Abstract

This study identifies the technological signature of ancient and alternative “Chu” and “Kriab” gold glass mosaic mirrors from Thailand. Although these mirrors play an important role in Thai decorative heritage, their production routes and interfacial chemistry at the lead-to-glass interface have remained unclear. A survey of 154 sites across Thailand shows mosaic glass was widely distributed and likely produced during the Ayutthaya period (~300 years ago). Portable X-Ray Fluorescence (pXRF), Wavelength-Dispersive XRF (WD-XRF), scanning electron microscopy (SEM), and X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS) were used to examine the material properties of observed Chu mirrors. Most samples can be classified as a mixed lead–alkaline glass type, with a PbO content ranging from 4.28 to 48.17 wt%. Their yellow tone is controlled by iron and manganese redox states. Chemical and physical analyses distinguish between Chu from the northern part of Thailand and Kriab from the central part of Thailand, which share a silica source but rely on different fluxes, pointing to different glass workshops. Crucially, XPS depth profiling reveals a well-defined interfacial reaction zone extending to approximately 6 nm in the ancient mirrors, predominantly characterized by disordered, chain-like Pb–O–Pb linkages. These polymeric structures enable a “chemical bridging” mechanism that effectively accommodates interfacial strain arising from thermal expansion mismatch, thereby ensuring exceptional long-term adhesion. Furthermore, the depth-dependent distribution of hydrated lead species and the emergence of photoelectron energy-loss features beyond ~6 nm distinguish the superior metallic integrity of the ancient coatings from the alternative reproductions. This distinct stratification confirms that ancient artisans achieved a sophisticated balance between a chemically bonded interface and a coherent metallic bulk. These findings offer significant insights into the ingenuity of ancient Thai artisans, providing a scientific foundation for the conservation, restoration, and replication of these culturally significant artifacts.

1. Introduction

Thailand, a country with a large Buddhist population, is well-known for its custom of using elaborate, gleaming glass mosaic mirrors to decorate church buildings, temples, shrines, palaces, and other places or artifacts of worship. Although Thailand has evidence of ancient glass technology in parts of west–central Thailand, such as Khao Sam Kaeo (Chumphon province) and Ban Don Ta Phet (Kanchanaburi province) sites, dating back to the early Southeast Asian Iron Age (4th to 2nd century BCE), most of the artifacts discovered were beads, earrings, and bracelets [1,2]. Another intriguing site is Khlong Thom (Krabi province), where large glass chunks, weighing several kilograms, have been found. These discoveries suggest the possibility of primary glass production at the sites; however, the absence of high-temperature furnace evidence makes it challenging for archeologists to draw definitive conclusions [3]. Despite the significant discovery of early glass production, there have been no subsequent discoveries of glass production sites from later periods. The limited historical understanding of glass technology in Thailand further complicates efforts to trace the origins of early glass mosaic production, which has been discovered in the country since the late Ayutthaya period, around the early 18th century.

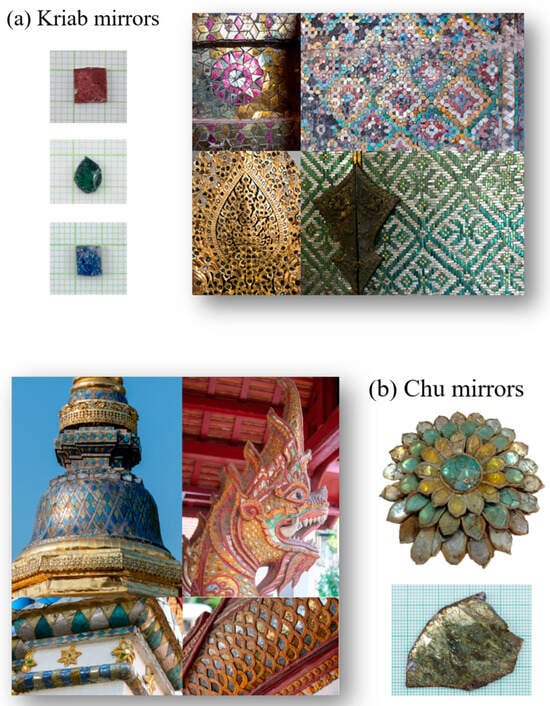

Our extensive investigations have identified two major groups of glass mosaic mirrors in Thailand: Kriab mirrors, predominantly found in the central regions, and Chu mirrors, more commonly seen in the northern areas, particularly in the old Lanna Kingdom, as illustrated in Figure 1. The spatial distribution of all sampling locations, along with their geographic coordinates (Global Positioning System, GPS), is provided in Tables S1 and S2. These locations, where Kriab and Chu glass types were identified, are also mapped in Figure 1. The majority of these mirrors were constructed from a lead silicate glass composition, with differences in the thickness of the glass and lead layers resulting in the emergence of unique creative morphologies. As shown in Figure 2a, Kriab mirrors are characterized by a relatively thicker glass layer, which makes them more rigid, durable, and visually vibrant. As a result, they are typically cut into small geometric pieces using glass-cutting tools and arranged in tessellated decorative patterns. In contrast, Chu mirrors (Figure 2b) have a thinner glass layer supported by a thicker and more flexible lead backing. Unlike the brittle Kriab type, Chu reproduction glass is significantly thinner, allowing it to be cut with iron scissors without fracturing. This enhanced mechanical workability enables the creation of intricate, curved inlays, as demonstrated in Video S1. These mirrors can be easily shaped into various forms and are commonly used to decorate carved wood, plaster reliefs, and inlay artworks.

Figure 1.

Spatial distribution of sampling locations where Kriab and Chu mirrors were identified across Thailand and selected sites in neighboring countries. GPS coordinates for each location are provided in Tables S1 and S2.

Figure 2.

Examples of Kriab and Chu mirrors and their use in archeological artifacts from various regions of Thailand: (a) Kriab mirrors arranged in tessellated decorative patterns, photographed in museum and exhibition collections in central Thailand; and (b) thin, flexible Chu mirrors used for curved inlay work, photographed in temples and museums in northern Thailand. Mirror fragments that had detached from the artifacts were collected with permission from the respective site owners. All photographs by Pengpat, K.

Regarding production methods, both glass blowing and hand-drawing techniques can produce glass with variable wall thickness. Consequently, both ancient and alternative mirrors may exhibit a range of glass thicknesses, depending on subsequent processing and artistic selection. The distinction between Kriab and Chu mirrors therefore reflects differences in material configuration, decorative practice, and cultural tradition, rather than the glass-forming method alone.

Extensive research has been conducted on the first type of these mirrors, known as Kriab [4,5,6,7,8], including a study we previously published [9]. In our earlier work, we analyzed the chemical and mechanical properties of Kriab mirror tesserae and restoration mirrors from the 18th and 19th centuries. The broader history of lead-coated glass has also been comprehensively reviewed [10]. Lead-backed convex mirrors first appeared during the Roman Empire (2nd–4th century CE) [10] and subsequently persisted in the Near East. By the 9th century, such mirrors had spread to Viking-age Europe [10,11], where their technological development and cultural significance have been well documented. Lead-coated mirrors were later produced in Islamic Spain, notably in a Murcian workshop dating to the 12th century [12]. By the Middle Ages, lead-backed glass mirrors with frames made of metal, wood, or ivory became commonplace [13,14]. The process of mirror-making underwent significant innovations during this period. In the 16th century, lead alloys, such as lead–bismuth amalgams, were introduced and later became valued commodities in the New World [15]. The German methods for mirror production played a key role in reviving the craft in Florence during the 16th century [16]. By 1500, tin foil amalgamation began to replace traditional leaded mirrors, and by the 19th century, silvering techniques using silver nitrate became widely adopted [17].

The origins of lead-coated glass mirrors in Thailand remain uncertain. The primary evidence comes from an old book by His Royal Highness Prince Krom Khun Worachak Phalanubhab, titled Tumra Hung Krachok Kriab (Production of Kriab Mirrors). This book suggests that Kriab mirrors might have been produced in royal glass workshops in Bangkok or central Thailand during the early Rattanakosin period or the 18th century [18]. However, the book provides limited details on the production process. Due to Bangkok’s extensive urbanization, no remnants of furnace kilns, glass-working tools, or raw glass fragments have been preserved. Nevertheless, as our research indicates, fragments of lead-coated glass mosaics are still found in numerous artifacts and archeological sites across Thailand. Chemical analysis of the glass composition remains a valuable method to trace the provenance, understand the production technology, and identify potential locations of these historic glass workshops.

Archeological evidence indicates that ancient glassmakers predominantly employed a soda–lime mixture in their manufacturing techniques. Silica originated from sand or crushed quartz, whereas soda or potash was obtained from plant ash, wood ash, or mineral deposits functioned as the fluxing agents in the majority of ancient glassware. These conclusions are derived from chemical analyses and archeological interpretations. The inclusions observed in some samples likely result from incomplete melting of the batch materials or from mineral impurities naturally present in the raw materials. Moreover, trace quantities of metal oxides, salts, lead, and antimony compounds were intentionally incorporated to alter the color of glass and opacity [19]. These components often displayed considerable contamination, owing to their natural sources or the associated production procedures. The interaction of these minor and trace components provides insights into the original formulations and raw ingredients, perhaps resulting in a distinctive “glass fingerprint.” Chemical traces can assist archeologists in determining whether glass artifacts discovered at a site were locally manufactured or imported via ancient trade networks. Nonetheless, glass recycling complicates the analysis of these results. Similarly to metal, glass can be liquefied and recycled, amalgamating components from many origins. The recycling procedure complicates data analysis and restricts conclusive determinations on the origin of archeological glass.

Through chemical analysis and the careful interpretation of archeological findings [19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26], it has been established that ancient glass production originated in the Near East during the mid-4th millennium BCE. Early “glassy faïence” techniques gradually evolved into the production of “real glass” around 1600 BCE in Mesopotamia and Egypt [27]. Early glass was made using silica-rich sand or quartz mixed with plant ash or natron as flux, with the addition of lime and metal oxides to enhance stability, color, and opacity. Over time, technological advancements and trade networks gave rise to distinct glass types, including natron soda–lime, plant ash/soda–lime, and mixed soda–potash glasses [28].

Lead glass production represents a significant technological advancement in early medieval Northwestern Europe, particularly with the emergence of mixed-alkali glass, a blend of wood-ash glass and natron soda–lime glass [29]. Lead was used to improve the properties of silica-based glass, serving as an opacifier, flux, or stabilizer. Historical examples include lead antimonate from 1500 BCE and lead–tin oxide from 200 BCE [30]. Notable uses include lead glass beads in Amenhotep III’s palace (1386–1353 BCE) and Roman-era soda–lead glass [31].

Eastern innovations included Chinese lead–barium–silicate glass and potash–silica glass, distinct to East Asia and spread regionally from the Warring States to the Han Dynasty [32,33]. Compared to wood-ash and soda glasses, lead glasses have lower viscosities at a practical melting temperature, which facilitates easier softening and processing during manufacture [34]. In the Carolingian period, high-lead silica glasses and mixed lead–alkaline glasses emerged in Europe, likely derived from lead–silver smelting by-products, such as glassy slag [35]. George Ravenscroft [36] revolutionized glassmaking in the 17th and 18th centuries with the invention of English crystal glass, notable for its exceptional purity achieved by increasing PbO content to 34–40%. Its low melting point and superior optical properties made lead glass highly versatile and commercially successful, cementing its importance in the advancement of glassmaking technology.

In this work, we focused on analyzing the chemical elements in the yellow glass layer, commonly referred to as ‘gold glass’ due to its resemblance to gold when coated with lead. Fragments of a Christmas bauble-shaped gold glass were discovered at a Bonn excavation site in a cremation burial dating back to the early 2nd century [10]. Additional evidence of similar glass has also been found in Germany [37].

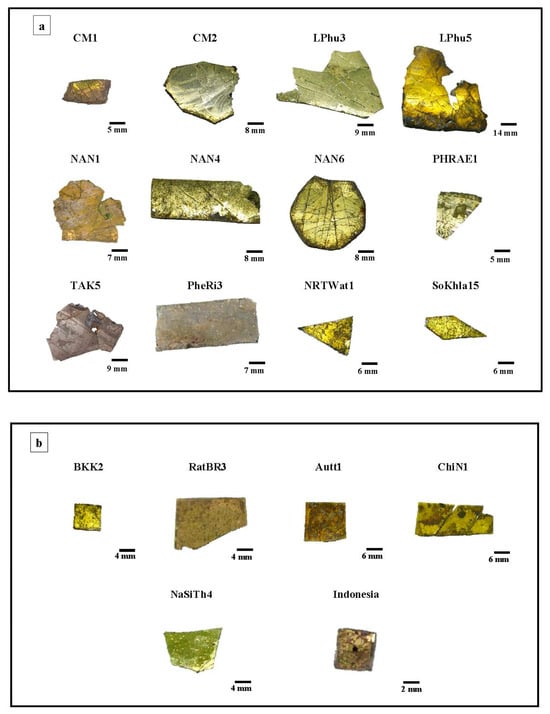

Given their gold-like appearance, the Kriab and Chu mirrors, as shown in Figure 3, are classified as ‘gold glass.’ These mirrors have been widely used to adorn various objects and archeological structures. Their historical significance continues to inspire the use of non-leaded yellow mirrors in upscale buildings, religious architecture, and antique designs across Thailand and neighboring countries.

Figure 3.

Selected Chu (a) and Kriab (b) “gold glass” mirrors from different locations in Thailand.

This research utilized chemical analysis to examine and categorize lead-coated glass mirrors in Thailand. Portable X-Ray Fluorescence (pXRF) and Wavelength-Dispersive XRF (WD-XRF) were employed to analyze the glass layers, while scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS) were used to investigate the lead–metal interface of flexible Chu mirrors, which include both ancient and alternative specimens; this will be discussed later in Section 2. The results demonstrate how useful this research is in creating a database that is open to the public and creating glass prototypes for conservation and restoration projects. In addition to highlighting Thailand’s historical significance as a center of Southeast Asian trade and culture, these technologies allow glass to be distinguished by date and place of origin.

