Abstract

Despite its status as a heritage model, Suzhou’s Pingjiang Historic Block suffers from a significant “conservation deficit”. The current study quantifies this decay and identifies its socio-economic drivers through a field survey of 517 traditional residences and a multivariate analysis of 188 resident households. The results reveal widespread degradation, including 32% roof damage and 55% unauthorized window replacements. Binary logistic regression identifies institutional status (hukou) as the decisive predictor of housing integrity (β = −0.544). Non-local migrants, trapped by tenure insecurity, exhibit significantly higher damage rates (53.5%). In contrast, local residents, driven by an “Aging Trap” and thermal comfort needs, are the primary drivers of adaptive window replacements (OR = 2.71). These findings indicate that current static policies are failing to address structural misalignments between preservation mandates and resident reality. The study advocates for a shift towards “Adaptive Integrity”, proposing tenure integration for migrants and technical retrofitting support for the aging local population to reconcile heritage protection with contemporary living needs.

1. Introduction

Over the past four decades, China has experienced an urban transformation unprecedented in its velocity and scale [1]. While this profound socioeconomic shift has reshaped metropolitan landscapes, it has also exerted immense pressure on the historic urban environments that embody the nation’s collective memory and cultural identity. Specifically, under an urban development model critically driven by ‘land-based financing’, many local governments have been inclined to implement ‘tear down and rebuild’ strategies for old-city transformations. Due to the commercial value of their central locations, historic districts have been cleared on a massive scale to make way for high-density commercial properties, modern residential housing, and new infrastructure. Within this mindset of prioritizing development over conservation, the preservation of cultural heritage has been subordinated to economic efficiency. In the face of this policy, countless historic districts have met the “unfortunate plight of demolition or irreparable damage” [2]. transforming heritage conservation from a purely cultural responsibility into an urgent matter demanding academic attention and practical action. In response to this need, national policy has officially pivoted from a paradigm of large-scale demolition to models emphasizing conservation, such as “organic renewal” [3].

Despite this shift in official discourse, a significant “policy-practice gap” has emerged, creating a persistent disconnect between conservation mandates and on-the-ground realities [4]. A typical example is the prevalence of ‘façadism’: under the policy slogan of ‘preserving historic character’, the on-the-ground practice in some localities has evolved into retaining only the street-facing façade of a building while completely demolishing its internal structure and historical spaces and replacing them with modern commercial functions. While this approach superficially fulfills the formal requirement for ‘retention’, it severely undermines the authenticity and integrity of the heritage. In addition, other systemic challenges also frequently undermine the implementation of heritage protection. For example, research indicates that China’s preventive conservation framework over-emphasizes the idealized role of routine maintenance, a theoretically sound approach that proves difficult to sustain in practice, with inspections and monitoring often failing to be implemented effectively [5]. This is compounded by complex and often unclear property rights that create a deadlock, hindering proper and timely maintenance of residential buildings [6].

The theoretical bedrock of heritage conservation rests upon the core principles of authenticity and integrity, which hold a central position in international charters and discourse [7]. These concepts, however, have undergone a complex reinterpretation within the Chinese context. The 1994 Nara Document on Authenticity advocated for a value-based and culturally relative interpretation, acknowledging that heritage is a living, evolving entity [7]. This has been refracted in China through a debate captured by two distinct understandings of “authenticity”: one emphasizes fidelity to an “original state,” while the other favors a more verifiable “truthfulness” that respects a building’s entire evolution [8]. The former aligns with the traditional restoration principle of “restoring the old as it was,” which can, in practice, justify extensive reconstruction to an idealized past [8]. Concurrently, the concept of integrity has expanded from a focus on singular monuments to the holistic preservation of the historic urban landscape, demanding the protection of all elements that constitute a heritage asset’s value, including its physical fabric, spatial structure, and social functions [9].

The current study focuses on the Pingjiang Historic Block in Suzhou (Figure 1). Suzhou’s achievements have been widely celebrated as a model city for heritage conservation, since its inclusion in China’s first cohort of National Famous Historical and Cultural Cities in 1982 [10]. Within this context, the Pingjiang Historic Block is widely regarded as the epitome of conservation success—it is “Suzhou’s oldest and most intact historic and cultural area”, perfectly embodying the quintessential charm of a southern Yangtze River water town [11]. Its esteemed status is confirmed by numerous accolades, including its designation as a “Famous Historical and Cultural Street of China” [12] and, notably, an Honorable Mention in the 2005 UNESCO Asia-Pacific Heritage Awards for Cultural Heritage Conservation [13]. The UNESCO jury commended the project as “a commendable example of integrated urban rehabilitation which has restored the physical, social and commercial fabric”, specifically praising its success in demonstrating “the feasibility of upgrading traditional housing stock to keep it in continuous use by the original residents, which maintains the authentic historic spirit of the place” [14].

Figure 1.

Location of Suzhou City and its Pingjiang History and Culture Block.

However, beneath this veneer of success lies a profound paradox. The very acclaim that has positioned Pingjiang as a conservation paradigm may have inadvertently masked a quiet and progressive decay within its private residential fabric. Existing scholarship on the block has provided valuable insights, primarily focusing on its revitalization as a tourism hub [2]. the negative impacts of commercialization and tourism gentrification [15]. and complex governance challenges [6]. Despite these contributions, the physical condition of the residential building stock itself has remained largely unexamined. The current study addresses this lacuna by investigating the existence of a significant and measurable “conservation deficit” between the acclaimed status of the Pingjiang Historic Block and the actual physical state of its constituent traditional residences.

This deficit is expressed through several critical material conditions that directly contravene established conservation principles and local regulations. First, there is widespread physical deterioration, which signals a failure of preventive conservation. Second, there is also a pervasive use of inappropriate modern repair materials, such as cement and aluminum alloys, which constitutes a severe breach of conservation ethics and undermines material authenticity. This practice directly violates the Regulations on the Protection of Suzhou National Historical and Cultural Cites [16] and Regulations on the Potection of Ancient Buildings in Suzhou [17], which mandate that repairs must adhere to official guidelines specifying the use of traditional materials, forms, and craftsmanship. Third, the proliferation of illegal structures represents a flagrant challenge to the principle of integrity, disrupting historically formed building typologies and the district’s urban texture [18].

The primary objective of this study is to provide quantitative evidence of the ‘policy–practice gap’ by systematically assessing the extent and severity of material decay and the prevalence of improper alterations within the traditional residential building stock of the Pingjiang Historic Block. By documenting and quantifying these conditions, the study aims to demonstrate a significant and measurable “conservation deficit”, using key indicators such as the incidence rates of specific damage types (e.g., roof, wall deterioration) and the proportion of buildings exhibiting non-compliant alterations. The specific objectives are:

- To quantitatively assess the physical vulnerability of the local architectural vernacular fabric through on-site field investigation, with a focus on material decay and non-compliant modifications.

- To statistically examine the relationship between building condition (damage to roofs, walls, doors, and windows, as well as non-compliant interventions) and user attributes (including hukou status, age, and residential motivation) using multivariate logistic regression models.

- To interpret the socio-spatial mechanisms underlying the “Conservation Deficit”, identifying the key factors influencing the maintenance of building envelopes.

- To propose an “Adaptive Integrity” framework that reconciles architectural preservation with the evolving needs of local communities, thereby narrowing the gap between formal conservation mandates and residents’ everyday living realities.

By providing a data-driven assessment of the material state of Pingjiang’s residential heritage, this study aims to provide an empirical counterpoint to existing qualitative and policy-focused studies [10]. furnishing a robust evidence base for planners and heritage managers to re-evaluate the efficacy of current monitoring and enforcement mechanisms [19].

