Abstract

This article analyzes the Solimene façade (Vietri sul Mare, Campania, Italy, 1952–1955). The survey, already acquired with active and passive sensors, was integrated with close-range photogrammetry of some sections of the main wall. The purpose of the new acquisitions was to generate data to inform a plug-in that, in the latest versions of the Revit software, correlates parametric and procedural environments. The focus of the study was the rationalization of the formal structure of the amphora, the heart of the main façade. Logic and geometric language guide the identification of a possible mathematical relationship aimed at parametrically modifying the model. The logical diagrams, converted into a Grasshopper preview, can be managed through graphical nodes. In the form of flowcharts (visual scripts), the finite sequence of procedural steps has the advantage of managing and modifying, in real time and in a user-friendly manner, the morphometric characteristics of the small “mummarella.” The results identify the morphometric characteristics common to a typological family composed of Vietri amphorae that, in the field of architectural design, uses the typical functions of system families. The goal is to approach sustainable and participatory design solutions by providing functions that can be graphically manipulated from within the software environment.

1. Introduction

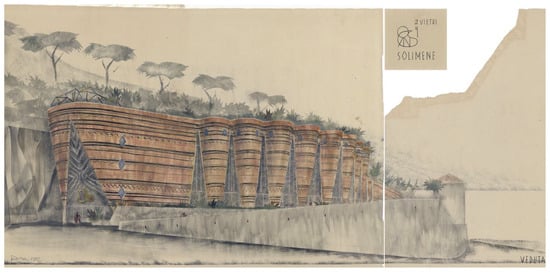

For the south facade of the artistic ceramics factory, Paolo Soleri (Turin 1919–Cosanti 2013) conceived a ribbon façade modulated by eleven opaque volumes variably projecting from bottom to top. The opaque volumes are divided by nearly floor-to-ceiling trapezoidal windows. The interior reflects the organization of the old Solimene factory located in Marina di Vietri [1] (pp. 33–42), a charming town in southern Italy, overlooking the Gulf of Salerno. In the new factory, designed to be built halfway up the rocky spur that marks the Amalfi coast, the interior spaces were conceived to be functional for the production chain [2] (pp. 29–32). From the commercial spaces on the ground floor, the path leads to the exhibition hall overlooking the panoramic rooftop terrace facing the gulf. The ramps leaning against the mountain connect the levels, and the sequence of work phases is organized within the convex spaces of the opaque bodies. The architecture helps regulate light and a comfortable temperature.

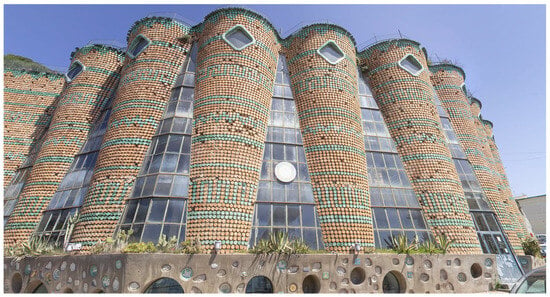

Convex on the outside, the opaque bodies lighten the appearance of the massive façade. From the sea, they evoke the image of large flower boxes from which a lush patch of Mediterranean vegetation emerges (Figure 1). The façade acts as a sort of advertising poster for the glazed terracotta crockery produced and sold within the large cavity protected by a wall of amphorae stacked horizontally along the edges of the slabs. The amphorae replace the traditional perforated bricks, ensuring static and climatic functionality as well as aesthetics (Figure 2). The polychromies of the wall are not derived from the cladding but from the juxtaposition of the bright green glazed bases alternating with reddish ones in rough terracotta. Approximately twenty thousand amphorae of the type used in the area to transport fresh water (mummarelle in local parlance) were forged on site by the factory’s own employees. Completing the construction quickly and keeping costs down had become urgently needed after the numerous changes imposed by the authorities responsible for issuing the building permits.

Figure 1.

Paolo Soleri’s original drawing for the front elevation of Ceramica Artistica Solimene (Artistic Ceramics Solimene), dated Vietri February 1952. Black and chine ink colour on velum paper, 85.7 cm × 9 cm × 35.2 cm. Reproduced by kind permission from the Soleri Archives.

Figure 2.

Solimene factory. View from the south façade, via degli Angeli, Vietri sul Mare Italy. Photo taken by the authors.

The investigation developed in this article is based, as underlined in “Tools and Methods”, on the results of the survey recursively followed by experimenting with diversified techniques and instruments. The Structure from Motion survey referred to in the “State of the Art” is recalled here to exclusively define the morphometrics of the amphora, locally known as “mummarella”. The results, in fact, focus on the rationalization of the formal structure of the Vietri amphora. Logic and geometric language guide the search for a possible mathematical relationship with which to govern the modification of the conformation, respecting the attributes identified. The conceptual schemes are presented in the form of flowcharts (visual script). The finite sequence of procedural steps has the advantage of modifying the formal characteristics in real time, activating graphical nodes.

The results, although interactively dynamic, are affected by the limitations deriving from the original procedures which are static. To integrate parametric morphometry into a more fluid design process, a workflow is proposed. Rhinoceros and Grasshopper, as additional Revit plug-ins, act as bridges to develop scenarios based on the correlation between parametric and procedural environments. Without losing the advantages offered by the procedures used, we explore the features that, in the latest versions of the Revit 2025 authoring software, employ a cloud collaboration. A group of amphorae with common attributes and parametric variable properties (a custom-built typological family) that, if recognized as native by the system, can govern the form to offer sustainable solutions.

Combining tradition and innovation, the wall conceived by Paolo Soleri has proven, as the authors have already emphasized in other texts, to be extremely functional in terms of static and energy efficiency, as well as aesthetics and style. References to the regulatory framework, expanded documentation, and a discussion of the challenges presented by the as-built application characterize the objectives achieved and in progress.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Hypothesis and Thesis

The aim of the study is to delve deeper into the level of detail of the “wall component” reconstructed within an HBIM (Historic Building Information Model) workflow (the acronym coined by [3]). To extend the method’s advantages to “inherited” architecture [4], it is necessary to “offer” the “mummarelle” a “typological family”. In other words, it is necessary to programme a category of objects, in this case, amphorae, that share invariable attributes but whose properties can be modified [5]. Typological families are governed by specific, predefined laws and parameters for the specific category.

The challenge, therefore, lies in the ability to transform reality-based surfaces into discretized, dynamically modifiable “objects.” Despite the efforts of scientific research, this approach is still somewhat lacking [6].

Groups of elements with common properties and related graphical representations, known as families, offer powerful support for the digital construction of artefacts that use prefabricated and industrial components.

When dealing with complex surfaces, such as those of the Solimene façade, two major difficulties arise: the geometric simplification of polynomial/curved shapes, which results in (i) the loss of detail and consequently compromises the accuracy of the as-built model, and (ii) the lack of typological families suitable for the “digital” construction of the wall, conceived and built using artisanal techniques. Both are hot topics in the international research landscape.

