1. Introduction. Evolution of Nile Environmental History: From Correlation to Causation

The relationship between the Nile flood and Egyptian political history has fascinated observers since Herodotus. In fact, the direct connection between floods and political history was already clearly recorded in texts such as the Palermo Stone (ca. 2450 BCE) [

1]. Yet for most of this long historiography, the precise mechanisms linking environmental stress to societal change remained speculative, based on correlations between multi-century climatic trends and equally broad political historical narratives. This changed fundamentally with Barbara Bell’s landmark papers in the 1970s, which established a framework for understanding connections between disruptive Nile flooding and societal stress [

2,

3]. Bell’s work on the Old Kingdom collapse (c. 2200–2000 BCE) and Middle Kingdom instability demonstrated that prolonged droughts—manifested as repeated low Nile floods—could serve as triggers for political crises.

Karl Butzer extended this approach in the 1970s and 1980s, systematically identifying four major environmental anomalies between 3000 and 1000 BCE and correlating each with periods of political discontinuity [

4]. His framework treated environmental stress not as deterministic cause but as “co-agent” in historical change, working alongside political succession disputes, administrative inadequacies, and other factors. Yet Butzer himself acknowledged the limitations: his environmental anomalies were characterized at multi-decadal to century-long scales, making precise causal arguments difficult.

The Precision Problem. To move from correlation to causation—to establish that environmental stress triggered rather than merely coincided with political crises—requires precision at annual to decadal scales. Recent advances in paleoclimatology, particularly our understanding of volcanic forcing of the East African Monsoon, now make this possible. When large volcanic eruptions inject sulfate aerosols into the stratosphere, they disrupt atmospheric circulation patterns, including the monsoon systems that feed the Nile flood. These disruptions are precisely dated through ice core records and can be traced through their impacts on Nile River hydroclimate with unprecedented chronological accuracy.

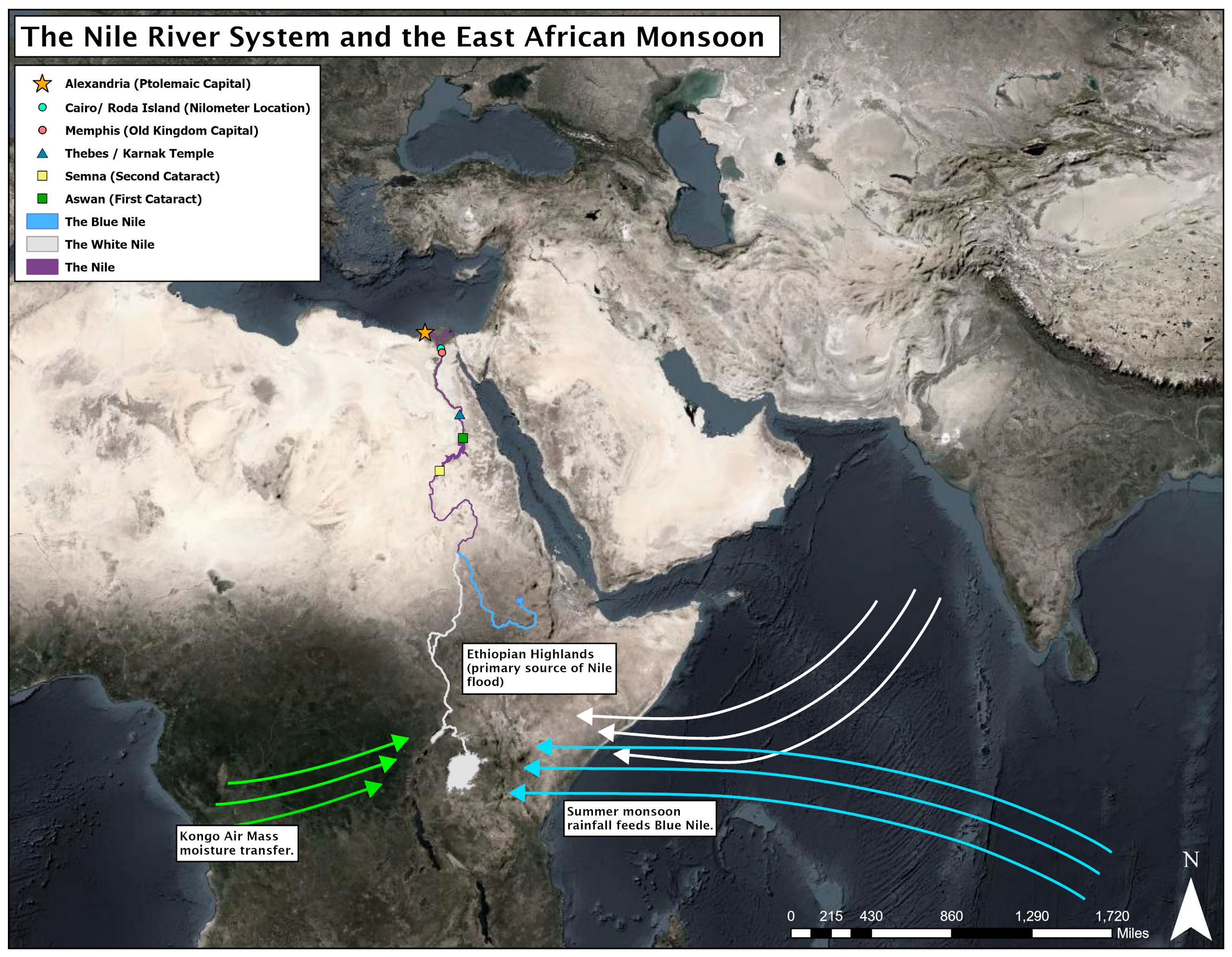

This paper presents a methodological framework for studying Nile environmental history that achieves annual to decadal resolution through a high-resolution ice core chronology that links explosive volcanic eruptions to the forcing of the East African Monsoon (

Figure 1). While debates continue about environmental determinism in climate history, the volcanic forcing methodology avoids this pitfall through the integration of precise natural and human records. By combining a volcanic chronology derived from ice core geochemistry, climate modeling, and Egyptian documentary evidence, this methodological framework achieves annual to decadal resolution through volcanic forcing mechanisms. We can now identify specific eruptions, trace their hydrological impacts, and document Egyptian responses with a precision unavailable to earlier generations of scholars.

Table 1 provides a chronological overview of major Egyptian periods and the environmental anomalies identified by previous scholars, situating the Ptolemaic focus of this study within the broader sweep of Egyptian history.

