Abstract

This paper presents a knowledge-based and interpretative model for the conservation of the House of Arianna, located in the Archaeological Park of Pompeii, developed within the CHANGES project, Spoke 6—History, Conservation and Restoration of Cultural Heritage. The research focused on two critical components of the site: the free-standing peristyle columns and the mosaic and frescoed surfaces preserved in situ. This workflow yielded a high-resolution digital model, analytical condition maps, and diagnostic datasets that directly inform conservation decisions. The results show that the columns exhibit internal discontinuities and weaknesses at their joints, a condition linked to heterogeneous construction techniques which increases the risk of drum slippage under wind and seismic loading. The mosaics display a marked loss of tesserae in exposed sectors over recent years, driven by moisture ingress, biological growth and mechanical stress. These findings support the adoption of low-impact, reversible measures, embedded within a prevention-first strategy based on planned conservation. The study formalizes a replicable methodology that aligns diagnostics, monitoring and conservation planning. By linking ‘skin’ and ‘structure’ within a unified interpretative matrix, the approach enhances both structural safety and material legibility. The workflow proposed here offers transferable guidance for the sustainable preservation and inclusive interpretation of exposed archaeological ensembles in the Vesuvian context and beyond.

1. Introduction

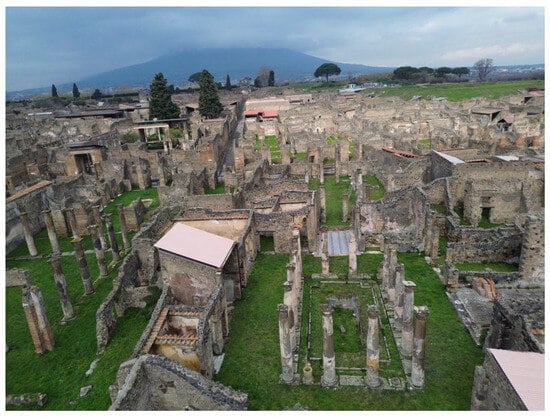

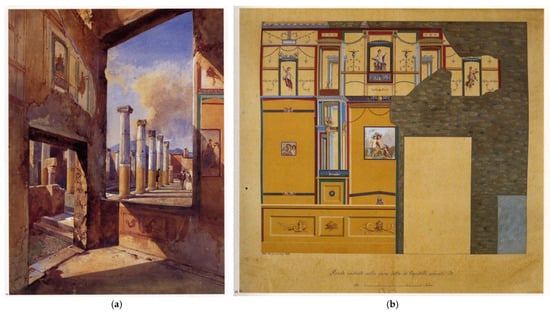

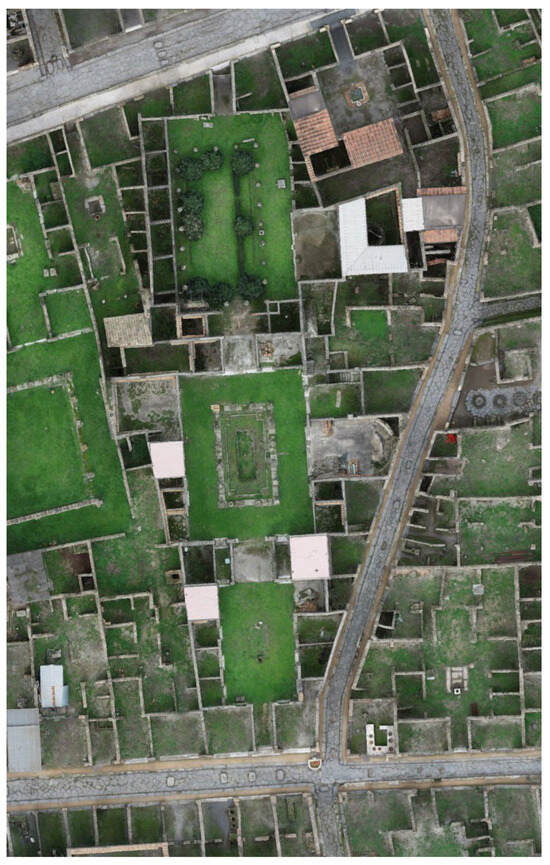

Located in Insula 4 of Regio VII within the Archaeological Park of Pompeii (Figure 1), the House of Arianna—also known as the House of the Colored Capitals—has been identified as a key site of experimentation within the CHANGES (Cultural Heritage Active Innovation for Next Generation Sustainable Society) program, PE5. Humanities and Cultural Heritage as Laboratories of Innovation and Creativity, Spoke 6—History, Conservation and Restoration of Cultural Heritage.

Figure 1.

Archaeological Park of Pompeii, Regio VII, Insula 4. Aerial view (drone photo M. Facchini, 2023). The buildings within Insula 4 are identified as follows: (1) House of Bacco; (2) House of the Clay Moulds; (3) Temple of Fortuna Augusta; (4) House of the Black Wall; (5) House of the Figured Capitals; (6) House of the Grand Duke Michele; (7) House of Arianna; (8) House of the Ancient Hunt.

Continuing the long-standing tradition of studies and interventions promoted by the University of Naples Federico II in the Archaeological Park of Pompeii, the project aims to consolidate a methodology based on the integration of historical and critical analysis, advanced architectural survey and the study of materials and construction techniques to assess the conservation issues affecting the domus [1,2,3]. This integrated approach is directed towards defining methodological guidelines for conservation interventions and for the sustainable and informed management of ancient built heritage. Rather than carrying out conservation works directly, the ultimate objective is to provide the Archaeological Park with a scientifically grounded decision-making tool to support the design and implementation of future conservation projects.

Within the research conducted by the Federico II unit of Spoke 6, conservation is conceived not merely as a technical operation, but as a cognitive and cultural process capable of interpreting the artifact as a complex and stratified document—the result of transformations, reinterpretations and historical sedimentations. In this perspective, the protection of ancient fabric emerges as a systemic challenge, in which the scientific rigor of technical analysis intertwines with the ethical and social responsibility inherent in heritage care. Contemporary conservation must engage with the imperatives of sustainability, accessibility, and participation.

To date, the domus has not been the object of a systematic architectural study explicitly oriented towards conservation and restoration. Over the last decades, international research teams have concentrated on the excavation of significant sectors of the complex and on the analysis of its decorated surfaces, without, however, addressing the house as a unitary organism. From the late 1970s, the domus underwent a campaign of cleaning and comprehensive documentation carried out by an Australian team led by J.-P. Descoeudres (1978–1983), within the framework of the international project Häuser in Pompeji—Pompeian Houses, directed by V. M. Strocka [4,5]. In more recent years, archaeological investigations have continued under Spanish and Austrian teams, which have focused on the state of conservation of selected decorated surfaces, leading, among other outcomes, to the replacement of the protective roofing in some rooms [6,7,8]. Nonetheless, these initiatives have not produced an overarching interpretive framework which, starting from previous restorations, construction techniques, and the current patterns of decay, might guide the future conservation of the complex. The contribution proposed here explicitly seeks to address this gap by advancing an integrated, architecture- and conservation-driven reading of the House of Arianna.

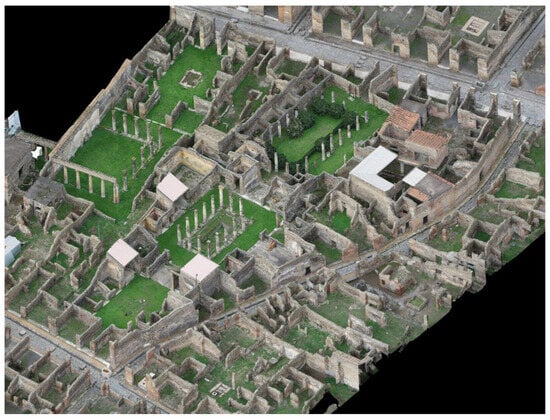

The activities carried out within the CHANGES Spoke 6 project have thus assumed the value of an interdisciplinary laboratory, in which knowledge is translated into an operational tool and technology serves as a critical support to direct observation, enabling a conservation approach grounded in both diagnostic evidence and historical interpretation. The House of Arianna addresses, in a unified manner, the main issues related to the conservation of archaeological built heritage: from the reading of architectural transformations to the analysis of material decay affecting both ancient structures and twentieth-century restorations, and the definition of interventions compatible with the fragility of the site’s material fabric (Figure 2).

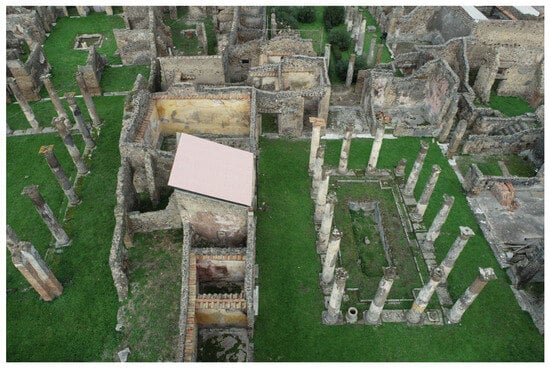

Figure 2.

Pompeii, House of Arianna, VII 4, 31–51. In the aerial view, the distinctive features of the house can be observed, such as the articulation of the peristyles with free-standing columns and the protective restoration roofs covering the decorated surfaces of the exedra and the oecus. These elements distinguish the domus from the surrounding archaeological remains (drone photo M. Facchini, 2023).

