Abstract

This paper examines the role of generative AI in contemporary craft ecologies, with a focus on Italy’s artisanal and design ecosystems. Rather than framing AI as a threat to heritage or merely a tool for efficiency, we propose that AI can be a collaborator within hybrid intelligences that extend craftsmanship, rather than replace it. Drawing on posthumanist and more-than-human design perspectives, we conceptualize hybrid intelligence as a relational infrastructure for co-design among humans, materials, and computational systems. Through a literature review and ten expert interviews with designers, artisans, curators, engineers, and scholars, we identify tensions around authorship, authenticity, standardization, ethics, craft heritage, and data cultures. Speculative scenarios project hesitant futures, balancing risks of homogenization with opportunities for resilience. The contribution of this paper is threefold. First, it proposes a conceptual map of hybrid intelligence for craft and heritage contexts. Second, it offers situated insights into Italian craft imaginaries based on expert perspectives. Third, it demonstrates a methodological approach that combines thematic analysis with speculative futuring.

1. Introduction

This paper develops the concept of hybrid intelligence as a relational infrastructure for co-design between humans and artificial intelligence (AI) in craft and design ecologies. Historically, craft practices have continually evolved alongside technological transformation—from pre-industrial artisanal workshops [1] to the mechanization processes of the First and Second Industrial Revolutions [2]. Over the last two decades, CNC fabrication, additive manufacturing, parametric modeling, and open source making cultures have reshaped the epistemologies of making.

Within this historical continuum, hybrid intelligence can be understood as an extension of digital manufacturing logics, in which computational systems participate in interpretation, experimentation, and cultural transmission. Recent advances in generative AI mark a further infrastructural shift, making algorithmic systems increasingly present within contemporary craft ecologies. These systems do not operate in isolation, but become entangled with existing practices, tools, and material knowledge.

The technological shifts redefined labor, authorship, and modes of knowledge transmission, reshaping the relationship between makers, tools, and materials [3]. Where industry largely celebrates AI for its capacity to optimize workflows and scale production, craft practices remain anchored in improvisation, tacit knowledge and cultural heritage. This divide has been widely noted in studies of digital craft, which show how computational systems privilege efficiency while makers prioritize material understanding and experiential judgment [4].

Within design research, this convergence has been described as hybrid or computational craft, where digital techniques augment rather than replace embodied expertise [5]. Generative AI represents a further step in this trajectory by intervening in domains traditionally associated with creativity, interpretation, and material judgment [6,7], including foundational approaches to computer vision and machine intelligence [8]. Rather than framing AI as a replacement for artisanal expertise, we argue that it can operate as a collaborator. In this sense, AI resonates with accounts of tools as “mirror technologies” that reflect and extend skilled practice while preserving human agency [3,9]. This perspective extends more-than-human approaches to participatory design, positioning AI not as an external agent but as part of a situated network of humans, materials, and computational technologies that together shape craft futures [10]. In this sense, generative AI can be seen as the latest stage in a long historical continuum in which new technological regimes—mechanical, industrial, digital, and now algorithmic—reshape the cultural, material, and epistemic foundations of making.

Craft provides a fertile arena for exploring these questions. Rooted in embodied skill, material dialogue, and community traditions, artisanal practices stand as counterpoints to mass production. Revivals of craft in Italy and beyond—driven by localism, sustainability, and renewed appreciation of material culture—demonstrate the fragility and vitality of these knowledge systems [11]. Italy represents a significant site for investigating the encounter between AI and craft, as its productive landscape is characterized by “craft-based industrial districts” [12,13,14]. These ecologies combine artisanal knowledge, design culture, and small–medium manufacturing in territorially embedded forms of production. Within this context, craftsmanship is not only a technical competence but also a system of cultural transmission, identity, and value creation. Its dense networks of artisanal workshops and long-standing craft traditions form a cultural infrastructure. The internationally recognized Made in Italy culture—characterized by the integration of craftsmanship, design sensibility, and industrial innovation—has been extensively documented. Historically, this context resonates with Cipolla’s analyses, which show how craftsmanship, localized production, and technological adaptation have long shaped socio-economic development [15]. His work shows that artisanal knowledge is a collective and historically rooted form of intelligence, the one that existed and evolved long before today’s digital automation. This perspective frames AI not as a rupture but as part of a longer genealogy of technological mediation in Italian craft ecologies. Historic manufacturing districts in Veneto, Lombardy, and Emilia-Romagna exemplify this synthesis by fostering spatial and social proximity among artisans, small and medium enterprises (SMEs), suppliers, and designers [12]. Italian craft and industry have long co-evolved, producing hybrid models of cultural production [13,16]. This historical and territorial specificity makes Italy a privileged site for observing how AI becomes entangled with craft heritage, identity, and local knowledge ecosystems.

Contemporary artistic traditions further offer critical perspectives for understanding hybrid intelligence. From a post-digital, computational, and craft-based approach, these traditions have long explored the entanglements between humans, tools, and algorithms, demonstrating how creative practices serve as sites of critique, resistance, and experimentation. Integrating these trajectories reinforces the view of AI not only as a technical system but also as a cultural and aesthetic agent embedded within creative ecologies. This perspective aligns with foundational work in heritage studies, where scholars such as Lowenthal and Choay emphasize heritage as a process of interpretation, reinvention, and transmission [17,18]. Understanding AI-driven craft within this lens foregrounds not only technological capability but also the evolving ways in which cultural memory is curated and transformed.

The study is guided by the following Research Questions:

- RQ1. How do Italian craft practitioners perceive the influence of generative AI on the authenticity and cultural value of artisanal heritage?

- RQ2. What forms of hybrid intelligence emerge when AI interacts with embodied skill, material agency, and traditional craft processes?

- RQ3. How might generative AI contribute to, or disrupt, the preservation and transmission of cultural memory within Italian craft traditions?

This conceptual approach aligns with the journal’s scientific orientation by addressing AI not only as a technological artefact but as an emerging cultural infrastructure within heritage management. Generative AI systems influence processes traditionally examined in ICT for Cultural Heritage—digitization, archiving, classification, and access—and therefore require conceptual tools capable of analyzing how these systems reshape cultural memory and craft transmission. By grounding hybrid intelligence within heritage studies and digital manufacturing, this work contributes to ongoing debates on how computational infrastructures participate in the preservation, reinterpretation, and future governance of cultural heritage through craft ecologies.

The article proceeds as follows. Section 2 introduces the theoretical framework, situating hybrid intelligence within the context of design theory, anthropology, posthumanism, heritage studies, and digital manufacturing. Section 3 presents the methodology, including the sampling strategy and the semi-structured interview protocol. Section 4 reports findings through thematic analysis of expert imaginaries. Section 5 extends these insights into speculative scenarios that explore future hybrid craft ecologies. Finally, Section 6 and Section 7 discuss the contributions and implications of this work for cultural heritage, design research, and responsible human–AI collaboration.

2. Theoretical Framework

This section introduces the theoretical framework of the study, drawing on perspectives from design theory, anthropology, posthumanism, digital manufacturing, and heritage studies. While these traditions employ different vocabularies, they share a concern for how humans and technologies co-shape practices over time. In the context of craft, these perspectives help illuminate making as a relational process that emerges through gestures, materials, and tools, rather than as an isolated act of production. This framework grounds hybrid intelligence in the concrete realities of how artisans learn, remember, and work within culturally situated practices.

