Abstract

This study provides one of the largest samples of ceramic building materials with prints that has been analyzed. These tiles were recovered from Braga and date between the 1st and 7th centuries CE. There were 152 tiles examined with 420 prints from humans, dogs, cats, sheep, and goats. All prints were measured to provide data to estimate the morphological aspects of the animals found. The most common prints were from dogs that were small and medium in size. Only a few cat prints were present, but this helps us to understand the spread of this domesticated animal. The presence of sheep and goats suggests small settlements and farms once existed near the tilery. The human prints included both bare foot and shoe prints. The age, sex, and stature of the human prints were estimated, and indicate that women and children were present in the tile drying area. The children were 1 to 10 years of age. The stature of the adult females averaged 151.2 cm, which compares favorably with stature estimates from other areas of Portugal during the Roman period. Animal prints on CBM are commonly found but rarely published. Providing this data can aid future research on the comparability of the environment and animals around different tileries in the Roman world.

1. Introduction

Archeological excavations in Braga, Portugal have resulted in the recovery of many Roman period artifacts. This paper describes the 152 pieces of ceramic building materials (CBM) that had 420 animal prints from humans, dogs, cats, sheep, goats, and birds. The CBM included various architectural bricks and tiles.

Braga in the Roman period was known as Bracara Augusta. Bracara Augusta was an important Roman city founded by the Emperor Augustus late in the 1st century BCE. The city was an important political and administrative center that helped to integrate members of the indigenous population into the administrative staff, facilitate urban integration, and contribute to the Romanization of the region. Between the end of the 1st century and the early 2nd century CE, Bracara Augusta was systematically populated. The indigenous elites became the urban aristocracy. Other immigrants were attracted to the area and included craftsmen, administrators, and military officers. They were responsible for urban planning, building the infrastructure for water and sanitation, and for implementing the road system. Most of the public Roman buildings were constructed during this time period. With the extensive road and river system, Bracara Augusta was an important center in the region for importing, producing, and redistributing goods. With the Diocletian reforms in the 3rd century CE, Bracara Augusta became simply Bracara and was the capital of the province of Gallaecia. The city wall was constructed in the 3rd century, and many buildings were remodeled. After the decline of Roman influence in the 5th and 6th centuries, Braccara became the capital of the Suebi Kingdom, which was absorbed by the Visigoth Kingdom in 585 CE [1,2,3].

Footprints on CBM are often found but are not often reported on in published papers. The study of these marks provides a unique opportunity to know what animals were in and around the tileries. They offer a glimpse of the environment of the area, human and animal interactions, and the seasonality of production. The area of Braga has soil that is acidic in composition, and few organic remains are found from the Roman period [4]. The study of these prints offers an alternative means to understand the animals present and everyday life at the tilery.

2. Materials and Methods

The human and animal prints were a result of the people and animals that were in the tilery, or brick workshop, where these building materials were produced. CBM were constructed by molding clay using wooden forms, letting them dry in the sun, and then firing them. It is during the drying cycle that they were subject to animals and humans walking on them and thereby leaving their impressed footprints. The CBM included pedalis, bipedalis, lydion, tegula, and sections of ceramic drains. Several of the CBM were complete or nearly complete, but the majority were fragmented. The surface of the CBM were occasionally damaged from use, re-use, disposal, recovery excavations, or through a combination of all of these. The CBM varied in form and overall condition. The impressions became a permanent part of the tile when it was fired. Some of the prints were deeply impressed, but this did not seem to deter the firing process or supposedly the use of that brick or tile. These CBM were then used in public and private structures in and around Bracara Augusta.

The CBM examined were from 16 different sites in Braga that date from the early 1st century to the 7th century CE [3]. These sites are a variety of public and private structures and necropolises that are in and around Braga. Table 1 shows the sites and the number of tiles that were examined. The site with the greatest number of tiles examined was the necropolis Via XVII Avenida Liberdade with 51 pieces, or 33.6 percent of the total (shown in bold in the table). Largo Carlos Amarante necropolis, Carvalheiras, and Cangosta Palha necropolis each had 20 to 16 pieces (13.2 to 10.5 percent of the sample). The remaining sites had only a few pieces each.

Table 1.

Number of tiles examined by site.

Animal marks were identified by the type of animal and measurements were recorded. Measurements included the length, width, and depth of the impression, and, on occasion, the stride length of the animal could also be measured. The CBM included one or more animals and often there were multiple prints from one or more animals. All prints were recorded, even when not complete. Identification was occasionally complicated, because the impression was not always completely clear, was not deep enough to clearly show all the pertinent print characteristics, was obscured by other footprints, or was incomplete because of the fragmentation of the tile or brick. Identification as to the species was aided by several resources [5,6,7,8].

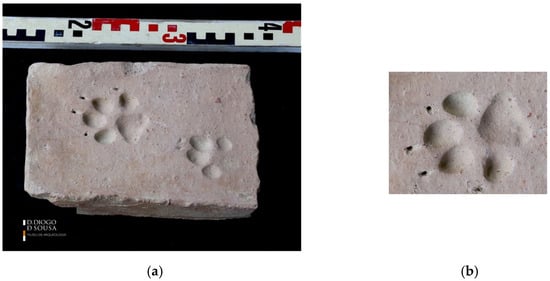

For the dog prints, the maximum length was recorded from the farthest point of the claw mark to the end of the pad. The maximum width was recorded from the farthest edge of the toe prints—medial to lateral. Dog prints, when complete enough, were also identified as to being a fore foot or a hind foot [7]. The distinguishing characteristics are in the arrangement of the toes. Figure 1 shows an example of a fore foot and shows multiple prints from one dog. Figure 2 shows an example of a hind foot, again with multiple prints from one dog. Fore feet have the toes more spread out, and hind feet have the toes more clustered together.

