Abstract

In the context of a study on selected fragments of ancient architecture belonging to a collection of the archaeological museum “Luigi Bernabò Brea” in Lipari (Aeolian Islands, Messina, Italy), we analysed, using the non-destructive X-Ray Fluorescence (XRF) method, dozens of artefacts dating back to the sixth century BCE. The aim was to identify the origin of the raw materials used by craftsmen in the production of ceramic artefacts. The quantitative analyses, based on the composition and trace elements, suggest that the composition material used is consistent with local natural resources, given the presence of kaolinite–clay deposits in the northern part of Lipari. By comparing the ancient fragments with local raw kaolin powders still available today, this study aims to confirm the use of these materials in past ceramic production and decoration. These results support the hypothesis that the investigated fragments were locally manufactured, providing deeper insights into the production techniques of the time and the raw materials of the region.

1. Introduction

In an effort to identify the historical context of some pre-Roman artifacts, we analysed a collection of artifacts belonging to the Archaeological Museum “Luigi Bernabò Brea” in Lipari (Messina, Italy) using pXRF (portable X-ray fluorescence analysis), under the supervision of the Director of the Aeolian Museum. Although previous research suggested that these finds are likely imports of a Greek origin [1,2,3,4], this has recently been debated [5]. The existing literature suggests that the major elements SiO2, CaO, TiO2, and Al2O3 do not support any specific chemical features in Southern Italy (Milazzo and Lipari areas). In contrast, reliable distinctions can be made for the minor elements, indicating rubidium (Rb) and strontium (Sr) in findings from Lipari. Many artifacts found in Milazzo and Lipari have been recognised as Corinthian imports by experts [5] based on the colour of the clay of the ceramic, due to the high concentration of Ni and Cr. The literature discriminates a certain local manufacture by the nickel (Ni) and chromium (Cr) contents, due to the different geographical composition of the two territories. Experts such as Amyx [6] asserted that the distinction between Greek and foreign imitations can be made via the colour and texture of the clay, even if, for some pieces, this is quite impossible.

The significance of the topic lies in the pigment analysis and its potential to reveal information about the provenance of the raw materials and the technological choices of ancient artisans. For example, the variable content of CaO, characteristic of clays from the Messina Strait area, can provide clues about the local area with respect to the imported production, shedding light on regional manufacturing practices and material networks [7]. Since Mediterranean civilisations emerged, a variety of natural dyes and pigments have been used and preserved over the centuries [7,8,9]. These dyes, obtained from hydroxy derivatives and metal–ion complexes, reflect the geochemical characteristics of their source in that area and, therefore, can provide information about the local production, raw material selection, and trade interactions. In this study, the artefacts were compared with the raw material deposits located in northern Lipari, including natural earth pigments such as ochres, obtained as mixtures of ferric oxides with variable clay and sand content, to explore these technological and provenance-related aspects.

The collections cannot be removed and/or sampled; so, measurements were carried out in situ in the museum of Lipari using compact portable instrumentation. X-ray spectroscopic techniques, particularly pXRF, are the most widely employed for non-destructive multi-elemental analysis and require minimal sample preparation [10,11,12].

The pXRF analyses are non-invasive and can be used for both qualitative identifications of the elements and to quickly recognise the element composition of the samples, even at low concentrations. pXRF analyses can typically be performed either in air or under vacuum conditions, although our study employed in situ measurements in air using a portable instrument.

The pXRF analyses are based on the ionisation of the sample and its subsequent de-excitation, which leads to the emission of characteristic X-rays. The measurement of the X-ray energies allows the identification of the elements, based on Moseley’s law, which relates the frequency of the characteristic X-rays to the atomic number of the element, providing a direct link between the emitted X-ray energy and the element identity [13].

pXRF spectrometers typically use radioactive ion sources or X-ray tubes and high-energy resolution detectors such as Si-PIN photodiodes or silicon detectors SDD cooled by the Peltier effect. Such systems therefore do not need high-power electrical power supply, or liquid nitrogen, or vacuum systems to be functional. The development of digital signal processors (DSP) has also contributed to the miniaturisation of pXRF spectrometers, control electronics with a high signal/noise ratio, the fast acquisition system of signals and PC via USB, and good control of the characteristics of I-V of X-ray tubes.

pXRF can be used in different fields, from medicine to microelectronics and cultural heritage environments. This paper focuses on the analysis of dozens of archaeological samples from the island of Lipari, in the Mediterranean Sea. This compact instrument was used to analyse in situ, at the Museum of Lipari, some important fragments of architectural ceramic structures of the sixth century BCE. It can also be used during archaeological excavations and at archaeological sites or in laboratories, for both large and small samples. In the latter case, it is preferable to use the analysis in a vacuum in a laboratory, to reduce the background signal and improve the sensitivity of the analytical method, as it is able to analyse fragments of the order of 1 g or less.

2. Materials and Methods

The elemental composition analysis of the artefacts was performed employing a portable Amptek XRF system. This technique operates without direct contact, measuring a short distance from the specimen. The experimental apparatus consists of a miniaturised X-ray tube (Mini-x, Amptek Inc., Bedford, MA, USA) with a tuneable voltage from 5 kV to 30 kV, with a current varying in the range from 10 μA to 100 μA, a Si-PIN detector cooled by Peltier effect, an analogical–digital converter (ADC) and a multi-channel (MCA) analyser (XR-100CR X-ray detector, Bedford, MA, USA). The X-ray tube is equipped with a silver (Ag) anode, a transmission filter in Au and Al, and an inlet thin beryllium window. It is designed for continuous operation in industrial environments. The X-ray beam irradiates an area of approximately 1 mm2 on the ceramic surface. Data are collected from this irradiated spot, reflecting the elemental composition of the near-surface layer of the sample. Under the given measurement conditions (tube voltage, current, and detector setup), the effective analytical depth typically ranges between 20 and 100 μm, depending on the ceramic matrix and the elements analysed. A flashing red LED and a beep alert occur when X-rays are emitted from the tube [14]. The pXRF analysis could be performed in air or under vacuum. In the first case, the minimum detectable energy is generally about 1.7 keV, while in the second case, it is possible to detect X-rays up to about 1.2 keV, corresponding to the detection of all the heavier elements from silicon or magnesium, respectively. The identification of the elements’ peaks was in real time collected on the laptop connected to the instrumentation using the software S1PXRF 3.8.0.30. The quantitative records were obtained by means of PyMCA software 5.7.4.

