Abstract

Background: Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is associated with systemic inflammation and potential cardiovascular complications. This meta-analysis evaluates long-term cardiovascular risks in IBD. Methods: Electronic databases were searched for studies examining cardiovascular, cerebrovascular, and thromboembolic risks in IBD. Adjusted hazard ratios (aHRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were pooled using a random-effects model. Results: Fifty-three studies comprising 1,406,773 patients were analyzed. IBD was linked to increased risk of ischemic heart disease (aHR 1.25; p = 0.001) myocardial infarction (aHR 1.25; p = 0.01), acute coronary syndrome (aHR 1.43; p < 0.00001), heart failure (aHR 1.24; p < 0.00001), atrial fibrillation (aHR 1.20; p < 0.00001), and stroke (aHR 1.13; p < 0.00001). Elevated risks were also observed for peripheral arterial disease (aHR 1.41; p < 0.00001), diabetes mellitus (aHR 1.40; p < 0.00001), venous thromboembolism (aHR 1.98; p < 0.00001), deep vein thrombosis (aHR 2.85; p = 0.0004), and pulmonary embolism (aHR 1.98; p = 0.03). Importantly, IBD was associated with increased cardiovascular (aHR 1.14; p = 0.03) and all-cause mortality (aHR 1.53; p < 0.00001). Conclusions: IBD patients face higher risk for adverse cardiovascular outcomes, thromboembolic disease, and mortality, necessitating early cardiovascular risk assessment and targeted interventions in this population.

1. Introduction

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), encompassing ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn’s disease (CD), presents a significant global health burden. The prevalence of IBD has been rising worldwide, with an estimated 4.9 million cases in 2019 [1]. Its incidence is increasing in newly industrialized countries but has plateaued in high-income nations [2]. The relapsing-remitting nature of IBD leads to persistent symptoms, frequent medical visits, and the need for ongoing treatment, all of which contribute to a reduced quality of life [3,4]. Patients often face challenges such as managing daily activities, maintaining social relationships, and coping with the psychological burden of the disease [5]. Moreover, systemic inflammation, as occurs in IBD and other chronic autoimmune diseases including psoriasis, rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, and systemic sclerosis, has been implicated in the pathogenesis of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease and chronic inflammation has been linked to an increased risk for developing cholangiocarcinoma and colorectal cancer [6,7].

Multiple studies have reported an increased risk of new-onset cardiovascular disease (CVD) in patients with IBD [8,9,10]. The systemic inflammation caused by IBD, particularly during flare-ups, involves the release of proinflammatory cytokines like tumor necrosis factor (TNF) alpha, interleukins-1,6,8 and 12, generation of reactive oxygen species, endothelial dysfunction, and platelet activation [11]. These processes ultimately contribute to atherosclerotic changes, such as arterial stiffening, coronary microcirculatory dysfunction, and increased carotid intima-media thickness, as well as a hypercoagulable state. Moreover, certain IBD medications such as 5-aminosalicylates, glucocorticoids, and the JAK inhibitor tofacitinib have associated cardiovascular adverse effects [12,13,14,15].

Previous meta-analyses have reported conflicting results on the association between IBD and cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases [8,16,17]. Newer data from more recent longitudinal cohorts also warrant an update to these previous reviews [10,18,19,20,21,22]. Therefore, we sought to conduct a comprehensive, up-to-date meta-analysis on the long-term risk of incident cardiovascular, cerebrovascular, and thromboembolic events among patients with IBD, compared with healthy controls.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Resources and Search Strategy

We reported this meta-analysis in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [23]. The study protocol was not submitted to PROSPERO. Search methods also included publication language restrictions. Only English-language studies were included. Two independent reviewers (R.H.S and M.M.J) conducted an electronic search of PubMed, Embase, and Cochrane Central from inception till 30 November 2025 using the search string: (“inflammatory bowel disease” OR “IBD” OR “ulcerative colitis” OR “Crohn’s disease”) AND (“cardiovascular” OR “myocardial infarction” OR “MI” OR “angina” OR “acute coronary syndrome” OR “ischemic heart disease” OR “coronary heart disease” OR CHD OR “coronary artery disease” OR CAD OR atherosclero* OR “ASCVD” OR “heart failure” OR HF OR “atrial fibrillation” OR arrhythm* OR “peripheral arterial disease” OR PAD OR “peripheral vascular disease” OR PVD OR “cerebrovascular” OR stroke OR “hemorrhagic stroke” OR “ischemic stroke” OR “transient ischemic attack” OR thrombo* OR VTE OR “deep vein thrombosis” OR “pulmonary embolism” OR PE OR emboli* OR “death” OR “cardiovascular death” OR “mortality” OR “cardiovascular mortality” OR “cerebrovascular death” OR “cerebrovascular mortality”) AND (risk OR inciden* OR “new onset” OR “de novo”). In addition, the references in each study, previous meta-analyses and review articles were also manually screened to prevent the omission of any relevant studies during the electronic search.

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The inclusion criteria for our meta-analysis were: (1) cohort studies, (2) IBD patients as the exposure group, (3) non-IBD patients as the control group, and (4) reported outcomes of interest. Studies lacking valid controls or not reporting our outcomes of interest were excluded as were cross-sectional studies, review articles, case reports, letters, and editorials.

2.3. Study Selection and Data Extraction

The articles obtained from the systematic search were exported to the Mendeley Reference Library software v2.130.2, where duplicates were screened and removed. Two reviewers (R.H.S and M.M.J) individually evaluated if a study satisfied the inclusion criteria. A third reviewer (M.S) was consulted to resolve any discrepancies. When two or more studies reported data from the same patient population for a particular outcome, the study with the larger sample size was preferred, to avoid patient overlap. Outcomes extracted were ischemic heart disease (IHD), myocardial infarction (MI), atrial fibrillation (AF), heart failure (HF), stroke, peripheral arterial disease (PAD), diabetes mellitus (DM), venous thromboembolism (VTE), deep vein thrombosis (DVT), pulmonary embolism (PE), and cardiovascular and all-cause mortality.

2.4. Quality Assessment

We used the Newcastle–Ottawa scale [24] for the quality assessment of observational studies.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using Review Manager (version 5.4.1; Copenhagen, Denmark. The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration, 2014). Adjusted hazard ratios (aHR) with 95% confidence intervals were pooled for all outcomes using a random effects model. A separate unadjusted analysis was conducted to include studies reporting incidence rate ratios, odds ratios, standardized incidence ratios, or other measures of effect that cannot be pooled with HRs. Raw event rates were extracted from these studies, if available, and pooled as risk ratios (RR).

Forest plots were generated to visually assess the pooled results. Subgroup differences were assessed using a Chi-square test. Publication bias was evaluated using Begg’s test and visual inspection of the funnel plot. The I2 statistic was used to assess heterogeneity across studies, and an I2 value of 25–50% was considered mild, 50–75% as moderate, and I2 > 75% as severe heterogeneity [25]. To explore heterogeneity, we used the leave-one-out method by consecutively omitting one study at a time to identify the study contributing the most to heterogeneity. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant in all cases.

3. Results

3.1. Literature Search Results

A total of 5170 articles were identified after searching electronic databases. After duplicate removal and screening titles and abstracts, 188 full-text articles were assessed for eligibility. Of these, 53 studies matched our inclusion criteria and were ultimately included in the analysis [10,18,19,20,21,22,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72]. The PRISMA flowchart summarizing the literature search and study selection procedure is presented in Supplementary Figure S1.

3.2. Study Characteristics and Quality Assessment

The 53 studies encompassed a total of 1,406,773 patients with IBD. 619,490 patients with UC and 398,612 patients with CD were included in the analysis. The mean follow-up time ranged from 4.1 years to 13.7 years. The average age of IBD patients ranged from 12.6 years to 58 years. The proportion of females across our included studies ranged from 30.2% to 60%. The baseline patient and study characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of included patients and studies.

