Abstract

Celiac disease (CeD) is an immune-mediated enteropathy triggered by gluten in genetically susceptible individuals, with a heterogeneous clinical spectrum spanning classical gastrointestinal symptoms, extraintestinal manifestations, and subclinical forms. We synthesize contemporary epidemiology, immunopathogenesis, and the updated 2025 European Society for the Study of Coeliac Disease diagnostic framework. Adaptive responses to deamidated gliadin peptides presented by human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-DQ2/DQ8, together with interleukin-15-driven activation of intraepithelial lymphocytes (IELs), culminate in villous atrophy, crypt hyperplasia, and increased IELs. Serology centered on tissue transglutaminase immunoglobulin A (tTG-IgA) with total immunoglobulin A assessment remains first-line, complemented by standardized duodenal sampling (≥4 distal + 2 bulb biopsies) and selective HLA typing. The guidelines conditionally endorse a no-biopsy pathway for adults <45 years with tTG-IgA ≥10× upper limit of normal confirmed on a second sample, emphasizing shared decision-making and exclusion of red flags. We delineate differential diagnoses (tropical sprue, Crohn’s disease, common variable immunodeficiency, small intestinal bacterial overgrowth) and contrast CeD with non-celiac gluten sensitivity, which lacks villous atrophy, disease-specific serology, and HLA association. Emerging tools (immunohistochemistry, CD3/CD8/γδ IELs, video capsule endoscopy, confocal laser endomicroscopy) and the limitations of salivary/fecal assays are reviewed. Early detection improves quality of life and reduces healthcare utilization. Future directions include artificial intelligence-assisted imaging, molecular immunophenotyping, and non-dietary therapeutics.

1. Introduction

Celiac disease (CeD) is a chronic autoimmune enteropathy triggered by the ingestion of gluten, a protein present in wheat, barley, and rye, in genetically susceptible individuals. Gluten exposure induces an immune-mediated reaction that damages the small intestinal mucosa, leading to villous atrophy, crypt hyperplasia, and infiltration of inflammatory cells within the lamina propria [1].

Globally, CeD affects approximately 1.4% of the population, although prevalence varies by region: 1.3% in South America, 0.5% in Africa and North America, 1.8% in Asia, and 0.8% in Europe and Oceania [2,3]. The disease can occur at any age and is more frequent in females than in males (0.6% vs. 0.4%; p < 0.001) [3]. Moreover, CeD is significantly more prevalent in children than in adults (0.9% vs. 0.5%; p < 0.001) [2,3]. Recent studies suggest that the prevalence of CeD remains underestimated due to its heterogeneous clinical presentation, which may sometimes lead to misdiagnosis as irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) [4].

The clinical spectrum of CeD is highly heterogeneous, encompassing both gastrointestinal and extraintestinal manifestations [5,6,7]. Furthermore, the clinical presentation differs between children and adults [5,6,7]. In children, the disease typically manifests with recurrent abdominal pain and growth retardation, whereas adults often present with chronic diarrhea and steatorrhea as the initial symptoms [5,6,7]. A recent meta-analysis including 23 studies reported that only 11.04% of newly diagnosed CeD patients were underweight, while 18.42% were overweight and 11.78% were obese [4].

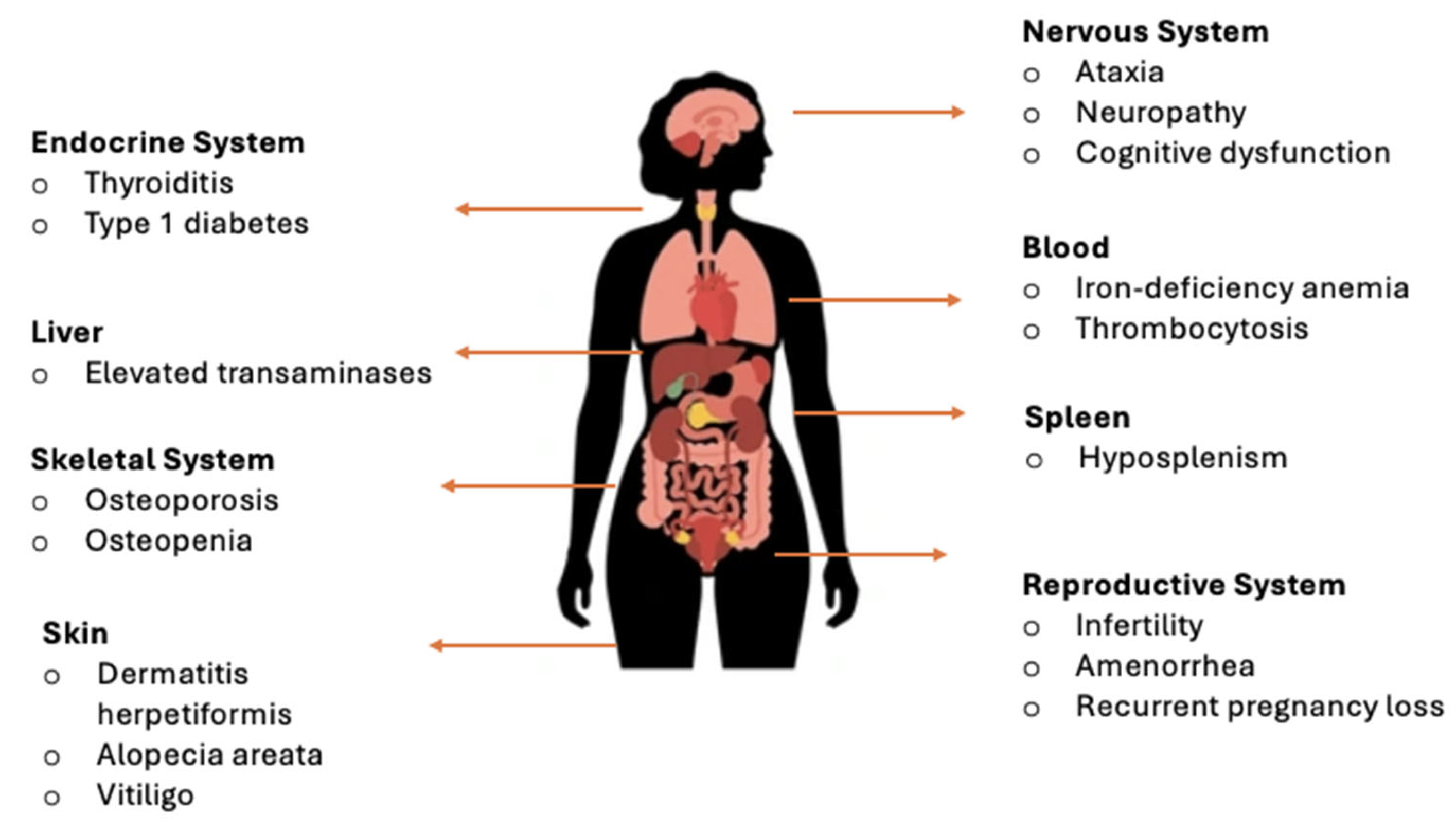

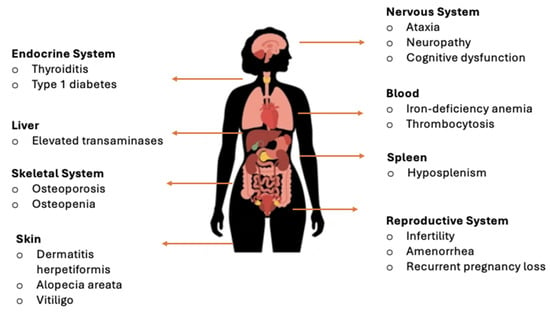

Although CeD was historically associated primarily with gastrointestinal symptoms, many adult patients present with atypical or extraintestinal manifestations (Figure 1) [8,9,10]. These diverse clinical presentations frequently complicate diagnosis, as symptoms may overlap with other gastrointestinal or systemic conditions. Additionally, a considerable proportion of individuals with CeD remain asymptomatic or display only non-classical forms, underscoring the need for heightened clinical awareness and timely recognition.

Figure 1.

Extraintestinal manifestations of CeD by organ systems [8,9,10].

2. Pathophysiology of CeD

The principal environmental trigger of CeD is gluten. Certain peptides derived from gliadin are resistant to complete digestion in the gastrointestinal tract and may cross the intestinal epithelium, particularly under conditions of increased intestinal permeability. Gliadin belongs to the broader family of cereal prolamins, which are alcohol-soluble storage proteins present in various grains, including zein (maize), gliadin (wheat), kafirin (sorghum), hordein (barley), secalin (rye), and avenin (oats) [11]. The relative abundance and structural composition of these prolamins vary across cereals, with gliadin and glutenin accounting for 80–85% of wheat proteins, zein representing approximately 80% of maize protein, kafirin comprising 70–90% of sorghum protein, hordein constituting 35–55% of barley protein, secalin being the main storage protein in rye, and avenin accounting for 10–15% of oat seed protein [11]. Prolamins are characterized by a high content of nonpolar amino acids and marked hydrophobicity, properties that influence their physicochemical behavior, digestibility, and biological interactions [11]. These structural features help explain why different cereals may induce distinct adverse reactions and underscore the relevance of prolamin composition in understanding cereal-related immune responses [11].

