Abstract

This study investigates and compares archaeological site management practices across diverse cultural contexts, focusing on how cultural factors influence preservation, stakeholder involvement, and management strategies. Employing a mixed-methods comparative design, the research integrates field observations, interviews with site managers and local stakeholders, and archival analysis. Three case studies, the Giza Necropolis in Egypt, Madain Saleh in Saudi Arabia, and the Al-Ain Archaeological Sites in the United Arab Emirates, form the empirical foundation for this analysis. Thematic and qualitative comparative analyses are used to identify cross-cultural patterns, challenges, and best practices. The findings reveal that management approaches are profoundly shaped by their respective cultural settings. Regions with strong traditions of community participation, such as Al-Ain, tend to integrate local knowledge and foster sustainable preservation outcomes. In contrast, state-dominated systems, as seen in Egypt and Saudi Arabia, often face constraints related to bureaucratic processes and limited local engagement. Across all contexts, factors such as governance structures, funding mechanisms, and cultural attitudes toward heritage emerge as decisive in shaping management effectiveness and sustainability. The results offer essential perspectives for the strategy of engaging local communities in the management of archaeological sites, and may be beneficial for implementation in other Arab countries.

1. Introduction

Archaeological sites serve as tangible links to past civilisations, providing invaluable insights into human behaviour, social evolution, and technological progress [1]. They encompass not only material remains such as artifacts, monuments, and landscapes but also the intangible legacies of belief systems, traditions, and social practices that shaped ancient societies [2].

Archaeological resource management has evolved from a focus on individual monuments to a broader concern with managing the historic environment as a physical and functional landscape, including archaeological sites, their surrounding settings, land-use relationships, and patterns of human interaction, through integrated and holistic approaches [3]. The purpose of this section is to establish the analytical concepts that structure the comparative examination of archaeological site management at Giza, Madāʾin Ṣāliḥ, and Al-Ain. It entails these sites, the changing role of archaeological sites in society, and a more integrated and holistic management [4,5]. Therefore, archaeological sites become more accessible for the public, serving as dynamic laboratories for multidisciplinary research and as educational platforms that foster cultural awareness and critical engagement [6]. They also possess significant socio-economic value: when managed responsibly, heritage tourism can create employment opportunities, enhance local pride, and encourage cross-cultural dialogue, thereby contributing to the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), particularly those related to sustainable cities and communities, decent work, and economic growth [7,8,9,10].

Contemporary archaeological site management encompasses an evolving set of strategies and practices through which heritage professionals, policymakers, local communities, and other stakeholders work to safeguard archaeological resources while responding to technological, social, and environmental change [11]. Whereas earlier management models emphasized preservation through centralized, state-led control, more recent approaches increasingly foreground integrated, participatory, and adaptive practices that recognize heritage as both a cultural and socio-economic resource shaped by human values and social relationships [4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12]. Within this shift, people particularly local communities and site users are no longer viewed solely as passive beneficiaries but as active participants whose knowledge, interests, and actions influence management outcomes. As a result, community participation has emerged as a central principle of contemporary heritage governance [13,14].

Preventive conservation represents another key pillar of contemporary archaeological site management, prioritising risk mitigation through environmental monitoring, routine site maintenance, and emergency preparedness [15,16]. Technological innovation, particularly GIS mapping, 3D scanning, and digital photogrammetry, has revolutionised archaeological documentation [17]. Strong legal and policy frameworks remain vital for ensuring accountability and standardized protection [18]. International conventions, such as the UNESCO World Heritage Convention, are complemented by local regulations that align conservation with sustainable tourism and cultural education. Through case-based understanding, as illustrated by Giza, Madain Saleh, and Al-Ain, this discussion underscores the necessity of context-sensitive and culturally grounded management frameworks that sustain both heritage integrity and societal value.

Earlier research has primarily concentrated on management processes while often overlooking the cultural context. Additionally, there are insufficient studies on the management of archaeological sites in Arab regions, even though these areas include numerous sites with histories spanning thousands of years. This study aims to explore how the cultural context shapes the management of the archaeological sites of Al-Ain’s archaeological landscape in the UAE, Giza Necropolis in Egypt, and Mada’in Saleh in Saudi Arabia.

This study has a single overarching aim: to examine how cultural context shapes archaeological site management practices through a theory-informed, cross-cultural comparison of three World Heritage Sites in the Arab region.

To achieve this aim, the study pursues the following specific objectives:

- (1)

- to analyze governance structures, conservation strategies, tourism management, research and educational activities, and community engagement at the selected sites;

- (2)

- to compare these management dimensions across different cultural and institutional contexts using a unified comparative framework; and

- (3)

- to assess how cultural values and governance traditions influence management priorities and stakeholder participation.

These objectives are addressed through triangulated qualitative data and form the basis for identifying cross-cultural patterns and context-specific management outcomes.

To operationalize the study’s comparative and analytical objectives, the research is guided by the following questions:

RQ1: How do different cultural contexts shape governance structures and decision-making models in archaeological site management across the selected case studies?

RQ2: In what ways do cultural values and institutional traditions influence community engagement, conservation priorities, and tourism management practices at the three sites?

RQ3: What comparative patterns emerge from the interaction between cultural context and management outcomes, and how do these patterns explain similarities and differences across the cases?

These research questions provide the analytical structure for the comparative framework and directly inform the organization of Section 4 and Section 5.

Beyond providing descriptive accounts of individual sites, this study adopts a theory-informed comparative approach to examine how cultural context systematically shapes archaeological site management. Drawing on governance theory, values-based heritage management, and sustainable heritage tourism frameworks, the analysis moves beyond case-by-case description to identify patterned relationships between cultural values, governance structures, community participation, and management outcomes. By applying a consistent comparative framework across three contrasting cultural settings, the study advances existing heritage management literature from descriptive synthesis toward explanatory, cross-cultural insight.

The novelty of this study lies in three interconnected contributions. First, it provides a systematic comparative analysis of archaeological site management within the Arab region, a context that remains underrepresented in cross-cultural heritage management scholarship. Second, it explicitly examines the relationship between cultural context and governance structures, demonstrating how cultural values and institutional traditions shape participation models, conservation priorities, and tourism strategies. Third, the study integrates a triangulated qualitative dataset combining field observations, interviews, focus groups, and documentary analysis within a unified theoretical and comparative framework. Together, these elements move beyond descriptive comparison to offer an empirically grounded and theoretically informed contribution to comparative heritage management research. The concepts outlined in this section are examined empirically through three contrasting archaeological case studies: the Giza Necropolis (Egypt), Madāʾin Ṣāliḥ (Saudi Arabia), and the Al-Ain Archaeological Sites (United Arab Emirates). These cases were selected because they share comparable global heritage status and state involvement, yet differ markedly in governance traditions, cultural values, and participation models. Throughout the manuscript, theoretical concepts introduced here such as governance structure, cultural context, and community participation are explicitly analyzed in relation to observed management practices at these sites.

