Remote photoplethysmography (rPPG) aims to capture the subtle color variation in reflected light through a consumer-grade camera, but the reflected light consists of multiple components caused by various factors. The dichromatic reflection model (DRM) [

28] provides a framework for understanding how light interacts with complex surfaces like human skin. The fundamental idea of DRM is that reflected light is composed of two major components, a diffuse component and a specular component, each of which can be further broken down into several sub-components. In the context of skin, a portion of the light penetrates the skin and interacts with melanin, hemoglobin, etc. These interactions cause scattering and absorption; such diffused light is the diffuse component. The unpenetrated light bounces back from the skin’s surface and is called the specular component. The smoothness, hydration, and oil content of the skin affect the intensity and appearance of the specular reflection. Different wavelengths of light interact uniquely with the skin’s deeper layers. For example, the green channel shows the highest absorbance due to its sensitivity to hemoglobin. As a result, subtracting the green channel from the other color channels or some linear combinations of color channels can effectively minimize the specular component, isolating the diffuse reflection. rPPG information lies in the diffuse reflection. Several initial research studies were based on this idea [

10,

18,

29]. Verkruysse et al. [

10] used the fact that the green channel holds strong rPPG components; they eliminated non-periodic components with Butterworth filters and then performed a spectral analysis to extract HR and RR. Poh et al. [

29] proposed Independent Component Analysis (ICA) of all three color channels. In [

30], this work is further improved with detrending filters. ICA-based methods assume that the sources of each reflected component are statistically independent. This might not be true all the time, especially under extreme noise conditions. Similarly, Lewandowska et al. [

31] used principal component analysis (PCA) to eliminate noise. Blind Source Separation (BSS)-based methods are not good at eliminating periodic motion artifacts [

18]. The human heart rate lies in the range of [0.75–4 Hz] (or 42–240 bpm) [

5] and also the frequency of the PPG waveform is the same as the heartbeat frequency [

4]. A band-pass filter with a frequency range of [0.75–4 Hz] effectively removes non-periodic and unlikely rPPG components, but it does not eliminate noise entirely; band-pass filters are used in [

10,

18,

29,

30,

31]. Spatial averaging is the most used technique to eliminate tiny motion artifacts; compared to a single pixel-wise value, the mean value of a bunch of pixels significantly improved the SNR [

10]. SNR may even become better when pixels are chosen from the skin region or ROIs (sources of rPPG). Spatial averaging or average pooling eliminates motion artifacts and facial deformities within an ROI; the larger the ROI’s area, the better the noise cancelation. G de Haan et al. [

