset concerning the inspection of missing rivets on large aircraft is analyzed. The dataset consists of 26 successive observations, each corresponding to the number of missing rivets identified per aircraft. Because these defects are presumed to occur randomly and independently throughout the aircraft structure, the count of nonconformities in each sample is modeled using a Poisson distribution [49]. Although this dataset does not include specification limits typical of manufacturing processes, it provides a practical example to illustrate the applicability and comparative performance of the traditional and EB c-charts.

This dataset provides a practical setting for examining how effectively each charting approach can identify shifts in the process mean. The Poisson mean parameter was separately estimated using the classical technique and three EB estimation procedures, each derived from a distinct loss function. These parameter estimates were subsequently used to define the control limits for tracking changes in the average number of defects. A constant control width of three standard deviations was adopted across all charting schemes. The comparative outcomes of the four control charting strategies are illustrated in Figure 1, Figure 2, Figure 3 and Figure 4.

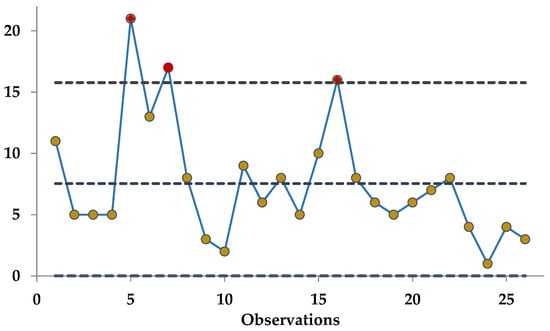

Figure 1.

Classical c-chart for monitoring missing rivet counts.

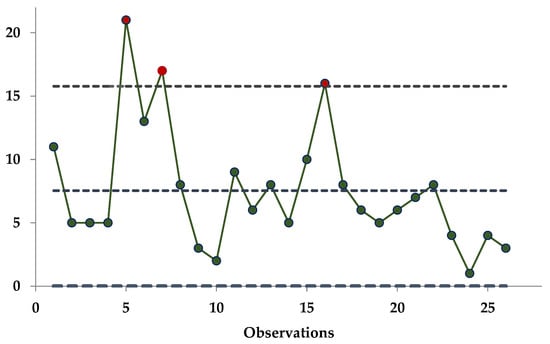

Figure 2.

EB c-chart under the squared error loss function (SELF).

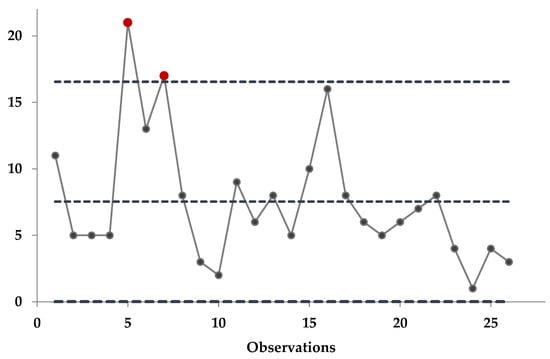

Figure 3.

EB c-chart under the precautionary loss function (PLF).

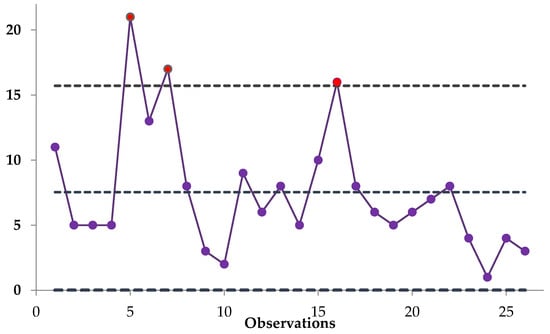

Figure 4.

EB c-chart under the logarithmic loss function (LLF).

Figure 1 depicts the traditional c-chart constructed from the actual dataset. The chart indicates that the process went out of control at the 5th, 7th, and 16th observations. The delayed recognition of these abnormal points reveals the limited responsiveness of the conventional method, particularly in detecting gradual or minor process deviations. This drawback underscores the need for more flexible monitoring strategies, such as Empirical Bayes (EB)-based approaches, especially in industries that require high sensitivity to quality variation.