Environmental history of the Nile has evolved through three major phases, each achieving greater chronological precision. Barbara Bell’s textual analysis (1970s) established climate-society connections at century scales. Karl Butzer’s systematic framework (1970s–1980s) identified four major anomalies with multi-decadal resolution. Recent geochronological advances by Macklin and colleagues and geoarchaeological synthesis by Bunbury and Rowe achieved multi-decadal precision through radiocarbon dating and fluvial analysis [

5,

6]. Yet all faced the same fundamental limitation: insufficient temporal resolution to establish causation rather than correlation.

Figure 2 illustrates the evolution of these methodological approaches.

1.1. Barbara Bell and the Discovery of Climate-Society Connections

Barbara Bell’s landmark papers established that prolonged drought caused the Old Kingdom collapse (c. 2200−2000 BCE) and Middle Kingdom instability [

2,

3]. Her innovation lay in systematic analysis of Egyptian textual evidence: Ankhtifi tomb inscriptions describing extreme famine, the Admonitions of Ipuwer detailing social chaos, and nomarch stelae claiming to have fed districts during “years of low Niles” (

tzw, meaning exposed sandbanks). She interpreted

tzw as specific indicators of drought-induced famine, linking Egyptian collapse to simultaneous destructions across the eastern Mediterranean and the end of the “Neolithic Wet Phase.”

Her second paper proposed exceptionally high floods during the later Middle Kingdom (c. 1840−1770 BCE), analyzing Semna inscriptions recording floods 8–11 m above modern levels—three to four times normal volume. While groundbreaking in establishing climate as a serious historical factor, her work faced chronological limitations: dating relied on textual evidence with uncertainties of decades or more, and causal mechanisms remained theoretical.

1.2. Karl Butzer’s Systematic Framework

Karl Butzer’s work transformed Bell’s insights into a systematic framework identifying four major Nile flood anomalies between 3000 and 1000 BCE, each correlated with political discontinuity [

4]. His key theoretical contribution emphasized multiple causal pathways: environmental stress worked as “co-agent” alongside political succession disputes, administrative inadequacies, foreign invasions, and economic problems.

Table 2 summarizes Butzer’s four anomalies and their proposed societal impacts:

Butzer’s conception of Egyptian society emphasized dynamic equilibria—constant adjustments within a consistent framework, with multiple “layers” of buffering (technology, social organization, exchange) creating a high instability threshold but vulnerability when negative factors concatenated. His later work strongly criticized environmental determinism, arguing that societal collapse is multicausal, with environmental factors often secondary to sociopolitical variables [

7]. For the Old Kingdom, economic decline preceded collapse by ~160 years through tax exemptions and lost trade revenue; possible Nile failures triggered the final crisis, but institutional weakness was the primary precondition.

1.3. Recent Advances and the Persistent Precision Problem

Mark Macklin’s meta-analysis (2015) provided quantitative framework using radiocarbon and OSL dating of 115 fluvial units across the Nile catchment [

5]. Applying cumulative probability density functions and distinguishing floodplain versus paleochannel deposition, Macklin identified specific channel contraction phases and demonstrated inverse relationships between floodplain and paleochannel deposition. This work quantified timing of hydrological changes with unprecedented precision, showed regional variability, and revealed how civilizations adapted to environmental stress—the Old Kingdom flourished despite increasing aridity until c. 2200 BCE, suggesting remarkable resilience to gradual change but vulnerability to abrupt shifts.

Bunbury and Rowe’s geoarchaeological research (2021) provided crucial spatial context, demonstrating that environmental history requires understanding not only precise chronologies but also how hydrological changes operated at local and regional scales [

6]. Their five-stage Nile development model offers chronological markers aligning with political instability periods. Their analysis of channel migration rates (2–9 km per millennium) provides concrete mechanisms for how environmental changes affected state capacity. Their site-specific case studies from Memphis, Karnak, and Hierakonpolis demonstrate how macro-level climate changes translated into local political and economic effects. At Karnak, flood level changes affected temple operations and royal legitimacy, since the pharaoh’s ability to maintain cosmic order (

ma’at) was symbolically expressed through control of water [

8].

Yet even these advances achieved only multi-decadal resolution. Radiocarbon uncertainties (±50 years or more), fluvial depositional complexities, and challenges of correlating dispersed sites made year-to-year correlations impossible. This is the precision problem: to establish causation rather than correlation, to demonstrate that environmental stress triggered rather than merely coincided with political crises, requires resolution at annual to decadal scales.

The Research Gap. Despite progressive methodological refinement, Nile environmental history has lacked the temporal precision necessary to establish causation. Century-scale correlations between climate trends and political events cannot distinguish whether environmental stress triggered crises or whether political collapse caused apparent environmental degradation through reduced agricultural investment. Even multi-decadal resolution cannot determine temporal sequence with confidence sufficient for causal inference. The breakthrough comes from volcanic forcing of the East African Monsoon, which provides annual to decadal precision through ice core chronologies dated to specific years (±1–2 years).

3. Results: Volcanic Forcing and Ptolemaic Political Crises

3.1. Why Ptolemaic Egypt? The Advantages of Documentary Density

The Ptolemaic period (305–30 BCE) provides an ideal test case for the volcanic forcing methodology for several reasons. First, the documentary evidence from Ptolemaic Egypt is extraordinarily rich compared to earlier periods [

18]. The dry Egyptian climate preserved tens of thousands of papyri recording economic transactions, administrative communications, royal decrees, and private letters. This documentary density allows annual or even seasonal resolution for many types of evidence—grain prices, land sales, tax records, food distributions—providing the temporal precision necessary to correlate with volcanic events dated to specific years in ice core records.

Second, the Ptolemaic period experienced several major volcanic eruptions with well-established chronologies. The ice core records identify sixteen significant eruptions between 305 and 30 BCE, including a cluster in the 160s BCE and the major Okmok eruption in 43 BCE. These eruptions provide multiple opportunities to test whether volcanic forcing produced detectable impacts on Egyptian agriculture, economy, and political stability.

Third, Ptolemaic Egypt was a society particularly vulnerable to Nile flood variability. The Ptolemaic state extraction system depended heavily on agricultural surplus, specifically grain production. The Greek elite preference for free-threshing wheat—more vulnerable to drought than traditional Egyptian emmer wheat—increased the kingdom’s sensitivity to hydrological stress. The Ptolemaic fiscal system, with its monetization, banking institutions, and tax farming, created economic mechanisms that could amplify the effects of agricultural shortfalls through price inflation and credit disruptions.

Fourth, the Ptolemaic period was politically dynamic, experiencing both periods of strength (the third century BCE, when Ptolemaic Egypt was arguably the wealthiest and most powerful Hellenistic kingdom) and increasing instability (from the late third century onward, with recurring internal revolts, Seleukid conflicts, loss of imperial territory, and Roman pressure). This variation allows us to examine how the same magnitude of environmental stress affected Egyptian society differently depending on political and economic conditions—testing the resilience concept and avoiding environmental determinism.

