Acoustic Characteristics and Influencing Mechanisms of the Traditional Ancestral Temple Theatre in Northeast Jiangxi

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Site Research and Architectural Surveying

2.3. Acoustic Parameter Measurement

2.4. Model Construction and Calibration

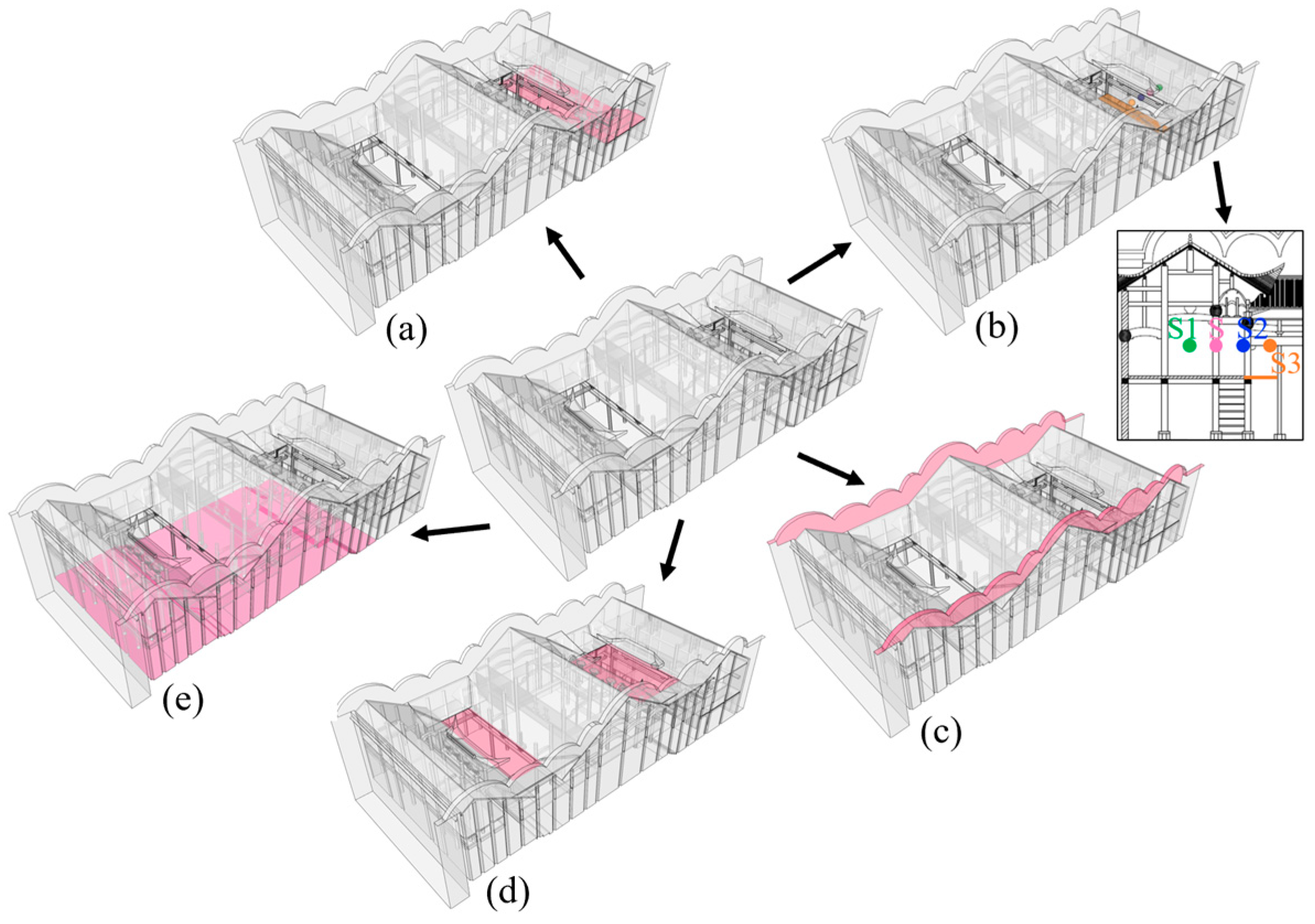