1.1. Literature Review

This literature review selectively examines theoretical and empirical scholarship directly relevant to the comparative analysis of archaeological site management in the three case studies examined in this paper. Rather than providing an exhaustive overview, the review focuses on concepts that are later operationalized in the comparative framework and applied empirically [19]. Foundational scholarship has emphasized that heritage sites embody collective memory, identity, and social continuity, positioning their preservation as a cultural and ethical responsibility [20,21]. However, growing criticism highlights that these ostensibly universal frameworks often intersect and at times conflict with local cultural values, governance systems, and socio-economic realities, raising questions about their global applicability. Seminal works in heritage studies have increasingly argued for a shift from object-centered conservation toward values-based and people-centered approaches. The Getty Conservation Institute’s Values and Heritage Conservation report underscores that heritage significance is socially constructed and context-dependent, requiring management strategies that account for diverse stakeholder values rather than solely expert-defined criteria [1,2]. Similarly, the bibliographic compendium by the Getty Conservation Institute on Conservation and Management of Archaeological Sites synthesizes global practice and highlights the range of contexts in which management must operate (technical, social, and economic). The heritage reader [3] situates heritage management within broader cultural, political, and social processes, emphasizing that heritage is not merely preserved but actively negotiated through contemporary practices. These works mark a critical transition from technocratic conservation toward integrated, reflexive heritage governance. The following review selectively focuses on concepts that are later operationalized in the comparative analysis.

Recent scholarship further emphasizes the need for context-sensitive management frameworks that incorporate local governance traditions, community relationships, and socio-cultural priorities [22]. While international conventions provide important regulatory structures, their implementation is frequently reshaped by regional traditions, national policies, religious frameworks, and local perceptions of heritage value. While challenges such as rapid urbanization, political instability, and climate vulnerability affect archaeological management globally, their implications vary significantly depending on regional governance structures, institutional capacity, and historical trajectories. In regions such as the Middle East, Africa, and South Asia, these pressures often intersect with distinct political, economic, and administrative contexts that differ from those in which conservation traditions associated with European professional and institutional heritage practice were originally formulated [8].

Preventive conservation remains a cornerstone of archaeological preservation, emphasizing monitoring, maintenance, and risk mitigation [15]. However, its effectiveness is contingent on institutional capacity, funding stability, and governance coherence. In contexts marked by conflict or limited administrative resources, preventive strategies require adaptation and prioritization. Bibliographic syntheses produced by the Getty Conservation Institute highlight that conservation effectiveness depends not only on technical interventions but also on management structures, decision-making processes, and stakeholder coordination. These insights reinforce the need to integrate technical conservation with governance and cultural considerations.

1.1.1. Community Participation and Local Agency

A persistent critique of traditional heritage management is its marginalization of local communities in favor of expert-led decision-making. Contemporary research increasingly recognizes community participation as fundamental to sustainable heritage management. Participatory and co-creative approaches have been shown to strengthen stewardship, enhance legitimacy, and improve conservation outcomes [14,23,24,25]. However, the form and effectiveness of community engagement vary widely across cultural and political contexts.

In post-colonial settings, historical exclusion and power imbalances have often produced mistrust between communities and heritage authorities [26]. Empirical studies demonstrate that when communities are meaningfully involved in decision-making rather than being limited to labor roles or symbolic forms of participation outcomes related to site protection and long-term maintenance improve substantially [27]. These insights inform the present analysis by guiding the comparison of participation mechanisms observed at each site, rather than serving as abstract normative principles.

1.1.2. Empirical Evidence from Comparative and Regional Case Studies

Empirical research on archaeological site management demonstrates that governance models, participation mechanisms, and conservation strategies vary significantly across cultural and regional contexts. Case-based studies from regions including the Middle East, parts of Africa, East Asia, and Latin America demonstrate how global heritage paradigms are adapted, contested, or selectively implemented in practice within diverse political, institutional, and cultural contexts. Throughout this study, the term “Western” is used in a limited and specific sense to refer to heritage management frameworks developed primarily within European and North American institutional and professional contexts.

Research on archaeological sites in Egypt and North Africa has shown that highly centralized governance systems often prioritize monument protection and national symbolism while limiting local participation to employment-based roles. Similar patterns have been documented in Gulf contexts, where state-led heritage initiatives coexist with expanding tourism agendas, producing structured but institutionally mediated forms of community engagement [4]. In contrast, empirical studies from community-oriented heritage projects in parts of Africa and the Eastern Mediterranean demonstrate that decentralized governance arrangements can facilitate broader stakeholder involvement, though often with uneven conservation outcomes [5].

Preventive conservation has likewise been tested unevenly across contexts. While long-term monitoring and risk mitigation have proven effective in well-resourced settings, empirical studies from arid and rapidly developing regions reveal challenges related to institutional capacity, climate stress, and tourism pressure [6,7]. These findings suggest that preventive conservation is not a universally transferable model but one that requires contextual adaptation.

1.1.3. Technological Innovations and Their Limitations

Alongside governance and community participation, technological innovation has become a significant factor shaping how archaeological sites are managed, documented, and made accessible, with important implications for sustainability and stakeholder engagement. Technological innovation has transformed archaeological site management, particularly in projects supported by substantial institutional and financial resources. Tools such as remote sensing, GIS, 3D scanning, photogrammetry, and machine-learning applications now support site documentation, monitoring, interpretation, and public engagement [28,29,30,31]. These technologies can enhance data preservation and expand access to heritage through digital visualization and virtual platforms [32]. However, empirical studies caution that technological applications often reflect heritage governance approaches developed within European policy contexts have been critiqued for privileging state oversight over community participation, emphasizing technical precision and visual representation while overlooking social accessibility, local knowledge, and community relevance [1]. In contexts with limited resources, disparities in funding, expertise, and infrastructure further constrain the effective use of advanced technologies. Consequently, technology is most effective when integrated into broader management strategies that account for community participation, institutional capacity, and long-term sustainability, rather than being treated as a stand-alone solution.

1.1.4. Legislative Frameworks: Global Ideals and Local Realities

Legal and policy frameworks are central to archaeological site management, frequently modelled on heritage management frameworks developed primarily within European and North American institutional and policy contexts [18]. International agreements, notably the UNESCO World Heritage Convention (1972), establish global norms but encounter challenges when applied in politically unstable or economically marginalized contexts. Comparative legal analyses demonstrate that heritage legislation reflects underlying social and political structures, leading to significant variation in enforcement and effectiveness across countries [33,34]. Critiques of universalized heritage governance highlight unintended consequences, including gentrification, exclusion of local voices, and prioritization of monumental or aesthetic values over living cultural practices. These tensions underscore the importance of adapting legal frameworks to regional governance capacities, cultural values, and societal needs.

1.1.5. Tourism, Sustainability, and Heritage Economics

Sustainable tourism is widely promoted as a mechanism for financing conservation and supporting local development. However, heritage economics research, including empirical work on the economics of heritage conservation (e.g., the volume *Essential Economics for Heritage*), demonstrates that tourism benefits and burdens are unevenly distributed, often exacerbating inequalities when local communities lack decision-making power or economic participation. Heritage management frameworks developed primarily within European and North American institutional and policy contexts typically emphasize visitor experience management through controlled access and interpretation [8], yet these approaches may generate pressure in regions with limited infrastructure or fragile social systems. Recent interdisciplinary work in heritage economics highlights the need to evaluate heritage not only in cultural terms but also through social and economic value creation, opportunity costs, and long-term sustainability. Tourism strategies must therefore integrate conservation objectives with equitable benefit-sharing and local economic resilience [35,36].