A strong genetic predisposition exists, with more than 90% of affected individuals carrying the HLA-DQ2 allele and most of the remainder expressing HLA-DQ8. Gluten-derived peptides are presented to CD4+ T lymphocytes by HLA class II molecules on antigen-presenting cells, thereby initiating an adaptive immune response [12].

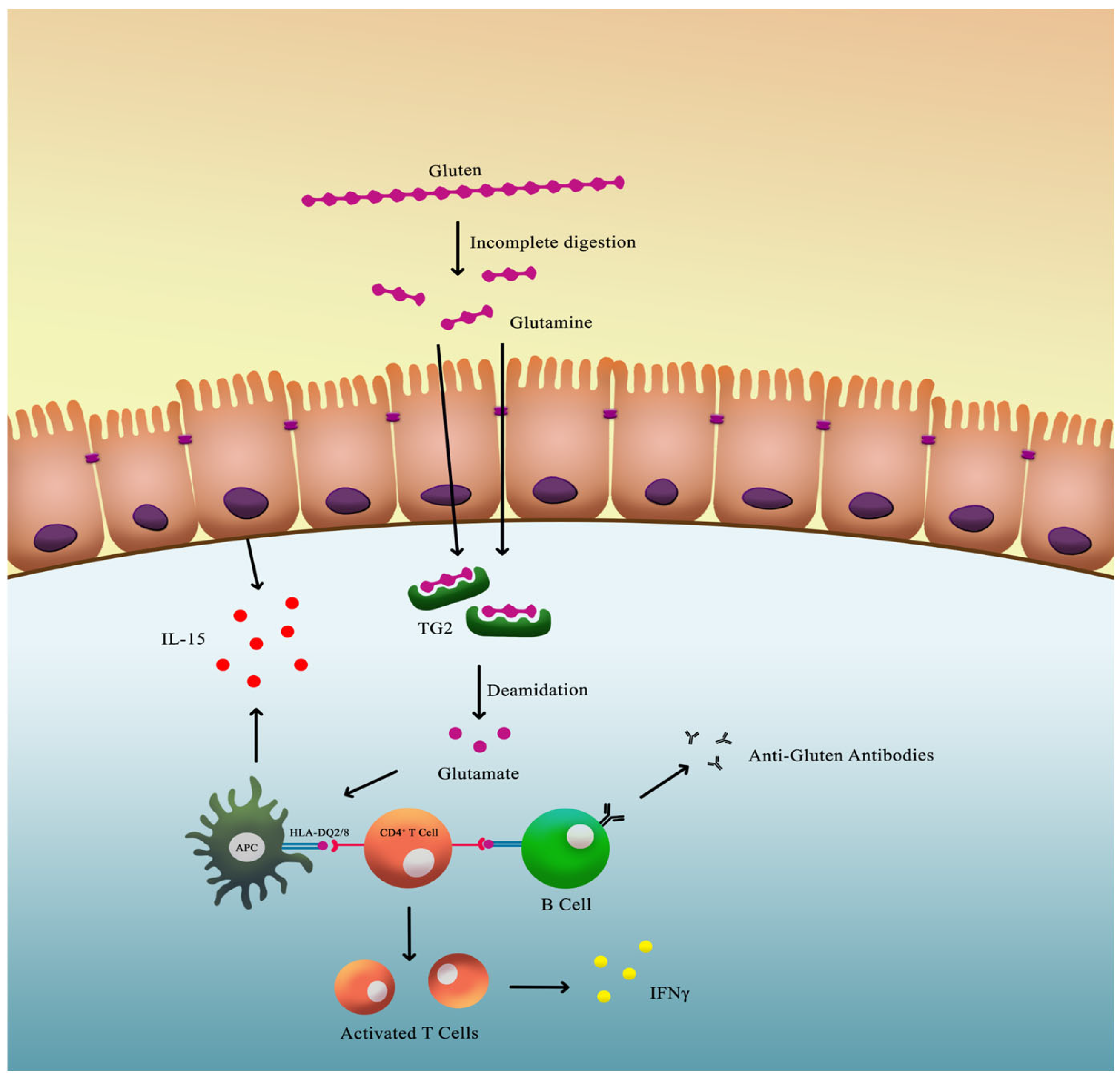

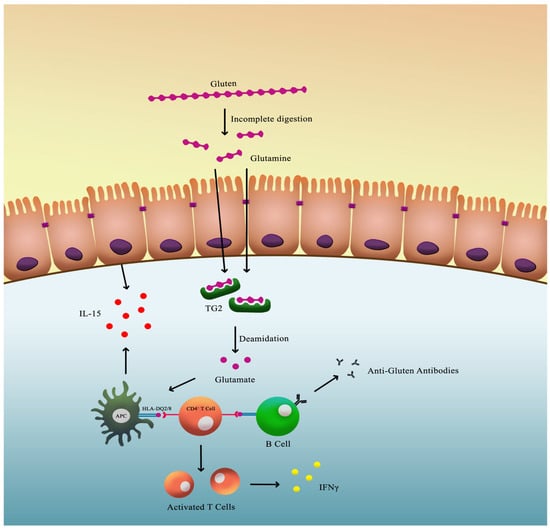

Once these peptides breach the intestinal barrier, they undergo deamidation by the enzyme tissue transglutaminase 2 (TG2), converting specific glutamine residues into glutamate. This modification increases the peptides’ binding affinity for HLA-DQ2 or HLA-DQ8 molecules, enhancing T-cell activation within the lamina propria of the small intestine. The activated T cells release pro-inflammatory cytokines such as interferon-γ, which contribute to mucosal injury and villous atrophy (Figure 2) [13,14,15,16].

Figure 2.

Pathophysiology of CeD.

Innate immunity also contributes significantly to the pathogenesis of CeD. Gluten-derived peptides can directly stimulate intestinal epithelial cells to release interleukin-15 (IL-15). Elevated IL-15 levels activate intraepithelial lymphocytes (IELs), which acquire cytotoxic properties and induce apoptosis of enterocytes expressing stress molecules, thereby exacerbating villous atrophy (Figure 2) [14,15,16].

Additionally, the interaction between TG2 and gluten peptides results in the formation of antigenic complexes that are internalized by B cells. This process triggers the production of anti-TG2 autoantibodies, which are highly specific for CeD and serve as a key diagnostic marker [17].

The culmination of these innate and adaptive immune responses leads to intestinal mucosal damage, resulting in nutrient malabsorption and the wide range of clinical manifestations observed in CeD.

3. Non-Celiac Gluten Sensitivity: Overview

Given the expanding spectrum of gluten-related disorders, it is essential to contrast CeD with Non-Celiac Gluten Sensitivity. Non-Celiac Gluten Sensitivity (NCGS) is an increasingly recognized clinical condition characterized by a spectrum of intestinal and extraintestinal symptoms that occur after the ingestion of gluten-containing products, despite the absence of either CeD or wheat allergy (WA). Once regarded as anecdotal or psychosomatic, NCGS has gained legitimacy over the past decade through a growing body of clinical and immunological evidence supporting its existence as a distinct clinical entity [17,18]. Nevertheless, its definition remains challenging due to the absence of standardized diagnostic criteria and reliable biomarkers [18,19].

Epidemiological studies estimate that NCGS affects between 0.6% and 13% of the general population, depending on diagnostic methods and geographic location [19,20,21]. It occurs more frequently in women than in men, with female-to-male ratios approaching 6:1 [22]. Most patients report symptom onset in their third or fourth decade of life, although the condition may be underdiagnosed in both older adults and children [23].

The clinical presentation of NCGS is highly variable, complicating both diagnosis and management. Gastrointestinal symptoms typically include abdominal bloating, discomfort, diarrhea, and altered bowel habits, often mimicking IBS. Unlike IBS, however, symptoms in NCGS are closely associated with the ingestion of gluten or wheat-containing foods. Many patients also experience systemic complaints, including fatigue, cognitive impairment (“brain fog”), mood disturbances, and headaches. Musculoskeletal pain and dermatologic reactions have been reported in a significant proportion of cases [24,25,26].

Diagnosis of NCGS is based on the exclusion of other conditions rather than the identification of specific biomarkers. The first step involves ruling out CeD through serologic testing for anti-transglutaminase antibodies (anti-tTG) and anti-endomysial antibodies (EMA-IgA), with duodenal biopsy if indicated. WA should also be excluded by skin prick tests or serum-specific IgE assays [27]. When both are negative, NCGS can be considered. Although the double-blind, placebo-controlled gluten challenge remains the diagnostic gold standard, it is rarely feasible in routine practice. Instead, structured elimination and reintroduction protocols, such as those proposed by the Salerno criteria, are commonly employed to establish a presumptive diagnosis [28,29].

The pathophysiology of NCGS remains incompletely understood. Unlike CeD, which involves adaptive immune activation and villous atrophy, NCGS appears to engage components of the innate immune system. Some studies have demonstrated increased intestinal permeability and immune cell activation in affected individuals, although findings remain inconsistent across cohorts [30]. Moreover, gluten may not be the sole trigger. Other wheat components, such as amylase-trypsin inhibitors (ATIs), can activate toll-like receptor 4-mediated innate immune pathways and contribute independently to symptom generation [31]. Additionally, fermentable short-chain carbohydrates (FODMAPs) found in wheat, particularly fructans, have been implicated in symptom development, suggesting an overlap with functional gastrointestinal disorders such as IBS [32,33,34].

