Abstract

The conservation of cultural heritage increasingly requires a transition from emergency restoration to preventive and planned strategies supported by systematic data management. Within this context, this paper, conceived as a project report, presents the methodological premises, operational framework, and preliminary outcomes of the Fountains and Monuments in the Public Space of the City of Turin project, developed within the CHANGES Project—National Recovery and Resilience Plan (NRRP), funded by the European Union—NextGenerationEU. The project explores the integration of preventive and planned conservation methodologies with digital tools for the sustainable management of outdoor cultural heritage. Five case studies in Turin, identified in collaboration with local authorities, provided the basis for developing a protocol for planned conservation. A digital platform was designed as the operational tool of this protocol, integrating georeferenced data, 3D models, interactive dashboards, and modules for inspection, planning, and monitoring. The platform enables data-driven prioritisation of interventions, traceability of conservation activities, and long-term documentation management. Although still at the demonstrator stage, it shows potential for scalability and transferability. The study concludes that the integration of interdisciplinary expertise and digital innovation can effectively support preventive and planned conservation, strengthening the systematic management of outdoor cultural heritage.

1. Introduction

The present paper, conceived as a project report, illustrates the methodological premises, operational framework, and preliminary outcomes of the Fountains and Monuments in the Public Space of the City of Turin project, developed within the framework of the CHANGES Project—National Recovery and Resilience Plan (NRRP), funded by the European Union—NextGenerationEU. Within this context, the project investigates how preventive and planned conservation methodologies can be effectively integrated with digital tools for the management of outdoor cultural heritage. In doing so, it reflects the applied dimension of research, in which the interplay between scientific knowledge, technological innovation, and institutional collaboration contributes to the development of new models for sustainable heritage management.

1.1. Preserving Through Planning: Themes and Opportunities

The theme of preventive and planned conservation of cultural heritage is now well-established and widely discussed in terms of conceptual debate and within the regulatory framework, not only in Italy but also within a broader and more diverse European and international context [1,2,3,4,5,6]1 2. The European Framework for Action on Cultural Heritage (2018–2020) [7], together with subsequent guidelines from the Council of Europe and UNESCO [8], placed the concept of multilevel governance and transnational cooperation at the heart of the cultural heritage debate. In this context, preventive and planned conservation has taken on a strategic role as a tool of cultural diplomacy and scientific collaboration, capable of promoting common standards and shared methodologies for the management of risk, deterioration, and the sustainability of heritage. Moreover, the 2015 report Cultural Heritage Counts for Europe highlighted that, in order to maximize the benefits deriving from cultural heritage, it was necessary to integrate conservation efforts with synergistic and planned measures, the result of conscious economic and cultural policy choices [9,10,11]. This approach was perfectly in line with the principles of planned conservation, which regards preservation not as an isolated act, but as part of a sustainable and continuous management strategy.

The European Year of Cultural Heritage 2018 represented a crucial milestone in this journey, the result of a broad and shared reflection that opened up new perspectives for a true «laboratory for innovation based on cultural heritage» [12]. The European Commission, seizing the opportunity presented by the European Year, promoted holistic, inclusive, and integrated approaches that are people-centred and managed in a participatory manner. The governance of the initiative involved a platform of national coordinators and a committee of thirty-five representatives from civil society and international organisations—including UNESCO and the Council of Europe—in ongoing dialogue with all European institutions: the Commission, the Parliament, the Council of the EU, and the Committee of the Regions. The outcomes of this participatory approach were significant, both in terms of public engagement and operational results, as confirmed by the European Commission’s evaluation report. To consolidate and build on the results of the European Year, the Commission launched the European Framework for Action on Cultural Heritage at the end of 2018. This framework set out sixty concrete actions for the 2019–2020 period, inviting Member States and Regions to voluntarily develop similar plans.

The plan is based on the principles of an integrated, participatory, and evidence-based approach, and is structured around five key objectives: access and participation, sustainability, safeguarding, research, and international cooperation. In continuity with this methodological framework, the reflection on the quality of interventions promoted by ICOMOS on behalf of the European Commission has completed the system of European principles, defining a shared reference model for the quality and sustainability of conservation. Consistently, the projects funded under Horizon 2020 [13] and the Joint Programming Initiative on Cultural Heritage (JPI CH) [14] have supported interdisciplinary research focused on environmental monitoring, predictive diagnostics, risk assessment, and planned management of cultural heritage—all key elements of preventive and planned conservation. However, the practical implementation of these principles—for many reasons, ranging from the availability of resources, tools, and skills to organizational capacities, political choices, and regulatory constraints—is still predominantly reactive rather than preventive, with an emergency-oriented approach that leaves little room for planned strategies.

Preserving through planning rather than reacting to urgent situations is a desirable practice, not only for the sake of safeguarding, protecting, and passing on cultural heritage to future generations, but also from the perspective of sustainability regarding economic and human resources, especially in a system, such as that of cultural heritage, which can no longer rely solely on centralised interventions for its sustenance. This approach, widely recommended in scientific and institutional circles [15,16,17,18,19,20,21], implies a significant cultural transition that focuses not only on cultural heritage, but also on the management context in which it is embedded, promoting the integration of systemic and interdisciplinary practices that ensure its long-term preservation, facilitating a comprehensive and coordinated approach among the various players involved, including researchers, public and private managers, and heritage protection authorities. Conservation activities should therefore be increasingly understood not primarily as direct action on cultural heritage. Rather, they should be seen as a strategy that rationalises its management in terms of effectiveness and efficiency, focusing on prevention and ongoing maintenance, articulated in a process of producing new knowledge and building layered information [22]. This is precisely what Article 29 of the Italian Code of Cultural Heritage and Landscape (Legislative Decree 42/2004) stipulates when, in paragraph 1, it identifies “coherent, coordinated and planned study, prevention, maintenance and restoration activities” [23] as the means to ensure the conservation of cultural heritage.