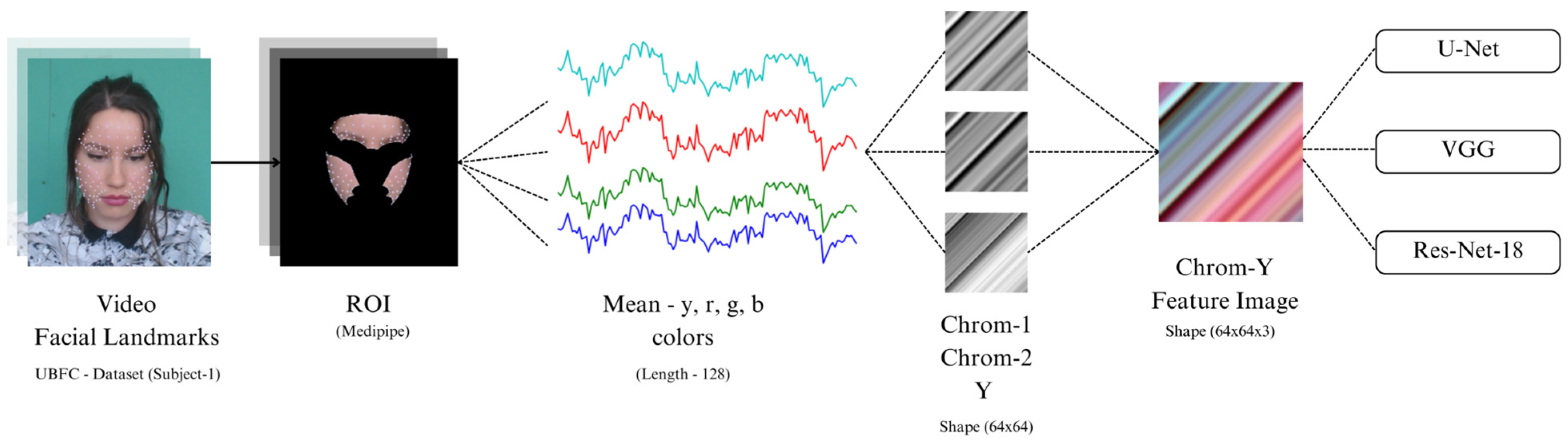

18] (also known as CHROM algorithm), proposed two orthogonal chrominance color spaces (two different linear combinations of RGB) which effectively extract rPPG components; additionally, the algorithm addresses nonwhite illumination by standardizing skin tones using normalized RGB values based on a fixed reference, ensuring consistency across various lighting conditions. This is achieved by normalizing each channel and applying standardized weights. In this paper, we used this algorithm for featurization. Those two chrominances were then divided, leaving behind linear combinations of RGB. Conventional methods for remote photoplethysmography (rPPG) can be broadly divided into two categories: Single-Color Methods and Multi-Color Methods. Due to their high sensitivity to blood volume changes, single-color methods typically focus on a green color channel. These methods employ signal processing techniques like detrending, smoothing, and band-pass filtering to extract physiological signals, as seen in studies [

10,

32,

33]. In contrast, Multi-Color Methods leverage multiple color channels, often all three (red, green, and blue) to enhance accuracy and noise reduction. Some approaches within this category use Blind Source Separation (BSS) for noise elimination, with [

29,

30] utilizing Independent Component Analysis (ICA) and [

31] implementing principal component analysis (PCA). Additionally, studies like [

18,

34] propose combining multiple color channels linearly to improve signal extraction. Deep learning models are good at generalization [

11]. Subtle color variation within the pixels of an ROI is the only useful information for rPPG signal extraction. Featurization is the process of converting raw data into a structured format that can be effectively utilized by deep learning models. This transformation is crucial because handling unprocessed inputs often demands complex models, which require extensive datasets for effective training. Large-scale data is particularly important for complex deep learning networks to learn meaningful patterns and achieve high performance [

35]. Models with fewer parameters cannot capture sophisticated patterns hidden in the raw input. This problem can be mitigated with pre-processed features. RythmNet [

36] proposed a 2D spatial–temporal feature image on YUV color channels; they tested different color spaces including RGB, HSV, and YCrCb and concluded that YUV performed better, with the least RMSE. The YUV color space retained rPPG information more effectively than the other color spaces. Temporal features (raw YUV signals) from multiple non-overlapping ROIs were stacked to form an image of size (n, m, 3); each row of a 2D image in the YUV temporal feature is an ROI. J. Wu et al. [

23] proposed a “Multi-scale spatial–temporal representation of PPG”. Their feature image was similar to [

36], but unlike RhythmNet, they utilized all possible sets of ROIs, and each row of their 2D image corresponded to some non-null subset of ROIs. X. Niu et al. [

24] used a similar approach but included two color spaces (RGB and YUV) in their feature image. Both refs. [

23,

24] build their feature images with raw RGB and YUV colors, expecting the CNN to figure out hidden patterns. R. Song et al. [

37] constructed their feature image, where each row was a pre-processed signal from different time intervals, and each row was a signal from overlapping time intervals. Instead of raw color traces, they pre-processed raw signals with the CHROM [

18] algorithm. Overlapping intervals are effective in minimizing the impact of brief, high-intensity noise. Even if one interval is heavily affected by noise, the other intervals can still offer reliable information, ensuring more accurate overall results [

38]. Although refs. [

23,

24] focus on face liveness detection, similar methods are also found in heart rate estimation tasks in [

39,

40]. References [

12,

16,

17] utilized attention mechanisms with CNNs, LSTM, and RNN architecture. Deep learning methods can be broadly classified into two categories: image-based [