The mainstay of therapy for NCGS is a gluten-free diet (GFD), which typically leads to symptom improvement within days to weeks of gluten withdrawal [35]. However, the sustainability and long-term nutritional adequacy of a strict GFD raise concerns. Exclusion of gluten-containing grains may reduce dietary intake of fiber, iron, B vitamins, and other essential micronutrients [36]. Furthermore, prolonged adherence to a GFD may alter gut microbial composition, potentially impacting immune regulation and gastrointestinal homeostasis [37].

For these reasons, dietary management of NCGS should be individualized and supervised by a dietitian experienced in gluten-related disorders. In cases with partial response to GFD, a low-FODMAP dietary approach may be considered to identify additional triggers. This combined strategy reflects the clinical overlap between NCGS and functional gastrointestinal syndromes and enables more personalized treatment.

Despite increasing awareness, NCGS remains a complex and poorly defined disorder. Further research is needed to clarify its pathogenesis, improve diagnostic precision, and develop targeted therapeutic approaches that extend beyond generalized dietary restriction.

4. Diagnostic Tools and Challenges

4.1. Serological Tests and Their Role

Serological tests play a very important role in the diagnosis and management of CeD, serving as initial screening tools and monitoring instruments during treatment. These tests detect specific antibodies produced in response to gluten ingestion in genetically predisposed individuals.

4.1.1. Key Serological Tests

(1) Anti-Tissue Transglutaminase Antibodies (tTG-IgA and tTG-IgG): The tTG-IgA test is the most commonly used and recommended initial screening tool for CeD due to its high sensitivity and specificity. It detects IgA antibodies against tissue transglutaminase, an enzyme involved in gluten metabolism [38]. The 2025 guidelines of the European Society for the Study of Coeliac Disease (ESsCD) recommend IgA anti-tissue transglutaminase (tTG-IgA) as the primary screening test for CeD at any age, provided that the patient is not following a gluten-free diet [39]. In addition, the same guidelines advise the concomitant measurement of total serum IgA to exclude selective IgA deficiency [39].

(2) Anti-Endomysial Antibodies (EMA-IgA): EMA-IgA testing detects antibodies targeting the endomysium, the connective tissue that surrounds muscle fibers. Although it is highly specific for CeD, the test is more labor-intensive and relies more heavily on operator interpretation than tTG-IgA testing [40]. However, according to the ESsCD, EMA-IgA testing may be reserved for cases with an unclear diagnosis, such as patients with other autoimmune or liver diseases, prior to performing duodenal biopsies [39].

(3) Anti-Deamidated Gliadin Peptide Antibodies (DGP-IgA and DGP-IgG): DGP antibody tests identify antibodies against deamidated gliadin peptides [41]. DGP-IgA and DGP-IgG antibodies demonstrate high specificity but have a lower predictive value than tTG antibodies for the early diagnosis of CeD [41]. Moreover, isolated positivity of DGP IgA/IgG antibodies in low-risk patients predicts the presence of CeD in only 15% of cases, with the majority representing false-positive results [42]. In individuals with a confirmed total IgA deficiency, CeD serology should rely on IgG-based assays, including tTG-IgG or DGP-IgG [39]. Because these tests exhibit reduced sensitivity, a negative IgG result cannot reliably rule out the diagnosis [39]. For patients who display clinical features of malabsorption suggestive of CeD, it is advised to perform an upper gastrointestinal endoscopy with duodenal biopsies, irrespective of the IgG serologic findings [39].

4.1.2. Assay Methodology Considerations (ELISA vs. CLIA)

Serologic assays for CeD are performed using either enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA) or chemiluminescent immunoassays (CLIA). CLIA methods generally provide a broader analytical range and enhanced automation compared with ELISA, which may influence antibody titers and diagnostic thresholds. This distinction becomes particularly relevant when considering biopsy-free diagnosis, where cut-off values vary significantly across platforms—from 10× upper limit of normal (ULN) to 30× ULN—as highlighted in recent studies and guideline discussions [38,39,40,41]. These methodological differences warrant cautious interpretation of tTG-IgA titers, especially when applying non-biopsy diagnostic algorithms.

4.2. Duodenal Biopsy—When and How?

When CeD is suspected, the histological confirmation using duodenal biopsy remains the diagnostic gold standard. Biopsies are best taken from both the distal duodenum and the duodenal bulb, as the bulb may be the sole site of histological damage in up to 10% of cases [43,44]. The technique of the biopsy is also very important: multiple specimens are needed for an accurate interpretation. Current guidelines recommend at least four biopsies from the distal duodenum and two from the bulb [39]. Orientation and fixation quality influence detection of architectural changes, such as villous atrophy or crypt hyperplasia, particularly in borderline histological presentations.

Marsh-Oberhuber and Corazza-Villanacci Classifications

Two major histopathological classification systems dominate the assessment of mucosal injury in CeD: the Marsh-Oberhuber and the Corazza-Villanacci systems. The Marsh system (further elaborated by Oberhuber) ranges from type 0 (normal mucosa) to type 4 (total villous atrophy), with additional subtypes based on severity, but researchers argue that its granularity can lead to interobserver variability [45,46]. Regarding the cut-off value for intraepithelial lymphocytes (IELs) used to differentiate lesion types according to the Marsh–Oberhuber classification, the Bucharest Consensus 2025 [47] recommends lowering this threshold to 20 IELs per 100 enterocytes, instead of the traditionally applied cut-off of 30 IELs [47]. The Corazza-Villanacci classification offers a streamlined alternative, grouping findings into type A (non-atrophic) and type B (atrophic) lesions. Both systems are complementary when used in conjunction with clinical and serological data [45,46]. Their correct application remains essential for standardization across pathology reports and multicenter studies. Table 1 illustrates a summary of the differences between Marsh-Oberhuber and Corazza-Villanacci classifications.

Table 1.

Differences between Marsh-Oberhuber and Corazza-Villanacci classifications (intraepithelial lymphocytes) [45,46,47,48].

The ESsCD supports the continued use of both the Marsh–Oberhuber and Corazza–Villanacci classifications; however, the latter is preferred for routine clinical reporting due to its improved interobserver reproducibility, while the Marsh–Oberhuber system remains valuable for research purposes [39]. The guidelines also emphasize detailed reporting of IEL density, crypt hyperplasia, and the degree of villous atrophy, together with the number and site of biopsies examined [39]. In cases with negative serology and Marsh I lesions, CeD is considered unlikely, and alternative causes of lymphocytic duodenitis should be explored [39]. Conversely, positive serology with Marsh I histology may indicate early or potential CeD [39]. Finally, integration of histological, serological, and genetic findings is mandatory for accurate diagnosis, and emerging digital pathology tools, such as the Celiac Histopathology Integrated Score (CeD-HIS), are expected to improve standardization in multicenter studies [39].