Finally, the Ptolemaic period sits at a historiographical intersection where traditional historical methods, papyrological expertise, archaeological evidence, and paleoclimatic data can be integrated. We have the documentary precision to establish causation, the paleoclimatic data to identify environmental forcing, and sufficient historical context to understand the political and economic mechanisms linking environmental stress to societal response.

3.2. Establishing the Volcanic-Hydroclimate Connection

Before examining specific Ptolemaic political crises, we must establish that volcanic eruptions did indeed suppress Nile floods during this period. Direct evidence from later periods comes from Nilometer records. Comparing the Nilometer records from Roda Island (622–1902 CE) with ice core-based eruption chronologies reveals persistent reduction in the summer flood following large tropical and extratropical eruptions [

9]. Compositing annual Nile summer flood heights relative to sixty large eruptions between 622 and 1902 CE shows that flood heights were on average twenty-two centimeters lower in eruption years (

p < 0.01), with suppression often continuing into subsequent years. Climate models support this relationship.

Climate model output supports this relationship. Analyzing the ensemble mean precipitation minus evaporation (P-E) response to five twentieth-century volcanic eruptions in CMIP5 (Coupled Model Intercomparison Project 5) models shows significant drying across the Nile watershed during the first summer season that contained or followed the eruption, relative to the five summers preceding it. The spatial pattern shows strongest drying in the Ethiopian Highlands—precisely the region where monsoon rainfall feeds the Nile summer flood.

For the Ptolemaic period, we lack continuous Nilometer records but have qualitative flood assessments from papyri and inscriptions. Using the framework developed by Danielle Bonneau, we can create annual flood-quality ranks on an ordinal scale based on documentary references to flood conditions [

19]. When these qualitative indicators are analyzed statistically, flood quality tends toward lower ranks during volcanic years, confirming that the volcanic flood suppression effect observed in later instrumental and Nilometer data also operated during the Ptolemaic period.

The 238 BCE Canopus Decree provides particularly valuable evidence. This trilingual priestly decree, issued during the reign of Ptolemy III, explicitly discusses both flood failures and the royal response. The decree praises the king for opening granaries and importing grain during a period of insufficient Nile floods, preventing what could have been catastrophic famine. The decree’s reference to how such flood failures provoked “panic and fear as inhabitants recalled earlier episodes of crisis” demonstrates that Egyptians understood the potentially devastating consequences of repeated low floods, even when effective royal intervention prevented immediate disaster.

The causal pathway from volcanic eruption to Nile flood suppression can thus be established with confidence for the Ptolemaic period: (1) volcanic eruption injects sulfate into stratosphere [dated via ice cores]; (2) atmospheric circulation disrupted, monsoon weakened [demonstrated via climate modeling]; (3) reduced rainfall over Ethiopian Highlands [climate model output]; (4) Nile summer flood suppressed [evidenced in qualitative papyrological indicators and later Nilometer data]; (5) agricultural impact [documented in papyri through grain price changes, land sales, tax records].

3.3. Revolts and Volcanic Forcing: Statistical Evidence for Political Impact

With the volcanic-hydrological connection established, we can examine whether volcanic-induced flood failures triggered political crises. The most dramatic potential impact would be on internal revolts against Ptolemaic rule. The Ptolemaic period witnessed ten major revolts or periods of internal unrest, varying in duration, extent, and severity [

20]. Some touched the whole of Egypt and lasted twenty years; others were more short-lived and localized.

A striking pattern emerges: eight of ten revolt onsets occurred within two years of major volcanic eruptions—far exceeding the 0.6 coincidences expected by chance given sixteen eruptions across 275 years. Observing three coincidences already exceeds random expectation, and observing eight revolts within two years of eruptions is highly improbable under the null hypothesis of no relationship.

Statistical simulation confirms this. Randomly reassigning eruption dates to different years between 305 and 30 BCE, then counting correspondences with revolt onsets, and repeating this one million times, produces a reference distribution. The observed number of correspondences exceeds 98% of simulations, indicating p < 0.02—less than 2% probability that the pattern arose randomly. This meets the conventional scientific standard for statistical significance and supports the hypothesis that volcanic forcing increased revolt probability.

The causal mechanism linking flood failure to revolt is multi-stepped but plausible. Reduced flood → reduced agricultural yields → grain scarcity → price increases → difficulty paying taxes → economic distress → increased social tensions → higher revolt probability. This pathway is not deterministic—other factors matter enormously—but volcanic forcing acts as a trigger that can push an already-stressed society past a threshold into open revolt.

Several specific revolt episodes illustrate this mechanism [

20,

21]. The Great Theban Revolt (206–186 BCE) began during a period of documented low floods, following the cluster of eruptions in the 160s BCE. Papyrological evidence shows grain price inflation, tax collection difficulties, and population movements during this period. The revolt emerged in Upper Egypt, the region most dependent on the Nile flood for agriculture and most vulnerable to flood failures. While the revolt clearly had multiple causes—including ethnic tensions between native Egyptians and the Greek elite, resentment of Ptolemaic taxation, and weakness of the central government after expensive wars with the Seleukids—the volcanic-induced agricultural stress provided the trigger that transformed simmering discontent into open rebellion.

The revolt of Harsiesis (131–130 BCE) provides another example. Following documented flood failures in the early 130s BCE, this short-lived revolt erupted in the Theban region. While quickly suppressed, the revolt’s timing and location suggest environmental stress contributed to the outbreak. Papyri from this period document economic difficulties, and the revolt occurred in precisely the region where flood-dependent agriculture was most critical.

Importantly, not every volcanic eruption produced revolt. The methodology’s strength lies in explaining why some eruptions triggered political crises while others did not. The political and economic context mattered enormously. During the early Ptolemaic period (late fourth and early third centuries BCE), when the kingdom was wealthy, politically stable, and administratively competent, volcanic eruptions might cause temporary agricultural difficulties, but the state could respond effectively—importing grain, distributing food from royal granaries, temporarily reducing taxes. The 238 BCE Canopus Decree documents precisely this kind of successful state response.

By the late third and second centuries BCE, however, Ptolemaic Egypt faced multiple stresses: expensive wars with the Seleukids draining the treasury, ethnic tensions between Greeks and Egyptians, succession disputes within the royal family, loss of foreign possessions reducing revenue, and inflation eroding the value of silver coinage. In this context, the same magnitude of volcanic-induced agricultural stress that the early Ptolemaic state handled effectively could trigger revolt because the weakened state lacked resources for effective response.