All the studies included were of a reasonably high methodological quality. The results of the risk of bias assessment are presented in Supplementary Table S1. Symmetry in the funnel plot (Supplementary Figure S2) suggests the absence of a small study and publication bias.

3.3. Results of Meta-Analysis

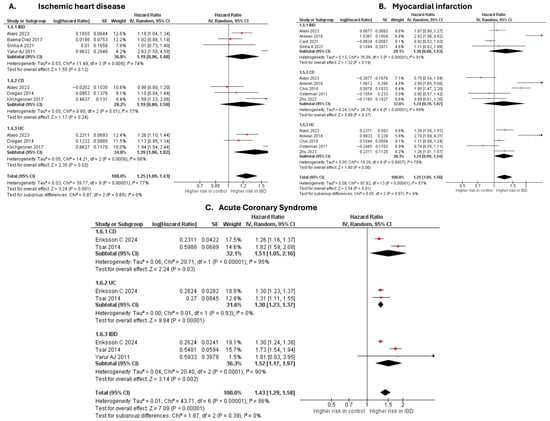

3.3.1. Coronary Atherosclerosis and Acute Coronary Syndromes

Ischemic heart disease

Six studies [20,28,37,50,63,69] were included in the adjusted analysis (Figure 1). There was a significantly increased risk of IHD among IBD patients, compared with controls (aHR: 1.25, 95% CI: 1.09–1.43; p = 0.001; I2 = 77%). This finding was consistent across subgroups (p-value for subgroup difference = 0.65). Sensitivity analysis by excluding Kirchgesner et al. [50] reduced heterogeneity to 56% (Supplementary Figure S3).

Figure 1.

Forest plot of coronary atherosclerosis and acute coronary syndromes.

An unadjusted analysis of four studies [29,39,43,61] revealed no significant difference in the risk of IHD between IBD and controls (RR: 0.57, 95% CI: 0.26–1.25; p = 0.16; I2 = 100%; Supplementary Figure S4).

Myocardial infarction

Six studies [20,27,32,33,58,63] were included in the adjusted analysis (Figure 1). There was a significantly increased risk of MI among IBD patients, compared with controls (aHR: 1.25, 95% CI: 1.05–1.50; p = 0.01; I2 = 87%). This finding was consistent across subgroups (p-value for subgroup difference = 0.97). Sensitivity analysis by excluding Aniwan et al. [27] reduced heterogeneity to 78% (Supplementary Figure S5).

An unadjusted analysis of three studies [41,51,62] also revealed a significantly increased risk of MI among IBD patients, compared with controls (HR: 1.29, 95% CI: 1.12–1.49; p = 0.0005; I2 = 82%; Supplementary Figure S6). There was a significantly higher risk of MI in the UC subgroup compared with CD (p = 0.04).

Acute coronary syndrome

Three studies [19,67,69] were included in the adjusted analysis (Figure 1). There was a significantly increased risk of ACS among IBD patients, compared with controls (aHR: 1.43, 95% CI: 1.29–1.58; p < 0.00001; I2 = 86%). This finding was consistent across subgroups (p-value for subgroup difference = 0.39). Sensitivity analysis by excluding Tsai et al. [67] reduced heterogeneity to 0% (Supplementary Figure S7).

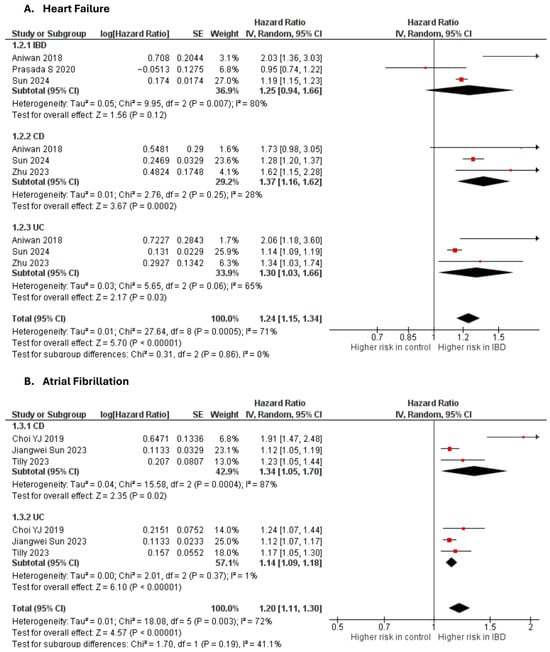

3.3.2. Cardiac Dysfunction and Arrhythmia

Heart failure

Four studies [10,18,27,59] were included in the adjusted analysis (Figure 2). There was a significantly increased risk of HF among IBD patients, compared with controls (aHR: 1.24, 95% CI: 1.15–1.34; p < 0.00001; I2 = 71%). This finding was consistent across subgroups (p-value for subgroup difference = 0.86). Sensitivity analysis by excluding Aniwan et al. [27] slightly reduced heterogeneity to 68% (Supplementary Figure S8).

Figure 2.

Forest plot of cardiac dysfunction and arrhythmias.

Atrial fibrillation

Three studies [22,34,64] were included in the adjusted analysis (Figure 2). There was a significantly increased risk of AF among IBD patients, compared with controls (aHR: 1.20, 95% CI: 1.11–1.30; p < 0.00001; I2 = 72%). This finding was consistent across subgroups (p-value for subgroup difference = 0.19). Sensitivity analysis by excluding Choi et al. [34] reduced heterogeneity to 0% (Supplementary Figure S9).

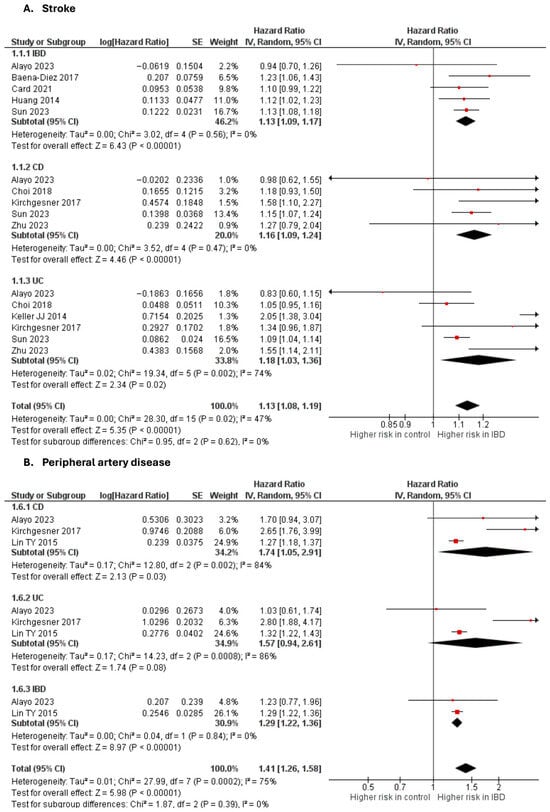

3.3.3. Cerebrovascular and Peripheral Vascular Disease

Stroke

Nine studies [10,20,28,32,33,45,48,50,65] were included in the adjusted analysis (Figure 3). There was a significantly increased risk of stroke among IBD patients, compared with controls (aHR: 1.13, 95% CI: 1.08–1.19; p < 0.00001; I2 = 47%). This finding was consistent across subgroups (p-value for subgroup difference = 0.62).

Figure 3.

Forest plot of cerebrovascular and peripheral vascular disease.

An unadjusted analysis of five studies [26,29,51,52,62] also revealed a significantly increased risk of stroke among IBD patients, compared with controls (RR: 1.29, 95% CI: 1.22–1.36; p < 0.00001; I2 = 47%; Supplementary Figure S10).

