Abstract

This paper presents the compositional characterisation of obsidian artefacts from the archaeological site of Maddalena di Muccia (Marche, Central Italy). The assemblage, spanning the Early Neolithic to the Copper Age, was chemically and petrographically investigated using two non-destructive X-ray analytical instruments: a wavelength-dispersive X-ray spectrometer and a scanning electron microscope equipped with an energy-dispersive X-ray spectrometer. Geochemical data allow secure attribution of the artefacts to their geological sources, confirming the predominant use of Palmarola obsidian during the Early Neolithic and documenting the continued circulation of obsidian also from other sources (Lipari and Monte Arci) into the Copper Age. Significantly, the Muccia assemblage provides the first evidence in the Adriatic area for the contemporaneous presence of multiple Monte Arci obsidian sub-sources (S.A. and S.C.). This compositional pattern suggests sustained long-term exchange networks involving obsidian, and highlights the role of central Adriatic sites within broader prehistoric interaction systems of the central Mediterranean.

1. Introduction

With a research history spanning more than 50 years [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8], obsidian provenance studies have long contributed substantially to the reconstruction of prehistoric interaction networks across the Mediterranean. Nonetheless, expanding the analytical dataset remains crucial, as each new sample has the potential to reveal previously unrecognised connections and to refine existing interpretative models. The routine application of non-invasive analytical methods offers the opportunity to substantially increase the number of analysable artefacts and to generate more comprehensive and comparable datasets.

In this paper, we present the results of a study of a sample of obsidian artefacts from a key archaeological site in Central Italy, whose strategic mid-peninsular position made it a long-term hinge between the Adriatic and Tyrrhenian regions.

Obsidian provenance characterisation can be addressed using numerous minimally invasive or completely non-destructive techniques such as X-ray fluorescence (XRF) using peak intensity ratios of various elements [9,10], scanning electron microscopy coupled with energy-dispersive spectrometer (SEM-EDS) microanalysis [2,11], electron-probe microanalysis [12] and laser ablation inductively coupled plasma–mass spectrometry [13].

In recent years, the increased use of highly efficient energy-dispersive X-ray detectors has made EDS methods prevalent for identifying obsidian source areas [14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27].

Energy-dispersive XRF instruments that are particularly widespread are: (i) X-ray handguns (handheld portable XRF: HHpXRF); (ii) more complex spectrometers to be mounted on tripods (field-portable X-ray fluorescence: FpXRF); and (iii) small transportable instruments (bench-portable X-ray fluorescence: BpXRF).

However, it is worth bearing in mind that ED analyses are rapid and straightforward and particularly useful for student training [17]. In fact, they are particularly useful for initial sorting of artefacts, but one must not exclude the combination of these inexpensive, non-destructive techniques with other effective analytical methods [20,28,29].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. The Archaeological Context of Maddalena di Muccia

Maddalena di Muccia (Figure 1) is an important stratified site in the Marche region (Central Italy) with an occupational sequence ranging from the Early Neolithic (early 6th millennium BC) to the Roman Imperial period. Following preliminary investigations conducted in the 1960s by D. Lollini, the area was subjected to systematic excavations between 2001 and 2008 by Sapienza University of Rome in collaboration with the Archaeological Superintendency of the Marche [30].

Figure 1.

Central–Eastern Mediterranean obsidian source areas (in black); the red star marks the location of the Maddalena di Muccia archaeological site; the cartographic representation is from Google Earth, with modifications.

The Early Neolithic settlement identified in the 1960s consisted of numerous cavities of varying shapes, sizes, and depths and characterised by the presence of impressed pottery. Two more structures were uncovered in 2001. Among these, SU 114, topographically correlated with the area explored during the earlier campaigns, is an ovoid pit with markedly undercut walls, the morphology of which supports its interpretation as a subterranean storage structure. Three radiocarbon dates were obtained for this structure: 6637 ± 83 BP (5720–5470 BC cal 2σ); 6638 ± 59 BP (5650–5480 BC cal 2σ); 6440 ± 50 BP (5490–5320 BC cal 2σ) [30]. Five obsidian artefacts were recovered from this context and analysed for provenance characterisation (Table 1).

Table 1.

The analysed obsidian artefacts, their contexts of origin, their dating, and their photo (artefact orientation adjusted to accommodate the table; red scale bar is 5 mm). (?) = uncertain attribution.

A later Neolithic phase is attested by two pits and a large storage pit (SU 12), which contained only a single obsidian bladelet that was not selected for analysis due to post-depositional alteration. During the 3rd millennium BC, a Copper Age village developed on the site, marked by multiple episodes of construction, enlargement and internal reorganisation. The earliest phase comprises a massive curvilinear palisade delimiting the initial habitation nucleus. After roughly two centuries, following a reconfiguration of the settlement layout, five large apsidal dwellings measuring approximately 10 × 7 m were built. A final phase of occupation is represented by several smaller, irregularly shaped structures with variable orientations. Associated features include pits, postholes, enclosures and additional palisades. A robust series of 15 radiocarbon dates constrains the Copper Age occupation to approximately 2900–2200 BC, although none is directly linked to the structures containing the analysed obsidian artefacts [30]. The architectural scale of the settlement and the diachronic reorganisation of its internal layout indicate the long-term establishment of a demographically substantial community. The site’s strategic position at the intersection of two principal trans-Apennine routes supports the hypothesis of a settlement likely intended to monitor and control movement along a major communication corridor linking the central Apennines with the Adriatic coastal zone.

All eight obsidian artefacts recovered from the Copper Age levels were selected for analysis (Table 1). These consist of six bladelets, two of which display use–retouch, together with a retouched flake (a denticulate). The artefact MAD10b exhibits a double patina, suggesting it may have been reworked from a piece used in an earlier period.

The obsidian artefacts derive from isolated postholes located among the Copper Age huts (MAD9, MAD5), the foundation trench of Hut B (MAD7), pits (MAD8, MAD6), layers covering Palisade B, a structure belonging to the earliest phase of the village (SU 1 in R32: MAD10a and 10b) and a concentration of archaeological materials in R31 (MAD11).

