Abstract

The acoustical modelling of multilayered systems is crucial for researchers and engineers aiming to evaluate and control the behaviour of complex media and to determine their internal properties. In this work, we first develop a forward model describing the propagation of acoustic waves through various types of materials, including fluids, solids, and poroelastic media. The model relies on the classical theoretical frameworks of Thomson and Haskell for non-porous layers, while Biot’s theory is employed to describe wave propagation in poroelastic materials. The propagation is mathematically treated using the transfer matrix method, which links the acoustic displacement and stress at the extremities of each layer. Appropriate boundary conditions are applied at each interface to assemble all local matrices into a single global matrix representing the entire multilayer system. This forward model allows the calculation of theoretical transmission coefficients, which are then compared to experimental measurements to validate the approach proposed. Secondly, this modelling framework is used as the basis for solving inverse problems, where the goal is to retrieve unknown internal parameters, such as mechanical or acoustic properties, by minimizing the discrepancy between simulated and experimental transmission spectra. This inverse problem approach is essential in non-destructive evaluation applications, where direct measurements are often unfeasible.

1. Introduction

Acoustical multilayered systems play an essential role in the design of materials and structural mechanics used for sound insulation and absorption across diverse applications, including architectural acoustics, automotive and biomedical engineering, non-destructive testing, seismology, industrial noise control, etc. [1,2,3,4]. More recently, ultrasonic waves have also been used for the non-destructive evaluation of lithium-ion batteries, allowing for the assessment of internal states such as the state of charge, SoC, and state of health, SoH, by analysing wave propagation through the different layers of materials composing the battery. These systems are characterized by their ability to manage sound transmission through the strategic arrangement of different types of layers: porous, solid, and fluid layers.

The characterization and estimation of some internal parameters, such as the mechanical and acoustic properties of materials in a multilayered system, are often not accessible through direct measurement [5,6]. In this context, non-destructive testing (NDT) methods based on ultrasonic waves provide an effective alternative. This approach relies on the analysis of the waves’ propagation through the different layers of the system, making it possible to extract valuable information on properties such as wave speeds, elastic moduli, density, and damping coefficients. To solve this inverse problem, which involves identifying parameters from experimental measurements (transmission and reflection spectra, amplitudes, and time of flight), a genetic algorithm can be employed, as has been widely studied in [5,7,8,9]. This optimization algorithm, inspired by the mechanisms of natural evolution, explores the space of possible solutions by selecting, crossing, and mutating sets of parameters to minimize an objective function representing the distance between the measured data and the results simulated by a direct model. The combination of ultrasonic modelling, inverse problem solving, and genetic optimization thus enables robust, non-intrusive identification of material properties, even in complex multilayered configurations.

The development and modelling of wave propagation through multilayered systems have been of interest to researchers. This interest began with the foundational work of Thomson [10] and Haskell [11], which focused on non-porous materials such as elastic solid and fluid materials. Subsequently, the concept of a poroelastic medium was introduced by Biot [12,13], who established the theoretical framework for complex wave propagation in fluid-saturated porous media [14].

Widely used methods for analysing and predicting the acoustic performance of a multilayered system with an arbitrary number of layers are based on matrix formulations [14], which include the transfer matrix method (TMM) [10,11,15,16]. This technique relates the pressure and velocity at one interface of a layer to those at the other interface, as is also described in [17]. For a porous layer, formulations based on Biot’s theory [12,13,18] have been used in models such as those in [19,20,21,22]. The global matrix method (GMM) was proposed for the first time in [23,24] for isotropic solid layers, then validated and implemented in [25,26,27,28]. This technique involves transforming the equations for individual layers into a unified global matrix, which includes all the unknowns associated with the boundary conditions. A review of the GMM and its comparison with the TMM is presented in [29].

Kausel and Roesset [30] proposed a reformulated global matrix technique in which the system global matrix is derived for isotropic solid layered media using the stiffness matrices of the layers instead of their transfer matrices. A stiffness matrix establishes the relationship between the stress components and the displacement components at both interfaces of a layer. Consequently, this method yields the total displacements and stresses directly, rather than the amplitudes of the waves [14,31].

More recently, the modelling of porous media has significantly improved the predictive accuracy of acoustic simulations. Biot’s poroelastic theory [12,13] and its subsequent extensions have formed the theoretical basis for understanding sound wave propagation in porous materials. By accounting for physical parameters such as porosity, tortuosity, and flow resistivity, these models allow for a detailed analysis of the acoustic behaviour of porous layers within multilayer configurations [32].

Nevertheless, accurate modelling of complex multilayer systems remains a challenge, especially under various boundary conditions between interfaces and at higher frequencies [33]. This work aims to present the propagation of a plane wave through different media using the transfer matrix method (TMM). The proposed modelling approach is general, as it can be directly applied to arbitrary layered media configurations. The theoretical foundations of the TMM approach are first reviewed. Then, the transfer matrices for different types of layers are presented. Various combinations of interface matrices, based on the boundary conditions between two adjacent layers, are also detailed to couple all transfer matrices into a single matrix that characterizes the acoustic field of the multilayered system. The proposed methodology is validated against experimental results and some published works.

The organization of this paper is as follows. After this introduction, which reviews the literature in this field, a brief presentation of the mechanics in an infinite medium, particularly in a poroelastic medium, is given in Section 2. Then, a TMM used to model a multilayered system based on transfer matrices is presented in Section 3. An inverse problem resolution algorithm and the experimental setup are described in Section 4 and Section 5, respectively. Section 6 presents a validation of the proposed approach by comparing the theoretical results with experimental measurements. Finally, a conclusion is drawn in the last section.

2. Mechanics in an Infinite Medium

2.1. Acoustic Waves in Fluid and Solid Media

In general, two types of acoustic waves can propagate through a medium: longitudinal (L) waves and shear (S) waves, depending on the nature of the material. Longitudinal waves propagate in the same direction as the wave incidence, while shear waves propagate perpendicular to that direction. In fluids, only longitudinal waves can propagate. In solid media, both longitudinal and shear waves can exist. In porous materials, three types of waves may propagate: two longitudinal waves (fast and slow) and one shear wave. The fast longitudinal and shear waves travel through the solid frame of the porous material, whereas the slow longitudinal wave propagates through the fluid phase.

We denote by ф the scalar potential and by ѱ the vector potential, associated, respectively, with the longitudinal and shear waves propagating in a solid medium, from which the acoustic velocity v is derived:

with

Considering the πxz plane, we can describe the directions of various waves propagating through the system. At each interface, a given wave splits into two components projected onto the πxz plane: one propagating forward (in the direction of increasing z) with amplitude denoted a+, and the other propagating backward (in the direction of decreasing z) with amplitude denoted a−. kzL,S, K are the projections of the wave acoustic vector of a longitudinal (kL) or shear (kS) wave on the (z) axis and (x) axis, respectively.

where the operators kL and kS can be calculated by Equations (6) and (7) below:

where w is the angular frequency, is density and are the lamé coefficients of the medium. are the wave velocity of the longitudinal and shear waves, respectively, in the medium.

2.2. Acoustic Waves in Porous Media

A porous material is a biphasic medium composed of a solid framework, also referred to as the matrix or skeleton, within which pores saturated with a fluid are distributed. The propagation of acoustic waves through such a medium induces dynamic interactions between the solid and fluid phases, endowing the material with atypical acoustic properties compared to conventional homogeneous media [34]. When a porous material has an elastic structure, the acoustic waves propagate through both the solid frame and the fluid filling the pores. This situation was studied by Biot [12,13], as we discussed before in the introduction, who developed a model describing how the solid and fluid move separately but also interact with each other. Biot’s model has become the standard approach for understanding wave behaviour in fluid-saturated porous materials. Researchers like Attenborough [35,36], Johnson [19,20,37], Champoux and Allard [38], and Lafarge et al. [39] later improved the model by introducing new parameters that allow it to describe a wider range of frequencies.

In an isotropic porous medium, three distinct wave propagation modes are predicted in two dimensions: two longitudinal waves and one shear wave. The first longitudinal wave, known as the fast wave, propagates more rapidly than the second one, which is referred to as the slow wave or second and travels at a lower speed.

The acoustic field in the poroelastic material can be described using two scalar potentials and one vector potential (, and ), given in Equations (8) and (9) and represent the amplitudes of the six waves incident and reflected within the poroelastic layer. The potentials () present the frame displacement potentials of the two longitudinal (compressional) waves, fast and slow, respectively. the is the frame displacement potential of the shear wave [17].

with i = 1, 2.

The displacement potentials of the fluid are related to those of the frame by Equations (10) and (11):

and

with the ratio µ [17,40]

and

The term kLi is the wave number of the i compressional wave. P, Q, and R are the elastic coefficients of the porous medium, using Formulations (14)–(16). And the terms and are the effective densities of the porous material, where and correspond to the densities of the solid frame and the fluid, respectively, while represents the coupling density between the solid part and the fluid within the porous medium [12,13,17,40].

where and is the porosity of the medium.

References [12] and [41] established relationships between the stresses and the strain tensors in the solid frame and fluid phase by using the four elastic parameters (P, Q, R, and N), where P and N (also noted Sh in some studies) represent the effective longitudinal and shear modulus of the porous material, respectively. R corresponds to the pressure required to inject a given volume of fluid into the material while keeping the total volume constant. Q characterizes the coupling of volume change between the solid frame and the fluid [14]. The terms and are the compressibility modulus of the matrix and the fluid of the medium, respectively. while the and N representing the bulk and shear modulus, are calculated using a homogenization from Kuster and Toksôz [42,43,44].