2.5. Simulation Experiment Setup

3. Results

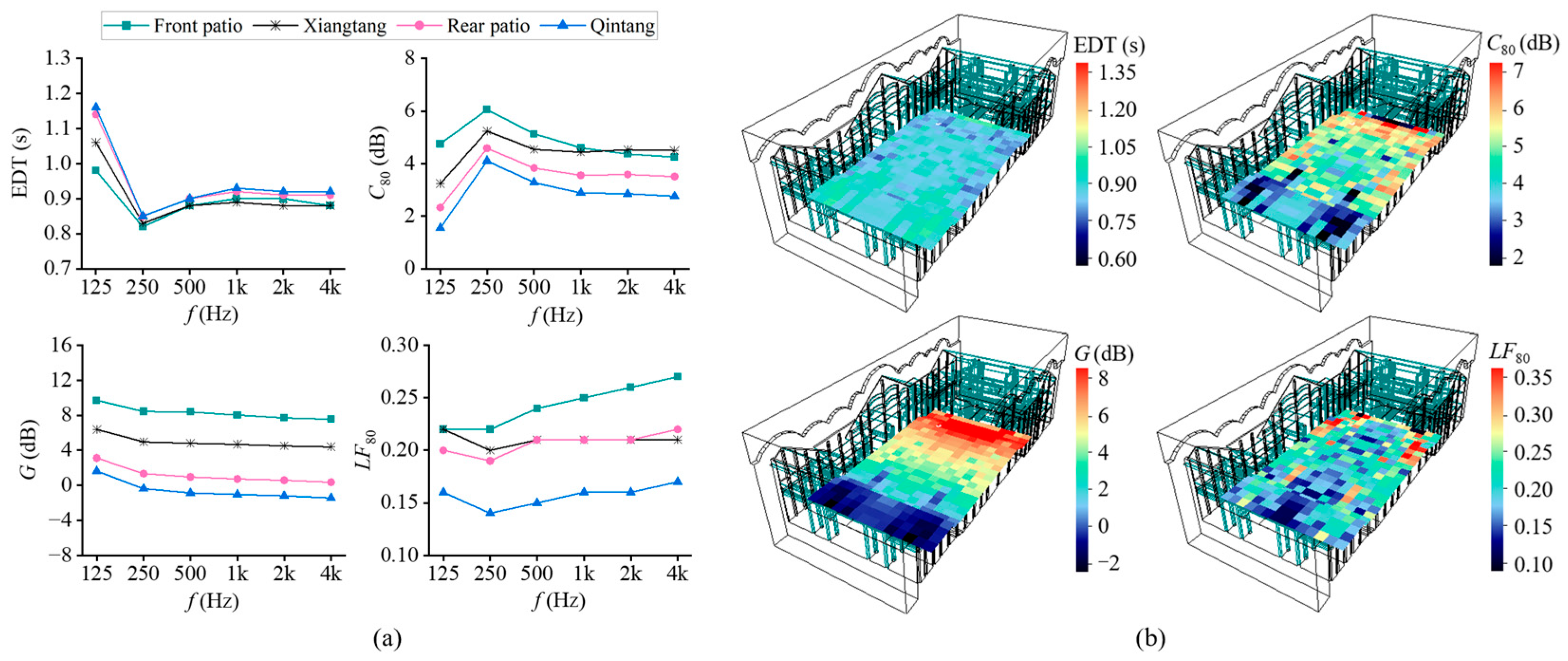

3.1. Current Acoustic Characteristics of the Zhaomutang

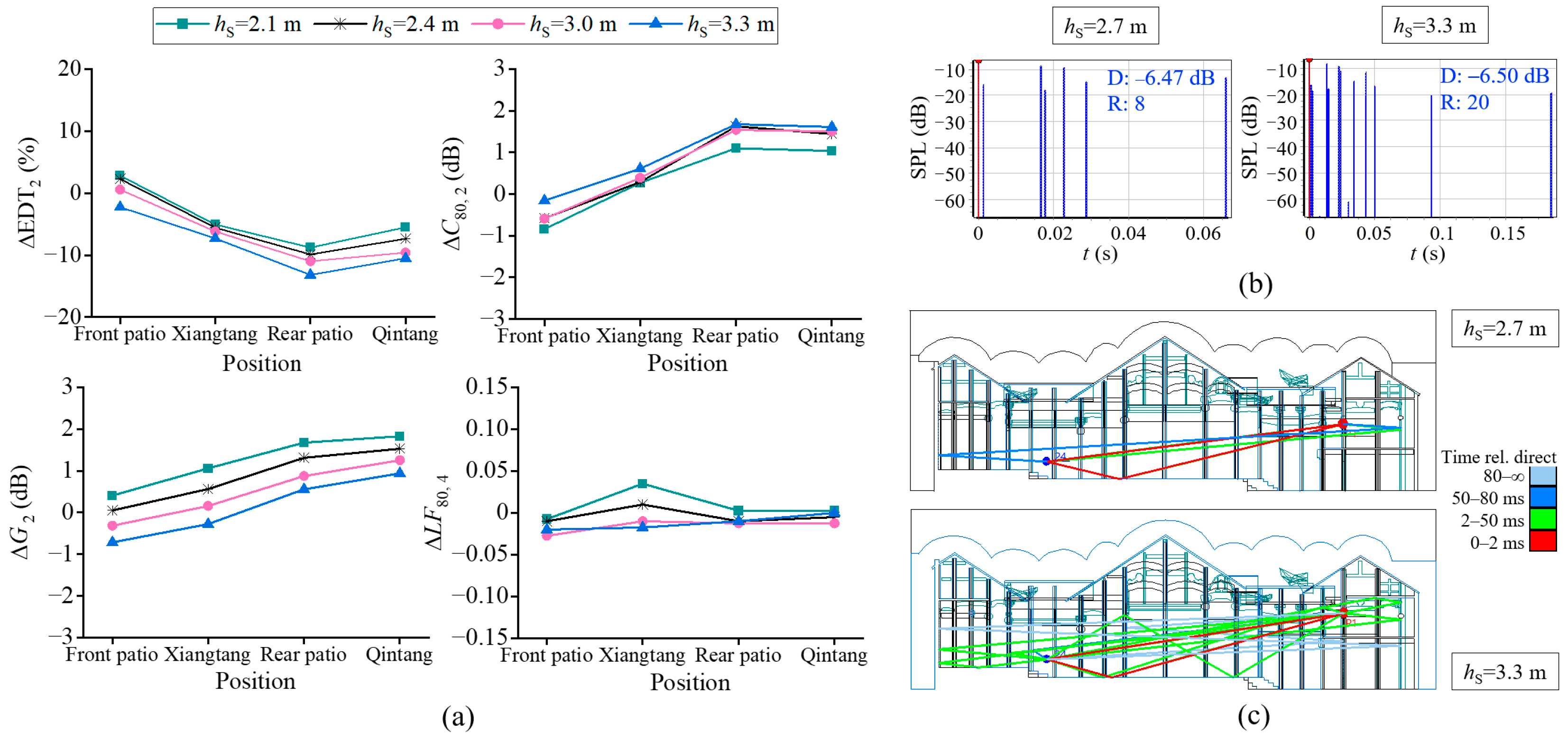

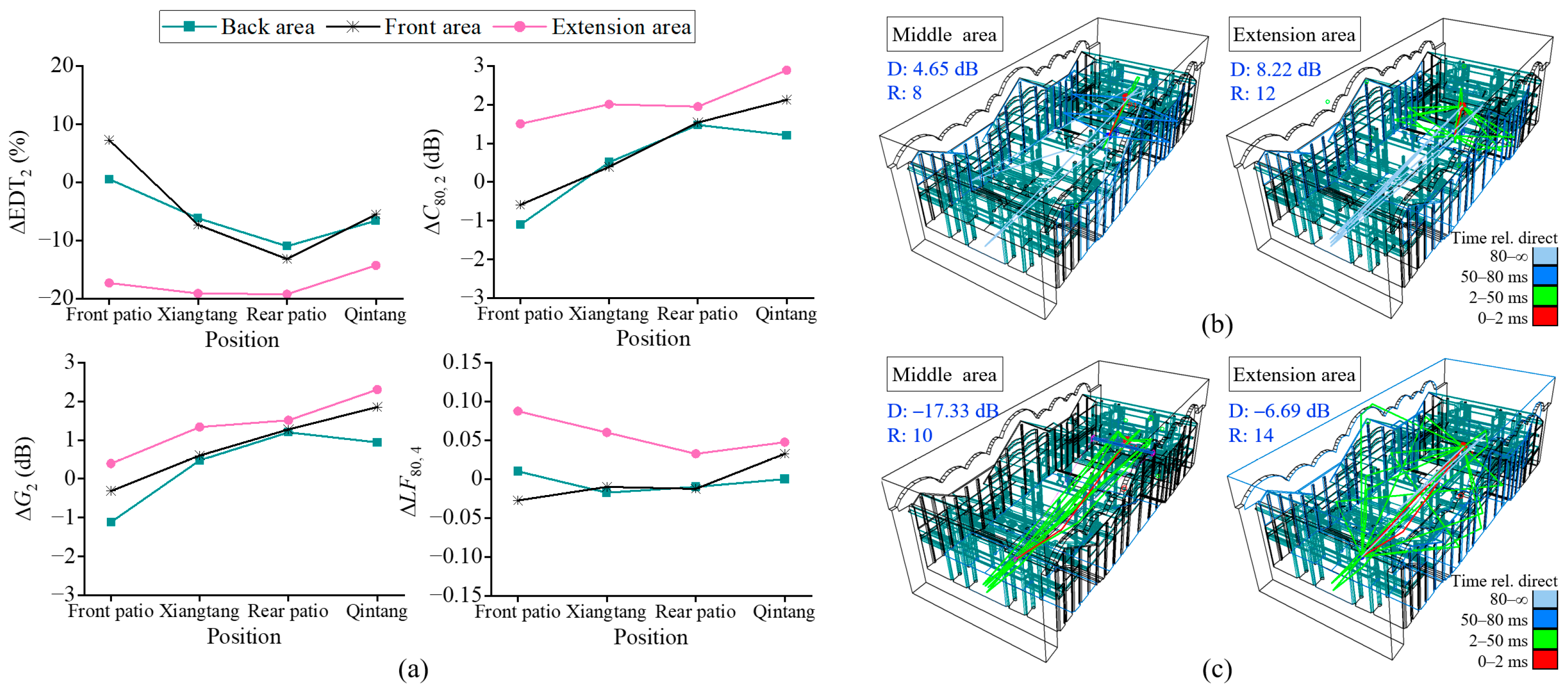

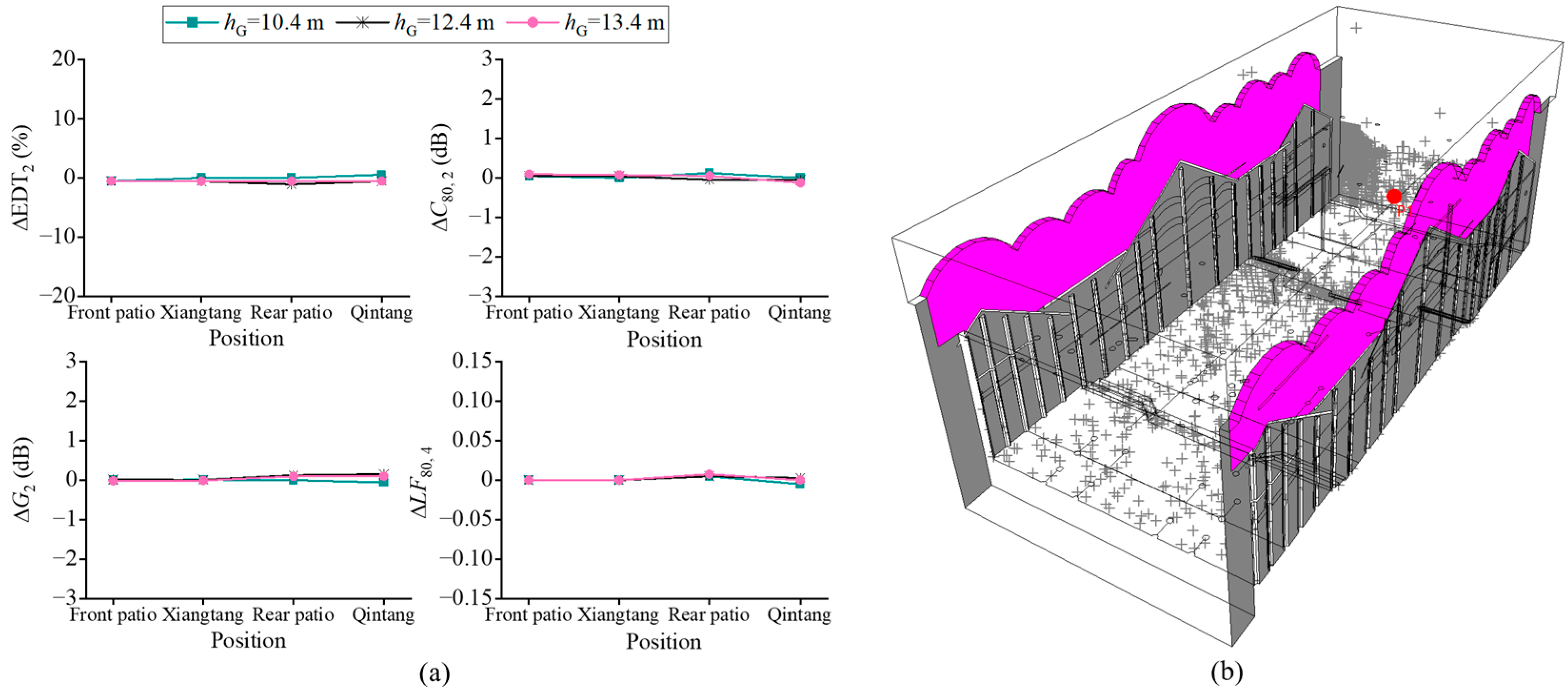

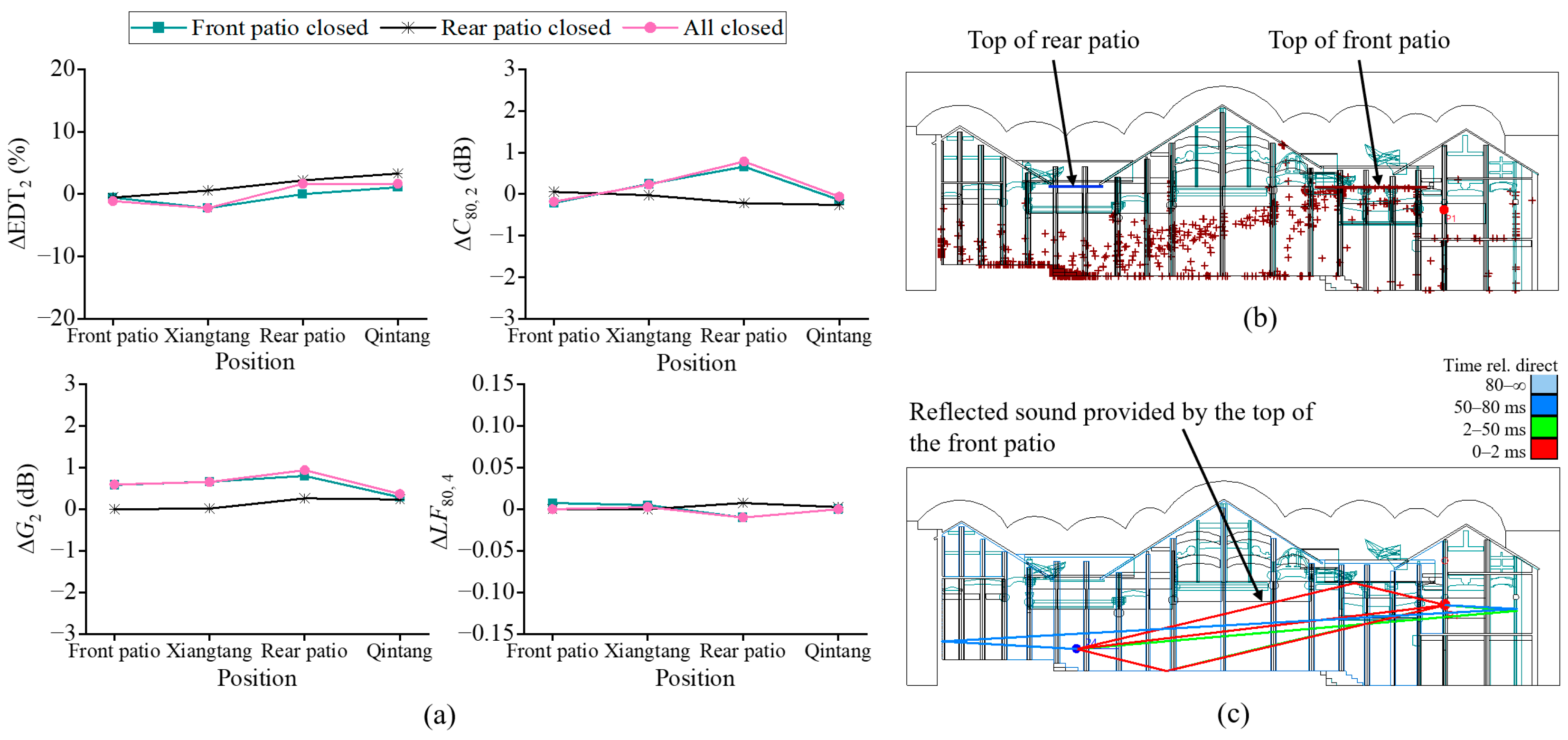

3.2. Effect of Spatial Elements on Theatre Acoustics