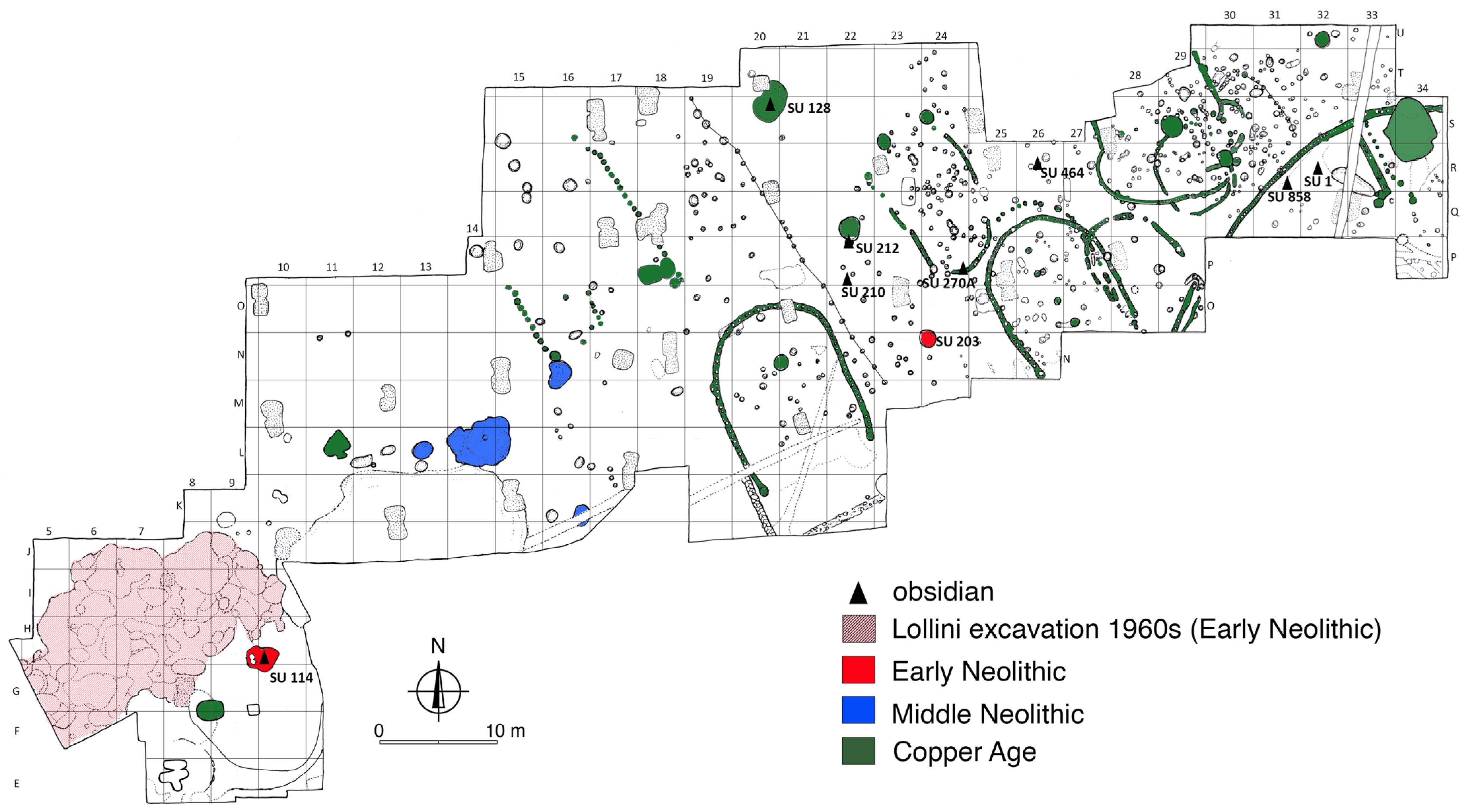

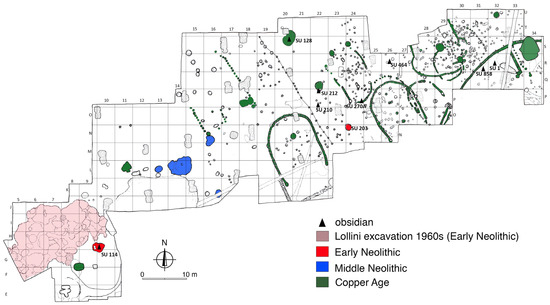

As shown in the map (Figure 2), the distribution of obsidian items is mainly in the eastern portion of the Copper Age settlement, which is also the area characterised by a dense palimpsest of structures spanning all three phases of the village. Consequently, it is not always possible to determine with certainty their precise attribution to a specific Copper Age phase. Moreover, samples MAD10a and MAD10b derive from findspots where chert cores and bladelets, attributable on technological grounds to the Early Neolithic, were recovered. The map also indicates a pit (SU 203) located in this part of the site which contained exclusively Early Neolithic material. Taken together, these observations suggest that in this area structures dating to the Early Neolithic occupation phase may have been intercepted during the construction of the Copper Age village, resulting in the admixture of archaeological materials. However, the obsidian artefacts recovered from features securely attributable to the Copper Age, namely MAD5, MAD7, MAD8, MAD9, are not associated with earlier materials. Their stratigraphic context therefore supports their attribution to the Copper Age.

Figure 2.

Plan of the Maddalena di Muccia site indicating the findspots of the analysed obsidian artefacts.

2.2. Analytical Background

Over the last 40 years, the Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences of the Aldo Moro University of Bari (Italy) has developed two completely non-destructive analytical procedures useful for obsidian petroarchaeometric characterisation: (i) microanalysis of glass and microphenocrysts of the archaeological samples [2,11]; (ii) measurement of trace element X-ray fluorescence emission from the entire obsidian sample [31].

Since the 1990s, approximately 700 obsidian samples have been characterised, most of which were found in Neolithic sites in Central and Southern Italy. In recent years, the characterisation of obsidian has been extended to Neolithic sites in the Middle East [32].

2.3. WD-XRF and SEM-EDS Protocol

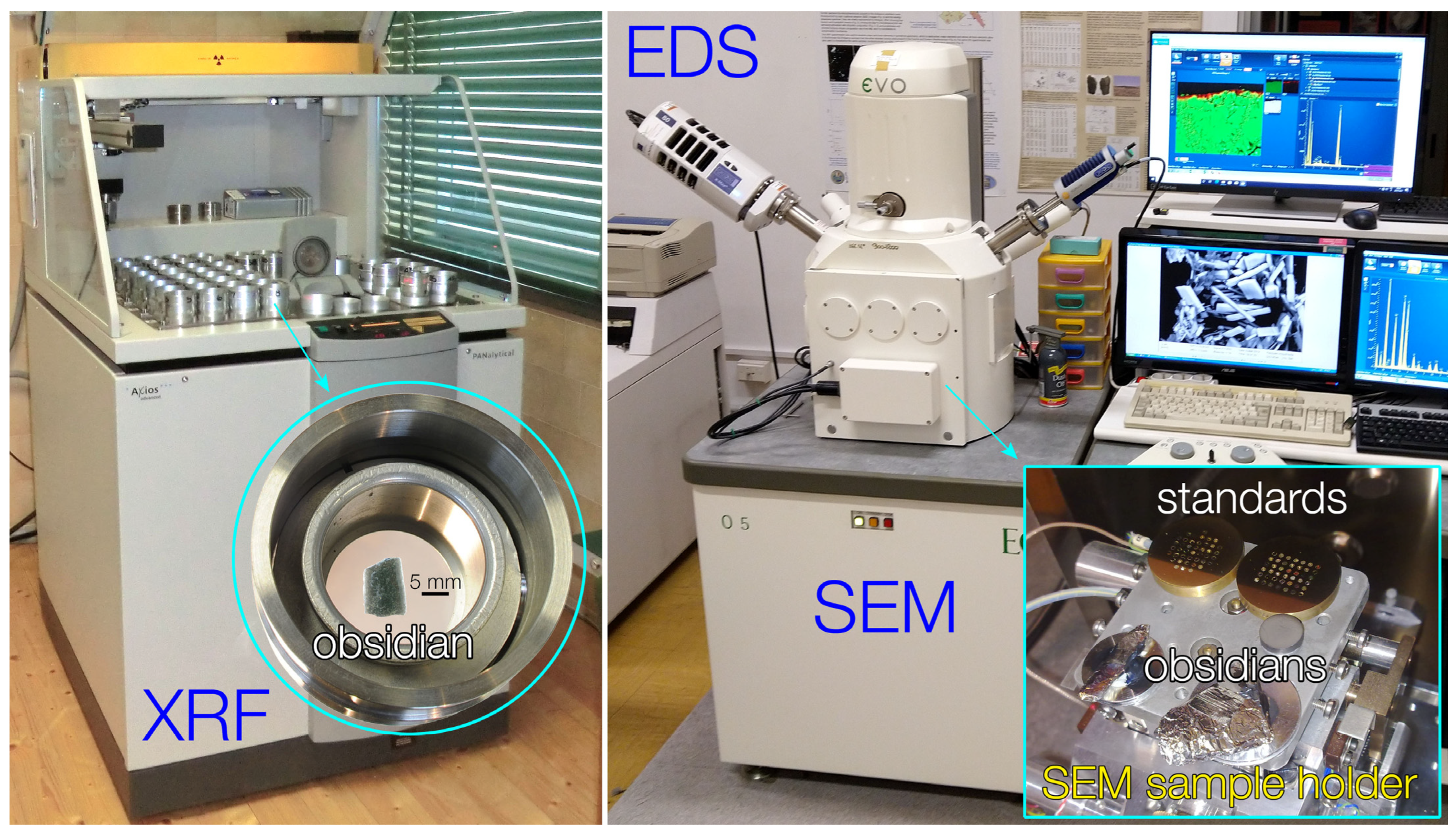

Petroarchaeometric characterisation of the obsidian artefacts was performed using a wavelength-dispersive X-ray spectrometer (WD-XRF) and also a scanning electron microscope coupled with an energy-dispersive X-ray spectrometer (SEM-EDS).

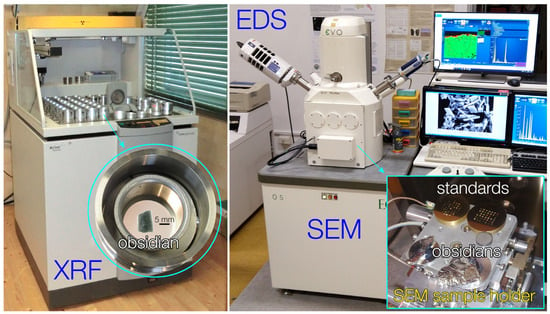

The WD-XRF equipment used for the X-ray analyses is a PANalytical spectrometer (AXIOS Advanced model of PANalytical B.V., Lelyweg 1, 7602 EA Almelo, The Netherlands) equipped with a 4 kW Rh super-sharp end-window X-ray tube operating at 60 kV and 66 mA. A scintillator detector collected the Rb, Sr, Y, Zr and Nb X-ray emission lines, dispersed by a LiF 220 crystal. The obsidian samples were washed by immersing them in a glass beaker containing distilled water, which was then placed in an ultrasonic cleaning tank for about 5 min; the samples were then gently placed on a thin Mylar film that sealed the bottom of the spectrometer sample holder (Figure 3). The Rb, Sr, Y, Zr and Nb X-ray emission lines were measured according to the procedure of [31] and [33,34], particularly taking into account that X-rays must be measured as net intensities, that is, purified from the contribution of the background and from inter-elemental interferences.

Figure 3.

On the left, the X-ray fluorescence (XRF) spectrometer with detail of the sample holder (in the light blue circle) in which the obsidian specimen seems to be suspended in the air (see text for explanation); on the right, the scanning electron microscope (SEM) equipped with an energy-dispersive spectrometer (EDS) and a detail of the sample holder (in the light blue rectangle) on which are mounted the obsidian samples and the reference standards.