2. Methodology

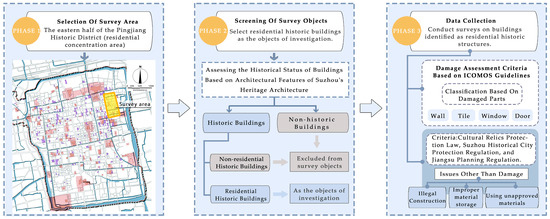

2.1. Research Methodological Framework

The research methodology has 3 phases (Figure 2), comprising the selection of the survey area and subjects, followed by the collection of current status data. Each phase was designed to logically build upon the previous one, ensuring a systematic progression from conceptual design to empirical analysis.

Figure 2.

Research Methodological Framework.

2.2. Survey Area and Subjects of Investigation

2.2.1. Survey Area

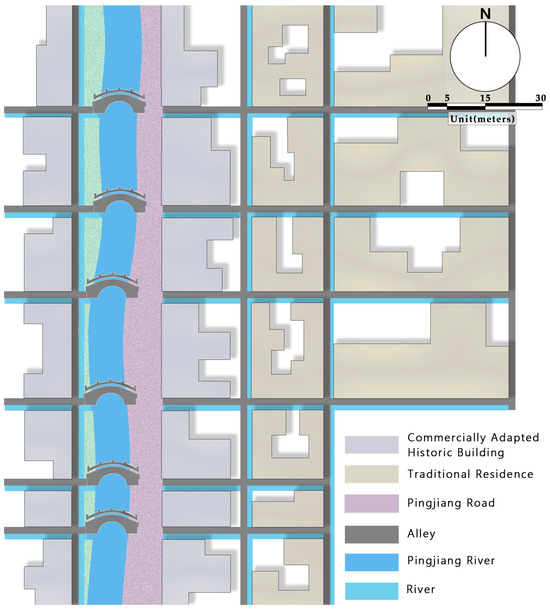

Field-based urban-heritage research characterizes Pingjiang’s overall form as a canal–street double-grid; however, its core residential features—comprising courtyard compounds, narrow lanes, and sequenced privacy gradations—remain most intact away from the main tourist corridor [14]. While Pingjiang Road itself has been reoriented toward consumption and tourism, the adjacent eastern lanes continue to host everyday domestic activities. Spatial-use studies document this sharp “tourism–residence” split, revealing significantly lower rates of commercial conversion in these back-street plots compared to the main thoroughfare (Figure 3) [20].

Figure 3.

The “parallel canal-street” double-grid pattern of the Pingjiang Historic Block.

The continuity of residence in these eastern plots is supported by specific property-rights arrangements and governance mechanisms that prioritize living-heritage conservation, thereby constraining wholesale redevelopment and preserving both the physical fabric and traditional patterns of use [21]. At a morphological level, studies using space-syntax and cultural-sustainability frameworks demonstrate that the social logics encoded within traditional residential plans—such as sequence, enclosure, and layered privacy—are observable primarily where these residential networks remain in daily use [22]. Crucially for this study, recent investigations into traditional residence redevelopment in Suzhou indicate that research conducted within these actively inhabited residential zones provides richer and more accurate evidence of actual building conditions and material decay than studies centered on the manicured façades of the main tourist corridors [23]. Consequently, Pingjiang’s eastern quarter (Figure 4) offers the most authentic example of the district’s historic morphology and serves as the optimal boundary for this investigation.

Figure 4.

Boundary of the Pingjiang Historic Block and Scope of the Survey Area.

2.2.2. Subjects of Investigation

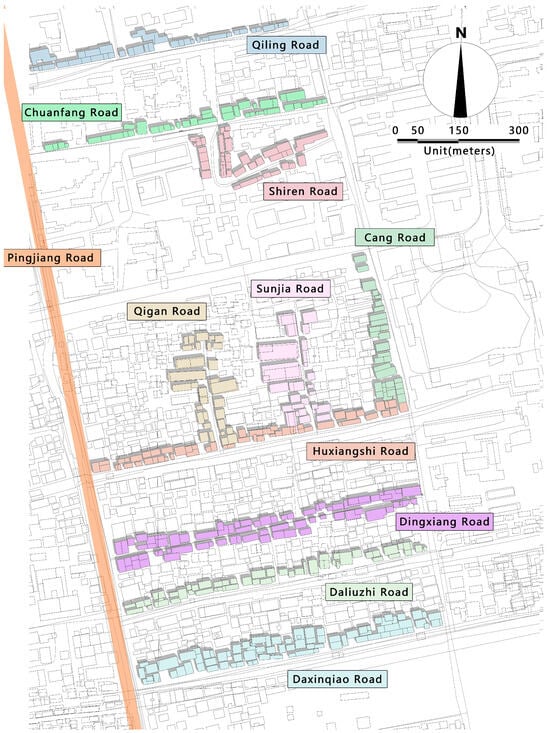

The survey was conducted in the Pingjiang Historical and Cultural Block, covering residences and their occupants located along Qiling Road, Chuanfang Road, Shiren Road, Cang Road, Qigan Road, Sunjia Road, Huxiangshi Road, Dingxiang Road, Daliuzhi Road, and Daxinqiao Road (Figure 5). A total of 576 buildings along these ten streets were surveyed.

Figure 5.

Distribution of Surveyed Objects within the Survey Area.

It is important to clarify that this study explicitly excludes buildings that have been converted for purely tourist or commercial uses (e.g., boutique hotels, shops, and cafes), even if they were historically dwellings. This exclusion is methodological, not accidental. Buildings converted to commercial use typically benefit from external capital injection and profit-driven maintenance regimes, often resulting in a state of “commercial gentrification” where material conditions are artificially maintained or significantly altered [2]. In contrast, our study aims to diagnose the vulnerability of the “living” vernacular heritage—properties that continue to function as everyday residences for the local community. These dwellings are subject to household-level economic constraints and are the primary victims of the “conservation deficit.” Therefore, excluding commercial conversions allows for a more precise assessment of the authentic residential crisis, avoiding the statistical distortion that well-funded commercial properties might introduce.

2.3. Architectural Survey

To assess the current condition of the historical residences in the Pingjiang Historical and Cultural Block, we first identified which buildings in the area meet the criteria for historical structures

2.3.1. Controlled Protection Architecture and Officially Designated Cultural Relics Protection Units in Suzhou

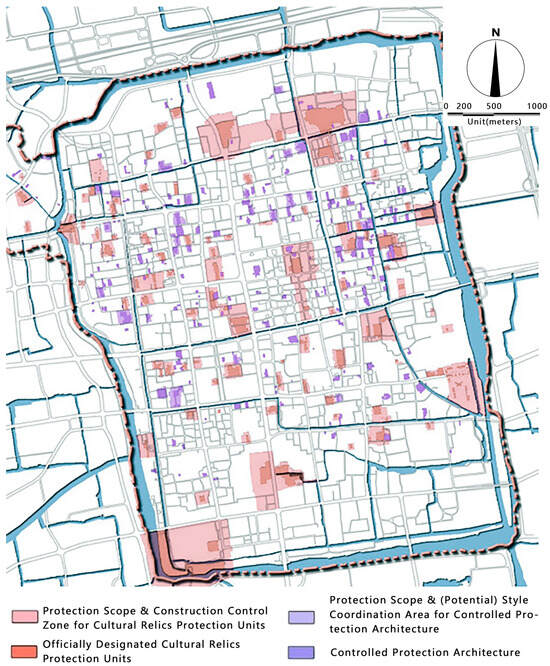

In Suzhou, the preservation of historical buildings is formally governed by two primary official classifications: Officially Designated Cultural Relics Protection Units and Controlled Protection Architecture [24,25] These categories are distinct, differing significantly in their legal basis, level of protection, and the regulations governing their alteration and maintenance. Figure 6 illustrates the spatial distribution of these two types of protected buildings within the Pingjiang Historic District, while the following tables (Table 1 and Table 2) [24,25,26,27] provide a comprehensive comparison of their regulatory frameworks.