Peripheral arterial disease

Three studies [20,50,55] were included in the adjusted analysis (Figure 3). There was a significantly increased risk of PAD among IBD patients, compared with controls (aHR: 1.41, 95% CI: 1.26–1.58; p < 0.00001; I2 = 75%). This finding was consistent across subgroups (p-value for subgroup difference = 0.39). Sensitivity analysis by excluding Kirchgesner et al. [50] reduced heterogeneity to 0% (Supplementary Figure S11).

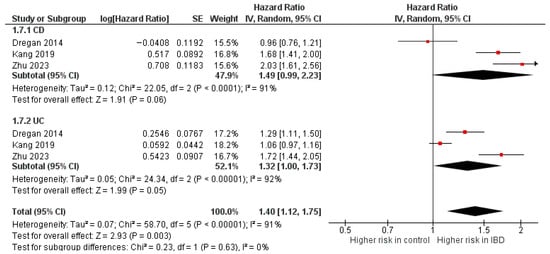

Diabetes mellitus

Three studies [10,37,46] were included in the adjusted analysis (Figure 4). There was a significantly increased risk of DM among IBD patients, compared with controls (aHR: 1.40, 95% CI: 1.12–1.75; p < 0.00001; I2 = 91%). This finding was consistent across subgroups (p-value for subgroup difference = 0.63). Sensitivity analysis by excluding Kang et al. [46] slightly reduced heterogeneity to 88% (Supplementary Figure S12).

Figure 4.

Forest plot of diabetes mellitus.

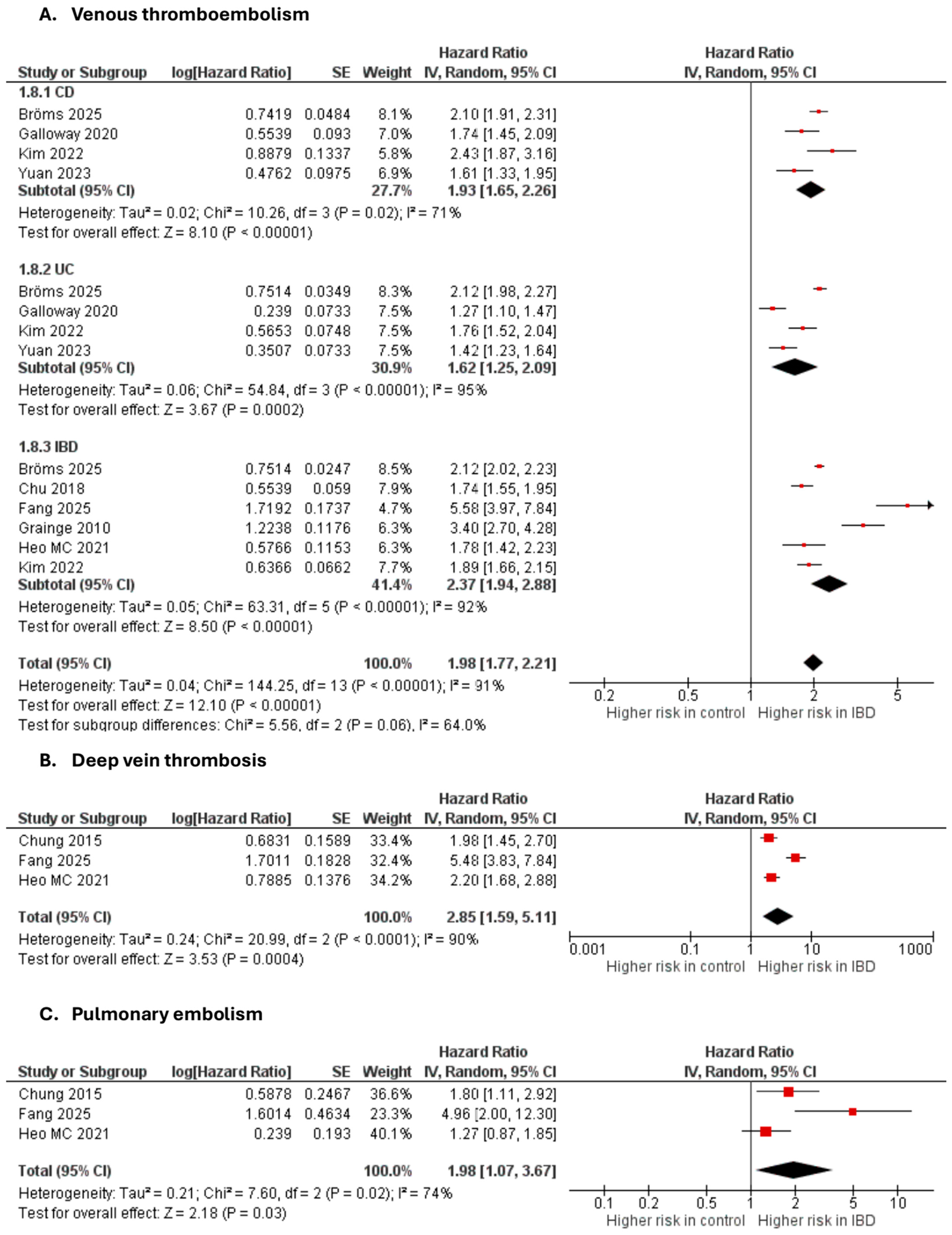

3.3.4. Venous Thromboembolic Events

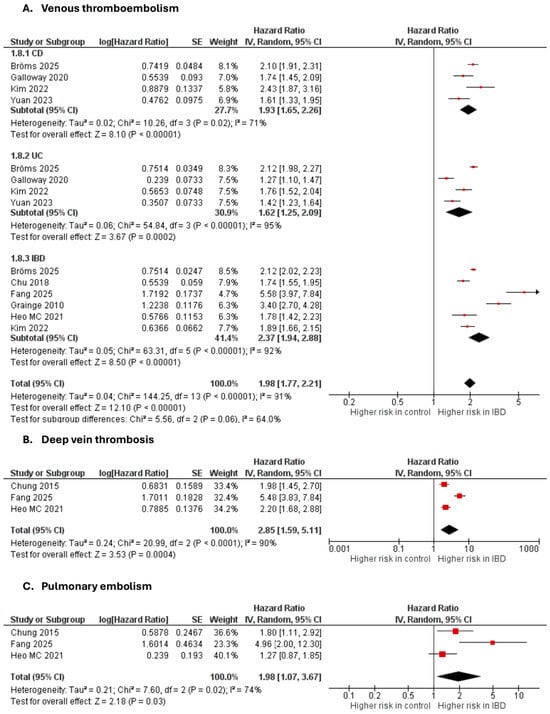

Venous thromboembolism

Seven studies [35,40,42,44,49,70,71,72] were included in the adjusted analysis (Figure 5). There was a significantly increased risk of VTE among IBD patients, compared with controls (aHR: 1.98, 95% CI: 1.77–2.21; p < 0.00001; I2 = 91%). This finding was consistent across subgroups (p-value for subgroup difference = 0.06). Sensitivity analysis by excluding Fang et al. [42] slightly reduced heterogeneity to 89% (Supplementary Figure S13).

Figure 5.

Forest plot of venous thromboembolic events.

An unadjusted analysis of four studies [47,60,62,68] also revealed a significantly increased risk of VTE among IBD patients, compared with controls (RR: 1.91, 95% CI: 1.66–2.20; p < 0.00001; I2 = 91%; Supplementary Figure S14).

Deep vein thrombosis

Three studies [36,44,72] were included in the adjusted analysis (Figure 5). There was a significantly increased risk of DVT among IBD patients, compared with controls (aHR: 2.85, 95% CI: 1.59–5.11, p = 0.0004; I2 = 90%).