SEM investigations were performed with a LEO model EVO50XVP (Zeiss, Cambridge, Cambridgeshire, UK) coupled with an energy-dispersive spectrometer (EDS) from Oxford Instruments (High Wycombe, Buckinghamshire, UK), fitted with a model X-max (80 mm2) silicon drift detector (Figure 3). SEM operating conditions included a 15 kV accelerating potential, a 300 pA probe current, an average count rate of approximately 20,000 cps across the whole spectrum, a 50 s counting time and an 8.5 mm working distance. X-ray intensities were converted into oxide concentration values using the XPP correction procedure, developed by [35,36]. Analytical data were verified using numerous reference standards from Micro-Analysis Consultants Ltd. (Ives, Cambridgeshire, UK).

Before undertaking SEM analyses, the obsidian samples were washed by immersing them in acetone in a glass beaker, which was then placed in an ultrasonic cleaning tank for about 10 min [32].

A flat part of the specimen was chosen for SEM analysis: The remaining parts of the sample were protected by covering them with a thin layer of aluminium foil (the type commonly used for cooking) to protect their more porous or fragile parts [37].

The samples were then fixed onto an aluminium stub using plasticine, to expose one of their flat surfaces to the SEM electron. The specimen was then sputtered with a 30 nm thick carbon film using a thermal evaporator (Edwards, model Auto 306, Irvine, CA, USA) to make its surface conductive; a colloidal graphite drop closed the electrical bridge between the carbon-coated surface of the obsidian and the metal stubs [32]. After SEM investigations, the carbon sputtered on the obsidian surfaces was removed by wiping the specimens with a soft cloth wetted with acetone [32,38].

3. Results

Before discussing the results, it is worth briefly describing the procedure used at the University of Bari Aldo Moro, which allows very accurate analytical data to be obtained with a completely non-destructive technique useful for identifying the obsidian source areas.

An initial characterisation is performed using WD-XRF, which allows the sample to be characterised very quickly, in 30 min [31], without having to treat the sample in any way other than washing it in a beaker containing distilled water. In this way, the glass and microphenocrysts are analysed, and the results are comparable only with laboratories that have used the same technique to measure the X-ray intensities of trace elements such as Rb, Sr, Y, Zr, and Nb.

If the results obtained leave room for doubt, further analyses are carried out using SEM-EDS, which allows analysis of both the major elements of the glass, if it is unaltered, and the microphenocrysts [2,11,32]. The analysis of microphenocrysts certifies the datum because it is not affected by glass alteration phenomena: The artefacts are normally subjected to alteration processes after burial, due to water circulating within sediments [38]. These alteration processes can affect the mobility of alkaline elements, above all Na, and promote the formation of thin carbonate film incrustations (e.g., Table 1, photo of samples MAD01-MAD03b) [[31,38] and the references therein], sometimes even enlarging the uranium-238 fission tracks [32]. The obsidian surface alteration can in some way interfere with WD-XRF analysis, even making it impossible to analyse the glass by SEM-EDS.

The precision and accuracy of analytical data were extensively discussed for the first time in 1999 [2] and in other successive papers [11,31,32].

All obsidian samples from the Maddalena di Muccia site were previously characterised using WD-XRF analysis, by measuring the net intensities of some trace elements, namely Rb, Sr, Y, Zr and Nb [31] (Table 2).

Table 2.

X-ray emission and characterising ratio of some contiguous trace elements of obsidian samples from Maddalena di Muccia. The X-ray intensity values, expressed as counts per second, are background- and interference-free.

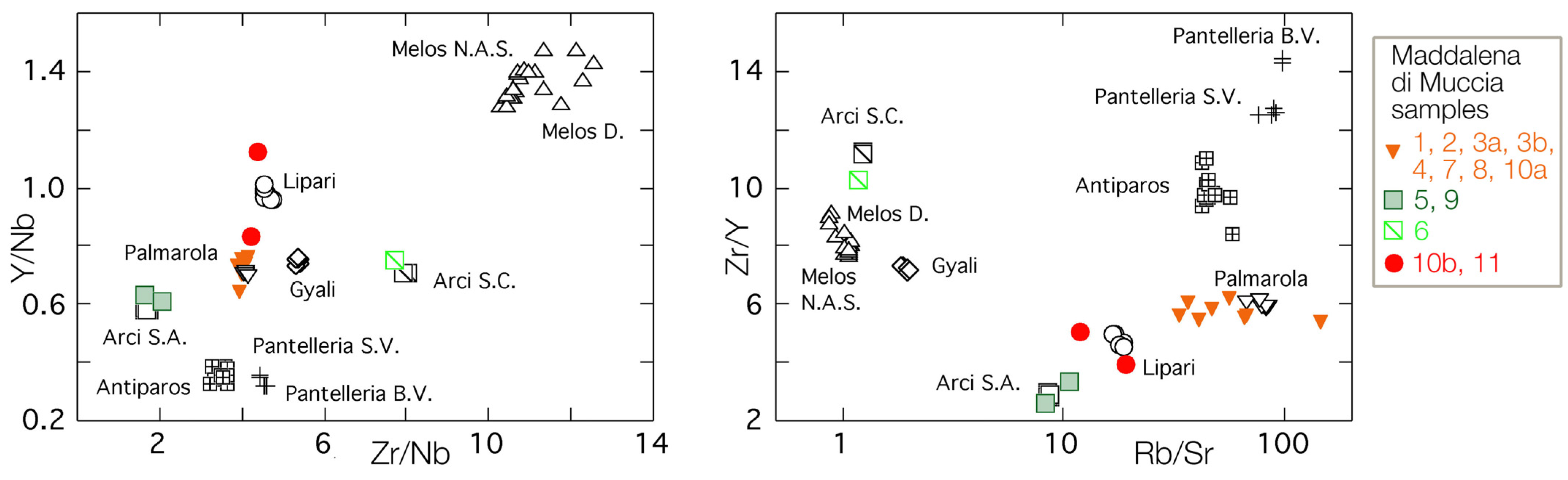

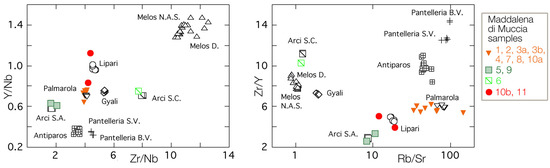

The source-area characterisation of the Maddalena di Muccia obsidian samples reveals three geological volcanic outcrops: Lipari, Palmarola, and Monte Arci (Figure 4), with the latter having two sub-sources, (i) Perdas Urias (S.C.) and (ii) Conca Cannas, Canale Perdera, and Riu Solacera (S.A.).

Figure 4.

WD-XRF data plots of obsidian from the Maddalena di Muccia site compared with the data from other source areas in the Mediterranean (data from [2,39]); sub-source outcrops: Monte Arci, S.C. = Perdas Urias; S.A. = Conca Cannas, Canale Perdera and Riu Solacera. Pantelleria; B.V. = Bagno di Venere; S.V. = Salto la Vecchia and Balata dei Turchi. Melos; D. = Demenegaki; N.A.S. = Nihia, Adamas and Sarakiniko).

Specifically, samples 1, 2, 3a, 3b, 4, 7, 8 and 10a originate from Palmarola, samples 10b and 11 originate from Lipari, and samples 5, 9 (sub-source S.A.) and 6 (sub-source S.C.) originate from Monte Arci.

The peculiarity of three distinct source areas within the same archaeological site, one even represented by two sub-sources, suggested that SEM-EDS investigations should be performed in order to further constrain the analytical data obtained using WD-XRF. EDS microanalysis of the obsidian glass (Table 3) shows that the samples were quite altered during the period of their burial. In fact, the value of alkaline elements, in particular Na2O, is relatively low, less than 4%, and sometimes below 2%.

Table 3.

SEM-EDS microanalyses of obsidian glass from Maddalena di Muccia (oxides expressed in wt%); the values reported in the table represent the mean of three determinations. C.I.A. is the Chemical Index of Alteration [Al2O3/(Al2O3 + CaO + Na2O + K2O) in mol.%].