Another crucial aspect concerns the use, conservation, enhancement, and accessibility of the data produced by the activities mentioned in the Italian Code, particularly in relation to the digitisation of services, which represents a key element in both the Italian digital agenda and European policies [23,24,25,26]. These premises also gave rise to the project Fountains and Monuments in the Public Space of the City of Turin, which Fondazione 1563 is carrying out as part of Spoke 6 of the CHANGES Project-NRRP Mission 4, Component 2, Investment 1.3, funded by the European Union-NextGenerationEU, dedicated to the themes of History, Conservation and Restoration of Cultural Heritage [27].

1.2. Project Partners: Roles and Responsibilities

The CHANGES Project is an extended national research partnership that brings together eleven Italian universities, research institutions and centres of excellence dedicated to the advancement of knowledge, innovation and technological transfer in the cultural heritage field. Within this primarily academic ecosystem, Fondazione 1563 plays a distinctive role, as a private non-profit organisation based in Turin [28].

It actively engages with institutional players in the local area, such as conservation bodies, public administrations, as well as the University of Turin and the Politecnico, with which it collaborates on research programmes spanning from the Baroque era to global history and ancient and contemporary philanthropy. It also focuses on experimenting with new digital tools. Fondazione 1563 safeguards and preserves the historical archives of the Compagnia di San Paolo, an institution founded in Turin in 1563 initially to support the poor and needy [29,30]. The Compagnia later evolved into the main credit institution in the area until it became the current Fondazione Compagnia di San Paolo, one of the largest philanthropic organisations in Europe, with which Fondazione 1563 is also affiliated. This framework of affiliations is not merely genealogical; it serves to explain the identity and role of Fondazione 1563 within a broader context that combines humanistic research, the operational management of cultural projects, and a commitment to heritage enhancement, in line with the policies pursued by Fondazione Compagnia di San Paolo3 [31,32], particularly with regard to restoration, conservation and systemic action for the enhancement of cultural heritage4 [33]. This structural link enables the development of projects that combine scientific rigour, financial sustainability, and strong local roots, which are essential to effectively address the complexity of cultural heritage management.

In this capacity, Fondazione 1563 leads the design and management of the Fountains and Monuments project and, to develop its technical and scientific components, has implemented a collaborative model involving four organisations that form a local micro-hub of expertise: Fondazione Centro Conservazione e Restauro “La Venaria Reale” (CCR), Fondazione LINKS and Ithaca S.r.l. Each entity contributes complementary skills, ranging from conservation science and preventive methodologies to geospatial analysis and digital system development.

CCR is a non-profit foundation for advanced training and research in the field of cultural heritage conservation [34]. Within the project, it was responsible for investigating, both methodologically and operationally, aspects relating to the conservation of cultural heritage in outdoor public spaces. It developed strategies for risk prevention and planned maintenance as well as collaborated on drafting a specific management protocol.

Fondazione LINKS is a research centre and instrumental body of the Politecnico of Turin, specialising in digital technologies, territorial development and innovative projects in various sectors, including Cultural Heritage, Industry 4.0, smart mobility, agritech, space economy and smart infrastructure [35]. It was responsible for mapping the workflow of conservation activities already adopted by the City of Turin, which owns the assets studied for the Fountains and Monuments project. It also identified and selected the most innovative technologies to support preventive conservation activities, contributed to drafting the management protocol, and, in close collaboration with Ithaca S.r.l., designed and developed a digital platform as a demonstrator for the implementation of preventive and planned conservation plans for outdoor assets.

Ithaca S.r.l. [36] is an innovative company in the field of geographic and cartographic data acquisition, management and processing. For the project, it focused on the architecture of the database that supports the demonstrator, in order to deliver an agile application that meets the users’ needs while remaining firmly grounded in methodological research on restoration and conservation of cultural heritage.

The four organisations involved in the project constitute a local micro-hub, integrating expertise, knowledge, and professional networks. They are non-profit foundations and research bodies with strong contextual awareness of the territory in which they operate and its specific needs, maintaining continuous engagement with private actors, public administrations, and a wide range of stakeholders. This positioning has enabled the micro-hub to identify critical gaps as well as opportunities for innovation, in line with the operating principles of the Spoke 6: “innovative approaches and IT tools, both to deepen the knowledge, conservation, and transmission of historical and artistic heritage, and to support the collection, use, and analysis of data” 5.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Outdoor Cultural Heritage: Fountains and Monuments as Case Studies

The Fountains and Monuments project conceived as a pilot which, on the one hand, seeks to define, through both fundamental and applied research, a functional protocol for the management of preventive conservation and planned, coordinated and continuous maintenance plans for outdoor heritage. On the other hand, it aims to develop, in the form of a demonstrator, a multi-technology platform for trusted long-term archiving, management and exploitation of the data generated through the application of this protocol. Two overarching objectives underpin these lines of investigation: to provide public administrations with new, sustainable, and effective management and organisational tools that support data-driven decision-making processes, and to foster technological and disciplinary development in the conservation sector, thereby facilitating the transition from emergency-driven restoration to the systematic implementation of conservation plans.

2.2. Case Selection Criteria

The working team began by identifying the specific needs of a particular category of assets, fountains and monuments, selected due to urgent conservation and management issues reported by their owner, the Municipality of Turin. In addition to the methodological challenge—namely the study and monitoring of assets located in outdoor public spaces and particularly exposed to anthropogenic and environmental risks—the decision was also informed by a sense of public accountability: to give back to the community the benefit of having enjoyed public funding, by focusing on heritage assets that are freely accessible and visible to all, meaning available to everyone, free of charge and freely accessible, and whose enjoyment and usability cannot be denied to anyone.