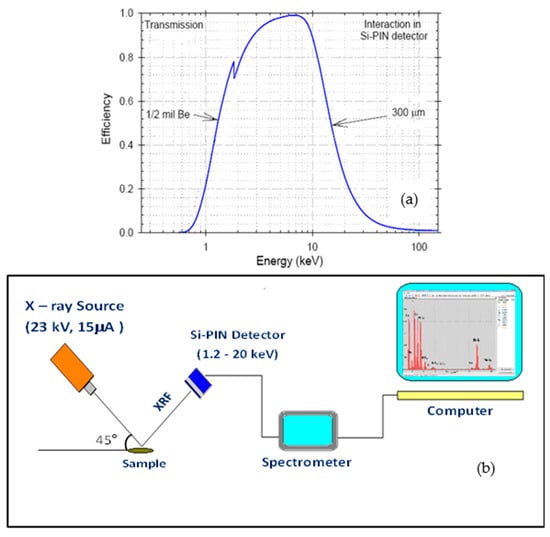

The detection efficiency at these minimum energies is low, of the order of 1% or less. The efficiency is maintained around 100% to about 6 keV of energy and is kept high until approximately 25–30 keV, after which it returns again to 1% or less, as reported in the detection efficiency curve of Figure 1a.

Figure 1.

(a) Detection efficiency of the used Si-PIN detector, (b) scheme of the portable XRF system.

For analysis, the voltage was set at 23 kV with a current of 15 μA. A 127 μm thick beryllium window allows for filtering low-energy X-rays below 2 keV. A Si detector, cooled by the Peltier effect, was employed to detect photons with energies between 1.2 keV and 20 keV, achieving an energy resolution of 140 eV (full width at half maximum, FWHM) at 5.9 keV. The typical acquisition time for each spectrum was 30 min.

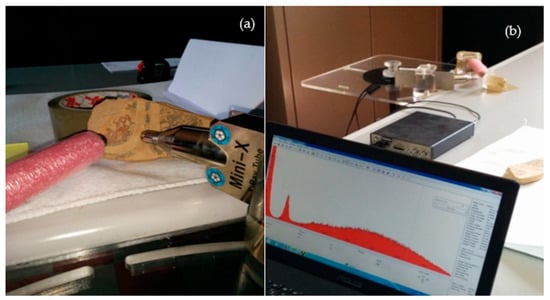

The X-ray beam typically strikes the analysed surface with an angle of incidence of 45° while the solid-state detector forms an angle of 90° with the direction of the radiation beam. Figure 1b shows a sketch of the electronic detection system used in pXRF. Figure 2a shows the pXRF system mounted on a suitable adjustable support for adequate height and ready for measurement in situ in a specimen placed on the table, while Figure 2b shows the photo of the acquisition system data and their processing by a PC notebook. The detector, X-ray tube, and Si-PIN were assembled at 90°.

Figure 2.

(a) Set-up of the portable XRF (pXRF) instrumentation system and (b) acquisition process.

The optimal distance between the tube and the sample X (and, symmetrically, between the sample and the detector) was 8 mm, subtending a solid angle of detection of about ΔΩ = 20 msr. A calibration of the energy scale was performed before the measurement using thick metal foils of known composition, including Al, Si, Ti, Fe, Ni, Cu, Zn, Mo, Pd, Ag, Sn, Ta, W, Au, and Pb.

These standards, while not ceramic, were used solely for instrument energy calibration and peak position verification and not for quantitative calibration, as the focus was on qualitative and semi-quantitative analysis.

In addition to metal foils for energy calibration, ceramic reference materials with known composition were used to better approximate the matrix of the archaeological samples for semi-quantitative comparison rather than fully quantitative.

The standard samples were irradiated under the same experimental conditions as the ceramic artefacts investigated [15].

The open-source code QTIPLOT (operating on Linux) [16] for data analysis and visualisation was used to extract the spectra and to process the data collected. Sample analysis was preceded by an accurate cleaning of the surface with distilled water.

pXRF analysis allows investigation of the elemental composition from the surface to a depth that varies depending on the element, the sample matrix, and the excitation conditions. Compared to techniques such as SEM, which typically probe only the top 1 µm, pXRF can reach larger depths. Under our measurement conditions (Ag anode at 30 kV) and given the ceramic matrix, the effective analytical depth can extend up to approximately 100 µm for heavier elements [17].

The pXRF spectra were treated by removing the background signal and then analysing qualitatively and semi-quantitatively.

As a surface-sensitive technique, pXRF provides compositional information from the near-surface layer of the sample, suitable for relative comparisons of elemental concentrations. Peaks originating from pileup, as well as those fleeing the Si detector and other artefacts of the spectra, were discarded.

Self-absorption effects in the matrix of characteristic X-rays, as well as the dependence on the efficiency of detection by the energy of X-rays, have been considered.

The quantitative analysis was obtained by comparing the yield in calibrated standards with that in the analysed samples, using the same experimental conditions and the following calculation:

where Conc (X)unkn represents the concentration of the X element to be evaluated, Y (Xpeak)unkn is the X-ray yield of the element to be measured, Y (Xpeak)Std is the yield of the standard sample, and (Bkgd) is the X-ray yield of the background signal at the X-element energy position.

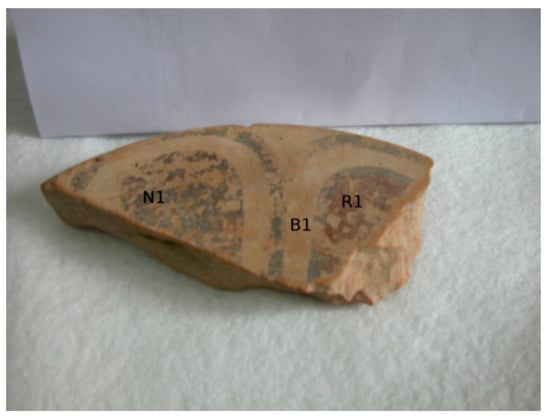

The analysis was focused on the study of the elemental composition of some architectural fragments subjected to a firing process dating from the sixth century BC. The analysed fragments are illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Picture of the selected architectural remains among those analysed: Antefix fragments # 1 (a), # 2 (b), # 3 (c), and # 4 (d).

