Abstract

Background: Varicose veins (VVs) are an overlying manifestation of chronic venous disease, commonly occurring in the lower extremities. While typically linked to primary venous insufficiency, they can occasionally be secondary to systemic disease, e.g., malignancies, by various mechanisms such as tumor compression, hypercoagulability, and paraneoplastic syndromes. Bilateral varicose veins, as a presenting symptom of gastric cancer, are extremely rare and poorly documented. Materials and Methods: A comprehensive literature search was conducted to identify reports and studies linking varicose veins and malignancies, with particular focus on gastric cancer. The search was performed using the PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science databases covering the last 13 years. Results: Literature Review: A review of the literature in the past decade identified publications, mostly case reports, describing associations between varicose-like venous changes and malignancies such as gastric, pancreatic, hepatic, and small-bowel tumors. The predominant mechanisms reported were inferior vena cava obstruction, tumor-related thrombosis, and paraneoplastic migratory superficial thrombophlebitis (Trousseau’s syndrome). Only a few cases involved gastric cancer as the primary site, with venous changes often being the first clinical sign. There is limited experience with gastric cancer that presents alongside bilateral collateral or varicose veins initially. Apart from the various reports having malignancies and varicose veins we also describe the case of a 50-year-old man who had extended history of bilateral lower-limb varicose veins. Severe, unexplained anaemia without obvious bleeding was discovered during examination. A biopsy verified a gastric adenocarcinoma, while upper gastrointestinal endoscopy revealed an ulcerated mass on the stomach’s greater curvature. Peritoneal dissemination was discovered with additional staging. A palliative subtotal gastrectomy was carried out because of the patient’s ongoing anaemia and suspected chronic bleeding caused by the tumour. The venous symptoms preceded any gastrointestinal issues. Conclusions: Although uncommon, malignancy should be considered in the differential diagnosis for atypical or rapidly progressing bilateral varicose veins, especially when accompanied by systemic symptoms or lab results such as unexplained anemia. Increased suspicion may lead to earlier cancer detection in some patients.

1. Introduction

Of the many presentations across the clinical spectrum of chronic venous disease, primary varicose veins (VVs) are the most common; other presentations like venous aneurysms, pelvic vein insufficiency, or secondary varicosities are rarely encountered [1,2,3]. VVs significantly affects the patient’s quality of life, being associated with a huge medical burden, especially once the disease progresses to advanced stages [4]. They are defined as a permanent dilation of the veins, with a consequent inability of the semilunar valves closure, causing tortuosity and blood stagnation. VVs are more common in the lower limbs and can be caused by familiarity, sedentary life, obesity, pregnancy, and prolonged immobility [5].

Gastric cancer (GC) is the fifth most common cancer in the world and the third most common cause of cancer death globally. It is two times more prevalent in men than women, adenocarcinoma being the most common type. Risk factors for this disease include age, obesity, Helicobacter Pylori chronic infection, diet rich in smoked or spicy foods, high salt intake, and diets low in fruit and vegetables [6]. Usually, GC manifests itself with symptoms that comprise early satiety, stomach pain, abdominal discomfort, nausea and vomiting, anorexia, and unexplained weight loss, but symptoms and clinical manifestations can vary based on size, location, mass effect, and paraneoplastic-associated effects of the tumor [7].

While bilateral varicose veins are a common clinical finding and usually benign, their presence as an early or sole manifestation of an underlying malignancy is extremely rare and poorly documented. Hypothetically, venous changes might result from tumor-related compression of abdominal vasculature, hypercoagulability, or paraneoplastic mechanisms [8,9]. However, evidence remains limited.

In this review, we explore the potential vascular manifestations of malignancies with a focus on varicose veins and venous abnormalities. We also present an unusual case of a patient initially evaluated for bilateral varicose veins, whose subsequent workup revealed advanced gastric cancer. Although a direct causal relationship cannot be established, this case highlights the importance of considering broader differential diagnoses in atypical or unexplained vascular presentations.