An unadjusted analysis of four studies [40,47,62,68] also revealed a significantly increased risk of DVT among IBD patients, compared with controls (RR: 1.73, 95% CI: 1.50–1.99; p < 0.00001; I2 = 87%; Supplementary Figure S15).

Pulmonary embolism

Three studies [36,44,72] were included in the adjusted analysis (Figure 5). There was a significantly increased risk of PE among IBD patients, compared with controls (aHR: 1.98, 95% CI: 1.07–3.67, p = 0.03; I2 = 74%).

An unadjusted analysis of four studies [40,47,62,68] also revealed a significantly increased risk of PE among IBD patients, compared with controls (RR: 1.78, 95% CI: 1.53–2.06; p < 0.00001; I2 = 83%; Supplementary Figure S16).

3.3.5. Mortality

Cardiovascular mortality

Six studies [21,27,30,32,54,57] were included in the adjusted analysis. There was a significantly increased risk of cardiovascular mortality among IBD patients, compared with controls (aHR: 1.14, 95% CI: 1.02–1.29, p = 0.03; I2 = 72%). This finding was consistent across subgroups (p-value for subgroup difference = 0.14). Sensitivity analysis by excluding Bernstein CN [30] reduced heterogeneity to 61% (Supplementary Figure S17).

All-cause mortality

Eight studies [27,28,30,31,33,38,54,57] were included in the adjusted analysis. There was a significantly increased risk of all-cause mortality among IBD patients, compared with controls (HR: 1.53, 95% CI: 1.34–1.75; p < 0.00001; I2 = 97%). This finding was consistent across subgroups (p-value for subgroup difference = 0.46). Sensitivity analysis by excluding Olen et al. [57] slightly reduced heterogeneity to 94% (Supplementary Figure S18).

An unadjusted analysis of two studies [41,56] also revealed a significantly increased risk of all-cause mortality among IBD patients, compared with controls (RR: 1.24, 95% CI: 1.10–1.39; p < 0.003; I2 = 34%; Supplementary Figure S19).

4. Discussion

Our systematic review and meta-analysis assessed the long-term risk of CVD, stroke, and thromboembolic events in 1.4 million IBD patients, compared with healthy controls. Our pooled analysis revealed an increased risk of IHD, MI, AF, HF, stroke, PAD, DM, VTE, DVT, PE, and cardiovascular and all-cause mortality in IBD patients, compared with non-IBD controls.

Our results are largely consistent with previous meta-analyses [8,73,74,75]. However, the larger sample size of the present study imparts greater statistical power to our results. We synthesized evidence from 53 studies, including several recently published, large, population-based studies [10,18,19,20,22,70,71,72]; hence our meta-analysis represents the most comprehensive and updated review on this topic, to the best of our knowledge. We excluded studies that used overlapping patient data, which increases the credibility of our estimates. Further, to obtain the most accurate estimate of long-term risk, we pooled hazard ratios, specifically those that were adjusted for the greatest possible confounders. For this reason, we also excluded cross-sectional and survey-based studies that reported prevalent cases of CVD, rather than incident cases.

There is extensive literature focusing on the link between IBD and IHD. While the exact mechanism for the association remains unclear, it is believed that thrombosis and atherosclerosis are promoted by the systemic proinflammatory state in IBD, which is characterized by high levels of cytokines such as TNF-alpha, IL-12, IL-23, and possibly IL-17 and interferon-gamma [76,77]. IBD is also associated with an atherogenic lipoprotein profile, including reduced HDL-C and increased LDL-C, although it is not well-understood whether lipid malabsorption or systemic inflammation plays a bigger role as the key mediator of these changes [78]. Nevertheless, evidence from large, prospective cohort studies and meta-analyses is still equivocal. Many of our included studies do not report a significant long-term risk of IHD among IBD patients [28,30,37,43,61,62]. In two studies, the risk of IHD was in fact lower in the IBD groups than in controls [43,61]; one of these studies (Rungoe et al.) [61] had a relatively long follow-up duration of 13 years and utilized data on nearly 28,000 IBD patients from Danish National Patient Registers. On the contrary, another prospective cohort study [50] of nearly 200,000 IBD patients from the French National Hospital Discharge database, revealed an elevated risk of IHD in both UC and CD patients. The median follow-up was 3.4 years [50].

In our analysis, UC, but not CD patients, were at a heightened risk of developing IHD, although subgroup differences were not significant. However, preceding meta-analyses [16,73] report an elevated risk of IHD in both UC and CD subgroups. A differential cardiovascular risk in the two subtypes of IBD is also evidenced by Alayo et al.’s [20] cohort study, which utilized data from 5000 IBD patients enrolled in the UK Biobank. The risk of composite acute arterial events, IHD, and MI was significantly increased in the UC group, but not in CD [20]. Similarly, Rungoe et al. [61] also reported a higher incidence of IHD in UC but not in the CD subgroup. The reasons for this difference in risk are not well understood. These discrepancies between individual studies arise from variations in study populations, follow-up durations, and adjustments for confounding factors. Therefore, while our findings add to the growing body of evidence linking IHD and IBD, they also highlight the need for larger prospective cohorts to gain more robust insights.

Goyal et al. [75] recently reported an elevated risk of AF among patients with IBD, in their meta-analysis of seven studies (UC RR: 1.29; 95% CI: 1.08–1.53; p = 0.004]; CD RR: 1.30; 95% CI: 1.07–1.58; p = 0.008). Our findings corroborate this, further supporting the notion that chronic inflammation in IBD plays a critical role in increasing cardiovascular risk, particularly for arrhythmic events like AF. This is consistent with other studies linking systemic inflammation in IBD to AF through pathways involving oxidative stress and endothelial dysfunction [79].

Similar to Li et al. [16], our meta-analysis also reports a heightened risk of diabetes in patients with IBD. Proinflammatory cytokines may interfere with insulin signaling by disrupting the activation of insulin receptors, promoting insulin resistance [80,81]. Dysbiosis in IBD, characterized by reduced microbial diversity and an overrepresentation of proinflammatory species in the gut microbiome, may further exacerbate metabolic dysregulation [82,83]. Additionally, the impaired secretion of incretin hormones from the ileum, which is commonly affected in Crohn’s disease, may disrupt the enteropancreatic axis and contribute to beta-cell dysfunction and glucose intolerance [84,85].

The risk of incident HF was higher in IBD, among both CD (HR: 1.35, 95% CI: 1.05–1.70, p = 0.0004) and UC subgroups (1.14, 95%: 1.09–1.18, p < 0.00001). The strongest evidence to this end is provided by Sun and colleagues [18], on account of their long follow-up duration (median: 12.4 years), and large sample size (n = 81,749). They reported an adjusted HR of 1.19 (95% CI 1.15–1.23). Another nationwide cohort study by Kristensen et al. [86] reported a 37% increased risk of hospitalization for HF among IBD patients, particularly during flares or persistent activity. This study was not included in our formal analysis, because they reported incident rate ratios, which, owing to differences in definitions and underlying statistical assumptions, could not be reasonably pooled with the hazard ratios reported by our other studies [87]. Chronic inflammation and IBD medication are likely mediators of HF pathogenesis in IBD. Proinflammatory cytokines such as TNF-alpha, IL-1, and IL-6, which are chronically elevated in both IBD and HF, contribute to hemodynamic instability and cardiac remodeling [77,88]. Compelling evidence also exists for the risk of cardiotoxicity with many of the prevalent medications approved for use in IBD, including TNF-alpha inhibitors, Janus kinase inhibitors, and mesalamine [89,90,91,92]. In one pharmacovigilance study, HF constituted 0.6% of all adverse events reported with the use of infliximab, adalimumab, vedolizumab, ustekinumab, natalizumab, tofacitinib, certolizumab, and risankizumab in CD [89].