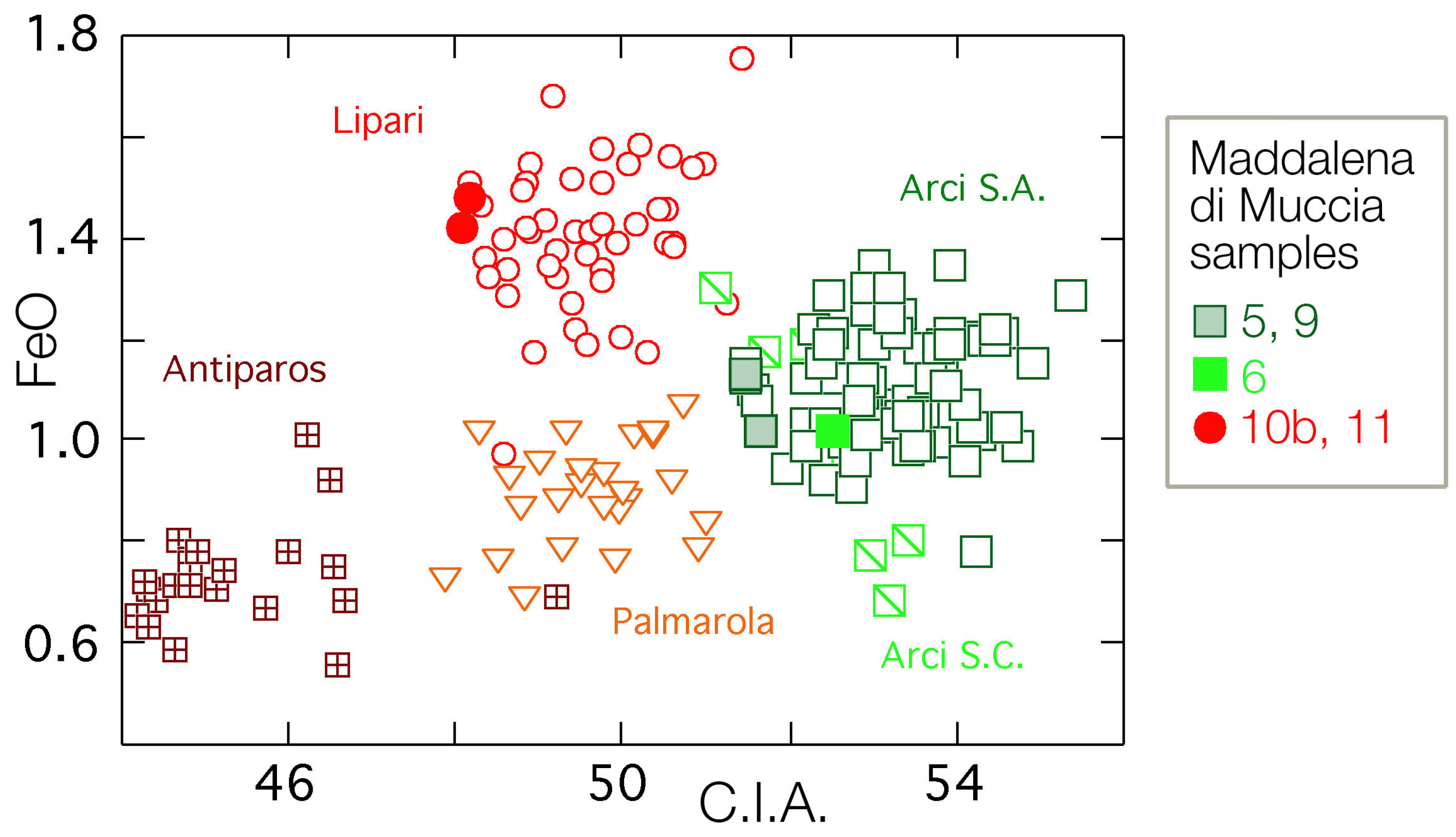

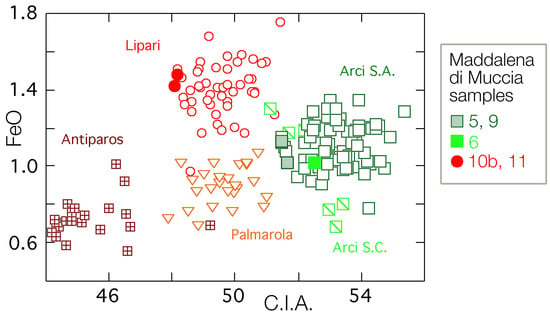

In some cases, however, glass analysis confirmed that samples 10b and 11 originated from Lipari and that samples 5, 6 and 9 originated from Monte Arci, and it attributed samples 5 and 9 to sub-source S.A. and sample 6 to sub-source S.C. (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

SEM-EDS microanalyses of the major obsidian source areas in the Mediterranean basin (data from [2,39]); obsidian samples 5 and 9 (green squares), 6 (light green square) and 10b and 11 (red circles) from the Maddalena di Muccia site (glass analyses, representing the mean value of five microanalyses) are also plotted. Sub-source outcrops: Monte Arci, S.C. = Perdas Urias; S.A. = Conca Cannas, Canale Perdera and Riu Solacera.

Unfortunately, for the samples ascribed to Palmarola geological outcrops using WD-XRF, it was not possible to confirm their origin solely through glass analysis, due to both the surface alteration of the artefacts and the presence of thin carbonate concretions (e.g., Table 1, photo of samples MAD01–MAD03b). Fortunately, the presence of pyroxene crystals (Figure 6), although very small and often with a skeletal texture, allowed the attribution of some samples to the Palmarola source area (Figure 7, Table 4).

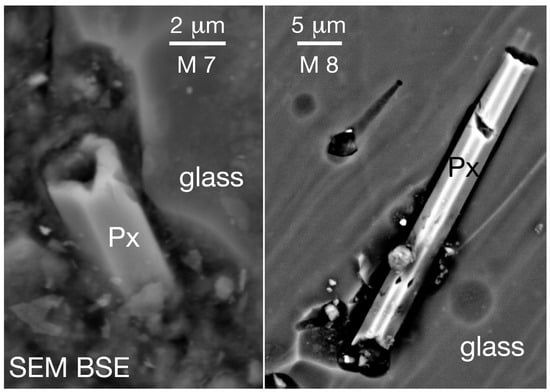

Figure 6.

Backscattered SEM images of pyroxenes in obsidian samples M7 and M8; the pyroxene of the M7 sample shows a skeletal texture, an indicator of rapid crystallisation.

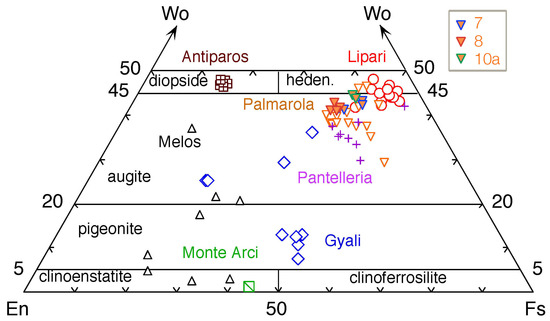

Figure 7.

Compositions of pyroxenes according to the [40] nomenclature for the major obsidian source areas in the Mediterranean (data from [11,39]); pyroxenes from samples 7, 8 and 10a of the Maddalena di Muccia site are plotted as solid symbols. En: enstatite; Fs: ferrosilite; Wo: wollastonite; Aug: augite.

Table 4.

Pyroxene microanalyses (oxides expressed in wt%) of the Maddalena di Muccia obsidian samples; formula based on 6 oxygens. En: enstatite; Fs: ferrosilite; Wo: wollastonite.

SEM-EDS microanalysis of biotite microphenocrysts present in the glass of obsidian artefacts, easily recognisable using backscattered electron images (Figure 8), confirms that samples 5, 6 and 9 were collected from Monte Arci geological outcrops, specifically sub-source S.A. for samples 5 and 9 and sub-source S.C. for sample 6 (Figure 9, Table 5).

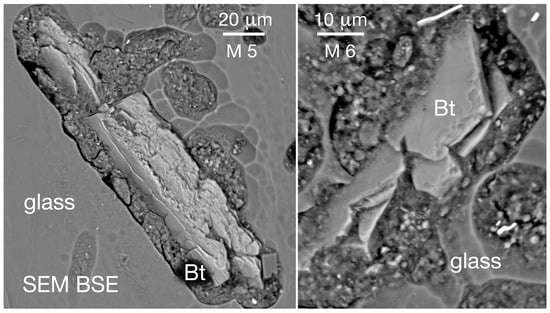

Figure 8.

Backscattered SEM images of biotites in the M5 and M6 obsidian samples; the surface of the glass of the samples often shows widespread alteration minerals.

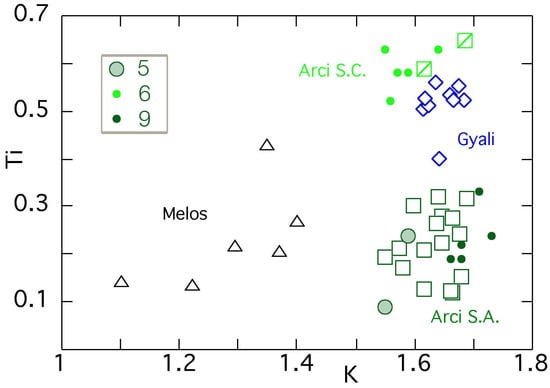

Figure 9.

Composition of biotites plotted on a K vs. Ti diagram for the major Mediterranean obsidian source areas (data from [11]); biotite from samples 5, 6 and 9 of the Maddalena di Muccia site are plotted as solid symbols. Sub-source outcrops: Monte Arci, S.C. = Perdas Urias; S.A. = Conca Cannas, Canale Perdera and Riu Solacera.

Table 5.

Biotite microanalyses (oxides expressed in wt%) of the Maddalena di Muccia obsidian samples; formula based on 22 oxygens.