The effective densities are expressed as [12,13,17]:

where and are the solid frame and the fluid density, respectively, and represents the dynamic tortuosity of the material, which is calculated using the Johnson model [37].

3. Proposed Approach to Model Multilayered Structures

3.1. Transfer Matrix Method (TMM)

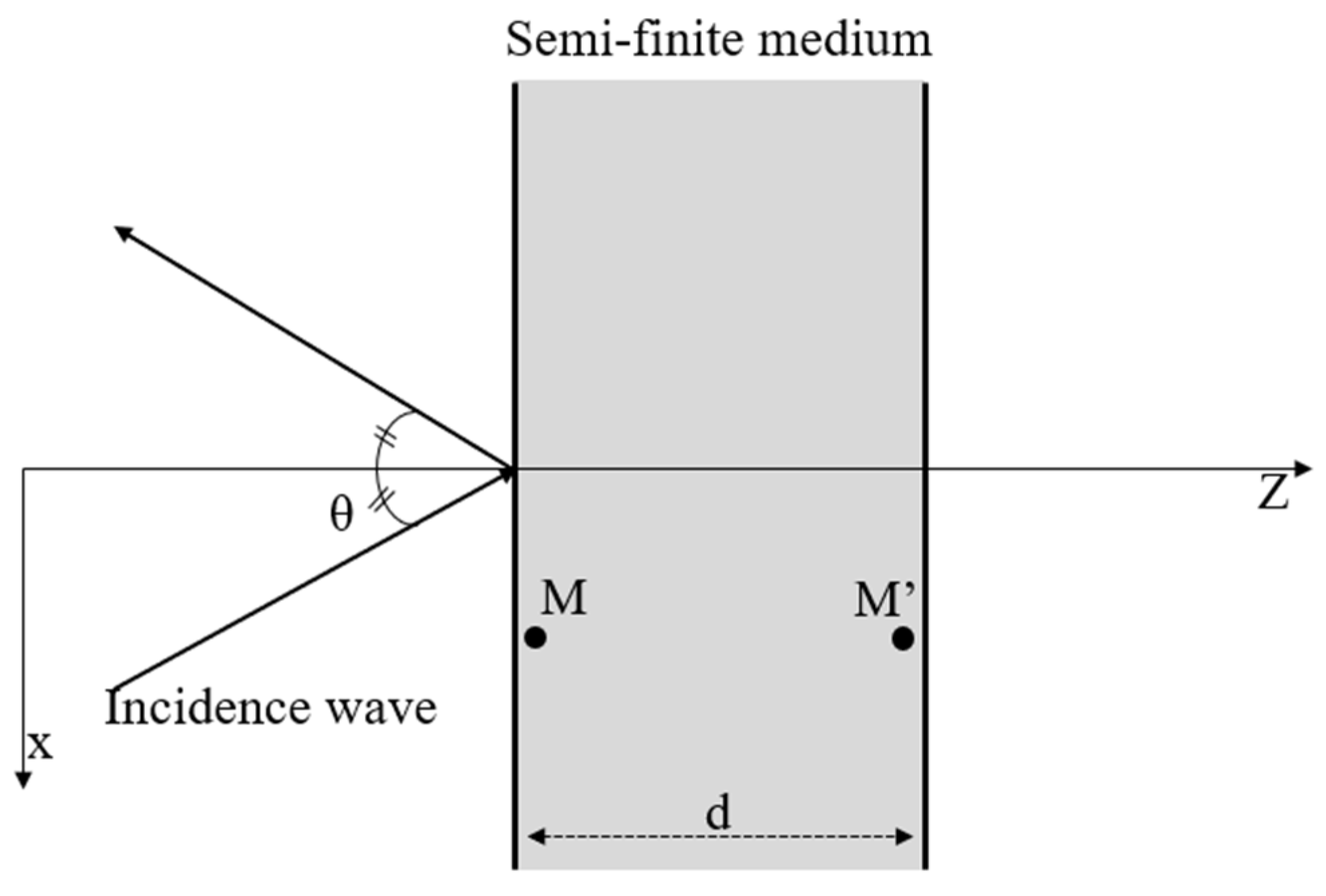

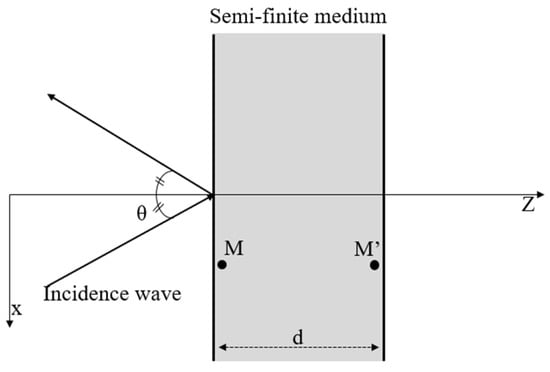

The transfer matrix method (TMM) is a technique used to model waves propagating through multilayer systems. Figure 1 illustrates a plane acoustic wave incident on a material of thickness d at an angle . The problem is defined in two dimensions, within the (x, z) plane of incidence. Depending on their nature, diverse types of waves may propagate within the material. For each wave propagating in the semi-infinite medium, the x-component of the wave number is equal to that of the incident wave, denoted by K.

where ki is the incident wave number. Sound propagation in the layer is represented by a transfer matrix [T] such that:

Figure 1.

Plane wave incident on a material of thickness d.

Points M and M′ are positioned near the front and back faces of the layer, respectively. The components of the vector V(M) represent the variables describing the acoustic field at point M within the medium, i.e., the particle velocities and stresses. The transfer matrix [T] depends on the layer’s thickness d and the physical properties of the material.

Let us denote the sum and difference notations of the wave’s amplitudes (with the subscript i standing for L or S).

Thus, the vector V(M) can be expressed in terms of the wave amplitudes by multiplying them by a matrix . The form and order of the matrix depend on the nature of the material.

The inverse matrix can be used to relate the wave amplitudes to the components of the vector V (such as particle velocities and the stresses) at the same point.

The matrices and depend only on the mechanical properties of the medium.

Equation (26) corresponds to the propagation matrix P that characterizes the acoustic field through a homogeneous layer, linking the wave at point M to that at M′, as shown in Figure 1 and described in [15,17].

This can give the transfer relation for Si and Di from z to z + d inside the same layer.

So, after Equations (21) and (24–27), we note that the transfer matrix [T] is expressed by the matrices , and P:

3.1.1. Fluid Layer Model

In the fluid medium, it is only the longitudinal wave that can propagate. So, to describe this acoustic field, we need to determine the velocity v and the stress σ at the first interface (point M):

Using the formalism of Allard and Cervenka (1991) [15,17], the velocity and stress of the wave are calculated by the expressions below [15,17]:

From Equation (2) with notations (22) and (23), Equations (30) take the following matrix form below:

where .

3.1.2. Solid Layer Model

Unlike a fluid medium, where only longitudinal waves can propagate, an elastic solid medium supports two types of waves: longitudinal (L) and shear (S) waves. The acoustic field in the solid material can be described using four amplitudes of the potential (ф, ѱ): , and represent the amplitudes of the four waves incident and reflected within the solid layer.

At each point within the solid layer, the following quantities must be calculated: , , , and . The first two represent the velocity components along the x-axis and z-axis of the πxz plane, respectively, while the latter two correspond to the stress components at point M along the same axes. These velocities and stresses are expressed as in [15,17], with detailed expressions provided in Appendix A II.

After Equations (32) and (21), we can observe that for an elastic solid layer, the transfer matrix [T] is a 4 × 4 matrix. So, to obtain this matrix that can be connected to the extremity of the solid layer, it is necessary to describe the quantities , , , and in terms of wave amplitudes. We can find four combinations based on the sum and difference notations presented in Equations (22) and (23). Let us denote the amplitude matrix , with the superscript L and S referring to the longitudinal and shear wave, respectively.

The matrix that describe the velocities and stresses in terms of wave amplitudes A will be presented in Appendix A II:

3.1.3. Poroelastic Layer Model

At this stage, to describe the acoustic field in the porous layer, based on the TMM, we need to determine the velocity v and the stress σ components at the interface (at any point M of the material, as shown in Figure 1).

At each point within the poroelastic layer, it is necessary to calculate the previous quantities in Equation (34). The expressions of velocities and stresses are given in Appendix A III [17].

From Equations (32) and (21), we can observe that the transfer matrix [T] for a poroelastic layer is a 6 × 6 matrix. So, to derive this matrix, which connects the two boundaries of the porous medium, it is useful to express the quantities , , , , and in terms of wave amplitudes. Six combinations can be formed using the sum and difference notations, presented in Equations (22) and (23). Let us denote the amplitude matrix as , with the subscript and S representing the i-th longitudinal (with i = 1, 2) and shear wave, respectively.

In the same way, the matrix describing the velocities and stresses as functions of the wave amplitudes A is given in Appendix A III:

3.2. Boundary Conditions at the Interface Between Different Layers

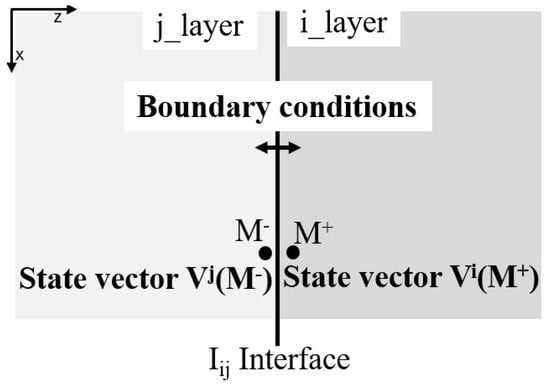

Once the transfer matrix has been established, we observe that the matrix order is different from one medium to another. Also, the idea of using the TMM for modelling a multilayered system is based on multiplying the transfer matrix of such layers throughout the system. For that, we should add the wave interaction and the continuity of the displacement and the stress vectors between interfaces.

