Abstract

Background: Neurologically impaired children often face severe gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), feeding difficulties, and related challenges, profoundly impacting their quality of life (QoL) and that of their caregivers. Surgery is often necessary to alleviate symptoms in this population, and the success of surgical treatment, along with the achievement of clinical endpoints, must also consider the impact on QoL. The aim of this study is to evaluate the impact of fundoplication surgery on the QoL of both children and caregivers. Methods: All patients treated between 2010 and 2023 at the Pediatric Surgery Department of San Matteo Hospital in Pavia were included in the study. The modified 1996 O’Neill questionnaire was identified as a suitable model for a QoL survey. QoL assessments included caregiver-reported outcomes using validated questionnaires, focusing on physical, psychological, and social domains. Patients with a follow-up period of less than 12 months were excluded. As a secondary outcome, we evaluated the satisfaction of patients treated after 2020 who received integrated care through a multidisciplinary outpatient clinic. Results: Among the 77 patients, 42 were treated between 2010 and 2021. Of these, 16 participated in pre- and post-operative QoL evaluations, showing significant improvements in GERD resolution, feeding ease, and caregiver stress. From 2020, 35 patients benefited from a multidisciplinary approach; 12 underwent robotic fundoplication. Feeding ease scores improved significantly (mean increase from 37.5 to 84.2; p < 0.001), while caregiver stress scores decreased by 35% (p < 0.01). Conclusions: The combination of surgical and multidisciplinary interventions significantly enhances QoL for SNI children and their families. Integrated care models provide a framework for addressing complex needs and should be prioritized in clinical practice.

1. Introduction

Children with severe neurological impairment (SNI) are defined as pediatric patients affected by a heterogeneous group of disorders—such as cerebral palsy, genetic, metabolic, or malformative disorders—primarily due to dysfunction of the central nervous system, which affects higher cerebral functions such as speech, motor skills, and memory [1]. Children with SNI often exhibit feeding issues and a variety of gastrointestinal problems.

The prevalence of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) in these patients ranges from 20% to 90% [2], and it can present with distinct symptoms and complications, including failure to thrive, weight loss, aspiration pneumonia, esophagitis, esophageal strictures, and Barrett’s esophagus [3,4]. The quality of life (QoL) of both children and their parents can be severely impacted due to these complications. In fact, there is an increased frequency of outpatient visits, hospitalizations, and the total amount of time spent caring for the child’s special medical and physical needs [5,6,7].

Surgery is usually considered after unsuccessful pharmacological therapy or to manage specific GERD complications. Among surgical procedures for GERD, Nissen fundoplication (NF), either laparoscopic or robotic, is the most commonly applied [8]. The incidence of GERD recurrence after NF is approximately 16–34% [9]. Other surgical approaches, such as total esophagogastric dissociation (TEGD), are commonly used as a second-line treatment for selected children with SNI or in cases of unsuccessful NF [10,11].

The success of surgery depends on the reduction in GERD symptoms and complications, as well as the minimization of surgical sequelae [12]. It is therefore important to longitudinally assess all surgically treated patients. Follow-up evaluations should rely on objective methods such as pH-multichannel intraluminal impedance monitoring and GERD severity scales.

To date, the impact of surgery on psychosocial factors and QoL in children with SNI and GERD remains unclear. Routine administration of QoL questionnaires during follow-up visits is not performed in many centers. Moreover, the evaluation of QoL in children must also consider the caregivers’ perspective, especially in children with SNI who commonly require continuous nursing and care. A better understanding of these factors can be facilitated by using a multidisciplinary care approach. Although this method is considered superior in many fields [13], there is still a lack of information about its direct impact on QoL, particularly in pediatric patients grappling with neurological impairment.

In this study, we investigated how fundoplication improves QoL in children with SNI and GERD by using a specific questionnaire that covers various aspects for both the patient and caregivers. As a secondary outcome, we evaluated the satisfaction of patients who received integrated care through a multidisciplinary outpatient clinic.