Ultimately, the petroarchaeometric characterisation of obsidian using WD-XRF and SEM-EDS shows that the obsidian samples from the Neolithic and Copper Age phases of Maddalena di Muccia are attributable to three different source areas: Lipari, Palmarola and Monte Arci (Table 6). Two sub-sources within the Monte Arci source area are identifiable: Perdas Urias (S.C.) and Conca Cannas, Canale Perdera and Riu Solacera (S.A.).

Table 6.

The provenance, contexts and dating of the analysed obsidian artefacts. (?) = uncertain attribution.

4. Discussion

We can now compare our results with previously published data (Table 7) on the provenance of obsidian from Early to Late Neolithic sites in the Marche region [37,41,42,43,44,45,46,47] and, more broadly, the middle Adriatic regions of Italy from Emilia-Romagna to Abruzzo [24,45,46,47,48,49,50,51]. The data presented in Table 7 derive from studies carried out over an extended period of time and within different analytical and research frameworks; consequently, the proportion of characterised artefacts relative to the total assemblages cannot always be established, and the resulting datasets should not be regarded as statistically comparable. Nevertheless, when considered collectively, these data provide valuable evidence for reconstructing the spatial extent and diachronic development of the circulation of different obsidian sources over time.

Table 7.

Summary of obsidian provenance data from archaeological sites in the middle Adriatic regions of Emilia-Romagna, Marche and Abruzzo (EN = Early Neolithic; MN = Middle Neolithic; RN = Recent Neolithic; FN = Final Neolithic; CA = Copper Age). n.d. = not determined.

To enhance clarity without implying statistical comparability, Table 8 summarises the absolute number of characterised artefacts by source and chronological phase. In fact, in Table 7, the proportion of characterised artefacts relative to the original assemblages is not consistently known; therefore, the data should not be considered statistically representative.

Table 8.

Absolute number of characterised artefacts by source and chronological phase referring to sites in the Central Adriatic region of Italy. The table aggregates only the analysed materials reported in Table 7 and is intended as a descriptive overview. (EN = Early Neolithic; MN = Middle Neolithic; RN = Recent Neolithic; FN = Final Neolithic; CA = Copper Age). n.d. = not determined.

Lipari appears to have been the primary source of obsidian in the central Mediterranean area and clearly has the widest distribution throughout Italy [51,54,55]. Our results, therefore, are in line with those from many other Early to Late Neolithic inland and coastal sites in the Marche [56]: Obsidian from Lipari is predominant and, at times, the only source present across all Neolithic periods.

The exclusive presence of obsidian from Lipari at the Early Neolithic sites of Portonovo, Ripabianca di Monterado and, more recently, at the Esanatoglia site (unpublished analytical data reported in [53,57]) suggests the existence of consolidated strategies for procuring raw materials. An Early Neolithic spread of Pontine obsidian, alongside that from Lipari, through trans-Apennine routes to the west, covering significant distances, between the Tyrrhenian and the middle Adriatic coasts, is suggested by the predominant presence of obsidian from Palmarola [58] at the northern Early Neolithic site of Fornace Cappuccini in Emilia-Romagna (n = 20, 62.5% of the analysed samples [51,59,60,61]), with artefacts from Lipari, and at the southern Early Neolithic sites of Marcianese (n = 2, without artefacts from Lipari) and especially Colle Santo Stefano (n = 20, more than 70% of the samples analysed [62]).

Very limited obsidian from Palmarola had previously been identified by [42,46,47] at the inland multi-phase site of Maddalena di Muccia (n = 2, 25% of the analysed samples), albeit without any secure attribution to the Neolithic and/or Copper Age phases here attested, and at the Recent Neolithic settlement of Villa Panezia (n = 1, 100% of the samples analysed). By contrast, the predominance of Palmarola obsidian from securely stratified Early Neolithic contexts at Maddalena di Muccia (n = 5 from SU 114, 38.5% of the analysed samples) documented by the present study confirms the widespread circulation of Pontine obsidian during the Early Neolithic. These new data highlight how, at the beginning of the 6th millennium BC, communities in central Adriatic Italy were fully integrated into wide-ranging exchange networks, capable of overcoming apparent physical barriers such as the Apennine chain.

During the subsequent phases of the Neolithic, circulation certainly intensified and became systematic. Obsidian from Lipari became the predominant type, sometimes to the exclusion of all others, from Mid-Neolithic phases onwards, as at Santa Maria in Selva (n = 93, 100% of the samples analysed [63]). Obsidian from Palmarola is attested, together with artefacts from Lipari, in many Middle to Late Neolithic villages in Abruzzo [64] such as Catignano (n = 13, 7% of the samples analysed [65]), Colle Cera (n = 11, 12.5% of the samples analysed), Villa Badessa (n = 2, 50% of the samples analysed), Fossacesia (n = 5, 10% of the samples analysed), not distant from the Adriatic coast, and at the inland settlements of Settefonti (n = 8, 57% of the samples analysed [66]), confirming overland trans-Apennine exchange networks.

The provenance from the island of Pantelleria of one specimen found in the Recent Neolithic site of Fossacesia (Table 5.3 [46]; Table 9.2 [47]) has hitherto not been confirmed by edited analytical data (it is not reported in [45]: 540, Figure 3), nor has the related sub-source been identified. In any case, the sample from Pantelleria at the Late Neolithic necropolis of Galliano (sub-source of Salto la Vecchia and Balata dei Turchi [67]), in a chronologically well-defined context (T5 dated to LTL15556A: 5628 ± 45 BP, 4543–4357 BC), significantly expands its known distribution area toward the Adriatic regions during the second half of the 5th millennium BC, compared to the previously recognised, more restricted distribution limited to Western Sicily, Malta and the northern coast of Tunisia [68].

The three obsidian samples from Monte Arci [69] documented at Maddalena di Muccia from two different sub-sources (S.A. and S.C. types) currently represent the only evidence of multiple Sardinian obsidian sub-sources identified along the Adriatic coast. The presence of a Sardinian obsidian in the Marche is reported in two previously cited papers (Table 5.3 [46]; Table 9.2 [47]), but its archaeological provenance is not further specified, except for the presumed date of sampling of “Mar 02”, nor has the related sub-source been identified.

The discovery of one tiny bladelet from Sardinia (S.C. type) in Puglia, in the karstic doline of Pulo di Molfetta on the Adriatic coast [38], has already expanded the geographical range of Monte Arci obsidian exploitation and distribution from Sardinia to Southern Italy during the Neolithic. More recently, obsidian artefacts from the S.A. and SB2 sources have been recovered from the Late Neolithic layers (Spatarella facies) of the cave at San Michele Arcangelo di Saracena [70]. An exclusive presence of obsidian from Monte Arci (without indication of the intra-island sub-sources) was identified by [46,47] (tab. 5.5 and tab. 9.4 respectively) at the otherwise unknown site of Masseria di Gioia (Brindisi province, Puglia), documented only by surface materials from archaeological surveys.

On the Tyrrhenian side, Sardinian sources account for all of the obsidian found in Sardinia and Corsica, and, until now, have been documented only in Central Italy (Tuscany and Lazio) and Northern Italy (Liguria and several sites north of the Po River) [52,71,72,73].

Obsidian from Sardinia, frequently in association with that from Lipari, is well-documented in northern Tuscany at Grotta all’Onda, Neto di Bolasse, Podere Casanova, Spazzavento and Neto-Via Verga [45,51,71]. In southern Tuscany (as at La Consuma and La Chiarentana), a more significant role of contact with the south of Italy is confirmed by the presence of obsidian from Palmarola. Obsidian from Monte Arci is rarely attested south of the Tiber River; in southern Lazio, it is so far documented only at the sites of Casali di Porta Medaglia (Rome [74,75]) and Casale del Dolce (Anagni [76]).

Obsidian circulation declines after the end of the Neolithic, but, although episodic, it continues throughout the Copper Age. In the Rome area, where numerous settlements and necropoleis span a broad chronological range between the 4th and 3rd millennia BCE, obsidian is attested in the form of cores, débitage, and tools in Middle Copper Age contexts associated with the Gaudo facies (Casetta Mistici, Tor Pagnotta), as well as in Late Copper Age contexts corresponding to the Laterza and Ortucchio facies (Casale Massima, Osteria del Curato-Via Cinquefrondi, Quadrato di Torre Spaccata) [77,78]. Obsidian artefacts are also found in graves of the Middle Copper Age Rinaldone facies (Lucrezia Romana t.67, Ponte delle Sette Miglia t.6, Osteria del Curato t.7 [79]). Notably, two large obsidian cores were included among the grave goods of a Rinaldone burial at Sgurgola-Casali, also in Lazio [80,81]. At Maddalena di Muccia, obsidian appears to enter the site primarily as finished products, mostly in the form of bladelets. Nevertheless, the assemblage is numerically too small to allow robust conclusions about the modalities of the raw material’s introduction to the site.