2. Experimental Procedure

2.1. Sample Preparation

The selected “gold-glass” samples, as shown in Figure 3, were cleaned in deionized (DI) water by immersing them in an ultrasonic bath for two minutes, doing this once to remove the dirt and stain. After 30 min of oven drying, the samples were analyzed chemically using the PXRF and WD-XRF methods.

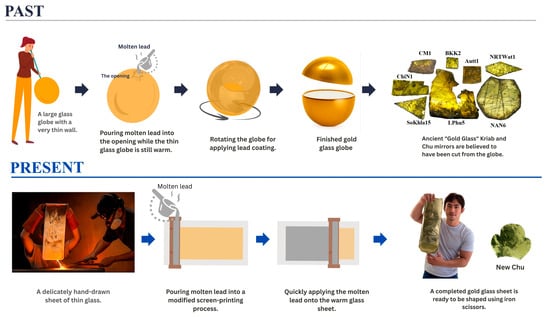

As previously mentioned, the old book Tumra Hung Krachok [18] does not provide details about the glass-blowing or lead-coating techniques required to replicate the production process. Historically, such knowledge was often kept as a family secret. Unfortunately, since the prince did not pass this knowledge on to successors, it was inevitably lost. However, Kock and Sode (2002) [11] reported a lead-coating technique used on large glass globes in Kapadvanj, Gujarat. These Western Indian glassworks are believed to have been made during the Mughal period, approximately 500 years ago. Based on Thailand’s long-standing connections with India and historical accounts describing possible glass production during the early Rattanakosin period, glass blowing was selected as a representative ancient glassmaking technique, while acknowledging that direct archeological evidence remains limited. Figure 4 (Past) illustrates the proposed schematic representation of how ancient glass workers crafted the ancient Thai mirrors.

Figure 4.

Schematic representation depicting the production process of lead-coated glass mosaic mirrors. (Past): It is possible that early glassblowers used simple methods, applying molten lead to hot glass spheres while they were still hot. (Present): Our research team and artisans at the Samart Handcrafted Thin-glass Workshop in Hang Dong, Chiang Mai, have developed and adopted contemporary and safer processes.

In our previous paper [9], we reported an initial attempt to reproduce these mirrors using a modified tape-casting technique, in which molten glass was poured directly onto a metal plate to form a thin glass layer and then rapidly coated on the reverse side with molten lead. However, this modified tape-casting method resulted in a dull surface because the hot glass adhered to the metal plate before being coated with liquid lead on the back. Additionally, the glass formula used in our first attempt, which contained high levels of lead and boron to lower the melting point, caused rapid corrosion due to phase separation.

This study explores the adaptation of traditional techniques by modifying the conventional glass-blowing process into a hand-drawing method developed by Mr. Choktavee Piboon, an artisan from the Samart Handcrafted Thin-Glass Workshop in Hang Dong, Chiang Mai, as shown in Figure 4 (Present). In this modified approach, an electric muffle furnace was used to melt 500 g of glass in an alumina crucible, which was then transferred to a drawing desk for shaping. The resulting drawn glass sheet, measuring approximately 80 cm × 120 cm, exhibited thickness variations ranging from about 0.3 mm at the top to 0.15 mm at the bottom. The glass sheet was subsequently coated with lead using an adapted screen-printing technique. High-purity lead (>99.98 wt%, Table S1) was used to minimize unwanted contamination. Unlike historical production methods that employed a glass globe, the present approach uses glass layer in sheet form, which makes it more difficult to prevent surface oxidation. To mitigate this effect, the molten lead was applied to the hot glass surface as rapidly as possible, promoting effective bonding between the layers and ensuring good optical reflectivity in the finished glass sheet.

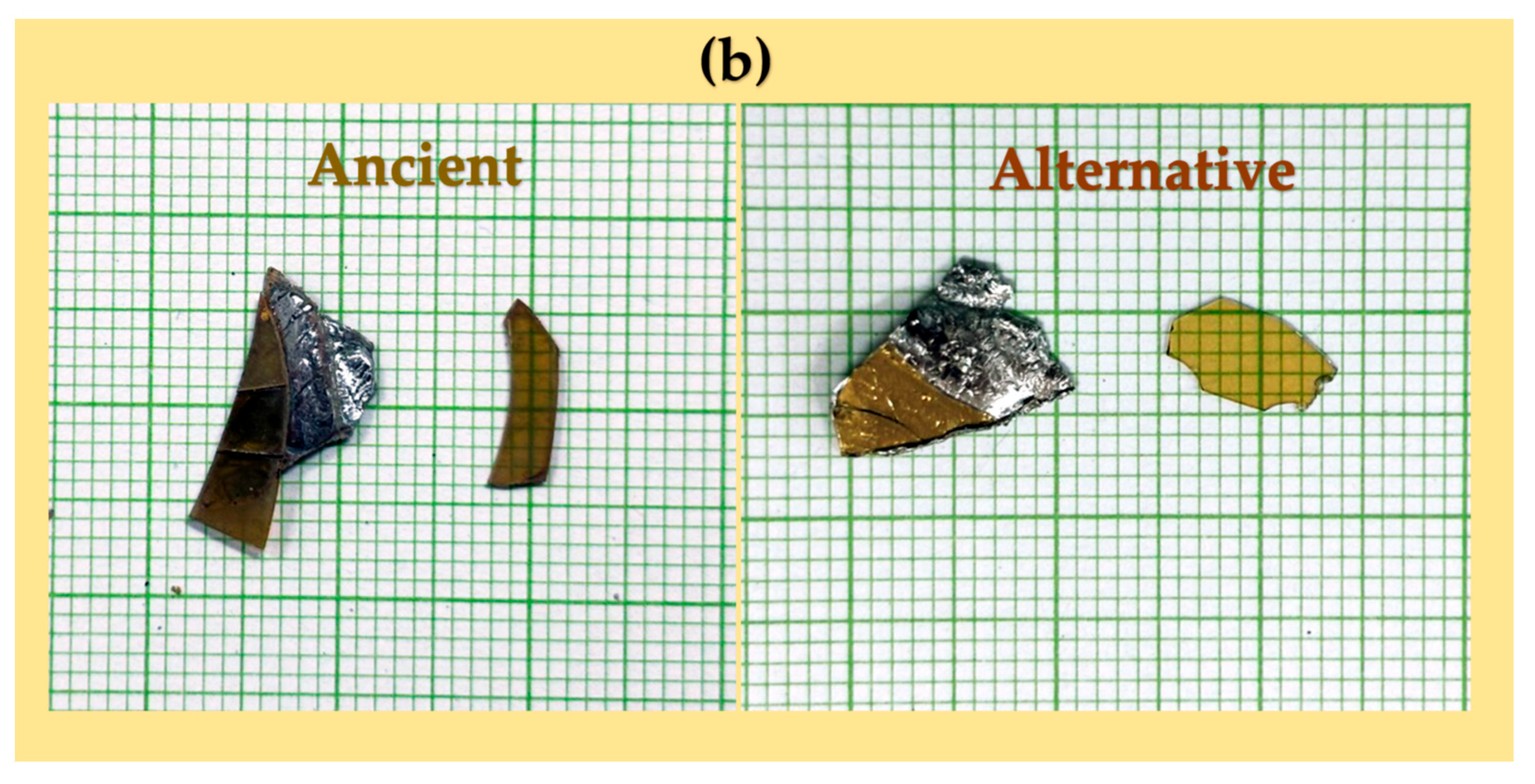

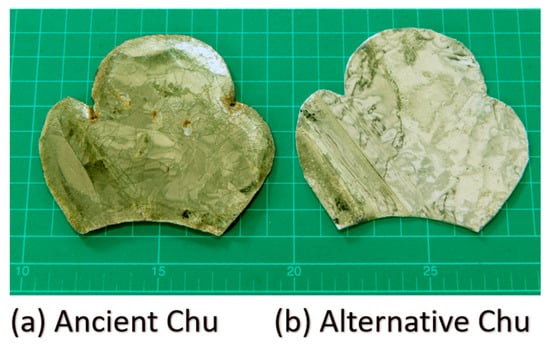

Preliminary analyses of the yellow glass layers in the ancient gold glass Kriab and Chu samples, which revealed significant variations, facilitated the approximation of a glass formula, as detailed in Table 1. The newly developed formula incorporates an optimized lead content and requires a melting temperature of 1400 °C for 2 h to achieve complete homogenization. All raw materials used in this study were of commercial grade. Figure 5 provides a comparison between the Chu mirror reproduced in this study and its ancient counterpart.

Table 1.

Nominal composition of the selected glass used for preparing the yellow glass sheet.

Figure 5.

Photographs of (a) ancient Chu and (b) alternative Chu samples taken using a digital camera (aperture f/8.0, ISO 200, 50 mm lens; 24.0–70.0 mm f/2.8). The scale is shown in centimeters.

2.2. Chemical Analysis

2.2.1. Wavelength-Dispersive Spectroscopy (WDS)

This study utilized a JSM-IT300 Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM) (JEOL Ltd., Akishima, Tokyo, Japan), equipped with Lanthanum Hexaboride Cathodes (LaB6) as the electron source, operating in high-vacuum (HV) mode. The instrument provided a resolution of 2.0 nm and an adjustable electron accelerating voltage range of 0.3–30 kV. Sample preparation involved cutting the specimen to a maximum diameter of 4 cm, cleaning it with ethanol, air-drying, mounting it on carbon-taped brass stubs, coating the surface with gold, and performing analysis using both WDS and EDS techniques. The examined elements were calibrated using JSM reference standards prior to measurement. Measurements were performed using the standard sample holder provided by the manufacturer. It should be noted that operation under high-vacuum conditions may induce partial evaporation of low-melting-point metals, such as lead. This potential effect was taken into account when assessing sample contamination, and the analyzed samples were not reused for subsequent examinations.

2.2.2. Handheld/Portable X-Ray Fluorescent Spectrometers—pXRF

The elemental compositions of the ancient Chu Mosaic mirrors were analyzed using the Olympus Vanta M Series Handheld X-ray Fluorescence (XRF) Analyzer (Evident Scientific, Tokyo, Japan), which provides semi-quantitative elemental data. For major elements, the typical detection limit is approximately 0.01 wt%, as commonly reported for portable XRF instruments. This portable device is well-suited for fieldwork, delivering results comparable to those from laboratory-grade equipment, making it highly versatile across various industries. The analyzer was equipped with a rhodium X-ray tube and employed dual-beam measurements: a high-energy beam at 40 kV and a low-energy beam at 13 kV, filtered through a 2 mm aluminum filter. Emitted X-rays were captured by a silicon detector, and PyMca software (version 5.9.4) [38] was used to fit the spectra and validate the analysis results, ensuring accurate and reliable measurements.

2.2.3. High-Performance Wavelength-Dispersive XRF Spectrometer: WD-XRF

The ancient “gold-glass” mirrors were analyzed using the S8 TIGER Series 2 Wavelength Dispersive X-ray Fluorescence (WD-XRF) system (Bruker AXS GmbH, Karlsruhe, Germany) to determine the type and quantity of elements in the samples based on the principles of X-ray fluorescence. The fragment of the samples can easily be mounted. This technique employs a wavelength-dispersive mechanism to detect elements ranging from beryllium (Be) to uranium (U) in both solid and liquid samples, with concentrations spanning from percentage levels to trace amounts in parts per million (ppm). The process begins with X-rays generated by the instrument interacting with the sample, inducing fluorescence. The emitted X-rays pass through a collimator to form a parallel beam, which is directed at analyzing a crystal within a vacuum spectrometer. The crystal disperses the X-rays by wavelength, and detectors convert the resulting signals into spectra that reveal the elemental composition of the sample. This method is well recognized for its high spectral resolution and quantitative reliability, with a typical analytical precision of approximately 0.01 wt% for major and minor elements. This performance arises from the effective separation of closely spaced elemental peaks and reduced matrix interference, enabling robust and reproducible elemental analyses suitable for archeological and materials science investigations. Fragmented samples were mounted using standard holders supplied with the instrument and measured under vacuum conditions. The quantitative analysis was performed using manufacturer-established calibration procedures routinely applied for elemental analysis of inorganic materials.

2.3. Characterization of Glass–Lead Interface

2.3.1. Scanning Electron Microscopy and Energy-Dispersive X-Ray Spectroscopy (SEM- EDS)

The study utilized a scanning electron microscope (SEM) to investigate the morphology and surface characteristics of various materials. A high-resolution SEM (JSM-IT800; JEOL Ltd., Tokyo, Japan), was employed to characterize the interface of the ancient Chu mirror, with an integrated Energy Dispersive Spectroscopy (EDS) system used to perform X-ray line scans of the lead–glass interface. Additionally, a lower-resolution SEM (JSM IT300) was used to examine the cross-section of the alternative Chu sample.

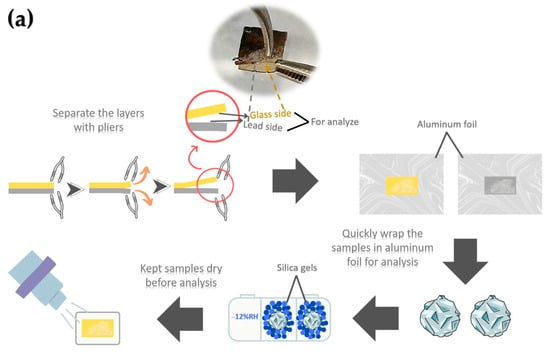

2.3.2. X-Ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS)

The ancient Chu mosaic mirror was analyzed using X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS) to determine the chemical composition of the sample’s surface. The analysis was conducted with an XPS instrument (AXIS ULTRA DLD, Kratos Analytical, Manchester, UK) under a base pressure of approximately 1.7 × 10−9 torr in the analysis chamber. Sample excitation was performed in X-ray hybrid mode with a spot area of 700 × 300 µm, using monochromatic Al Kα1,2 radiation at 1.4 keV. The X-ray anode was operated at 15 kV, 10 mA, and 150 W. Photoelectrons were detected with a hemispherical analyzer positioned at a 90° angle relative to the sample surface. Ion sputtering was conducted with Ar+ ions at 4 keV for 30 s, targeting a 2.5 × 2.5 mm area of corrosion. The sample holder, made of stainless steel, allows multiple samples to be mounted simultaneously using conductive carbon tape, enabling efficient parallel analysis.