Posthumanism challenges the assumption that creativity and authorship are exclusively human, emphasizing instead distributed forms of action across humans, tools, materials, and environments [19,20,21,22]. In this paper, we use “posthumanism” to refer to approaches that understand creativity and agency as emerging through relations rather than residing in individuals alone. From this perspective, intelligence and creativity arise through intra-actions—relational entanglements through which meanings, materials, and agencies co-constitute one another [22]. Here, “intra-action” indicates that agency is not pre-given but emerges through ongoing relationships among human, material, and computational actors.

This relational understanding of agency is especially relevant to craft and heritage contexts, where knowledge develops through sustained interaction between bodies, materials, and tools. Applying a posthuman lens allows AI to be analyzed not as an external instrument, but as one participant within evolving networks of practice. This framing provides the conceptual basis for understanding hybrid intelligence as a relational ecology grounded in practice.

David Pye’s concept of the workmanship of risk emphasizes the uncertainty and variability, as well as the situated judgment, characteristic of traditional craft [23]. Each object emerges through improvisation, direct material engagement, and embodied skill. By contrast, AI systems typically privilege precision and repeatability. Juxtaposing these logics exposes a central question for hybrid practice: how might AI sustain creative risk without erasing the unpredictability that gives craft its value?

Richard Sennett’s notion of the mirror tool suggests a possible answer [3]. Mirror tools extend and reflect human capacities. Applied to AI, this idea positions algorithms as amplifiers of tacit knowledge, capable of handling repetition, offering alternatives, or visualizing possibilities while preserving the artisan’s interpretative agency. This perspective aligns with historical analyses showing how artisanal knowledge evolves alongside technological change.

Lucy Suchman’s work on situated collaboration adds a critical dimension, reminding us that technologies shape the contexts in which they operate and vice versa [24]. In craft settings, this means that AI must support rather than override artisanal authorship and creativity. While Giaccardi and Redström’s notion of more-than-human design reframes participation as an ongoing negotiation among human and non-human actors [10]. In practical terms, this means recognizing materials, tools, and computational systems as active participants in design processes. In craft ecologies, this implies that AI acts as a cultural agent embedded within material and ecological entanglements.

Heritage studies add another essential layer. Lowenthal conceptualizes heritage as a dynamic process of selective interpretation rather than a fixed archive [18]. Applied to AI, this perspective highlights how computational tools participate in curating cultural memory, influencing what is preserved, how it is represented and how it circulates. Within craft, this raises important questions about authorship, community control and the representation of embodied knowledge. Generative AI can be considered part of cultural heritage insofar as it shapes the processes through which heritage is curated, transmitted and reimagined. Datasets trained on craft archives, pattern repertoires and material gestures become new forms of cultural memory; models that generate or classify craft-related outputs participate in defining what is preserved and what becomes visible or forgotten. In this sense, AI systems operate as algorithmic heritage infrastructures: they codify, filter and redistribute cultural knowledge, thereby influencing future access, interpretation and fruition. Recognizing AI as part of the heritage ecosystem allows us to understand its dual role—as a potential threat to embodied forms of knowledge, and as a tool capable of supporting community-driven preservation and reinterpretation. Therefore, the question is not whether AI substitutes craft, but how it intervenes in the cultural mechanisms through which craft knowledge is transmitted, legitimized and transformed.

Building on work in HCI and design research, studies by Rosner [25], Devendorf and Rosner [26], and Sreenivasan and Suresh [27] show how digital fabrication reshapes authorship, care, and improvisation in making. Liu et al. [5] propose hybrid craft as a framework for revitalizing traditional practices through computational methods, noting both opportunities and risks. Related contributions from Tironi et al. [28], Jönsson and Lenskjold [29], and Seghal and Wilkie [30] foreground speculative, participatory, and ethical dimensions of emerging technologies.

Building on Bennett’s notion of heritage algorithms, we extend the term to describe contemporary algorithmic systems that operate on heritage-related datasets and participate in curatorial, archival, and governance processes [31]. In this paper, heritage algorithms refer to computational systems that learn from, classify, or generate patterns derived from cultural memory embedded in craft archives, design repertoires, material gestures, or community-generated records. These systems act as mediators of cultural memory by filtering, amplifying, or omitting patterns, thereby influencing what becomes visible, reproducible, or transmissible as cultural heritage. This definition draws on critical algorithm studies and heritage theory, treating computational models as cultural agents within broader heritage ecologies. This emphasizes that digital representations of gestures, forms, and material behaviors are always embedded in social, historical, and territorial contexts. Moreover, authentic intelligence denotes the interpretive, imaginative, and ethical capacities of human creators that cannot be reduced to computation.

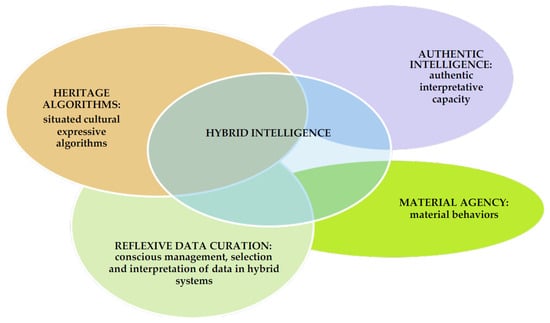

According to Arzberger, Lupetti, and Giaccardi’s concept of reflexive data curation, hybrid intelligence can be understood as a co-learning process in which uncertainty, bias, and friction become productive resources for revealing tacit knowledge and cultural assumptions [32]. This resonates with Giaccardi and Bendor’s vocabulary, which frames AI collaboration as a situated practice distributed across cultural, social, and technical networks [33]. Within hybrid craft ecologies, workshops become algorithmic sites—spaces where artisans, materials, and AI systems negotiate meanings, biases, and creative directions. While more-than-human design highlights the inclusion of non-human agents within design processes, such as materials, technologies and environments. Posthumanism extends this stance by questioning humanist assumptions in design and reframing authorship, accountability, and decision-making as distributed across human and non-human actors. Hybrid intelligence specifically refers to the negotiated interplay between human intuition, material agency, and computational systems. AI can extend practice, yet its integration risks standardization, disembodiment, and the erosion of agency. Figure 1 visualize this conceptual ecosystem, illustrating hybrid intelligence as the interplay among four pillars: Heritage Algorithms, Authentic Intelligence, Material Agency, and Reflexive Data Curation.

Figure 1.

Conceptual map of Hybrid Intelligence. Hybrid Intelligence—co-created between humans and algorithms in craft contexts—is supported by four pillars: Heritage Algorithms (cultural data practices), Authentic Intelligence (human judgment), Material Agency (active materials), and Reflexive Data Curation (critical data management).

Finally, by grounding hybrid intelligence within Italian craft ecologies, characterized by localized production, embodied knowledge, and intergenerational transmission, this framework emphasizes that AI’s role in craft is culturally specific. Hybrid intelligence emerges not as a universal model but as a situated, ethically complex configuration shaped by material, territorial, and historical continuities.