One of the key contributions of the present study is the documentation of obsidian use at Maddalena di Muccia during the final phases of the Copper Age, a period for which evidence has been comparatively scarce. Notably, three of the eight analysed artefacts are attributed to Monte Arci, including multiple sub-sources, indicating a continued circulation of obsidian from different primary sources into the late Copper Age. The presence of Sardinian obsidian could reflect embedded procurement potentially linked to other high-quality raw materials, such as silver. No direct evidence of silver is documented at Maddalena di Muccia, nor at other Copper Age sites in the Adriatic regions of Italy; except for a silver sheet fragment recovered from the cemetery of Celletta dei Passeri (Emilia-Romagna) [82]. Nevertheless, silver from Sardinian sources is geochemically attested at contemporary sites in the Rome area [83,84]. Inland communities of Central Italy, located along natural trans-Apennine communication routes, may have acted as intermediary nodes facilitating these broader exchange networks. Taken together, our results highlight the complexity and continuity of resource circulation and provide new insights into the role of central Italian communities within long-distance interaction systems during the late Copper Age.

5. Conclusions

Petroarchaeometric characterisation of obsidian artefacts of the Maddalena di Muccia site, performed using non-destructive techniques on both the glass matrix and the microphenocrysts, allowed the identification of three different volcanic source areas in the Mediterranean region (i.e., Palmarola, Lipari, and Monte Arci) and, for one of these, even two different sub-sources (i.e., Monte Arci S.A. and Monte Arci S.C.). The study provides, in particular, the first evidence in the Adriatic region of the significant and simultaneous presence of obsidian artefacts originating from multiple sub-sources of Monte Arci, suggesting a lasting and long-term exchange of Sardinian obsidian along with that coming from other Mediterranean sources.

The assemblage of Maddalena di Muccia provides significant data for several reasons. First, they confirm the predominant use of Palmarola obsidian in the Early Neolithic. Second, they show the continued use of obsidian into the Copper Age. Although some artefacts may represent the reuse of materials from older structures, as suggested by double patina, others are clearly associated with the Copper Age settlement phase. Consistent with observations in the Roman area, the quantity of obsidian increases in the final Eneolithic phases.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, P.A., I.M.M., C.C.B. and E.G.; methodology, P.A.; formal analysis, P.A. and M.P.; investigation, P.A., I.M.M. and C.C.B.; data curation, P.A. and I.M.M.; writing—original draft preparation, P.A. and I.M.M.; writing—review and editing, P.A., I.M.M., C.C.B. and E.G.; visualisation, P.A. and I.M.M.; supervision, P.A. and I.M.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Nicola Mongelli for help in carrying out the SEM-EDS analyses, which were performed with an SDD detector at the “Laboratorio per lo Sviluppo Integrato delle Scienze e delle Tecnologie dei Materiali Avanzati e per dispositivi innovativi (SISTEMA)” of the University of Bari Aldo Moro.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Cann, J.R.; Renfrew, C. The characterization of obsidian and its application to the Mediterranean Region. Proc. Prehist. Soc. 1964, 30, 111–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acquafredda, P.; Andriani, T.; Lorenzoni, S.; Zanettin, E. Chemical characterization of obsidians from different Mediterranean sources by non-destructive SEM-EDS analytical method. J. Archaeol. Sci. 1999, 26, 315–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigazzi, G.; Oddone, M.; Radi, G. The Italian obsidian sources. Archeometriai Műhely 2005, 1, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Robb, J.E.; Farr, R.H. Substances in motion: Neolithic Mediterranean “trade”. In The Archaeology of Mediterranean Prehistory; Blake, E., Knapp, B., Eds.; Blackwell Publishing Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2005; pp. 24–45. [Google Scholar]

- Le Bourdonnec, F.X.; Poupeau, G.; Lugliè, C. SEM–EDS analysis of western Mediterranean obsidians: A new tool for Neolithic provenance studies. C. R. Geosci. 2006, 338, 1150–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negrino, F.; Radi, G. Osservazioni sulle tecniche e i metodi di scheggiatura dell’ossidiana nel Neolitico d’Italia. In Materie Prime e Scambi Nella Preistoria Italiana. Atti Della XXXIX Riunione Scientifica dell’Istituto Italiano di Preistoria e Protostoria; Istituto Italiano di Preistoria e Protostoria: Firenze, Italy, 2006; pp. 549–561. [Google Scholar]

- Poupeau, G.; Lugliè, C.; D’Anna, A.; Carter, T.; Le Bourdonnec, F.-X.; Bellot-Gurlet, L.; Bressy, C. Circulation et origine de l’obsidienne préhistorique en Méditerranée: Un bilan de cinquante années de recherches. In Archéologie des Rivages Méditerranéens: 50 ans de Recherche, Actes du Colloque d’Arles; Delestre, X., Marchesi, H., Eds.; Éditions Errance: Paris, France, 2010; pp. 183–191. [Google Scholar]

- Freund, K.P. An assessment of the current applications and future directions of obsidian sourcing in archaeological research. Archaeometry 2013, 55, 779–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, D.E.; D’Auria, J.M.; Bennett, R.B. Characterization of Pacific Northwest coast obsidian by X-ray fluorescence analysis. Archaeometry 1975, 17, 85–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Francesco, A.M.; Crisci, G.M.; Bocci, M. Non-destructive analytic method using XRF for determination of provenance of archaeological obsidians from the Mediterranean area: A comparison with traditional XRF methods. Archaeometry 2008, 50, 337–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acquafredda, P.; Paglionico, A. SEM-EDS microanalyses of microphenocrysts of Mediterranean obsidians: A preliminary approach to source discrimination. Eur. J. Mineral. 2004, 16, 419–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tykot, R.H. Chemical fingerprinting and source tracing of obsidian: The Central Mediterranean trade in black gold. Acc. Chem. Res. 2002, 35, 618–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gratuze, B.; Blet-Lemarquand, M.; Barrandon, J.N. Mass spectrometry with laser sampling: A new tool to characterize archaeological materials. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem. 2001, 26, 869–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, S.C.; Speakman, R.J. Initial source evaluation of archaeological obsidian from the Kuril Islands of the Russian Far East using portable XRF. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2009, 36, 1256–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frahm, E.; Doonan, R.C.P.; Kilikoglou, V. Handheld portable X-ray fluorescence of Aegean obsidians. Archaeometry 2014, 56, 228–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazaroff, A.J.; Prufer, K.M.; Drake, B.L. Assessing the applicability of portable X-ray fluorescence spectrometry for obsidian provenance research in the Maya lowlands? J. Archaeol. Sci. 2010, 37, 885–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shackley, M.S. Portable X-ray Fluorescence Spectrometry (pXRF): The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly (online essay). Archaeol. Southwest Mag. 2012, 26, 1–8, online exclusive essay. [Google Scholar]

- Forster, N.; Grave, P. Non-destructive PXRF analysis of museum-curated obsidian from the Near East. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2012, 39, 728–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millhauser, J.K.; Rodríguez-Alegría, E.; Glascock, M.D. Testing the accuracy of portable X-ray fluorescence to study Aztec and Colonial obsidian supply at Xaltocan, Mexico. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2011, 38, 3141–3152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frahm, E. Characterizing obsidian sources with portable XRF: Accuracy, reproducibility, and field relationships in a case study from Armenia. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2014, 49, 105–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frahm, E.; Schmidt, B.; Gasparyan, B.; Yeritsyan, B.; Karapetian, S.; Meliksetian, K.; Adler, D.S. Ten seconds in the field: Rapid Armenian obsidian sourcing with portable XRF to inform excavations and surveys. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2014, 41, 333–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conrey, R.M.; Goodman-Elgar, M.; Bettencourt, N.; Seyfarth, A.; Van Hoose, A.; Wolff, J.A. Calibration of a portable X-ray fluorescence spectrometer in the analysis of archaeological samples using influence coefficients. Geochem. Explor. Environ. Anal. 2014, 14, 291–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milić, M. PXRF characterisation of obsidian from Central Anatolia, the Aegean and central Europe. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2014, 41, 285–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tykot, R.H. Obsidian studies in the prehistoric Central Mediterranean: After 50 years, what have we learned and what still needs to be done? Open Archaeol. 2017, 3, 264–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tykot, R.H. A decade of portable (handheld) X-ray fluorescence spectrometer analysis of obsidian in the Mediterranean: Many advantages and few limitations. MRS Adv. 2017, 2, 1769–1784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frahm, E. The Obsidian sources of eastern Turkey and the Caucasus: Geochemistry, geology and geochronology. J. Archaeol. Sci. Rep. 2023, 49, 104011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frahm, E. Obsidian sources from the Aegean to central Turkey: Geochemistry, geology, and geochronology. J. Archaeol. Sci. Rep. 2023, 52, 104224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chataigner, C.; Gratuze, B. New data on the exploitation of obsidian in the southern Caucasus (Armenia, Georgia) and eastern Turkey, Part 1: Source characterization. Archaeometry 2014, 56, 25–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chataigner, C.; Gratuze, B. New data on the exploitation of obsidian in the southern Caucasus (Armenia, Georgia) and eastern Turkey, Part 2: Obsidian procurement from the Upper Palaeolithic to the Late Bronze age. Archaeometry 2014, 56, 48–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conati Barbaro, C.; Manfredini, A. (Eds.) Genti d’Appennino. Il Villaggio Eneolitico di Maddalena di Muccia (Macerata); Origines, Istituto Italiano di Preistoria e Protostoria: Firenze, Italy, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Acquafredda, P.; Muntoni, I.M.; Pallara, M. Reassessment of the WD-XRF method for obsidian provenance shareable databases. Quat. Int. 2018, 468, 169–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moscone, D.; Pallara, M.; Azadi, A.; Acquafredda, P.; Ricci, A. Socio-cultural connectivity along the Zagros Mountains: A SEM-EDS study of rare Neolithic obsidian artefacts from the Kohgiluyeh region (southwest Iran). Geoarchaeology 2025, 40, e70013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leoni, L.; Saitta, M. X-ray fluorescence analysis of 29 trace elements in rock and mineral standards. Rend. Soc. Ital. Mineral. Petrol. 1976, 32, 497–510. [Google Scholar]