The collaborative relationships and knowledge gained with public administrations, deriving from the experience of the entities comprising the project’s micro-hub, enabled the establishment of a fruitful dialogue with the Superintendence of Archaeology, Fine Arts and Landscape for the Metropolitan City of Turin and the Municipality of Turin, with which a permanent technical committee has been set up and a scientific collaboration agreement signed.

2.3. Description of Selected Assets

Together with representatives of the municipal administration and the Superintendency, five monuments were identified in Turin’s urban heritage. The selection was based on criteria of type (monument; monument–fountain; fountain; modern art monument), exposure (fully exposed artefacts; artefacts attached to buildings), context (urban environment; gardens), constituent materials (stone, metals and alloys, plaster, brickwork) and state of conservation (recently restored; subject to recurring maintenance; subject to safety measures; requiring restoration). The outcome was a heterogeneous and diversified case study, designed to address the project’s research questions.

The selected sites are 6:

- Monument–fountain to the Fréjus Tunnel, 1879, Piazza Statuto (monument–fountain; fully exposed; urban setting; stone and metals; safety measures) (Figure 1) [37,38,39].

Figure 1. Luigi Belli and Odoardo Tabacchi, Monument–fountain to the Fréjus Tunnel, Turin, 1879.

Figure 1. Luigi Belli and Odoardo Tabacchi, Monument–fountain to the Fréjus Tunnel, Turin, 1879. - Monument to Camillo Benso, Count of Cavour, 1865–1873, Piazza Carlo Emanuele II (monument; fully exposed; urban setting; stone and metals; recently restored) [40,41].

- Monument to Angelo Brofferio, 1871, Piazza Vincenzo Arbarello (monument; fully exposed; garden; stone; recently restored) [42,43,44].

- Fountain in Via Santa Chiara, attached to the rear of the church of the same name (fountain; leaning against a building; stone and metals; safety measures) [45].

- Monument to the Italian Military Driver, 1961, Corso Unità d’Italia (monument; fully exposed; garden; stone, metals and concrete; safety measures) [46].

These works are listed under the Italian Code of Cultural Heritage and Landscape (Legislative Decree 42/2004), which subjects them to specific protection and conservation regulations [47]. The fountain in Via Santa Chiara, built in the early 1930s, represents a particular case: it was chosen primarily because of its conservation condition. At the start of the project, it exhibited a widespread state of deterioration and had been severely damaged by an act of vandalism, with graffiti covering its entire surface. The Municipality of Turin intervened in the spring of 2024 with a thorough cleaning operation. The fountain is still not operational, partly owing to moisture-induced deterioration affecting the adjacent choir of the Church of Santa Chiara, designed by the architect Bernardo Antonio Vittone and built between 1742 and 1745. This intervention established a sort of “zero point” for recording the conservation state and for applying the procedures subsequently developed within the research project.

2.4. The Fréjus Tunnel Monument: A Model Case

The inspections carried out by CCR working group, which included restorers, scientists, and art historians, enabled an analysis of the state of conservation and of the environmental and anthropogenic factors. Within this framework, the Fréjus Tunnel monument–fountain was identified as the most complex case and therefore chosen as the initial sample for in-depth investigation (Figure 1). A model survey form was developed on the basis of this monument, designed to capture systematically the visible alterations, their causes, and possible interventions [48,49]. From this model, two parallel lines of work were undertaken: on the one hand, the form was used by the technical partners to structure the architecture and functionalities of the digital platform; on the other, it was applied by the conservation team to carry out systematic surveys of all five case studies, supported by extensive photographic documentation. The combination of these two processes ensured that the Protocol developed within the project was grounded both in real data collected on the monuments and in a digital platform that mirrors its operational procedures while enabling the management and standardisation of conservation data.

The monument, created by Luigi Belli and Odoardo Tabacchi and inaugurated in 1879 to celebrate the Cenisio-Fréjus railway tunnel, depicts a pyramid of rocks which, collapsing under the feet of a Winged Genius, symbol of triumphant science, drag seven Titans down with them. The Genius, scenographically placed at the top with a pen in his hand, appears to inscribe the names of the engineers Germain Sommeiller, Sebastiano Grandis and Severino Grattoni, designers of the tunnel, on the stone. The Titans, crushed by the rocks, evoke the brutal nature subdued by scientific progress. The monument stands in the centre of an elliptical basin that collects the water gushing from the boulders, thus recalling Alpine torrents.

The complexity of the fountain monument is due to multiple features, including:

- constituent materials: blocks of Cenisio serpentine schist for the pyramid; white Viggiù marble for the statues of the Titans; bronze for the statue of the Winged Genius; stone for the basin; hydraulic pump to feed the waterfall.

- Compositional technique: the stone blocks stacked in a pyramid structure are bonded together with cement mortar; the statues of the Titans consist of pieces carved separately and assembled on site with metal pins and mortar; the Winged Genius is composed of separately cast bronze blocks, joined with metal pins and welded using lead.

- Dimensions: height 20 m; base width of the pyramid 9 m; estimated weight 150,000 kg; maximum diameter of the elliptical basin 24 m.

- Location: positioned in one of the city’s main squares, subject to heavy vehicular traffic and local public transport (buses and trams), with underground railway lines.

- State of conservation: the materials show widespread alteration, including surface deterioration, exfoliation, corrosion, black crusts, biological colonisation, invasive vegetation, algae, and inconsistent deposits of dirt. Structural detachments and collapses present a serious risk: the earliest intervention dates to 1909 (renovation of one Titan’s arm and consolidation), while the most recent occurred in 2021, when the right leg of the central Titan was replaced with a fibreglass cast after detachment [50].

Based on preliminary data collected during an initial inspection phase, several conservation form models already in use by CCR were tested in order to refine lists of deterioration and alteration causes with their specific effects in the field of stone artefacts. The aim was to establish as direct a connection as possible between the visible effects on the surface, their underlying causes, and the potential remedial actions.