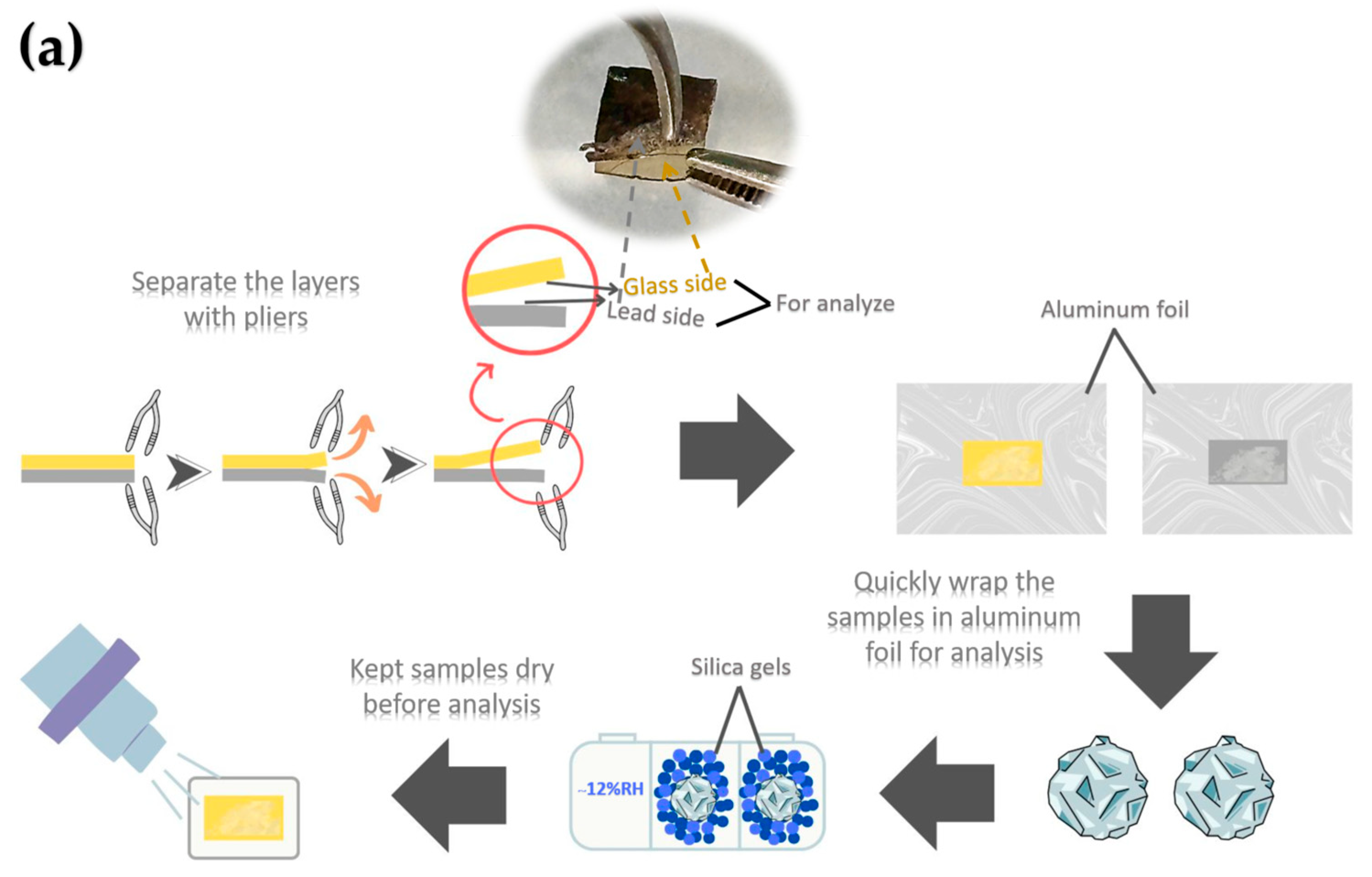

The spectra were calibrated using the C 1s peak (binding energy = 285 eV) and analyzed with VISION II software (Version: 2.2.6) from Kratos Analytical Co., Ltd. For XPS analysis, samples were prepared by cutting specimens into sizes ranging from 2 mm to 2 cm in diameter. The thin glass and metal layers were separated using pliers with moderate applied force, and the pieces were carefully placed onto aluminum foil. The foil-wrapped samples were promptly transferred to a sealed container filled with silica gel to minimize moisture absorption. The samples were transferred to the vacuum chamber as quickly as possible for analysis. A schematic diagram of the sample preparation procedure is shown in Figure 6a. Figure 6b presents photographs of the peeled surfaces, showing no visible residual lead on the glass side for either the ancient or alternative mirror samples. Additionally, no noticeable elongation or deformation of the lead substrate was observed during the separation process.

Figure 6.

Schematic diagram illustrating XPS sample preparation at the glass–lead interface (a) and photographs of peeled glass-side and lead-side samples (b). The samples shown were not those used for XPS analysis and are presented solely to illustrate the appearance of the peeled surfaces.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Chemical Analysis of Yellow Glass Layers

The key components in the yellow glass layers of chosen Chu and Kriab samples, such as silicon (Si), lead (Pb), calcium (Ca), potassium (K), and aluminum (Al), were also examined through portable X-ray fluorescence (PXRF), as detailed in Table 2. Due to the limitations of the PXRF device, detection of sodium (Na) and other light elements, such as boron (B), was not feasible. Additional minor elements were identified, showing differences in both type and concentration.

Table 2.

Elemental composition (wt%) of “gold glass” Kriab and Chu mirrors analyzed from the yellow glass surface using portable X-ray fluorescence (pXRF). The data represent “gold glass” samples from Thailand and Indonesia, excluding colorless samples from Pakistan. Included for comparison are a lead-coated glass-on-fur sample presumed to originate from Pakistan and golden mirrors decorated on Tapis from Lampung, Sumatra, Indonesia. The estimated ages of the Indonesian and Pakistani samples are approximately 100 years.

In the pXRF analysis, LE% represents light elements, predominantly oxygen within the silicate–lead matrix, calculated using the fundamental parameters (FP) method. Elevated LE values are therefore expected in high-lead glass systems as a direct consequence of stoichiometry. To ensure the reliability of the compositional data, the pXRF results were cross-validated with WD-XRF and XPS measurements. The strong agreement among these techniques for major oxides, such as PbO, confirms that the pXRF data reliably capture the compositional trends observed in the ancient artifacts.

Iron (Fe) and manganese (Mn) are minor elements that significantly influence the yellow hue of glass layers. Conventionally, oxidized Fe3+ ions are thought to contribute to a pale-yellow color, whereas reduced Fe2+ ions are thought to give a blue–green color [7]. Figure 3 illustrates that, in spite of a high lead level, the deepest yellow hue was not seen in the sample SoKhla15, which had the greatest Fe concentration. This discrepancy may be due to a low concentration of Mn.

The yellow coloration of glass is significantly influenced by the redox conditions present during the glass-melting process and within the furnace, which affect the retention of Fe3+ ions that contribute to this hue. Moreover, Mn4+ and Mn3+ function as oxidizing agents within the glass melt, promoting the oxidation of Fe2+ to Fe3+. The incorporation of suitable quantities of MnO2 into the glass melt can effectively regulate the yellow coloration. Generation after generation of glassmakers have inherited this complex understanding of redox regulation and the function of Mn.

Table 3 presents the chemical composition (wt%) of the “gold glass” layers from Chu and Kriab mirrors, analyzed using the WD-XRF technique on the yellow glass surface. The historical age of the samples was determined based on treatment histories, comprehensive examination data from the Fine Arts Department, and relevant archival documents. While the Kriab and Chu samples are broadly dated to the 18th–20th centuries, the precise age of these mirrors remains inconclusive.

Table 3.

Chemical composition (wt%) of “gold glass” Kriab and Chu mirrors analyzed from the yellow glass surface using the WD-XRF technique.

Copper was detected in varying amounts across the samples using both pXRF and WD-XRF, as shown in Table 2 and Table 3, respectively. Notably higher concentrations were observed in the yellow sample PheRi3 and the green sample PheRi4 (Table 3). In contrast, the colorless Pakistani samples—which have lower PbO content compared to the others—showed no detectable Cu in the pXRF analysis (Table 2). This observation is consistent with previous studies by Wedepohl et al. [39] and Eggert and Hillebrecht [40], which report that high-lead glasses containing approximately 70 wt% PbO commonly incorporate copper as a minor constituent.

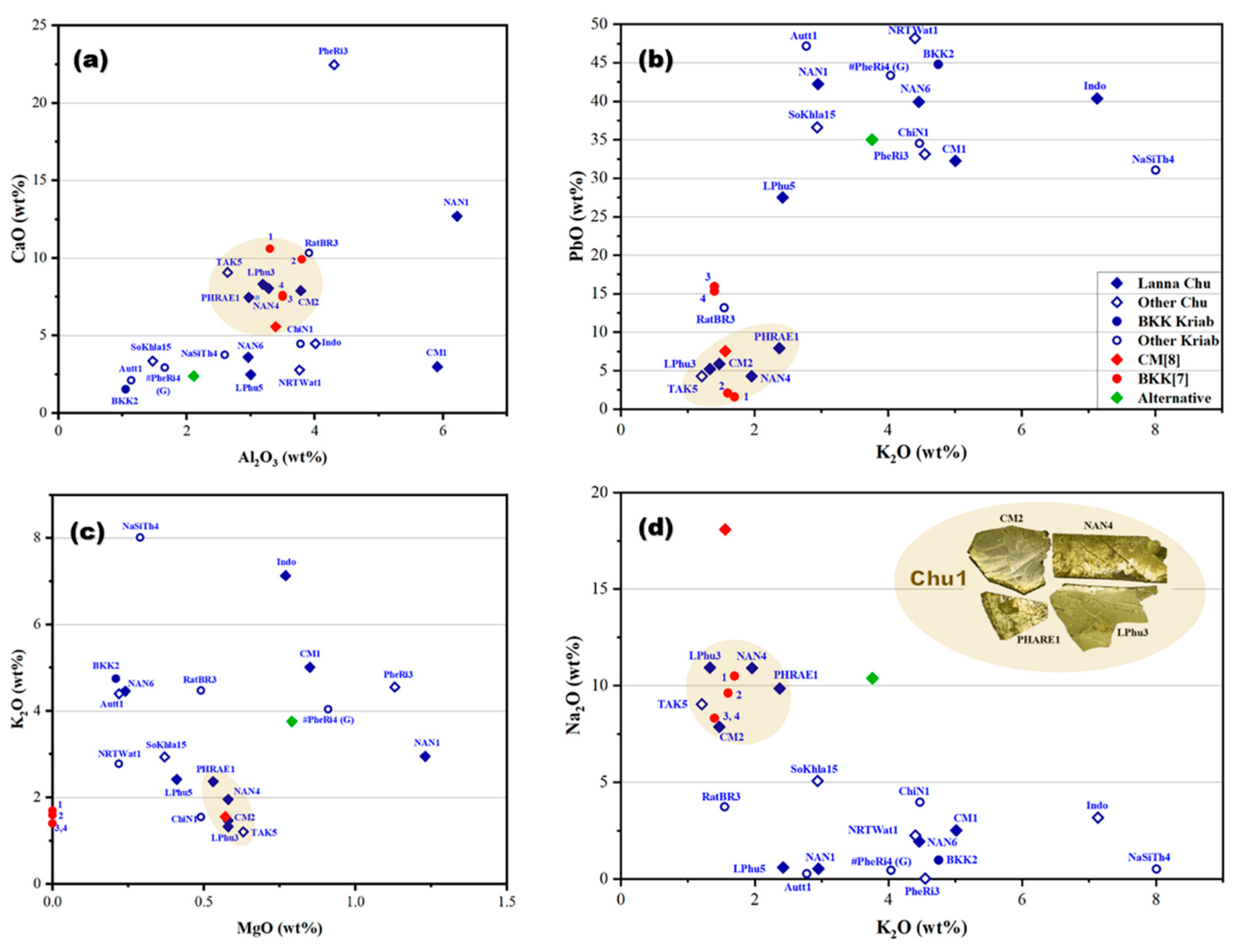

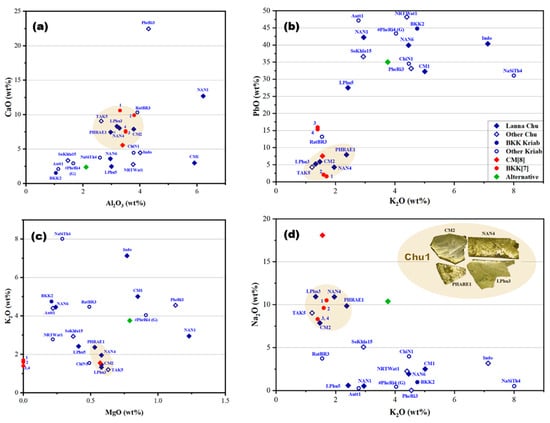

By examining the weight proportions of major and minor composition, including Al2O3, CaO, PbO, Na2O, K2O, and MgO, in the yellow glass layers, a deeper understanding of their material composition was obtained, as illustrated in Figure 7. Previous findings on the yellow glass of Kriab [7] and Chu [8], gathered from various sources, were also plotted, providing insights into the origins of the raw materials and their connections to historical glass production practices.