- Leoni, L.; Saitta, M. Determination of yttrium and niobium on standard silicate rocks by X-ray fluorescence analyses. X-Ray Spectrom. 1976, 5, 29–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pouchou, J.L.; Pichoir, F. A simplified version of the “PAP” model for matrix corrections in EPMA. In Microbeam Analysis; Newbury, D.E., Ed.; San Francisco Press: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1988; pp. 315–318. [Google Scholar]

- Pouchou, J.L.; Pichoir, F. Quantitative analysis of homogeneous or stratified microvolumes applying the model “PAP”. In Electron Probe Quantitation; Heinrich, K.F.J., Newbury, D.E., Eds.; Plenum Press: New York, NY, USA, 1991; pp. 31–75. [Google Scholar]

- Acquafredda, P.; Muntoni, I.M.; Pallara, M. SEM-EDS and XRF characterization of obsidian bladelets from Portonovo (AN) to identify raw material provenance. Origini 2013, 35, 69–82. [Google Scholar]

- Acquafredda, P.; Muntoni, I.M. Obsidian from Pulo di Molfetta (Bari, southern Italy): Provenance from Lipari and first recognition of a Neolithic sample from Monte Arci (Sardinia). J. Archaeol. Sci. 2008, 955, 947–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acquafredda, P.; Micheletti, F.; Muntoni, I.M.; Pallara, M.; Tykot, R.H. Petroarchaeometric data on Antiparos obsidian (Greece) for provenance study by SEM-EDS and XRF. Open Archaeol. 2019, 5, 18–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morimoto, N. Nomenclature of Pyroxenes. Can. Mineral. 1989, 27, 143–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonelli, F.; Crisci, G.M.; De Francesco, A.M.; Silvestrini, M. Provenienza delle ossidiane di siti archeologici neolitici delle Marche. Plinius 2002, 28, 28–29. [Google Scholar]

- Antonelli, F.; De Francesco, A.M.; Crisci, G.M.; Silvestrini, M. Le ossidiane degli insediamenti neolitici delle Marche: Provenienza ed implicazioni archeologiche. In Atti del Convegno dell’A.I.Ar.: Innovazioni Tecnologiche per i Beni Culturali in Italia; D’Amico, C., Ed.; Pàtron Editore: Bologna, Italy, 2006; pp. 303–311. [Google Scholar]

- Barca, D.; De Francesco, A.M.; Crisci, G.M.; Tozzi, C. Provenance of obsidian artifacts from site of Colle Cera, Italy, by LA-ICP-MS method. Period. Mineral. 2008, 77, 41–52. [Google Scholar]

- De Francesco, A.M.; Crisci, G.M. L’economia. L’ossidiana. In Gli Scavi nel Villaggio Neolitico di Catignano (1971–1980); Tozzi, C., Zamagni, B., Eds.; Istituto Italiano di Preistoria e Protostoria: Firenze, Italy, 2003; pp. 239–240. [Google Scholar]

- De Francesco, A.M.; Bocci, M.; Crisci, G.M.; Lo Vetro, D.; Martini, F.; Tozzi, C.; Radi, G.; Sarti, L.; Cuda, M.T.; Silvestrini, M. Applicazione della metodologia analitica non distruttiva in Fluorescenza X per la determinazione della provenienza delle ossidiane archeologiche del Progetto “Materie Prime” dell’I.I.P.P. In Materie Prime e Scambi Nella Preistoria Italiana. Atti Della XXXIX Riunione Scientifica dell’Istituto Italiano di Preistoria e Protostoria; Istituto Italiano di Preistoria e Protostoria: Firenze, Italy, 2006; pp. 531–548. [Google Scholar]

- De Francesco, A.M.; Bocci, M.; Crisci, G.M. Non-destructive applications of wavelength XRF in obsidian studies. In X-Ray Fluorescence Spectrometry (XRF) in Geoarchaeology; Shackley, M.S., Ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 81–107. [Google Scholar]

- De Francesco, A.M.; Bocci, M.; Crisci, G.M.; Francaviglia, V. Obsidian provenance at several Italian and Corsican archaeological sites using the non-destructive X-ray fluorescence method. In Obsidian and Ancient Manufactured Glass; Liritzis, I., Stevenson, C.M., Eds.; University of New Mexico Press: Albuquerque, NM, USA, 2012; pp. 115–129. [Google Scholar]

- Ammerman, A.; Polglase, C. Obsidian at Neolithic sites in Northern Italy. Preist. Alp. 1998, 34, 291–296. [Google Scholar]

- Bigazzi, G.; Radi, G. Prehistoric exploitation of obsidian for tool making in the Italian peninsula: A picture from a rich fission-track dataset. In Atti XIII Congresso U.I.S.P.P. (Forlì, 8–14 Settembre 1996); Abaco: Forlì, Italy, 1998; Volume I, pp. 149–156. [Google Scholar]

- Bigazzi, G.; Radi, G. L’ossidiana in Abruzzo durante il Neolitico. In Preistoria e Protostoria dell’Abruzzo. Atti Della XXXVI Riunione Scientifica dell’Istituto Italiano di Preistoria e Protostoria; Istituto Italiano di Preistoria e Protostoria: Firenze, Italy, 2003; pp. 619–624. [Google Scholar]

- Pessina, A.; Radi, G. La diffusione dell’ossidiana nell’Italia centro-settentrionale. In Materie Prime e Scambi Nella Preistoria Italiana. Atti Della XXXIX Riunione Scientifica dell’Istituto Italiano di Preistoria e Protostoria; Istituto Italiano di Preistoria e Protostoria: Firenze, Italy, 2006; pp. 435–460. [Google Scholar]

- Bigazzi, G.; Radi, G. La diffusione dell’ossidiana nella penisola durante il Neolitico. In Le Comunità Della Preistoria Italiana. Studi e Ricerche sul Neolitico e le età dei Metalli. Atti Della XXXV Riunione Scientifica dell’Istituto Italiano di Preistoria e Protostoria; Istituto Italiano di Preistoria e Protostoria: Firenze, Italy, 2003; pp. 1005–1007. [Google Scholar]

- Acquafredda, P.; Muntoni, I.M. Obsidian provenance from archaeological sites of central and southern Italy: SEM-EDS and WD-XRF analyses to constrain data on Neolithic trades. In Sourcing Obsidian, A State-of-the-Art in the Framework of Archaeological Research; Le Bourdonnec, F.-X., Orange, M., Shackley, M.S., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; in press. [Google Scholar]

- Tykot, R.H. Obsidian use and trade in the Adriatic. In Adriatico Senza Confini; Visentini, P., Podrug, E., Eds.; Museo Friulano di Storia Naturale: Udine, Italy, 2014; pp. 171–181. [Google Scholar]

- Freund, K.P. A long-term perspective on the exploitation of Lipari obsidian in central Mediterranean prehistory. Quat. Int. 2018, 468, 109–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manfredini, A.; Sarti, L.; Silvestrini, M. Il Neolitico delle Marche. In Preistoria e Protostoria Delle Marche. Atti Della XXXVIII Riunione Scientifica dell’Istituto Italiano di Preistoria e Protostoria; Istituto Italiano di Preistoria e Protostoria: Firenze, Italy, 2005; pp. 197–208. [Google Scholar]

- Conati Barbaro, C.; La Marca, C.; Pellegrini, D.; D’Errico, D.; Stellacci, S.M. Gli agricoltori neolitici del medio Adriatico. Il sito di Piani di Calisti di Esanatoglia (MC, Marche). Riv. Di Sci. Preist. 2022, LXXII, 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Tykot, R.H.; Setzer, T.; Glascock, M.D.; Speakman, R.J. Identification and characterization of the obsidian sources on the island of Palmarola, Italy. Geoarchaeol. Bioarchaeol. Stud. 2005, 3, 107–111. [Google Scholar]

- Antoniazzi, A.; Bagolini, B.; Bermond Montanari, G.; Massi Pasi, M.; Prati, L. Il Neolitico di Fornace Cappuccini a Faenza e la Ceramica Impressa in Romagna. In Il Neolitico in Italia. Atti della XXVI Riunione Scientifica dell’Istituto Italiano di Preistoria e Protostoria; Istituto Italiano di Preistoria e Protostoria: Firenze, Italy, 1987; Volume II, pp. 553–564. [Google Scholar]