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Receiving Point | EDT (s) | C80 (dB) | G (dB) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 500 Hz | 1k Hz | 500 Hz | 1k Hz | 500 Hz | 1k Hz | |

| F1 | 1.0 | 1.1 | 1.3 | 1.7 | 7.1 | 6.6 |

| F2 | 1.0 | 1.1 | 0.0 | 0.5 | 6.7 | 6.2 |

| F3 | 1.1 | 1.1 | −0.5 | 0.0 | 6.8 | 6.2 |

| F4 | 1.0 | 1.1 | −0.3 | 0.1 | 6.9 | 6.4 |

| F5 | 1.0 | 1.1 | 4.2 | 4.7 | 9.4 | 9.0 |

| F6 | 1.0 | 1.1 | 4.6 | 5.1 | 9.9 | 9.5 |

| F7 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 4.5 | 5.0 | 10.0 | 9.7 |

| F8 | 1.0 | 1.1 | 4.6 | 5.0 | 10.1 | 9.7 |

| X1 | 1.0 | 1.1 | 3.4 | 4.0 | 8.2 | 7.8 |

| X2 | 1.0 | 1.1 | 3.4 | 3.9 | 8.3 | 7.8 |

| X3 | 1.0 | 1.1 | 3.0 | 3.6 | 8.3 | 7.8 |

| X4 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 2.8 | 3.3 | 8.1 | 7.5 |

| X5 | 1.0 | 1.1 | 2.9 | 3.4 | 7.4 | 6.8 |

| X6 | 1.0 | 1.1 | −0.1 | 0.3 | 5.7 | 5.0 |

| X7 | 1.0 | 1.1 | 3.3 | 3.9 | 7.9 | 7.3 |

| X8 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 2.0 | 2.6 | 7.0 | 6.4 |