Figure 7.

The oxide composition relationships in the yellow glass layers of “gold glass” from Kriab and Chu mirror samples, collected from various locations investigated in this project, were compared with data from related studies [7,8]. These studies included analyses of alternative Chu samples and a 300-year-old green Kriab sample (#PheRi4). Four types of compositional relationships were examined through graphical representations: (a) CaO-Al2O3, (b) PbO-K2O, (c) K2O-MgO, and (d) Na2O-K2O.

The findings revealed that the glass compositions employed in the manufacture of these mirrors were primarily lead–silicate-based, as established by the WD-XRF analysis. The lead oxide (PbO) concentration in the lead–silicate glass samples exhibited considerable variation, spanning from 4.28% to 48.17% by weight. This wide variation suggests the intentional use of distinct glass formulations, likely reflecting proprietary recipes or specific production traditions of different artisan workshops.

The yellow glass of the mirror samples is primarily composed of silica, the main raw material for glass production, as demonstrated in the CaO-Al2O3 relationship graph (Figure 7a). This plot is typically used to trace the provenance of the silica source used in producing the yellow glass layer of the examined mirrors. The data reveal that most of the glass samples utilized silica with a wide distribution of CaO (2–12 wt%) and Al2O3 (1–4.2 wt%). A few samples, including PheRi3, NAN1, and CM1, deviate from the main group.

Interestingly, a significant cluster of Kriab and Chu samples aligns within the same group, specifically encompassing CaO concentrations of 5–12 wt% and Al2O3 concentrations of 2.5–4.2 wt%. This may suggest a shared silica source; however, further investigation of trace elements would be necessary to confirm this hypothesis. In contrast, the PbO-K2O relationship (Figure 7b) indicates some divergence among the samples, with only the main Chu Lanna and certain Kriab BKK[7] samples remaining in the group. These samples are characterized by low PbO levels, not exceeding 10 wt%.

The other two relationships, K2O-MgO and Na2O-K2O (Figure 7c,d), further support the distinct clustering of the Chu1 group. Notably, the K2O-MgO plot suggests the use of wood ash from a consistent provenance. The inset of the Chu1 samples highlights their morphology, confirming that all originate from the Lanna area. TAK5, however, is excluded from the group due to its distinct morphology, which differs significantly from the others and will be discussed further. Additionally, CM[8], previously reported as “gold glass” Chu from the Lanna region, also aligns within the Chu1 group.

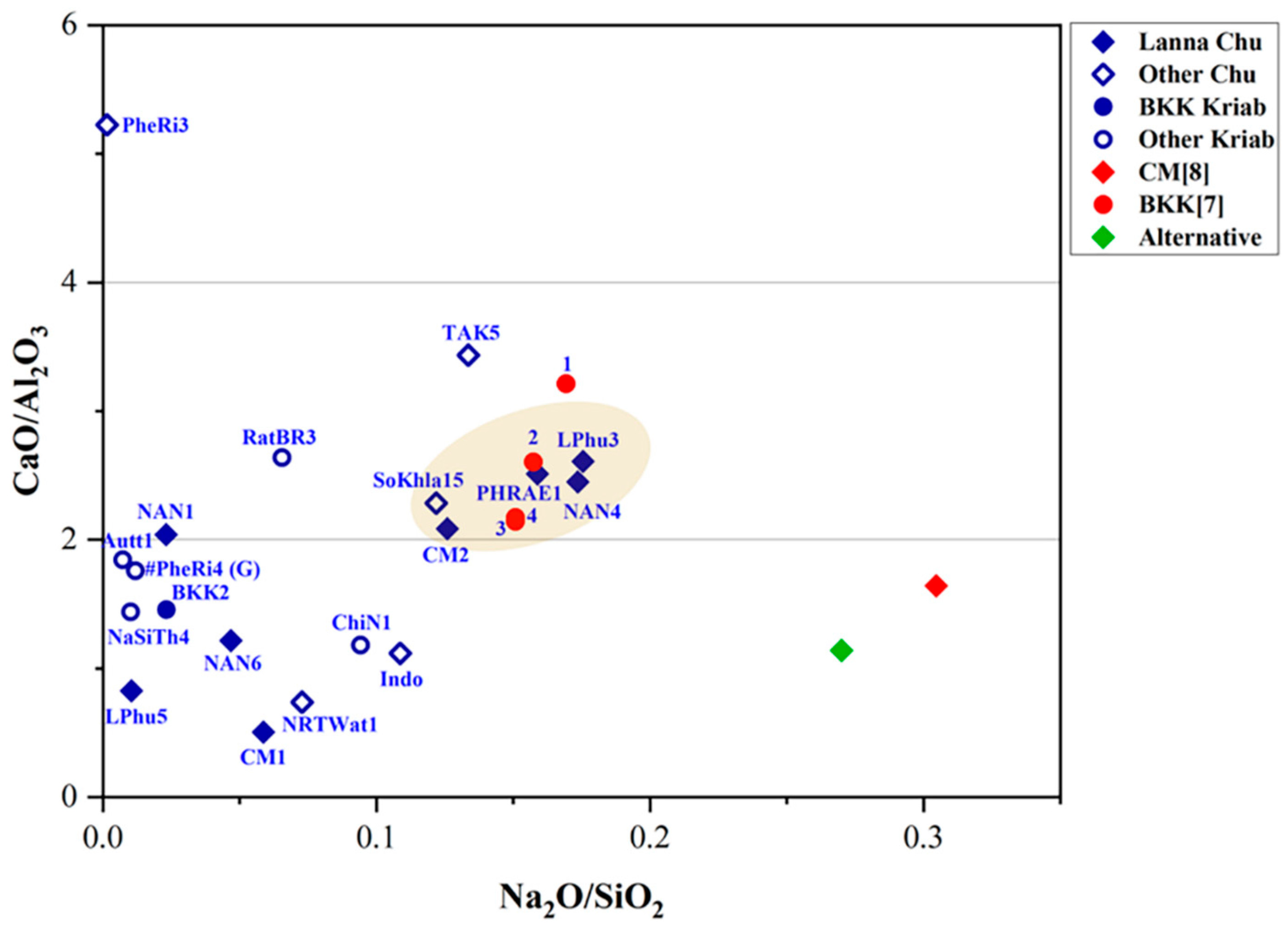

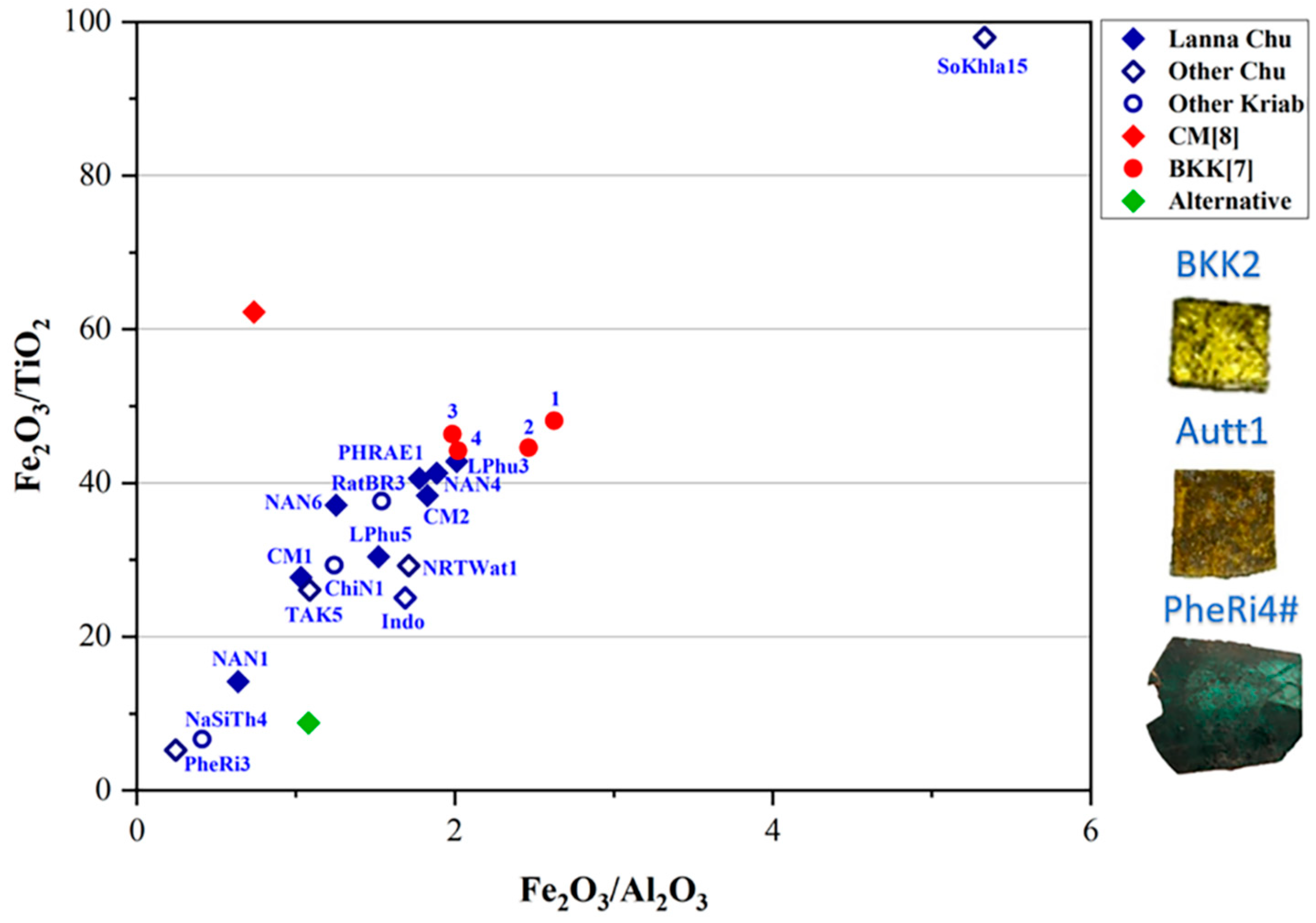

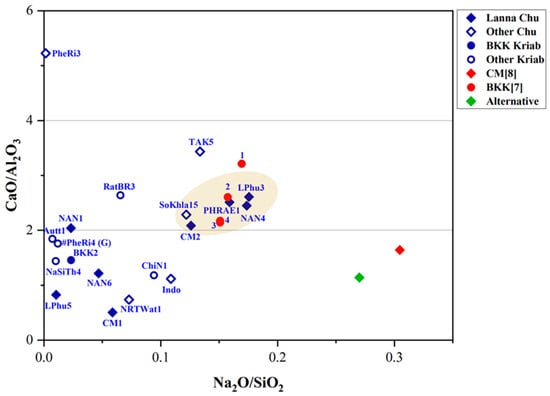

It is important to note that three fundamental components are required to produce glass: calcium, silica, and an alkaline flux. Common sources of alkaline flux include wood ash, plant ash, and natron. Silica is typically derived from sand, while calcium is obtained from shell fragments within the sand or from calcium compounds present in plant or wood ash. For high-lead glasses, analyzing the ratios of minor impurities, such as Fe2O3 and TiO2, typically found in silica sand, alongside the primary components SiO2, Al2O3, and CaO, provides an alternative and equally valid method for investigating provenance. This approach is illustrated in Figure 8 and Figure 9 and offers valuable insights into their origins [41].

Figure 8.

A plot of CaO/Al2O3 and Na2O/SiO2 in the yellow glass layers of “gold glass” from Kriab and Chu mirror samples.

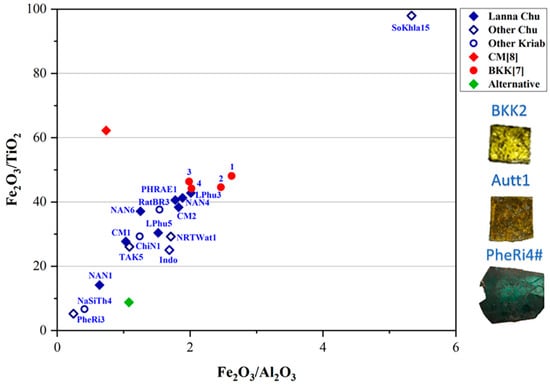

Figure 9.

A plot of Fe2O3/TiO2 and Fe2O3/Al2O3 in the yellow glass layers of “gold glass” from Kriab and Chu mirror samples.

As shown in Figure 8, TAK5 deviates from the Chu1 group due to its higher concentrations of CaO and Na2O compared to the other samples. This variation suggests that TAK5 may represent a recycled material. Another potential instance of recycling is BKK[7] sample 1, which slightly deviates from the group of Kriab samples (BKK[7] 2–4) collected from the Temple of the Emerald Buddha in Bangkok. Although Chu1 and BKK[7] may share a similar source of silica, differences in the flux source, particularly the potash source (Figure 7c), further distinguish them. Notably, all BKK[7] samples lack detectable amounts of MgO, separating them into a distinct group based on flux composition. However, further investigation using additional trace element analysis is necessary to confirm this hypothesis in future research.

Utilizing Ti impurities in the silica source, a plot of Fe2O3/TiO2 and Fe2O3/Al2O3 ratios (Figure 9) might point to a shared provenance of silica between the Chu1 group and BKK[7] Kriab samples, particularly for samples with a low Fe2O3 content (samples 3 and 4). In contrast, BKK[7] samples 1 and 2 exhibit the highest Fe2O3 content, likely due to intentional additions aimed at enhancing the yellow hue of the glass. Other notable deviations are observed in alternative materials, such as the alternative Chu mirror sample, which used modern, commercial-grade sand as a raw material. Additionally, variation may also arise from the use of different analytical techniques. For example, CM[8] reported the composition of Chu glass using SEM-EDS and PIXE based on a sample collected from a temple in Chiang Mai province, referencing data from previous studies.