Figure 6.

Distribution of Controlled Protection Architecture and Cultural Relics Protection Units in Suzhou City.

Table 1.

Classification Criteria for Controlled Protection Architecture and Cultural Relics Protection Units.

Table 2.

Classification Criteria for the Designation of Controlled Protection Architecture and Cultural Relics Protection Units.

However, these official designations do not encompass the entirety of the district’s historic fabric. A substantial proportion of the traditional building stock consists of “undesignated historic buildings”—vernacular dwellings that, while lacking high-level statutory protection, constitute the essential background texture of the historic district. Their exclusion from strict preservation mandates means they are especially vulnerable to material decay and ad hoc alterations. Therefore, to obtain a truly representative assessment of the district’s condition, this study extends its scope beyond the officially listed monuments to explicitly include these widespread, yet often overlooked, undesignated historic residential buildings.

Buildings officially designated by the Suzhou Municipal Government as cultural relic protection units and Controlled Protection Architecture were identified by their “protected unit” plaques (Figure 7). Since these are officially designated historic building units, they can be directly recognized as historical architecture.

Figure 7.

Identification Plaques for Controlled Protection Architecture and Officially Designated Cultural Relics Protection Units.

2.3.2. Traditional Residential Architecture of Suzhou

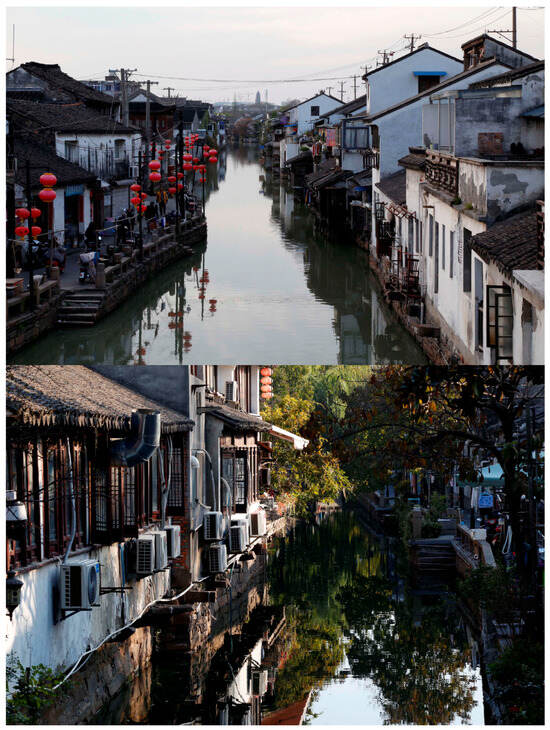

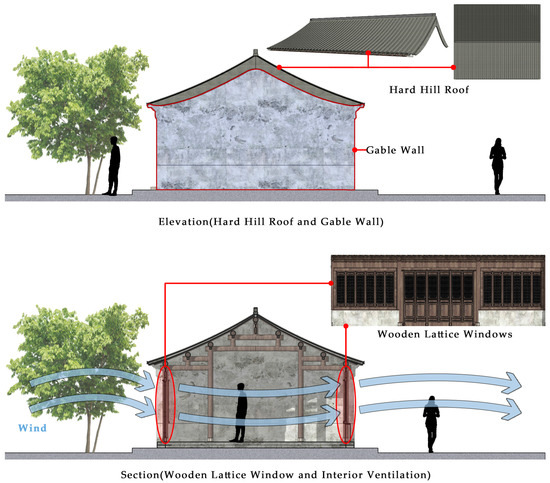

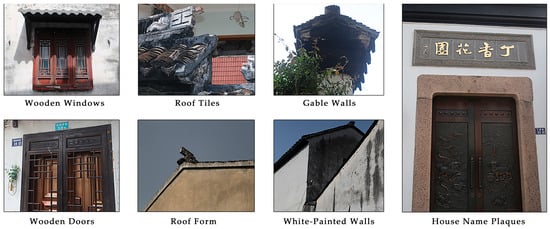

The traditional residential architecture of Suzhou (Figure 8) is characterized by a distinct morphological and functional typology. Visually, the building stock is defined by a consistent material palette of white lime-washed walls and grey clay roof tiles. Key architectural elements—including wooden lattice windows, ‘hard hill’ roofs (yingshan), and raised gable walls—serve functions that extend beyond ornamentation (Figure 9). These features constitute a strategic adaptation to the regional climate and the high-density urban fabric, facilitating natural ventilation, rainwater drainage, and fire prevention. Furthermore, these architectural components function as socio-cultural signifiers, articulating residents’ social status and family lineage through specific details such as plaques and symbolic motifs.

Figure 8.

Traditional Suzhou Residence (photographed by the author).

Figure 9.

Elevation and Section Drawings of Traditional Suzhou Residential Architecture.

The specific characteristics of these key architectural components, and their functional and cultural importance, are explained in Table 3 and Figure 10 [28,29,30,31,32].

Table 3.

Architectural Features of Traditional Residences in Suzhou.

Figure 10.

Architectural Characteristics of Traditional Residential Buildings in Suzhou.

Traditional architecture embodies local cultural symbols and serves as a medium through which communities preserve their religious and cultural identities [33]. In Suzhou, the different building types—whether residential, palace houses, temples, or government offices—follow a consistent structural form, though the degree of decorative detail varies considerably. Residential buildings, in particular, typically display minimal decoration [34,35,36]. In accordance with the Regulations on the Protection of Historic and Cultural Cities of Suzhou, any structure within a historical district that displays traditional Suzhou architectural characteristics (Table 3 and Figure 9) is recognized as a historical building [25]. In the current study, a building was classified as local historical architecture if it exhibited any of the distinctive features of Suzhou-style historic design.

2.3.3. Damage Assessment Criteria and Methodology

For each building classified as a historic residence, an evaluation of its condition was performed by inspecting key exterior elements—such as walls, roof tiles, doors, and windows. Due to privacy restrictions (because many residents do not permit interior access), only the external conditions were analyzed.

It is important to clarify that this focus on the building envelope does not endorse the ‘façadism’ criticized earlier in this study. On the contrary, for traditional timber-frame and masonry structures in Suzhou’s humid climate, the integrity of the external envelope—specifically the roof and load-bearing walls—is the primary determinant of internal habitability and structural safety. External decay in these vernacular typologies serves as a reliable diagnostic proxy for systemic neglect; visible damage to the ‘shell’ inevitably indicates compromised living conditions within. Furthermore, to mitigate the limitations of a purely external survey, this study integrates a resident questionnaire (Section 2.4) to capture the internal ‘lived reality’ that physical inspection alone could not access.

To systematically evaluate the extent of external damage to historic residences, the survey adopted a multi-tiered approach based on international conservation principles, Chinese regulations, and technical standards:

Assessment Criteria:

International Standards:

- Venice Charter (1964): Emphasizes minimal intervention and the preservation of original materials and structural integrity [37].

- Damage Assessment Criteria Based on the ICOMOS Guidelines General Principle: Any change that alters the original material properties, compromises structural stability, or causes irreversible impact to historical appearance is classified as “damage” [37].