2. Results

A total of 77 patients were identified for the entire period: 42 in group A (treated before 2021) and 35 in group B (after the establishment of the multidisciplinary clinic). Patient characteristics are summarized in Table 1. For the QoL evaluation, out of forty-two patients in the first group, only sixteen decided to answer the questionnaire (seven were deceased, seven refused to participate in the study, eight had incomplete data or were lost to follow-up, and four were unreachable by phone despite several attempts). Among the second group of 35 patients attending the multidisciplinary clinic, all 12 patients who underwent fundoplication were included in the study, and all of them answered the questionnaire. The final cohort consisted of 28 patients, 16 from group A and 12 from group B. The quality-of-life questionnaire overall results showed that 44% reported good QoL for their children, while 56% reported acceptable QoL. Notably, none of the respondents indicated poor QoL. Data from our series are shown in Table S1. For easier consultation, we divided the analysis results according to the four sections of the O’Neill questionnaire.

Table 1.

Descriptive characteristics of all patients (n = 77) managed during the study period, grouped by standard care (Group A) and multidisciplinary clinic (Group B). Out of 42 patients who had undergone fundoplication in group A, only 16 patients answered the O’Neill Survey, while all 12 patients in group B answered and were included in the QoL analysis.

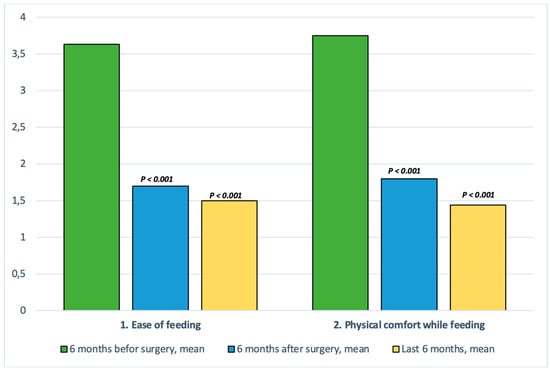

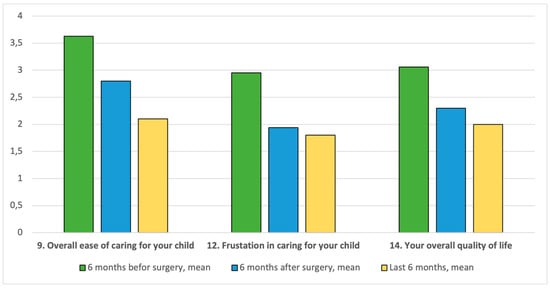

Daily Care and Overall Condition of the Child. Section A of the questionnaire explores parental attitudes toward daily care of the child and the child’s overall condition. Parents reported improvements in ease of feeding and physical comfort while feeding, both 6 months following surgery and in the last 6 months (all p values ≤ 0.001). The mean ease of feeding improved from 3.63 (average to poor) before surgery to 1.69 and 1.50 (good to excellent) 6 months after surgery and in the last 6 months, respectively. A total of 73% of parents reported excellent feeding conditions in the last 6 months. The comfort of the child (p ≤ 0.001), their ability to enjoy life (p = 0.003), and the child’s developmental progress (p ≤ 0.001) showed improvements when comparing the periods before and after surgery and in the last 6 months. Improvements were also reported in the comfort of the child (p ≤ 0.001), their ability to enjoy life (p = 0.003), and the child’s developmental progress (p ≤ 0.001) when comparing the periods before surgery and after surgery, with more improvements reported in the last 6 months (Figure 1 and Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Comparison of the “ease-of-care” domain across the three study timepoints (before surgery, 6 months after surgery, and the last 6 months before the last outpatient clinic visit). A substantial improvement is observed after surgery, which is sustained over time. Statistically significant p-values were based on the Wilcoxon signed-rank test.

Figure 2.

Comparison of the “quality-of-life” domain across the three study timepoints. A marked improvement is observed in caregivers’ perception of the ease of caring for their child, levels of frustration, and overall caregiver quality of life.

Child and Parent’s Quality of Life. Section B of the questionnaire explores parameters related to the child and parent’s overall QoL. These questions directly rate enjoyment, frustration, and their feelings about their own QoL. In our series, parents reported an improvement in the overall ease of caring for their child after surgery, especially in the last 6 months (p ≤ 0.001, p = 0.0001). The mean values for overall enjoyment of the child and quality of time spent together demonstrate slight improvements over time following surgery, but not enough to be considered statistically significant. The mean pre-surgery score for the level of frustration in caring for the child was 2.94 (“average”), but this was significantly improved as early as 6 months after surgery (p = 0.046) and further ameliorated in the last 6 months (p = 0.025). The overall QoL of parents improved not immediately after surgery but over time (p = 0.09).