2. Material and Methods

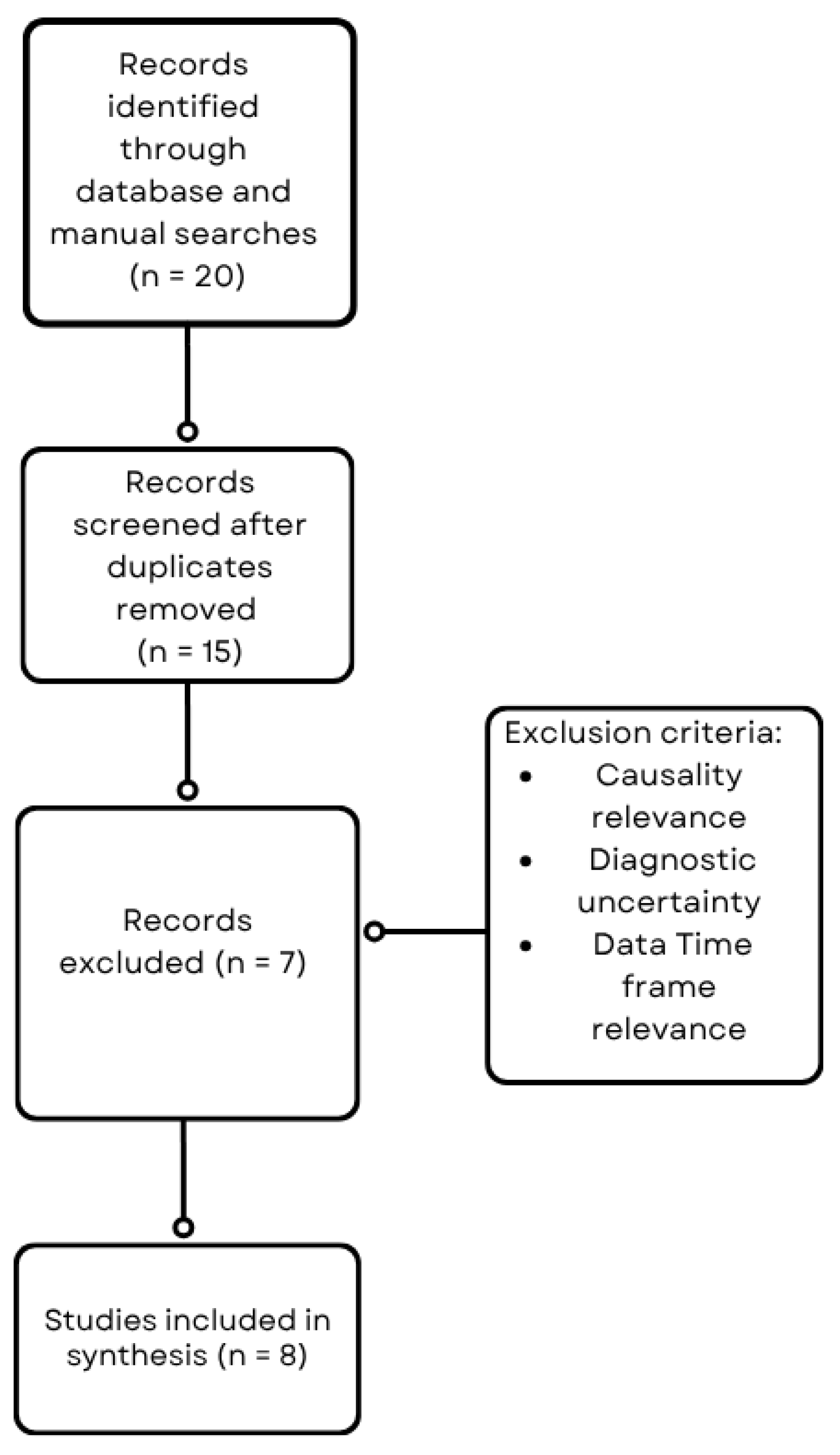

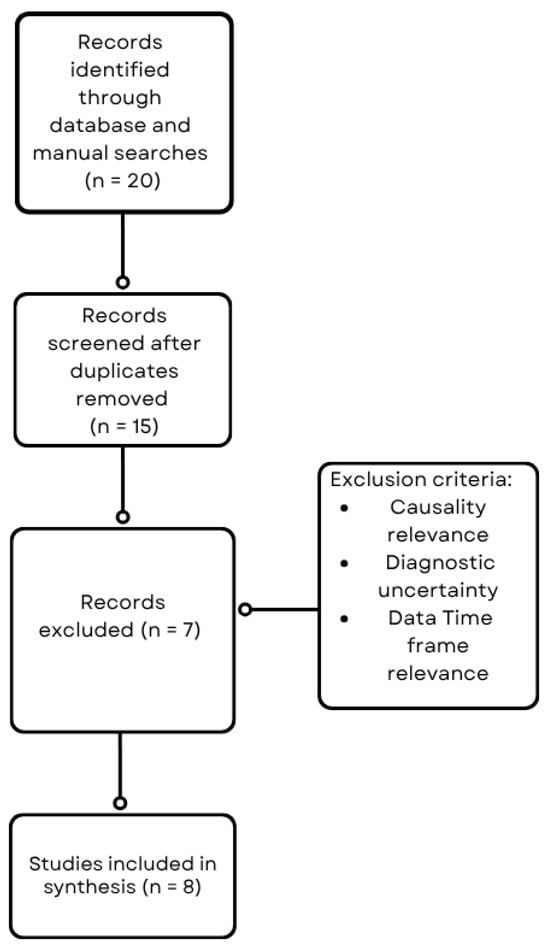

A comprehensive literature search was conducted to identify reports and studies linking varicose veins and malignancies, with particular focus on gastric cancer (Figure 1). The search was performed using the PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science databases covering the last 13 years. Search terms included combinations of keywords and Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) such as “varicose veins,” “venous insufficiency,” “bilateral varicosities,” “gastric cancer,” “malignancy,” “tumor compression,” and “paraneoplastic syndrome.” Boolean operators (AND, OR) were used to refine the search. Articles were screened by title and abstract for relevance, followed by full-text review. Inclusion criteria comprised case reports, case series, observational studies, and reviews reporting on the association of varicose veins or venous abnormalities with malignancy. Studies lacking sufficient clinical or diagnostic details, lack of direct association between venous changes and malignancy and studies outside the defined period were excluded.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the literature search and study selection process.

3. Pathophysiology

Normal Venous Circulation and Pathogenesis of Varicose Veins

Varicose veins are caused by a combination of factors, including incompetent venous valves, increased pressure in the veins, and structural changes in the vein walls. The functioning of the lower extremity venous system depends on healthy valves, an intact calf muscle pump, and a favorable pressure gradient to ensure that blood flows in one direction. When any part of this system fails, it can lead to ambulatory venous hypertension, resulting in chronic venous insufficiency [5,10]. The development of primary varicose veins typically begins with valvular dysfunction, which allows blood to flow backward and pool in the veins. This persistent increase in venous pressure leads to shear stress and inflammation, promoting remodeling of the venous walls [5,11]. Histologically, this process is characterized by the breakdown of elastin, increased collagen deposition, and changes in the phenotype of smooth muscle cells, which together result in the dilation and twisting of the veins [11,12]. Research has also shown that the degradation of the extracellular matrix, elevated activity of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), and the infiltration of leukocytes contribute to the ongoing weakening of the venous walls [11,13]. These molecular changes create a cycle of valvular failure and venous dilation. Additionally, factors such as genetic predisposition, obesity, limited mobility, and hormonal influences can further exacerbate these changes [10,13]. Ultimately, the failure of venous valves and the loss of integrity in the vessel walls lead to the clinical presentation of varicose veins, which are characterized by dilated, twisted superficial veins that are susceptible to blood stasis and can cause discomfort.

4. Mechanisms by Which Malignancies Can Affect Venous Circulation (e.g., Hypercoagulability, Tumor Compression, Paraneoplastic Syndromes)

4.1. Hypercoagulability

One of the most well-recognized mechanisms by which malignancies influence venous circulation is through the induction of a hypercoagulable state. Cancer cells can directly activate the coagulation cascade by expressing procoagulant molecules, such as tissue factor and cancer procoagulant, which initiate thrombin generation and fibrin formation [14]. In addition, tumors release pro-inflammatory cytokines and interact with host blood cells, including platelets, neutrophils, and monocytes, further promoting a prothrombotic environment [15]. This systemic state is often amplified by tumor necrosis, elevated acute-phase reactants, and hemodynamic changes such as blood stasis, especially in patients with advanced or metastatic disease [14,16]. Endothelial dysfunction, triggered by circulating tumor-derived factors or by the mechanical stress of tumor growth, further predisposes to thrombosis [15]. Moreover, cancer therapies—including surgery, chemotherapy, hormone therapy, and central venous catheters—can damage the endothelium or stimulate the release of procoagulant agents, compounding the risk [14,17]. As a result, patients with malignancy are at significantly higher risk of developing venous thromboembolic events, even in the absence of local vascular obstruction. This prothrombotic state may also contribute to atypical venous manifestations, such as superficial thrombophlebitis, varicosities, or chronic venous insufficiency, especially when combined with anatomical or hemodynamic alterations.