- Chinese Regulations: Suzhou Protection Regulations: Prioritize authenticity in repairs and prohibit unauthorized alterations to facades [25].

To operationalize these standards for a non-intrusive field survey, this study adopts a binary assessment protocol—recording the presence or absence of decay rather than attempting to quantify its graded magnitude. This approach enhances data objectivity and reproducibility by avoiding the subjectivity inherent in visually estimating structural severity from exterior inspection. More fundamentally, within the context of preventive conservation, the mere existence of visible decay on key architectural elements—whether walls, roof tiles, or fenestration—constitutes sufficient evidence that the mandatory routine maintenance mechanisms have failed. Therefore, mapping the prevalence of these binary “damage instances” provides a robust and accurate indicator of the systemic “policy-practice gap” (Figure 11).

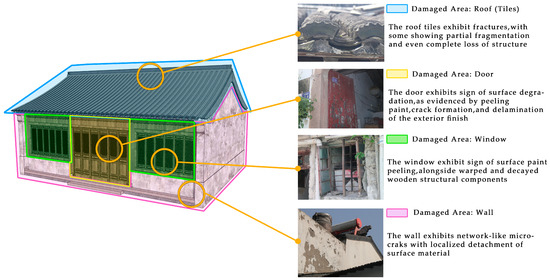

Figure 11.

Schematic Diagram of Damaged Residential Building Components.

2.4. Residents Survey

Following the damage assessment survey, a survey was conducted among the residents of these historic buildings to collect data on household size, registration status, housing arrangements, reasons for residency, and age distribution. Data were collected from residents of 188 households in the Pingjiang Historical and Cultural Block, covering both respondents and their cohabitants. In total, information on 473 individuals was obtained and subsequently incorporated into the analysis. Information provided by the respondents about themselves and their cohabitants was subsequently incorporated into the analysis.

To systematically quantify the correlation between resident characteristics and heritage decay, this study adopted a two-stage statistical approach.

First, Pearson’s Chi-Square Test was employed to determine the independence between categorical demographic variables (specifically hukou status) and housing conditions (damaged vs. undamaged), as well as unauthorized modification behaviors. The statistic is calculated as follows:

where Oi represents the observed frequency in each category, and Ei represents the expected frequency under the null hypothesis of independence.

Second, Binary Logistic Regression Models were constructed to isolate the independent effect of specific variables, while controlling for potential confounders. These models predict the probability (P) of a specific outcome (e.g., housing damage or window replacement) based on multiple independent variables. The log-odds (logit) of the dependent variable is expressed as:

where:

- P is the probability of the event occurring (Y = 1).

- β0 is the intercept.

- Xi represents the predictor variables (e.g., hukou status, age).

- βi represents the regression coefficients measuring the effect size of each predictor.

Finally, an Independent Samples t-test was used to compare the mean ages of residents in damaged versus undamaged housing within specific hukou groups, determining if physiological aging is a significant factor in maintenance capacity.

3. Results

3.1. Architectural Survey Results

3.1.1. The Proportion of Historic Residences

The initial building survey data (Table 4) paints a picture of an exceptionally intact historical landscape. Historic buildings constitute a remarkable 94% of all the 576 structures surveyed, with specific arteries such as Cang Road (100%) and Shiren Road (97%) exhibiting near-total retention of their original architectural fabric. This high concentration of heritage assets objectively substantiates the definition of the block as a “well-preserved architectural context”, highlighting its immense value as a unified repository of traditional urban morphology.

Table 4.

Distribution of Historic Building Proportions.

However, while the initial building survey data presents a positive picture, an examination of the residential usage of these historical buildings (Table 5) reveals a critical divergence between architectural form and social function. While the overall stock remains largely residential, specific streets display a sharp decline in domestic habitation. The most illustrative case is Cang Road: despite maintaining 100% historic architectural status, only 44% of these structures currently function as residences, suggesting a widespread conversion of historic houses into commercial enterprises. While adaptive reuse is a common strategy for revitalization, when such repurposing is heavily skewed toward tourist accommodation and consumption, it often signals a trajectory of intensified commercialization and tourism-driven gentrification [38,39,40].

Table 5.

Rate of Residential Occupancy in Historic Buildings.

This process is not uniform across the district. Streets such as Chuanfang Road (93%), Shiren Road (97%), and Dingxiang Road (94%) maintain a high proportion of residential use of the historic buildings, suggesting that the residential character of these areas has remained relatively stable. The spatial variation in the district highlights the fact that the pressures of tourism and commercial development are concentrated in specific areas like Cang Road. The conversion of residential properties in prime locations often produces tourism-driven gentrification, displacing original residents and thereby altering the social fabric and community continuity of historic neighbourhoods [41,42,43]. The data therefore reveals a core challenge for the Pingjiang block: balancing the economic benefits of tourism and adaptive reuse with the preservation of the district’s authentic residential life and social structure.

3.1.2. The Extent of Damage to Historic Residences

The survey covered 517 historic residences within the Pingjiang historic district. The data presented in Table 6 provides a quantitative summary of the observed physical conditions (Figure 12). Among the recorded defects, the most frequently identified issue was damage to roof tiles. This is followed in descending order of prevalence by damage to walls, windows, and doors, respectively.

Table 6.

Summary of Damage to Historic Residence Structural Components.

Figure 12.

Examples of Typical Damage to Historic Residence Structural Components.

The roof tile damage occurred on many of the surveyed buildings throughout the whole district, especially on Chuanfang Road and Qiling Road where around half of the historic houses (56% and 49%, respectively) suffered from this issue. It should be noted that the high incidence of roof degradation is not limited to this historical district; it is widespread throughout the Jiangnan region, where traditional timber-framed roof structures and small-sized clay tiles are particularly vulnerable to humid subtropical climates characterized by abundant rainfall and high humidity [44,45,46].

Wall and window damage also present significant conservation challenges. On Qiling Road, 38% of the residences showed wall damage, while 33% of residences on Chuanfang Road had damaged windows. The deterioration of wooden components like windows and doors is often a direct consequence of the region’s climate. The high moisture content in the air creates favorable conditions for fungal growth and insect infestation, which are primary agents of wood decay in historic buildings in Southern China [47]. This is further exacerbated by a lack of regular maintenance, which is a common issue in many historic districts.

Interestingly, the data reveals a significant disparity in the condition of residences across different streets. For example, Cang Road stands in stark contrast to other areas, with no recorded wall or door damage and minimal tile and window damage (6% each).

In conclusion, the data from the 517 surveyed residences in Pingjiang paints a concerning picture of the state of its built heritage. The high prevalence of tile and wall damage, in particular, points to an urgent need for comprehensive conservation strategies that address both the material-specific challenges posed by the local climate and the broader socio-economic pressures shaping the future of this historic district.