The focus, as per the object, is on the identification of a “family of Vietri mummarelle”, that is, a group of types selected based on common properties and organized to present “readability gradients” based on a modifiable code (DNA), like the one used by the “system” families, through editable categories. The tasks of the general coordination model (BIM) are assembling and managing components. The rapid automation of phases and processes does not seem to obscure the focus on methodological issues, including those of identity for the cultural area of survey and architectural representation. The theses of this article are based on a study of the formal structure of the “mummarella”. Geometric logic underpins the quad-dominant remeshing (retopology) choices necessary to reconcile conflicting needs, such as the accuracy of reality-based models and the IT management of their 3D assets [7]. Using some features of Autodesk’s Revit 2025 software [8], a parametric law based on the survey of different types of amphorae is proposed to automatically generate a single model of the species. The models, if adequately integrated with information, aim to manage modifications to the Solimene façade or to reshape a wall that has inherited its functional, static, and aesthetic qualities. The wall’s proven sustainability encourages the transformation of a CAD project into a virtual BIM construction to ensure maintenance and restoration throughout the building’s lifespan. Current Italian legislation recommends, even in the case of an inherited building, the “Digital Management of Construction Information Processes” (UNI 11337:2017, Part IV) as the technical standard, as per the international BIM regulations in the ISO 19650 series [9]. The levels of technical and geometric completeness (LoD) of the components must be completed based on the agreed-upon digital use. This leads to the justified desire to continue the survey to make the wall component detail “executive” (Legislative Decree No. 36/2023—Public Contracts Cod).

2.2. State of the Art

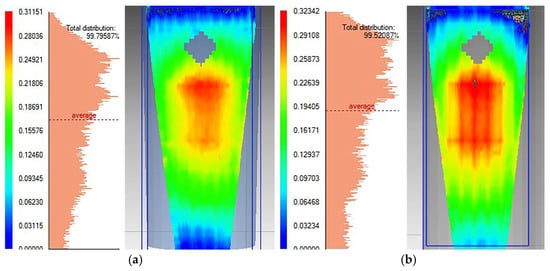

The topographic support coordinates, acquired with a Trimble S6 Vision total station [10], were integrated with rapid capture of thousands of RGB point coordinates (min. 976,000 pts/sec). Acquisition with a terrestrial laser scanner (Faro Focus 130 HDR) preceded measurement of the gap between the clean and decimated point cloud (objective but discontinuous) and the ideal model of the wall (continuous but subjective). Two plausible geometric interpretations emerged: an inverted cone or a right cylinder with a slightly oblique axis. The histograms shown in (Figure 3a,b) plot the parametric values obtained from formal deviation mappings examined both in the plane and in space.

Figure 3.

Model deviation on the plane yz: (a) conical configuration; (b) cylindrical configuration. The colors show the calculated gap between the discontinuous but objective model derived from the processing of the 3D point cloud and the continuous but ideal geometric model relating to a cylindrical and a conical configuration with the vertex at the bottom. Red indicates the greatest discrepancy descending from the others according to the known light wavelengths.

The applications verified that 99.52087% of the real points deviate no more than 24 cm from the configuration of a right cylinder with an axis inclined at 7.26°, while the deviation is slightly greater (99.795087%) if the real points are compared with a conical configuration whose vertex is located low and well beyond the foundations [11].

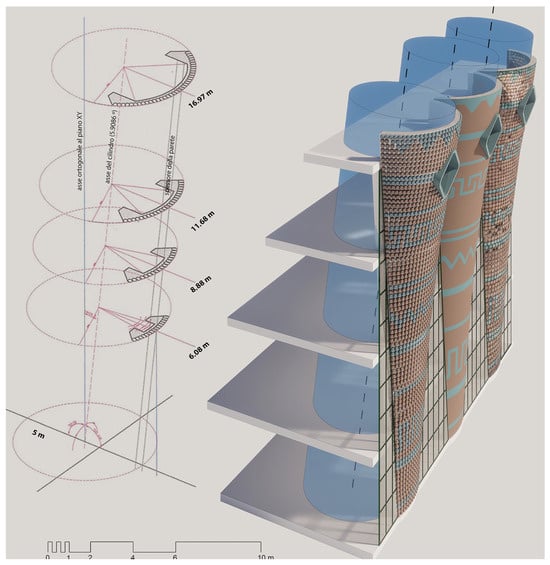

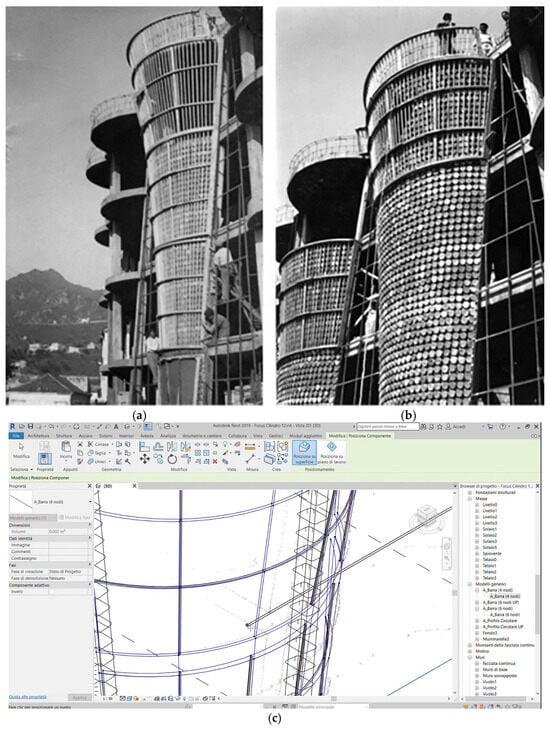

Having discarded the hypothesis of a conical configuration (which was led by careful exploration of the sites, as well as a rational analysis of the data), the methods of a possible construction of a straight cylindrical body with a gently oblique axis were examined (Figure 4). The construction shown by level (Figure 5a,b) suggests a relatively simple installation. Once the pillars, floors, and connecting ramps that replace the stairs have been shaped, the external curtain wall is built without scaffolding. Following the curved profile of the floors, the amphorae are placed horizontally between the reinforced concrete pillars. The bases face outwards, and each row projects progressively until it covers the usable height of the level. Wooden formwork guides the installation. It is interesting to note that the main structure, consisting of four vertical and three horizontal uprights, reflects a criterion that is repeated in the virtual construction site (Figure 5c).

Figure 4.

Survey of opaque bodies: on the left, configuration derived from a direct survey of a sample [12]; on the right, from the textured point cloud to information modelling [12] based on Faro 3D laser scanner acquisitions [13].

Figure 5.

Solimene factory: (a,b) the formwork system used for installing the “mummarelle”, photo by [14]; (c) screenshot of the Revit software. The facade was modelled with the “mass” function structured to imitate the configuration of the formwork.

Continuity between the levels is ensured by embedding coloured bowls forged for this purpose on the edge of the reinforced concrete slabs, i.e., bases of terracotta or green glazed amphorae to complete the geometric “Greek” design. The construction by levels justifies the discontinuities measured and recorded with the laser scanner survey (Figure 6). The obvious bottlenecks at the floor levels are the result of necessary adjustments made during construction [10].

Figure 6.

Opaque bodies. Detailed elevation and vertical section of the surveyed sample: from the reality-based 3D model to the geometric configuration of the profile [13].