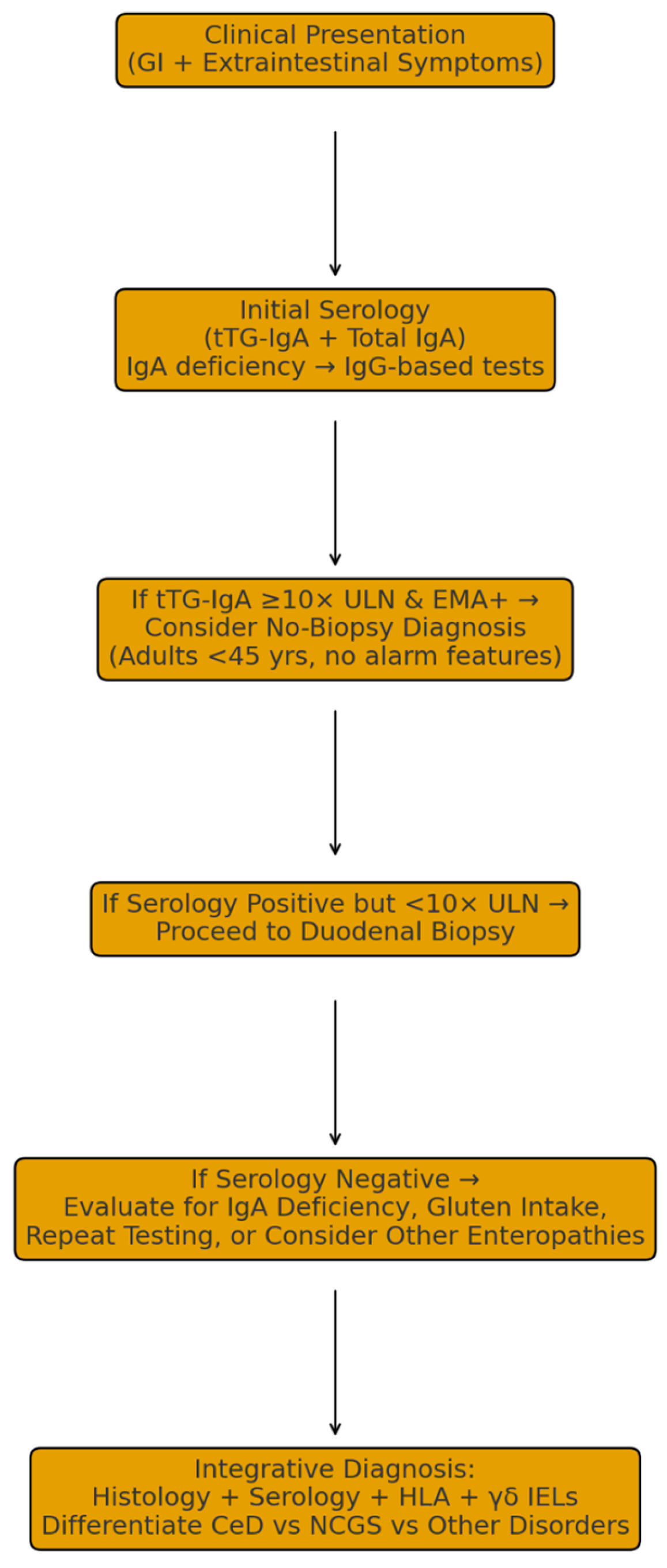

The 2025 ESsCD guidelines introduce a significant refinement in the diagnostic approach to CeD in adults. While positive CeD-specific serology (IgA anti-TG2) in conjunction with Marsh-II or Marsh-III histological lesions remains the diagnostic gold standard, a no-biopsy diagnostic pathway is now conditionally accepted in carefully selected cases [39]. Specifically, adults under 45 years of age with IgA anti-TG2 titers ≥10× the ULN may be diagnosed without duodenal biopsy, provided that the serologic result is confirmed in an independent second sample and the patient remains on a gluten-containing diet during testing [39].

This approach, endorsed by a high level of expert agreement, aims to reduce unnecessary invasive procedures while maintaining diagnostic accuracy. However, it should be implemented exclusively in secondary care settings, with shared decision-making between clinician and patient, and avoided in the presence of clinical red flags suggestive of alternative diagnoses. Until additional safety data are available, the no-biopsy strategy should remain restricted to younger adults and applied with caution. Overall, these recommendations reflect a more patient-centered, evidence-based, and pragmatic diagnostic framework, balancing precision with procedural efficiency in the management of adult CeD.

4.3. Immunohistochemical and Molecular Markers

In diagnostically challenging cases, beyond conventional hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining, immunohistochemical (IHC) analysis is increasingly utilized to enhance the accuracy of CeD diagnosis. IHC markers such as CD3 and CD8 facilitate the quantification and characterization of IELs, supporting the distinction between CeD, NCGS, and other inflammatory enteropathies [48,49]. In addition, γδ T-cell receptor staining can provide further diagnostic specificity, as an increased proportion of γδ IELs is strongly associated with CeD and may persist even after the initiation of a GFD [50]. According to the 2025 ESsCD guidelines, IHC assessment is particularly valuable when histologic findings are borderline or when IEL counts exceed 25 per 100 enterocytes without overt villous atrophy [39]. In such cases, IHC can help confirm the diagnosis or prompt consideration of alternative etiologies, such as autoimmune enteropathy, infection, or drug-induced enteritis [39].

Molecular testing for HLA-DQ2 and HLA-DQ8 alleles remains an important adjunctive tool, particularly in seronegative patients or in those already adhering to a GFD before testing [51,52]. Although these genetic markers are not diagnostic, since 30–40% of the general population carries at least one of these alleles, the absence of both HLA-DQ2 and HLA-DQ8 virtually excludes CeD. The 2025 ESsCD guidelines further emphasize that HLA typing should be reserved for diagnostically ambiguous cases, including those with discordant serology and histology, suspected seronegative CeD, or villous atrophy of unclear etiology [39].

4.4. Emerging Non-Invasive Diagnostic Techniques

Recent technological advancements have driven the development of innovative non-invasive diagnostic tools for CeD. Among the most promising modalities are video capsule endoscopy (VCE) and confocal laser endomicroscopy (CLE), both of which enable in vivo visualization of the small intestinal mucosa without the need for sedation or mucosal trauma [53,54,55].

VCE demonstrates high sensitivity in detecting villous flattening, a hallmark feature of CeD, by allowing visualization of the entire small bowel, an area that may be incompletely assessed by traditional endoscopic techniques. According to recent studies, VCE serves as a valuable adjunct in patients with unexplained malabsorptive symptoms and negative or inconclusive standard investigations [56,57]. Although not yet recommended for routine diagnosis in the 2025 ESsCD guidelines, VCE may be particularly useful when biopsy sampling is not feasible or contraindicated, such as in patients with limited access to endoscopy or those who are unable to tolerate invasive procedures [39].

Similarly, CLE has emerged as an advanced optical imaging technique capable of providing real-time, high-resolution microscopic visualization of the intestinal mucosa during endoscopy. CLE allows detailed assessment of mucosal architecture, enabling the detection of villous atrophy and epithelial alterations associated with CeD at a cellular level. Studies demonstrated that CLE facilitates precise evaluation of mucosal injury and may potentially reduce the need for additional biopsies by enabling targeted histological sampling [58,59].

Beyond imaging, emerging salivary and fecal biomarkers have shown potential as non-invasive diagnostic indicators of CeD. Tissue transglutaminase-derived peptides have been identified in both saliva and fecal samples and can be detected using biosensor-based assays, offering an alternative to conventional serologic or biopsy-based testing. Despite ongoing research into non-invasive diagnostic approaches, the 2025 ESsCD guidelines emphasize that salivary and fecal tests for CeD currently demonstrate low sensitivity and specificity. Consequently, their use in routine clinical practice is not recommended. These assays should be limited to research settings until their analytical validity and diagnostic accuracy are further established [39].

Although these innovative diagnostic techniques are not yet ready to replace biopsy-based standards entirely, they represent a major advancement in the non-invasive assessment of CeD. As these technologies continue to evolve and become more widely accessible, they are expected to enhance diagnostic accuracy, patient comfort, and early detection, particularly in complex or atypical cases.

5. Differential Diagnosis: Other Enteropathies

A critical aspect of evaluating suspected CeD is distinguishing it from other small bowel disorders that may mimic its clinical or histological profile. These include tropical sprue, Crohn’s disease, common variable immunodeficiency (CVID), and small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO) [60,61,62,63,64,65,66]. Each presents with variable degrees of villous atrophy and lymphocytic infiltration but lacks the autoimmune serological and genetic hallmarks of CeD—Table 2.

Table 2.

Differential Diagnosis of CeD [60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67].

Tropical sprue shares overlapping histological findings such as villous atrophy and crypt hyperplasia but is typically associated with a history of residence or travel to tropical regions. Unlike CeD, tropical sprue usually responds favorably to antibiotic therapy and nutritional supplementation [62,63].

Crohn’s disease can involve the small intestine and mimic CeD histologically. However, Crohn’s disease typically exhibits patchy mucosal inflammation, granuloma formation, and transmural involvement, findings not characteristic of CeD [60].

CVID may also manifest with villous atrophy, malabsorption, and chronic diarrhea. It is differentiated from CeD by hypogammaglobulinemia, recurrent infections, and the absence of CeD-specific antibodies [64,65].

SIBO can cause mild villous blunting and increased IELs, but unlike CeD, serological markers are negative, and diagnosis is confirmed by an elevated hydrogen or methane breath test [66,67].

Another condition that may present clinically with chronic diarrhea and villous atrophy on histopathological examination is drug-induced enteropathy [68]. Medications implicated in this form of enteropathy include angiotensin receptor blockers, olmesartan medoxomil, colchicine, neomycin, azathioprine, methotrexate, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs [68]. Differentiating this condition from CeD is crucial, as the therapeutic management is entirely different: lesions typically improve or resolve only after discontinuation of the offending agent, whereas a gluten-free diet provides no clinical benefit in these cases [68,69].

A precise differential diagnosis is essential to avoid unnecessary dietary restrictions and to ensure that patients receive targeted therapy for the underlying cause of enteropathy.

6. Celiac Disease vs. Non-Celiac Gluten Sensitivity

The histopathological distinction between CeD and NCGS primarily lies in the degree of mucosal injury and the nature of the immune response. CeD is characterized by autoimmune-mediated enteropathy with marked villous atrophy, crypt hyperplasia, and a significant increase in IELs, typically exceeding 25 per 100 enterocytes [70]. These changes correspond to Marsh type 2 or 3 lesions, representing moderate to severe mucosal damage resulting from an adaptive immune response to gluten in genetically predisposed individuals carrying HLA-DQ2 or HLA-DQ8 alleles [70,71]. In contrast, NCGS exhibits minimal or no mucosal abnormalities. The histological hallmark is the absence of villous atrophy, often accompanied by Marsh type 0–1 lesions. A mild increase in IELs may be observed, but the count generally remains below 25 IELs per 100 enterocytes and is not associated with crypt hyperplasia or structural distortion [71]. This limited histological involvement suggests that NCGS does not represent an autoimmune-driven enteropathy.

Immunological markers provide another key differentiating feature. In CeD, the autoimmune nature of the disease is reflected by the presence of disease-specific antibodies (anti-tTG, EMA) and the strong association with HLA-DQ2/DQ8 genotypes [72,73,74,75]. Conversely, NCGS lacks both these serological markers and genetic predisposition, supporting the concept that its pathophysiology is non-autoimmune, possibly involving innate immune activation rather than adaptive mechanisms [73,74,75].