The architectural and decorative complexity of the building—combined with its long history of excavations and restorations—has offered the opportunity to develop a methodological model of knowledge and restoration able to preserve value to time and continuity to matter. This model aligns with the founding principles of contemporary architectural restoration, understood as a critical practice of interpretation and transmission of archaeological heritage through the permanence of its material authenticity.

Archaeological Conservation Issues

The research is grounded in long-standing experimental work on archaeological sites and in more recent interdisciplinary studies that frame current restoration practice [9,10,11]. A key step was to systematize the principal conservation issues recurrent in archaeological contexts and to map these categories onto the specific conditions observed in the House of Arianna.

The House of Arianna demonstrated to be easily considered a paradigmatic case study to analyze the conservation issues of the archaeological sites: in fact, the specific forms of degradation we detected on this site are frequent in all the Pompeii archaeological remains. These special traces of the past, often preserved in a fragmentary state, are among the most vulnerable categories of built heritage. Once deprived of their roofs, floors, and upper wall portions, these structures are directly exposed to environmental agents, a condition that inevitably accelerates both surface decay and structural instability. The absence of protective coverings allows humidity, rainfall, wind, and vegetation to act without restraint, eroding masonry, plaster, and decorative finishes over time (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Pompeii, House of Arianna, VII 4, 31–51. Perspective view of the Doric peristyle. The aerial image highlights the conservation issues affecting the domus, including the instability of the free-standing columns and the incompatibility of some earlier restoration materials with the original archaeological fabric (drone photo M. Facchini, 2023).

Within this fragile framework, diagnostic analysis plays a fundamental role in recognizing and mapping deterioration processes that affect both architectural and decorative components, from detached plaster and voids to the spread of biological patinas. Equally essential are monitoring techniques, which provide a means to document how such phenomena evolve over time, turning observation into an ongoing process rather than a one-off assessment.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. The Case Study

Among the most extensive residences in the ancient Vesuvian city, the House of Arianna occupies the full depth of Insula 4 in Regio VII, running north to south over an area of more than 1.850 m2. The building is organized into three main nuclei—atrium tuscanicum, central peristyle and northern peristyle—defining a sequence of spaces of varying function and representativeness, connected by a system of visual and compositional axes of remarkable rigor [6].

The plan of the house reflects an advanced stage of the Pompeian domestic model, marking the transition from the Italic domus of atrial tradition to the Hellenistic house organized around a columned courtyard, where the balance between solids and voids became decisive in shaping the architectural space. The clear tripartite composition—each sector arranged around its central void—corresponds to a distributive logic combining functional autonomy and perceptual unity, achieving equilibrium between the public dimension of reception and the private sphere of domestic life in ancient Pompeii.

Comparable to the nearby House of the Faun and of Epidio Rufo, the House of Arianna represents one of the most accomplished expressions of Pompeian architectural maturity, where the Roman atrium scheme merges with the Greek peristyle, generating a hybrid language of refined formal modernity. The elegance of its spatial sequences, the precision of its construction, and the richness of its pictorial and mosaic decorations—now only partially preserved—convey the image of an aristocratic residence of high rank, reflecting an educated taste attuned to late Republican Mediterranean models [7].

The current state of preservation reveals only fragments of what the building once contained; the loss of most architectural decorations and wall paintings stems largely from the excavation and musealization methods employed at the time of its rediscovery.

2.2. Research Aims and Methodology

The CHANGES project Spoke 6—History, Conservation and Restoration of Cultural Heritage adopts this stratified complex as an emblematic case study to investigate the interplay between knowledge and conservation within archaeological contexts. The research activity, carried out by the Federico II unit in close collaboration with the Archaeological Park of Pompeii, unfolded through a sequence of integrated phases in which historical research, geometric survey, material analysis, and diagnostic monitoring collectively contributed to a multidimensional understanding of the House of Arianna (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Dynamic interpretative model linking knowledge and conservation at the House of Arianna. The model integrates indirect knowledge (archival, bibliographic, and iconographic research), direct knowledge (geometric survey, material and construction analysis, mapping of decay and structural behaviour), and diagnostic investigations. The critical interpretation of these integrated data supports a dynamic and replicable framework for conservation decision-making, in which conservation becomes both an instrument of knowledge and a means of sustainable reactivation of the site. Continuous feedback between investigation, interpretation and intervention allows the model to evolve over time and to be adapted to different archaeological contexts.

The first phase focused on the collection, analysis, and interpretation of archival and bibliographic sources, essential for reconstructing the excavation and restoration history of the domus. This was complemented by an extensive integrated survey campaign employing advanced three-dimensional acquisition technologies—3D laser scanning and drone photogrammetry—through which a high-resolution digital model of the entire complex was generated. The resulting model proved fundamental not only for morphological and structural analysis but also for the management and comparative assessment of conservation data related to ancient structures. Diagnostic investigations targeted the building’s materials, mortars, and decorated surfaces, combining geophysical prospecting, X-ray fluorescence (XRF) spectrometry, digital video microscopy, and pacometric testing. Attention was devoted to the decorated surfaces of the lararium in the Corinthian atrium and to the free-standing columns of the northern peristyle—structurally vulnerable elements whose seismic fragility continues to limit the site’s public accessibility (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Ground-penetrating radar survey conducted by the Federico II research team of CHANGES Spoke 6 to investigate the subsurface beneath the peristyles and atrium of the domus. Analysis conducted by the research unit of University of Naples Federico II: prof. arch. V. Morra, dott. M. Verde (photo E. Fiore, 2024).

The methodological approach adopted by the project is grounded in the principle of active knowledge, according to which diagnosis and assessment of the state of conservation are not preliminary phases but continuous processes that accompany and orient restoration work. In this perspective, the reading of material stratifications, the evaluation of static relationships, and the monitoring of environmental parameters contribute to defining a dynamic and replicable interpretative model—one that evolves over time and adapts to different archaeological contexts while maintaining sustainability and minimal intervention as guiding principles.

The House of Arianna thus serves as a genuine laboratory for methodological experimentation, where restoration operates simultaneously as an instrument of knowledge and as a means of cultural reactivation of the site. The integration of disciplines such as architecture, materials science, petrography, and geophysics enables the construction of a coherent interpretative framework that restores continuity and meaning to the building’s historical transformations, redefining it not merely as an object of protection but as a living, evolving organism shaped by successive historical and constructive layers.

Within this framework, the Pompeian activities of the CHANGES project pursue the definition of an intervention model oriented toward quality and sustainability—one that recognizes reversibility, recognizability, and material compatibility as the cornerstones of a technically informed and culturally conscious conservation practice. The methodological guidelines developed by the research group promote planned and preventive conservation, grounded in the continuous updating of diagnostic data, cyclical monitoring, and the use of environmentally sustainable materials, in accordance with the most advanced standards of sustainable conservation.

Emphasis is placed on inclusive fruition, understood not merely as physical accessibility but as a cognitive and participatory experience that restores to the community the deeper meaning of archaeological heritage. The spatial complexity of the House of Arianna—articulated on multiple levels and distinguished by rooms of exceptional decorative value—calls for reflection on visitor routes and on the need to balance protection with shared knowledge. In this direction, digital humanities and interactive three-dimensional modelling technologies play a crucial role in mediating the relationship between visitors and cultural heritage, enabling expanded, inclusive, and multisensory forms of engagement capable of conveying the site’s spatial and narrative complexity, even remotely (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Pompeii, House of Arianna, VII 4, 31–51. Model of the insula 4.

The experience of the House of Arianna within the CHANGES project aims to construct a replicable model for the conservation and management of the Vesuvian archaeological heritage, based on the integration of stratigraphic knowledge, diagnostic investigation, and conservation choices. This experimentation demonstrates how conservation can constitute both a scientifically grounded and socially relevant process—one oriented toward the creation of a heritage community in accordance with the principles of the Faro Convention, where the care of antiquity becomes an act of shared responsibility.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Analysis and Results from Iconographic Research and Documentary Sources on the Domus

Building on prior studies of the House of Arianna, the research carried out within the CHANGES project approached the domus as a layered architectural palimpsest. To that end, historical and iconographic research were used as tools to decipher and interpret the processes of evolution, rediscovery, and restoration that have shaped the domus’ archaeological structures over time. The first explorations of Regio VII date to 1833, during the directorship of Francesco Maria Avellino, who initiated systematic excavation of this area, progressively uncovering Insulae 3 and 4. Between 1833 and 1837 the main houses of the block were brought to light, including the House of the Ancient Hunt (VII 4, 48), the House of the Black Wall (VII 4, 59), the House of the Figured Capitals (VII 4, 57), and the House of Arianna (VII 4, 31–51) [12].

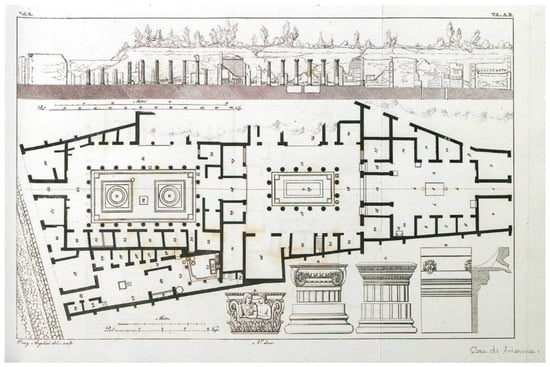

The principal sources documenting this intense activity are the excavation journals preserved in the State Archives and in the Archives of the National Archaeological Museum of Naples. A key reference for understanding the house is Guglielmo Bechi’s Report on the Excavations of Pompeii (1833–1834), accompanied by two plates that constitute one of the earliest graphic representations of the building and show the eastern walls still buried beneath the layer of lapilli [13] (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

G. Bechi, The House of Arianna, plates A–B accompanying the “Report on the Excavations of Pompeii from April 1833 to February 1834,” in Real Museo Borbonico, vol. X, p. 1, 1833. The drawing constitutes the first official survey of the building, as evidenced by the depiction of the excavation sediments still covering the structures.