Figure 2 presents the results of the EB c-chart formulated under the squared error loss function. Using this approach, abnormal conditions are identified at the 5th, 7th, and 16th observations. Compared with the classical chart, this EB version responds more rapidly to process irregularities. The earlier detection of these variations demonstrates its higher sensitivity, which can be highly beneficial in manufacturing contexts where timely identification of defects supports waste reduction and consistent quality control.

Figure 3 presents the EB c-chart derived from the precautionary loss function. Unlike the other EB approaches, this chart detects out-of-control signals only at the 5th and 7th samples. The limited number of detections suggests that the precautionary loss function is less responsive in identifying process mean shifts. Consequently, its effectiveness appears lower than that of the EB charts based on the squared error and logarithmic loss functions.

Figure 4 illustrates the EB c-chart developed using the logarithmic loss function. This method also identifies out-of-control signals at the 5th, 7th, and 16th data points, reflecting the same pattern observed in the other EB configurations. The uniformity of the results across all EB charts demonstrates the stability and robustness of the Bayesian framework, regardless of the chosen loss function.

Overall, the empirical results indicate that the EB c-chart based on the precautionary loss function exhibits comparatively lower sensitivity in detecting process mean shifts. Unlike the other EB variations, this chart identified only two out-of-control points—at the 5th and 7th observations—suggesting a more conservative detection behavior. While its performance is less responsive, the method may still offer advantages in processes where excessive false alarms must be avoided or where only significant deviations are of concern.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

The comparative evaluation of the Empirical Bayes (EB) control charts shows that the choice of loss function plays a crucial role in monitoring performance. The EB chart based on the logarithmic loss function (LLF) consistently exhibited the highest sensitivity to process mean shifts in both simulation studies and real rivet inspection data. Its ability to detect small deviations early while maintaining stable false alarm rates indicates a well-balanced and robust detection mechanism, making it particularly suitable for industrial and environmental applications where rapid anomaly identification is essential.

In contrast, the EB chart using the precautionary loss function (PLF) behaved more conservatively, detecting fewer out-of-control points and yielding higher ARL1 and SDRL1 values across several scenarios. Although less sensitive than the LLF-based chart, the PLF approach offers greater resistance to overreaction due to minor random fluctuations, making it appropriate for processes where operational stability and false alarm avoidance are prioritized. Overall, while both EB methods outperform the classical c-chart by incorporating prior information and adapting control limits to the observed data, the LLF provides the best balance between early detection and reliability.

A key limitation of this study is the assumption of an exponential prior for the Poisson mean. While this assumption facilitates analytic tractability within the EB framework, it may not adequately represent processes with highly variable or multi-modal defect patterns. Future work could explore more flexible prior distributions, such as Gamma or mixture priors, to improve the model’s generalizability. Additionally, the proposed EB c-charts rely on Poisson-based count data, which may not fully capture dispersion characteristics in processes exhibiting overdispersion, zero inflation, or dependence among defect occurrences. Extending the framework to accommodate these complexities further strengthens its practical applicability.