4.2. Tumor Compression

Malignancies in the abdomen, pelvis, or mediastinum may interfere with venous circulation by direct mechanical compression of large veins. The growth of a tumor can narrow or block venous lumina, creating high hydrostatic pressure downstream from the obstruction and the development of venous dilation, varicosities, or edema [18]. Within the abdominal cavity, pancreatic, gastric, or retroperitoneal tumors may compress the iliac veins or inferior vena cava (IVC) and cause bilateral lower limb venous congestion [19]. Similarly, hepatic metastases or large gastric neoplasms, particularly those located along the greater curvature or posterior stomach wall, may compress the portal venous system, alter collateral pattern, and potentially result in anomalous varicose vein development [20].

Compression of the IVC typically causes symmetrical swelling of the lower limbs, but long-standing obstruction can lead to superficial venous dilatation from collateralization around the blocked segment. Such collaterals can involve superficial veins of the abdominal wall or lower limbs, resulting in a clinical picture that simulates primary varicose veins but represents secondary varicose veins resulting from obstructed central venous outflow [21].

4.3. Paraneoplastic Syndromes

Paraneoplastic syndromes are systemic paraneoplastic syndromes representing manifestations of malignancy not due to direct invasion or compression by the tumor, but due to bioactive substances secreted by the tumor or by immune mechanisms [22]. On the venous side, certain paraneoplastic events—most significantly Trousseau’s syndrome—are predisposed to recurrent migratory thrombophlebitis and superficial vein inflammation [14]. These are mediated by the release of procoagulant proteins such as tissue factor, cancer procoagulant, and inflammatory cytokines (e.g., interleukin-1, tumor necrosis factor-α) by the tumor, leading to activation of the coagulation process and endothelial damage to the veins [15,23].

Gastric adenocarcinoma is particularly famous for its direct relationship with hypercoagulability and Trousseau’s syndrome [24]. Thrombotic attacks in this setting may involve both superficial and deep venous systems and sometimes present as large, tortuous superficial veins of the lower limbs. Recurrent superficial thrombophlebitis over time can cause irreversible damage to the venous valvulae, dilatation, and varicose vein phenotype [25].

4.4. Varicose Veins and Cancer: Review of the Literature

Literature over 13 years (2009–2022) illustrates an array of venous presentations associated with certain malignancies either before or post-cancer diagnosis. Lower limb varicose veins on both sides and peripheral and gastrointestinal varices have been noted in small-bowel leiomyosarcoma and pancreatic adenocarcinoma, respectively, with particular focus on venous involvement during presentation or during cancer therapy [26,27]. Hepatocellular carcinoma with IVC tumor thrombus has edema of the lower limbs bilaterally and diffuse abdominal and leg collaterals with varicose vein-like appearance, commonly in advanced disease [28]. Gastric adenocarcinoma remarkably occurs twice in this literature as bilateral venous congestion and IVC compression etiology and presentation of superficial collateral veins with a varicosity mimicry at diagnosis [7,29]. Migratory superficial thrombophlebitis (Trousseau’s syndrome) has also been associated with early gastric cancer and usually occurs before the definitive diagnosis and is a significant paraneoplastic sign [30]. Similar thrombotic complications have been reported in patients with occult malignancies like pancreatic, lung, and gastric cancers, and migratory superficial thrombophlebitis has been common to develop before the detection of cancer [31]. Less common but important is vulvar carcinoma with isolated vulvar varicosities mimicking tumor masses in cancer evaluation, emphasizing the need for careful clinical evaluation of atypical venous presentation [32]. Together, these cases remind us that while varicose veins are prevalent in the general population, bilateral, migratory, or atypical venous symptoms—especially in those presenting with risk factors or nonsustained anemia—should prompt consideration of underlying malignancy, most often gastric cancer.

Table 1 summarizes reported cases over a 13-year period that document associations between varicose veins and various malignancies, highlighting clinical features such as venous signs, laterality, timing relative to cancer diagnosis, and specific cancer types, with an emphasis on gastric cancer.

Table 1.

Cases that highlight associations between varicose veins and various malignancies.