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. From the Generic Level of Detail to the Defined LoD

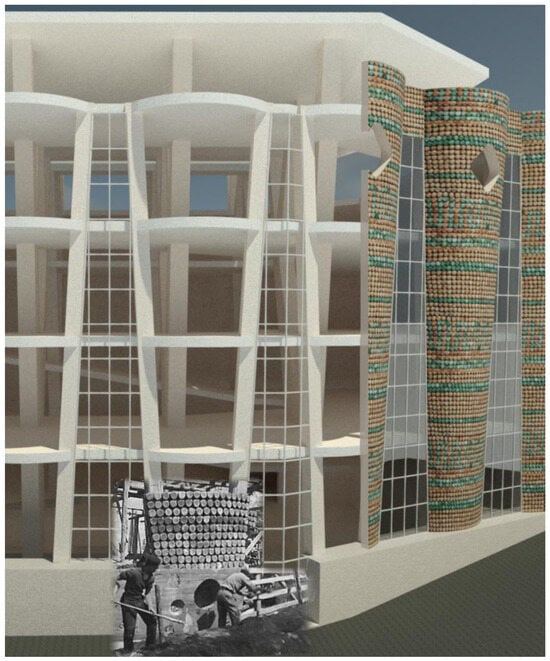

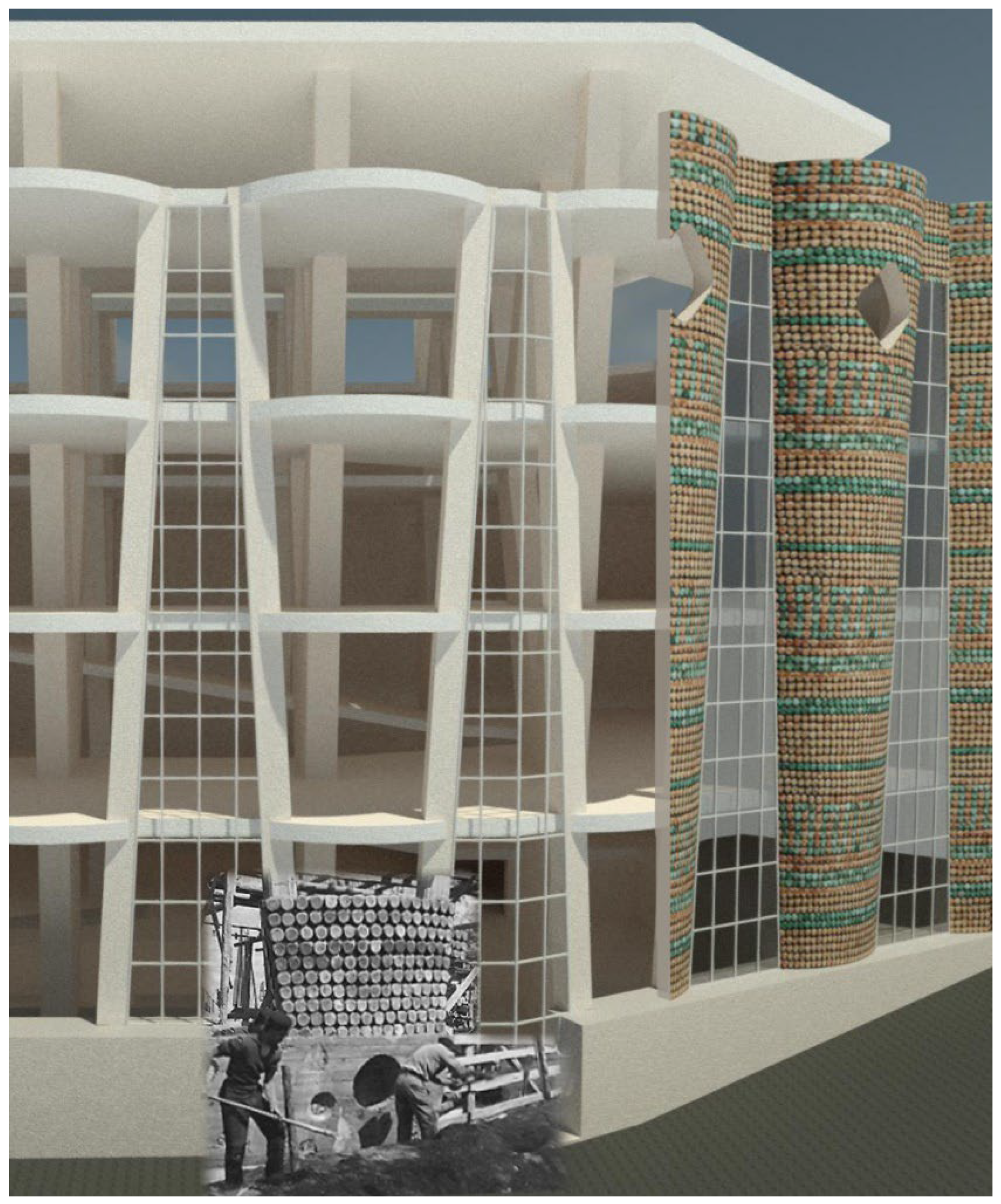

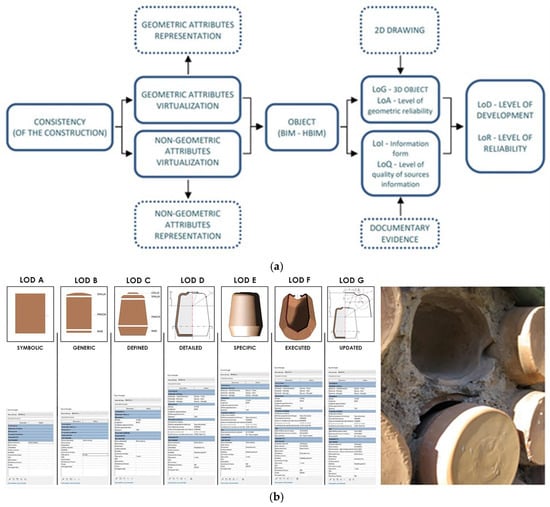

Previous studies have reconstructed an information model of the Solimene factory by comparing direct and indirect methods. In the first case, the main components, such as walls, pillars, floors, roofs, etc., were modelled in Rhinoceros using coordinate points, then information was added in Autodesk Revit using preset system categories [15]. These obviously cannot make the isolated components “intelligent,” although they are scalable in their volumetric footprint (Figure 7).

In the second case, the aforementioned components were derived from the “unstructured” model, that is, by importing the cleaned and decimated point cloud into the BIM authority software (Revit 2025). Indeed, organizing the general coordination model for historic buildings requires a theoretical and practical reversal of the BIM approach, moving from the survey of high-definition 3D surfaces to the typo-morphological management of components. The challenge thus arises in characterizing generic objects into dynamically functioning and interoperable equivalents. The approach is, in some respects, still lacking [6] but is sufficiently well-researched to guide the interpretative analysis of the amphora wall component considering current Italian legislation (Ministerial Decree 36/2023). To begin simulating the behaviour of the wall within an interconnected building structure, it is necessary to increase the level of geometric detail of the Solimene south façade (Figure 8a,b). Thus, in compliance with the BIM method [16], the procedure involves an additional survey and data processing phase.

Figure 7.

BIM Model AIA E202-2008. Detail of the jugs placed in the infill walls. Evocation of the phases that characterize both the real and digital construction sites [17].

Figure 7.

BIM Model AIA E202-2008. Detail of the jugs placed in the infill walls. Evocation of the phases that characterize both the real and digital construction sites [17].

Figure 8.

Interconnections of the different LoD levels. The model’s reliability derives from the synergy between geometric accuracy (LoA) and information quality (LoQ). (a) Schematic; (b) figurative interpretation of the levels established by Italian standards.

Figure 8.

Interconnections of the different LoD levels. The model’s reliability derives from the synergy between geometric accuracy (LoA) and information quality (LoQ). (a) Schematic; (b) figurative interpretation of the levels established by Italian standards.