Figure 1.

Dog Fore foot (©MADDS/n.ºinv.2024.0637/Felismina Vilas Boas). (a) Entire tile fragment; (b) Detail of fore foot.

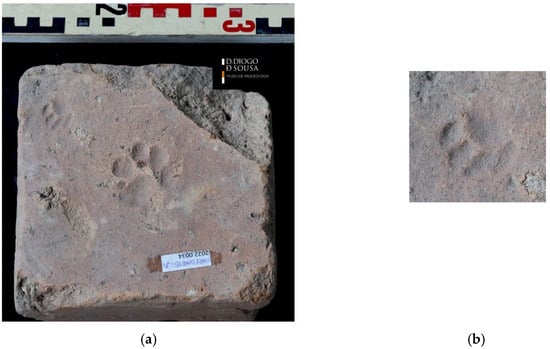

Figure 2.

Dog hind foot (©MADDS/n.ºinv.2024.0245/Felismina Vilas Boas). (a) Entire tile fragment; (b) Detail of hind foot.

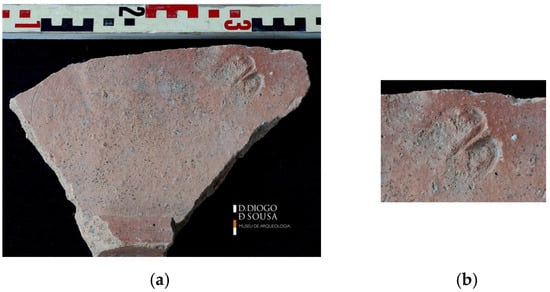

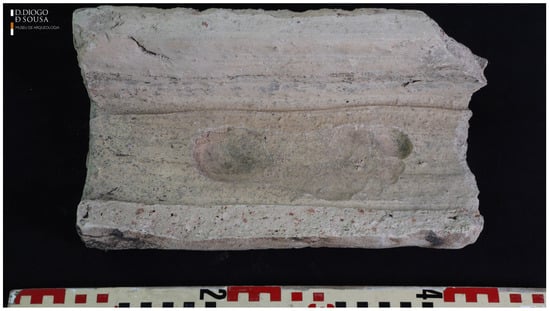

A similar method of measurement was applied to the recording of the cat footprints, although for cats, no claw marks are present. Length was from the farthest toe print to the end of the pad. Width was recorded medial to lateral across the greatest distance for the toes. Cat and dog prints differ in not only the lack of claw marks for the cats, but also by the shape of the paw print (Figure 3). Cat prints are more rounded. The negative space between the toes and pad are shaped differently with the cat having a more upside down “U” shape and the dog having a more upside down “V” shape [8].

Figure 3.

Cat footprint (©MADDS/n.ºinv.2022.0034/Felismina Vilas Boas). (a) Entire tile; (b) Detail of print.

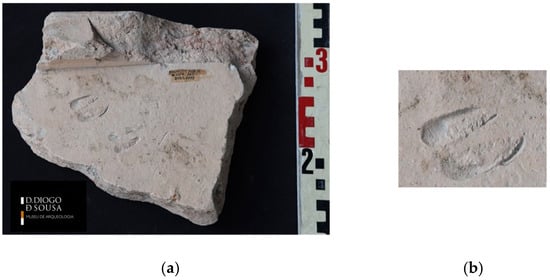

Sheep and goat prints were commonly found. These animals have a print with cloven hooves. The gap between the two halves is one identifying characteristic. For goats, the negative space is more flared (“V”-shaped) and in sheep, it is more parallel. The overall shape of a sheep hoof is more oval, and in goats, especially in the shape of each half, it is more kidney-shaped [7,8]. Figure 4 shows an example of a sheep print and Figure 5 shows a goat print. With the sheep/goat prints, not all of the hoof print was impressed on the tiles. Often the front part of the toe was impressed but not the bottom arch. Measurements for length are from the tip of the toe to the end of the bottom arch. The width is the maximum measurement across both halves of the hoof, which generally occurs near the base for goats and nearer to the center for sheep. Often there were multiple prints which overlapped, and this made identification difficult because the two parts of the cloven hoof were not easily matched.

Figure 4.

Sheep footprint (©MADDS/n.ºinv.2024.0599/Felismina Vilas Boas). (a) Entire tile fragment; (b) Detail of print.

Figure 5.

Goat footprint (©MADDS/n.ºinv.2024.0773/Felismina Vilas Boas). (a) Entire tile fragment; (b) Detail of print.

A few prints from birds were found on these tiles. These prints were rarely complete. The bird prints did not impress into the wet tile surface well. Measurements were taken of the overall length and width. Each toe was also measured. Bird feet often have four toes, with the first toe to the rear and the other three toes pointing forward. Toes are numbered starting with the rear toe as I, then the forward toes are numbered as II, III, and IV. Some birds also have a metacarpal pad (Figure 6). Claws are at the end of the toes for some birds, and some birds have webbing between the toes. All these characteristics were recorded when present to aid in identifying the bird. Measurements and identification were completed following the methods in published sources [5,6]. Figure 6 shows multiple bird prints along with multiple dog prints.

Figure 6.

Bird footprint (©MADDS/n.ºinv.2024.0304/Felismina Vilas Boas). (a) Entire tile; (b) Detail of print.

Marks and prints were also found from humans. There are a few marks that could be from a hand or fingers. There are bare footprints and shoe prints. The shoe prints were identified by the hob nails. Human prints included adults and subadults. An article by Marado and Ribeiro [9] was published in 2018 with human footprints from Bracara Augusta. To be comparable to that study, the current study recorded measurements in the same manner.