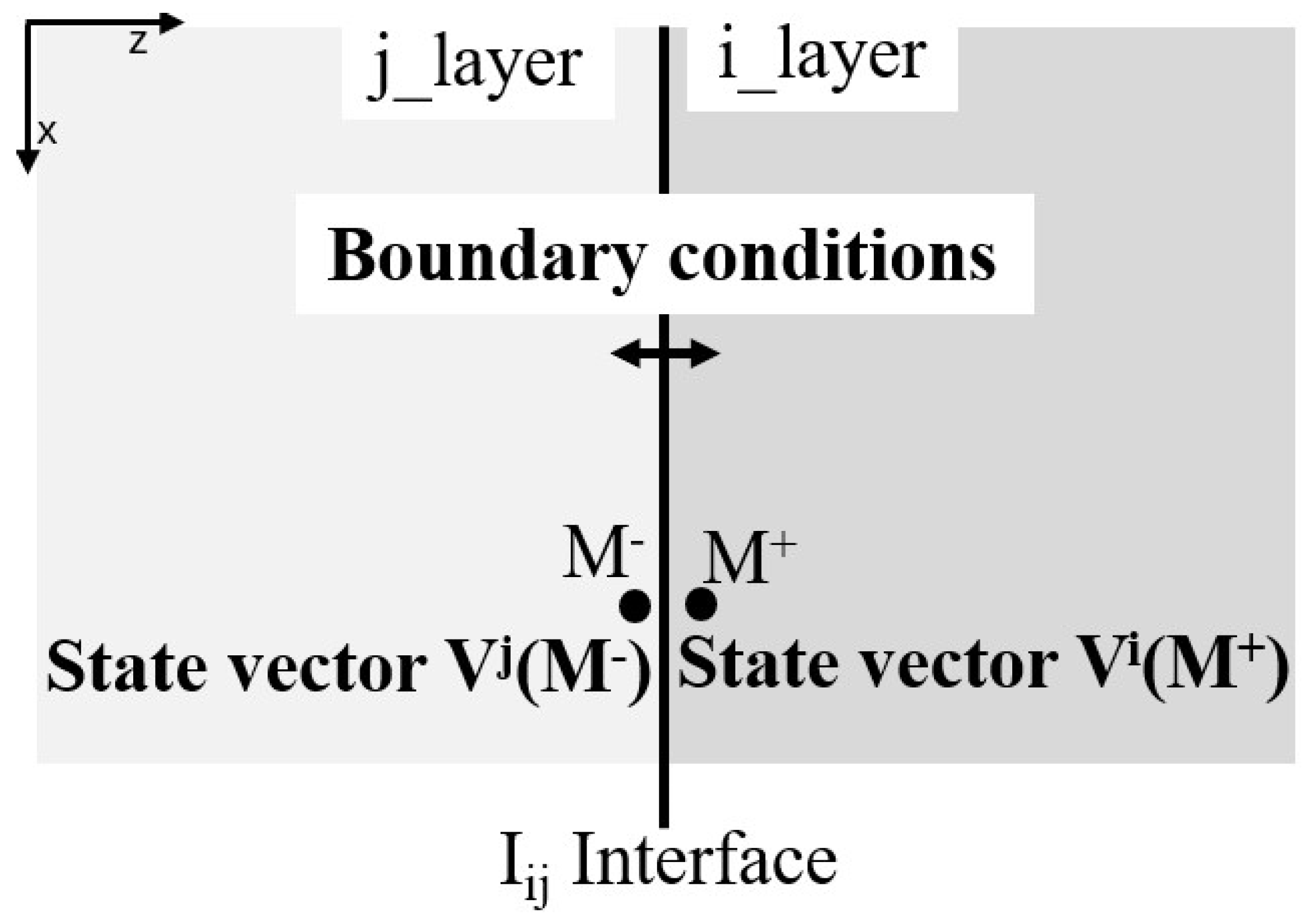

The interface matrix I’s order is determined by the boundary conditions and the type of the two adjacent layers.

The superscripts ‘+’ and ‘−’ denote the right and left sides of the interface at point M, respectively, while the subscripts i (f, s, p) and j (f, s, p) indicate the first and second types of layers, respectively, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Boundary conditions and state vector at an interface.

3.2.1. Two Layers of the Same Nature

If the two parts are not porous layers, the interface matrix I between two layers of the same nature simply equals the identity matrix: I2×2 for a fluid layer and I4×4 for elastic solid layers. This is because of the continuity of all the components of the acoustic field. However, if both layers are composed of porous materials, the continuity conditions are influenced by their respective porosities [17]:

In this case, the interface matrix I is a 6 × 6 matrix constructed on the basis of Equation (37):

with , representing the porosity of the first and the second porous layer, respectively.

3.2.2. Two Layers of Different Nature

When the two layers have different natures, the interface matrix I is derived based on the boundary conditions at the corresponding interfaces. In this work, we list the well-known types of interfaces: elastic solid–fluid, elastic solid–poroelastic and poroelastic–fluid interfaces. The term is the porosity of poroelastic layer.

Elastic solid–fluid interface:

The continuity conditions are

So, the interface matrices [Isf] and [Ifs], can be written based on Equation (40), as below:

Elastic solid–poroelastic interface:

The continuity conditions are [17]

The interface matrices [Isp] and [Ips], can be written based on Equation (41):

with the being the medium porosity.

Poroelastic–fluid interface:

The continuity conditions between the poroelastic–fluid layers are

So, the interface matrix Ipf and Ifp are

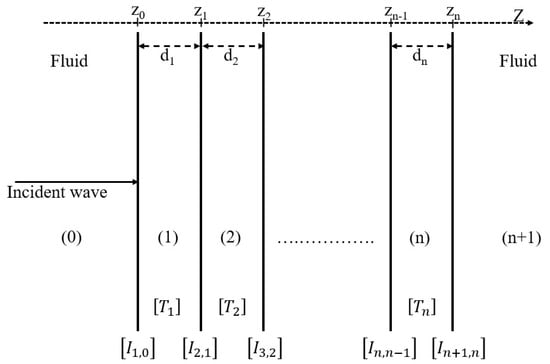

3.3. Coupling the Transfer Matrices

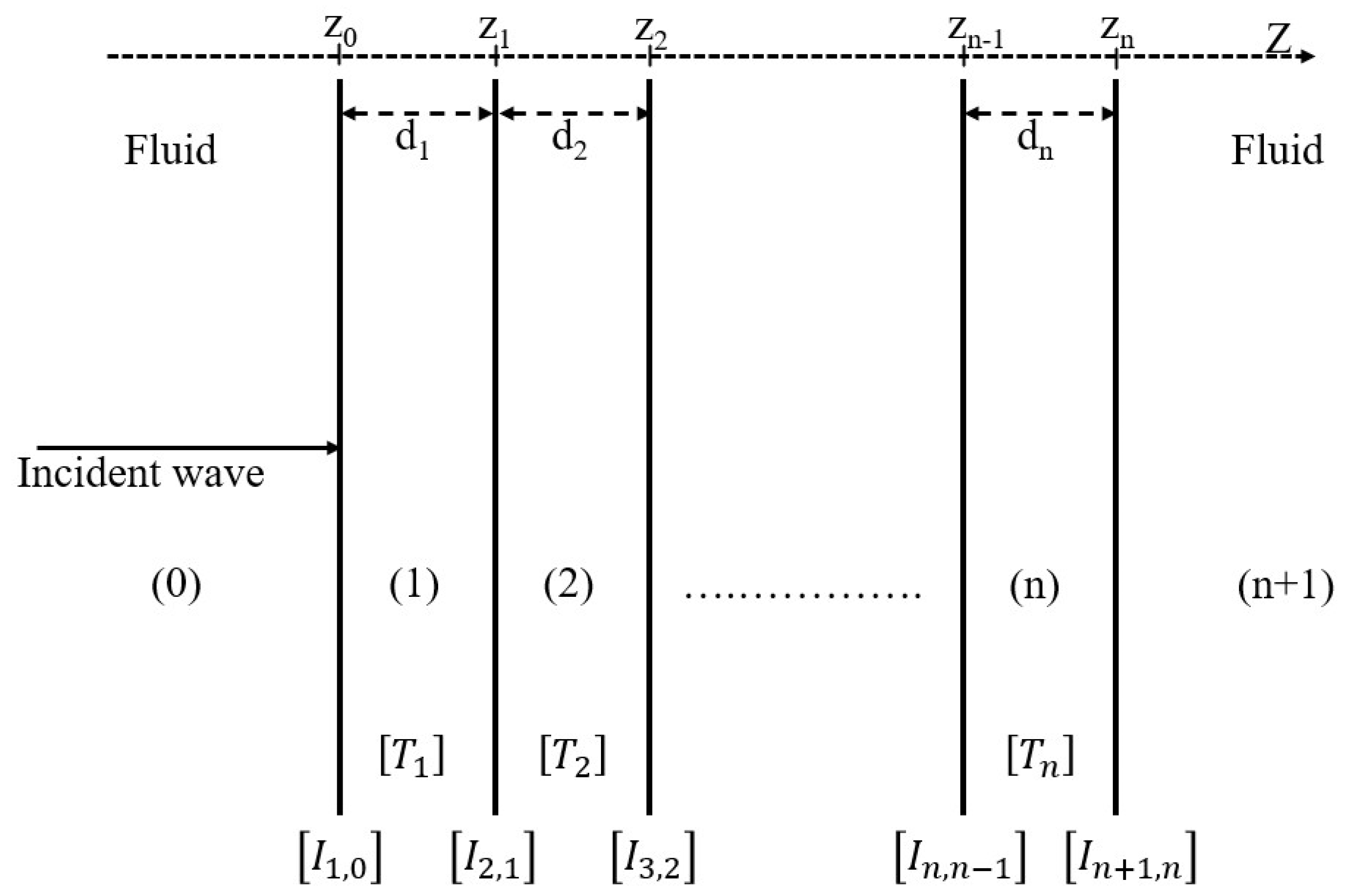

Let us consider a system composed of n layers, as depicted in Figure 3. The TMM aims to combine the transfer matrices of individual layers with the interface matrices , resolving the challenge of handling matrices of varying dimensions while also maintaining the continuity of acoustic fields across the interfaces. This approach results in a global matrix that links the two ends of the system.