4.5. Case Report

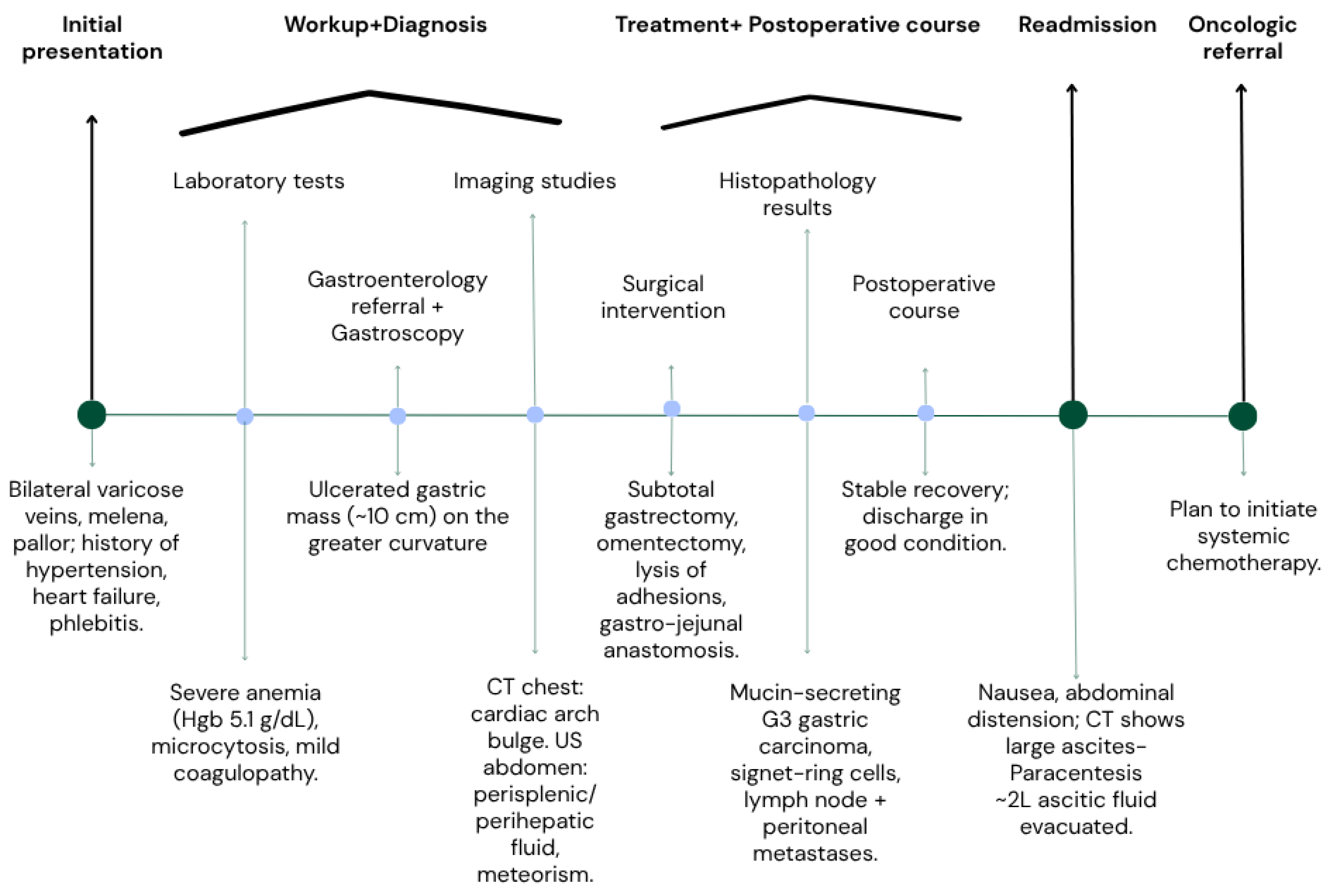

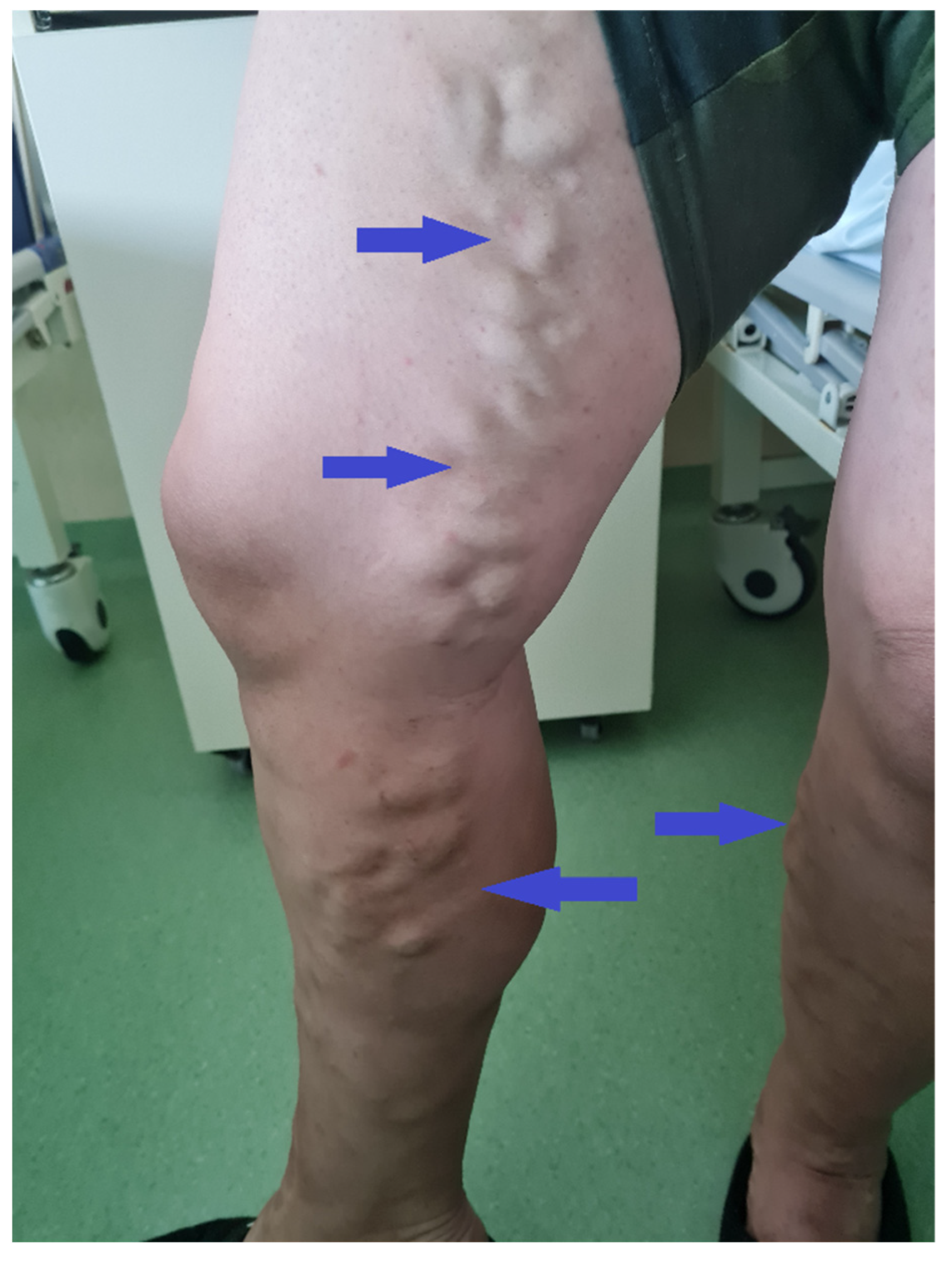

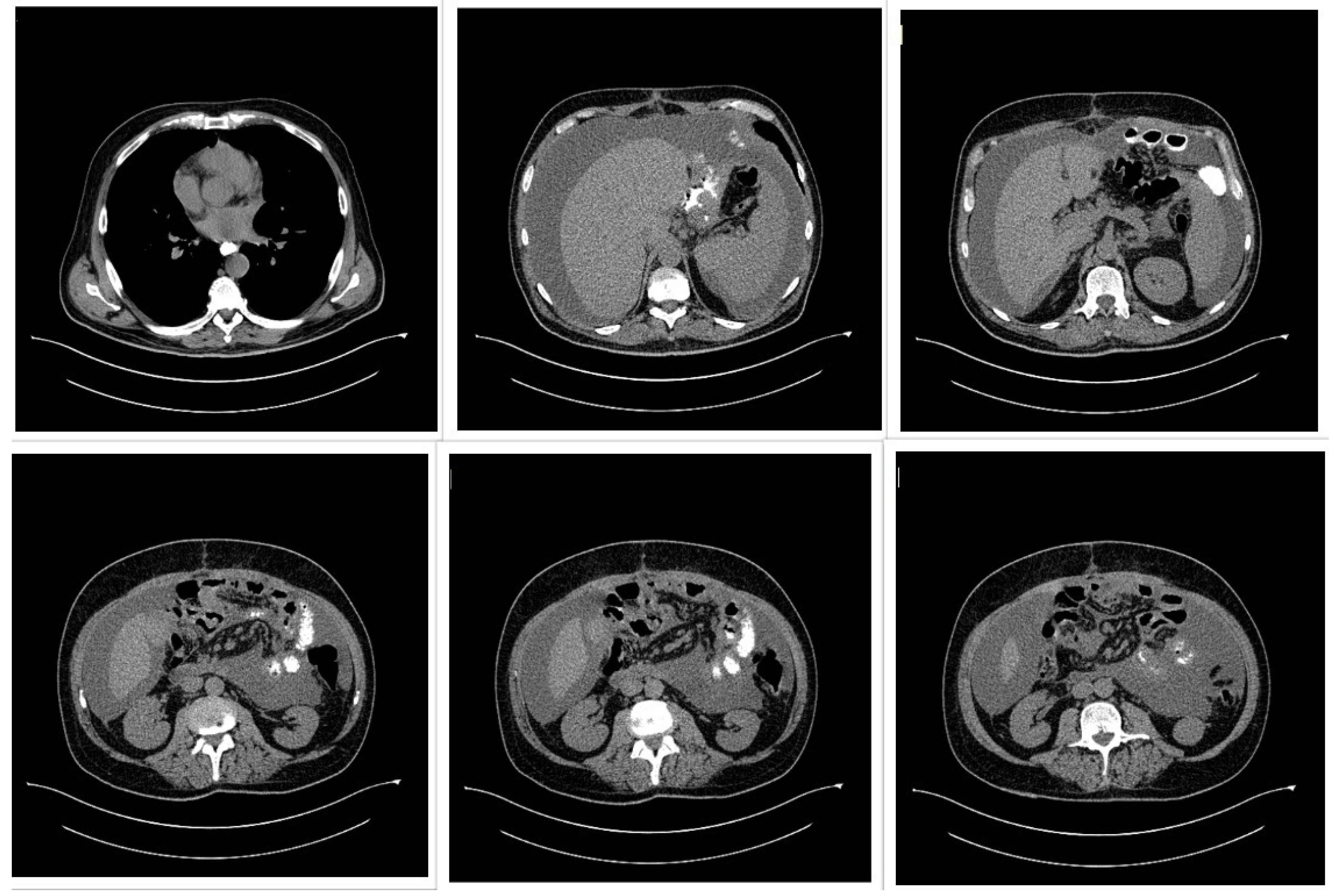

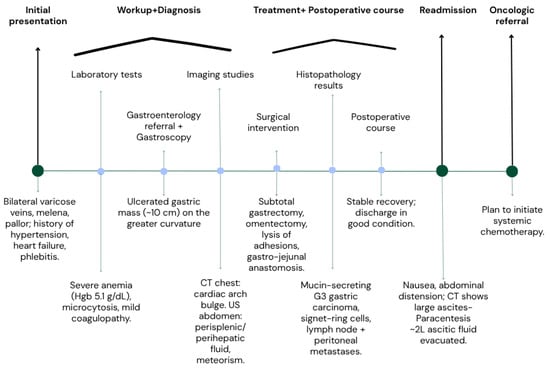

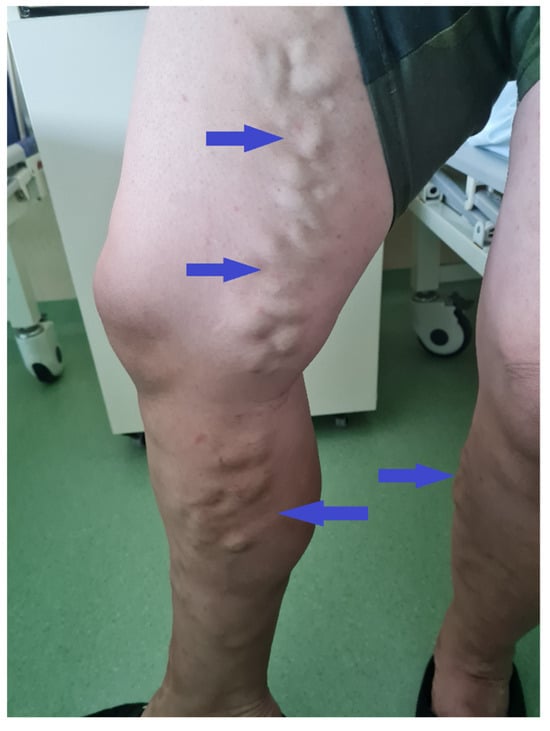

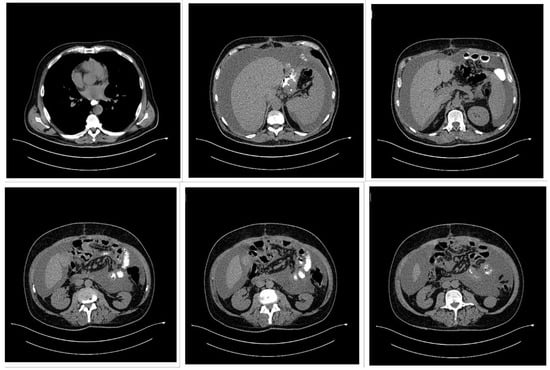

A 50-year-old male patient (Figure 2) with associated pathologies (arterial hypertension, mitral insufficiency, heart failure NYHA grade II, chronic venous insufficiency, and history of superficial phlebitis on the lower limbs) was admitted in the hospital clinically presenting varicose veins, with sinuous and dilated aspect, bilaterally compressible (Figure 3), at the level of the lower limbs, and pale tegument. Paraclinically, the following blood tests were requested: the biochemical profile, coagulation tests and complete blood count, from which the most critical findings were the following parameters: Quick time 73% (WRR. 190–148%), prothrombin 14.3 s (9.4–12.5 s), fibrinogen 400 mg/dL (200–393 mg/dL), hemoglobin 5.1 g/dL (13.6–17.2 g/dL), lymphocytes’ number 0.6 × 101/miL (0.8–3.8 × 101/mi) and lymphocytes percentage 12.2% (20–40%), red blood cells’ number 3.08 × 106/miL (4.5–5.9 × 106/miL), hematocrit 18.7% (39–51%), erythrocyte volume 60.6 fl (80–100 fl) and RDW-CV 17.2% (11.6–14%). Increased attention was paid to the severe anemia (Hb = 5.1 g/dL) detected, after which a gastroenterological consultation was requested, the gastroscopy revealing a proliferative ulcerated process over the greater curvature of the stomach, with an approximate dimension of 10 cm. In the meantime, a thoracic CT and abdominal ultrasound were performed as well (Figure 4): the chest CT revealed a bulge of the right lower cardiac arch and pulmonary hilum increased in volume, without processes of pulmonary condensation. In contrast, the abdominal ultrasound showed marked meteorism and a thin layer of perisplenic and perihepatic fluid. In light of paraclinical and clinical findings, it was then decided to intervene surgically, and during the procedure, a voluminous gastric neoplasm was found, invading the transverse colon, together with peritoneal carcinomatosis, parietal