3. Results

The 152 tiles and bricks examined had 420 prints from humans and other animals (Table 2). Almost half of these prints (49.5 percent) were from the domestic dog. This is followed closely by sheep and goats. If sheep, goats, and those that were indeterminate between sheep and goat are added together, they form 172 prints, or 41 percent of the sample. The remaining prints are six from domestic cats, five from birds, two unknown, and twenty-seven that are or could be human.

Table 2.

Number of Prints by Animal.

3.1. Domestic Dog

The most common animal prints were those of the domestic dog. Many of the dog prints were overlapping. In some tiles, the positioning of the prints showed the manner of movement, and that the hind feet were often over or near the fore feet when walking or trotting. Stride length varied, with the shortest strides being 10–12 cm and the longest being 25 cm. The most common stride length was between 14 and 19 cm. Of the 208 dog prints, 77 (37 percent) were fore feet, 73 (35.1 percent) were hind feet, and 58 (27.9 percent) could not be identified as to which foot.

The complete or near complete fore feet measured between 3.3 and 6.4 cm in length. The widths of the fore feet were between 3.0 and 7.0 cm and the majority were between 4.0 and 5.5 cm. The lengths of the complete or near complete hind feet were between 4.0 and 8.0 cm. The hind feet were 2.5 to 6.0 cm in width, with most in the range of 3.0–5.0 cm in width.

In terms of the size of the dogs, there appeared to be small- and medium-sized dogs. Based on modern dogs, general dog sizes are classified as large, medium, small, and tiny. A medium size dog would include modern breeds such as Labradors, Beagles, and Border Collies, with a footprint of 6.35–10.16 cm in length and 5.08–7.62 cm in width. Modern small dogs would include modern breeds of Pekingese, Bulldogs, and Yorkshire Terriers, and have footprints of less than 6.35 cm in length and less than 5.08 cm in width. The modern information on the size of dogs does not consider the difference in the size of the fore and hind feet.

To estimate the size of the dogs from this study, length was not used, because it was often incomplete. Width was more often complete and was used to estimate size. There is a considerable amount of overlap in the size and no clear break to help distinguish between small and medium sized dogs. Using an arbitrary break point at the width of 5.0 cm (±2.5 cm), as per the modern dog size range, resulted in 34 prints in the small dog size, 21 in the medium range, and 11 in the indeterminate range. There are many variables that affect the size of the footprint, including the shrinkage of the tile while drying, the gait and speed of the animal, fore and hind foot measurements, and the sex and age of the animal. What this shows is that there were no very small dogs and no large dogs in this group.

3.2. Domestic Cat

There are only six prints from domestic cats, which were found on three different tiles. The tiles are from the sites of Carvalheiras (CARV), Largo Carlos Amarante necropolis (Largo), and Cangosta Palha necropolis (CPA). On the tile from CPA, there is a series of four prints with a gap between the prints of about 12 cm. This is the stride length of this cat. The size of the prints varies, with two from CARV and Largo that are smaller than those from CPA. The smaller prints measure 2.5 cm in length and have a width of 2.4 and 2.8 cm. The prints from CPA have two that are complete and two incomplete. The two complete prints measure 3.2 cm in length and their widths are 2.7 and 2.8 cm.

3.3. Domestic Sheep and Goats

Domestic sheep and goats were the second most common prints found. Some prints could not be distinguished between sheep and goats. Many of the prints were overlapping, and not all of the pairs of hooves could be matched. Measurements were recorded for all prints, but for the summary of the size of the animals, only those where length or width was complete were utilized. Of the 74 goats, most were small and were likely from young animals. The average for the prints was 3.2 cm in length and 3.9 cm in width. The mode was 3.0 cm long and 2.8 cm wide with a range of 1.6 to 4.9 cm in length and 1.6 to 5.5 cm in width. The larger prints may be from adult animals or older subadults. Of the 75 sheep prints, the average was 3.1 cm for length and 3.1 cm for width. The mode for length was 3.0 cm and 2.7 cm for width. The range was 2.0–4.8 cm for length and 1.8–5.0 cm for width. As with the goats, most of these were young animals, but a few could have been older subadults or adults.

3.4. Birds

Only five prints from birds were found in this sample. The scarcity of bird prints may reflect the environment of the area and the characteristics of the clay for the CBM. Most of the prints were not complete and were not clear as to all the characteristics that aid in identification of the bird. There were prints for two types of birds. Some were similar to the pattern for anisodactyl bird tracks [5,6]. The anisodactyl footprint has three forward toes and one to the rear. Birds with this type of track include songbirds, herons, egrets, eagles, hawks, falcons, vultures, doves, and moorhens. There were also bird tracks that appear to be those of a ‘game bird’ [5,6]. In a game bird track, the first toe to the rear is greatly reduced or absent, there are three forward toes, and a metacarpal pad. Birds in this class include quail, pheasant, grouse, ptarmigan, partridge, turkey, coots, rails, cranes, plovers, and sandpipers. Of those, these prints are not turkey, coot, plover, or sandpiper tracks. One bird is in the medium-sized bird range and two are in the small-sized bird range [5,6]. The remaining prints were not complete enough to determine the size of the bird. The medium-sized bird measured 7.6 cm in length and 5.5 cm in width. This was the anisodactyl bird and may be a heron or egret. The small birds measured 5.2 cm in length and 5.2–5.4 cm in width. These two small birds are game birds and may be pheasants, grouse, ptarmigans, or partridges.