Figure 3.

Multilayered structure consisting of n layers.

The global matrix of the system is calculated as follows:

where di is the thickness of layer i.

The transfer matrix of each layer depends on its thickness di.

The inverse matrix coefficient expressions for each type of medium are presented in Appendix A.

In this work, the proposed multilayered system is surrounded by semi-infinite fluid layers, and the incident wave is normal to its surfaces. With this assumption, we can neglect the shear waves, so the vector potential field ѱ is null and the displacement u can be written as . The global matrix in this case is about 2 × 2 dimensions.

From Equations (21), (29) and (45), we can connect the acoustic field between the ends of the system, as expressed below:

and

Using the wave amplitudes at each interface, the transmission and reflection coefficients throughout the system can be computed [5].

- -

- At the first interface:

- -

- At the last interface:

Where , are the incident wave and reflected wave amplitudes at the input of system, respectively, while is the transmitted wave amplitude at the output. These amplitudes are connected by the matrix G.

So,

Equation (50) can be rewritten to connect the transmitted and reflected waves, which can be measured, to the incident wave .

The transmission and reflection coefficients can be calculated as follows:

4. Inverse Problem Resolution

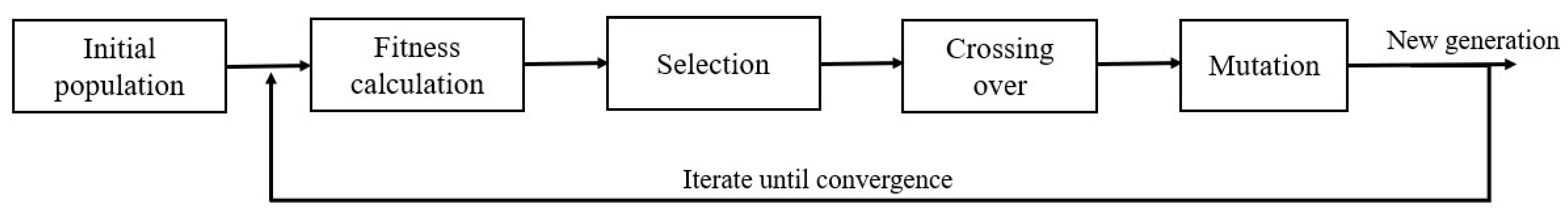

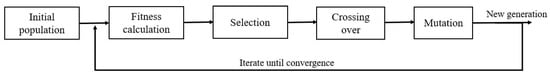

This optimization method of inverse problem resolution involves determining the unknown properties of a medium based on experimental measurements of wave propagation [45]. This type of problem is often complex and nonlinear. The genetic algorithm GA was introduced by Holland [46], inspired by the principles of natural evolution. It operates by generating a population of candidate solutions (parameter sets), which evolve through processes of selection, crossover, and mutation to optimize the objective function. A schematic of a simple genetic algorithm process is illustrated in Figure 4. This function evaluates the discrepancy between the experimental data (e.g., transmission/reflection spectra or time-of-flight measurements) and the results produced by a forward model simulating acoustic wave propagation.

Figure 4.

Schematic of a simple genetic algorithm process.

Compared to gradient-based methods, the genetic algorithm inversion method covers a wider search space to find solutions. Furthermore, a recent study shows that work using a genetic algorithm yields slightly more accurate results than those obtained with particle swarm optimization, despite a higher computational load [47]. Thanks to its ability to efficiently explore complex parameter search spaces and avoid local minima, the genetic algorithm proves particularly well-suited to the robust and reliable identification of acoustic parameters, especially in heterogeneous or multilayered media.

Two key references in this field are the works of Goldberg [48] and Michalewicz [49].

The algorithm begins with the random generation of an initial population of individuals, every individual represents a candidate solution, encoded as a vector of unknown physical parameters to be optimized (e.g., density, wave speed, thickness, etc.).

where gini is an initial member (genome) of the population, bounded by gmin and gmax. The factor r is a random value.

The second step is fitness: each individual is evaluated using a cost function that quantifies the difference between theoretical data obtained from a forward wave propagation model (transmission spectra in our case) and experimental data. A common cost function is the sum of squared errors over the set of measured values [5,45]:

where x is the parameter vector of the individual and N is the total number of points of transmission measurements.

After evaluating the individuals, the algorithm applies evolutionary operators to guide the search toward optimal solutions. Selection favours fitter individuals as parents, using methods like tournaments or roulette-wheel selection, as discussed in [48], to balance performance and diversity. Selected parents undergo crossover to generate offspring by mixing their genetic material, using strategies such as single-point or uniform crossover. This promotes the exploration of new solution spaces [50,51].

To prevent premature convergence, mutation is applied with low probability, introducing random changes to maintain diversity and escape local optima. The new generation is then formed, either by fully replacing the old population or by preserving top performers (elitism). This iterative process of selection, reproduction, and replacement continues until a stopping condition is met.

The input parameters of the genetic algorithm are configured individually for each optimization described in the following sections.

5. Experimental Setup

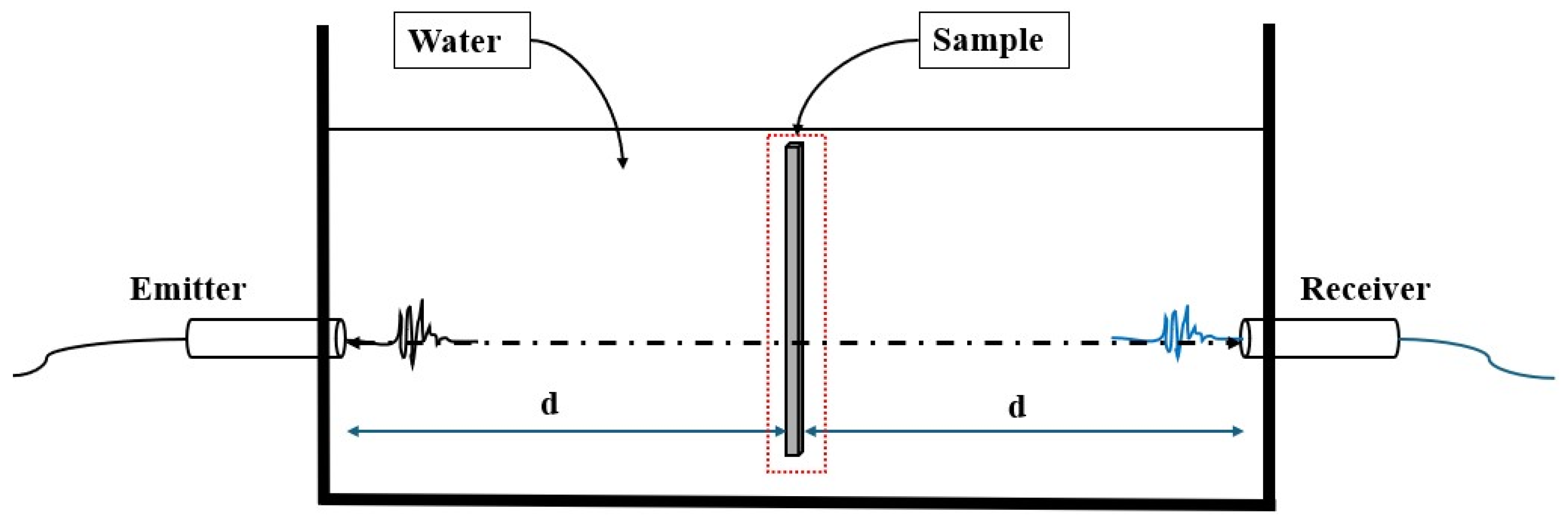

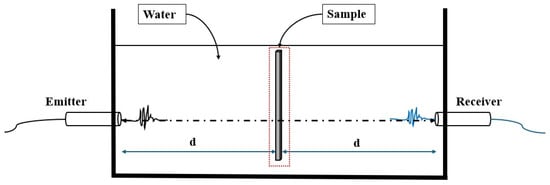

In this work, an insertion–substitution method is used to validate our theoretical model and the optimization algorithm discussed in the above section with experimental data. Two transmitted wave measurements are conducted: one in the immersion medium alone (water in our case), and another after the sample is inserted. The effects of water attenuation, diffraction, and both transducer transfer functions will be compensated for [52]. Figure 5 illustrates the experimental setup.

Figure 5.

Insertion–substitution method: experimental setup.