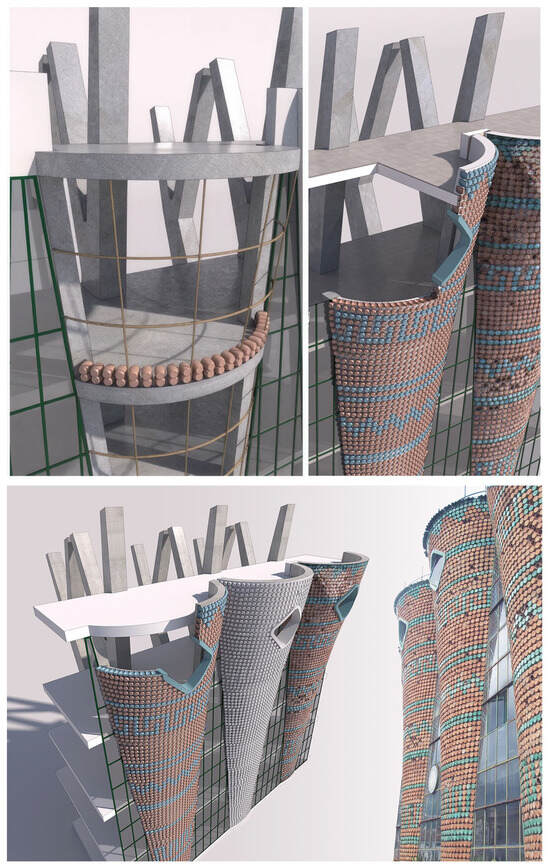

To build the virtual model of the external curtain wall, procedures like those used on a real construction site were followed (Figure 5c). Once the pillars, reinforced concrete floors, and connecting ramps had been erected, rows of progressively protruding amphora bases filled the usable height of each level (ceiling–floor). The continuous, curved, sloping-outwards wall was created floor by floor by applying the “wall by face” system family. This is a parametric family based on adaptive points. Using the “local masses” command, a support grid was created to allow “objects” to be attached to active nodes. This preserves the typical properties of customized parametric volumes for each case.

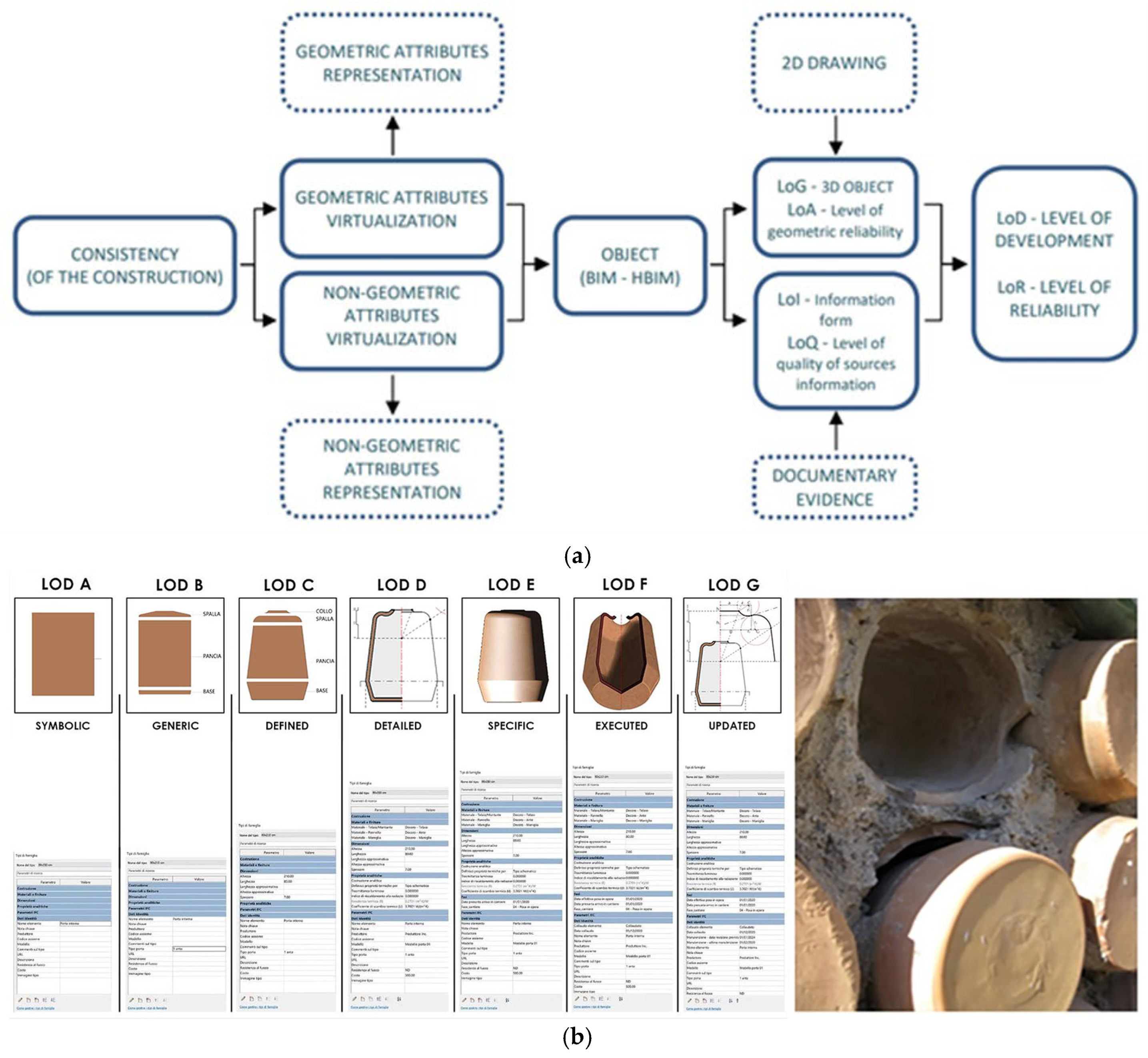

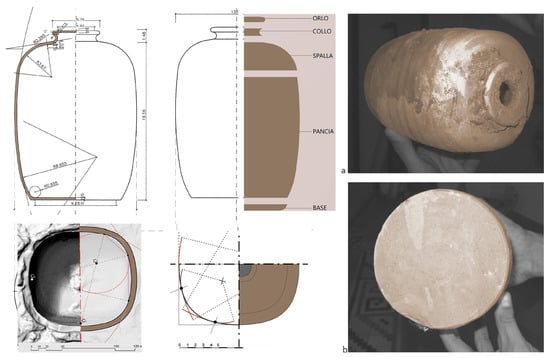

3.2. Survey of the Amphorae, the Core of the Façade Wall Component

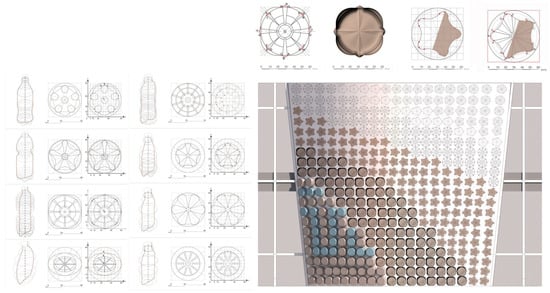

The masonry component was initially linked to a predefined construction technique, a system typology family [18]. The group of elements integrated in the software with common properties and a graphic representation (native system family) referred to the classic perforated clay bricks and, as such, could not be applied to the Vietri mummarelle wall. On the façade, the amphorae, without their bases and detached at eye level, facilitated the non-invasive survey of the exposed south wall. The interior was surveyed using the Structure from Motion (SfM) technique: a series of digital photographs, taken in motion and then processed by dedicated software (Agisoft Metashape Professional version 1.8.2), allowed to derive a reality-based 3D model of the interior. The result of the acquisitions is a numerical model that allows for millimetric precision measurements and meticulous checks on the material and chromatic state of the interior of the vases. The resulting models have been saved in Wavefront 3D Object File format (*.obj) to generate an editable model composed of more or less faceted polygons. A total of 22–29 shots were acquired with a Canon EOS 60D camera, coupled with a 60 mm lens. The camera settings, considering light conditions, were as follows: F-stop F/5.6; ISO 500; and shutter 1/40–1/200. Metric references were used by means of metal scales and targets with no colour reference. The original format (CR.2) was converted to JPEG using Camera Raw version 8.0. The analysis proceeded with the detailed study of the point clouds imported into the working software, with the following steps and related settings. Using horizontally and vertically positioned targets, the resulting models were scaled based on the measurements taken on site and then post-processed to correct them. Using a calliper, the thickness and the diameter of the amphora’s base were then measured on site. Upon inspection, not only visually but also mathematically, the amphora’s body has a quadrangular cross-section. This finding further confirms what was observed when examining one of the original amphorae found in the factory’s warehouse. The amphora is flattened laterally to increase the adhesion surface [19] (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Modelling of the amphora (small mummarella). Integration of the SfM survey of the interior with survey of the exterior.