1.1.6. Conservation, Restoration, and Long-Term Risk

Modern conservation theory emphasizes minimal intervention and the principle of maximum feasible reversibility acknowledging that complete reversibility is rarely achievable supported by multidisciplinary methodologies and digital documentation [15,37,38,39]. However, climate change introduces escalating risks including desertification, flooding, coastal erosion, and extreme weather that challenge established conservation norms. Risk-management studies, particularly those addressing acute threats rather than gradual material decay, stress the importance of adaptive planning, disaster preparedness, and the integration of traditional knowledge to enhance resilience at archaeological sites [40,41,42,43].

1.1.7. Critical Synthesis and Research Gap

Collectively, the literature demonstrates that while heritage governance approaches developed within European policy contexts have been critiqued for privileging state oversight over community participation have shaped global practice, their effectiveness depends on contextual adaptation. In this study, values-based management is operationalized by examining how different stakeholder values are reflected in governance structures, participation models, and conservation priorities across cases. Despite these advances, comparative research integrating governance, conservation, tourism, and community engagement particularly in Arab regions remains limited.

This study addresses this gap by adopting a cross-cultural comparative approach to archaeological site management in Egypt, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates. Empirical studies increasingly show that the effectiveness of governance-oriented and values-based frameworks depends on how they are implemented within specific cultural, institutional, and political contexts.

While existing comparative heritage management studies have examined governance, participation, or tourism in isolation, they have rarely integrated these dimensions within a single cross-cultural analytical framework grounded in cultural context. Moreover, comparative research focusing specifically on Arab archaeological sites remains limited and often descriptive. By jointly analyzing governance structures, community engagement, conservation practices, and tourism management through a cultural lens, this study addresses these gaps and extends comparative heritage research into a region and analytical configuration that has received limited systematic attention.

Rather than serving as a descriptive overview of heritage scholarship, the theoretical perspectives reviewed above are directly mobilized in the empirical analysis. Governance theory informs the examination of institutional authority and decision-making structures; values-based heritage management guides the assessment of whose values are prioritized in conservation and tourism practices; and community participation literature frames the analysis of stakeholder involvement across cases. These perspectives are operationalized through the comparative framework and applied systematically in Section 4 and Section 5.

Despite the growing number of empirical case studies, comparative research that systematically integrates governance, cultural context, community participation, and conservation practices within a single analytical framework remains limited, particularly in the Arab region. Existing studies often focus on individual sites or single dimensions of management. The present study builds on this empirical foundation by conducting a theory-informed, cross-cultural comparison that examines how these dimensions interact across multiple sites, thereby extending existing case-based research toward broader comparative insight.

1.2. Theoretical Framework

This study adopts a focused theoretical framework to guide the comparative analysis of archaeological site management at the Giza Necropolis, Madāʾin Ṣāliḥ, and the Al-Ain Archaeological Sites. Rather than introducing additional abstract theory, the framework operationalizes three complementary perspectives governance theory, values-based heritage management, and sustainable heritage tourism to structure the empirical comparison. Governance theory is applied to analyze how institutional authority, decision-making centralization, and policy frameworks shape participation and management outcomes across different cultural contexts [18]. Values-based heritage management provides the lens through which cultural meanings, identity, and stakeholder values are examined in relation to conservation and tourism practices [6]. Sustainable heritage tourism theory informs the assessment of how visitor management and economic use are balanced with long-term site protection and local benefits [10].

1.3. Cultural Contexts

In this study, cultural context is examined through three archaeological case studies the Giza Necropolis (Egypt), Madāʾin Ṣāliḥ (Saudi Arabia), and the Al-Ain Archaeological Sites (United Arab Emirates) each of which operates within a distinct social, historical, and institutional environment. These cases provide the empirical basis for understanding how cultural context shapes the perception, valuation, and management of archaeological heritage.

Cultural context is understood here as the combination of beliefs, traditions, governance systems, and socio-economic structures that influence relationships between people and heritage [21]. Rather than functioning as a static backdrop, cultural context actively shapes how heritage is interpreted, protected, and utilized. Across the three case studies, heritage management practices are embedded in local worldviews and governance traditions, even as they interact with globally standardized frameworks such as the UNESCO World Heritage Convention (1972) and ICOMOS charters [19].

In this study, “community involvement” refers to the participation of individuals and groups who reside in, work in, or maintain socio-economic and cultural ties to the archaeological site and its surrounding area. Community actors are analytically distinguished from governmental agencies, educational institutions, and tourism authorities, even when individuals occupy hybrid professional roles. This distinction allows community involvement to be examined as localized stakeholder engagement rather than institutional governance, a distinction that is particularly relevant across the three case studies. The role of cultural context is evident in how each site is managed. At Giza, heritage management reflects a state-centered system rooted in national identity and historical pride, emphasizing centralized authority and monument protection [44]. At Madāʾin Ṣāliḥ, management practices are shaped by Islamic cultural values and national development priorities under Vision 2030, balancing international conservation standards with religious and social considerations. In contrast, the Al-Ain Archaeological Sites illustrate a hybrid model in which global heritage principles are integrated with local traditions of education, community engagement, and urban planning; while religious values form part of the broader social context, heritage management practices at Al-Ain are articulated primarily through institutional, educational, and planning frameworks rather than explicitly religious governance principles [45].

These differences demonstrate that cultural context plays a decisive role in shaping management philosophies and outcomes. Where governance is highly centralized, participation tends to be structured through institutional and employment-based mechanisms [46]. Where cultural identity and community education are emphasized, broader—though still institutionally mediated forms of engagement emerge. Recognizing these dynamics is essential for developing context-sensitive, participatory, and sustainable archaeological site management strategies. By framing cultural context explicitly through the three case studies, this section provides the conceptual foundation for the comparative analysis that follows.

2. Cases Studies

2.1. Egypt: Giza Necropolis

The Giza Necropolis, located on the western edge of Cairo, is one of the most iconic archaeological landscapes in the world. Comprising the pyramids of Khufu, Khafre, and Menkaure, along with the Great Sphinx and extensive funerary complexes, the site represents the pinnacle of Old Kingdom architectural achievement [47]. Designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site, Giza receives several million visitors per year, placing considerable pressure on its fragile monuments.

2.1.1. Conservation Status and Challenges

The site faces persistent threats from urban encroachment, air pollution, groundwater fluctuations, and visitor-related degradation. Conservation efforts focus on stabilizing ancient masonry, mitigating erosion, and controlling the impacts of large-scale tourism. The proximity of greater Cairo poses ongoing challenges related to land-use conflicts and environmental change.