The first fragment (# 1, top left) represents a fragment of an antefix, an architectural element inserted at the end of a gutter to collect rainwater. This fragment is about one eighth of the total area of 50 cm2, where it is possible to catch a glimpse of two lobes partially drawn.

The other three polychrome fragments (# 2, # 3, #4) are consistent with early Corinthian architectural decoration in the central Mediterranean [18], and their pigment composition and stylistic features may align with regional practices in Lipari and nearby areas. All these fragments are characterised by a rich polychrome, except for fragment # 4. The colours are more present, in addition to the typical brown clay, white, black, and red pigments. The current study aims to compare the elemental composition of artifact # 1 with the composition of the fragments # 2, # 3, and # 4, to provide a proper historical and geographic context for them. Moreover, in our analysis, we considered the idea of being able to determine the origin of the raw materials employed in the construction of the artefacts.

A parallel study was conducted on materials likely used by artisans of that historical period. A series of kaolin samples was taken from a cave located in the northwest of the Lipari Island (quarries of Kaolin, area Quattropani, Lipari). In this study, the kaolin samples were not fired, because our primary aim was to characterise the raw material, as it found in the cave, to assess its suitability as a ceramic raw material.

By analysing the native kaolin, we aimed to establish a geochemical baseline that could then be compared to the ceramic findings. However, due to the variability in ancient firing conditions (e.g., temperature, atmosphere, duration), simulating an appropriate firing environment would require a number of assumptions that could introduce mistakes.

For many years, this site has been well-known for the extraction of kaolin, a clay mineral that could have been used by local artisans for ceramic production. The sampling aimed to investigate the mineralogical and compositional characteristics of the raw material potentially available to craftsmen of all historical periods.

Such samples underwent a process of dehydration and compression under high pressure, in order to prepare them in the form of pads (with an area of 1 cm2 and a thickness of 1 mm) for elementary analysis in vacuum through the XRF and SEM coupled with X-ray diffraction (XRD).

The analysis was performed at the Department of Physics of the University of Messina. XRD analysis was performed by using a SIEMENS D5000 diffractometer (Siemens, Munich, Germany) with Cu Kα radiation (8 keV), filtered with Ni, and operating at 40 kV voltage and 30 mA current, with a slit input of 1 mm. A Seemann-Bohling 2 theta angle configuration was used [19].

3. Results

3.1. Analysis of the Architectural Elements

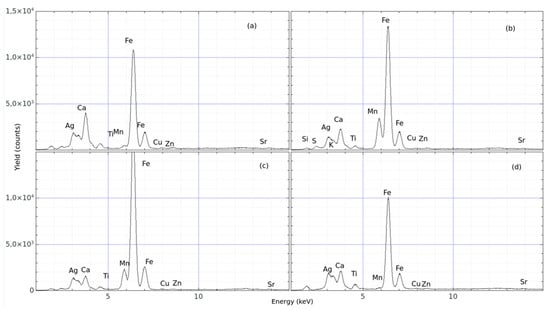

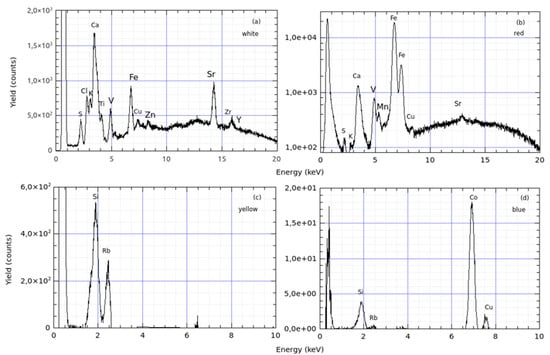

Sample # 1: Figure 4 represents an image of the ceramic fragment of the antefix analysed at ten different points on the front surface (R1 = surface area of red colour, N1 = the area of black colour, and B1 = area of white colour). A further ten points were analysed on the back surface of the specimen, showing only the clean surface of the clay. For each of these points, a representative pXRF spectrum of the elemental compositions is shown in Figure 5. The white pigment (see Figure 5a) indicates the predominance of Fe and Ca contents. The black pigment (see Figure 5b) reports the main contents of Fe and Mn, as well as the red pigment (see Figure 5c), exhibiting a dominant Fe concentration. The clay on the back side of the antefix shows Fe, Ca, Ti, and other trace elements.

Figure 4.

Picture showing the spots analysed by the pXRF technique on the sample # 1 (antefix).

Figure 5.

pXRF spectra acquired from different spots selected on the sample # 1 (antefix). The spectra show the yields of the compositional elements as a function of the energy of X-rays generated by: (a–d).

A table of relative yields was calculated as an average value with a standard deviation lower than 18.0%, as reported in Table 1. The white area (B1) contains slightly more Ca than Fe.

Table 1.

Relative yield for sample # 1.

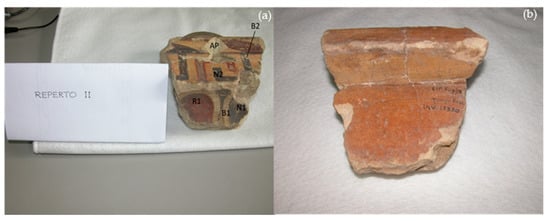

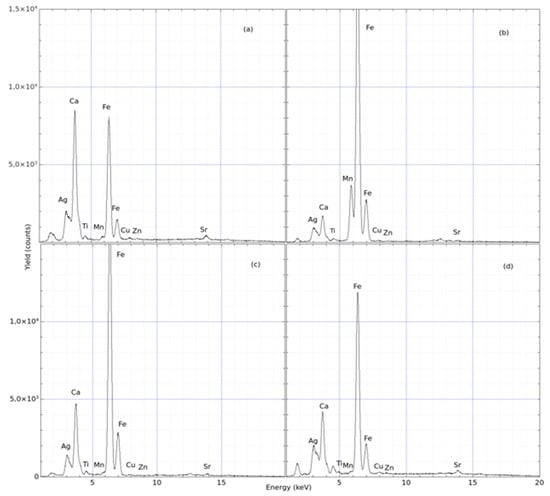

Sample # 2: The second sample relates to a fragment of an architectural polychrome element (Figure 6), which shows the front and rear. Ten samples were collected on the front and one in the back. The more representative spectra of these investigations are reported in Figure 7. In this case, the evaluation based on the comparison between the spectra is reported in Table 2, indicating the Fe/Ca yield ratio. The white area still contains slightly more Ca than Fe. The architectural fragments show a Ca concentration comparable to that in the antefix, while the Fe content is still dominant in the red pigment (see Figure 7c).