Future work may investigate hybrid or adaptive loss functions and explore alternative modeling perspectives—such as modeling inter-occurrence times via exponential distributions—to enhance the sensitivity and stability of EB-based control charts, particularly in settings where time-to-defect information provides additional insight into process behavior.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The R code for the developed algorithm (R version 4.0.5) is available upon request from the author.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- Li, R.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, H.; Lin, S.; Jia, G.; Fang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Song, X.; Zhao, J.; Hu, L.; et al. Towards interpretable drug interaction prediction via dual-stage attention and Bayesian calibration with active learning. PeerJ Comput. Sci. 2025, 11, e2847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eina, M.F.; Chrisnanto, Y.H.; Melina, M. Klasifikasi telemarketing menggunakan Naïve Bayes classification dan wrapper sequential feature selection. INTECOMS J. Inf. Technol. Comput. Sci. 2024, 7, 1189–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, X.-F.; Pu, L.; Lan, S.; Li, H.; Zeng, L.; Wang, H.; Zhang, L. Adverse drug reaction signal detection methods in spontaneous reporting system: A systematic review. Pharmacoepidemiol. Drug Saf. 2024, 33, e5768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisiotis, K.; Psarakis, S.; Yannacopoulos, A.N. Control charts in financial applications: An overview. Qual. Reliab. Eng. Int. 2022, 38, 1441–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeganeh, A.; Shongwe, S.C. A novel application of statistical process control charts in financial market surveillance with the idea of profile monitoring. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0288627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, Y.-T.; Wang, C.-H.; Chang, Y.-C.; Tong, L.-I. Using WPCA and EWMA control chart to construct a network intrusion detection model. IET Inf. Secur. 2024, 2024, 3948341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, J.; Lu, S. An effective intrusion detection approach using SVM with naïve Bayes feature embedding. Comput. Secur. 2021, 103, 102158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arciszewski, T.J. A Review of Control Charts and Exploring Their Utility for Regional Environmental Monitoring Programs. Environments 2023, 10, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, G.J.; Borges, A.C. Statistical Process Control in the Environmental Monitoring of Water Quality and Wastewaters: A Review. Water 2025, 17, 1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogo, A.B.; Henning, E.; Kalbusch, A. Statistical parametric and non-parametric control charts for monitoring residential water consumption. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 13543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Khalidy, A.K.; Enad, M.M.; Ghazi, M.H. Bayesian Estimation of Spherical Distribution Parameters under Degroot Loss Function. Iraqi Stat. J. 2025, 2, 105–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, T.; Javed, A.; Abbas, N.; Abid, M. On Monitoring of the Shape Parameter of the Inverse Gaussian Distribution via Memoryless Chart Under Bayesian Setup. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 27126–27140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, I.; Alamri, A.M.; Almarashi, A.M.; Elhag, A.A.; Aripov, M.; Hussain, S. Bayesian control chart using variable sample size with engineering applications. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 24683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaagan, A.A.; Noor-ul-Amin, M.; Khan, I.; Iqbal, J.; Hussain, S. An adaptive Bayesian approach for improved sensitivity in joint monitoring of mean and variance using Max-EWMA control chart. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 9948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbas, Z.; Ali, S.; Nazir, H.Z.; Riaz, M.; Li, Y.; Zhang, X. A comparative study on the nonparametric memory-type charts for monitoring process location. J. Stat. Comput. Simul. 2023, 93, 2450–2470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, Z.; Nazir, H.Z.; Riaz, M.; Shi, J.; Abdisa, A.G. An unbiased function-based Poisson adaptive EWMA control chart for monitoring range of shifts. Qual. Reliab. Eng. Int. 2023, 39, 2185–2201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canel, C.; Mahar, S.; Rosen, D.; Taylor, J. Quality control methods at a hospital. Int. J. Health Care Qual. Assur. 2010, 23, 59–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suman, G.; Prajapati, D. Control chart applications in healthcare: A literature review. Int. J. Metrol. Qual. Eng. 2018, 9, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiss, I. Application of U Chart and C Chart in Technological Process of Primary Wood Processing. J. Process Manag. New Technol. 2014, 2, 36–43. [Google Scholar]

- Seoh, Y.K.; Wong, V.H.; Sirdari, M.Z. A study on the application of control chart in healthcare. ITM Web Conf. 2021, 36, 01001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayarri, M.J.; Garcia-Donato, G. A Bayesian sequential look at u-control charts. Technometrics 2005, 47, 142–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamud, M.H.; Gul, A. Estimation of variance and mean by the Bayesian approach on Poisson EWMA (PEWMA) control chart. Commun. Stat.-Theory Methods 2025, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assareh, H.; Noorossana, R.; Mohammadi, M.; Mengersen, K. Bayesian multiple changepoint estimation of Poisson rates in control charts. Sci. Iran. 2016, 23, 316–329. [Google Scholar]