invasion, and neoplastic ascites. Therefore, the surgical team decided to practice subtotal gastrectomy, HoffmeisterFinsterer gastro-jejunal anastomosis, omentectomy, lysis of adhesions and subhepatic drainage. Two specimens were collected: a gastric tumor with epiploon and a second one with the peritoneal carcinomatosis, and eventually the histopathological examination came to the diagnosis of a muco-secreting gastric carcinoma, diffused, with cells in “seal ring”, mildly differentiated G3 with lymph node and peritoneal metastasis. Postoperatively, antibiotic and analgesic treatment, TEP and DVT prophylaxis, toilet and wound dressing were instituted, with favorable evolution and suppression of the drain tube and suture threads. Finally, the patient was discharged with a good general condition, presenting appetite, afebrile, present T.I, considered surgically cured, with the recommendation of an oncological consultation and a second check-up at 30 days apart. Indeed, a month later, the patient was again admitted to the hospital, presenting with nausea, loss of appetite and abdominal distention; therefore, an abdominal and pelvic CT-scan with contrast media was requested as a paraclinical investigation. The scan confirmed a good functioning of the gastroenteric anastomosis performed in the previous operation, but a large perihepatic and perisplenic ascites between intestinal loops and bilateral parieto-colic was found, and for this reason a paracentesis was decided to perform, via which approximately two liters of ascitic fluid was evacuated. The patient was then referred to oncology, in order to initiate the appropriate chemotherapeutic treatment and discharged with improved general conditions.

Figure 2.

Flow chart of events.

Figure 3.

Patient clinical aspect during the admission. In both lower limbs varicose veins are noted, with no clinical sign of superficial thrombosis or phlebitis.

Figure 4.

Thoracic and abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan showing a voluminous gastric tumor compressing the inferior vena cava, associated with para-aortic adenopathy, and without hepatic, peritoneal, or pulmonary metastases.