| X9 | 1.0 | 1.1 | 2.6 | 3.2 | 6.5 | 5.9 |

| X10 | 1.0 | 1.1 | 2.2 | 2.7 | 6.3 | 5.7 |

| X11 | 1.0 | 1.1 | 2.7 | 3.2 | 6.7 | 6.1 |

| X12 | 1.0 | 1.1 | 1.6 | 2.2 | 6.0 | 5.3 |

| R1 | 1.0 | 1.1 | 1.5 | 2.0 | 4.6 | 3.8 |

| R2 | 1.0 | 1.1 | 0.2 | 0.5 | 3.7 | 2.9 |

| R3 | 1.0 | 1.1 | 2.0 | 2.6 | 4.9 | 4.2 |

| R4 | 1.0 | 1.1 | 2.4 | 2.9 | 5.2 | 4.6 |

| Q1 | 1.0 | 1.1 | 0.5 | 1.0 | 3.3 | 2.4 |

| Q2 | 1.0 | 1.1 | 0.2 | 0.5 | 3.2 | 2.3 |

| Q3 | 1.0 | 1.1 | 1.0 | 1.5 | 3.8 | 3.1 |

| Q4 | 1.0 | 1.1 | 1.2 | 1.6 | 3.9 | 3.1 |

References

- Hu, Q.; Yang, P.; Ma, J.; Wang, M.; He, X. The Spatial Differentiation Characteristics and Influencing Mechanisms of Intangible Cultural Heritage in China. Heliyon 2024, 10, e38689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, J.; Kang, J.; Ma, H.; Wang, C. Grounded Theory-Based Subjective Evaluation of Traditional Chinese Performance Buildings. Appl. Acoust. 2020, 168, 107417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J. A Discussion on Strategies for Protecting and Inheriting Traditional Construction Skills of Leping Ancient Stage. Sichuan Drama 2020, 1, 155–157. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, J.; Zhang, X. The Study of Leping Ancient Stage from the Perspective of Folk Belief. Art Des. 2015, 1, 83–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, W.; Ma, K.; Liu, J.; Wang, X.; Leng, H. Acoustic adaptation mechanism of a traditional ancestral temple theatre in northeast Jiangxi. NPJ Herit. Sci. 2025, 13, 446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, Q. An Analysis of the Band Evolution and Accompanying Characteristics of Tanqu in Gan Opera. Chin. Theatre 2020, 8, 94–96. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, T.; Kuang, L.; Jia, L. Chinese Aesthetic Features of Traditional Costumes in Gan Opera. J. Educ. Humant. Soc. Sci. 2023, 11, 194–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L. Research on Performance Form of Gan Opera and Ancient Stage in Leping. Art Des. 2013, 8, 92–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, R.; Su, C.; Xu, W. Simulation Research on Acoustic Environment of Typical Ancestral Temple Theater with Odeon Software: A Case Study of Wu’s Ancestral Temple in Hong’an County. J. Wuhan Inst. Technol. 2020, 42, 91–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Liu, D.; Wu, S. The Acoustics of the Traditional Theater in South China: The Case of Wanfu Theatre. In Proceedings of the 2011 International Conference on Electric Technology and Civil Engineering, Lushan, China, 22–24 April 2011; pp. 3599–3602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, J.; Wang, T.; Zhang, Z. Research on the Acoustic Environment of Heritage Buildings: A Systematic Review. Buildings 2022, 12, 1963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaleris, K.; Moiragias, G.; Hatziantoniou, P.; Mourjopoulos, J. Time-Frequency Diffraction Acoustic Modeling of the Epidaurus Ancient Theatre. Acta Acust. 2023, 7, 3090–3099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Oberman, T.; Aletta, F. Defining Acoustical Heritage: A Qualitative Approach Based on Expert Interviews. Appl. Acoust. 2024, 216, 109754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bevilacqua, A.; Iannace, G. From Discoveries of 1990s Measurements to Acoustic Simulations of Three Sceneries Carried Out Inside the San Carlo Theatre of Naples. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2023, 154, 66–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Ren, G.; Cheng, F.; Xiao, D.; Zhang, M.; Kang, J. Sound field characteristics and influencing factors of traditional Chinese interlocked timber-arched covered bridges. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2025, 158, 1156–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brian, F.; Cécile, C.; Stéphanie, P.; Julien, D. The Past Has Ears at Notre-Dame: Acoustic digital twins for research and narration. Digit. Appl. Archaeol. Cult. Herit. 2024, 34, e00369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Psarras, S.; Hatziantoniou, P.; Kountouras, M.; Tatlas, N.A.; Mourjopoulos, J.N.; Skarlatos, D. Measurements and Analysis of the Epidaurus Ancient Theatre Acoustics. Acta Acust. United Acust. 2013, 99, 30–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Orazio, D.; De Cesaris, S.; Morandi, F.; Garai, M. The Aesthetics of the Bayreuth Festspielhaus Explained by Means of Acoustic Measurements and Simulations. J. Cult. Herit. 2018, 34, 151–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzarella, L.; Cairoli, M. Petrarca Theatre: A Case Study to Identify the Acoustic Parameters Trends and Their Sensitivity in a Horseshoe Shape Opera House. Appl. Acoust. 2018, 136, 61–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tronchin, L.; Yan, R.; Bevilacqua, A. The Only Architectural Testimony of an 18th Century Italian Gordonia-Style Miniature Theatre: An Acoustic Survey of the Monte Castello di Vibio Theatre. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 2210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Büttner, C.; Yabushita, M.; Parejo, A.S.; Morishita, Y.; Weinzierl, S. The Acoustics of Kabuki Theaters. Acta Acust. United Acust. 2019, 105, 1105–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tronchin, L.; Bevilacqua, A. The Royal Tajo Opera Theatre of Lisbon: From Architecture to Acoustics. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2023, 153, 400–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Aguilar, B.; Quintana-Gallardo, A.; Gasent-Blesa, J.L.; Guillén-Guillamón, I. The Acoustic and Cultural Heritage of the Banda Primitiva de Llíria Theater: Objective and Subjective Evaluation. Buildings 2024, 14, 2329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J. Introduction of Chinese Traditional Theatrical Buildings Part A: History. J. Tongji Univ. Nat. Sci. 2002, 2, 27–34. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Mo, F. Quantitative Analyses of the Acoustic Effect of the Pavilion Stage in Traditional Chinese Theatres. Appl. Acoust. 2013, 32, 290–294. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J. Acoustics of Traditional Chinese Courtyard Theatrical Buildings. Acta Acust. 2015, 40, 317–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, M.; Ma, H.; Yang, J.; Yang, L. Main Acoustic Attributes and Optimal Values of Acoustic Parameters in Peking Opera Theaters. Build. Environ. 2022, 217, 109041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Feng, Y.; Zhang, M.; Kang, J. Sound Field of a Traditional Chinese Palace Courtyard Theatre. Build. Environ. 2023, 230, 109741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Gao, C.; Ding, H. A Preliminary Study on the Classification of Pre-Modern Shanxi Opera Stages Based on Their Acoustic Characteristics. Hist. Stud. Nat. Sci. 2016, 35, 175–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Mao, W.; Zhang, H. Acoustics of Traditional Courtyard Theatre of Yue Opera. Huazhong Archit. 2024, 42, 56–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, F.M.Y. Safeguarding Traditional Theatre Amid Trauma: Career Shock Among Cultural Heritage Professionals in Cantonese Opera. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2022, 28, 1091–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Q.; Zhong, J. The Living Inheritance and Moving Progress of Contemporary Cantonese Opera from the Perspective of Communication. Commun. Humanit. Res. 2023, 17, 52–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, R. Entertainment and Worship Within One Temple: Research on Zhaomu Ancestry Temple with Theatre in Leping, Jiangxi Province. Huazhong Archit. 2016, 34, 174–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leng, H.; Xiong, W.; Zhou, B. The Sound Quality Characteristics of the Gan Opera Ancestral Temple Theater Based on Impulse Response: A Case Study of Zhaomutang in Leping, Jiangxi Province. Buildings 2025, 15, 986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 3382-1:2009; Measurement of Room Acoustic Parameters. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2009.