The excavation records attest to the extraordinary quality of the wall paintings, especially the famous fresco depicting Arianna abandoned by Theseus on Naxos—from which the domus takes its name—removed by the bourbon excavators and now displayed in the Naples National Archaeological Museum. Because of its architectural distinction and the quality of its decorations, the House of Arianna was among the most thoroughly documented buildings of the nineteenth century (Figure 8). This was largely thanks to the architect Pietro Bianchi, then director of the Pompeii site, who intensified the practice of drawing and recording architectural remains during excavation. In accordance with the Bourbon regulations in force at the time [14,15], Bianchi coordinated a group of official draftsmen assigned to record mosaics, objects and paintings unearthed daily—among them Giuseppe Marsigli, Giuseppe Abbate, Nicola La Volpe, Michele and Serafino Mastracchio, and from 1842 Antonio Ala—whose works often provide the only surviving evidence of decorations later lost in the second half of the nineteenth century [4].

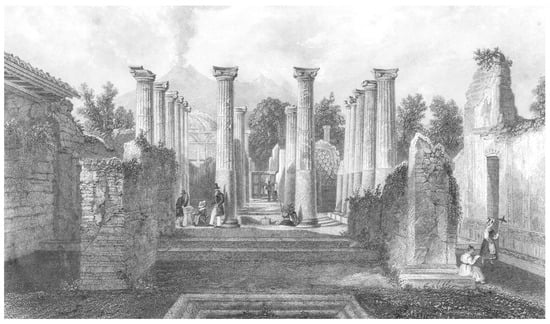

Figure 8.

J.B. Allen, Lithograph of the House of Arianna, 1850. The lithograph highlights the state of preservation of the structures in the Tuscan atrium and the central peristyle: the wall crests appear heavily affected by invasive vegetation, in contrast to the free-standing columns of the central peristyle, which are depicted as being in an excellent state of preservation.

In addition to the official draftsmen, the fame of the House of Arianna attracted numerous independent artists, including Giuseppe Mancinelli, Wilhelm Zahn, and Anton Theodor Eggers, whose works helped disseminate the image of Pompeii throughout European artistic and collecting circles.

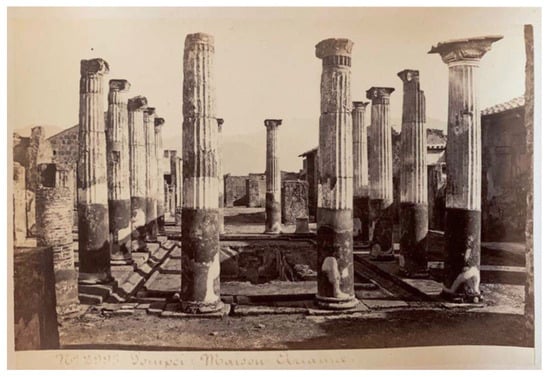

The documentation of the House of Arianna coincided with the emergence of the Scuola di Posillipo, a Neapolitan pictorial movement that, though rooted in naturalist and anti-academic impulses, found in the Vesuvian landscape and ruins a privileged ground for experimentation. Within this context belongs the works of Giacinto Gigante, who between 1835 and 1856 produced two watercolors dedicated to the House of Arianna: the first depicting the south-western corner of the northern peristyle, the second a complex view integrating the smoking Vesuvius in the background with the polychrome Ionic columns and the interior of the oecus (Figure 9a).

Figure 9.

(a) G. Gigante, Watercolour with a perspective view looking north toward the central peristyle, House of the Coloured Capitals, Pompeii, 1856. The rendering conveys the material fabric of the domus and its frescoed surfaces, which appear visibly lacunose around the openings and along the lower wall sections. (b) A. Ala, Pompeii, House of the Coloured Capitals, Wall of the southern oecus (Room 17), 1856. Ala’s drawing captures the appearance of the wall as it emerged from the excavation, clearly conveying the extensive lacunae affecting the frescoed surfaces.

Alongside these artistic interpretations stand authors such as Nicola La Volpe and Antonio Ala (Figure 9b), whose drawings exhibit greater formal and chromatic fidelity to the wall paintings. Of note is also the Album of Pompeii by the Aragonese painter Bernardino Montañés, produced between 1849 and 1850 and consisting of about seventy watercolors, now preserved at the Museo Nacional del Prado in Madrid. His plates document with remarkable precision the decorative schemes of several Pompeian houses, including the House of Arianna, where he reproduced details from the tablinum, the rooms opening onto the atrium and peristyle, as well as architectural elements such as the polychrome capitals and the puteal adorned with a leonine frieze [6].

During the 1840s, the introduction of photography to Pompeii by Calvert Richard Jones and George Wilson Bridges radically transformed the modes of archaeological documentation. Yet, photographic images did not immediately replace drawing, which continued to serve as a medium of aesthetic interpretation and critical reconstruction of ruins. The nineteenth-century watercolors and copies dedicated to the House of Arianna therefore remain irreplaceable sources for understanding the site’s original decoration, now largely lost or altered (Figure 10).

Figure 10.

The central peristyle viewed from the tablinum to the south. Photograph by M. Amodio, from an album dated 1878. Naples National Archaeological Museum (MANN), inv. no. 9977.

The study of documentary, iconographic, and archival sources has made it possible to reconstruct the articulation of the domus from the moment of its discovery, enabling a detailed description of its spaces and layout, as well as an in-depth examination of the restoration interventions carried out over time. These historical materials provided the interpretative framework through which the subsequent direct investigations—geometric survey, diagnostic analyses, and material assessments—could be contextualized and critically verified, ensuring that the case-study reconstruction is historically grounded and methodologically consistent.

At the time of the eruption of AD 79, the House of Arianna exhibited a configuration somewhat inconsistent with the canonical distribution of rooms in Roman houses, likely due to the earthquakes that struck Pompeii in the years preceding the eruption. In its current form, the house is distinguished by the amplitude and complexity of its layout, originally articulated on two levels and comprising about fifty rooms on the ground floor. Like the House of the Faun, the Domus was organized around two peristyles adorned with fountains and water basins, preceded by a large atrium tuscanicum. The tripartite arrangement—atrium, Ionic peristyle, Doric peristyle—is the result of a complex, stratified building process reflecting successive phases of expansion and functional reorganization of the residence. The house had three main entrances: the first, on the southern side along Via degli Augustali (VII 4, 31), led directly to the atrium; the second, to the north, opened onto the large peristyle near Via della Fortuna (VII 4, 51); the third, smaller entrance—no longer visible today—opened onto the Vicolo Storto and gave access to the service area.

The main entrance on Via degli Augustali introduced, through the fauces, a traditional atrium tuscanicum flanked by two rooms probably converted into tabernae. Around the atrium unfolded a sequence of cubicula and alae with a regular plan on the western side—adjoining the House of the Figured Capitals—while the rooms bordering Vicolo Storto show an irregular configuration, adapting to the street’s alignment. This part of the domus, largely devoid of decorated surfaces or prestigious elements, is distinguished by the presence of a lararium with rich wall and floor decoration [6]. This space was the object of a detailed diagnostic campaign conducted by colleagues from the Department of Earth, Environmental and Resource Sciences at the University of Naples Federico II, coordinated by Vincenzo Morra (Figure 11). Analyses revealed the palette of pigments used in the frescoes, including the presence of prized Egyptian blue and cinnabar—rare and costly materials attesting to the ancient prestige of the house [16]. The tablinum, opening both to the atrium and to the central peristyle, served as a hinge between the southern residential and the more monumental sectors of the house. Two lateral corridors led to a richly painted oecus with a window, slightly recessed with respect to the main axis of the building.

Figure 11.

Analysis conducted on the frescoes surfaces by the research unit of University of Naples Federico II: prof. arch. V. Morra, dott. M. Verde (photo E. Fiore, 2024).

With its sixteen free-standing Ionic columns in grey tuff covered with stucco, the central peristyle ranks among the most iconic and representative spaces of the House of Arianna. Unearthed almost intact except for its entablatures, the colonnade is distinguished by Ionic capitals coated with a thick layer of stucco, decorated at the base with a broad band painted in wine-red, while the corners of the volutes are highlighted in a vivid blue—still partially visible today. The presence of color traces on the capitals made the domus a favored subject for draughtsmen, travelers and scholars, who sought to depict this emblematic space and investigate lesser-known aspects of Pompeian architecture. The traces of color extend beyond the capitals to the moldings and lower portions of the column shafts, which underwent an early ancient restoration aimed at concealing the original fluting through the application of a thick stucco layer.

As Guglielmo Bechi observed, “at the base of these columns, one can still see the iron hooks that held the cords of the aulae or curtains that once enclosed this portico” [13] (p. 4), evoking the monumental character of the space and its role in the domestic life of the house. The colonnade also encloses a large rectangular basin lined in cocciopesto and painted blue, featuring a central fountain spout that must have animated the environment with water effects.