Other ancient samples, including BKK2, Autt1, and the oldest sample in this study, PheRi4# (all Kriab), are excluded from this plot due to the absence of detectable TiO2. These Kriab samples may share the same provenance or have been produced using similar technology. However, based on the K2O and MgO plot in Figure 7c, BKK2 and Autt1 are closely grouped, while PheRi4# is distinct, characterized by a higher concentration of MgO compared to the other two Kriab samples. This observation aligns well with the dating of PheRi4#, which is the oldest sample, from the late Ayutthaya period. In contrast, BKK2 and Autt1 date to the early Rattanakosin period, approximately 140 years later.

Interestingly, the physical appearances of Autt1 and BKK2 differ significantly. Autt1 exhibits a darker surface, which may be attributed to a small amount of Cd detected in this sample, as shown by the pXRF results in Table 2. Alternatively, the dark appearance could result from corrosion caused by prolonged flooding, as the Kriab mirror containing Autt1 was recovered from a temple in Ayutthaya that had experienced severe flooding.

The Chu1 group predominantly dates to the 20th century, with the exception of CM2, which is dated to approximately the 19th century. This finding is particularly significant when compared to the BKK[7] samples, which are dated to the 19th century, possibly during the major restoration under King Rama II. It is plausible that either sand or raw glass from the same provenance was used in their production.

Most of the yellow glass layers we observed belong to the group of mixed lead–alkaline glass or wood-ash lead glass, based on analysis and comparison with other ancient glass compositions [19,34]. This type of glass was initially produced in Eastern Europe during the 13th century. However, its origin remains uncertain, as glass with a similar composition has also been discovered in Thailand from the 18th to 20th centuries, several centuries after its first known production.

Although evidence of the Royal glass workshops primarily exists in old records, no detailed information about glass kilns or raw glass production has been preserved. It can be hypothesized that much of the Kriab glass found in central Thailand during the Early Rattanakosin era (around the 19th century) may have been produced in the Royal glass workshops, even though strong evidence to confirm this remains lacking. Chu1, which shares the same silica source as BKK[7], could potentially have some connection to the Royal glass workshops. However, the wood ash flux appears to have originated from a different source, and the physical characteristics of Kriab and Chu glass are notably different.

It is likely that glass craftsmen of this period employed similar technologies and glass recipes but operated independent workshops, leading to the development of unique and innovative techniques for producing a diverse range of glass mirrors. To explore this concept further, additional research involving trace element analysis, lead isotope analysis, and extensive archeological evidence is necessary.

3.2. Microstructural Analysis at the Glass–Lead Interface

The lead backing of the examined “golden mirrors” consists predominantly of high-purity lead. For example, a WDS analysis at three points on sample NAN1 yielded 98.42 wt% Pb and 1.58 wt% O, indicating the use of exceptionally pure lead by ancient artisans. This choice is significant, as pure lead is a relatively soft metal, and even minor impurities can increase its hardness. Accordingly, high-purity lead was also employed for the preparation of the alternative Chu mirrors in this study. The specifications of the lead-coating material are provided in Table S3 (Supplementary Information).

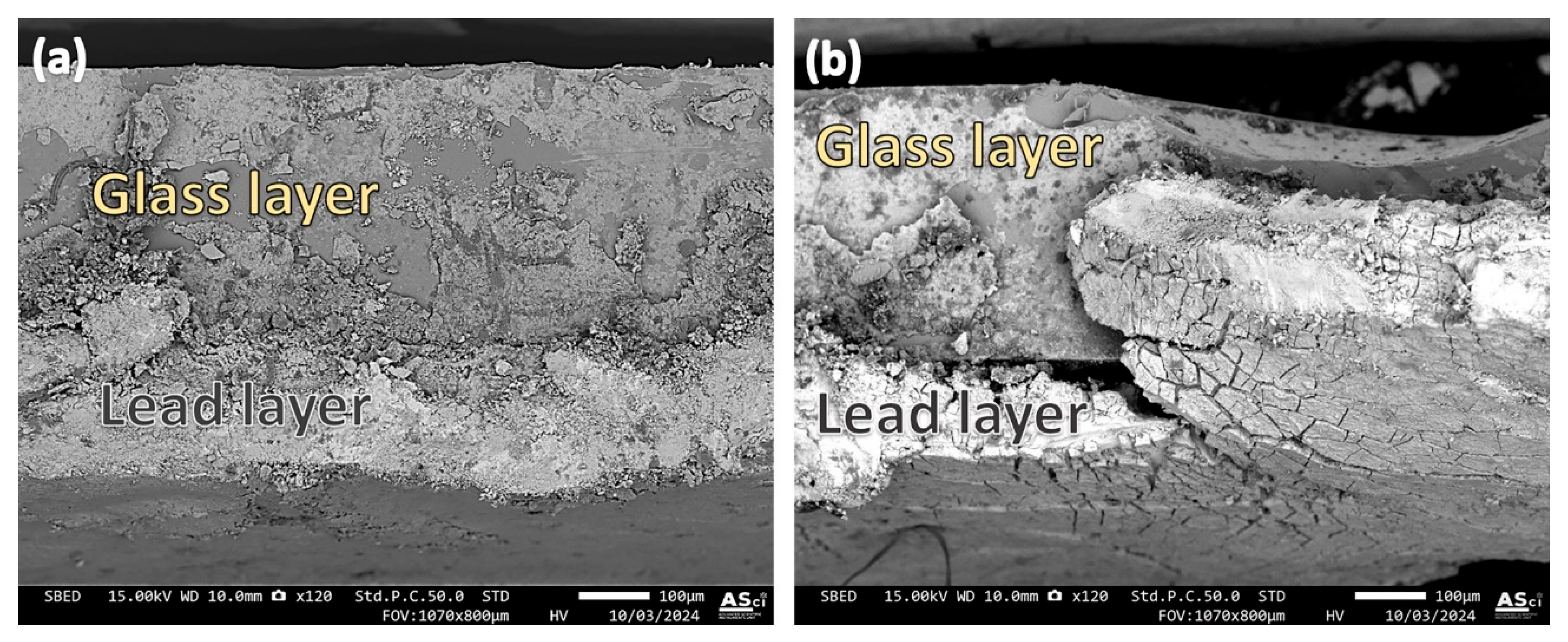

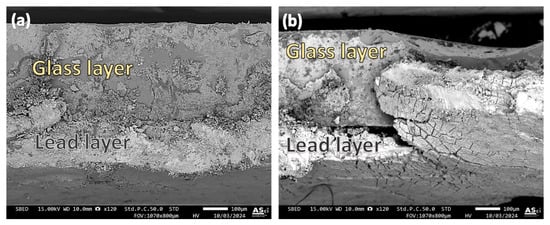

The cross-sectional examination of the ancient Chu mirror (CM1) at the lead–glass interface was performed using a scanning electron microscope (SEM) equipped with a backscattered electron detector. Micrographs of two fracture areas from the same sample are shown in Figure 10a,b. The sample was cut with scissors, and the splice in Figure 10a appears straight, with no visible separation between the glass and lead. However, signs of heterogeneity in the glass matrix, evident throughout the examined areas, may have been caused by a residual lead substrate introduced during scissor cutting or by intrinsic heterogeneity in the glass matrix itself. To address this issue, proper polishing and careful sample preparation should be employed in future investigations.

Figure 10.

Micrographs illustrating the interface between the glass and lead layer in the ancient Chu sample (CM1). Different observation areas are shown in (a,b).

In contrast, the area shown in Figure 10b revealed regions where separation between the glass and lead occurred. Uneven bonding of the lead was also observed, with some sections tearing off while others remained securely adhered, even to the extent that the scissors cut through them. This uneven adhesion between the lead and glass may be attributed to the glass coating process used by ancient craftsmen, who likely encountered challenges in controlling the factors necessary for achieving a uniform coating across the entire glass sheet. Variations in heat application or the presence of contaminants, such as dirt or newly formed oxide layers on the glass surface, could have contributed to these irregularities in adhesion.

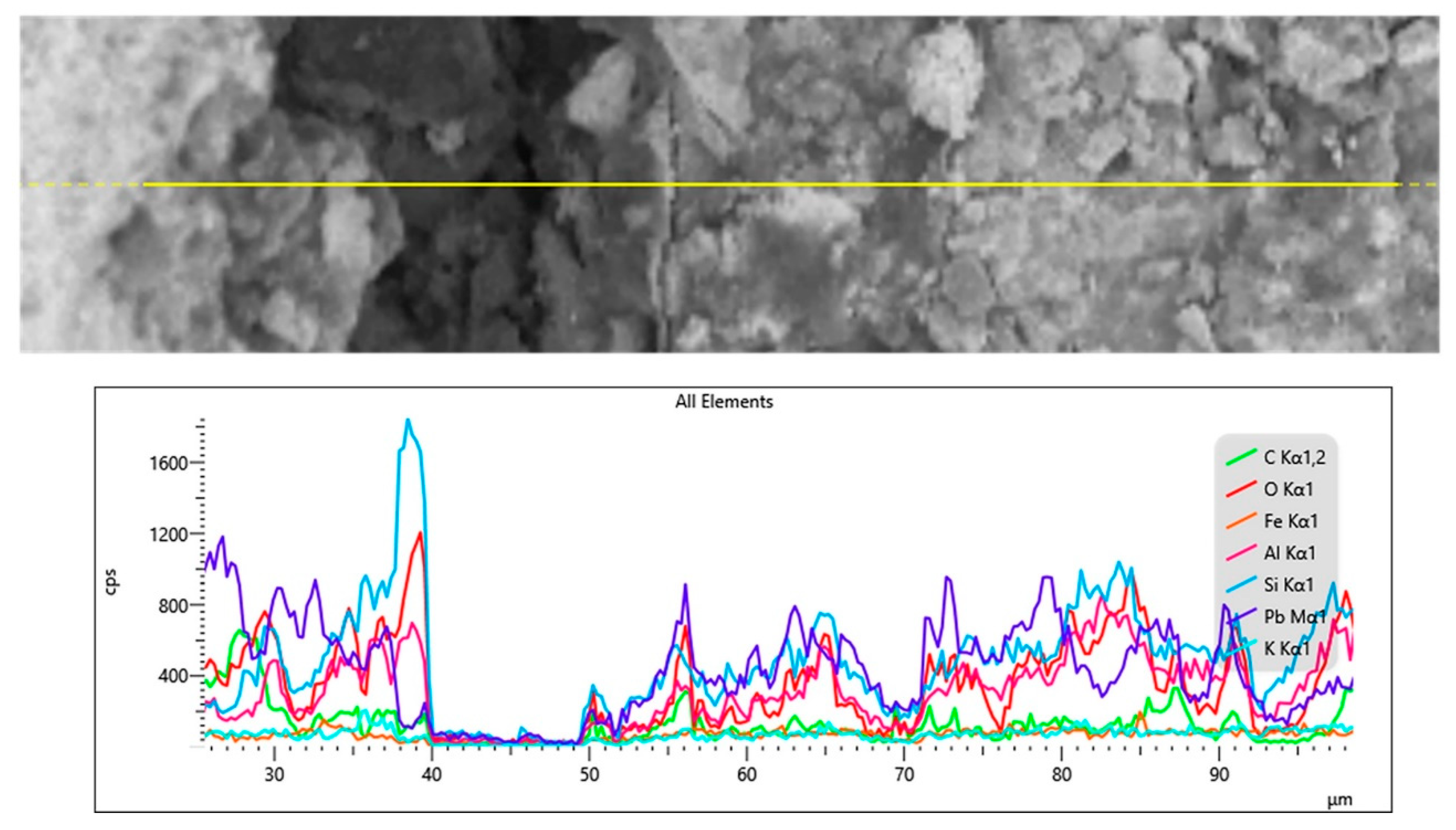

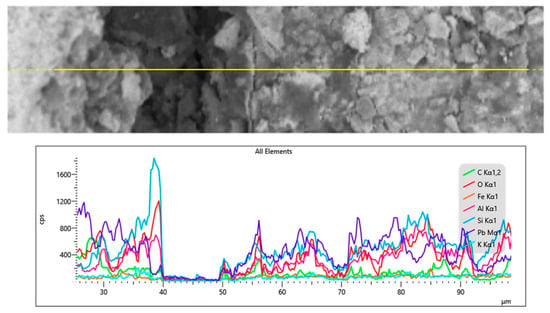

To preliminarily examine the chemical characteristics of the interface in the Chu mirror sample, an X-ray line scan was conducted, and the results are shown in Figure 11. Despite the use of high-resolution SEM, distinguishing the size of the interface layer proved challenging. The drop in the signal observed around 40–50 µm appears to be caused by a microcrack. Further analysis using XPS was performed on the same sample, as will be discussed in the next section.

Figure 11.

X-ray line scan at the interface between the glass and lead layer in the ancient Chu sample (CM1).