5. Discussion

Bilateral varicose veins are one of the presentations of chronic venous disease and, in most cases, are due to primary valvular incompetence or secondary causes such as deep vein thrombosis, pregnancy, or standing for long periods [1,2]. Presentation as the first clinical symptom of an occult malignancy is relatively rare. In gastric cancer, specifically, bilateral lower-limb venous dilatation or collateral development as a first presentation has been rarely described in the literature [7,26,29,31]. The present case adds to this brief collection of evidence, illustrating how a vascular presentation, which was initially considered to be an uneventful surgical indication, led to the diagnosis of gastric adenocarcinoma on preoperative workup.

The Table lists published cases over the past decade of varicose veins or varicose-like venous presentations being linked with malignancy, including gastric, pancreatic, hepatic, and gynecologic cancers [26,27,28,29,30,31,32]. Most but not all reports have recorded venous abnormalities occurring in the context of more established disease or following tumor growth, usually due to IVC obstruction or local venous encasement [7,27,28,29,30]. Specifically, a few instances, including this one, showed venous changes before overt systemic manifestations, underlining their utility as an early clinical marker [7,26,29,31,32]. Several mechanisms can be hypothesized to explain the malignancy-abnormal venous correlation. Obstruction of IVC or iliac veins by a tumor can prevent venous return from the lower limbs and cause bilateral edema, superficial venous engorgement, or collateral channel formation mimicking varicose veins [7,27,28,29,30]. Hypercoagulability, a paraneoplastic syndrome well recognized by Trousseau, can cause venous thrombosis and valve damage and secondarily lead to chronic venous changes [31,32]. In addition, paraneoplastic vascular syndromes—albeit rare—can cause endothelial activation and inappropriate venous tone, leading to unusual venous presentation independent of direct obstruction [24,25].