This interaction between environmental forcing and societal conditions exemplifies what Butzer called “multicausal” explanation. Volcanic forcing was neither necessary nor sufficient for revolt—revolts could occur without volcanic triggers, and volcanic eruptions could occur without producing revolts. But volcanic forcing significantly increased revolt probability, particularly when other stresses were already present. The statistical evidence demonstrates this probabilistic causation: volcanic eruptions were associated with revolt onset at rates far exceeding chance, but the relationship was not deterministic.

3.4. Other Political and Economic Indicators

Beyond revolt onset, other types of recurring events show temporal associations with volcanic forcing, strengthening the case for environmental impact on Ptolemaic political economy.

Interstate warfare cessation: The Ptolemaic kingdom engaged in six major “Syrian Wars” with the Seleukid kingdom between 274 and 168 BCE, competing for control of Coele-Syria, Phoenicia, and the eastern Mediterranean [

22]. Of nine occasions when these conflicts ceased (either through peace treaties or military exhaustion), three fell in volcanic eruption years, with two more within two years and one within three years. This pattern suggests volcanic-induced agricultural stress constrained military capacity—armies require food supplies, military mobilizations require tax revenue, and both become difficult when floods fail and agricultural productivity declines.

The Second Syrian War (260–253 BCE) provides a specific example. This conflict ended following the eruption documented in ice cores for 257 BCE. While multiple factors surely contributed to the peace—military exhaustion, diplomatic calculations, domestic political considerations—the timing suggests environmental stress may have limited both kingdoms’ capacity to continue expensive military operations.

Priestly decrees: The Ptolemaic kings issued priestly decrees in Egyptian temples to legitimize their rule and maintain relations with the native Egyptian priesthood. These decrees were often issued during or after periods of crisis, representing royal efforts to maintain or reestablish political order. Of nine priestly decrees with secure dating, two were issued in volcanic eruption years, with one more in the year immediately following an eruption. This pattern is statistically significant (p < 0.05) and suggests that volcanic-induced crises prompted royal efforts to shore up legitimacy through religious and ideological means.

The Canopus Decree (238 BCE), already discussed, explicitly mentions flood failures and royal response. The Rosetta Stone (196 BCE), perhaps the most famous Ptolemaic priestly decree, was issued during a period of internal unrest following revolts and documents royal benefactions including grain distributions—suggesting response to economic stress potentially linked to agricultural difficulties.

Land sales: In Ptolemaic Egypt, hereditary land (γῆ ἐν ἀφέσει) was normally retained within families, and its sale was considered indicative of economic distress. Families resorted to selling hereditary land only when facing severe financial pressure. Eighty-four sales with sufficient dating precision (to within 5 years) can be identified in the papyrological record for the Ptolemaic period.

When land sales are plotted relative to volcanic eruption dates, a clear pattern emerges: Sales spiked upward for several years following eruptions. The increase begins in the eruption year, peaks 2–3 years after eruptions, and gradually returns to baseline by 5–6 years post-eruption. This temporal pattern is consistent with the expected economic impact of flood failures: immediate agricultural shortfall, followed by accumulated economic stress as families exhaust reserves and resort to land sales, then gradual recovery as floods return to normal.

Statistical analysis confirms significance: the number of land sales in the three years following eruptions significantly exceeds the number expected by chance (p < 0.01). This provides economic evidence complementing the political evidence from revolts and warfare—volcanic forcing impacted not only high politics but also the economic circumstances of ordinary Egyptians.

3.5. The 160s BCE Cluster: A Detailed Case Study

The cluster of volcanic eruptions in the 160s BCE provides an opportunity to examine the volcanic forcing mechanism in detail, as multiple eruptions occurred within a short period, potentially producing cumulative impacts [

23].

Ice core records identify major eruptions in 168, 164, and 161 BCE. Climate modeling suggests these eruptions, occurring in rapid succession, would have produced sustained disruption of the African monsoon, leading to multiple years of suppressed Nile floods. The cumulative effect of repeated eruptions would be more severe than a single eruption, as Egyptian society would have little opportunity to recover between shocks [

24].

The papyrological evidence from the 160s BCE documents cascading economic stress: grain prices doubled or tripled, tax arrears mounted, fields were abandoned, and populations migrated from rural areas to urban centers seeking food and economic opportunities.

The political impact was severe. The period witnessed intensified revolt activity in Upper Egypt, with insurgent forces controlling the Theban region for extended periods. Royal authority fragmented, with the central government unable to project power effectively into Upper Egypt. The Ptolemaic state responded with a combination of military suppression and economic concessions, but the weakness revealed by these crises marked a turning point in Ptolemaic history.

The 160s BCE cluster thus provides a clear example of how volcanic forcing can trigger cascading crises: environmental shock (repeated flood failures) → economic stress (agricultural shortfall, price inflation, fiscal crisis) → political instability (revolt, state weakness, territorial fragmentation) → social disruption (migration, abandonment, economic retrenchment). While each element of this cascade had multiple causes, the volcanic forcing provided the initial trigger that set the process in motion, and the rapidity of the succession of eruptions prevented recovery between shocks.

3.6. Understanding Non-Events: Why Some Eruptions Did Not Trigger Revolts

Understanding why some volcanic eruptions did not trigger revolts is as important as understanding why others did—revealing the factors determining societal resilience versus vulnerability. Of sixteen major volcanic events during the Ptolemaic period, eight were associated with revolt onset within two years, while eight were not. This variation provides crucial insights into the conditions modulating volcanic forcing effects.

Early Ptolemaic resilience (305–245 BCE). The early Ptolemaic period experienced several volcanic eruptions (including events in 274 and 257 BCE) without triggering major revolts. During this period, the kingdom was wealthy, politically stable, and administratively competent. The 238 BCE Canopus Decree documents successful state response to flood failures: “The king opened granaries, gave grain to the temples, imported grain from foreign lands, and prevented what might have been catastrophic famine.” The state possessed both resources and institutional capacity for effective crisis response.

Political legitimacy as buffer. The early Ptolemies enjoyed relatively strong legitimacy—Ptolemy II successfully navigated the hybrid Greek–Egyptian identity, maintained good relations with the Egyptian priesthood (as evidenced by priestly support in the Pithom Stela and other decrees), and demonstrated military competence in foreign wars. When volcanic eruptions caused agricultural stress, the population was more willing to accept temporary hardships if they trusted the ruler to respond effectively.