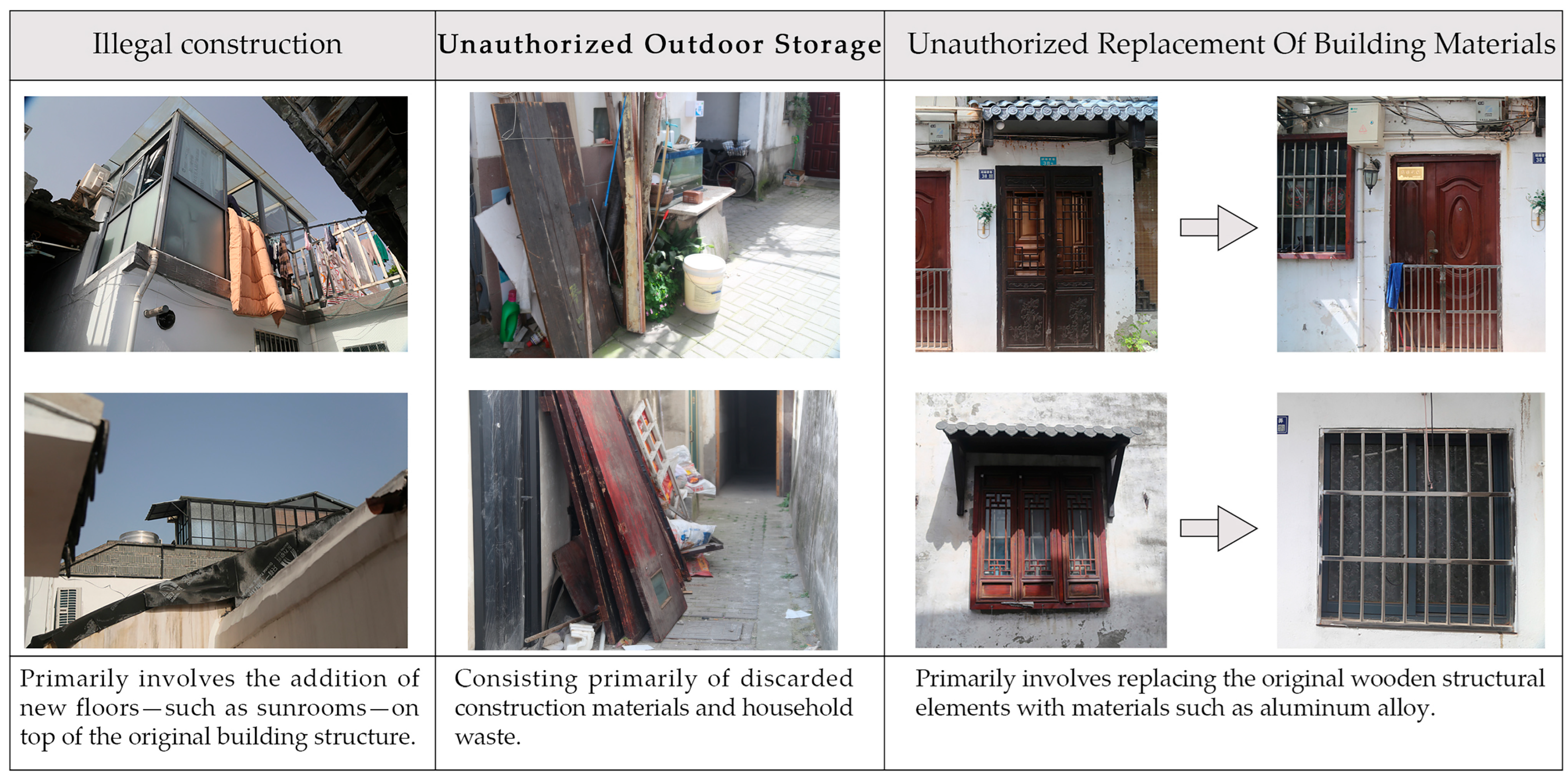

3.1.3. Analysis of Habitation Challenges

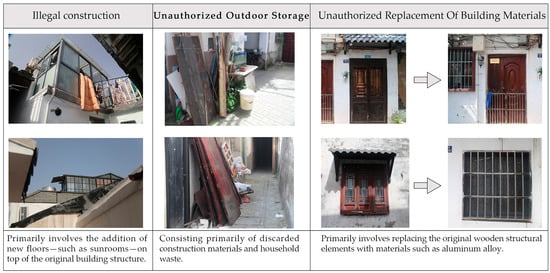

The data presented in Table 7 highlights the tension between heritage conservation regulations and the practical living requirements (Figure 13) of residents within Suzhou’s Pingjiang Historical and Cultural Block.

Table 7.

Quantitative Data on Unauthorized Modifications in Historic Residential Buildings.

Figure 13.

Types of Unauthorized Modifications in Residential Buildings.

The most striking finding is the prevalence of door and window replacements, which affects a majority (55%) of the 517 historic residences surveyed. This particular modification far outstrips other violations such as unauthorized outdoor storage (18%) and illegal construction (7%).

Furthermore, the data indicates a significant spatial disparity in the distribution of these violations. Qiling Road and Chuanfang Road emerge as hotspots, with door and window replacement rates reaching an alarming 92% and 88%, respectively. These two roads also exhibited the highest instances of illegal construction. Conversely, Cang Road did not have any recorded violations.

3.2. Residents’ Survey Results

3.2.1. Hukou Stratification and Housing Integrity

The Chi-square test reveals a significant dependency between hukou status and housing integrity. As shown in Table 8, housing damage is disproportionately concentrated within the non-local population. The observed frequency (O) of damage among migrants (53 households) significantly exceeds the expected frequency (E), whereas local residents show a damage rate of only 25.8%.

Table 8.

Cross-tabulation of Hukou Status and Housing Damage.

3.2.2. Determinants of Decay: Multivariate Logistic Regression

To control for the potential confounding effect of age, a binary logistic regression was performed. Based on the calculated coefficients (β), the final prediction equation for housing damage in the Pingjiang District is:

The strong negative coefficient for hukou status (β = −0.544) indicates that possessing a local hukou reduces the risk of housing damage. The model shows that hukou is a statistically significant predictor of housing damage (Table 9, p < 0.01) with an Odds Ratio of 0.580. This implies that, keeping age constant, local residents are approximately 42% less likely to inhabit damaged housing compared to migrants.

Table 9.

Binary Logistic Regression Results for Housing Damage.

3.2.3. Age Structure Analysis: The “Aging Trap”

While the global regression identifies hukou as the primary factor, a detailed breakdown of the age demographics for all 473 household members reveals a specific vulnerability within the local population. Table 10 present the raw age distribution data collected from the survey.

Table 10.

Age Distribution of Household Members: (a) Suzhou Local (N = 258). (b) Non-Local Migrant (N = 215).

3.2.4. Residential Motivation Analysis

The survey revealed fundamental differences between the local and migrant residents’ primary motivations for living in the historic block (Table 11).

Table 11.

Distribution of Primary Reasons for Residence by Hukou Status.

The data highlights a structural divergence: 65.2% of locals possess property rights (Inherited + Owned), indicating a long-term commitment. In contrast, 90.9% of migrants are driven by economic necessity (Rent + Workplace), indicating a transient relationship with the district.

3.2.5. Determinants of Unauthorized Modifications: Regression Analysis

To investigate how these differences in motivation and demographic status affected housing modification behavior, additional binary logistic regression models were run for different types of unauthorized modifications.

- Unauthorized Window Replacement: The model shows there a strong positive correlation with local status. The regression coefficient for local hukou is 0.996 (p < 0.01), with an Odds Ratio of 2.71. This indicates that local residents are nearly 3 times more likely to replace traditional windows with modern materials compared to migrants.

- 2.

- Unauthorized Outdoor Storage: Conversely, local status shows a negative correlation with outdoor storage (β = −0.615, p = 0.089), with an Odds Ratio of 0.54. While marginally significant, it suggests that possessing a local hukou reduces the likelihood of encroaching on public space by approximately half.

The above results quantitatively demonstrate the behavioral divergence between locals and migrants: locals are the primary drivers of structural alterations (windows), while migrants are the primary drivers of spatial encroachments (storage).