2.1.2. Governance and Community Involvement

Management of the Giza Necropolis is led by the Egyptian Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities, with the Supreme Council of Antiquities (SCA) overseeing day-to-day operations. State control is strong, and internationally supported conservation projects are common. The local communities associated with the site primarily include residents of surrounding neighborhoods on the Giza Plateau, local tourism workers (such as guides, guards, vendors, and service providers), and small business owners whose livelihoods are linked to visitor activity. Community involvement remains limited and is largely concentrated in employment within tourism services, site maintenance, and ancillary support roles. Although engagement initiatives exist, they are not formally institutionalized and offer limited opportunities for participation in planning, interpretation, or decision-making compared with other regional contexts [48].

2.2. Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA): Madain Saleh

Its monumental rock-cut tombs, inscriptions, and desert landscapes earned UNESCO World Heritage inscription in 2008, marking the first World Heritage designation for the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia.

2.2.1. Conservation Status and Challenges

The site’s preservation is generally strong due to its remote desert setting, but natural erosion, wind abrasion, and increasing foot traffic pose risks to the carved facades. Recent national initiatives connected to Saudi Vision 2030 have prompted rapid tourism development, making the sustainable management of visitor flows a primary concern. Protection from vandalism and unauthorized access remains a priority.

2.2.2. Governance and Community Involvement

Madāʾin Ṣāliḥ is managed by the Saudi Commission for Tourism and National Heritage (SCTH), the national governmental body responsible for heritage protection and tourism development and is supported by the Royal Commission for AlUla (RCU), a government-established authority tasked with the planning, conservation, and sustainable development of the AlUla region. Through these institutions, the site benefits from state-led investment in conservation, research, and visitor infrastructure. Community involvement has expanded in recent years through formal training programs, local employment opportunities, and heritage-awareness initiatives coordinated by these authorities; however, participation remains largely structured within government-led frameworks rather than grassroots or community-driven governance arrangements.

2.3. United Arab Emirates (UAE): Al-Ain Archaeological Sites

The Al-Ain archaeological landscape comprising the Hafit tombs, Hili cultural zone, Bidaa Bint Saud, and related irrigations systems spans over 4000 years of occupation and is central to understanding Bronze Age and Iron Age developments in southeastern Arabia. Listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site, it represents one of the most cohesive and best-preserved archaeological zones in the Gulf region.

2.3.1. Conservation Status and Challenges

While the sites are well-preserved, they face pressures from rapid urban expansion, infrastructure development, and environmental changes. Conservation programs prioritize preventive care, site stabilization, and the integration of archaeological zones into Al-Ain’s broader heritage and urban plans. Maintaining controlled visitor access and ensuring long-term landscape protection remain key challenges [49].

2.3.2. Governance and Community Involvement

The Department of Culture and Tourism—Abu Dhabi (DCT Abu Dhabi) oversees management through a structured framework emphasizing research, education, and public outreach. Compared with Egypt and Saudi Arabia, Al-Ain exhibits stronger and more formalized community engagement through educational programs, heritage festivals, local volunteer initiatives, and partnerships with schools and universities. Collaboration with international research teams further supports conservation and interpretation.

The three case studies were selected to ensure analytical comparability while allowing for cultural variation. All sites are UNESCO World Heritage Sites, subject to international conservation standards, state-led governance structures, and active tourism management. At the same time, they operate within distinct cultural, institutional, and socio-political contexts. This combination of shared structural characteristics and contextual diversity enables meaningful cross-case comparison, allowing differences in management practices to be examined as culturally and institutionally mediated rather than site-specific anomalies.

3. Methods

3.1. Research Design

This study employed a qualitative, exploratory research design to examine archaeological site management practices across diverse cultural contexts. Data were collected through semi-structured interviews, focus groups, site observations, and documentary analysis involving site managers, local community members, heritage professionals, and policymakers. A comparative approach was applied to three archaeological case studies representing different cultural, institutional, and geographical settings.

Data analysis was conducted using thematic coding and interpretive analysis to identify patterns, themes, and challenges related to governance, community participation, conservation practices, and tourism management. This analytical process generated qualitative insights into the socio-cultural and institutional factors influencing archaeological site management practices. Although qualitative in nature, the study adopted a mixed qualitative design by integrating multiple data sources and methods to enhance analytical depth, triangulation, and comparative robustness.

All data collection and analysis were completed prior to the preparation of this manuscript.

3.2. Case Selection

The selection of archaeological sites for this study is guided by specific criteria aligned with the research objectives and the aim for diversity in cultural contexts. Several key criteria shape the selection process:

- Cultural and Institutional Variation: The selected sites represent distinct cultural, political, and institutional contexts within the Arab region, including differences in governance traditions, heritage policy frameworks, religious and national identity narratives, and approaches to community participation. While geographically proximate, Egypt, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates exhibit meaningful variation in how archaeological heritage is managed, allowing for comparative analysis within a shared regional setting;

- Geographical Representation: Archaeological sites are selected from diverse geographic regions to capture varying environmental conditions, socio-political contexts, and heritage management challenges. This ensures a broad spectrum of sites, encompassing different climates, landscapes, and socio-economic settings, providing a holistic view of site management;

- Institutional Heritage Designation: Sites were selected based on their formal recognition within national and international heritage frameworks (including UNESCO World Heritage designation), reflecting the valuation of heritage significance by state and institutional authorities. This criterion does not presume a singular or universal definition of heritage value but provides a common institutional reference point for comparative analysis, while acknowledging that community-based perceptions of heritage significance may differ from official designations;

- Accessibility and Feasibility: Consideration is given to the accessibility and feasibility of conducting research at each site to ensure practicality and logistical viability. Sites that were accessible and conducive to data collection activities were selected to enable effective fieldwork and stakeholder engagement.

- Community Engagement Opportunities: Sites offering opportunities for meaningful engagement with local communities, stakeholders, and site managers are prioritized. This criterion ensures the inclusion of diverse perspectives and emphasizes the central role of community voices in the research process.

By applying these criteria, the selection process aims to encompass a diverse range of cultural contexts while also ensuring practicality, relevance, and engagement with key stakeholders. This approach enables the study to offer comprehensive insights into archaeological site management practices across varied cultural landscapes.

3.3. Data Collection and Analysis

In this study, a comprehensive data-collection approach is employed to thoroughly explore the intricacies of archaeological site management practices across diverse cultural settings. The research adopted semi-structured interviews, which facilitate in-depth discussions with a wide range of stakeholders, including site managers, heritage professionals, government officials, local community representatives, and academic experts, The interviewee profile is summarized in Appendix A (Table A1). For clarity, participants’ professional roles were distinguished from their formal mode of involvement with each site, particularly where expertise was provided through international or external advisory arrangements. The interview was conducted from November 2023 till March 2024. Detailed notes and audio recordings ensure accurate and complete data collection.