Child’s Special Medical Needs. Section C of the questionnaire explores parental attitudes toward the special medical needs of their children. Overall, there was less improvement seen here than in sections A and B. The amount of time parents spent caring for their child’s special needs was reduced in the last 6 months (p = 0.028), but there was no significant improvement 6 months after surgery, with results remaining between “average” and “good.” Regarding the frequency of medical visits and hospitalizations, the overall results are positive, showing a significant improvement after the intervention (p < 0.002) and in the last six months (p < 0.0004). However, a distinction must be made between Group A and Group B. Specifically, there are no significant differences in follow-up access for Group A patients after surgery, especially in the last six months (p = 0.09 vs. p = 0.06). Conversely, patients receiving multidisciplinary care benefited from a reduced number of hospital visits, with a significant improvement after the intervention (p < 0.008) and an even greater improvement in the last six months (p < 0.0001).

Parent’s Opinion of Surgery. Section D includes questions regarding the degree of parents’ knowledge about the surgery, as well as their opinion about the results of the surgery. All parents reported being fully informed about what to expect from surgery, and the outcome was much better than expected.

3. Materials and Methods

We conducted a retrospective study on children with SNI under 18 years old who underwent anti-reflux surgery for GERD between 2010 and 2023 at our Pediatric Surgery Center. Data were retrieved from local computer databases. Clinical data included age, date and type of surgical operation, comorbidities, post-operative complications, and outcomes at follow-up. Extracted data were de-identified. Families were contacted by phone to obtain their consent to participate in the study, and written informed consent was obtained from the parents or caregivers via post. In 2020, a multidisciplinary clinic for children with SNI was established within our institution. The clinic comprises three specialists: a neurologist, a clinical dietitian, and a pediatric surgeon. Patients are referred to the clinic by their primary physicians or colleagues from within our institution. Many of the patients attending the multidisciplinary clinic had previously received care from one of the specialists in a single-discipline setting. The clinic operates on a monthly basis, and patients are scheduled for follow-up visits at regular intervals, depending on their individual medical needs. All patients with a follow-up period of less than 12 months were excluded from the study, as were patients who had passed away before the study period or who declined to participate. Informed consent was obtained from all participating families. All data were collected, anonymized, and managed in accordance with ethical standards.

3.1. Survey

The quality-of-life questionnaire was specifically created for this study by drawing inspiration from the O’Neill questionnaire [7], developed to investigate real-life outcomes (i.e., QoL) in children with SNI who have undergone anti-reflux procedures. It is based on parent or caregiver responses and is divided into four sections covering aspects of daily care, complications, comfort and enjoyment of the child, special needs of the child, and the enjoyment of time spent together by the child and parent or caregiver (Figure 1).

The questionnaire consisted of four sections (A–D), each containing questions focusing on a specific area of QoL. In sections A–C, parents were asked to rate their responses on a scale from 1 (excellent) to 5 (terrible). They provided separate answers for three time periods: 6 months before surgery, 6 months after surgery, and the last 6 months. In section D, they again provided answers ranging from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree”, or they could indicate that the question was not applicable or that they did not wish to respond. In this last section, parents did not need to answer for each of the three time periods. The investigator confirmed the patient’s identity, introduced themselves, carefully explained the aim of the call, and obtained consent to participate in the survey.

Because all patients were Italian, a translated Italian version of the questionnaire was used. While the original O’Neill questionnaire is a validated instrument, we did not perform a formal psychometric validation of the Italian version. However, we conducted a forward–backward translation process, and the final version was reviewed by bilingual experts to ensure conceptual and linguistic equivalence. Given the exploratory nature of this study and the use of a previously validated structure, we deemed full psychometric revalidation unnecessary at this stage. This limitation is acknowledged.