The distribution pattern of IELs also aids in differentiation: CeD typically shows diffuse and uniform infiltration across the mucosal surface, whereas NCGS may exhibit a patchy or irregular pattern, particularly in early or subtle lesions [76,77].

IHC studies using CD3 and CD8 markers have further refined diagnostic accuracy by identifying the nature and density of IELs. These markers are more prominently expressed in CeD, consistent with pronounced T-cell activation, while NCGS demonstrates milder or inconsistent expression [50,72]. Genetically, HLA-DQ2/DQ8 positivity remains a nearly universal finding in CeD, confirming its immunogenetic basis. These alleles are present only in a minority of NCGS patients and at frequencies closer to, or only modestly above, the general population, in contrast to the near-universal positivity in CeD [78,79].

NCGS patients generally lack malabsorptive features, and their symptoms are milder and more transient [80,81,82,83]. Although the clinical features of the two conditions overlap, both presenting with abdominal discomfort, bloating, fatigue, or altered bowel habits, CeD is more frequently associated with chronic diarrhea, malabsorption, and weight loss, reflecting extensive mucosal injury [82,83,84,85].

In summary, while CeD and NCGS share symptomatic similarities, their histological, serological, and genetic profiles are distinct. The absence of villous atrophy and autoimmune markers in NCGS, coupled with its lack of HLA-DQ2/DQ8 association, provides crucial diagnostic differentiation. Further investigation into the immunological and molecular mechanisms underlying NCGS will be essential to refine its diagnostic criteria and optimize management strategies. Table 3 summarizes histological differences between the two entities.

Table 3.

Histological differences between CeD and NCGS [80,81,82,83,84,85].

7. Literature Search Strategy

This article is a narrative review synthesizing recent evidence on the epidemiology, pathophysiology, diagnosis, and differential considerations of CeD and NCGS. A targeted literature search was conducted in PubMed, Embase, and Google Scholar between January 2010 and December 2025. Search terms included combinations of: “celiac disease,” “coeliac,” “non-celiac gluten sensitivity,” “gluten-related disorders,” “intestinal biopsy,” “Marsh classification,” “ESsCD guidelines,” “γδ intraepithelial lymphocytes,” “video capsule endoscopy,” “confocal laser endomicroscopy,” “artificial intelligence endoscopy,” and “gluten-free diet.”

Only English-language publications were considered. Priority was given to clinical guidelines, meta-analyses, systematic reviews, and recent original studies with direct relevance to diagnosis or differential diagnosis. Reference lists of key articles were screened to identify additional studies. Because this is a non-systematic narrative review, no formal inclusion/exclusion criteria or quantitative synthesis was performed.

8. Discussion

8.1. The Significance of Early Detection

Early identification of CeD remains a crucial determinant of clinical outcomes. Timely diagnosis followed by the initiation of a strict GFD has been associated with marked improvements in patients’ quality of life, nutritional status, and systemic health. Adherence to a GFD can reverse key pathological processes, including systemic inflammation, reduced bone mineral density, and gastrointestinal symptoms, and can promote complete mucosal recovery and restoration of nutrient absorption, particularly when implemented before extensive villous atrophy develops [86,87,88].

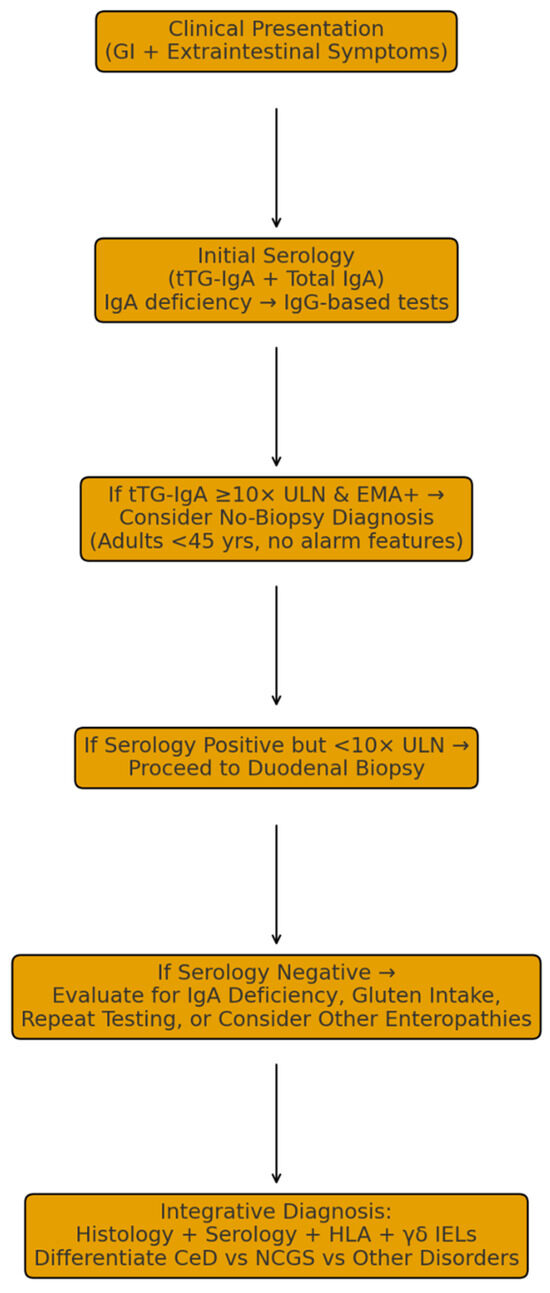

Patients diagnosed early frequently report less gastrointestinal discomfort, reduced fatigue and cognitive impairment (“brain fog”), and overall enhancement in physical and emotional well-being [87,88]. Moreover, early detection substantially reduces healthcare utilization by decreasing the frequency of misdiagnoses, redundant investigations, and hospital admissions, thus lowering the overall medical and economic burden of the disease [35,84,85]. Collectively, these findings underscore the importance of heightened clinical vigilance and routine screening in at-risk populations to achieve timely diagnosis and prevent long-term complications. Figure 3 provides a graphical summary of the clinical pathways for CeD evaluation.

Figure 3.

Graphical Summary of Clinical Pathways for CeD Evaluation.

8.2. Limitations of Current Diagnostic Approaches

Despite significant progress in diagnostic techniques, several challenges continue to hinder the accurate and timely identification of CeD. The clinical presentation of CeD is remarkably heterogeneous, encompassing classical gastrointestinal manifestations, extraintestinal symptoms, and asymptomatic or subclinical forms. This variability frequently leads to delayed or missed diagnoses, even in specialized settings.

8.2.1. Serological Testing

Serologic assays are indispensable screening tools but are not infallible. False-negative results may occur, particularly in patients with selective immunoglobulin A (IgA) deficiency, a condition found more frequently among individuals with CeD. This deficiency reduces the reliability of IgA-based tests such as tTG-IgA or EMA-IgA.

Furthermore, seronegative CeD presents an additional diagnostic dilemma; some patients exhibit classical histopathological features of CeD despite negative serologic results, necessitating reliance on histology and genetic testing for confirmation [88].

8.2.2. Histological Assessment

While duodenal biopsy remains the diagnostic gold standard, it also presents practical and interpretative limitations:

- Patchy Lesions: Villous atrophy may be focal, and inadequate sampling can result in false negatives.

- Interobserver Variability: Subtle histological alterations may be inconsistently interpreted between pathologists, potentially leading to diagnostic discrepancies.

8.2.3. Impact of a Gluten-Free Diet Before Testing

Initiating a GFD prior to diagnostic evaluation can significantly complicate the diagnostic process:

- Normalization of Serology and Histology: Gluten withdrawal may lead to normalization of antibody titers and mucosal healing, resulting in false-negative results.

- Necessity of a Gluten Challenge: In such cases, a gluten challenge, temporary reintroduction of gluten, is required to re-establish diagnostic sensitivity. This procedure, however, is often symptomatically burdensome and poorly tolerated by patients.

In summary, although diagnostic tools for CeD have become increasingly sophisticated, heterogeneous clinical presentation, technical limitations, and dietary confounders continue to impede early and accurate detection. Optimizing diagnostic algorithms, integrating serology with histology and genetics, and ensuring pre-test dietary compliance remain key to improving diagnostic precision.

8.3. Limitations and Positioning with the Existing Literature

This review has several limitations inherent to its narrative, non-systematic design. Although the literature search was structured, it did not follow formal systematic review protocols, which introduces the possibility of selection bias and incomplete coverage of the available evidence. Furthermore, the review primarily emphasizes adult diagnostic pathways, including the 2025 ESsCD adult guidelines, with comparatively limited discussion of pediatric criteria. Some topics, such as evolving endoscopic technologies and experimental biomarkers, rely on early-phase data that may be susceptible to publication bias, with positive findings more likely to be reported. These factors should be considered when interpreting the conclusions of this review.

This review extends prior syntheses on gluten-related disorders by incorporating several important developments that have emerged since the publication of earlier reviews (2021–2024). Notably, we integrate the 2025 ESsCD updated guidelines, which refine indications for the adult no-biopsy pathway, emphasize age- and risk-based stratification, and clarify the role of serology and HLA typing in diagnostic decision-making. In addition, this review highlights recent advances in immunophenotyping, particularly the diagnostic utility of γδ IELs, which have gained prominence as an adjunctive biomarker in challenging cases.