Consistent with preceding meta-analyses, we also report an increased risk of stroke and thromboembolic events such as VTE, DVT, and PE among IBD patients [8,70,71,72,93,94], in both UC and CD. This can be partly attributed to the hypercoagulable state induced by systemic inflammation and endothelial dysfunction [95]. Gut microbiome dysfunction is another feature of IBD, which may predispose patients to a heightened risk of thromboembolism [96,97].

While the pooled analysis revealed a high risk of cardiovascular death in IBD, subgroup analysis did not yield a significant result in either UC or CD. Nonetheless, epidemiological studies have reported a high burden of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in IBD [98,99]. The risk of all-cause mortality was also significantly increased, which is a plausible finding, given the numerous intestinal and extraintestinal manifestations of IBD.

Large prospective studies are needed to gain more comprehensive insights into the pathophysiologic mechanisms underlying IBD-associated CVD, particularly the role of systemic inflammation, dysbiosis, and IBD medications, which may independently exacerbate cardiovascular risk. Additionally, exploring the differential cardiovascular risks associated with UC and CD is crucial, as our findings suggest possible variations between these two subtypes. The interaction of IBD with comorbid conditions, such as diabetes and hypertension, also warrants attention, as it may compound cardiovascular risk. Treatment for IBD patients should integrate cardiovascular risk assessment and management, including routine screening for traditional risk factors such as hypertension, diabetes, and dyslipidemia, alongside targeted strategies to address inflammation, optimize gut health, and mitigate the potential cardiotoxic effects of IBD medications.

Limitations

Despite its merits, our study also has certain limitations. Firstly, we did not employ meta-regression to analyze the impact of mediating factors such as age, sex, smoking, obesity, and IBD medication. Secondly, to ensure statistical homogeneity, we intentionally excluded studies that did not report adjusted HRs or raw event rates, potentially limiting the generalizability of our pooled estimates. Thirdly, we observed high heterogeneity for many outcomes. Despite undertaking leave-one-out analyses, heterogeneity remained high for IHD, MI, VTE, and all-cause mortality, which may stem from regional and population-level differences in environmental factors, genetic predispositions, healthcare systems, and diagnostic criteria among our included studies. Finally, all observational studies are, by nature, prone to residual bias from unmeasured confounders, hence our meta-analysis cannot confirm a direct causal link between IBD and incident CVD.

5. Conclusions

Our meta-analysis confirms that patients with IBD face an elevated long-term risk of cardiovascular and thromboembolic disease, compared with individuals without IBD. These findings underscore the need for greater emphasis on cardiovascular risk assessment and management in patients with IBD.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/gidisord7040078/s1. Table S1: Quality assessment of included studies, using the Newcastle-Ottawa scale. Figure S1: PRISMA flowchart summarizing the results of the literature search. Figure S2: Funnel plot. Figure S3: Sensitivity analysis of ischemic heart disease. Figure S4. Unadjusted risk of ischemic heart disease. Figure S5: Sensitivity analysis of myocardial infarction. Figure S6: Unadjusted risk of myocardial infarction. Figure S7: Sensitivity analysis of acute coronary syndrome. Figure S8: Sensitivity analysis of heart failure. Figure S9: Sensitivity analysis of atrial fibrillation. Figure S10: Unadjusted risk of stroke. Figure S11: Sensitivity analysis of peripheral arterial disease. Figure S12: Sensitivity analysis of diabetes mellitus. Figure S13: Sensitivity analysis of venous thromboembolism. Figure S14: Unadjusted risk of venous thromboembolism. Figure S15: Unadjusted risk of deep vein thrombosis. Figure S16: Unadjusted risk of pulmonary embolism. Figure S17: Sensitivity analysis of cardiovascular mortality. Figure S18: Sensitivity analysis of all-cause mortality. Figure S19: Unadjusted risk of all-cause mortality.

Author Contributions

A.S. conceptualization, supervision, editing. M.S. data extraction, formal analysis, writing—draft and editing. R.H.S. data extraction, formal analysis, writing. M.M.J. data extraction, formal analysis. S.U.A. data extraction, writing. F.J. data extraction. F.A. writing—draft. S.A., S.A.H. and W.R. conceptualization, data extraction. T.J., F.M., S.K. and A.K. writing—draft. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

IRB approval was not needed because this study utilized only previously published, aggregate data and involved no interaction with human subjects or access to identifiable patient information.

Informed Consent Statement

Patient consent was waived due to the nature of the study being observational.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the Research Council of Pakistan (RCOP) for their support along all aspects of conducting this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| IBD | Inflammatory bowel disease |