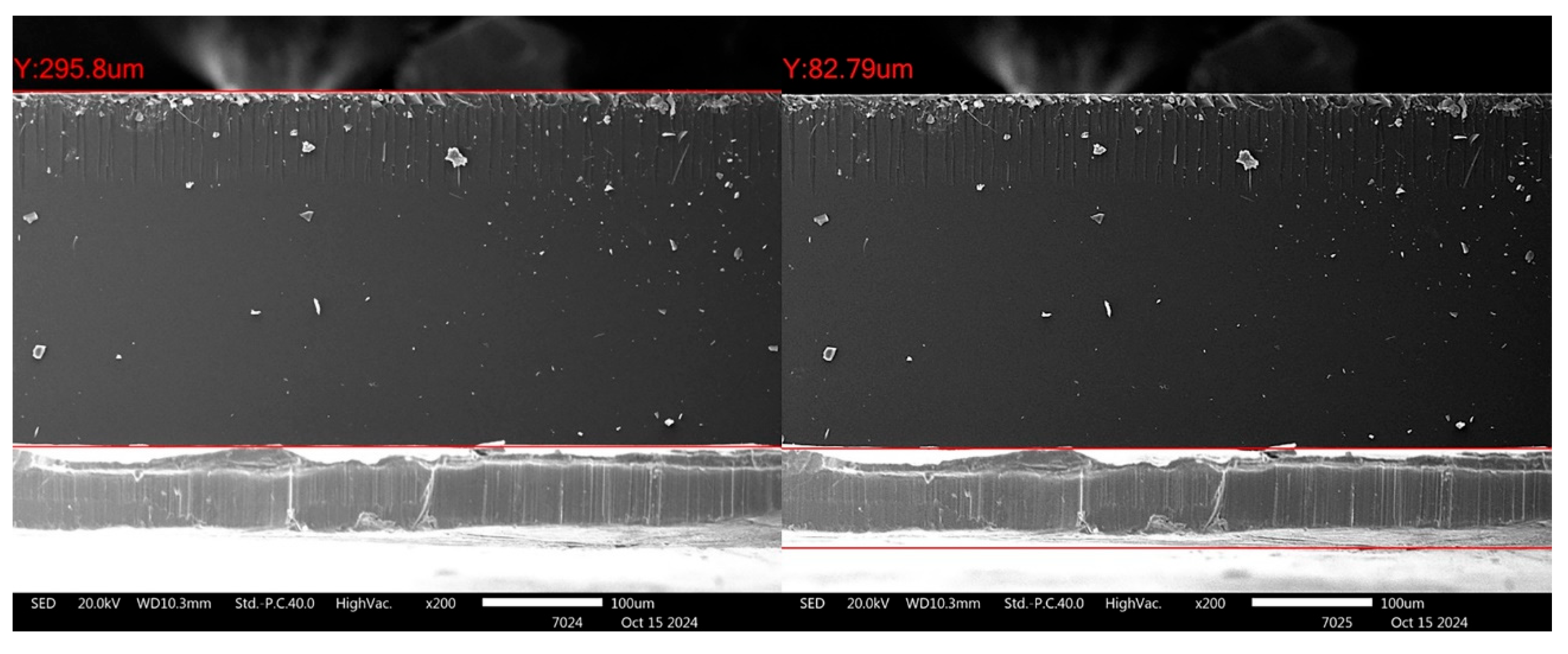

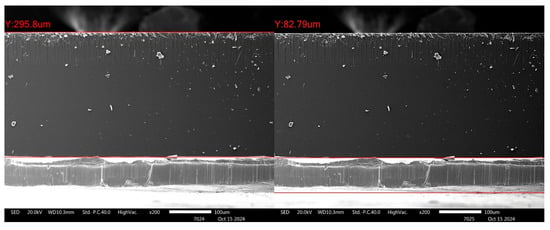

Figure 12 shows an example of the cross-section of the alternative Chu sample (1.6 wt% B2O3). The scissor-cutting technique was used for sample preparation without subsequent polishing. The interface appears smooth and straight, with some evidence of cracks at the interface, suggesting that the adhesion between the glass and lead layers is quite robust. Using in-house image analysis software integrated with the SEM (JSM-IT800), the thickness of the glass layer and lead layer was measured to be approximately 295.8 µm and 82.79 µm, respectively. This indicates that with a well-controlled coating technique, strong adhesion between the glass and lead layers can be achieved.

Figure 12.

Micrographs illustrating the interface between the glass and lead layer in the alternative Chu sample.

3.3. Depth Profile Analysis of Glass and Lead Interfacial Surfaces by XPS

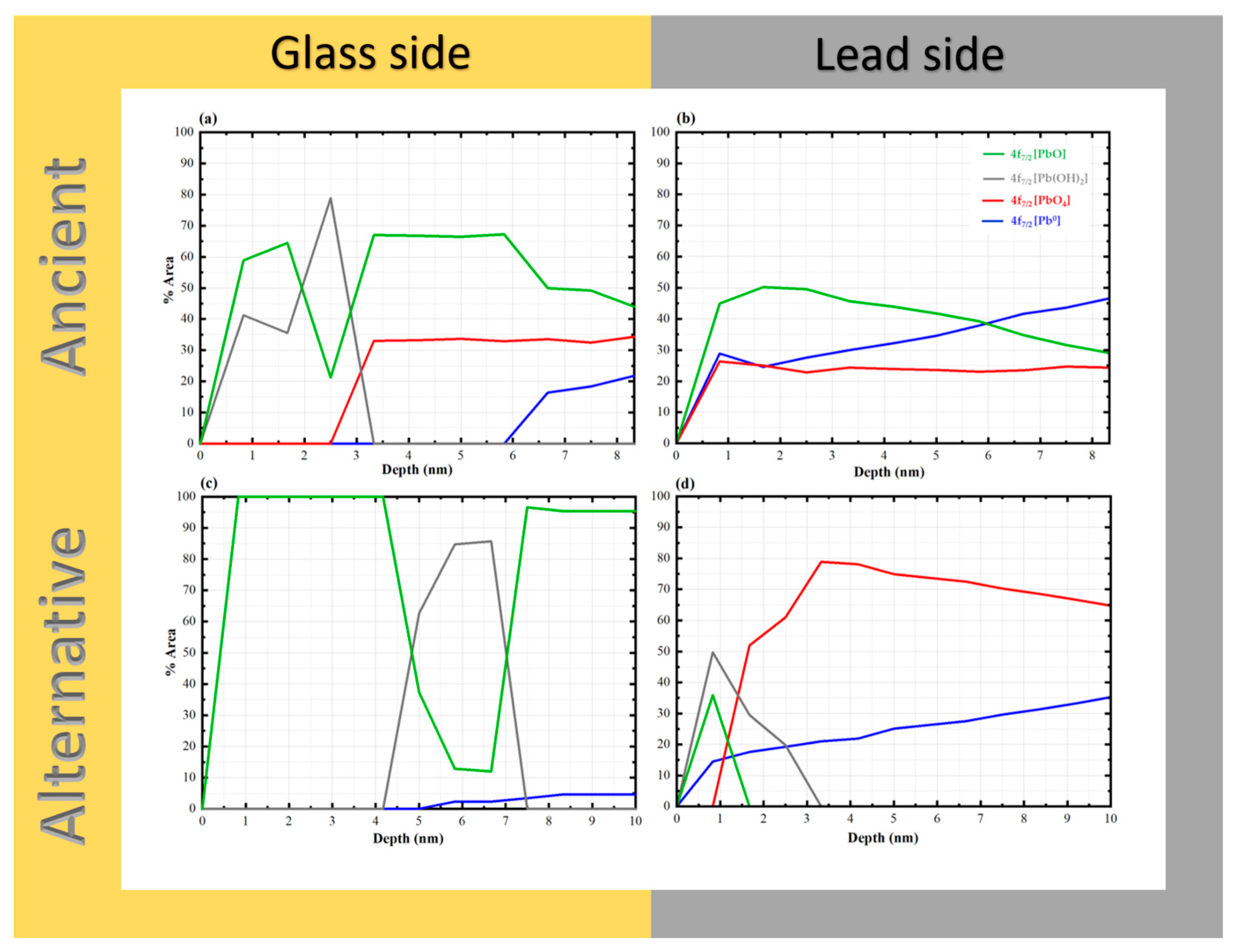

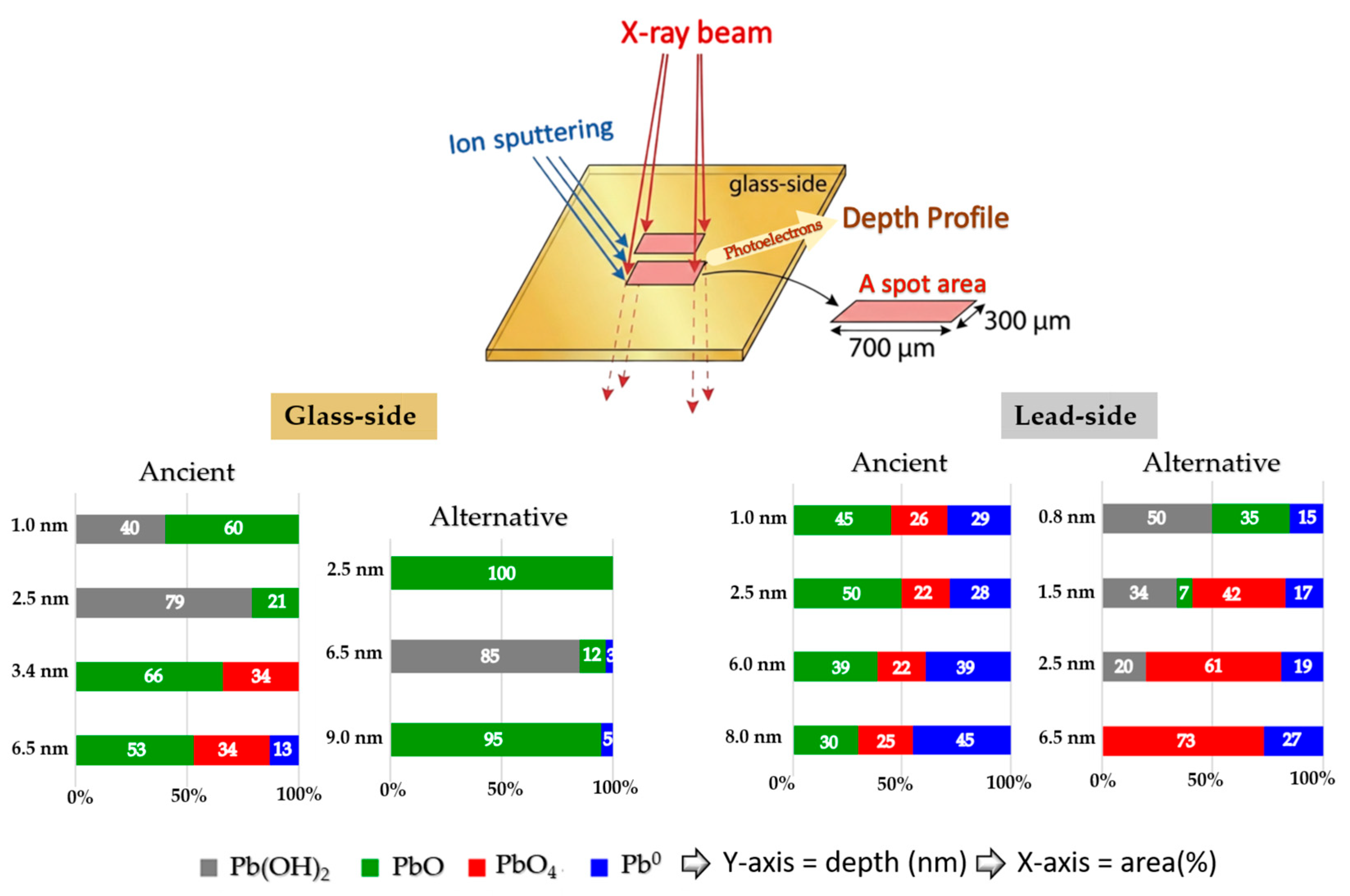

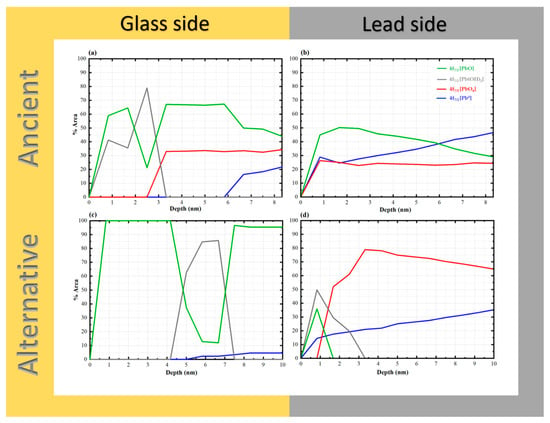

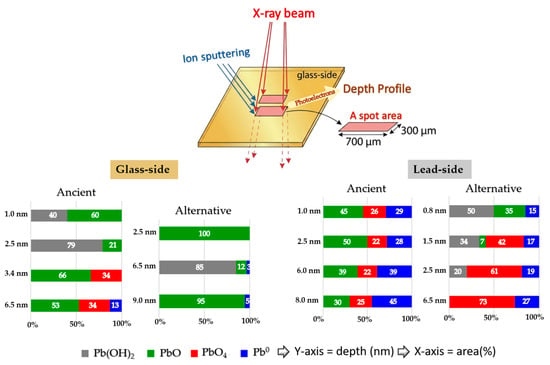

To investigate the lead–glass interface in Chu mirror samples, both ancient and alternative Chu mirrors were analyzed using X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS). The interface characteristics and depth-profiling results are shown in Figure 13. A schematic diagram illustrating the principle of ion sputtering and photoelectron emission during depth profiling is provided in Figure 14.

Figure 13.

XPS depth profiles of “gold glass” Chu mirrors: (a) glass side of the ancient sample (CM1), (b) lead side of the ancient sample, (c) glass side of the alternative sample, and (d) lead side of the alternative sample.

Figure 14.

Schematic diagram illustrating XPS depth profiling and the relationship between selected sputtering depth and the relative area (%) of Pb 4f7/2 species detected from the glass side and lead side of both ancient and alternative Chu samples.