Furthermore, we provide an updated appraisal of novel imaging modalities, including video capsule endoscopy, confocal laser endomicroscopy, and AI-assisted image interpretation, which are rapidly evolving but not yet widely incorporated into routine practice. Compared with earlier reviews, we also offer a more granular discussion of the CeD–NCGS interface, delineating features that help distinguish these clinically overlapping entities and synthesizing recent insights into the contributions of FODMAPs, fructans, and innate immune activation. Together, these elements position this review as a contemporary and clinically oriented resource for navigating diagnostic complexity.

9. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

CeD is a complex, immune-mediated enteropathy triggered by gluten ingestion in genetically predisposed individuals. Although significant progress has been made in understanding its pathogenesis, clinical spectrum, and diagnostic pathways, early and accurate detection continues to pose challenges due to the disease’s heterogeneous manifestations and serological variability. The adoption of updated diagnostic strategies, as outlined in the 2025 ESsCD guidelines, including the conditional no-biopsy approach in adults and standardized histological assessment protocols, represents an important step toward greater diagnostic precision and patient-centered care.

The cornerstone of treatment remains the lifelong GFD, which effectively promotes mucosal healing, alleviates symptoms, and prevents long-term complications in most patients. However, strict dietary adherence can be challenging and may negatively affect nutritional status, gut microbiota balance, and quality of life. Consequently, there is an increasing need for multidisciplinary management, integrating gastroenterologists, dietitians, and psychologists to ensure sustained patient support and adherence.

Looking ahead, emerging research directions hold promise for transforming the management of CeD. Novel biomarkers, including salivary and fecal peptide assays, microRNAs, and cytokine panels, may improve non-invasive diagnosis and monitoring. Advances in high-resolution imaging, artificial intelligence (AI)—assisted endoscopic evaluation, and molecular immunophenotyping are expected to enhance diagnostic accuracy, particularly in seronegative or atypical cases.

Emerging non-dietary therapies, including gluten-degrading enzymes, zonulin inhibitors, tight-junction modulators, and selective immunotherapies, are promising but remain predominantly in early- or mid-phase clinical trials, and none has yet demonstrated efficacy sufficient to replace the gluten-free diet, which remains the established standard of care.

In conclusion, the landscape of CeD diagnosis and management is evolving toward precision medicine, with an emphasis on early detection, personalized treatment, and improved patient outcomes. Continued interdisciplinary collaboration and translational research will be essential to fully realize these advances and to provide patients with safer, more effective, and less restrictive therapeutic options.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.A.I., A.E.C. and G.I.I.; methodology, A.E.C., G.I.I., I.-A.B., V.B., A.N. and A.B.; software, A.E.C., G.I.I., I.-A.B., V.B., A.N. and A.B.; validation, G.G. and C.C.D.; formal analysis, L.-C.T., N.I.A. and G.G.; investigation, A.E.C., G.I.I., I.-A.B., V.B., A.N. and A.B.; resources, V.A.I., V.B., A.N. and G.G.; data curation, A.E.C., G.I.I., I.-A.B., L.-C.T., N.I.A. and A.B.; writing—original draft preparation, V.A.I., G.G., A.E.C. and G.I.I.; writing—review and editing, C.C.D.; visualization, C.C.D.; supervision, C.C.D.; project administration, V.A.I. and C.C.D.; funding acquisition, V.A.I. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| AGA | Anti-Gliadin Antibodies |

| AMA | Anti-Mitochondrial Antibody |

| ANA | Anti-Nuclear Antibody |

| ATI | Amylase–Trypsin Inhibitors |

| CLE | Confocal Laser Endomicroscopy |

| CeD | Celiac Disease |

| CD | Crohn’s Disease (note: ensure consistent use to avoid confusion with CeD) |

| CRP | C-Reactive Protein |

| CT | Computed Tomography |

| CVID | Common Variable Immunodeficiency |

| DGP | Deamidated Gliadin Peptide |

| EATL | Enteropathy-Associated T-cell Lymphoma |

| ECG | Electrocardiogram |

| ED | Eating Disorder |

| EMA | Endomysial Antibody |

| ESsCD | European Society for the Study of Coeliac Disease |

| ESR | Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate |

| FODMAP | Fermentable Oligo-, Di-, Monosaccharides and Polyols |

| GFD | Gluten-Free Diet |

| GI | Gastrointestinal |

| HLA | Human Leukocyte Antigen |

| HLA-DQ2/DQ8 | Human Leukocyte Antigen DQ2/DQ8 |

| IBD | Inflammatory Bowel Disease |

| IBS | Irritable Bowel Syndrome |

| IEC | Intestinal Epithelial Cell |

| IEL | Intraepithelial Lymphocyte |

| IF | Immunofluorescence |

| IHC | Immunohistochemistry |

| IL | Interleukin |

| LC-MS | Liquid Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry |

| MALT | Mucosa-Associated Lymphoid Tissue |

| NCGS | Non-Celiac Gluten Sensitivity |

| NSAIDs | Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs |

| PCR | Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| PET | Positron Emission Tomography |

| QoL | Quality of Life |

| RR | Relative Risk |

| SIBO | Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth |

| tTG-IgA | Tissue Transglutaminase IgA Antibody |

| TG2 | Tissue Transglutaminase |

| ULN | Upper Limit of Normal |

| VCE | Video Capsule Endoscopy |

References

- Daley, S.F.; Haseeb, M. Celiac Disease. StatPearls. 2025. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK441900/ (accessed on 4 July 2025).