Even though curative resection is usually not an option for advanced stomach cancer when peritoneal spread is present, clinical judgement must occasionally be made on an individual basis. In this particular case, because of the patient’s significant anaemia and the lack of a visible, localized bleeding source, the preoperative MDT chose to proceed with exploratory laparotomy and primary tumor removal. Even though subtotal gastrectomy is usually contraindicated in cases of peritoneal dissemination, the persistent, diffuse bleeding, with no evidence of a certain source, probably caused by several tumour sites, warranted surgical intervention to stop the bleeding. In order to lower surgical risk and postoperative morbidity and also maintaining a higher quality of life after surgery the best course of action was thought to be subtotal resection. This highlights that, in rare presentations such as tumor-related venous manifestations, surgical strategies may diverge from standard algorithms to address immediate complications.

From a clinical perspective, the present case lends support to considering systemic etiologies in atypical or acute-onset bilateral varicose veins, particularly in elderly patients with no long-standing history of venous disease. Although the majority of such presentations will be of benign origin, detection of unusual patterns at an early stage, with limited systemic evaluation, can facilitate timely detection of occult malignancies [26,27,28,29,30,31,32]. The approach is especially relevant in preoperative scenarios, in which a complete workup may reveal unsuspected disease.

Recognition of atypical venous presentations (Table 2) is crucial for the early diagnosis of cancer. While most bilateral varicose veins are caused by benign primary venous insufficiency, some features should arouse clinical suspicion of an underlying systemic cause, e.g., malignancy.

Table 2.

Key “red flags” presentation features.

They are encountered with such red flags as acute presentation in elderly patients, rapid course without apparent precipitating factors, absence of history of chronic venous disease, associated systemic symptoms (e.g., anemia, unexplained weight loss, night sweats), or unusual anatomic distributions such as abdominal wall collaterals [38,39]. Recognition of these patterns allows physicians to move ahead with appropriate investigations, i.e., imaging of the abdomen and pelvis, to exclude venous obstruction secondary to tumor or metastatic disease. In our case and in a few of the literature reports [7,26,29,31], prompt evaluation of a surprising venous result directly led to prompt diagnosis of gastric cancer, emphasizing the life-saving power that heightened awareness can exert.

However, this significant association between varicose veins and stomach cancer should be understood as associative rather than causative. The observed venous abnormalities might not be due to a direct oncologic cause, but rather to secondary phenomena as mechanical compression, hypercoagulability, or paraneoplastic vascular consequences. Nonetheless, these manifestations highlight the necessity of being vigilant when bilateral or atypical varicose veins arise without normal risk factors. It will need more investigation and case association to determine if these correlations are the result of chance or a repeatable pathophysiologic relationship.

6. Limitations of the Study

This case discussion and review have several limitations. Bilateral varicose veins as a presenting symptom of gastric cancer are infrequent, so current literature consists largely of solitary-case series and small series, excluding the strength of evidence and generalizability. The literature review may have lacked unpublished research or research published in foreign languages. In addition, reporting standards heterogeneity among case reports renders synthesis and direct comparison challenging. Finally, causality between malignancy and varicose veins is speculative in the majority of the studies since there are no prospective studies. This highlights the need for larger, systematic studies to clarify further the relationship and clinical significance of venous manifestations in cancer.

7. Conclusions

This article highlights the importance of secondary causes to be considered, particularly in unusual presentations such as acute onset, bilateral distribution without a clear primary venous pathology, or presence with systemic signs and symptoms such as anemia or weight loss. Awareness of such unusual presentations can result in earlier detection of cancer with potentially improved patient outcomes. While the causal link between varicose veins and gastric cancer remains rare, clinicians should remain vigilant, especially when they are presented with venous changes in the absence of classic risk factors. Increased studies and case clustering need to shed light on pathophysiologic mechanisms and generate evidence-based guidelines on when varicose veins should necessitate an oncologic workup.

This reminds us as physicians that despite two pathologies that may appear clinically distant from each other, it is always crucially important to consider a larger and more heterogeneous picture, in this scenario, suspecting the lower limbs VVs as the “tip of the iceberg” of a more severe and insidious pathology.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: A.L.M., F.B. and S.M.; collecting data and resources: A.L.M., F.B., S.M. and L.S.; literature analysis and concluding: A.L.M., A.S., N.R.K. and A.D.; writing—original draft: F.B., C.I.R. and L.M.-B.; reviewing and editing: S.M. and A.S.; project administration: L.S., A.D. and N.R.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

We would like to acknowledge “Victor Babes” University of Medicine and Pharmacy Timisoara, Romania for their support in covering the publication costs for this review article.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethics approval from the Ethical Board of the University of Medicine and Pharmacy “Victor Babes” Timisoara, Romania was obtained based on the Helsinki Declaration (Nr. 17/17.04.2025).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have read the manuscript and have no conflict of interest.