- Xu, J.; Zhang, X. On the Aesthetic Value of the Ancient Stage in Leping. Art Obs. 2020, 5, 65–66. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, D.; Kong, C.; Zhang, M.; Meng, Q. Courtyard Sound Field Characteristics by Bell Sounds in Han Chinese Buddhist Temples. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S. Architectural Acoustics Design Principles, 2nd ed.; China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Martellotta, F. The Just Noticeable Difference of Center Time and Clarity Index in Large Reverberant Spaces. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2010, 128, 654–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bevilacqua, A.; Fuchs, W. Digital Soundscape of the Roman Theatre of Gubbio: Acoustic Response from Its Original Shape. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 12097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prodi, N.; Pompoli, R.; Martellotta, F.; Sato, S. Acoustics of Italian Historical Opera Houses. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2015, 138, 769–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Subspace | East–West Width (m) | North–South Width (m) | Net Height (m) | Interior Volume (m3) | Elevation (m) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stage | 14.7 | 3.8 | 3.2 | 178.8 | 2.7 |

| Backstage | 14.7 | 1.6 | 3.2 | 93.2 | 2.7 |

| Front patio | 8.7 (6) a | 5.2 | / | / | 0 |

| Xiangtang | 14.7 | 12.5 | 6.2 (9.5) b | 1414.6 | 0.8 |

| Rear patio | 6.2 (8.5) c | 2.7 | / | / | 0.8 |

| Qintang | 14.7 | 6.3 | 4.4 | 407.5 | 1.5 |

| Material | Sound Absorption Coefficient Under the Following Frequencies (Hz) | Scattering Coefficient | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 125 | 250 | 500 | 1k | 2k | 4k | ||

| Clay tile roof | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.50 |

| Ceiling | 0.16 | 0.15 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.40 |

| Beams and columns | 0.10 | 0.07 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.30 |

| Bucket arch | 0.19 | 0.43 | 0.44 | 0.40 | 0.42 | 0.40 | 0.40 |

| Plastering brick wall | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.05 |

| Wooden floor | 0.12 | 0.08 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.10 |

| Wooden door | 0.16 | 0.15 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.10 |

| Brick floor | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.05 |

| Audience | 0.30 | 0.45 | 0.52 | 0.62 | 0.61 | 0.56 | 0.70 |

| Transmission interface | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0 |