4. Discussion

4.1. The Magnitude of the Conservation Deficit: Material Decay as a Systemic Failure

The quantitative results presented in this study expose a profound “conservation deficit” within the Pingjiang Historic Block. The primary challenge facing the district is not merely potential vulnerability, but the actual widespread physical degradation of its residential fabric. While the region’s humid climate inherently accelerates the aging of timber and clay materials [47], the scale of this recorded deterioration points to a more immediate problem: the inefficacy of the current maintenance regime. The prevalence of damaged structural elements indicates that the mandatory “preventive conservation” measures are failing to keep pace with the rate of decay. Consequently, there is a significant gap between the district’s acclaimed heritage status and the precarious physical reality of its historic dwellings, where essential protective components (roofs and walls) are compromised.

4.2. Spatial Inequity and the “Hollowing Out” of Heritage

Beyond the material decay, the spatial distribution of the damage points to a deeper issue of inequitable resource allocation driven by commercial interests. The data shows a clear divergence, with investment being prioritized for marketable frontages, while the residential hinterlands suffer from neglect. This “selective conservation” creates a fragmented landscape where the physical integrity of a building depends largely on its visibility to tourists rather than on its historical value [48]. The case of Cang Road exemplifies the extreme consequence of this dynamic. While this street has 100% architectural retention, its residential occupancy has plummeted to only 44%. This paradox reveals a critical flaw in the current model, with the pursuit of visual “integrity” often coming at the expense of social continuity. The underlying problem here is the commodification of heritage space, which successfully preserves the physical shell (the façade) but erodes the living community inside, leading to a “hollowed-out” district that functions more as a stage set than a neighborhood [2].

4.3. The Conflict Between Rigid Authenticity and Living Needs

The pervasive replacement of traditional doors and windows (55%) exposes a fundamental incompatibility between top-down preservation standards and contemporary living standards. Our regression analysis offers critical insight into this phenomenon, revealing that this is not a random act of vandalism, but a patterned behavior led by local residents. The statistical model shows that local hukou holders are nearly three times more likely (Odds Ratio = 2.71) to replace windows than migrants. This finding strongly suggests that for permanent residents—who mostly own their homes (60.7%)—this modification is an “Adaptive Strategy” that they use to secure basic thermal comfort, security, and ease of maintenance, qualities that the original deteriorating timber components fail to provide [49,50,51]. Therefore, the current policy, which prioritizes a static definition of material authenticity over the functional adaptability required for modern life, effectively forces the district’s most loyal stewards to become “violators.” The high rate of modification in the heavily residential areas (e.g., Qiling Road) proves that when preservation policies ignore the “lived reality” of occupants, regulatory failure is inevitable.

4.4. Institutional Barriers as Root Causes of Decay

Finally, the survey identified social stratification and institutional exclusion as the primary structural drivers of physical decay. These dual mechanisms operate through two distinct channels, which our multivariate statistical analysis has rigorously validated.

First, the Binary Logistic Regression confirms that hukou status is the decisive predictor of housing integrity (β = −0.544, p < 0.01). Holding other factors constant, possessing a local hukou reduced the probability of living in a damaged house by 42%. This statistical evidence points to the hukou system as an institutional barrier that systematically decouples residency from stewardship [52,53]. Migrants, driven by the search for “affordable rent” (63.6%), are channeled into a “Low-Cost Tenure” trap. Their transient status and lack of property rights create a perverse incentive structure where neither the landlord nor the tenant invests in long-term conservation, resulting in significantly higher damage rates (53.5%) and spatial encroachments like outdoor storage.

Second, for the local population, the decay is driven by a different mechanism: the “Aging Trap.” While locals have the motivation (ownership) to maintain their homes, they often lack the physical capacity to do so. Our Independent Samples T-Test reveals a significant age gap, with local residents living in damaged properties having a mean age of 61.7 years, compared with 57.5 years for those in intact homes. This “capacity gap” indicates that heritage decay among locals is largely a symptom of physiological decline [54], with the manual labor required for timber-frame repairs and roof maintenance exceeding the capacities of these elderly residents.

Therefore, the visible material degradation represents merely the surface manifestation of a deeper institutional and demographic crisis. The “conservation deficit” is, at its root, a “social deficit”, with the burden falling disproportionately upon society’s most vulnerable segments—transient migrants lacking institutional support and elderly residents facing physiological limitations—while the necessary frameworks to rebalance this equation remain conspicuously absent [55,56].

4.5. Understanding the Social Roots of Physical Decay

Statistical analysis of the building conditions and residents’ characteristics shows that the material decay in Pingjiang is not random but systematically linked to social factors. Our regression analysis points to two main pathways through which social conditions translate into physical damage.

First, the connection between migrant households and roof damage reflects what can be called “tenure insecurity”. Roofs are the primary protective layer of a building, so they require regular investment and long-term care. However, migrants—constrained by their hukou status and often driven by the need for affordable rent—lack secure property rights. This reduces their incentive to maintain the property. So, in effect, damaged roofs in migrant-occupied homes represent a rational response to a temporary living situation where buildings are treated as short-term shelter rather than as heritage to be preserved.

Second, the link between elderly local residents and unauthorized window replacements highlights a process of “physiological adaptation”. Unlike migrants, local homeowners generally intend to stay long-term, but they face physical limitations associated with aging. The common replacement of traditional windows reflects a practical need to improve thermal comfort that historic building materials often fail to meet for older residents.

In summary, Pingjiang’s built environment acts as a mirror that reflects its social realities: damaged roofs signal the occurrence of institutional exclusion, while altered windows reveal areas shaped by an aging population. Together, these physical signs make visible the growing gap between rigid conservation rules and the day-to-day lives of the people who inhabit this historic district. Only by addressing these underlying social issues—rather than treating physical symptoms in isolation—can Pingjiang’s residential heritage be sustained as a living, inhabited cultural landscape [57].

5. Conclusions

5.1. The “Conservation Deficit”: A Paradox of High Status and Physical Decay

This study reveals a profound paradox within the Pingjiang Historic Block: despite its esteemed status as a UNESCO-recognized site and a “National Historic and Cultural Street”, the district suffers from a significant “Conservation Deficit”. Our quantitative survey provides evidence that behind the acclaimed heritage status of the site, there lies a silent crisis of material degradation. With 32% of traditional residences exhibiting roof damage and 22% showing wall deterioration, the physical fabric of the district is compromised. This deficit is not merely cosmetic; it represents a systemic failure of the current “static preservation” model, which has successfully preserved the urban morphology (the street network) but failed to arrest the widespread decay of the vernacular architectural substance that constitutes the district’s authentic core.

5.2. Structural Drivers of Decay: Institutional Exclusion and Functional Obsolescence

Contrary to the assumption that decay is solely the result of natural aging, this study identifies two structural dissonances driving this deficit, validated by our multivariate statistical analysis:

- Institutional Exclusion (The Migrant Dilemma): For the non-local population, heritage decay is a rational economic response to tenure insecurity. Our regression analysis confirms that hukou status is a decisive predictor of housing integrity (β = −0.544). Driven by the “affordable rent” motivation (63.6%), migrants are locked into a transactional, short-term relationship with the built environment. The lack of long-term property rights creates a “stewardship vacuum,” where neither the transient tenant nor the rent-seeking landlord has the incentive to invest in maintenance, leading to a pattern of “Neglect by Design.”