We used two similar transducers to transmit (T) and receive (R) the acoustic wave with a centre frequency of 3.5 MHz. They are positioned perpendicular to the surface of the tested plate. The distance between the transmitting and receiving transducers (T/R) is approximately L = 2 d = 14 cm.

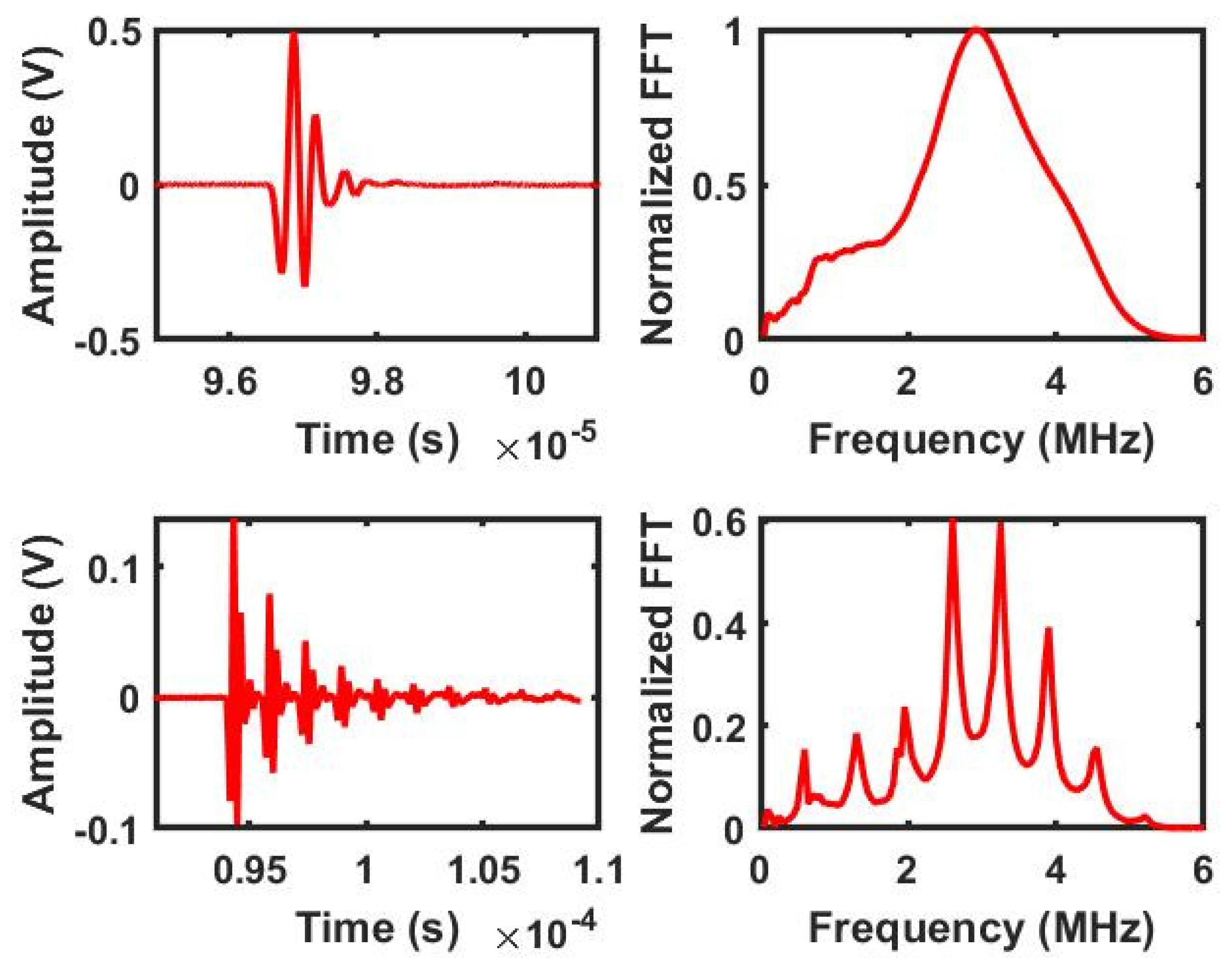

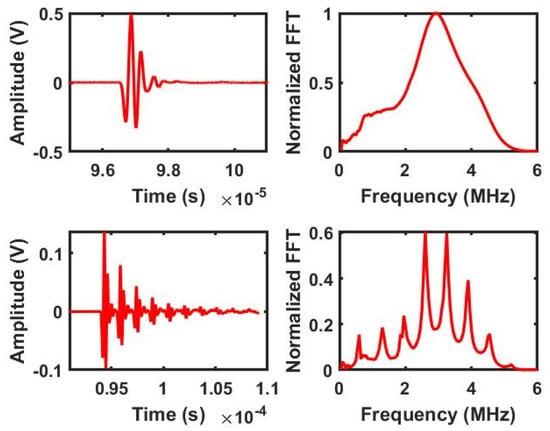

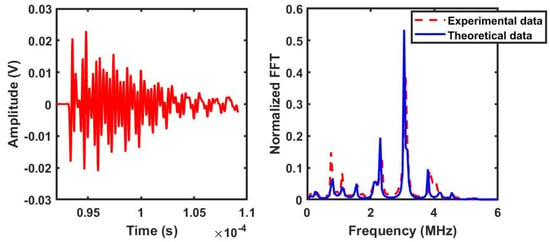

Figure 6 shows the measured transmitted waves with and without the sample, in both the time and frequency domains. Experimentally, the maximum amplitude of the transmitted spectrum is observed near 3 MHz. This value will be used in the following section to validate the theoretical model and the proposed genetic algorithm for optimization.

Figure 6.

Temporal and spectral representations of the reference signal in water (top) and the transmission measurement through an aluminium plate (bottom).

6. Validation of the Proposed Approach

6.1. Measurements on Aluminium Plate

To solve the inverse problem, a genetic algorithm (GA) was employed using the MATLAB® optimization toolbox (R2025b). In this study, the measurement of the transmission wave through the aluminium plate will be used to estimate the thickness, the density, and the wave speed in the plate (unknown parameters) using the inverse problem solving discussed above. Table 1 presents the physical properties of materials used in this work based on the literature [53].

Table 1.

Physical parameters of the materials.

To ensure proper convergence or a near-optimal solution of the genetic algorithm (GA), we tried to configure the input parameters. For each test, we varied the number of generations for the same size of population. We fixed the mutation rate at 20%, and the crossover fraction was set to 0.5, to ensure a good mix of genetic information between individuals. Additionally, to preserve the best candidates across generations, an elite count of 2 individuals was retained. The maximum number of stall generations was set to 50, preventing endless iterations when the population stops evolving significantly.

Different population sizes of 10, 50, and 100 individuals were used, with the number of generations beginning at 100, 500, and 1000 for different tests. The acoustic parameters were retrieved by comparison between the theoretical and experimental spectrum data, normalized by the maximum amplitude of the reference signal spectrum.