The systematic collection of past documentation relating to recent maintenance or restoration work, the adoption of controlled vocabularies, the analysis of visible alterations to the monument and research into their causes have led to the creation of a form for recording the current state of the monument. This form is structured in fields that can be filled in and replicate as needed for recording and comparison over time and is designed to assist field surveyors and to assess the feasibility of scheduled maintenance or restoration work.

The rationale behind the compilation of the various sections is based on the possibility for the surveyor to report concisely and systematically the largest amount of data characteristic of the artefact that is relevant in terms of risk assessment, intervention planning and mitigation of the causes of deterioration. The form, which can be used in ordinary conservation activities, has been supplemented with a section dedicated to metals, for which the restorers at CCR specialising in this field developed a specific glossary for describing the different deterioration phenomena, analysed in terms of extent, severity, probable causes, priority and methods of intervention related to the analysis conducted. As with stone materials, a pre-assessment section was also included for metals, designed to assign intervention priorities on the basis of the alteration’s impact on the integrity and legibility of the artefact under analysis.

The involvement of biologists and scientists within the working group, focusing on microclimate analysis and integrated risk assessment, further expanded the form to encompass biological risks and biodeterioration phenomena, together with the detection and recording of environmental data. Functional fields were proposed to capture information on microclimatic conditions (air temperature, surface temperature of the monument) and meteorological variables. In addition, detailed studies were carried out on the currently available sources of meteorological data measured in 2023.

3. Results

3.1. The Protocol: Goals, Application, and Tools

The Protocol is intended to provide public administrations with guidelines for putting planned and preventative conservation strategies into practice and, most importantly, to implement coordinated and ongoing maintenance. Although developed for the five case studies selected within the project, its methodology and structure can readily be extended to other outdoor assets, whether publicly owned or managed by third parties.

The Protocol is structured as a detailed, sequential procedure for collecting data on the state of conservation of fountains and monuments located in public spaces in the city of Turin. Its operational instrument is a multi-technology platform, specifically designed and developed for the project, which enables not only long-term archiving but, crucially, the contextual and cross-sectional management of the data.

While the Protocol takes its initial structure from the survey forms developed for each case study, significant analytical effort has gone into in organising the information as an ecosystem that reflects a systemic approach, in which each asset is organically linked to the others. In this perspective: the monument—with data on its registry, conservation history, current condition, design, and interventions—represents a sort of subset within a larger apparatus in which the elements share, for example, records on the scheduling of planned, programmed and executed interventions, the registry of companies commissioned over time to carry out the work, and the cataloguing of those involved in surveying, design, and conservation activities.

The definition of information flows, together with the clear allocation of roles and responsibilities, represents an essential component in ensuring the overall effectiveness of the system. This structuring not only supports the internal coherence of the process but also facilitates the replicability of the model across other urban assets or, more broadly, in different contexts.

The Protocol’s operating procedure is summarised in Table 1. The survey form represents the basic tool for on-site condition assessment, while the operating procedure formalises its structure into a workflow and digital management framework within the platform. The left-hand column lists the macro-activities, arranged in a logical sequential order, to be implemented for the planned conservation and maintenance of outdoor assets; the right-hand column shows the reference data to be collected and managed for each activity using the platform.

Table 1.

Operational procedure.

3.2. The Platform

The platform, developed as a prototype and proof of concept, represents the operational implementation of the Protocol. It is conceived as an enabling tool for the effective management of planned conservation and maintenance of outdoor heritage assets, supporting both survey activities and the planning and monitoring of interventions by the competent authorities.

The system centralises all information in a single accessible digital environment, eliminating duplication and repetition and overcoming the frequent problem of hybrid paper and digital archiving. Given the constraints and objectives of the Fountains and Monuments project, the platform has been developed as a demonstrator in order to showcase its potential. However, it already includes features and characteristics that allow for scalability and exportability to other contexts, such as, for example, application to other types of assets, use on assets located in indoor spaces, or adoption by a variety of managing bodies.

The platform is configured as a geospatial database, i.e., a data repository within a geographic information system (GIS), to enable the georeferencing of assets of interest and to allow for the management and structured organisation of descriptive data. Its architecture is divided into four main sections: Monument, Condition Survey, Interventions, and Conservation Context.

Each asset is described in the Monument section (Figure 2), which, in addition to providing information on the ownership and management of the asset, identifies its structural elements and assigns each of them a unique identifier. This ensures full traceability of the structural components that make up the asset within the information system.

Figure 2.

Screenshot of the platform’s form with the 3D model of the Fréjus fountain monument. The left panel displays the interactive 3D model, where compositional elements can be visually identified and selected. In this example, one of the Titan figures is selected and associated with the unique code MO29/D01. The right panel (“Monumento” section i.e., Monument) collects the corresponding descriptive data and photographic documentation for the selected element 7.

For each asset, the platform also provides:

- an interactive 3D model, navigable from multiple viewpoints, which enables the user to accurately identify the constituent elements of the monument, highlighting their position and facilitating their identification within the structure. This feature allows operators involved in site inspections to carry out a direct and intuitive spatial analysis, with integrated support between technical data and three-dimensional representation (Figure 2).

- A 360° view of the surrounding context, which makes it possible to examine the environment in which the asset is located, through technology similar to virtual tours (on the platform, referred to as the Conservation Context).