- Functional Obsolescence (The Local Dilemma): For the local population, the primary driver of alteration and decay is the incompatibility between rigid conservation standards and modern living needs. The finding that local residents are 2.7 times more likely to replace traditional windows demonstrates that the historic building stock is functionally obsolete in terms of thermal comfort and insulation. Locals are not destroying heritage out of ignorance, but out of a desperate need for “Modernization.” When strict preservation policies forbid necessary upgrades without offering viable alternatives, residents are forced to choose between “authenticity” and “habitability,” often resulting in unauthorized adaptations that compromise the historic character.

5.3. Re-Theorizing Authenticity: Towards “Adaptive Integrity”

The prevalence of “unauthorized modifications” (55% window replacement) should not be dismissed simply as vandalism. Instead, this study argues that these behaviors represent a grassroots form of “Adaptive Integrity”, i.e., an attempt by the residential community to reconcile the historic buildings with contemporary life. The conclusion drawn is that the rigid pursuit of “Visual Integrity” (freezing the material form) is paradoxically accelerating the loss of “Social Integrity” (driving out residents or forcing destructive adaptations). True sustainability for Pingjiang lies in shifting from a Form-Based Conservation approach to a Performance-Based one. This means accepting that for a historic district to remain inhabited, its physical fabric must evolve. The “integrity” of the heritage should be measured not just by the retention of original timber, but by the building’s continued ability to house its original community comfortably.

5.4. Implications: Implementing the “Adaptive Integrity” Framework

To reconcile the gap between conservation mandates and on-the-ground realities, this study proposes an “Adaptive Integrity” framework that shifts from a punitive, control-oriented regulatory model to an enablement-oriented strategy centered on supporting residents’ daily needs and practical circumstances.

- Addressing Tenure Insecurity (For Migrants): To resolve the mechanism of neglect, policy interventions should explore “Heritage Stewardship Leases.” These would be long-term rental contracts that decouple residency rights from hukou status, granting migrants quasi-ownership stability and access to renovation subsidies in exchange for their commitment to maintain critical building components (specifically roofs and load-bearing structures). This aims to transform transient users into invested custodians.

- Addressing Physiological Needs (For Locals): To resolve the conflict between comfort and authenticity, heritage authorities should issue “Adaptive Retrofit Guidelines.” Instead of simply penalizing window replacements, the framework proposes legalizing and standardizing technical solutions—such as integrating high-performance double-glazing within traditional timber frames. This approach reconciles the preservation of the historic streetscape with the contemporary need for thermal comfort, allowing the original community to age in place.

- Inclusive Governance: Recognizing that the “Conservation Deficit” is a social product, future governance must integrate the economic motivations of migrants and the functional needs of locals into the core of heritage management plans.

In sum, the physical survival of Pingjiang depends on resolving the structural conflicts between the static heritage regime and the dynamic reality of its inhabitants. Only by aligning institutional incentives with functional needs can the district evolve from a fragile museum piece into a resilient, living urban organism.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.C. and H.K.; methodology, W.C. and H.K.; investigation, Data Curation, W.C.; writing—original draft preparation, W.C.; writing—review and editing, all authors; supervision, H.K., T.N. and I.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

All data used in this study are presented in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We extend our sincere gratitude to the residents of Pingjiang Subdistrict in Suzhou, Jiangsu Province, China, who participated in the questionnaire survey conducted between August and September 2021. We also thank the members of the Environmental Design Laboratory at the School of Agriculture, Meiji University, for their valuable insights and constructive feedback during seminars. During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used Google Gemini solely for limited assistance with English grammar correction and language polishing. The authors have reviewed and edited all AI-assisted output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Liu, H.; Chen, W.; Sun, S.; Yu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Ye, C. Revisiting China’s urban transition from the perspective of urbanisation: A critical review and analysis. Sustainability 2024, 16, 4122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Heath, T. Conservation and revitalization of historic streets in China: Pingjiang Street, Suzhou. J. Urban Des. 2017, 22, 455–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y. Living heritage conservation: From commodity-oriented renewal to culture oriented and people-centred revival. Int. Plan. Hist. Soc. Proc. 2018, 18, 279–287. [Google Scholar]

- Harper, D.; Styles, M.A. Environmental conservation and sustainability: Rhetoric and reality. In Agricultural Intensification, Environmental Conservation, Conflict and Co-Existence at Lake Naivasha, Kenya; Kuiper, G., Kioko, E., Bollig, M., Eds.; Brill: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2024; Volume 34, pp. 40–65. [Google Scholar]