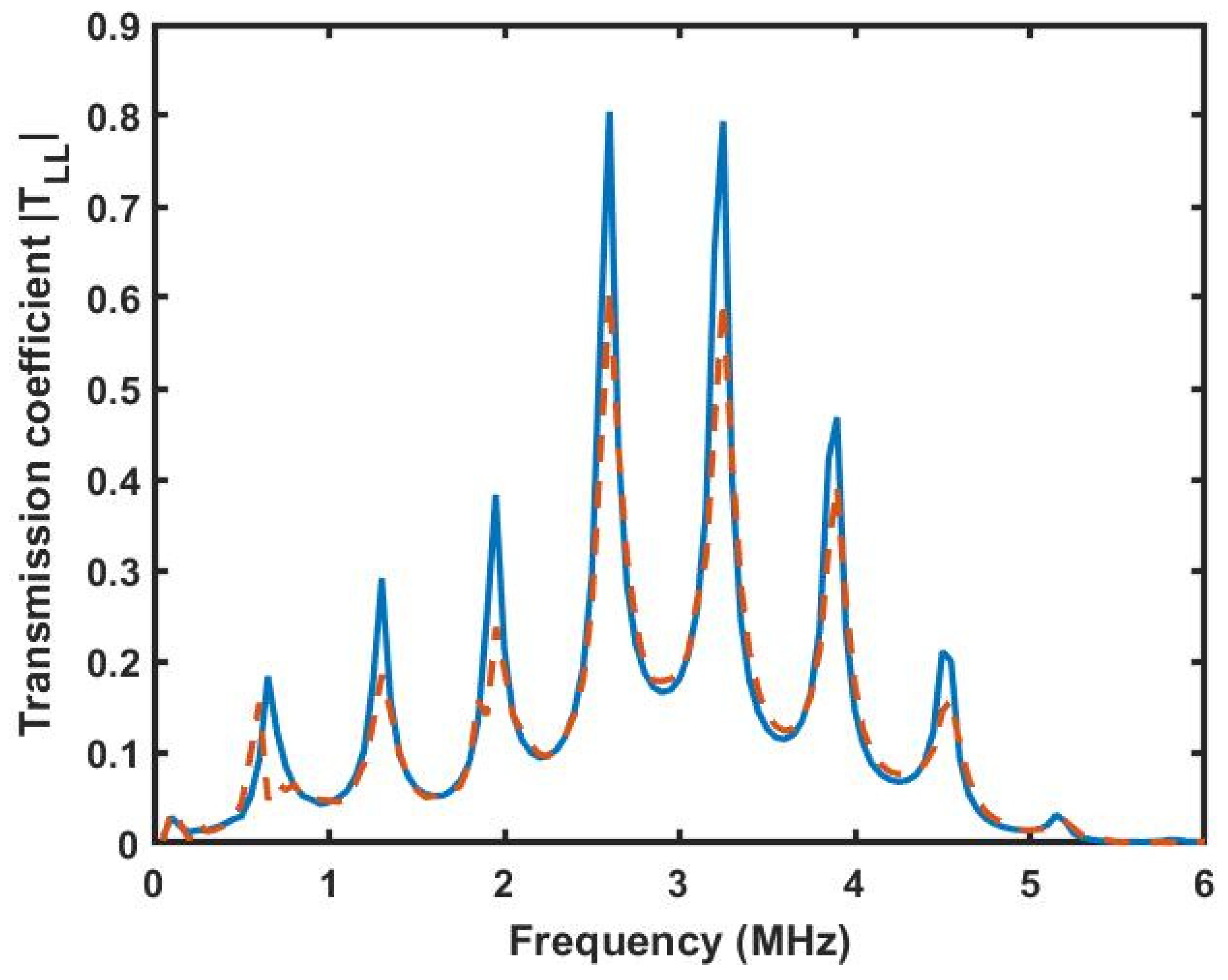

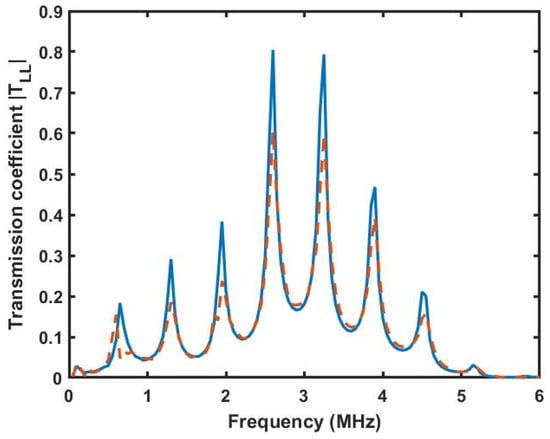

Table 2 summarizes the optimization outcomes obtained for different genetic algorithm settings in terms of population size and number of generations, evaluated over 50 iterations. The thickness remains highly accurate across all cases, with mean values close to 4.97–4.98 mm and a minimum error of 0.02% for a population size of 50 and 500 over generations. The wave speed exhibited slightly higher variability, ranging from 6380 to 6498 m/s, with errors between 0.48% and 2.33%, showing improved convergence for larger populations. In contrast, the density parameter remained stable around 2898–2899 kg/m3, with errors consistently between 3.3% and 3.6%, indicating lower sensitivity to the optimization settings. These results highlight that increasing the population size enhances convergence for thickness and wave speed, while density estimation is less influenced by the algorithm parameters. Figure 7 illustrates the absolute theoretical transmission spectrum calculated using the recovered data set in the forward TMM model developed for wave propagation through the system, compared with the experimental data. The result shows a good agreement for the configuration of the GA used in the end test, providing sufficient iterations for convergence toward a best solution. We will use this configuration for all optimizations proposed below.

Table 2.

Retrieved parameters obtained from the GA for different population sizes and numbers of generations, evaluated over 50 iterations.

Figure 7.

Transmission coefficient at normal incidence. Theory (solid blue line) and experimental (red dotted line).

6.2. Measurements on Multi-Slabs

In this section, the GA was applied to a multilayer system consisting of two closely spaced slabs, one made of steel and the other of glass, immersed in water using the experimental setup shown in Figure 5. A thin water layer separated the two slabs. The acoustic wave propagated through the system in the following sequence: water–steel–water–glass–water. The attenuation occurring in the outer water layers was corrected, as described in [52]. The physical properties of the materials are summarized in Table 1.

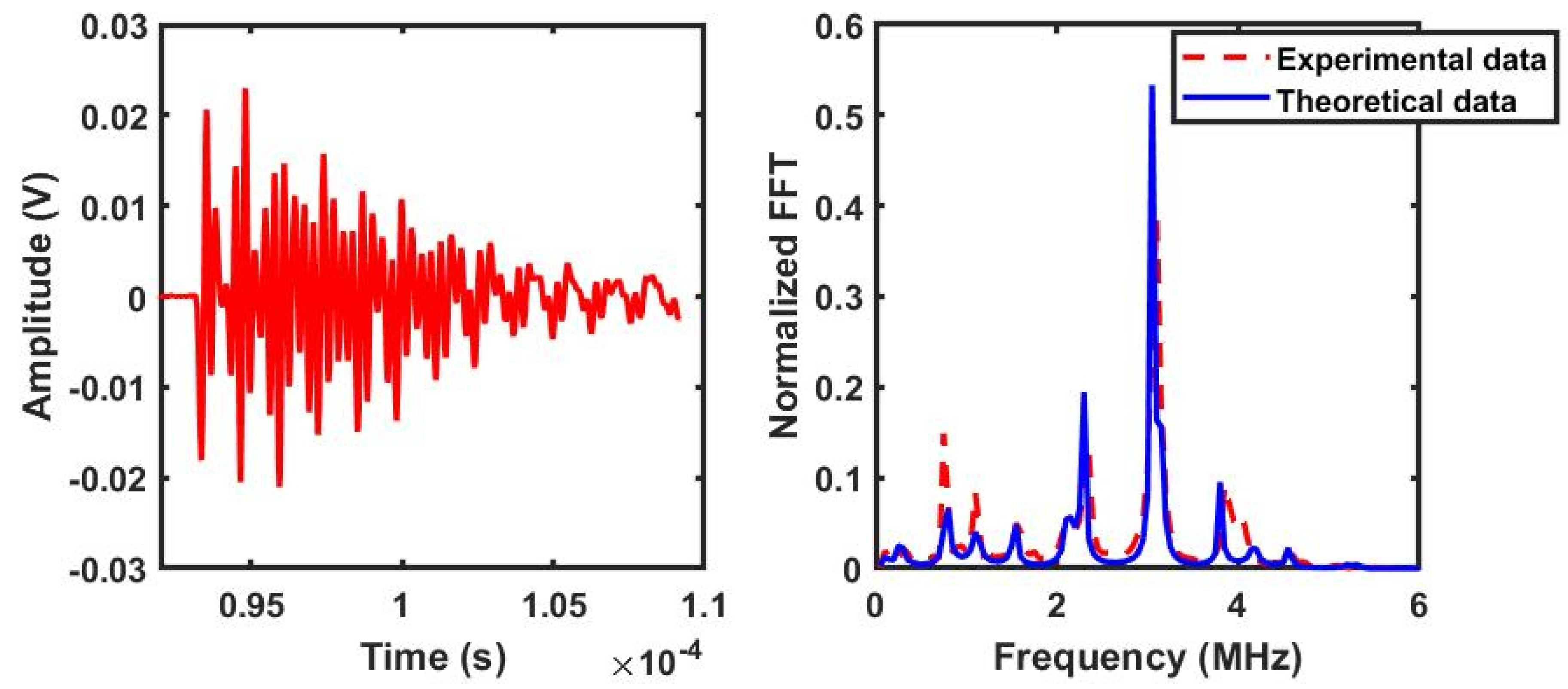

The aim of this measurement was to analyse the transmitted wave field using the multilayered system model proposed, which includes several types of layers and boundary conditions previously discussed, including the TMM approach. The thicknesses of both the thin water layer and the slab layers were optimized using the genetic algorithm (GA) implemented in this study. The GA input parameters were configured as described in the third test of the earlier section. Figure 8 illustrates the time and frequency (red dotted line) transmission coefficients of acoustic waves measured at normal incidence across the multilayered system and the comparison with the theoretical spectrum calculated using the GA (blue curve).

Figure 8.

Temporal and spectral representations of the transmission measurement through the multilayered system.

The retrieved parameters, such as the thickness of all layers in the system, using the GA are close to the real ones presented in Table 1, particularly for the aluminium and the glass, which we can measure with low error. The thickness of the thin water layer that separates the slabs is on the order of magnitude of µm.

Table 3 provides the parameters optimized for each layer in the system using the GA. these results are compared with the measured ones to note the errors. It should be noted that the thickness of the thin central layer of water corresponds to an average value, given the imperfect condition of the surface of the solid layers on either side.

Table 3.

Retrieved system parameters using GA (population size = 100, generations = 100).

6.3. Measurements on Porous Material

In this last part, we present the results for a multilayer system with various types of media, including a poroelastic material. Transfer matrix elements for each medium and relationships to the different boundary conditions can be found in Appendix A. These matrices are considered a key part of the TMM technique.