- Lebwohl, B.; Rubio-Tapia, A. Epidemiology, Presentation, and Diagnosis of Celiac Disease. Gastroenterology 2021, 160, 63–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, P.; Arora, A.; Strand, T.A.; Leffler, D.A.; Catassi, C.; Green, P.H.; Kelly, C.P.; Ahuja, V.; Makharia, G.K. Global Prevalence of Celiac Disease: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2018, 16, 823–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butt, N.; Shahid, B.; Butt, S.; Channa, M.M.; Reema, S.; Akbar, A. Clinical Spectrum of Celiac Disease among Adult Population: Experience from Largest Tertiary Care Hospital in Karachi, Pakistan. Euroasian J. Hepatogastroenterol. 2024, 14, 24–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, D.W.; Moleski, S.; Jossen, J.; Tye-Din, J.A. Clinical Presentation and Spectrum of Gluten Symptomatology in Celiac Disease. Gastroenterology 2024, 167, 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lungaro, L.; Costanzini, A.; Manza, F.; Caputo, F.; Remelli, F.; Volpato, S.; De Giorgio, R.; Volta, U.; Caio, G. Celiac Disease: A Forty-Year Analysis in an Italian Referral Center. Nutrients 2024, 16, 2292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durazzo, M.; Ferro, A.; Brascugli, I.; Mattivi, S.; Fagoonee, S.; Pellicano, R. Extra-Intestinal Manifestations of Celiac Disease: What Should We Know in 2022? J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Therrien, A.; Kelly, C.P.; Silvester, J.A. Celiac disease: Extraintestinal manifestations and associated conditions. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2021, 54, 8–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurikka, P.; Nurminen, S.; Kivela, L.; Kurppa, K. Extraintestinal Manifestations of Celiac Disease: Early Detection for Better Long-Term Outcomes. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ionescu, V.A.; Gheorghe, G.; Varlas, V.N.; Stanescu, A.M.A.; Diaconu, C.C. Hepatobiliary Impairments in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Diseases: The Current Approach. Gastroenterol. Insights 2023, 14, 13–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sha, X.; Sun, H.; Li, Y.; Wu, J.; Zhang, H.; Yang, R. The prolamins, from structure, property, to the function in encapsulation and delivery of bioactive compounds. Food Hydrocoll. 2024, 149, 109508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koning, F. Pathophysiology of Celiac Disease. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2014, 59, S1–S4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludvigsson, J.F.; Bai, J.C.; Biagi, F.; Card, T.R.; Ciacci, C.; Ciclitira, P.J.; Green, P.H.R.; Hadjivassiliou, M.; Holdoway, A.; van Heel, D.A.; et al. Diagnosis and management of adult coeliac disease: Guidelines from the British Society of Gastroenterology. Gut 2014, 63, 1210–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboulaghras, S.; Piancatelli, D.; Oumhani, K.; Balahbib, A.; Bouyahya, A.; Taghzouti, K. Pathophysiology and immunogenetics of celiac disease. Clin. Chim. Acta 2022, 528, 74–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doyle, J.B.; Silvester, J.; Ludvigsson, J.F.; Lebwohl, B. Advances in the pathophysiology, diagnosis, and management of celiac disease. BMJ 2025, 391, e081353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parzanese, I.; Qehajaj, D.; Patrinicola, F.; Aralica, M.; Chiriva-Internati, M.; Stifter, S.; Elli, L.; Grizzi, F. Celiac disease: From pathophysiology to treatment. World J. Gastrointest. Pathophysiol. 2017, 8, 27–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iversen, R.; Sollid, L.M. The Immunobiology and Pathogenesis of Celiac Disease. Annu. Rev. Pathol. 2023, 18, 47–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catassi, C.; Elli, L. Non-celiac Gluten Sensitivity: The New Frontier of Gluten Related Disorders. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3839–3853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manza, F.; Lungaro, L.; Costanzini, A.; Caputo, F.; Carroccio, A.; Mansueto, P.; Seidita, A.; Raju, S.A.; Volta, U.; De Giorgio, R.; et al. Non-Celiac Gluten/Wheat Sensitivity—State of the Art: A Five-Year Narrative Review. Nutrients 2025, 17, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina-Infante, J.; Carroccio, A. Suspected Nonceliac Gluten Sensitivity Confirmed in Few Patients After Gluten Challenge in Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trials. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020, 43, 159–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabrera-Chávez, F.; Dezar, G.V.A.; Islas-Zamorano, A.P.; Espinoza-Alderete, J.G.; Vergara-Jiménez, M.J.; Magaña-Ordorica, D.; Ontiveros, N. Prevalence of Self-Reported Gluten Sensitivity and Adherence to a Gluten-Free Diet in Argentinian Adult Population. Nutrients 2017, 9, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lionetti, E.; Catassi, C. The Role of Environmental Factors in the Development of Celiac Disease: What Is New? Diseases 2015, 3, 282–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tovoli, F.; Granito, A.; Negrini, G.; Guidetti, E.; Faggiano, C.; Bolondi, L. Long term effects of gluten-free diet in non-celiac wheat sensitivity. Clin Nutr. 2019, 38, 357–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, A.; Suarez, M.G.; Murray, J.A. Nonceliac Gluten and Wheat Sensitivity. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020, 18, 1913–1922.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calabriso, N.; Scoditti, E.; Massaro, M.; Maffia, M.; Chieppa, M.; Laddomada, B.; Carluccio, M.A. Non-Celiac Gluten Sensitivity and Protective Role of Dietary Polyphenols. Nutrients 2022, 14, 2679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ionescu, V.A.; Gheorghe, G.; Georgescu, T.F.; Bacalbasa, N.; Gheorghe, F.; Diaconu, C.C. The Latest Data Concerning the Etiology and Pathogenesis of Irritable Bowel Syndrome. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 5124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sapone, A.; Bai, J.C.; Ciacci, C.; Dolinsek, J.; Green, P.H.R.; Hadjivassiliou, M.; Kaukinen, K.; Rostami, K.; Sanders, D.S.; Schumann, M.; et al. Spectrum of Gluten-Related Disorders: Consensus on New Nomenclature and Classification. BMC Med. 2012, 10, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catassi, C.; Elli, L.; Bonaz, B.; Bouma, G.; Carroccio, A.; Castillejo, G.; Cellier, C.; Cristofori, F.; de Magistris, L.; Dolinsek, J.; et al. Non-Celiac Gluten Sensitivity: The Salerno Experts’ Criteria. Nutrients 2015, 7, 4966–4977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiepatti, A.; Saviolo, J.; Vernero, M.; Borrelli de Andreis, F.; Perfetti, L.; Meriggi, A.; Biagi, F. Pitfalls in the Diagnosis of Coeliac Disease and Gluten-related Disorders. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skodje, G.I.; Sarna, V.K.; Minelle, I.H.; Rolfsen, K.L.; Muir, J.G.; Gibson, P.R.; Veierod, M.B.; Henriksen, C.; Lundin, K.E.A. Fructan, Rather Than Gluten, Induces Symptoms in Patients with Self-Reported Non-Celiac Gluten Sensitivity. Gastroenterology 2021, 160, 2057–2066.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biesiekierski, J.R.; Newnham, E.D.; Irving, P.M.; Barrett, J.S.; Haines, M.; Doecke, J.D.; Shepherd, S.J.; Muir, J.G.; Gibson, P.R. Gluten Causes Gastrointestinal Symptoms in Subjects Without Celiac Disease: A Double-Blind Randomized Placebo-Controlled Trial. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2011, 106, 508–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertin, L.; Zanconato, M.; Crepaldi, M.; Marasco, G.; Cremon, C.; Barbara, G.; Barberio, B.; Zingone, F.; Savarino, E.V. The role of FODMAP diet in IBS. Nutrients 2024, 16, 370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shepherd, S.J.; Lomer, M.C.E.; Gibson, P.R. Short-chain carbohydrates and functional gastrointestinal disorders. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2013, 108, 707–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rej, A.; Avery, A.; Ford, A.C.; Holdoway, A.; Kurien, M.; McKenzie, Y.; Thompson, J.; Trott, N.; Whelan, K.; Williams, M.; et al. Clinical Application of Dietary Therapies in Irritable Bowel Syndrome. J. Gastrointest. Liver Dis. 2018, 27, 307–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aljada, B.; Zohni, A.; El-Matary, W. The Gluten-Free Diet for Celiac Disease and Beyond. Nutrients 2021, 13, 3993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nestares, T.; Martin-Masot, R.; Labella, A.; Aparicio, V.A.; Flor-Alemany, M.; Lopez-Frias, M.; Maldonado, J. Is a Gluten-Free Diet Enough to Maintain Correct Micronutrients Status in Young Patients with Celiac Disease? Nutrients 2020, 12, 844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ionescu, V.A.; Gheorghe, G.; Georgescu, T.F.; Buica, V.; Catanescu, M.S.; Cercel, I.A.; Budeanu, B.; Budan, M.; Bacalbasa, N.; Diaconu, C. Exploring the role of the gut microbiota in colorectal cancer development. Gastrointest. Disord. 2024, 6, 526–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syage, J.; Ramos, A.; Loskutov, V.; Norum, A.; Bledsoe, A.; Choung, R.S.; Dickason, M.; Sealey-Voyksner, J.; Murray, J. Dynamics of Serologic Change to Gluten in Celiac Disease Patients. Nutrients 2023, 15, 5083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Toma, A.; Zingone, F.; Branchi, F.; Schiepatti, A.; Malamut, G.; Canova, C.; Rosato, I.; Ocagli, H.; Trott, N.; Elli, L.; et al. European Society for the Study of Coeliac Disease 2025 Updated Guidelines on the Diagnosis and Management of Coeliac Disease in Adults. Part 1: Diagnostic Approach. United Eur. Gastroenterol. J. 2025, 13, 1855–1886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvester, J.A.; Kurada, S.; Szwajcer, A.; Kelly, C.P.; Leffler, D.A.; Duerksen, D.R. Tests for Serum Transglutaminase and Endomysial Antibodies Do Not Detect Most Patients with Celiac Disease and Persistent Villous Atrophy on Gluten-free Diets: A Meta-analysis. Gastroenterology 2017, 153, 689–701.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermeersch, P.; Geboes, K.; Marien, G.; Hoffman, I.; Hiele, M.; Bossuyt, X. Diagnostic performance of IgG anti-deamidated gliadin peptide antibody assays is comparable to IgA anti-tTG in celiac disease. Clin. Chim. Acta 2010, 411, 931–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoerter, N.A.; Shannahan, S.E.; Suarez, J.; Lewis, S.K.; Green, P.H.R.; Leffler, D.A.; Lebwohl, B. Diagnostic Yield of Isolated Deamidated Gliadin Peptide Antibody Elevation for Celiac Disease. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2017, 62, 1272–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pace, L.A.; Crowe, S.E. Duodenal bulb biopsies remain relevant in the diagnosis of adult celiac disease. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2016, 14, 1589–1592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Masfield-Smith, S.; Savalagi, V.; Rao, N.; Thomson, M.; Cohen, M.C. Duodenal Bulb Histological Analysis Should Be Standard of Care When Evaluating Celiac Disease in Children. Pediatr. Dev. Pathol. 2014, 17, 339–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pena, A.S. What is the best histopathological classification for celiac disease? Does it matter? Gastroenterol. Hepatol. Bed Bench 2015, 8, 239–243. [Google Scholar]