3.3. Geometric Data Modelling

Unifying bodies regulate the characteristics that identify the level of detail. “Grades of Generation” standardize the right balance between geometric accuracy and information reliability. A sort of contractual metric establishes the minimum thresholds of information to be connected to the infographic model. The digital model is, in fact, designed to follow the development of the project during the various stages of the building construction process [20,21]. The so-called Levels of Development [22] of digital models seal the preliminary content for collaboration and efficiency. The BIM’s Exhibit Protocol establishes the operating and coordination methods for the phases: in America, AIA E202-2008 [23] (pp. 17–47), and according to international standards, such as ISO 19650, that replace national regulations [24] (pp. 21–28). In the case of historic buildings [25], it is necessary to analyze the documents and technical standards dating back to the period of construction of the building [26]. Direct knowledge, on the other hand, must recognize the clues that give identity to the building components of the architectural organism. The goal is to attempt to engineer phases that are entrusted to skilled labour (Figure 10).

Figure 10.

HBIM Solimene factory, south façade. Infill wall: from the Generic Model to the Detailed Model.

The authors began to address the issue by analyzing a masonry sample consisting of 3 × 4 amphora bases. The sample was subjected to reverse engineering analysis. Once the best pipeline had been chosen to reduce the digital weight of the model based on the fixed itacquisition of the real surface, finite element analysis (FEM) was carried out. The Finite Element Method is an advanced computer simulation technique.

The static-structural results obtained allowed the studies to focus on the nature of the fracturing dynamics of the bases of the mummarelle and on the cracking of the cement that connects them [27].

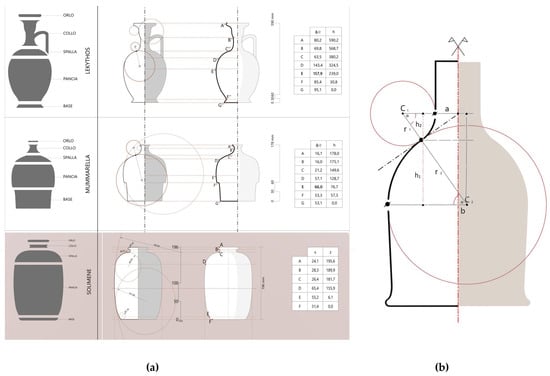

3.4. Data Processing: Circumstantial Paradigm

The acquired details were used to approach a phase enabling modifications to the wall. System commands translate, rotate, or proportionally reduce the typological structure. If, however, the intention is to dynamically modify the shape of the amphora, algorithmic values are required that are suitable for managing procedures that, while respecting the immutable characteristics of the typological species (attributes), shape the variable properties of the wall composed of Vietri amphorae. Careful naming of the parts precedes the identification of boundaries into which to subdivide the formal structure of the mummarelle. Comparing the surveys between structurally similar objects is helpful, as they can be divided into the same parts: base, belly, shoulder, neck, rim, and handle. Comparing measurements recorded between the joints, algebraic intervals are identified in which the changes in form are “credible.” These values are catalogued in spreadsheets, thus organizing frameworks to support design strategies. The “rules” direct algorithmic approaches that an internal editor displays in real time [28].

In recent years, we have seen an increasing number of approaches in the field of architectural design aimed at combining Building Information Modelling (BIM) and Visual Programming Language (VPL). These experiments have inspired new research focused on exploring the values, critical issues, and advantages of combined methodologies in the restoration and renovation of heritage buildings [29]. This integrated approach has encouraged the extension of the benefits derived from integrating parametric and algorithmic approaches.

At the basis of a Visual Programming Language is the study of graphic elements (blocks, icons, and symbols) to be used in place of text codes. It makes development intuitive and accessible, as well as the manipulation of curves [30]. Splines, in the literal translation of the term, “sufficiently initiated curves”, ensure continuity (at least up to a given order of derivatives) at interpolated or approximated points with programmed attractive weight. In this case, the so-called Basic Splines allow the changes in shape to be circumscribed in the surrounding area. Managed by systems of differential equations, NURBS (from Non-Uniform Rational B-Splines) can satisfactorily mediate conflicting requirements: they ensure the precision of the survey and the lightness necessary for the computer management of the model [31].

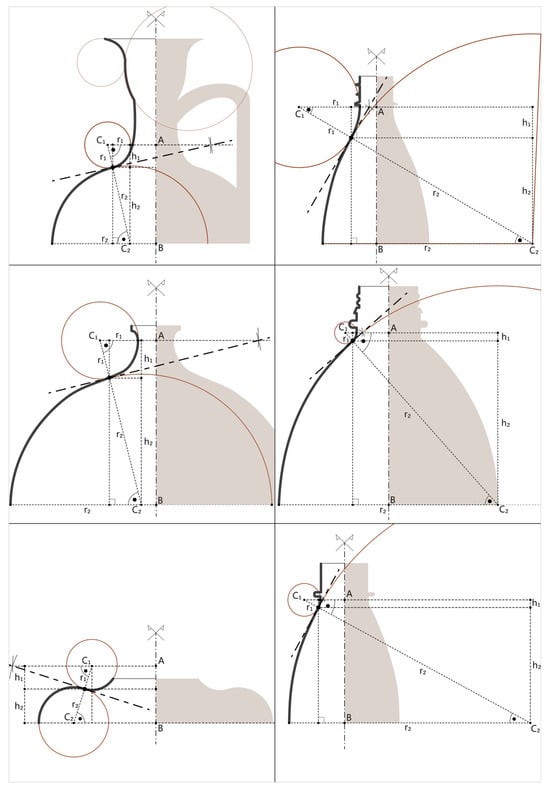

With respect to the stylistic morphological characteristics of the Vietri amphora, a CAD model derived from the survey was used. To identify a specific pattern, a sort of DNA of the Vietri amphora, it seemed useful to start by analyzing the connection between the shoulder and the neck. The neck of the small mummarelle is very narrow and ends with a well-rounded rim. Both features facilitate easy pouring of the liquids contained within. When constructing the wall, the narrow neck allows the inside to be grasped with two fingers to speed up installation, while the rim is used to secure the steel wire that connects them vertically before the concrete is poured. Without losing sight of the original survey, we studied the homothetic relationships between two similar triangles, identified with respect to the axis of the amphora bottle (Figure 11a). Equation f(x) of the tangent line guarantees the continuity of the curve at the point where the two arcs meet. The curve has no cusps at the point of tangency but continues smoothly to the point of contact where the derivative provides its slope [32]. To move from theory to practice, we study standard relations applicable to the profile at the connection points (Figure 11b).

Figure 11.

(a) Comparison among terracotta jugs and standard relations applicable at the profile connection points. (b) Focus on matching similar right-angled triangles.