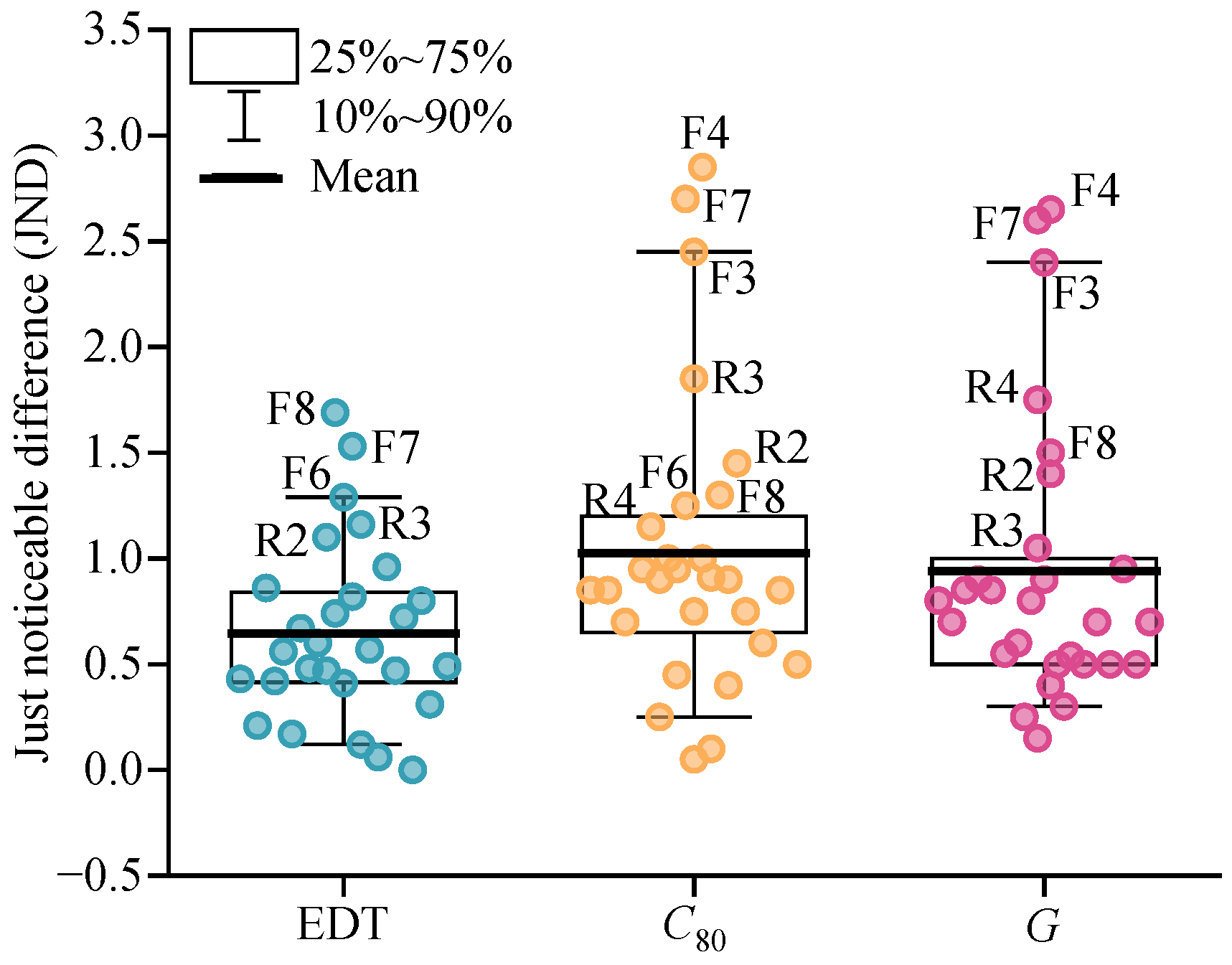

| Acoustic Parameter | JND | Deviation |

|---|---|---|

| EDT2 (500–1k Hz) | 5% | 0.78 JND |

| C80, 2 (500–1k Hz) | 1 dB | 0.13 JND |

| G2 (500–1k Hz) | 1 dB | 0.59 JND |

| LF80, 4 (125–1k Hz) | 0.05 | / |

| Spatial Element | Impact on EDT2 | Impact on C80, 2/G2 | Impact on LF80, 4 | Optimization Priority |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Performer position forward | Significant | Significant | Moderate | High |

| Stage height increase | Medium-High | Medium-High | Slight | High |

| Audience floor elevation | Medium-High | Medium-High | Slight | High |

| Patio covering | Slight | Slight | Slight | Low |

| Gable wall height increase | Slight | Slight | Slight | Low |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xiong, W.; Hu, Z.; Liu, J.; Ma, K.; Lu, Z.; Li, X. Acoustic Characteristics and Influencing Mechanisms of the Traditional Ancestral Temple Theatre in Northeast Jiangxi. Heritage 2025, 8, 515. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8120515

Xiong W, Hu Z, Liu J, Ma K, Lu Z, Li X. Acoustic Characteristics and Influencing Mechanisms of the Traditional Ancestral Temple Theatre in Northeast Jiangxi. Heritage. 2025; 8(12):515. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8120515

Chicago/Turabian StyleXiong, Wei, Ziteng Hu, Jianting Liu, Kai Ma, Zeyu Lu, and Xin Li. 2025. "Acoustic Characteristics and Influencing Mechanisms of the Traditional Ancestral Temple Theatre in Northeast Jiangxi" Heritage 8, no. 12: 515. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8120515

APA StyleXiong, W., Hu, Z., Liu, J., Ma, K., Lu, Z., & Li, X. (2025). Acoustic Characteristics and Influencing Mechanisms of the Traditional Ancestral Temple Theatre in Northeast Jiangxi. Heritage, 8(12), 515. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8120515