Fiscal capacity and granary reserves. The early Ptolemaic state maintained substantial grain reserves in royal and temple granaries, accumulated during good harvest years. These reserves provided buffer capacity to distribute food during crisis years. The sophisticated fiscal system, while sometimes burdensome, generated resources for crisis response. By the late Ptolemaic period, expensive wars, loss of foreign possessions, and fiscal crisis had depleted both reserves and state capacity.

Concurrent stresses determine vulnerability. The eruptions of 168 and 164 BCE occurred during a period of multiple stresses: expensive Syrian Wars had drained the treasury, ethnic tensions between Greeks and Egyptians were intensifying, succession disputes within the royal family created instability, and inflation was eroding coinage value. In this context, volcanic-induced agricultural stress that the early Ptolemaic state had handled effectively now triggered revolt because the weakened state lacked resources for effective response. The contrast demonstrates that volcanic forcing was not deterministic—outcomes depended critically on societal conditions.

This analysis of non-events supports the multicausal framework: volcanic forcing significantly increased crisis probability but was neither necessary nor sufficient for crisis. The same environmental stress magnitude produced different outcomes depending on state capacity, political legitimacy, fiscal resources, and concurrent pressures. This finding is crucial for avoiding environmental determinism while establishing environment as a real historical agent whose effects were modulated by human institutions and decisions

4. Discussion. Methodological Implications and Broader Applications

4.1. What Annual to Decadal Resolution Enables

The achievement of annual to decadal resolution through the ice core chronology of volcanic forcing fundamentally transforms what environmental history can accomplish. This precision enables four critical advances

Table 3.

First, temporal sequences can now be determined. With century-scale resolution, we cannot determine whether environmental stress preceded political collapse or whether political collapse led to reduced agricultural investment that appears in our records as environmental degradation. Did drought cause the Old Kingdom collapse, or did state weakness lead to irrigation system neglect that produced localized agricultural failure? With annual resolution, we can establish sequence definitively: volcanic eruption in year X, flood failure in year X or X + 1, grain price increase in year X + 1, revolt outbreak in year X + 2. The environmental stress demonstrably preceded the political crisis.

Second, statistical validation of hypothesized relationships becomes possible. With imprecise dating, we cannot distinguish real patterns from chance correlations. When both environmental events and political events are dated to “sometime in the third century BCE,” any correspondence might easily arise randomly. With annual dating, we can calculate precise probabilities: given sixteen eruptions randomly distributed across 275 years, what is the probability that eight revolts would occur within two years of eruptions purely by chance? The answer (less than 2%) provides quantitative support for causation rather than mere correlation.

Third, causal mechanisms can be identified. The volcanic forcing pathway provides a concrete, physically based mechanism: stratospheric sulfate → atmospheric cooling → monsoon disruption → reduced Nile flood → agricultural shortfall → economic stress → political crisis. Each step can be validated through independent evidence (ice cores, climate models, Nilometer records, papyri). This is fundamentally different from vague assertions about “climate change” causing “collapse.” We can specify exactly how environmental forcing propagated through social and economic systems to produce political outcomes.

Fourth, comparative analysis across different societal contexts reveals factors of resilience. By examining how multiple volcanic events affected the same society at different times (early versus late Ptolemaic Egypt) or how the same volcanic events affected different societies (Mediterranean versus Mesopotamian responses to the 43 BCE Okmok eruption), we can identify the factors that determined societal resilience versus vulnerability. This moves beyond simple environmental determinism to sophisticated analysis of human–environment interactions.

These four advances—temporal sequence, statistical validation, mechanistic understanding, and comparative analysis—collectively represent a methodological revolution in environmental history. They enable us to answer not merely whether environment mattered in history but precisely when, how, and under what conditions environmental forcing shaped historical trajectories.

4.2. Avoiding Environmental Determinism: The Multicausal Framework

The precision of volcanic forcing methodology creates a paradox: by establishing clear causal links between environmental events and political crises, it risks reinscribing the environmental determinism that historians have rightly rejected. The solution, now widely accepted, lies in a sophisticated multicausal framework that recognizes environmental forcing as one causal factor among many, but a factor whose timing and magnitude can be established with unusual precision.

The Ptolemaic evidence demonstrates that volcanic forcing was neither necessary nor sufficient for political crisis. Not every volcanic eruption produced revolt—the early Ptolemaic state successfully weathered environmental shocks that later triggered crises. Not every revolt followed volcanic eruptions—political succession disputes, military defeats, and ethnic tensions could trigger revolts independently. But volcanic forcing significantly increased crisis probability, particularly when other stresses are present.

This probabilistic causation can be formalized using the framework from epidemiology and public health. A risk factor increases the probability of an outcome without being strictly necessary or sufficient. Smoking increases lung cancer risk but does not always cause cancer (not sufficient) and cancer occurs in non-smokers (not necessary). Similarly, volcanic forcing increases revolt risk but does not always cause revolts (not sufficient) and revolts occur without volcanic triggers (not necessary).

The multicausal framework requires specifying how environmental forcing interacted with other causal factors. For Ptolemaic revolts, several background conditions modulated volcanic forcing impact: Political legitimacy mattered—when legitimacy eroded through succession disputes or military defeats, environmental stress could catalyze revolt. The Ptolemaic fiscal system was both strength and vulnerability—efficient tax collection provided crisis response resources but created resentment that amplified impacts when agricultural stress reduced farmers’ ability to pay taxes. External wars drained resources and manpower, so volcanic-induced agricultural stress could produce fiscal crisis and inability to suppress unrest. Population growth during prosperous periods increased vulnerability—the same harvest reduction magnitude affected larger populations more severely.

These background conditions were not themselves caused by volcanic forcing, but they determined how volcanic forcing translated into political outcomes. This is the essence of multicausal explanation: environmental forcing provided triggers whose effects depended critically on societal context.

The implication for environmental history methodology is clear: achieving precision in environmental forcing does not eliminate the need for traditional historical analysis of political, economic, and social factors. Rather, it enables more sophisticated integration of environmental and human factors by establishing exactly when environmental stress occurs and allowing precise examination of how societies responded given their particular circumstances.

4.3. Limitations, Uncertainties, and Future Research Directions

While volcanic forcing methodology represents a major advance, several limitations and uncertainties must be acknowledged:

4.3.1. Data Limitations and Biases

Documentary preservation biases. Papyri survival is not random—dry conditions in Upper Egypt preserved more documents than the Delta. Crisis periods might produce more documentation (petitions, complaints, administrative responses) or less (administrative breakdown, population flight). Urban centers with administrative archives are overrepresented relative to rural areas. These biases could create spurious correlations if documentation systematically clusters around certain periods or regions. The analysis partially addresses this by using multiple independent documentary categories from different archives, but some bias likely remains.