3.5. Human Prints

Human bare feet and shoe prints were found. In addition, there were some bricks and tiles with prints that may have been from hands or fingers. Many of the hand and finger marks were not clear. The shoe prints were identified by the presence of hob nail impressions. There is one shoe print that was not published in 2018 [9]. For the bare footprints, there are five that were not previously published [8]. The prints in this study are from seven different sites. Those sites are as follows:

- Granjinhos

- Carvalheiras

- Albergue

- Via XVII Av. Liberdade Necropolis

- Fujacal_J_Misericórdia

- Teatro

- Largo Carlos Amarante Necropolis

All bare foot and shoe prints were measured. The measurements shown in Table 3 are for the bare footprints and the numbers shown as 1–10 correspond to the measurement method used in the 2018 article [9]. Table 3 includes two measurements from the 2018 article and two from the current study. This table shows how similar all four prints are in size. All four of these prints were made by an adult female. Figure 7 shows the print from 1995.0171 and Figure 8 shows the print from 2024.0308, both from the current study.

Table 3.

Measurements of complete bare human footprints.

Figure 7.

Human footprint 1995.0171(©MADDS/n.ºinv.2024.0171/Felismina Vilas Boas).

Figure 8.

Human footprint 2024.0308 (©MADDS/n.ºinv.2024.0308/Felismina Vilas Boas).

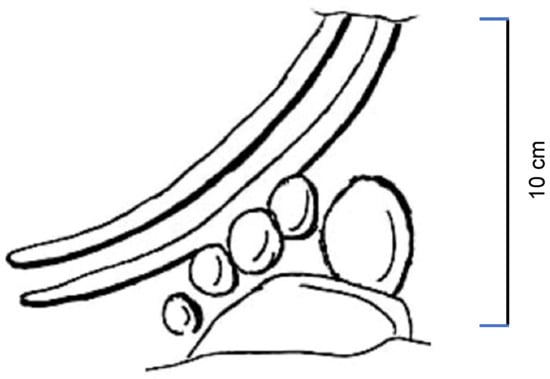

The current study includes three partial bare adult footprints. These prints include the front portion of one foot (Figure 9). This has all five toes and part of the ball of the foot and based on the overall size is likely an adult. Two other CBM fragments had what appeared to be the heels of a bare human foot. It is not clear why only the heel was present. Based on overall size, these were also likely made by an adult. Table 4 gives the measurements for the partial human bare footprints complete enough to measure. For 1996.0649, the metatarsophalangeal area is not complete, and the width of 59 mm is not comparable to the measurement of number 7 in Table 3. The maximum heel widths of 2024.0727 (1 and 2) are complete and comparable with the measurements of number 10 in Table 3. Based on these measurements, the size is lightly larger than the other measured prints but is within the size range of an adult female.

Figure 9.

Drawing of the partial human footprint 1996.0659 (©MADDS/n.ºinv.1996.0659/Amélia Marques).

Table 4.

Measurements for partial bare human footprints from the current study.

In the current study, there is one possible infant or young child print. However, the print is odd, in that it seems too wide for the length, and the arrangement of the toes is not as expected for a normal foot. Thus, this identification is not definitive, but human is the most likely animal to have created this print. A possible big toe (hallux) and two other toes are visible. The three toes shown appear too large for an infant or young child. The toes are also at odd angles relative to the heel and metatarsophalangeal area. Perhaps someone pressed the foot of this child into the wet clay and rolled it somewhat to obtain a good impression, resulting in the odd shape. The measurements are a maximum length of 87 mm; width at toes is 51 mm; and width at heel is 41 mm.

The current study has one complete right shoe print. This and the measurements from the shoe prints from the 2018 article [9] are recorded in Table 5. The shoe print from the current study is smaller than those reported in the 2018 article. The shoe print is very close to the size of a shoe print from the Roman site of Brigeto in Hungary [10]. The print in that study was estimated to be 210 mm in length and was estimated to be from a child 8–10 years of age. It is estimated that the shoe print from the current study is also from a child of that age range. Other children’s footprints were recorded in Bracara Augusta [9].

Table 5.

Measurements of complete shoe prints.

There is a proportional relationship between foot size and stature [11,12,13]. The same is true for shoe print length and stature because of the correlation between shoe print length and footprint length. Table 6 gives the stature for the bare footprints and the shoe prints from the current study and from the individuals reported in the 2018 article [9]. Stature was not calculated for the subadults from Bracara Augusta. The current study used regression formulas from two different research papers. One is based on a very large sample size (6682 men and 1330 women). This is a modern US Army sample consisting of a mix of ethnic groups [11]. The other paper is from Pakistan, with a sample of 291 individuals (145 men and 146 women) [12]. An inherent difficulty with all the studies and resulting regression formulas is that they are based on populations that are different from the Roman period peoples from Bracara Augusta. Data on stature based on foot or shoe sizes are not available for Roman period individuals. The advantage of these two studies, and particularly for the US Army sample, is the large sample sizes. This results in more robust regression formulas and is statistically advantageous for determining confidence limits. In Table 6 the ±4.9 cm is a 70 percent confidence level for the formula by Giles and Vallandigham [11].

Table 6.

Stature estimates of adult bare foot and shoe prints.

Calculating stature using shoe print length adds more uncertainty to the calculations of stature, because of various shoe styles and the fit of the shoe, which complicate equating shoe print length and footprint length. The overall use of shoe length still provides a reasonably good means of determining stature, even with the added complication of shoe types, because the basic premise of shoe length representing foot length and thus stature still holds true. Following the adjustment suggested in Giles and Vallandigham [11], shoe length less 2.62 cm gives an estimated foot length. This is assuming a flat shoe like a sandal or tennis shoe. This adjustment is within the adjustment noted by Dobosi [9] for the shoe print from the Roman site of Brigeto, Hungary. The foot length was then used with the same two regression formulas as the bare footprints to provide stature. The stature estimates between the two regression formulas are very similar, with an average difference of 1.2 cm. Stature based on the bare footprints and shoe prints in the Bracara Augusta sample varies from 147.9 to 154.1 cm with an average stature of 151.2 cm.