To remove possible bias, operating staff were not directly involved in the interviewing process. Phone calls were conducted by fluent native Italian-speaking medical students attending our department. They were judged to be appropriate representatives of the University of Pavia Medical School and capable of making these sensitive and personal phone calls in a professional, caring, and empathetic manner.

3.2. Statistical Analysis

Data derived from sections A–C of the questionnaire were ordinal, with responses ranging from 1 (excellent) to 5 (terrible). For each question, scores were collected for three time periods: 6 months before surgery, 6 months after surgery, and the last 6 months of follow-up. Given the ordinal nature of the data and the small sample size, we applied non-parametric statistical tests.

We used the Friedman test to assess differences across the three repeated time points. For pairwise comparisons (e.g., pre-operative vs. 6 months post-operative; pre-operative vs. long-term), we used the Wilcoxon signed-rank test with Bonferroni correction for multiple testing. Two-tailed p-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

In addition, a subgroup analysis was performed to explore differences in outcomes between patients managed before and after the implementation of the multidisciplinary care team. Where applicable, comparisons between these two cohorts were also analyzed using Wilcoxon or Mann–Whitney U tests for independent groups, based on the distribution and nature of the variables.

4. Discussion

The responsibility of caring for a child with a disability presents formidable challenges and stressors. While a supportive home environment can optimize a child’s potential and alleviate the impact of their impairment, delivering high-quality care for a child with enduring functional limitations can exact tolls on the health and quality of life (QoL) of caregivers [14].

Deterioration in caregiver well-being bears negative repercussions not only on the child but also extends to the familial and societal spheres, culminating in diminished work efficiency, escalated healthcare expenditures for caregivers, and amplified service requirements and expenditures for the child. Within the broader scope of disability discourse, the task of tending to a child with a disability reverberates across multiple domains of a parent’s life, encompassing physical, social, and emotional welfare, conjugal relations, as well as professional and financial standing [14].

The cornerstone of this study is the evaluation of the improvement of QoL in neurologically impaired children after fundoplication surgery, as the success of a treatment cannot be determined solely by clinical endpoints such as disease-free survival. The patient’s well-being must also be considered. In the case of children with SNI, we also need to account for the quality of life of their parents and caregivers because their management represents a significant part of their daily life.

Therefore, it is important to determine whether QoL can be successfully and practically assessed using questionnaires such as the 1996 O’Neill model, which is validated and has been used in other similar studies [2,7,15]. The O’Neill questionnaire was selected due to its broad range of questions exploring various areas of the life of both the child and the parent, while remaining relatively simple to understand, answer, and interpret.

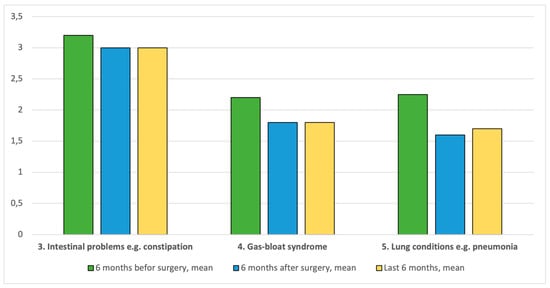

In the first section, our results demonstrate significant improvements in feeding and key indicators for patient QoL, such as the child’s comfort, developmental progress, and enjoyment of life. On the other hand, we did not record any significant improvements in clinical complications such as constipation, gas-bloat syndrome, or pulmonary conditions (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Comparison of the “ease-of-care” domain with a focus on clinical complications across the three study timepoints. No significant improvements were observed in gastrointestinal symptoms such as constipation or gas-bloat syndrome, nor in respiratory conditions. These findings suggest that while caregiving perception improved, clinical complications remained largely unchanged.

The lack of improvement in intestinal problems, such as treating constipation, is consistent with what was reported in a similar study from 2010, as well as in the original O’Neill study [7,15]. The p values were 0.74 and 0.64 for pre- vs. post-surgery and pre-surgery vs. last 6 months, respectively. A possible explanation for this absence of change is that constipation may be due to SNI-induced dysmotility, an abnormality that is not corrected by fundoplication.