Chronological uncertainties. While ice core volcanic dating achieves ±1–2-year precision, documentary sources vary widely. Well-dated papyri with regnal year dates achieve ±1-year precision, but paleographically dated documents carry ±30–50-year uncertainties. Radiocarbon dates on archaeological materials have ±30–50-year uncertainties for this period. The statistical approach accounts for these uncertainties, but they constrain the ability to establish precise temporal sequences for some events.

Incomplete historical record. Many potential events—local famines, small-scale revolts, economic stress in rural areas—likely went unrecorded. The analysis focuses on major events (large revolts, interstate wars, royal decrees) that achieved documentation, potentially missing important smaller-scale impacts. This creates bias toward spectacular crises rather than slow-developing pressures.

4.3.2. Methodological Uncertainties

Climate model limitations. Current climate models capture broad patterns of volcanic impacts on monsoons but lack spatial resolution to predict localized impacts with high confidence. Models are validated against instrumental-era eruptions, but pre-instrumental validation is limited. Different model formulations produce somewhat different results, creating uncertainty about magnitude (though not direction) of volcanic effects. Higher-resolution regional climate models specifically designed for historical periods would improve precision.

Volcanic magnitude uncertainties. Ice cores provide excellent eruption dating but magnitude estimates carry uncertainties. Sulfate deposition in ice depends not only on eruption magnitude but also on eruption location, season, and atmospheric circulation patterns. Some large eruptions may be underestimated in ice core records, while some smaller eruptions may be overestimated. This creates uncertainty about which eruptions would have most strongly affected the Nile watershed.

Regional climate heterogeneity. Volcanic effects on monsoon rainfall show spatial variability—some eruptions strongly affect Ethiopian Highlands while others affect broader regions differently. The Nile watershed is large (~3 million km2) with different sub-regions (White Nile, Blue Nile, Atbara) contributing differently to the summer flood. Climate models provide spatial resolution (~100–200 km), but finer-scale heterogeneity remains uncertain. This limits ability to predict which specific regions would be most affected by particular eruptions.

4.3.3. Future Research Directions

Improved climate modeling. Higher-resolution regional climate models specifically designed for the Ptolemaic period and validated against proxy data would improve ability to translate volcanic forcing into specific agricultural impacts for particular regions. Ensemble approaches using multiple models could quantify uncertainty ranges. Coupling climate models with crop models would enable estimation of agricultural yield impacts rather than relying on indirect evidence. Future work integrating detailed hydraulic and hydrological modeling with this climate forcing framework promises to further refine our understanding of how volcanic events translated into specific flood patterns and agricultural impacts in ancient Egypt [

25,

26].

Expanded documentary analysis. Systematic analysis of additional papyrological categories—tax arrears, credit transactions, migration patterns, wage rates—could reveal additional dimensions of volcanic forcing impacts. Machine learning approaches to papyrus transcription and analysis could enable larger-scale quantitative studies, potentially identifying patterns not visible in current sample sizes.

Archaeological validation. While this methodology focuses on documentary evidence, archaeological data could provide independent validation and reveal impacts on populations leaving limited written records. Settlement abandonment patterns, dietary shifts in skeletal remains, changes in craft production, and fortification construction might all respond to volcanic-induced economic stress, providing evidence complementing documentary sources.

Comparative study design. Systematic comparison of how different societies responded to the same volcanic events would reveal institutional and cultural factors determining resilience versus vulnerability. The 43 BCE Okmok eruption, for example, affected Ptolemaic Egypt, Republican Rome, Han China, and Parthian Mesopotamia simultaneously. Comparing responses across these societies would identify generalizable principles about human–environment interactions.

Integration with social science theory. Frameworks from resilience theory, complex systems analysis, institutional economics, and political science would strengthen causal understanding. Why do some institutions fail under environmental stress while others adapt? How do informal social networks buffer environmental shocks? What are the thresholds beyond which adaptation fails and transformation occurs? Environmental history methodologies informed by social science theory can address such questions with increased sophistication [

27].

4.4. Replicability and Extension to Other Regions and Periods

The volcanic forcing methodology is replicable and extensible in ways that earlier environmental history approaches were not. This replicability rests on three foundations: the global coverage of volcanic forcing, the precision of ice core chronologies, and the existence of comparable documentary sources in multiple historical contexts.

Volcanic forcing is global. Large tropical eruptions affect atmospheric circulation patterns worldwide. Northern hemisphere high-latitude eruptions affect monsoon systems across Asia and Africa. Any historical society dependent on rainfall-fed agriculture or monsoon-fed rivers experienced volcanic forcing impacts. The same volcanic events that affected Ptolemaic Egypt also affected Han China, Mauryan India, Republican Rome, and Parthian Mesopotamia.

Ice core chronologies are continuously improving. The synchronization of multiple ice cores from Greenland and Antarctica now provides volcanic forcing histories extending back thousands of years with one-to-two-year precision. As ice core science advances—with better drilling techniques, higher-resolution sampling, and improved dating methods—the chronologies improve. Current projects aim to extend high-precision volcanic chronologies back through the entire Holocene.

Documentary sources exist in multiple contexts. Documentary sources from Mesopotamian, Chinese, Roman, medieval European, and Islamic contexts each offer distinct advantages—meteorological observations, astronomical data, administrative detail—enabling adaptation of the volcanic forcing methodology across diverse historical settings

Researchers are already pursuing several lines of new research elsewhere:

Mesopotamia: The Babylonian astronomical diaries (seventh to first centuries BCE) provide systematic daily observations of weather, astronomical phenomena, and commodity prices. The overlap with Ptolemaic Egypt allows comparison of how different societies responded to the same volcanic events. Preliminary work shows that volcanic eruptions correlating with Ptolemaic revolts also correlate with price spikes and conflict in Babylonian records, suggesting common environmental forcing with divergent societal responses depending on political and economic institutions.

Rome: The extensive documentation of the Roman Republic and Empire, combined with archaeological evidence, allows examination of how volcanic forcing affected Roman expansion, crisis management, and eventual transformation. The 43 BCE Okmok eruption, for example, occurred during the critical transition from Republic to Empire, affecting agriculture across the Mediterranean during the period of civil wars following Caesar’s assassination. The environmental stress may have amplified the political instability, contributing to the collapse of the Republican system.

China: Chinese dynastic records contain extensive meteorological observations, harvest reports, and documentation of social unrest. The volcanic forcing methodology could test hypotheses about environmental triggers for dynastic transitions, peasant rebellions, and the “dynastic cycle” pattern of Chinese history. The precision would be particularly valuable given the contentious debates about climate’s role in Chinese history.