4. Discussion

Animal and human prints are well known on CBM but are not often published. Research has revealed published information for 10 sites that discusses animal and human prints. The published reports are from various Roman sites throughout Europe, the Middle East, and the British Islands and include Brigeto in Hungary [10], Cibalae in Croatia [14], Perge and Aizanoi in Turkey [15], Kefar ‘Othnay in Israel [16], Silchester in England [17], Vindolanda in England [18], Newstead in Scotland [19], Castro de Viladonga in Spain [20], and in the region of Lousada in Portugal [21]. In addition, one article was published on human prints from Braga (Bracara Augusta) [9]. These reports were used to compare with the findings of the current study. There is one human footprint on a tile that is mentioned in an online web page, but besides being identified as human, no further information was detailed. This find is from Folkstone Roman Villa in England [22].

4.1. Domestic Dog

Domestic dogs were the most common animal found in the current study and in most of the published materials from the other sites. Dogs were the most common pet in the Roman world [23] and were commonly found during the Roman period in Portugal [24]. One of the most notable aspects of the Roman period dogs, compared with the previous Iron Age animals, was their variability in size and morphology [18,25,26]. In addition to the small- and medium-sized dogs, the Roman period is known for the presence of a group of very small dogs and large dogs. The very small dogs could be described as lap dogs and were usually associated with the Roman elite. The large dogs were like the Laconian and Molossian and were used for shepherding and as guard animals [27].

The only report with no dog prints was from Lousada, Portugal. However, that sample was very small, with only five prints reported. For all the other sites, the most common prints were from dogs. The width of the paw prints was reported for some of these locations and ranged in size from 2.4 to 9.0 cm (Table 7). The 9.0 cm is larger than the current study, but otherwise the range of measurements compares favorably with the current study, with a range in width from 2.5 to 7.0 cm, including both fore and hind footprints. The Roman city of Cibalae, Croatia had 18 canids, which included four medium-sized dogs and six large dogs [14]. No measurements or information on the criteria for assigning medium and large sizes to the dogs were detailed. At Kefar ‘Othany, Israel there were two canids with one medium-sized animal that may have been a dog, jackal, or fox and one large canid that was a possible wolf [16]. Newstead had six dog prints, but no measurements were provided.

Table 7.

Sites with dog prints and range of widths recorded.

Bracara Augusta, Calleva, and Vindolanda all had large numbers of dog prints recorded and the range in width is very similar. In general, the sizes are of a normal symmetrical distribution. In the report for Calleva, Machin [17] graphed the measurements using a 2 mm and a 5 mm breakpoint. With the 2 mm graph there were five peaks and with the 5 mm graph there were three peaks. The majority of the prints from Calleva were in the 3.0–5.0 cm range, as in the current study. Though there is variation in the sizes, most of these dogs would be considered small or medium in size. There do not appear to be any very small dogs, which have a print of 3.0 cm or less [18]. Though some of the measurements are in that range, and could be from very small dogs, it is equally likely that these may represent young animals from the small-sized dogs. The only site that appears to have a large dog is at Aizanoi in Turkey. Large dogs do not seem to be common around the tilery at any of the sites.

The function and breed of the dogs are not apparent from the footprints. It can be speculated that the dogs from the current study may have been working dogs for livestock and also have functioned as guard animals. Different dog morphology and coat colors were likely present based on depictions of dogs on mosaics found in Portugal [24]. From a DNA study [24], the authors estimated that dogs have been bred in Portugal for 1600 years. To have a specific breed or physical characteristics of a dog, the female needs to be kept in a controlled environment. The smallest and largest dogs may have been considered rare and valuable. If these animals were kept by the tilery workers, they may not have been allowed the same freedom of movement as the other dogs. It is also possible that these breeds were not present. Those breeds may have been beyond the socio-economic status of the tilery workers, or simply not needed in that environment.

4.2. Domestic Cat

The finding of domestic cat prints helps to inform us of the history and spread of this animal. It is believed that Egypt was the location of the first domesticated cat around 4000 years ago. The wild ancestor of the domestic cat was in Central Europe perhaps as early as 12,000 years ago [28,29,30]. The island of Cyprus has cat remains, some buried with people, that date to 9500 BCE. There is a confirmed record of domesticated cats in Greece from around 480 BCE. The cat was probably in the Iberian Peninsula around 400 BCE. It is thought that the Phoenician, Etruscan, and Greek sailors brought the cat to various ports via their trading ships [28,29]. Cats were kept on board to control vermin. The Romans began to use cats to control vermin around the 4th century CE [29,30]. Romans introduced cats to northern Europe and outposts of their Empire via the Roman military. Domesticated cats were in Europe prior to the Roman period but were not common. With the spread of Roman influence and with the Roman army, cats were introduced in greater numbers. By the 10th century CE, cats were widespread [30]. Although cats may have come to Portugal on trading ships, it is most likely that it was the Roman military that brought them to Braga.