Gas-bloat syndrome did not improve, either for pre- vs. post-surgery (p = 0.26) or pre-surgery vs. last 6 months (p = 0.28). This could be explained by the presence of a functional impairment before surgery, causing the gas-bloat syndrome. It is thus necessary to screen all patients to correctly identify any possible functional dysmotility, as fundoplication may possibly worsen this condition by tightening the LES and reducing belching. Functional studies such as gastroduodenal manometry could be helpful to assess gastric emptying and evaluate the need for other procedures (e.g., pyloromyotomy).

A possible explanation for the lack of statistically significant improvements in the incidence of aspiration pneumonia is that the pre-surgery evaluations were already rated as average to good (mean of 2.25). There was a non-significant worsening of the mean values for respiratory complications in the last 6 months compared with 6 months after surgery, possibly explained by the season at the time the survey was performed, soon after winter, a season with higher rates of respiratory infection in children.

In Section B, the results of our study show an encouraging improvement in the child and parent’s overall quality of life. The improved overall ease of caring for the child and the level of concern experienced by parents regarding their ability to care for their child showed some interesting results. There is a significant improvement by 6 months after surgery (p = 0.08), which ameliorates over time, reaching a rating of “good” to “excellent” on average in the last 6 months (p = 0.0001). These results suggest that it takes time for the child and parent to adapt to the post-surgery condition, losing the opportunity to eat food orally, but once they gain more experience, their confidence and ability to care for their child has the potential to improve dramatically, and most of the time previously spent feeding unsafely is redirected to time spent together with the child for physical rehabilitation and family matters, which reduces stress.

The parameter with the lowest mean improvement was the child’s ability to enjoy life, though this may reflect the parent’s experience of their child’s neurological condition, which is unrelated to GERD. Child comfort also decreased slightly between the two time periods, which may be due to a decline in the mean respiratory condition.

Parents were also asked to directly rate their own quality of life. While no significant improvement was observed 6 months after surgery, a statistically significant improvement emerged at long-term follow-up (p = 0.008). This delayed but meaningful improvement suggests that, over time, surgery may help parents feel more confident and less burdened in their caregiving role. The importance of caregiver well-being is critical, as children depend on their parents for all aspects of daily care.

Regarding medical treatment accessibility and improvements in follow-up, the overall results are positive. It is notable that these results were heavily influenced by patients managed by the multidisciplinary group. The vast majority of caregivers felt reassured by the presence of several specialists during the clinic visit and did not feel intimidated by the number of doctors. Most caregivers stated that the clinic had significantly reduced their stress levels regarding their child’s care, and all of them indicated that the clinic had not increased their stress. All subjects reported that the clinic had helped reduce the number of their medical visits.

The literature demonstrates improvements in aspects such as accessibility to care, the coordination of complex cases, reduction in hospital visits, and overall enhancement of care quality. Rosell et al. [16] reported more accurate treatment recommendations. Hall et al. [17] concluded that patients are satisfied with a collaborative care approach. Our study results demonstrated similar findings in terms of improvements in access to medical care, reducing the number of medical appointments, and enhancing patient follow-up care.

It is notable that multidisciplinary care leads to a more tailored therapeutic approach for patients, focusing on nutritional status and the need for surgery. In fact, 75% of patients treated in the outpatient clinic received a gastrostomy for feeding support, of whom only 12 patients (about 50%) also underwent fundoplication. These “fragile patients” deserve care improvements in nutritional support that positively impact morbidity, mortality and survival [18].

Limitations

The main limitation of this study is the small sample size and high drop-out rate in the QoL evaluation, as only 28 patients were ultimately included. This may have contributed to a lack of statistical significance in some domains and introduced a degree of selection bias. It should be noted that this limitation particularly affected the first group of patients, whose caregivers were asked to recall specific aspects of the child’s condition dating back as far as a decade.

The presence of a multidisciplinary care team led to a more precise definition of QoL, both pre-operatively and post-operatively. Notably, patients in Group B who underwent surgery were included in the study. The multidisciplinary setting, along with the shared experience among families, appeared to provide a more holistic framework for addressing the complex needs of these patients.

A specific concern is the potential for recall bias, particularly among caregivers in Group A, who were asked to retrospectively evaluate QoL at time points that were several years in the past. This may have affected the accuracy and reliability of their responses and the consistency of the data collected. Conversely, the higher response rate amongst caregivers in Group B—those engaged in the current multidisciplinary setting—introduces a response bias and self-selection which may limit the generalizability of our findings. Nevertheless, the observed improvements in QoL following fundoplication likely reflect not only better feeding and comfort, but also the benefits of coordinated, ongoing clinical support.