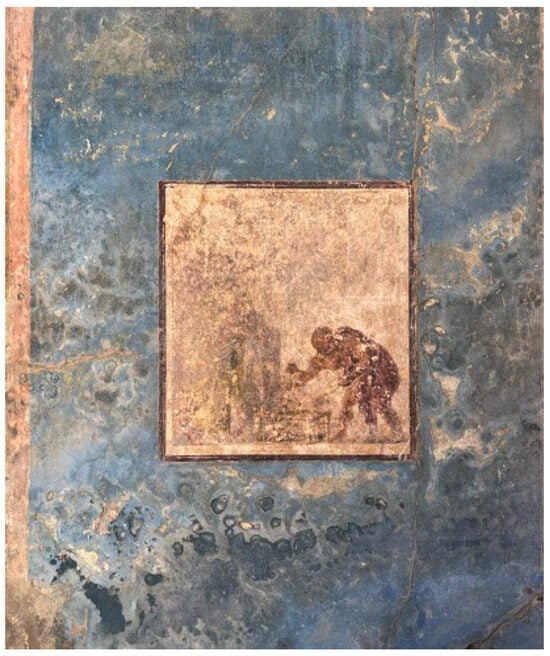

On the western side, the walls of the central peristyle contained two cubicula, an exedra adorned with high-quality wall paintings, a staircase that probably led to the upper floor of the domus, an apotheca, and a large oecus-triclinium. The exedra, with its sky-blue walls, still preserves in situ fragments of its ancient fresco decorations “paintings of landscapes, trophies, and various ornaments, rendered with astonishing mastery, among which is the picture of an old man selling Cupids in a cage, like caged birds” [13] (p. 4) (Figure 12).

Figure 12.

House of Arianna, central peristyle, exedra. Fresco with the Venditore di Amorini (photo E. Fiore, 2024).

At the eastern end of the peristyle, another oecus provided access to a staircase leading to the upper floor of the house and to a subterranean lararium featuring the depiction of a serpent Agathodaimon, a benevolent, apotropaic figure recurring in Pompeian iconography as a symbol of prosperity, domestic protection, and fertility.

Crossing a tablinum with a tessellatum pavement of white tesserae bordered in black leads to the area of the northern peristyle, sometimes referred to as the Corinthian atrium. This area is slightly misaligned with respect to the general layout of the House of Arianna due to major transformations following the earthquake of AD 62, when five small rooms and a lararium were built abutting the northern peristyle, resulting in the closure of the surrounding corridor. Although devoid of elaborate decorations, this area is characterized by twenty-four free-standing columns in tuff, opus incertum, and brickwork, with Doric capitals and stucco coating. This finishing, dating to the post-earthquake rebuilding phase, was intended to homogenize the architectural surfaces of the columns, masking material discontinuities and enhancing their solidity, a practice widespread in Pompeian building sites and consistent with Vitruvian precepts [17].

Nineteenth-century accounts—such as those by Bechi and by the Niccolini brothers—had already emphasised the monumental character of the complex, noting how the spatial sequence of atrium, tablinum, and peristyle was conceived along a carefully orchestrated axial perspective that linked the public sphere of representation to the more private dimension of the inner garden. The meticulous masonry, opus tessellatum pavements, and Fourth-Style wall decorations make this domus a privileged testimony to the evolution of Pompeian domestic architecture between the late Samnite period and the Augustan age.

The study of indirect sources also included an examination of the archival records held in the Scientific Archive of the Archaeological Park of Pompeii, relating to the restoration interventions carried out on the domus over the course of the twentieth century.

This documentation, although partially incomplete, sheds light on the works undertaken to restore the continuity of the vaults in the underground spaces, achieved through the integration of missing portions with lightweight conglomerate and the filling of haunches with soil and pottery fragments recovered on site. Structural consolidation also involved the insertion of polypropylene fibres, as well as injections of mortar and binding mixtures.

The records examined—dating to the 1980s and 1990s—further reference additional restoration activities, including the revision and reconstruction of existing roof structures, the consolidation of masonry, the repair and waterproofing of wall crests, the replacement of decayed architraves, the consolidation and cleaning of detached plasters and stuccoes, and the anchoring of several columns in the northern peristyle.

However, this documentation is not sufficiently comprehensive to determine the full extent of the interventions carried out on the structures, making it necessary to strengthen the phase of direct analysis of the built fabric.

3.2. Results from Architectural Survey of the Domus of Arianna in Pompeii

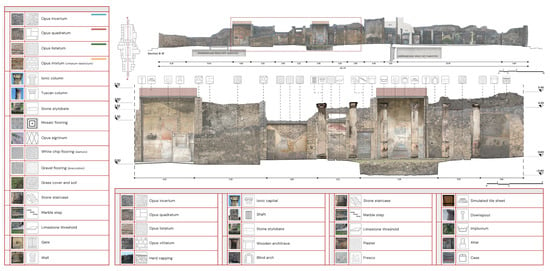

The study of indirect sources was consistently accompanied by an analysis of the material evidence through a detailed survey phase, conceived not merely as a recording exercise but as a critical tool for refining and verifying the data previously gathered during the documentary research stage (Figure 13).

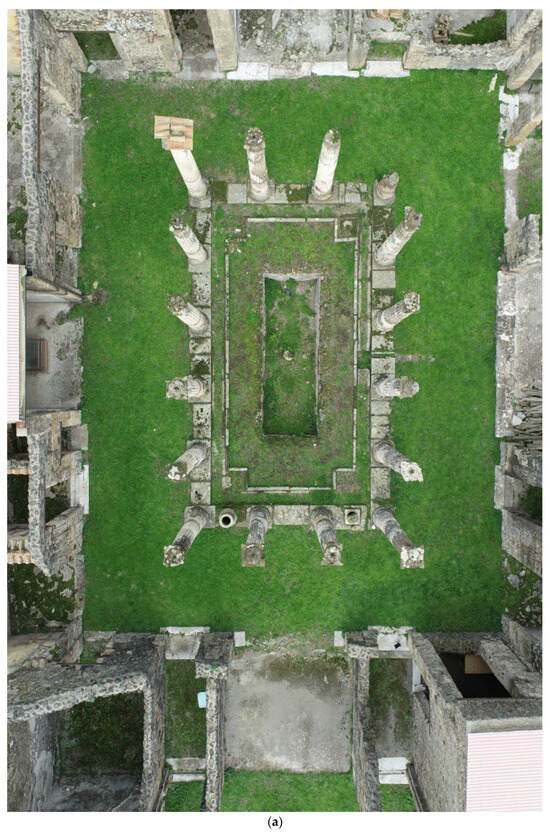

Figure 13.

Pompeii, Plan of the House of Arianna (VII 4, 31–51) obtained from the drone-based photogrammetric survey carried out as part of the CHANGES research project. The high-resolution model reveals the material consistency of the architectural remains and the preservation condition of the floor levels (drone photo M. Facchini, 2023).

The considerable complexity of the architectural layout and the diversity of its decorative schemes required the adoption of technologies capable of capturing both morphological and material information, to be integrated directly within the digital modelling process. The architectural survey for conservation purposes must, in fact, contribute to achieving a comprehensive understanding of the monument, encompassing all aspects—from dimensional and constructional characteristics to chronological transformations, from its current state of preservation to static conditions and compositional principles.

The survey phase therefore operated as a non-invasive diagnostic examination of the monument, highlighting all the specific features that must be considered in the restoration design process.

Based on these premises, both range-based and image-based techniques were adopted. The acquisition of metric and material data was conducted using active optical-sensor technology, specifically the Laser Scanner FARO Focus3D X330 phase-shift laser scanner, which allowed the accurate and rapid definition of the topography of portions of the domus, at a level of precision difficult to achieve with conventional surveying instruments. Scans were carried out at a resolution of 6.136 mm, at a maximum range of 10 m in 3× quality mode, corresponding to a resolution of approximately 12.3 mm at that distance for the FARO Focus3D system.

The data obtained from the laser scanner survey, once processed, yielded a model perfectly consistent with the real structure, from which a significant quantity of information could be extracted: dimensional values, orthophotos, three-dimensional models, textures, and spherical images. The laser-scanning results were then integrated with photographic data captured via drone-mounted camera, which enabled improved visualization of the roof extradoses, wall crests, and pavements of the domus through orthogonal imagery. This comprehensive survey made it possible to carry out a detailed study of the construction techniques and the forms of structural damage and decay affecting the entire domus (Figure 14).

Figure 14.

Technical drawing of the House of Arianna with the representation of material and construction techniques.

Methodologically, each space within the house was assigned a progressive numerical code to ensure unambiguous identification. Within each room, surfaces were labelled using Arabic letters, in accordance with the cataloguing system of the Archaeological Park of Pompeii. This classification proved essential for identifying and mapping the construction techniques that characterize the domus within the digital model and for formulating preliminary hypotheses regarding the causes of the observed deformations and decay phenomena.

As part of the direct study of the House of Arianna, particular attention was devoted to identifying specific areas of investigation, defined according to the most pressing issues concerning the conservation of the archaeological fabric and the long-term preservation of the structures. Within this interpretative framework, two principal fields of study were selected: (a) the surfaces of the domus—both frescoed walls and pavement mosaic; (b) the free-standing columns in the two peristyles, a set rendered especially vulnerable by the absence of trabeation and by heterogeneous building techniques.