Medieval Europe: The Irish annals example discussed in Izdebski et al. demonstrates successful application to medieval Europe [

27]. The methodology could be extended to other medieval societies using monastic chronicles, manorial records, grain price data, and archaeological evidence. The precision would help resolve debates about the role of climate in events like the medieval settlement of Iceland and Greenland, the Great Famine of 1315–1317, or the Black Death’s socioeconomic impacts.

Islamic world: Islamic astronomical observatories produced systematic observations potentially recording volcanic atmospheric effects (dust veils, unusual optical phenomena). Combined with agricultural records, tax registers, and chronicles documenting social unrest, these could enable volcanic forcing analysis of critical periods like the Abbasid decline, Fatimid Egypt’s crises, or Mamluk responses to environmental stress.

Each case study requires careful attention to the specific characteristics of documentary evidence, the particular environmental vulnerabilities of each society, and the political and economic mechanisms through which environmental stress propagated. But the core methodology—precise volcanic chronologies from ice cores, climate modeling to establish impacts, documentary evidence of societal responses, statistical validation of patterns—remains constant across applications.

4.5. Integration with Other Paleoenvironmental Proxies

While volcanic forcing provides exceptional temporal precision, it captures only one type of environmental variability: short-term (1–5 year) cooling and hydroclimate disruption following explosive eruptions. A comprehensive environmental history requires integrating volcanic forcing with other paleoenvironmental proxies that capture different types and timescales of environmental change.

Speleothem oxygen isotopes provide continuous records of hydroclimate variability at decadal to centennial scales. Unlike volcanic forcing, which produces abrupt short-term disruptions, speleothem records capture longer-term trends in precipitation and monsoon strength. For Nile history, speleothems from Northeast Africa and the Levant can identify multi-decadal periods of drought or enhanced precipitation that conditioned societal vulnerability to volcanic shocks. A volcanic eruption during a long-term wet period might have minimal impact; the same eruption during a multi-decadal drought could be catastrophic.

Tree-ring width and density measurements provide annual-resolution records of growing season temperature and moisture availability. Mediterranean tree-ring chronologies now extend back millennia, offering independent validation of volcanic cooling impacts and capturing non-volcanic climate variability. For regions with suitable tree preservation, dendrochronology can provide year-to-year climate reconstruction matching the temporal precision of volcanic forcing but capturing the full range of climate variability, not just volcanic perturbations.

Lake and marine sediments analyzed for multiple proxies (pollen, charcoal, geochemistry, biomarkers) provide local to regional environmental histories capturing vegetation change, erosion patterns, fire regimes, and human land-use impacts. As demonstrated by the medieval history of Greater Poland, palynological evidence of agricultural expansion or contraction can be correlated with historical documentation of settlement establishment, providing independent validation of economic trends and revealing dynamics not captured in written sources alone [

27].

Nile sedimentological records from the delta and floodplain, analyzed using the Bunbury and Rowe methodologies, provide geomorphological context for understanding how hydrological changes translated into local environmental impacts. Channel migration, sedimentation patterns, and delta evolution operated on longer timescales than volcanic forcing but determined where and how volcanic-induced flood failures would impact agriculture, settlement, and infrastructure.

The integration of multiple proxies enables several methodological advances:

Distinguishing volcanic from non-volcanic variability: Convergence across tree rings, speleothems, and ice cores confirms volcanic forcing. Divergence—ice cores showing eruptions without tree-ring cooling—reveals regional variability. Tree-ring cooling absent from ice core records identifies non-volcanic climate variability.

Establishing baseline conditions: Longer-term proxies like speleothems establish the baseline climate conditions against which volcanic perturbations occurred. A “normal” flood during a wet phase might represent a severe drought during a dry phase. Understanding baseline conditions is essential for assessing the severity of volcanic impacts.

Validating causal mechanisms: When multiple independent proxies (ice cores, tree rings, speleothems, Nile sediments) all show consistent patterns correlated with historical events, our confidence in causal mechanisms increases substantially. Convergence of evidence from diverse sources, each with independent uncertainties, provides stronger support than any single proxy.

Extending temporal coverage: While ice core volcanic chronologies are remarkably complete, other proxies fill gaps and extend coverage to regions or periods where volcanic forcing alone provides insufficient information. The combination enables comprehensive environmental reconstruction across timescales from annual (volcanic forcing, tree rings) to decadal (speleothems) to centennial (lake sediments, geomorphology).

The methodological challenge lies in handling the different temporal resolutions, spatial scales, and uncertainties of diverse proxies. A tree-ring measurement has annual resolution but typically ±1-year dating uncertainty from cross-dating procedures. A radiocarbon date on lake sediment might have ±30–50-year uncertainty. An ice core volcanic date has ±1–2-year uncertainty. A papyrus might be dated to a specific regnal year (precise to ±1 year) or might be dated paleographically (±50 years). Statistical methods must account for these varying uncertainties when integrating diverse evidence.

4.6. Implications for Contemporary Climate Policy

The volcanic forcing methodology’s demonstration that precisely dated environmental shocks triggered historical political crises carries implications for contemporary climate policy, though these must be articulated carefully to avoid misuse. It must be stressed that volcanic forcing provides a model for short-term shocks but that longer-term anthropogenic climate change differs in its persistent, cumulative character.

First, the historical evidence carries multiple implications. Sophisticated societies remain vulnerable to environmental shocks—Ptolemaic Egypt’s wealth and administrative capacity did not immunize it against volcanic impacts. Yet societal responses determine outcomes. Ptolemaic Egypt was not a “primitive” society vulnerable to environmental stress due to lack of knowledge or technology. It was one of the wealthiest, most technologically advanced, most administratively sophisticated societies of its era. Yet volcanic-induced harvest failures still triggered unrest, fiscal crises, and political instability. This contradicts naive optimism that modern technology and institutions render us invulnerable to environmental shocks.

Second, the evidence demonstrates that societal responses matter enormously. The same magnitude of environmental stress produced different outcomes depending on political legitimacy, fiscal capacity, and institutional effectiveness. Early Ptolemaic Egypt weathered environmental shocks successfully; late Ptolemaic Egypt experienced cascading crises from similar shocks. This demonstrates the importance of building resilient institutions, maintaining fiscal reserves, and ensuring political legitimacy—all factors that determine whether societies can respond effectively to inevitable environmental stresses.

Third, the historical evidence reveals that environmental shocks interact with other stresses in nonlinear ways. A volcanic eruption during peacetime was manageable; during expensive wars, it could trigger fiscal crisis. A harvest shortfall during political stability was surmountable; during succession disputes, it could catalyze revolt. This demonstrates the danger of multiple concurrent stresses—climate change, political polarization, economic inequality, pandemic disease—creating conditions when environmental shocks trigger cascading failures.