A purposive sampling strategy was employed to select interview and focus-group participants with direct involvement in archaeological site management, conservation, tourism, research, or community engagement. Participants were identified through institutional affiliations, professional roles, and site-based responsibilities to ensure representation of multiple stakeholder perspectives. A total of 20 semi-structured interviews were conducted across the three case studies, with representation from each site (Egypt, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates). While the absolute number of interviews varied slightly across sites, the distribution represents a broadly comparable proportion of accessible and relevant stakeholder categories at each location. Interview coverage was guided by stakeholder availability and institutional access rather than fixed numerical quotas, ensuring that key governance, professional, and community perspectives were represented consistently across all three case studies. Interviewees included site managers, government officials, heritage professionals, tourism practitioners, researchers, and local community representatives (see Appendix A, Table A1).

For analytical purposes, interview participants were categorized into stakeholder groups based on their primary role in relation to site management: (1) governmental and heritage authorities, (2) institutional actors (including educators, researchers, and cultural officers), (3) tourism and economic actors, and (4) local community members. Where participants occupied hybrid roles (e.g., academic professionals with leadership roles in local communities), their perspectives were analyzed in relation to both institutional affiliation and community position, rather than being treated as a homogeneous category.

Interviews were conducted between November 2023 and March 2024 and followed a semi-structured format to allow comparability while retaining flexibility for in-depth discussion. Interviews typically lasted between 45 and 75 min. Depending on participant preference and site context, interviews were conducted in Arabic or English. All interviews were audio-recorded with informed consent and subsequently transcribed for analysis. Focus-group discussions were conducted in May 2024 and followed a similar thematic structure, facilitating cross-validation of individual interview data.

Data collection was distributed across the three case studies to support balanced cross-cultural comparison. Of the 20 semi-structured interviews conducted, 7 were carried out at the Giza Necropolis (Egypt), 7 at Madāʾin Ṣāliḥ (Saudi Arabia), and 6 at the Al-Ain Archaeological Sites (United Arab Emirates). Focus-group discussions included participants from each site and were organized to reflect local stakeholder composition. Site observations were conducted at all three locations during field visits corresponding to the interview periods, ensuring consistent coverage across cases.

Documentary analysis was also undertaken on a site-specific basis. For each case study, relevant management plans, policy documents, conservation reports, and publicly available institutional publications were reviewed. This ensured that documentary evidence corresponded directly to the site where interviews and observations were conducted, strengthening contextual accuracy and cross-case comparability.

In addition to interviews, focus group discussions provide a collaborative platform for stakeholders to engage in collective dialogue, guided by trained moderators. They were conducted in May 2024. These discussions allow participants to share their insights, concerns, and aspirations regarding site management practices, enriching the dataset with nuanced perspectives and collective viewpoints. Document analysis serves as a complementary method, enabling researchers to review existing literature, reports, policies, and management plans relevant to the selected archaeological sites. This comprehensive review provides valuable historical context, policy insights, and thematic trends, enhancing the depth and breadth of the study’s findings.

Participant observation immerses researchers in the site environment, capturing real-time insights into site management activities, visitor interactions, and community engagements. Detailed field notes, supplemented by photographs and audio recordings, document key observations and facilitate data triangulation.

Finally, a cross-cultural comparison synthesises data from multiple case studies to identify overarching themes, patterns, and variations in site management practices across different cultural contexts.

Data analysis followed a thematic coding approach. Transcripts from interviews, focus groups, observation notes, and documentary sources were coded manually using an iterative process informed by the study’s theoretical framework and research questions. Initial open coding identified recurring concepts related to governance, conservation, tourism management, community engagement, and cultural context. These codes were then refined into higher-order thematic categories to support cross-case comparison. Manual coding was selected to maintain close interpretive engagement with the qualitative material, given the moderate dataset size and the cross-cultural nature of the analysis (Table 1).

Table 1.

Descriptive summary of data collection methods and associated analytical themes used in the study.

To enhance analytical rigor and validity, multiple strategies were employed. Data triangulation was achieved by comparing findings across interviews, focus groups, site observations, and documentary sources. Coding consistency was ensured to enhance analytical rigor and interpretive validity through repeated review of coded material and cross-checking emergent themes against the raw qualitative data, rather than for software or data management purposes. Interpretive validity was further supported by comparing patterns across the three sites rather than relying on single-case inference. This combination of triangulation, iterative coding, and cross-case validation strengthens the reliability of the qualitative findings. A detailed overview of participant roles and site affiliations is provided in Appendix A (Table A1).

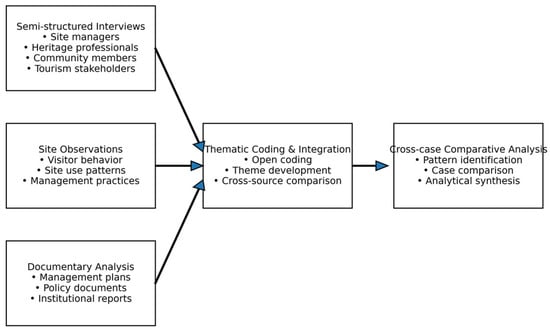

Data analysis followed a structured, multi-stage qualitative analytical process designed to support systematic cross-cultural comparison. First, all interview transcripts, focus-group transcripts, observation notes, and documentary materials were read in full to develop familiarity with the data. Second, an initial round of open coding was conducted to identify recurring concepts related to governance arrangements, conservation practices, tourism management, community engagement, and cultural context. Third, these initial codes were iteratively refined and grouped into higher-order thematic categories aligned with the study’s research questions and comparative framework (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Schematic illustration of the triangulated qualitative data analysis process, showing how interviews, site observations, and documentary sources were integrated through thematic coding and cross-case comparison.

Thematic categories were then applied consistently across the three case studies to enable cross-case comparison. This process allowed similarities and differences in management practices to be systematically identified and contrasted. Analytical interpretation was guided by governance theory, values-based heritage management, and sustainable tourism frameworks, ensuring that empirical patterns were examined as theoretically meaningful relationships rather than isolated observations.

In the final analytical stage, patterns and relationships across cases were synthesized by comparing thematic findings for each site against the comparative criteria. Attention was given to how cultural context shaped governance structures, participation mechanisms, and management priorities. This cross-case synthesis enabled the identification of recurring configurations as well as context-specific deviations, forming the basis for Section 4 and Section 5. All data collection and analysis were completed prior to the preparation of this manuscript.

Patterns and trends within the data are identified and analysed to uncover underlying structures, relationships, and dynamics. This involves identifying regularities, deviations, and anomalies within the data to gain insights into site management practices and processes.

By employing these techniques, researchers gain a deeper understanding of archaeological site management practices, uncovering insights, patterns, and relationships within the data. This qualitative analysis process enables researchers to generate rich, nuanced findings that contribute to theory-building, policy development, and practical recommendations for site management practitioners.

3.4. Comparative Framework

This study employs a structured comparative framework based on clearly defined analytical dimensions and criteria to examine archaeological site management across diverse cultural contexts. The framework is designed to translate abstract theoretical concepts into empirically observable dimensions that enable systematic cross-case comparison. The key analytical dimensions and empirically defined indicators used in this study are explicitly defined below and applied consistently across all case studies.