3.3. The Study to Preserve Architectural Surfaces: Mosaics and Frescoes in the House of Arianna

“The house featured a Tuscan porch overlooking the atrium, with walls adorned with splendid marbles and exquisite paintings. These decorations were lost when the impluvium was dismantled, and the embellishing ornaments were removed” [18].(p. 218)

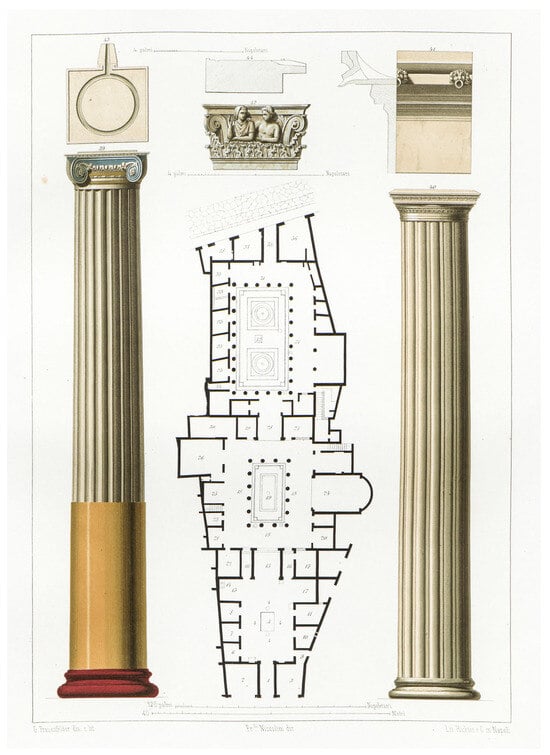

The detailed description of House of Arianna provided by Giuseppe Fiorelli in 1875 in his work Description of Pompeii attests to the symbiotic relationship between the house and the rich marble, mosaic, and pictorial decorations that once adorned its architectural surfaces, including both walls and floors. Indeed, House of Arianna, the central building of Insula 4 in Regio VII, has exemplified this relationship since its rediscovery in 1833 [13], which revealed much of its polychrome decorative elements still preserved (Figure 15).

Figure 15.

G. Fraunfelder, Lithograph of the ground plan of the House of Arianna, with details of columns and capitals, c. 1850s, in Niccolini, F., Niccolini, F., Le case ed i monumenti di Pompei disegnati e descritti, Naples 1854, tav. II.

Yet, Fiorelli’s description, which references a now-distant splendor, also testifies the nearly complete loss of the decorative furnishings of the recently excavated domus. Fragile testimonies to ancient taste and ways of life, the architectural and decorative surfaces of House of Arianna were already partially missing at the time of excavation—especially the marble decorations that must have enriched the walls of some rooms and the pool. Guglielmo Bechi, in his Report on the Excavations of Pompeii, attributes these gaps to the actions of the ancient inhabitants themselves following the eruption: “All that remains of the base and the paintings is to convince us that the ancients themselves, who entered this house after the eruption, removed all the marble that adorned this atrium” [13] (p. 2).

Despite the structural consolidation efforts undertaken immediately after the excavation, the gradual loss of the most precious and fragile materials within the domus remains evident today (Figure 16). Currently excluded from the visitor routes of the Pompeii Archaeological Park, the ancient house faces significant conservation challenges affecting both its vertical and horizontal surfaces. The combined effects of atmospheric agents and aggressive weeds erode the frescoed walls and floors, leading to a slow but inexorable deterioration—partially mitigated by the essential safety and maintenance measures implemented by the Pompeii Archaeological Park.

Figure 16.

House of Arianna, the exedra’s frescoes (photo E. Fiore, 2025).

Building on this foundation, special attention has been given to the interpretation and analysis of conservation issues affecting the site’s architectural surfaces. As part of a broader restoration and enhancement project encompassing Regio VII, a comprehensive plan for restoring and upgrading the artistic components of the domus will be essential, with particular focus on ensuring their safe in situ preservation. As we will observe, the in situ conservation of these artifacts—such as mosaics, frescoes, ceramics, and stucco decorations—is closely linked to considerations regarding accessibility and the broader use of the domus (Figure 17).

Figure 17.

House of Arianna, pavements with mosaics (photo E. Fiore, 2023).

For instance, the presence of floor mosaics in the spaces connecting the first and second peristyles presents a key design challenge from both a conservation perspective and in terms of the site’s functional reuse. The decision to preserve these mosaics in their original location influences the overall conservation strategy and inevitably complicates the development of accessibility plans for the ancient Roman residential complex.

A detailed survey was carried out to assess the condition of the structure. This process involved photogrammetric and geometric restitution of each room, followed by identification of degradation and alteration phenomena affecting the architectural surfaces, in accordance with the guidelines of Lessico NorMal 11182/2006 [19].

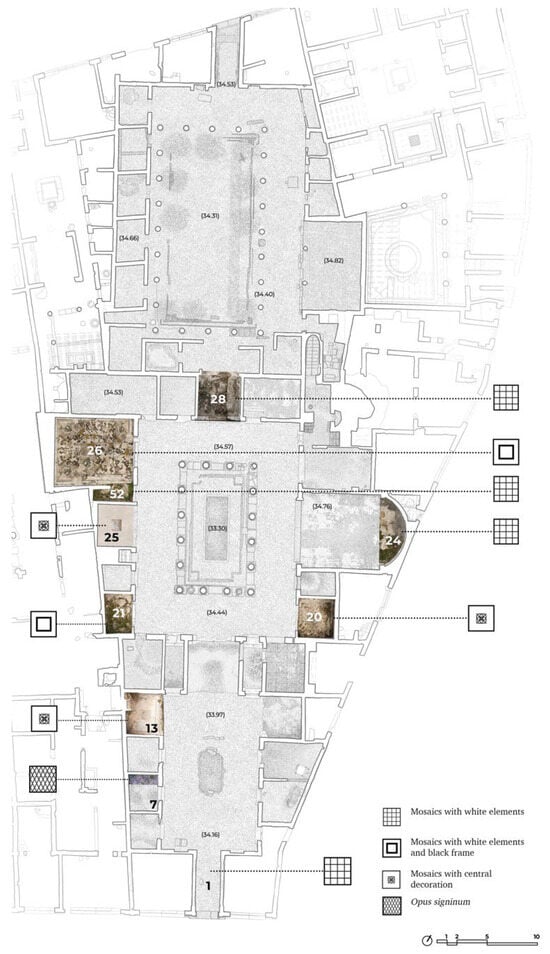

In evaluating the conservation status of House of Arianna, particular attention was given to issues currently impacting the floors—especially those decorated with mosaics—and the wall frescoes. Mapping and identifying the main conservation concerns represented a crucial initial step in understanding the property, essential for informing conservation strategies within the broader context of plans for reopening, enhancing, and restoring the entire insula.

3.3.1. Pavements with Mosaics

“Its entrance or hall n. 1 no longer shows any traces of its original decorations, except for a floor composed of a mixed brick and cement material, delicately adorned with white mosaics featuring lynxes elegantly intertwined” [13].(p. 1)

The evocative description of the entrance to House of Arianna, proposed by Bechi and later revisited by the brothers Fausto and Felice Niccolini in 1854 [20], introduces us to a recurring compositional theme in the ancient domus: the presence of precious floor inlays between its main rooms [13].

There are ten rooms in which traces of the ancient mosaic floor systems are still visible today, identified and described during the research (Figure 17). The entrance room described by Bechi (room 1) had a cocciopesto floor interspersed with a network of double meanders and rhombuses, geometrically inscribed in rhombuses or circles. The original compositional scheme was graphically represented by Niccolini in 1843, accompanied by a detailed descriptive note: “NB the lines that are red in this plan are nothing other than rows of white mosaic stones placed at an angle each measuring 10 millimeters square, on a pavement of lime and crushed brick” [21] (p. 1). Few traces of this floor remain today: a condition confirmed during the restoration work carried out between 1979 and 1989. Larger portions of opus signinum can be found in room 7 (Figure 18); two-tone mosaics made up of black and white tiles are instead placed in the exedra room (room 24), in the passage between the two peristyles (room 28) and in the small room 52; floors in white tiles with a black perimeter band are located in rooms 21 and 26; and the richest and most complex floor mosaics, with central figurative decoration, are placed in the lararium (room 13), room 20, the room containing the fresco of Theseus and Ariadne, and room 25, the rectangular exedra. The latter recalls a recurring theme in Roman domus, that of water, through the depiction of fish on a dark background, surrounded by a marble frame and light-colored tesserae.

Figure 18.

Traces of opus signinum in the room 7 (photo S. Iaccarino, 2025).

The state of conservation of the mosaics is unfortunately aggravated by environmental conditions and direct contact with the ground: rising damp from the subsoil increases the level of tesserae decohesion, as do freeze–thaw cycles. This condition is further exacerbated by the emergence of spontaneous vegetation in all the environments described above. Due to the development of root systems of varying depth, this increases the disintegration of the bedding layer of the floor layers, leading to fractures in the subgrade and detachment of tesserae, which today lie erratically in almost every room of the domus (Figure 19).

Figure 19.

Plan with indication of room with the presence of mosaics.

The Archaeological Park of Pompeii currently employs numerous measures to protect these floors, especially during the winter season: the installation of temporary protection systems to limit the action of rain and wind during the coldest months of the year limits the dispersion of erratic material and, at the same time, the increasingly significant process of grassing that plagues these areas.