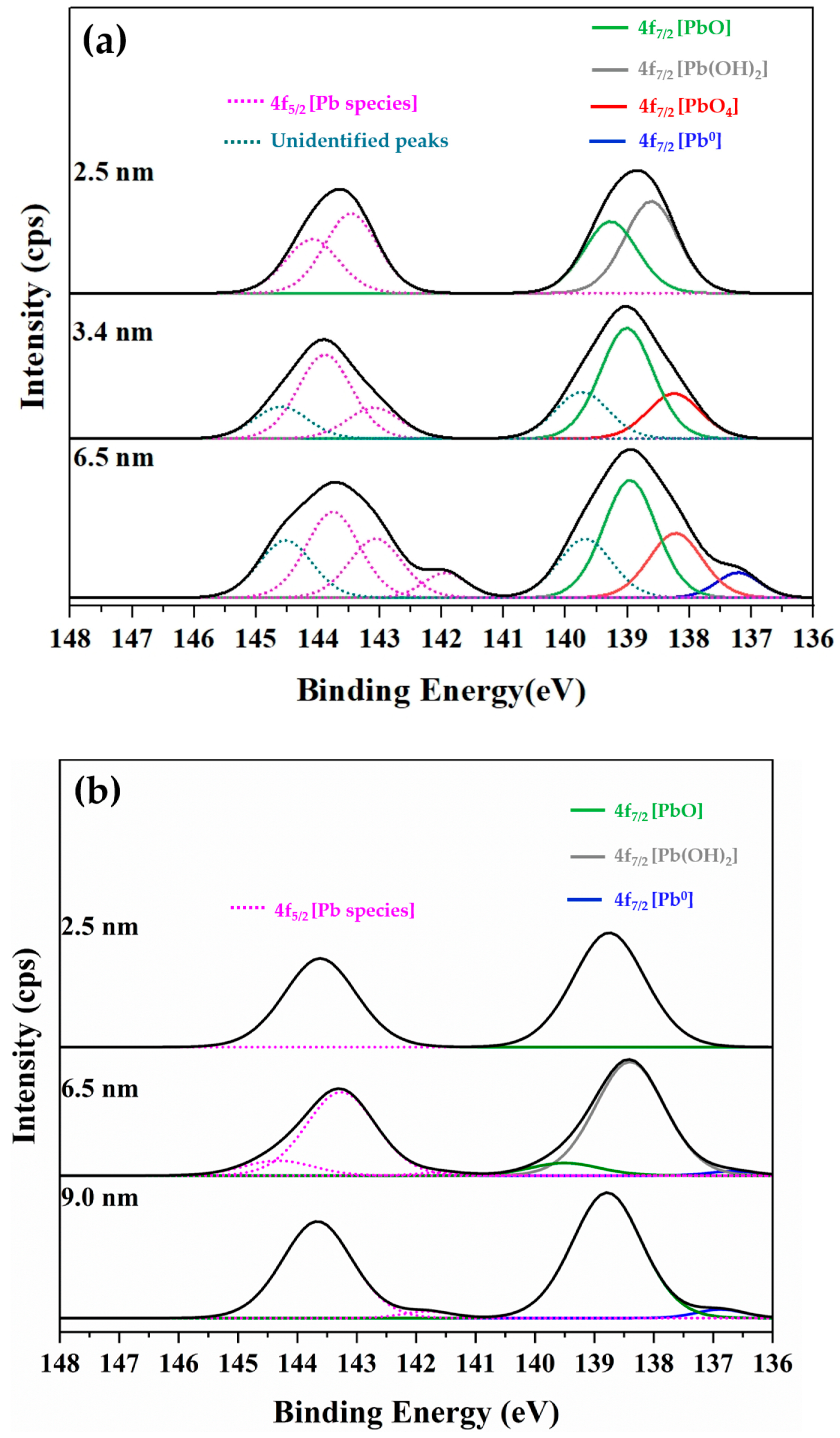

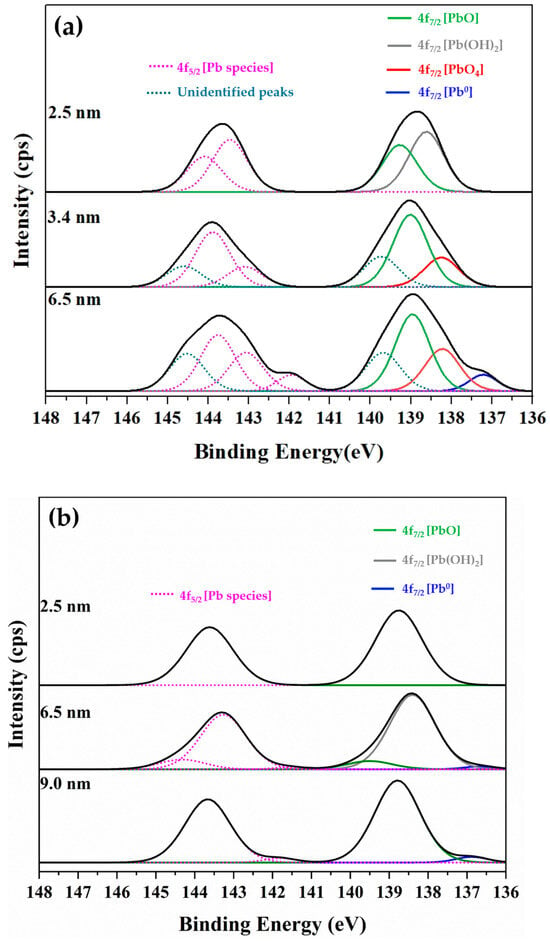

During the analysis, a spot area of 300 × 700 μm was exposed to the incident X-ray beam. Variations in the Pb 4f7/2 photoelectron signal were monitored as a function of sputtering depth, and the relationships between analyzed depth and relative area percentage are presented for both the glass-side and the lead-side of ancient and alternative Chu samples. Representative XPS spectra from the glass side of both ancient (Figure 15a) and alternative Chu samples (Figure 15b) are also shown to confirm the presence of the detected species. The binding energies of Pb 4f7/2 photoelectrons, summarized in Table 4, provide insight into the chemical state of lead from the surface down to an examined depth of approximately 10 nm.

Figure 15.

Representative XPS Pb 4f spectra obtained from the glass side of (a) ancient Chu and (b) alternative Chu mirror samples, showing the detected Pb 4f7/2 photoelectron species used to evaluate the chemical states of lead at the glass–lead interface.

Table 4.

Binding energies of Pb 4f7/2 peaks corresponding to different chemical states on the thin yellow glass and lead sides of the analyzed Chu mirror samples.

Binding energies in the range of 138.2–137.8 correspond to PbO4 units or pyramidal structures forming polymer chains within the SiO4 network. Peaks at 139.4–138.6 eV are attributed to PbO or PbO2 species, which are commonly associated with high-lead silicate glass [42,43]. The intermediate binding energies between 138.8 and 138.2 eV are assigned to Pb(OH)2 or other hydrated species, such as hydrocerussite (Pb3(OH)2(CO3)2); however, definitive identification of the carbonate phase would require supporting analysis from the O 1s and C 1s spectra. Finally, spectral features appearing in the range of 137.0–136.3 eV are associated with metallic lead (Pb0).

Notably, additional unidentified peaks near 139.7 eV (Pb 4f7/2) and 144.6 eV (Pb 4f5/2) were detected at sputtering depths of 3.4 and 6.5 nm exclusively on the glass side of the ancient samples. These anomalous features were entirely absent in the alternative Chu reproductions. Their absence in modern samples supports the interpretation that these peaks arise from localized surface charging or specific hydroxyl environments associated with moisture infiltration through age-related microcracks. Consequently, these unidentified features were excluded from quantitative analysis to ensure the accuracy and reliability of stoichiometric calculations for the primary lead species.

As shown in Figure 13, PbO species were observed from the start of the surface analysis in all samples. The phenomenon can be attributed to hot lead coating, which causes lead atoms to diffuse into the glass surface to a certain depth, subsequently oxidizing with air to form PbO. Both the glass sides of the ancient and alternative Chu samples contained significant amounts of PbO up to a depth of 10 nm. On the opposite lead side of the ancient Chu sample, a similarly high amount of PbO was observed, comparable to its glass-side counterpart. However, in the alternative Chu sample, the lead side showed a shallow penetration depth of approximately 1.6 nm, with no detectable presence of PbO beyond this depth.

These results suggest that interfacial PbO species may occur in two distinct structural configurations: well-defined crystalline lattices and disordered, chain-like Pb–O–Pb linkages. The latter configuration is characteristic of lead acting as a conditional network former within the silicate glass matrix [44]. Such polymeric chains provide the structural flexibility required to bridge the metallic lead coating (Pb0) and the rigid silicate network of the glass substrate. This interfacial bonding mechanism, mediated by disordered Pb–O chains, effectively accommodates interfacial strain arising from thermal expansion mismatch between the two materials [45], thereby contributing to the long-term adhesion observed in artifacts exceeding a century in age.

In the case of the alternative Chu reproductions, PbO remains the dominant species throughout the observed depth (10 nm), with the exception of a localized sub-surface zone. Specifically, Pb(OH)2 was found to pre-dominate at a depth of approximately 4.2 nm, extending across a 3.4 nm wide reaction zone. While initially attributed solely to a Pb(OH)2 interfacial layer, this spectral feature may more broadly indicate the early-stage formation of basic lead carbonates, such as hydrocerussite (Pb3(OH)2(CO3)2). Hydrocerussite is a common corrosion product resulting from the reaction of lead species with atmospheric moisture and carbon dioxide during the coating process. A similar hydroxide-rich zone was also observed in the ancient samples; however, its spatial distribution differed, occurring at the immediate surface and reaching its maximum concentration at around 2.5 nm.

Mechanistically, the fixation of these lead species is not only atmospheric but likely mediated by the glass substrate itself. According to previous studies [46], silica glass surfaces facilitate the formation of silanol (Si–OH) linkages in the form of both hydrogen-bonded and free silanol groups. The latter are highly reactive and serve as primary adsorption sites for lead species. The density and chemical characteristics of these silanol groups are governed by complex interfacial factors, including processing temperatures, the presence of impurities, and structural defects inherent to the glass surface. Our depth-profiling analysis further supports this model, showing that PbO species remain dominant within the interfacial region up to a depth of approximately 6 nm on the glass side of ancient samples, followed by a sharp attenuation at greater depths. This spatial distribution reinforces the presence of a well-defined interfacial reaction zone primarily governed by PbO bonding, upon which secondary atmospheric reactions (like hydrocerussite formation) may occur.

The PbO4 species, corresponding to fourfold-coordinated lead in the form of PbO4 pyramidal units, were clearly identified in this study. Previous work has shown that when the PbO content in PbO–SiO2 systems exceeds approximately 40 wt%, these PbO4 units tend to form polymeric chains that are interconnected with the SiO4 tetrahedral network [7,43]. Notably, sub-stoichiometric lead species (Pb–O, where x = 1), which are typically associated with such pyramidal chains in high-lead silicate glass, were detected exclusively on the glass side of the ancient Chu mirrors and were absent in the alternative reproductions [42,47].

This distinction correlates with differences in PbO concentration within the glass layers. The ancient Chu sample (CM1) contains 32.24 wt% PbO, which, although slightly below the 40 wt% threshold reported in the literature, is substantially higher than the 17.3 wt% measured in the alternative Chu sample (Table 1). The presence of these structural signatures in the ancient mirrors suggests that locally elevated Pb concentrations or specific ancient firing conditions may have promoted the formation of these polymeric linkages. To further elucidate these complex glass structures, more detailed spectroscopic investigations, such as solid-state NMR or Raman spectroscopy, are recommended for future studies.

Pb0 species were first detected at approximate depths of 5.9 nm and 5.0 nm from the surface on the glass side of the ancient and alternative Chu mirrors, respectively, with a higher concentration and a more pronounced increase observed in the ancient sample. This difference can be attributed to variations in the PbO content of the glass composition. Such a phenomenon is commonly observed in lead silicate glass with a high lead oxide content. These photoelectrons may originate from self-bonded Pb-Pb interactions, potentially associated with PbO4 pyramidal polymer chains within the PbO-SiO2 glass system, as noted by Morikawa et al. [42] and Wang et al. [47]. Alternatively, they may arise from isolated Pb atoms formed during the reduction of PbO in the melting process. The higher concentration of these species in the ancient Chu mirror may be linked to the use of a reducing atmosphere in ancient firing kilns.

Notably, PbO4 species were detected on the lead sides of both ancient and alternative Chu mirrors, with higher amounts observed in the alternative mirror compared to the ancient one. This difference may be attributed to variations in the lead raw materials used for coating. In our research, artisans repeatedly melted lead in a pan to save costs, which may have allowed PbO4 to form over time. Based on our experience, freshly melted lead consistently produces superior coating results. According to the previous work by Eggert and Fischer [10], oxygen-related issues during the practical coating process contributed to variations in mirror quality. The primary technical challenge was “drossing”—a rapid oxidation process that occurs when lead is melted in air, forming solid oxide particles that degrade the mirror’s reflective surface with an unsightly powdery layer. To address this, ancient craftsmen employed hollow spheres with narrow openings to limit oxygen exposure and often melted the lead separately, skimming off the oxide layer before pouring the purified metal onto the glass. This technique offered a significant advantage in the ancient coating process by minimizing surface oxidation. In contrast, the alternative mirror, made by drawing glass sheets, was inevitably exposed to ambient air containing oxygen. This exposure increased the likelihood of oxidation during lead coating, potentially resulting in the formation of various oxidized lead species at the interface.

This finding underscores the importance of precise control over coating conditions, as these interfacial phenomena are critical to the long-term durability and adhesion of the lead layer. Future studies comparing historical and modern coating techniques could provide valuable insights into optimizing restoration practices while preserving the authenticity of ancient artifacts.

4. Conclusions

With a focus on their distinctive “gold glass” qualities and lead-coated surfaces, this study offers a chemical and structural analysis of both ancient and alternative Chu mirrors. With the lead oxide (PbO) content ranging from 4.28 to 48.17 wt%, chemical tests employing methods including pXRF, WD-XRF, SEM, and XPS showed that the mirrors were primarily made of a mixed lead–alkaline glass type. The yellow coloration of the glass was significantly affected by iron oxide (Fe2O3) and manganese (MnO), with redox conditions during production being a critical factor. The analysis identified distinct material compositions, including wood-ash lead glass in certain samples, which underscores shared silica sources while revealing variations in fluxes and production methods.