- Calabrese, J.M. Bayesian process control for attributes. Manag. Sci. 1995, 41, 637–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menzefricke, U. Control charts for the variance and coefficient of variation based on their predictive distribution. Commun. Stat.-Theory Methods 2010, 39, 2930–2941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menzefricke, U. On the evaluation of control chart limits based on predictive distributions. Commun. Stat.-Theory Methods 2002, 31, 1423–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menzefricke, U. Combined exponentially weighted moving average charts for the mean and variance based on the predictive distribution. Commun. Stat.-Theory Methods 2013, 42, 4003–4016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riaz, S.; Riaz, M.; Nazeer, A.; Hussain, Z. On Bayesian EWMA control charts under different loss functions. Qual. Reliab. Eng. Int. 2017, 33, 2653–2665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noor-ul-Amin, M.; Noor, S. Bayesian EWMA control chart with measurement error under different loss functions. Qual. Reliab. Eng. Int. 2021, 37, 3362–3380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaagan, A.A.; Alshammari, A.O.; Khan, I. Performance analysis of Bayesian control chart under variable sample size for industrial application with measurement error. Qual. Reliab. Eng. Int. 2025, 41, 1919–2031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, I.; Noor-ul-Amin, M.; Khan, D.M.; Ismail, E.A.A.; Yasmeen, U.; Rahimi, J. Monitoring the process mean under the Bayesian approach with application to hard bake process. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 48206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Maiti, S.S. A new Bayesian control chart for process mean using empirical Bayes estimates. Reliab. Theory Appl. 2024, 19, 209–217. [Google Scholar]

- Feltz, C.J.; Shiau, J.J.H. Statistical process monitoring using an empirical Bayes multivariate process control chart. Qual. Reliab. Eng. Int. 2001, 17, 119–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erto, P.; Pallotta, G.; Palumbo, B.; Mastrangelo, C.M. The performance of semiempirical Bayesian control charts for monitoring Weibull data. Qual. Technol. Quant. Manag. 2018, 15, 69–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Supharakonsakun, Y. Empirical Bayes prediction for an attribute control chart in quality monitoring. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 160784–160793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raubenheimer, L.; Van der Merwe, A.V. Bayesian control chart for nonconformities. Qual. Reliab. Eng. Int. 2015, 31, 1359–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborti, S.; Human, S.W. Properties and performance of the c-chart for attributes data. J. Appl. Stat. 2008, 35, 89–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Supharakonsakun, Y. Bayesian control chart for number of defects in production quality control. Mathematics 2024, 12, 1903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montgomery, D.C. Introduction to Statistical Quality Control, 6th ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Supharakonsakun, Y.; Jampachasri, K. The comparison of confidence interval estimation methods for parameter using empirical Bayes methods in Poisson distributed data. In Proceedings of the 11th Thai Conference on Statistics and Applied Statistics, Chiang Mai, Thailand, 27–28 May 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Supharakonsakun, Y. Bayesian approaches for Poisson distribution parameter estimation. Emerg. Sci. J. 2021, 5, 755–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legendre, A. New Methods for the Determination of Orbits of Comets; Courcier: Paris, France, 1805. [Google Scholar]

- Gauss, C.F. Least Squares Method for the Combinations of Observations; Mallet-Bachelier: Paris, France, 1955. Original work published 1810. [Google Scholar]

- Norstrom, J.G. The use of precautionary loss function in risk analysis. IEEE Trans. Reliab. 1996, 45, 400–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimnezhad, A.; Moradi, F. Bayes, E-Bayes and robust Bayes prediction of a future observation under precautionary prediction loss functions with applications. Appl. Math. Model. 2016, 40, 7051–7061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S. Mixture of the inverse Rayleigh distribution: Properties and estimation in a Bayesian framework. Appl. Math. Model. 2015, 39, 515–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, L. Inadmissibility of the usual estimators of scale parameters in problems with unknown location and scale parameters. Ann. Math. Stat. 1968, 39, 29–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alevizakos, V.; Chatterjee, K.; Koukouvinos, C. The triple exponentially weighted moving average control chart. Qual. Technol. Quant. Manag. 2021, 18, 326–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burr, J.T. Element Statistical Quality Control, 3rd ed.; Taylor & Francis Group: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).