Relevance to Cultural Heritage and CH Management

Heritage, as emphasized in cultural heritage scholarship, is approached as a dynamic and interpretive process mediated through social, material, and technological practices [19]. Generative AI introduces new forms of mediation by influencing how artisanal gestures, traditional forms, and local knowledge are archived, classified, and recombined. Within ICT for cultural heritage, AI-driven systems already support digitization workflows, metadata structuring, and adaptive curation.

Hybrid intelligence extends these applications by positioning artisans and cultural practitioners as co-curators of heritage algorithms. These culturally situated computational practices enable communities to decide what craft knowledge is preserved, how it is represented, and how it circulates across digital infrastructures.

Craft must be understood not simply as a set of manual skills but as a culturally embedded living system of transmission, identity and continuity—precisely what heritage studies define as intangible cultural heritage. As Lowenthal notes, heritage is a process of intergenerational negotiation, while Choay describes it as a cultural invention that stabilizes collective meaning [17,18]. Craft embodies both dimensions: it conserves gestures, techniques and material sensibilities while reinventing them according to present needs. Positioning craft within heritage studies clarifies that what is at stake is not only the artisan’s identity but the historical and cultural value of a practice that structures social memory, territorial identity and material culture.

For Italian craft ecologies—rooted in localized material cultures and intergenerational transmission—hybrid intelligence offers both opportunities and risks. It can facilitate community-driven digital archives, support new forms of experiential cultural heritage, and broaden accessibility to intangible practices. At the same time, it raises concerns regarding authorship, commercial exploitation, and cultural homogenization.

Situating this research within ICT for cultural heritage therefore provides a lens through which to analyze AI not only as a production tool but as a socio-technical force shaping memory, identity, and cultural continuity.

3. Context, Materials, and Methods

The decision to focus on the Italian context is methodologically grounded. Italy hosts one of the densest and historically rooted craft ecosystems in Europe, where artisanal knowledge, design culture, and small–medium manufacturing are deeply intertwined. The industrial districts and cultural identity associated with the Made in Italy tradition position craft as a living infrastructure of social, economic, and territorial value. For this reason, Italian practitioners’ imaginings of AI cannot be considered generic: they emerge from long-standing traditions of material sensibility, intergenerational transmission, and hybrid craft–industry models. Focusing on this context, therefore, allows us to analyze how attitudes toward AI emerge within a culturally specific ecology, and how local values, concerns, and expectations inform broader debates on hybrid intelligence.

The study adopts a qualitative, interpretivist approach situated at the intersection of design anthropology and craft studies. Its methodological design was guided by three research questions introduced in the previous section: (RQ1) how do Italian craft practitioners perceive the influence of generative AI on the authenticity and cultural value of artisanal heritage; (RQ2) what forms of hybrid intelligence emerge when AI interacts with embodied skill, material agency, and traditional craft processes; and (RQ3) how might generative AI contribute to, or disrupt, the preservation and transmission of cultural memory within Italian craft traditions. These questions informed both the sampling strategy and the development of the semi-structured interview protocol. Our goal was to explore how Italian experts in design and craftsmanship imagine and negotiate the role of AI in their practices. To do so, we combined a critical literature review with semi-structured interviews of experts. Interview excerpts are presented as integral components of the analysis, illustrating how participants’ words shaped the development of themes and guided our understanding of hybrid intelligence in craft ecologies.

3.1. Sampling Strategy and Interview Protocol

The study draws on ten in-depth interviews with practitioners who occupy key positions within Italian craft and design ecologies. While still modest in size, this example is consistent with qualitative, exploratory research, where analytical depth rather than numerical representativeness is the primary aim. In line with Malterud et al.’s notion of “information power”, the diversity, expertise and centrality of the ten participants provide substantial conceptual richness for identifying tensions and imaginaries around hybrid intelligence [34]. The goal of this pilot study was therefore not to generalize findings to all craft practitioners, but to surface situated insights capable of informing broader future research.

Participants were recruited through purposive sampling, selected for their expertise at the intersection of craft, design, and technology in the Italian scenery. The sample included ten experts. This diversity was intended to capture multiple perspectives on how AI intersects with artisanal practices and cultural heritage. While not statistically representative, the sample reflects a cross-section of influential voices in the Italian design and craft ecosystem.

To contextualize emerging insights, short biographical profiles were compiled for each participant. The sample is geographically localized in Northern Italy, particularly in the regions of Lombardy and Veneto, which are historically associated with dense craft and industrial districts. Participants’ backgrounds include design, architecture, engineering, craft apprenticeship, and material research, with 7–30 years of experience. This geographically and culturally situated sample provides a culturally dense environment through which imaginaries of AI are articulated. To avoid gendered assumptions, we refer to participants using “they.”

The sample includes the following professional profiles:

- Curator and Cultural Strategist—Independent curator with extensive international experience in contemporary design and emerging production cultures.

- Research-Driven Designer—Designer whose work integrates material exploration, anthropological approaches, and process-based experimentation.

- Master Artisan and Workshop Co-Founder—A craftsperson leading an experimental studio blending traditional knowledge with selective technological adoption.

- Industrial Designer and Creative Consultant—Designer active internationally, working across product design, creative direction, and consultancy.

- Manufacturing and Industry 4.0 Expert—Academic and advisor specializing in sustainable and digital manufacturing for SMEs.

- More-than-Human Design Scholar—Researcher focusing on posthumanism, hybrid intelligences, and data curation.

- Craft-Oriented Designer and Material Reuse Researcher—Designer working with manual processes, repair cultures, and small-scale sustainability, particularly woodwork.

- Emerging Material-Focused Designer—Young practitioner exploring sustainable materials and speculative reinterpretations of cultural residues.

- Designer and Craft/Industry Researcher—Designer working across traditional crafts and contemporary design languages, analyzing how AI shapes early creative processes and systemic implications.

- Narrative-Driven Designer and Cultural Researcher—Designer exploring symbolism, material culture, and evolving aesthetic languages under emerging technologies.

These biographies clarify the diversity of perspectives and the culturally specific environments in which practitioners operate. The semi-structured interview protocol consisted of five thematic blocks aligned with the research questions:

- Current Practice and Engagement Use with Technology—Engagement with AI or digital tools; required forms of expertise;

- Authorship, Agency and Embodied Knowledge (RQ1)—Human vs. AI authorship; non-negotiable human aspects of practice;

- Human–AI Collaboration, Assistance and Augmentation (RQ2)—Opportunities and concerns; potential for AI-assisted experimentation;

- Cultural Memory, Heritage and Transmission (RQ3)—AI’s role in preserving or transforming craft knowledge; risks and reinforcements;

- Ethics, Governance and Futures—Ethical concerns; visions of responsible futures for craft and technology.

The protocol ensured consistency across interviews while allowing participants to elaborate through examples, anecdotes, and speculative reflections. Each interview lasted up to 45 min, was conducted with consent, and was transcribed verbatim.