Figure 6.

(a) Picture showing the spots analysed by the pXRF technique on the top of the sample # 2 (architectural fragment) and (b) its back side.

Figure 7.

pXRF spectra acquired from different spots selected on the sample # 2 (architectural fragment). The spectra show the yields of the compositional elements as a function of the energy of X-rays generated by the (a–d).

Table 2.

Relative yield for sample # 2.

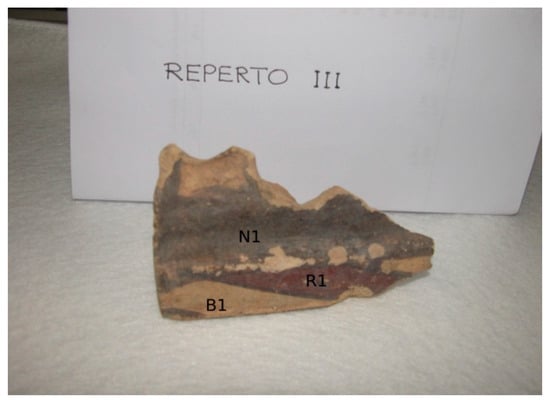

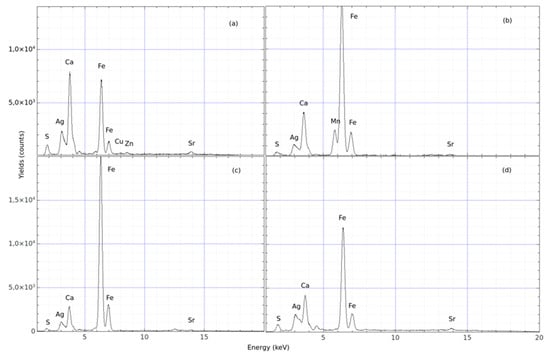

Sample # 3: A photo of the finding and the spectra of the analysis concerning finding #3 are shown in Figure 8 and Figure 9, respectively. The more representative spectra of these investigations are reported in Figure 8. In this case, the evaluation based on the comparison of the spectra is reported in Table 3, indicating the Fe/Ca yield ratio. Again, the white area contains slightly more Ca than Fe, with enough Ca to produce a visible white colour.

Figure 8.

Picture showing the spots analysed by the pXRF technique in sample # 3 (architectural fragment).

Figure 9.

pXRF spectra acquired from different spots on sample # 3 (architectural fragment). The spectra show the yields of the compositional elements as a function of the energy of X-rays generated by the (a–d).

Table 3.

Relative yield for sample # 3.

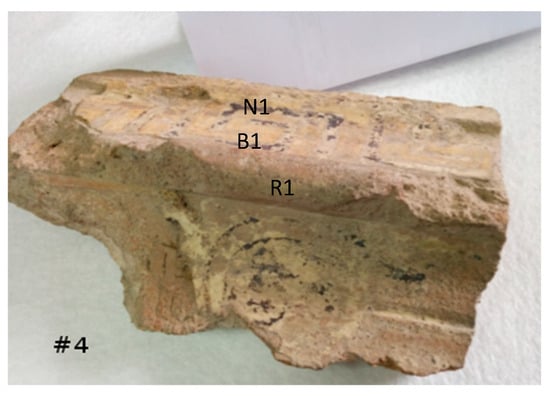

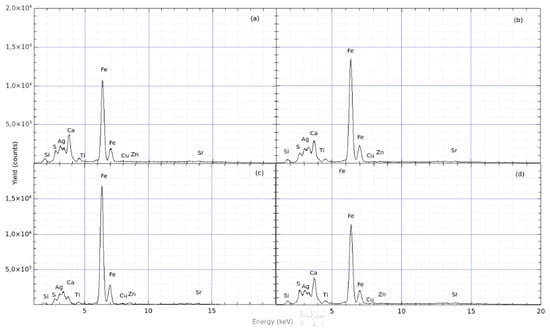

Sample # 4: This finding was also analysed by means of the pXRF technique, in different areas both of clay and pigments, as shown in Figure 10. In this case, the evaluation based on the comparison of the spectra is reported in Table 4, indicating the Fe/Ca yield ratio. Again, the white area contains slightly more Ca than Fe, with enough Ca to produce a visible white colour.

Figure 10.

Picture showing the spots analysed by the XRF technique in sample # 4 (architectural fragment).

Table 4.

Relative yield for sample # 4.

The reported Fe/Ca ratios (see Figure 11) are semi-quantitative estimations, which are sufficient to evaluate the relative compositional differences between the pigment areas and the clay matrix, as well as between different samples. Limitations of this approach include potential matrix effects, surface roughness, and pigment thickness variations, which may introduce minor biases in absolute elemental concentrations. However, despite these limitations, the observed trends and statistically significant differences reported here are well above the level of analytical uncertainty.

Figure 11.

XRF spectra acquired from different spots on sample # 4 (architectural fragment). The spectra show the yields of the compositional elements as a function of the energy of X-rays generated by the (a–d).

3.2. Clay Analysis

The comparison between the acquired spectra allows us to infer that the compositions of the #4 clay sample analysed are very similar to each other. The matrix of the crockery is based on the content of the clay, mainly composed of silicates, aluminium, and water in different percentages.

The main part of the clay can be defined as hydrated silicates of aluminium and magnesium, whose chemical formula is Al2·2SiO2·2H2O. However, natural clays exhibit numerous compositional variations, especially in the concentrations of elements such as Mg, Fe, Al, and O. These differences depend on several geological and environmental factors, including the nature of the rock, the presence of impurities, and the conditions under which the clay minerals formed.

For instance, a higher Fe content may result from iron-rich source rocks or depositional environments, while variations in the Mg and Al concentrations can be attributed to differences in mineral phases such as montmorillonite, kaolinite, or illite. According to the literature data [20], the typical weight composition includes approximately 47% SiO2, 38% Al2O3, about 3% Fe2O3, and smaller amounts (1% or less) of TiO2, CaO, MgO, K2O, and Na2O, as well as carbonate compounds like CaCO3.