However, a restoration intervention extended to the entire floor plan of the domus is an essential condition for their correct conservation Despite the serious state of conservation and the slow and gradual loss of the two-tone tessellation, these mosaics were in fact the subject of a systematic series of restoration interventions only in 1989: following the war damage of 1943, consolidation interventions carried out on the reinforcement of the walls and architraves and the installation of new roofing structures were considered priority, postponing the restoration interventions to be carried out on the decorative apparatus of the domus until a later date. The 1989 intervention carried out by the Archaeological Superintendency of Pompeii was grafted onto this ruinous state of conservation, a consequence of the war damage and the priority given to the consolidation of the wall components, as well as the more recent damage caused by the 1980 earthquake [22]. Between 1987 and 1989, filling and restoration work was carried out on the floors, which at the time were largely lacking, sometimes even in the bedding layers: the mortar between the tiles was almost completely absent, increasing the level of detachment of entire fragments of the tessellated tiles, which were subject to complete loss of adhesion to the substrate. The gaps also affected the cocciopesto and opus signina floors, which were attacked by invasive vegetation. The state of conservation described above, and the related restoration work carried out are evidenced by the abundant photographic documentation—conducted both in the pre-restoration phase and during the delicate operations of weeding, cleaning, consolidation and reintegration—kept in the digital photographic archive of the Archaeological Park of Pompeii [23].

3.3.2. Wall Frescoes’ Surfaces

“A larger triclinium follows the one described […] It was nobly painted and contained a picture with Ariadne asleep on the knees of Sleep, discovered by a Cupid at the approach of Bacchus, who, followed by his thiasos, contemplates her” [18].(pp. 219–220)

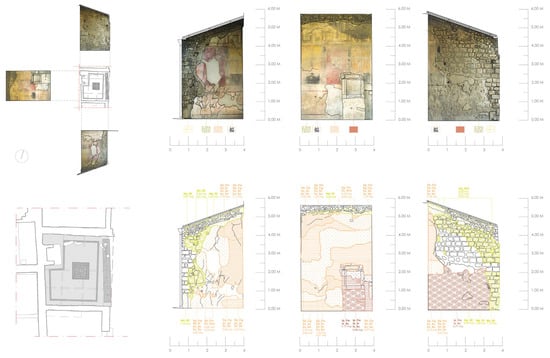

As for the other houses in Insula 4, during the research particular attention was paid to the reconnaissance and mapping of the state of conservation of the wall frescoes of the domus of Arianna still preserved in situ.

The most significant remains are concentrated on the walls of the exedra, on the south and west walls of room 14. (west wing, with lararium), in the oecus (room 17), room 20, and room 26. During the research, specific drawings were prepared for each room, detailing the layout of the walls (Figure 20).

Figure 20.

Analysis of the state of conservation of room 13 according to the Lexicon UNI 11182/2006.

These drawings also included metric and material data, as well as data relating to the identified forms of deterioration. This methodology allowed for the creation of a map of the most frequently encountered forms of deterioration [19]—detachments, stains, cracks, and chromatic alterations—attesting to the frescoes’ current state of conservation. This, too, is primarily due to the restoration work conducted during the twentieth century, concurrent with post-war repairs, which culminated in the restoration of the frescoes’ adhesion to the support and are extensively documented. The photographic evidence highlights, in particular, the symbiotic relationship between the ‘skin’ and the ‘structure’ of the domus, whereby the most serious cracks, damaging both the masonry and the decorative components, made the consolidation of the walls a priority, before moving on to the consolidation of the frescoes and, therefore, the re-adhesion of the frescoes to the walls.

Today, more than the loss of contact between frescoes and masonry, the surface problems related to the frescoes’ exposure to the environmental context and humidity are of concern.

Despite the protection systems present in the House of Arianna—both roofs and tiles placed around the perimeter above the decorated plasterwork—the frescoes, especially those located in the uncovered rooms, are affected by alterations and stains due to rainwater and rising damp from the ground, which, in many cases, has led to the loss of the chromatic component. A different state of conservation, however, affects the frescoes located in the covered rooms of the lararium and of the oecus which, thanks to the more effective contribution of the twentieth-century protective coverings, reveal more vivid colors and preserve their figurative nature intact.

For the frescoes, too, the research envisioned pre-consolidation, cleaning, surface consolidation, and protection interventions, differentiated according to the state of conservation of each surface. Recognizing direct exposure to the elements as a major factor in deterioration, conservation efforts focused on protecting the architectural surfaces of the open spaces, only partially protected by the tile systems. These, now obsolete, require updating to consider the conservation approaches historically employed on Pompeii’s buildings, with the goal of restoring and transmitting the historical material to the future, ensuring its legibility.

The high level of mosaic floors and wall frescoes makes the restoration of the architectural and decorated surfaces of House of Arianna a priority, marked by considerable technical and managerial complexity. This complexity is inherent in the fragility of these decorative elements, whose figurative quality must be protected to convey the narrative and importance of the domus to visitors. At the same time, it is rooted in the complex relationship between surface and structure, whose mutual interference requires an interdisciplinary and technically savvy approach for their proper conservation.

The interference between decoration and substrate is particularly critical when analyzing mosaic floor surfaces, especially in terms of use and accessibility. The House of Arianna plays a central role in terms of the fruition of Insula 4; ensuring its full use along its longitudinal axis would constitute a virtuous opportunity to traverse the entire insula, significantly improving the enjoyment not only of the domus itself, but also of the ancient settlement.

In the complex development of visitor itineraries for the domus of Insula 4, it was essential to consider potential interference with the remaining decorated remains. In this sense, it’s necessary to design a visit route through the domus consistent with the valuable archaeological remains. The solution evaluated in the research involved the replacement of the beaten earth flooring where deficient and the insertion of contemporary junctions (ramps and removable walkways) to ensure safe use of the house while preventing direct trampling on the floor surfaces. The connection between the two peristyles (room 28) proved particularly complex: still rich in erratic two-tone tesserae, this passageway required immediate intervention to secure and consolidate the floor support, which was most exposed to the walking of the domus users as it was the only room connecting the two peristyles. One possibility of use that guarantees the in situ preservation of the mosaic and, at the same time, easy access to the second peristyle from the first could be the insertion of a double ramp with a flat walkway that makes the underlying mosaic visible, a solution hypothesized and explored in the research presented here.

Ensuring the conservation of the mosaics in situ would increase the level of cognitive enjoyment of the domus, thanks to the natural process of contextualizing the mosaic or fresco perceived within the very environment in which it was conceived in antiquity: a condition that, after all, has been desired since the rediscovery of the city of Pompeii in the nineteenth century, later reaffirmed by the Valletta principles for the protection and management of the archaeological heritage [24]. The careful design of technical and technological elements such as coverings for the frescoed surfaces and, at the same time, the definition of visitor routes that limit direct walking on the ancient mosaics would thus allow Arianna’s domus to pass on its precious story and its most authentic colors to the visitors of tomorrow.

3.4. Structural Fragility and Diagnostic Investigation of the Free-Standing Columns in the House of Arianna

Building on the previously discussed conservation issues affecting open-air archaeological structures in Pompeii, this section focuses on the specific vulnerabilities of the Free-Standing Columns in the House of Arianna (VII 4, 31–51). The loss of trabeations and bonding elements, together with the long-term exposure of its colonnaded spaces to environmental stressors, has rendered the peristyles both architecturally emblematic and structurally fragile (Figure 21).

Figure 21.

Pompeii, House of Arianna, VII 4, 31–51. Perspective view of the central peristyle, highlighting the condition of the free-standing columns of the domus and those of the neighboring House of the Figured Capitals, which illustrates the differing structural consistency of the two colonnaded systems (drone photograph by M. Facchini, 2023).

The two peristyles of different chronology and function [6,7] now represent the most critical element for the overall stability of the domus, which remains subject to multiple risk factors limiting its accessibility; indeed, the house is currently closed to the public. The repairs undertaken after the AD 62/63 earthquake and the restorations carried out following the nineteenth-century rediscovery (1832–1835) heightened this constructional heterogeneity, emphasizing the fragility of the open spaces of peristyles and identifying the columns as the weak point of the entire complex, hence the ongoing restrictions on visitor access. Direct examination of the domus, combined with an analysis of its static history—including the identification of past restorations and ongoing decay phenomena—proved crucial for understanding the structural behavior of the free-standing columns.

This process clarified several aspects of the material composition and construction logic of the two peristyles which, since antiquity, have represented the most vulnerable elements of the building. Recent archaeoseismological studies have demonstrated that these areas were already severely damaged by the earthquake that struck Pompeii prior to the eruption of AD 79. The event caused the overturning and collapse of the structures in the northern peristyle—later subject to significant post-seismic reconstruction—and inflicted serious damage on the central peristyle [25].

The latter, dating to the second half of the second century BCE, consists of sixteen fluted grey-tuff columns coated with polychrome stucco, each measuring approximately 4.44 m in height and 53 cm in diameter. Among the most iconic features of the domus, these columns were redecorated during the Julio-Claudian period with vividly colored stuccoes that altered their original moldings and palette [13,20].