3.2. Data Analysis and Limitations

Interviews were transcribed and coded using reflexive thematic analysis. Initial codes were generated inductively from the transcripts and then iteratively refined into thematic clusters that captured recurring tensions, values, and visions. Our analysis was informed by posthuman and participatory design perspectives, focusing on how notions of authorship, authenticity, and hybridity were articulated. In line with qualitative interpretivist approaches, participants’ voices are presented through direct quotations to foreground their conceptual framings and situated meanings. These excerpts are not treated as illustrative “examples”, but as integral components of the analytical process through which themes were constructed. Following reflexive thematic analysis, interpretation emerged from an iterative dialogue between participants’ words, researchers’ coding, and the theoretical lenses mobilized in the study.

This study should be understood as an exploratory pilot. The small sample size limits the generalizability of findings, and participants’ engagement with AI varied, with some speaking primarily from speculative or conceptual standpoints rather than from hands-on experience. Furthermore, the absence of real-time co-design sessions constrained our ability to observe embodied collaboration with AI tools. Nonetheless, the interviews offer valuable insights into the cultural imaginaries and ethical concerns that shape the integration of AI into Italian craft and design practices.

Our interpretivist stance aligns with emerging frameworks for Reflexive Data Curation [32] and Reflexive Data Practices [33], which emphasize human–AI collaboration as a site of introspection. Following this approach, we treated interviews and subsequent scenario-building as reflexive exchanges rather than neutral data-gathering exercises. The research process became a microcosmos of hybrid intelligence itself: a co-learning environment in which both researchers and participants surfaced their assumptions about authorship, authenticity, and agency in craft. This reflexive orientation guided both our coding and our speculative exploration. This pilot study adopts a speculative stance, aiming to provoke critical reflection rather than generalization. This limited sample (10) aligns with the exploratory nature of design research, where small, deeply contextual datasets are commonly employed to generate situated insights rather than statistical generalizations [35,36].

Given the localized nature of the sample, future research could benefit from cross-referencing these findings with craft and design communities in other geographical contexts. Comparative studies would allow for identifying which imaginaries of AI are culturally specific and which patterns may hold more broadly across creative ecologies.

The thematic analysis also informed the construction of the speculative scenarios presented in Section 5. Drawing on speculative and critical design approaches, tensions emerging from the interviews were translated into future-oriented narrative prompts. Each scenario corresponds to a specific constellation of themes: for example, discussions about AI as an “assistant” or “mirror tool” informed Scenario 1, while concerns regarding dataset provenance and heritage transmission shaped Scenario 2. The speculative phase was therefore not detached from the empirical material but functioned as an extension of it, transforming practitioner insights into situated projections of possible craft ecologies shaped by hybrid intelligence [37,38].

4. Results: Interpreting AI in Italian Craft Ecologies

The interviews reveal a complex and often ambivalent imaginary on AI in Italian craft, encompassing both possibilities and threats. Instead of treating these responses descriptively, we interpret how each perspective aligns with, extends, or diverges from our theoretical framing of hybrid intelligence, mirror tools, workmanship of risk, and more-than-human design. We also discuss the practical feasibility of these imaginaries and synthetize imported concepts into a coherent framework.

The imaginaries articulated by participants both resonate with and resist theoretical framings. Tensions such as tradition vs. innovation, authorship vs. automation, and preservation vs. standardization emerge as central findings. As a pilot, our role is not to resolve these tensions, but to surface them as a foundation for participatory design inquiry.

4.1. Authorship, Agency and Standardization

Master artisan insists that “Our motto is Thought by Hand, meaning that behind every project, there is a thought executed by skilled hands who know their trade and ultimately take ownership of the knowledge of the production process”. For them, embodied interpretation—rather than output generation—remains central to artisanal identity. This concern becomes explicit when they warn that “the risk in replacement is to make the product mediocre”, expressing anxiety that AI could erode judgment and responsibility in making.

Industrial designer echoes this position, arguing that the machine must not dictate the design: “I hope artificial intelligence in artisanal products plays no role at all”, voicing fears that AI may accelerate cultural flattening. Master artisan reinforces this view by grounding authenticity in “thought by hand,” emphasizing authorship as inseparable from manual interpretation.

These perspectives highlight a shared resistance to AI when it is perceived as a co-creative or directive agent. Across interviews, concerns about homogenization are widespread, particularly in relation to regional aesthetics and variability. Participants suggest that without mechanisms to preserve local specificity, AI adoption may be rejected in traditional craft settings.

Interpreted through theory, these positions resonate with Suchman’s notion of situated action [24], in which technology must remain contextual and subordinate to human agency. They also align with Sennett’s concept of the mirror tool, where technology reflects and supports human intention without erasing authorship [3]. At the same time, they diverge from more-than-human design approaches that position AI as a co-actor [10], indicating a clear boundary condition for hybrid intelligence: AI may support craft practice, but not replace or redefine artisanal judgment.

This boundary is further underscored by references to Pye’s workmanship of risk, which values variability, improvisation, and situated decision-making [23]. In practical terms, participants’ reflections suggest that hybrid intelligence in craft must be framed as bounded collaboration rather than full co-design. While Manufacturing and Industry Expert argues that “technology standardizes interfaces, not creativity”, emphasizing human responsibility in preventing homogenization [39], this optimism is tempered by structural constraints. Craft SMEs often lack the digital literacy and infrastructure needed to ensure creative autonomy, making uncritical adoption risky. Participants note that automation has already displaced heritage practices—such as machine embroidery reducing demand for hand-stitching—raising concerns that hybrid intelligence may accelerate cultural loss if governance and support mechanisms are absent.

4.2. AI as Assistant or Mirror

Several participants envision AI as supportive. Industrial designer welcomes AI if “It can be seen as a tool. I have to say that I don’t feel threatened, not yet. In my opinion and my personal experience, its strength will lie in its ability to give back to the designer the most precious asset: time. How? Automating the visualization of projects allows you to focus on the design rather than the presentation, which is often crucial in a client’s evaluation of an idea.” This aligns with Sennett’s mirror tool, where AI automates repetitive labor and amplifies tacit skills. Designer and Craft/Industry researcher describes AI as helpful in early ideation but clearly states that it cannot replace iterative design reasoning: “AI works very well as a brainstorming partner, but it shouldn’t be treated as the final design solution”. Research driven designer envisions intelligent kilns capable of “setting new parameters” and recognizing firing stages, enabling new interactions between material and maker. These examples extend Pye’s workmanship of risk, suggesting AI can create new spaces for experimentation. “Perhaps with a co-pilot, artisans would improve their performance”, argues Manufacturing industry expert. Craft Oriented designer stresses what AI could be very meaningful for SMEs: “The hardest part is not cutting or designing, it’s promotion. AI can really help by generating media and managing business communication”. Yet feasibility depends on cost and accessibility. Intelligent kilns or AI-driven project management platforms are currently beyond the financial reach of many artisans. For hybrid intelligence to succeed, incremental and affordable interventions—such as open-source software or shared infrastructure in craft cooperatives—are necessary.

4.3. Ethical Design and Cultural Memory

Curator and Cultural Strategist frames ethics as a matter of human responsibility, stating: “AI reflects us—it’s our mirror, and it’s up to us to decide what we see in it”. The same participant further emphasizes that “it’s not about the tool—it’s about who controls the context”, drawing attention to governance, responsibility, and institutional framing rather than technical capability alone.