The comparative framework is organized around six key analytical dimensions, each operationalized through specific indicators:

- (1)

- Governance and institutional structure, examined through indicators such as the level of decision-making authority, degree of centralization, and responsible management bodies;

- (2)

- Community participation and stakeholder engagement, assessed through forms of involvement including employment, training, volunteering, and participation in educational or outreach activities;

- (3)

- Conservation and preservation practices, analyzed through the type of interventions implemented (e.g., restoration, stabilization, preventive conservation) and the presence of monitoring or risk-mitigation measures;

- (4)

- Tourism and visitor management, evaluated through visitor access control, interpretive strategies, infrastructure provision, and capacity management mechanisms;

- (5)

- Research, documentation, and education, examined through the scope of archaeological research, documentation practices, and public or educational programming; and

- (6)

- Cultural context and policy orientation, assessed through the influence of cultural values, national narratives, and policy frameworks on management priorities and implementation.

These dimensions were selected based on their prominence in heritage management scholarship and their relevance to the study’s theoretical framework. Governance theory informed the inclusion of institutional and decision-making criteria; values-based heritage management guided the focus on cultural context and stakeholder participation; and sustainable heritage tourism literature shaped the emphasis on visitor management and economic use. Together, these dimensions capture the core components through which cultural context is expected to shape archaeological site management, providing both analytical coherence and empirical relevance.

Operationally, the comparative framework was implemented by translating each analytical criterion into a set of observable indicators applied consistently across the three case studies. For example, governance structures were examined through indicators such as the degree of centralization, institutional responsibility, and decision-making authority; community engagement was assessed through forms of participation, employment roles, and involvement in management processes; and tourism management was analyzed through visitor control measures, interpretive strategies, and infrastructure provision. These indicators were derived from interview responses, site observations, and documentary sources, ensuring that each criterion was empirically grounded. Together, these indicators were applied consistently across all three case studies to provide a transparent and standardized basis for empirical comparison.

Each indicator was examined within and across cases using the same coding categories, allowing for systematic comparison. Evidence for each indicator was extracted from the qualitative dataset and summarized at the site level before being compared across cases. This procedure ensured that similarities and differences among sites reflected analytically comparable dimensions rather than narrative description, strengthening the rigor of the comparative assessment.

The comparative criteria employed in this framework were derived directly from the theoretical perspectives outlined in Section 1 and Section 1.1, translating abstract concepts from governance theory, values-based heritage management, and sustainable tourism into operational analytical dimensions. This approach ensures that comparison across sites is not merely descriptive, but analytically grounded, allowing cultural context to be examined as an explanatory variable shaping management priorities, institutional arrangements, and stakeholder engagement.

Moreover, the framework incorporates a historical and socio-cultural perspective to elucidate the broader context in which site management practices develop. By exploring historical legacies, cultural norms, and socio-economic dynamics, researchers can uncover the underlying drivers and influences on management strategies. This contextual understanding helps explain variations in management practices and outcomes observed across different cultural contexts.

Additionally, the framework underscores the significance of stakeholder perspectives and community involvement in shaping site management practices. By incorporating viewpoints from site managers, local communities, government authorities, and other stakeholders, researchers can evaluate the effectiveness of management strategies and identify avenues for collaboration and enhancement. This participatory approach ensures that the comparative analysis is rooted in the experiences and aspirations of those directly engaged in site management.

The comparative framework offers a structured method for examining site management practices, enabling researchers to pinpoint best practices, challenges, and opportunities across diverse cultural contexts. Through systematic comparison, researchers can generate insights that inform theory-building, policy formulation, and practical recommendations for advancing archaeological site management on a global scale.

The outcomes of this analytical process are presented in Section 4, where results are structured in direct relation to the research questions and comparative criteria. Section 4 is structured according to these operationalized criteria, with comparative findings presented for each analytical dimension to ensure consistency between the framework and empirical outcomes.

Each dimension and its associated indicators were applied uniformly across the three case studies using triangulated qualitative evidence from interviews, site observations, and documentary sources, as illustrated schematically in Figure 1. This ensured that comparisons were conducted on analytically equivalent terms rather than narrative description. Differences and similarities identified in the Results Section 4 therefore reflect variation across standardized criteria, enhancing the transparency, comparability, and scientific validity of the analysis.

4. Results

This section presents empirical findings derived from interviews, site observations, and documentary analysis. Results are reported descriptively and comparatively, while interpretation and theoretical explanation are reserved for Section 5. All comparative statements presented in this section are grounded in triangulated evidence from interviews, site observations, and documentary analysis, as summarized in Table 2 and detailed in Appendix A.

Table 2.

Analytical comparison of archaeological site management practices across the three case studies, based on standardized comparative indicators.

4.1. Overview of Comparative Patterns

According to the observation of the three sites and the analysis of secondary data, Table 2 summarises the results concerning the management of them.

Comparison across these indicators reveals both patterned similarities and differences, suggesting that bureaucratic and hierarchical governance systems may share common structural characteristics that shape management practices, alongside context-specific variations. Centralized governance structures at Giza and Madāʾin Ṣāliḥ correspond with more institutionally controlled participation models, whereas the more distributed governance structure at Al-Ain is associated with broader forms of community engagement. These relationships provide an analytical basis for examining how cultural context and governance interact to shape management outcomes, which is further explored in Section 5.

The results are presented in relation to the three research questions, focusing on governance arrangements, culturally shaped management practices, and cross-case comparative patterns. For each criterion, empirical evidence from interviews, observations, and documents was compared across sites using the same indicators defined in the comparative framework.

The three cases demonstrate different systems of governance. The Giza necropolis is managed by the Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities, particularly the Supreme Council of Antiquities (SCA), which maintains tight control over all activities in the area. For Mada’in Saleh, it is governed by the Saudi Commission for Tourism and National Heritage (SCTH) through strong centralisation. It is responsible for controlling all activities and ensuring they align with the 2030 vision and the national tourism Expansion. Al-Ain demonstrates a different system as it is controlled by the Department of Culture and Tourism, Abu Dhabi. It leverages experts across IT, urban planning, and site management to manage the area and implement the Emirate’s objectives that align with the national cultural strategy. The three sites exhibit different governance arrangements and conservation practices. At Giza, conservation activities focus on erosion control, pollution mitigation, and documentation programs. At Madāʾin Ṣāliḥ, conservation efforts emphasize stabilization of rock-cut features and erosion management. At Al-Ain, conservation activities include preventive maintenance across tombs, irrigation systems, and associated landscape elements.

4.1.1. Tourism and Visitor Management

The Giza Necropolis has a well-developed tourism infrastructure, including visitor centers, pathways, and interpretive signage. Managing high visitor numbers and ensuring sustainable tourism practices remain significant challenges. Recent efforts at Madain Saleh focus on developing tourism infrastructure, including visitor centers and guided tours, as part of broader national tourism initiatives. Emphasis is placed on sustainable tourism to minimize environmental impact and enhance the visitor experience. The Al-Ain sites feature developed visitor facilities, educational programs, and guided tours to enhance visitor engagement. There is a strong focus on sustainable tourism practices to ensure that visitor access does not compromise site integrity.