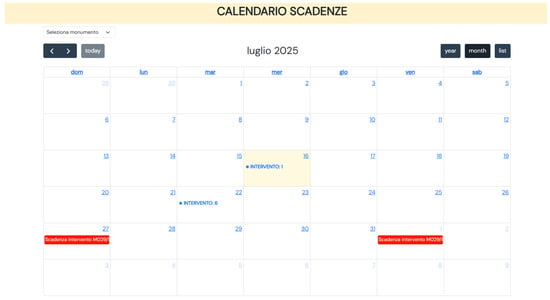

The platform’s Condition Survey module makes it possible to systematically document the state of conservation of the asset, detect any signs of deterioration and contribute to the assignment of intervention priorities according to the critical issues identified. Based on the combination of the degree and percentage of damage, the system automatically calculates, using preset parameters, the level of urgency with which maintenance work should be carried out, and assigns a deadline (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Screenshot of the platform’s calendar with the scheduled interventions. This example displays two planned interventions (Intervento 1 and Intervento 6) generated within the proof-of-concept testing phase of the platform. The calendar highlights in red the upcoming deadlines associated with the coded monument element MO29/D01, demonstrating how the system manages and visualises multiple scheduled actions over time on the same asset. In addition, the drop-down menu in the top left corner allows the user to select the specific monument of interest 8.

The platform also includes an interactive dashboard, which allows users to view key indicators relating to the state of conservation of assets; receive automatic alerts, generated from data collected during inspections, which indicate the severity of the deterioration observed; manage the scheduling of interventions, with dynamic updates based on maintenance needs identified in the field.

The Interventions module is dedicated to maintenance planning in response to the deterioration phenomena detected and based on the corresponding level of urgency. It is organised into two sections: “planning new interventions”, which semi-automatically generates a form indicating the type of intervention to be undertaken, its frequency, timing and estimated costs; “intervention status”, which distinguishes between interventions to be approved, executed, and is reserved for those responsible for validating interventions.

4. Discussion

The platform is still in the testing phase and will be presented to institutional stakeholders—specifically, the City of Turin and the Superintendency—by the end of the CHANGES project (February 2026), in order to verify if the requirements emerging from technical meetings and ongoing discussions have been met, and to confirm that both the management information system and the Protocol underpinning it are effective tools for implementing preventive and planned conservation of cultural heritage. The platform is intended to support the adoption of the Protocol and represents an innovative tool for the systematic management of cultural heritage. It currently allows for the collection and organisation of data relating to the state of conservation, the planning of maintenance activities, and the traceability of both maintenance operations and any conservation treatments.

As a prototype and proof of concept, the system must be regarded as an experimental product designed to meet the research objectives of the project, while keeping a constant focus on end users, that is, the public administration staff responsible for managing Turin’s fountains and monuments. Being a demonstrator, some functionalities have not been implemented at this stage, since the design concentrated on testing workflows, data structures, and usability for conservation professionals. For instance, the prototype does not currently allow the updating of 3D models and 360° views of the assets and their surroundings. Instead, it supports the continuous upload of photographic documentation, which can effectively track and visualise changes in the conservation state over time. This limitation reflects the nature of the platform as a demonstrator: the development focused on validating processes and user interaction rather than delivering a tool for large-scale deployment. Should the platform evolve into a tool formally adopted by heritage authorities, the integration of features enabling the updating and versioning of 3D models and 360° views would be both technically feasible and highly valuable. However, such developments involve long-term management, economic sustainability, and scalability issues that go beyond the scope of the prototyping and technology transfer phase undertaken within the project. These aspects have already been considered by the research team in evaluating the potential of a project spin-off and the possible commercialisation of the platform.

Building on these reflections, the system also shows significant potential for further development, which could be activated with the continued growth of the project. Future directions include enhancing its effectiveness, improving its interoperability with other systems, and strengthening its long-term impact. In this perspective, the working group has already evaluated the introduction of multi-user and multi-level management, which would allow a distinction to be made between administrators, with full access and control functions for the entire system, and external users, with access limited to specific sections or fields according to their role. Another feature considered particularly strategic is the possibility of geolocating and interactively reporting areas of deterioration directly on the 3D model of the asset, using digital graphic pens.

Alongside these prospective developments, a significant effort—though not supported by additional funding—was devoted to a feasibility study on the integration of external data sources. The study focused on the design of a cloud-based system for the collection, processing, and visualisation of meteorological and pollution data, drawing on open services such as the ARPA Piemonte REST API for meteorological data [51], as well as on monitoring stations already operating in the areas surrounding the Fréjus monument–fountain. The automatic acquisition of such data would make it possible to correlate environmental factors with deterioration phenomena, support risk forecasting, and inform the planning of maintenance interventions.

Several research initiatives and prototype systems have emerged in recent years, exploring diverse approaches to the digital documentation, monitoring, and management of cultural heritage. Taken together, these experiences highlight a common need across the sector: the development of integrated environments capable of bringing together different types of data—from 3D models and diagnostic surveys to maintenance records and intervention histories—within a single interoperable hub. The Fountains and Monuments platform was conceived precisely in response to this need, aiming to provide a unified digital space that supports both the documentation and the long-term management of outdoor heritage assets. At the Italian level, projects such as SACHER–Smart Architecture for Cultural Heritage in Emilia Romagna have developed open-source cloud platforms integrating 3D models and georeferenced data for documentation and maintenance purposes, tested on several monuments in Bologna [52]. Similarly, the Visivalab platform for Pompeii, developed with the University of Salerno, focused on real-time condition monitoring of the archaeological site, offering a powerful but site-specific digital tool [53]. IN-HERITAGE, tested on the Rolli Palaces in Genoa, introduced digital twins and IoT-based monitoring but remains at a prototype stage [54], while ChemiNova (Horizon Europe, 2024–2027) explores AI-driven documentation and environmental diagnostics across multiple European heritage sites [55].