Related concerns emerge in interviews with researchers and designers working at the intersection of craft and computation. More-than-human Design Scholar highlights the need for “curation of data that reflects the laboratory practice of craftsmanship”, arguing that programming and improvisation can coexist when data practices remain situated. Other participants similarly envision AI as a potential custodian of cultural memory. Research-Driven Designer suggests that AI could help designers and artisans “scale sustainable artisanal practices into more sustainable industrial ones” by supporting networks and production processes. Narrative-Driven Designer expands this view, noting that AI enables multiple, coexisting futures: “We are looking at many possible futures, which will likely coexist in different niches: large companies that can mass-produce infinite variations of fast-fashion outfits or disposable furniture; other companies that will extract and interpret data to make their production greener and more efficient; others experimenting with different, distributed, local models supported by AI’s computing power; techno-punk poets showing us that the boundary between organic and inorganic beings is a cultural construct and that, in fact, we have always all been everything, all at once”.

By contrast, Master Artisan expresses clear skepticism, prioritizing embodied skill over digital archives: “AI cannot replace craftsmanship; excellence cannot be achieved with means accessible to all”. This divergence reveals a generational and epistemic gap. While curators and researchers are more inclined to imagine AI as a cultural repository or mediating infrastructure, artisans and makers articulate concerns about the loss of embodied nuance and situated judgment. Practically, this suggests that the feasibility of heritage-oriented AI systems depends on co-designing archival and data practices with craft communities to avoid disembodiment and cultural abstraction.

Interpreted analytically, these positions resonate with Suchman’s notion of situated action [24], where ethical outcomes depend on context and control structures rather than on tools alone. They also echo Sennett’s mirror tool [3], insofar as AI is framed as reflecting human values and intentions rather than determining them. At the same time, the data complicate more-than-human ethics that distribute agency evenly across humans and technologies [10], suggesting instead that participants place strong normative boundaries around authorship and responsibility.

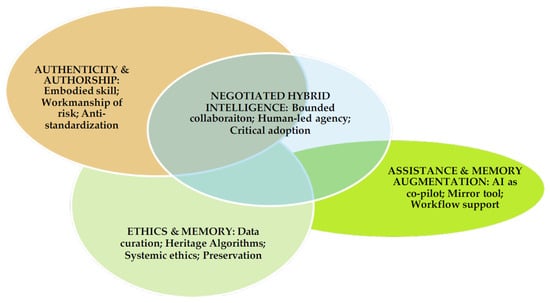

The ambivalence expressed across these interviews—oscillating between fascination and resistance—can be read through the lens of reflexive data curation. Moments of discomfort with automation or insistence on manual authorship function as forms of auto-confrontation, where practitioners critically assess what must remain human. Speculative optimism, by contrast, reflects a change in perspective that reimagines AI as a cultural participant. Rather than contradictions to be resolved, these tensions indicate a reflexive human–AI practice already underway. As one Emerging Material–Focused Designer notes, “more than the final product, these projects focused on the collaborative process—understanding how to integrate AI within design and craft workflows”. On this point, Figure 2 visualizes how participants’ perspectives cluster into three thematic domains, showing that hybrid intelligence emerges at their intersections as a situated negotiation between embodied skill, technological assistance, and ethical-cultural concerns. Taken together, these perspectives address RQ1 by showing that AI is largely perceived not as a replacement for craft knowledge, but as a contested presence that challenges authorship, responsibility, and embodied expertise.

Figure 2.

Thematic clusters from interviews. This figure visualizes the three main themes emerging from the interviews—Authorship and Authenticity, Assistance and Augmentation, and Ethics and Memory—and their intersections, illustrating how participants’ perspectives overlap across creative, technical, and ethical dimensions of AI in craft. At the center is Negotiated Hybrid Intelligence, the emergent conceptual synthesis showing that Italian craft ecologies position AI not as a seamless collaborator but as a situated negotiation between embodied skill, ethical concerns, and selective adoption of assistive technologies.

4.4. Conclusion of Findings

The conclusions presented here should be read considering the exploratory and qualitative nature of this study. Rather than offering generalizable claims, they synthesize patterns, tensions, and imaginaries that emerged consistently across the interviews and were interpreted through the theoretical framework outlined earlier. In this sense, the conclusions are grounded in the empirical findings while extending them through established literature on craft, heritage, and human–AI collaboration.

Across the interviews, participants articulate positions that alternately align and diverge, forming a vibrant and multifaceted discourse. The Curator and Cultural Strategist stresses that the growing presence of AI in design is primarily a shift in accessibility, noting that while it once belonged to “highly specialized professionals,” it is now “within reach for many,” and that its ethical effects depend on the choices humans make, since “the issue starts with us.” The Research-Driven Designer sees AI as part of a broader technological evolution, comparing its emerging role in design to the introduction of computers and arguing that designers must first “understand the tool” before exploiting its creative potential. The Designer and Craft/Industry Researcher highlights AI’s effect on creative processes, observing that it can generate numerous early hypotheses but also “pull the work in new directions”. Meanwhile, the Narrative-Driven Designer and Cultural Researcher warns that current uses of AI risk prioritizing polished imagery over critical or environmental concerns, pointing out that designers increasingly rely on AI to produce “beautiful renders” without questioning impacts and implications. The Craft-Oriented Designer and Material Reuse Researcher highlights practical constraints for small producers, noting that AI cannot yet interpret materials in situ and that only “a person can do” certain forms of tacit evaluation. In contrast, the Manufacturing and Industry 4.0 Expert views AI as an opportunity to strengthen organizational capacities in craft SMEs, arguing that a lack of data culture and project management limits their competitiveness. Finally, the Emerging Material-Focused Designer situates AI within broader economic shifts, expressing concern that declining neighborhood craft practices make it harder for designers to maintain a connection to making. They also warn that AI may exacerbate this distance by offering “contaminated” viewpoints drawn from external sources. Together, these perspectives reflect a field negotiating between optimism, caution, and structural limitations in imagining what AI can or should become within Italian craft.

Feasibility requires addressing infrastructural and cultural barriers: Craft SMEs need affordable tools and digital literacy; artisans require assurances of authorship and authenticity; and communities must retain control over data. Imported concepts, such as the mirror tool, workmanship of risk, and heritage algorithms, converge in a sharper synthesis here: hybrid intelligence is less a smooth collaboration than a situated negotiation, where feasibility depends on respecting artisanal boundaries, enabling accessibility, and embedding ethical governance.

Hybrid intelligence in Italian craft emerges as promising but precarious. It aligns with theoretical notions of reflective partnership and cultural preservation but diverges when fears of homogenization and loss of authorship dominate. Feasibility depends on incremental, affordable, and community-controlled adoption strategies. Far from universal, hybrid intelligence is always situated, partial, and contested—a condition that design research must embrace rather than resolve.