Footprints from domestic cats were found in small numbers at most of the sites, but no prints from cats were recorded at Aizanoi, Cibalae, or Newstead. Table 8 shows the five sites with the number of prints found and the range of widths for those prints. Two cat prints were recorded at Kefar ‘Othnay but no measurements were provided. Lousada had one cat print that was incomplete but measured 3.23 cm in width. Vindolanda had 16 prints, but no measurements were provided. Calleva had the greatest number of prints from cats, with 27. The remaining sites had one to six prints. The range of widths varies considerably. The author for the site at Vindolanda considered the cat prints found to be from a semi-feral cat that could have been Felis domesticus or Felis sylverstris. The size for F. sylverstris is typically 3.5 cm or larger and can be up to 7.5 cm in width [17,18]. The authors for Lousada considered that the cat print could have been from the wild cat found in Portugal, Felis sylverstris. However, they did not think it was, because the habitat of this wild cat species is in areas with little to no human contact. If the cat prints at Vindolanda are from the wild cat, then that would suggest that the environment around that tilery was in an area with little other human activity. Brigeto also had at least one print that was quite large, 6.1 cm, and would suggest that this too may have been a wild cat. The cat prints from Bracara Augusta are some of the smallest prints. The variety in the size of prints would suggest that the domestic cat varied greatly in size. It is also possible that some of the smaller prints may be from younger animals. Given the scarcity of cats until later in the Roman period, it is not unusual to have only a few cat prints found on the CBM. The few cat prints may have all been from tiles produced from later periods of construction at the site locations.

Table 8.

Sites with cat prints and range of widths recorded.

4.3. Human Prints

In the current study, human prints included hand and finger prints as well as bare foot and shoe prints. For the complete footprints, there were adult females and children. The children ranged from around 1 year of age to about 10 years of age. No human prints, hand or foot, were reported at Perge Aizanoi, Kefar ‘Othnay, Viladonga, or Lousada. Brigeto had one finger print and two shoe prints, with one being a near complete shoe print from a child 8–10 years of age. Calleva had bare foot and shoe prints. There were six bare footprints from three adults and three children. The shoe prints numbered 29, with 1 being a very young child, approximately 10 months old. No further information was provided on the human prints in that report.

Studies show that foot length is a good predictor of stature. The formulas developed vary and reflect the different ethnic groups studied. Each group has unique genetic and environmental factors that may be reflected in the parameters to estimate stature from foot length. Using a regression formula calculated from a specific population is the best method for establishing stature based on foot length. In the case of footprints from Bracara Augusta, that is not available. This was discussed by Marado and Ribeiro [9] and is why they applied three different formulas on the bare footprint measurements. The ethnic groups from those studies were from Egypt, UK, and Slovak sources, with the consideration that geographic proximity is a proxy for biological proximity [9]. However, those formulas were generated from generally small sample sizes. The current study used formulas generated from larger sample sizes to provide more robust regression formulas. This is especially true for the US sample of mixed ethnic groups.

Looking at the range of stature for all prints, see Table 6 above, gives a range of 148 to 154 cm. Data from skeletal material from Conimbriga (Coimbra), Portugal shows that average female stature during the Iron Age was 150.5 cm (sample size of 20) and during the Roman period it increased to 151.5 cm with a sample size of four [31] (appendix). Data on stature from Cardoso and Gomes [32] also have a Roman period female stature of 151.5 cm, based on four femur calculations, and 153.8 cm based on five humerus calculations. These measurements compare favorably with the statures calculated in the current study.

4.4. Seasonality of Production

It is assumed that the rainy season would not be a reasonable time to try to form and dry tiles. It is unlikely that there was any roof over the tile drying area. Braga generally has a Mediterranean climate, with dry summers and mild, wet winters. From June to mid-September the weather is generally warm and dry. The rainy season begins in October and goes through February, with some rain continuing through May [33]. During the Roman period there was a climatic event referred to as the Roman Warm Period or Roman Climatic Optimum, where weather was warm and humid. Temperatures were on average up to 2 °C warmer than today. This was followed by a drying event, which may have influenced the collapse of the Roman Empire [34] (p. 7).

The rain cycles and the presence of prints from young sheep and goats suggests that the production relating to forming and drying tiles started in the spring. Goats typically have their kidding season in the spring. However, sheep can have their lambing season in the spring or autumn (off-season lambing) [35]. If in the autumn, lambing is around the time of the start of the rainy season. The rains regenerate vegetation, which is necessary fodder for the ewes [34]. All together, considering the rainy season and the lambing–kidding season, tiles could have been produced and left to dry starting in the spring, continuing through the summer, and ending in the early autumn.

4.5. Environment

Clays from the Prado/Ucha regions were used for ceramics in Bracara Augusta, and this area may have also been a center for tile production [2]. There are five kilns known in the Braga area, but none of these kilns were known to be used in the production of CBM [3]. Although the Prado/Ucha region is a clay source, at the present time, there is no archeological indication of a tilery [3]. This area would be a good location for a tilery. In addition to the clay source, it is near the Rio Cavado, which would provide water to mix the clay for the tiles. A tilery would presumably encompass a fairly large area to have space for drying tiles. It is also likely that the tilery included small-scale settlements and farms in the immediate area. The small-scale animal husbandry associated with the farms would be a manageable practice along with tile production. Sheep and goats could provide for the farms’ subsistence needs as well as wool for spinning and garments.

It is of interest to consider what prints were not found. There were no domestic chicken, pig, cattle, horse, or donkey prints. The larger animals were likely kept well away from the drying areas, because if they stepped on the tiles, it would likely render them unusable. There were no prints seen from rodents (mice and rats) or from rabbits (wild or domestic).