| CD | Crohn’s disease |

| UC | Ulcerative colitis |

| IBD-U | IBD unclassified |

| IHD | Ischemic heart disease |

| MI | Myocardial infarction |

| AF | Atrial fibrillation |

| HF | Heart failure |

| PAD | Peripheral arterial disease |

| DM | Diabetes mellitus |

| VTE | Venous thromboembolism |

| DVT | Deep vein thrombosis |

| PE | Pulmonary embolism |

| CVD | Cardiovascular disease |

References

- Wang, R.; Li, Z.; Liu, S.; Zhang, D. Global, regional and national burden of inflammatory bowel disease in 204 countries and territories from 1990 to 2019: A systematic analysis based on the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. BMJ Open 2023, 13, e065186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, D.; Jin, Y.; Shao, X.; Xu, Y.; Ma, G.; Jiang, Y.; Hu, D. Global, regional, and national burden of inflammatory bowel disease, 1990–2021: Insights from the global burden of disease 2021. Int. J. Color. Dis. 2024, 39, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knowles, S.R.; Keefer, L.; Wilding, H.; Hewitt, C.; Graff, L.A.; Mikocka-Walus, A. Quality of Life in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-analyses—Part II. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2018, 24, 966–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alvestad, L.; Jelsness-Jørgensen, L.-P.; Goll, R.; Clancy, A.; Gressnes, T.; Valle, P.C.; Broderstad, A.R. Health-related quality of life in inflammatory bowel disease: A comparison of patients receiving nurse-led versus conventional follow-up care. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2022, 22, 1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholas, D.B.; Otley, A.; Smith, C.; Avolio, J.; Munk, M.; Griffiths, A.M. Challenges and strategies of children and adolescents with inflammatory bowel disease: A qualitative examination. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2007, 5, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agca, R.; Smulders, Y.; Nurmohamed, M. Cardiovascular disease risk in immune-mediated inflammatory diseases: Recommendations for clinical practice. Heart 2022, 108, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hansson, G.K. Inflammation, Atherosclerosis, and Coronary Artery Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2005, 352, 1685–1695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Ascenzo, F.; Bruno, F.; Iannaccone, M.; Testa, G.; Filippo, O.D.; Giannino, G.; Caviglia, G.P.; Bernstein, C.N.; De Ferrari, G.M.; Bugianesi, E.; et al. Patients with inflammatory bowel disease are at increased risk of atherothrombotic disease: A systematic review with meta-analysis. Int. J. Cardiol. 2023, 378, 96–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, Y.-F.; Lin, C.-C.; Yin, J.-H.; Chou, C.-H.; Chung, C.-H.; Yang, F.-C.; Tsai, C.-K.; Tsai, C.-L.; Lee, J.T. Increased Risk of Stroke in Patients with Atopic Dermatitis: A Population-based, Longitudinal Study in Taiwan. J. Med. Sci. 2017, 37, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Jia, Y.; Li, F.-R.; Li, Y.; Chen, L.-H.; Yang, H.-H.; Guo, D.; Sun, L.; Shi, M.; Wang, T.; et al. Inflammatory Bowel Disease and Risk of Global Cardiovascular Diseases and Type 2 Diabetes. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2024, 30, 1130–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, X.; Hou, C.; Yang, Z.; Wang, Q.; Li, L. Inflammatory bowel disease and risk of coronary heart disease. Wien. Klin. Wochenschr. 2022, 134, 779–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Duan, T.; Fang, W.; Liu, S.; Wang, C. Analysis of clinical characteristics of mesalazine-induced cardiotoxicity. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 970597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sholter, D.E.; Armstrong, P.W. Adverse effects of corticosteroids on the cardiovascular system. Can. J. Cardiol. 2000, 16, 505–511. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pujades-Rodriguez, M.; Morgan, A.W.; Cubbon, R.M.; Wu, J. Dose-dependent oral glucocorticoid cardiovascular risks in people with immune-mediated inflammatory diseases: A population-based cohort study. PLoS Med. 2020, 17, e1003432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ytterberg, S.R.; Bhatt, D.L.; Mikuls, T.R.; Koch, G.G.; Fleischmann, R.; Rivas, J.L.; Germino, R.; Menon, S.; Sun, Y.; Wang, C.; et al. Cardiovascular and Cancer Risk with Tofacitinib in Rheumatoid Arthritis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022, 386, 316–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Qiao, L.; Yun, X.; Du, F.; Xing, S.; Yang, M. Increased risk of ischemic heart disease and diabetes in inflammatory bowel disease. Z. Gastroenterol. 2021, 59, 117–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fumery, M.; Xiaocang, C.; Dauchet, L.; Gower-Rousseau, C.; Peyrin-Biroulet, L.; Colombel, J.-F. Thromboembolic events and cardiovascular mortality in inflammatory bowel diseases: A meta-analysis of observational studies. J. Crohns Colitis 2014, 8, 469–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Yao, J.; Olén, O.; Halfvarson, J.; Bergman, D.; Ebrahimi, F.; Rosengren, A.; Sundström, J.; Ludvigsson, J.F. Risk of heart failure in inflammatory bowel disease: A Swedish population-based study. Eur. Heart J. 2024, 45, 2493–2504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksson, C.; Sun, J.; Bryder, M.; Bröms, G.; Everhov, Å.H.; Forss, A.; Jernberg, T.; Ludvigsson, J.F.; Olén, O. Impact of inflammatory bowel disease on the risk of acute coronary syndrome: A Swedish Nationwide Cohort Study. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2024, 59, 1122–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alayo, Q.A.; Loftus, E.V.; Yarur, A.; Alvarado, D.; Ciorba, M.A.; de las Fuentes, L.; Deepak, P. Inflammatory Bowel Disease Is Associated with an Increased Risk of Incident Acute Arterial Events: Analysis of the United Kingdom Biobank. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. Off. Clin. Pract. J. Am. Gastroenterol. Assoc. 2023, 21, 761–770.e13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malham, M.; Jansson, S.; Ingels, H.; Jørgensen, M.H.; Rod, N.H.; Wewer, V.; Fox, M.P. Paediatric-onset immune-mediated inflammatory disease is associated with an increased mortality risk—A nationwide study. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2024, 59, 1551–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilly, M.J.; Geurts, S.; Zhu, F.; Bos, M.M.; Ikram, M.A.; de Maat, M.P.M.; de Groot, N.M.S.; Kavousi, M. Autoimmune diseases and new-onset atrial fibrillation: A UK Biobank study. Europace 2023, 25, 804–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; Chou, R.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lo, C.K.-L.; Mertz, D.; Loeb, M. Newcastle-Ottawa Scale: Comparing reviewers’ to authors’ assessments. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2014, 14, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, S.L.; Gartlehner, G.; Mansfield, A.J.; Poole, C.; Tant, E.; Lenfestey, N.; Lux, L.J.; Amoozegar, J.; Morton, S.C.; Carey, T.C.; et al. Table 7, Summary of Common Statistical Approaches to Test for Heterogeneity 2010. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK53317/table/ch3.t2/ (accessed on 25 January 2025).