These findings recalibrate the theoretical model by emphasizing hybrid intelligence as negotiated and contingent. While our framework initially conceived AI as a co-designer within more-than-human assemblages, the Italian case underscores the need to temper this view with a stronger attention to asymmetries of agency, access, and authorship. Artisans’ skepticism toward AI as a creative collaborator reveals that participation is not just a matter of inclusion but of boundary work—where practitioners continuously define what must remain human, embodied, and situated. For participatory design, this implies a methodological shift from designing with AI toward designing the conditions for coexistence—dialogue, governance, and critical reflection across human and computational actors. In this sense, the empirical evidence transforms hybrid intelligence from an aspirational framework of collaboration into a reflexive practice of negotiation, care, and selective alignment among heterogeneous intelligences. As Industrial Designer puts it, “Craftsmanship is placed between traditional creativity and practical utility, but what in my opinion makes it unique is its creator, and the manual skill and interpretation; therefore, I believe we would have to invent another word if AI entered the craft process. I am for keeping the “past from the future” divided by the hands of the artificial mind”. These insights invite a reorientation of hybrid intelligence not as a destiny of mechanic integration, but as an ongoing cultural and material negotiation—one that foregrounds human judgment, craft, and care as the loci through which AI must be critically situated and continually redefined. These tensions directly inform RQ2, as they reveal how generative AI destabilizes existing boundaries between making, authorship, and cultural transmission in craft contexts.

5. Speculative Future of Hybrid Craftsmanship

The speculative scenarios presented below are grounded in the empirical tensions that emerged during the thematic analysis. Rather than fictional projections, each scenario translates a specific cluster of practitioner concerns into future-oriented narrative form. Three tensions were particularly generative: (1) the conflict between embodied authorship and algorithmic standardization; (2) the negotiation between human skill, material agency, and AI-mediated decision-making; and (3) anxieties regarding cultural memory, dataset provenance, and the potential erosion or amplification of heritage. These tensions serve as the analytical backbone for the scenarios that follow, each of which extrapolates a distinct trajectory from the empirical findings.

Our approach to speculative scenarios is inspired by critical design, reflective design, and anticipatory design practices, using speculation as a means of inquiry rather than prediction [36]. Building on the findings, we extend the analysis into speculative design scenarios that connect participant imaginaries, theoretical frameworks, and practical feasibility. These futures can be read as experiments in interfacing and prototeams, where artisans, designers, and AI systems collaborate through provisional partnerships. Each scenario treats hybrid intelligence as a reflexive infrastructure unfolding within specific algorithmic sites of making. Through such speculative prototyping, we examine how uncertainty, bias, and material negotiation may become productive forces in crafting responsible human–AI futures.

Scenario 1: The AI Apprentice with Memory

Scenario 1 emerges from interviewees’ repeated characterization of AI as an “assistant”, “mirror tool”, or “sparring partner”. Participants valued AI’s ability to support ideation while expressing concern about losing authorship or craft identity. This scenario therefore explores a future in which collaborative AI tools become deeply embedded in early-stage design and craft workflows. In a small workshop, an artisan collaborates with an AI trained on regional gestures. The AI suggests forgotten methods, acting as a co-learner rather than a dictator. Table 1 clarifies how heritage algorithms support artisans as co-learners by surfacing regional gestures and forgotten techniques.

Table 1.

Key aspects of the heritage-algorithms dimension, detailing how this concept builds on existing theory, diverges from artisans’ skepticism towards digital preservation, and relies on accessible, co-created infrastructures for practical use in craft contexts.

Scenario 2: Intergenerational Craft Interfaces

Scenario 2 is informed by fears of homogenization and dataset-driven standardization expressed by multiple practitioners. Concerns regarding the opacity of training data, the loss of local specificity, and the fragility of tacit knowledge directly motivated this scenario’s exploration of heritage governance and algorithmic authorship. An augmented environment allows elder artisans and younger makers to co-design through tactile and digital means. Gestures are captured and visualized, blending oral tradition with computational mediation. Table 2, illustrates how intergenerational craft interfaces blend embodied skill, situated action, and computational mediation.

Table 2.

Key aspects of the embodied-skill dimension, showing how it builds on theories of situated action and workmanship of risk, highlights makers’ anxieties around homogenization, and identifies the conditions necessary for equitable, intergenerational integration of AI in craft.

Scenario 3: Decentralized Design Sanctuaries

Scenario 3 responds to discussions about the future of cultural memory, including the possibility that AI could both preserve and transform craft traditions. Participants questioned who will curate heritage in the future, and what forms of intelligence—human, artificial, or material—should be involved. This scenario extrapolates those reflections into a speculative ecology of post-human archiving. Networks of workshops adopt open-source AI systems to curate and remix local craft knowledge, balancing experimentation and sustainability. Table 3, highlights how distributed collaboration depends on shared governance and open infrastructures to sustain craft communities.

Table 3.

Key elements of the distributed-collaboration dimension, showing how AI as shared infrastructure intersects with questions of governance and outlining the cooperative, publicly supported models needed to keep craft communities included in AI-enabled networks.

Across these scenarios, hybrid intelligence emerges as a negotiated process. Each vignette extends a specific participant imaginary while highlighting practical conditions for adoption. Together, they show that hybrid craftsmanship requires incremental, community-driven, and ethically governed approaches. Only then can hybrid intelligence strike a balance between tradition and innovation, efficiency and authenticity, assistance and authorship.

Our scenarios highlight both potential and risk:

- AI Apprentice with Memory: Extends heritage algorithms, but risks producing disembodied archives disconnected from practice.

- Intergenerational Craft Interfaces: Supports skill transfer but may oversimplify embodied knowledge.

- Decentralized Design Sanctuaries: Democratizes AI use but risks exclusion without governance and infrastructure.

The FabCity and Europeana cases demonstrate how hybrid infrastructures already shape the governance of cultural and material knowledge internationally. These initiatives demonstrate that distributed, community-led models of digital curation and production are feasible, aligning directly with the forms of hybrid intelligence envisioned by our interviewees. They also demonstrate that similar negotiations between tradition, digitalization, and cultural agency are emerging globally, not just in the Italian context.

While these scenarios emerge directly from practitioners’ perspectives, they also resonate with international research on hybrid craft and digital heritage. Studies in Nordic design futures, East Asian craft–technology collaborations, and Anglo-American maker cultures highlight similar tensions between augmentation, authorship, and cultural continuity. Triangulating participants’ imaginaries with this broader scholarship reinforces that hybrid intelligence is not only a local negotiation but part of a wider reconfiguration of creative practices in AI-mediated environments.

6. Discussion

The findings show that encounters between AI and craft are neither fully optimistic nor entirely cautious. As researchers, we found ourselves listening to how artisans and makers articulated their work through materials, often challenging our initial assumptions about AI’s role. Participants described making as grounded in a strong material connection. Their reflections remind us that craft is not just a method of production but a way of thinking and caring through materials. Bringing these voices together highlights how and where hybrid intelligence can support makers when it respects these situated values, and where it risks distancing them from the sensory, interpretive, and improvisational aspects of their work.