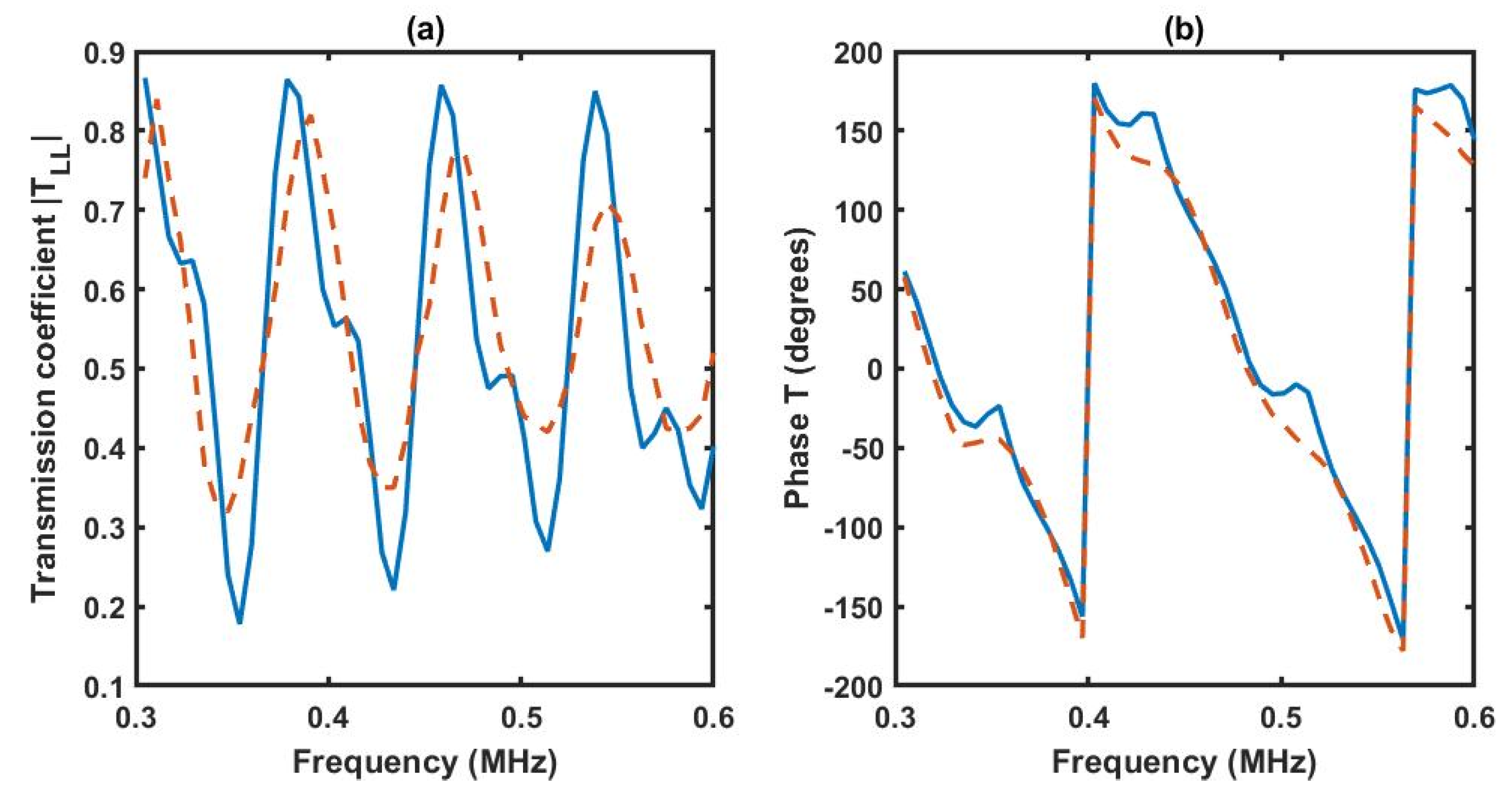

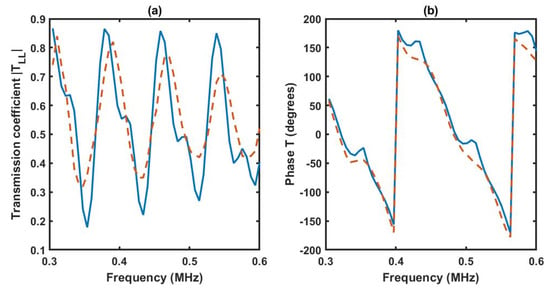

Jocker and Smeulders [40] conducted a study on acoustic wave propagation in porous materials. In this work, we compare their experimental data with the results obtained from our model in order to validate its accuracy. The comparison focuses on the results corresponding to sample S3 from their study, which consists of a plane-parallel glass disc with a diameter of 15 cm and a thickness of approximately 15.7 cm. The sample is made of sintered glass powder and is commercially available from Technoglas (Voorhout, The Netherlands). This type of material is commonly used as a filtration medium in the chemical industry [40]. The comparison is carried out using the transmission coefficient spectra and the phase information (see Figures 4A and 5A in [40], respectively). The properties of the poroelastic reference materials are reported in Table 1 and Table 2 of the same article.

To solve the inverse problem associated with the characterization and estimation of some internal parameters of the poroelastic media, the GA described previously was employed. The algorithm was configured to ensure both robustness and precision in the estimation of model parameters.

The GA was configured with a large population size of 200 individuals, and the maximum number of generations was set to 2000, providing sufficient iterations for the evolutionary process to converge toward an optimal or near-optimal solution. In this optimization, the mutation function was defined as a Gaussian mutation with a scale of 0.05 and a shrink factor of 0.9, allowing the algorithm to perform fine and controlled variations around candidate solutions. The crossover fraction was set to 0.5 to ensure a balanced exchange of genetic material between individuals. Finally, a stall generation limit of 500 was imposed to ensure convergence and to avoid unnecessary iterations when no further improvement is observed.

Considering porous material, some parameters are difficult to measure experimentally, especially for inner characteristics. Using the inverse problem algorithm, we estimated the following parameters: the thickness d, the density of the solid matrix , static tortuosity , porosity factor ф, viscous characteristic length Λ, permeability factor Kp, and pore ratio size Rp. Table 4 presents the initial guess of each optimized parameter used in the inverse problem algorithm. Note that a good initial guess can significantly accelerate the convergence of the genetic algorithm.

Table 4.

Initial guess of the parameters optimized using the GA.

Figure 9 illustrates the transmission coefficients at normal incidence, modulus, and phase obtained using our approach and the reference data. The comparison of the curves validates the approach developed in this work. Nevertheless, the comparison of both signals highlights some errors in the amplitudes. These discrepancies come from the sensitivity of dynamic tortuosity , depends significantly on the frequency and the parameters optimized in this work. The GA converges toward individuals that represent optimal solutions across all genomes. In cases where multiple parameters are optimized simultaneously, the algorithm tends to reach a solution that is close to the global optimum. As a result, there will be an error associated with each parameter.

Figure 9.

Transmission coefficient modulus (a) and phase (b) at normal incidence. Inversion procedure results (solid blue line) and reference data (dashed red line).

Table 5 presents the mechanical properties obtained from the theoretical model and the comparison with the corresponding values from the work of Jocker & Smeulders [40]. Overall, the theoretical predictions show a good agreement with the measurements, particularly for the thickness, the solid density, and the bulk modulus of the solid and fluid phases (Ks and Kf), which are almost identical. The porosity, however, is slightly overestimated by the model (ϕ = 0.7) compared to the reference value (ϕ = 0.5). The calculation formulas of kb and Sh are based on the homogenization approach of Kuster and Toksôz [42].

Table 5.

Mechanical properties obtained from the theoretical model compared with those from reference [40].

Significant differences are observed in the permeability, where the theoretical model predicts a much higher value (k0 = 74.3 Darcies) compared to the experimental measurement (8 Darcies). Similarly, discrepancies are noticeable in the shear modulus (Sh) and shear wave velocity (Csh), with the model underestimating the experimental results. The dynamic parameters such as static tortuosity () and pore size Rp also show deviations, although the latter remains within the experimental range reported.

Regarding wave velocities, the first compressional wave velocity (Cp1) obtained using our approach (2563 m/s) was close to the reference value (2396.7 m/s). On the other hand, the second compressional wave velocity (Cp2) and the shear wave velocity (Csh) presented larger differences when compared to published results. In summary, the comparison highlights the ability of the theoretical model to capture the general trends of the mechanical properties and acoustic wave propagation through a poroelastic medium.

7. Conclusions

In this work we developed a transfer matrix approach for modelling the propagation of a normally incident acoustic wave in a multilayered system that can include diverse types of media, such as fluids, solids, and poroelastic materials. We described all the matrices associated with each type of layer and established the boundary conditions between adjacent layers, which allows all the individual matrices to be assembled into a single global matrix relating the displacement and stress at the first and last interfaces of the multilayered system. The transmission and reflection coefficients were then determined from the amplitudes of the longitudinal and shear potentials at these interfaces. This comprehensive forward model for acoustic wave propagation in multilayered systems using the transfer matrix method was then exploited within an inverse problem framework by coupling it with a genetic algorithm to retrieve material parameters from experimental transmission data. In future work, this approach will be used to retrieve acoustic properties of specific layers within a multilayer structure. Among others, the case of Li-ion batteries will be considered, aiming at monitoring functional data such as their state of charge and state of health based on the measurement of acoustic parameters of internal layers.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.M., L.H. and J.B.; methodology, Y.M. and J.B.; software, Y.M.; validation, Y.M., L.H., J.B. and M.L.; formal analysis, Y.M.; investigation, Y.M.; resources, Y.M.; data curation, Y.M.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.M., L.H., J.B.; writing—review and editing, Y.M., L.H., J.B. and M.L.; visualization, Y.M.; supervision, K.C. and M.L.; project administration, K.C. and M.L.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Acoustic wave propagation behaves differently depending on the medium. In this section, we present the expressions for wave velocities and associated stress fields. Furthermore, the matrices M and M−1, which relate wave velocities to potential amplitudes at each point in the medium, are given below for the case of normal incidence.

- I.

- Fluid medium

- II.

- Solid medium

The velocities and stress expressions of the wave in the solid media are expressed in the following Equations (A2) and (A3): [15,17]

The mathematical derivation of Equations (A2) and (A3) allows for the determination of the matrices Ms and Ms−1, which describe the relationship between the wave potential amplitudes and the corresponding velocity and stress components in the solid medium under normal incidence.