The northern peristyle, by contrast, dates to the Augustan period and comprises twenty-four columns of varying height with an average diameter of 46 cm, constructed using mixed techniques and materials—grey tuff, brick, limestone and cruma—unified by a robust stucco coating with Doric flutes. The Doric-Tuscan capitals and Attic bases reflect a simplified architectural language typical of post-seismic reconstructions, consistent with the taste of the late Republican era [26] (Figure 22 and Figure 23).

Figure 22.

Pompeii, House of Arianna. View of the northern peristyle (photo E. Fiore, 2025). The differing material composition of the colonnaded structures is clearly visible, the result of post-earthquake reconstructions following the AD 62 seismic event. One can observe brick elements, tuff blocks, and stone units, all unified by a stucco coating with fluting.

Figure 23.

View of the central peristyle of the House of Arianna. The image highlights the current conservation state of the structures and the presence of three protective shelters installed over the decorated rooms (photo E. Fiore, 2025).

A closer analysis of the central peristyle proved essential for evaluating the structural behavior of the free-standing columns and assessing risk associated with their current configuration, independent shafts without upper connections.

Within the CHANGES Spoke 6 project, the diagnostic campaign on the columns of both the northern and central peristyles included thermographic and pacometric investigations, with the goal of examining the connections between stone drums, detecting material discontinuities and identifying areas of detachment not directly accessible due to the preservation of original finishing layers.

Although these methods do not allow exploration of the inner core of the columns, the measurements made it possible to identify historical consolidation systems used to re-adhere and stabilize stuccoes and plasters, consisting of small metal brackets and clamps inserted into the stone to depths of up to 3 cm and set radially.

Thermographic analysis highlighted the constructional heterogeneity of the northern peristyle’s masonry columns and revealed ongoing cracking and detachment processes in both colonnades. This allowed the immediate identification of the most vulnerable areas, enabling targeted stabilization and preventive measures to reduce the risk of material loss (Figure 24a,b).

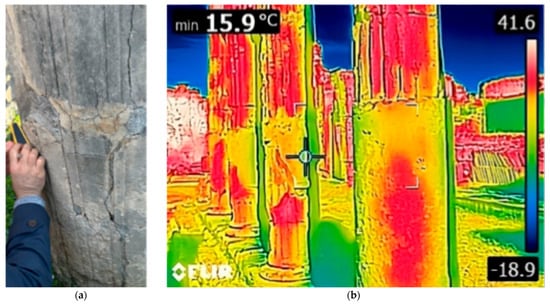

Figure 24.

(a) Pompeii, House of Arianna. Pacometric investigations carried out on the columns of the northern peristyle of the domus (photo E. Fiore, 2025). (b) Pompeii, House of Arianna. Thermography analysis of the central peristyle.

The internal configuration of the columns in the central peristyle was further investigated by means of high-frequency geophysical prospecting, applied to both the peristyle pavements and the vertical structures, to detect discontinuities, voids and inclusions not visible at the surface. GPR scans, carried out with a 400 MHz antenna for the pavements and with a very-high-resolution stepped-frequency system for the columns, revealed hyperbolic reflections and variations in the dielectric constant (εr) along the shafts of the central peristyle columns, interpreted as indicators of internal discontinuities. Longitudinal sections displayed an axial anomaly at approximately 1.50 m above ground level, corresponding to a vertically oriented trace compatible with a non-metallic connecting element between drums. These data were complemented by circumferential profiles at various elevations, which confirmed the absence of significant internal anomalies and revealed only micro-irregularities attributable to porosity or micro-fractures in the stone, without affecting the overall integrity and stability of the House of Arianna’s free-standing columns.

Although they do not provide a direct measure of load-bearing capacity, these results nonetheless offer valuable insight into construction processes, internal configurations and joint interfaces, forming the basis for the definition of conservation and maintenance strategies. The integration of these findings with earlier research on Pompeian peristyles has led to two hypotheses regarding the construction of the central peristyle columns. The first, based on comparisons with the western area of the Forum, posits a tenon connection between drums; the discovery in the Vicolo del Gallo area of a similar element set in mortar within a square recess supports this technique, which notably excluded the use of lead, consistent with GPR results [27].

The second hypothesis, based on research by the École française de Rome and the Centre Jean Bérard, interprets the detected discontinuity as the trace of a void related to turning processes and to the setting system for grey-tuff columns [28,29]. Studies on Campanian ignimbrite and stone-working techniques have demonstrated that tuff columns and capitals were shaped using vertical or horizontal stone lathes, as attested by parallelepiped mortises and axial cavities identified on ancient blocks. At the height of the mortise openings, chisel marks can often be observed along one or two adjacent sides of the bearing planes; these indicate the process used to release the inserted piece once the turning was completed. Although such evidence cannot be directly observed in the House of Arianna due to the integrity of the central peristyle columns, it finds a plausible correspondence in the irregular extent of the anomaly recorded through ground-penetrating radar analysis. Experimental replications have confirmed the feasibility of manually rotating tuff blocks weighing 250–300 kg on horizontal stone lathes to produce perfectly cylindrical shafts [29]. The turning traces observed on the stone blocks of the columns in the central peristyle of the House of Arianna coincide with those documented in other Pompeian contexts, attesting to specialized workshops and semi-standardized techniques in the production and installation of these architectural elements [30,31].

Recent structural analyses have confirmed the consistency of the in situ geometric and material data, highlighting the physic-mechanical properties of Neapolitan grey tuff, a lightweight, highly porous material with compressive strengths between 1.4 and 2.4 MPa and an elastic modulus ranging from 900 to 1260 MPa. Numerical simulations conducted on representative models indicate that, under both static and seismic loads, the peristyle structures retain a generally stable elastic behavior, albeit with localized vulnerability to drum slippage at upper joints where adhesion is reduced [32,33].

These results confirm earlier diagnostic hypotheses regarding internal discontinuities and cavities, reinforcing the need for reversible, low-impact conservation measures aimed at mitigating risks of displacement and loss of cohesion without altering the original fabric.

Archival sources, particularly the Libretto delle Misure dei Lavori di Pompei (1835–1839), further illuminate the history of the colonnades [33]. The document records that, at the time of excavation, the ancient columns enclosing the central peristyle were found partly toppled and incomplete, with several drums missing. Twenty-five of these fragments were later recovered as excavations progressed and reassembled through experimental anastylosis: the drums were manually hoisted and repositioned using ropes and straps. The capital of the fourth column on the left side of the peristyle, discovered broken into two pieces, was initially secured with ropes to prevent collapse. It was later stabilized by inserting two iron clamps that rejoined the fragments into a single element. The capital thus consolidated was then placed in position on a bearing surface made of roof tiles [34].

The Misure dei Lavori also describes the placement of tiles as protective covers over the top of the last column on the left side of the central peristyle—“found intact upon discovery” [34]—and the execution, on the capital, of a small built-up block in mortar and brick to ensure the necessary slope for rainwater runoff. (Figure 25a,b).

Figure 25.

(a) Pompeii, House of Arianna, VII 4, 31–51. Perspective on the central peristyle (drone photograph by M. Facchini, 2023). (b) Pompeii, House of Arianna. View of the northern peristyle (photo E. Fiore, 2025). The photographs highlight the state of conservation of the free-standing colonnades of the central peristyle, which appear to be heavily affected by black crusts and by fracturing of the stucco layers applied in the first century CE over the stone drums. The images also show the nineteenth-century restoration interventions carried out on the columns.

At the base of the entrance side of the portico, another built-up block was constructed to fill and consolidate the ancient portion eroded by time, restoring its structural stability. These represent the most recent known consolidation interventions on the free-standing columns of the central peristyle; since then, the columns have not undergone further conservation work, except for occasional maintenance.

Although they appear broadly stable today, closer inspection reveals a gradual yet progressive material and structural decay. Exposed to the open air for nearly two centuries, the free-standing columns of the House of Arianna constitute a system vulnerable to multiple external agents: horizontal forces generated by wind and seismic activity, mechanical stresses linked to increasingly intense meteorological phenomena, and differential decay caused by ageing and alteration of constituent materials. The main pathologies observed include combined compression–bending deformation of the shafts, cracking and section loss at the base, detachment and disintegration of stucco layers, oxidation of metal cramps, out-of-plumb alignments, drum slippage, and localized fractures in the capitals.

Results from direct investigation confirmed the presence of discontinuities and internal anomalies within the columns of the central peristyle. These data support the hypothesis that internal connecting elements were originally employed, an interpretation currently under further study. Pacometric testing in the northern peristyle also revealed historical consolidation systems made of metal components inserted into the columns during interventions intended to preserve ancient plaster surfaces.

The diagnostic evidence obtained corresponds closely with archival documentation, which describes the use of metal clamps set radially to stabilize the structures. However, these historic inserts have since become a source of deterioration, particularly in areas where the original stucco coatings now exhibit fracturing, powdering, and detachment associated with the corroding metal elements (Figure 26).

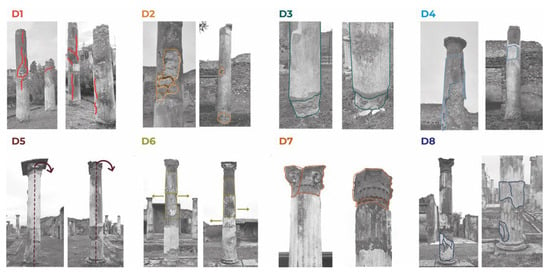

Figure 26.