If hybrid intelligence is to be understood in its full meaning, collaboration cannot occur only between human and artificial systems. Craft has always relied on a form of “natural intelligence”: the tacit wisdom of materials, ecological processes, and embodied sensory judgment. Any responsible future for hybrid craftsmanship must therefore sustain a triadic relationship among human creativity, algorithmic computation, and the material-environmental agencies that shape making. AI should not obscure these forms of natural intelligence but amplify the conditions for their continued relevance. This paper advances design research by articulating the role of hybrid intelligence in contemporary craft ecologies. Its contributions can be summarized in the following five key dimensions, from Section 6.1, Section 6.2, Section 6.3, Section 6.4 and Section 6.5.

6.1. Theoretical Contribution

We outline an initial conceptual map of hybrid intelligence as a relational infrastructure for participatory design. Building on Pye’s notion on risk [23], Sennett’s mirror tool [3], Suchman’s situated collaboration [24], Giaccardi and Redström’s more-than-human design [10], and Haraway’s sympoietic framing [21], we position AI as one participant within assemblages. Contributions from Tironi et al. [28], Jönsson and Lenskjold [29], and Seghal and Wilkie [30] further demonstrate how speculative, and ethical approaches enrich this understanding. Our contribution lies in grounding this map in culturally specific Italian craft ecologies, linking posthuman participatory design with debates on cultural heritage.

6.2. Empirical Contribution

Through interviews with ten Italian experts—designers, artisans, curators, engineers, and scholars—we offer situated insights into how practitioners envision and navigate AI in craft contexts. Their reflections reveal ambivalence: AI is seen as both a potential threat to authenticity and a powerful assistant for innovation, documentation, and preservation. Thematically, the interviews surface tensions—tradition vs. innovation, efficiency vs. authenticity, assistance vs. authorship—that illustrate the stakes of AI integration in artisanal practice.

6.3. Methodological Contribution

Methodologically, we illustrate the value of combining reflexive thematic analysis with speculative design scenarios to explore more-than-human participatory design. Thematic clusters provide grounded insights into current concerns, while speculative futures extrapolated these tensions into provocative vignettes that invite critical reflection. This dual approach offers a pathway for connecting practitioners situated accounts with imaginative explorations of possible futures.

6.4. Practical Implications

In relation to RQ3, these implications clarify how hybrid intelligence reshapes existing CH management practices, particularly in documentation, data stewardship, and institutional governance. To strengthen feasibility, we note that cooperative AI labs could be supported by regional or European Union (EU) cultural innovation funds, with governance shared through artisan-led cooperatives. Community-driven digital archives would require structures that ensure artisan control over data and decision-making. Such measures are essential to prevent appropriation and guarantee equitable access.

Cooperative AI Labs for SMEs: shared, subsidized spaces where small workshops can experiment with AI without prohibitive costs. Comparable models include the Fab City Research Labs (Barcelona, Paris) [39], which offer localized infrastructures for material experimentation and data governance. These labs demonstrate how distributed, low-cost facilities can foster responsible AI adoption among small cultural enterprises.

Funding for Community-Driven Digital Archives: Archiving gestures and techniques with artisan control, avoiding appropriation or homogenization. Analogous examples include the Europeana Craft Heritage Program and the Open Knowledge Foundation’s community-curated repositories [40], which provide open, rights-aware frameworks for digitizing cultural practices while maintaining provenance and authorship integrity.

Hybrid Curricula: Educational models that combine AI literacy with tacit craft knowledge, preparing future makers to critically negotiate human–AI collaboration. The Distributed Design Platform [41] and Ars Electronica’s Futurelab Academy offer hybrid pedagogical models that integrate computational methods with traditional craft and material cultures. These demonstrate how interdisciplinary learning environments can sustain both digital competence and embodied skill.

These proposals make the implications more feasible by connecting speculative directions with existing infrastructures and initiatives that already embody inclusive, locally grounded innovation. Future research should examine data governance models for craft communities, addressing ownership, licensing, and algorithmic accountability. Such frameworks can prevent appropriation and ensure cultural sovereignty in hybrid craft systems.

6.5. Implications for Cultural Heritage Management and ICT Practice

Although this study is exploratory, it has concrete implications for how Cultural Heritage (CH) institutions understand and govern the use of ICT systems. These implications stem from an analytical view of generative AI as a cultural infrastructure rather than a neutral tool. As heritage scholarship has long emphasized, digital systems actively shape processes of selection, interpretation, and transmission, influencing what becomes legible as heritage [17,18]. The concept of hybrid intelligence helps identify where these dynamics become institutionally significant.

A first implication concerns documentation practices for intangible cultural heritage, particularly craft. Craft knowledge is embodied, processual, and context-dependent, and therefore resists complete formalization. From an ICT perspective, this underscores the limits of automated classification and exhaustive digital recording. Hybrid intelligence reframes documentation as an interpretive rather than purely technical practice, encouraging approaches that combine audiovisual materials, contextual annotation, and reflective description, while explicitly acknowledging what remains uncapturable.

A second implication relates to the datasets used to train AI systems when they draw on heritage-related materials. Even in the absence of explicit institutional intent, datasets assembled from collections, archives, or documented practices function as infrastructural layers that shape future representations of cultural knowledge. For CH institutions, this raises familiar governance concerns from archival and collection management, including provenance, responsibility, and long-term care [42]. Treating such datasets as part of the heritage infrastructure extends existing curatorial logics to algorithmic systems without introducing new technological mandates.

Together, these implications point to the importance of participatory governance, with artisans and local communities involved in shaping datasets and AI systems. They also highlight the value of scale-sensitive approaches, favoring locally managed, modular digital tools over large, centralized platforms in order to support small workshops and community-based heritage practices. Finally, the integration of AI within CH institutions calls for hybrid professional competencies that combine digital literacy with cultural and ethical expertise. By focusing on documentation and data stewardship, this framework offers a grounded way to engage with AI as part of established institutional responsibilities, supporting a cautious and critically informed integration of ICT systems in Cultural Heritage management.

7. Conclusions

This study shows that hybrid intelligence in Italian craft ecologies is both promising and precarious. Instead of a stable or unified model of human–AI collaboration, practitioners described a field shaped by negotiation, ambivalence, and selective adoption. Across interviews, recurring tensions emerged between efficiency and authenticity, assistance and authorship, and preservation and standardization, providing the empirical basis for the conclusions.

Interviewees did not frame generative AI as a replacement for craft knowledge but as a contingent presence whose value depends on its integration within existing practices. Artisans in particular expressed concerns about homogenization, loss of embodied judgment, and erosion of authorship, while designers, curators, and researchers identified opportunities for AI to support documentation, experimentation, and communication. These positions suggest that hybrid intelligence is experienced less as seamless collaboration than as ongoing boundary work over what must remain human, embodied, and situated.

Given its qualitative and exploratory scope, this study does not aim at generalization, but at synthesizing shared imaginaries and tensions and interpreting them through established frameworks from craft, heritage, and human–AI studies. From a cultural heritage and ICT perspective, the findings support a cautious reframing of AI as a cultural infrastructure rather than a neutral tool, particularly in relation to documentation and archiving practices central to intangible heritage. The study further shows that meaningful hybrid intelligence depends not only on technical capability, but on access, governance, data ownership, and digital literacy. Responsible integration of AI in craft contexts therefore requires infrastructural and ethical design choices—such as community-controlled archives and hybrid educational pathways—rather than purely technological solutions.