4.1.2. Community Involvement and Engagement

Giza Necropolis local communities are involved through employment in tourism and conservation projects. Community engagement initiatives aim to foster local stewardship of the site. Madain Saleh local communities participate through employment opportunities and cultural heritage awareness programs. Collaboration with local stakeholders ensures that the benefits of tourism are shared with surrounding communities. The management of Al-Ain actively involves local communities in site management and tourism activities. Community-based tourism initiatives and cultural heritage programs promote local involvement and benefit-sharing.

4.1.3. Research and Documentation

Giza is a hub for extensive archaeological research and international collaboration. The site is well-documented, with ongoing studies enhancing understanding and preservation. There is a significant focus on archaeological research at Madain Saleh to uncover and document the Nabatean civilization. Collaboration with international researchers enhances site documentation and knowledge dissemination. Al-Ain is an active research site with ongoing archaeological studies and documentation efforts. Collaboration with local and international experts expands understanding of the region’s historical and cultural significance.

4.1.4. Educational and Interpretive Programs

Giza has robust public education programs, including school visits, workshops, and exhibitions. Extensive interpretive materials educate visitors about the site’s history and significance. Madain Saleh’s educational programs and materials are developed as part of broader efforts to promote cultural heritage awareness. Interpretive signage and guided tours enhance visitor understanding and engagement. Al-Ain offers comprehensive educational programs for schools and the general public. Rich interpretive materials, including interactive displays and guided tours, engage visitors.

4.1.5. Cultural Context and Influence

Management practices at Giza are influenced by Egypt’s profound reverence for its ancient heritage and national pride. Efforts balance tourism with conservation, reflecting the cultural importance of the site. The management of Madain Saleh is shaped by Saudi Arabia’s Islamic values and conservative traditions, reflecting national priorities for heritage preservation and economic diversification through tourism. In the UAE, there is an emphasis on preserving cultural heritage as a source of national identity and pride. Efforts balance heritage preservation with tourism development, aligning with the UAE’s cultural values and economic goals.

4.1.6. Economic Impact and Funding

Tourism at Giza provides significant economic benefits, with funds reinvested in conservation and site management. Major projects rely on government funding and international support. Tourism development at Madain Saleh aligns with national strategies for economic diversification. Government funding and private investment support site management and development initiatives. The economic impact from tourism and heritage preservation at Al-Ain contributes to local and national economies. Government funding is supplemented by tourism revenue and international collaboration.

4.1.7. Challenges and Threats

Giza Necropolis’s major challenges include pollution, urban encroachment, and managing high visitor numbers. Strategies are in place to address these threats through comprehensive conservation and sustainable tourism practices. Madain Saleh faces environmental threats such as erosion and weathering, as well as the need to balance tourism with preservation. Sustainable preservation techniques and proactive management address these challenges. Al-Ain faces threats from urban development, environmental factors, and the impact of tourism. Emphasis on sustainable practices and community engagement helps mitigate these threats. While all three sites share goals of preservation, research, and tourism development, their management practices are tailored to their unique cultural contexts and challenges. The Giza Necropolis benefits from long-established heritage laws and international collaboration but faces significant urban and environmental pressures. Madain Saleh’s management aligns with Saudi Arabia’s national strategies for heritage and tourism, focusing on sustainable preservation amid environmental threats. The Al-Ain Archaeological Sites integrate comprehensive conservation efforts with active community engagement and educational programs, balancing heritage preservation with tourism development in a rapidly growing urban environment.

4.2. Influence of Cultural Contexts on Management Practices

Analysis of field observations, interview data, and documentary sources indicates that cultural context plays a decisive role in shaping management priorities and operational practices across the three case studies. While all sites operate within broadly similar regional and institutional environments, clear differences emerge in how governance, conservation emphasis, tourism management, and community engagement are implemented. These differences are summarized below based on comparative evidence rather than site description.

4.2.1. Giza Necropolis

Results indicate that management practices at the Giza Necropolis are characterized by strong centralization and a high prioritization of monument protection and visitor management. Data from observations and interviews show that conservation activities and visitor infrastructure receive significant institutional attention, reflecting the site’s national symbolic importance. Interview data from government officials and site professionals consistently emphasized the centralized nature of decision-making. As one interviewee explained, “management decisions are taken at the national level, and local involvement is mainly limited to operational roles” (Interviewee, Egypt). Observation notes corroborate this pattern, documenting the presence of local workers primarily in visitor services and site maintenance rather than in planning or interpretive activities. Documentary materials, including official management guidelines, further indicate that community participation is framed largely in terms of employment rather than shared governance.

4.2.2. Madāʾin Ṣāliḥ (Saudi Arabia)

Findings from Madāʾin Ṣāliḥ reveal a management approach closely aligned with nationally defined cultural and development frameworks. Management decisions related to access, interpretation, and visitor behavior reflect sensitivity to religious and cultural norms, as reported consistently across interviews and observations. The data also show a strong linkage between site management and broader economic diversification objectives, with increasing emphasis on structured tourism development. Interview responses from heritage officials and local stakeholders indicate that community participation at Madāʾin Ṣāliḥ is structured through formal training and employment programs linked to national tourism initiatives. One participant described these programs as “carefully managed to align with national heritage and tourism objectives.” Site observations confirm the presence of guided access systems and staff-mediated visitor interactions, while policy documents associated with Vision 2030 outline community engagement primarily as a capacity-building and employment mechanism rather than a participatory governance model.

4.2.3. Al-Ain Archaeological Sites (United Arab Emirates)

Evidence from interviews, site observations, and institutional documents indicates that community participation at the Al-Ain Archaeological Sites takes multiple formalized forms. One interviewee noted that “community programs focus on education and volunteering rather than shared decision-making authority” (Interviewee, UAE). One interviewee noted that “community programs focus on education and volunteering rather than shared decision-making authority” (Interviewee, UAE). Interview data highlight local employment in heritage-related roles, while observation notes document volunteer programs, educational activities, and public heritage events organized in collaboration with local institutions. Documentary sources, including management plans and public outreach materials, further indicate structured mechanisms for community involvement in education and heritage promotion. These findings demonstrate an expanded participation model relative to the other cases, though final decision-making authority remains institutionally centralized. Interview responses and documentary materials also indicate that economic benefits associated with tourism are primarily distributed through employment opportunities, training programs, and locally oriented educational initiatives rather than through formal revenue-sharing arrangements.

Across the three sites, cultural context influences management primarily through:

- (i)

- the degree of centralization in decision-making;

- (ii)

- the role assigned to local communities; and

- (iii)

- the balance between conservation and tourism development.

While Giza and Madāʾin Ṣāliḥ exhibit more state-centered management models with limited participatory mechanisms, Al-Ain demonstrates a comparatively collaborative approach with greater emphasis on community engagement and education.

Across the three cases, stakeholder perspectives reveal contrasting expectations regarding participation. Interviews with local actors at Giza and Madāʾin Ṣāliḥ often framed involvement in economic terms, particularly employment and training opportunities, whereas participants associated with Al-Ain more frequently emphasized educational and cultural engagement. These differences suggest that stakeholder interpretations of participation are shaped by institutional context and governance traditions, rather than by uniform community aspirations.