These data agree with the experimental spectra acquired, related to light elements such as O, C, and Mg. These elements are not so marked, due to the issuance of their characteristic X-rays, which are too small to be detected in air. As elements in low concentrations, S, K, Ti, Mn, Cu, Zn, and Sr are always detected.

Lines attributable to Ag are revealed, but they arise as the effect of radiation coming from the anode of Ag of the X-ray tube and not from the analysed specimen. Table 5 summarises the experimental results of the Fe/Ca and Fe/Ti ratios in the four selected fragments, directly evaluated from the spectra acquired without further quantitative corrections. The table also reports the corresponding mean values and standard deviations (σ) of the measurements.

Table 5.

Summary of the average ratios between the yields of the significant peaks for the four analysed architectural remains.

The measurement error percentages ( for Fe/Ca in the red, black, white, and backside areas for the considered ratios are 0.39%, 9.02%, 1.8%, and 0.23%, respectively. The measurement error percentages ( for Fe/Ti in the red, black, white, and backside areas for the considered ratios are 18.0%, 9.4%, 8.3%, and 15.9%, respectively. Within the respective standard deviations (σ), we can assume that the red and white colours are very well defined. However, the four crockery samples exhibit similar elemental compositions.

The table indicates that the red pigment is rich in Fe, the white pigment is rich in Ca, the black pigment has a Fe content about five times higher than Ca, and the back side of the clay has a Fe content about three times higher than Ca. The errors in the Fe content and Ca content are very low; additionally, the Fe/Ca yield ratio is characterised by a low deviation in the clay, whereas more significant relative errors are found in the Fe/Ca ratio in the black pigment. The Ti oligoelement was characterised in terms of the Fe/Ti yield ratio, which is affected by a significant deviation in all pigments and in the clay composition.

To evaluate the compositional consistency of each pigment type across the four analysed samples, we performed one-way ANOVA [21] on the Fe/Ca ratios for each colour group separately (red, black, white, and back) using OriginLab software 8 [22].

For the red pigment, the ANOVA yielded a highly significant difference among samples (F = 169.6, p = 2.45 × 10−12). Tukey’s HSD post hoc test indicated that most sample pairs were significantly different (significance indicator function (SIF) = 1), with a few exceptions (e.g., # 4 vs. # 2, SIF = 0), reflecting minor local similarities.

For the black pigment, F = 7.41, p ≈ 0, with most pairwise comparisons significant (SIF = 1), although a few pairs showed slightly higher probabilities (0.008, 2.07 × 10−12), indicating moderate variation among black pigment spots.

For the white pigment, F = 173.8, p = 2.03 × 10−12; post hoc tests showed significant differences in nearly all pairwise comparisons, except between # 3 and # 1 (p = 0.751), consistent with slight local compositional similarity.

For the back (clay matrix), F = 10.66, p = 4.26 × 10−4, with most SIF = 1, but some pairs (# 3 vs. # 2 and # 4 vs. # 1) showed no significant difference (p = 1), indicating that the clay matrix is more homogeneous than the pigments but still exhibits some local variation.

These results confirm that each pigment type is chemically distinguishable betweensamples, while the clay matrix is relatively more uniform, supporting the interpretation that artisans used different raw materials for pigments, and the variations reflect actual compositional heterogeneity rather than instrumental error.

To evaluate whether the pigments were compositionally distinct from the clay matrix, Welch’s two-sample t-tests [23] were performed comparing the Fe/Ca ratios of red, black, and white pigment areas with the corresponding back areas (clay matrix) across all samples.

All pigments were found to be significantly different from the matrix (red: t = 827.5, p = 1.13 × 10−46; black: t = 20.61, p = 1.82 × 10−14; white: t = −523.14, p = 3.03 × 10−47).

These results confirm that each pigment was prepared from raw materials distinct from the clay matrix. Possible sources of analytical variability include the surface roughness, pigment layer thickness, minor instrument drift, and local heterogeneity. Despite these factors, the observed differences are far above the level of analytical noise, supporting the results.

3.3. Pigment Analysis

Analysis of the main pigments observed on the pottery was performed. From the spectra acquired, it was found that, in all the findings, the white colour was associated with a high concentration of Ca, the red with a high concentration of Fe, and the black with a high concentration of Fe and Mn. This result confirms the literature data, according to which the colourisation of the white pigments could take place employing calcium CaCO3, while the red colour was generated by the employment of Fe2O3 and Fe3O4 and the black colour from MnO [24]. The concentrations of Ca, Fe, and Mn in the three pigments increase on average by about 100% for Ca in the white pigment, 100% for Fe in the red pigment, and 900% for Mn in the black pigment. These results, found in the whole set of analysed samples, suggest that the origin of the coloured pigments is the same.

3.4. Analysis of Lipari Kaolin

The main constituent of the clay is kaolin, an elastic material, and the debris consists primarily of kaolinite. Its composition is mainly based on SiO2, Al2O3, and water, in a concentration by weight of about 46%, 39% and 14%, respectively. Its basic stoichiometry, with some variations on the order of 15%, is thus the type Al2O3 • 2SiO2 • 2H2O. It has special crystallographic and optical properties, with different indices of refraction along different crystallographic axes of the lattice. This mineral has an earthy look and is produced by the action of rainwater on feldspar. Usually, its colour is white or greyish white, although it sometimes assumes orange or red colours due to the presence of iron oxides. For its colour, and by virtue of its low cost due to the large amount on the island of Lipari, its white powder is widely used to colour different compounds, which can obtain all the possible colours of the visible spectrum. Sulphur compounds, copper, and chromium make, for example, yellow, green, and blue. This powder thus lends itself to be employed as a natural pigment of crockery, which can be fixed on the manufactured article thanks to thermal annealing processes.