Compared to these examples, Fountains and Monuments distinguishes itself by explicitly combining preventive conservation methodology, data management, and workflow planning within a unified system tailored both to the specific features of outdoor monuments and fountains and to the operational needs of professionals engaged in on-site inspections and maintenance planning. It integrates heterogeneous data sources—including GIS-based information, condition reports, and photographic documentation—and supports both monitoring and the operational scheduling of maintenance activities through an intuitive web-based interface. Moreover, its local micro-hub model, built on collaboration between research bodies, private non-profit institutions, and public administrations, demonstrates a practical approach to bridging the gap between scientific research and governance. This makes the platform transferable, scalable, and aligned with the principles of sustainable heritage management promoted by the European Framework for Action on Cultural Heritage (2018) and subsequent European Commission guidelines. By positioning itself between applied research and operational management, Fountains and Monuments aims to contribute to demonstrating the relevance and effectiveness of digital technologies in supporting evidence-based decision-making for the conservation and management of public heritage.

5. Conclusions

The Fountains and Monuments project constitutes a multi-level experiment for the working group: for the collaborative model between different types of organisations, for in-depth methodological studies in the field of preventive and planned conservation applied to specific case studies, and for the research and development in the field of technology, which included design, scouting for innovative solutions, and technology transfer. The project has demonstrated that the integration of conservation science, digital technologies, and institutional collaboration can generate concrete and scalable outcomes.

From a methodological perspective, the project has produced a Protocol for planned conservation that systematises inspections, risk assessment, and maintenance scheduling, providing a transferable framework applicable to a variety of outdoor heritage assets. From a technological perspective, the digital platform developed as a prototype has shown the feasibility of integrating geospatial databases, 3D models, interactive dashboards, and survey modules into a single operational environment. This approach enables traceability, prioritisation of interventions, and long-term archiving of conservation data, offering a valuable resource for decision-making by heritage authorities.

While still in the demonstrator phase, the platform and the methodology underpinning it have already opened promising perspectives for future development, including interoperability and integration with external environmental data sources, and the implementation of multi-user, multi-level management systems. These elements, together with the evaluation of potential spin-offs, indicate possible pathways for the transition from research to technological transfer.

In conclusion, Fountains and Monuments illustrates how collaborative approaches, preventive methodologies, and digital tools can converge to strengthen the systematic management of outdoor cultural heritage. It represents not only a pilot experience, but also a replicable model that can inform similar initiatives in other contexts, contributing to the debate on the shift from emergency restoration to preventive and planned conservation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.B., M.C., L.F., P.M., and V.V.; Methodology, M.C., P.M., and V.V.; Software, V.V.; Validation, F.B. and L.F.; Investigation, M.C., P.M., and V.V.; Resources, M.C. and P.M.; Data Curation, V.V.; Visualization, V.V.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, F.B.; Writing—Review & Editing, F.B.; Supervision, F.B. and L.F.; Project Administration, F.B.; Funding Acquisition, F.B. and L.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The project is funded by the European Union—NextGenerationEU under the National Recovery and Resilience Plan (NRRP)—Mission 4 Education and research—Component 2 From research to business—Investment 1.3, Notice D.D. 341 of 15/03/2022, entitled: Cultural Heritage Active Innovation for Sustainable Society, proposal code PE 00000020 CHANGES, - CUP B13D22001240004, duration until 28 February 2026.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| NRRP | National Recovery and Resilience Plan |

Notes

| 1 | A key reference is the XV Triennial Conference of ICOM-CC, held in September 2008 in New Delhi, for its attempt to standardize internationally the terminology used to describe actions and measures applied to the conservation of cultural heritage, as well as for its aim to highlight the theoretical and practical differences that characterize the complex activities involved in conservation: Terminology to Characterize the Conservation of Tangible Cultural Heritage. Please see ref [1]. |

| 2 | Equally significant is the more recent European project EPICO dedicated to the development of a simple and flexible methodology for the development of a preventive conservation strategy for the collections exhibited in historic homes and museum residences in Europe. Please see ref [6]. |

| 3 | To confirm the integration of research and activities between Fondazione 1563 and Fondazione Compagnia di San Paolo, see the project: ChiesTO. Chiese del Centro Storico di Torino (Churches in the Historic Centre of Turin), ref. [31] |

| 4 | Fondazione Compagnia di San Paolo has always devoted considerable effort and resources to restoration projects. Its most recent activities are increasingly focused focused on preventive and planned conservation, systemic management and scale, as exemplified by the project: PRIMA. Prevenzione Ricerca Indagine Manutenzione Ascolto per il Patrimonio Culturale (Prevention, Research, Investigation, Maintenance and Listening for Cultural Heritage). Launched in December 2020, ref [33] |

| 5 | Call for tender for the presentation of intervention proposals for the Creation of Enlarged Partnerships extended to Universities, Research Centres, Enterprises and funding basic research projects to be funded under the National Recovery and Resilience Plan (NRRP), Mission 4, Component 2, Investment 1.3, funded from the European Union—NextGenerationEU, Annex 1—Project proposal, pp. 65–66. |

| 6 | The data on typology, exposure, materials, and conservation state of the selected monuments are derived from direct field inspections and condition assessments carried out by CCR research team in 2023. |

| 7 | The figures included in the article are screenshots taken directly from the digital platform developed within the project. As such, theontend elements (labels, buttons, captions) appear in Italian, which is the original working language of the prototype. These cannot be translated without altering the integrity of the screenshots. |

| 8 | See note 7 above. |

References

- Terminology to Characterize the Conservation of Tangible Cultural Heritage. 2008. Available online: https://www.icom-cc.org/en/terminology-for-conservation (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Heinemann, H.; Naldini, S. The role of Monumentenwacht: 40 years theory and practice in The Netherlands. In Innovative Built Heritage Models. Edited Contributions to the International Conference on Innovative Built Heritage Models and Preventive System; van Balen, K., Vandesande, A., Eds.; CRC Press/Balkema—; Taylor & Francis Group: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, M.; van Laar, B. The Monumentenwacht model for preventive conservation of built heritage: A case study of Monumentenwacht Vlaanderen in Belgium. Front. Archit. Res. 2021, 10, 92–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Della Torre, S. Italian perspective on the planned preventive conservation of architectural heritage. Front. Archit. Res. 2021, 10, 108–116. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2095263520300571 (accessed on 3 November 2025). [CrossRef]