4.3. Comparative Analysis

This section constitutes the central analytical core of the study, bringing together empirical findings from the three case studies to examine how cultural context and governance structures shape archaeological site management practices. Rather than reiterating site descriptions, the analysis focuses on systematic cross-case comparison across governance arrangements, community participation, and conservation tourism dynamics, using the standardized indicators defined in the comparative framework.

4.3.1. Governance Structures and Decision-Making

A primary axis of comparison across the three sites concerns governance structure and the distribution of decision-making authority. The Giza Necropolis and Madāʾin Ṣāliḥ are both managed through highly centralized governance systems, with strategic decisions taken at the national level by specialized heritage authorities. Interview and documentary evidence indicates that these centralized arrangements emphasize administrative control, regulatory consistency, and monument protection, with limited delegation of decision-making responsibilities to local actors.

In contrast, governance at the Al-Ain Archaeological Sites is organized through a multi-departmental structure at the emirate level, involving heritage authorities, educational institutions, and urban planning bodies. While final authority remains institutional, interview data and observation records indicate a higher degree of inter-institutional coordination compared with the other cases. This governance configuration facilitates integration between conservation, education, and urban development, though it does not constitute formal shared governance with local communities.

Comparatively, these findings indicate that governance centralization functions as a key structuring variable influencing management priorities and stakeholder roles. Centralized systems are associated with tighter institutional control and narrower participation channels, whereas more distributed administrative arrangements enable coordination across sectors while maintaining centralized authority.

4.3.2. Community Participation and Benefit-Sharing

Community participation exhibits clear variation across the three cases when examined comparatively. At Giza and Madāʾin Ṣāliḥ, participation is primarily structured around employment-based involvement. Interview data indicate that local actors are mainly engaged in tourism services, site maintenance, and support roles, with limited involvement in planning, interpretation, or strategic decision-making. Observation notes corroborate this pattern, documenting community presence largely in operational rather than managerial capacities.

Interview data reveal variation within community perspectives themselves. Participants identified as community members differed in educational background, economic position, and degree of institutional affiliation. For example, interviewees with formal academic training and leadership roles within local heritage initiatives emphasized educational outreach and cultural representation, whereas locally based business owners and tourism practitioners highlighted economic opportunities and livelihood concerns. These differences were treated analytically as intra-community variation rather than inconsistencies, illustrating the heterogeneous nature of community stakeholder interests.

At Al-Ain, community participation takes a broader institutional form. Evidence from interviews, site observations, and documentary sources points to structured participation mechanisms that include employment, volunteering, educational partnerships, and public outreach programs. While these mechanisms expand opportunities for local involvement beyond economic participation alone, they operate within institutionally designed frameworks rather than shared management arrangements.

From a comparative perspective, benefit-sharing across the three sites is primarily mediated through employment and capacity-building rather than direct revenue-sharing or co-management. The form and scope of participation observed reflect governance traditions and cultural expectations rather than uniform policy prescriptions, underscoring the contextual nature of community engagement in archaeological site management.

4.3.3. Conservation and Tourism Trade-Offs

The comparative analysis also reveals contrasting approaches to balancing conservation and tourism across the three sites. Giza experiences sustained pressure from high visitor volumes, leading to management strategies focused on visitor flow regulation, infrastructure control, and monument stabilization. Interview and documentary evidence indicate that conservation priorities are closely linked to managing the impacts of mass tourism and urban proximity.

Madāʾin Ṣāliḥ, while experiencing increasing tourism, employs a more controlled access model characterized by guided visitation and regulated movement within the site. Observation records indicate that these measures are designed to mitigate environmental and cultural impacts while supporting tourism development aligned with national policy objectives.

At Al-Ain, conservation practices are more strongly oriented toward preventive and landscape-based approaches. Management strategies emphasize long-term maintenance, controlled visitation, and integration with broader urban planning frameworks. Educational and interpretive programs play a more visible role in visitor management, reflecting a conservation model that prioritizes learning and controlled access over high visitor throughput.

Comparatively, these differences illustrate how conservation–tourism trade-offs are shaped by governance capacity, cultural values, and policy priorities. Rather than reflecting universal best practices, the observed strategies demonstrate context-specific responses to shared management challenges.

4.3.4. Cross-Case Analytical Synthesis

Taken together, the comparative analysis demonstrates that differences across the three archaeological sites are not incidental but reflect patterned relationships between cultural context, governance structure, and management outcomes. Centralized governance systems are associated with narrower participation mechanisms and stronger institutional control over conservation and tourism decisions, whereas more distributed administrative arrangements enable broader though still structured forms of community engagement and cross-sector coordination.

These findings confirm that cultural context operates as a structuring force shaping how governance, participation, and conservation priorities are configured in practice. By concentrating comparative interpretation within this section, the analysis clarifies how cultural values and institutional traditions mediate archaeological site management, providing a coherent analytical foundation for the theoretical discussion that follows.

5. Discussion

The discussion that follows is structured around the key comparative indicators applied consistently across the three case studies, namely: governance and decision-making structures, community participation and benefit-sharing mechanisms, conservation practices, tourism management strategies, and the role of cultural context in shaping management priorities. These indicators provide the analytical framework through which cross-case similarities and differences are interpreted.

These interpretations are grounded in triangulated interview testimony, observation records, and documentary evidence, rather than relying solely on descriptive case comparison.

5.1. Cultural Context and Management Practices

This study demonstrates that cross-cultural variation in archaeological site management reflects structured relationships between governance arrangements, stakeholder participation, and negotiated heritage values rather than isolated contextual differences. The comparative findings show that decision-making authority and participation mechanisms are shaped by institutional and political frameworks, while heritage values are produced through interactions between state agencies, professionals, and local communities. This integrated perspective reduces redundancy while clarifying how governance and values-based management jointly influence management outcomes [3].

5.2. Challenges and Future Directions

While significant strengths are evident in the management practices of the three case studies, challenges persist. High visitor numbers, urban development pressures, and environmental threats underscore the need for effective visitor management, urban planning, and resilient conservation techniques. Future research should focus on innovative solutions, including leveraging technology for site monitoring and conservation, enhancing visitor management systems, and assessing the long-term socio-economic impacts of heritage tourism on local communities. Additionally, increased international collaboration can facilitate knowledge exchange and capacity building for more sustainable site management practices.

Overall, the Discussion demonstrates that cultural context functions as an explanatory variable linking governance structures to archaeological site management outcomes. By moving beyond descriptive comparison, the analysis clarifies how institutional authority, cultural values, and stakeholder engagement interact in practice. These findings contribute to comparative heritage management scholarship by offering empirically grounded insight into the governance culture nexus.

5.3. Limitations and Future Research

This study has several limitations that should be acknowledged. First, the analysis is based on a qualitative dataset derived from three archaeological case studies, which limits the generalizability of the findings beyond comparable cultural and institutional contexts. Second, while triangulation across interviews, site observations, and documentary sources enhanced analytical rigor, the study did not incorporate quantitative indicators of management performance or long-term longitudinal data. Third, although the selected sites offer meaningful cross-cultural contrast, additional cases from other regions could further test and refine the proposed comparative framework.