In the current study, the only prints from wild animals were from birds. These may have included a heron or egret, and possibly a pheasant, grouse, ptarmigan, or partridge. If the tilery was near the Rio Cavado that may explain the presence of the heron or egret. There were no prints from other wild animals, which would suggest that wild spaces/environments were not located nearby or that there was too much human activity in the area discouraging the wild animals from entering the area. Another hypothesis to consider with the lack of wild animals is that perhaps some fencing was present. However, if there was fencing, it did not keep out the sheep, goats, or dogs. Wild animal prints were recorded at the other sites, including Cibalae in Croatia, Perge and Aizanoi in Turkey, Kefar ‘Othnay in Israel, and Silchester in England. No wild animals were found at Viladonga in Spain, Lousada in Portugal, or Brigeto in Hungary.

5. Conclusions

The CBM from Bracara Augusta provide one of the largest samples of tiles with animal prints for which analysis has been completed. There were 420 animal prints on 152 tiles. The prints were primarily domesticated animals and included dogs, cats, sheep, and goats. The footprints reflect the animals living at the time that the tilery was in operation, as opposed to skeletal evidence, which generally reflects consumption of the animals. Organic materials are rarely found near Braga because of the acidic soils. Thus, the study of these footprints offers us a rare view of the life and animals living at the tilery.

Dogs produced the most numerous animal prints, and the biological data from the impressed prints indicates that these were small to medium in size. This compares favorably with the data from 10 other sites with animal prints. The presence of cat prints helps to provide information on the history and spread of this domestic animal. Cats were probably brought to Braga via the Roman military.

Human prints included bare footprints and shoe prints. Age, sex, and stature were estimated from these prints. The current study and the study by Marado and Ribeiro [9] indicate that women and children were present in the drying area. They may have been working in the drying area or around the area helping tend animals associated with the nearby farmsteads. Stature calculated from the prints of the adult females was an average of 151.2, which compares favorably with data from other areas of Portugal with stature estimated from femur and humeral lengths.

Though there is no archeological indication of where the tilery was located, or if there was in fact more than one location, the impressed prints of the animals and humans provide some indication of what animals were common in the area. The data suggest that pasture for sheep and goats was likely near the drying areas. It is possible that wild spaces were not close, or that there was enough human activity in close proximity to prevent wild animals from entering the area. These impressed prints offer alternative evidence for the environment, animals, and humans that occupied the tilery area.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the author on request at walth.c@yahoo.com.

Acknowledgments

This study was completed as part of the ‘Cultural Volunteering’ project of Museus e Monumentos de Portugal, EPE, at the D. Diogo de Sousa Archaeology Museum, Rua dos Bombeiros Voluntários, 4700-025 Braga, Portugal. I would like to thank the staff of the Museum (D. Diogo de Sousa) and specifically staff members Rosa Jardim, Cristina Vilas Boas Braga, Óscar Santos, Felismina Vilas Boas, and Clara Lobo. Images used were part of the photo archives of the museum and copyright information is in each photo caption.

Conflicts of Interest

This author declares no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| MADDS | Museu de Arqueologia D. Diogo de Sousa |

| BCE | Before common era |

| CE | Common era |

| CBM | Ceramic building materials |

| CARV | Carvalheiras |

| Largo | Largo Carlos Amarante necropolis |

| CPA | Cangosta Palha necropolis |

| FL | Foot length |

| cm | Centimeters |

| mm | Millimeters |

| L | Left |

| R | Right |

References

- Martins, M.M. Bracara Augusta: Integration of the North-West into the Roman World. In Museu D. Diogo de Sousa Guide, 1st ed.; Silva, I., Ed.; Institute Português de Museus: Lisbon, Portugal, 2005; pp. 56–65. [Google Scholar]

- Martins, M.R.; Abreu de Carvalho, H.P. Bracara Augusta and the Changing Rural Landscape. In Changing Landscapes: The Impact of Roman Towns in the Western Mediterranean, Proceedings of the International Colloquium, Castelo de Vide/Marvão, Portugal, 15–17 May 2008; Corsi, C., Vermeulen, F., Eds.; Ante Quem: Bologna, Italy, 2010; pp. 281–298. [Google Scholar]

- Braga, C.M. (D. Diogo D. Sousa Museu de Arqueologia, Braga, Portugal). Personal communication, 2025.

- Marado, L.M.; Braga, C.; Fontes, L. Bone diagenesis in Via XVII inhumations (Bracara Augusta): Identification of taphonomic and environmental factors in differential skeletal preservation. Estud. Quat. 2018, 18, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bang, P.; Dahlstrom, P. The Tracks Signs of British and European Mammals and Birds; Collins Guide: London, UK, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, R.; Ferguson, J.; Lawrence, M.; Lees, D. Tracks and Signs of the Birds of Britain and Europe: An Identification Guide; Christopher Helm: London, UK, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Yadav, N.; Kesharwani, L. Comparison of Fore and Hind Foot of Artiodactlya Species of Animals for Forensic Importance. J. Forensic Res. 2020, 11, 465. [Google Scholar]