23,

24,

36,

37,

40] and attention-based [

12,

16,

17]. The rPPG waveform contains information on many vital parameters such as HR, RR, and SpO2. Different DL models can be trained to predict each parameter separately, but the optimal approach is to have a DL model for rPPG signal reconstruction and have lightweight models to predict all possible parameters. M. H. Chowdhury et al. [

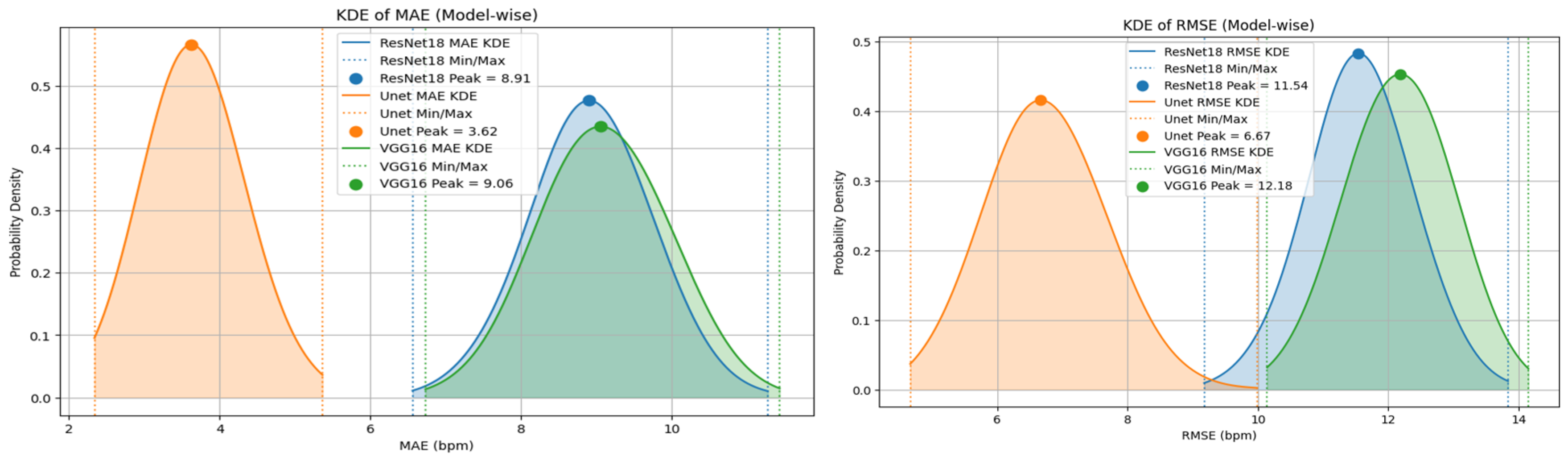

41] used an encoder–decoder model for rPPG waveform estimation and heart rate was estimated with the peak value of Power Spectral Density (PSD). Pearson’s Correlation Coefficient (PCC), Dynamic Time Warping Distance (DTW), and RMSE were used to analyze the model performance. For a heart rate estimation task, mean absolute error (MAE) is enough to analyze model performance, but for a waveform estimation task, wave-similarity metrics are appropriate. M. Das et al. [

42] utilized a scalogram of RGB traces as a feature image to estimate the waveform. In rPPG, the wavelet transform decomposes signals into multiple scales, providing both time and frequency information; it is utilized in [

42,

43,

44]. Early approaches utilized color channels and statistical tools like ICA and PCA to capture blood volume changes, focusing on minimizing noise and isolating diffuse reflections. However, these methods had limitations under complex noise conditions. Modern deep learning models, such as those using spatial–temporal features and attention mechanisms, have shown better performance. B.-F. Wu et al. [

45] analyzed the CHROM algorithm with fluctuating brightness and concluded that sudden illumination fluctuation degrades SNR and also increases error in HR estimation. Z. Yang et al. [

15] investigated conventional methods and deep learning models under different illumination; the performance of deep learning models was poorer than that of conventional methods under variable lighting conditions.