References

- Matei, S.C.; Dumitru, C.Ș.; Radu, D. Measuring the Quality of Life in Patients with Chronic Venous Disease before and Short Term after Surgical Treatment-A Comparison between Different Open Surgical Procedures. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 7171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Matei, S.C.; Matei, M.; Anghel, F.M.; Olariu, A.; Olariu, S. Great saphenous vein giant aneurysm. Acta Phlebol. 2022, 23, 87–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matei, S.C.; Dumitru, C.Ș.; Oprițoiu, A.I.; Marian, L.; Murariu, M.S.; Olariu, S. Female Gonadal Venous Insufficiency in a Clinical Presentation Which Suggested an Acute Abdomen-A Case Report and Literature Review. Medicina 2023, 59, 884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Petrascu, F.-M.; Matei, S.-C.; Margan, M.-M.; Ungureanu, A.-M.; Olteanu, G.-E.; Murariu, M.-S.; Olariu, S.; Marian, C. The Impact of Inflammatory Markers and Obesity in Chronic Venous Disease. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 2524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antani, M.R.; Dattilo, J.B. Varicose Veins. In StatPearls [Internet]; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470194/ (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- Smyth, E.C.; Nilsson, M.; Grabsch, H.I.; van Grieken, N.C.; Lordick, F. Gastric cancer. Lancet 2020, 396, 635–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, S.A. The inferior vena cava (IVC) syndrome as the initial manifestation of newly diagnosed gastric adenocarcinoma: A case report. J. Med. Case Rep. 2015, 9, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Palladino, E.; Nsenda, J.; Siboni, R.; Lechner, C. A giant mesenteric desmoid tumor revealed by acute pulmonary embolism due to compression of the inferior vena cava. Am. J. Case Rep. 2014, 15, 374–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonin, A.H.; Mazer, M.J.; Powers, T.A. Obstruction of the inferior vena cava: A multiple-modality demonstration of causes, manifestations, and collateral pathways. Radiographics 1992, 12, 309–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meissner, M.H. Lower extremity venous anatomy. Semin. Interv. Radiol. 2005, 22, 147–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lattimer, C.R.; Azzam, M.; Kalodiki, E. Chronic venous disease: The relationship between lower limb venous biomechanics and disease progression. J. Vasc. Surg. Venous Lymphat. Disord. 2017, 5, 605–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raffetto, J.D.; Khalil, R.A. Mechanisms of varicose vein formation: Valve dysfunction and wall dilation. Phlebology 2008, 23, 85–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornu-Thenard, A.; Boivin, P.; Baud, J.M.; De Vincenzi, I.; Carpentier, P.H. Importance of the familial factor in varicose disease. J. Dermatol. Surg. Oncol. 1994, 20, 318–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varki, A. Trousseau’s syndrome: Multiple definitions and multiple mechanisms. Blood 2007, 110, 1723–1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caine, G.J.; Stonelake, P.S.; Lip, G.Y.H.; Kehoe, S.T. The hypercoagulable state of malignancy: Pathogenesis and current debate. Neoplasia 2002, 4, 465–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khorana, A.A.; Francis, C.W.; Culakova, E.; Kuderer, N.M.; Lyman, G.H. Frequency, risk factors, and trends for venous thromboembolism among hospitalized cancer patients. Cancer 2007, 110, 2339–2346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falanga, A.; Marchetti, M. Thrombosis in cancer: Pathogenesis and treatment. Thromb. Res. 2018, 164, S123–S127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kesieme, E.; Kesieme, C.; Jebbin, N.; Irekpita, E.; Dongo, A. Deep vein thrombosis: A clinical review. J. Blood Med. 2011, 2, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrensia, S.; Khan, Y.S. Inferior Vena Cava Syndrome. In StatPearls [Internet]; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK560885/ (accessed on 20 May 2023).

- Sakai, T.; Shirai, Y.; Wakai, T.; Nomura, T.; Hatakeyama, K. Portal vein obstruction secondary to gastric carcinoma. J. Gastroenterol. 2002, 37, 734–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, L.D.; Detterbeck, F.C.; Yahalom, J. Superior vena cava syndrome with malignant causes. N. Engl. J. Med. 2007, 356, 1862–1869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelosof, L.C.; Gerber, D.E. Paraneoplastic syndromes: An approach to diagnosis and treatment. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2010, 85, 838–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rickles, F.R.; Levine, M.N. Epidemiology of thrombosis in cancer. Acta Haematol. 2001, 106, 6–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sack, G.H., Jr.; Levin, J.; Bell, W.R. Trousseau’s syndrome and other manifestations of chronic disseminated coagulopathy in patients with neoplasms: Clinical, pathophysiologic, and therapeutic features. Medicine 1977, 56, 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falanga, A.; Marchetti, M.; Vignoli, A. Coagulation and cancer: Biological and clinical aspects. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2013, 11, 223–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vignoli, A.; Mazzetti, M.; Innocenti, D.; Morelli, S.; Bussani, R. Small bowel leiomyosarcoma presenting with bilateral varicose veins: A rare presentation. Int. J. Surg. Case Rep. 2022, 93, 106980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitahama, T.; Otsuka, S.; Sugiura, T.; Ashida, R.; Ohgi, K.; Yamada, M.; Uesaka, K. A case of pancreatic head cancer with Trousseau’s syndrome treated with radical resection and anticoagulant therapy. Surg. Case Rep. 2023, 9, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Zhang, R.X.; Dong, B.; Guo, K.; Gao, Z.M.; Wang, L.M. Hepatocellular Carcinoma with Inferior Vena Cava and Right Atrium Thrombus: A Case Report. World J. Clin. Cases 2021, 9, 7893–7900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, B.N.; Andraska, E.A.; Obi, A.T.; Wakefield, T.W. Pathophysiology of varicose veins. J. Vasc. Surg. Venous Lymphat. Disord. 2017, 5, 860–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laghzaoui, O. Tumour Appearance of Vulvar Varicose Veins. BMJ Case Rep. 2016, bcr2016214819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vikram, S.; Jacob, P.; Nair, C.G.; Vaidyanathan, S. Gastric Carcinoma—A Rare Presentation. Indian J. Surg. Oncol. 2010, 1, 346–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Sack, G.H., Jr.; Levin, J.; Bell, W.R. Trousseau’s syndrome and cancer-associated thrombosis: Case series and review of the literature. Blood Rev. 2009, 23, 193–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litzendorf, M.E.; Satiani, B. Superficial Venous Thrombosis: Disease Progression and Evolving Treatment Approaches. Vasc. Health Risk Manag. 2011, 7, 569–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaosombatwattana, U.; Charatcharoenwitthaya, P.; Pausawasdi, N.; Maneerattanaporn, M.; Limsrivilai, J.; Leelakusolvong, S.; Kachintorn, U. Value of Age and Alarm Features for Predicting Upper Gastrointestinal Malignancy in Patients with Dyspepsia: An Endoscopic Database Review of 4664 Patients in Thailand. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e052522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasparis, A.P.; Kim, P.S.; Dean, S.M.; Khilnani, N.M.; Labropoulos, N. Diagnostic Approach to Lower Limb Edema. Phlebology 2020, 35, 650–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouri, S.; Martin, J.P. Iron Deficiency Anaemia and Cancer. J. Cancer Treat. Diagn. 2019, 3, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mota, M.M.D.S.; Bezerra, R.O.F.; Garcia, M.R.T. Practical Approach to Primary Retroperitoneal Masses in Adults. Radiol. Bras. 2018, 51, 391–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pannier, F.; Noppeney, T.; Alm, J.; Stücker, M.; Gerlach, H.E.; Rabe, E.; Reich-Schupke, S.; Stücker, R.; Wittens, C.; Zimny, M. S2k Guidelines: Diagnosis and Treatment of Varicose Veins. Hautarzt 2022, 73 (Suppl. S1), 1–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Flynn, N.; Vaughan, M.; Kelley, K. Diagnosis and Management of Varicose Veins in the Legs: NICE Guideline. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 2014, 64, 314–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).