Overall, hybrid intelligence in craft emerges as an evolving cultural negotiation rather than a fixed configuration. Recognizing this condition allows designers, researchers, and heritage institutions to approach AI as a situated practice that must be continually shaped, governed, and critically examined in order to support care, authorship, and cultural continuity.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: B.B.; Methodology: B.B. and M.F.; Data Collection: B.B.; Formal Analysis: B.B. and M.F.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation: B.B.; Writing—Review and Editing: B.B. and M.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was carried out with the support of the doctoral scholarship “AI for Craft Sector in Digital Transition”, issued by the Design Department and the Athenaeum of Politecnico di Milano within Course 1364.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all interview participants involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data supporting this research are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Interview excerpts cannot be shared publicly due to confidentiality agreements.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge Beatrice Bianco for conducting the interviews and leading the data collection and methodological development. Marinella Ferrara contributed to the analysis and interpretation of the data collected. The study is situated within Beatrice Bianco’s doctoral research Crafting Situated Futures: Co-Designing Hybrid Knowledge Ecologies for Traditional Textile Practices in Southern Italy and Saudi Arabia (tentative) supervised by Marinella Ferrara, to whom I am grateful for guidance and support. During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used ChatGPT-5 (OpenAI) for language editing and refinement purposes. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Braudel, F. Civilisation Matérielle, Economie et Capitalisme. Tome 1: Les Structures du Quotidien; Armand Colin: Paris, France, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Landes, D.S. The Unbound Prometheus: Technological Change and Industrial Development in Western Europe from 1750 to the Present; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Sennett, R. The Craftsman; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Bunnell, K. Craft and digital technology. World Crafts Counc. J. 2004, 14, 40–47. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, G.; Shi, Q.; Yao, Y.; Feng, Y.L.; Yu, T.; Liu, B.; Ma, Z.; Huang, L.; Diao, Y. Learning from hybrid craft: Investigating and reflecting on innovating and enlivening traditional craft through literature review. In Proceedings of the CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Honolulu, HI, USA, 11–16 May 2024; pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Hertzmann, A. Can computers create art? Commun. ACM 2018, 61, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epstein, Z.; Hertzmann, A.; Akten, M.; Farid, H.; Fjeld, J.; Frank, M.R.; Groh, M.; Herman, L.; Leach, N.; Mahari, R.; et al. Art and the science of generative AI. Science 2023, 380, 1110–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norvig, P.; Russell, S.J. Intelligenza Artificiale. Un Approccio Moderno; Pearson Italia: Milano, Italy, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, A.I. The Artist in the Machine: The World of AI-Powered Creativity; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Giaccardi, E.; Redström, J. Technology and more-than-human design. Des. Issues 2020, 36, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verganti, R. Design-Driven Innovation: Changing the Rules of Competition by Radically Innovating What Things Mean; Harvard Business Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Becattini, G. The Marshallian industrial district as a socio-economic notion. In Industrial Districts and Inter-Firm Co-Operation in Italy; Pyke, F., Becattini, G., Sengenberger, W., Eds.; International Institute for Labour Studies: Geneva, Switzerland, 1990; pp. 37–51. [Google Scholar]

- Micelli, S. Futuro Artigiano: L’innovazione Nelle Mani Degli Italiani; Marsilio: Venice, Italy, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Manzini, E. Design, When Everybody Designs: An Introduction to Design for Social Innovation; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Cipolla, C.M. Before the Industrial Revolution: European Society and Economy 1000–1700; Routledge: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Branzi, A. Introduzione al Design Italiano: Una Modernità Incompleta; Baldini Castoldi Dalai: Milan, Italy, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Choay, F. Le patrimoine en question. Esprit 2009, 11, 194–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowenthal, D. Why the past matters. Herit. Soc. 2011, 4, 159–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayles, N.K. The materiality of informatics. Config. Interdiscip. J. Cult. Hist. Technol. 1992, 10, 121–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braidotti, R. Posthuman Knowledge; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Haraway, D.J. Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene; Duke University Press: Durham, NC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barad, K. Meeting the Universe Halfway: Quantum Physics and the Entanglement of Matter and Meaning; Duke University Press: Durham, NC, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pye, D. The Nature and Art of Workmanship; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Suchman, L.A. Plans and Situated Actions: The Problem of Human–Machine Communication; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Rosner, D.K. Critical Fabulations: Reworking the Methods and Margins of Design; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Devendorf, L.; Rosner, D.K. Beyond hybrids: Metaphors and imaginaries in computational making. In Proceedings of the Designing Interactive Systems Conference, Edinburgh, UK, 10–14 June 2017; pp. 995–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sreenivasan, A.; Suresh, M. Design thinking and artificial intelligence: A systematic literature review exploring synergies. Int. J. Innov. Stud. 2024, 8, 297–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tironi, M.; Chilet, M.; Marín, C.U.; Hermansen, P. (Eds.) Design for More-Than-Human Futures: Towards Post-Anthropocentric Worlding; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Jönsson, L.; Lenskjold, T.U. A foray into not-quite companion species: Design experiments with urban animals. Des. Issues 2017, 33, 72–84. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkie, A.; Michael, M. The Aesthetics of More-Than-Human Design: Speculative Energy Briefs for the Chthulucene. Hum.–Comput. Interact. 2025, 40, 104–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, A.G. Ethnocomputational creativity in STEAM education: A cultural framework for generative justice. Teknokultura 2016, 13, 587–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arzberger, A.; Lupetti, M.L.; Giaccardi, E. Reflexive data curation: Opportunities and challenges for embracing uncertainty in human–AI collaboration. ACM Trans. Comput.-Hum. Interact. 2024, 31, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giaccardi, E.; Bendor, R. (Eds.) RETHINK DESIGN: A Vocabulary for Designing with AI; DCODE Network/Politecnico di Milano: Milan, Italy, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Malterud, K.; Siersma, V.D.; Guassora, A.D. Sample size in qualitative interview studies: Guided by information power. Qual. Health Res. 2016, 26, 1753–1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koskinen, I.; Zimmerman, J.; Binder, T.; Redström, J.; Wensveen, S. Design Research Through Practice: From the Lab, Field, and Showroom; Morgan Kaufmann: Burlington, MA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Sanders, E.B.-N.; Stappers, P.J. Co-creation and the new landscapes of design. CoDesign 2008, 4, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunne, A.; Raby, F. Speculative Everything: Design, Fiction, and Social Dreaming; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Candy, S.; Kornet, K. Turning foresight inside out: An introduction to ethnographic experiential futures. J. Futures Stud. 2019, 23, 3–22. [Google Scholar]

- Fab City Global Initiative. Fab City Research Labs: Global Network for Localized Production and Innovation. Available online: https://fab.city (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- Europeana Foundation. Craft Heritage Collections; Europeana. 2023. Available online: https://www.europeana.eu/en/collections/topic/77-crafts (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- Distributed Design Platform. Distributed Design: Connecting Makers, Designers, and Creative Communities Across Europe. 2023. Available online: https://distributeddesign.eu (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- Higgins, S. The DCC curation lifecycle model. Int. J. Digit. Curation 2008, 3, 134–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.