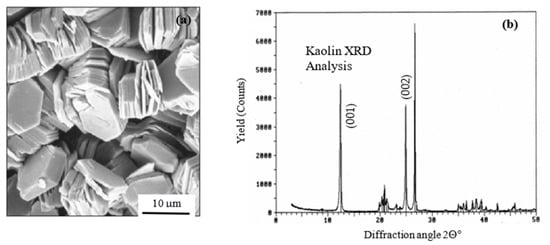

pXRF analyses were performed on Lipari kaolin, taken from local quarries, both as white and in different natural colours: yellow, blue, red, and black. SEM investigations showed the presence of both amorphous and crystalline particles, with lamellar structures typical of the mineral and spectra of the X-ray diffraction of the crystal of the typical kaolinite, as shown in Figure 12.

Figure 12.

(a) Typical lamellar structures by SEM image and (b) X-ray diffraction pattern (right) of kaolin.

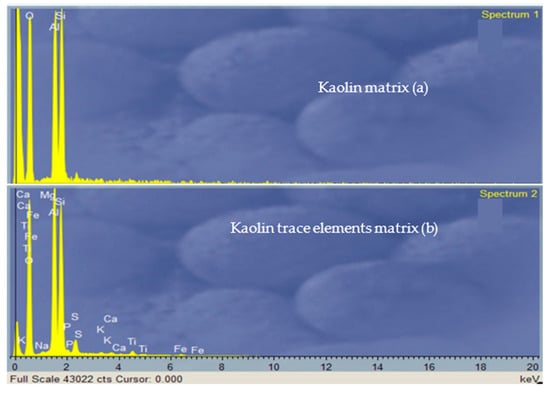

Two typical spectra EDX performed in high vacuum employing the microprobe using a 20 keV electron microscope of the SEM are shown in Figure 13.

Figure 13.

EDX spectra from 20 keV electrons reporting the main elements in the matrix (Spectrum 1 (a)) and the trace elements (Spectrum 2 (b)) of the Lipari kaolin.

The first spectrum (Figure 13a) relates to the elements of the composition of kaolin: O, Al, and Si; the second spectrum (Figure 13b) is related to the trace elements in kaolin: Ca, Fe, Al, Si, Mg, K, Na, P, S, Ti, and Fe. The information relates only to the surfaces of the dust grains analysed, as the depth of analysis extended only to the first micron surface. A more complete characterisation of the materials is planned to integrate XRD in future work.

The pXRF analysis by X-ray tube is deep, reaching more than 100 microns deep for heavier elements and dense matrices, thus allowing a better recognition of the elements even in traces of the sample. Figure 14 shows a comparison of the analysis of kaolin in white (a), red (b), yellow (c), and blue (d) powders.

Figure 14.

Comparison of spectra pXRF in the kaolin (a–d).

In Figure 14a–c, the presence of rubidium (Rb) and strontium (Sr) was revealed in findings in areas in Southern Italy [5]. In Figure 14d, the coexistence of cobalt (Co) and silica (Si) suggests their use in the production of the blue pigment, while copper (Cu) typically acts as a chromatic modulator, influencing the final shades of the blue colour and providing a printing feature of the used blue pigment.

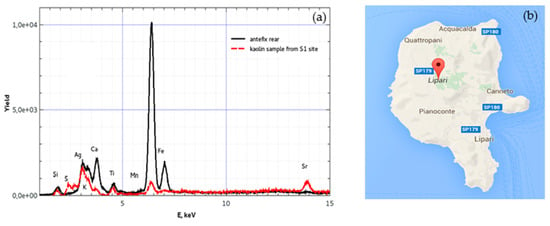

A comparison between the average composition of the fragments, subjected to a firing process, and a sample of pressed powder of kaolin not subjected to heat treatment, both analysed by the pXRF technique, is reported in Figure 15, where a map of Lipari reports the site S1 where the kaolin samples were extracted.

Figure 15.

(a) XRF spectra comparison of the composition of the finding #1 (antefix) and (b) site of the kaolin extraction in the Lipari Isle (S1).

This comparison shows that the relative composition of the main elements is similar; for example, for kaolin, the experimental average ratio Fe/Ca is 0.56 in white kaolin (see Figure 15a) and about 9.27 in red kaolin (see Figure 15b). However, large differences arise between the content of S, Ca, and Sr, which, in kaolin, are much higher than in clay. These differences can be justified by the thermal treatments experienced by the clay during cooking. The melting temperatures of the sulphur, calcium, and strontium are respectively 119 °C, 768 °C, and 838 °C. The processes of baking clay in the oven are generally carried out, as in the past, reaching temperatures of about 900–1000 °C and maintaining the piece at this temperature for times of about 10 h. Such processes, producing fusion of some elements, cause the reduction in the concentration due to the effects of vaporisation and diffusion, so that sulphur can be almost absent in clay, while strontium and calcium can be reduced to a concentration of about one-tenth of the value in the clay, according to the experimental measurements reported in Table 6.

Table 6.

Comparison between the main ratios in Lipari kaolin and the corresponding mean value for the four findings analysed.

M. Elias et al. [25] reported on the characterisation of the wide colour range of ochres from pale yellow to dark red. Ochres contain varying amounts of octahedral iron oxides, namely hematite (αFe2O3) and/or goethite (αFeOOH), and of white pigments (alumino-silicate such as kaolinite or illite, quartz, and calcium compounds such as calcite, anhydrite, gypsum, or dolomite). When the hematite is the main iron oxide, a red colour is observed, whereas the ochre is yellow when the goethite dominates. These colours are due to the ion Fe3+ contained in both oxides and, more precisely, to the charge transfer between Fe3+ and its ligands O2− or OH−. The pXRF spectra obtained from the pigments of the archaeological artifacts (white pigment) reveal a predominance of calcium (Ca) and iron (Fe). The high Ca content suggests the presence of a calcium-based white pigment, most likely calcium carbonate (CaCO3), commonly used in the past as chalk or lime white. The presence of Fe could indicate the use of non-pure natural sources, such as crushed limestone containing iron oxides.

The black pigment shows significant amounts of iron (Fe) and manganese (Mn), consistent with the use of manganese-rich earth pigments. Moreover, the content of iron in the black pigment could originate from magnetite (Fe3O4) or charcoal-based black mixed with iron-rich materials typical of Lipari, due to the volcanic activity.

The red pigment is characterised by a dominant concentration of Fe, suggesting the use of iron oxide-based pigments, such as hematite (Fe2O3), commonly known as red ochre. As reported in the literature [25], red ochres have been used for centuries for their strong and stable colour, and their iron content makes them easily identifiable through pXRF analysis.