In the case of oblique incidence, several components of the matrices Ms and Ms−1 become non-zero: , and . This reflects the coupling between wave modes induced by the angle of incidence, which modifies the symmetry and interaction between the velocity and stress components in the solid medium.

- III.

- Poroelastic medium

The expressions of velocities and stresses of acoustical waves in a poroelastic medium are expressed below:

and

Similarly, the matrix , that describe the velocities and stresses as functions of the wave amplitudes A for a normal incidence is given:

with

- -

- -

- -

- -

- -

Note that the following matrix elements become nonzero under oblique incidence , , , , , and .

Next, the expressions below are the terms of the inverse matrix in the poroelastic medium. As for matrix , there are non-zero coefficients for oblique incidence in the matrix ,

Where , , and .

References

- Atalla, N.; Amédin, C.K.; Panneton, R.; Sgard, F. Étude Numérique et Expérimentale de L’absorption Acoustique et de la Transparence Acoustique des Matériaux Poreux Hétérogènes en Basses Fréquences dans le but d’Identifier des Solutions à Fort Potentiel d’Applicabilité. 2001. Available online: https://pharesst.irsst.qc.ca/rapports-scientifique/668 (accessed on 9 September 2025).

- Jocker, J.; Smeulders, D.; Drijkoningen, G.; van der Lee, C.; Kalfsbeek, A. Matrix propagator method for layered porous media: Analytical expressions and stability criteria. Geophysics 2004, 69, 1071–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y.Q.; He, J.Q.; Liu, Q.H. The application of the perfectly matched layer in numerical modeling of wave propagation in poroelastic media. Geophysics 2001, 66, 1258–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, G.; Mo, Z.; Bolton, J.S. A general and stable approach to modeling and coupling multilayered acoustical systems with various types of layers. J. Sound. Vib. 2023, 567, 117898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bustillo, J.; Fortineau, J.; Gautier, G.; Lethiecq, M. Ultrasonic characterization of porous silicon using a genetic algorithm to solve the inverse problem. NDT E Int. 2013, 62, 93–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilyina, N.; Hermans, J.; Verboven, E.; Abeele, K.V.D.; D’AGostino, E.; D’HOoge, J. Attenuation estimation by repeatedly solving the forward scattering problem. Ultrasonics 2017, 84, 201–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pialucha, T.; Cawley, P. The detection of thin embedded layers using normal incidence ultrasound. Ultrasonics 1994, 32, 431–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinra, V.K.; Iyer, V.R. Ultrasonic measurement of the thickness, phase velocity, density or attenuation of a thin-viscoelastic plate. Part I: The forward problem. Ultrasonics 1995, 33, 95–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messineo, M.G.; Rus, G.; Eliçabe, G.E.; Frontini, G.L. Layered material characterization using ultrasonic transmission. An inverse estimation methodology. Ultrasonics 2016, 65, 315–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomson, W.T. Transmission of Elastic Waves through a Stratified Solid Medium. J. Appl. Phys. 1950, 21, 89–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haskell, N.A. The dispersion of surface waves on multilayered media. Bull. Seismol. Soc. Am. 1953, 43, 17–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biot, M.A. Theory of Propagation of Elastic Waves in a Fluid-Saturated Porous Solid. I. Low-Frequency Range. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 1956, 28, 168–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biot, M.A. Theory of Propagation of Elastic Waves in a Fluid-Saturated Porous Solid. II. Higher Frequency Range. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 1956, 28, 179–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.; Cegla, F.; Lan, B. Stiffness matrix method for modelling wave propagation in arbitrary multilayers. Int. J. Eng. Sci. 2023, 190, 103888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cervenka, P.; Challande, P. A new efficient algorithm to compute the exact reflection and transmission factors for plane waves in layered absorbing media (liquids and solids). J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 1991, 89, 1579–1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mal, A.K.; Kundu, T. Calculation of the acoustic material signature of a layered solid. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 1985, 77, 353–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allard, J.F.; Atalla, N. Propagation of Sound in Porous Media: Modelling Sound Absorbing Materials; John Wiley and Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biot, M.A.; Willis, D.G. Willis. The Elastic Coefficients of the Theory of Consolidation. J. Appl. Mech. 1957, 24, 594–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, D.L.; Koplik, J.; Schwartz, L.M. New Pore-Size Parameter Characterizing Transport in Porous Media. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1986, 57, 2564–2567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, D.L.; Hemmick, D.L.; Kojima, H. Probing porous media with first and second sound. I. Dynamic permeability. J. Appl. Phys. 1994, 76, 104–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, D.L.; Plona, T.J.; Kojima, H. Probing porous media with 1st sound, 2nd sound, 4th sound, and 3rd sound. AIP Conf. Proc. 1987, 154, 243–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boudreau, B.P. The diffusive tortuosity of fine-grained unlithified sediments. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 1996, 60, 3139–3142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knopoff, L. A matrix method for elastic wave problems. Bull. Seismol. Soc. Am. 1964, 54, 431–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randall, M.J. Fast programs for layered half-space problems. Bull. Seismol. Soc. Am. 1967, 57, 1299–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, H.; Jensen, F.B. A full wave solution for propagation in multilayered viscoelastic media with application to Gaussian beam reflection at fluid–solid interfaces. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 1985, 77, 813–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, H.; Tango, G. Efficient global matrix approach to the computation of synthetic seismograms. Geophys. J. Int. 1986, 84, 331–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mal, A.K. Wave propagation in layered composite laminates under periodic surface loads. Wave Motion 1988, 10, 257–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storheim, E.; Lohne, K.D.; Hergum, T. Transmission and reflection from a layered medium in water. Simulations and measurements. In Proceedings of the 38th Scandinavian Symposium on Physical Acoustics, Geilo, Norway, 1–4 February 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Lowe, M.J. Matrix Techniques for Modeling Ultrasonic Waves in Multilayered Media. IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Freq. Control 1995, 42, 525–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kausel, E.; Roësset, J.M.; Kausel, E.; Roësset, J.M. Stiffness matrices for layered soils. BuSSA 1981, 71, 1743–1761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rokhlin, S.I.; Wang, L. Stable recursive algorithm for elastic wave propagation in layered anisotropic media: Stiffness matrix method. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2002, 112, 822–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panneton, R.; Atalla, N. An efficient finite element scheme for solving the three-dimensional poroelasticity problem in acoustics. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 1997, 101, 3287–3298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Lyu, Y.; Zheng, M.; Liu, M.; Liu, H.; Wu, B.; He, C. Guided waves propagation in multi-layered porous materials by the global matrix method and Biot theory. Appl. Acoust. 2021, 184, 108356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fellah, Z.E.A.; Fellah, M.; Depollier, C. Transient Acoustic Wave Propagation in Porous Media; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attenborough, K. Acoustical Characteristics of Porous Materials. Phys. Rep. Rev. Sect. Phys. Lett. 1982, 82, 179–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attenborough, K. Acoustical characteristics of rigid fibrous absorbents and granular materials. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 1983, 73, 785–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, D.L.; Koplik, J.; Dashen, R. Theory of dynamic permeability and tortuosity in fluid-saturated porous media. J. Fluid. Mech. 1987, 176, 379–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Champoux, Y.; Allard, J.F. Dynamic tortuosity and bulk modulus in air-saturated porous media. J. Appl. Phys. 1991, 70, 1975–1979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lafarge, D.; Lemarinier, P.; Allard, J.F.; Tarnow, V. Dynamic compressibility of air in porous structures at audible frequencies. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 1997, 102, 1995–2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jocker, J.; Smeulders, D. Ultrasonic measurements on poroelastic slabs: Determination of reflection and transmission coefficients and processing for Biot input parameters. Ultrasonics 2009, 49, 319–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, D.L.; Plona, T.J. Acoustic slow waves and the consolidation transition. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 1982, 72, 556–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuster, G.T.; Toksoz, M.N. Velocity and attenuation of seismic waves in two-phase media; Part I, Theoretical formulations. Geophysics 1974, 39, 587–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berryman, J.G. Mixture Theories for Rock Properties. In AGU Reference Shelf; Ahrens, T.J., Ed.; American Geophysical Union: Washington, DC, USA, 2013; pp. 205–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bustillo, J. Caractérisation non Destructive du Silicium Poreux par Méthode Ultrasonore. Ph.D. Thesis, Université de Tours, Tours, France, 10 December 2013. Available online: http://www.theses.fr/2013TOUR4026 (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- Delsanto, S.; Griffa, M.; Morra, L. Inverse Problems and Genetic Algorithms. In Universality of Nonclassical Nonlinearity; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2006; Chapter 22; pp. 349–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland, J.H. Adaptation in Natural and Artificial Systems; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papazoglou, G.; Biskas, P. Review and Comparison of Genetic Algorithm and Particle Swarm Optimization in the Optimal Power Flow Problem. Energies 2023, 16, 1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, D.E. Genetic Algorithm in Search, Optimization, and Machine Learning; Addison Wesley Publishing Company: Reading, MA, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Michalewicz, Z. Genetic Algorithms + Data Structures = Evolution Programs; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudolph, G. Convergence analysis of canonical genetic algorithms. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. 1994, 5, 96–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, K.; Man, K.; Kwong, S.; He, Q. Genetic algorithms and their applications. IEEE Signal Process Mag. 1996, 13, 22–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, P. Direct measurement of ultrasonic dispersion using a broadband transmission technique. Ultrasonics 1999, 37, 67–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selfridge, A.R. Approximate Material Properties in Isotropic Materials. IEEE Trans. Sonics Ultrason. 1985, 32, 381–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).