The algebraic solution obtained after fixing the x-coordinates in reference to a bundle of parallel lines cut by transversals is easily identified. Defining the symbols r, R, h, a, b, and slope θ, as in Figure 11 and Figure 12, with Thales’ theorem, we have

from which at least one quantity among the mean proportional can be derived from the previous one.

Figure 12.

Continuity of the curve profile at the junction between neck and shoulder of vases (left side) and bottles (right side). Variations of similar right-angled triangles.

The slope also remains a dependent variable, being a function of the previous quantities. In the case under consideration, solving for the longer side of the right-angled triangles identified by cutting the bundle of parallel lines yields partial values such as (a) or (b) (Figure 11b).

From which

Or better,

The same problem can be solved trigonometrically as follows:

From which

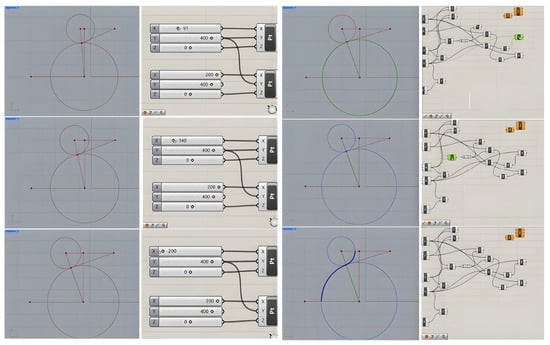

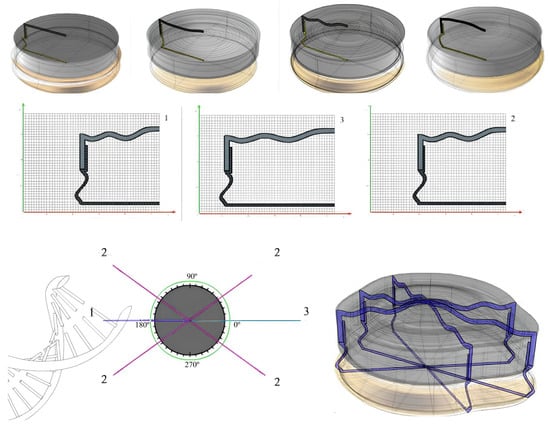

By connecting Rhinoceros (a software specialized in NURBS surface modelling) to Grasshopper (a plug-in that provides a visual programming environment based on block diagrams), we gain the flexibility we need for our purposes. Content changes in real time, adapting to the user’s choices. The identified law offers customized and interactive solutions, managing the database. Predefined conditions allow Revit to recognize imported “objects” as native to the authoring system, extending to them the editable properties typical of “system families.” These key features allow parametric amphorae to be modified and manipulated in real time. Within the visual programming environment [33], we advance towards the dynamic use of computational design. To advance towards an active design interface presentation, facilitating continuous exploration and design iteration in an interactive spatial context, a workflow was created, starting from the CAD model of the amphora modelled in Rhinoceros (Figure 12). Dialogue boxes allow access to spreadsheets divided into blocks of commands or instructions (macros) [34].

Based on circumstantial paradigms, a finite sequence of operations to be executed in the order of the programmed instructions (software definition) manages the model responsible for transmitting the hereditary characteristics of the Vietri amphora. The development of a methodological framework for variant generation is based on the code verified above using Grasshopper scripts linked to the free-form representation in Rhinoceros (Figure 13).

Figure 13.

Framework supporting the design strategies of the construction of the profile of the amphora. Variant of connection among curves.