- Andersohn, F.; Waring, M.; Garbe, E. Risk of ischemic stroke in patients with Crohn’s disease: A population-based nested case-control study. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2010, 16, 1387–1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aniwan, S. Increased Risk of Acute Myocardial Infarction and Heart Failure in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2018, 16, 1607–1615.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baena-Díez, J.M.; Garcia-Gil, M.; Comas-Cufí, M.; Ramos, R.; Prieto-Alhambra, D.; Salvador-González, B.; Elosua, R.; Dégano, I.R.; Peñafiel, J.; Grau, M. Association between chronic immune-mediated inflammatory diseases and cardiovascular risk. Heart Br. Card. Soc. 2018, 104, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernstein, C.N. The Incidence of Arterial Thromboembolic Diseases in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Population-Based Study. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2008, 6, 41–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernstein, C.N.; Nugent, Z.; Targownik, L.E.; Singh, H.; Lix, L.M. Predictors and risks for death in a population-based study of persons with IBD in Manitoba. Gut 2015, 64, 1403–1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Card, T.; Hubbard, R.; Logan, R.F.A. Mortality in inflammatory bowel disease: A population-based cohort study. Gastroenterology 2003, 125, 1583–1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Card, T.R.; Zittan, E.; Nguyen, G.C.; Grainge, M.J. Disease Activity in Inflammatory Bowel Disease Is Associated With Arterial Vascular Disease. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2021, 27, 629–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.J.; Lee, D.H.; Shin, D.W.; Han, K.-D.; Yoon, H.; Shin, C.M.; Park, Y.S.; Kim, N. Patients with inflammatory bowel disease have an increased risk of myocardial infarction: A nationwide study. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2019, 50, 769–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.-J.; Choi, E.-K.; Han, K.-D.; Park, J.; Moon, I.; Lee, E.; Choe, W.-S.; Lee, S.-R.; Cha, M.-J.; Lim, W.-H.; et al. Increased risk of atrial fibrillation in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: A nationwide population-based study. World J. Gastroenterol. 2019, 25, 2788–2798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chu, T.P.C.; Grainge, M.J.; Card, T.R. The risk of venous thromboembolism during and after hospitalisation in patients with inflammatory bowel disease activity. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2018, 48, 1099–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, W.-S.; Lin, C.-L.; Hsu, W.-H.; Kao, C.-H. Inflammatory bowel disease increases the risks of deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism in the hospitalized patients: A nationwide cohort study. Thromb. Res. 2015, 135, 492–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dregan, A.; Charlton, J.; Chowienczyk, P.; Gulliford, M.C. Chronic Inflammatory Disorders and Risk of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus, Coronary Heart Disease, and Stroke. Circulation 2014, 130, 837–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dregan, A.; Chowienczyk, P.; Molokhia, M. Cardiovascular and type 2 diabetes morbidity and all-cause mortality among diverse chronic inflammatory disorders. Heart Br. Card. Soc. 2017, 103, 1867–1873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, L.; Gao, H.; Gao, X.; Wu, W.; Miao, Y.; Zhang, H.; Wang, Y.; Li, M.; Yang, H.; Gao, X.; et al. Risks of Cardiovascular Events in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease in China: A Retrospective Multicenter Cohort Study. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2022, 28, S52–S58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galloway, J.; Barrett, K.; Irving, P.; Khavandi, K.; Nijher, M.; Nicholson, R.; de Lusignan, S.; Buch, M.H. Risk of venous thromboembolism in immune-mediated inflammatory diseases: A UK matched cohort study. RMD Open 2020, 6, e001392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gill, G.S.; Fernandez, S.J.; Malhotra, N.; Mete, M.; Garcia-Garcia, H.M. Major acute cardiovascular events in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Coron. Artery Dis. 2021, 32, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grainge, M.J.; West, J.; Card, T.R. Venous thromboembolism during active disease and remission in inflammatory bowel disease: A cohort study. Lancet Lond. Engl. 2010, 375, 657–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, C.; Magowan, S.; Accortt, N.A.; Chen, J.; Stone, C.D. Risk of arterial thrombotic events in inflammatory bowel disease. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2009, 104, 1445–1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heo, C.M.; Kim, T.J.; Kim, E.R.; Hong, S.N.; Chang, D.K.; Yang, M.; Kim, S.; Kim, Y.-H. Risk of venous thromboembolism in Asian patients with inflammatory bowel disease: A nationwide cohort study. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, W.-S.; Tseng, C.-H.; Chen, P.-C.; Tsai, C.-H.; Lin, C.-L.; Sung, F.-C.; Kao, C.-H. Inflammatory bowel diseases increase future ischemic stroke risk: A Taiwanese population-based retrospective cohort study. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2014, 25, 561–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, E.A.; Han, K.; Chun, J.; Soh, H.; Park, S.; Im, J.P.; Kim, J.S. Increased Risk of Diabetes in Inflammatory Bowel Disease Patients: A Nationwide Population-based Study in Korea. J. Clin. Med. 2019, 8, 343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kappelman, M.D.; Horvath-Puho, E.; Sandler, R.S.; Rubin, D.T.; Ullman, T.A.; Pedersen, L.; Baron, J.A.; Sørensen, H.T. Thromboembolic risk among Danish children and adults with inflammatory bowel diseases: A population-based nationwide study. Gut 2011, 60, 937–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, J.J.; Wang, J.; Huang, Y.-L.; Chou, C.-C.; Wang, L.-H.; Hsu, J.-L.; Bai, C.-H.; Chiou, H.-Y. Increased risk of stroke among patients with ulcerative colitis: A population-based matched cohort study. Int. J. Colorectal Dis. 2014, 29, 805–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.Y.; Cho, Y.S.; Kim, H.-S.; Lee, J.K.; Kim, H.M.; Park, H.J.; Kim, H.; Kim, J.; Kang, D.R. Venous Thromboembolism Risk in Asian Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Population-Based Nationwide Inception Cohort Study. Gut Liver 2022, 16, 555–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirchgesner, J.; Beaugerie, L.; Carrat, F.; Andersen, N.N.; Jess, T.; Schwarzinger, M. Increased risk of acute arterial events in young patients and severely active IBD: A nationwide French cohort study. Gut 2018, 67, 1261–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kristensen, S.L.; Ahlehoff, O.; Lindhardsen, J.; Erichsen, R.; Jensen, G.V.; Torp-Pedersen, C.; Nielsen, O.H.; Gislason, G.H.; Hansen, P.R. Disease Activity in Inflammatory Bowel Disease Is Associated with Increased Risk of Myocardial Infarction, Stroke and Cardiovascular Death—A Danish Nationwide Cohort Study. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e56944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristensen, S.L.; Lindhardsen, J.; Ahlehoff, O.; Erichsen, R.; Lamberts, M.; Khalid, U.; Torp-Pedersen, C.; Nielsen, O.H.; Gislason, G.H.; Hansen, P.R. Increased risk of atrial fibrillation and stroke during active stages of inflammatory bowel disease: A nationwide study. EP Eur. 2014, 16, 477–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.T.; Mahtta, D.; Chen, L.; Hussain, A.; Al Rifai, M.; Sinh, P.; Khalid, U.; Nasir, K.; Ballantyne, C.M.; Petersen, L.A.; et al. Premature Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease Risk Among Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Am. J. Med. 2021, 134, 1047–1051.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Ramirez, Y.; Yano, Y.; Daniel, C.R.; Sharma, S.V.; Brown, E.L.; Li, R.; Moshiree, B.; Loftfield, E.; Lan, Q.; et al. The association between inflammatory bowel disease and all-cause and cause-specific mortality in the UK Biobank. Ann. Epidemiol. 2023, 88, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.-Y.; Chen, Y.-G.; Lin, C.-L.; Huang, W.-S.; Kao, C.-H. Inflammatory Bowel Disease Increases the Risk of Peripheral Arterial Disease: A Nationwide Cohort Study. Medicine 2015, 94, e2381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nocerino, A.; Feathers, A.; Ivanina, E.; Durbin, L.; Swaminath, A. Mortality Risk of Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Case-Control Study of New York State Death Records. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2019, 64, 1604–1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olén, O.; Askling, J.; Sachs, M.C.; Frumento, P.; Neovius, M.; Smedby, K.E.; Ekbom, A.; Malmborg, P.; Ludvigsson, J.F. Increased Mortality of Patients with Childhood-Onset Inflammatory Bowel Diseases, Compared with the General Population. Gastroenterology 2019, 156, 614–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osterman, M.T.; Yang, Y.-X.; Brensinger, C.; Forde, K.A.; Lichtenstein, G.R.; Lewis, J.D. No Increased Risk of Myocardial Infarction Among Patients with Ulcerative Colitis or Crohn’s Disease. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2011, 9, 875–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasada, S.; Rivera, A.; Nishtala, A.; Pawlowski, A.E.; Sinha, A.; Bundy, J.D.; Chadha, S.A.; Ahmad, F.S.; Khan, S.S.; Achenbach, C.; et al. Differential Associations of Chronic Inflammatory Diseases with Incident Heart Failure. JACC Heart Fail. 2020, 8, 489–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rothberg, M.B.; Lindenauer, P.K.; Lahti, M.; Pekow, P.S.; Selker, H.P. Risk factor model to predict venous thromboembolism in hospitalized medical patients. J. Hosp. Med. 2011, 6, 202–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rungoe, C.; Basit, S.; Ranthe, M.F.; Wohlfahrt, J.; Langholz, E.; Jess, T. Risk of ischaemic heart disease in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: A nationwide Danish cohort study. Gut 2013, 62, 689–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setyawan, J.; Mu, F.; Zichlin, M.L.; Billmyer, E.; Downes, N.; Yang, H.; Azimi, N.; Strand, V.; Yarur, A. Risk of Thromboembolic Events and Associated Healthcare Costs in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Adv. Ther. 2022, 39, 738–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, A.; Rivera, A.S.; Chadha, S.A.; Prasada, S.; Pawlowski, A.E.; Thorp, E.; DeBerge, M.; Ramsey-Goldman, R.; Lee, Y.C.; Achenbach, C.J.; et al. Comparative Risk of Incident Coronary Heart Disease Across Chronic Inflammatory Diseases. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2021, 8, 757738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, J.; Roelstraete, B.; Svennberg, E.; Halfvarson, J.; Sundström, J.; Forss, A.; Olén, O.; Ludvigsson, J.F. Long-term risk of arrhythmias in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: A population-based, sibling-controlled cohort study. PLoS Med. 2023, 20, e1004305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, J.; Halfvarson, J.; Appelros, P.; Bergman, D.; Ebrahimi, F.; Roelstraete, B.; Olén, O.; Ludvigsson, J.F. Long-term Risk of Stroke in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Population-Based, Sibling-Controlled Cohort Study, 1969–2019. Neurology 2023, 101, e653–e664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanislav, C.; Trommer, K.; Labenz, C.; Kostev, K. Inflammatory Bowel Disease as a Precondition for Stroke or TIA: A Matter of Crohn’s Disease Rather than Ulcerative Colitis. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2021, 30, 105787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, M.-S.; Lin, C.-L.; Chen, H.-P.; Lee, P.-H.; Sung, F.-C.; Kao, C.-H. Long-term risk of acute coronary syndrome in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: A 13-year nationwide cohort study in an Asian population. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2014, 20, 502–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, M.-T.; Park, S.H.; Matsuoka, K.; Tung, C.-C.; Lee, J.Y.; Chang, C.-H.; Yang, S.-K.; Watanabe, M.; Wong, J.-M.; Wei, S.-C. Incidence and Risk Factor Analysis of Thromboembolic Events in East Asian Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease, a Multinational Collaborative Study. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2018, 24, 1791–1800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yarur, A.J.; Deshpande, A.R.; Pechman, D.M.; Tamariz, L.; Abreu, M.T.; Sussman, D.A. Inflammatory bowel disease is associated with an increased incidence of cardiovascular events. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2011, 106, 741–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, S.; Sun, Y.; Chen, J.; Li, X.; Larsson, S.C. Long-term risk of venous thromboembolism among patients with gastrointestinal non-neoplastic and neoplastic diseases: A prospective cohort study of 484,211 individuals. Am. J. Hematol. 2024, 99, 172–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bröms, G.; Forss, A.; Eriksson, J.; Askling, J.; Eriksson, C.; Halfvarson, J.; Linder, M.; Sun, J.; Westerlund, E.; Ludvigsson, J.F.; et al. Adult-onset inflammatory bowel disease and the risk of venous thromboembolism—A Swedish nationwide cohort study 2007–2021. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 2025, 60, 526–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.-J.; Hsieh, H.-H.; Lin, H.-J.; Lin, C.-L.; Lee, W.-Y.; Chen, C.-H.; Tsai, F.-J.; You, B.-J.; Tien, N.; Lim, Y.-P. Relationship between venous thromboembolism and inflammatory bowel disease in Taiwan: A nationwide retrospective cohort study. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 2025, 25, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, S.; Singh, H.; Loftus, E.V.; Pardi, D.S. Risk of Cerebrovascular Accidents and Ischemic Heart Disease in Patients With Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2014, 12, 382–393.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arvanitakis, K.D.; Arvanitaki, A.D.; Karkos, C.D.; Zintzaras, E.A.; Germanidis, G.S. The risk of venous thromboembolic events in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Gastroenterol 2021, 34, 680–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyal, A.; Jain, H.; Maheshwari, S.; Jain, J.; Odat, R.M.; Saeed, H.; Daoud, M.; Mahalwar, G.; Bansal, K. Association between inflammatory bowel disease and atrial fibrillation: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Cardiol. Heart Vasc. 2024, 53, 101456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamperidis, N.; Kamperidis, V.; Zegkos, T.; Kostourou, I.; Nikolaidou, O.; Arebi, N.; Karvounis, H. Atherosclerosis and Inflammatory Bowel Disease-Shared Pathogenesis and Implications for Treatment. Angiology 2021, 72, 303–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts-Thomson, I.C.; Fon, J.; Uylaki, W.; Cummins, A.G.; Barry, S. Cells, cytokines and inflammatory bowel disease: A clinical perspective. Expert. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2011, 5, 703–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schicho, R.; Marsche, G.; Storr, M. Cardiovascular Complications in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Curr. Drug Targets 2015, 16, 181–188. Available online: https://www.eurekaselect.com/article/64948 (accessed on 25 January 2025). [CrossRef]