Pompeii, House of Arianna. Main conservation issues of the columns of the peristyles. (D1) cracking; (D2) presence of voids and discontinuities; (D3) reduction in the section to the basement portion; (D4) cracks and voids of plaster on the northern peristyle; (D5) rotation of columns; (D6) sliding of elements; (D7) cracks of capitals; (D8) cracks and voids of plaster on the central peristyle (elab. L. De Riso, 2023).

Collectively, these findings underline that the columns of the central peristyle suffer from a combination of structural and material vulnerabilities—including crushing of the free-standing shafts, voids and discontinuities, reduction in base sections, fracturing and detachment of plaster, overturning tendencies, drum slippage, and capital fractures. These conditions call for restoration strategies that respect the fragility of the archaeological fabric and are conceived as reversible, compatible, and adaptable to future reassessment through ongoing monitoring and maintenance.

The research undertaken at the House of Arianna underscores the pivotal role of interdisciplinary approaches in the conservation and restoration of archaeological heritage. Through the combined application of non-destructive diagnostics, structural analysis, and archival investigation, the project has not only contributed to the physical preservation of ancient architecture but also deepened our understanding of the materials, construction techniques, and historical interventions that have shaped the site over time. The knowledge gained from this integrated approach provides a robust foundation for sustainable, evidence-based restoration practices, ensuring the long-term preservation and cultural transmission of this exceptional example of Roman domestic architecture.

3.5. Conservation Guidelines: An Interpretative Review of Best Practices

The integrated interpretation of past restorations, construction techniques, and current conservation conditions confirms the need for an intervention strategy deliberately calibrated to the level of risk—understood as the combination of the probability of a damaging event, the magnitude of its potential impact, the vulnerability of the asset, and its exposure—as identified through research, and structurally grounded in the discipline’s shared ethical principles of authenticity, integrity, compatibility, reversibility, and minimum intervention [35].

In line with the SIRA Documento di indirizzo (2023) [36] (Section 4.4), these principles are operational criteria to be made explicit in design choices and monitored over time; SIRA emphasizes, in particular, that minimum intervention and reversibility require solutions that are materially and conceptually ‘retractable’, limited to what is strictly necessary, and recognizable yet compatible with the historic fabric.

Taking into account the two principal research strands, this section specifically outlines the methodological guidelines for the conservation of the floor mosaics and the free-standing columns in the two peristyles. Although wall paintings and other decorated surfaces are not the direct object of this paragraph, they remain crucial to calibrate materials’ compatibility and intervention thresholds. The recent Spanish program on the House of Arianna (pre-consolidation cleaning with dry sponges and ammonium-bicarbonate gels; testing of hydroxyapatite and ethyl silicate consolidants; targeted carbonation of lime-based mortars) is exemplary of a non-invasive, evidence-led methodology [37] (pp. 93–103).

The interpretative approach adopted is deliberately procedural; it aligns conservation choices to a matrix of a historical-knowledge-based model, constructions techniques, and decay phenomena rather than to one-off ‘solutions’, and it seeks the least invasive effective option that remains compatible and ideally reversible over realistic maintenance cycles [2,38,39] (Figure 27).

Figure 27.

Pompeii, House of Arianna, VII 4, 31–51. Perspective (drone photograph by M. Facchini, 2023).

3.5.1. Free-Standing Columns in the Two Peristyles

The peristyles’ free-standing columns—behave as isolated vertical bodies with little capacity to share or redistribute loads. Their vulnerabilities are well documented: base section loss (especially in the first peristyle), voids and discontinuities between drums, incipient out-of-plumb, and detachment/loss of stucco; crucially, construction is heterogeneous, ranging from masonry-built shafts to multi-drum fustes with thick stucco coats, implying different interfaces, joint behaviors and failure modes under wind, seismic rocking and water-driven wash-out. At Pompeii more broadly, recent geometric surveys of 103 multi-drum columns confirm how slenderness and degradation co-steer risk and, consequently, the type and threshold of intervention [33]. Within this picture, two families of measures recur in the literature and in recent practice; each has plausible applications in the Domus but also constraints that argue for a graded, knowledge-based use:

- Conservative consolidation of the existing fabric: Where section losses and voids are localized, targeted restitution of the load path with like-for-like materials should precede any mechanical restraint. For masonry-built shafts (as in parts of Peristyle I) this points to brick/stone integration at the base with lime-based mortars and good bonding to the historic work, distinguishable yet structurally effective; horizontal stainless micro-reinforcement can be introduced only where strictly necessary to re-establish shear transfer across new-to-old interfaces (cf. the masonry integrations and discreet stainless bars in the Forte di Fuentes work by Dezzi Bardeschi and Jurina) [40]. For multi-drum stone shafts, the priority is restoring contact and friction at joints while avoiding invasive through bars and cementitious grouts that have proven incompatible and harmful in the medium term (oxidation/expansion, fracture propagation). Historic cases at Pompeii (post-1980 earthquake) where drums were drilled and cement-grouted around steel connectors developed sub-vertical cracking from corrosion; the eventual mitigation required stainless steel banding of drums, after removing inappropriate materials [41] (pp. 397–408), [42] (p. 221). In our case study, baseline actions should include: lime-compatible injection to restore cohesion where preparatory mortars and bedding layers are degraded; reversible micro-stitching with stainless pins only at very localized cracks, if necessary; and reconstruction of missing base sections with compatible stone/brick units and lime mortars, carefully toothed into the original (the latter is indispensable in Peristyle I).

- Passive, low-impact restraints: Recent experiences at Pompeii and in analogous archaeological settings show a spectrum of passive measures—stainless collars at drum joints; tensioned guy-cables discreetly anchored to boundary walls; and, in exceptional cases, freestanding, light counter-bracing frames—conceived as retractable aids to stability under wind/seismic pulses. At Pompeii these have included stainless stralli (Ø 10–12 mm) set at various inclinations to counter rocking at the Casa del Citarista (I, 4, 17–25) and other sites, with sacrificial lime-mortar bearing pads enabling future disassembly [40,43,44]. In Regio VI, targeted metal banding with neoprene interlayers has been used to block rotation where diagnostics proved joint opening and out-of-roundness (cf. Casa del Labirinto, Casa dell’Esedra) [45] (pp. 203, 207, 210). These measures are indeed apparently simple and reversible, but their acceptability for the Domus hinges on: (a) avoiding invasive anchors in ancient drums; (b) detailing for drainage, galvanic isolation and inspectability; and (c) embedding their use within a measured structural rationale—custom-fitted to each column, compatible with the continued usability of the spaces, and designed for potential future reversibility.

From a decision-support standpoint, three filters emerge for the House’s columns: (1) constructional interface (masonry shafts vs. multi-drum stone with stucco), which sets the material vocabulary (lime-based injections and toothed masonry integrations for the former; joint restitution and local pinning for the latter); (2) slenderness/out-of-plumb and base damage, which gate the admissibility of passive restraints (only where demonstrably necessary and retractable); (3) safety-of-use versus visual legibility, to be reconciled through temporary, carefully detailed devices during works and through judicious, lightweight, low-impact consolidations that do not compromise the legibility of the architectural palimpsest or the full usability of the domus. These filters align with the broader recommendations—which warns against through-bars and cement grouts in historic columns and supports selective, reversible restraints when geometry and degradation demand it—and with the project’s methodological preference for minimally impacting, compatible, and maintainable interventions [33,43,46].

3.5.2. Mosaic Pavements

For in situ mosaics, the international literature is convergent on a preventive-first paradigm, anchored in maintenance planning and risk-proportionate protection (inventorying, performance-led shelter design, or reburial). The Getty MOSAIKON Overview of the Literature on Conservation of Mosaics In Situ documents both a global proliferation of shelters and a long list of cautionary tales where display imperatives trumped conservation, and it consolidates reburial as possible option when engineered, monitored, and embedded in site management [47,48]. Within MOSAIKON fieldwork, the Bulla Regia project (2010–2017) operationalized that agenda by pairing a GIS-based condition inventory and prioritization with lime-based, locally sustainable treatments and maintenance as design output—a template that is directly transferable to Arianna’s floors [49].

Here, best practice for the Domus’ mosaics is framed as a single, continuous workflow rather than a ladder of solutions. It begins with knowledge-led prevention and planned care, non-negotiable prerequisites for any later step. Concretely, this means maintaining an up-to-date, georeferenced inventory of all pavements in which each floor is characterized by decision-ready attributes (salt load, bedding detachment, water paths, exposure/insolation, future visitor pressure), so that priorities emerge from evidence rather than from opportunity. This approach mirrors the MOSAIKON emphasis on actionable inventories and echoes the Colosseum Park’s experience with risk-mapping for open-air pavements, where thermal stress and mass tourism demanded tiered maintenance and access strategies [47,50,51]. Within this framework, the maintenance plan is the true intervention: seasonal control of bio growth and drainage housekeeping are scheduled as routine tasks—vegetation management being the non-negotiable risk variable—and performance is tracked through simple visual and moisture indicators that can trigger corrective actions [47].

Given that the site already includes protective measures from past campaigns [37], the present guidelines explicitly exclude the addition of new shelters or reburial layers. The methodological focus shifts instead to optimizing the management of what exists [52]: calibrating cleaning cycles and access, refining drainage at thresholds and along run-off lines, and using the inventory to script inspections, renewals and small-scale adjustments. In other words, conservation outcomes are tied to a site management framework with clear triggers for inspection and renewal; experience across comparable contexts shows that ‘one-off’ fixes—however sophisticated—systematically fail without this governance backbone [47,53].