Another limitation can be represented by the use of a translated questionnaire. Although the Italian adaptation was carefully translated and reviewed by bilingual experts, it has not undergone formal psychometric validation. This may affect the reproducibility and generalizability of the questionnaire results.

The primary aim of the study was to explore changes in QoL following fundoplication and to assess the role of multidisciplinary care. Although our cohort included both laparoscopic (n = 16) and robotic (n = 12) procedures, we decided not to analyze differences within surgical techniques. The choice of surgical approach coincided with care settings, as all patients in the multidisciplinary group underwent robotic surgery. This overlap would confound any comparison between techniques.

Finally, because the study lacked a non-operative control group, it is not possible to definitively attribute the observed improvements in QoL solely to surgical intervention. Other factors, such as caregiver adaptation over time or the impact of the multidisciplinary setting may also have contributed to the outcomes. Future prospective studies should consider including non-operative patients and comparisons across different care models.

5. Conclusions

Children with SNI are fragile patients and a vulnerable group with particular susceptibility to GERD development. As seen in our study, fundoplication surgery can improve many aspects of both physical and psychological QoL in children with neurological impairments and GERD, as well as in their parents. Several key determinants of QoL showed marked improvement, not only immediately following surgery but also years later, including feeding, comfort, enjoyment of life, developmental progress, ease of care, and others. Moreover, we underline the importance of continuous refinement and adaptation of care models to meet the multifaceted needs of children with neurological impairments and their caregivers, emphasizing the need to adopt a multidisciplinary care model, in line with the growing body of literature not only in children with neurological impairments but also in chronic diseases.

QoL evaluation should encompass a diverse range of domains and incorporate input from both caregivers and healthcare professionals. This ensures a holistic understanding of the impact of care models on the lives of patients and their families, facilitating the development of targeted interventions and policy recommendations.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/gidisord7020038/s1, Table S1: Data from our series.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.R., T.F., M.B. (Marco Brunero); methodology, A.R., E.C., T.F., G.B.P.; formal analysis, V.M., E.C.; investigation and data curation, R.P.G., L.A., M.B. (Marco Brunero), M.B. (Mirko Bertozzi); writing—original draft preparation, A.R., F.D.L.; writing—review and editing, S.S., G.P., G.R., M.B. (Mirko Bertozzi). All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to it being a retrospective study.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We sincerely thank Francesco Bassanese, Bendikt Boyum, Fabrizio Vatta, Cristiana Riboni, and Gili Raskin for their invaluable contribution in administering the questionnaires to the families. Their dedication and effort were essential in gathering the necessary data for this study, and we deeply appreciate their commitment to improving clinical research and patient care. We also extend our gratitude to all the professionals who make the multidisciplinary clinic for children with neurological disabilities possible. Their expertise, dedication, and collaborative approach play a crucial role in providing comprehensive care and support to these children and their families. This paper is dedicated to the “Blue Roses” of Gornja Bistra, whose lives and smiles continue to live in my memory and inspire my work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| SNI | Severe Neurological Impairment |