- Antoniazzi, A.; Bermond Montanari, G.; Giusberti, G.; Massi Pasi, M.; Mengoli, D.; Morico, G.; Prati, L. Lo scavo preistorico a Fornace Cappuccini. In Archeologia a Faenza: Ricerche e Scavi dal Neolitico al Rinascimento. Catalogo Della Mostra; Maioli, M., Massi Pasi, M., Gelichi, S., Eds.; Nuova Alfa Editoriale: Bologna, Italy, 1990; pp. 23–59. [Google Scholar]

- Sani, S.; Mazzucco, N.; Mengoli, D.; Starnini, E. The obsidian management in the central Mediterranean: A case study from Fornace Cappuccini (Northern Italy, early Neolithic). Archaeol. Data 2025, 5, 51–70. [Google Scholar]

- Radi, G.; Danese, E. L’abitato di Colle Santo Stefano di Ortucchhio (L’Aquila). In Preistoria e Protostoria dell’Abruzzo. Atti Della XXXVI Riunione Scientifica dell’Istituto Italiano di Preistoria e Protostoria; Istituto Italiano di Preistoria e Protostoria: Firenze, Italy, 2003; pp. 145–161. [Google Scholar]

- Martini, F.; Sarti, L.; Silvestrini, M.; Volante, N. L’insediamento di Santa Maria in Selva di Treia: Progetti e prospettive di ricerca. In Preistoria e Protostoria Delle Marche. Atti della XXXVIII Riunione Scientifica dell’Istituto Italiano di Preistoria e Protostoria; Istituto Italiano di Preistoria e Protostoria: Firenze, Italy, 2005; pp. 295–308. [Google Scholar]

- Grifoni Cremonesi, R. Il Neolitico dell’Abruzzo. In Preistoria e Protostoria dell’Abruzzo. Atti Della XXXVI Riunione Scientifica dell’Istituto Italiano di Preistoria e Protostoria; Istituto Italiano di Preistoria e Protostoria: Firenze, Italy, 2003; pp. 125–143. [Google Scholar]

- Tozzi, C.; Zamagni, B. Le nuove ricerche nel villaggio neolitico di Catignano (Pescara). In Preistoria e Protostoria dell’Abruzzo. Atti Della XXXVI Riunione Scientifica dell’Istituto Italiano di Preistoria e Protostoria; Istituto Italiano di Preistoria e Protostoria: Firenze, Italy, 2003; pp. 181–193. [Google Scholar]

- Radi, G.; Danese, E. Il sito neolitico di Settefonti a Prata d’Ansidonia. In Preistoria e Protostoria dell’Abruzzo. Atti Della XXXVI Riunione Scientifica dell’Istituto Italiano di Preistoria e Protostoria; Istituto Italiano di Preistoria e Protostoria: Firenze, Italy, 2003; pp. 163–179. [Google Scholar]

- Muntoni, I.M.; Micheletti, F.; Mongelli, N.; Pallara, M.; Acquafredda, P. First evidence in Italian mainland of Pantelleria obsidian: Highlights from WD-XRF and SEM-EDS characterization of Neolithic artefacts from Galliano necropolis (Taranto, Southern Italy). J. Archaeol. Sci. Rep. 2022, 45, 103553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tufano, E.; D’Amora, A.; Trifuoggi, M.; Tusa, S. L’ossidiana di Pantelleria: Studio di caratterizzazione e provenienza alla luce della scoperta di nuovi giacimenti. In Dai Ciclopi agli Ecisti. Societa e Territorio Nella Sicilia Preistorica e Protostorica. Atti Della XLI Riunione Scientifica dell’Istituto Italiano di Preistoria e Protostoria; Istituto Italiano di Preistoria e Protostoria: Firenze, Italy, 2012; pp. 839–849. [Google Scholar]

- Tykot, R.H. Characterization of the Monte Arci (Sardinia) obsidian sources. J. Archaeol. Sci. 1997, 24, 467–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forgia, V.; Tykot, R.H.; Vianello, A.; Natali, E. Obsidian from the Neolithic layers of “Grotta San Michele Arcangelo di Saracena” (Cosenza), Italy. A preliminary report. Open Archaeol. 2021, 7, 615–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanti, L.; Melosu, B. L’ossidiana del Monte Arci nella preistoria della Sardegna e del Mediterraneo centro-occidentale. Layers 2025, 10, 29–78. [Google Scholar]

- Tykot, R.H. Obsidian procurement and distribution in the central and western Mediterranean. J. Mediterr. Archaeol. 1996, 9, 39–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tykot, R.H.; Ammerman, A.J.; Bernabò Brea, M.; Glascock, M.D.; Speakman, R.J. Source analysis and the socioeconomic role of obsidian trade in northern Italy: New data from the Middle Neolithic site of Gaione. Geoarchaeol. Bioarchaeol. Stud. 2005, 3, 103–106. [Google Scholar]

- Guidi, G.F.; Moioli, P.; Trojsi, G.; Anzidei, A.P.; Carboni, G. Corrélation par spectrométrie XRF des obsidiennes en provenance des sites archéologiques de Quadrato di Torre Spaccata et de la zone de Maccarese (Roma) avec les obsidiennes du bassin de la Méditerranée. In Actes du XIVème Congres UISPP (Liège, 2–8 Septembre 2001); BAR IntS 1270: Oxford, UK, 2004; pp. 71–74. [Google Scholar]

- Guidi, G.F.; Moioli, P.; Trojsi, G. Caratterizzazione mediante spettrometria XRF non distruttiva di alcuni reperti in ossidiana provenienti dai siti di Casale di Valleranello, Quadrato di Torre Spaccata e Casali di Porta Medaglia (Roma). In Roma Prima del Mito. Abitati e Necropoli dal Neolitico alla Prima età dei Metalli nel Territorio di Roma (VI-III Millennio a.C.); Anzidei, A.P., Carboni, G., Eds.; Archaeopress: Oxford, UK, 2020; Volume 2, pp. 681–684. [Google Scholar]

- Petrassi, L.; Zarattini, A. Il valore dell’ossidiana e le vie terrestri: Ipotesi dopo i primi risultati della fluorescenza a raggi X. In Casale del Dolce. Ambiente, Economia e Cultura di una Comunità Preistorica Della Valle del Sacco; Zarattini, A., Petrassi, L., Eds.; TAV-Pegaso: Roma, Italy, 1997; pp. 191–208. [Google Scholar]

- Conati Barbaro, C. Le industrie litiche del territorio di Roma dal Neolitico alla fine dell’Età del Rame. In Roma Prima del Mito. Abitati e Necropoli dal Neolitico alla Prima età dei Metalli nel Territorio di Roma (VI-III Millennio a.C.); Anzidei, A.P., Carboni, G., Eds.; Archaeopress: Oxford, UK, 2020; Volume 2, pp. 401–408. [Google Scholar]

- Mulargia, M. L’industria litica scheggiata da contesti di abitato: Analisi tecno-tipologica. In Roma Prima del Mito. Abitati e Necropoli dal Neolitico alla Prima età dei Metalli nel Territorio di Roma (VI-III Millennio a.C.); Anzidei, A.P., Carboni, G., Eds.; Archaeopress: Oxford, UK, 2020; Volume 2, pp. 413–429. [Google Scholar]

- Anzidei, A.P.; Carboni, G. (Eds.) Roma prima del mito. In Abitati e Necropoli dal Neolitico alla Prima età dei Metalli nel Territorio di Roma (VI-III Millennio a.C.); Archaeopress: Oxford, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Pinza, G. Monumenti primitivi di Roma e del Lazio antico. In Monumenti Antichi; Accademia Nazionale dei Lincei: Roma, Italy, 1905; Volume XV, ISBN 10: 3805301987. [Google Scholar]

- Carboni, G. Territorio aperto o di frontiera? Nuove prospettive di ricerca per lo studio della distribuzione spaziale delle facies del Gaudo e di Rinaldone nel Lazio centro-meridionale. Origini 2002, 24, 235–301. [Google Scholar]

- Miari, M.; Bestetti, F.; Rasia, P.A. La necropoli eneolitica di Celletta dei Passeri (Forlì): Analisi delle sepolture e dei corredi funerari. Riv. Di Sci. Preist. 2017, LXVII, 145–208. [Google Scholar]

- Carboni, G. La Metallurgia del Rame, dell’argento e dell’antimonio Delle Facies di Rinaldone (Gruppo “Roma-Colli Albani”), del Gaudo e Delle Fasi di Abitato nel Territorio di Roma; Anzidei, A.P., Carboni, G., Eds.; Archaeopress: Oxford, UK, 2020; Volume 2, pp. 481–516. [Google Scholar]

- Aurisicchio, C.; Medeghini, L. Analisi dei Manufatti Metallici dell’età del Rame Provenienti dal Territorio di Roma e Suggerimenti Sulla Loro Provenienza; Anzidei, A.P., Carboni, G., Eds.; Archaeopress: Oxford, UK, 2020; Volume 2, pp. 531–547. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.