The clay matrix on the rear side of the antefix reveals the presence of Fe, Ca, and Ti, a typical signature for natural clay materials. The presence of Ti is particularly indicative of illite or anatase-bearing clays, commonly used in ancient ceramics. These elements suggest a local clay source with a natural composition rich in iron and titanium-bearing minerals.

The attribution of a Greek manufacture [5], rather than local, derives from the concentrations of nickel and chromium, which are described as two elements’ indicators of provenance [26] connected to the different geological constitution of the two territories.

According to Barone et al. [5], clays from the Messina Strait area exhibit CaO contents ranging from ~6 to ~20%. This supports the hypothesis of a local production of Corinthian-style pottery with low calcium-clays. Barone showed that items coming from Lipari, which date back to the period Early Corinthian–Late Corinthian II, contain low concentrations of Ni, Cr, and Sr amounts; they could be ascribed to a “local” (Southern Italy) manufacture. Moreover, a higher level of clay minerals and feldspars composed primarily of silicon, aluminium, oxygen, and one or more alkali or alkaline earth metals (sodium, potassium, calcium), as shown in the pXRF spectra, is typical of the Southern areas [27]. The present manuscript, focused on the content of other elements rather than Ni or Cr in both ceramics as well as the local kaolin, was carried out to collect enough elements to have a valuable insight into the provenance of the studied artifacts.

4. Discussion

The pXRF analyses of the four ceramic fragments revealed clear compositional distinctions between the pigments and the underlying clay matrix. White pigments consistently showed elevated Ca content, red pigments were dominated by Fe, and black pigments contained both Fe and Mn. Statistical analyses (one-way ANOVA and Welch’s t-tests) confirmed that these differences are significant, while the clay matrix exhibited a relatively more homogeneous composition. This indicates that artisans deliberately selected and applied different raw materials for each pigment, reflecting intentional technological choices rather than random variability.

Comparison with local Lipari kaolin suggests that the elemental composition of the pigments is compatible with naturally occurring deposits on the island, modified by thermal treatments during firing. The observed reduction in elements such as S, Ca, and Sr in the fired ceramics aligns with the volatilisation and diffusion effects, supporting the hypothesis that local materials were adapted for pigment production using controlled firing processes. These findings point to an understanding of the chemical and physical properties of the raw materials, consistent with established ancient practices of pigment preparation and application.

The compositional similarities among fragments further suggest standardised production protocols, while minor variations reflect either the local heterogeneity of raw materials or artisanal choices in pigment mixing and application. The predominance of Fe and Mn based pigments agrees with broader Mediterranean practices, indicating that local production could reproduce colours comparable to imported Corinthian ceramics without implying direct importation.

In this study, methodological limitations must be considered. Sampling constraints limited analyses to selected representative spots on four fragments, potentially overlooking the full heterogeneity of pigments and the ceramic matrix. Instrumental factors, including the surface roughness, pigment layer thickness, and minor instrument drift, may contribute to analytical variability. Quantification relied on semi-quantitative XRF calibration using metal foils without certified ceramic references, and firing processes may have caused partial element redistribution. Despite these constraints, the observed compositional differences are well above analytical noise, supporting the robustness of the relative comparisons between pigments and the clay matrix.

However, the study highlights the connection between material properties, pigment technology, and regional resources. By integrating chemical analyses with archaeological context, the results provide evidence on the use of locally sourced raw materials in pigment production, offering new insight into the technological capabilities and material networks of ancient Aeolian communities. Future studies could extend these observations by including additional samples, alternative clay sources, or complementary analytical techniques to further refine interpretations of provenance and production practices.

5. Conclusions

The aim of this study is not to restart the debate over the Corinthian origin of the Lipari findings, but rather to investigate the composition of pigments and clay matrices and to provide insights into ancient pigment preparation and material selection. The combination of in situ pXRF analyses and statistical assessment (ANOVA, post hoc Tukey tests, and Welch’s t-tests) allows us to differentiate the elemental composition and pigment. The analyses confirmed that the red, black, and white pigments are chemically distinct from each other and from the clay matrix. White pigments are dominated by calcium, red by iron, and black by iron and manganese. The clay matrix is comparatively more homogeneous, suggesting a common base to which pigments were applied. Concerning the technological implications, the compositional patterns indicate that ancient artisans deliberately selected and processed raw materials to achieve the desired colours, demonstrating controlled pigment preparation techniques. Mixtures of Lipari kaolin with CaCO3, Fe2O3, Fe3O4, and MnO effectively produced white, red, and black pigments, consistent with the archaeological samples.

The results provide evidence of good knowledge of local resources and material properties. The exploitation of local kaolin and mineral additives reflects the relation between available raw materials, technical choices, and aesthetic objectives in ancient ceramics production. The historical and archaeological significance to this study is provided by the observation that compositional analysis can highlight on regional production practices, resource use, and technological processes. The statistical analysis strengthens the confidence in the observed compositional differences and supports the reproducibility of the results. Future work could expand the dataset to additional fragments, incorporate controlled firing experiments, and employ certified reference materials to refine quantitative interpretations, thereby further elucidating ancient pigment technology and provenance.

This study demonstrates that combining elemental analysis with statistical evaluation provides a powerful framework to understand both the technological knowledge of ancient artisans and the archaeological context of pigment use, linking materials science approaches with historical interpretation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.I. and M.C.; software, A.I. and M.C.; formal analysis, A.I., M.C., A.T. and L.T.; data curation, A.I.; writing—original draft preparation, A.I., M.C. and M.A.M.; writing—review and editing, A.I. and M.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The long-term conceptual development project of the Nuclear Institute of the Czech Academy of Sciences RVO 61389005 supported this work. The authors acknowledge the assistance provided by the Advanced Multiscale Materials for Key Enabling Technologies project, supported by the Ministry of Education, Youth, and Sports of the Czech Republic. Project No. CZ.02.01.01/00/22_008/0004558, Co-funded by the European Union.—AMULET project.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author(s).