- Perles, A.; Fuster-López, L.; Bosco, E. Preventive conservation, predictive analysis and environmental monitoring. Herit. Sci. 2024, 12, 11. Available online: https://www.nature.com/articles/s40494-023-01118-9 (accessed on 3 November 2025). [CrossRef]

- Forleo, D.; De Blasi, S.; Francaviglia, N.; Pawlak, A. EPICO—European Protocol in Preventive Conservation. Methods for conservation assessment of collections in historic houses. Cronache 2017, 7. (In Italian/French/English/Polish). [Google Scholar]

- European Commission: Directorate-General for Education, Youth, Sport and Culture. European Framework for Action on Cultural Heritage; Publications Office: Bruxelles, Belgium, 2019; Available online: https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2766/949707 (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- World Heritage Centre. Policy Document for the Integration of a Sustainable Development Perspective into the Processes of the World Heritage Convention; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2015; Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/documents/138856 (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Cultural Heritage Counts for Europe (CHCFE). Available online: https://www.europanostra.org/our-work/policy/cultural-heritage-counts-europe/ (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Accardo, G.; Altieri, A.; Cacace, C.; Giani, E.; Giovagnoli, A. Risk Map: A project to aid decision-making in the protection, preservation and conservation of Italian cultural heritage. In Conservation Science 2002: Papers from the Conference Held in Edinburgh, Scotland, 22–24 May 2002; Townsend, J.H., Eremin, K., Adriaens, A., Eds.; Archetype Publications: London, UK, 2003; pp. 44–49. [Google Scholar]

- Michalski, S.; Pedersoli, J.L., Jr. The ABC Method: A Risk Management Approach to the Preservation of Cultural Heritage; Government of Canada; Canadian Conservation Institute; ICCROM: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2017; Available online: https://www.iccrom.org/publication/abc-method-risk-management-approach-preservation-cultural-heritage (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Report of the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee, and the Committee of the Regions on the Implementation, Results, and Overall Evaluation of the European Year of Cultural Heritage. (COM(2019) 548 Final). 2018. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/IT/TXT/HTML/?uri=CELEX:52019DC0548&from=EN%3E,%2017.09.2020 (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Horizon 2020. Available online: https://research-and-innovation.ec.europa.eu/funding/funding-opportunities/funding-programmes-and-open-calls/horizon-2020_en (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Joint Programming Initiative on Cultural Heritage and Global Change. Available online: https://www.heritageresearch-hub.eu/joint-programming-initiative-on-cultural-heritage-homepage/ (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Biscontin, G., Driussi, G., Eds.; Pensare la prevenzione. Manufatti, usi, ambienti. In Proceedings of the Atti del XXVI Convegno Internazionale Scienza e Beni Culturali, Bressanone, Italy, 13–16 July 2010; Arcadia Ricerche: Venezia, Italy, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Della Torre, S. Oltre il restauro, oltre la manutenzione. In La Strategia della Conservazione Programmata. Dalla Progettazione Delle Attività alla Valutazione degli Impatti; Nardini: Firenze, Italy, 2014; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Abbondanza, L.; La Monica, D. (Eds.) Giovanni Urbani e la Conservazione Programmata dei Beni Culturali. Storia e Attualità; Felici Editore: Pisa, Italy, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Della Torre, S. La conservazione programmata. In Fondazione e Beni Ecclesiastici di Interesse Culturale. Sfide, Esperienze, Strumenti; Dania, V., Gazzerro, L., Eds.; Il Mulino: Bologna, Italy, 2023; pp. 231–239. [Google Scholar]