- Enache, I.; Nedelcu, I.C.; Balaban, M.; Balaban, D.V.; Popp, A.; Jinga, M. Diagnostic Challenges in Enteropathies: A Histopathological Review. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 1511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rostami, K.; Aldulaimi, D.; Holmes, G.; Johnson, M.W.; Robert, M.; Srivastava, A.; Flehou, J.F.; Sanders, D.S.; Volta, U.; Derakhshan, M.H.; et al. Microscopic enteritis: Bucharest consensus. Worlds J. Gastroenterol. 2015, 21, 2593–2604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas, M.M.; Neto, R.A.; Sdepanian, V.L. Quantitative histology as a diagnostic tool for celiac disease in children and adolescents. Ann. Diagn. Pathol. 2022, 61, 152031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansson-Knodell, C.L.; Rubio-Tapia, A. Gluten-related Disorders from Bench to Bedside. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2024, 22, 693–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin-Cardona, A.; Carrasco, A.; Arau, B.; Vidal, J.; Tristan, E.; Ferrer, C.; Gonzalez-Puglia, G.; Pallares, N.; Tebe, C.; Farrais, S.; et al. γδ+ T-Cells Is a Useful Biomarker for the Differential Diagnosis between Celiac Disease and Non-Celiac Gluten Sensitivity in Patients under Gluten Free Diet. Nutrients 2024, 16, 2294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruera, C.N.; Guzman, L.; Menendez, L.; Orellano, L.; Bosch, M.C.G.; Catassi, C.; Chirdo, F.G. Typing of HLA susceptibility alleles as complementary tool in diagnosis of controversial cases of pediatric celiac disease. Front. Nutr. 2025, 12, 1500632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Toma, A.; Volta, U.; Auricchio, R.; Castillejo, G.; Sanders, D.S.; Cellier, C.; Mulder, C.J.; Lundin, K.E.A. European Society for the Study of Coeliac Disease (ESsCD) guideline for coeliac disease and other gluten-related disorders. United Eur. Gastroenterol. J. 2019, 7, 583–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, C.C.; Chou, C.K.; Mukundan, A.; Karmakar, R.; Sanbatcha, B.F.; Huang, C.W.; Weng, W.C.; Wang, H.C. Capsule Endoscopy: Current Trends, Technological Advancements, and Future Perspectives in Gastrointestinal Diagnostics. Bioengineering 2025, 12, 613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roseira, J.; Estevinho, M.M.; Gros, B.; Marafini, I.; Solitano, V.; Sousa, P.; Carretero, C.; Zou, W.; Parsa, N.; Charabaty, A.; et al. Advances in Endoscopy in IBD diagnostics and management. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2025, 78, 102055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zammit, S.C.; Sanders, D.S.; Sidhu, R. A comprehensive review on the utility of capsule endoscopy in coeliac disease: From computational analysis to the bedside. Comput. Biol. Med. 2018, 102, 300–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shapiro, M.; Niv, Y. Diagnostic Yield of Video Capsule Endoscopy (VCE) in Celiac Disease (CD): A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2025, 59, 598–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zammit, S.C.; McAlindon, M.E.; Greenblatt, E.; Maker, M.; Siegelman, J.; Leffler, D.A.; Yardibi, O.; Raunig, D.; Brown, T.; Sidhu, R. Quantification of Celiac Disease Severity Using Video Capsule Endoscopy: A Comparison of Human Experts and Machine Learning Algorithms. Curr. Med. Imaging 2023, 19, 1455–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilonis, N.D.; Januszewicz, W.; di Pietro, M. Confocal laser endomicroscopy in gastro-intestinal endoscopy: Technical aspects and clinical applications. Transl. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2022, 7, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, K.; Abou-Taleb, A.; Cohen, M.; Evans, C.; Thomas, S.; Oliver, P.; Taylor, C.; Thomson, M. Role of confocal endomicroscopy in the diagnosis of celiac disease. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2010, 51, 274–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahn, M.; Hagel, A.F.; Hirschmann, S.; Bechthold, C.; Konturek, P.; Neurath, M.; Raithel, M. Modern diagnosis of celiac disease and relevant differential diagnoses in the case of cereal intolerance. Allergo J. Int. 2014, 23, 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascual, V.; Dieli, C.; Lopez-Palacios, N.; Bodas, A.; Medrano, L.M.; Nunez, C. Inflammatory bowel disease and celiac disease: Overlaps and differences. World J. Gastroenterol. 2014, 20, 4846–4856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghoshal, U.C.; Gwee, K.A. Post-infectious IBS, tropical sprue and small intestinal bacterial overgrowth: The missing link. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2017, 14, 435–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, P.; Baloda, V.; Gahlot, G.P.; Singh, A.; Mehta, R.; Vishnubathla, S.; Kapoor, K.; Ahuja, V.; Gupta, S.D.; Makharia, G.K.; et al. Clinical, endoscopic, and histological differentiation between celiac disease and tropical sprue: A systematic review. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019, 34, 74–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remiker, A.; Bolling, K.; Verbsky, J. Common Variable Immunodeficiency. Med. Clin. N. Am. 2024, 108, 107–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yazdani, R.; Habibi, S.; Sharifi, L.; Azizi, G.; Abolhassani, H.; Olbrich, P.; Aghamohammadi, A. Common Variable Immunodeficiency: Epidemiology, Pathogenesis, Clinical Manifestations, Diagnosis, Classification, and Management. J. Allergol. Clin. Immunol. 2020, 30, 14–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, A.; Thite, P.; Hansen, T.; Kendall, B.J.; Sanders, D.S.; Morison, M.; Jones, M.P.; Holtmann, G. Links between celiac disease and small intestinal bacterial overgrowth: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2022, 37, 1844–1852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, S.S.C.; Bhagatwala, J. Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth: Clinical Features and Therapeutic Management. Clin. Trans. Gastroenterol. 2019, 10, e00078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, T.H.; Li, H. Olmesartan and Drug-Induced Enteropathy. Pharm. Ther. 2014, 39, 47–50. [Google Scholar]

- Marietta, E.V.; Cartee, A.; Rishi, A.; Murray, J.A. Drug-induced enteropathy. Dig. Dis. 2015, 33, 215–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto_Sanchez, M.I.; Silvester, J.A.; Lebwohl, B.; Leffler, D.A.; Anderson, R.P.; Therrien, A.; Kelly, C.P.; Verdu, E.F. Society for the Study of Celiac Disease position statement on gaps and opportunities in coeliac disease. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 18, 875–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oxentenko, A.S.; Rubio-Tapia, A. Celiac Disease. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2019, 94, 2556–2571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardenas-Torres, F.I.; Cabrera-Chavez, F.; Figueroa-Salcido, O.G.; Ontiveros, N. Non-Celiac Gluten Sensitivity: An Update. Medicina 2021, 57, 526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda, M.E.; Garcia-Valdes, L.; Espigares-Rodriguez, E.; Leno-Duran, E.; Requena, P. Non-celiac gluten sensitivity: Clinical presentation, etiology and differential diagnosis. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2023, 46, 562–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ierardi, E.; Losurdo, G.; Piscitelli, D.; Giorgio, F.; Amoruso, A.; Iannone, A.; Principi, M.; Di Leo, A. Biological markers for non-celiac gluten sensitivity: A question awaiting for a convincing answer. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. Bed Bench. 2018, 11, 203–208. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Casella, G.; Villanacci, V.; Di Bella, C.; Bassotti, G.; Bold, J.; Rostami, K. Non celiac gluten sensitivity and diagnostic challenges. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. Bed Bench 2018, 11, 197–202. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ravelli, A.; Villanacci, V.; Monfredini, C.; Martinazzi, S.; Grassi, V.; Manenti, S. How patchy is patchy villous atrophy?: Distribution pattern of histological lesions in the duodenum of children with celiac disease. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2010, 105, 2103–2110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirmizi, A.; Kalkan, C.; Yuksel, S.; Gencturk, Z.B.; Savas, B.; Soykan, I.; Cetinkaya, H.; Ensari, A. Discriminant value of IEL counts and distribution pattern through the spectrum of gluten sensitivity: A simple diagnostic approach. Virchows Archiv. 2018, 473, 551–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboulaghras, S.; Piancatelli, D.; Taghzouti, K.; Balahbib, A.; Alshahrani, M.M.; Al Awadh, A.A.; Goh, K.W.; Ming, L.C.; Bouyahya, A.; Oumhani, K. Meta-Analysis and Systematic Review of HLA DQ2/DQ8 in Adults with Celiac Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalski, M.K.; Domzal-Magrowska, D.; Malecka-Wojciesko, E. Evaluation of the Frequency of HLA-DQ2/DQ8 Genes Among Patients with Celiac Disease and Those on a Gluten-Free Diet. Foods 2025, 14, 298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebwohl, B.; Ludvigsson, J.F.; Green, P.H.R. Celiac disease and non-celiac gluten sensitivity. BMJ 2015, 351, h4347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stordal, K.; Kurppa, K. Celiac disease, non-celiac wheat sensitivity, wheat allergy—Clinical and diagnostic aspects. Semin. Immunol. 2025, 77, 101930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serena, G.; D’Avino, P.; Fasano, A. Celiac Disease and Non-celiac Wheat Sensitivity: State of Art of Non-dietary Therapies. Front. Nutr. 2020, 7, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biesiekierski, J.R.; Jonkers, D.; Ciacci, C.; Aziz, I. Non-coeliac gluten sensitivity. Lancet 2025, 406, 2494–2508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aufiero, V.R.; Fasano, A.; Mazzarella, G. Non-Celiac Gluten Sensitivity: How Its Gut Immune Activation and Potential Dietary Management Differ from Celiac Disease. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2018, 62, e1700854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picarelli, A.; Borghini, R.; Di Tola, M.; Marino, M.; Urciuoli, C.; Isonne, C.; Puzzono, M.; Porowska, B.; Rumi, G.; Lonardi, S.; et al. Intestinal, Systemic, and Oral Gluten-related Alterations in Patients with Nonceliac Gluten Sensitivity. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2016, 50, 849–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, P.I.; Aronico, N.; Santacroce, G.; Broglio, G.; Lenti, M.V.; Di Sabatino, A. Nutritional Consequences of Celiac Disease and Gluten-Free Diet. Gastroenterol. Insights 2024, 15, 878–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzola, A.M.; Zammarchi, I.; Valerii, M.C.; Spisni, E.; Saracino, I.M.; Lanzarotto, F.; Ricci, C. Gluten-Free Diet and Other Celiac Disease Therapies: Current Understanding and Emerging Strategies. Nutrients 2024, 16, 1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dore, M.P.; Pes, G.M.; Dettori, I.; Villanacci, V.; Manca, A.; Realdi, G. Clinical and genetic profile of patients with seronegative coeliac disease: The natural history and response to gluten-free diet. BMJ Open Gastroenterol. 2017, 4, e000159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).