Acknowledgments

The Authors gratefully acknowledge D. Bonanno, from the Dipartimento di Scienze Matematiche e Informatiche, Scienze Fisiche e Scienze della Terra (MIFT) of Messina University, for his appreciable contribution in the design and construction of the mechanical support of the experimental set-up employed during the pXRF analyses.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- McPhee, I.D.; Kartsonaki, E. Red-figure pottery of uncertain origin from Corinth: Stylistic and chemical analyses. Hesperia 2010, 79, 113–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacci, G.M.; Barone, G.; Mastelloni, M.A.; Mazzoleni, P.; Mondio, G.; Pezzino, A.; Serafino, T.; Triscari, M. Mineralogical, petrographic, and chemical analyses on small perfume vases found in Messina and dated to VII century B.C. Mediterr. Archaeol. Archaeom. 2006, 6, 11–19. [Google Scholar]

- Tsiafakis, D.; Manakidou, E.; Sakalis, A.J.; Tsirliganis, N.C. The ancient settlement at Karabournaki: The results of the Corinthian and Corinthian type pottery analysis. In Meetings Between Cultures in the Ancient Mediterranean, Proceedings of the 17th International Congress of Classical Archaeology, Rome, Italy, 22–26 September 2008; Dalla Riva, M., Di Giuseppe, H., Eds.; Bollettino di Archeologia Online; Available online: https://www.ancientportsantiques.com/wp-content/uploads/Documents/PLACES/GreeceContinental/ThermeKellarion-Tsiafakis2010.pdf (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Finocchiaro, C.; Barone, G.; Mazzoleni, P.; Spagnolo, G. New insights on the archaic ‘Corinthian B’ amphorae from Gela (Sicily): The contribution of the analyses of Corfu raw materials. Mediterr. Archaeol. Archaeom. 2018, 18, 179–189. [Google Scholar]

- Belfore, C.M.; Mastelloni, M.A.; Barone, G.; Mazzoleni, P. In situ XRF investigations to unravel the provenance area of Corinthian ware from excavations in Milazzo (Mylai) and Lipari (Lipára). Herit. Sci. 2022, 10, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amyx, D.A. Corinthian Vase-Painting of the Archaic Period; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1988; Volumes 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Cardon, D. Natural Dyes: Sources, Tradition, Technology and Science; Archetype: London, UK, 2007; ISBN 190498200x. [Google Scholar]

- Melo, M.J. History of natural dyes in the ancient mediterranean world. In Handbook of Natural Colorants; Bechtold, T., Mussack, R., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons: Chichester, UK, 2009; pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Miliani, C.; Monico, L.; Melo, M.J.; Fantacci, S.; Angelin, E.M.; Romani, A.; Janssens, K. Photochemistry of artists’ dyes and pigments: Towards better understanding and prevention of colour change in works of art. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 7324–7334. [Google Scholar]

- Sakalis, A.; Tsiafakis, D.; Tsirliganis, N. Non destructive elemental ceramic analysis from Achaea using X-Ray fluorescence spectroscopy (m-XRF). Appendix. In Thapsos-Class Ware Reconsidered: The Case of Achaea in the Northern Peloponnese; Gadolou, A., Ed.; BAR International Series 2279; BAR Publishing: Oxford, UK, 2011; pp. 89–117. [Google Scholar]

- Liritzis, I.; Zacharias, N. Portable XRF of archaeological artefacts: Current research, potentials and limitations. In X-Ray Flourescence Spectrometry in Geoarchaeology; Shackley, S., Ed.; Natural Sciences in Archaeology Series; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 109–142. [Google Scholar]

- Liritzis, I.; Xanthopoulou, V.; Palamara, E.; Papageorgiou, I.; Iliopoulos, I.; Zacharias, N.; Vafiadou, A.; Karydas, A.G. Characterization and provenance of ceramic artifacts and local clays from late Mycenaean Kastrouli (Greece) by means of P-XRF screening and statistical analysis. J. Cult. Herit. 2020, 46, 61–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torrisi, L. Nuclear reaction applied to fluorine depth profiles in human dental tissues. Pol. J. Med. Phys. Eng. 2019, 25, 193–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amptek. Available online: http://www.amptek.com/ (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Benyaich, F.; Makhtari, A.; Torrisi, L.; Foti, G. PIXE and XRF comparison for applications to sediments analysis. Nucl. Instr. Methods Phys. Res. 1997, B132, 481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- QTIPLOT, Actual Site 24 September 2024. Available online: http://alternativeto.net/software/qtiplot/ (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Torrisi, L.; Italiano, A.; Cutroneo, M.; Gentile, C.; Torrisi, A. Silver coins analyses by X-ray fluorescence methods. J. X-Ray Sci. Tech. 2013, 21, 381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mastelloni, M.A.; Di Bella, M.; Baldanza, A.; Sabatino, G. Terrecotte architettoniche di Lipari: Note su influssi formali e dati tecnici da analisi sperimentali. In Deliciae Fictiles V. Networks and Workshops: Architectural Terracottas and Decorative Roof Systems in Italy and Beyond; Oxbow Books: Oxford, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torrisi, L. Micron-size particle emission from bioceramics induced by pulsed laser deposition. Bio-Med. Mat. Engeen. 1993, 3, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pappalardo, G.; Costa, E.; Marchetta, C.; Pappalardo, L.; Romano, F.P.; Zucchiatti, A.; Prati, P.; Mandò, P.A.; Migliori, A.; Palombo, L.; et al. Non-destructive characterization of Della Robbia sculptures at the Bargello museum in Florence by the combined use of PIXE and XRF portable systems. J. Cult. Herit. 2004, 5, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://www.jmp.com/it/statistics-knowledge-portal/one-way-anova (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Available online: https://www.originlab.com/ (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Available online: https://sites.nicholas.duke.edu/statsreview/means/welch/ (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Guiso, M. Chimica dei Pigmenti, Università di Ferrara, Actual Web Site 2017. 2015. Available online: www.unife.it/scienze/beni.culturali/insegnamenti (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Elias, M.; Chartier, C.; Prevot, G.; Garay, H.; Vignaud, C. The colour of ochres explained by their composition. Mater. Sci. Eng. B 2006, 127, 70–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, R.E. Greek and Cypriot Pottery A Review of Scientific Studies; Fitch Laboratory Occasional Paper; Publisher British School at Athens: Athens, Greece, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Barone, G.; Mazzoleni, P.; Spagnolo, G.V.; Raneri, S. Artificial neural network for the provenance study of archaeological ceramics using clay sediment database. J. Cult. Herit. 2019, 38, 147–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).