- Driussi, G.; Morabito, Z. (Eds.) La Conservazione preventiva e programmata. Venti anni dopo il Codice dei Beni Culturali. In Proceedings of the Atti del XXXIX Convegno Internazionale Scienza e Beni Culturali, Bressanone, Italy, 2–5 July 2024; Arcadia Ricerche: Venezia, Italy, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Staniforth, S. (Ed.) Historical Perspectives on Preventive Conservation; Getty Conservation Institute: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Vandesande, A.; Verstringe, E.; Van Balen, K. (Eds.) Preventive Conservation—From Climate and Damage Monitoring to a Systemic and Integrated Approach; CRC Press: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Moioli, R.A.; Baldioli, R. (Eds.) Conoscere per Conservare. Dieci Anni per la Conservazione Programmata; Quaderni dell’Osservatorio, n. 29; Fondazione Cariplo: Milano, Italy, 2018; Available online: https://www.fondazionecariplo.it/it/strategia/osservatorio/quaderni/conoscere_per_conservare.html (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Legislative Decree 42/2004, Code of the Cultural and Landscape Heritage, Part Two—Cultural Property; Title I—Protection; Chapter III—Protection and Conservation; Section II—Conservation Measures; Article 29, Conservation, Paragraph 1: The Conservation of the Cultural Heritage is Ensured by Means of a Consistent, Co-Ordinated and Programmed Activity of Study, Prevention, Maintenance and Restoration. Available online: https://www.normattiva.it/uri-res/N2Ls?urn:nir:stato:decreto.legislativo:2004-01-22;42!vig= (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- Agency for Digital Italy (AgID); Department for Digital Transformation. Three-Year Plan for Information Technology in Public Administration 2024–2026; Presidency of the Council of Ministers: Rome, Italy, 2024; Available online: https://pianotriennale-ict.italia.it/ (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- European Commission. 2030 Digital Compass: The European Way for the Digital Decade (COM(2021) 118 Final); European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2021; Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A52021DC0118 (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- European Parliament & Council of the European Union. Regulation (EU) 2021/694 Establishing the Digital Europe Programme (2021–2027); L 166; European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 2021; pp. 1–34. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A32021R0694 (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Fondazione CHANGES. Available online: https://www.fondazionechanges.org/en/ (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Fondazione 15563 per l’Arte e la Cultura. Available online: https://www.fondazione1563.it/ (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Barberis, W.; Cantaluppi, A. (Eds.) La Compagnia di San Paolo; Giulio Einaudi Editore: Torino, Italy, 2013; Available online: https://www.fondazione1563.it/progetti/la-compagnia-di-san-paolo-einaudi/ (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Raviola, B.A. La Compagnia di San Paolo (1563–2020). Turin, Europa; Il Mulino: Bologna, Italy, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- ChiesTO. Chiese del Centro Storico di Torino (Churches in the Historic Centre of Turin). Available online: https://programmabarocco.fondazione1563.it/studi-sul-barocco/chiese-del-centro-di-torino (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Bocasso, F.; Cardinali, M.; De Lucia, G.; Fornara, L.; Longhi, A. Il patrimonio urbano di interesse religioso: Da sistema ridondante a risorsa pianificata. Il Capitale Cult. 2024, 29, 17–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PRIMA. Prevenzione Ricerca Indagine Manutenzione Ascolto per il Patrimonio Culturale (Prevention, Research, Investigation, Maintenance and Listening for Cultural Heritage).Launched in December 2020. Available online: https://www.compagniadisanpaolo.it/it/progetti/prima-prevenzione-ricerca-indagine-manutenzione-ascolto-per-il-patrimonio-culturale/ (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Fondazione Centro Conservazione e Restauro “La Venaria Reale” (CCR). Available online: https://www.centrorestaurovenaria.it/ (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Fondazione LINKS. Available online: https://linksfoundation.com/ (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Ithaca, S.r.l. Available online: https://ithaca.earth/ (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Cremona, I. (Ed.) Fantasmi di Bronzo: Guida ai Monumenti di Torino 1808–1937; Martano Editore: Torino, Italy, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- De Micheli, M. La Scultura dell’Ottocento; UTET: Torino, Italy, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Antonetto, R. Fréjus. Memorie di un Monumento; Umberto Allemandi & Co.: Torino, Italy, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Dipartimento Casa Città, Politecnico di Torino. (Ed.) Beni Culturali Ambientali nel Comune di Torino; Società degli Ingegneri e degli Architetti in Torino: Torino, Italy, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Brandoni, A.; Massara, G.G.; Lodi, G.A.; Sincero, V. (Eds) Cittadini di Pietra: La Storia di Torino Riletta nei suoi Monumenti; Comune di Torino: Torino, Italy, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Firpo, L. Torino: Ritratto di una Città, 3rd ed.; Tipografia Torinese: Torino, Italy, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- De Fusco, R. L’architettura dell’Ottocento; UTET: Torino, Italy, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Corgnati, M.; Mellini, G.; Poli, F. (Eds.) Il Lauro e il Bronzo: La Scultura Celebrativa in Italia, 1800–1900; Ilte: Moncalieri, Italy, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Novelli, F.; Piccoli, E. (Eds.) Santa Chiara a Torino. Conservare un Convento nel XXI Secolo; Sagep Editori: Genova, Italy, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- De Micheli, M. La Scultura del Novecento; UTET: Torino, Italy, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Legislative Decree 42/2004, Code of the Cultural and Landscape Heritage, Part Two—Cultural Property; Title I—Protection; Chapter I—Oject of Protection; Articles 10, 12, 13. Chapter III—Protection and Conservation; Section III—Other Forms of Protection; Article 45. Available online: https://www.normattiva.it/uri-res/N2Ls?urn:nir:stato:decreto.legislativo:2004-01-22;42!vig= (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- EN 15898:2019; Conservation of Cultural Heritage—Main General Terms and Definitions. European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2019.

- CEN/TS 17135:2020; Conservation of Cultural Heritage—General Terms for Describing the Alterations of Objects. European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2020.

- Ottaviano conservazione e restauro. Torino-P.zza Statuto, Monumento al Traforo del Frejus: Relazione finale del restauro condotto su gamba del Titano, relativo la riproposizione dell’elemento scultoreo in fibra di vetro e la sua ricollocazione in loco. 12 January 2022.

- Meteorological and Environmental Data are Available on the ARPA Piemonte (Agenzia Regionale per la Protezione Ambientale del Piemonte—Regional Environmental Protection Agency) Open Data Platform, Accessible Through REST API Services. Available online: https://www.arpa.piemonte.it (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Apollonio, F.I.; Rizzo, F.; Bertacchi, S.; Dall’Osso, G.; Corbelli, A.; Grana, C. SACHER—Smart Architecture for Cultural Heritage in Emilia Romagna: A Cloud Platform and Integrated Services for Cultural Heritage. In Digital Libraries and Archives. IRCDL 2017 (Communications in Computer and Information Science, Vol. 733); Grana, C., Baraldi, L., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 142–156. [Google Scholar]

- Visivalab. Available online: https://visivalab.com/en/portfolio-item/sistema-monitoraggio-pompeii-2/ (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- IN-HERITAGE: The Platform for the Future of Cultural Heritage Conservation. Available online: https://www.rolliestradenuove.it/progetti/in-heritag/ (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- ChemiNova. Novel Technologies for On-Site and Remote Collaborative Enriched Monitoring to Detect Structural and Chemical Damages in Cultural Heritage Assets; Horizon Europe, Grant Agreement 101132442: EU, 2024; Available online: https://cheminova.eu/ (accessed on 3 November 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).