The most significant finding occurs at the interfacial boundary, where a sophisticated bonding mechanism governs the lead–glass interaction. The identification of disordered, chain-like Pb–O–Pb linkages indicates the formation of a structural bridge between the metallic lead coating (Pb0) and the rigid silicate glass network. This interfacial reaction zone, extending to a depth of approximately 6 nm in the ancient mirrors, effectively accommodates internal strain arising from thermal expansion mismatch between the two materials. In addition, the ancient samples exhibit a distinctive photoelectron energy-loss feature and a localized distribution of hydrated lead species near the surface (~2.5 nm), reflecting enhanced metallic integrity and long-term interfacial stabilization. These features are significantly reduced or absent in the modern reproductions.

These discoveries highlight how technologically advanced ancient glassmakers were, especially in their capacity to control materials and procedures to produce desired results. This research enhances knowledge of the chemical composition, production techniques, and bonding mechanisms of these mirrors, offering important insights for their conservation, restoration, and reproduction as culturally significant artifacts. Further research into the origins of raw materials and the improvement of replication techniques will help to preserve this distinctive glassmaking tradition.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/heritage9020053/s1, Figure S1: Spatial distribution of sampling locations where Kriab and Chu mirrors were identified across Thailand and selected sites in neighboring countries. GPS coordinates for each location are provided in Tables S1 and S2.; Table S1: Detailed latitude and longitude data for each location where Chu Mirrors was discovered in Thailand.; Table S2: Detailed latitude and longitude data for each location where Kriab Mirrors was discovered in Thailand. Table S3: Specifications of the high-purity commercial lead used for coating the alternative Chu mirror samples.; Video S1: Flexibility and application of Chu mirrors. The footage demonstrates the unique thin profile of Chu glass, which allows for cutting with shears and fitting onto curved artifacts techniques not feasible with the thicker, brittle Kriab variety.

Author Contributions

S.D.: writing—original draft, methodology, investigation, resources visualization; S.P. (Surapich Poolprasroed): methodology, investigation, resources; K.P.: conceptualization, validation, formal analysis, writing—review and editing, project administration, funding acquisition; S.E.: validation; A.K.: investigation, resources; P.I.: investigation, resources; S.P. (Surapong Panyata): investigation, resources; E.M.: formal analysis; T.D.: formal analysis, data curation; P.K.: data curation; P.P.: data curation; J.P.: data curation; C.S.: data curation; M.K.: data curation; T.S.: methodology, investigation, data curation; N.K.: visualization, data curation; T.T.: supervision. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by two main funding sources. The first was the National Research Council of Thailand (NRCT) through the project titled “Materials Characterization of Ancient Thai Mirrors and Fabrication of Lead-Free Prototypes” (NRCT5-RSA63004-01). The second source of funding was the Suvannabhumi Project from the Thailand Academy of Social Sciences, Humanities, and Arts (TASSHA), under the Ministry of Higher Education, Science, Research, and Innovation, through the project titled “Ancient Mosaic Mirror Survey and Glass Mirror Work for Use in Architecture and Arts in the Suvarnabhumi Region.” Additional support for this research was provided by the Center of Excellence in Materials Science and Technology and Chiang Mai University.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to the staff of the Synchrotron Light Research Institute (SLRI), Thailand, for their assistance with XRF measurements; the staff of the Department of Science Service for their support with WD-XRF measurements; the staff of the Center of Excellence in Physics for their expertise and assistance with XPS analysis; and the staff of the Advanced Scientific Instrumentation Unit, Faculty of Science, Chiang Mai University, for their help with WDS and SEM-EDS analyses. The authors would like to extend their sincere gratitude to Udom Riantrakool, a private antiquities collector, for generously providing a decorative lead-coated mirror-on-fur sample presumed to originate from Pakistan, as well as golden mirrors decorated on Tapis from Lampung, Sumatra, Indonesia. His kind support and willingness to share these rare materials were invaluable to the present study. We also wish to thank the Fine Arts Department, Ministry of Culture, Thailand, for granting permission to conduct a nationwide survey of Thai glass mirrors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interest or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Bellina-Pryce, B.; Silapanth, P. Weaving cultural identities on trans-Asiatic networks: Upper Thai-Malay Peninsula–an early socio-political landscape. Bulletin de l’École française d’Extrême-Orient 2006, 93, 257–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glover, I.; University of Hull Centre for South-East Asian Studies. Early Trade Between India and Southeast Asia: A Link in the Development of a World Trading System; University of Hull Centre for South-East Asian Studies: Hull, UK, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Lankton, J.W.; Dussubieux, L. Early Glass in Southeast Asia. In Modern Methods for Analysing Archaeological and Historical Glass; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013; pp. 415–443. [Google Scholar]

- Klysubun, W.; Hauzenberger, C.A.; Ravel, B.; Klysubun, P.; Huang, Y.; Wongtepa, W.; Sombunchoo, P. Understanding the blue color in antique mosaic mirrored glass from the Temple of the Emerald Buddha, Thailand. X-Ray Spectrom. 2015, 44, 116–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klysubun, W.; Ravel, B.; Klysubun, P.; Sombunchoo, P.; Deenan, W. Characterization of yellow and colorless decorative glasses from the Temple of the Emerald Buddha, Bangkok, Thailand. Appl. Phys. A 2013, 111, 775–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravel, B.; Carr, G.L.; Hauzenberger, C.A.; Klysubun, W. X-ray and optical spectroscopic study of the coloration of red glass used in 19th century decorative mosaics at the Temple of the Emerald Buddha. J. Cult. Herit. 2015, 16, 315–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Won-In, K.; Dararutana, P. Elemental distribution of the greenish-Thai decorative glass. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2018, 1082, 012084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Won-in, K.; Thongkam, Y.; Pongkrapan, S.; Intarasiri, S.; Thongleurm, C.; Kamwanna, T.; Leelawathanasuk, T.; Dararutana, P. Raman spectroscopic study on archaeological glasses in Thailand: Ancient Thai Glass. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2011, 83, 231–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ounjaijom, T.; Intawin, P.; Kraipok, A.; Panyata, S.; Chanchiaw, R.; Teeranun, Y.; Gaewviset, P.; Boonprakong, P.; Meechoowas, E.; Disayathanoowat, T.; et al. Chemical and Mechanical Characterization of the Alternative Kriab-Mirror Tesserae for Restoration of 18th to 19th-Century Mosaics (Thailand). Materials 2023, 16, 3321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eggert, G.; Fischer, A. Mirrored with molten lead: Convex mirror glass through the ages. In Proceedings of the Working Towards a Sustainable Past. ICOM-CC 20th Triennial Conference, Valencia, Spain, 18–22 September 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Kock, J.; Sode, T. Medieval glass mirrors in Southern Scandinavia and their technique, as still practiced in India. J. Glass Stud. 2002, 44, 79–94. [Google Scholar]

- Carmona, N.; Villegas, M.A.; Jiménez, P.; Navarro, J.; García-Heras, M. Islamic glasses from Al-Andalus. Characterisation of materials from a Murcian workshop (12th century AD, Spain). J. Cult. Herit. 2009, 10, 439–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krueger, I. Glasspiegel im Mittelalter II: Neue Funde und Neue Fragen; Rheinland-Verlag: Cologne, Germany, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Krueger, I.; Ihmsen, H.; Mommsen, H.; Eggert, G.; Ingeborg, K. Glasspiegel im Mittelalter: Fakten, Funde und Fragen: Naturwissenschaftliche Untersuchungen an Mittelalterlichen und Neuzeitlichen Glasspiegeln/Ingeborg Krueger; Rheinischen Landesmuseums: Bonn, Germany, 1990; pp. 233–319. [Google Scholar]

- Ostapkowicz, J. ‘Made … With Admirable Artistry’: The Context, Manufacture and History of a Taíno Belt. Antiqu. J. 2013, 93, 287–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupré, S. Vincent Ilardi. Renaissance Vision from Spectacles toTelescopes. Memoirs of the AmericanPhilosophical Society 259. Philadelphia. AmericanPhilosophical Society. 2007. Renaiss. Q. 2008, 61, 250–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liebig, J. Ueber Versilberung und Vergoldung von Glas. Justus Liebigs Annalen der Chemie 1856, 98, 132–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhranuphap, P.W. Somud Pok Dam: Treatise on Glass Melting and Red Glass Preparation. R. Tech. Manuscr. 1860. [Google Scholar]

- Gratuze, B. Provenance Analysis of Glass Artefacts. In Modern Methods for Analysing Archaeological and Historical Glass; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013; pp. 311–343. [Google Scholar]

- Barrera, J.; Velde, B. A study of french medieval glass composition. Archéologie Médiévale 1989, 19, 81–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billaud, Y.; Gratuze, B. Les perles en verre et en faïence de la Protohistoire française. In Matériaux, Productions, Circulation, du Néolithique à l’Âge du Bronze; Séminaire du Collège de France: Paris, France, 2002; pp. 193–212. [Google Scholar]

- Brill, R.H. Chemical analyses of some glasses from Frattesina. J. Glass Stud. 1992, 11–22. [Google Scholar]

- Hartmann, G.; Kappel, I.; Grote, K.; Arndt, B. Chemistry and Technology of Prehistoric Glass from Lower Saxony and Hesse. J. Archaeol. Sci. 1997, 24, 547–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, J. Electron probe microanalysis of mixed-alkali glass. Archaeometry 1988, 30, 77–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lilyquist, C.; Brill, R.H.; Wypyski, M.T. Studies in Early Egyptian Glass; Metropolitan Museum of Art: New York, NY, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Sayre, E.V. Some Ancient Glass Specimens with Compositions of Particular Archaeological Significance; Brookhaven National Lab: Upton, NY, USA, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Shortland, A.J.; Tite, M.S. The Interdependence of Glass and Vitreous Faience Production at Amarna. In Prehistory and History of Glassmaking Technology; McCray, P., Ed.; Ceramics and Civilization; American Ceramic Society: Westerville, OH, USA, 1998; pp. 251–265. [Google Scholar]

- Ptak, R. Asia’s Maritime Bead Trade, 300 B.C. to the Present. By Peter Francis Jr pp. xii, 305. Honolulu, University of Hawai’i Press, 2002. J. R. Asiat. Soc. 2004, 14, 134–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sablerolles, Y.; Henderson, J.; Dijkmann, W. Early Medieval Glass Bead Making in Maastricht (Jodenstraat 30), the Netherlands: An Archaeological and Scientific Investigation. In Perlen: Archäologie, Techniken, Analysen; von Freeden, U., Wieczorek, A., Eds.; Habelt: Bonn, Germany, 1997; pp. 293–313. [Google Scholar]

- Tite, M.; Pradell, T.; Shortland, A. Discovery, production and use of tin-based opacifiers in glasses, enamels and glazes from the Late Iron Age onwards: A reassessment. Archaeometry 2008, 50, 67–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brill, R.H. Chemical Analyses of Early Glasses; The Corning Museum of Glass: New York, NY, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Fuxi, G. Origin and Evolution of Ancient Chinese Glass. In Ancient Glass Research Along the Silk Road; World Scientific Publishing Company: Singapore, 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koezuka, T. Scientific Study of Evolution of Ancient Glasses Found in Japan. Ph.D. Thesis, Tokyo University of the Arts, Tokyo, Japan, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Mecking, O. Medieval Lead Glass in Central Europe. Archaeometry 2013, 55, 640–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Téreygeol, F.; Gratuze, B.; Foy, D.; Lancelot, J. Les scories de plomb argentifère: Une source d’innovation technique carolingienne? In Artisans, Industrie, Nouvelles Révolutions du Moyen Age à nos Jours; Coquery, N., Ed.; Cahiers D’histoire et de Philosophie des Sciences: Paris, France, 2004; Volume 52, pp. 31–40. [Google Scholar]

- Brain, C.; Brain, S. John Greene’s Glass Designs 1667-167. In Proceedings of the Annales du 16e Congrès de l’Association Internationale pour l’Histoire du Verre, London, UK, 7–13 September 2003; pp. 263–266. [Google Scholar]

- Follmann-Schultz, A.B. Die Römischen Gläser aus Bonn; Rheinland-Verlag: Köln, Germany, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Solé, V.A.; Papillon, E.; Cotte, M.; Walter, P.; Susini, J. A multiplatform code for the analysis of energy-dispersive X-ray fluorescence spectra. Spectrochim. Acta Part B At. Spectrosc. 2007, 62, 63–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wedepohl, K.H.; Krueger, I.; Hartmann, G. Medieval lead glass from northwestern Europe. J. Glass Stud. 1995, 37, 65–82. [Google Scholar]

- Eggert, G.; Hillebrecht, H. The enigma of the emerald green. In Archaeometry 98; Archaeopress: Oxford, UK, 2002; pp. 525–530. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, H.; Henderson, J.; Sablerolles, Y.; Chenery, S.; Evans, J. Early Medieval Glass Production in the Netherlands: A Chemical and Isotopic Investigation; Cultural Heritage Agency of the Netherlands: Amersfoort, The Netherlands, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Morikawa, H.; Takagi, Y.; Ohno, H. Structural analysis of 2PbO·SiO2 glass. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 1982, 53, 173–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palomar, T.; Mosa, J.; Aparicio, M. Hydrolytic resistance of K2O–PbO–SiO2 glasses in aqueous and high-humidity environments. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2020, 103, 5248–5258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, S.; Lancelotti, R.; Hung, I.; Gan, Z. Characterization of the Pb Coordination Environment and Its Connectivity in Lead Silicate Glasses: Results from 2D 207Pb NMR Spectroscopy. J. Phys. Chem. B 2024, 128, 2811–2820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pask, J.A. From technology to the science of glass/metal and ceramic/metal sealing. Ceram. Bull. 1987, 66, 1587–1592. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, M.L. Hydroxyl groups on silica surface. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 1975, 19, 299–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.W.; Zhang, L. Structural role of lead in lead silicate glasses derived from XPS spectra. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 1996, 194, 129–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.