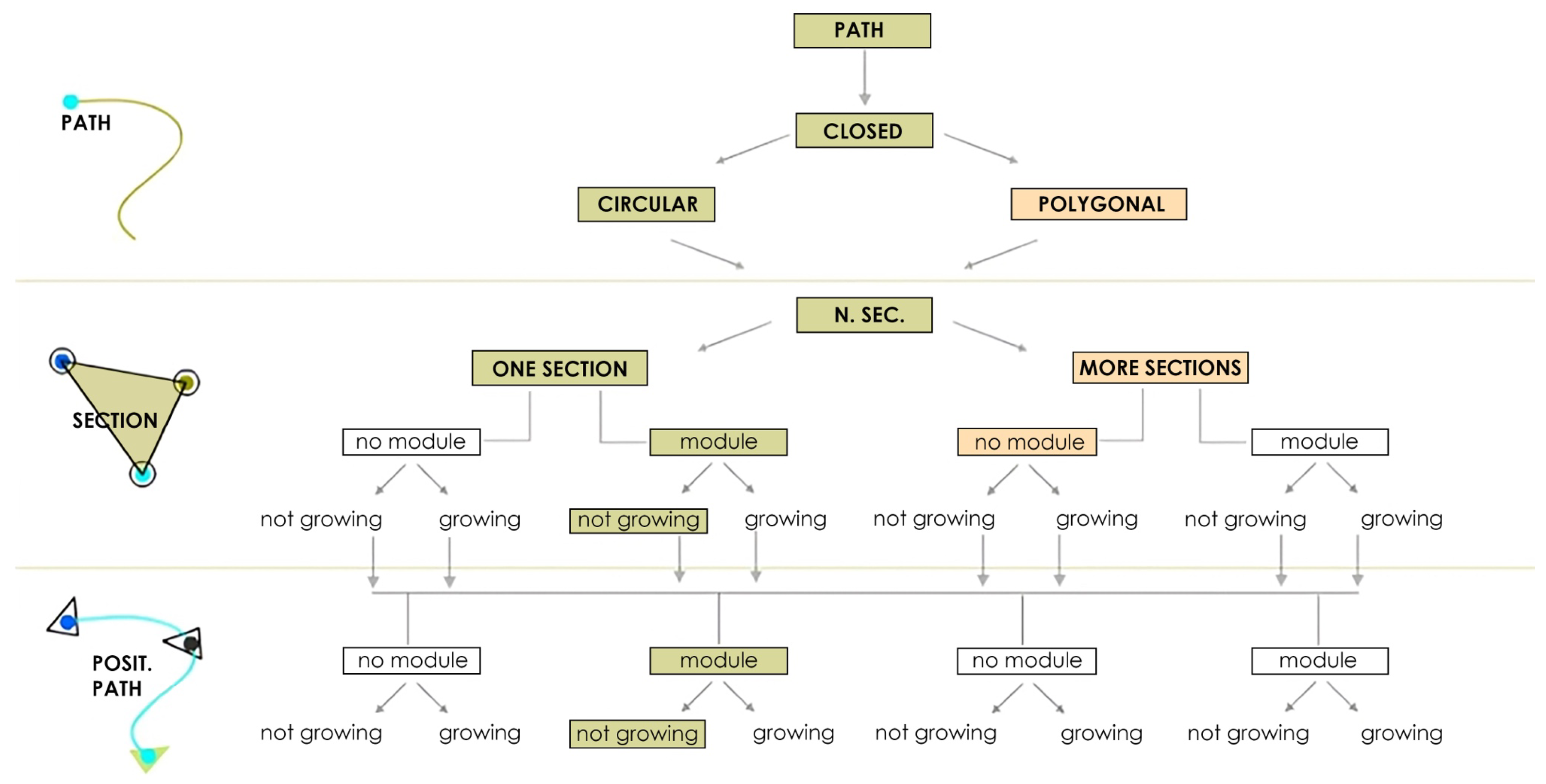

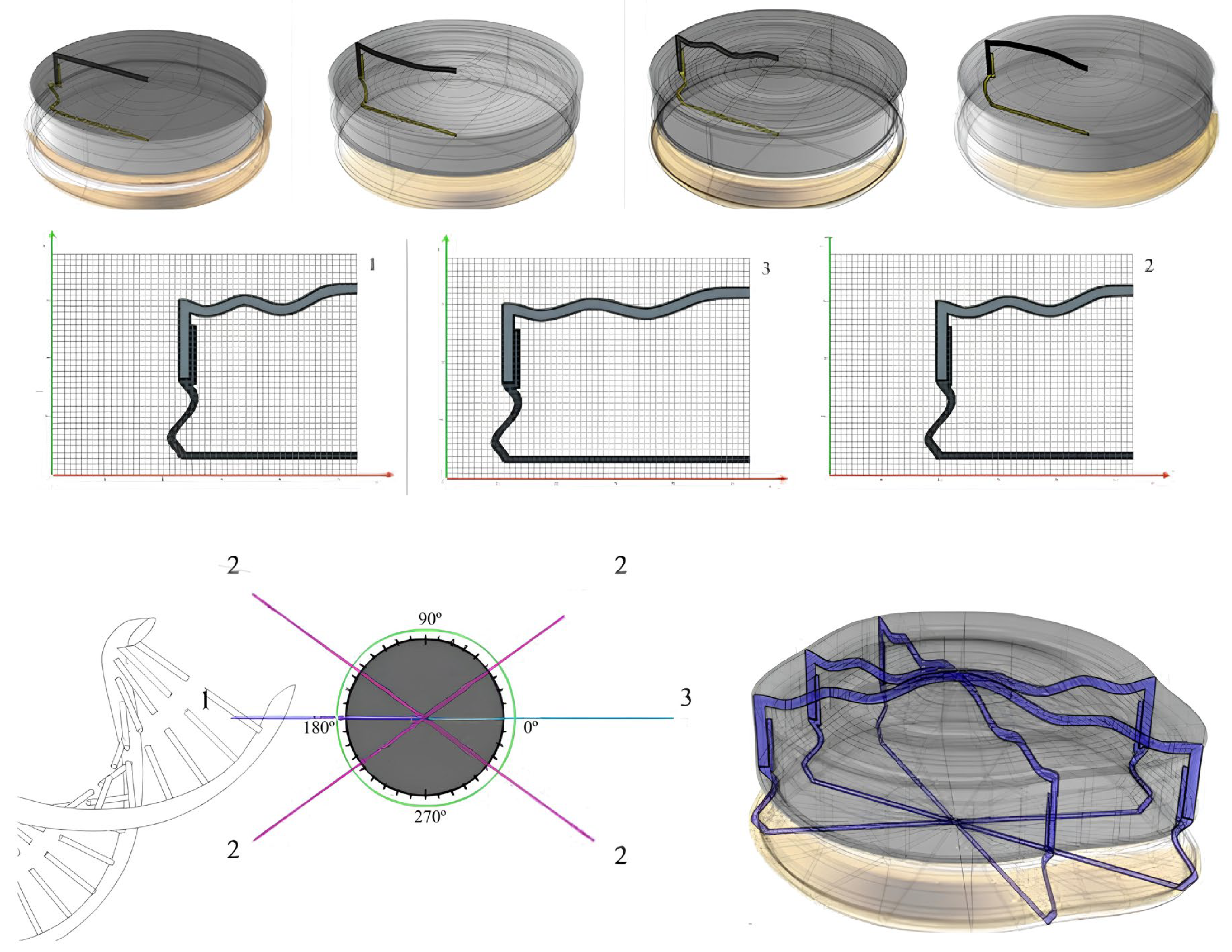

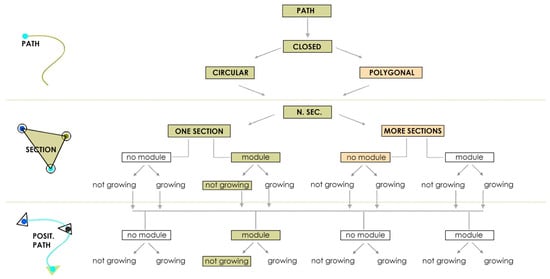

Focusing on some formal aspects of the horizontal sections, it becomes clear that the circular bases on the façade could be automatically modified. A latent, progressively articulated geometry (Figure 14) is reflected in the complexity of a circumstantial paradigm that, starting from a circle inscribed or circumscribed at the base of the amphora, defines a loop constrained by the starting point coinciding with the end point. A grid guides applications to the opaque body facade choice of the module, a concrete part of the object to operate based on multiples and submultiples. To suggest the transcription of criteria into space, an initial cycle of choices can be identified in the relationships established between guiding lines and generating lines.

Figure 14.

Identifying the parametric law from the circular “plate” to the automatic modification of the custom shape.

The roles can alternate to achieve a greater articulation of possibilities, further increased by changing the sections along the path, alternatively dragging them onto one or more tracks. A theoretical model is schematized in the figure (Figure 15). The graphic application of extreme modalities is considered indicative of the process (Figure 16). From what has been shown, there is no doubt about the role played by the geometric configuration, starting from the exact transcription of the survey: given the same results, the configuration technique changes the dependent variables, leading to a different strategy for modifying the model.

Figure 15.

Theoretical model.no.

Figure 16.

Application: Examples of 3D models obtained by articulation of the parametric law to generate one of the species.

Figure 15 schematically presents the alternatives derived from the three principal variations: (1) the path along which the section moves; (2) the parametric variation of the section; and (3) the position of the section along the path. The complexity increases when these three variations are combined. Figure 16 applies this theoretical model to an elementary configuration: a small jar modelled by revolving a generatrix (a vertical section) along a directrix (path). Modifying the generatrix section based on a parametric law automatically modifies the shape of the configuration obtained. The result obtained by interpolating several sections is shown in the lower part of the image.

4. Discussions and Conclusions

The role played by flexible modification of the amphora’s formal configuration offers a potentially effective response to the development of participatory and sustainable solutions. Rhinoceros and Grasshopper, as Revit plug-ins, provide a bridge for modifying a wall composed of Vietri amphorae. A specifically built typological “family” is recognized as to native the software authoring like the other system families.

To extend the advantages of the BIM method to the HBIM families, it is required to guarantee design interoperability, dynamic editing, and real-time visual manipulation. With complex surfaces, such as those of the Solimene façade, the geometric simplification of the detected shapes imposes the loss of details that the retopology process can overcome, control, and limit to a certain extent. However, the limitations imposed by the transition from reality-based surveying to “digital” construction and from “digital” construction to the parametric approach remain. The loss of accuracy impacts model management, making it more difficult to use for detailed analyses.

The immaturity of languages and standards for the specific modelling of existing structures (as-built) is consequently reflected in model interoperability. Specific family parameters can be, in fact, lost or misinterpreted. Experimental studies use “lighter” parametric families or model basic geometries, even for complex elements, accepting a loss of accuracy and precision of detail. Regardless of restoration and renovation issues, the parametric approach for the Vietri amphora families suggests studying the thermal inertia of the wall (new build), which is an energy-efficient solution. Thermal flywheels can be obtained by considering the possibility of filling the amphorae with water to build new walls. The results are certainly limited and partial, but their value lies in the method that supports a transversal perspective to advance the experimentation of procedures that can foster sustainable development, mediating tradition and innovation.

Concluding this brief focus, the picklock to identifying a mathematical relationship that can be transcribed into a visual script involves the critical analysis of existing data. By adopting the aesthetic and stylistic canons of the master craftsmen, dedicated platforms could meet climate/acoustic sustainability criteria. In this case, what is capitalized on in the digital construction site is primarily structured, codified, and aggregated information. However, from this perspective, the replicability of the proposed methodology in other historical contexts remains to be investigated: an evaluation of the time investment and specialized skills required to achieve the desired results and a discussion of how the ad hoc generated parametric family can be used for analysis and enriched with informative metadata in both BIM and HBIM environments.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.R.; methodology, A.R.; software, A.R., S.L.G. and S.G.B.; validation, A.R., S.L.G. and S.G.B.; formal analysis and investigation, A.R.; resources, A.R.; data curation, A.R.; writing—original draft preparation, A.R.; writing—review and editing, S.G.B.; visualization, and supervision, A.R., S.L.G. and S.G.B.; project administration, A.R.; funding acquisition, A.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Data Availability Statement

There are no dagtaset available online to be shared.