- Yadav, N.; Mishra, M.K.; Saran, V. Characterization of Pugmarks for Animal Species Identification for Forensic Importance. J. Forensic. Sci. Criminol. 2020, 8, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Marado, L.M.; Ribeiro, J. Biological Profile Estimation Based on Footprints and Shoeprints from Bracara Augusta Figlinae (Brick Workshops). Heritage 2018, 1, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobosi, L. Animal Footprints on Roman Tiles from Brigeto. In Dissertationes Archaeologicas ex Instituto Archaeologico, Universitatis de Rolando Eötovös Nominate, Ser. 3, No. 4; Eötvös Loránd University, Institute of Archaeological Sciences: Budapest, Hungary, 2016; pp. 117–134. Available online: http://dissarch.elte.hu (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Giles, E.; Vallandigham, P.H. Height Estimation from Foot and Shoeprint Length. J. Forensic Sci. 1991, 36, 1134–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malik, A.R.; Akhter, N.; Ali, R.; Farrukh, R.; Aziz, K. A study on Estimation of Stature from Foot Length. Prof. Med. J. 2015, 22, 631–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiseman, A.L.A.; De Groote, I. One size fits all? Stature estimation from footprints and the effect of substrate and speed on footprint creation. Anat. Rec. 2022, 305, 1692–1700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hrvoje, L.; Vulie, H.; Jurak, M.; Grgoic, A.; Spirant, K.; Mihelić, D.; Vuković, S. Animal Footprints on Bricks from the Roman Site of Cibalae, Croatia. In Proceedings of the 5th International Scientific Meeting, Days of Veterinary Medicine, Ohrid, Macedonia, 5–7 September 2014. Volume 37, Supplement S1, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Oğus, B. Animal Footprints on Roman Tiles from Perge and Aizanoi. Adalya 2021, 24, 229–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bar-Oz, G.; Tepper, Y. Out on the Tiles. Animal Footprints from the Roman Site of Kefar ‘Othnay (Legio) Israel. Near East. Archaeol. 2010, 73, 244–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machin, S.L. Constructing Calleva: A Multidisciplinary Study of the Production, Distribution and Consumption of Ceramic Building Materials at the Roman Town of Silchester, Hampshire. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Reading, Reading, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett, D. Life history information from tracks of domestic dogs (Canis familiaris) in ceramic building materials from a Roman bath house at Vindolanda, Northumberland, England. Archaeofauna 2012, 21, 7–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliot, N. Animal footprints on Roman bricks from Newstead. Proc. Soc. Antiq. Scot. 1991, 121, 223–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez, O.C.; García-Lomas, R.G. Tégulas com Huellas de Animales em el Castro de Vilodonga. CROA Boletín Mus. Castro Vilandonga 1996, 6, 9–11. [Google Scholar]

- Sousa, L.; Nunes, M.; Gonçalves, C. Tegulae com marcas de oleiro e pegadas de animais no concelho de Lousada. Oppidum 2007, 2, 57–74. [Google Scholar]

- Canterbury Archaeological Trust. Folkstone Roman Villa. Available online: https://unlockingourpast.co.uk/finds/roof-tile/ (accessed on 21 May 2025).

- MacKinnon, M. “Tails” of Romanization, animals and Inequality in the Roman Mediterranean Context. In The Ancient World; Arbuckle, B., McCarty, S., Eds.; University Press of Colorado: Denver, CO, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pires, A.E.; Detry, C.; Fernandez-Rodriguez, C.; Valenzuela-Lamas, S.; Arruda, A.M.; Mazzorin, J.; Ollivier, M.; Hänni, C.; Simões, F.; Ginja, C. Roman dogs from the Iberian Peninsula and the Maghreb—A glimpse into their morphology and genetics. Quat. Int. 2018, 471, 132–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colominas, L. Morphometric Variability of Roman Dogs in Hispania Tarraconensis: The Case Study of the Vila de Madrid Necropolis. Int. J. Osteoarchaeol. 2016, 26, 897–905. Available online: https://www.wileyonlinelibrary.com/doi.10.1002/oa.2507 (accessed on 2 April 2025). [CrossRef]

- Cram, L. Varieties of Dog in Roman Britain. In Dogs Through Time: An Archaeological Perspective, Proceedings of the 1st ICAZ Symposium on the History of the Domestic Dog, Eighth Congress of the International Council for Archaeozoology (ICAZ98), Victoria, BC, Canada, 23–29 August 1998; Crockford, S.J., Ed.; BAR International Series 889; BAR Publishing: Oxford, UK, 2000; pp. 171–180. [Google Scholar]

- Balic, M. What Pets Did the Ancient Romans Have? Available online: https://www.thecollector.com/what-pets-ancient-romans-have/ (accessed on 9 January 2025).

- Falde, N. Wild Twist in the Story of Cat Domestication. 2022. Available online: https://www.ancient-origins.net/news-general/cat-domestication-europe-0017501 (accessed on 9 January 2025).

- Mark, J.J. Cats in the Ancient World. In World History Encyclopedia; World History Publishing Ltd.: Godalming, UK, 2012; Available online: https://www.worldhistory.org/article/466/cats-in-the-ancient-world/ (accessed on 14 January 2025).

- Serpell, J.A. Domestication and history of the cat. In The Domestic Cat: The Biology of Its Behavior, 3rd ed.; Turner, D.C., Bateson, P., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2014; pp. 83–100. [Google Scholar]

- Danubio, M.E.; Martella, P.; Sanna, E. Changes in stature from the Upper Paleolithic to the Medieval period in Western Europe. J. Anthropol. Sci. 2017, 95, 269–280. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cardoso, H.F.V.; Gomes, J.E.A. Trends in Adult Stature of Peoples who Inhabited the Modern Portuguese Territory from the Mesolithic to the Late 20th Century. Int. J. Osteoarchaeol. 2008, 19, 711–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Climate Data. Climate Portugal. Available online: https://en.climate-data.org/europe/portugla-250/ (accessed on 21 July 2025).

- Hu, H.M.; Michel, V.; Valensi, P.; Mii, H.S.; Starnini, E.; Zunino, M.; Shen, C. Stalagmite Inferred Climate in the Western Mediterranean during the Roman Warm Period. Climate 2022, 10, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tornero, C.; Balasse, M.; Bréhard, S.; Carrère, D.; Fiorillo, J.; Guilaine, J.; Vigne, J.; Manen, C. Early evidence of sheep lambing de-seasoning in the Western Mediterranean in the sixth millennium BCE. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 12798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).