| GERD | Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease |

| QoL | Quality of Life |

| NF | Nissen Fundoplication |

| TEGD | Total Esophagogastric Dissociation |

| LES | Lower Esophageal Sphincter |

References

- Blackmer, A.B.; Feinstein, J.A. Management of Sleep Disorders in Children with Neurodevelopmental Disorders: A Review. Pharmacotherapy 2016, 36, 84–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quitadamo, P.; Thapar, N.; Staiano, A.; Borrelli, O. Gastrointestinal and nutritional problems in neurologically impaired children. Eur. J. Paediatr. Neurol. 2016, 20, 810–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez Jimenez, D.; Dıaz Martin, J.J.; Bousono Garcıa, C.; Jiménez Treviño, S. Gastrointestinal disorders in children with cerebral palsy and neurodevelopmental disabilities. An. Pediatr. 2010, 73, 361.e1-6. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, S.; Chen, E.; Syniar, G.; Christoffel, K. Prevalence of symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux during childhood: A pediatric practice-based survey. Pediatric Practice Research Group. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2000, 154, 150–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Neill, J.K.; O’Neill, P.J.; Goth-Owens, T.; Horn, B.; Cobb, L.M. Care-Giver Evaluation of Anti-Gastroesophageal Reflux Procedures in Neurologically Impaired Children: What Is the Real-Life Outcome? J. Pediatr. Surg. 1996, 31, 375–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van der Pol, R.J.; Smits, M.J.; van Wijk, M.P.; Omari, T.I.; Tabbers, M.M.; Benninga, M.A. Efficacy of proton-pump inhibitors in children with gastroesophageal reflux disease: A systematic review. Pediatrics 2011, 127, 925–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ceriati, E.; Marchetti, P.; Caccamo, R.; Adorisio, O.; Rivosecchi, F.; De Peppo, F. Nissen fundoplication and combined procedures to reduce recurrence of gastroesophageal reflux disease in neurologically impaired children. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 11618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lauriti, G.; Lisi, G.; Lelli Chiesa, P.; Zani, A.; Pierro, A. Gastroesophageal reflux in children with neurological impairment: A systematic review and metaanalysis. Pediatr. Surg. Int. 2018, 34, 1139–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esposito, C.; Montupet, P.; Van Der Zee, D.; Settimi, A.; Paye-Jaouen, A.; Centonze, A.; Bax, N.K.M. Long-term outcome of laparoscopic Nissen, Toupet, and Thal antireflux procedures for neurologically normal children with gastroesophageal reflux disease. Surg. Endosc. 2006, 20, 855–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coletta, R.; Aldeiri, B.; Jackson, R.; Morabito, A. Total esophagogastric dissociation (TEGD): Lessons from two decades of experience. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2019, 54, 1214–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mattioli, G.; Wong, M.C.; Angotti, R.; Mazzola, C.; Arrigo, S.; Gandullia, P.; Mancardi, M.M.; Fusi, G.; Messina, M.; Zanaboni, C.; et al. Total oesophago-gastric dissociation in neurologically impaired children: Laparoscopic vs robotic approach. Int. J. Med. Robot. Comput. Assist. Surg. 2019, 16, e2048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mauritz, F.; Conchillo, J.; van Heurn, L.; Siersema, P.; Sloots, C.; Houwen, R.; van der Zee, D.; van Herwaarden-Lindeboom, M. Effects and efficacy of laparoscopic fundoplication in children with GERD: A prospective, multicenter study. Surg. Endosc. 2017, 31, 1101–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raffaele, A.; Ferlini, C.M.; Fusi, G.; Lenti, M.V.; Cereda, E.; Caimmi, S.M.E.; Bertozzi, M.; Riccipetitoni, G. Navigating the transition: A multidisciplinary approach to inflammatory bowel disease in children. Pediatr. Surg. Int. 2024, 40, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Davis, E.; Shelly, A.; Waters, E.; Boyd, R.; Cook, K.; Davern, M. The impact of caring for a child with cerebral palsy: Quality of life for mothers and fathers. Child Care Health Dev. 2010, 36, 63–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaidi, T.; Sudall, C.; Kauffmann, L.; Folaranmi, S.; Khalil, B.; Morabito, A. Physical outcome and quality of life after total esophagogastric dissociation in children with severe neurodisability and gastroesophageal reflux, from the caregiver’s perspective. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2010, 45, 1772–1776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosell, L.; Alexandersson, N.; Hagberg, O.; Nilbert, M. Benefits, barriers and opinions on multidisciplinary team meetings: A survey in Swedish cancer care. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2018, 18, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall, J.; Kaal, K.J.; Lee, J.; Duncan, R.; Tsao, N.; Harrison, M. Patient Satisfaction and Costs of Multidisciplinary Models of Care in Rheumatology: A Review of the Recent Literature. Curr. Rheumatol. Rep. 2018, 20, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pelizzo, G.; Calcaterra, V.; Acierno, C.; Cena, H. Malnutrition and Associated Risk Factors Among Disabled Children. Special Considerations in the Pediatric Surgical “Fragile” Patients. Front. Pediatr. 2019, 7, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).