- Konstantinou, C.S.; Korantzopoulos, P.; Fousekis, F.S.; Katsanos, K.H. Inflammatory bowel disease and atrial fibrillation: A contemporary overview. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2023, 35, 695–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rehman, K.; Akash, M.S.H. Mechanisms of inflammatory responses and development of insulin resistance: How are they interlinked? J. Biomed. Sci. 2016, 23, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krebs, D.L.; Hilton, D.J. SOCS: Physiological suppressors of cytokine signaling. J. Cell Sci. 2000, 113, 2813–2819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, G.; Xu, Y.; Zheng, T.; Liu, T. Type 2 diabetes and inflammatory bowel disease: A bidirectional two-sample Mendelian randomization study. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 5149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Hu, T.; Hao, H.; Hill, M.A.; Xu, C.; Liu, Z. Inflammatory bowel disease and cardiovascular diseases: A concise review. Eur. Heart J. Open 2022, 2, oeab029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jess, T.; Jensen, B.W.; Andersson, M.; Villumsen, M.; Allin, K.H. Inflammatory Bowel Diseases Increase Risk of Type 2 Diabetes in a Nationwide Cohort Study. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020, 18, 881–888.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baumgart, D.C.; Sandborn, W.J. Crohn’s disease. Lancet Lond. Engl. 2012, 380, 1590–1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristensen, S.L.; Ahlehoff, O.; Lindhardsen, J.; Erichsen, R.; Lamberts, M.; Khalid, U.; Nielsen, O.H.; Torp-Pedersen, C.; Gislason, G.H.; Hansen, P.R. Inflammatory Bowel Disease Is Associated With an Increased Risk of Hospitalization for Heart Failure. Circ. Heart Fail. 2014, 7, 717–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Introduction to Survival Analysis—Sainani—2016—PM&R—Wiley Online Library. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1016/j.pmrj.2016.04.003 (accessed on 25 January 2025).

- Anker, S.D.; von Haehling, S. Inflammatory mediators in chronic heart failure: An overview. Heart Br. Card. Soc. 2004, 90, 464–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sinh, P.; Cross, R. Cardiovascular Risk Assessment and Impact of Medications on Cardiovascular Disease in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2021, 27, 1107–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myocarditis Secondary to Mesalamine-Induced Cardiotoxicity in a Patient with Ulcerative Colitis–Okoro—2018—Case Reports in Medicine—Wiley Online Library. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1155/2018/9813893 (accessed on 25 January 2025).

- Orakzai, A.A.; Khan, O.S.; Sharif, M.H.; Raza, S.S.; Rashid, M.U. S39 Heart Failure as an Adverse Outcome With the Use of Biologic Medications for Crohn’s Colitis: A Pharmacovigilance Study. Off. J. Am. Coll. Gastroenterol. ACG 2023, 118, S11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grillo, T.G.; Almeida, L.R.; Beraldo, R.F.; Marcondes, M.B.; Queiróz, D.A.R.; da Silva, D.L.; da Quera, R.; Baima, J.P.; Saad-Hossne, R.; Sassaki, L.Y. Heart failure as an adverse effect of infliximab for Crohn’s disease: A case report and review of the literature. World J. Clin. Cases 2021, 9, 10382–10391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, J.-S.; Wang, M.; Chen, N.; Sun, B.; Zhang, Q.-B.; Li, Y.; Huang, M.-J. Association between inflammatory bowel disease and risk of stroke: A systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Front. Neurol. 2023, 14, 1204727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, J.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Y.J.; Yin, Y.; Wang, Z.; Che, X.; Chen, M.; Liang, J.; Wu, K.C. Incidence and disease-related risk factors for cerebrovascular accidents in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Dig. Dis. 2023, 24, 504–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boccatonda, A.; Balletta, M.; Vicari, S.; Hoxha, A.; Simioni, P.; Campello, E. The Journey Through the Pathogenesis and Treatment of Venous Thromboembolism in Inflammatory Bowel Diseases: A Narrative Review. Semin. Thromb. Hemost. 2022, 49, 744–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, R.A.; Koh, A.Y.; Zia, A. The gut microbiome and thromboembolism. Thromb. Res. 2020, 189, 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santana, P.T.; Rosas, S.L.B.; Ribeiro, B.E.; Marinho, Y.; de Souza, H.S.P. Dysbiosis in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Pathogenic Role and Potential Therapeutic Targets. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 3464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, N.N.; Wass, S.; Hajjari, J.; Heisler, A.C.; Malakooti, S.; Janus, S.E.; Al-Kindi, S.G. Proportionate Cardiovascular Mortality in Chronic Inflammatory Disease in Adults in the United States From 1999 to 2019. J. Clin. Rheumatol. Pr. Rep. Rheum. Musculoskelet. Dis. 2022, 28, 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, H.N.; Ibrahim, R.; Sainbayar, E.; Aiti, D.; Mouhaffel, R.; Shahid, M.; Ozturk, N.B.; Olson, A.; Ferreira, J.P.; Lee, K. Ischemic heart disease mortality in individuals with inflammatory bowel disease: A nationwide analysis of disparities in the United States. Cardiovasc. Revascularization Med. Mol. Interv. 2024, 65, 46–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).