Acknowledgments

The authors want to thank those who have contributed to deepening their understanding of the factory over the years by collaborating on a vertical research project. The results of this unprecedented and original development have been validated in recent research exchanges with the UPV. Appreciation is therefore due to Università degli Studi della Campania Luigi Vanvitelli for funding the initiative and the research and teaching exchange.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Lima, A.I.; Arnaboldi, M. (Eds.) Ri-Pensare Soleri; Jaca Books: Milano, Italy, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Freidiani, G. Paolo Soleri e Vietri; Officina Edizioni: Rome, Italy, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, M.; Mcgovern, E.; Pavía, S. Historic building information modelling (HBIM). Struct. Surv. 2009, 27, 311–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, I.; Kim, J.I. Special Issue on BIM and its Integration with Emerging Technologies. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 5368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banfi, F. Virtual Heritage. Dalla Modellazione 3D All’HBIM e Realtà Estesa; Maggioli Editore: Milano, Italy, 2023; ISBN 8891661937/9788891661937. [Google Scholar]

- Mansuri, L.E.; Patel, D.A.; Udeaja, C.; Makore, B.C.N.; Trillo, C.; Awuah, K.G.B.; Jha, K.N. A Systematic Mapping of BIM And Digital Technologies for Architectural Heritage. Smart Sustain. Built Environ. 2022, 11, 1060–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullini, M. Accuracy Measurement of Automatic Remeshing Tools, 3D Digital Models. Accessibility and Inclusive Fruition. Disegnarecon 2024, 17, 10.1–10.14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pozzoli, S.; Bonazza, M.; Werner Villa, S. Autodesk. Revit 2026 per l’Architettura. Guida Completa per la Progettazione BIM. Strumenti Avanzati, Personalizzazione Famiglie, Modellazione Volumetrica e Gestione Progetto; Tecniche Nuove: Milano, Italy, 2025; ISBN -10 884814909X, ISBN-13 978-884814909. [Google Scholar]

- GUIDA ALLE NORME PER LE COSTRUZIONI DIGITALI LA PARTE 0 DELLA UNI 11337. Available online: https://www.uni.com/wp-content/uploads/BrochureBIM2024-1.pdf (accessed on 25 January 2026).

- Rossi, A. The Façade of Paolo Soleri’s Solimene Factory. Nexus Netw. J. 2017, 19, 503–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karmazyn, H. Dal Modello Sperimentale Al Modello Matematico. Graduate Thesis, University of Campania Luigi Vanvitelli, Aversa, Italy, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Rossi, A.; Palmero, L.; Palmieri, U. De la digitalización laser hacia el H-BIM: Un caso de estudio | From laser scanning to H-BIM: A case study. EGA 2020, 25, 182–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, A.; Giner, S.L.; Gonizzi Barsanti, S. Digital Twins for Contemporary Restoration of the Solimene Factory. In Contemporary Heritage Lexicon; Springer Tracts in Civil Engineering; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 249–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardellicchio, L. Building organic architecture in Italy: The history of the construction of the Solimene Ceramics Factory by Paolo Soleri in Vietri sul mare (1952-1956). Constr. Hist. 2017, 32, 83–104. [Google Scholar]

- Diara, F.; Rinaudo, F. Building Archaeology Documentation and Analysis through Open Source HBIM Solutions via NURBS Modelling. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2020, XLIII-B2-2020, 1381–1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Lu, Y.; Peh, L.C. A Review and Scientometric Analysis of Global Building Information Modeling (BIM). Reserarch in the Architecture, engineering and Construction (AEC) Industry. Buildings 2019, 9, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, A.; Palmieri, U. From the Survey to the Digital Construction Site. In Digital Modernism Heritage Lexicon; Bartolomei, C., Ippolito, A., Helena, S., Vizioli, T., Eds.; Springer Tracts in Civil Engineering; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 947–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banfi, F.; Azzolini, A.M. Shaping Digital Architects dal CAD e BIM Alla Rappresentazione Interattiva del Progetto Tramite Linguaggi di Programmazione Visuale Santarcangelo di Romagna (RN); Maggioli Editore: Milano, Italy, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Cardellicchio, L. Building Organic Architecture in Italy. CHS J. 2017, 32, 83–104. [Google Scholar]

- Brusaporci, S. Digital Innovations in Architectural Heritage Conservation: Emerging Research and Opportunities; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Bianchini, C. Dal BIM all’H-BIM: Una questione aperta. In Bolognesi. Brainstorming BIM. Il Modello Tra Rilievo e Costruzione; Maggioli: Santarcangelo di Romagna, Italy, 2017; pp. 22–31. ISBN 9788891622518. [Google Scholar]

- Radanovic, M.; Khoshelham, K.; Fraser, C. Geometric accuracy and semantic richness in heritage BIM: A review. Digit. Appl. Archaeol. Cult. Herit. 2021, 19, e00166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tata, A. Il Computational Design per l’HBIM. Procedure per la Modellazione HBIM del Patrimonio Architettonico; PVBLICA: Alghero, Italy, 2023; pp. 105–117. ISBN 9788899586348. [Google Scholar]

- Brumana, R.; Della Torre, S.; Previtali, M.; Barazzetti, L.; Cantini, L.; Oreni, D.; Banfi, F. Generative HBIM modelling to embody complexity (LOD, LOG, LOA, LOI): Surveying, preservation, site intervention-the Basilica di Collemaggio (L’Aquila). Appl. Geomat. 2018, 10, 545–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaiani, M.; Garagnani, S.; Gaucci, A. Archaeo BIM Theory, Processes and Digital Methodologies for the Lost Heritage; Bononia University Press: Bologna, Italy, 2021; 200p, ISBN 8869237397. [Google Scholar]

- Attenni, M.; Rossi, M.L. HBIM Come Processo di Conoscenza Modellazione e Sviluppo del Tipo Architettonico; Franco Angeli Editore: Milano, Italy, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Gonizzi Barsanti, S.; Guagliano, M.; Rossi, A. Digital (Re)Construction for Structural Analysis. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2023, XLVIII-M-2-2023, 685–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heesom, D.; Boden, P.; Hatfield, A.; Rooble, S.; Andrews, K.; Berwari, H. Developing a collaborative HBIM to integrate tangible and intangible cultural heritage. Int. J. Build. Pathol. Adapt. 2021, 39, 72–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo Turco, M.; Giovannini, E.C.; Tomalini, A. Parametric and Visual Programming BIM Applied to Museums, Linking Container and Content. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2022, 11, 411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Carlo, L.; Paris, L. Le Linee Curve per l’Architettura e il Design; Franco Angeli: Milano, Italy, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Cipriani, L.; Cabezos Bernal, P.M. 3D Digital Models. Accessibility and Inclusive Fruition. Disegnarecon 2024, 7, 32. [Google Scholar]

- Rudin, W. Principal of Mathematical Analysis, 3rd ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1976; 342p. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.; Zou, Y. Research hotspots and trends in heritage building information modeling: A review based on CiteSpace analysis. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2022, 9, 394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rausch, C.; Haas, C. Automated shape and pose updating of building information model elements from 3D point clouds. Autom. Constr. 2021, 124, 103561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.