Fourth, the precision of volcanic forcing reveals that even short-term environmental variability matters. We often focus on long-term climate trends (decadal or longer), but the Ptolemaic evidence shows that even one-to-three-year agricultural disruptions can trigger major political and economic crises. This has implications for climate change adaptation: societies must prepare not only for gradual trends but also for the intensified short-term variability that climate change produces—more extreme droughts, floods, and heat waves even if average conditions change gradually.

However, the implications must not be overstated or misused. The historical evidence does not support environmental determinism or collapse narratives that ignore human agency. Societies responded differently to similar environmental stresses; effective governance mitigated impacts; institutions adapted and survived. The evidence supports neither fatalism (“climate determines history; we’re doomed”) nor complacency (“past societies survived climate stress; we’ll be fine”). Rather, it supports vigilance: environmental stress is real, impacts are serious, but effective societal responses can successfully navigate environmental challenges.

The distinction between the modern situation and historical cases must also be emphasized. Modern anthropogenic climate change differs fundamentally from natural volcanic forcing: it is longer-term, affects baseline conditions rather than producing temporary perturbations, and is potentially reversible through human action. Historical volcanic eruptions were exogenous shocks beyond human control; modern climate change is endogenous, produced by human activities and potentially mitigated by changing those activities. The historical evidence demonstrates that environmental forcing matters—it should motivate climate action, not justify fatalism.

4.7. Future Directions: Methodological Refinements and Extensions

Future research should continue to build on recent work.

Improved climate modeling: Current climate models capture broad patterns of volcanic impacts on monsoons and hydroclimate but lack the spatial resolution to predict localized impacts with high confidence. Higher-resolution regional climate models, specifically designed for historical periods and validated against proxy data, would improve our ability to translate volcanic forcing into specific agricultural impacts for particular regions.

Expanded documentary analysis: The Ptolemaic application focused primarily on grain prices, land sales, and revolt dates. Systematic analysis of additional papyrological categories—tax arrears, credit transactions, migration patterns, wage rates, testamentary dispositions—could reveal additional dimensions of volcanic forcing impacts on economy and society. Machine learning approaches to papyrus transcription and analysis could enable larger-scale quantitative studies.

Archaeological validation: While this methodology focuses on documentary evidence, archaeological data could provide independent validation and reveal impacts on populations that left limited written records. Settlement abandonment patterns, dietary shifts visible in skeletal remains, changes in craft production, and fortification construction might all respond to volcanic-induced economic stress, providing evidence complementing documentary sources.

Comparative study design: Systematic comparison of how different societies responded to the same volcanic events would reveal the institutional and cultural factors determining resilience versus vulnerability. Why did some societies experience revolt while others maintained stability? What governance structures, economic systems, or cultural practices enabled effective crisis response? Such comparative analysis would move beyond single-society case studies to identify generalizable principles.

Extension to other forcing mechanisms: While volcanic forcing provides exceptional precision, other environmental forcings also matter: ENSO variability, solar radiation changes, non-volcanic drought, flooding from excessive monsoon rainfall. Methodologies developed for volcanic forcing—statistical validation, multi-proxy integration, mechanistic causal pathways—could be adapted to these other forcings, building a comprehensive environmental history framework capturing the full range of climate variability.

Synthesis with social science theory: Integration with theoretical frameworks from resilience theory, complex systems analysis, institutional economics, and political science would strengthen causal understanding. Why do some institutions fail under environmental stress while others adapt? How do informal social networks buffer environmental shocks? What are the thresholds beyond which adaptation fails and transformation occurs? Environmental history methodologies informed by social science theory can address such questions with increased sophistication.

5. Conclusions

The evolution of Nile environmental history from Bell’s pioneering textual analysis through Butzer’s systematic framework to Macklin’s geochronological meta-analysis and Bunbury and Rowe’s geoarchaeological synthesis represents progressive methodological refinement. Each generation achieved greater precision, more robust chronologies, and more sophisticated understanding of human–environment interactions. Yet even these advances faced the fundamental challenge of temporal resolution: establishing causation requires determining sequence, and determining sequence requires precision at annual to decadal scales.

Volcanic forcing of the East African Monsoon provides this precision. Ice core chronologies date eruptions to specific years with ±1–2-year uncertainty. Climate models establish how eruptions disrupted monsoon circulation and suppressed Nile floods. Documentary sources record Egyptian responses—grain price inflation, land sales, revolts—with annual or even seasonal resolution. Statistical methods validate that observed temporal associations between eruptions and crises exceed chance expectations, supporting causal inference rather than mere correlation.

The Ptolemaic case study demonstrates this methodology’s potential. Sixteen major volcanic eruptions between 305 and 30 BCE correlate with revolt onsets, warfare cessations, priestly decrees, and land sales at rates far exceeding chance expectations (p < 0.02 to p < 0.05). The mechanisms linking eruptions to political crises—atmospheric disruption → monsoon weakening → flood suppression → agricultural shortfall → economic stress → political instability—can be validated through multiple independent lines of evidence. The variability in impacts—early Ptolemaic resilience versus late Ptolemaic vulnerability—demonstrates how societal conditions modulated environmental forcing effects, avoiding environmental determinism while establishing environment as a real historical agent.

This methodology is replicable and extensible. The same volcanic events affected multiple societies, enabling comparative analysis. Ice core chronologies continuously improve, extending high-resolution forcing histories deeper into the past. Documentary sources from diverse cultures allow adaptation of the methodology to different historical contexts [

27]. Integration with other paleoenvironmental proxies—tree rings, speleothems, lake sediments—enables comprehensive reconstruction of environmental variability across multiple timescales.

The implications extend beyond Nile history or even environmental history broadly. The methodology demonstrates that sophisticated integration of natural scientific and historical evidence can achieve causal understanding previously considered impossible for preindustrial periods. It shows how quantitative methods—statistical validation, climate modeling, multi-proxy integration—can complement rather than replace traditional historical analysis. It reveals that environmental forcing mattered in history: not deterministically, not exclusively, but significantly and demonstrably, shaping the trajectories of even the most sophisticated ancient societies.

As historians engage with the current climate crisis, understanding how past societies responded to environmental stress takes on contemporary urgency. The volcanic forcing methodology offers neither comforting precedents of inevitable resilience nor fatalistic narratives of collapse. Rather, it demonstrates that environmental challenges are real and consequential, that societal responses matter enormously, and that effective institutions and governance can successfully navigate environmental stress while weak institutions fail catastrophically. These are lessons, drawn from rigorous analysis of ancient evidence, that resonate powerfully in the present [

28,

29].