- Shan, M.; Chen, Y.F.; Zhai, Z.; Du, J. Investigating the critical issues in the conservation of heritage building: The case of China. J. Build. Eng. 2022, 51, 104319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, N.; Chan, E.H.W.; Yung, E.H.K. Alternative governance model for historical building conservation in China: From property rights perspective. Sustainability 2020, 13, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luxen, J.L. ‘The Principles for the Conservation of Heritage Sites in China’: A Critique. In Conservation of Ancient Sites on the Silk Road: Proceedings of the Second International Conference on the Conservation of Grotto Sites, Mogao Grottoes, Dunhuang, China, 28 June–3 July 2004; Getty Publications: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2010; p. 85. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Y. Authenticity and heritage conservation in China: Translation, interpretation, practices. In Authenticity in Architectural Heritage Conservation: Discourses, Opinions, Experiences in Europe, South and East Asia; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 187–200. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, R.; Gao, W.; Yang, F. Authenticity, Integrity, and Cultural–Ecological Adaptability in Heritage Conservation: A Practical Framework for Historic Urban Areas—A Case Study of Yicheng Ancient City, China. Buildings 2025, 15, 1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, D. Protecting Suzhou: Study of the Conservation of Cultural Heritage in the Cities Along China’s Grand Canal. Doctoral Dissertation, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Li, L.M.; Tao, W. Spatial structure evolution of system of recreation business district: A case of Suzhou City. Chin. Geogr. Sci. 2003, 13, 370–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degen, W.; Juan, T.; Momo, W.; Meifeng, Z. Spatial evolution and influence mechanism of tourism in historic quarters from the postmodern consumption perspective: A case study of Pingjiang road and Shantang Street, Suzhou, China. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2022, 27, 1071–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO Bangkok. 2005 UNESCO Asia-Pacific Heritage Awards for Cultural Heritage Conservation: Report of the Jury; UNESCO Bangkok Office: Bangkok, Thailand, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, J.; Zhou, T.; Han, Y.; Ikebe, K. Urban heritage conservation and modern urban development from the perspective of the historic urban landscape approach: A case study of Suzhou. Land 2022, 11, 1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, B.; Lee, W.; Wang, Q. Residents’ perceptions of tourism gentrification in traditional industrial areas using Q methodology. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzhou Municipal People’s Congress. Regulations of Suzhou on the Protection of Famous Historical and Cultural Cities [Local Regulations]. 2018. Available online: https://www.suzhou.gov.cn/szsrmzf/gbdfxfg/202207/1505c8c15d4a4c08b2c7f026567a4338.shtml (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Standing Committee of Suzhou People’s Congress. Regulations on the Protection of Ancient Buildings in Suzhou [Local Regulations]. 2022. Available online: https://www.jsrd.gov.cn/qwfb/d_sjfg/202210/t20221010_540489.shtml (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Yang, Z. Destructive reconstruction in China: Interpreting authenticity in the Shuidong reconstruction Project, Huizhou, Guangdong Province. Built Herit. 2021, 5, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Xiao, J.; Ma, B.; Fu, H.; Xu, L. Construction of China’s “Large Ruins” Monitoring System Based on the Comparative Analysis of World Cultural Heritage Monitoring-An Example of the European-style Palace of the Old Summer Palace. ISPRS Ann. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2015, 2, 171–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Niu, Y.; Lu, L.; Qian, J. Tourism spatial organization of historical streets–A postmodern perspective: The examples of Pingjiang Road and Shantang Street, Suzhou, China. Tour. Manag. 2015, 48, 370–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H. The publicness of an urban space for cultural consumption: The case of Pingjiang Road in Suzhou. Commun. Public 2017, 2, 84–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, B.X.; Chiou, S.C.; Li, W.Y. Study on courtyard residence and cultural sustainability: Reading Chinese traditional Siheyuan through Space Syntax. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D. Jiaanbieyuan New Courtyard-Garden Housing in Suzhou: Residents’ Experiences of the Redevelopment. J. Chin. Archit. Urban. 2019, 1, 526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzhou Municipal People’s Government. Measures for the Protection of Famous Historical and Cultural Cities and Towns in Suzhou (Government Decree No. 33) [Local Government Regulations]. 2003. Available online: https://sft.jiangsu.gov.cn/art/2009/9/9/art_71924_8102412.html (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Suzhou Municipal People’s Government. Notice on the Publication of Protection Scopes for Cultural Relics and Controlled Buildings (Su Fu [2020] No. 16) [Government Notice]. 2020. Available online: https://www.suzhou.gov.cn/szsrmzf/gbgfxwj/202304/b118ef088f524f048aa18a8b045369ab.shtml (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- State Council of the People’s Republic of China. Regulations on the Protection of Famous Historical and Cultural Cities, Towns and Villages [State Council Regulations]. 2008. Available online: http://www.gov.cn (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress. Law of the People’s Republic of China on the Protection of Cultural Relics [National Law]. 2017. Available online: http://www.npc.gov.cn (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Yang, S.; Gui, L. The Landscaping Art and Cultural Interpretation of Walls in Traditional Suzhou Buildings. In The 6th International Conference on Arts, Design and Contemporary Education (ICADCE 2020); Atlantis Press: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2021; pp. 522–526. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Q.; Liao, Z.; Wu, Y.; Mulugeta Degefu, D.; Zhang, Y. Cultural sustainability and vitality of Chinese vernacular architecture: A pedigree for the spatial art of traditional villages in Jiangnan region. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Tian, H. The regionality of vernacular residences on the TianJing scale in China’s traditional JiangNan region. J. Asian Archit. Build. Eng. 2023, 22, 2745–2767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D. Classical Chinese gardens: Landscapes for self-cultivation. J. Contemp. Urban Aff. 2018, 2, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J. Transcending the limitations of physical form: A case study of the Cang Lang Pavilion in Suzhou, China. J. Archit. 2013, 18, 297–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazumdar, S.; Mazumdar, S. Intergroup social relations and architecture: Vernacular architecture and issues of status, power, and conflict. Environ. Behav. 1997, 29, 374–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, P.; Hu, S.; Xu, R. Formal Feature Identification of Vernacular Architecture Based on Deep Learning—A Case Study of Jiangsu Province, China. Sustainability 2025, 17, 1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knapp, R.G. China’s vernacular architectural heritage and historic preservation. Built Herit. 2024, 8, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, F.; Zhou, S. Dwelling is a key idea in traditional residential architecture’s sustainability: A case study at yangwan village in suzhou, China. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Council on Monuments and Sites. International charter for the conservation and restoration of monuments and sites (The Venice charter). In Proceedings of the IInd International Congress of Architects and Technicians of Historic Monuments, Venice, Italy, 25–31 May 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Arfa, F.H.; Zijlstra, H.; Lubelli, B.; Quist, W. Adaptive reuse of heritage buildings: From a literature review to a model of practice. Hist. Environ. Policy Pract. 2022, 13, 148–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vardopoulos, I.; Giannopoulos, K.; Papaefthymiou, E.; Temponera, E.; Chatzithanasis, G.; Goussia-Rizou, M.; Karymbalis, E.; Michalakelis, C.; Tsartas, P.; Sdrali, D. Urban buildings sustainable adaptive reuse into tourism accommodation establishments: A SOAR analysis. Discov. Sustain. 2023, 4, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boussaa, D.; Madandola, M. Cultural heritage tourism and urban regeneration: The case of Fez Medina in Morocco. Front. Archit. Res. 2024, 13, 1228–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cocola-Gant, A.; Gago, A. Airbnb, buy-to-let investment and tourism-driven displacement: A case study in Lisbon. Environ. Plan. A Econ. Space 2021, 53, 1671–1688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cocola-Gant, A. Place-based displacement: Touristification and neighborhood change. Geoforum 2023, 138, 103665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, H.; Takizawa, A. Population decline through tourism gentrification caused by accommodation in Kyoto City. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.; Chen, Y.; Zheng, L. The Non-Destructive Testing of Architectural Heritage Surfaces via Machine Learning: A Case Study of Flat Tiles in the Jiangnan Region. Coatings 2025, 15, 761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Chen, Y.; Zheng, L.; Chen, J.; Huang, Y.; Huang, Y.; Wang, N.; Hu, Y. Investigating and Identifying the Surface Damage of Traditional Ancient Town Residence Roofs in Western Zhejiang Based on YOLOv8 Technology. Coatings 2025, 15, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, H.; Zhang, J.; Zhuo, L.; Xiao, Q.; Chen, Z.; Tian, H. Research on intelligent monitoring technology for roof damage of traditional Chinese residential buildings based on improved YOLOv8: Taking ancient villages in southern Fujian as an example. Herit. Sci. 2024, 12, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.C.; Xie, H.R.; Kong, Z.Y.; Yuan, Q.L.; Zhang, R.H.; Hokoi, S.; Li, Y.H. Assessment of Deterioration Risk of the Wooden Columns of Historical Buildings in Southern China Based on HAM Transfer Model. In Journal of Physics: Conference Series; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2023; Volume 2654, p. 012008. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Y.; González Martínez, P. Heritage, values and gentrification: The redevelopment of historic areas in China. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2022, 28, 476–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Wang, H.; Hu, Z.; Zhou, Q.; Zhao, L. Heritage Regeneration Models for Traditional Courtyard Houses in a Northern Chinese City (Jinan) in the Context of Urban Renewal. Sustainability 2024, 16, 8089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, J.; Zhang, X.; Yang, Y. Thermodynamic renovations in traditional Huizhou folk dwellings: A case study. Int. Inf. Eng. Technol. Assoc 2023, 41, 937–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ripp, M.; Hauer, S.; Cavdar, M. Heritage-based urban development: The example of Regensburg. In Reshaping Urban Conservation: The Historic Urban Landscape Approach in Action; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2019; pp. 435–457. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Y.; Ren, J. Moving toward an inclusive housing policy?: Migrants’ access to subsidized housing in urban China. Hous. Policy Debate 2022, 32, 579–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logan, J.R.; Fang, Y.; Zhang, Z. Access to housing in urban China. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2009, 33, 914–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, M.; Chai, N. Resilience Renewal Design Strategy for Aging Communities in Traditional Historical and Cultural Districts: Reflections on the Practice of the Sizhou’an Community in China. Buildings 2025, 15, 965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, K.W.; Buckingham, W. Is China abolishing the hukou system? China Q. 2008, 195, 582–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Bureau of Statistics of China Suzhou Municipal Bureau of Statistics. Seventh National Population Census Data Compendium-Suzhou Municipality. [Official Statistical Report]. 2021. Available online: http://www.suzhou.gov.cn/szsrmzf/tjgb/2021 (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Kim, J.S.; Wang, Y.W. Tourism identity in social media: The case of Suzhu, a Chinese historic city. Trans. Assoc. Eur. Sch. Plan. 2018, 2, 63–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.